Infection Prevention and Control in Public Hospitals

Overview

Community-acquired infections and hospital-associated infections are the most common complication affecting hospital patients. Infections prolong hospital stays, increase costs and can cause significant harm to patients, some of whom die as a result.

Overall the audit found that, based on the most reliable indicators, some patient outcomes have been improving while others have remained static over the past 10 years. This indicates that the Victorian health system has been generally effective at managing and reducing infection rates. However, the audit identified areas for improvement.

The Department of Health should make better use of infection surveillance data to identify potentially missed opportunities to further reduce infections. It also lacks a clearly articulated and communicated set of strategic priorities to support health services into the future.

Each of the four audited health services do not consistently maintain infection control on organisational risk registers and there is a lack of formal consideration of infection control risks in maintenance and asset replacement decision-making. Health services also need to continue to address known infection control issues by effectively managing all healthcare workers who underperform in hand hygiene compliance, based on monitoring undertaken three times per year as part of the national hand hygiene program.

Infection Prevention and Control in Public Hospitals: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER June 2013

PP No 232, Session 2010–13

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Infection Prevention and Control in Public Hospitals.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

12 June 2013

Audit summary

Infections are the most common complication affecting hospital patients. People can bring infections acquired in the community with them into hospital, or they can acquire an infection during their hospital stay—known as healthcare-associated infections (HAI). Infections prolong hospital stays, increase costs and can cause significant harm to patients, some of whom die as a result.

In 2009, an Australian and New Zealand study published in the Medical Journal of Australia estimated a 20 per cent mortality rate after 30 days among patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia (SAB) infections, a serious type of bloodstream infection. Findings from a 2006 investigation published by the Department of Health (the department) indicated that surgical site infections (SSI) associated with hip and knee replacements alone resulted in $19.5 million additional treatment costs to the Victorian community that year.

Any person working in or entering a healthcare facility is at risk of infection, although the sicker the patient the higher the risk. However, HAIs are often preventable. Health services have an important role in preventing and controlling infections in public hospitals. The department has a role in providing policy and good practice guidance to health services and maintaining a statewide perspective to make sure there is an equitable distribution of resources across the state.

The department also has a role in monitoring health service performance, based on infection rate indicators, against state hospital cleaning standards and healthcare worker hand hygiene compliance rates.

The audit examined the role of the department and health services in effectively preventing, monitoring and controlling infections in public hospitals.

Conclusions

The Victorian health system is generally effective at managing and reducing infection rates, and has well developed systems and processes to monitor and report infections in public hospitals. However, there is variation in hand hygiene compliance rates among healthcare worker groups, and heart bypass surgery infection rates have seen no improvement over 10 years.

The department does not review infection data to identify systemic trends, or health services that are persistent outliers over time. The department and health services are therefore not able to take targeted action to address such matters and may miss opportunities to improve patient outcomes by reducing infections.

The department has established effective supports for health services, including guidelines and standards, monitoring, reporting and advice. However, it has not finalised its strategy, nor communicated its current strategic priorities to health services, and lacks comprehensive state-level expert advice on infection control. It does not have a statewide perspective of infection control capacity, which limits its ability to plan for broader systemic need. Consequently, it is not able to support health services to make further gains and meet future challenges.

Each of the audited hospitals has effective systems to support infection prevention and control—such as comprehensive policies and procedures, training, and contract management arrangements for facilities' services. However, infection control infrastructure is in high demand. For example, isolation rooms require daily prioritisation by infection control staff. This may increase the risk of infection to patients and staff.

The audited hospitals are not consistently addressing known infection control issues by effectively managing clinical staff who underperform in hand hygiene compliance.

Audited hospitals do not consistently maintain infection control on organisational risk registers, and there is a lack of formal consideration of infection control risks in maintenance and asset replacement decision-making. There is also an over-reliance of audited hospitals on external accreditation regimes to guide their activity. This means, for example, that due to new national accreditation requirements, health services are only now implementing compliance regimes for aseptic technique, despite this being well-known better practice.

Findings

Patient outcomes and performance management

Infection control outcome data over the past decade show improvements against some, but not all, indicators. However, the department may not be aware of all areas in need of improvement because it does not analyse the infection data it collects adequately.

Each of the audited hospitals has set clear infection control expectations for all staff and contractors and undertakes compliance and performance monitoring activities. Statewide data shows that health services have achieved some improvement in medical staff performance in relation to hand hygiene compliance, but more needs to be done to drive improvement in hand hygiene culture across the health sector.

Patient outcomes

The department has not reviewed trends in infection data to identify common areas for improvement, or the presence of health services that are persistent outliers. As a consequence, it has not used this data to inform targeted performance management.

In 2010–11, Victorian rates of healthcare-associated SAB infections compared well with other Australian jurisdictions and were below the national average.

Statewide infection control outcome data over the past decade shows that infection rates have improved against some indicators but remained static on others. For example:

- Surveillance results of healthcare-associated clostridium difficile infections—an organism causing diarrhoea—show that infection rates have increased since this data collection began in early 2010–11.

- Rates of SAB infections appear to be decreasing since surveillance began in early 2010–11. More data for these indicators needs to be collected before a clear trend can be identified.

- Victorian Healthcare Associated Infection Surveillance System (VICNISS) data reveals that SSI rates among patients following hip and knee replacements have significantly declined since late 2002. However, SSI rates among heart bypass patients have remained static over the same period. The department is currently reviewing various data sources in relation to these results and plans to consult with clinical experts to inform an improvement strategy for heart bypass SSIs.

Performance monitoring and management

The department effectively monitors health service performance against infection control indicators on a quarterly basis. However, there are opportunities to improve the use of infection data to identify systemic trends or health services that are persistent outliers.

Governance and scope issues, and a lack of timely reporting of infection control data, indicate that the department has not effectively managed its service agreement with the metropolitan health service that auspices the VICNISS Coordinating Centre. This means that the department has not been measuring the benefit of its $1.5 million annual investment. The department is now working to address these issues.

Each of the audited hospitals undertakes formal and informal infection control-related compliance monitoring activities, although there are common gaps. Efforts to address medical staff performance in hand hygiene compliance have resulted in some improvement. Performance results indicate a need for greater consistency of compliance among healthcare workers, particularly given its relevance to patient safety.

Supporting systems

Victoria has established a mature infection control support system for health services based on guidance, monitoring and reporting. However, the department has not finalised its strategy, nor communicated a clear strategic vision of infection control priorities, to guide health services and to drive overall improvements in infection control performance.

Each of the audited hospitals has comprehensive, current and accessible infection control policies and procedures, and clearly defined expectations set out in staff position descriptions. While training and planned maintenance processes are adequate, these could be improved through a more systematic approach to training, and transparent prioritisation of maintenance tasks.

The Department of Health

The department has provided health services with a good foundation for embedding infection prevention and control into their daily activities by developing standards, guidelines, programs and an infection surveillance and reporting system. However, it does not have a current strategy to guide future improvements in health services.

In March 2013, the department established the Ministerial Expert Panel on Hand Hygiene. While this is a positive initiative, the department has been without a comprehensive source of state-level advice to inform the development of strategic priorities and its participation in national committees since disbanding the Victorian Advisory Committee on Infection Control in 2010.

The department does not routinely collect data on the isolation capacity at each hospital. This means it does not have a current statewide view of infection control capacity to inform capital planning.

Health services

Each of the audited hospitals has clearly defined infection control governance and accountability structures. They also provide staff with infection control training through mandatory corporate inductions and targeted refresher and general training opportunities. However, there are gaps in the systems for assessing and registering infection control risks. For example, the audited hospitals do not consistently include infection control on organisational risk registers, and three of the four audited hospitals do not formally consider infection control risks in maintenance and asset replacement prioritisation.

There is an over-reliance of audited hospitals on external accreditation regimes to guide their activity, rather than comprehensive good governance principles. Three of the four audited hospitals provide infection control refresher training on an ad hoc basis, raising the risk that they might miss groups of staff or particular topic areas. Three of the four audited hospitals use a formal risk assessment to inform prioritisation of access to isolation rooms. Consistent, risk-based decision-making is particularly important in hospitals where isolation capacity is low to help them to maximise the equity of access to scarce resources.

Infection control in rural hospitals

Since 2001, the department has supported regional health services and small rural hospitals by providing additional funding for infection control staff. However, there is a lack of transparency and consistency in the provision of this additional support due to differences in service delivery models and changes to the funding model. The lack of a comprehensive statewide review of this program has meant that practitioners, health services and departmental staff have not had the opportunity to consider the continuing effectiveness of these regional models.

Recommendations

That the Department of Health:

- uses the infection control data it collects to inform future strategy on infection control

- identifies and appropriately manages health services with persistent or recurring poor infection control performance.

That health services:

- develop and implement targeted strategies to address persistent underperformance in hand hygiene compliance among relevant healthcare worker groups.

That the Department of Health:

- accesses required expert advice and uses it to inform future strategy on infection control

- includes targeted initiatives to all known areas of underperformance in infection control in its future infection control strategy

- evaluates the effectiveness of the rural infection control consultant models.

That health services:

- factor in infection control risks when prioritising maintenance and asset replacement.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report, or relevant extracts from the report, was provided to the Department of Health and the audited hospitals with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Community-acquired infections and healthcare-associated infections (HAI) are the most common complication affecting hospital patients. Community-acquired infections are those that people bring with them into hospital. HAIs are acquired or identified during hospital care. Infections can also appear after patient discharge and depending on the severity can require re-admission for further treatment.

Infections prolong hospital stays, increase costs and can cause significant harm to patients, some of whom die as a result. In 2009, an Australian and New Zealand study, published in the Medical Journal of Australia, estimated a 20 per cent mortality rate after 30 days among patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia (SAB) infections. This is a serious type of bloodstream infection, although the infection was not the sole predictor of death.

In 2009, the Productivity Commission reported that Australia had an estimated 180 000 HAIs annually. In 2006, the Department of Health (the department) published an investigation of surgical site infections (SSI). It found the average cost for treating SSIs was $41 000 for knee replacement patients and $34 000 for hip replacement patients. Given there were 523 SSIs associated with hip and knee replacements in 2006, this resulted in around $19.5 million additional treatment costs to the Victorian community.

Any person working in or entering a healthcare facility is at risk of infection, although the sicker the patient the higher the risk. However, HAIs are often preventable, and while everyone—including patients, visitors and the wider community—has a role in preventing and controlling them, this report focuses on the role of the department and health services in infection prevention and control.

The Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infection in Healthcare indicate that successful infection prevention and control includes:

- regularly applying basic strategies, also known as standard precautions, such as hand hygiene and the use of personal protective equipment—for example, gloves and gowns—and routine cleaning

- routine monitoring of patients, and screening for infections to assist with early identification of an outbreak

- effectively managing infections where standard precautions may be insufficient

- responsible use of antibiotics, also known as antimicrobial stewardship, which involves prescribing the appropriate antibiotic at the appropriate time and dosage—inappropriate antibiotic use increases the emergence of antibiotic‑resistant infections

- making patients and visitors aware of their role in preventing infections.

Health services need to maintain systems—such as policies and procedures, training, monitoring and performance management programs—to support successful infection prevention and control throughout the organisation. Effective governance and implementation of these supporting systems can result in better outcomes for patients and reduced costs to the health system.

1.2 Legislation

Health Services Act 1988

One of the objectives of the Health Services Act 1988 (the Act) is to make sure that 'health services provided by health care agencies are of a high quality'. To realise this, the secretary of the department may, under section 11A(d) of the Act, 'encourage safety and improvement in the quality of health services provided by health care agencies and health service establishments'.

Under section 18(e) of the Act, health service funding is conditional on meeting the objectives, priorities and key performance outcomes specified in the Statement of Priorities (SoP). SoPs are the key accountability agreements between health services and the Minister for Health. They include infection control related indicators, including rates of patient infections and staff hand hygiene compliance. The department uses SoPs to monitor health service performance against key financial, access, and service performance priorities and agreed targets.

1.3 Infection prevention and control activities

1.3.1 Roles and responsibilities

Department of Health

The department is responsible for providing policy and good practice guidance to health services and monitoring their performance against SoP indicators.

The department's Quality, Safety and Patient Experience Branch is responsible for managing the public hospital infection control program, which includes monitoring hospital cleaning and infection rate data.

Health services

Victorian health services have a range of infection prevention and control responsibilities set out in legislation and SoPs. In relation to infection control, health services must set organisation-level expectations, provide guidance and relevant training to staff, make sure facilities and equipment are clean, and monitor staff compliance and the effectiveness of infection prevention and control strategies.

1.3.2 Policies and standards

Start Clean: Victorian Infection Control Strategy 2007–11

In 2007, the department produced a $10 million four-year strategy aimed at improving infection control in the following areas:

- prevention:

- hand hygiene compliance

- education on cleaning standards for health care workers

- promotion of the judicious use of antibiotics to prevent the development of infections resistant to antibiotics

- consumer information and participation:

- public reporting of HAIs from 2008–09

- consumer-targeted clean hands campaign to engage consumers in their own care

- detection and management:

- purchasing equipment and testing kits to increase the capacity of hospitals to rapidly diagnose significant infection-causing organisms

- mandatory data submission on all bloodstream infections

- guidelines on the management of patients with multi-resistant organisms, including surveillance activities and screening of patients.

Cleaning standards for Victorian health facilities 2011

In 2000, the department first published the Cleaning standards for Victorian health facilities (the cleaning standards). The latest edition was published in 2011. The standards describe the expected level of cleanliness based on four risk categories, as summarised in Figure 1A.

Figure 1A

Cleaning standards risk categories

Risk category |

Risk description |

Example locations |

|---|---|---|

Very high risk category A |

A very high risk of infection transmission as patients are very susceptible and/or undergo highly invasive procedures. |

Operating theatres, intensive care unit and central sterilising department |

High risk category B |

A high risk of transmission as patients are very susceptible and/or undergo highly invasive procedures, or because surgical equipment and other supplies must be processed and/or stored to the highest standards. |

Sterile stock storage, emergency department and general wards |

Risk category |

Risk description |

Example locations |

Moderate risk category C |

Areas where the risk of infection transmission must be minimised. |

Outpatient clinic, public areas and pathology |

Low risk category D |

Areas where it is important to maintain good hygiene. |

Administrative areas and external surrounds |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from Cleaning standards for Victorian health facilities 2011, Department of Health, March 2011.

Each year, health services are subject to one external audit, undertaken by accredited cleaning standards auditors, and two internal audits against the cleaning standards. Cleaning auditors score areas in each risk category against an acceptable quality level (AQL). Achievement of AQLs is required under health service SoPs. Health services report the results of external cleaning audits to the department each year.

Maintenance standards for critical areas in Victorian health facilities

The 2010 Maintenance standards for critical areas in Victorian health facilities (the maintenance standards) provide minimum standards and requirements for maintaining buildings in health services. The condition of buildings, such as the state of ventilation systems, can have a significant impact on infection transmission. The maintenance standards adopt the same risk categories as the cleaning standards.

1.3.3 Surveillance and performance monitoring

Victorian Healthcare Associated Infection Surveillance System

In 2002, the department established the Victorian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance System (VICNISS)—also known as the Victorian Healthcare Associated Infection Surveillance System—to coordinate infection surveillance activities in Victorian public hospitals. This involves collecting and analysing data from individual hospitals and reporting results quarterly to participating services and the department. All Victorian public hospitals are required to participate in VICNISS.

VICNISS operates two levels of surveillance determined by the size of the hospital—Type 1 hospitals have more than 100 beds and Type 2 hospitals have less than 100 beds.

VICNISS collects data on 38 indicators for infections relating to surgery, intensive care, dialysis units, organism-specific infections, health care worker vaccinations, occupational exposures where staff come into contact with a patient's bodily fluids, and hand hygiene compliance rates. Figure 1B details the indicators for Type 1 and Type 2 hospitals. The department requires compulsory reporting to VICNISS against six indicators: two organism-based indicators, hand hygiene compliance, healthcare worker influenza immunisation, intensive care unit blood stream infections, and surgical site infection rates for three procedures—heart bypass surgery and hip and knee replacements. Submission of all other VICNISS data is voluntary.

Figure 1B

VICNISS infection surveillance indicators

Location |

Indicator |

Type 1 |

Type 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

Surgical Site Infections |

Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair |

Yes |

|

Appendicectomy |

Yes |

||

Breast surgery |

Yes |

||

Cardiac surgery(a) |

Yes |

||

Carotid endarterectomy |

Yes |

||

Gallbladder surgery |

Yes |

||

Craniotomy |

Yes |

||

Caesarean section |

Yes |

||

Peripheral leg artery bypass grafts |

Yes |

||

Gastric surgery |

Yes |

||

Herniorrhaphy |

Yes |

||

Hip prosthesis(a) |

Yes |

||

Hysterectomy |

Yes |

||

Knee prosthesis(a) |

Yes |

||

Bowel surgery |

Yes |

||

Rectal surgery |

Yes |

||

Thoracic surgery |

Yes |

||

Ventricular shunt |

Yes |

||

Other infections related to surgery |

Yes |

||

Surgical Antibiotic Prophylaxis |

Choice and timing of antibiotic for surgical procedures against Therapeutic Guidelines |

Yes |

Yes |

Intensive care |

Central Line Associated Blood Stream Infections(a) |

Yes |

|

Ventilator Associated Pneumonia |

Yes |

||

Neonatal intensive care |

Central Line Associated Blood Stream Infections |

||

Peripheral Line Associated Blood Stream Infections |

|||

Haemodialysis unit |

Infection related to vascular access site |

||

Outpatient haemodialysis centre |

Yes |

||

Other invasive procedure |

Peripheral Venous Catheter use |

Yes |

|

Organism specific infections |

Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia(a) |

Yes |

Yes |

Clostridium difficile infection(a) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Multi-resistant organism prevalence |

Yes |

||

Primary laboratory confirmed bloodstream infection |

Yes |

||

Health care workers |

Staff exposures to blood and bodily fluids |

Yes |

|

Measles, mumps, rubella vaccination rates |

Yes |

||

Hepatitis B vaccination rates |

Yes |

||

Annual influenza vaccination rate(a) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Hand hygiene compliance rates(a) |

Yes |

Yes |

(a) These indicators are compulsory.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In the smaller Type 2 hospitals, the number of infections and patients at risk of infection are too small to calculate valid and reliable infection rates. Alternative surveillance methods are undertaken such as 'process' surveillance and reporting of selected infections.

Process surveillance monitors processes shown to affect outcomes, rather than the outcomes themselves. Processes that closely relate to improved infection outcomes include hand washing, correct administration of antibiotics to surgical patients, and staff vaccination programs for influenza and measles.

Other surveillance approaches for Type 2 hospitals include reporting of selected infections and related events, such as multi-resistant organisms (MROs) and serious wound infections.

Victorian health service performance monitoring framework

The Victorian health service performance monitoring framework outlines the approaches and measures the department uses to monitor and evaluate health services. This forms part of an accountability framework that also includes:

- the annual SoPs that sets out government policy priorities, health service specific priorities and expected performance in key areas for the financial year

- a performance assessment score (PAS), calculated quarterly, that reflects service levels, access, quality and financial aspects of performance.

The framework comprises 34 key performance indicators (KPI), of which six relate to infection control. Figure 1C outlines the six infection control related KPIs included in the SoPs.

Figure 1C

SoPs infection control related KPIs

KPI |

KPI description |

Target |

|---|---|---|

Accreditation |

Health service accreditation |

Full accreditation |

Cleaning |

Compliance with external cleaning audit |

Full compliance |

VICNISS data |

Submission of infection surveillance data to VICNISS |

Full compliance |

VICNISS performance |

Hospital acquired infection surveillance sites |

No outliers |

Hand hygiene |

Hand hygiene compliance |

70 per cent |

SAB |

SAB rate per occupied bed day |

< 2 / 10 000 bed days |

Note: The Quality, Safety and Patient Experience branch of the department monitors these KPIs.

Source: Department of Health, Victorian health service performance monitoring framework 2012–13 business rules.

Of these, only the SAB KPI contributes to a health service's PAS. The department uses the PAS for determining the level of performance monitoring it applies to health services. The SAB KPI contributes to 5 per cent of the overall PAS.

Health service accreditation is an external assessment measuring the performance of health service governance and quality assurance systems against a set of agreed standards. In 2011, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (the Commission) released a new set of National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards (the national standards).

Of the 10 national standards, standard three focuses on 'preventing and controlling healthcare associated infections'. Implementation of the national standards commenced in January 2013. In this introductory year, health services undergoing full accreditation are assessed against all 10 standards, and health services undergoing mid-cycle accreditation review are assessed against three of the 10 standards. Standard three is included within the set of three standards reviewed at the mid-cycle point. Within the standards, the Commission has identified a number of 'core' and 'developmental' actions. Health services must comply with 'core' actions and demonstrate work being done to achieve 'developmental' actions.

1.4 Audit objective and scope

The audit objective was to examine the effectiveness of prevention, monitoring and control of infections in public hospitals.

The audit focused on infection prevention and control activities of the department and a sample of health services that represent the range of health service types in Victoria. The sample comprised:

- two large hospitals in outer metropolitan Melbourne (Type 1)

- a large hospital in regional Victoria (Type 1)

- a small hospital in regional Victoria (Type 2).

1.5 Audit method and cost

Audit methods included a health service self-assessment, interviews with departmental and health service staff and statistical analysis of health service infection data.

The audit was undertaken in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost was $260 000.

1.6 Report structure

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines patient outcomes of infection prevention and control strategies and performance management activities.

- Part 3 examines the supporting systems for infection prevention and control.

2 Patient outcomes and performance management

At a glance

Background

Analysis of patient outcomes data can help inform practice or system change to prevent more infections. Health services and the Department of Health (the department) must manage infection prevention and control performance to achieve better outcomes for patients.

Conclusion

Victoria performs well against national infection rates. State-level infection control data over the past decade show improvements against some indicators. However, a lack of data analysis and effective performance management means the department and health services could be missing opportunities to further reduce infection rates.

Findings

- Infection rates for hip and knee replacements have reduced in the past 10 years.

- Hand hygiene compliance rates vary among healthcare worker groups.

- The department does not identify trends in infection control data over time.

- The department has not effectively managed its service agreement with the Victorian Healthcare Associated Infection Surveillance System Coordinating Centre.

Recommendations

That the Department of Health:

- uses the infection control data it collects to inform future strategy on infection control

- identifies and appropriately manages health services with persistent or recurring poor infection control performance.

That health services develop and implement targeted strategies to address persistent underperformance in hand hygiene compliance among relevant healthcare worker groups.

2.1 Introduction

Many variables may contribute to a patient acquiring an infection in a hospital setting, such as a pre-existing condition, clinical practice and hand hygiene, or environmental cleanliness. Health services can use infection surveillance as a trigger to further investigate the causes of infections. Monitoring infection trends can also provide an indication of system or clinical practice failures and weaknesses, and inform performance management activities.

The Department of Health (the department) is increasingly reliant on performance and patient outcomes data as objective measures of health service performance. Comprehensive analysis of health service performance data can provide important indicators of successful program implementation and of emerging issues and risks. It can also help identify services that need targeted performance management.

2.2 Conclusion

Over the past decade, infection control outcome data show that infection rates have improved against some indicators but remained static on others. There are a range of variables that could be influencing these results, such as differing surveillance practices or patient characteristics among health services, which the department should investigate further. The department is not aware of common areas in need of improvement, or health services that are persistent outliers in need of targeted performance management, as it has not effectively analysed the data it collects.

Each of the audited hospitals has set clear expectations for all staff and contractors regarding infection control responsibilities. Audited hospitals also undertake a range of organisational compliance and performance monitoring activities. Statewide data show that health services have achieved some improvement in medical staff performance in relation to hand hygiene compliance but further improvement is required.

2.3 Patient outcomes

2.3.1 National level patient outcomes

Public reporting of infection control-related patient outcomes occurs at state and national levels. The Productivity Commission's annual Report on Government Services publishes rates of Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia (SAB) infections by jurisdiction, while the Commonwealth Government's My Hospitals website publishes identified data by hospital on SAB infection rates and hand hygiene compliance rates.

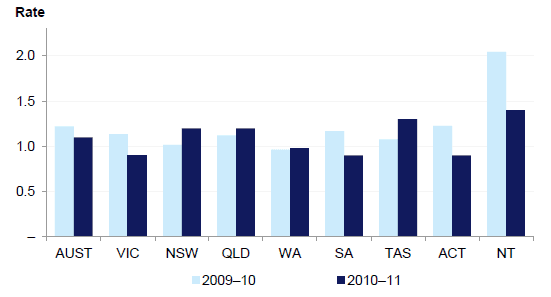

Figure 2A shows that in 2010–11, Victorian SAB infection rates compared well against other Australian jurisdictions, and were below the national average of 1.2 infections per 10 000 patient bed days.

Figure 2A

SAB infection rates by jurisdiction per 10 000 patient days, 2009–10 and 2010–11

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Report on Government Services data.

In 2010–11, all states and territories reported rates below the national benchmark of 2.0 per 10 000 patient days.

2.3.2 State-level patient outcomes

The department publishes statewide infection control indicators and patient outcomes through the Victorian Healthcare Associated Infection Surveillance System (VICNISS) annual reports. These reports include a range of indicators such as blood stream infections, healthcare-associated diarrhoea—commonly caused by a clostridium difficile infection (CDI)—surgical site infections (SSI), hand hygiene compliance and staff immunisation rates.

Rates of CDIs have increased since surveillance began in early 2010–11. The department and VICNISS suggest the increase could be due to increased awareness and testing among health services. Rates of SAB infections appear to be decreasing since surveillance began in early 2010–11. More data for both of these indicators need to be collected before a definite trend can be fully identified. The department would also need to further investigate to understand the reasons for these results.

Surgical site infections

Health services may voluntarily submit SSI rate data to VICNISS on 15 surgical procedures. However, submission of data on heart bypass, hip replacement and knee replacement surgeries is compulsory as these are the most commonly performed procedures that carry a high level of infection risk. The permanent introduction of foreign objects into the joint or organ space increases the risk of infection.

VICNISS and the department collect and report SSI rates according to internationally validated risk categories, determined by patient health and surgery type criteria, and location of infection—either deep or superficial. The rates reported below comprise all risk categories to give the overall infection rate.

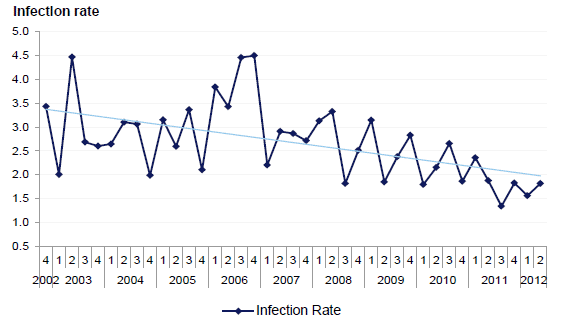

VICNISS data reveal that SSI rates for hip and knee replacements have significantly declined since late 2002. Figure 2B shows that the SSI rate for hip replacement patients was 3 per cent in 2003 and by 2011 had decreased to 1.8 per cent. This is the equivalent of approximately 42 fewer patients in 2011 suffering from an SSI infection following hip replacement surgery compared to 2003.

Figure 2B

Quarterly hip replacement SSI rates per 100 procedures

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on VICNISS data.

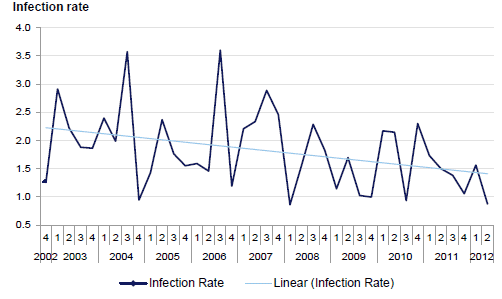

Figure 2C shows the SSI rate for knee replacement patients was 2.2 per cent in 2003 with a statistically significant decline to 1.4 per cent in 2011. This is the equivalent of 22 fewer patients suffering from a SSI infection following a knee replacement than was the case in 2011.

Figure 2C

Quarterly knee replacement SSI rates per 100 procedures

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on VICNISS data.

Further analysis of SSI data reveals that all improvements are among patients in the lowest risk category (i.e. no other health complications, and/or a short surgical procedure). Rates among patients in higher risk categories have not improved.

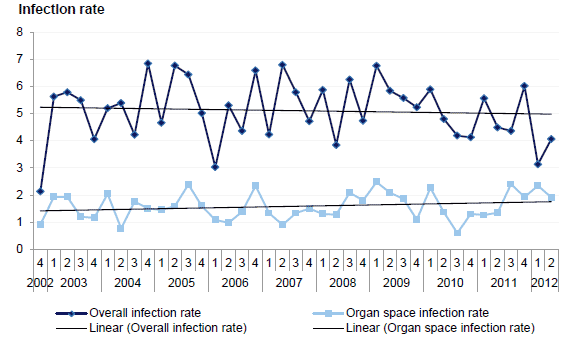

Figure 2D shows that the overall SSI rate for heart bypass patients has remained static at approximately five per 100 procedures. The rate for deep or organ space infections has also remained static at approximately 1.6 per 100 procedures. The department advises that this is within the expected range according to the Australian and New Zealand Society of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgeons. Figure 2D shows a slight increase in this rate but it is not statistically significant.

Figure 2D

Quarterly heart bypass SSI rates per 100 procedures

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on VICNISS data.

The higher overall rate could relate to heart bypass patients being less well than joint replacement patients and consequently more susceptible to infections. However, this does not explain why the statewide rate would not reduce over time.

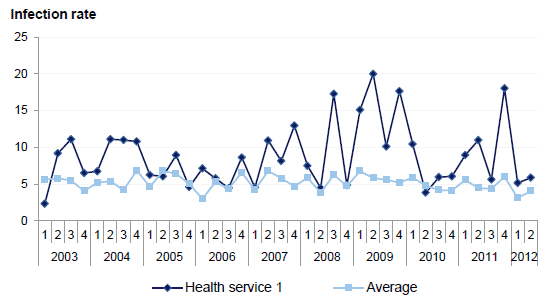

Further analysis of these data reveals a high level of variation across six of the health services conducting heart bypass surgery. For example, Figure 2E shows much higher rates of infection following heart bypass surgery at health service 1 since 2007 compared to the state average. Health service 1 was not one of the audited hospitals.

Figure 2E

Quarterly heart bypass SSI rates per 100 procedures – health service 1 and the state average

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on VICNISS data.

In 2011, the average SSI rate at this health service was 10.9 per 100 procedures, with a peak in the last quarter of 18 per 100 procedures. The state average for the same year was 5.11 per 100 procedures. The department identified the high SSI rates at health service 1 during the first and second quarters of 2011 through its routine quarterly performance monitoring regime. It sought an explanation for the results from this health service and a plan of action to reduce rates in the future. Through its investigations, the health service identified an issue with patient skin preparation prior to surgery. Health service 1 changed the skin preparation and subsequently observed a drop in infection rates.

2.4 Performance monitoring and management

Compliance and performance monitoring provides assurance to the department and health service boards that infection prevention and control systems are functioning and achieving intended outcomes. It is important that the department and health services effectively manage underperformance so that patient outcomes are not adversely affected.

2.4.1 Departmental performance monitoring

As described in Part 1, the department maintains a quarterly performance monitoring regime which is set out in the Victorian Health Services Performance Monitoring Framework. In addition to this, the department's Quality, Safety and Patient Experience Branch (the branch) effectively monitors infection control indicators for all health services. In instances of underperformance, the branch requires services to develop an action plan detailing any practice changes designed to improve results. However, the department does not analyse VICNISS infection control performance indicators over time to identify systemic issues, emerging risks or persistent outliers and develop targeted strategies to improve performance.

Victorian Healthcare Associated Infection Surveillance System

The VICNISS Coordinating Centre is responsible for collecting and disseminating infection control data and providing education and support to health services participating in the surveillance program. However, the department has not effectively managed its service agreement with the metropolitan health service auspicing the VICNISS Coordinating Centre. This has led to a lack of clarity surrounding the governance of the coordinating centre, a gradual expansion in the scope of the centre's activity beyond its core funded activity, and a lack of timely access by the department to quarterly data.

There are also delays in the release of VICNISS annual reports, which compromises transparency and public accountability for this aspect of health service safety and quality. The latest publicly available VICNISS report is from 2009–10. Due to delays in releasing the 2010–11 report, the department and VICNISS are preparing to release a combined 2010–12 report. The department anticipates it will publish this report in August 2013.

In 2011, the department reviewed the VICNISS operational model. The report made six recommendations relating to the governance and scope of VICNISS. The department has commenced preliminary work to address these recommendations. However, it has not yet resolved the underlying issues and timely access to data. This lack of resolution reduces the value the department can derive from its $1.5 million annual investment.

2.4.2 Health service monitoring of staff and contractors

All audited hospitals have clear expectations regarding infection control responsibilities for all staff and contractors through position descriptions, service agreements, induction training, staff communications, posters and signage. To make sure staff are meeting these expectations, health services undertake a range of organisational compliance and performance monitoring activities. Health services have achieved some improvement in medical staff performance in relation to hand hygiene compliance, but more needs to be done to drive improvement in hand hygiene culture across the health sector.

Compliance monitoring

All audited hospitals undertake a range of infection control-related compliance monitoring activities, including:

- daily infection control ward rounds, where infection control staff visit each ward or unit and monitor staff management of patient infections

- hand hygiene compliance audits, three times per year

- annual infection control audits of each ward or unit—which include looking at use and disposal of single use devices and personal protective equipment

- topic specific, time-limited audits or studies focused on particular areas of practice, such as the use of intravenous drips.

Common gaps in monitoring include coverage of aseptic technique and, to a lesser extent, antimicrobial stewardship—using antibiotics appropriately to prevent the spread of drug resistant infections:

- All audited hospitals have only recently commenced developing procedures for monitoring tools for aseptic technique.

- Hospitals C and D have well established antimicrobial stewardship systems. Hospital B has recently implemented its system and Hospital A has recently developed, but not implemented, theirs.

- In 2000, the department's Guidelines for Infection Control Strategic Management Planning acknowledged the limited capability of small regional and rural hospitals to maintain antimicrobial stewardship systems, due to reduced access to infectious diseases expertise to inform the appropriate use of antibiotics. However, the department did not develop an initiative to target this known gap.

Hospitals A and D also monitor adherence to infection control policies and procedures as part of annual staff performance appraisals. Reference to infection control in this context indicates clearly to all staff and their managers that the organisation places a high priority on this aspect of practice.

Managing underperformance

All audited hospitals provide opportunities for formal and informal feedback and performance management through supervision, daily infection control ward rounds, periodic infection control audits and annual performance reviews. Efforts to improve performance of medical staff in hand hygiene compliance have resulted in increased rates. However, more needs to be done to improve compliance among lower performing healthcare worker groups.

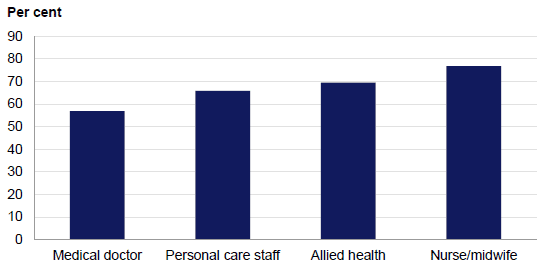

Statewide hand hygiene compliance results indicate a need for greater consistency of compliance among healthcare workers, particularly given its relevance to patient safety. Figure 2F shows the degree of variation among healthcare worker groups. In 2011, the department's target rate for health services was 65 per cent. In July 2012, the target rate increased to 70 per cent.

Figure 2F

2011 hand hygiene compliance rates by health care worker occupation

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Hand Hygiene Australia data.

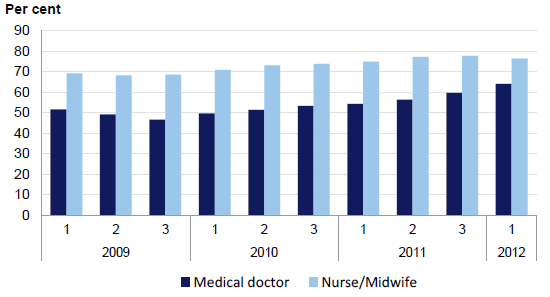

Figure 2G shows that since at least 2009, medical doctor's performance has been improving but is still lower than their nursing colleagues, as seen by the results from compliance audits which are undertaken three times per year.

Figure 2G

Statewide hand hygiene compliance rates: nurses and medical doctors

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Hand Hygiene Australia data.

The Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infection in Healthcare indicate that while not sufficient on its own, good hand hygiene is an effective and relatively simple way to reduce the risk of spreading infections. The importance of maintaining a high rate of hand hygiene compliance among all health care workers for the purposes of effective infection prevention and control means that targeted effort is needed to close the gap more quickly.

Recommendations

That the Department of Health:

- uses the infection control data it collects to inform future strategy on infection control

- identifies and appropriately manages health services with persistent or recurring poor infection control performance.

That health services:

- develop and implement targeted strategies to address persistent underperformance in hand hygiene compliance among relevant healthcare worker groups.

3 Supporting systems

At a glance

Background

Policies and training help health services to embed infection prevention and control systems into daily activities. The Department of Health (the department) can support health services by articulating targeted and strategic priorities to reduce infections.

Conclusion

The department would better support health services to continue improving infection rates by clearly articulating and communicating current and targeted infection control priorities. While audited hospitals have effective systems to support infection control, they do not formally consider infection risks when prioritising maintenance and asset replacement.

Findings

The department:

- has a draft infection control strategy that requires further development to provide clearly articulated priority actions to health services

- does not receive comprehensive state-level expert advice on infection control

- does not consider a statewide perspective when planning capital projects

- has not evaluated its rural regional infection control support system.

Of the four audited hospitals:

- three have ad hoc refresher training topic and staff group selection

- three lack a formal risk-based prioritisation tool for managing maintenance jobs.

Recommendations

That the Department of Health:

- accesses required expert advice and uses it to inform future strategy on infection control

- includes targeted initiatives to all known areas of underperformance in infection control in its future infection control strategy

- evaluates the effectiveness of the rural infection control consultant models.

That health services factor in infection control risks when prioritising maintenance and asset replacement.

3.1 Introduction

Effective infection prevention and control is critical to providing a safe environment for patients and healthcare workers. To achieve this, health services need guidance and support to set consistent expectations and to guide staff practice. They need to have good governance systems with clear lines of accountability. Health services need a comprehensive approach to risk assessment and effective participation in quality assurance accreditation programs in order to gain assurance that they are managing infection prevention and control well. They should also use a risk-based approach to prioritise access to, and maintenance of, facilities such as isolation rooms.

The Department of Health (the department) should support health services in maintaining a systematic approach to prevention and control of healthcare-associated infections (HAI) by seeking and acting on expert advice, implementing effective strategic policy and capital investment planning, and providing additional infection prevention and control support where necessary.

3.2 Conclusion

The department has provided effective support to health services, including guidelines and standards, monitoring, reporting, and advice. However, the department would be in a stronger position to support health services by providing clearly articulated priority actions as part of a formal strategy, maintaining a statewide perspective on health service infection control capacity to inform capital planning, and carrying out robust project and program evaluations. Further, the department has not evaluated the effectiveness of its regional infection control staffing positions. Different service delivery models and a recent funding model change have also contributed to a lack of transparency, consistency, and differing expectations of service provision between departmental regions and health services.

The audited hospitals have effective systems to support infection prevention and control, such as comprehensive policies and procedures, training and contract management arrangements for facilities' services that reliably identify infection control issues. However, there are gaps in the systems for assessing and registering infection control risks. Consistent, risk-based decision-making is particularly important in hospitals where isolation capacity is low to maximise the equity of access to scarce resources.

3.3 Department of Health

To develop well-targeted, evidence-based policy, the department requires advice from experts in the Victorian health system. It should use this advice to identify strategic directions to guide efforts to improve infection prevention, control systems and capacity in all health services.

Victoria has established a mature infection control support system for health services based on guidance, monitoring and reporting. However, the department has not finalised its strategy, nor communicated a clear strategic vision of infection control priorities to health services, to drive overall improvements in future performance.

3.3.1 Infection control system

The department has provided health services with a good foundation for embedding infection prevention and control into their daily activities by developing standards, guidelines, programs and a surveillance system. Other jurisdictions have since adopted a number of these initiatives. For example, the Victorian Quality Council's hand hygiene program formed the basis for the National Hand Hygiene Initiative. The Australian Capital Territory has adopted the Cleaning standards for Victorian public hospitals as a basis for assessing environmental cleanliness.

3.3.2 Strategic direction

The department's last infection control strategy—Start Clean: Victorian Infection Control Strategy 2007–11 (Start Clean)—concluded in 2011. Since then, the department has introduced infection control related indicators into the health service performance monitoring framework and quarterly Budget Expenditure and Review Committee. The department has also reviewed the Victorian Healthcare Associated Infection Surveillance System to inform a realignment of its role and health service infection monitoring and surveillance, to activities taking place at the national level. While the intent of this activity has been to promote improvements in infection rates and enhance accountability for safety and quality of care between the department and health services, it does not represent a clear articulation of strategic priorities and actions to guide health services in the medium term.

The department has also developed a successor to Start Clean which is currently in draft but the government has not yet committed funding for the strategic initiatives. The proposed initiatives are generic in nature, focusing on hand hygiene compliance among all healthcare workers, a review of hospital cleaning audits, increasing health care worker immunisation, and antimicrobial stewardship, with a particular focus on access to infectious diseases expertise for small rural hospitals.

The department has sought feedback from the sector on cleaning standards and identified the need for a review of the auditing program, based on this work. However, the department has not applied a rigorous evidence base to support the remaining initiatives. For example, there is little or no analysis of infection rate and performance data to identify other areas in need of improvement, and the department does not target known areas of underperformance which are common to many health services—such as increasing hand hygiene compliance rates among lower performing healthcare worker groups.

Evaluation

The department did not undertake a rigorous evaluation of the Start Clean strategy. In 2010, the department produced an implementation report for Start Clean which noted that hand hygiene compliance rates had improved over the period of the strategy. However, it did not assess whether there had been any improvement in infection control-related outcomes for the $10 million invested through strategy initiatives. The report also did not identify areas for future development or improvement. The implementation report was a missed opportunity to develop an evidence base to inform future strategic directions.

3.3.3 Expert advice

In March 2013, the department established the Ministerial Expert Panel on Hand Hygiene. While this is a positive initiative, the department still lacks comprehensive state-level advice to inform the development of strategic priorities and its participation in national committees. The department disbanded its former infection control advisory committee in 2010.

The department obtains expert advice on infection control through its participation on three national committees. Figure 3A outlines these committees and their roles.

Figure 3A

National infection control-related committees

| Committee | Role |

|---|---|

|

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) Inter‑Jurisdictional Committee (IJC) |

|

|

Healthcare Associated Infection (HAI) Technical Working Group |

|

|

Hand Hygiene Advisory Committee |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

These national committees have a role to play in preventing and managing infections in healthcare, but access to state-level expert advisory groups would also facilitate consistent and effective implementation of national strategies at the local level and contribute to the development of a successor strategy to Start Clean.

Victorian Advisory Committee on Infection Control (VACIC)

The department based its decision to disband the Victorian Advisory Committee on Infection Control (VACIC) in 2010 on the findings of a review into a number of departmental advisory committees, including VACIC. The review found that committee members were unclear about the purpose of the committee and that informal working parties associated with VACIC and departmental staff were ultimately responsible for developing outputs, rather than VACIC itself.

The department acknowledges there is a need for local infection control advice. It has identified three infection control topics that require expert input, including hand hygiene, antimicrobial stewardship and a review of the cleaning standards, and has commenced a program to inform and support the formation of such groups. This program includes:

- developing a set of standardised terms of reference (TOR) for expert advisory panels, and an orientation pack for prospective members that includes a background paper to government, working with government, code of conduct and confidentiality agreement

- reviewing how it engages with stakeholders for public health-related issues, including infection prevention and control

- convening topic-specific expert panels, at least twice per year and more frequently if necessary, to contribute to emerging issues.

The department has developed standardised TORs and the orientation pack. However, personnel changes have meant that it has not convened all of the panels, and work on reviewing public health stakeholder engagement has not taken place.

In addition to the Ministerial Expert Panel on Hand Hygiene, the Quality Safety and Patient Experience branch plans to establish a working party to inform the review of the hospital cleaning standards by June 2013.

3.3.4 Capital planning and infection control

The Capital Projects and Service Planning branch of the department is responsible for health service planning, development and delivery of building projects, building-related policy and standards, and reporting on the department's asset base to central agencies.

For every major capital project, the department and the relevant health service jointly develop a service plan. The service plan details the health service's current infrastructure and its capacity to provide services, and recommends capital development needs. The plan is informed by the department's Design Guidelines for Hospitals and Day Procedure Centres, which set out requirements for the provision of infection control capacity, and an assessment of the health service's current and future service demand, based on their local catchment characteristics and their service role in the health system. However, this assessment does not include a current statewide view of infection control capacity. The department collects bed census data on a monthly basis which provides an overview of hospital system capacity, but it does not routinely collect data on the isolation capacity at each health service. This limits the department's ability to consider and plan for statewide systemic needs in responding to infection control issues.

3.4 Health services

Victorian health services are autonomous organisations governed by boards of management which are responsible for the safety and quality of the care they provide. Boards and executives gain assurance of the safety and quality of care through clear lines of accountability, executive leadership, comprehensive risk assessment and management, participation in quality assurance assessments—such as accreditation schemes—and setting clear expectations for staff through training and policy guidance.

All audited hospitals have comprehensive, current and accessible infection control policies and procedures, and clearly defined expectations set out in staff position descriptions. This is supported by infection control signage and other prompts, such as prominently displayed hand rub, and by providing consistent messages to staff. While training and planned maintenance processes are adequate, there are opportunities to improve these through a comprehensive approach to training and more transparent prioritisation of maintenance tasks.

3.4.1 Infection control governance

Audited hospitals have clearly defined infection control governance and accountability structures. However, not all audited hospitals include infection control in their organisational risk registers, and a focus on compliance-based accreditation programs has led to gaps in assurance systems.

Organisational risk assessment

All audited hospitals include staff occupational exposure to infection risks in organisational risk registers. However, only two of the four audited hospitals include risks associated with patient infections on their organisational risk register, despite the implications of negative patient outcomes and unnecessary treatment costs.

In 2000, the department produced the Guidelines for Infection Control Strategic Management Planning. While the department no longer requires health services to maintain infection control management plans, the guidelines recommended that health services incorporate infection control into organisational risk management systems.

Under the 2005 Better Quality, Better Health Care: A Safety and Quality Improvement Framework for Victorian Health Services, the department requires health service boards to have infection control, as one of the key areas of clinical risk, linked to strategic and business planning processes. A comprehensive organisational risk assessment is a crucial element for informing these planning processes.

Figure 3B presents a case study of a widely acknowledged infection control risk that was not listed on the organisational risk register.

Figure 3B

Case study – the organisational risk register

Hospital A is an old facility with a lack of adequate isolation facilities on the wards. In one ward, two isolation rooms have a shared ensuite. When both rooms are in use, staff have to choose one of the isolated patients—the one deemed to be at lower risk—to use toilet facilities shared with the non-isolated patients on the ward, leaving the ensuite facilities for the higher-risk patient.

This means that staff are unable to adequately isolate patients when clinically appropriate, thus posing infection control risks to other patients and staff. However, the hospital has not recorded these risks on the organisational risk register.

Infection control staff and executive management demonstrated an awareness and understanding of these risks. They discussed proposed solutions with the audit team. All the proposed solutions required considerable capital expenditure. However, without recording these risks on the organisational risk register the health service board cannot formally consider them when making capital expenditure decisions.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Accreditation and good governance

The department requires that all health services maintain quality assurance accreditation as a condition of funding. Accreditation processes are a compliance assessment of health service governance and quality improvement systems against a detailed set of criteria.

Health services have come to rely on these regimes to guide their activity, at the risk of not developing comprehensive systems based on good governance principles. This is evident in the case of compliance monitoring regimes for aseptic technique. Aseptic technique is a standard part of clinical practice that involves undertaking invasive procedures without contaminating the equipment.

The department and health services systematically identified and acknowledged gaps in compliance monitoring of this practice in anticipation of the new National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards (national standards). In 2012, health services undertook a gap analysis to assess the readiness of health services to implement the national standards. The department collated this information to distribute to health services to inform their understanding of strengths and weaknesses in relation to the national standards, and to facilitate improvements in performance and quality of care. In relation to standard three—preventing and controlling healthcare associated infections—over half of all services were found to be noncompliant in two key areas—monitoring staff compliance with aseptic technique procedures and having systems in place to increase compliance.

Infection prevention and control staff at each of the audited hospitals have action plans in place to implement aseptic technique compliance monitoring programs within the next 12 months. This activity is tied to the criteria under the national standards.

3.4.2 Training

All audited hospitals provide staff with infection control training through mandatory organisational induction, targeted refresher and general training opportunities. However, methods of topic selection and delivery of refresher training vary from ad hoc to planned across the four audited hospitals. Where hospitals provide training on an ad hoc basis there is a risk that they might miss groups of staff or particular topic areas.

Induction training

All audited hospitals deliver infection control training as part of mandatory organisational induction training. While the content varies across health services, they all cover standard and additional precautions, hand hygiene, staff health and immunisation.

In addition to mandatory induction training:

- all hospitals deliver infection control training for medical interns

- Hospitals A, B and D deliver mandatory online hand hygiene training modules to all staff—ward and unit managers monitor staff completion rates

- Hospital C does not mandate hand hygiene training.

Tailored training

All audited hospitals provide general or targeted refresher training in infection control, tailored to clinical and facilities staff. However, methods for topic selection vary:

- Hospital D maintains an annual infection control training schedule.

- Hospitals A, B and C rely on requests for training from unit or ward managers. They also identify training needs based on feedback and observations during daily ward rounds to inform topic selection and timing of refresher training.

The ad hoc approach raises the risk of staff groups or topic areas not being adequately covered. The audit team surveyed 10 clinical and 10 facilities' staff at each of the audited hospitals on basic infection control knowledge, such as describing the five moments of hand hygiene and the appropriate use of personal protective equipment to prevent the spread of infection. Figure 3C shows the percentage of correct responses to the survey questions.

Figure 3C

Basic infection control knowledge survey – percentage of correct answers

|

Staff |

Hospital A |

Hospital B |

Hospital C |

Hospital D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Clinical |

||||

|

Medical doctors |

77 |

77 |

70 |

70 |

|

Nurses |

70 |

70 |

68 |

58 |

|

Allied health |

70 |

80 |

67 |

77 |

|

Facilities |

||||

|

Orderlies |

95 |

93 |

97 |

100 |

|

Cleaners |

96 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The results indicate variation in basic infection control knowledge among and between clinical and facilities staff. Infection control unit staff at all audited hospitals reported challenges in fitting training into or around already busy training schedules, particularly for junior medical staff. The planned approach supports comprehensive coverage of topics and staff groups, and provides some organisational assurance that all staff receive relevant infection control refresher training.

3.4.3 Management of isolation rooms

The Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infection in Healthcare recommend that where isolation rooms are in short supply, hospital staff should prioritise access based on the risk of a patient transmitting or acquiring infection. Demand for isolation rooms at all audited hospitals is high.

Isolation rooms can be a single room with one bed, hand basin and ensuite, or a room with special air handling capability—known as a negative pressure room. A single room helps prevent transmission of infections, such as gastroenteritis or diarrhoea, by reducing patient and staff contact with droplets of bodily fluids. A negative pressure room helps prevent the transmission of infections, such as chicken pox or tuberculosis, by reducing the risk of spreading air borne droplets or particles which other patients and staff could inhale or ingest.

Infection control staff at all audited hospitals identify and assess the infectious status of patients during daily ward rounds. Three of the four audited hospitals also use a formal risk assessment to inform prioritisation of access to isolation rooms. Figure 3D shows the different risk assessment and prioritisation approaches used in the four audited hospitals.

Figure 3D Isolation room decision-making and prioritisation

|

Hospital |

Informal risk assessment |

Documented criteria for isolation |

Formal risk assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Hospital A |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Hospital B |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Hospital C |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Hospital D |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The lack of a formal risk assessment means that staff decision-making is not transparent and may not be consistent. Consistent, risk-based decision-making is particularly important in hospitals where isolation capacity is low. This can help maximise the equity of access to scarce resources.

3.4.4 Building maintenance and construction

Maintenance and infection control

Maintenance of infrastructure and equipment, such as isolation room door seals and operating theatre air handling systems, is critical to effectively prevent and control infections. The Maintenance standards for critical areas in Victorian health facilities recommends that hospital maintenance departments engage with infection prevention and control units to assess infection control risks.

All four audited hospitals undertake a formal or informal infection control risk assessment prior to commencing a maintenance job. However, three of the four audited hospitals have no formal weighting of infection control or other risks for prioritising maintenance jobs. Resources for maintenance are often limited. Health services need to make sure they have a reliable system in place for prioritising the jobs most critical to patient and staff safety.

Prior to commencement of a maintenance job, infection prevention and control unit staff at all audited hospitals provide maintenance staff with an infection control risk assessment and mitigation advice, such as preferred fittings for ease of cleaning or timing of works to minimise patient contact. At three of the four audited hospitals, infection prevention and control unit staff, together with other relevant units such as occupational health and safety, provide this advice through a formal, documented system and sign-off on jobs once completed. Hospital A has a more informal process than the other audited hospitals.

Three of the four audited hospitals use an electronic system to manage the scheduling of planned maintenance for critical infrastructure. This is known as the Building and Engineering Information Management System (BEIMS). At the time of audit fieldwork, Hospital A was in the process of implementing BEIMS and still maintains a manual system. BEIMS provides assurance that the hospital maintains this infrastructure in accordance with Australian Standards or manufacturers' requirements. However, three of the four audited hospitals have no formal risk weighting to inform prioritisation of maintenance jobs as the system issues them.

Construction and renovation

Infection prevention and control staff at three of the four audited hospitals are actively engaged in planning and monitoring major and minor capital works. Hospital A had not undertaken any recent construction or renovation work involving the infection prevention and control unit.

3.5 Infection control in rural hospitals

Many small rural hospitals have limited infection prevention and control capacity. Hospitals might have sufficient staffing budget to employ one infection control practitioner or they might only be able to fund a partial position. In such cases, equitable and transparent distribution of regional infection control support is particularly important.

3.5.1 Regional infection control practitioners

There is a lack of transparency and consistency in the provision of additional regional infection control support for rural hospitals due to differences in service delivery models and changes to the funding model.

Since 2001, the department has supported regional health services and small rural hospitals through the provision of funding for two full-time equivalent (FTE) infection control consultant (ICC) positions for each of the department's five non-metropolitan regions. As part of their regional support role, the regional ICCs provide a standard range of services to the hospitals in their regions. These include:

- advice on developing infection control policies and guidelines

- staff education

- assistance with the conduct of annual infection control audits.

ICCs provide other support or advice in addition to these standard services as required. They also voluntarily meet bimonthly as the statewide Rural Infection Control Practice Group (RICPRAC) to share good practice, problem solve, develop and share standardised resources, and participate in benchmarking projects.

The model for provision of regional infection control support services varies across the non-metropolitan regions. In 2001, each departmental region developed, in consultation with relevant stakeholders, a service delivery model intended to best suit local needs. Figure 3E outlines each of these models.

Figure 3E

Regional infection control consultant models

|

Region |

Model |

Funding source |

|---|---|---|

|

Barwon South West(a) |

Two sub-regional models:

|

Two regional health services pay the consultancy firm for regional support One regional health service |

|

Gippsland |

Funding for two FTE ICCs is disbursed across 11 health services in the region. This funding contributes to the employment of infection control staff in these services. |

Dispersed between 11 health services |

|

Grampians |

Two FTE ICCs, located at Horsham and Ballarat departmental regional offices, provide infection control support to health services on a free consultancy basis. |

Departmental regional office operating budget |

|

Hume |

1.5 FTE allocated to employ two ICCs to provide an independent, free consulting service to 17 public health services and hospitals in the region. 0.5 FTE allocated to an 'operational budget' to support the region. The service operates under the auspices of a major regional health service, but the practitioners are not employed there and have no operational involvement in that service's infection control unit. |

One regional health service |

|

Loddon Mallee |

1.5 FTE allocated to employ two ICCs and 0.5 FTE allocated to administrative support for the region. The ICC responsibilities are split between the employing health services and supporting other health services in the region. The split role is formally documented in position descriptions. |

One regional health service |