Tourism Strategies

Overview

The government spends in excess of $100 million each year supporting tourism related initiatives.

In 2006, it released a 10 year Tourism and Events Industry Strategy. The strategy committed to an approach known as ‘destination management’, involving high levels of cross-government collaboration and multi‑agency initiatives.

Tourism Victoria (TV), in its role as the government’s lead tourism agency, effectively implemented the aspects of the strategy in its own core business areas. It is also a proactive advocate for Victoria’s tourism industry.

However, the lack of a comprehensive whole-of-government implementation plan or centralised management of cross-government initiatives meant that it did not make as much progress on broader-based, multi-agency actions.

Further, TV did not effectively evaluate the strategy. The key performance indicators and data TV collected are not capable of measuring the performance of the strategy’s intended outcomes.

The government’s 2020 Tourism Strategy, released in July 2013 is also a whole‑of‑government strategy. However, the lack of proper evaluation of the 2006 strategy means that any lessons learned from its implementation are unlikely to inform and improve the new strategy’s implementation.

It also remains unclear how TV will address the absence of centralised management and evaluation of the activities of multiple government agencies.

Tourism Strategies: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER December 2013

PP No 291, Session 2010–13

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Tourism Strategies.

The audit assessed the effectiveness of strategies designed to develop and support tourism and events in Victoria.

The report highlights the need to recognise and apply the lessons from the 2006 tourism strategy or risk diminishing the effectiveness of the current 2013 strategy.

The report flags the need for critical improvements, including early, detailed planning—especially for actions requiring cross‑government action—and a rigorous evaluation framework, to understand how well the strategy is delivering on government's intended outcomes.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

12 December 2013

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Ray Winn—Sector Director Erin Barlow—Team Leader Michelle Tolliday—Analyst Paul O'Connor—Engagement Quality Control Reviewer |

Victoria continues to be an attractive destination for local, interstate and international visitors, drawn by its natural beauty and the diverse range of experiences and events on offer. Tourism is important to the state's economy and Australia's proximity to some of the fastest growing national economies means it has significant growth potential.

Successive Victorian governments recognised that realising this potential means standing still is not an option. Interstate and international competitors are working hard to improve tourism and Victoria needs to also improve what it offers potential visitors if it is to grow tourism's economic impact across the whole state.

Achieving this requires a coordinated effort across government and the tourism industry to attract new visitors, through branding and marketing, and win repeat visits because of the quality of the events, facilities and services on offer. The 10 year Tourism and Events Industry Strategy (2006 strategy) and Victoria's 2020 Tourism Strategy (2013 strategy) both recognised the breadth of action required across government and industry to sustain and improve Victoria's performance.

Weaknesses in effectively applying cross-government strategies and the timely and comprehensive measurement of performance, are consistent and repeated themes from VAGO's audits tabled between 2006 and 2012.

I examined the 2006 strategy and described the implications of my findings for improving the effectiveness of the 2013 strategy, released in July 2013. Tourism Victoria was responsible for implementing the 2006 strategy and retains this role for the 2013 strategy.

While I am pleased with the progress Tourism Victoria has made for parts of the 2006 strategy, such as branding and marketing, where it is directly responsible, I am concerned at the lack of or slow progress in those areas requiring effective cross-government action, such as infrastructure development, helping to improve industry skills and service standards and developing tourist destinations in regional Victoria.

The 2006 strategy had neither the governance mechanisms nor detailed and specific plans to clarify how government agencies would work together to achieve the strategy's intended outcomes.

In addition, while the trends in tourism visitor numbers and expenditure are positive, the absence of a comprehensive evaluation framework means it is unclear how the strategy's actions contributed towards the strategy's goals. In particular, the key performance indicators and data collected are not capable of measuring performance against the strategy's intended outcomes.

The government's recently implemented policy changes designed to encourage tourism infrastructure development in regional Victoria further highlight the need for an effective joined-up approach to manage the risks and realise the intended outcomes of the 2013 strategy.

My recommendations to Tourism Victoria about developing detailed and comprehensive implementation and evaluation plans and advising government about how best to manage the risks that materialised during the 2006 strategy, will, if applied, help address the weaknesses I have identified.

In this context I am concerned by the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation's lack of response to this audit and Tourism Victoria's partial acceptance of my first two recommendations which:

- fall well short of addressing the clear need for an effective platform for the whole-of-government implementation of the 2013 strategy

- will not provide comprehensive advice about how best to manage the risks that materialised during the 2006 strategy.

I have made further audit comment to this effect on page 42 of this report.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

December 2013

Audit Summary

Background

A rapid and sustained rise in the number of people traveling across the world has focused much greater attention on tourism and its contribution to regional and national economies. International arrivals across the world increased from a mere 25 million people in 1950 to more than 1 billion in 2012. They are expected to reach 1.8 billion by 2030.

Tourism in Victoria includes the activities of international, interstate and Victorian visitors attending major events and business conferences, and holidaying across the state. It also includes other activities, such as shopping, visiting friends and family and other personal activities, where these happen at a place outside of a person's usual environment.

Since 2006, the Victorian Government has released two tourism strategies:

- in October 2006, the 10 year Tourism and Events Industry Strategy (2006 strategy)

- in July 2013, Victoria's 2020 Tourism Strategy (2013 strategy).

Both strategies shared similar high-level goals and identified objectives and priority areas where agencies needed to act to achieve government's goals and objectives.

In terms of the roles of agencies in relation to the 2006 and 2013 strategies:

- the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation (DSDBI) led the development of the 2006 strategy and is now responsible for encouraging foreign students to enrol for post-secondary education in Victoria. DSDBI includes the former the Department of Business and Innovation, collectively referred to as 'the department' throughout this report.

- Tourism Victoria (TV)—which is both a business unit in the department and a statutory authority reporting to the Minister for Tourism and Major Events—managed the implementation of the 2006 strategy, led the development of the 2013 strategy and is responsible for its implementation.

This audit's objective was to examine the 2006 strategy and highlight the implications for the recently released 2013 strategy. Specifically, it examined whether the department and TV effectively:

- developed the 2006 strategy and were ready for its implementation

- implemented the 2006 strategy as intended

- reviewed and evaluated the 2006 strategy.

Conclusions

Overall VAGO found that the government's 2006 strategy has been partly effective. The development of the 2006 strategy and the high-level priority areas it identified were sound.

TV effectively implemented the aspects of the strategy in its core business areas of brand marketing, encouraging more direct air access to Victoria and advocating for Victoria's tourism industry at local, state and national levels.

However, the lack of a comprehensive whole-of-government plan or an overarching body to manage cross-government implementation meant that it did not make as much progress on broader-based, multi-agency initiatives.

Further, TV cannot be confident it is achieving the strategy's outcomes because:

- it did not adequately evaluate the strategy against its priority areas and high‑level goals

- the 2013 strategy has not been informed by a full review of the 2006 strategy's strengths and weaknesses.

TV analyses high-level indicators of the state of tourism in Victoria. These indicators of tourism's economic contribution and changes in visitation show positive trends and greater growth than for New South Wales (NSW) and Queensland, although growing tourism's economic contribution to regional Victoria remains a challenge.

There is uncertainty about how well these indicators measure tourism expenditure and visitation, and the absence of a well-defined evaluation framework means it is difficult to attribute any changes to the 2006 strategy's actions. In particular, estimates of tourism visits and expenditure by Victorians include some activity and spending that is unrelated to the strategy's actions. TV has not estimated the extent and significance of this and needs to do so.

The remaining performance information did not fully explain performance against the 2006 strategy's goals, objectives and priority areas because TV had not:

- set appropriate performance indicators to measure progress towards goals of Victoria becoming a leading regional destination, recognising the industry as a leading economic force, and growing the industry consistent with broader policy goals

- collected sufficient information to report on the outcomes for most of the strategy's 14 priority areas.

For the 2013 strategy, TV is at a more advanced stage in developing mid-level plans for how it will implement and evaluate the strategy than it was for the 2006 strategy.

However, the challenge remains to complete rigorous and comprehensive implementation and evaluation plans and to effectively implement and monitor strategies that require a whole-of-government approach. The importance of this is underlined because there are no specific mechanisms to help apply the strategy across government.

TV can address these planning issues but it needs to act quickly and decisively to do so.

Findings

Planning

The 2006 strategy was well prepared by the department and was based on sound evidence and extensive consultation. However, the department and TV were not ready to implement and evaluate the strategy when it was launched in October 2006.

In terms of implementation planning, the lack of readiness cannot be fully attributed to TV because the department documented detailed plans in February 2006 for publishing the strategy and making the organisational changes seen as essential for its success.

However, the government's decision to take a different approach to that recommended by the department and detailed in its implementation plan, meant that TV required additional time to undertake organisational restructures, skill acquisition and stakeholder engagement to develop an implementation plan for the 2006 strategy.

The department and TV had not developed an adequate evaluation framework when the strategy was released and had no detailed plans about how they would do this.

The same approach has been applied for the 2013 strategy and this lack of preparation risks the timely application and the effectiveness of the strategy.

VAGO's recommendations encourage TV to address these gaps for the 2013 strategy and to better prepare for the implementation and evaluation of future strategies.

Implementation

The implementation of the 2006 strategy was partly effective.

Priority areas for which TV was primarily responsible were adequately detailed in its implementation plans. However, the absence of plans to clearly guide the actions of multiple agencies meant that the implementation faltered for several priority areas where success depended on effective coordination across government.

TV has not thoroughly reviewed this issue nor provided government with advice on how best to manage these same implementation risks for the 2013 strategy.

TV needs to develop implementation and evaluation plans that are specifically suited to a whole-of-government strategy and it needs to advise government on the risks and how to best manage them.

Evaluation and review

TV did not effectively evaluate and comprehensively review the 2006 strategy and has therefore not consolidated and applied the lessons from it to the 2013 strategy.

The key overall indicator data collected and other performance indicators are not capable of measuring the achievement of the government's high-level goals or the intended outcomes of the 2006 strategy's priority areas.

TV has analysed useful information on expenditure and visitation but accepts that the survey it uses to do so has limitations. TV needs to better communicate the uncertainties embedded in these measures and better attribute changes to the strategy's actions.

Tourism expenditure and visitation information shows that Victoria has performed better than NSW and Queensland since 2006. However, it is not clear how these improvements are related to, or could be attributed to, the 2006 strategy's actions.

To date VAGO has not seen evidence of a radically different approach to evaluating and reviewing the 2013 strategy.

It would be a real source of concern if this remains the case because of the clear weaknesses in the approaches used for the 2006 strategy.

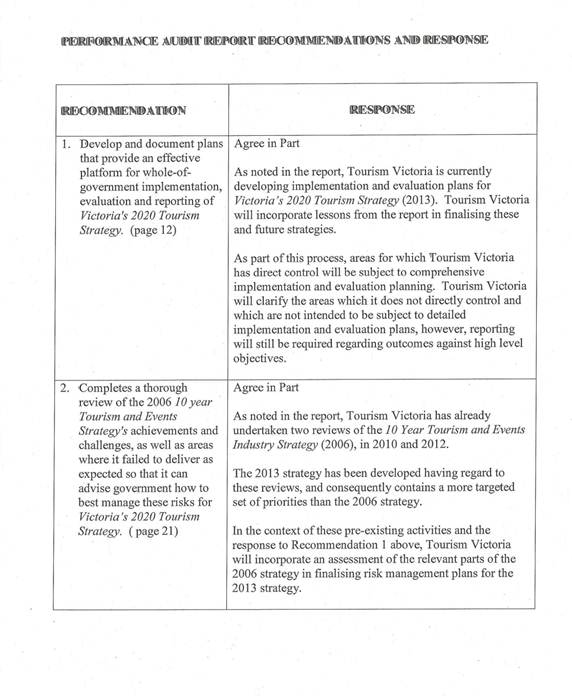

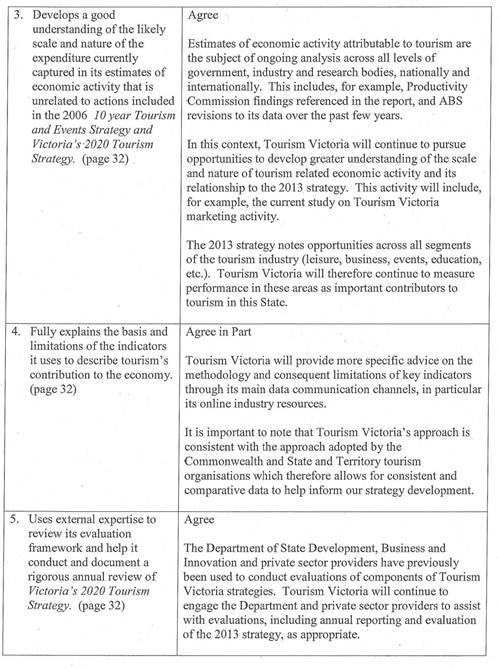

Recommendations

That Tourism Victoria:

- develops and documents plans that provide an effective platform for the whole-of-government implementation, evaluation and reporting of Victoria's 2020 Tourism Strategy

- completes a thorough review of the 2006 10 year Tourism and Events Industry Strategy's achievements and challenges, as well as the areas where it failed to deliver as expected so that it can advise government how to best manage these risks for Victoria's 2020 Tourism Strategy

- develops a good understanding of the likely scale and nature of the expenditure currently captured in its estimates of economic activity that is unrelated to actions included in the 2006 10 year Tourism and Events Industry Strategy and Victoria's 2020 Tourism Strategy

- fully explains the basis and limitations of the indicators it uses to describe tourism's contribution to the economy

- uses external expertise to review its evaluation framework and help it conduct and document a rigorous annual review of Victoria's 2020 Tourism Strategy.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation and Tourism Victoria with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

A rapid and sustained rise in the number of people travelling across the world has focused much greater attention on tourism and its contribution to regional and national economies. International arrivals across the world increased from a mere 25 million in 1950 to more than 1 billion in 2012. They are expected to reach 1.8 billion by 2030.

These trends have been mirrored in Australia with short-term visitor arrivals increasing by 35 per cent between 2002–03 and 2012–13.

Government agencies across the world define 'tourism' as the activities of all people visiting an area, where a 'visitor' is someone who takes a trip:

- to a place outside their usual environment―the geographical area where a person lives

- that lasts for less than a year

- for any purpose other than to be employed.

Tourism in Victoria includes the activities of international, interstate and Victorian visitors attending major events and business conferences, and holidaying across the state. It also includes other activities, such as shopping, visiting friends and family and other personal activities, where these happen at a place outside of a person's usual environment.

Based on this definition, Tourism Victoria (TV) estimates that tourism contributed $19.1 billion to the $322 billion Victorian economy in 2011–12 and employed 200 000 people.

1.2 Government tourism strategies

Two of the tourism strategies that government has released since 2006 are:

- the 10 year Tourism and Events Industry Strategy (2006 strategy) in October 2006

- Victoria's 2020 Tourism Strategy (2013 strategy) in July 2013.

These strategies share two of their three high-level policy goals for:

- Victoria to be a leading tourism destination in the (Asia-Pacific) region

- tourism to be a leading contributor to the Victorian economy.

However, they differ on the third policy goal. The 2006 strategy wanted tourism growth to be fully consistent with government's broader economic, environmental, cultural and regional objectives. The 2013 strategy focuses on Victoria being attractive to strong growth economies such as China, India and Indonesia.

Both strategies recognise the significant contribution and untapped potential of tourism for the Victorian economy, and that realising this potential remains a significant challenge:

- Cheaper, more convenient air travel not only gives overseas and interstate visitors easier access to Victoria, but also makes it easier for Victorians to visit interstate and overseas destinations.

- Other states and countries are also investing to attract visitors and this means Victoria needs to invest to maintain and increase its share of the visitor market.

- Tourism is subject to change because of factors that the state cannot control such as exchange rate fluctuations, major incidents that temporarily affect travel choices and fluctuations in the health of other nations' economies.

1.2.1 The 2006 strategy

To achieve its high-level goals―for Victoria to be a leading tourism destination, for the industry to be recognised as a leading economic force in the state and for growth to be consistent with government's broader goals―the strategy included 14 priority areas for action under the following four objectives:

- building upon existing strengths

- developing new strengths

- focusing on long-term growth opportunities

- strengthening the partnership between government and industry.

Figure 1A summarises these objectives and the strategy's 14 priority areas.

Figure 1A

2006 strategy—priority areas

Objective A: Building upon existing strengths |

|

|---|---|

1. |

Improving the branding and marketing of Victoria |

2. |

Major events—growing contribution of these events to the Victorian economy |

3. |

Aviation access—increasing the number of direct international flights to Melbourne |

Objective B: Develop new strengths |

|

4. |

Infrastructure development—meeting the needs of a growing tourism industry |

5. |

Investment attraction and facilitation—better prioritising tourism investment attraction |

6. |

Skills and service standards—increasing, sustaining and upskilling the tourism workforce |

7. |

Third generation customer conversion strategies—creating an effective internet presence |

Objective C: Focus on long-term growth opportunities |

|

8. |

Emerging international markets—targeting and developing high-growth markets |

9. |

Business events acquisition—growing the contribution of business events to the economy |

10. |

Regional destination development—attracting more visitors to regional Victoria |

11. |

Building synergies between tourism and international education |

Objective D: Strengthen the partnership between government and industry |

|

12. |

Promoting better decision-making—establish a Victorian Tourism and Events Advisory Council and a Tourism and Events Strategy and Policy unit |

13. |

Coordination and policy advocacy—integrate actions across government and the private sector in Victoria and advocate for the industry at a commonwealth level |

14. |

Communication—develop a communications strategy highlighting the importance of the tourism and events industry as a significant contributor to the economy |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office summary of 10 Year Tourism and Events Industry Strategy, 2006.

The 2006 strategy committed to a comprehensive new approach for all government actions affecting the industry known as 'destination management'. This approach aims to integrate land-use planning and development, marketing, visitor servicing, and community engagement across all levels of government and in partnership with the industry and the wider community.

The 2006 strategy aimed to grow the industry's contribution to the Victorian economy by 65 per cent over 10 years, from $10.9 billion to $18 billion a year, and in doing this create an additional 66 000 jobs.

The government recognised that better cross-government coordination would be critical for achieving these stretch goals, and included specific actions to do this under the objective to 'strengthen the partnership between government and industry'. The creation of an advisory council and dedicated strategy and policy unit, as described under the objective in Figure 1A, were seen as essential to achieving this.

In terms of measuring success, the 2006 strategy set as the ultimate test the achievement of an $18 billion industry and providing 225 000 jobs in Victorian industry by 2016. However, it recognised the need to develop performance indicators to measure progress against its high-level goals, objectives and each priority area.

The 2006 strategy said that agencies would work closely with peak bodies to measure Victoria's performance compared to other jurisdictions in critical areas such as online accreditation, service standards, sustainable tourism and ecotourism accreditation, direct aviation access, infrastructure provision and revenue from international visitors.

1.2.2 The 2013 strategy

The 2013 strategy is a refined and focused continuation of the 2006 strategy and retains the high-level focus of growing the industry's contribution to the economy. The strategy places a much greater emphasis on growing regional tourism because of the relatively weak performance in this market since 2006.

Its goal is to grow the industry's contribution from $19 billion to $34 billion by 2020, a 79 per cent increase, and to generate an additional 109 000 jobs. To do this it has set the seven priority areas for action listed in Figure 1B and the following objectives:

- increasing the focus on growth markets―China in the short to medium term and India, Malaysia and Indonesia in the medium to long term

- building stronger collaboration between government and the regions―to ensure statewide priorities are met, while actively supporting the regional tourism industry to address local issues

- increasing the tourism benefits of major and business events

- identifying and realising key tourism investments.

While clearly recognising that better collaboration is critical to success, the 2013 strategy, in contrast to the 2006 version, did not include specific actions and structures for strengthening collaboration across and between government and industry.

Figure 1B sets out the strategy's seven 'priority action areas'.

Figure 1B

2013 strategy—priority action areas

- Digital excellence―improving the state's capabilities across all digital platforms and encouraging local tourism operators to adopt capabilities such as online bookings.

- International marketing―raising brand awareness in key growth markets.

- Domestic marketing―positioning Melbourne as a creative and authentic destination and promoting regional Victoria to interstate and intrastate visitors.

- Major events and business events―attracting more major events and business events.

- Air services attraction―increasing direct air services from key growth markets.

- Investment attraction and infrastructure support―supporting investment, services and products aligning with consumers in key markets, for example Asia.

- Skills and workforce development―attracting more people to address shortages.

1.2.3 Time line of key events

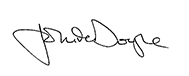

Figure 1C provides a time line of key events through the development and implementation of the 2006 and 2013 strategies.

Figure 1C

Time line of key events

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.3 Government agencies

This audit includes TV, the government's lead tourism agency. TV is both a business unit within the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation, and a statutory authority reporting to the Minister for Tourism and Major Events. The Department of State Development, Business and Innovation includes the former Department of Business and Innovation which developed the 2006 strategy—collectively VAGO refers to these as 'the department' throughout this report.

In relation to the 2006 and 2013 strategies:

- the department led the development of the 2006 strategy and is now responsible for encouraging foreign students to enrol for post-secondary education in Victoria

- TV managed the implementation of the 2006 strategy, led the development of the 2013 strategy and is responsible for its implementation.

The other agencies with roles directly relevant to tourism strategies are:

- the Department of Environment and Primary Industries—and before its amalgamation the Department of Sustainability and Environment and the Department of Primary Industries—Parks Victoria, which has relevant roles in managing state and national parks and infrastructure development

- the Department of Transport, Planning, Land and Infrastructure—and before its amalgamation the Department of Transport and the Department of Planning and Community Development—which was responsible for statewide planning

- the Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre, the Melbourne Convention Bureau and the Victorian Major Events Company, which acquires and retains major events for Victoria, and Arts Victoria and Sport and Recreation Victoria, which also bid for and stage major events

- local councils, which play a key role in supporting regional tourism.

1.4 Audit objective and scope

The objective of this audit was to examine the effectiveness of strategies, programs and initiatives designed to develop and support Victoria's tourism industry. The audit specifically considered whether:

- the 2006 strategy was effectively planned, developed and governed

- the benefits and outcomes of a selection of initiatives arising from the strategy were appropriately identified, measured and realised

- TV effectively governs to support the Victorian tourism industry and deliver intended outcomes.

VAGO also examined the implications of our findings about the 2006 strategy for the successful implementation of the 2013 strategy.

1.5 Audit method and cost

VAGO examined three projects implemented by TV as part of the 2006 strategy:

- the 2009–12 spa and wellness brand marketing campaign

- a project to increase the uptake of digital tools by regional tourism operators

- TV's tourism excellence grants program, aimed at improving industry skills and service standards.

In addition to TV's own initiatives under the strategy, the audit examined how TV integrated and coordinated the many different government stakeholders that conduct tourism‑related activities.

The audit also examined how TV sought to identify weaknesses or gaps in the 2006 strategy and its implementation, to prevent their replication in the 2013 strategy.

Our examination included a detailed review of Cabinet and agency documentation. It also included multiple in-depth interviews with government and industry stakeholders, TV staff, including the chief executive officer, and the chair of TV's Board of Directors.

The audit was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of the audit was $435 000.

1.6 Structure of the report

In terms of structure, the report examines whether the department and TV:

- developed the 2006 strategy and were ready for its implementation—Part 2

- implemented the 2006 strategy as intended—Part 3

- reviewed and evaluated the 2006 strategy—Part 4.

2 Strategy development and readiness

At a glance

Background

Better practice guidance and previous audits emphasise the importance of being ready to implement and evaluate strategies once they are approved. The report uses the term 'the department' collectively for the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation and the former Department of Business and Innovation.

This Part examines:

- whether the 10 year Tourism and Events Industry Strategy (2006 strategy) was soundly based

- Tourism Victoria's (TV) readiness to implement and evaluate the 2006 strategy

- the lessons for developing Victoria's 2020 Tourism Strategy (2013 strategy) and whether TV applied these.

Conclusion

The 2006 strategy was well prepared by the department and was based on sound evidence and extensive consultation. However, the department and TV were not ready to implement and evaluate the strategy when it was launched in 2006.

The same approach has been applied for the 2013 strategy and this lack of preparation risks diminishing the effectiveness of the strategy.

Findings

- The department documented detailed plans for publishing the strategy and making essential organisational changes.

- However, government did not accept these plans and they were not applied.

- Instead, the detailed plans for actioning the strategy were developed well after its release.

Recommendation

That Tourism Victoria develops and documents plans that provide an effective platform for the whole-of-government implementation, evaluation and reporting of the 2013 strategy.

2.1 Introduction

This Part examines:

- whether the 10 year Tourism and Events Industry Strategy(2006 strategy) was soundly based, taking account of the evidence about what needed to be addressed and how best to do this

- Tourism Victoria's (TV) readiness to implement and evaluate the 2006 strategy

- the lessons for developing Victoria's 2020 Tourism Strategy (2013 strategy) and whether TV applied these.

The report uses the term 'the department' collectively for the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation and the former Department of Business and Innovation.

Better practice guidance and audits completed since 2006 emphasise the importance of being ready to implement and evaluate strategies once they are approved.

In terms of planning readiness, the joint Australian Government and Australian National Audit Office better practice guide, Implementation of Programme and Policy Initiatives: Making implementation matter, emphasised the benefits of:

- early, systematic and structured implementation planning to reduce 'the risk of delay to and dilution of, outcomes'

- early identification and assessment of the risks to successful implementation and the design and timely delivery of appropriate mitigations for significant risks.

In terms of evaluation readiness, VAGO's Reflections on audits 2006–2012: Lessons from the past, challenges for the future repeatedly found

- performance measurement lagging behind activity because agencies had not identified and measured suitable indicators early enough

- agencies not collecting sufficient baseline data to track performance across the range of intended outcomes.

2.2 Conclusion

The 2006 strategy was well prepared by the department and was based on sound evidence and extensive consultation. However, the department and TV were not ready to implement and evaluate the strategy when it was launched in 2006.

The department documented detailed plans in February 2006 for publishing the strategy and making the organisational changes seen as essential for its success.

Government's decision to take a different approach to that recommended by the department meant that TV required additional time to undertake organisational restructures, skill acquisition and stakeholder engagement to develop an implementation plan for the 2006 strategy.

The department and TV had not developed an adequate evaluation framework when the strategy was released and did not have detailed plans about how to do this.

The same approach has been applied for the 2013 strategy. This lack of preparation risks causing delays and diminishing the effectiveness of the strategy. VAGO's recommendation encourages TV to address these gaps for the 2013 strategy.

2.3 2006 strategy development and readiness

2.3.1 Approach to strategy preparation and planning

The department followed a three stage approach to developing and implementing the 2006 strategy:

- stage 1―develop a 10-year strategy with goals, objectives and high-level priorities and make the organisational changes needed to deliver on these goals

- stage 2―after publishing, develop three-year plans with more detailed actions and use these as the basis for funding bids to government

- stage 3―operationalise the three-year plans through annual business plans, which include the most detailed level of planning.

Staging in this way meant government could publish a strategy and signal its direction without delaying the release until it had made the organisational changes that were part of the strategy. However, not having detailed plans at its launch elevated the risks that agencies would not understand what they needed to do and the industry would be uncertain about how government would realise the strategy's goals.

The extensive delay in documenting a workforce development plan and the lack of measurable progress in infrastructure development show that these risks materialised.

2.3.2 Developing the strategy

The 2006 strategy's inclusion of priority areas was underpinned by sound research and extensive stakeholder consultation.

The 2006 strategy was based on a 2005 review—Victoria's Tourism and Events Industry Building a 10-year government Strategy. This document and the supporting records indicate that there was extensive research and wide consultation underpinning the 2006 strategy.

The review recommended actions to address challenges facing the industry such as:

- marketing Victoria effectively to withstand and overcome increasing competition, external shocks and perceived weaknesses in the national campaigns

- helping the industry to better compete for tourism spending by improving skills, focusing on significant and rapidly growing markets and by improving infrastructure and the attractiveness of destinations

- improving government's effectiveness by raising awareness across government about tourism's importance to the state, better coordinating its actions and making it easier for the industry to access and deal with government.

The review also highlighted the need for structural change within government to affect the achievement of tourism objectives and outcomes. It advised that 'current administrative structures do not allow for systematic and coordinated input by tourism and events stakeholders into broader Government policy and budget, as has been observed in the best practice example of New Zealand', which uses the Ministry of Tourism as a single, one-stop shop for coordinating government's actions.

The government accepted the review's finding that the 2006 strategy needed to be implemented in a way that effectively involved all government agencies with a role in delivering its intended outcomes.

2.3.3 Planning to effectively implement the strategy

Effective plans need to be clear about intended objectives and outcomes, define the tasks and the resources required to achieve these, identify clear roles and responsibilities, and describe how plans will be monitored and managed.

The department developed detailed plans to launch the 2006 strategy in June 2006 and made extensive structural changes to coincide with the launch. However, government's decision to take a different approach to that recommended by the department meant that TV required additional time to undertake organisational restructures, acquire additional skills and engage stakeholders to develop an implementation plan.

Readiness to implement the 2006 strategy

By the end of February 2006, the department had a detailed implementation plan describing the tasks, resources required and proposed timing for:

- finalising and launching the strategy by June 2006

- making organisational changes to create a Tourism and Events Cabinet Committee, a high-level advisory council and a separate Office of Tourism and Events Industry Development in time for the strategy's intended June launch

- updating agencies' strategic and business plans, one month after the strategy's launch and identifying and starting priority projects by the end of 2006—six months after the strategy's launch.

The structural changes flagged in these early plans went beyond those included in the final strategy. The strategy included a new advisory council and dedicated policy and strategy unit, but no longer included an expanded Tourism and Events Cabinet Committee nor a separate Office of Tourism and Events Industry Development, located in the department, with TV focusing exclusively on marketing.

TV has not provided evidence that these earlier implementation plans were revised and the revisions were applied before the strategy's release on 17 October 2006.

In late October 2006, a paper to the TV Board advised that the organisation's 2007–10 business plan would form the vehicle for implementing the 2006 strategy and would be developed in two stages:

- Firstly, identifying the actions required and the government stakeholders that would lead various aspects of the strategy in a draft plan by 30 November 2006.

- Secondly, consulting with stakeholders and the TV board, and conducting further research to finalise a 2007–10 business plan by 1 March 2007.

2.3.4 Preparing to evaluate the strategy

The goal of an effective evaluation framework is to determine how well actions within a strategy, program or project have achieved the intended objectives. This requires the assembly of relevant, reliable and sufficient evidence to attribute measurable changes in outcomes to these actions.

This is often challenging because outcomes can be difficult to measure and attributing changes to a strategy's actions may be complicated because of the influence of factors beyond government's control. Meeting these challenges requires a structured, timely and well-thought out approach to strategy evaluation.

The department had not developed an adequate evaluation framework by the time government launched the strategy and had not documented how it would address this.

Readiness to evaluate the 2006 strategy

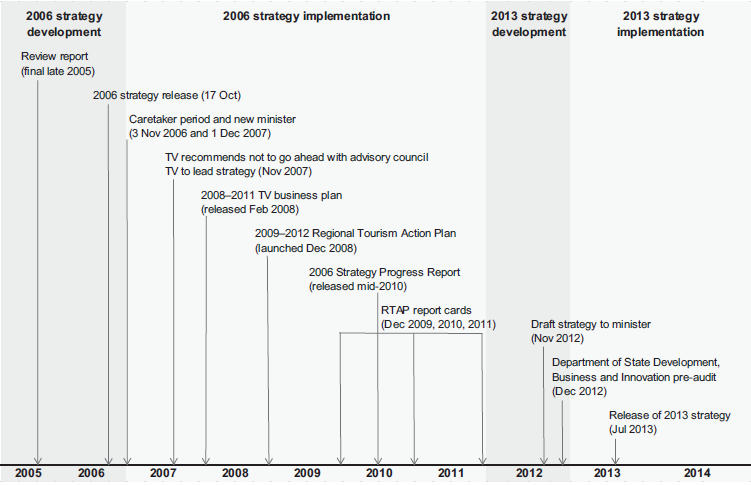

Figure 2A shows what an adequate evaluation framework should include.

Figure 2A

An adequate evaluation framework for the 2006 strategy

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

When the strategy was published the department had not prepared an evaluation framework with these characteristics. The department and TV have relied on estimates of tourism visitation, expenditure and tourism's contribution to the state's economy and employment as the key measures of overall success. These, on their own, do not provide an adequate basis for evaluating the strategy's effectiveness.

At the time the strategy was launched, the department and TV had not:

- explained how progress would be measured against the three high-level goals

- developed measures for each priority area to fully understand performance and help connect the strategy's actions to its objectives and high-level goals

- fully explained the relevance, appropriateness and limitations of using measures of expenditure and tourism's contribution to gross state product to measure the 2006 strategy's success.

The estimates of tourism gross state product and employment impacts are difficult to interpret as measures of the strategy's success because they are significantly influenced by factors beyond the control of government.

In addition, our review of these estimates shows that they potentially exaggerate the size and importance of Victoria's tourism industry, relative to other sectors, and that a primary cause of this is the approach used to measure tourism at international and national levels. VAGO describes this uncertainty in more detail in Part 4 on the strategy evaluation.

These indicators provide a partial snapshot of the strategy's likely impact. VAGO has not seen evidence that the department and TV had formed a well-structured plan detailing how they would address gaps in the evaluation framework.

Forming and implementing a plan to do this would have to be part of the early implementation after the strategy's release if it was to provide government with comprehensive, reliable and timely information on the strategy's performance.

2.4 Lessons for the 2013 strategy

2.4.1 Approach applied for the 2013 strategy

TV provided the draft 2013 strategy to government in November 2012. Its approaches to implementation and evaluation planning have followed a similar path to the one used for the 2006 strategy. It did not prepare detailed implementation and evaluation plans in advance of the strategy's release in July 2013. However, it is more advanced in terms of preparing mid-term plans with its 2011–2015 corporate plan in place and an updated Regional Tourism Strategy released in December 2013.

In response to the department's internal review—commissioned in preparation for this performance audit—TV stated its intention to complete these plans by June 2013. TV did not achieve this and it now expects to do this by November 2013. However, VAGO has not yet seen these documents.

2.4.2 Addressing the lessons from the 2006 strategy

The whole-of-government nature of this strategy means it is critical that TV quickly develops adequate implementation and evaluation plans. These should provide clarity about what government agencies need to do and describe how performance will be comprehensively measured, reported on and managed.

The ministerial briefing covering the draft 2013 strategy provided no information on these important, outstanding tasks or the risks of launching the strategy without a clear approach for addressing them.

Recommendation

- That Tourism Victoria develops and documents plans that provide an effective platform for the whole-of-government implementation, evaluation and reporting of Victoria's 2020 Tourism Strategy.

3 Strategy implementation

At a glance

Background

This part assesses Tourism Victoria's (TV) implementation of the 10 year Tourism and Events Industry Strategy (2006 strategy) by examining whether TV:

- developed comprehensive implementation plans following the 2006 strategy's release

- delivered the 2006 strategy's actions as intended.

Conclusion

TV adequately implemented actions where it was primarily responsible for priority areas, for example, brand marketing, encouraging more direct air access to Victoria and advocating for Victoria's tourism industry at local, state and national levels. However, it did not adopt a sufficiently comprehensive approach where it was required to coordinate and oversee integrated cross‑government activity. As a result, there is less detail and clarity about what action has been taken across agencies, and how effective those actions have been.

Findings

- TV made clear and concerted efforts to deliver on the 2006 strategy's objectives and priority actions.

- However, it faced a significant challenge in doing this for priority actions where successful implementation depended on significant inputs from other government agencies.

- TV has not thoroughly reviewed these issues and provided government with advice on how best to manage these identical implementation risks for Victoria's 2020 Tourism Strategy.

Recommendation

That Tourism Victoria completes a thorough review of the 2006 10 year Tourism and Events Industry Strategy's achievements and challenges, as well as the areas where it failed to deliver as expected so that it can advise government how to best manage these risks for Victoria's 2020 Tourism Strategy.

3.1 Introduction

Successfully implementing strategies that need cooperation between many government agencies represents a significant challenge. Doing this well requires:

- detailed plans describing tasks, time lines and agencies' roles and responsibilities

- arrangements for effectively engaging agencies and managing their contributions

- mechanisms for tracking, and responding to risks that threaten progress.

The Commonwealth guide Implementation of Programme and Policy Initiative: Making implementation matter emphasises the role of effective planning—'the likelihood of effective cross-agency implementation is greater when there is an overarching, high‑level implementation plan that is coordinated by a nominated lead agency and has clearly defined critical cross‑agency dependencies and responsibilities'.

This part assesses Tourism Victoria's (TV) implementation of the 10 year Tourism and Events Industry Strategy (2006 strategy) by examining whether TV:

- developed comprehensive implementation plans following the 2006 strategy's release

- delivered the 2006 strategy's actions as intended.

3.2 Conclusion

The implementation of the 2006 strategy was partly effective.

TV did not develop comprehensive implementation plans but adequately addressed priority actions within its established core business.

TV made clear and concerted efforts to deliver on the 2006 strategy's objectives and priority actions. However, the absence of plans that could clearly guide the actions of multiple agencies meant the implementation faltered in several priority areas where success depended on effective coordination across government.

TV faced a significant challenge where successful implementation depended on significant inputs from other government agencies.

TV has not thoroughly reviewed these issues and provided government with advice on how best to manage these same implementation risks for Victoria's 2020 Tourism Strategy (2013 strategy).

TV needs to develop implementation and evaluation plans that are fit for use in the context of a whole-of-government strategy, and it needs to advise government on the risks and how best to manage them.

3.3 Implementing the 2006 strategy

3.3.1 Developing detailed implementation plans

It took a lot longer than expected to finalise the plans that were the essential vehicles to implement the 2006 strategy. While most of this delay can be attributed to factors beyond TV's control, it slowed the 2006 strategy's progress and contributed to early confusion about how the 2006 strategy would be realised.

Once developed, TV's plans had clear gaps that significantly affected priority areas requiring coordinated action across government. These plans were not sufficiently clear and precise about roles, responsibilities, tasks and their timing to effectively guide and manage cross-government actions.

Delays in developing implementation plans

The release of TV's key medium-term plan for implementing the 2006 strategy―its three‑year business plan―was delayed by just under one year. The other critical planning instrument―the Regional Tourism Action Plan (RTAP)―was delayed for a similar period.

Less than two weeks after the launch of the 2006 strategy on 17 October 2006, TV's management informed its board of its plans to draft and finalise a three-year business plan. At this time TV still expected that government would appoint an advisory council to oversee the 2006 strategy. TV intended to draft a 2007–10 business plan by the end of November 2006 and finalise by 1 March 2007.

TV delivered a full first draft of this business plan by mid-November 2006. However, it was not finalised until December 2007 and subsequently published as the 2008–11 Business Plan in February 2008. This was 11 months late because of:

- the difficulty in getting government's sign-off due to the combined impacts of the election caretaker period in November 2006, the appointment of a new Minister for Tourism and Major Events in August 2007, and government taking more than a year to decide that it did not now need an advisory council to lead the 2006strategy

- the need to allow more time to reflect the issues raised at a 2007 regional transport summit.

TV intended to publish RTAP as a three-year plan for the period 2008–11. However, it was published in December 2008 as a plan covering the period 2009–12. Finalising the plan took more than two years after the 2006 strategy's launch because:

- TV only started developing the plan in the last quarter of 2007

- TV had completed a draft by March 2008 but it delayed consultation until after the tabling of Inquiry into Rural and Regional Tourism―completed by the Rural and Regional Committee of Parliament―which was scheduled for June 2008, but itself delayed till the end of July 2008.

An important factor in the delays VAGO has described was government's decision, just over a year into the 2006 strategy, to change the strategy's leadership and oversight arrangements. Figure 3A shows that TV still expected, in October 2007, that government would still appoint an advisory council and describes TV's subsequent recommendation in November 2007 that the minister should no longer do this.

Figure 3AChanging the 2006 strategy's leadership and oversight

The lack of visible leadership and an overarching plan

The internal 2006 strategy status report to TV's Chief Executive in October 2007 conveyed:

- the expectation that the advisory council would still be created, that the terms of reference and list of potential nominees had been provided to, but not yet approved by, the Minister for Tourism and Major Events and that this needed to be urgently progressed

- the urgent need to publish the 2007–10 plan to help avert the confusion in the industry about how the government would translate the 10-year strategy into action.

TV's recommendation not to proceed with appointing an advisory council

In November 2007, TV recommended that the minister not proceed with establishing the advisory council because of developments which meant it would duplicate the functions of other peak bodies including:

- the Victorian Events Industry Council, started by government in mid-2007 as a source of expert advice on developing a major events strategy

- the Victorian Tourism Industry Council which was growing and strengthening into a more effective industry leadership body with better links to government

- concerns that the advisory council would overlap with the activities of the TV Board, which provides specialist knowledge and leadership to the industry.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office summary from Tourism Victoria's internal memo and ministerial briefing note.

At the end of 2007, when the government decided not to form an advisory council, TV formally assumed the whole-of-government leadership of the 2006 strategy.

TV's arguments for this course of action are not convincing given that it did not have the authority, reach or governance structures to effectively support a whole‑of‑government implementation. TV's advice did not include an assessment of the risks of this course of action and how it would manage these.

Adequacy of the 2006 strategy's implementation plans

TV's annual business plans aligned with its three-year business plan and RTAP to form the most detailed component of the planning framework.

TV's plans adequately described the objectives, intended outcomes and high-level actions for each of the 14 priority areas included in the 2006 strategy. However, they did not include sufficient detail to guide actions that depended on the coordinated inputs of multiple government agencies.

Government agencies separate from TV will have their own internal business plans and VAGO did not review these within this audit. However, the 2006 strategy needed a detailed, whole-of-government implementation plan if TV, in its leadership role, was to effectively plan and manage its delivery. TV's plans did not meet this requirement.

The lack of detail is evident across all areas of the 2006 strategy but is most significant for areas heavily reliant on cross-government inputs, such as infrastructure development, skills and service standards, regional destination development, building synergies between tourism and education, promoting better decision-making and coordination.

In contrast, the New Zealand Government made the decision to have a formal reporting and coordination process including an implementation plan for its 2015 strategy that includes detailed actions, time lines and specific agency accountabilities.

Figure 3B describes how TV's plans fall short of what is required for effective whole‑of‑government implementation for infrastructure development.

Figure 3B

Planning for infrastructure development (priority area 4)

TV's 2008–11 business plan included five actions with broad timing, for example '2008–11', with two actions listing the involvement of other government agencies. For example:

- 'Using a destination management approach, work with key stakeholders such as the Department of Infrastructure and Department of Sustainability and Environment to facilitate Victorian Government infrastructure investments and policies that consider tourism needs and impacts'—timed for 2008.

TV's business plans between 2008–09 and 2010–11 succinctly describe between three and six priorities for each of these years. For example, in 2008–09 these included:

- providing advice on the infrastructure needed to support tourism in regional Victoria

- taking a greater role in influencing decisions on road and public transport infrastructure

- working with named agencies to implement the nature-based tourism strategy

- working with stakeholders to successfully scuttle the HMAS Canberra by mid-2009

- working with the former Department of Business and Innovation's Invest Assist Division to deliver priority infrastructure

- propose a dedicated tourism fund to support key tourism investment priorities.

These plans do not include sufficient detailed information on how these priorities will be completed, what each agency needs to do and how activities will be coordinated, managed and reported.

More detail, clarity and specificity were required to implement the 2006 strategy effectively across government.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Tourism Victoria business plans.

3.3.2 Adequacy of 2006 strategy implementation to 2011

TV's activities are clearly described in its reports to the board and we conclude that the implementation was only partly effective. There is evidence of more effective implementation for areas where TV was primarily responsible for delivering the actions.

From mid-2011, TV focused its planning and regular reporting on a smaller set of priority areas aligned to the new national tourism strategy.

Quarterly reports to the TV board show the breadth and range of TV's activities during this period. While the quarterly reports record activities for all priority actions, those activities within priority actions relying on the activities of other agencies were less extensive and convincing.

VAGO acknowledges TV's ability to quickly respond to a series of one off events that significantly affected the tourism industry during the 2006 strategy implementation such as floods and bushfires and the global financial crisis. These actions demonstrated TV's efforts to work closely with industry in responding to these events.

From this material and interviews with TV staff, VAGO concluded that the 2006 strategy implementation was partly effective because priority areas:

- within TV's core capabilities and responsibilities involving brand marketing, aviation access, online capability and policy advocacy, were well implemented

- where implementation depended on the actions of one or more agencies outside of TV, TV's implementation performance was less convincing:

- infrastructure development, improving skills and service standards, regional destination development and building synergies between tourism and education are priority areas where progress was slower than expected

- the lack of documentary evidence makes the extent of progress unclear for major and business events, investment attraction and the actions around better decision-making, coordination and communication.

Implementing actions involving Tourism Victoria's core capabilities

Project areas involving brand marketing and aviation access were well implemented by TV as seen in its quarterly reporting and in three case studies examined during the audit.

VAGO examined three projects implemented by TV as part of the 2006 strategy:

- the 2009–12 spa and wellness brand marketing campaign

- a project to increase the uptake of digital tools by regional tourism operators

- TV's tourism excellence grants program, aimed at improving industry skills and service standards.

These projects, costing approximately $9 million over three years, account for only a small amount of the total tourism funding of more than $100 million per year. However, they do provide an insight into how TV managed projects in its core areas of competency.

VAGO found that these projects had been well designed with clear objectives linking to the relevant priority area. They were also well implemented and monitored, with the projects' application adapted based on feedback received during roll out.

Implementing actions requiring cross-government support

VAGO was not assured about the implementation for several of these priority areas. These issues are described in Figure 3C.

In summary, while there is evidence about TV's activities in its reports to its board, they lack the same direction and clarity when compared to its actions in relation to its core capability areas. For several areas the outputs of these actions are not discernible.

Figure 3C

Implementation issues for cross-government priority areas

|

Priority area |

2006 strategy actions |

Implementation issues |

|---|---|---|

|

Infrastructure development |

All relevant agencies to take a ‘destination management’ approach to the planning of infrastructure to ensure the needs of the tourism and events industry are considered in the planning of major infrastructure projects. |

|

|

Skills and service standards |

Develop a Workforce Development Plan for the tourism industry to leverage initiatives announced in the Skills Statement to improve training opportunities for tourism employees and boost the skills of tourism business operators. |

|

|

Regional destination development |

TV convened in early 2007 a regional tourism summit to engage industry leaders, local government and other key stakeholders, and develop practical solutions to issues confronting the industry in regional Victoria. |

|

|

Investment attraction and facilitation |

The government will give a higher priority to public and private sector tourism investment across relevant agencies. In particular, TV will increase the priority given to tourism in our international investment attraction activities. |

|

|

Promoting better decision-making |

‘The 10 Year Tourism and Events Industry Strategy will…ensure that tourism and events agencies have good reporting mechanisms and operate as part of an effective strategic framework.’ |

TV’s evaluation of RTAP discusses issues of role clarity, particularly between regional tourism boards and departments. Further, TV has advised that the 2006 strategy did not have cross‑government reporting or formal agreements with other agencies during the implementation phase. |

|

Coordination and policy advocacy |

A tourism and events strategy and policy unit will provide the industry with a single access point into government on all non-marketing related tourism issues. |

TV advised that it ‘is not in a position to bring about formal whole-of-government coordination but can and does take action to improve coordination’. However, TV did document its considerable advocacy work. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Evidence of Tourism Victoria's coordination and advocacy activities

It was difficult to audit TV's activities to promote cross-government coordination because there were few documented records of these activities.

From TV's perspective this arose because the government had not agreed to a formal cross-government consultative process.

However, TV provided documentary evidence of its efforts to advocate on behalf of the tourism industry at local, state and national levels by working:

- throughout Victoria to provide information to tourism operators and to connect them with government agencies providing grants and training

- with other government departments to represent the interests of the tourism industry during policy development

- at the Commonwealth level by representing the state on cross-jurisdictional working groups.

Specific examples included TV's work to:

- coordinate and represent industry views between 2008 and 2010 in relation to the government's liquor licensing reforms. TV's involvement resulted in changes to proposed laws including:

- allowing 200 (instead of 100) patron thresholds for low-risk venues

- restaurants being exempted from late night opening charges

- allowing for the more flexible treatment of bed and breakfast establishments and regional wineries

- influencing the licensing arrangements for the Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre

- actively engage stakeholders across government since 2010, to reform planning and environmental controls to facilitate critical tourism investment

- represent the state in tourism matters at the Commonwealth level

- engage with other Victorian government bodies on an ongoing basis:

- achieving greater flexibility in the allocation of groundwater licences to help a new spa investment proposal

- working with the Transport Ticketing Authority in 2012 to develop and promote a myki visitor pack.

VAGO acknowledges this activity and TV's considerable efforts to work across government. However, it is not clear that TV is positioned to be fully effective in managing a whole-of-government strategy. TV should better document its plans and actions to improve cross-government coordination and its subsequent activities.

3.4 Lessons for the 2013 strategy

3.4.1 Approach applied for the 2013 strategy

TV is more advanced in preparing its medium term plans for the 2013 strategy than it was for the 2006 strategy. The 2013 strategy is also branded as a whole‑of‑government approach. This time, it is clear from the outset that TV will lead the implementation, although it is unclear how TV will address the absence of centralised monitoring and reporting of the activities of multiple government agencies.

TV intends to finalise implementation and evaluation plans much more quickly than it was able to for the 2006 strategy. However, it still has not done this four months after the 2013 strategy's launch. It is also unclear whether these plans will meet the minimum levels of clarity, rigour and detail needed for them to form the basis for the effective implementation and evaluation of this whole-of-government strategy.

It is a concern that VAGO did not find any strategy review examining the implementation and evaluation issues identified in this audit. The risks and challenges of a statutory authority embedded in a single department successfully implementing a whole-of-government strategy were not raised with government and should have been.

3.4.2 Addressing the lessons from the 2006 strategy

To do this TV needs to:

- document detailed implementation and evaluation plans that provide clarity about how the 2013 strategy will be implemented across government, and how TV will evaluate its progress and success

- complete a thorough review of the strengths and weaknesses of the 2006strategy and advise government of the risks to success for the 2013strategy and how best to mitigate these.

To date TV has not completed this type of review.

Recommendation

- That Tourism Victoria completes a thorough review of the 2006 10 year Tourism and Events Industry Strategy's achievements and challenges, as well as the areas where it failed to deliver as expected so that it can advise government how to best manage these risks for Victoria's 2020 Tourism Strategy.

4 Strategy evaluation and outcomes

At a glance

Background

This Part examines how well Tourism Victoria (TV) evaluated and reviewed the 10 year Tourism and Events Industry Strategy (2006 strategy) and considered a range of improvement opportunities for evaluation of Victoria's 2020 Tourism Strategy (2013 strategy).

Conclusion

TV did not effectively evaluate and comprehensively review the 2006 strategy and has therefore not consolidated and applied the lessons from its previous experience into the 2013 strategy.

Expenditure and visitation trends suggest Victoria has performed well compared to other states. However, uncertainties about the data and the lack of a comprehensive evaluation framework, means that this cannot be clearly attributed to the strategy.

Findings

- TV did not adequately evaluate the strategy's outcomes.

- TV has analysed useful information on expenditure and visitation but accepts that the survey it uses to do so has limitations. TV needs to better communicate the uncertainties embedded in these measures and better attribute changes to the strategy's actions.

- TV did not complete a thorough review of the 2006 strategy and needs to do this and to plan for regular and comprehensive reviews of the 2013 strategy.

Recommendations

That Tourism Victoria:

- develops a good understanding of the likely scale and nature of the expenditure currently captured in its estimates of economic activity that is unrelated to actions included in the 2006 strategy and the 2013 strategy

- fully explains the basis and limitations of the indicators it uses to describe tourism's contribution to the economy

- uses external expertise to review its evaluation framework and help it conduct and document a rigorous annual review of the 2013 strategy.

4.1 Introduction

This Part examines how well Tourism Victoria (TV) evaluated and reviewed the 10 year Tourism and Events Industry Strategy (2006 strategy) and draws out a range of improvement opportunities to evaluate Victoria's 2020 Tourism Strategy (2013 strategy). Section 2.3.4 of this report describes the goal and characteristics of an effective evaluation framework. In summary, to do this well a structured, timely and thoughtful approach is needed to assemble relevant, reliable and sufficient evidence to measure changes and conclude how much of these changes can be attributed to the strategy's actions.

This type of approach involves documenting an evaluation framework, collecting and analysing the data and underpinning performance indicators, and interpreting the trends to form an objective view on the strategy's impacts. Regular reviews should make use of this information to describe successes and identify and address performance weaknesses.

4.2 Conclusion

TV did not effectively evaluate and comprehensively review the 2006 strategy and has therefore not consolidated and applied the lessons from its previous experience into the 2013 strategy.

TV has analysed useful information on expenditure and visitation but accepts that the survey it uses to do so has limitations. TV needs to better communicate the uncertainties embedded in these measures and better attribute changes to the strategy's actions.

The data shows strong performance when compared to New South Wales (NSW) and Queensland. However, it is unclear to what extent this performance is attributable to the actions included in the 2006 strategy.

VAGO has not seen evidence of a radically different approach to evaluating and reviewing the 2013 strategy. This raises concerns due to the clear weaknesses in the approaches used for the 2006 strategy.

4.3 Tourism expenditure and visitation trends

Since 2006 the estimated expenditure of visitors and the number of visits have grown more quickly in Victoria than in NSW and Queensland.

These trends are encouraging because they suggest Victoria has had more success than these other major competitor states in attracting a greater proportion of visitors and expenditure. However, it remains unclear how much of this success can be attributed to the 2006 strategy because:

- current estimates also capture activities that are unrelated to the objectives and actions of the 2006 strategy and TV has not understood these impacts

- TV has not clearly shown how much of this change can reasonably be attributed to the strategy's actions.

In relation to attribution, expenditure and visits are significantly influenced by factors beyond the government's control. These include the income of potential visitors, exchange rates and prices in other markets and the cost and capacity of inbound and outbound air travel. The way TV evaluates and reports on expenditure and visitation changes does not explain how much of these changes can be attributed to the strategy's actions.

4.3.1 Tourism expenditure

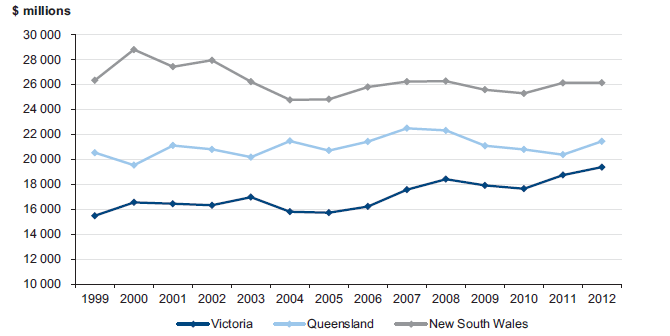

Figure 4A shows estimated tourism expenditure in Victoria, NSW and Queensland.

Figure 4A

Tourism expenditure by state 1999 to 2012 (adjusted for inflation)

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from Tourism Research Australia data provided by Tourism Victoria and adjusted to 2012 prices using Consumer Price Index for Australia.

Figure 4A shows that between 1999 and 2012, estimated tourism expenditure in Victoria remained constant until 2003, fell to 2005 and has risen rapidly since, with a two year interruption because of the global financial crisis.

Between 2006 and 2011, tourism expenditure, adjusted for inflation, has:

- grown by 16 per cent in Victoria

- remained static in NSW

- fallen by 5 per cent in Queensland.

For Victoria, this comprised strong growth of approximately 40 per cent for spending by international visitors, and about half this level of growth in domestic day trip expenditure. This contrasts with no growth in overnight visitors' expenditure.

4.3.2 Tourism visitation

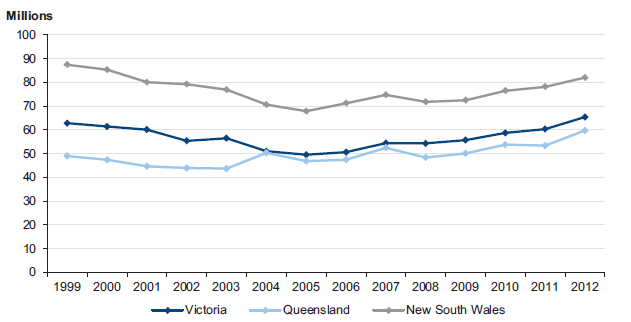

Figure 4B shows estimated tourism visits for Victoria, NSW and Queensland.

Figure 4B

Estimated number of visits 1999–2012

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from national and international visitor surveys.

Between1999–2012, the number of visits to Victoria and NSW declined up to 2005 but has risen since with both states regaining lost ground.

Over the period of the strategy between 2006 and 2011, visitor numbers grew by:

- 19 per cent for Victoria

- 10 per cent for NSW

- 13 per cent for Queensland.

For all three states, daytrips and international visitors grew strongly but overnight visitor growth was stable or declined slightly.

While the results are encouraging for Victoria, VAGO do not have sufficient evidence to attribute this performance to the 2006 strategy's actions.

4.4 Evaluating and reviewing the 2006 strategy

TV did not effectively evaluate and comprehensively review the 2006 strategy. The key performance indicators and data collected are not capable of measuring the performance of the government's high-level goals or the intended outcomes of the 2006 strategy.

4.4.1 Adequacy of the strategy evaluation

TV regularly reported to the board information showing progress towards achieving:

- a range of key economic, expenditure and visitation targets

- the outcomes associated with the strategy's 14 priority areas.

The key target information provided useful high-level indicators of the state of tourism in Victoria. However, the assumptions underpinning estimates of tourism's economic contribution and domestic visitor expenditure mean there is significant uncertainty about how well these measure the strategy's impact.

The remaining performance information did not fully explain performance against the strategy's goals, objectives and priority areas because TV had not:

- set appropriate performance indicators to measure progress towards the goals of Victoria becoming a leading regional destination, recognising the industry as a leading economic force and growing industry consistent with broader policy goals

- collected sufficient information to report on the outcomes for most of the strategy's 14 priority areas.

Uncertainty around tourism economic and expenditure estimates

The 2006 strategy and TV's key targets for assessing the strategy's success place a great deal of emphasis on changes in tourism expenditure and its contribution to the state's gross state product and employment.

VAGO's review found that this approach is likely to exaggerate the size of Victoria's tourism and events industry because:

- the way a 'visitor' is defined in estimating intrastate tourism and events expenditure, which is consistent with the national and international standard, is likely to include significant expenditure that is unrelated to the industry

- it uncertain how much of the tourism and events expenditure attributed to intrastate visitors is truly incremental to the Victorian economy―i.e. if the tourism industry did not exist, Victorians are likely to redirect their expenditure to other parts of the Victorian economy

- the estimates of indirect expenditure were derived using an input-output model—this overestimates the impacts because this approach does not take into account that the competing demands for resources will constrain the impact of increased tourism expenditure in generating indirect activity. So the methodologically more reliable way to do this type of modelling is to use a Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model, which does take account of these constraints.

The potential to significantly overestimate tourism's economic contribution has been previously recognised by the Productivity Commission, as described in Figure 4C.

Figure 4C

Productivity Commission findings on estimates of tourism's economic impacts

The commission's report showed that while applying the approach widely used to estimate tourism's economic impact 'can provide a useful basis for understanding the economic 'footprint' of visitor-related activity and its linkages with upstream industries, the approach adopted results in the inclusion of many items as tourism output that are far removed from tourism as it is commonly understood'. For example:

- if a resident of a country town travels more than 25 kilometres 'to a regional centre to purchase a motorcar, the trip is counted as tourism and, if the vehicle is Australian-made, its manufacture is counted in the output of the Australian tourism industry'

- many foreign students studying in Australia living there for less than one year are classed as tourists under the World Tourism Organisation definition, and all of their local expenditure—including their transport, accommodation, day-to-day living expenses and course fees—is counted as tourist expenditure and converted into tourism industry output

- 'when sales representatives on country business trips refuel their cars, the value of the petrol is recorded as tourism output and, in effect, the oil refinery workers, the tanker drivers and the service station attendants are deemed to have been working partly in the tourism industry'.