Board Performance

Overview

Boards are the governing bodies of public sector entities. They set the overall strategic direction for the entity, and monitor and manage the performance of senior management.

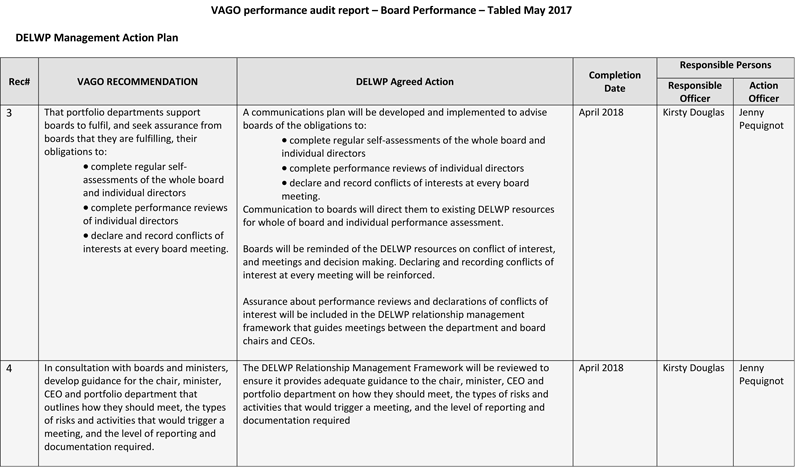

In Victoria, around 3 400 public sector entities are governed by boards with, in total, about 33 000 board members—known as directors. These boards vary significantly in type and role. Most directors are from outside the public service and 85 per cent of them are unpaid.

In this audit, we examined whether boards are performing effectively and contributing to effective governance of public sector entities.

We make four recommendations directed to portfolio departments, the Department of Premier and Cabinet and the Victorian Public Sector Commission.

Board Performance: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER May 2017

PP No 246, Session 2014-2017

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Board Performance.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

11 May 2017

Audit overview

Boards are the governing bodies of public sector entities. Board members set the overall strategic direction for the entity, and monitor and manage the performance of senior management. They also oversee operations and regulatory compliance, and have an important role in keeping responsible ministers and government departments aware of the major risks that their entities face. Effective boards set policies to mitigate these risks and promote transparent, accountable governance.

In Victoria, around 3 400 public sector entities are governed by boards with, in total, about 33 000 board members—known as directors. These boards vary significantly in type and role, and include commercial boards of governance, advisory and regulatory bodies, registration boards, management boards, inquiries, task forces and ad hoc expert panels. Most directors are from outside the public service and 85 per cent of them are unpaid.

Boards of public sector entities operate under many laws, including the Corporations Act 2001, Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA), Public Administration Act 2004 (PAA) and State Owned Enterprises Act 1992. Most boards are also required to meet responsibilities set out in the specific legislation that establishes them and associated subordinate legislation.

A number of public sector agencies are involved in appointing directors and providing support to boards and their entities:

- Portfolio departments—work with public sector entities and provide guidance on matters relating to public administration and governance

- Victorian Public Sector Commission(VPSC)—issues binding codes of conduct for boards and board directors, and provides leadership and guidance to help boards achieve high standards of governance

- Department of Premier and Cabinet(DPC)—reviews portfolio departments' submissions to Cabinet for appointing board directors and provides assurance that appointments meet the government's Appointment and Remuneration Guidelines (the Guidelines).

Poorly functioning boards can lead to mismanaged conflicts of interest, insufficient oversight of significant government projects and loss of public trust.

In this audit, we examined whether boards are performing effectively and contributing to effective governance of public sector entities. We assessed the guidance and support that VPSC and portfolio departments give to the boards of public sector entities. We also surveyed 212 public sector entities to better understand their governance practices and to obtain feedback on the effectiveness of the guidance their boards receive. Finally, we examined the governance practices of the boards at four public sector entities in detail, to develop case studies on how boards function within entities of different sizes, with varying responsibilities and operating environments.

Conclusion

The significant majority of public sector boards we examined demonstrated better practice in most areas of governance and are operating effectively.

However, at some boards, a significant probity gap remains relating to directors' routine declaration of conflicts of interest at board meetings.

Remuneration and board composition are also of concern in some cases, particularly for regional boards, which sometimes struggle to make sure that board directors collectively have the necessary skills, knowledge and experience to effectively fulfil their roles.

Both VPSC and the portfolio departments provide good guidance on governance to their boards, but responsible portfolio departments could do more to support boards and to oversee their performance.

Findings

Guidance and oversight

Given the important roles board directors perform on behalf of the public sector, it is important that they receive direction on how to perform their functions. VPSC and DPC provide strong whole-of-government guidance and support for board directors.

Although portfolio departments are not required to provide boards with training or additional guidelines, some departments managed the risk of knowledge gaps by providing additional guidance:

- Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS)—provides hospital boards with specific information on clinical governance

- Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP)—provides advice on its stakeholders and the regulatory environment

- Department of Education and Training (DET)—provides board directors with training in general director obligations and specific information on the operating and regulatory environment of the vocational education and training (VET) system and the technical and further education (TAFE) sector

- Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources(DEDJTR)—has finalised a governance framework that includes guidance for entities and boards on their obligations, and will provide regular status updates on boards and entities to the relevant minister.

VPSC's guidance and training

VPSC provides good-quality guidance to prepare board directors for the governance practices required under the PAA. This guidance promotes better practice and includes board roles and responsibilities, a directors' code of conduct, and factors to consider when recruiting board directors. Over half of surveyed board chairs rated VPSC guidance as 'very useful' or 'extremely useful'. VPSC could, however, enhance this guidance by including more examples of how to conduct board assessments.

The Government Appointments and Public Entities Database (GAPED)—the database that records details about boards and board directors—has recently been updated so that reliable data on gender is available. VPSC provides user guides to departments to help them enter appointment data. An increase in the number of mandatory data fields has reduced the risk of incomplete information, and the new interface is more user friendly. In contrast, GAPED data from 2015–16 was incomplete and out of date.

DPC's oversight of board appointments

DPC has effective processes in place to ensure that appointments of board directors meet the requirements set down in the Guidelines. DPC reviews all submissions from portfolio departments that require Cabinet approval under the Guidelines, such as board directors appointed by the Governor‑in‑Council or a minister. DPC uses checklists to assure Cabinet that portfolio departments have addressed requirements such as remuneration limits, probity checks, required skills and gender ratios.

However, the way DPC classifies the entities is confusing. Boards and portfolio departments expressed concern that the classifications do not sufficiently recognise the level of risk and complexity that their boards negotiate. These classifications are important as they are the mechanism for setting remuneration thresholds for board directors.

Boards reported that incorrect classifications affect their ability to attract the appropriate calibre of board directors, as some board directors feel the remuneration is inadequate for the level of risk and work they are undertaking. Inappropriate classification can also result in overpayment.

Portfolio departments' support for boards

The level of support that portfolio departments provided to boards varied in both quality and specificity. Larger portfolio departments with multiple boards or boards of similar types have guidance that aligns with better practice and assists boards with their sector-specific duties.

We identified some good examples:

- DET's support for TAFE institute boards

- DHHS's support for health service boards

- DELWP's support for catchment management authorities and water corporation boards.

In our survey of 212 public sector entities, 71 per cent of board chairs and 67 per cent of chief executive officers (CEO) of entities said that guidance and support from their portfolio departments was 'very useful' or 'extremely useful'. Departments that tailored training or guidance to the sector or entity needs rated highest.

Portfolio departments' oversight of boards

Under the PAA, portfolio departments are responsible for providing entities with guidance on public administration and governance. They must also advise the responsible minister on how the entity is discharging its responsibilities.

Some portfolio departments told us that they rely largely on their relationship with the board chairs and CEOs of the entities in their portfolios to learn of any governance issues. This approach does not consistently enable departments to identify and address governance issues at an early stage. Portfolio departments' oversight and monitoring tends to be reactive and driven by crises or issues, rather than being proactive and holistic.

DELWP and the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources (DEDJTR) provided evidence of work that intends to provide more structure to reporting and communications by entities with their departments.

Portfolio departments need to develop relationship frameworks that guide how frequently and for what purpose the board should meet with the responsible department and minister.

To gain assurance that boards are complying with their obligations under the PAA, portfolio departments that have not already done so should also define a set of reporting requirements that boards need to complete. This should include attesting that conflicts of interest are managed and that performance assessments are completed.

Board governance and practices

The board is responsible for setting the entity's strategic direction, monitoring operations and compliance, and reporting on performance. Boards should promote transparent, accountable governance. We found that, although boards play a key role in developing strategic documents, they could improve their compliance with governance requirements.

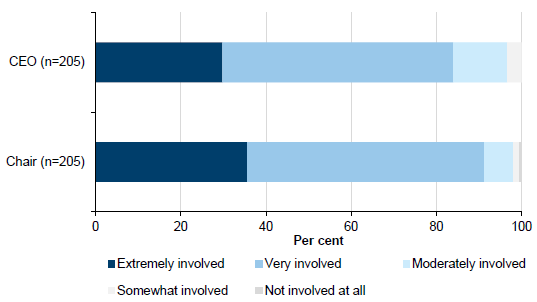

Public sector boards report they are sufficiently involved in the strategic planning and oversight of their entities. The four boards we examined in detail played key roles in developing their entities' strategic plans. In the wider survey, 91 per cent of chairs and 84 per cent of CEOs responded that they believe their board is 'very involved' or 'extremely involved' in strategic planning.

Most boards we surveyed reported that they regularly assess their own performance (80 per cent). However, our examination of these boards' assessments found that only 69 per cent demonstrated that sufficient assessments had been carried out. As this is a requirement under the PAA, boards need to complete this routinely. The four boards we looked at in detail regularly review the performance of the board as a whole, and the CEO, but the majority do not review the performance of individual board directors. These boards advised that they would benefit from further guidance on how to complete these assessments.

The four boards we examined in detail have adequate accountability structures and effective mechanisms for carrying out their governance roles. They all had clear documentation outlining their roles and responsibilities. They record effective minutes from board meetings and have procedures in place to identify potential conflicts of interest. They all disclosed or declared financial interests, had valid risk registers and completed CEO and board assessments. Three of the four had skills matrices for board directors.

However, our wider survey results did not reflect these findings. In our survey, 78 per cent of boards responded that they disclose or declare financial and non‑financial interests. In contrast, the four boards we examined all declare interests at every meeting and completed more thorough disclosures annually. All boards should follow this approach to make sure their dealings are transparent and accountable.

Only 83 per cent of surveyed entities provided evidence of a valid risk register to identify and manage risks. The selected four boards had more comprehensive risk registers and review mechanisms in place. Again, this is a fundamental element of good governance that needs to be embedded in boards and entities of any size, complexity or turnover.

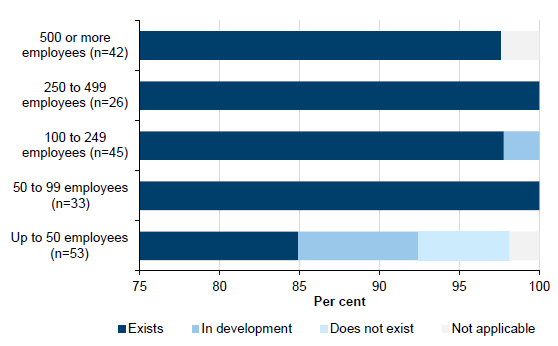

Our survey showed that 52 per cent of entities do not have a current skills matrix for board directors. Three of the boards we examined in detail maintained a skills matrix. Although a skills matrix is best practice rather than a legislated requirement, boards without one cannot easily demonstrate that their board directors have the required or optimum mix of skills to effectively carry out their duties and fulfil their responsibilities. Public sector entities found some skill sets difficult to source, particularly in regional settings. These include financial skills, legal knowledge, sector experience and clinical governance skills.

Recommendations

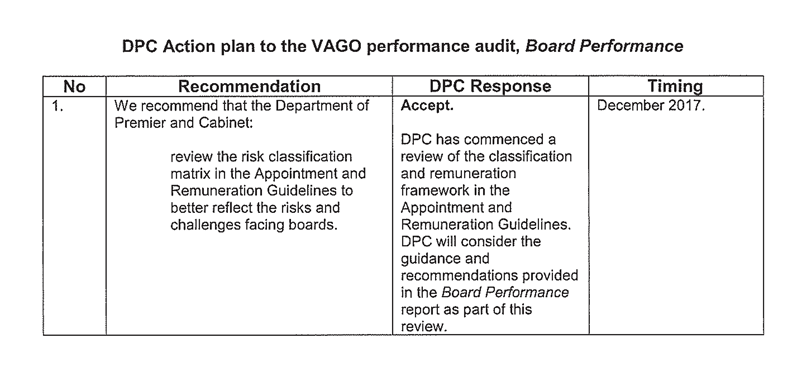

We recommend that the Department of Premier and Cabinet:

- review the risk classification matrix in the Appointment and Remuneration Guidelines to better reflect the risks and challenges facing boards (see Section 2.4).

We recommend that the Victorian Public Sector Commission:

- develop guidance for boards on the activities they should examine in their independent assessments (see Section 2.3).

We recommend that portfolio departments:

- support boards to fulfil, and seek assurance from boards that they are fulfilling, their obligations to:

- complete regular performance reviews of the whole board and individual directors (see Sections 2.2.2 and 3.5)

- declare and record conflicts of interests at every board meeting (see Section 3.2.1).

- in consultation with boards and ministers, develop guidance for the chair, minister, CEO and portfolio department that outlines how often they should meet, the types of risks and activities that would trigger a meeting, and the level of reporting and documentation required (see Section 2.2.2).

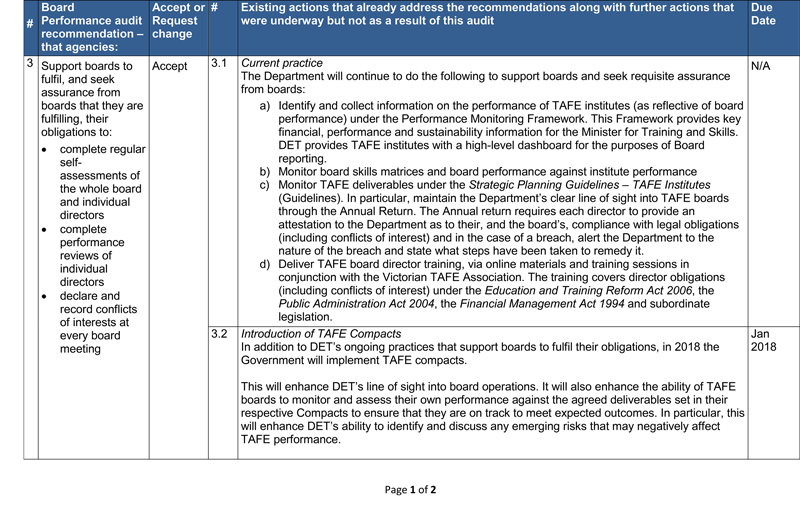

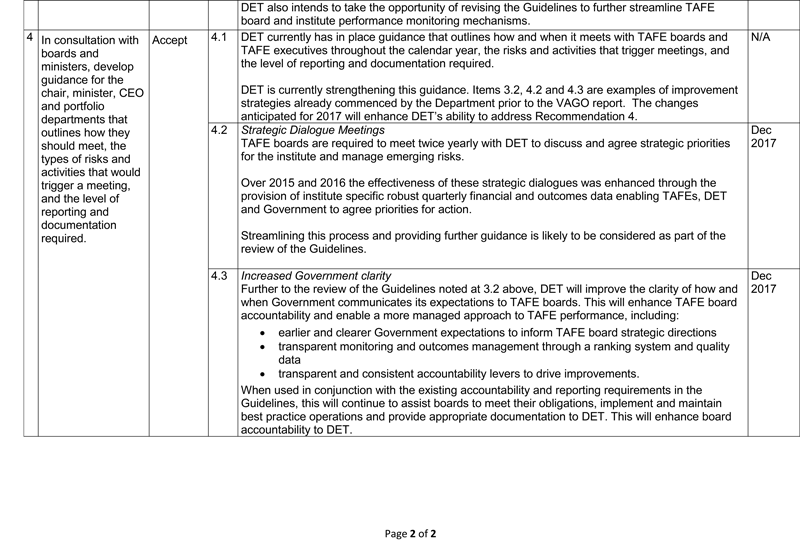

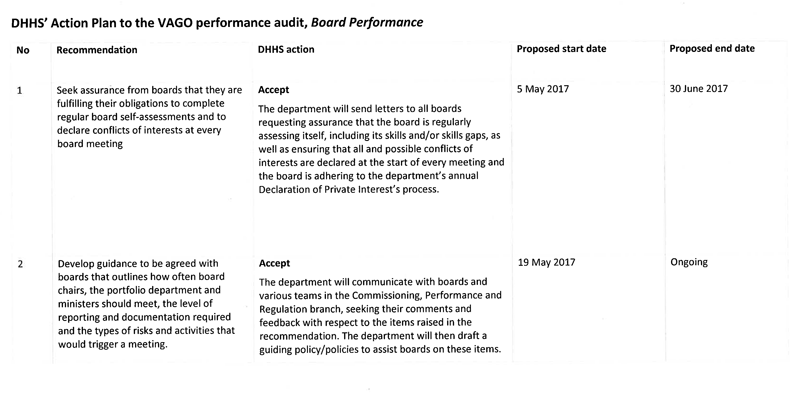

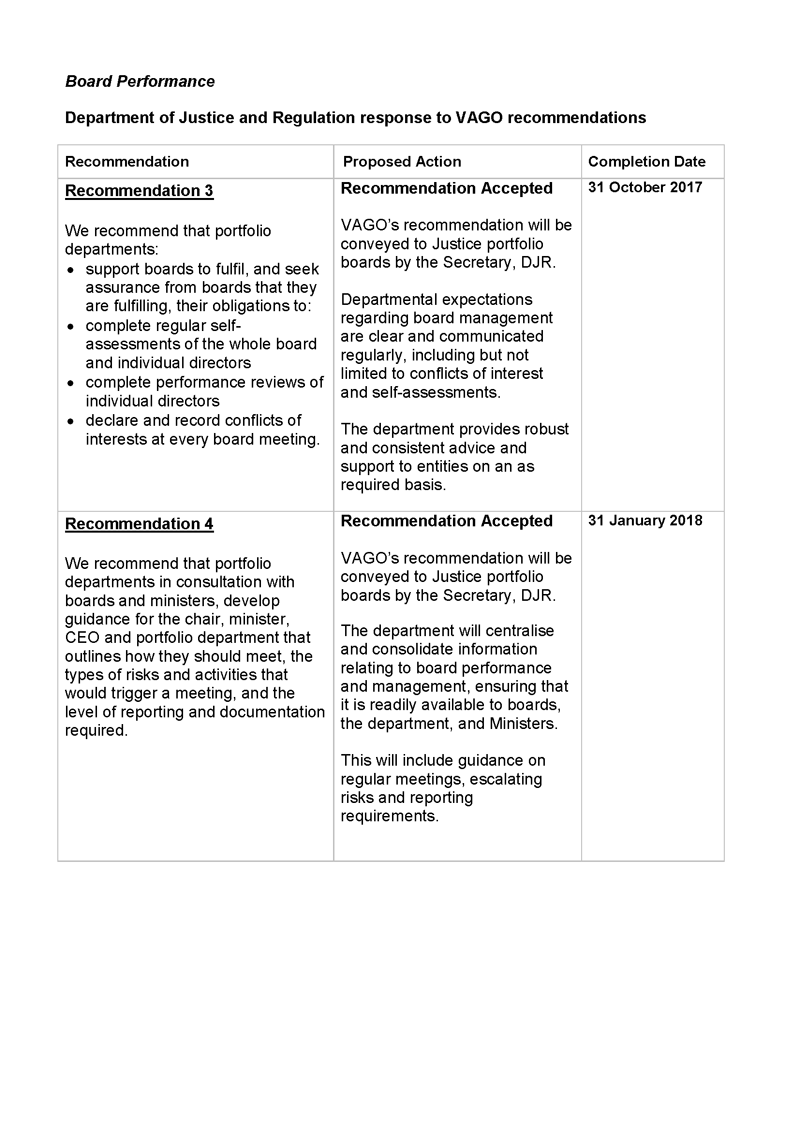

Responses to recommendations

We have consulted with portfolio departments, the boards in the case studies (from Box Hill Institute and Centre for Adult Education, CenITex, Fed Square Pty Ltd and Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute), the Department of Premier and Cabinet and the Victorian Public Sector Commission, and we considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions. As required by section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report to those entities and asked for their submissions or comments. We also considered the views of the 212 public sector entities in our survey.

The following is a summary of those responses. The full responses are included in Appendix A.

All portfolio departments, the Department of Premier and Cabinet, the Victorian Public Sector Commission and the Box Hill Institute responded. All departments and the Victorian Public Sector Commission accepted the recommendations. A number of departments referred to existing work that fulfils the report's expectations for governance and oversight, and all departments committed to concrete actions to fulfil the recommendations.

1 Audit context

The Victorian public sector is made up of the Victorian public service (departments, offices and other designated bodies), and special bodies and public entities such as statutory authorities, state-owned corporations and advisory bodies that exercise a public function.

Public entities are generally legally distinct and established for a specific purpose. They have defined functions and operate with varying degrees of autonomy. Public entities are ultimately accountable to a minister for their performance.

Most public entities are headed by a governing body—usually a board. In some entities, the governing body may be referred to as a committee or council. Boards are made up of individual board directors. Their responsibilities are outlined in the Public Administration Act 2004 (PAA) and the entity's establishing legislation (such as the Health Services Act 1988 for public health service boards),and reflected in the policies of the government of the day. Boards are essentially responsible for ensuring the effective performance of their entity.

According to the December 2016 report State of Victorian Public Sector 2015–16, there were 33 025 board members on 3 351 public sector boards. The largest numbers of boards (93.2 per cent of all boards) are for:

- school councils—1531

- committees of management over Crown land—985

- cemetery trusts—449

- public health services and other health bodies—127.

Most board members are unpaid (85 per cent).

1.1 Types of boards

In Victoria, public entities are classified into one of four groups—A, B, C or D. The classification of an entity determines the level of remuneration for board directors and the approval process required for appointments.

The Department of Premier and Cabinet's (DPC) Appointment and Remuneration Guidelines (the Guidelines) detail these classifications.

Group A boards

Group A consists of commercial boards of governance or boards of entities of state significance, as determined by the Premier of Victoria. Group A boards are:

- government business enterprises, including statutory authorities, state bodies and state business corporations established under Victoria's State Owned Enterprises Act 1992

- commercial bodies established under the Commonwealth Corporations Act 2001 or specific legislation, and other statutory authorities that are strictly commercial in nature.

Group B boards

Group B includes significant industry advisory bodies, other key advisory bodies, regulatory bodies and significant boards of management. Specifically, these are:

- industry advisory boards and other bodies that advise government on key strategic matters and matters of statewide significance

- quasi‐judicial bodies or tribunals where there is no other framework governing the appointment and remuneration of board members

- government entities that undertake significant statutory functions, develop policies, strategies and guidelines in a broad and important area of operation, or provide specialist advice to a minister

- management boards of medium‐sized entities that undertake one or more functions or provide a strategically important service.

Group C boards

Group C includes advisory committees, registration boards and management boards of small entities. These are:

- scientific, technical and legal advisory bodies

- disciplinary boards and boards of appeal

- qualifications, regulatory and licensing bodies

- management boards and committees of small entities undertaking a specific function or providing a discrete service

- ministerial and departmental advisory boards and consultative committees on issues confined to a portfolio or local concerns.

Group D boards

Group D consists of inquiries, task forces and ad hoc expert panels. These are:

- boards of inquiry established under the Victorian Inquiries Act 2014, which are required to submit a comprehensive report within a specified time frame

- ad hoc expert panels established for limited time periods to undertake a specific, often technical, task.

1.2 Relevant legislation

Public entity boards are subject to primary and subordinate laws that affect how they perform their functions. Core legislation sets the governance framework for public entities.

Public Administration Act 2004

The PAA provides a framework for good governance in the Victorian public sector and in public administration generally in Victoria. It specifies the minimum requirements that public entity boards and directors must abide by. These requirements include duties of the directors and chair, probity, management of meetings, financial and risk management, and performance assessments.

Financial Management Act 1994

The Financial Management Act 1994 establishes the Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance (Standing Directions). The Standing Directions set out financial management standards for government agencies, including public sector boards.

In 2016 the Standing Directions were updated and now place more responsibility on portfolio departments having oversight of agencies within their portfolio.

Other relevant legislation

Other relevant legislation includes:

- Corporations Act 2001—which regulates matters such as the formation and operation of companies and duties of officers

- State Owned Enterprises Act 2001—which provides the operational and regulatory framework for state-owned enterprises, including state business corporations, state-owned companies and state bodies.

Most boards are also required to meet responsibilities set out in the specific legislation that establishes them and associated subordinate legislation.

1.3 Roles and responsibilities

1.3.1 Boards

Boards set the overall strategic direction of public entities and oversee the chief executive officer (CEO) or equivalent in carrying out that strategic direction. Boards also ensure that public entities meet their statutory obligations, and that operations and policies reflect the values and employment principles of the public sector. This includes complying with the Victorian Public Sector Commission's (VPSC) Code of Conduct for Directors of Victorian Public Entities.

Section 81 of the PAA defines boards' obligations to inform their responsible minister and the head of the portfolio department of major risks the public entity faces and the measures in place to address those risks. This section of the PAA also specifies the procedures and legal requirements that must be in place for:

- managing conflicts of interest, including directors providing or receiving gifts, benefits or hospitality

- the board to assess its own performance as well as that of individual directors

- dealing with any poor performance by directors

- managing any existing or potential conflicts of interest

- resolving any disputes between directors

- governing the conduct of its meetings and keeping compliant records.

1.3.2 Portfolio departments

Under the PAA, portfolio departments are responsible for:

- advising the responsible minister on matters relating to public entities, including how entities discharge their responsibilities

- working with public entities and providing them with guidance on public administration and governance.

Departments can also ask public entities to provide them with any information required to help the department understand whether the entity is discharging its responsibilities.

The updated Standing Directions also require departments to oversee entities by providing information to the responsible minister on financial management, performance and sustainability.

Most departments cannot direct or control a public entity in the performance of its functions. Exceptions include the Department of Health and Human Services, which has powers under the Health Services Act 1988 to direct the operations of health services.

Although departments may not be directing entities' operations, they have strong influence over boards by:

- advising the responsible minister on the appointment of board directors

- advising public entity boards that they must comply with government policy when recruiting board-appointed directors

- coordinating budget submissions within the portfolio and funding approval for new projects

- formulating statements of expectations that apply to boards.

1.3.3 Victorian Public Sector Commission

Under the PAA, VPSC issues binding codes of conduct for boards and board directors. VPSC is also expected to provide leadership and guidance to help boards achieve high standards of governance.

VPSC manages the Government Appointments and Public Entities Database, which contains data on Victorian public entities' governance arrangements, compliance requirements and diversity. Using this data, VPSC produces the annual report State of the Public Sector in Victoria, which details the composition and profile of public sector boards and directors.

1.3.4 Department of Premier and Cabinet

As part of the process for appointing board directors, DPC reviews submissions from portfolio departments on all board director appointments that require Cabinet approval under the Guidelines. DPC advises the Premier on whether these board appointments meet the Guidelines, which cover recruitment, appointment and remuneration processes for public sector entity boards.

A 2015 Premier's Circular on good board governance states that board appointments should be merit based, fair, open and diverse. It recommends that recruitment be structured so that appointments are publicly advertised, informed by a skills matrix and broadly mirror the diversity of the community.

1.4 Ombudsman review of board governance

In 2013, the Victorian Ombudsman released its report of an 'own-motion' investigation into Victorian public sector boards. This investigation followed serious findings in a number of the Ombudsman's reports concerning:

- inadequate processes for appointing board directors

- conflicts of interest

- inadequate performance reviews of boards and board directors

- poor oversight by boards of entities' operations.

The investigation focused on board governance frameworks and how they were applied in practice. It also examined whether there were systemic issues that created risks for boards in performing good governance.

The Ombudsman found that the use of boards was appropriate in a range of circumstances but that there were risks including:

- complex structures and governance arrangements in entities

- varied understanding of what constitutes appropriate autonomy from government—such as the degree to which boards are subject to ministerial direction and the role of departmental secretaries in board governance

- poor data on the number of boards and their cost

- lack of departmental record keeping on board entities and their composition, function, appointments, ministerial powers and reporting requirements

- lack of clarity of internal and external accountability and the relationship between the board and the CEO, including how these roles are defined and separated

- entities not being subject to strategic or performance reviews

- entities not sufficiently ensuring that candidates offer the best mix of skills during board appointment processes

- entities not properly considering the appropriate size of the board.

The Ombudsman's recommendations included that:

- ministers, board directors and departments pay greater attention to the legislative framework when they interpret the functions and accountability of boards, rather than using secondary sources

- the Premier of Victoria consider prioritising the development of a digital recruitment system for board appointments in the Victorian public sector

- departments undertake performance and governance reviews of existing public entities, individually or as classes, over the next five years to determine whether they are still fit for purpose and cost effective and whether their functions are still necessary.

1.5 Why this audit is important

Public entities managed by boards make up a significant portion of the Victorian public sector. They employ about 86 per cent of the public sector workforce—approximately 245 616 full-time-equivalent employees. They also manage and deliver critical public services such as:

- cultural and sporting facilities

- drinking water and sewage disposal

- emergency response

- hospitals

- management of Crown land reserves and cemeteries

- schools and technical and further education (TAFE) institutes.

If boards are functioning poorly, they may not adequately oversee the effective and efficient delivery of these services. Poor board performance can also lead to mismanagement of conflicts of interest, insufficient oversight of significant government projects, and loss of public trust.

Recent VAGO audits and other investigations—such as the 2013 Victorian Ombudsman report discussed in Section 1.4—have found examples of inadequate governance practices among some public sector entity boards. Our December 2014 review of audit reports tabled between July 2013 and October 2014 highlighted that governance-related matters accounted for the highest number of findings during this period.

1.6 What this audit examined and how

The objective of this audit was to determine whether public sector boards are performing effectively and contributing to effective governance of their entities.

We assessed whether VPSC and portfolio departments:

- provide sufficient and useful guidance and support to assist public sector entity boards to effectively perform their governance functions

- effectively monitor the performance of public sector entity boards.

We reviewed the oversight and guidance provided by VPSC and all portfolio departments:

- Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources

- Department of Education and Training

- Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning

- Department of Health and Human Services

- Department of Justice and Regulation

- Department of Premier and Cabinet

- Department of Treasury and Finance.

We also assessed whether public sector entity boards demonstrate effective governance practices.

This report draws on legislative requirements and board governance principles from the PAA, VPSC guidance, Premier's Circulars, the Governance Institute of Australia, Western Australia's Public Service Commission, the Australian Institute of Company Directors and the Australian National Audit Office to assess board effectiveness. Appendix B features a table of legislative and best-practice principles for board governance. These principles inform how we measured effectiveness.

To enable a well-targeted audit, we excluded the following categories of boards from the audit:

- boards with quasi-judicial functions or which are solely an advisory group or panel, with no governance function

- boards established on an ad hoc or short-term basis, such as for inquiries and task forces

- Class B cemetery trusts, because the majority are small and volunteer-based, have minimal financial risk and materiality, and are not required to report under the Financial Management Act 1994

- committees of management for Crown land, which we audited in our 2014 report Oversight and Accountability of Committees of Management

- school councils, because we are scheduled to audit school councils in a forthcoming performance audit.

Within the remaining group of boards, we invited the board chair and CEO of 212 public sector entities to complete an online survey. We had at least one response from all entities, and we received responses from both the chair and the CEO for 201 entities (95 per cent).

Finally, to conduct a deeper examination of governance practices, we looked in detail at the following four boards as case studies:

- Box Hill Institute and Centre for Adult Education

- CenITex

- Fed Square Pty Ltd

- Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute.

We selected these boards as they represent agencies of various sizes, are scheduled as public entities under the PAA, have different types and levels of responsibility, and are subject to different legislative requirements.

We conducted this audit in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. The cost of this audit was $725 000.

1.7 Report structure

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines the guidance provided to, and oversight of, boards by portfolio departments, VPSC and DPC

- Part 3 examines the governance practices of boards.

2 Guidance and oversight

Under the Public Administration Act 2004 (PAA), portfolio departments and the Victorian Public Sector Commission (VPSC) support public entities and boards to fulfil their functions effectively.

In this Part of the report, we assess the guidance and support all public boards receive from their portfolio departments and from the VPSC.

The Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) administers the Appointment and Remuneration Guidelines (the Guidelines) for public sector boards. We assessed the Guidelines and how DPC administers them.

2.1 Conclusion

Overall, Victoria's framework provides sufficient support and guidance for boards of public entities. VPSC's guidance is useful and is based on best practice principles, and DPC's administration of board appointments is sound.

Portfolio departments provide valuable support to boards but it is often ad hoc. Despite having a duty to advise the responsible minister on whether an entity is discharging its duties effectively, some portfolio departments do not gather enough information from boards to fulfil this obligation.

Four portfolio departments are beginning to provide more structure to reporting and communicating with boards. All portfolio departments should provide similar guidance to boards to improve oversight.

2.2 Guidance and oversight from portfolio departments

Given the important roles that boards perform on behalf of the public sector, it is essential that board directors receive effective direction on how to perform their functions. The government must also collect enough information to allow responsible ministers to oversee boards' performance.

We found that some portfolio departments' oversight and monitoring of board performance is generally reactive and driven by crises or issues, rather than being proactive and holistic.

The Department of Education and Training (DET), the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) provided comprehensive training or guidance to new board directors, and the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources's (DEDJTR) governance framework allows them to regularly monitor the 'health' of entities and boards.

2.2.1 Guidance on the role of board

Portfolio departments have a support and oversight role for public entities under section 13A of the PAA. This role includes:

- advising the responsible minister on matters relating to the public entity, including how the public entity discharges its responsibilities

- working with public entities and providing guidance on matters relating to public administration and governance.

The Premier's Circular No. 2015/02 Good Board Governance specifies that new board directors receive an induction, a VPSC 'Welcome to the board' pack, applicable codes of conduct, conflict-of-interest policies and other information to help them understand the board's position and its relationship to the entity, the department and the minister. The results of the survey we conducted of 212 public sector entities show that 95 per cent of public entities provide inductions to new board directors.

Three of the seven portfolio departments we assessed provided separate training or guidance for boards. A fourth department—DEDJTR—has finalised a governance framework that includes guidance for entities and boards on their obligations, and will provide regular status updates on boards and entities to the relevant minister. Providing guidance and an induction tailored to the entity, regulatory environment and stakeholder expectations gives portfolio entities greater assurance that new board directors have the basic knowledge needed to fulfil their legal obligations and act in the interests of the entity and its stakeholders.

Some larger departments oversee multiple boards or a group of similar boards:

- DET oversees technical and further education (TAFE) institute boards

- DHHS oversees health services boards

- DELWP oversees catchment management authorities and water corporation boards.

We found that these portfolio departments developed comprehensive guidance documents for their boards, and offered formal and structured training programs covering duties, responsibilities and standards for public sector governance.

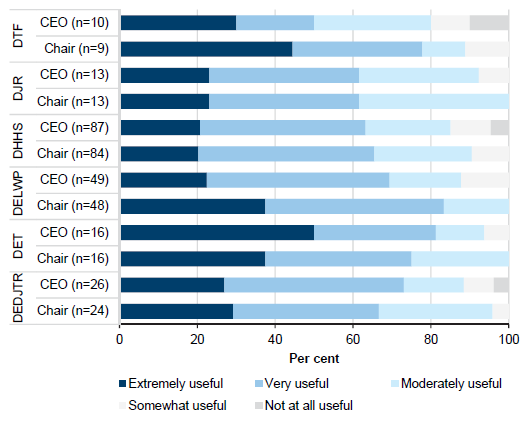

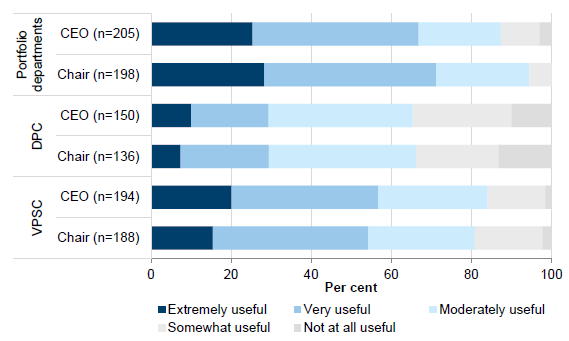

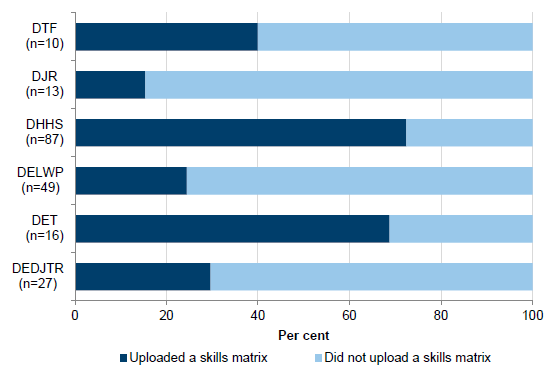

In our survey, 71 per cent of board chairs and 67 per cent of chief executive officers (CEO) of entities reported that the guidance and support they received from their portfolio departments was 'very useful' or 'extremely useful'. However, the survey also showed that opinions about the usefulness of guidance and support varied by department—DELWP's guidance was rated 'extremely useful' or 'very useful' by 83 per cent of relevant board chairs, whereas the Department of Justice and Regulation's (DJR) guidance was rated 'extremely useful' or 'very useful' by 62 per cent of relevant board chairs.

DJR does not provide sector-specific guidance or training for board directors. In contrast, DELWP provides sector-specific guidance on legislation, good governance and annual reporting requirements, the suite of board policies, the code of conduct, dispute resolution processes, expectations of internal and external engagement, and information on PAA requirements.

DET and DHHS also provide training to new members, an induction pack, summaries of duties and obligations, VPSC guidance materials, and information on meeting the PAA requirements. Figure 2A provides a breakdown of the survey results by sector.

Figure 2A

Survey results: Usefulness of the guidance and support materials that portfolio departments provide to their public sector boards

Note: DTF = Department of Treasury and Finance.

Note: We excluded DPC because there are only five entities in its portfolio. We also excluded respondents who chose 'not applicable' or did not answer the question.

Source: VAGO.

2.2.2 Oversight of board performance

The PAA requires that boards conduct performance assessments (discussed in detail in Part 3). It is therefore essential that portfolio departments collect information on boards' performance and make sure that boards complete assessments and self‑assessments of the CEO, board and directors.

Although all portfolio departments have structured frameworks to monitor their public entities' financial performance, their approach to monitoring boards' governance practices is ad hoc and fragmented. Practices vary between and also within departments.

Several departments told us that they need more guidance on evaluating board performance. Portfolio departments told us that they largely rely on their relationship with chairs and CEOs to ensure that entities self-report any governance issues. This approach does not consistently enable departments to identify and address governance issues at an early stage.

Portfolio departments that have not already done so should define a set of reporting requirements that boards must complete to fulfil their obligations, including attesting that conflicts of interest are managed and that board performance assessments are completed.

Better practice

We identified the following cases of better practice, although these are not yet fully or comprehensively implemented or applied across all entities within the relevant department:

- DELWP requires catchment management authorities to conduct a standard board performance assessment that includes an annual assessment of the board as a whole, the chair, and individual board directors. Catchment management authority boards then report annually to the minister, confirming:

- that board directors conducted performance assessments

- the actions taken to improve performance

- actions to improve performance planned for the following year

- any significant positive or negative result or finding for the minister's attention.

- DHHS has key performance indicators that require cemetery trusts classified as 'Class A' under the Cemeteries and Crematoria Act 2003 to attest that they have conducted board assessments and self-reported any significant issues.

- DEDJTR has recently begun a phased implementation of a governance framework for entities in its portfolio.

- DET requires TAFE boards to report annually on compliance with legal and ethical obligations under its strategic planning guidelines and requires that any breach be disclosed and steps taken to remedy the breach.

Portfolio departments need to develop a relationship management strategy that sets out the type of issues that boards should report to the portfolio department, how frequently meetings with the board should take place, and what reporting and documentation boards must provide. This can be tailored to the known risks or gaps in the entity.

Self-assessments

Section 81 of the Public Administration Act 2004 requires a board to ensure it has adequate procedures in place to assess its own performance. We found that boards typically assess their performance once a year, although they do not routinely provide reports of these assessments to portfolio departments.

Our survey found that 84 per cent of boards that conducted a performance evaluation did not send it to their portfolio department.

Although the board self-assessments we looked at were of varying quality, they were still an important indicator of performance. Departments have a role in promoting regular assessments. By not requiring boards to submit their assessments, departments are missing a valuable opportunity to assess the operation of the entity and identify any emerging risks. DEDJTR asks boards to confirm that they are completing annual self-assessments and assessments of individual directors, and an independent assessment every three years.

Relationship with departments

The boards we surveyed have positive working relationships with portfolio departments, despite some portfolio departments not hosting structured or regular meetings. The four boards we examined in detail stated that their relationships with relevant departments were effective. Communication consisted mainly of informal meetings and requests for advice from entities in the portfolio.

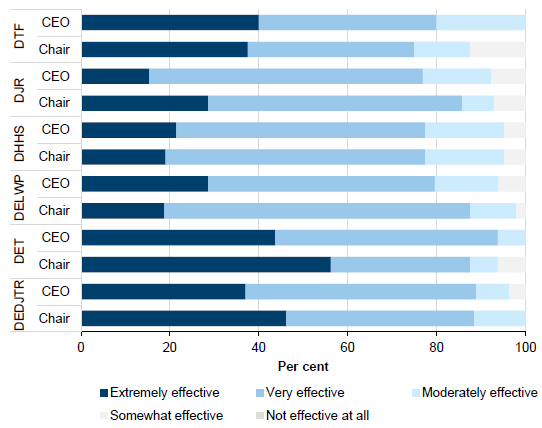

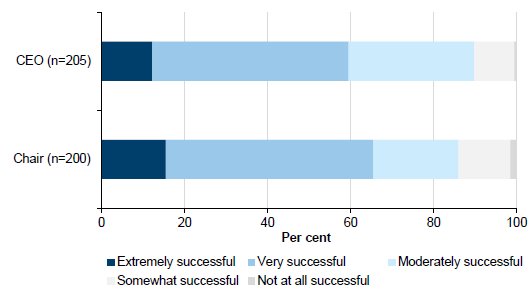

Our survey supports this finding. We found that 75–89 per cent of board chairs who responded and 77–94 per cent of entity CEOs who responded reported that they had 'very effective' or 'extremely effective' relationships with relevant portfolio departments.

Figure 2B shows the results for all departments.

Figure 2B

Survey results: Effectiveness of entities' relationships with their relevant portfolio department

Note: We excluded DPC because there are only five entities in its portfolio. We also excluded respondents who chose 'not applicable' or did not answer the question.

Source: VAGO.

2.3 Support from the Victorian Public Sector Commission

VPSC provides good-quality guidance and training to prepare board directors for the governance practices required under the PAA and other relevant legislation. It aligns with the better practice principles and sets a clear, whole-of-government framework. To enhance this guidance, VPSC could provide more information on conducting board assessments.

2.3.1 Guidance material

VPSC reviews its guidance material regularly, drawing on a number of sources to develop guidance on board governance. These include:

- observations and findings from the various reviews that VPSC conducts

- its working relationship with the Australian Institute of Company Directors

- industry better practice guidance

- legislative requirements and government policy directives.

Our survey showed that about 54 per cent of board chairs and 57 per cent of CEOs rated VPSC's guidance as 'very useful' or 'extremely useful'. Chairs and CEOs gave higher ratings—71 per cent and 67 per cent respectively—for the guidance they received from their portfolio departments. Two of the boards we examined in detail indicated they were aware of VPSC guidance and found it useful, but were more likely to seek guidance from their portfolio department on governance issues.

2.3.2 The Government Appointments and Public Entities Database

The Government Appointments and Public Entities Database (GAPED) contains information on board directors, including their remuneration and length of appointment. VPSC manages GAPED, and the portfolio departments input the data. GAPED has historically been plagued by data errors and gaps, but VPSC has recently carried out significant work to address a number of these issues.

VPSC has improved data reliability by making more data fields mandatory, improving user guidelines and providing additional training. Data on gender parity in boards is now up to date, and a new interface makes it easier to find information on expiring appointments and gender composition, and to screen for potential errors.

A draft Premier's Circular will reinforce portfolio departments' responsibilities to maintain GAPED.

2.4 Appointments and remuneration

As well as being responsible for boards within its portfolio, DPC reviews all submissions from portfolio departments on board appointments that require Cabinet approval under the Guidelines and provides advice to the Premier. It also publishes the Guidelines and advises portfolio departments on recruitment, appointment and remuneration processes for public sector boards.

The Guidelines clearly set out processes and key responsibilities for making appointments to a public sector board. However, the way that DPC classifies boards lacks a sound methodology, including appropriate and relevant indicators.

2.4.1 Appointment and Remuneration Guidelines

DPC's board classification matrix is confusing—boards and portfolio departments expressed concern that the classifications did not sufficiently recognise the level of risk and complexity that their boards negotiate.

The Guidelines outline four groups of boards—groups A, B, C and D—determined by a board's duties, such as decision-making, its statutory obligations and level of risk, and its size. Within these groups, there are several classification bands, which determine remuneration rates. These classifications take into account the nature of the work conducted by the board.

Current anomalies and inconsistencies in the classifications lead to unfair outcomes in remuneration for directors. Departments also apply the classifications inconsistently. Past reviews by DPC and the Victorian Ombudsman have highlighted these issues, but DPC has not adequately addressed them in updates to the Guidelines—including the most recent substantive update in October 2015.

One department advised us that inconsistencies in the classification of its entities affected its ability to attract skilled people to boards, particularly boards in regional areas.

In 2016, DHHS asked VPSC to review the classifications and remuneration of public health boards. DHHS initiated this review because it believed the current remuneration of its public health service boards did not adequately take into account inherent risks, such as the higher risk profile of some health services. DHHS is currently reviewing the VPSC report findings.

Recently, DPC's governance branch conducted a review of the remuneration and classification of boards. The findings of this review are still preliminary, as DPC is waiting for the findings of our audit before taking further action on classification and remuneration.

2.4.2 The Department of Premier and Cabinet's oversight of the board appointment process

For appointments of board directors that require Cabinet approval, DPC advises the Premier on whether it supports the appointment and whether the appointment meets the requirements of the Guidelines. DPC also provides advice on whether the candidate has the required skills and experience for the board, and recommends whether the candidate should be appointed or reappointed to a board.

DPC is sufficiently involved in the appointment process to ensure that portfolio departments have followed the process described in the Guidelines. We examined a sample of Cabinet submissions and DPC briefs, and found that they generally contain sufficient information to give assurance that portfolio departments have followed the correct processes.

DPC has no oversight role for board appointments that do not require Cabinet approval under the Guidelines.

3 Board governance practices

Under the Public Administration Act 2004 (PAA), a public sector board is responsible for:

- meeting legislative requirements and setting the strategic framework of the entity

- having and using policies and procedures that are relevant to the entity

- effectively overseeing management activity.

This Part examines whether public sector boards demonstrate effective governance practices. The findings draw on our survey of the chairs and chief executive officers (CEO) of 212 public sector entities, as well as our detailed case studies of four boards—Box Hill Institute and Centre for Adult Education (Box Hill Institute), CenITex, Fed Square Pty Ltd (Fed Square) and the Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute (Peter Mac).

As outlined in Part 1 of this report, boards are classified into groups for remuneration purposes. Where relevant, this Part includes survey findings on three of the groups:

- Group A boards—typically overseeing entities managing larger assets with a high turnover

- Group B boards—often regulatory boards overseeing entities with smaller assets and turnover

- Group C boards—management boards of smaller entities.

There were no Group D boards in the survey sample.

3.1 Conclusion

The public sector boards we examined in detail (the four case study boards) demonstrated better practice in most areas of governance. Boards are responsible for setting the strategic direction of the entity, monitoring operations and compliance, and reporting on performance. We found that the boards played a key role in developing strategic documents, but they could improve their compliance with some governance requirements.

3.2 Policies and operations

Public sector boards have specific accountabilities derived from their statutory responsibilities, and are also expected to abide by codes of conduct. Boards must have procedures in place to comply with the Code of Conduct for Directors of Victorian Public Entities, deal with conflicts of interest, manage risks, and assess and manage their performance.

Guidance from the Victorian Public Sector Commission (VPSC) outlines legal requirements and the procedures boards need to have in place to address their responsibilities, as well as mandatory requirements and how to achieve better practice. These guidelines are in line with the governance requirements set out in the PAA.

Recommended practice and good board governance principles are also outlined in the Premier's Circular No. 2015/02 and a range of public sector governance guides.

Overall, we found that boards have accountability structures and effective mechanisms in place to carry out their governance roles. However, boards' compliance with certain requirements is inconsistent and needs improvement.

3.2.1 Interest disclosures and codes of conduct

Probity in governance is a basic requirement for the successful operation of public sector boards to ensure they effectively manage the risk of conflicts of interest, both financial and non‑financial. Codes of conduct set the rules and expectations for board directors.

In our survey of 212 public sector entities, we asked boards to provide evidence of the controls and mechanisms they are required to have under the PAA. The survey found that nearly one in four entities had not fully complied with selected PAA governance requirements, such as declaring financial interests, managing risks and conducting board assessments.

Disclosure of interests

Section 81(1)(f) of the PAA requires that board directors disclose both financial and non‑financial interests at board meetings and that boards record these disclosures in the minutes of the meeting. In total, almost 78 per cent of boards we surveyed reported that it is a standing practice for board directors to declare financial and non-financial interests at every board meeting. However, 37 boards do not regularly declare interests and nine boards never do it. This increases the risk that board directors could influence matters for their own personal or financial gain—even if inadvertently.

Figure 3A shows how frequently surveyed boards disclose or declare financial and non-financial interests.

Figure 3A

Survey results: Frequency of board directors disclosing financial and non-financial interests, by board type

|

Frequency of disclosure |

Group A |

Group B |

Group C |

Total |

Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

At every meeting |

79 |

22 |

58 |

159 |

77.6 |

|

At some or most meetings |

15 |

4 |

18 |

37 |

18.0 |

|

Never |

2 |

0 |

7 |

9 |

4.4 |

|

Total responses |

96 |

26 |

83 |

205 |

100 |

Note: These responses are from board chairs only.

Source: VAGO.

In contrast, the four case study boards comply with policies and applicable legislative requirements for declaring conflicts of interest and gifts, benefits and hospitality. All four boards disclose conflicts of interest at every meeting.

At Fed Square, Box Hill Institute and CenITex, we found that board directors are required to complete an annual declaration of interests. At every board meeting, chairs recognise ongoing declarations of interests and invite directors to declare any new private interests that may be a conflict of interest. This is then clearly documented in the board minutes.

Codes of conduct

Codes of conduct describe how board directors are expected to behave and may include guidance on establishing a quorum and resolving disputes. Despite the requirements of the PAA, more than a quarter of the boards we surveyed (just under 27 per cent) do not have a code of conduct. It is concerning that board decision‑makers who negotiate complex matters of public interest fail to define the expected behaviours for good governance.

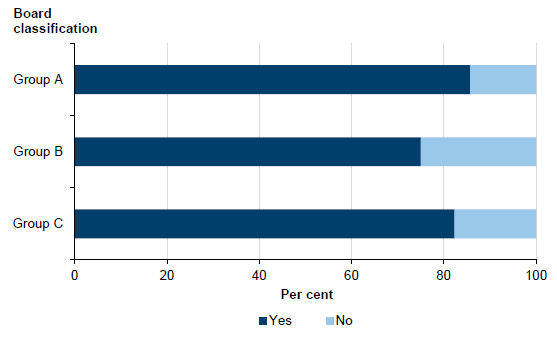

Figure 3B shows the proportion of boards that have a formal code of conduct.

Figure 3B

Surveyed boards that use a formal code of conduct, by board type

|

Board group |

Yes |

No |

Number of responses |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Group A |

73 |

23 |

96 |

|

Group B |

18 |

8 |

26 |

|

Group C |

60 |

24 |

84 |

|

Total |

151 |

55 |

206 |

|

Total (%) |

73.3 |

26.7 |

100 |

Note: These responses are from board chairs only.

Source: VAGO.

In contrast to this finding, all four case study boards have a code of conduct, charter or legislated equivalent.

3.2.2 Conduct of board meetings

Board directors are expected to be accountable for their behaviour and decisions, as stated in section 7(d) of the PAA. This includes:

- working in a transparent manner

- accepting responsibility for their decisions and actions

- seeking to achieve best use of resources

- submitting themselves to appropriate scrutiny.

We found that most boards have effective practices in place to conduct their board meetings and that most board papers are of a high quality.

Case studies

The four case study boards had sound procedures in place for conducting meetings. When the CenITex board expanded in 2016 it included customer representatives. This change in board composition means that directors now have different expectations for board papers.

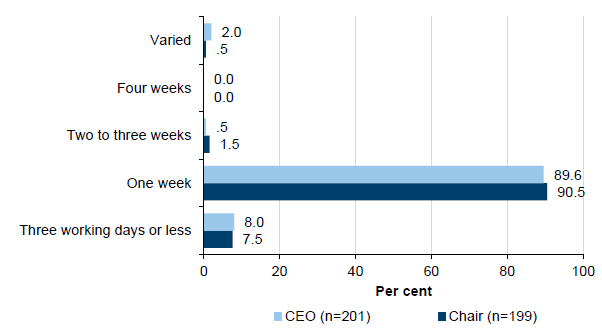

All four boards had regular meetings with high-quality papers that were received at least a week prior to the meeting. At Box Hill Institute, Peter Mac and Fed Square, an annual meeting calendar and agenda identify the major strategic and operational tasks that the board and subcommittee should complete or consider. This approach gives directors greater clarity and predictability and should be particularly useful for new directors and portfolio departments seeking an overview and schedule of major initiatives.

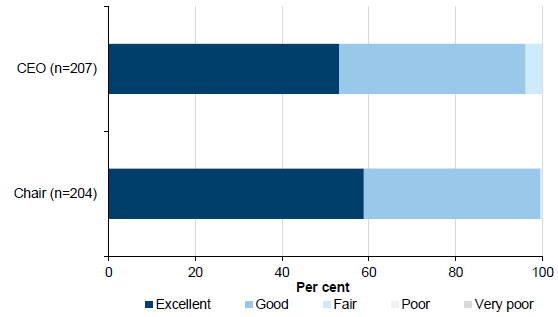

Survey results

The findings from our survey of 212 public sector entities were consistent with the case studies. Most entity CEOs and board chairs responded that they have suitable procedures in place for the preparation and conduct of board meetings. About 86 per cent of board chairs and 89 per cent of CEOs rated the quality of board papers as 'good' or 'very good'. No respondents rated the quality of their board papers as 'poor' or 'very poor'.

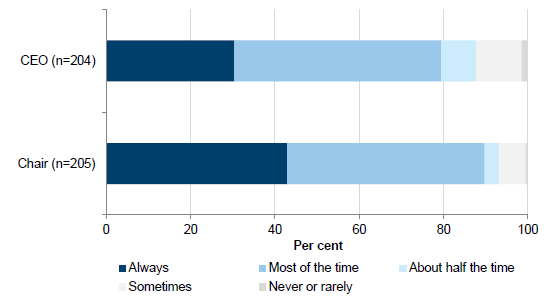

The survey found that board papers are generally provided in a timely manner, with 91 per cent of board chairs saying that board papers are circulated a week before the meeting. Only 8 per cent of board chairs said they received their papers within three days before a meeting.

Nearly all respondents reported that the conduct of meetings was 'good' (41 per cent of chairs and 43 per cent of CEOs) or 'excellent' (53 per cent of CEOs and 59 per cent of chairs).

3.2.3 Strategic planning and oversight

Boards are responsible for setting the strategic direction of the entity and overseeing its performance.

Better practice guidance on the governance of public sector boards recommends that boards:

- define their role and contribution to the strategic planning of the entity

- set time aside regularly to consider the entity's strategic plans

- receive regular updates from the CEO or entity head on the progress against strategic goals

- review progress and refresh objectives and targets.

We found during our detailed examination of the four boards and through our survey results that boards perform these functions well.

Developing the strategic plan

All four case study boards demonstrated that they played a key role in developing their entity's strategic plan. At the start of the planning cycle, each board held at least one dedicated workshop to understand their operating environment, identify strategic long‑term goals and determine how to achieve these goals. Each board then received regular updates on the progress of the plan's development, including reviewing drafts and providing feedback.

From the available evidence—which included minutes of meetings, workshops and final plans—we could not determine the level of input or usefulness of the boards' feedback. However, we could conclude that board input is structured and scheduled to allow sufficient time for review. Further, all four boards were involved in approving their entities' strategic plans.

Our wider survey results supported these findings, with 91 per cent of board chairs and 84 per cent of entity CEOs indicating their board is 'very involved' or 'extremely involved' in strategic planning for the entity. Further, 80 per cent of CEOs and 90 per cent of chairs responded that the board has had 'considerable impact' or 'extensive impact' on the entity's most recent strategic plan or equivalent.

Overseeing implementation

Boards are responsible for monitoring an entity's operations, and it is imperative that boards prioritise overseeing progress against strategic plans. The quality and extent of boards' oversight of how entities implement their strategic plans varied across the four case study boards. The release of new corporate plans and governance reviews impeded two boards' ability to monitor performance.

We identified better practice from one of the case study boards. Peter Mac organises its board agenda items according to the strategic directions outlined in its strategic plan. This practice clearly demonstrated alignment of the board's oversight activities with the strategic plan. Peter Mac is committed to continuous improvement and is currently in the process of developing a strategic scorecard that will give the board a clear overall assessment of the entity's progress in achieving its strategic goals.

CenITex is reviewing its three-year corporate plan. This is an opportunity for CenITex to provide the board with progress reports on the implementation of its strategic priorities in addition to regular operational updates.

Box Hill Institute's board receives a detailed monthly scorecard against key performance measures, which provides directors with a sound oversight of operations. The scorecard could be enhanced by linking it more explicitly to the themes of the strategic plan.

Fed Square also has a new corporate plan for 2016 to 2020. It receives periodic updates on the entity's major strategies, such as its asset management plan and information technology strategy.

The majority of chairs (90 per cent) and CEOs (79 per cent) we surveyed responded that the board refers to strategic plans as part of its decision-making process all or most of the time.

3.3 Skills and diversity

Better practice board governance involves actively seeking to appoint board directors who have the skills the board needs to carry out its functions—such as legal or finance experience or medical expertise. Boards should also reflect the diversity in Victoria's broader socio‑economic make up, including location, language and cultural background, age group, sexuality and disability.

We found that a significant number of boards cannot clearly demonstrate that their directors have the required or optimum mix of skills to effectively carry out their duties and responsibilities. The government's expectation of 50 per cent female board representation for paid board appointments is being achieved, although there is no reliable way to assess boards' cultural and social diversity.

3.3.1 Skills

A skills matrix helps a board to understand training needs and track the skills and competencies of its directors. It is a valuable tool for new appointments, because it allows boards to readily identify and fill skills gaps. Despite the value of a skills matrix, some boards do not routinely maintain them.

Case studies

In the four case study boards, we found that three had skills matrices in place—Peter Mac, Box Hill Institute and Fed Square. The matrices show that these boards have the optimal mix of knowledge and skills required to discharge their duties. CenITex did not have a matrix because it believes it is the portfolio department's responsibility to determine whether the skills of candidates match the board's requirements.

The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) developed and maintains Peter Mac's matrix, which is used to inform future appointments to the board. Although the appointment process is managed by DHHS, we found that for the most recent appointments the chair of the Peter Mac board had actively sought directors with the skills to fill identified gaps and was successful in obtaining them.

Three boards have undergone recent significant changes to the composition of their boards:

- Box Hill Institute—new board appointed in 2016

- Fed Square—almost half the board newly appointed

- CenITex—board expanded to include government representatives and an additional director.

To help with Fed Square's appointments, the chair used a skills matrix to identify gaps, and then provided advice to the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources on potential candidates who may have the required skills.

Legislative changes were made to improve the composition of all technical and further education (TAFE) boards. TAFEs provide a current skills matrix to the Department of Education and Training at least annually and before each appointment by the minister. For some other appointments there is no clear rationale for how the new directors contribute to an appropriate skills mix for the board or address any identified skills gaps. We also found no evidence that boards provide their skills matrix to the Department of Premier and Cabinet to better inform its appointment decisions.

Survey results

In the wider survey, 67 per cent of CEOs stated that their board has a current board skills matrix, but we could only verify this for 48 per cent of respondents. The most common reason cited for not having a skills matrix was that the department or minister determines board appointments. These boards do not recognise the value of being equipped to identify skills gaps and proactively advise the minister of these requirements.

Only 34 per cent of surveyed Group A boards and 33 per cent of Group B boards had a skills matrix. In contrast, 70 per cent of Group C boards had a skills matrix. This is concerning given that Group A boards typically oversee entities that manage larger financial assets, profit and turnover.

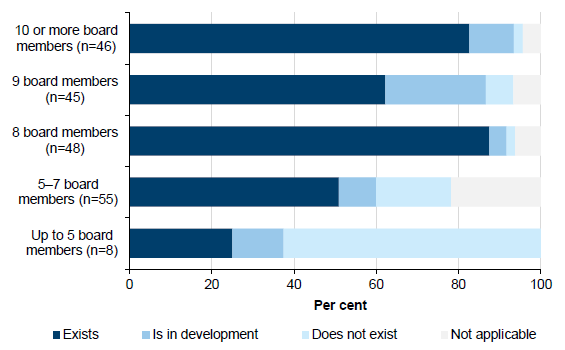

Smaller boards, regardless of remuneration classification, are much less likely to maintain a skills matrix than larger ones. Where boards had five directors or fewer, 63 per cent said that they do not maintain a skills matrix, compared to only 2 per cent of boards with 10 or more directors.

3.3.2 Gender, age and location

The Premier's Circular No. 2015/02 Good Board Governance confirms that departments and non-departmental entities, including judicial and quasi-judicial bodies, should help ministers to discharge their responsibility by designing board recruiting processes that are based on merit and are fair, open and diverse, as outlined in Figure 3C.

Figure 3C

Criteria for developing recruitment and selection processes for the appointment of new board directors

|

Criteria |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Merit-based |

|

|

Fair |

|

|

Open |

|

|

Diverse |

|

Source: VAGO, based on the Premier's Circular No. 2015/02 Good Board Governance.

Gender

The government has set a number of expectations for the make-up of public sector boards, including that, from 2015, 50 per cent of new paid board appointments should be women, and that boards should broadly represent the cultural and social diversity of their community.

The average gender composition of the 212 boards we surveyed was 50 per cent women, which is above the statewide public sector board average of 35 per cent. The four case study boards are also consistent with this finding—female directors account for at least half of each board.

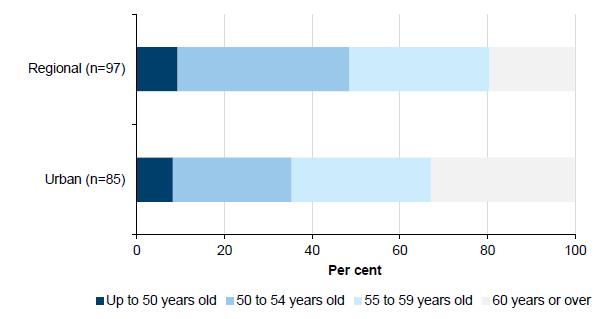

Age

For the majority of boards we surveyed, the average age of directors was between 50 and 59 years old. This indicates that boards do not reflect the working age profile of the Victorians population, which ranges from 15 to 64 years old.

The average age of board directors was different in urban and regional areas—urban boards are much more likely to have board directors over 60 years old than regional boards, while regional board directors are more likely to be aged between 50 and 52 years old.

Location

Regional boards found it more difficult to source directors with required skills than urban boards—particularly legal, financial and governance experience. Of all boards surveyed, 49 chairs identified directors with legal skills as being difficult to recruit, but 42 of these responses (86 per cent) came from regional boards. Figure 3D outlines the contrasting results.

Figure 3D

Survey results: The skill set or attribute that has been the hardest to recruit to the board, by urban or regional location

|

Skills |

Urban |

Regional |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Sector experience |

26 |

28 |

54 |

|

Legal |

7 |

42 |

49 |

|

Financial |

17 |

27 |

44 |

|

Regional location representation |

18 |

8 |

26 |

|

Board or governance experience |

3 |

15 |

18 |

|

Risk |

3 |

14 |

17 |

|

Human resources |

5 |

8 |

13 |

|

Other |

37 |

40 |

77 |

|

No response |

8 |

3 |

11 |

Note: Respondents could select multiple responses.

Source: VAGO.

3.4 Risk management

The board plays an important role in overseeing the entity's risk management. The PAA requires boards to inform the responsible minister and department head of major risks to the public entity and of the risk management systems in place to address those risks.

The Victorian Government Risk Management Framework requires entities to annually attest to their compliance with the framework. This includes boards being satisfied that their risk management framework:

- is reviewed annually to ensure it remains current and is improved, as required

- supports the development of a proactive risk-management culture within the agency.

Survey results

Most of the boards we surveyed have adequate procedures in place to identify and manage risk—83 per cent of surveyed boards provided valid copies of their risk registers. We found these registers to be of high quality, and most included key elements of a good plan, including assigned responsibilities, treatment plans and heat mapping.

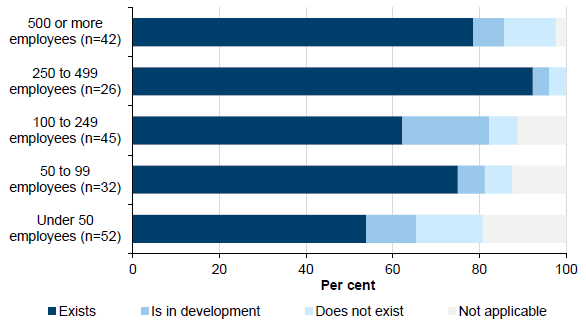

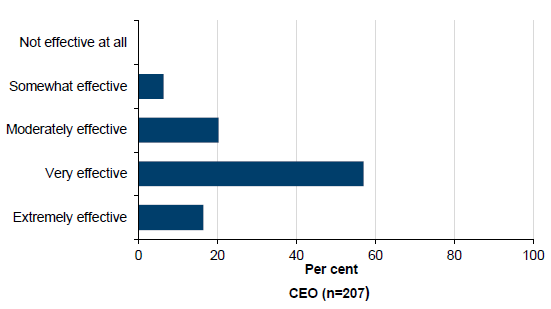

Figure 3E outlines the proportion of Group A, B and C boards that have risk registers.

Figure 3E

Survey results: Proportion of entities that have a risk register, by board type

Note: Results include responses from CEOs only.

Source: VAGO.

Figure 3E shows that between 14.3 and 25 per cent of these groups do not have risk registers. This means that these boards cannot demonstrate to the minister and department head that they are effectively monitoring and addressing major risks, which is a requirement under the PAA.

Case studies

We found that the four case study boards had adequate risk management frameworks in place that aligned with better practice and legislative requirements.

Each board has a documented risk management policy or framework and has established a board subcommittee that more actively reviews and monitors the entity's management of risks and internal audits. These subcommittees then report to the board on significant risk management issues.

CenITex and Box Hill Institute have subcommittees that review risk registers at every meeting. CenITex's audit and risk committee meets quarterly and started tabling its minutes with the board in January 2017. Fed Square's and Peter Mac's board subcommittees review risk registers six monthly, but new or escalated risks occurring outside of this review cycle are reported at the next meeting. To ensure timely management, in both entities these risks are reported to executive management, which meets more frequently.

For management of clinical risks, Peter Mac has a quality board subcommittee. This subcommittee includes Peter Mac's key clinical staff who have the necessary skills to oversee these more specific risks. This practice is essential to good clinical governance.

3.5 Performance assessment

The PAA requires boards to assess both the performance of the board as a whole, and of individual directors. The VPSC and other better practice guidance recommend that boards complete these assessments annually. VPSC guidance also states that a key duty of the board is to assess how well the CEO is performing his or her role and to make any relevant performance-related decisions about the CEO.

We found that most boards regularly review the performance of the board collectively and the performance of the CEO, but do not review the performance of individual board directors.

3.5.1 Assessing performance of the CEO

Our survey found that 97 per cent of boards evaluate their CEO's performance annually or more regularly. All four case study boards have robust processes in place to review and assess their CEO's performance.

The CEOs of Peter Mac, CenITex and Box Hill Institute conduct self-assessments annually against a clear set of performance indicators. At CenITex, the board then reviews the CEO's assessment. At Peter Mac and Box Hill Institute, the board's remuneration subcommittee reviews the assessment. All CEO self‑assessments are documented, and at Peter Mac and Box Hill Institute the remuneration subcommittee's assessment of the CEO's performance is minuted. Fed Square has a robust documented process for assessing its CEO's performance. This was not applied in 2015 and 2016 due to CEO turnover and the interim CEO arrangements in place during that time.

3.5.2 Assessing performance of the board and individual directors

Performance assessments provide value by highlighting where the board has performed well and identifying where improvements can be made. We found that, although most boards we surveyed regularly assess the board's collective performance, 42 per cent do not assess the performance of individual board directors regularly or at all.

Board assessments

All four case study boards undertake assessments of the board's performance annually. However, only Box Hill Institute had a documented process to action the issues identified in the board assessment, and this was the most developed and transparent approach we observed. Without a documented process, we were not able to examine the effectiveness of Peter Mac's and CenITex's responses to identified performance issues.

Fed Square told us that they have a process but that most recent board assessments did not identify any significant issue that needed action. We have recommended that VPSC provide additional guidance to boards on completing performance assessments.

In our wider survey, 80 per cent of boards indicated that they conduct frequent assessments of their performance, but only 69 per cent of boards provided a copy of their most recent board assessment.

The quality of these assessments varied between entities, and boards felt they needed additional guidance on how to conduct good performance assessments. Areas of better practice we identified for improving assessments included:

- using benchmarks to help assess the board's performance against past or industry performance

- incorporating feedback from other key stakeholders, such as the CEO

- engaging an external consultant to facilitate the assessment process.

Director assessments

The PAA requires that boards assess the performance of individual directors, but we found that this is not occurring in the three applicable case study entities and 42 per cent of boards in the wider survey.

Assessing the performance of individual directors provides entities with a valuable overview of the contributions that individual directors make and provides information on the merit of reappointing directors to the board.

A larger proportion of Group A entities (64 per cent) conducted frequent performance assessments of individual board directors compared to boards in Group C (57 per cent) and Group B (44 per cent).

None of the case study boards conducted performance assessments of individual board directors. Portfolio departments and VPSC need to better promote this requirement so that boards comply with the PAA, and reappointments are fair and merit-based.

3.6 Succession planning

Succession planning is a better practice principle for good governance. It provides a strategy for putting acting arrangements in place if there are sudden departures or long absences. It is also an opportunity for the board to identify its future skills needs. Despite its importance, boards do not routinely carry out succession planning.

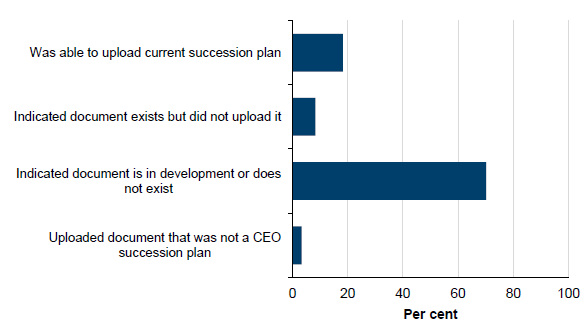

Because the CEO is responsible for managing the entity, it is essential that there is a succession plan that allows the entity to promptly, at least temporarily, replace the CEO if he or she departs suddenly or is absent for a long period. Despite this, most boards do not have a CEO succession plan in place.

Only 16 per cent of survey respondents were able to provide a CEO succession plan document. A higher proportion of boards in Group B (89 per cent) and Group C (90 per cent) did not have a CEO succession plan, compared to Group A (77 per cent). Common reasons given for not having a plan included that the CEO is recruited externally, that the entity is very small, and that there is no need to document such plans.

The four case study boards reflect the survey results, with only Peter Mac having identified a potential successor for its CEO. We note that having a succession plan can be challenging for smaller entities such as Fed Square, where new CEOs are more likely to be recruited externally. Nonetheless, Fed Square told us that they have managed to maintain service continuity internally during the recruitment process. CenITex and the Department of Treasury and Finance, its portfolio department, advise that despite not having a documented process they are recruiting to ensure staff are appropriately skilled to step in to the CEO role if required.

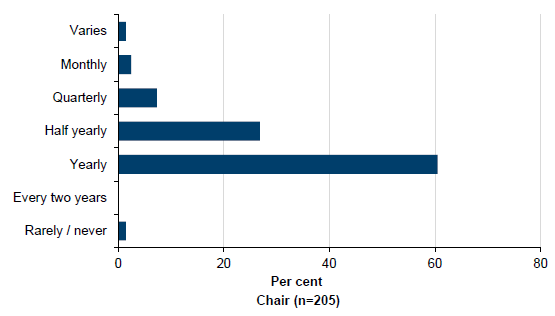

Given the importance of the CEO's role, where possible, the board, the entity and portfolio department should develop a clear succession plan so that entities can maintain continuity of services in the event of a sudden departure or change in leadership.