Managing Contaminated Sites

Overview

The Department of Planning and Community Development, the Environment Protection Authority and councils are not effectively managing contaminated sites, and consequently cannot demonstrate that they are reducing potentially significant risks to human health and the environment to acceptable levels.

This audit identifies a range of cases that demonstrate the adverse consequences that flow from a lack of accountability and clarity, and the gaps in the regulatory framework. Most notably, there are cases of inaction by responsible entities in dealing with contamination; this inaction being driven in part by an undue emphasis on avoiding legal and financial liability, rather than protecting human health and the environment.

Significant mismanagement in at least one case has led to the possibility that human health has been impacted as a result. The hope is that this and the other case studies are not typical. However, there is little assurance that this is the case.

The ability to assess and mitigate health, environmental and financial risks associated with contamination is hampered by the lack of complete and reliable information on the number and location of contaminated sites, and the nature and extent of contamination. The responsible entities have been neither proactive nor systematic in obtaining this information. Until this information is known, agencies cannot reliably plan and prioritise actions.

Managing Contaminated Sites: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER December 2011

PP No 90, Session 2010–11

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Managing Contaminated Sites.

Yours faithfully

![]()

D D R PEARSON

Auditor-General

7 December 2011

Audit summary

Contaminated sites are land, and in most instances groundwater, where chemical and metal concentrations exceed those specified in policies and regulations. The location and number of contaminated sites in Victoria is not accurately known, as this information is not routinely collated. The most recent desktop assessment in 1997 estimated there were around 10 000 contaminated sites in Victoria.

Contamination in Victoria has generally been caused by the management practices of earlier generations when environmental regulations were less onerous on polluting activities. Depending on the nature and extent of the contamination, and how the site is used, contaminated sites may pose imminent or long-term risks to human health and the environment.

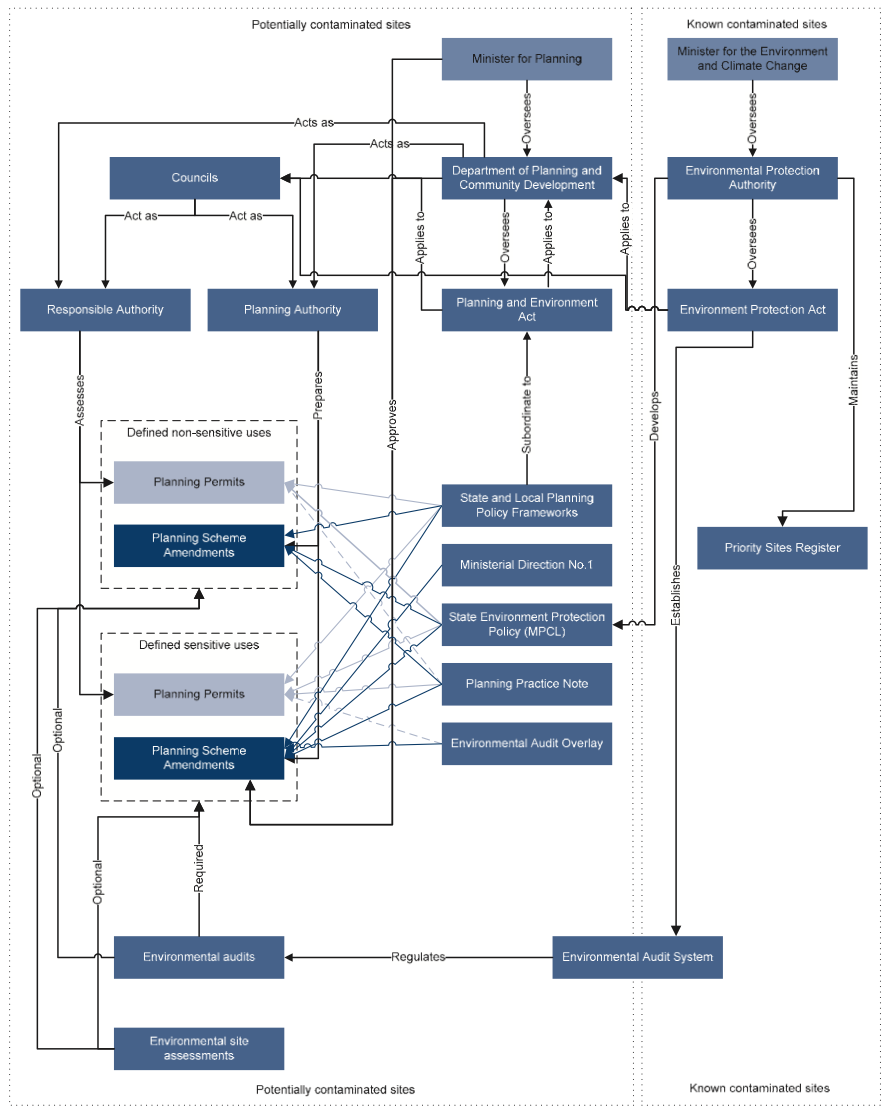

Potentially contaminated and known contaminated sites are regulated through a framework that encompasses the Planning and Environment Act 1987, the Environment Protection Act 1970, and a range of complementary regulatory instruments. Around 80 per cent of situations involving contaminated sites are dealt with through the planning element of the framework, and the remaining 20 per cent are dealt with through the environment protection element.

This audit, first foreshadowed in our 2009–10 Annual Plan, and commenced in March 2011, examined how contaminated and potentially contaminated sites are managed, particularly where a ‘sensitive use’ of the land is involved.

Conclusion

The Department of Planning and Community Development (DPCD), the Environment Protection Authority (EPA) and councils are not effectively managing contaminated sites, and consequently cannot demonstrate that they are reducing potentially significant risks to human health and the environment to acceptable levels.

This is largely because the complex regulatory framework that has evolved to deal with contaminated sites has significant gaps, and key elements lack clarity. In many cases, this has led to a lack of accountability and responsibility, and subsequent inaction.

In this audit we identified a range of cases that demonstrate the adverse consequences that flow from a lack of accountability and clarity, and gaps in the framework. Most notably we identify cases of inaction by responsible entities in dealing with contamination; this inaction being driven in part by an undue emphasis on avoiding legal and financial liability, rather than protecting human health and the environment.

Indeed, Case Study 1 is in itself a case study of significant mismanagement, with the possibility that human health has been impacted as a result. The hope is that this, and the other case studies in Appendix A, are not typical. However, there is little assurance that this is the case.

Past inaction has contributed to the inconsistent interpretation and application of the framework by councils and DPCD. Councils have also contributed to these poor outcomes through their lack of rigour in applying their own internal systems and processes to manage the risks associated with the development and management of contaminated sites.

Significantly, no one entity is accountable for oversight of the effectiveness of the regulatory framework in operation. Further, responsibility for managing the high-risk sites has been neither clearly defined nor accepted by any entity.

High-risk sites are those known to be contaminated, and that pose long-term rather than imminent risks. They include sites where the party responsible for contamination is known or can afford to clean the site (legacy sites), and where the responsible party cannot be identified or insolvency prevents clean-up (orphan sites). For orphan sites not proposed for redevelopment, contamination will remain unmanaged unless the state steps in.

Framework weaknesses have been known for at least 10 years, yet action to systematically address them began only within the last year. While these reviews are a positive initiative, they are being planned in an ad hoc manner and occurring in isolation from one another. This further demonstrates the need for leadership and for effective coordination across the system.

The ability to assess and mitigate health, environmental and financial risks associated with contamination is also being hampered by the lack of complete and reliable information on the number and location of contaminated sites, and the nature and extent of contamination. The responsible entities have been neither proactive nor systematic in obtaining this information. Until this information is known, agencies cannot reliably plan and prioritise actions.

Findings

The contaminated sites regulatory framework

The framework’s regulatory instruments, established and updated over a 20-year period, have evolved separately and have been implemented in an ad hoc basis by the EPA and DPCD in response to specific issues and circumstances.

In several instances, the instruments and their interplay have made the framework unnecessarily complex and unclear. This is particularly so for the Environmental Audit Overlay, Ministerial Direction No.1 for Potentially Contaminated Land and Potentially Contaminated Land: General Practice Note in relation to the requirements for, and guidance around, environmental audits and assessments.

In addition, there are many gaps in the framework—most of which have been known to DPCD and the EPA since at least 2000—that have affected the operation of the framework. These gaps relate primarily to the coverage of the regulatory framework, and the lack of any requirement to report contaminated sites to regulatory agencies; even if risks to human health and the environment are known. Actions to address these gaps only commenced in late 2010.

Governance of the contaminated sites system

Oversight and accountability

With around 100 entities involved in regulating and managing contaminated sites, clear accountability for the development, operation and effectiveness of the overall system is critical. Single point accountability, where one entity oversees the system and processes, and is accountable for its performance, is an effective approach to good governance.

There is, however, no single entity responsible for oversight of the planning and management of potentially contaminated and contaminated sites, or for assessing the effectiveness of the system or framework. The contaminated sites regulatory system operates instead in an uncoordinated way, with each entity managing contamination issues in isolation from the others. As a consequence, there is not a cohesive statewide strategic approach to the planning and management issues associated with potentially contaminated and contaminated sites.

Roles and responsibilities

Clear roles and responsibilities minimise the risk of overlap and duplicated effort. They also establish accountability and attribute responsibility for the success or failure of initiatives. While roles have been established under legislation and the contaminated sites framework, these are not clearly understood or agreed by all stakeholders. In addition, there are gaps in the roles where no agency is accountable or responsible.

The EPA is responsible for regulating contaminated sites where the contamination poses an imminent danger to human health or the environment, and it has issued either a pollution abatement notice or clean-up notice. It also regulates contaminated sites owned or managed by entities that it licenses.

However, there is no agency responsible for oversight of the system in relation to sites that are known to be contaminated and where the risks to human health and the environment may be long-term rather than imminent. Nor does any one entity have oversight of the management of orphan sites.

Issues around the management of orphan sites have been known for at least 11 years, particularly in relation to the lack of responsibility and gaps in the legislation, and there has been a range of recommendations made to address them. Very little action has been taken and many of the issues remain, especially the ongoing risks to human health and the environment.

Risk management

Risk management is fundamental to effective public sector administration. It enables entities to systematically identify and manage risks and opportunities, and also to prioritise actions. Risks can apply at an organisation or statewide level.

For the management of potentially contaminated and contaminated sites, key inputs into managing risks include knowing where these sites are, whether they are contaminated, the extent and type of contamination and the potential impact on human health, the environment or amenity.

There is no systematic approach within the three councils audited, the EPA and across the state public sector generally, to identify and assess the risks from potentially contaminated and contaminated land. Risk management activities are limited and do not take a statewide perspective—even though this is a statewide issue.

An absence of information about contamination across Victoria means that risk management activities are not adequately informed. As a consequence, there is no assurance that the current regulatory approach is the appropriate approach to manage risks associated with site contamination.

Applying the regulatory framework

Across the audited planning authorities (entities that prepare planning scheme amendments) and responsible authorities (entities that make decisions on planning permit applications), processes and systems to assess and approve planning applications do not provide adequate assurance that there is compliance with framework requirements.

Each authority had implemented systems and processes for the assessment and approval of planning applications. However, there were significant variations within and between the councils audited in terms of the consistency, transparency and rigour of the decisions.

Variation in processes between councils largely stem from differences in interpreting the ambiguity or gaps in the framework. The differences within councils were largely due to a lack of rigour in applying internal processes and systems.

Technical capability

One of the key issues in effectively implementing the framework is the lack of guidance under the framework about how responsible and planning authorities should assure themselves that the land is fit for its intended use.

To perform this work effectively and to appropriately inform planning decisions, planning and responsible authorities need to understand the regulatory framework. They also need to reliably comprehend and purposefully deal with the findings and recommendations from environmental site assessments and audits, while also assuring themselves that the assessments and audits are technically sound.

Around 80 per cent of contaminated site issues are being dealt with by councils, as planning and responsible authorities, however, the councils audited did not have the technical capability required to manage the complex issues associated with contaminated sites.

To address gaps in their technical capability, councils rely heavily on legal advice to clarify planning and legal issues. They do this to minimise not just the risk of an incorrect decision, but also to minimise their potential liability associated with potentially contaminated and contaminated sites.

Funding

Addressing contamination can be expensive. There are costs involved in undertaking assessments and audits, and significant costs involved in cleaning up contaminated sites. The majority of these costs are borne by the private sector through the planning processes, driven by commercial interests. However, there are also significant costs to the state and councils. This is particularly so where Crown land or municipal-owned land has been identified as contaminated, or where the state has to step in to clean sites as a last resort—typically for orphan sites.

The aggregate cost to the state and councils for remediation of all contaminated sites is unknown because of the lack of complete and reliable information about contamination. Councils advise that the cost of assessing and cleaning up is more than is available in their budgets, and that the lack of available funding to manage contaminated sites is an impediment to managing the risks.

The state government and councils, however, cannot reliably determine and prioritise their financial liabilities until environmental site assessments of all known sites are completed. Until this is done, they cannot substantiate claims that inadequate resourcing has contributed to historically poor management of contamination issues or inaction around known contaminated sites that pose a risk to human health and the environment.

Adherence to the framework

Effective compliance monitoring and enforcement action should assure the community that those developing or building on contaminated sites adhere to conditions designed to protect human health and the environment.

The framework requires councils and other responsible authorities to undertake compliance monitoring activities for planning scheme amendment provisions and planning permit conditions. Despite this requirement, there is no routine compliance monitoring, and consequently little enforcement activity. This is primarily because these entities have not adequately resourced or prioritised these activities.

Monitoring audit conditions

The main compliance monitoring activities that councils should undertake relate to environmental audit conditions. These conditions must be implemented for the site to be suitable for its proposed use, and typically relate to the development or ongoing management of a site. They include concreting contaminated soil exposed areas or capping contaminated soils on site. Ongoing management conditions include the continued management and monitoring of the groundwater and vapours, or refer to the monitoring and maintenance of equipment to manage contamination issues.

None of the three councils audited undertook routine, risk-based compliance monitoring, and as such they could not demonstrate whether statements of audit conditions are being complied with. Compounding this, if the councils wanted to undertake routine risk-based monitoring, their systems are not adequate to support such monitoring. They did not have systems to record audit conditions, and they therefore lacked the basic information required to inform compliance monitoring.

All councils audited acknowledged the need to improve compliance and enforcement activities and procedures associated with contaminated sites. Brimbank City Council and Yarra City Council identified the need for more proactive compliance activities and have indicated that it is an area of high priority, including increasing resources for these activities.

Recommendations

-

The Department of Planning and Community Development, assisted by the Environment Protection Authority and in consultation with councils, should:

-

undertake a systematic and coordinated review of the entire regulatory framework for the management of potentially contaminated and contaminated sites to improve clarity and address gaps, including:

- the wording, application and use of the Environmental Audit Overlay

- the application of the framework for planning permits and planning scheme amendments, and the types of use to which it applies

- the use, content, guidance material and peer review of environmental site assessments

- establishing mandatory reporting requirements

- establish processes to capture information about framework and system issues, and processes to address issues in a timely way

- establish a performance framework to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the contaminated sites framework and system.

-

undertake a systematic and coordinated review of the entire regulatory framework for the management of potentially contaminated and contaminated sites to improve clarity and address gaps, including:

-

The Department of Planning and Community Development should:

- assume responsibility and accountability for the leadership, coordination and oversight of the contaminated sites framework

- establish mechanisms and processes to improve the leadership, coordination, oversight and accountability of, and for, the contaminated sites framework and system

- clarify and communicate responsibilities within the framework so that they are clear and understood.

-

The

Environment Protection Authority should:

- develop mechanisms and processes that enable the identification and recording of contaminated land

- assess the risks of these sites

- prioritise high-risk sites and actions to manage the associated risks.

-

Councils,

with the support of the Department of Planning and Community Development,

should:

- develop systems to capture ongoing site conditions to inform their compliance monitoring activities around the development, management and clean-up of contaminated sites

- develop compliance monitoring programs and enforcement processes, consistent with better practice, and perform these activities on a routine basis

- assess the level of expertise and financial resources required to accurately manage and clean up high-risk sites.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report, or relevant extracts from the report, was provided to the Department of Planning and Community Development, the Environment Protection Authority, Brimbank, Maribyrnong and Yarra city councils, and the Department of Sustainability and Environment with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments, however, are included in Appendix B.

1. Background

1.1 Contaminated sites

Contaminated sites are land, and in most instances groundwater, where chemical and metal concentrations exceed those specified in policies and regulations.

Contamination in Victoria has generally been caused by management practices of earlier generations when environmental regulations were less onerous on polluting activities than is the case now. Common sources of contamination include industrial activities, such as the manufacture of munitions or batteries, mining, chemical storage, landfills, petrol stations and agricultural activities.

Typically, there are three ways in which contamination may affect sites:

- contaminants attach to, or are contained within, the soil

- contaminants leach from the soil into surface or ground waters, which may be static, or migrating onto or off the site

- airborne contaminated gases emanating from contaminants in the soil and groundwater.

1.1.1 Risks from contaminated sites

Depending on the nature and extent of the contamination, and how the site is used, contaminated sites may pose imminent or long-term risks to human health, and the environment.

Sites that pose an imminent risk have concentrations of contaminants that require immediate attention to prevent danger to human health or the environment. Sites that pose a long-term risk have levels of contaminants where exposure over a long period of time is known to result in a risk to human health or the environment.

Human health risks

Human health risks range from minor health problems, such as allergic reactions and hypersensitivity, to serious health problems, such as cancer, respiratory illness, reproductive problems and birth defects. For example, the health risks identified from the high levels of lead contamination at the Ardeer Battery site included potential detrimental impacts on human organs and organ systems.

The risks largely depend on the contaminant and its concentration, the exposure pathway, the level of exposure, and the vulnerability of the exposed population.

Human health risks are more likely to occur where there is a high risk that people will come into contact with contaminants in the soil, groundwater or the vapours these contaminants generate. Ministerial Direction No.1 for Potentially Contaminated Land (MDN-1) has identified that the highest risk of this occurring is with uses of the land identified as sensitive. These include residential use, child care centres, pre-school centres and primary schools.

Environmental risks

Environmental risks from contaminated sites generally result from contaminants leaching into the soil, ground and surface waters. This can lead to the degradation of soil, water and air quality and impact upon their uses.

Contamination of groundwater can prevent it from being used for drinking, irrigation or stock supplies. Contamination of soil can impact upon plant growth, reducing crops and leading to erosion. In other cases, contamination can result in odours making recreational areas unusable, or even affecting the way a place looks by degrading the aesthetic values of an area.

1.1.2 Location and number of contaminated sites

The location and number of contaminated sites in Victoria is not accurately known, as this information is not routinely collated. The most recent desktop assessment, reported in a 1997 ANZAC Fellowship Report for the then Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, estimated there were around 10 000 contaminated sites in Victoria based on limited industrial site history information.

The location of potentially contaminated and contaminated sites varies, and includes metropolitan, regional and rural areas. Since previous industrial activity is a significant source of contamination, the majority of contaminated sites in metropolitan Melbourne are likely to be concentrated in historically industrial municipalities, such as Brimbank, Maribyrnong, Melbourne, Moreland and Yarra.

In regional and rural Victoria, towns and cities historically involved in gold mining and agricultural activities—such as sheep dipping and the unregulated use of pesticides and herbicides—are likely to have significant numbers of contaminated sites.

1.1.3 Types of contaminated sites

There are two main types of contaminated sites—those that are potentially contaminated and those that are known to be contaminated.

Potentially contaminated sites are sites that may be contaminated due to past waste disposal, industrial, agricultural and commercial uses of the land. While the past use of the land is an indicator of potential contamination, confirmation can only be obtained through sampling of the soil, groundwater or air.

Establishing whether land is contaminated typically occurs when there is a change in the land use to a more sensitive use—for example, from industrial to residential use—through the land use planning system.

Known contaminated sites are sites where a preliminary site assessment or an environmental audit has been undertaken, and has identified contamination. Where contamination has been identified, there may be a requirement to clean-up the site, depending on its intended use and the potential human health and environmental risks. Within this category there are developed and undeveloped sites.

Special categories of known contaminated sites are orphan sites and legacy sites. Orphan sites are those where the party responsible for the contamination is unknown, is insolvent or unable to pay the clean-up costs. Legacy sites are those where the party responsible for the contamination is known, or can afford to clean the site. Typically, these are sites contaminated prior to environmental regulation being introduced in the 1970s and are a legacy of poor industrial, agricultural, waste disposal and commercial practices during this period.

1.2 Regulating contaminated sites

Potentially contaminated and contaminated sites are regulated through a framework that encompasses the Planning and Environment Act 1987 (P&E Act), the Environment Protection Act 1970 (EP Act), and a range of complementary policies, directions and practice notes, and an environmental audit system.

1.2.1 Planning and Environment Act 1987

The provisions of the P&E Act provide the principal mechanisms by which Victoria's broader planning objectives are achieved. Under the P&E Act, councils and the Department of Planning and Community Development (DPCD), on behalf of the Planning Minister, act as:

- responsible authorities—making decisions on planning permit applications, which permit certain land uses or developments

- planning authorities—preparing planning scheme amendments, which zone large areas of land to allow for its redevelopment for a different use, such as from an industrial zone to a residential zone.

DPCD also makes recommendations for the approval of planning scheme amendments for the Minister for Planning's consideration.

Sections 12(2) (b) and 60(1) (e) of the P&E Act require a planning authority, when preparing an amendment to the planning scheme, or a responsible authority, when deciding on a planning permit application, to take into account any significant effects that the amendment or permit might have on the environment or the environment might have on the use or development. This includes site contamination issues.

State Planning Policy Framework

The State Planning Policy Framework (SPPF) comprises general principles for land use and development in Victoria, and details the state's policies for key land use and development activities including settlement, environment, housing, economic development, infrastructure, and particular uses and development. Planning and responsible authorities are required to take account of, and give effect to, the principles and policies contained in the SPPF so that there is integrated decision-making.

Clause 15.06 of the SPPF under the Victoria Planning Provisions refers to soil contamination and the need for potentially contaminated sites to be suitable for their intended future uses and developments, and that contaminated sites are used safely.

The SPFF also requires responsible authorities, when considering permit applications for use of sites known to have been used for industry, mining or storage of chemicals or gas or liquid fuels, to request adequate information from planning applicants on the potential for contamination to have adverse effects on future site uses.

Ministerial Direction No.1 for Potentially Contaminated Land

MDN-1 applies to the rezoning of potentially contaminated land for a sensitive use. MDN-1 defines a sensitive use as:

- residential properties

- child care centres

- pre-school centres

- primary schools

- agriculture or public open space.

Where planning authorities are preparing an amendment that allows a potentially contaminated site to be used for a sensitive use, the planning authority must satisfy itself that the environmental conditions of that site are, or will be, suitable for that use.

To meet the obligations of MDN-1, planning authorities must undertake an environmental audit consistent with the requirements established under section 53X of the EP Act. The environmental audit requirement only applies to residential properties, child care and pre-school centres, and primary schools.

Environmental Audit Overlay

The Environmental Audit Overlay (EAO) is a mechanism that planning and responsible authorities use to gain assurance that land is suitable for a use that may be adversely affected by contamination. The EAO requires that before a sensitive use commences, or before the construction or carrying out of buildings and works in association with a sensitive use commences on a site, the proponent provides this assurance through the environmental audit system.

Potentially Contaminated Land: General Practice Note

Potentially Contaminated Land: General Practice Note provides guidance to planning authorities in identifying and managing potentially contaminated and contaminated sites, in the context of the planning process. The Practice Note was developed to address both potentially contaminated and contaminated site issues for planning permit applications, and to clarify the appropriate level of assessment for permits and scheme amendments associated with contamination issues. It also addresses issues around when to, or when not to, apply the EAO.

1.2.2 Environment Protection Act 1970

The EP Act is Victoria's primary environment protection legislation, with a basic philosophy of preventing pollution and environmental damage by setting environmental quality objectives and establishing programs to meet them.

The EP Act also provides for the statutory appointment of environmental auditors and outlines their responsibilities so that environmental audits of contaminated sites are conducted in accordance with the Environment Protection Authority (EPA) requirements.

The environmental audit system

The EPA administers the environmental audit system, which includes the appointment of environmental auditors to the EPA Contaminated Sites Auditor Panel and the review of audits undertaken.

An environmental audit assesses the nature and extent of harm, or the risk of harm, to the environment posed by an industrial process or activity, waste, substance or noise. Planning and responsible authorities, government agencies and the private sector use the system to provide assurance that potentially contaminated and contaminated sites are suitable for their intended use, or to advise what is required to make a site suitable for its intended use.

Environmental audits must follow relevant EPA environmental audit guidelines and standards, and undertake sampling and analysis of soil, and possibly groundwater, surface water and air. They are conducted by auditors who must demonstrate expertise and extensive experience in contaminated land matters, plus an understanding of the EP Act and associated statutory policies, regulations and guidelines, in order to provide the best assurance available that the site is suitable for its intended use.

Environmental audits result in either a certificate or a statement of environmental audit:

- a certificate is issued for a site when the environmental condition of the land is suitable for any use; it is essentially a clean bill of health for the site

- a statement is issued where, following an audit, an environmental auditor is of the opinion that the land is not suitable for all possible uses, but is suitable for a specific use or development.

A statement of environmental audit may contain conditions relating to the development or ongoing management of the site so that contamination does not adversely impact the use, the users or the environment.

Environmental site assessments

Environmental assessments complement environmental audits, although they are not governed by the EP Act. Environmental assessments are completed by environmental consultants or professionals, and may include anything from a desktop review of the site, to a full site history and soil, groundwater and air sampling and analysis.

The rigour of the site assessment is dependent on the assessor, as there is no certification or established guidelines as to what a site assessment should contain. The National Environment Protection Measure defines a site assessment as a review to determine whether site contamination poses an actual or potential risk to human health and the environment, either on or off the site, to the current or proposed land use. The National Environment Protection Measure sets out recommended processes to undertake site assessments for contamination including preliminary site assessments and risk assessments, however, they are recommended processes and assessors may undertake the assessments differently.

State Environment Protection Policy—Prevention and Management of Contamination of Land

The State Environment Protection Policy—Prevention and Management of Contamination of Land links EPA's environmental audit system and the land use planning system under the P&E Act. The policy provides a statutory framework for protecting people and the environment from the effects of land contamination.

The policy sets in place measures to prevent and manage contamination. It reinforces the requirement of an audit, where a potentially contaminated site may be used for a sensitive use, irrespective of whether the planning decision relates to a planning permit or a planning scheme amendment. It identifies mechanisms so that conditions attached to statements of environmental audit are met.

Figure 1A underscores the complexity of the contaminated sites regulatory framework. It includes the relevant entities, the regulatory instruments for potentially contaminated and contaminated sites, and the situations to which they apply.

Figure

1A

Contaminated sites regulatory system

Note: Dashed coloured lines indicate that the regulatory instrument may apply. Solid colour lines indicate that the instruments do apply. Dark blue lines apply to planning scheme amendments and light blue lines apply to planning permits.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.3 Managing contaminated sites

Councils, the EPA and DPCD are the key public sector entities responsible for the management of contaminated sites. Private sector environmental auditors and suitably qualified personnel support them in this role.

Councils

Councils, as planning and responsible authorities, are responsible for regulating the planning and development of potentially contaminated and contaminated sites in accordance with the P&E Act. In addition, councils are responsible for managing and developing council owned and managed sites so that they do not result in unacceptable risks to the environment or human health as a result of contamination.

Department of Planning and Community Development

DPCD's main role is to support the ongoing effective operation of the state's planning system. It has two overarching responsibilities that are central to this function:

- monitoring and improving the overall performance of the state's planning system

- providing key statewide planning services essential for maintaining and supporting the effective operation of the system.

To meet its responsibilities, DPCD provides a number of services. These include:

- managing the ongoing development and maintenance of the P&E Act and associated regulations

- managing the Victoria Planning Provisions

- processing amendments to planning schemes

- providing advisory and statutory support services to councils and stakeholders

- supporting the Minister for Planning's role as a planning and responsible authority.

Environment Protection Authority

The EPA is responsible for regulating known contaminated sites under the EP Act. These sites are considered incompatible with their current or approved use without active management to reduce the risk to human health and the environment. It does this through a number of mechanisms:

- developing, administering and managing the audit system, including the appointment of environmental auditors

- investigating contamination in all sites that come to its attention, to determine if further action is required

- issuing and administering clean-up and pollution abatement notices so that these sites are cleaned up to an appropriate level

- developing and administering the Priority Sites Register—a register of known contaminated sites that have been issued with a clean-up notice or pollution abatement notice

- registering and recording a list of all completed environmental audits on its website

- administering the Contaminated Sites Fund—a fund for the management and clean-up of high-risk contaminated sites.

1.4 Audit objective and scope

The audit examined how contaminated and potentially contaminated sites were managed, particularly where a sensitive use of the land is involved.

The audit reviewed the activities of DPCD, the EPA, Brimbank City Council, Maribyrnong City Council and Yarra City Council.

1.4.1 Audit approach

The audit examined whether:

- contaminated sites are managed in accordance with the regulatory framework, as outlined in the provisions of the P&E Act and the EP Act.

- environmental audits are conducted in accordance with the EPA's environmental audit system, and reviewed in a timely manner by appropriately qualified people

- risk-based monitoring of compliance occurs, followed by appropriate enforcement action for non-compliance.

The audit was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. The total cost of this audit was $390 000.

2. The contaminated sites regulatory framework

At a glance

Background

Recognising the need to manage risks associated with contaminated sites, successive governments have developed a range of regulatory tools with the key objective of protecting human health and the environment.

Conclusion

There are significant gaps and lack of clarity in the regulatory framework for contaminated sites. Accordingly, there is little assurance available that risks to human health and the environment are being managed effectively.

Findings

- A regulatory framework has been in operation for contaminated sites since the late 1980s.

- Lack of clarity and gaps in relation to identification, management, clean-up and reporting have resulted in different interpretations and inconsistent application of the framework by key authorities and agencies; and at times inaction to address known health or environmental risks.

- Issues associated with the framework have been known to the Department of Planning and Community Development (DPCD) and the Environment Protection Authority (EPA) since between 2000 and 2005, however, only some are now being addressed.

- Past efforts to address weaknesses in the framework have been ad hoc, and continue to be addressed in isolation from one another, rather than through a systematic review.

Recommendation

DPCD, assisted by the EPA and in consultation with councils, should:

- undertake a systematic and coordinated review of the entire regulatory framework for the management of potentially contaminated and contaminated sites to improve clarity and address gaps

- establish processes to capture information about framework and system issues, and processes to address issues in a timely way

- establish a performance framework to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the contaminated sites framework.

2.1 Introduction

Victoria's industrial and manufacturing heritage, combined with lower environmental standards for much of the last century, mean that parts of metropolitan Melbourne are contaminated. This is particularly so for suburbs in the inner east, north and west.

Improved environmental standards since the 1970s, and changing demography, increase the pressure to clean up these sites so they can be redeveloped, and to protect the environment. Recognising the need to manage potential human health and environmental risks, successive governments have developed a range of regulatory tools for contaminated sites. Development of specific planning and regulatory instruments started in 1989, in response to concerns with residential developments occurring on contaminated land.

The regulatory framework addresses sites that are potentially contaminated or contaminated, with planning and responsible authorities mainly applying it to sites being redeveloped for sensitive uses. As such, the contamination status of land is assessed only if there is an interest in redeveloping or changing a site's use. The framework applies also to known contaminated sites that the Environment Protection Authority (EPA) has identified, either through its own monitoring activities or notification.

The framework consists of two Acts—the Planning and Environment Act 1987 (P&E Act) and the Environment Protection Act 1970—that are supported by a range of specific planning and regulatory instruments:

- the State Planning Policy Framework—contaminated soils

- Ministerial Direction No.1 for Potentially Contaminated Land (MDN-1)

- an Environment Audit Overlay (EAO)

- Potentially Contaminated Land: General Practice Note (the Practice Note)

- a State Environment Protection Policy—Management of Potentially Contaminated Land

- the Environmental Audit System.

The protection of human health and the environment is a key objective of Victoria's regulatory framework for contaminated sites.

2.2 Conclusion

Elements of the regulatory framework, including the key planning concept of 'sensitive use', the environmental audit overlay and its application, and audits and site assessments, are unclear. In addition, significant gaps exist in the planning and development instruments used to identify and manage potentially contaminated sites, and the legislation as it relates to the management, reporting and clean-up of existing contaminated sites.

This provides little assurance that the framework's key objective is being met. Inaction resulting from known gaps has increased the risk of human health being adversely affected and the probability of environmental damage occurring.

The complexity and lack of clarity of the framework has led directly to divergent interpretations across councils and the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT)—an avenue of appeal for planning decisions. Between 2002 and 2010, we identified 25 cases heard by VCAT that highlighted issues with the planning system as it relates to potentially contaminated sites, including:

- questions of interpretation about regulatory instruments as they relate to planning applications

- how regulatory instruments should be applied in planning situations

- roles and responsibilities of EPA

- calling for a review or redrafting of the EAO.

Planning and responsible authorities also need to rely heavily on legal advice to clarify issues relating to the framework, including the use of the framework's tools, their interplay, roles and responsibilities, and liabilities under the framework. Adding to the complexity is council legal advice that conflicts with VCAT interpretations.

The known gaps and a lack of clarity within the regulatory framework, which were identified between 2002 and 2005, persist and the little action taken to address them has been ineffective.

2.3 Clarity and complexity of the framework

The framework's regulatory instruments, established and refined over a 20-year period, have been developed separately and implemented on an ad hoc basis by the EPA and the Department of Planning and Community Development (DPCD) to resolve specific issues or improve clarity.

In several situations, the instruments and their interplay have made the framework unnecessarily complex and unclear. This is particularly so for the EAO, MDN-1 and the Practice Note in relation to the requirements for, and guidance around, environmental audits and assessments.

Environmental Audit Overlay

An overlay applies further planning provisions to a site or area to address a single issue or a related set of issues. An EAO is typically applied to potentially contaminated or contaminated sites, which means an environmental audit is required before any use, construction or building works start.

There are a range of issues associated with the EAO, its application and the tools developed under the framework to provide guidance.

The framework states that the EAO should be applied only after a planning authority has identified whether land is potentially contaminated prior to, or at the time of rezoning. The EAO and the Practice Note are unclear as to how planning authorities identify that the land is contaminated. This lack of clarity has resulted in a range of issues associated with the use of the EAO, including uncertainty about:

- the type of assessment required prior to applying the EAO

- how to apply the EAO—for example, site by site, or on a precinct basis

- whether to apply the EAO or use another tool

- if and when to remove the EAO.

As a consequence, none of the audited agencies have adequately assessed known industrial, and other, potentially contaminated sites available for residential development to inform its decisions about applying an EAO. In addition, each agency interprets and applies the EAO differently, resulting in different outcomes for the same or similar issues.

Ambiguous wording of the EAO in relation to whether it applies to new uses or new and existing uses and the definition of buildings and works, combined with a lack of discretion once it is applied, has caused an increased regulatory burden and substantial costs to proponents—not commensurate with the risks associated with the works and use. Any works, including minor redevelopment works, which are proposed to an existing building where an EAO applies, require an audit. Environmental audits can range in cost from $10 000 to $30 000 for small, uncomplicated sites. Figure 2A provides examples of EAO application.

Figure

2A

Application of the Environmental Audit Overlay

Yarra City Council applies the EAO over large areas containing numerous sites, possibly covering sites that are not contaminated. Applying the EAO in this way subjects any site within the area to an audit, irrespective of the type of works and their potential to disrupt the soil or groundwater. This has resulted in situations where Yarra City Council requires an audit in areas that are shown to have only ever been used for residential purposes, and/or where works result in no disruption to the soil—for example, upper level works to a second storey house.

Brimbank and Maribyrnong City Councils apply the EAO on a site by site basis, but not consistently for similar planning issues.

DPCD did not apply the EAO over the Docklands area, as they submitted it may result in a decrease in the market value of the land.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The inconsistent way the agencies included in this audit apply the EAO provides little assurance that, where potentially contaminated sites are used for sensitive uses, the risks to human health and the environment are adequately managed. There is also little assurance that planning authorities are applying the EAO in accordance with the framework's requirements.

Environmental audits and assessments

Environmental audits and assessments are key elements of the regulatory framework. They provide planning and responsible authorities with information on whether, and to what extent, a site is contaminated to inform decisions about the redevelopment of a site.

Audits

The regulatory framework is clear that an environmental audit by an EPA appointed auditor must be undertaken for a planning scheme amendment where there is a change in zoning to allow sensitive uses. Planning and responsible authorities rely on the integrity of the EPA's auditor appointment system and review processes to provide assurance that the audit and auditor has complied with relevant legislation, standards and guidelines and formed appropriate conclusions and recommendations in issuing either a certificate or statement of audit.

However, there is less clarity around the timing of an audit during the planning process. Under MDN-1, planning authorities can approve a delay in undertaking an audit 'under difficult or inappropriate circumstances'. It is unclear what is meant by 'difficult' or 'inappropriate'.

In practice, certificates or statements of audit are not required before planning authorities approve an amendment. The lack of clarity around the timing diminishes transparency around decisions to delay audits, and creates difficulty in determining whether the decision was based on genuine difficult or inappropriate circumstances, or due to pressure that applicants apply due to the holding costs associated with proposed developments.

It also results in limited assurance that the land is suitable for the intended use even though planning approval has been given. This can lead to the poor management of risks to human health and the environment posed by these sites during their development process and can prove costly for developers who have not factored in the required clean-up costs.

Planning and responsible authorities stated that it is difficult, or unreasonable, to request an audit of a planning applicant or developer in the majority of cases prior to giving approval, due to the costs associated with undertaking an audit where no planning assurance can be given that the development will be allowed to proceed. This approach indicates that planning and responsible authorities define potential costs for applicants as 'difficult' or 'inappropriate' when it comes to environmental audits.

Site assessments

There is a lack of clarity and guidance under the framework about whether a site assessment or an audit is required for planning permit applications, and for uses other than those defined as sensitive under MDN-1 for planning scheme amendments. This is significant, because the approach chosen can lead to quite different outcomes given varying levels of rigour in the different assessment options.

Site assessments ranged from a simple desktop site planning history assessment, to a more rigorous assessment including soil and groundwater testing and a detailed site history assessment of past use—leading to varied levels of assurance about the past history and contamination status of the site.

If an assessment is undertaken, there is a lack of clarity and guidance about what form of site assessment a planning or responsible authority should require the applicant to undertake.

Determining whether an assessment is technically adequate rests with the planning or responsible authority. These authorities do not generally have the technical capacity to assess the complex technical issues associated with contaminated sites. This differs from audits, where the expertise and responsibility rests with the auditor.

Under the framework, peer reviews of site assessments by qualified environment professionals are recommended 'where appropriate' to assist planning and responsible authorities to assure themselves of the technical adequacy of a site assessment. However, the framework is unclear about what 'appropriate' is. Site assessments were peer reviewed in an ad hoc and inconsistent manner by the responsible authorities. Given the lack of technical expertise and the ambiguity around what is 'appropriate', it is likely that deficient assessments will not be identified or reviewed.

Sensitive uses

The fundamental objective of the regulatory framework is the protection of human health. Central to this objective is the definition of 'sensitive use' in the planning tools in the framework, which recognises the risk that any contamination will adversely impact upon a use that has been identified as sensitive, including the people associated with the use. Generally, an audit is required for any planning application where there is a change to a sensitive use. This provides assurance that the use of the site will not pose a health risk to any person, particularly children, who uses or comes into contact with the site.

However, little assurance can be given that the framework is achieving its objective of the protection of human health, as the definition of a sensitive use under the framework is narrow and does not address a range of uses that pose a health risk where contamination of the land may be present.

MDN-1 defines 'sensitive use' as residential use, a child care centre, a pre-school centre or a primary school. For these situations, an environmental audit is required to assess the contamination and determine subsequent action in order to protect children who use the site as a result of the development.

Alongside the defined sensitive uses, MDN-1 also identifies public open space and agriculture as uses that planning authorities must 'deliberately satisfy themselves that the environmental conditions of the land are suitable for those uses'. It does not provide guidance to planning authorities on how this should be done.

Adding to the lack of clarity around the issue of sensitive uses, the Practice Note states that an environmental site assessment is required for public open spaces and agricultural uses if there is insufficient information available to determine whether an audit is required. None of the guidance identifies what is sufficient information.

Non-defined sensitive uses

The regulatory framework does not adequately address the issue where the proposed change in land use is to a non-sensitive use, as defined under the framework, but where there are still potential health and environmental risks associated with the use if contamination is present.

The Practice Note indicates that if the potential for contamination of a site is low to medium where the proposed use is a non-sensitive use, such as a worship centre, playground, open space or retail office, then an environmental audit or assessment is not required. Rather, actions to address potential contamination default back to provisions within the P&E Act, which require planning and responsible authorities to consider the effect of the development on the environment or the effect of the environment on the development.

Human health risks have been identified as a result of vapour intrusion caused by volatile organic compounds, soil contamination and groundwater, which can impact upon the health of users of non-sensitive uses. There is no obvious trigger under the framework that requires an assessment of the contamination status of a site subject to a planning scheme amendment or planning permit application involving a non-sensitive use. However, it is equally as important to consider the hazards of intrusive subsurface vapours that might impact the health of occupants inside a secondary school, worship centre or industrial factory, as would be the case for occupants of a residential building or a primary school.

Planning and responsible authorities have identified a range of issues associated with the narrow definition of a sensitive use as defined under the framework, and have adopted their own approaches to address these issues. Figure 2B highlights these.

Figure

2B

Approaches to managing gaps in the framework associated with

the narrow definition of sensitive use

Yarra City Council applies the EAO across not only zones allowing sensitive uses, but also zones previously zoned industrial or that allow mixed uses, to provide assurance that health risks are assessed through an audit.

Maribyrnong City Council's local policy for managing contaminated sites applies to both sensitive and non-sensitive uses.

Brimbank City Council requires an environmental audit where playgrounds are part of an application, which is not a defined sensitive use under MDN-1.

DPCD requires an audit for any application that has an educational centre or informal outdoor recreation in the Docklands area.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

2.4 Gaps in the framework

In addition to the complexities and issues with the framework, there are a range of gaps in the framework—many of which have been known to DPCD and the EPA since at least 2000—that have affected the operation of the framework.

Ministerial Direction No.1 for Potentially Contaminated Land

In some cases, sites that are contaminated or potentially contaminated are not identified before redevelopment or use. MDN-1 only applies to planning scheme amendments to allow for change to a new sensitive use planning zone. This means it only takes effect when there is a change to planning zones from a non-sensitive use, such as industrial, to a sensitive use, such as residential.

MDN-1 does not apply to potentially contaminated land that is already zoned to allow for a sensitive use, such as residential land with current industrial uses. This land still meets the definition of 'potentially contaminated land' under MDN-1, but is not captured in the 'requirement for an audit' if the amendment is not considered to allow a sensitive use to occur for the first time. It also does not apply to planning permit applications associated with a sensitive use, and as a consequence it does not capture the redevelopment of sites where the contamination status of the land may not be suitable for the proposed sensitive use. This is because there is no specific requirement for an audit to be undertaken.

Figure

2C

Case study 4—Department of Planning and Community Development

A planning permit was required for a new high density residential development in inner Melbourne. A site assessment was completed, which indicated that the condition of the land would not pose a risk to residents and, therefore, an audit was not required. The EPA recommended the assessment be peer reviewed. However, the responsible authority chose not to follow the recommendation, and works started on the redevelopment.

Upon demolition, the site was found to be heavily contaminated. An EPA review of the assessment found it was inadequate, and ordered that an audit be undertaken to assess the suitability of the site for the intended use.

The trigger to require either an audit or assessment for a sensitive use associated with a planning permit application is unclear under the framework, leading to situations such as this. Exacerbating the issues in this case is that planning approval was issued before a site assessment or audit was undertaken. It is now unclear whether this site is appropriate for its intended use, even though approval was given and works started.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In the absence of a coordinated effort to address gaps around the framework, and particularly MDN-1, councils have developed specific actions to meet the objectives of the P&E Act. These include Maribyrnong City Council's local policy for contaminated sites, Yarra City Council's application of the EAO over all potentially contaminated sites, which effects both planning scheme amendments and planning permits, and Brimbank City Council's legal advice framework to support decision-making around both amendment and permits associated with potentially contaminated land.

While the councils audited have shown initiative to address the gaps in MDN-1 and others under the regulatory framework, the lack of a systematic, coordinated statewide solution has resulted in varying planning outcomes, regulatory overburden and, at times, significant costs to both council and the proponent not commensurate with the risks posed by the development.

Neither MDN-1, nor any other regulatory instrument under the framework applies to potentially contaminated sites that were zoned to allow a sensitive use before 1989. While the requirements of the Environment Protection Act 1970 apply where there is reason to suspect potential contamination, there is no obvious requirement within the planning tools under the framework for either an audit or site assessment for a redevelopment within a zone that already allows for sensitive use, even though the site has never been assessed for contamination issues. This creates the situation where potential risks to human health, associated with sensitive uses built on contaminated land before 1989, are not being addressed.

Community use sites

A range of community use sites available to the public do not fall under the framework's definition of a sensitive use, which triggers the need for an audit or site assessment to address contamination issues. Types of community use sites that do not fall within the definition include playgrounds, secondary schools and open space, even though those using them are likely to include children—the very group sensitive use processes are designed to protect.

These community use sites can expose people to contaminants or vapours that can result in significant health risks—not any less serious than those from the sensitive uses defined under the framework. For example, a school may be built on contaminated land where vapours from the contaminants may pose a risk to students' health due to long-term exposure. One council audited is currently monitoring vapour levels within a school from neighbouring contaminated land to assess any health risks posed.

There is also no provision within the framework requiring councils to test for contamination at pre-existing community use sites that come within the definition, such as childcare and kindergarten centres that are not currently undergoing redevelopment or licence renewal.

All councils audited identified a duty of care and a due diligence process for existing children's services, but action to address this risk varied from extensive to little or no action, as shown in Figure 2D.

Figure

2D

Due diligence process applied by councils to community use sites

Yarra City Council implemented a rigorous process and policy for all community use sites, including child care centres and playgrounds, supported by active community engagement. It has also adopted a broader definition of sensitive use than that in the framework, to include playgrounds and open space—areas that may involve sensitive uses.

Maribyrnong City Council has undertaken soil testing at its child care centres, and where risks are identified is managing these as a priority. It has also adopted a broader definition of sensitive use than that used in the framework. Maribyrnong City Council has not assessed any other community based sites.

Brimbank City Council has met the requirements under the Department of Health guidelines for soil testing for new child care centres or where there is a proposal to alter or extend an existing centre, but has not undertaken a soil or site assessment for all its child care centres or community use sites. It applies the sensitive use definition included in the framework.

DPCD has included the requirement to undertake an audit for an educational centre or informal outdoor recreation area in the Docklands Planning Scheme.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Building and occupancy permits

While the Building Act 1983 and the Building Commission's practice notes oblige building surveyors to satisfy themselves that all requirements of the planning scheme are met prior to issuing a building or occupancy permit, it is unclear when, how and to what extent they must inform themselves about the status of land with respect to contamination before issuing a certificate of occupancy.

Legal advice to Maribyrnong City Council identified this as an issue, and recommended that councils should educate building surveyors on these issues. Other councils have not identified this as an issue and Maribyrnong City Council is yet to follow up on its legal advice.

Ministerial exemptions

The Minister for Education and the Minister for Health are exempt from the planning framework requirements under the P&E Act. This means that they are not required to adhere to the provisions and instruments associated with the P&E Act for contaminated land, even though they may own or manage land used for a sensitive use. This exemption dates back to the early 1980s when the complexity of issues surrounding the development and use contaminated sites were not known or understood.

Mandatory reporting

There are known contaminated sites currently used for a sensitive use (residential), or used by the public (playgrounds and public open space), which pose or potentially pose a risk to human health or the environment.

Not all of these known sites are recorded on the EPA's priority sites register—a register of contaminated sites that the EPA knows about, and has issued clean-up or pollution abatement notices for—and, as such, the community is unaware of the sites' contamination status. This is because there is no requirement for owners, managers, councils or developers to report this to any agency or notify the community—even if the sites pose an imminent human health or environmental risk.

Without the EPA being aware of these sites, it is unable to make an assessment as to whether a clean-up notice is required and, therefore, inclusion on the priority sites register. However, even if the EPA was notified, but the risk was considered long-term rather than imminent, there is no clear requirement under the framework for these sites to be cleaned up or to allocate responsibility for their management.

This is a significant gap, and one that could result in immediate and long-term harm to both human health and the environment through allowable inaction. Figure 2E provides examples of known contaminated sites not reported, and not on any public register.

Figure 2E

Examples of unreported, known contaminated sites

Case study 1 of 5

Site A is a residential area within the City of Maribyrnong. It includes 22 properties that are known to be built on contaminated land. Maribyrnong City Council first identified the contamination in 1994, but did not report it to the EPA until 1998. Furthermore, 12 of these properties pose a potential health risk to children as contaminant levels exceeded recommended criteria, and a further four pose an actual risk due to children residing at these properties. The remaining six properties are potentially contaminated, with potential health risks.

Case study 2 of 5

Site B is a public use/open space site in the City of Yarra. It is adjacent to the Yarra River and adjoins an uncontaminated council owned reserve used for public open space with a BBQ and picnic tables. The Department of Sustainability and Environment manages the site on behalf of the Crown.

An assessment in 2004 rated the potential for site contamination as very high. This rating was based on the previous industrial land use of the site, and visual inspection of exposed topsoil at one location on the site. The inspection found debris and fill material, and soil colour that indicated the possible presence of contamination by heavy metals and hydrocarbons.

Case study 5 of 5

Site E is a former quarry site and now a reserve in the City of Maribyrnong. The site is known to be contaminated due to the past quarrying history, resulting in soil contamination and vapours. The site now includes two recreation centres and grassed open areas with public seating. One of the recreation centres is used by older people, while the other is used for outside school hours care. Residential properties abut the reserve, including two neighbouring properties located over the old quarry footprint.

The status of the site's contamination is only known to the Maribyrnong City Council. There has been no communication with property owners whose houses are located on the footprint of the old quarry, or surrounding residents. As there are no mandatory reporting requirements, Maribyrnong City Council is not required to report the site to the EPA or any other agency.

Note:Appendix A contains further information on the five case studies detailed in this report.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In 2007, the EPA estimated that another 10 to 20 instances like Case Study 1 exist across metropolitan Melbourne, where residential properties were built on old private quarries or landfills. These sites have not been further identified, assessed or cleaned up.

Site transactions

Property and title laws do not require the recording of the status of the site in terms of contamination on the title when selling a site, even if contamination is known. This further contributes to the difficulty of obtaining information for prospective buyers around the site status. There is no mechanism in place to inform owners and occupiers of the contamination status of the site following a change of ownership or change of tenant, except via a section 32 notice, which identifies whether an audit of the site has been undertaken.

2.5 Actions to address gaps in the framework

Timely reviews of the effectiveness of regulatory instruments are critical for providing regulators with assurance that the intended objectives are being met. Reviews also provide opportunities to make necessary changes.

Despite DPCD and the EPA knowing since at least 2000 that there were weaknesses with the regulatory framework, there has only been action to address the significant gaps and issues in the framework since late 2010. A number of reviews have now commenced or are planned.

While these reviews are a positive initiative, they are being planned in an ad hoc manner and occurring in isolation of one another. This further demonstrates the need for leadership and for greater coordination across the system.

2.5.1 The Department of Planning and Community Development review of planning tools

The Minister for Planning appointed a Ministerial Advisory Committee in March 2011 to examine the existing planning controls and processes for potentially contaminated sites and make recommendations as appropriate to:

- update and clarify the planning processes and guidelines pertaining to planning for potentially contaminated sites

- amend the planning controls by incorporating greater flexibility to better reflect the intent of the regulatory environmental audit system

- address any other matter that the advisory committee considers will improve planning outcomes.

An issues and options paper was released for comment in September 2011. This paper identified a range of issues similar to those identified in this report, as they relate to the planning tools for potentially contaminated sites—specifically the EAO, MDN-1 and the concept of 'sensitive use'. A final report is expected to be completed in late 2011 or early 2012.

2.5.2 The Environment Protection Authority review initiatives

The EPA undertook a range of reviews between 2010 and 2011, both directly and indirectly addressing the way it manages known contaminated sites:

- Compliance and Enforcement Review 2010—The review identified a range of issues around how the EPA undertakes its compliance and enforcement activities. All 114 recommendations of the review have been accepted and around 22 of these will have a direct impact on the EPA's management of contaminated sites.

- The EPA's Five-Year Plan 2011–16—The plan identifies objectives, actions and measurable outcomes for the next five years. One of the key actions under the five-year plan is to critically review the EPA's regulatory approach to contaminated sites, including the audit system, tools, procedures, integration with the planning system, and instigation of priority regulatory reforms.

- Internal operational review of contaminated sites management 2011—The review identified 19 key risks associated with the EPA's role and responsibilities, tools, and systems for the management of contaminated sites. It has identified actions where the controls to manage the risks are currently inadequate.

- Review of the State Environment Protection Policy for the Management of Contaminated Land—The Department of Sustainability and Environment and the EPA are jointly undertaking a review of the current function, structure, content, management and effectiveness of statutory policies under the Environment Protection Act 1970, including State Environment Protection Policies. The review itself is not a specific review of the content of the contaminated land State Environment Protection Policies.

No specific time frames or resource plans have been approved for the initiatives relating specifically to contaminated sites.

Recommendation

- The Department of Planning and Community

Development, assisted by the Environment Protection Authority and in

consultation with councils, should:

-

undertake a systematic and coordinated review of

the entire regulatory framework for the management of potentially contaminated

and contaminated sites to improve clarity and address gaps, including:

- the wording, application and use of the Environmental Audit Overlay

- the application of the framework for planning permits and planning scheme amendments, and the types of use to which it applies

- the use, content, guidance material and peer review of environmental site assessments

- establishing mandatory reporting requirements

- establish processes to capture information about framework and system issues, and processes to address issues in a timely way

- establish a performance framework to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the contaminated sites framework and system.

-

undertake a systematic and coordinated review of

the entire regulatory framework for the management of potentially contaminated

and contaminated sites to improve clarity and address gaps, including:

3. Governance of the contaminated sites system

At a glance

Background

Contaminated sites are managed by a range of entities through a complex and incomplete framework. In this system, where the entities are working toward the same objective, there is a need for sound governance.

Conclusion

The governance arrangements for the regulatory framework and the contaminated sites system are undermined by a lack of oversight and accountability for the effective operation of the framework.

Findings

- No entity has taken clear leadership of this area and roles and responsibilities lack clarity.

- No single entity is responsible for overseeing the contaminated sites framework, or for assessing its effectiveness.

- There are a number of known contaminated sites posing a risk to human health, for which no one is responsible, resulting in inaction.

- There is a lack of information across the state on the location, number and status of contaminated sites. As a consequence, there is no assessment of the risk these sites pose, in terms of human health, the environment and costs.

Recommendation

The Department of Planning and Community Development should:

- assume responsibility and accountability for the leadership, coordination and oversight of the contaminated sites framework

- establish mechanisms and processes to improve the leadership, coordination, oversight and accountability of, and for, the contaminated sites framework and system

- clarify and communicate responsibilities under the framework so that they are clear and understood.

3.1 Introduction

Contaminated sites are managed by a number of entities through a complex and incomplete framework. This system, in which multiple entities work toward the same objective, requires sound, coherent governance.

To be effective, the governance arrangements need to be underpinned by clearly understood roles and responsibilities, a clear understanding of the risks, and information on how well the system is performing.

3.2 Conclusion

The governance arrangements are undermined by a lack of oversight and accountability for the effective operation of the framework, and undermined by unclear and unknown roles and responsibilities within the framework.

Because no one has been allocated responsibility, and no one is accountable for addressing these weaknesses, we found cases where little meaningful action had taken place to address known contamination.

The health, environmental and financial risks from contamination are potentially significant. However, the ability to adequately assess and mitigate this risk is hampered by a lack of information on the number and location of contaminated sites, and the nature and extent of contamination. The responsible entities have been neither proactive nor systematic in obtaining this information.

The efficient and effective operation of the framework requires single point accountability in order to oversee its performance in managing the risks associated with potentially contaminated and contaminated sites across Victoria. This includes establishing clear responsibilities for the framework's application, review and performance.

3.3 Oversight and accountability