Tertiary Education and Other Entities: Results of the 2012 Audits

Overview

This report presents the results of our financial audits of 106 entities mainly with a 31 December financial year end. It focuses on technical and further education (TAFE) institutes, universities and alpine resort management boards (ARMBs) and provides detailed analysis of their financial reporting, performance reporting, financial results, financial sustainability and internal controls. It informs Parliament about significant issues arising from the audits and complements the assurance provided through individual audit opinions included in the entities' annual reports.

Clear audit opinions were issued on the financial reports of all

but three entities. The three qualified opinions related to the

financial reports of The University of Melbourne, Deakin University

and the Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria.

Clear opinions were issued on all 20 performance statement

audits.

Overall, internal controls in TAFEs and universities were

adequate for producing reliable, accurate and timely financial

reports. Internal audit functions were well developed, although

four universities and five TAFEs did not have arrangements for

internal auditors to report their conflicts of interests.

Improvements could be made in relation to internal audit coverage,

with a number of key business areas not subject to recent internal

audit scrutiny.

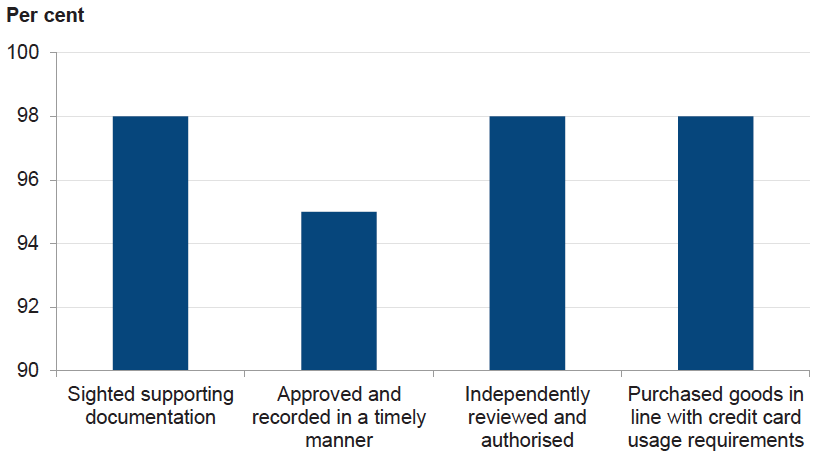

Controls over credit card purchasing were generally sound, however

improvements can be made in relation to risk identification.

Sample-based testing produced positive results, with identified

internal controls operating in a majority of instances.

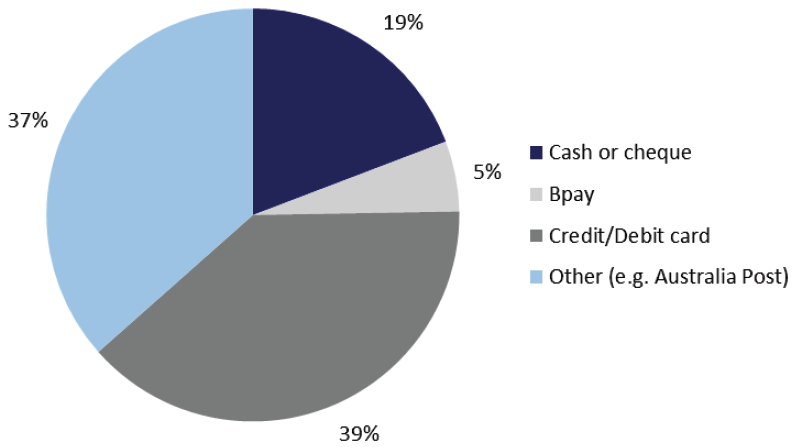

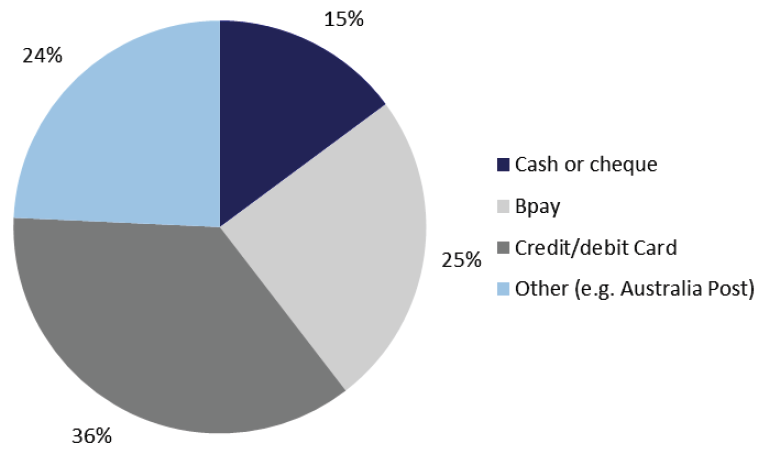

Ten of the 22 tertiary education entities (three universities and

seven TAFEs) had not assessed themselves as being compliant with

the requirements of the Payment Card Industry-Data Security

Standard. This shows a lack of understanding of the importance of

this high-risk activity, and potentially exposes students to risks

of identity theft or fraud if their credit card information is

accessed by unauthorised persons.

Tertiary Education and Other Entities: Results of the 2012 Audits: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER May 2013

PP No 233, Session 2010–13

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Tertiary Education and Other Entities: Results of the 2012 Audits.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

29 May 2013

Audit summary

This report presents the results of our financial audits of 106 entities mainly with a 31 December financial year end. It focuses on technical and further education (TAFE) institutes, universities and alpine resort management boards (ARMB) and provides detailed analysis of their financial reporting, performance reporting, financial results, financial sustainability and internal controls. It informs Parliament about significant issues arising from the audits and complements the assurance provided through individual audit opinions included in the entities' annual reports.

Clear audit opinions were issued on the financial reports of all but three entities. The three qualified opinions related to the financial reports of The University of Melbourne, Deakin University and the Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria.

Clear opinions were issued on all 20 performance statement audits.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding some areas for improvement, Parliament can have confidence in the adequacy of financial and performance reporting and the internal controls of the entities audited.

Performance reporting

The usefulness of current performance information is limited, as there is little consistency in indicators and targets. We intend to provide advice to TAFEs on the relevance and appropriateness of performance indicators in management letters in years ending 31 December 2013 and 2014. In the year ending 31 December 2015 we will express an audit opinion on the relevance and appropriateness of performance indicators.

Financial results and sustainability

TAFEs collectively generated a surplus of $58.5 million in 2012, down 39.1 per cent on 2011 as a result of increased employee costs due to structured redundancy programs. Changes to funding mean that TAFEs are now more reliant on student tuition fees for generating a major portion of their operating revenue. Overall student fee revenue was consistent with 2011, with a $7.1 million decrease in international student fees offset by a $7.7 million increase in domestic student fees.

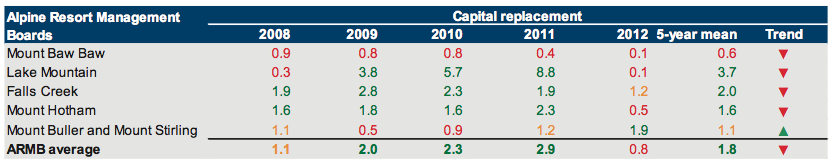

The sector's financial sustainability risk is deteriorating, with 10 of the 14 TAFEs assessed as medium risk in 2012, compared with seven in 2011. TAFEs generally recorded poor self‑financing indicators, which suggests that they are unable to fund asset replacement or renewal with cash generated from their operating activities. Capital replacement indicator results declined at nine of the 14 TAFEs, and there is an increasing dependence on government funding for capital programs.

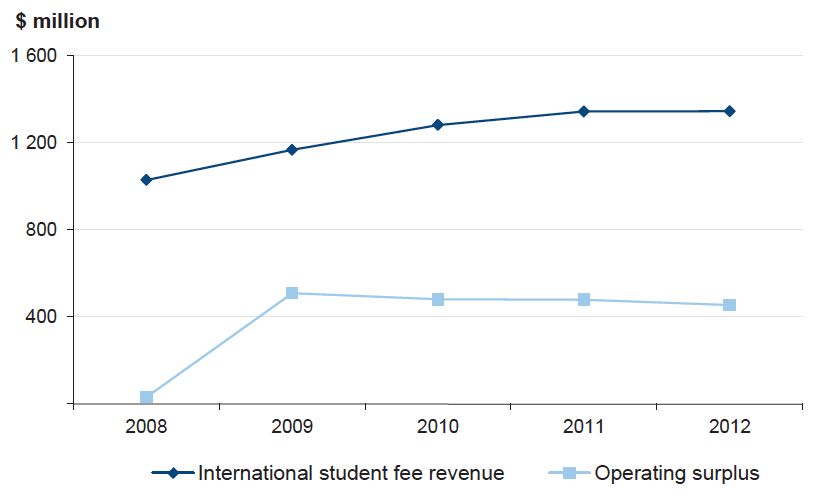

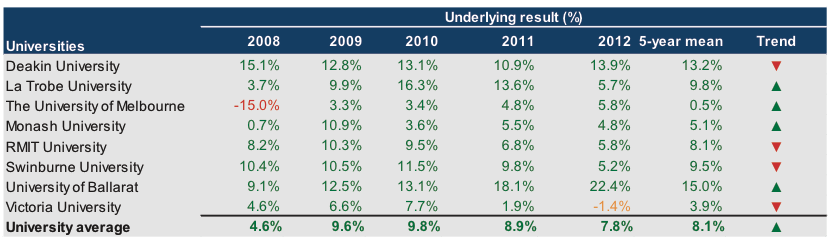

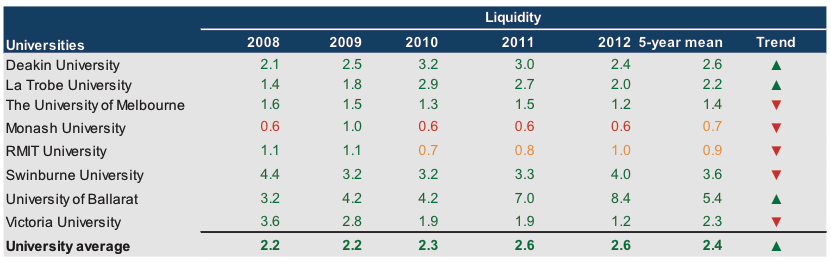

Seven of the eight universities reported a surplus in 2012, with the sector generating a total surplus of $454.6 million, compared to a $478.5 million surplus in 2011. Student fee revenue grew by $107.4 million, mainly due to higher domestic student fees.

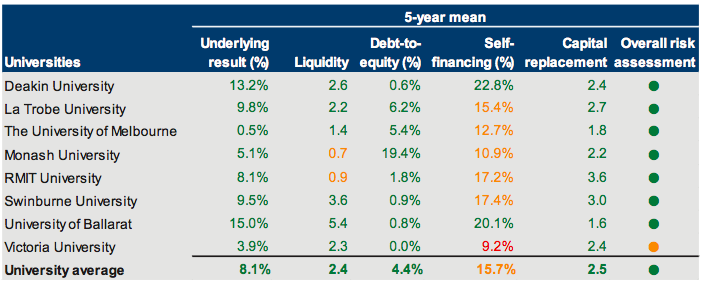

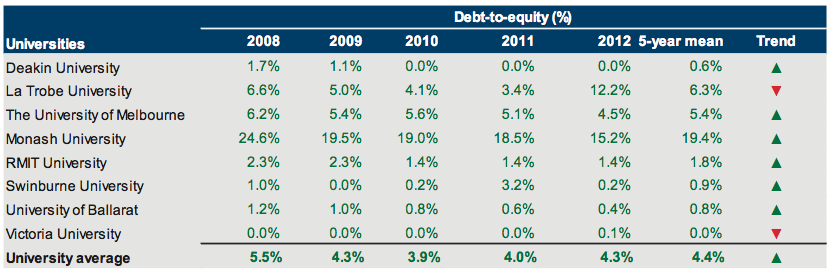

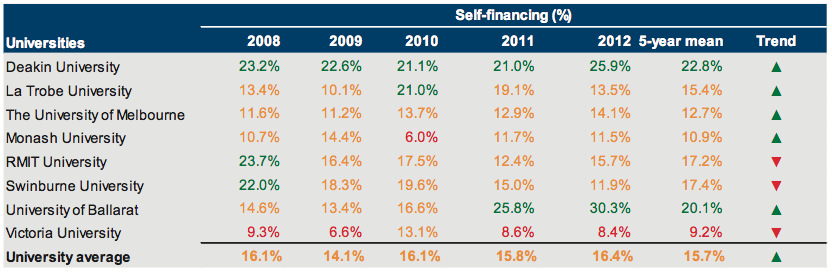

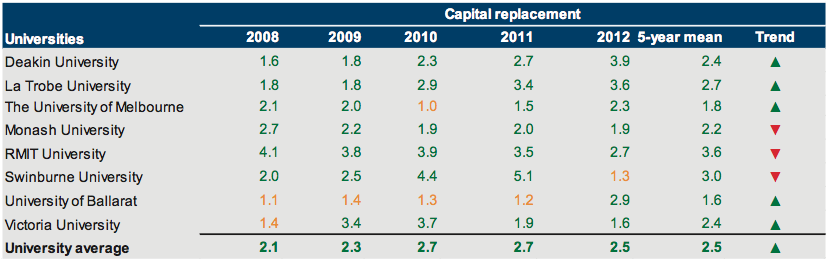

Victoria University was assessed as having medium financial sustainability risk due to its poor self-financing indicator. Monash University's financial sustainability risk was assessed as high due to low liquidity, however it had financial assets classified as 'available for sale' which can be converted to cash if required. The remaining six universities had a low financial sustainability risk in 2012.

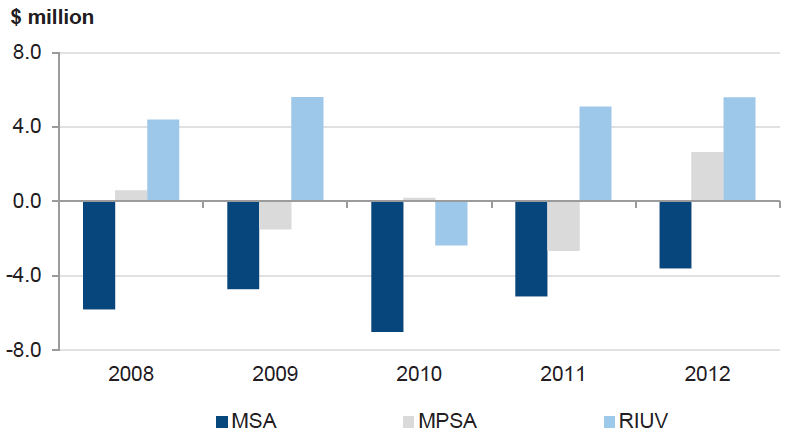

Universities that have established overseas campuses have experienced mixed financial success. Monash University's campus in South Africa is reliant on its parent to meet its ongoing expenditure commitments, requiring $34.0 million in loan funding over the past five years. Conversely, RMIT International University Vietnam has generated surpluses over the past five years totalling $30.5 million, and has no outstanding loans.

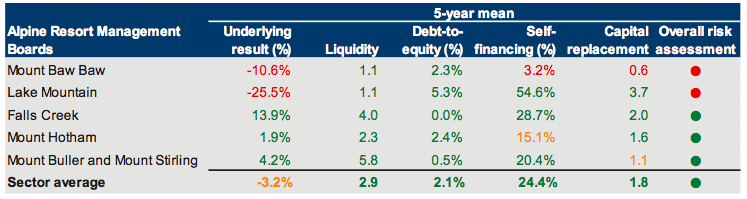

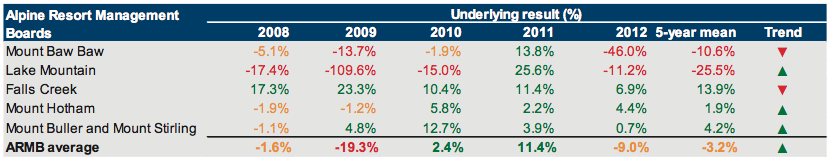

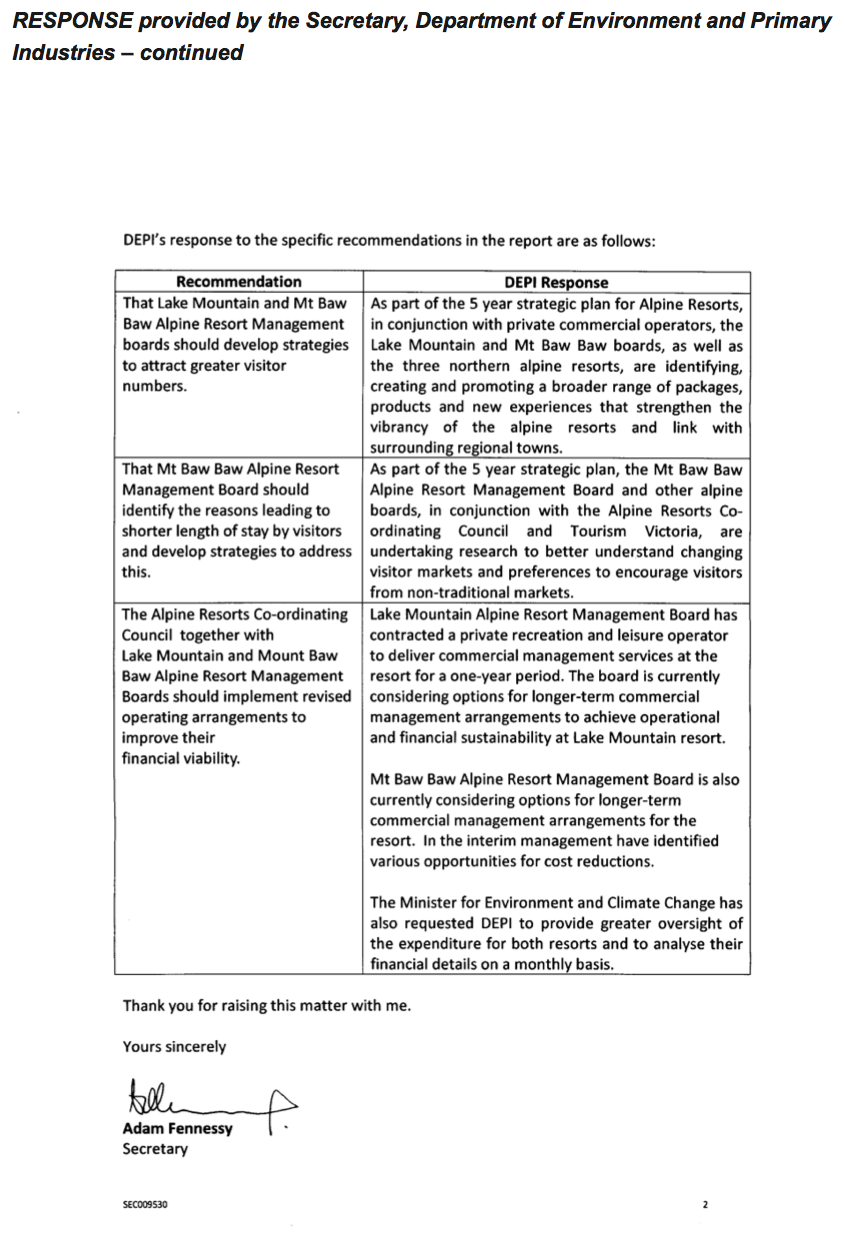

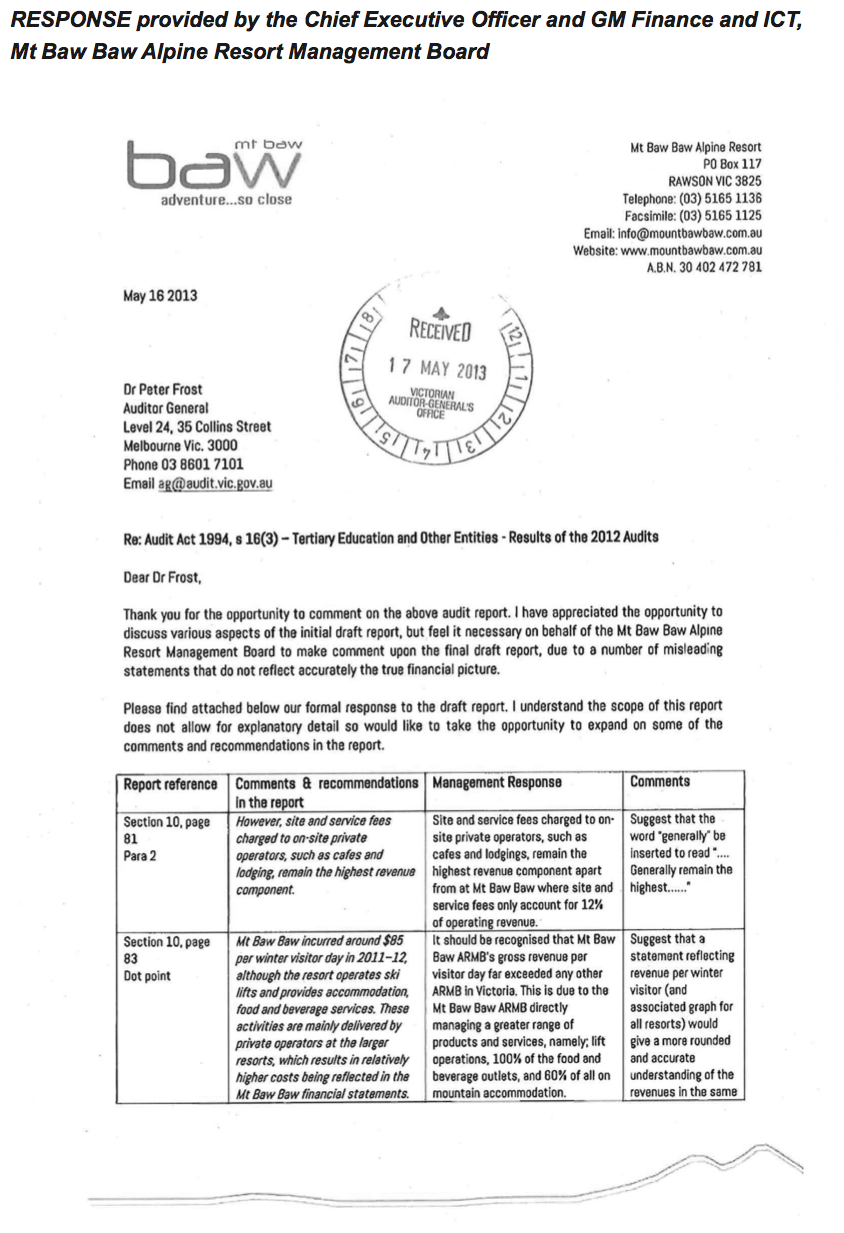

Alpine resorts collectively reported an operating deficit of $1.7 million in 2011–12 ($5.2 million surplus in 2010–11) notwithstanding support payments contributed by the Department of Environment and Primary Industries. Without this support funding, the sector's operating deficit would have been $4.9 million—similar to its 2011 result.

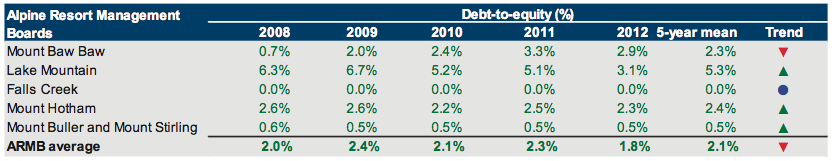

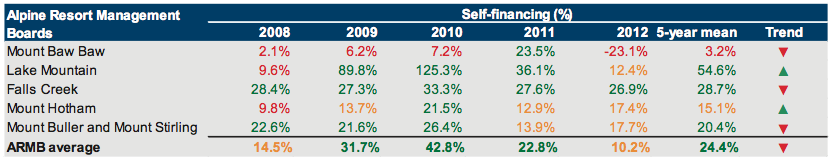

The three larger alpine resorts at Mt Buller and Mt Stirling, Mt Hotham and Falls Creek generated surpluses in 2012. These three resorts were assessed as having low financial sustainability risk on average for the past five years.

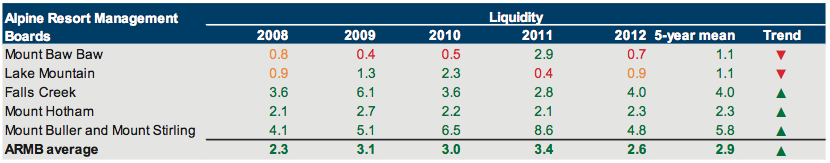

Financial sustainability continues to be of concern for Mt Baw Baw and Lake Mountain, with poor operating results and low liquidity levels placing them at high risk in 2011–12. Work has commenced on investigating sustainable operating solutions for Lake Mountain, with it appointing an external contractor to deliver services and products at the resort during 2013.

Internal controls

Overall, internal controls in TAFEs and universities were adequate for producing reliable, accurate and timely financial reports.

Internal audit functions were well developed, although four universities and five TAFEs did not have arrangements for internal auditors to report their conflicts of interests. Improvements could be made in relation to internal audit coverage, with a number of key business areas not subject to recent internal audit scrutiny.

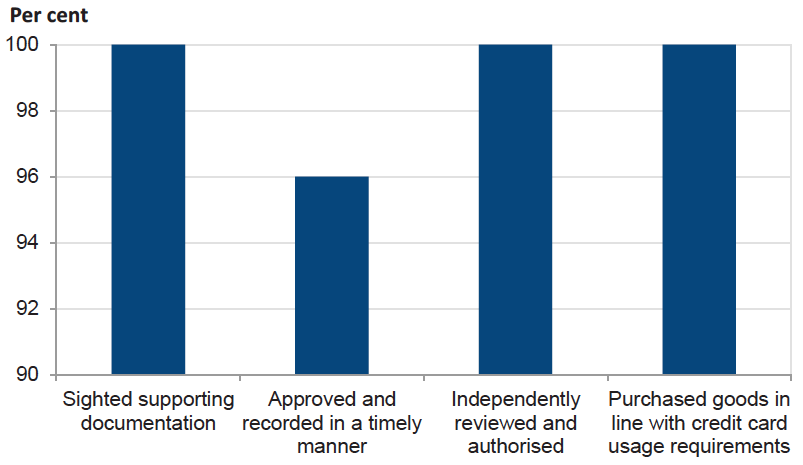

Controls over credit card purchasing were generally sound, however improvements can be made in relation to risk identification. Sample-based testing produced positive results, with identified internal controls operating in a majority of instances.

Ten of the 22 tertiary education entities (three universities and seven TAFEs) had not assessed themselves as being compliant with the requirements of the Payment Card Industry-Data Security Standard. This shows a lack of understanding of the importance of this high risk activitiy, and potentially exposes students to risks of identity theft or fraud if their credit card information is accessed by unauthorised persons.

- That universities and TAFEs address the better practice report preparation elements by preparing shell financial statements, performing materiality assessments and implementing rigorous analytical reviews, in order to improve the quality of reporting.

- That performance reporting for the tertiary education sector be elevated to legislative status, and a clear framework developed, with standard benchmarks and disclosure requirements.

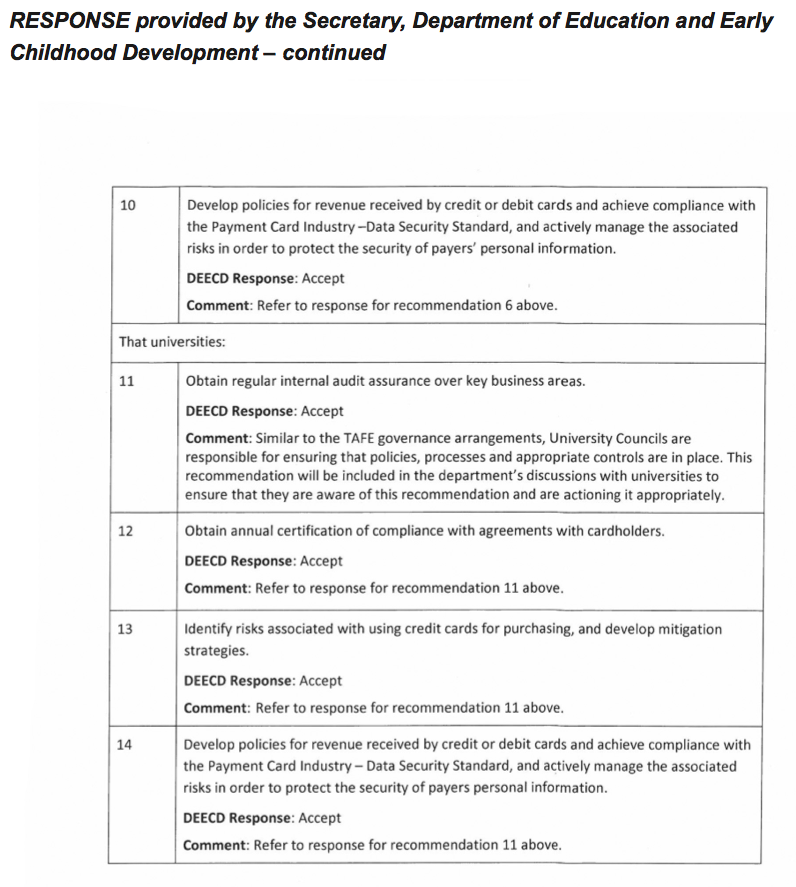

That TAFEs:

- review key strategies and service objectives set out in their strategic plans so that they are clearly expressed, aligned and measurable

- review their financial and non-financial key performance indicators to determine, and if necessary improve, their relevance and appropriateness to their key strategies and service objectives

- improve the quality of data relating to their international student cohort in order to better inform decision-making to improve their financial sustainability and to identify and promote a competitive advantage

- revise internal audit charters to address reporting conflicts of interest of internal auditors, and to outline the selection process for internal audit providers

- obtain regular internal audit assurance over key business areas, in particular cash management and operational efficiency and effectiveness

- obtain annual certification of compliance with agreements from cardholders

- identify risks associated with using credit cards for purchasing, and mitigation strategies

- develop policies for revenue paid by credit or debit cards and achieve compliance with the Payment Card Industry‑Data Security Standard, and actively manage the associated risks in order to protect the security of payers' personal information.

That universities:

- obtain regular internal audit assurance over key business areas

- obtain annual certification of compliance with agreements from cardholders

- identify risks associated with using credit cards for purchasing, and mitigation strategies

- develop policies for revenue paid by credit or debit cards and achieve compliance with the Payment Card Industry-Data Security Standard, and actively manage the associated risks in order to protect the security of payers' personal information.

- That Lake Mountain and Mt Baw Baw Alpine Resort Management Boards should continue to develop strategies to attract greater visitor numbers.

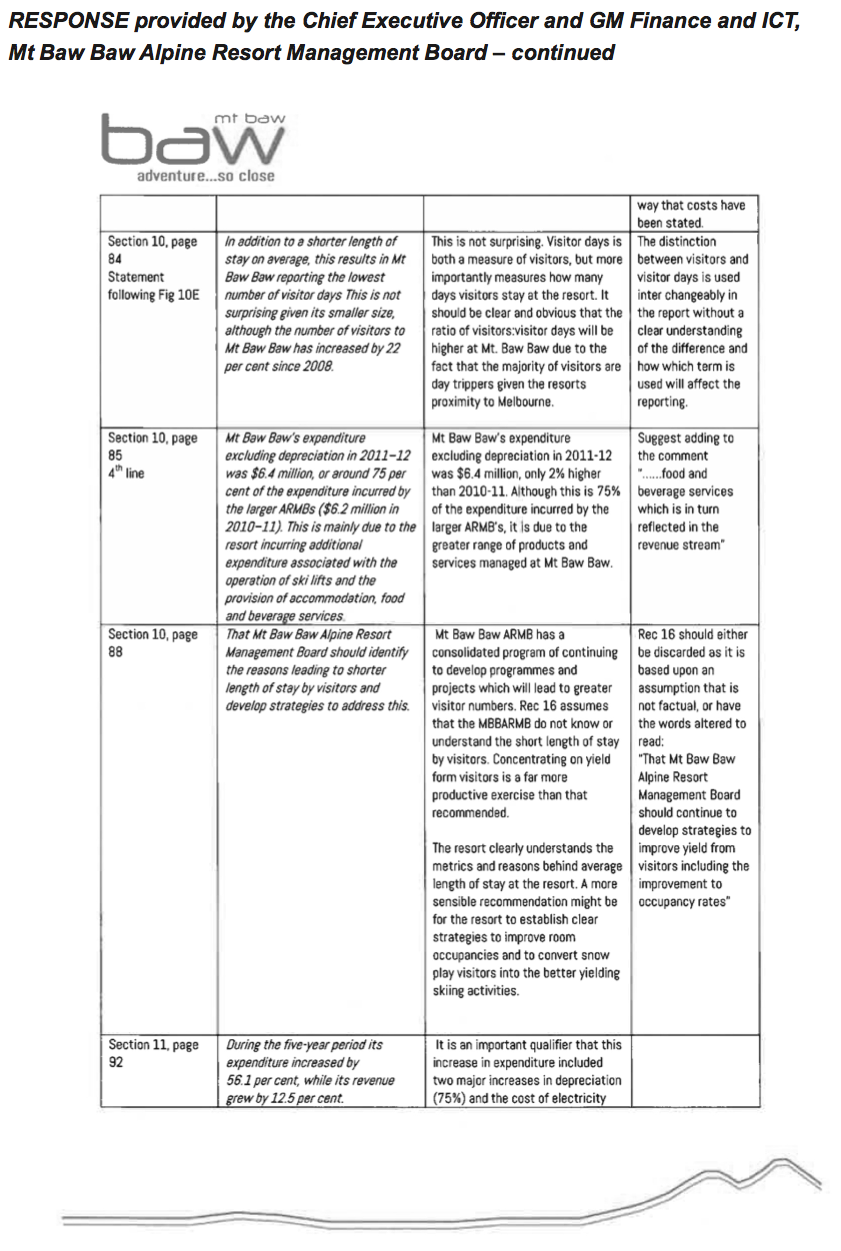

- That Mt Baw Baw Alpine Resort Management Board should identify the reasons leading to shorter length of stay by visitors and develop strategies to address this.

- The Alpine Resorts Co-ordinating Council together with Lake Mountain and Mt Baw Baw Alpine Resort Management Boards should implement revised operating arrangements to improve their financial viability.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report, or relevant extracts from the report, was provided to all universities, TAFEs, ARMBs, the Department of Treasury and Finance, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development and the Department of Environment and Primary Industries with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments however, are included in Appendix F.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

This report covers 106 entities with a financial year end other than 30 June 2012. Principally it deals with the results of the audits of 98 tertiary education sector entities, comprising universities, technical and further education (TAFE) institutes, training entities and the entities that they control. The profile of these entities is set out in Figure 1A.

Figure 1A

Entities with a financial year end other than 30 June 2012

2012–13 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Balance date |

|||||||

Sector |

Type of entity |

2011 |

31 Oct |

31 Dec |

31 Mar |

Other |

Total |

Tertiary Education |

University |

8 |

8 |

8 |

|||

Entity controlled by university |

57 |

53 |

3 |

56 |

|||

TAFE institute |

14 |

14 |

14 |

||||

Entity controlled by TAFE institute |

11 |

12 |

12 |

||||

Training entity |

7 |

7 |

7 |

||||

Entity controlled by training entity |

1 |

– |

– |

||||

Other |

– |

1 |

1 |

||||

Total Tertiary Education |

98 |

98 |

|||||

Sustainability and Environment |

Alpine resort |

5 |

5 |

5 |

|||

Health |

Charity |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|||

Planning and Community Development |

Trust |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|||

Local Government |

Company |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|||

Total |

106 |

5 |

96 |

1 |

4 |

106 |

|

Note: Controlled entities generally include associated companies, trusts and joint ventures.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The report informs Parliament about significant issues arising from the financial audits and augments the assurance provided through audit opinions on financial reports and performance reports included in the respective entities’ annual reports.

The report comments on the quality and timeliness of financial reporting and the financial sustainability of tertiary education bodies and alpine resort management boards. It also comments on the effectiveness of internal audit and credit card management controls in the tertiary education sector.

Other reports of the Victorian Auditor-General's Office on the results of financial audits for 2012 are outlined in Appendix B.

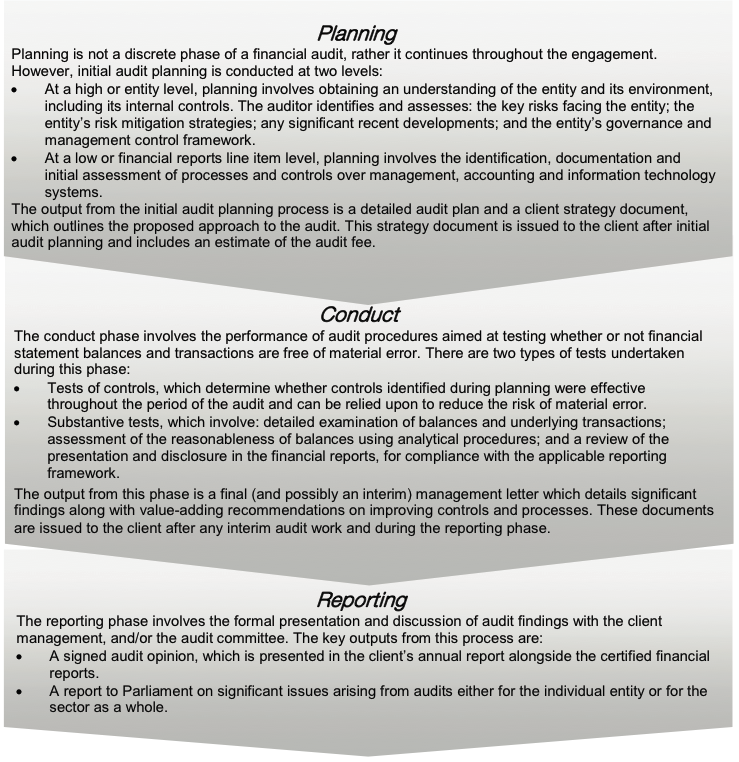

1.1.2 Audit of financial reports

An annual financial audit has two aims:

- to give an opinion consistent with section 9 of the Audit Act 1994, on whether the financial statements are fairly stated

- to consider whether there has been wastage of public resources or a lack of probity or financial prudence in the management or application of public resources, consistent with section 3A (2) of the Audit Act 1994.

The financial audit framework applied in the conduct of the 2012 audits is set out in Appendix C.

1.1.3 Audit of performance reports

Section 8(3) of the Audit Act 1994 authorises the Auditor-General to audit performance indicators included in the annual reports of a public sector entity to determine whether they fairly represent the entity's actual performance.

The Auditor-General uses this authority to audit the performance reports prepared by the TAFE sector.

1.1.4 Audit of internal controls

An entity's governing body is responsible for developing and maintaining its internal control framework. Internal controls are systems, policies and procedures that help an entity to reliably and cost-effectively meet its objectives. Sound internal controls enable delivery of reliable, accurate and timely external and internal reporting. The main components of an effective internal control framework and an explanation of the framework are set out in Appendix C.

1.2 Audit conduct

The audits of 98 tertiary education entities, five alpine resort management boards and three other entities were undertaken in accordance with the Australian Auditing Standards.

Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of preparing and printing this report was $225 000.

1.3 Structure of this report

Details of the entities covered within each Part of this report are set out in Figure 1B.

Figure 1B

Report structure

Report part |

Description |

|---|---|

Part B: Financial and performance reporting |

Reports the results of the 2012 financial audits of eight universities, 14 TAFE institutes, five alpine resort management boards, seven training entities and the 69 entities that they control. It also reports on performance reporting for the TAFE sector. |

Part C: TAFEs |

Reports the financial results and assesses the sustainability of the 14 TAFE institutes. It also comments on internal controls including over credit card management across the TAFE sector. |

Part D: Universities |

Reports the financial results and assesses the sustainability of the eight universities. It also comments on internal controls including over credit card management across the university sector. |

Part E: Alpine resorts |

Reports the financial results of five alpine resort management boards and assesses their financial sustainability. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

2 Financial reporting

At a glance

Background

Independent audit opinions add credibility to financial reports by providing reasonable assurance that the information reported is reliable and accurate. The timeliness and accuracy of the preparation of an entity's report is integral to the quality of financial reporting.

This chapter covers the results from the audits of the 106 entities with a financial year end other than 30 June 2012.

Findings

- The financial reports of all but three entities received clear audit opinions:

- Deakin University and The University of Melbourne received qualified opinions due to their accounting treatment for non-reciprocal research and capital grants.

- Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria received a qualified opinion due to the inherent risks associated with its cash donations.

- In 2012, 103 entities completed their financial reports within the mandated time frames.

Recommendation

That universities and TAFEs address the better practice report preparation elements by preparing shell financial statements, performing materiality assessments and implementing rigorous analytical reviews, in order to improve the quality of reporting.

2.1 Introduction

This chapter covers the results from the audits of the 106 entities with a financial year end other than 30 June 2012.

Each entity must prepare its financial report in accordance with Australian Accounting Standards, including the Australian Accounting Interpretations.

The principal legislation governing financial reporting by these entities in 2012 was the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA) and the Corporations Act 2001.

Appendix A details the legislative and reporting framework for the 106 entities.

2.2 Audit opinions issued

Clear audit opinions were issued on the financial reports of 103 entities for the year.

Independent audit opinions add credibility to financial reports by providing reasonable assurance that the information reported is reliable and accurate. A clear audit opinion confirms that the financial statements present fairly the transactions and balances for the reporting period, in accordance with the requirements of relevant accounting standards and legislation.

A qualified audit opinion means that the financial report is materially different to the requirements of the relevant reporting framework or accounting standards, and is less reliable and useful as an accountability document.

Qualifications

Three qualified audit opinions were issued for the 2012 financial year (three for 2011).

The University of Melbourne and Deakin University again received qualified audit opinions because their accounting treatment of non-reciprocal research and capital grant income as a liability was not in accordance with Australian Accounting Standards. Accounting standards require grants which are non-reciprocal to be recognised as revenue in the year they are received—when the entity gains control of the funds.

Deakin University regards the receipt of these monies as a reciprocal transfer where the grants have outstanding performance or return conditions and accounts for them in accordance with Australian Accounting Standard AASB 118 – Revenue. VAGO is of the opinion that these monies are non-reciprocal grants and should be accounted for in accordance with Australian Accounting Standard 1004 – Contributions, whereby such payments are treated as income in the year of receipt.

The Australian Accounting Standards Board is currently reviewing grant accounting in not-for-profit organisations. However, until that review is complete, the accounting standards in their current form apply.

The ongoing qualified opinion issued to the Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria is generally attached to the financial reports of entities with significant voluntary fundraising activities. The qualification draws attention to the risk inherent in management assuring the complete recording of cash collected through donations. The risk is unavoidable and cannot be cost-effectively mitigated by further internal controls.

Emphasis of matters

In certain circumstances an audit opinion may draw attention to, or emphasise, a matter relevant to the users of an entity’s financial report but does not warrant a qualification. Unmodified opinions can include an emphasis of matter (EOM) paragraph.

The audit opinion on the financial report of the International Fibre Centre Limited contained an EOM, which drew attention to the material uncertainty surrounding the continued existence of the company beyond 2013.

In previous years, the audit opinions of several entities included an EOM. The EOMs drew attention to each entity's reliance on continuing financial support from its parent entity to sustain its operations. An EOM was not included in audit opinions in 2012 where the entity had received a letter of financial support from its parent entity. In these instances, the entity was able to demonstrate that the going concern assumption was satisfied.

2.3 Quality of reporting

The timeliness and accuracy of the preparation of an entity's financial report is integral to the quality of reporting. Entities need to have a well-planned and managed preparation process to achieve cost-effective and efficient financial reporting.

In 2012, 103 entities completed their financial reports within their mandated time frames. The audited financial statements for three entities had not been finalised at the time of writing this report.

Overall, the financial report preparation processes of universities and technical and further education (TAFE) institutes produced accurate, complete and reliable information. There was an overall improvement in all key areas that form a better practice reporting framework. The framework applied in assessing the quality of reporting is detailed in Appendix C.

Figure 2A shows that the overall quality of financial reporting improved in 2012.

Figure 2A

Quality of financial reporting in 2012

|

Quality of financial reporting |

Universities |

TAFEs |

Total |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(%) |

(no.) |

(%) |

(no.) |

(%) |

(no.) |

|

|

Improved from previous year |

25 |

2 |

36 |

5 |

28 |

7 |

|

Same as previous year |

75 |

6 |

64 |

9 |

72 |

15 |

|

Worse than previous year |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Total |

100 |

8 |

100 |

14 |

100 |

22 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The assessment of performance was against better practice criteria using the following scale:

- no existence—function not conducted by the entity

- developing—partially encompassed in the entity's financial reporting process

- developed—entity has implemented the process, however it is not fully effective or efficient

- better practice—entity has implemented processes which are effective and efficient.

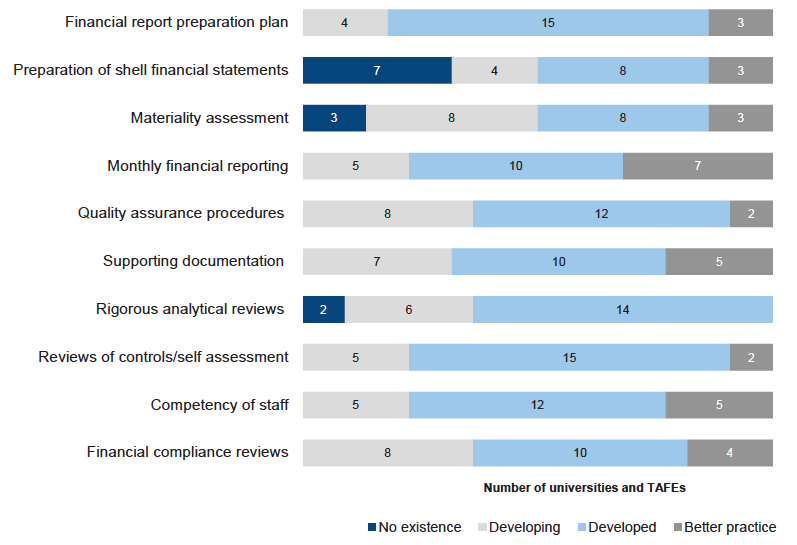

Figure 2B summarises the results of our analysis.

Figure 2B

Results of assessment of report preparation processes against better practice elements

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Further improvement is needed in relation to:

- preparation of shell financial accounts

- materiality assessments

- rigorous analytical reviews

- quality assurance procedures

- financial compliance reviews.

There was no noticeable improvement in these areas in 2012. Improving these areas will assist the quality of reporting by enabling the timely preparation of financial reports and early detection and correction of errors.

The Victorian Skills Commission (VSC) previously prepared model financial statements for TAFEs, although this was not the case in 2012. VSC's activities have been assumed by the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, with the entity ceasing to exist from 31 December 2012.

Recommendation

- That universities and TAFEs address the better practice report preparation elements by preparing shell financial statements, performing materiality assessments and implementing rigorous analytical reviews, in order to improve the quality of reporting.

3 Performance reporting

At a glance

Background

Fourteen technical and further education (TAFE) institutes, four universities and two training entities are required to include an audited statement of performance in their annual report.

This chapter outlines the performance reporting framework and comments on the results of our audits of these reports. It also highlights our intention to develop our audit of performance reports in future periods.

Conclusion

A formal performance reporting framework is yet to be developed for the tertiary education sector. The usefulness of current performance information reported by the sector is limited as there is little consistency in indicators and targets across the sector. The relevance and appropriateness of current indicators merits review.

Findings

- Use of targets was inconsistent across the performance statements audited, with 45 per cent of entities setting benchmarks for less than half of their indicators.

- Explanations for variances between targets and actual results were not provided by 25 per cent of the 20 entities.

Recommendations

- That performance reporting for the tertiary education sector be elevated to legislative status, and a clear framework developed, with standard benchmarks and disclosure requirements.

That TAFEs:

- review key strategies and service objectives set out in their strategic plans so that they are clearly expressed, aligned and measurable

- review their financial and non-financial key performance indicators to determine, and if necessary improve, their relevance and appropriateness to their key strategies and service objectives.

3.1 Introduction

The Audit Act 1994 empowers the Auditor-General to audit any performance indicators in the report of operations of an audited entity to determine whether they:

- are relevant to any stated objectives of the entity

- are appropriate for the assessment of the entity’s actual performance

- fairly represent the entity’s actual performance.

The annual attest audit of performance statements currently expresses an opinion on whether the reported results are presented fairly and whether they have been prepared in accordance with the Financial Management Act 1994. It does not express an opinion on the relevance or appropriateness of the performance information reported.

This chapter outlines the performance reporting framework and comments on the results of our audits of the associated statements in 2012. It also signals our intention to further develop our audit of the performance statements in the future.

3.2 Elements of effective performance reporting

Effective performance measurement and monitoring enables managers and the governing boards of entities to evaluate performance against a set of key indicators. It also facilitates appropriate and timely action to achieve organisational objectives and outcomes. Reporting on performance to senior management and the community is an important part of a performance management framework and public sector accountability.

Central to effective performance measurement, management and reporting is a comprehensive suite of relevant and appropriate performance measures or indicators, and targets.

Relevant indicators have a logical and consistent relationship to an entity's objectives and are linked to the outcomes to be achieved. Ideally they should take into account immediate deliverables and long-term sustainability.

Appropriate indicators give sufficient information to assess the extent to which the entity has achieved a predetermined target, goal or outcome. They can include the trends in performance over time, performance relative to that of similar agencies and performance relative to benchmarks.

Fair presentation of performance results requires that the information provided is able to be measured, consistently represents what it purports to indicate without bias, and is accurate and auditable.

3.3 Performance reporting by education entities

The preparation of performance statements by technical and further education (TAFE) and other tertiary education entities is not mandated under legislation. In November 2008 the Department of Innovation, Industry and Regional Development (DIIRD)—now the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation—issued an executive memorandum requesting 20 entities report on certain key performance indicators (KPI). This included the 14 TAFEs, four universities with TAFE divisions and two training entities. DIIRD required the performance indicators to be disclosed in a performance statement, subject to audit by the Auditor-General, and included in the entity's annual report.

The current indicators reported on by the 20 entities are:

- participation of 15–24 year olds

- participation of 25–64 year olds

- module load completion rate

- student satisfaction

- total cost per student contact hour

- working capital ratio

- net operating margin

- fee for service revenue

- revenue per equivalent full-time staff

- student contact hours

- energy consumption.

Minimal guidance was provided by the DIIRD on the calculation method for these indicators, and no further guidance has been issued since the original memorandum.

3.4 Audit opinions issued

This year we reviewed the performance indicators of 20 entities. They comprised the 14 TAFEs and:

- Ballarat University

- RMIT University

- Swinburne University of Technology

- Victoria University

- Centre for Adult Education

- Driver Education Centre of Australia.

Clear audit opinions were issued on the 20 performance reports.

3.5 The quality of reporting

3.5.1 Indicators reported

KPIs need to be reliable, relevant and measurable. They are most effective where there is consistent application of underlying data and calculation method across entities. This allows for the comparison of results over time and against other bodies.

The current arrangements for tertiary sector performance reporting do not prescribe how each indicator should be measured. As a result, entities are using different calculation methods and many of the indicators, and therefore performance, is incomparable across entities.

The indicators that commonly result in difficulty in comparison are:

- participation of 15–24 year olds

- participation of 25–64 year olds

- student contact hours

- energy consumption.

These indicators in particular are quantitative measures which ignore the relative size of an entity. Larger entities may report better results against participation indicators because of their expanded capacity, rather than as a result of sound management. Conversely, smaller entities may have better energy consumption rates because of reduced campus sizes.

In contrast, the indicators that best enable cross-entity comparisons are:

- module load completion rate

- cost per student contact hour

- fee for service revenue

- revenue per equivalent full-time staff.

These indicate how well an entity is performing in a particular area, and are not distorted by the size of the entity's operations.

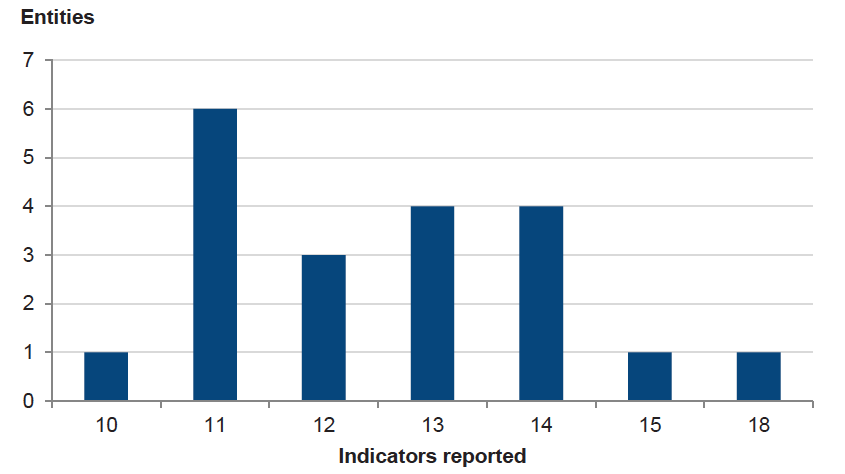

The number of indicators reported by the 20 entities varies, as presented in Figure 3A.

Figure 3A

Indicators reported in performance statements

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The range of indicators was mainly due to some entities reporting energy consumption in greater detail. Eight reported an aggregate result for energy consumption, while 11 provided a breakdown based on various energy sources. The remaining entity did not include energy consumption results in its performance statement, however, it provided a separate report on environmental performance.

The usefulness of performance reporting by TAFEs would be improved with a review of the indicators used, and consistency in their calculation.

3.5.2 Achievement of targets

Effective performance reporting includes a comparison of results against indicators that are consistent across the sector. Benchmarks provide users of information with a clearer understanding of how an entity has performed against like industry operators.

The current performance reporting framework does not prescribe a set of standard indicators, targets or benchmarks. As a result, entities are able to set their own indicators and targets, or report only actual results.

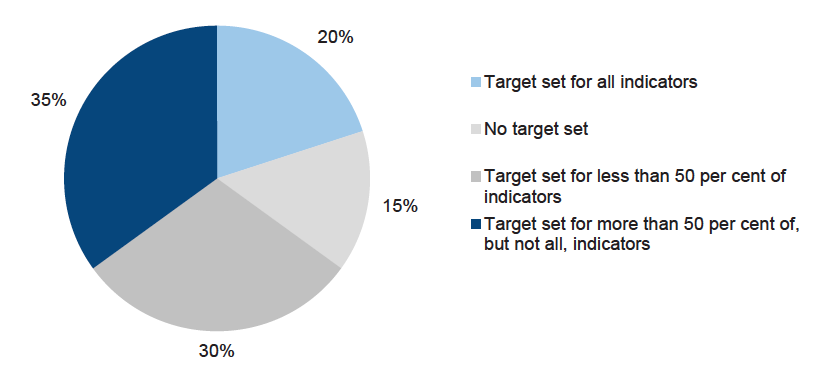

Figure 3B shows the number of targets set by the 20 entities.

Figure 3B

Target setting

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Target setting was generally poor, with 45 per cent of performance statements including them for less than half the indicators reported.

To be useful, KPIs should be consistent across a number of entities and reflect a predetermined level of required performance. Targets should reflect a standard for each particular KPI that is relevant and appropriate to the entity.

3.5.3 Quality of analysis

Comparative information is important, as it highlights how an entity has performed over a period of time. We noted that nine of the 20 entities that prepared performance reports did not include results achieved in the prior year.

Sound performance reporting is accompanied by commentary explaining why a target was not achieved, or analysing variances from year to year. This provides greater clarity around the information reported and offers users a clearer picture of why performance varied.

Explanations for significant variances in the actual result to the target or prior year result were provided by 75 per cent of entities (15 of 20) in 2012. However, where provided, the analysis was generally poor, with commentary stating that a variance had occurred, without giving an explanation why.

3.6 Future audit approach

Performance reporting for tertiary education entities was established in 2008. Since that time, we have focused the audit of performance information on whether the reports fairly present performance and comply with the legislative requirements.

However, given that performance reporting has been in place within the sector for more than five years, we intend to expand our audit of performance indicators in future periods, to promote improvement in the sector and exercise audit's complete mandate. On 26 April 2013 it was gazetted that TAFEs were required to have a current strategic plan that included financial and non-financial KPIs. The KPIs were to have clear links with each TAFE's key strategies.

Recognising the relative immaturity of existing performance information across the sector, and the scale of improvements required to achieve relevant and appropriate performance indicators, we intend to gradually move to express an opinion on the relevance and appropriateness of the indicators reported in TAFE performance statements.

We intend to implement this approach over a three-year period. In the years ending 31 December 2013 and 2014 we propose to convey our opinion on the relevance and appropriateness of performance indicators through management letters to encourage their further development, while continuing to express a public opinion on their fair representation. We will also provide an update each year on the sector's progress in our annual report on the results of audits.

In the third year, TAFEs will be expected to provide a suite of measures that are relevant and appropriate for assessing the TAFE's performance, and that fairly represent that performance. From that year the public audit opinion will address the relevance and appropriateness of the indicators and whether they fairly present performance. Where this standard is not met, a qualified audit opinion may be issued on the performance statement.

This transitional approach will require the support of the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development and the TAFEs to achieve the desired outcome—more transparent and meaningful reporting on TAFE performance to the community.

Recommendations

- That performance reporting for the tertiary education sector be elevated to legislative status, and a clear framework developed, with standard benchmarks and disclosure requirements.

That TAFEs:

- review key strategies and service objectives set out in their strategic plans so that they are clearly expressed, aligned and measurable

- review their financial and non-financial key performance indicators to determine, and if necessary improve, their relevance and appropriateness to their key strategies and service objectives.

4 Part C: Technical and further education institutes

4. Financial results – TAFEs

At a glance

Background

Accrual-based financial statements enable an assessment of whether entities are generating sufficient surpluses from operations to maintain services, fund asset maintenance and retire debt. This chapter analyses the financial results of the 14 technical and further education (TAFE) institutes for the year ended 31 December 2012.

Findings

- TAFEs collectively generated a surplus of $58.5 million in 2012, down 39.1 per cent on the 2011 result.

- Ten of the 14 TAFEs recorded a lower operating result in 2012 than 2011, driven by:

- a decrease in capital government grants of $39.5 million or 40.1 per cent

- an increase in employee costs of $25.7 million or 3.5 per cent.

- International student fee revenue decreased by $7.1 million or 6.3 per cent to $105.5 million in 2012—the lowest level over the past five years.

- Domestic student fee revenue increased by $7.7 million or 11.8 per cent in 2012, and represented 41.0 per cent of total student fees (36.9 per cent in 2011).

- Only six of the 11 TAFEs with international students were able to provide comprehensive data on their enrolments, such as country of residence and enrolments by semester.

Recommendation

That TAFEs improve the quality of data relating to their international student cohort in order to better inform decision-making to improve their financial sustainability and to identify and promote a competitive advantage.

4.1 Introduction

Accrual-based financial statements enable an assessment of whether technical and further education (TAFE) institutes are generating sufficient surpluses from operations to maintain services, fund asset maintenance and retire debt. Their ability to generate surpluses is subject to the regulatory environment in which they operate, and their ability to minimise costs and maximise revenue.

An entity's financial performance is measured by its net operating result—the difference between its revenues and expenses. An entity's financial position is generally measured by reference to its net assets—the difference between its total assets and total liabilities.

4.2 Financial results

4.2.1 Financial performance

The TAFE sector generated a surplus of $58.5 million in 2012, a decrease of $37.5 million or 39.1 per cent over the prior year. This was mainly due to an increase in employee related costs, and a decrease in government grants received by the sector.

Figure 4A provides a comparison of the total operating result for the TAFE sector for 2012 and 2011.

Figure 4A

Surplus/(deficit) by TAFE, 2011 and 2012

|

Entity |

2012 |

2011 |

|---|---|---|

|

Advance TAFE |

(874) |

4 027 |

|

Bendigo Regional Institute of TAFE |

257 |

(2 530) |

|

Box Hill Institute of TAFE |

8 355 |

19 362 |

|

Central Gippsland Institute of TAFE |

5 939 |

10 803 |

|

Chisholm Institute of TAFE |

3 538 |

6 402 |

|

Gordon Institute of TAFE |

13 129 |

17 213 |

|

Goulburn Ovens Institute of TAFE |

11 493 |

(4 474) |

|

Holmesglen Institute of TAFE |

4 622 |

13 488 |

|

Kangan Institute of TAFE |

(1 197) |

16 129 |

|

Northern Melbourne Institute of TAFE |

5 107 |

13 676 |

|

South West Institute of TAFE |

(653) |

1 665 |

|

Sunraysia Institute of TAFE |

81 |

(1 446) |

|

William Angliss Institute of TAFE |

(1 081) |

(1 005) |

|

Wodonga Institute of TAFE |

9 798 |

2 694 |

|

Total |

58 514 |

96 004 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Figure 4A shows that 10 TAFEs reported a lower result in 2012 than in 2011.

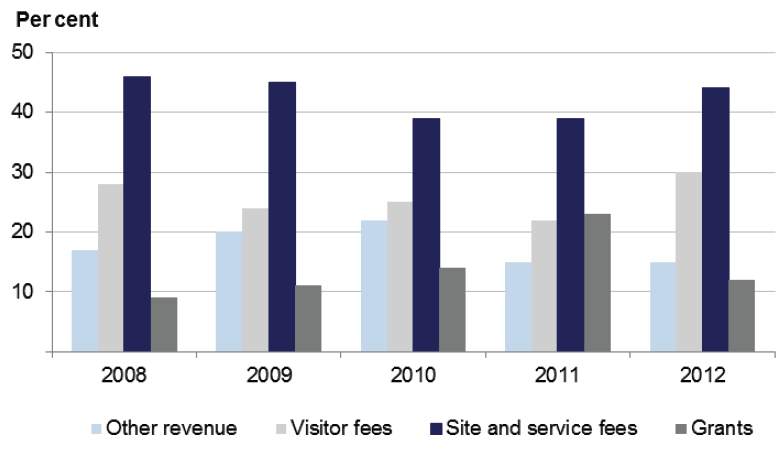

Revenue

In 2012 TAFEs collectively generated revenue of $1.2 billion, a decrease of $13.1 million from 2011. The decrease was mainly due to a reduction of 40.1 per cent in government capital grants.

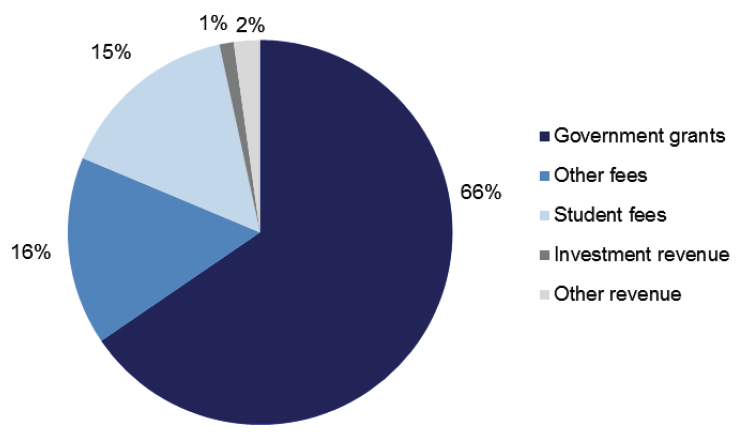

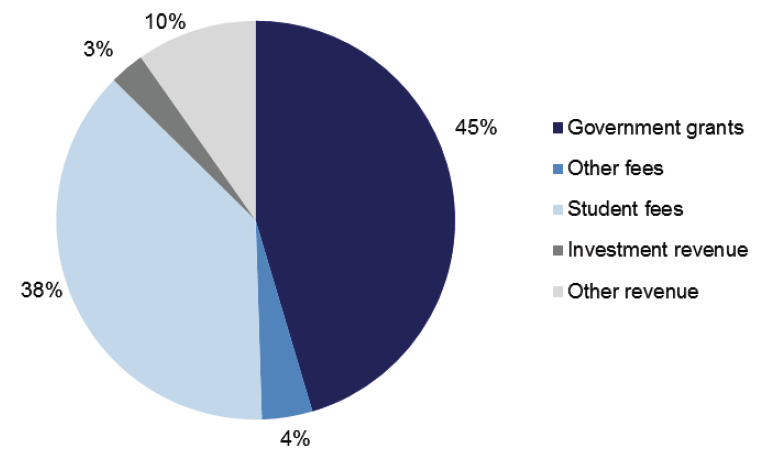

Nevertheless government funding remained the largest revenue component for TAFEs, comprising 66 per cent of total revenue in 2012. The majority comprised $539.0 million in operating grants from the State Government ($525.5 million in 2011) and $168.1 million from the Commonwealth Government ($157.9 million in 2011). These figures included capital grants from the state and Commonwealth governments which decreased to $59.1 million in 2012 ($98.6 million in 2011).

The composition of operating revenue for 2012 is presented in Figure 4B.

Figure 4B

TAFE revenue composition, 2012

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Figure 4B highlights the sector's financial dependence on government. Student fees generated 15 per cent of total revenue in 2012, highlighting the sector's relatively low level of self-generated income.

Trends in student fee revenue

Student fee revenue did not change materially in 2012, with the sector reporting a total of $178.9 million ($178.2 million in 2011). However, the following TAFEs experienced significant variances in 2012:

- Goulburn Ovens Institute of TAFE—an increase of $1.03 million or 30.9 per cent

- Wodonga Institute of TAFE—an increase of $0.464 million or 20.9 per cent

- Northern Melbourne Institute of TAFE—a decrease of $2.02 million or 7.5 per cent.

Total student fee revenue increased by 18.2 per cent from 2008–12, despite a volatile international student market during the period.

Recent policy changes in the TAFE sector increasing competition between private and public sector tertiary education providers mean it is increasingly important that TAFEs proactively target students and modify their marketing activities and course design to attract enrolments and to enhance their competitive advantage. This is especially important in the international student market, as international students generate higher revenue per student than domestic enrolments, and their fees are an important factor in the ongoing viability of individual TAFEs and the sector.

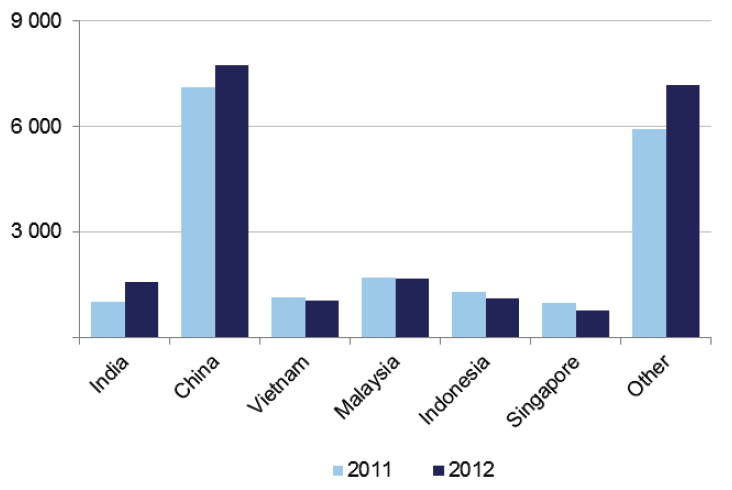

International students

International student fee revenue declined by $7.1 million or 6.3 per cent to $105.5 million in 2012—their lowest level over the past five years.

Fees received from international students represented 59.0 per cent of total student fees in 2012 (62.1 per cent in 2011). International student fee revenue has decreased in the past two years, contributing to the decline in surpluses.

Therefore, it is of concern that only six of the 11 TAFEs with international students were able to provide us with comprehensive data on student enrolments.

Common data issues included:

- inability to provide a breakdown of student countries of residence

- inconsistent reporting of figures from year to year

- deficiencies in comparative figures

- unable to provide commencement details.

TAFEs are heavily reliant on revenue from international students, and a lack of quality information may impact on their ongoing ability to attract and retain these students. With the international market in decline it is important that TAFEs improve the quality of this data to maximise their return on effort and investment, and to improve their financial sustainability.

Domestic students

Domestic student fee revenue increased by $7.7 million or 11.8 per cent in 2012, and represented 41.0 per cent of total student fees (36.9 per cent in 2011).

Domestic student fee revenue increased at the following TAFEs in 2012:

- Goulburn Ovens Institute of TAFE—an increase of $1.0 million or 29.3 per cent

- Chisholm Institute of TAFE—an increase of $1.3 million or 11.9 per cent

- Holmesglen Institute of TAFE—an increase of $3.0 million or 39.0 per cent.

Fee revenue from domestic students has increased in four of the past five years and, over the period from 2008–12, increased by 68.9 per cent.

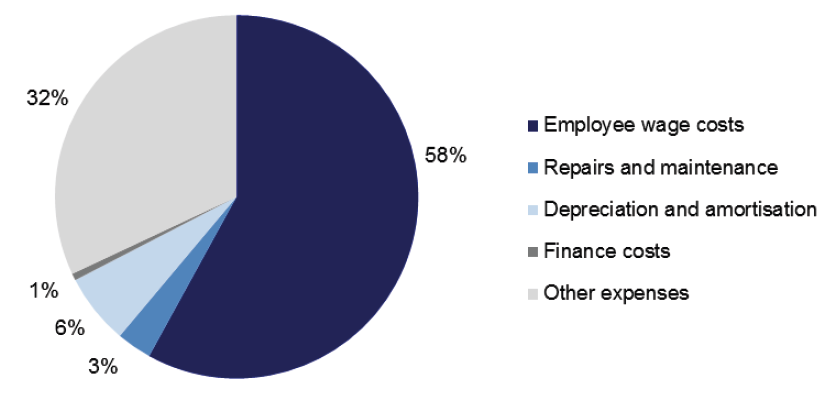

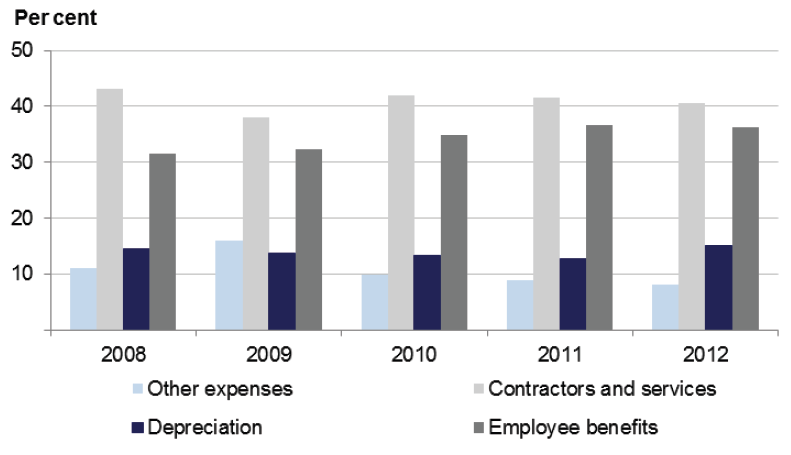

Expenses

In 2012 the 14 TAFEs collectively incurred $1.1 billion in operating expenses, an increase of $24.4 million or 2.2 per cent from the prior year. The increase was predominantly due to:

- employee benefits up $25.7 million or 3.5 per cent

- depreciation up $4.0 million or 6.4 per cent.

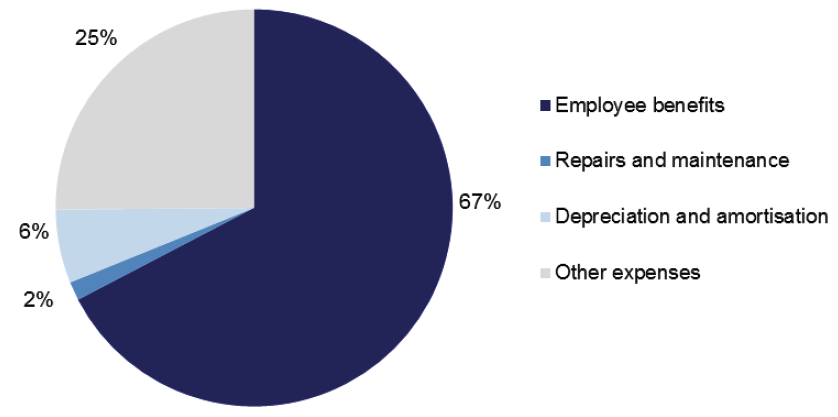

Figure 4C shows the composition of TAFE expenditure for 2012.

Figure 4C

TAFE expenditure composition, 2012

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Employee-related costs remained the most significant expenditure item, representing 67 per cent of total expenses in 2012 (66 per cent in 2011). Expenditure composition for the TAFE sector was consistent with 2011.

4.3 Financial position

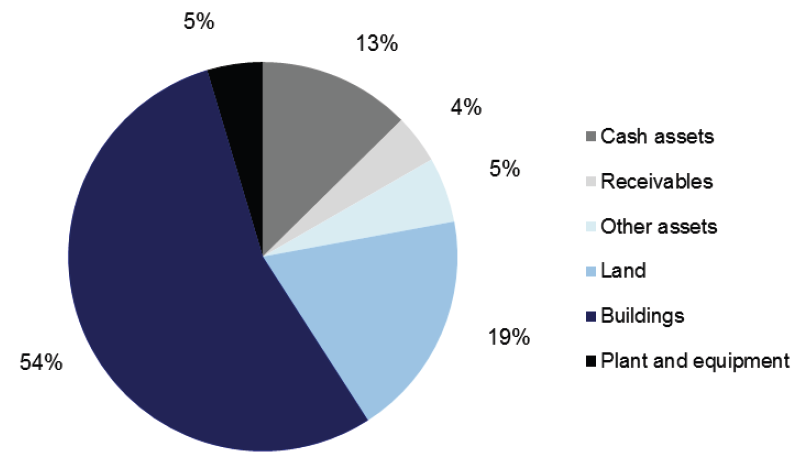

An entity’s financial position is generally measured by reference to its net assets—the difference between its total assets and total liabilities. However, this measure is less appropriate for TAFEs, as they are not-for-profit entities, and generally do not hold assets that generate revenue. While they carry land and buildings of significant value on their balance sheets, representing 73 per cent of their total assets, the revenue base of TAFEs is not tied to the value of their assets and most of their assets cannot be readily sold to obtain funds.

The objective for a TAFE should, therefore, be to maintain and improve its asset base and related service provision, while managing levels of debt.

4.3.1 Assets

During 2012 the total value of TAFE assets increased by $176.5 million or 8.0 per cent to $2.4 billion. This was mainly due to an increase in the values of land and building assets as well as a $35.0 million increase in cash assets (15.6 per cent).

Land and buildings were revalued at all TAFEs in 2012, based on independent assessments by the Valuer-General.

Significant increases in the value of land included:

- Northern Melbourne Institute of TAFE—an increase of $25.5 million or 39.4 per cent

- Chisholm Institute of TAFE—an increase of $11.2 million or 32.7 per cent

- Holmesglen Institute of TAFE—an increase of $10.1 million or 18.9 per cent.

Building values increased by $92.5 million or 7.8 per cent. This was due to new asset construction and some valuation increments, including at:

- Box Hill Institute of TAFE—an increase of $24.8 million or 29.3per cent

- Central Gippsland Institute of TAFE—an increase of $14.9 million or 37.8 per cent

- Holmesglen Institute of TAFE—an increase of $17.4 million or 8.0 per cent.

The composition of TAFE assets in 2012 is presented in Figure 4D.

Figure 4D

TAFE asset composition, 2012

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

4.3.2 Liabilities

At 31 December 2012 the total value of liabilities for the TAFE sector was $235.0 million. This was substantially the same as in 2011, although there were movements noted in each class of liability. A $6.8 million increase in payables was offset by a $9.7 million decrease in provisions. There was a decrease in employee benefit provisions at 11 of the 14 TAFEs, mainly due to fewer staff as a result of structured redundancy programs.

Provisions (47 per cent) and payables (38 per cent) continued to represent the majority of total TAFE liabilities.

Recommendation

- That TAFEs improve the quality of data relating to their international student cohort in order to better inform decision-making to improve their financial sustainability and to identify and promote a competitive advantage.

5 Financial sustainability – TAFEs

At a glance

Background

To be financially sustainable, entities need to be able to meet current and future expenditure as it falls due. They also need the ability to absorb foreseeable changes and materialising risks. This chapter provides our insight into the financial sustainability of the technical and further education (TAFE) institutes based on our analysis of the trends in five key financial indicators over a five-year period.

Conclusion

Four TAFEs were assessed as having low financial sustainability risk in 2012. The remaining 10 were assessed as medium risk, due to poor results for their self-financing indicator and capital replacement indicators. The sector's financial sustainability has declined between 2008 and 2012.

Findings

- TAFEs generally recorded poor self-financing indicators, indicative of an inability to fund asset replacement or renewal with cash generated from operating activities.

- Capital replacement indicator results had declined at nine TAFEs, suggesting that assets are being consumed faster than they are being replaced.

5.1 Introduction

To be financially sustainable, entities need to be able to meet their current and future expenditure as it falls due. They also need the ability to absorb foreseeable changes and financial risks as they materialise.

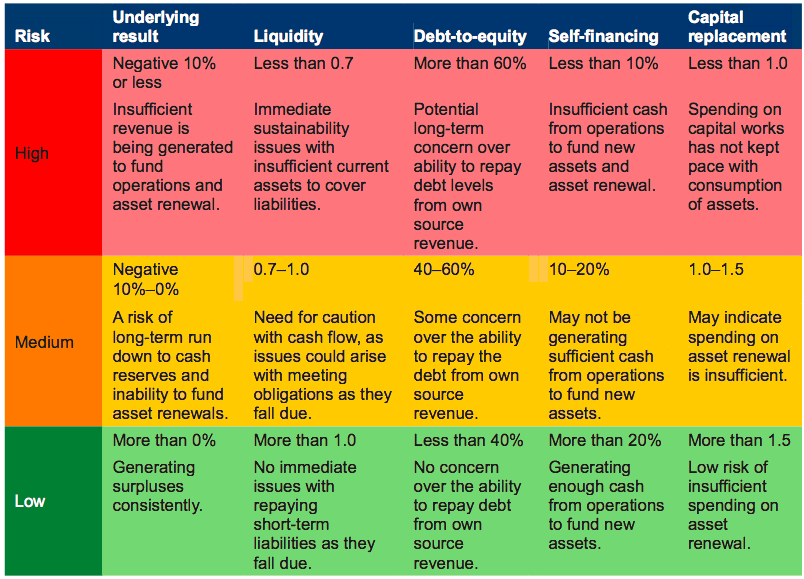

In this chapter we provide insight into the financial sustainability of the 14 technical and further education (TAFE) institutes through analysing the trends in each of five financial sustainability indicators over a five-year period. The five indicators are:

- underlying result

- liquidity

- debt-to-equity

- self-financing

- capital replacement.

Appendix D describes the sustainability indicators and risk assessment criteria used in this report.

The financial sustainability indicators and assessments flag departures from the norm that warrant attention. However, to form a definitive view of an entity’s financial sustainability, a holistic analysis that moves beyond financial indicators is required, including an assessment of the entity’s operations and the regulatory environment. These additional considerations are not examined in this report.

5.2 Financial sustainability

5.2.1 Overall assessment

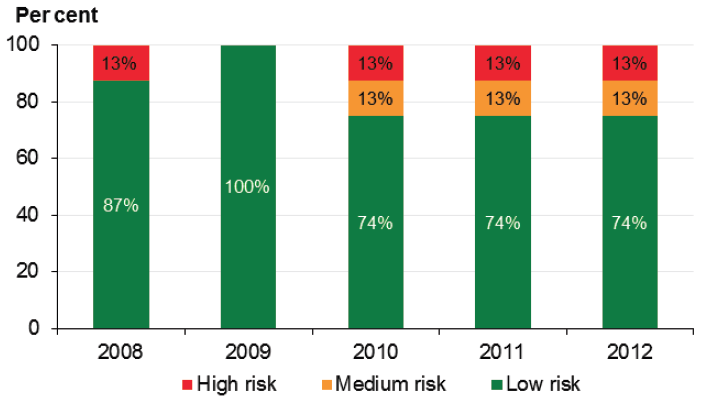

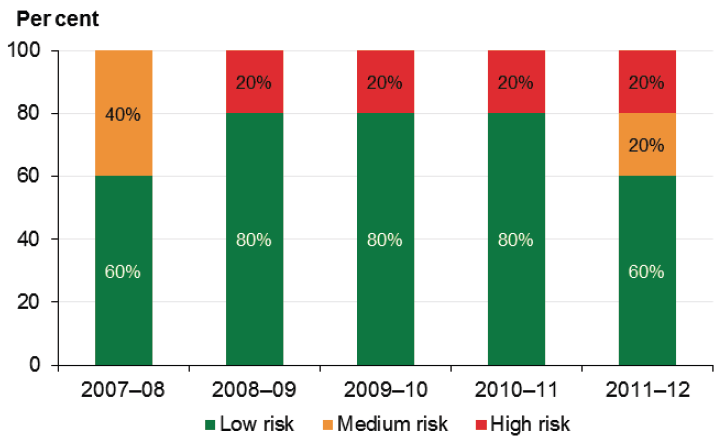

The risk to financial sustainability for four TAFEs was assessed as low for 2012. The risk for the remaining 10 was assessed as medium, due to poor self-financing and capital replacement indicators.

Figure 5A provides a summary of our overall financial sustainability risk assessment results for the past two years.

Figure 5A

Two-year financial sustainability risk assessment

|

Entity |

2012 |

2011 |

|---|---|---|

|

Advance TAFE |

Medium |

Low |

|

Bendigo Institute |

Medium |

Medium |

|

Box Hill Institute |

Medium |

Medium |

|

Central Gippsland Institute |

Low |

Low |

|

Chisholm Institute |

Medium |

Low |

|

Gordon Institute |

Low |

Medium |

|

Goulburn Ovens Institute |

Medium |

Medium |

|

Holmesglen Institute |

Low |

Medium |

|

Kangan Institute |

Medium |

Low |

|

Northern Melbourne Institute |

Medium |

Low |

|

South West Institute |

Medium |

Low |

|

Sunraysia Institute |

Medium |

Medium |

|

William Angliss Institute |

Medium |

Medium |

|

Wodonga Institute |

Low |

Low |

|

Total |

14 |

14 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

This shows that the risk to financial sustainability for the sector as a whole deteriorated between 2011 and 2012, with the number of TAFEs with medium risk to their financial sustainability increasing from seven to 10 over the two years.

5.2.2 Summary of trends in risk assessments over the five‑year period

When the risk assessments for each indicator are analysed for the sector they show the following trends over the five years to 2012:

- underlying result—the number of TAFEs in the medium-risk category has increased from three to four, with the remainder in the low-risk category

- liquidity—the number of TAFEs in the low-risk category has remained stable at14

- debt-to-equity—the number of TAFEs in the low-risk category has remained stable at 14

- self-financing—the number of TAFEs in the high-risk category has increased from three to nine

- capital replacement—the number of TAFEs in the high-risk category has increased from two to six

In summary, the sector's financial sustainability has deteriorated over the past five years.

5.2.3 Analysis of trends in sustainability indicators across the five-year period

To further understand the results, we analysed the five-year data for the five indicators. The relevant data are reproduced in Appendix B.

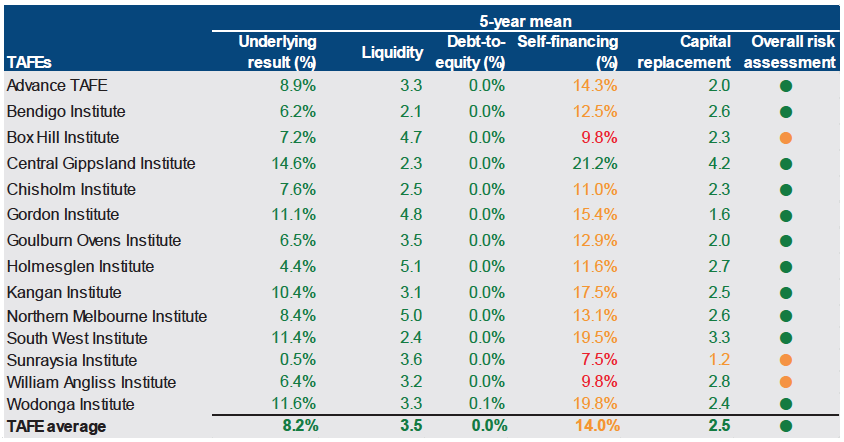

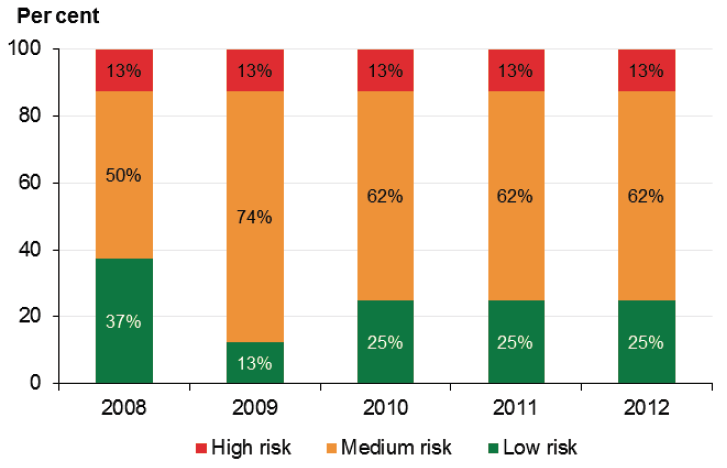

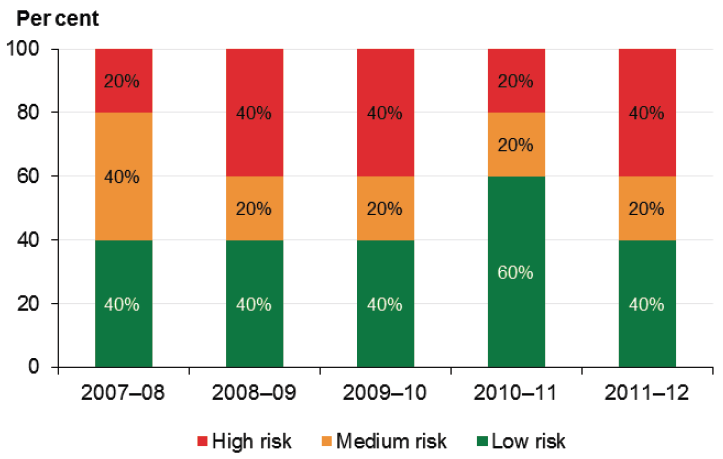

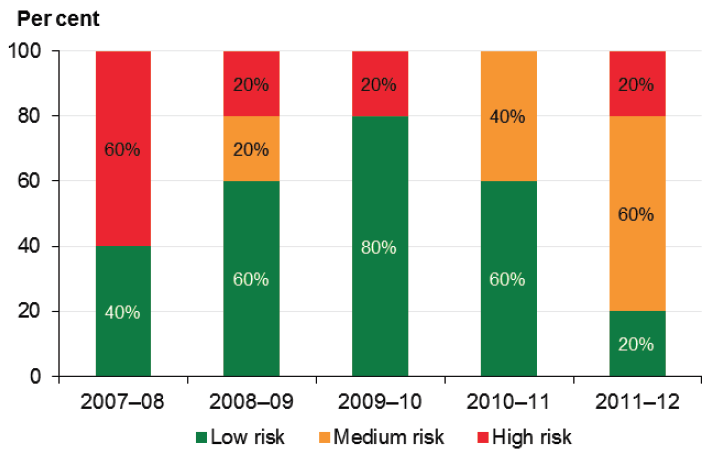

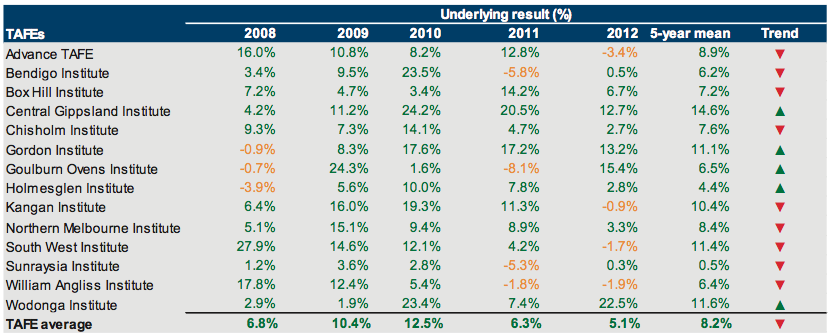

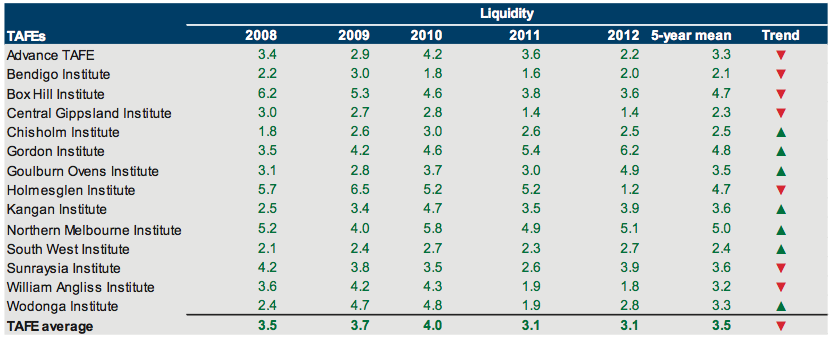

Figure 5B shows the mean sustainability risk assessments for the 14 TAFEs, over the five years from 2008 to 2012. High-risk results are shown in red, medium risk in orange, and low risk in green.

Figure 5B

Five-year mean financial sustainability risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The underlying result, liquidity and debt-to-equity results are positive, with all TAFEs recording risk assessments of low during the past five years.

However, deeper analysis revealed that the average underlying result for TAFEs has decreased since 2010. Nine of the 14 TAFEs recorded a lower result for this indicator in 2012 than in 2008. The decline highlights the challenge for the sector to achieve positive financial operating results following changes in the funding model.

TAFEs have generally recorded poor self-financing results over the five-year period and the result has deteriorated since 2008. Cash generated from operating activities decreased 41.9 per cent from 2010 to 2012 and now represents less than 10 per cent of underlying revenue balances.

The capital replacement indicator also declined over the five-year period. This indicator compares the level of asset renewal against the depreciation expense, or the consumption of existing assets. Changes in the funding model have resulted in TAFEs cutting expenditure viewed as 'non-essential', including construction of capital assets. Payments for property, plant and equipment decreased by $53.5 million (35.6 per cent) to $96.7 million in 2012.

Impact of changes in legislation and funding model on sustainability

Changes to the legislative framework and funding model introduced in 2012 mean that TAFEs are more reliant on tuition fees for generating a major portion of their operating revenue. These tuition fees include domestic and international student fees, as well as fees for service. Consequently, there is less reliance on government grants. As a result of this changed environment, TAFEs need to proactively review their courses to focus on those that attract students in order to generate funds and be sustainable.

The changes in the operating model and cuts in funding have had a significant impact on TAFEs. As well as reducing or changing course offerings, the sector has responded by making staff redundant, closing campuses to drive down costs and attempting to sell land and buildings.

The financial impact in 2012 included:

- increased employment costs due to redundancies paid

- lower employee benefit provisions, due to fewer ongoing staff

- constraints over operating costs to reduce overheads

- downward revaluations of assets in some entities to reflect infrastructure assets no longer required or in use.

The full effect of the changes to the funding model was realised from 1 January 2013, when the cost to students undertaking vocational education and training increased. This may reduce participation.

There is a risk that if individual TAFEs do not change their operations to cut costs and increase student revenue, they may become unsustainable.

The funding model for TAFEs has not progressively funded them for the depreciation of their assets, instead allocating capital grants strategically across the sector. This means that funds for replacing assets were not provided until the government considered replacement was appropriate, given its strategic review of the sector's needs and other spending priorities.

As a result of the TAFE Reform Panel's 2013 report, A strong and sustainable Victorian TAFE sector, a number of changes have been announced. The government has reiterated its commitment to competitive neutrality in the vocational training sector and is considering more flexible financing options for TAFEs. The government stated that TAFE institutes will be required to demonstrate the capacity to operate commercially. They will also need to cover their depreciation costs through their operations.

The government will provide contestable funding of $200 million over four years to support the ongoing financial sustainability of TAFE institutes, including $100 million in infrastructure funding.

5.3 Five-year trend analysis

This section analyses and comments on the trends in the five sustainability indicators for the sector over the past five years. The indicators reflect each entity's funding and expenditure policies, and identify whether these policies are sustainable.

Financial sustainability should be viewed from both the short and long-term perspective. The shorter-term indicators—underlying result and liquidity—focus on an entity's ability to maintain positive operating cash flows and adequate cash holdings, and to generate an operating surplus over time.

The longer-term indicators—debt-to-equity, self-financing and capital replacement—identify whether adequate funding is available to repay debt, replace assets to maintain the quality of service delivery, and to meet community expectations and the demand for services.

5.3.1 Underlying result

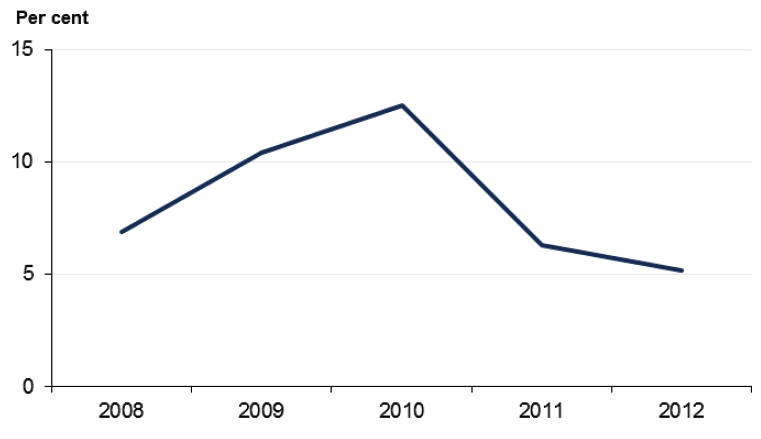

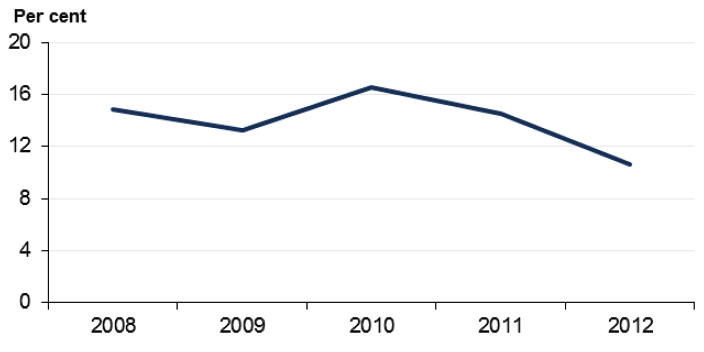

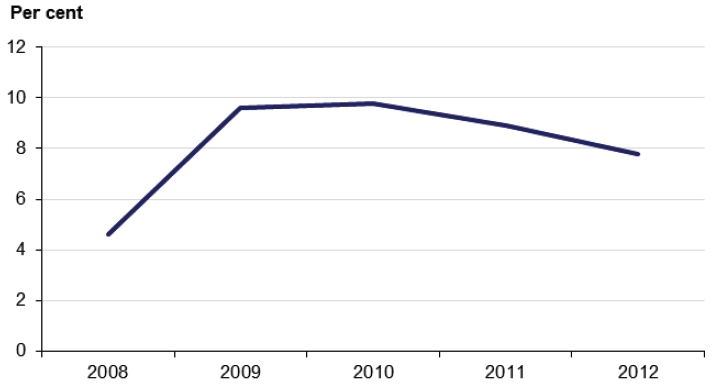

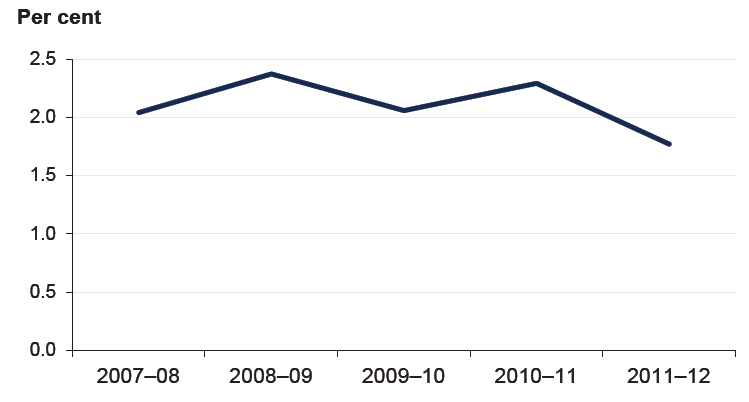

Figure 5C shows that the average underlying result has deteriorated over the past three years.

Figure 5C

Average underlying result

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Ten of the 14 TAFEs generated an operating surplus in 2012 (10 in 2011). However, only four of the 10 reported an improved underlying result in 2012. The worsening position indicates that expenses are growing faster than revenue and places the long‑term financial sustainability of TAFEs at risk.

During the past five years, nine of the 14 TAFEs recorded a deficit at least once.

Figure 5D shows the number of TAFEs in the medium-risk category was consistent with 2011.

Figure 5D

Underlying result risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

5.3.2 Liquidity

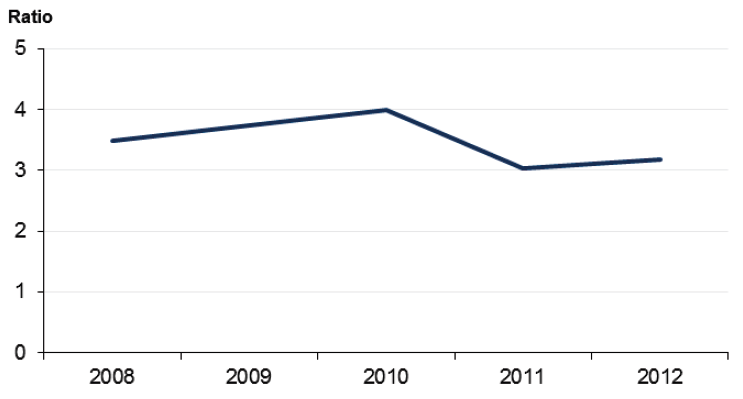

Figure 5E shows that current assets have exceeded current liabilities in each of the past five years.

Figure 5E

Average liquidity indicator

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

All 14 TAFEs were in the low-risk category for the liquidity indicator for each of the five years. Current assets are at least three times the value of current liabilities. TAFEs have few liabilities, largely limited to payables and employee-related provisions.

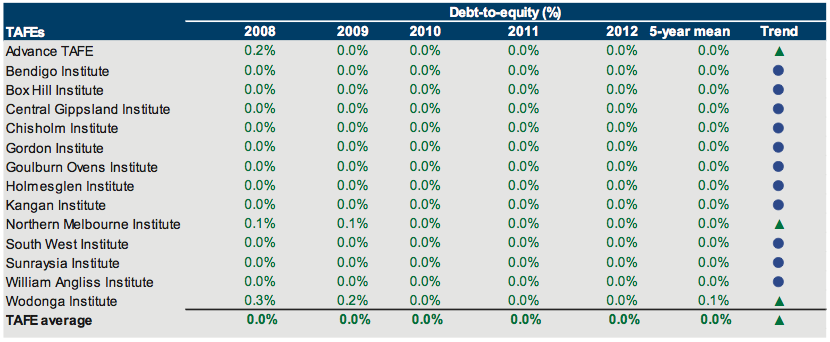

5.3.3 Debt-to-equity

Figure 5F shows that all TAFEs were in the low-risk category for the debt-to-equity ratio for the past five years.

Figure 5F

Average debt-to-equity indicator

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

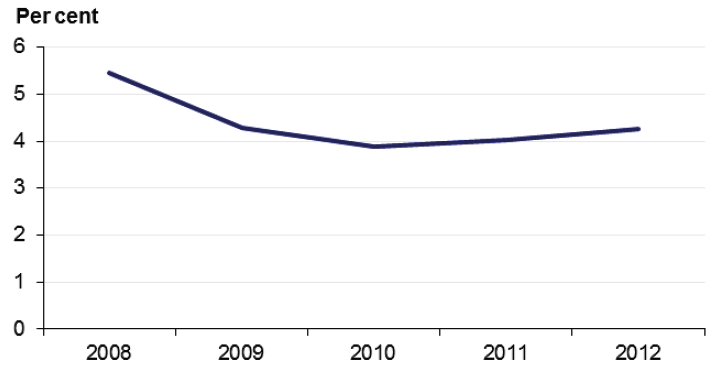

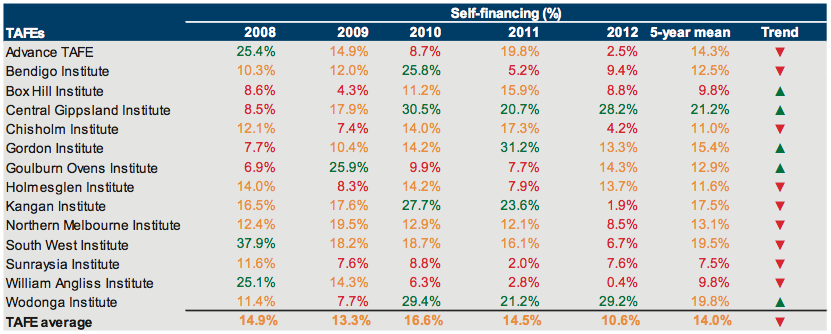

5.3.4 Self-financing

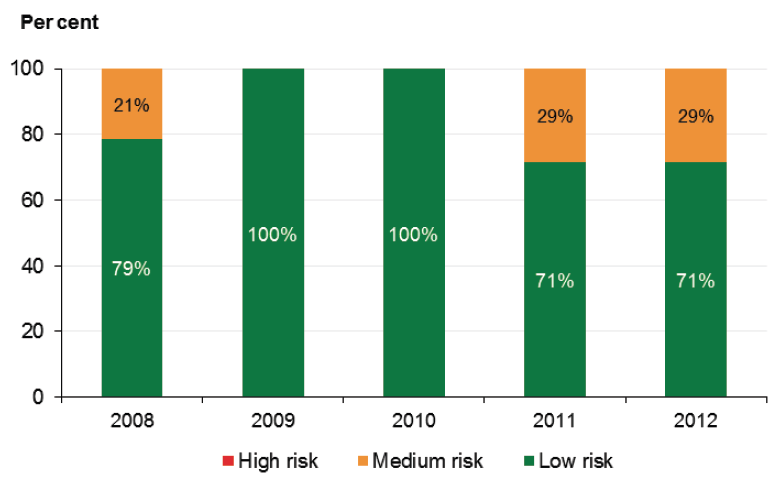

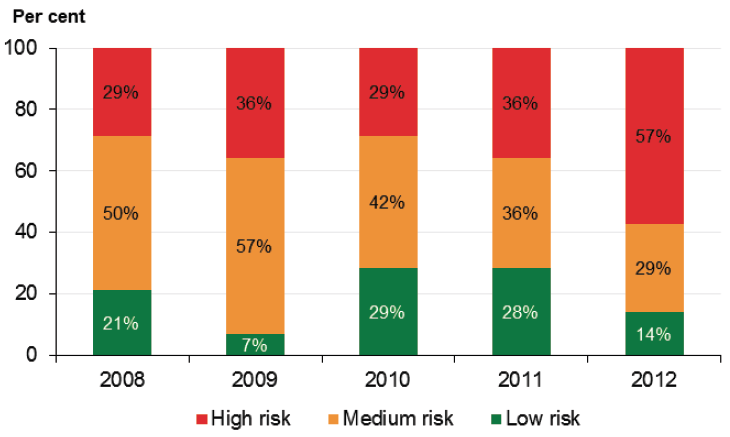

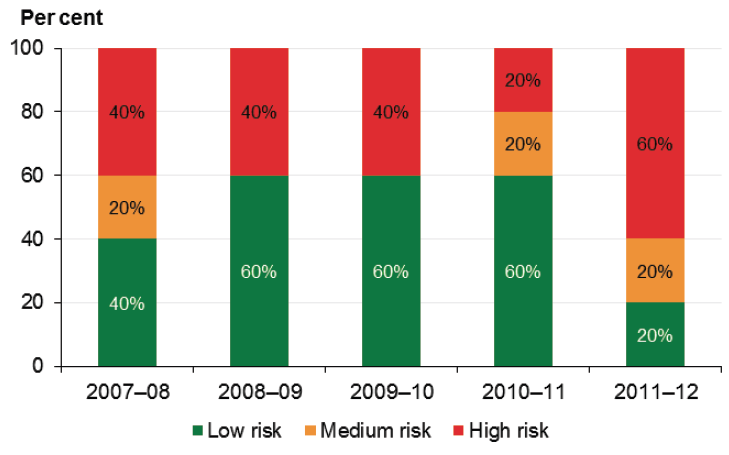

Figure 5G shows the significant decline in the TAFE sector's self-financing indicator since 2010.

Figure 5G

Average self-financing indicator

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

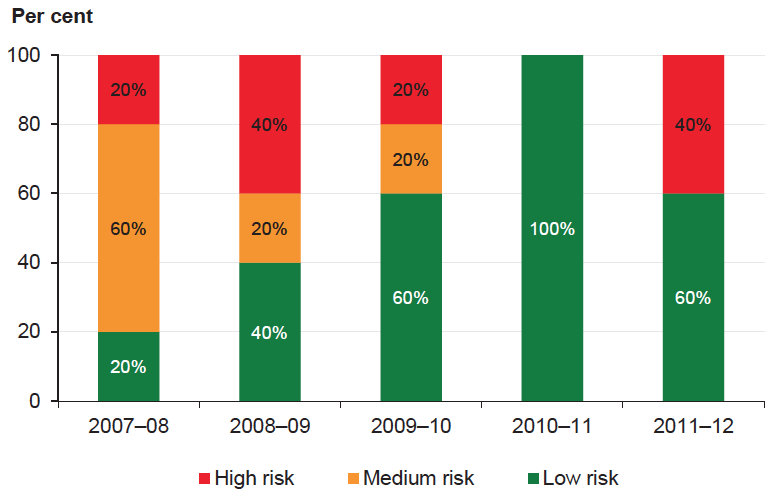

Figure 5H shows that the majority of TAFEs (eight of 14) now have a self-financing risk of high and that 86 per cent are now in the high- or medium-risk categories (72 per cent in 2011).

Figure 5H

Self-financing risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Most TAFEs are not able to generate sufficient cash from their operating activities to fund asset replacement. The government's review of financing arrangements may enable TAFEs to borrow funds for asset replacement. In addition, on 7 May 2013 the government confirmed that $100 million in contestable capital funding would be provided to help meet this shortfall over the next four years.

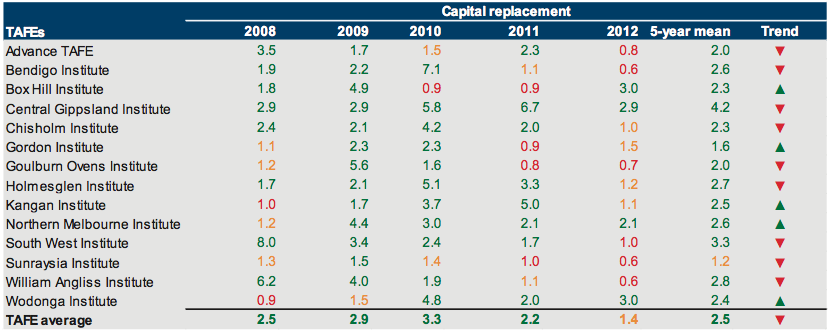

5.3.5 Capital replacement

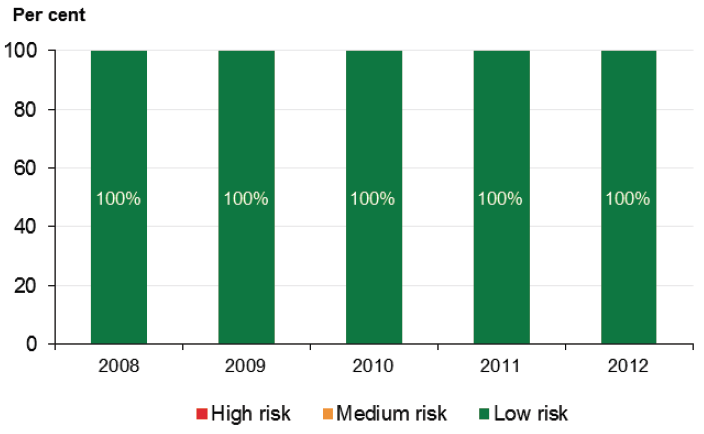

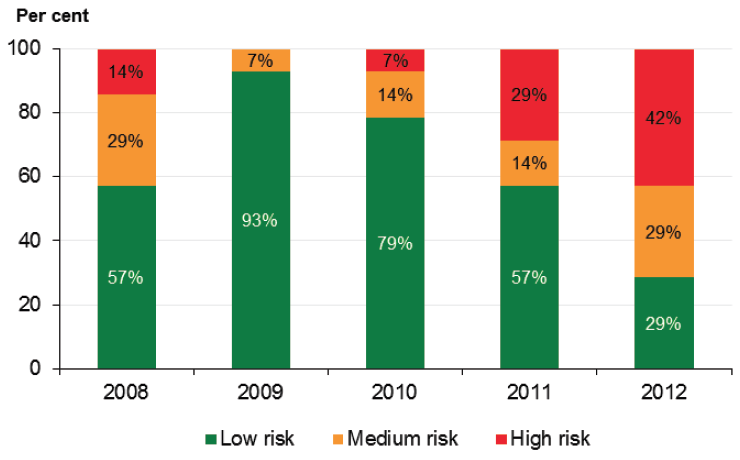

Figure 5I shows a significant increase in the number of entities in the high-risk category over the five-year period.

Figure 5I

Capital replacement risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Ten of the 14 TAFEs (71 per cent) are now in either the medium or high-risk category. If greater capital investment does not occur, assets will deteriorate at a greater rate than they are replaced or renewed. This presents a risk to the long-term financial sustainability of TAFEs, as buildings and other infrastructure assets will become unusable.

Capital spending has decreased over the past three years, while depreciation expenses have increased.

Government capital grants to the TAFE sector decreased by 40 per cent to $59.1 million in 2012. The decline, in conjunction with poor capital replacement indicator results, highlights the dependence of TAFEs on government funding to undertake capital programs.

6 Internal controls – TAFEs

At a glance

Background

This chapter presents the results of our assessment of general internal controls and controls over internal audit and credit cards in the technical and further education (TAFE) sector.

Conclusion

Internal controls were adequate for producing reliable, materially accurate and timely financial reports. All TAFEs had internal audit functions that reflected many of the better practice elements in the framework. Frameworks and associated controls for use of credit cards for purchasing were generally sound. Early action is needed by noncompliant TAFEs to develop policies for credit and debit card revenue, achieve compliance with the Payment Card Industry-Data Security Standard (PCI‑DSS) and actively manage the associated risks.

Findings

- Forty-six per cent of internal audit charters (six of 13) did not address the process for selecting the internal auditors, and five did not have arrangements for internal auditors to report conflicts of interest.

- Only seven of 14 TAFEs had self-assessed compliance with the PCI-DSS.

Recommendations

That TAFEs:

- revise internal audit charters to address reporting conflicts of interest of internal auditors, and to outline the selection process for internal audit providers

- obtain regular internal audit assurance over key business areas, in particular cash management and operational efficiency and effectiveness

- obtain annual certification of compliance with agreements from cardholders

- identify risks associated with using credit cards for purchasing, and mitigation strategies

- develop policies for revenue paid by credit or debit cards and achieve compliance with the Payment Card Industry-Data Security Standard, and actively manage the associated risks in order to protect the security of payers' personal information.

6.1 Introduction

Comprehensive internal controls help entities reliably and cost-effectively meet their objectives. Reliable internal controls are a prerequisite for the delivery of reliable, accurate and timely external and internal financial reports.

In our annual audits we focus on the internal controls relating to financial reporting and assess whether entities have managed the risk that the financial statements may not be complete and accurate. Poor internal controls diminish management's ability to achieve their entity's objectives and comply with relevant legislation. They also increase the risk of fraud and error.

The governing body of each technical and further education (TAFE) institute is responsible for developing and maintaining internal controls that enable:

- preparation of accurate financial reports and other supporting information

- timely and reliable external and internal reporting

- appropriate safeguarding of assets

- prevention and detection of errors and irregularities.

The Education and Training Reform Act 2006 and the Financial Management Act 1994 require management of TAFE institutes to implement effective internal control structures.

In this chapter we report on aspects of internal controls in the state's 14 TAFEs including:

- general internal controls

- internal audit

- credit card management.

6.2 General internal controls

Internal controls at the 14 TAFEs were adequate for maintaining the reliability of external financial reporting. Nevertheless, a number of control weaknesses were reported to governing bodies and management during the course of the 2012 audits.

The commonly identified areas that require improvement were:

- account reconciliations

- documentation of policies

- segregation of duties.

Weaknesses found during audits were brought to the attention of an entity's chairperson, management and audit committee by way of management letters.

6.2.1 Account reconciliations

A financial report is prepared based on information captured in an entity's general ledger. Key balances within the general ledger are often supported by information recorded in subsidiary ledgers such as accounts payable, billing, fixed assets and payroll systems. Periodic reconciliation of the general ledger with subsidiary ledger balances is vital to confirm the completeness and accuracy of data.

While TAFEs were generally preparing key account reconciliations, we identified a number of instances where improvements could be made. In some instances reconciliations had not been prepared or reviewed.

6.2.2 Documentation of policies

Documented policies provide a frame of reference for staff, and communicate management's expectations in relation to particular activities. In the absence of documented policies the opportunity for fraud increases.

TAFEs generally had policies addressing their key financial processes. However, there were several instances where policies were either deficient or non-existent. This included policies for cash collection, the use of purchasing cards and managing IT user accounts.

6.2.3 Segregation of duties

Sound financial management involves the segregation of key accounting responsibilities to maintain integrity, minimise errors and mitigate the risk of fraud. Functions such as payment of suppliers and employees, or approval of reconciliations should be performed independently by different staff.

Several TAFEs cited staff resourcing shortfalls as the reason behind a lack of segregation of duties. Management must ensure that the risk of poor segregation of duties is mitigated.

6.2.4 Status of prior year issues

Internal control weaknesses reported to management, the governing body and/or audit committee should be actioned and resolved in a timely manner. Sixteen of the 30 internal control weaknesses identified and reported to management at six TAFEs in 2011 or earlier were not resolved by management at the time of the 2012 audits.

While action to address outstanding issues was proceeding on some matters, failure to address previously identified and reported internal control weaknesses reflects poorly on the governing body and management of each of the six TAFEs.

6.3 Internal audit

Internal audit is a key mechanism available to TAFE governing boards to support the discharge of their governance and oversight responsibilities. Internal auditors can review core internal controls and identify areas of risk within an entity, providing assurance to management on the operational effectiveness of key controls. They may also identify and report on deficiencies or control weaknesses that need to be addressed.

An effective internal audit function strengthens internal controls, adding credibility to both the financial and non-financial information produced, as well as improving the efficiency of key controls and processes.

6.3.1 Internal audit framework

The key elements of an effective internal audit function are detailed in Figure 6A. The table draws on the Australian National Audit Office better practice guide Public Sector Internal Audit – an investment in assurance and business improvement, September 2012.

Figure 6A

Key elements of an effective internal audit function

|

Component |

Key elements |

|---|---|

|

Policy |

Policy established and requires an internal audit function to be in place. Internal audit charter is established and sets out:

Policy and charter reviewed by the board. |

|

Management practices |

Comprehensive audit program developed for a minimum three-year period, and directly linked to the entity’s identified risks. Internal audit program:

Reporting to the audit committee is regular and comprehensive. |

|

Governance and oversight |

Audit committee annually reviews internal audit performance and regularly monitors:

Issues register maintained, which details the:

Action taken to address identified issues is monitored by the audit committee and senior management. Internal audit performance reviewed annually by the audit committee, and action taken to address issues identified. Policy and charter reviewed periodically and approved by the board. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

These elements were considered in our assessment of the internal audit function in each of the 14 TAFEs.

Conclusion

Internal audit frameworks across the TAFE sector were generally sound. All had policies in place, and internal audit reported regularly to the audit committee. All TAFEs had internal audit functions that were 'developed' or better, reflecting many of the better practice elements in the framework. Nevertheless, there are opportunities for improvement across the sector in policy content and internal audit coverage of some key business areas.

6.3.2 Policies

Each of the 14 TAFEs had an internal audit policy or charter. The charters contained the majority of better practice elements outlined in Figure 6A.

Across the sector, policies commonly incorporated the following better practice elements:

- details of roles and responsibilities

- clear reporting lines to management and audit committee

- need for operational independence.

However the following better practice elements were not addressed by a number of tertiary education bodies:

- outline of the process for selecting the internal audit service provider

- arrangements for reporting conflicts of interest of internal auditors

- requirements for periodic review.

Reporting internal audit conflict of interest

Policies at five TAFEs had no arrangements for reporting conflicts of interest of internal auditors. Independence is a central characteristic of an effective internal audit function, to maintain integrity and to avoid the appearance of bias.

All TAFE institutes use external service providers. However, it was concerning that six internal audit charters did not address the process for selecting the internal auditors. There is a risk that the internal auditors appointed may not have appropriate qualifications, experience or understanding of the entity required for a quality internal audit function.

Review of policy and charter

Thirty-six per cent of TAFE charters did not include requirements for periodic review of the policy.

6.3.3 Management practices

Management at each of the TAFEs had developed an internal audit program outlining the audit coverage to be achieved, and regularly reported to the audit committee on the status of recommendation implementation.

Internal audit program

Internal audit programs were generally for three years, and included sufficient detail of the work to be completed, costs, resources and links with relevant entity risks.

Programs had clear time lines, identifying key milestones and the reporting date for each audit.

Approval by audit committee

Audit committees at all 14 TAFEs had signed off their respective internal audit program.

6.3.4 Governance and oversight

Reporting to the audit committee

Each of the 14 TAFEs had an audit committee that regularly reviewed internal audit reports. Eleven (79 per cent) also maintained an issues register, populated by internal audit's findings and recommendations.

Follow up of implementation of recommendations

All audit committees followed up internal audit recommendations to monitor their implementation, and to hold management accountable for addressing issues raised.

Periodic review of internal audit arrangements

Only 11 of the 14 TAFEs had reviewed their internal audit arrangements within the past three years. The remaining three should conduct a review of their arrangements in a timely manner in order to identify improvements and maintain alignment with organisational objectives and risks.

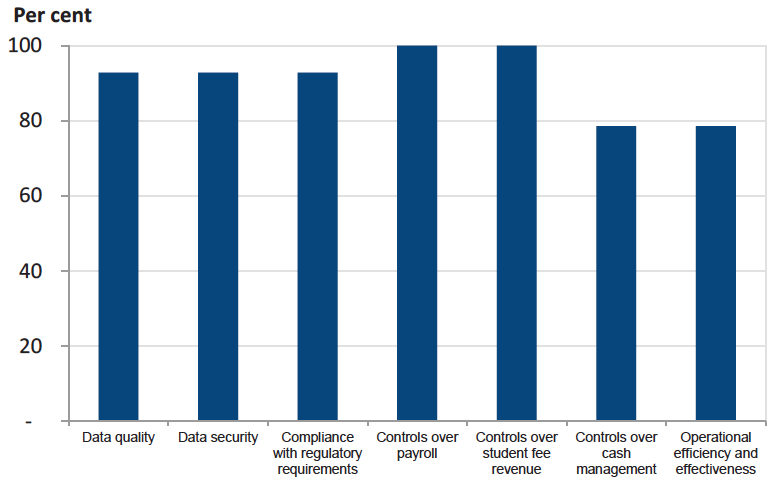

6.3.5 Comprehensiveness of internal audit program

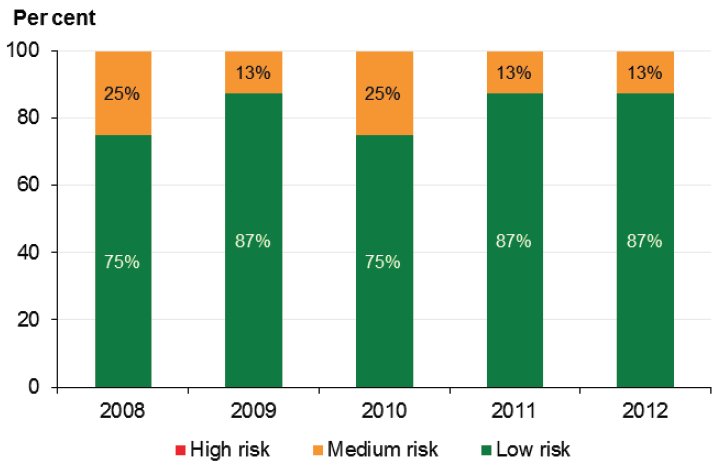

We identified seven key business activities common to the 14 TAFEs, and assessed whether they had been subjected to internal audit scrutiny over the past three years.

Twelve TAFEs achieved coverage over at least six of these activities. The remaining two TAFEs had only reviewed four of the seven activities, indicating that further attention by internal audit is required.

Figure 6B highlights the common key business activities, and the percentage of TAFEs that had addressed them through internal audits.

Figure 6B

Review of internal audit coverage in TAFEs

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Our analysis revealed opportunity for greater coverage of controls over cash management and operational efficiency and effectiveness. These functions had not been reviewed at 21 per cent of TAFEs (three of 14).

The comparatively lower coverage of cash management is concerning, as cash is an item highly susceptible to theft or misuse and is highly portable and difficult to trace. Internal audit scrutiny can help improve the controls in this area and reduce the potential for fraud.

Ineffective or inefficient processes can raise probity issues, expose an entity to reputational risk or lead to waste of public resources. In the tight economic times, internal audit reviews of efficiency and effectiveness can improve business processes and identify savings.

6.4 Purchasing by credit card

Credit cards enable entities to purchase goods and services with reduced administrative costs, greater convenience and flexibility for staff compared to using cash or cheques. However, they can expose entities to the risk of inappropriate or unauthorised expenditure, and are a high fraud risk.

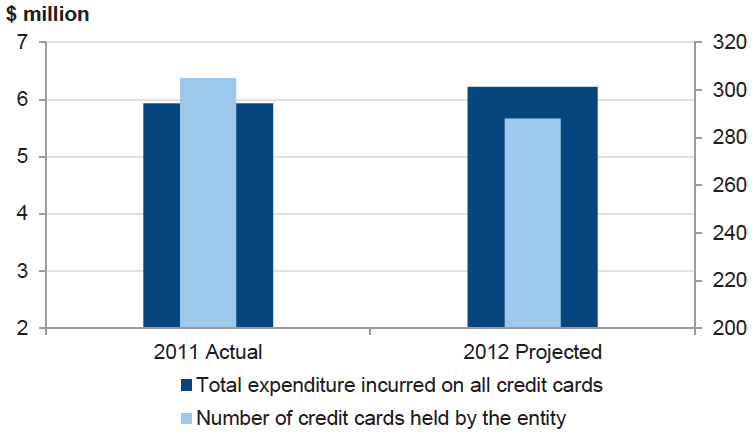

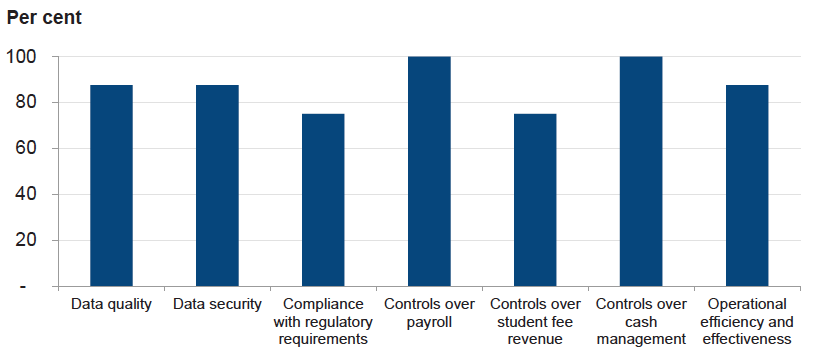

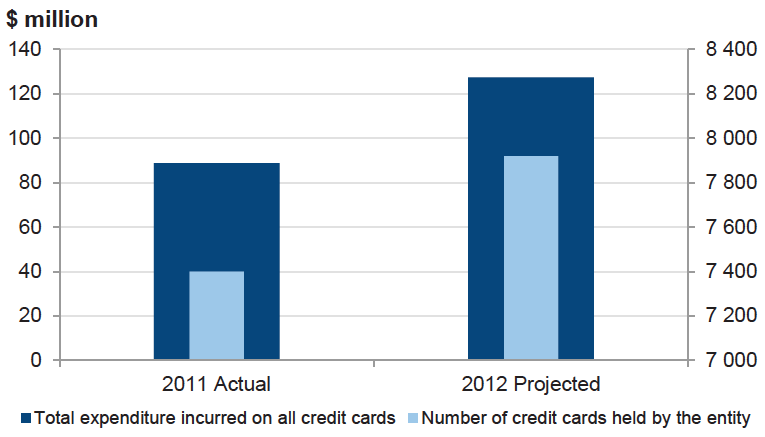

Credit card expenditure for the sector was projected to be $6.2 million in 2012. Figure 6C compares the number of cards on issue across the 14 TAFEs and the expenditure incurred for the past two years.

Figure 6C

Number of credit cards and expenditure incurred, 2011 and 2012

Note: 2012 projected figures were obtained during the course of the 2012 audits.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The overall spend was projected to increase slightly to $6.2 million in 2012 ($5.9 million in 2011). This is consistent with entities' increasing preference for making purchases with credit cards.

However the number of credit cards at TAFEs decreased by 6 per cent in 2012. The scaling back of operations in the TAFE sector due to the changed funding model has resulted in campus closures and staff redundancies, leading to fewer cards.

6.4.1 Credit card framework

Figure 6D outlines the key components of an effective credit card management framework. It draws on the:

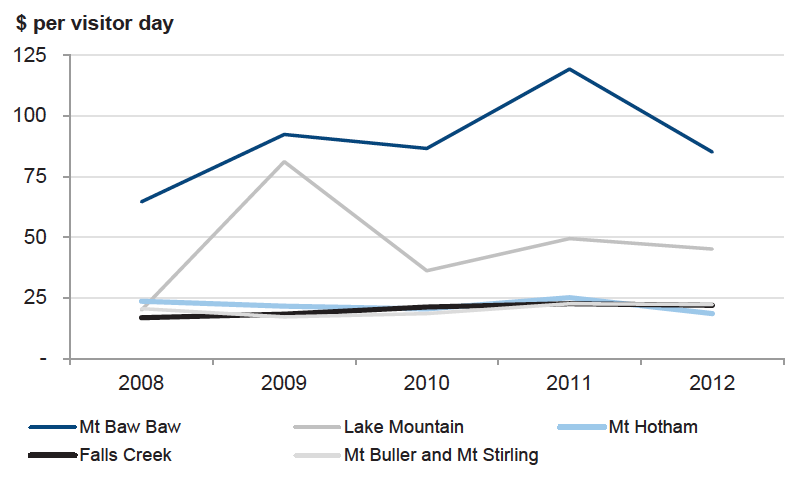

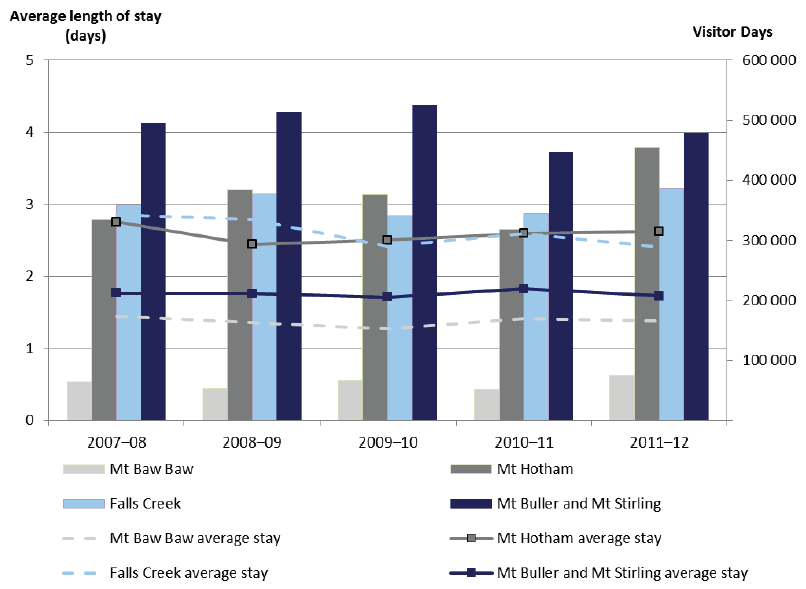

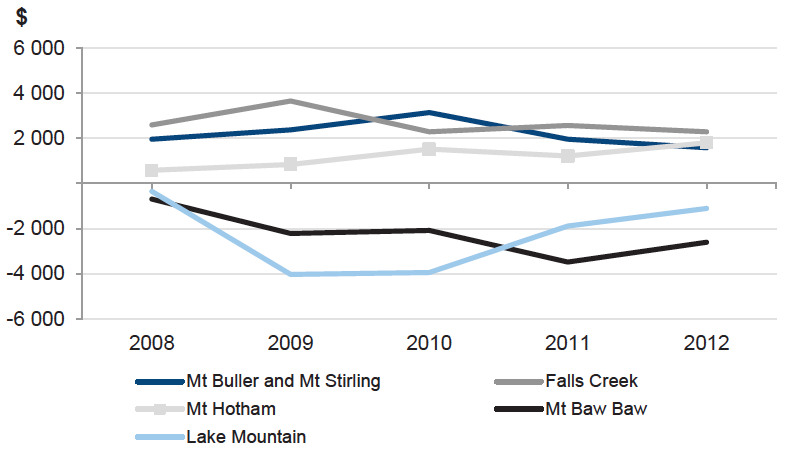

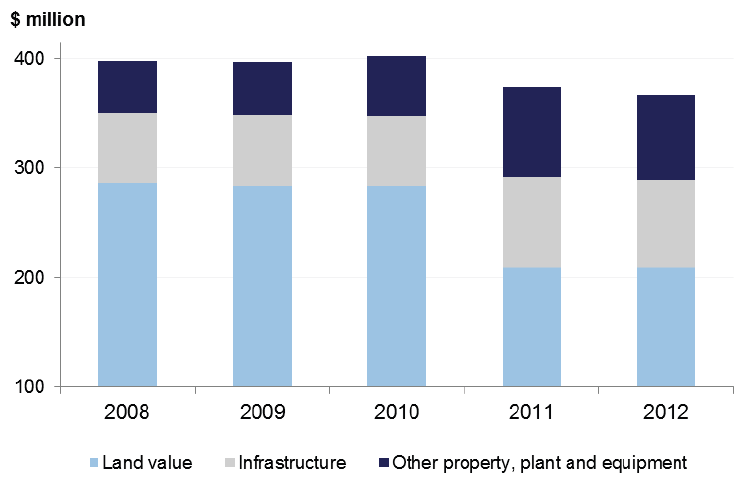

- Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance, ‘Purchasing Card Rules for the Use and Administration’