Government Advertising and Communications

Overview

From July 2006 to December 2010, 11 departments and five agencies spent over $1 billion on advertising and communications.

Government spending on advertising and communications is significant and has grown consistently since 2002. Given the political sensitivity and significance of this annual expenditure, full and fair disclosure of all advertising costs incurred is a critical accountability issue. However, currently, the level of transparency and accountability for government advertising and communications expenditure continues to be inadequate.

Public reporting is partial and inaccurate, and there is inadequate oversight of government advertising activities. Estimated total expenditure exceeds publicly reported costs by up to 97 per cent.

The Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) has not adequately monitored and overseen advertising and communications activities across government. It has not provided clear leadership and guidance, and departments and authorities are not complying with advertising and communications guidelines, particularly in such areas as evaluation and sponsorship.

DPC has not effectively managed the major advertising and communications contracts. It has not been able to demonstrate that value-for-money has been achieved, nor that the quality of services acquired has been adequate.

While the 2009 Victorian Government Advertising and Communications Guidelines (2009 Guidelines) are comparable with those in other jurisdictions, there is obvious scope for improved transparency of and accountability for this significant and contentious element of taxpayer funded expenditure.

A compliance assessment of five advertising campaigns shows general compliance with the 2009 Guidelines. There were, however, notable breaches that departmental oversight processes failed to identify.

Government Advertising and Communications: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER February 2012

PP No 105, Session 2010–12

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Government Advertising and Communications.

Yours faithfully

![]()

D D R PEARSON

Auditor-General

29 February 2012

Audit summary

Background

Victorians have the right to be informed about tax-payer funded policies, programs and services. The government uses advertising and communications as key tools to provide this information.

While advertising and communications can assist in efficiently achieving government objectives to inform the public, they often attract controversy and political debate, mainly over the level of public funds used and their potential to be used for party political purposes.

Government advertising and communications activities need to be accountable, to offer value-for-money and to avoid promoting the incumbent government.

This audit examined:

- whether there are appropriate levels of accountability in government advertising and communications expenditure and processes

- whether selected advertising and communications campaigns comply with relevant laws, guidelines and policies

- how the 2009 Victorian Government Advertising and Communications Guidelines (2009 Guidelines) compare with current better practice.

Conclusions

At an estimated $257 million for 2009–10, government spending on advertising and communications is significant and has grown consistently since 2002. Given the political sensitivity and significance of this annual expenditure, full and fair disclosure of all advertising costs incurred is a critical accountability issue. Currently, however, the level of transparency and accountability for government advertising and communications expenditure continues to be inadequate.

Public reporting is partial and inaccurate, and there is inadequate oversight of government advertising activities. Estimated total expenditure exceeds publicly reported costs by up to 97 per cent.

The Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) has not adequately monitored and overseen advertising and communications activities across government. It has not provided clear leadership and guidance, and departments and authorities are not complying with advertising and communications guidelines, particularly in such areas as evaluation and sponsorship.

DPC has not effectively managed the major advertising and communications contracts. It has not been able to demonstrate that value-for-money has been achieved, nor that the quality of services acquired has been adequate.

While the 2009 Guidelines are comparable with those in other jurisdictions, there is obvious scope for improved transparency of and accountability for this significant and contentious element of tax-payer funded expenditure.

A compliance assessment of five advertising campaigns shows general compliance with the 2009 Guidelines. However, there were notable breaches that departmental oversight processes failed to identify.

Findings

Expenditure and reporting

From July 2006 to December 2010, 11 departments and five agencies spent over $1 billion on advertising and communications. Each year expenditure increased.

The annual expenditure for these 16 entities was at least $183 million in 2006–07, $188 million in 2007–08, $220 million in 2008–09, $257 million in 2009–10, and $152 million for the six months to 31 December 2010.

Nielsen’s Media Research reported that in both 2009 and 2010, the Victorian Government was the largest advertiser in this state, and the seventh largest in Australia. It spent more than all other state governments and some major commercial corporations, and only a fraction less than the federal government over the same period.

Reliability and integrity of reporting

There is no central collation and reporting of the full costs incurred across government.

DPC publishes annual media costs. However, there is a significant difference between ‘direct’ media costs and the full costs associated with advertising and communications activities.

In 2008 the then government decided to reduce expenditure by 10 per cent. This was not achieved either in real or reported terms. Media spending continued to increase. Published media costs were artificially lowered by reporting net spending, after application of a 10 per cent media rebate, rather than the gross amount.

Contrary to requirements, fewer than half the advertising campaigns approved and completed in 2008–09 and 2009–10 were evaluated, and of these under 10 per cent were submitted to the government advertising and communications committees.

Again contrary to requirements, from 2006–07 to 2009–10, less than 12 per cent of sponsorships by the 16 audited agencies were listed in the DPC Sponsorship Register, and only six of the 11 departments sent sponsorship information to the register.

For the period of the audit, DPC had no system to monitor actual media spend against approved budgets. This means that that there is no assurance that actual expenditure on individual campaigns is within budget.

Cost monitoring by entities

Tourism Victoria, the Transport Accident Commission, the Transport Ticketing Authority, VicRoads and WorkSafe keep relevant and easily accessible data on their advertising and communication expenditure. The Departments of Justice and Treasury of Finance are also reasonably placed to provide this information.

This was not the case for the other departments.

Contract management

DPC has not effectively managed the contracts for the Master Agency Media Services, the Print Management Services and the Marketing Services Panel.

It did not assess whether these contracts achieved their objectives, and its monitoring of expenditure against the contracts was poor. Further, DPC did not independently verify expenditure data submitted by service providers. DPC had to revise its publicly reported 2009–10 media placement expenditure, from $124 million to $130 million, after the inaccurate reporting was identified.

2009 Guidelines – compliance and better practice

DPC does not monitor the interpretation and application of the 2009 Guidelines or other advertising and communications guidelines and policies. As a result, there is no common awareness and understanding of their coverage and applicability.

Better practice

The 2009 Guidelines do not reflect developments in better practice since 2009. They can be improved to give clearer guidance and direction to increase transparency and accountability in advertising and communications activities across government.

There was no requirement or system in place to have a strategic and integrated approach across government for advertising campaign applications.

There was insufficient documentation to allow the assessment of advertising applications to be independently verified. There is therefore limited assurance that approved campaigns were consistent with government priorities, or that opportunities to leverage messages and achieve cost savings were maximised.

Whole-of-government communications strategy

DPC does not have a system in place to facilitate a coordinated advertising and communications strategy across government. This means that there is limited assurance that cost savings are realised, contradictory messages are minimised, and opportunities to leverage messages are maximised.

At the entity-level, however, Tourism Victoria, the Transport Accident Commission and WorkSafe have annual campaign advertising plans which enable the effective scheduling of activities throughout the year, streamline the messages delivered to the public and deliver significant cost and procedural efficiencies.

Compliance assessment

One advertising campaign reviewed included elements that could be perceived as serving party political interests. Another campaign presented information that was neither accurate nor verifiable.

Recent developments

However, in the second half of 2011 DPC has worked to improve its management of the Master Agency Media Services contract and oversight of advertising and communications activities across government. This is a positive initiative for which momentum should be maintained. This should also be extended to other aspects of DPC’s role – particularly with respect to transparency and accountability in advertising and communications activities across government.

Recommendations

-

The Department of Premier and Cabinet should:

- make total advertising and communications expenditure publicly available

- require an acquittal of campaign expenditure against approved budgets

- educate applicable parties on relevant guidelines, and monitor compliance

- improve its management of the Master Agency Media Services contract.

-

Departments and agencies should:

- introduce rigorous business operations processes to enable consistent and accurate reporting of advertising and communications expenditure

- publish details and costs of advertising campaigns and sponsorships provided and received

- comply with all relevant advertising and communications policies and guidelines.

-

The Department of Premier and Cabinet should:

- revise the 2009 Victorian Government Advertising and Communications Guidelines in line with current better practice

- develop and annually revise a whole-of-government communications strategy.

-

Departments and agencies should:

- have their chief executive or responsible officer certify that their advertising campaigns were developed independent of any intention to benefit a political party or minister, and that they comply with relevant advertising and communications guidelines with objective evidence

- have rigorous oversight processes for finalising advertising campaign materials to assure compliance with the 2009 and subsequent guidelines, prior to publication.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the 11 departments and five agencies included in the audit with a request for comments or submissions.

Department and agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments, however, are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Advertising and communications activities are increasingly being used by governments to achieve their objectives in informing the public. However, these activities often attract controversy and political debate over the levels of public funds used and the potential for advertising to be used for party political purposes.

Government advertising and communications activities need to be accountable, to deliver value-for-money and to avoid promoting the incumbent government.

1.2 Advertising and communications

The term ‘communications’ in this context covers the planning, development and delivery of government messages through a mix of strategies to inform the public about tax-payer funded policies, programs, products and services.

A government can reasonably communicate with the public to:

- inform about laws and policies, and maximise public compliance

- ensure public safety, personal security or encourage responsible behaviour

- help preserve order in a crisis or emergency

- promote awareness of rights, responsibilities, duties or entitlements

- encourage use of, or familiarity with, government products or services

- report on government performance

- inform the public that the state is a good place to live, visit, study, work or invest

- encourage social cohesion, civic pride, community spirit, tolerance, or help achieve a widely supported public policy outcome.

Governments communicate this information through strategies such as:

- advertising

- media relations and announcements

- publications

- websites, including social media and mobile phone applications

- sponsorships and promotional partnerships

- events and exhibitions

- information programs and education campaigns.

Although each strategy is different, in practice they often occur jointly. For example, some television advertising campaigns are supported by printed brochures for the public to conveniently pick up and consider. Also, government sponsorship of a sporting event may coincide with government advertising that airs during the television broadcast.

1.2.1 Advertising

Advertising is done through television and radio, the internet, outdoor and print media, and/or direct mail, among a range of mediums. It is designed to draw attention to a government policy, a publicly‑funded product or service, or to inform about laws, rules and regulations. The aim is to directly or indirectly promote them—for example, in the case of a government service or a venue—or to discourage behaviour such as smoking or irresponsible driving.

As government uses increasingly diverse media, the traditional idea of advertising as paid media placements is no longer necessarily valid. Further, the use of social media can expand the ways advertising campaigns reach the public.

Campaign, functional or recruitment advertising

The government categorises advertising activities as either campaign, functional or recruitment advertising.

Campaign advertising aims to influence or change the perception, behaviour or attitudes of the general public and is mid to long term. It may use highly creative content from an advertising agency or graphic designer.

Functional advertising refers to direct and unembellished public, legal or emergency notices, road closures, tenders, calls for submissions, auctions, and the promotion of lectures/training seminars.

Recruitment vacancy advertising seeks to fill specific vacancies in the Victorian public service. However, advertisements that seek to influence the perception of a specific career sector or job opportunity are considered to be campaign advertising.

1.3 Advertising and communications guidelines

In June 2002, the Auditor-General recommended that the government develop criteria for assessing its advertising and communications. In October 2002, the government published the Guidelines for Victorian Government Advertising and Communications.

In September 2006, the Auditor-General recommended the 2002 guidelines be reviewed to detail more explicit guidance on the appropriate use of public funds. In response to this and increasing public criticism of several advertising campaigns, the government adopted the Victorian Government Guidelines for Advertising and Communications in December 2009 (2009 Guidelines).

1.3.1 2009 advertising and communications guidelines

The 2009 Guidelines are the overarching policy on external government communications. They state that ‘all [of government’s] communications with Victorians’ must be ‘equitable, fair, appropriate and accountable’. The 2009 Guidelines require government advertising and communications activities to be:

- relevant to government responsibilities

- not intended to promote party political interests

- not excessive or extravagant in relation to the objective

- based on accurate and verifiable facts.

They explain that the perception of promoting party political advantage could arise from factors such as the:

- content of the material—what is communicated

- source of the material—who communicates it

- reason for the campaign—why it is communicated

- purpose of the campaign—what it is meant to do

- choice of media—how, when and where it is communicated

- timing, geographic or demographic targeting of the campaign

- effect it is designed to have.

The 2009 Guidelines also require clear accountability and appropriate auditing for advertising and communications activities.

1.3.2 Advertising approval process

The Department of Premier and Cabinet’s (DPC) Victorian Government Advertising and Communications Approval Process details the mandatory approval process for campaign advertising. DPC prepared separate guides for:

- departments including administrative offices and the State Services Authority

- public entities as defined in the Public Administration Act 2004

- special bodies such as Victoria Police, Parliament, the Ombudsman, and the Office of Police Integrity.

Approval process for campaigns under $50 000

Applications with a proposed media expenditure under $50 000 require only the endorsement of the relevant senior communications officer within each department or agency, who certifies that the application complies with the 2009 Guidelines. Once an authorisation number is issued the agency may proceed with the campaign.

Approval process for campaigns $50 000 and over

In addition to the relevant senior communications officer’s endorsement, applications with a proposed media expenditure of over $50 000 require the departmental secretary or agency chief executive officer’s endorsement.

The completed application form is forwarded to DPC, which either forward the application to the cabinet committee for final approval or request more information.

Approval process – no cost threshold

Campaign advertising applications from special bodies, regardless of the cost, require only the approval of the authorised officer who certifies compliance with the 2009 Guidelines.

Similarly, functional and recruitment advertising applications, regardless of cost, require only the endorsement of the relevant senior communications officer.

1.3.3 Other policies and guidelines

Other polices and guidelines on advertising and communications include:

- Guidelines on the Caretaker Conventions

- Sponsorship Policy

- Branding Policy and Guidelines

- Multicultural Communications Policy

- Regional Communications Policy

- Gender Portrayal Guidelines

- External Communications Access Policy

- Website Guidelines

- Evaluation Guidelines.

1.4 Responsibility for advertising and communications

There are a range of administrative arrangements across government and public sector agencies for the management and coordination of advertising and communications activities.

Communications Committee of Cabinet

Set up in 2000, the Communications Committee of Cabinet (CCC) oversaw and directed government advertising and communications by:

- considering regular reports on government communications activity, expenditure and outcomes

- establishing and reviewing whole-of-government guidelines and policies

- considering reports on key projects, communication innovation, market research and campaign strategies.

From 2006 to 2010, the CCC met monthly to consider and approve campaign advertising applications with a proposed media spend of over $50 000. The CCC was dissolved before the November 2010 elections. A new committee, the Advertising and Communications Committee was set up in April 2011.

Communications Executive Sub-committee of Cabinet

The Communications Executive Sub-committee of Cabinet (CESC) was set up in 2008 as a three-member sub-committee of the CCC. It was authorised to approve urgent but uncontentious campaign advertising applications when Parliament was not sitting. Like the CCC, the CESC was dissolved before the November 2010 elections. There is no longer an equivalent sub-committee to the Advertising and Communications Committee.

Department of Premier and Cabinet

DPC oversees whole-of-government advertising and communications activities and expenditure. Its roles include:

- developing whole-of-government strategies and policies

- providing advice and secretariat services to the former CCC and CESC and now the Advertising Communications Committee

- chairing the former Government Communications Review Group

- managing advertising and communications state purchase contracts

- advising departments and agencies

- monitoring government coverage in radio and television media (media monitoring)

- monitoring compliance with guidelines and policy directions.

Government Communications Review Group

Set up in 2004, the Government Communications Review Group oversaw and directed communications and advertising activities across government. A DPC Director chaired the group, which included two representative senior communications officers from within departments. Each of the ten departments was represented on a rotating basis.

The group was dissolved in April 2011.

Its terms of reference required it to:

- assist with developing communication themes and identifying opportunities for consolidation and rationalisation of communications activities across government

- determine advertising campaign applications suitable for submission to government

- monitor major market research activities

- report monthly to the government on the status and resource implications of each activity

- manage and monitor departmental activities by guiding strategy development and monitoring implementation and evaluation.

In helping the government determine suitable and appropriate campaign applications, the Government Communications Review Group was expected to advise on:

- how relevant, achievable and measurable the objectives were

- how well the campaign supported government priorities, themes and messages

- the priority given to the campaign

- how effectively the campaign strategy addressed the objectives

- how effectively the evaluation of the campaign outcomes had been planned

- whether there had been similar or related activities before, and if so, their outcomes

- whether the campaign complied with all applicable government guidelines.

Departments and agencies

Heads of departments and agencies are responsible for managing their own advertising and communications.

Communications units handle the day-to-day management of communications and advertising. They liaise with DPC for advice and direction, including, but not limited to, approving advertising campaigns.

The communications units of the five agencies reviewed for this audit, Tourism Victoria, the Transport Accident Commission, the Transport Ticketing Authority, VicRoads and WorkSafe, centrally manage all advertising and communications activities. The boards of directors of Tourism Victoria, the Transport Accident Commission and WorkSafe approve their annual budgets and communications plans before submission to the government.

In most departments, advertising and communications activities are coordinated centrally, but the budget and need for specific campaign or communications activities are identified and approved within business units or program areas.

1.5 Purchasing advertising and communications

A whole-of-government approach for the procurement of advertising and communications services is in place through State Purchase Contracts. The aim is to improve value-for-money and promote continuous improvement in services during the contract term.

1.5.1 Master Agency Media Services

The Master Agency Media Services contract purchases media placement for campaign, recruitment and functional advertising. All departments, agencies, entities and special bodies must use this contract. DPC is the contract manager.

The Master Agency Media Services contracts are expected to benefit the public through:

- discounted, competitive advertising rates

- potential cost savings of at least $155.5 million over the contract term

- savings and added value of up to $32 million over the contract term

- comprehensive reporting for the effective management of contract outcomes

- improved capability to report on and monitor client spend.

1.5.2 Market Services Panel

The Market Services Panel (MSP) comprises 78 pre-qualified advertising and communications service providers. All departments must use the panel. Agencies and other public bodies may request permission to use the panel from the MSP contract manager.

Benefits expected from MSP include:

- lower government transaction and administration costs

- better accountability and governance through improved coordination, monitoring and reporting of all departmental expenditure.

DPC was the MSP contract manager from 2005 until December 2009, when the Department of Treasury and Finance took over.

1.5.3 Print Management Services

Print Management Services (PMS) appoints a provider to coordinate and manage the sourcing and delivery of government printing. All departments, Victoria Police, the State Services Authority and special bodies are mandated to use PMS. The expected benefits include:

- better efficiency in engaging and managing suppliers

- improved accountability and reporting on printing expenditure

- a centralised category management framework.

DPC was the contract manager for PMS until December 2009 when management transferred to Department of Treasury and Finance.

1.6 Audit objective and scope

The audit examined whether government advertising and communications activities for the period July 2006 to December 2010 complied with relevant guidelines, directions and policy documents.

The audit examined all 11 departments and five agencies; Tourism Victoria, the Transport Accident Commission, the Transport Ticketing Authority, VicRoads and WorkSafe. It also evaluated five campaigns for compliance with relevant guidelines: Transport Plan, Blueprint for Regional Victoria, CityGT, Locusts, and Musculo-skeletal Disorders.

1.6.1 Audit approach

To address this, the audit assessed:

- whether there are appropriate levels of accountability in government advertising and communications expenditure and processes

- whetherselected advertising and communications campaigns comply with relevant laws, policies and guidelines

- how the 2009 Victorian Government Advertising and Communications Guidelines compares with current better practice.

The audit was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. The total cost of this audit was $470 000.

2 Expenditure and accountability

At a glance

Background

Advertising and communications are accepted means by which governments make known or explain their policies, programs or services. However, the important role they play is easily compromised when public resources are spent with little accountability, or when they serve party political purposes rather than the public good.

Conclusion

Despite advertising expenditure of around $1 billion between July 2006 and December 2010, there is little assurance that advertising and communications have achieved their objectives, that the quality of services has been adequate, or that expenditure represents value-for-money. Assurance has been further diminished because public sector entities have not adequately evaluated their advertising and communications activities.

Findings

- From 2006 to 2010 departments and agencies spent more than $1 billion on advertising and communications.

- There is no central collation and reporting of the full costs incurred across government.

- The Department of Premier and Cabinet does not monitor actual media spend against approved budgets for advertising campaigns.

- There is poor compliance with advertising and communications policies such as sponsorship and evaluation policies.

- The Department of Premier and Cabinet does not effectively manage the state purchase contracts.

Recommendations

The Department of Premier and Cabinet should:

- make total advertising and communications expenditure publicly available

- educate applicable parties on relevant guidelines, and monitor compliance.

Departments and agencies should monitor and disclose advertising and communications spending data and comply with relevant advertising and communications policies and guidelines.

2.1 Introduction

Advertising and communications are accepted means by which governments make known or explain their policies, programs, products or services. However, the important role they play is easily undermined by suggestions that excessive public resources are spent with little accountability, or that they serve party political purposes rather than the public good.

The Victorian Government is a significant purchaser of advertising and communications, ranking seventh in Australia and first in Victoria in 2009 and 2010, based on spending on media costs.

2.2 Conclusion

Despite advertising expenditure of around $1 billion between July 2006 and December 2010, there is little assurance that advertising and communications have achieved their objectives, that the quality of services has been adequate, or that expenditure represents value-for-money.

This is because the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) has not provided clear leadership and guidance, and has not appropriately monitored and overseen advertising and communications activities across government.

Assurance has been further diminished because public sector entities have not adequately evaluated their advertising and communications activities.

2.3 Cost of advertising and communications

As a way to provide transparency and accountability around advertising and communications expenditure, DPC publicly reports annual media purchasing or placement expenditure across government. However, this information is limited and does not reflect full advertising and communications costs.

2.3.1 Publicly reported costs

DPC only reports the direct costs incurred through the Master Agency Media Services contract. This represents media purchasing or placement costs.

There is a significant difference between the reported costs and the estimated total cost incurred on advertising and communications activities. While it is common commercial advertising practice to report only on the media component, from a public expenditure perspective this reporting is inadequate.

Media costs, as reported, do not include related costs for market research, design, creative work, graphics, production, printing and distribution. They also do not include costs associated with:

- media monitoring

- public and media relations

- sponsorships

- partnerships

- fairs and exhibitions

- website development, hosting and maintenance

- salaries and travel expenses of public servants involved.

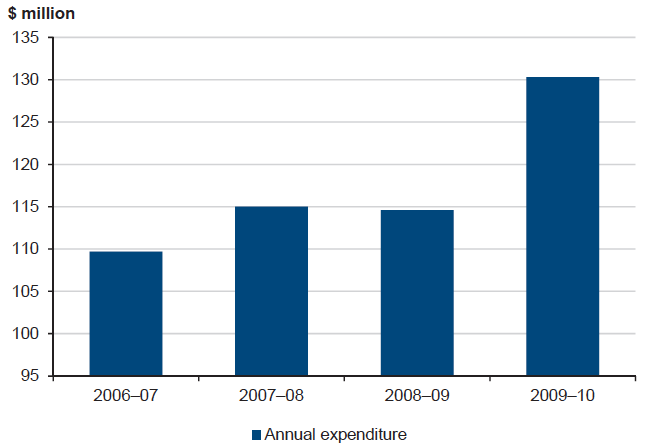

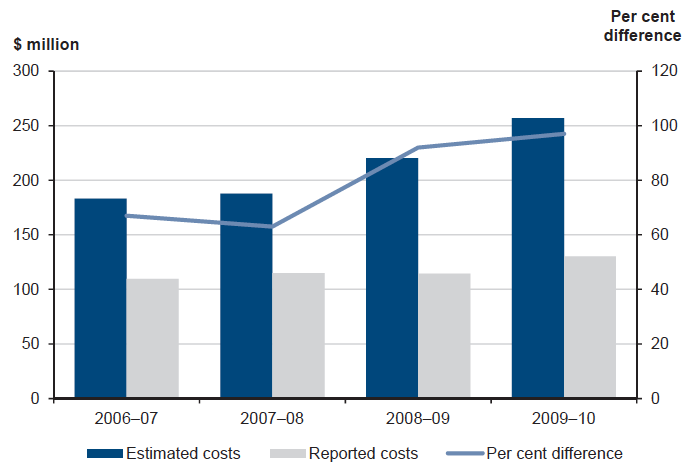

Figure 2A shows the publicly reported spending on advertising media placements since 2006–07.

Figure 2A

Media placement costs, 2006–07 to 2009–10

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office, based on the Department of Premier and Cabinet's Master Agency Media Services expenditure.

The data shows that between 2006–07 and 2009–10, expenditure on media costs was around $470 million. It increased 18.7 per cent from around $109.7 million to around $130.3 million. Significantly, the largest increase in expenditure occurred in the year leading up to the 2010 state election, with an increase of just over $15 million, or 13.7 per cent, from the previous year.

2.3.2 Estimated actual costs

There is no central record of the full cost of advertising and communications expenditure across the whole-of-government. There is also no system in place for this information to be efficiently and reliably collected.

In 2006, the Auditor-General estimated that the Victorian Government's advertising and communications expenditure was at least $123 million for 2002–03, $147 million for 2003–04, $161 million for 2004–05, and $88 million for the six-month period to 31 December 2005.

To get an indication of current total expenditure for advertising and communications, we obtained data from the 11 departments and five agencies reviewed in the audit. Based on the information provided, we estimated that the full cost of advertising and communications across government could be between 63 per cent and 97 per cent more than the reported direct media costs. Figure 2B compares the estimated actual adverting and communications costs and the reported costs, along with the percentage difference.

Figure 2B

Estimated actual advertising and

communications expenditure versus reported media costs, 2006–07 to

2009–10

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure 2B shows that between 2006–07 and 2009–10, estimated actual expenditure was around $849 million; nearly $400 million more than the reported media costs.

In addition, a further estimated $152 million was spent between July and December 2010. This brings the total estimated actual expenditure to over $1 billion for the period July 2006 to December 2010.

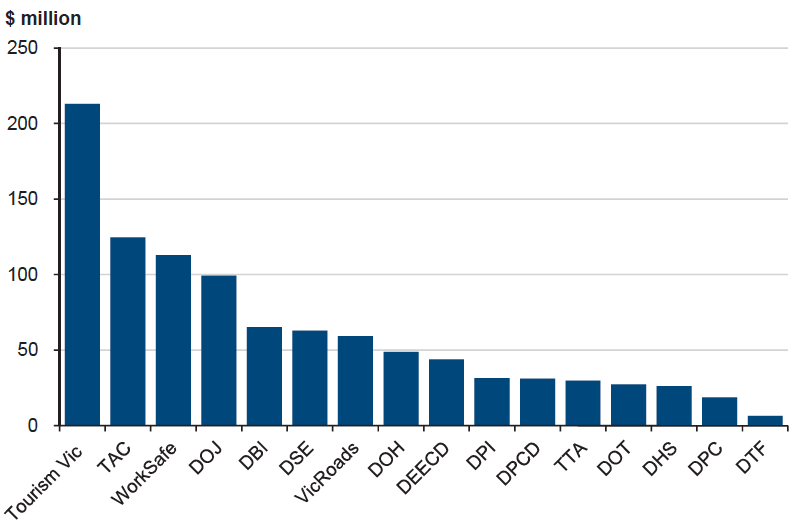

Expenditure across the public sector agencies included in this audit varies and reflects the role of specific agencies. As Figure 2C shows, Tourism Victoria was the biggest spender over the four years, followed by the Transport Accident Commission, WorkSafe and the Department of Justice.

Figure 2C

Estimated actual spend, 2006–07 to 2009–10 and six months to

December 2010

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Around 25 per cent of Tourism Victoria's expenditure was allocated to major events sponsorship such as the Grand Prix and the Australian Open. Government documentation confirms that this expenditure is of the nature of advertising and communication spending inasmuch as the objectives are to:

- increase the number of interstate and international visitors to generate significant tourism and economic benefits for Victoria

- promote Melbourne and Victoria through national and international broadcast of these events

- reinforce Melbourne's reputation as the world's cultural capital, ultimate sports city, etc

- showcase the world-class infrastructure in Victoria.

Through these major events, the government gains significant exposure in overseas television markets through prime advertising spots, in-flight television packages, international events, news and features, etc.

Even though some part of this funding is used for operational expenses by the sponsored organisations, e.g. Tennis Australia, it remains that the primary purpose for the expenditure is to promote Victoria as a prime venue for these major events, as well as a major tourism destination.

2.3.3 Cost breakdown

The estimate of full costs is based on data from the 16 audited entities, which provided their actual or estimated expenditure on:

- advertising—including media placement, creative, graphics, production, distribution, market research, evaluation, printing costs etc.

- sponsorships

- trade fairs and exhibitions

- associated direct salary and travel costs

- other activities such as websites, translations and other marketing and public relations costs.

Figure 2D shows the estimated costs for advertising and communications by category. Advertising is the largest category, representing between 50 and 65 per cent of the total. Staff and travel costs are the next largest item, followed by sponsorships and trade fairs/exhibitions. The number of permanent and contracted public servants engaged in advertising and communications rose from an estimated 485 in 2006–07 to 651 in 2009–10, adding to the costs in this category.

Figure 2D

Advertising and communications costs, 2006–07 to 2009–10 ($

million)

2006–07 |

2007–08 |

2008–09 |

2009–10 |

Jul–Dec 2010 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Advertising |

120.5 |

120.6 |

144.5 |

167.1 |

80.9 |

Sponsorships |

10.8 |

15.7 |

16.6 |

21.0 |

35.5 |

Trade fairs and exhibitions |

4.6 |

3.5 |

4.2 |

4.6 |

3.1 |

Staffing costs and travel |

39.2 |

41.7 |

47.8 |

54.4 |

30.1 |

Other |

8.2 |

6.5 |

7.2 |

9.8 |

3.0 |

Total |

183.3 |

188 |

220.3 |

256.9 |

152.6 |

Note: Advertising covers media placement costs and, where agencies had the figures, market research, creative, production, distribution and evaluation costs.

Note: Although advertising-related printing was the main printing cost, it was excluded from the 'Advertising' category as not all entities could isolate it from non-advertising printing.

Note: Other covers printing, translation services, photography and website development and hosting, as well as other external communications costs.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

2.3.4 Reducing advertising expenditure

In February 2008 the government committed to reduce advertising spending by 10 per cent, and approved three measures to achieve this:

- change what was publicly reported from gross expenditure to net—that is, removing the 10 per cent media rebate from the publicly reported costs

- consolidate government public notices into composite full page advertisements

- transition to an internet-based recruitment strategy and consolidate the multi‑paged job advertisements into weekly one or two page advertisements directing people to the online job website.

The intended reduction was not achieved either in real or reported terms. Media spending continued to increase. The approved first strategy artificially lowered published media costs by reporting net rather than gross spending. This means that, although reported expenditure appears to stabilise during 2007–08 and 2008–09 at around $115 million, the net cost actually continued to rise from $101 million in 2006–07 to $106.5 million in 2007–08 and $114.5 million in 2008–09. There was a significant jump to $130.3 million in 2009–10. This is shown in Figure 2E.

Figure 2E

Net media placement costs ($ million)

2006–07 |

2007–08 |

2008–09 |

2009–10 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Published costs |

109.7 |

115.0 |

114.6 |

130.3 |

Net cost, less 10 per cent rate |

101.5 |

106.5 |

114.6 |

130.3 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Department of Premier and Cabinet documents.

DPC efforts to implement the second and third strategies to decrease actual advertising expenditure met with limited success. Although expenditure on recruitment and functional advertising fell by a total of $5.2 million from 2006–07 to 2009–10, campaign advertising increased by $26.3 million during the same period.

This means that instead of achieving a decrease in spending, total media cost increased by $20.1 million from 2006–07 to 2009–10.

2.4 Accountability for expenditure

Given the significant amounts of public money spent on government advertising and communications, strong accountability mechanisms are required to assure both Parliament and the community that agencies are using this money effectively, efficiently and economically.

DPC guidelines and processes aimed at providing accountability have significant weaknesses that diminish assurance. The weaknesses identified relate to data collection and monitoring, controls around advertising budgets, evaluation of advertising and communications activities and registration of sponsorships.

2.4.1 Cost monitoring by entities

There is no requirement for public sector departments and agencies to monitor and disclose advertising and communications costs. This means that not all agencies have adequate systems and processes in place to record this information and, consequently, accurate and reliable expenditure data were difficult to obtain. The only way to approximate actual expenditure at the whole-of-government level was to request and collate data from each department and agency.

The audit found that the five statutory authorities: Tourism Victoria, the Transport Accident Commission, the Transport Ticketing Authority, VicRoads and WorkSafe, keep relevant and easily accessible data on their advertising and communications expenditure. The Department of Justice and the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) are also reasonably placed to readily provide expenditure information.

However, this was not the case, for the other departments. There were difficulties in obtaining their expenditure data as these costs were often embedded in other program costs. This means that they are not always capable of being isolated from other operational costs. Moreover, in departments with a decentralised advertising and communications function, expenditure data is held in program areas and not centrally aggregated across the department.

Data provided to the audit team often did not match that provided by state purchase contract managers and changed considerably over the course of the audit.

2.4.2 Actual versus approved budget

DPC oversees the approval of advertising campaign applications. However, once the government grants approval, DPC does not monitor actual media spend against the approved budget.

DPC does not require departments and entities to acquit actual expenditure against approved budgets. It also does not require the Master Agency Media Services (MAMS) provider to monitor or report on the amount of media purchased against each client's approved media placement budget.

This means that DPC is exercising no oversight of whether actual expenditure is confined within approved spending levels. As a result the system offers little incentive for departments and entities to keep within the approved budget.

Furthermore, departments do not have sound internal processes to monitor whether advertising spending is being kept within approved budgets. One department does not keep track of its advertising campaign expenditure and had to ask the MAMS provider for the information.

Approved media placement cost below $50 000

Unlike advertising campaigns with proposed media cost over $50 000, which require government approval, those with a proposed spend below $50 000 only require DPC authorisation.

This audit found instances where actual expenditure exceeded $50 000 on advertising campaigns that were authorised for below this amount. As a result, these campaigns were not subjected to the more rigorous government approval process that campaigns over the $50 000 threshold are required to undergo.

For the period of the audit, DPC has no system in place to identify whether the government approval process is being deliberately circumvented.

2.4.3 Evaluations

The Evaluation Guidelines developed by DPC in 2004 state that the government 'values the assessment of the degree to which objectives have been met as a result of the communications activity,' and for this reason, evaluation must be 'an integral part' of all communications activities.

Departments and agencies must submit evaluation reports to the government at the completion of advertising or communications activities with the evaluation budget factored in at the planning stage.

However, of the more than 700 advertising campaigns approved in the four years to 2010, fewer than 25 evaluation reports were submitted to government upon completion of the activity.

Additionally, fewer than half the approved campaigns from 2008–09 and 2009–10 were evaluated by the departments and agencies. There is therefore very little assurance that costly advertising and communications activities achieved their objectives or that the most cost efficient methods were used.

DPC does not have a framework in place to monitor and enforce compliance with the Evaluation Guidelines.

Focus of evaluations

In general, the evaluations provided to government did not report on outcomes or the achievement of objectives, but rather on the frequency of campaign recall. While audience reach and frequency of campaign recall are relevant contextual measures of advertising campaign success, entities paid little attention to their overall impact and effectiveness.

Furthermore, none of the 25 evaluation reports considered the cost-effectiveness of the campaigns or acquitted actual costs against those approved.

DPC should work at enhancing the quality and relevance of evaluation reports so that they assess:

- achievement of all objectives

- the cost-effectiveness of the campaign

- whether actual costs are within the approved budget.

2.4.4 Sponsorships

The Victorian Government Sponsorship Policy (Sponsorship Policy) defines sponsorship as the 'purchase of rights or benefits delivered through association with the sponsored organisation's products, services or activities'. Examples include the sponsorship of events or specific activities of peak industry bodies.

The Sponsorship Policy requires all sponsorships received or provided by departments, administrative bodies, statutory authorities, government corporations and all other entities to be:

- registered in the Government Sponsorship Register administered by DPC

- evaluated upon completion

- publicly reported in Budget papers, annual reports or other performance reports.

The rationale for registration is to allow the monitoring and tracking of expenditure, and the identification of opportunities for collaboration in seeking or providing sponsorships as well as conflicts or duplication of sponsorships.

In the four years to 2009–10, the 11 departments and five agencies audited spent over $100 million on sponsorships.

We found that under 12 per cent of government sponsorships in the four years to 2009–10 were listed in the register. Six of the 11 departments and none of the statutory authorities had entries in the register. Contrary to requirements, there were no entries on sponsorships received.

The 11 departments explained that they are aware of the Sponsorship Policy, but did not consistently apply it. The five statutory authorities made up nearly 89 per cent of sponsorship expenditure, however, they explained that the first time they heard about the Sponsorship Policy was during the course of this audit.

As the unit of government responsible for the register, DPC did not monitor compliance with the Sponsorship Policy; much less enforce its implementation. Moreover, DPC, did not record its own sponsorship information in the register.

The low compliance rate gives limited assurance that public expenditure on sponsorships is transparent, cost-effective and meeting set objectives.

2.5 Management of state purchase contracts

It is mandatory for departments to purchase certain goods and services through state purchase contracts (SPC). These contracts are established to streamline purchase requirements and provide value-for-money in procurement.

There is no requirement for agencies such as Tourism Victoria, the Transport Accident Commission, the Transport Ticketing Authority, VicRoads and WorkSafe to purchase from SPCs, but they can with the consent of the relevant contract manager.

DPC is responsible for managing the MAMS contract, and had responsibility for managing the Print Management Services and Marketing Services Panel contracts until 2009.

However, DPC has not been effective in managing the contracts for the three SPCs. It does not monitor whether contracts meet objectives, and does not confirm that negotiated rates are competitive and give the government best value. In addition, there is little evidence that it assesses service provider performance. It also does not consistently and reliably monitor department and agency spending under each SPC.

2.5.1 Master Agency Media Services

Document and record management

DPC does not systematically or appropriately file or secure records and documents for the MAMS contract. For example, the original 2006 contracts and their variations, as well as the Premier's signed authorisation for the use of MAMS trust funds proceeds for the Working Victoria advertising campaign were not able to be located.

Other files and records took considerable time to find because, in addition to not having been systematically filed, these were located in various areas of DPC. There were record folders that were not located at all.

DPC also advised that documents and records of correspondence were often saved in the private computer drives of previous staff members and these were not copied to the shared drive or filed in the appropriate record folders. None of this reflects acceptable practice in the management of public records.

Contract management framework

DPC has no framework of required policies, procedures and activities to effectively guide the management of most aspects of the MAMS contract. There were weaknesses in the areas of rates negotiation, eligibility, pricing, invoicing, collection of service fees, performance and compliance monitoring, contract reviews, and expenditure reporting.

The lack of such a framework, coupled with the absence of a dedicated contract manager during the period subject to the audit, resulted in the MAMS contract being managed in an ad hoc manner:

- MAMS usage across government was not reliably monitored and recorded.

- Issues were dealt with as they arose.

- The achievement of contract objectives was not assessed or reported.

DPC was therefore unable to demonstrate that the government obtained the best possible results from the MAMS contract or that it got value-for-money. Significantly, DPC had to revise publicly reported MAMS expenditure for 2009–10 from $124 million to $130 million because it failed to check expenditure data received from service providers.

Anticipated benefits

DPC is unable to guarantee that rates negotiated under the MAMS contract represent best value. There is little assurance that MAMS secured for the government rates that are more competitive than those that smaller organisations are able to negotiate.

This is because DPC does not check data provided by service providers on savings and cost benefits, specifically:

- the dollar value of actual savings and the value added, and how this compared with claimed negotiated rates

- whether the negotiated rates were in fact lower than the market average and were the most competitive available.

In addition, reviews on customer satisfaction with the MAMS contract indicated that in the value-for-money category, the 80 per cent satisfaction target was not met. Fewer than 65 per cent of government media buyers were satisfied that the MAMS contract offered below standard rates. While this low level of satisfaction was evident since at least 2006, no action to address this situation had been initiated.

Management of the Master Agency Media Services trust fund

Service fees and expenses in relation to the running of the MAMS contract are paid into and out of the MAMS trust fund. There is no detailed procedure for the day-to-day management of the MAMS trust fund. This increases the risk of:

- non-receipt of contracted service fees

- the inappropriate handling of the three trust fund bank accounts and the failure to maximise interest earnings

- non-compliance with reporting requirements

- inappropriate use of trust fund proceeds.

Moreover, DPC was not appropriately resourced with skilled and trained personnel to manage the finances of the trust fund. As a consequence, rebates and service fee transactions were not appropriately reconciled, verified and monitored.

Reconciliation of Master Agency Media Services fees remitted to the Department of Premier and Cabinet

On behalf of the government, the service provider includes a percentage-based service fee on each media invoice to government departments and agencies. This service fee is then forwarded to the MAMS trust fund.

The fees remitted by the service providers to the MAMS trust fund account were not reconciled against actual media placement expenditure during the four-year period 2006 to 2010. There was no evidence that the full contracted service fee was collected and forwarded to the MAMS trust fund. For example, reported MAMS expenditure for 2008–09 and 2009–10 was $244.8 million. DPC records indicate that the total remittance to the trust fund for the same period was approximately $500 000 less than the expected service fee.

However, in the absence of reconciliation of what was remitted to the trust fund as against media placement costs, it is not possible to determine whether the government received the contracted service fees in full.

2.5.2 Print Management Services

DPC's management of the Print Management Services (PMS) contract was poor. This was reflected in customer surveys and DTF analysis.

A customer satisfaction survey from May 2009 showed that government users generally felt the service from the PMS service provider was poor. Insufficient resources, delays in finished products, poor quality and errors were cited as major concerns. DPC made no attempt to address this situation. The management of the PMS contract was transferred to DTF in December 2009.

DTF identified the following issues when DPC was managing the PMS:

- no reporting or tracking against contract objectives, particularly the 15 per cent savings anticipated at contract commencement

- significant perception by customers of poor quality service and insufficient and inefficient use of service provider resources

- overall difficulty measuring service provider performance against agreed key performance indicators

- the agreed key performance indicators did not fully reflect contract objectives.

When it took over the PMS contract in December 2009, DTF systematically facilitated and coordinated the:

- monitoring of achievements against objectives

- tracking and monitoring of PMS use and spending

- assessment of service provider performance against agreed indicators

- tracking and monitoring of customer satisfaction.

The service provider sent monthly and quarterly reports to DTF on financial reporting, management reporting, customer satisfaction, cost savings and issues resolution. DTF also has monthly meetings with departmental and agency PMS representatives, as well as the PMS steering committee so that it can resolve issues between the parties.

As a result, 2010 customer feedback and evaluation show a minimum 86 per cent approval rating in all areas. In particular the account management, coordination and print quality criteria consistently received a satisfaction rating of 90 per cent or above in 2010 which is a marked improvement.

2.5.3 Marketing Services Panel

DPC's management of the Marketing Services Panel (MSP) contract was also poor, underpinned by ineffective recording, reporting, and monitoring of government expenditure for marketing services. DTF assumed management of the MSP in December 2009.

Transparent and reliable recording of panel usage

DPC did not appropriately monitor MSP usage and spending, so there were no accurate data for the period before DTF assumed responsibility. A DTF commissioned review revealed that from 2005 to 2008, the discrepancy between departmental and service provider data was at least $24 million.

The MSP was set up mainly to get transparent and reliable monitoring and reporting of government spending on marketing services. MSP documents indicate this was seen as a significant step towards greater accountability in government communications activities. The objective was not achieved.

Department of Treasury and Finance management of the Marketing Services Panel

As with the PMS, the management of the MSP improved significantly under DTF. With regular reporting from, and close coordination with the 78 service providers, DTF effectively tracks performance against agreed indicators and tracks panel usage and expenditure. Monthly and quarterly meetings with departmental and agency users also allow DTF to monitor customer satisfaction with services.

DTF has introduced on-line performance management, which gives the service provider timely feedback and allows the early resolution of issues, if any. It also contributes to the continuous improvement of services from the MSP.

Recommendations

-

The Department of Premier and Cabinet should:

- make total advertising and communications expenditure publicly available

- require an acquittal of campaign expenditure against approved budgets

- educate applicable parties on relevant guidelines, and monitor compliance

- improve its management of the Master Agency Media Services contract.

- Departments and agencies should:

- introduce rigorous business operations processes to enable consistent and accurate reporting of advertising and communications expenditure

- publish details and costs of advertising campaigns and sponsorships provided and received

- comply with all relevant advertising and communications policies and guidelines.

3 2009 Guidelines – compliance and better practice

At a glance

Background

Government advertising and communications material should be relevant to government responsibilities, appropriately planned, not intended to promote party political interests, based on accurate and verifiable facts, and not excessive or extravagant in relation to the objective.

Conclusion

Advertising and communications activities suffer from a lack of clear leadership and coordinated guidance by the Department of Premier and Cabinet.

While the 2009 Victorian Government Advertising and Communications Guidelines (2009 Guidelines) are comparable to similar guidelines in other jurisdictions, improvements can be made to increase their transparency and accountability. A compliance assessment of five advertising campaigns indicates general compliance with the 2009 Guidelines, however, there were notable breaches that departmental oversight processes failed to identify.

Findings

- There is not common awareness and understanding of the coverage and applicability of the 2009 Guidelines.

- There was insufficient documentation to allow independent verification of the assessment conducted by the then Government Communications Review Group on campaign applications.

- One advertising campaign reviewed during the audit included elements which may be construed as serving party-political interests. Another presented information that was neither accurate nor verifiable.

Recommendations

- The Department of Premier and Cabinet should revise the 2009 Guidelines in line with better practice, and develop a whole-of-government communications strategy.

- Departments and agencies should have rigorous oversight processes for finalising advertising campaign materials.

3.1 Introduction

The use of public funding for government advertising and communications requires appropriate levels of accountability. In 2009, the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) released new guidelines for public sector entities involved in advertising and communications.

The guidelines focus on avoiding party political advantage, the appropriate use and levels of government funds, accountability and maintaining standards. The guidelines also outline requirements for all advertising and communications, specifically that they are:

- relevant to government responsibilities and appropriately planned

- not intended to promote party political interests

- not excessive/extravagant in relation to the objective

- presented based on accurate and verifiable facts.

3.2 Conclusion

Advertising and communications activities suffer from a lack of clear leadership and coordinated guidance by DPC.

DPC does not facilitate or monitor the consistent interpretation and application of the 2009 Victorian Government Advertising and Communications Guidelines (2009 Guidelines). It also does not plan or implement a coordinated strategy for advertising and communications activities across government.

The absence of a strategic advertising and communications plan across government gives limited assurance that approved advertising campaigns are consistent with government priorities, or that opportunities to leverage messages and achieve cost savings are maximised.

While the 2009 Guidelines are comparable to similar guidelines in other jurisdictions, they can be improved to increase transparency and accountability.

A compliance assessment of five advertising campaigns indicates general compliance with the 2009 Guidelines. There were, however, notable breaches that departmental oversight processes failed to identify and address.

3.3 The 2009 Guidelines

To be effective, guidance should be easily understood, and applied consistently.

The 2009 Guidelines, however, are not effective—undermined by a poor understanding of their relevance, key concepts and applicability.

3.3.1 Application

There is not common awareness and understanding of what the 2009 Guidelines cover, and how entities should apply them. Significantly, as the guidelines do not define what ‘advertising’ or ‘communications’ are, entities lacked awareness of what these activities included. For example, eight of the 11 departments audited interpreted the guidelines to refer to all communications activities including advertising, media relations and sponsorships. Three departments interpreted the guidelines to apply only to paid advertising campaigns, although two of these were uncertain.

The 2009 Guidelines also do not specifically identify the types of government bodies subject to its provisions.

All departments understand that they were required to comply with the guidelines; however, the five statutory authorities do not consider that they are bound by them and believe that they have the ability to opt in or opt out of the guidelines.

This was supported by documentation which indicated that public entities like Tourism Victoria, the Transport Accident Commission, the Transport Ticketing Authority, VicRoads and WorkSafe were not required to comply with the guidelines but had the option to do so.

The agencies advised that prior to the audit they were unaware that the 2009 Guidelines are the government’s overarching policy on advertising and had little awareness of other guidelines such as the Evaluation Guidelines and Sponsorship Policy.

3.3.2 Department of Premier and Cabinet’s interpretation

Because the 2009 Guidelines do not define key terms, focusing more on principles, they are open to interpretation. DPC has interpreted the guidelines as applying only to external communications that have been scrutinised by whole-of-Victorian-government internal approval processes (previously the Government Communications Review Group and the Communications Committee of Cabinet). DPC’s view is that this has been the working definition in place for ‘government communications’ since September 2006.

This interpretation considers only a narrow range of actual government communications. It does not cover all advertising purchased through the Master Agency Media Services (MAMS) contract, such as vacancy recruitment and non-campaign advertising regardless of cost, or campaign advertising with a media placement cost of below $50 000. These were all exempt from the previous government approval processes.

DPC’s interpretation also limits the effect of the guidelines on activities other than advertising. The guidelines clearly point to communications other than advertising bought through the MAMS contract, such as reports, websites, official announcements and policy explanations.

DPC needs to implement agreed definitions for, and a common understanding of, the coverage and applicability of the 2009 Guidelines and all associated whole‑of‑government policies and guidelines.

3.4 Better practice

In the second half of 2011 DPC has moved towards better practice in undertaking its role in government advertising and communications. Specifically it has worked to improve:

- its management of the MAMS contract

- oversight of advertising and communications activities across government.

This is a positive initiative for which momentum should be maintained. This should also be extended to other aspects of DPC’s role – particularly with respect to transparency and accountability.

3.4.1 Advertising and communications guidelines

Victoria’s advertising and communications guidelines were first adopted in 2002 and revised in 2009, both in response to recommendations from this office, and because of changing community expectations. While an improvement on the 2002 iteration, the current guidelines no longer reflect better practice, especially with respect to transparency and accountability.

Guidelines and arrangements in other states and territories, and the Australian and Canadian Commonwealths, reflect developments since the 2009 Guidelines took effect. These include:

- clear and periodic disclosure of actual advertising and communications activities and expenditure

- clear, practical and unambiguous advertising and communications guidelines and requirements

- annual advertising and communications strategies for activities that match government priorities, facilitate the leveraging of messages, and are good value‑for-money

- publication of market research reports commissioned for government advertising and communications

- the detailed and timely certification by the agency chief executive officer of compliance with advertising and communications guidelines and requirements.

The 2009 Guidelines are comparable to the advertising and communications guidelines in other jurisdictions, including the fundamental principles relating to the prohibition of incurring party political advantage. Academics and policy analysts have commended the guidelines for their clear exposition of what constitutes party political advertising. Nonetheless, they could be clearer about:

- what types of communications and which government entities are covered

- how they apply to new and emerging communications, such as web, digital and mobile phone-based activities

- how to assess advertising and communications materials against guideline criteria, such as what constitutes excessive/extravagant in relation to objectives, and how to determine if information is based on accurate and verifiable facts

- how they apply to advertising and communications activities outside Australia or those co-funded with third parties, such as businesses or other governments.

3.4.2 Whole-of-government communications strategy

Tourism Victoria, the Transport Accident Commission and WorkSafe present their annual campaign advertising plans for government approval. These plans are typically underpinned by robust business cases that are endorsed by their respective boards or senior executives. These agencies get a one-off approval for all their advertising campaigns for a particular financial year.

These statutory authorities assert that planning in this manner:

- enables the effective scheduling of campaign strategies throughout the year

- streamlines the messages delivered to the public

- saves significant resources by not having to approach government each time advertising campaign applications require approval

- delivers cost efficiencies in terms of procuring specialist services and media placement, for example, it is more cost effective to purchase media slots when the order is placed sufficiently ahead of time.

While this is an example of better practice, it has not been adopted more broadly across the public sector.

Rather, DPC received between 250 and 450 advertising campaign applications each financial year in the four years to 2010. There was no requirement or system in place to take a planned and integrated approach within departments and authorities, and across the sector. Generally, DPC considered applications as they were received.

The former Government Communications Review Group (GCRG) advised government in late 2009 that the numerous applications submitted ‘highlighted a lack of integration of communications activity across departments and agencies’, and that ‘opportunities for cost savings cannot be realised; the risk of contradictory communications is increased and opportunities to leverage messages are lost’. To promote greater efficiency and effectiveness, GCRG proposed a whole-of-government plan for advertising and communications activities for 2010 through:

- highlighting opportunities for cost savings

- leveraging communications activities across and within portfolios.

While a whole-of-government communications plan was a step in the right direction, the objective to deliver greater efficiency and effectiveness in government communications was not achieved. Campaigns within and across portfolios were not integrated.

This was a missed opportunity. A well-considered whole-of-government communications plan or strategy would enable an improved focus on effectiveness and cost efficiency, and better integrated and more focused campaigns. It could also provide a framework for the selection of priorities for which there is a clear role for government communications and advertising.

Whole-of-government coordination

Coordination of advertising and communications activities at a whole-of-government level can play an important role in facilitating strategic planning for communications campaigns, developing, implementing and monitoring compliance with policies and guidelines, and effectively managing relevant state purchase contracts.

DPC needs to significantly improve its performance in enhancing the transparency and accountability of advertising and communications across government. Specifically, it should:

- provide clear and periodic disclosure of actual advertising and communications activities and expenditure

- coordinate and implement an annual advertising and communications strategy for advertising and communications activities across government

- effectively and appropriately manage the Master Agency Media Services contract

- clarify and educate the coverage and applicability of guidelines and policies

- develop and implement a framework to monitor compliance with the 2009 Guidelines and other relevant advertising and communications guidelines

- make available to the public the results and reports of market researches commissioned by government and departments.

3.4.3 Demonstrating the need for advertising campaigns

The 2009 Guidelines require ‘a clear line of accountability’ for advertising and communication processes. However, there is insufficient documentation to enable independent verification of the assessment conducted by GCRG on campaign applications.

GCRG decided which advertising campaign applications were submitted to the Communications Committee of Cabinet for approval. Its terms of reference required it to also provide advice to government on:

- the relevance, achievability and measurability of the objectives being pursued

- how well the campaign supports government priorities, themes and messages

- the level of priority that should be attached to the campaign

- how effectively the campaign strategy addresses the objectives

- how effectively the evaluation of the campaign outcomes had been planned

- whether there had been similar or related activities conducted previously, and if so what were the outcomes

- whether the campaign complies with all applicable government guidelines.

In most instances the documentation provided by GCRG consisted only of the application form completed by the department/agency applicant, which contained minimal information about the campaign.

Given its responsibility to determine which applications were suitable for government’s consideration, GCRG should have attached its assessment of each application based on the above criteria. Without such documentation and logically linked advice, the ability of the government to determine and approve advertising applications was significantly compromised.

3.5 Campaign compliance assessment

We assessed five representative advertising campaigns in 2010 for compliance with the 2009 Guidelines:

- Department of Primary Industries’ Locusts Preparedness and Response

- WorkSafe Victoria’s Musculo-skeletal Disorders

- VicRoads’ CityGT

- Department of Transport’s Transport Plan

- Regional Development Victoria’s Blueprint for Regional Victoria.

They were chosen on the basis of materiality, visibility, type of advertisement, type of entity (department or agency) and whether the entity ran a centralised or decentralised communications function.

3.5.1 Relevant to government responsibilities

The 2009 Guidelines require the subject matter to be directly related to government responsibilities and to help:

- maximise compliance with the law

- achieve awareness of a new or amended law

- inform the public of new, existing or proposed government policies or policy revisions

- ensure public safety, personal security or encourage responsible behaviour

- assist in the preservation of order in the event of a crisis or emergency

- promote awareness of rights, responsibilities, duties or entitlements

- encourage use of or familiarity with government products or services

- report on performance in relation to government undertakings

- inform the public that the state is a good place to live, study, work or invest

- encourage social cohesion, civic pride, community spirit, tolerance, or assist in the achievement of a widely supported public policy outcome.

All campaigns examined related to government responsibilities.

The Blueprint for Regional Victoria and Transport Plan campaigns were intended to inform the public about the government’s new plan for the regions and the transport sector respectively.

The Locusts Preparedness and Response, CityGT and Musculo-skeletal Disorders campaigns were intended to promote public safety and encourage responsible behaviour. The Locusts campaign had the additional purpose of informing the public of the potential threat and impact of plague locusts, and the new government policy requiring landholders to report and treat locust infestation on their land.

3.5.2 Not directed at promoting party political interests

As advertising and communications materials may potentially give an incumbent government political advantage, the 2009 Guidelines state that ‘public funds should NOT be used for government communications where:

- government programs or initiatives intentionally promote a political party, a candidate for election or a member of Parliament above the public interest

- official pronouncements and explanations of government policy refer to the name of a political party or to the government using the Premier’s name

- members of the government are named, depicted, or otherwise promoted in a manner that a reasonable person would regard as excessive or gratuitous

- government websites and advertising are produced that link directly to the websites of political parties’.

Of the five campaigns assessed, only the Transport Plan campaign contained a clear breach of the 2009 Guidelines by referring to the government as the ‘Brumby government’ in one of its publications.

Moreover, a Transport Plan publication featuring a photograph of the then Minister for Transport was mailed to residents in a particular suburb. It is considered a reasonable person would regard this as gratuitous and indicative of the intent to serve party political interests. The Department of Transport has accepted that these two examples breach the 2009 Guidelines.

The 2009 Guidelines further detail what could constitute the promotion of a political party, namely the:

- content

- campaign source

- campaign reason

- campaign purpose

- choice of media

- timing, geographic and demographic targeting of the campaign