Personal Expense Reimbursement, Travel Expenses and Corporate Credit Cards

Overview

The audit examined the management of travel-related, hospitality, credit card and reimbursed expenses for the following six agencies: the departments of Business and Innovation, Human Services, Justice (DOJ) and Premier and Cabinet, the Country Fire Authority and Tourism Victoria. The audit also included the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) because of its whole-of-government oversight role.

We found that these agencies are effectively controlling expenses so that they are used for legitimate business purposes:

- Cases where public money is used for purely personal benefit are extremely rare and only a small proportion of transactions—7 per cent of the sample of 460 we tested—did not fully comply with legislated rules.

- However, there is no cause for complacency because the mechanisms for assuring government about performance are not working—except for DOJ, agencies did not accurately report rule breaches to the Minster for Finance, and DTF did not adequately review this information.

Overall, agencies have not done enough to improve cost-effectiveness by understanding and reducing the costs of small transactions and addressing spending that leaks outside of mandatory, heavily discounted State Purchase Contracts (SPCs). To help achieve the government's goal of reducing departments' non-payroll costs by $722 million over four years, agencies should identify further efficiencies by:

- understanding where they do not use mandatory SPCs, reporting this information to DTF and securing further savings by addressing contract leakage

- analysing how they purchase and pay for goods and services and identifying improvements based on the costs, benefits and risks.

Personal Expense Reimbursement, Travel Expenses and Corporate Credit Cards: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER May 2012

PP No 129, Session 2010–12

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Personal Expense Reimbursement, Travel Expenses and Corporate Credit Cards.

Yours faithfully

![]()

D D R PEARSON

Auditor-General

2 May 2012

Audit summary

Background

Public sector agencies meet the business costs they incur by reimbursing out‑of‑pocket expenses, settling corporate purchasing card statements and paying invoices generated through their activities. These costs are significant, for example, during 2010–11, agencies charged $61.6 million to government purchasing cards and spent a total of $14.4 million through the whole-of-government contract for air travel.

The government's 2010 Better Financial Management Plan, which requires departments to reduce non-payroll costs by $722 million over four years, has added impetus to finding savings while properly controlling expenses and improving services to the community.

In Victoria, legislation describes a framework of rules for effective and efficient financial management. Public sector agencies are responsible for developing specific systems, procedures and reports to meet these rules and assure government that they have achieved this.

The Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) communicates the legislated rules to public sector agencies and monitors their compliance on behalf of the Minister for Finance. DTF has translated the rules into the Financial Management Compliance Framework (FMCF), which agencies are required to follow.

Agencies report annually on their compliance with the FMCF through a checklist and DTF uses this information to assure the Minister for Finance and Parliament that the state's finances are well managed.

The audit examined the management of travel-related, hospitality, credit card, and reimbursed expenses for the following six agencies: the departments of Business and Innovation, Human Services (DHS), Justice (DOJ) and Premier and Cabinet, the Country Fire Authority and Tourism Victoria (TV).

The audit also included DTF because of its whole-of-government oversight role. It assessed how well agencies had applied, and DTF had overseen, the FMCF for:

- controlling expenditure so that funds are used for legitimate business expenses in accordance with the rules

- taking account of the costs, benefits and risks when deciding how to purchase and pay for goods and services

- realising the potential savings of using mandated State Purchase Contracts (SPCs)—whole-of-government, discounted contracts for goods and services.

Conclusions

The agencies examined in this audit are effectively controlling expenses so that they are used for legitimate business purposes. Cases where public money is used:

- for purely personal benefit are extremely rare

- for legitimate business purposes, but without complying with all the rules, make up a small proportion of purchases—less than 10 per cent of the total number.

However, there is no cause for complacency because:

- agencies have not done enough to improve cost-effectiveness by understanding and reducing the costs of small transactions and addressing spending that leaks outside of mandatory, heavily discounted, SPCs

- the mechanisms for assuring government about performance are not working—except for DOJ, agencies did not accurately report rule breaches to the Minister for Finance, and DTF did not adequately review this information.

The government's goal of reducing departments' non-payroll costs by $722 million over four years means public sector agencies should realise savings that can be made by using more cost-effective purchasing arrangements, including SPCs.

Realising greater efficiency

Departments should identify further efficiencies by:

- understanding where they do not use mandatory SPCs, reporting this information to DTF and securing further savings by addressing contract leakage

- analysing how they purchase and pay for goods and services and identifying improvements based on the costs, benefits and risks.

The public sector is expected to spend more than $750 million each year on SPCs. Only one agency in this audit, DOJ, had purposefully managed contract leakage. Its experience showed the significance and benefits of doing this, reducing average leakage from 47 per cent to 14 per cent of spending on the goods and services available through these arrangements. This generated significant savings.

The agencies in this audit understood the costs of processing invoices and five of them had upgraded their systems to secure efficiency gains. They did not have the same knowledge of expenses involving purchasing cards or reimbursements. Documenting the costs, benefits and risks will help them verify or improve their efficiency.

Managing expenditure risk

Agencies have consistently applied core controls requiring evidence of an expense and the documented approval by a person other than the purchaser. This reduces the risk that non-business expenses will go unchallenged.

However, a small proportion of transactions—7 per cent of the sample of 460 we tested—did not fully comply with legislated rules. These breaches happen when:

- the rules are not adequately documented and communicated to staff

- staff work around the rules to make a legitimate business purchase.

The reporting mechanisms intended to alert DTF and the Minister for Finance to transactions that broke the rules failed. Only DOJ accurately reported purchasing card rule breaches and DTF did not detect the reporting failures of the other agencies.

Addressing these issues requires the continued and improved scrutiny of transactions, comprehensive documentation of the rules and their clear communication to staff. DTF needs to improve how it communicates updated purchasing rules because the existing mechanisms have not been effective. Only DHS and TV incorporate the latest purchasing card rules in cardholder agreements.

Public sector agencies should meet government's reporting requirements and DTF should apply a greater level of scrutiny in assessing the validity of these reports.

Recommendations

Public sector agencies should:

-

review and increase the level of scrutiny and control applied to transactions by:

- making greater use of in-built card limits

- running regular, automated tests to detect control breaches and better target

- detailed reviews including reviews of personal expenses in their forward internal audit programs

- review and, where required, strengthen how they document and communicate rules so that staff have a comprehensive understanding of their obligations

- meet the mandatory requirements for reporting unauthorised purchasing card use and thefts and losses.

- improve its communication of changes to the legislated purchasing rules so that agencies have a comprehensive and current understanding of what is required

- significantly improve its scrutiny of agencies’ reporting on breaches of the purchasing card rules and reports on thefts and losses.

-

The Department of Premier and Cabinet should evaluate the

effectiveness of the 2012 hospitality guidelines within two years of their

issue, by:

- confirming that agencies have adequately reflected the revised framework in their individual policies

- assessing the impact on hospitality expenditure and controls, and the community’s satisfaction with the way agencies control this type of expenditure.

The Department of Treasury and Finance should:

Public sector agencies should:

- comprehensively analyse how they purchase and pay for goods and services, and identify improvements based on the costs, benefits and risks

- report and address expenditure occurring outside of mandated State Purchase Contracts.

- The Department of Treasury and Finance should request an acquittal of the scale of contract leakage and the reasons why this happens from agencies participating in a mandatory State Purchase Contract.

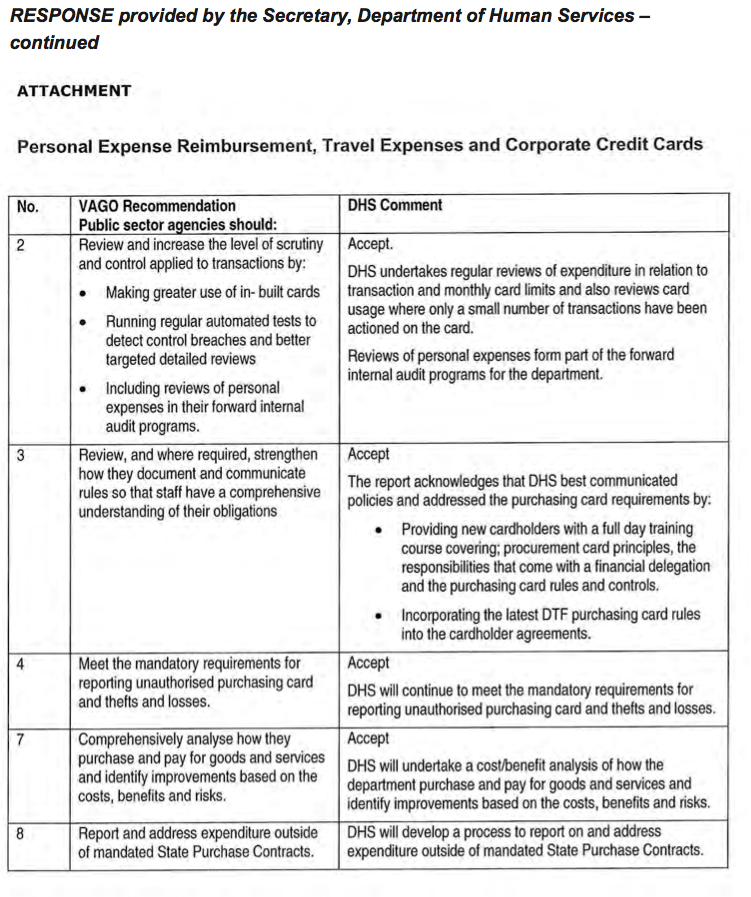

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the departments of Business and Innovation, Human Services, Justice, Premier and Cabinet, and Treasury and Finance, the Country Fire Authority and Tourism Victoria, with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments however, are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Public sector agencies meet the reasonable business costs they incur by reimbursing out-of-pocket expenses, settling corporate purchasing card statements and paying invoices generated through their activities. These costs are significant, for example, during 2010–11 agencies charged $61.6 million to government purchasing cards and spent a total of $14.4 million through the whole-of-government contract for air travel.

Public sector agencies are responsible for controlling expenditure consistent with legislation that defines sound financial management.

The following sections describe this legislation, government policy and the roles and responsibilities of the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) and the public sector agencies it oversees on behalf of the Minister for Finance.

1.2 Legislation and policy

In Victoria, legislation describes the requirements for the financial management of public sector agencies. The legislation creates a framework of principles and rules, but allows agencies to develop specific systems, procedures and practices to fulfil these principles and comply with the rules.

1.2.1 Legislation

The legislative framework includes:

- the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA)

- Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance under the FMA (the standing directions)

- the Financial Management Compliance Framework (FMCF).

Financial Management Act 1994

The FMA is the principal legislation governing public sector financial management and annual reporting. Its objectives are to:

- improve the financial administration of the public sector

- make better provision for the accountability of the public sector

- provide for annual reporting to Parliament by public sector agencies.

Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance

In 2003, the Minister for Finance issued standing directions under section 8 of the FMA.

The standing directions document what public sector agencies need to do to:

- implement and maintain appropriate financial management practices

- achieve a consistent standard of accountability and financial reporting.

Each standing direction includes:

- background material

- a concise description of the direction

- a procedure for complying with the direction

- guidelines to help agencies interpret the direction and apply the procedures.

The parts of the document describing the standing directions and procedures have legislative force, while the remaining parts provide best practice guidance.

Figure 1A describes the standing directions that are of most relevance to the expenses examined in this audit.

Figure 1A

Standing directions relevant to this audit

Standing direction |

Relevant requirements for public sector agencies |

|---|---|

3.1.3 Policies and procedures |

Document, communicate and regularly review policies and procedures used to control transactions. |

3.4.6 Expenditure |

Implement and maintain effective controls for travel and hospitality expenditure, personal expense reimbursements and the use of purchasing cards. |

3.2.1 IT management |

Annually review the use of information technology for financial management. |

3.2.4 IT development |

Annually review the efficiency and effectiveness of core financial processes. Document a business case for proposed system developments. |

3.4.5 Procurement |

Establish effective controls over procurement so that agencies comply with government supply policies, including the use of whole-of-government State Purchase Contracts. |

4.5.1 Compliance with standing directions |

Annually review and certify that they have complied with all applicable standing directions. |

4.5.3 Purchasing card |

Establish effective controls so that purchasing cards are used according to the government's rules and report all cases of unauthorised use. |

4.5.4 Thefts and losses |

Report all cases of suspected or actual monetary and property thefts and losses and address control weaknesses highlighted by these cases. |

Source: Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance under the Financial Management Act 1994.

Financial Management Compliance Framework

The Minister for Finance endorsed the FMCF to help public sector agencies apply the standing directions.

The FMCF translates the standing directions into specific requirements describing what public sector agencies need to do to meet the government's objectives of:

- promoting effective financial management

- making agencies accountable

- providing ministers with reasonable assurance that agencies have complied with the standing directions and are using public resources efficiently and responsibly

- documenting and reporting on compliance with the standing directions.

The Minister for Finance supplemented the standing directions by endorsing more detailed rules on the use and administration of purchasing cards, and the monitoring and reporting of thefts and losses. These have been incorporated into the FMCF.

Public sector agencies are required to submit an annual checklist to DTF certifying that they have followed the FMCF. These reports are used to assure the Minister for Finance that public sector agencies are effectively and efficiently managing public resources.

1.2.2 Policy

The government is implementing its 2010 Better Financial Management Plan to deliver savings of $1.6 billion over five years from 2010–11 to 2014–15.

It aims to achieve 45 per cent of these savings by reducing departmental running costs by $722 million. This will require a 1 per cent procurement efficiency saving on non‑payroll costs compared with agencies' budget and forward estimates as they stood in late 2010.

The parts of this report that examine agencies' efficiency in purchasing goods and services and their use of State Purchase Contracts directly relate to this policy objective.

1.3 Roles and responsibilities

1.3.1 The Department of Treasury and Finance

Vision, mission and role

DTF's vision is for a prosperous future for all Victorians. DTF's mission is to provide leadership in economic, financial and resource management so that the state benefits from the highest standard of economic, financial and resource management.

DTF advises government on how to manage resources to deliver its policy outcomes through guidance in the form of a framework for responsible financial management. DTF is responsible for designing, communicating and monitoring the FMCF, and advising the Minister for Finance on the levels of compliance achieved by public sector agencies.

Administering the framework and advising government

DTF administers the FMCF and is responsible for:

- implementing strategies that improve compliance across the public sector

- monitoring public sector agencies' compliance

- advising the Minister for Finance about levels of compliance and the actions needed to address weaknesses in the FMCF or its application.

The Minister for Finance provides assurance to Parliament that expenditures across the public sector are effectively controlled based on DTF's advice summarising:

- departments' summary reports on how well they, and the other public sector agencies in their portfolios, had complied with the government's framework

- the results of DTF assurance reviews

- DTF's actions to improve compliance through training and improved communication and monitoring.

The Department of Treasury and Finance's 2011–14 strategic plan and 2011–12 business plan

DTF's current planning documents describe DTF's financial management leadership role and specific actions for improving financial management and achieving the savings set out in the government's Better Financial Management Plan.

The strategic plan includes the goal of building Victoria's and DTF's reputation as leaders in financial and performance management by:

- strengthening the frameworks underpinning financial and resource management

- increasing accountability and transparency in delivering services and programs

- instilling awareness across the public sector of the levels of accountability required for exemplary public sector financial management.

DTF will know it has succeeded in achieving the goals described above if by 2014:

- Victoria is considered to have a best practice public sector financial management and accountability framework that delivers improved effectiveness and efficiency

- government decisions are supported by high standards of accountability and the timely disclosure of relevant, reliable and understandable information to Parliament and the community

- DTF is an exemplar of best practice financial management and a skilled and effective change agent.

DTF's shorter-term objectives described in the business plan are to improve value‑for‑money from government services and realise the efficiency savings set out in the government's Better Financial Management Plan.

1.3.2 Agencies

Public sector agencies are responsible for effectively managing their finances by complying with the standing directions. Each agency needs to develop and document policies, procedures and systems so they comply with the standing directions and manage their resources effectively and efficiently.

Public sector agencies are required to:

- conduct an annual review of compliance with the FMCF obligations

- complete an annual certification process describing how well they have met the requirements of the FMCF and addressing areas where they fell short of meeting the framework's requirements.

1.4 Audit objective and scope

The audit examined how well agencies had applied, and DTF had administered and overseen, the legislated principles and rules for effectively and efficiently managing expenses by:

- controlling expenditure so that funds are used for legitimate business expenses in accordance with the FMCF's rules

- taking account of the costs, benefits and risks of options when deciding how to purchase and pay for goods and services

- realising the potential savings from using State Purchase Contracts, the whole‑of‑government, discounted arrangements, where these are mandatory for departments.

The audit examined the travel-related, hospitality, purchasing card and reimbursed expenses of the following six agencies: the departments of Business and Innovation, Human Services, Justice, and Premier and Cabinet, and the Country Fire Authority and Tourism Victoria. The audit included DTF because of its whole-of-government oversight and leadership role in this area.

The audit was conducted in accordance with Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards.

The cost of the audit was $455 000.

1.5 Structure of the report

Part 2 examines how well the agencies in this audit have controlled expenses and managed the associated risks.

Part 3 describes whether agencies can demonstrate that they take account of the costs, benefits and risks when deciding how to purchase and pay for goods and services.

Part 4 examines whether agencies are realising the value provided by State Purchase Contracts which aggregate demand for specified goods and services with the aim of securing discounts and more effective delivery.

2 Managing expenditure risk

At a glance

Background

We examined how well agencies had applied, and the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) had overseen, the legislated rules designed to make sure that only legitimate expenses are funded and to deliver effective and efficient financial management.

Conclusion

Agencies' management and DTF's oversight of the expenses included in this audit have been generally effective.

Findings

Agencies have been effective in controlling expenses so that resources are used for legitimate business purposes. However, a small proportion of transactions did not comply with the purchasing rules. This requires better documentation, better communication and the use of automated, cost-effective checks.

The reporting mechanisms intended to alert DTF and the Minister for Finance to transactions that broke the rules failed. Of the six agencies examined, only the Department of Justice accurately reported purchasing card exceptions. DTF did not detect the reporting failures of the other agencies.

Recommendations

Public sector agencies should:

- increase the level of scrutiny and control applied to transactions

- strengthen how they document and communicate rules to staff

- meet the mandatory reporting requirements.

The Department of Treasury and Finance should:

- improve its communication of changes to the legislated purchasing rules

- significantly improve the scrutiny of agencies' reporting.

The Department of Premier and Cabinet should evaluate the effectiveness of the 2012 hospitality guidelines within two years of their issue.

2.1 Introduction

Agencies are required to comply with the Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance under the Financial Management Act 1994 (the standing directions). The standing directions create a framework for controlling expenditure, so that resources are effectively and efficiently used for legitimate business purposes.

The standing directions refer to any action outside of these rules as the ‘inappropriate use’, ‘unauthorised use’ or ‘misuse’ of resources.

In this Part we examine whether agencies:

- developed, documented and effectively communicated the policies and procedures required by the standing directions

- applied controls and checks to detect and prevent unauthorised use

- succeeded in preventing the unauthorised use of resources based on the internal audit evidence and VAGO’s testing of a sample of transactions

- accurately reported on where and how often the rules had been broken, allowing for the proper oversight of expenditure by the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) and the Minister for Finance.

2.2 Conclusion

All agencies applied controls requiring evidence of purchase and the documented approval of the expense by a person other than the purchaser. These core controls reduce the likelihood that non-business expenses will go unchallenged.

Agencies have been effective in controlling expenses so that resources are used for legitimate business purposes. In a small percentage of transactions, employees purchased goods and services for legitimate business purposes, but broke one or more of the purchasing rules. For example, VAGO’s testing found that 7 per cent of the 460 transactions reviewed did not fully comply with the purchasing rules.

This type of non-compliance weakens the control framework and, if not addressed, raises the risk of paying for illegitimate expenses.

The reporting mechanisms intended to alert DTF and the Minister for Finance about these exceptions failed—of the six agencies under review, only the Department of Justice (DOJ) accurately reported the number of cases where they knew purchasing card rules had been broken. DTF’s review of this information did not detect these reporting failures.

Four of the six agencies we examined applied more scrutiny to purchasing card transactions but less scrutiny to other types of expenses, such as personal reimbursements. This is the case even where reimbursements accounted for the same or more expenditure than purchasing cards. As a result these agencies do not have as clear an understanding of how well these expenses complied with purchasing rules.

2.3 Developing, documenting and communicating policies and controls

An effective control framework requires accessible, comprehensive and clearly communicated documentation about the rules and how they should be applied.

The standing directions require agencies to:

- establish and maintain documented policies and procedures in relation to travel and hospitality expenditures, personal expense reimbursements and the rules for the use and administration of purchasing cards

- effectively and efficiently communicate policies and procedures to all officers, either electronically or manually

- establish mechanisms to review policies and procedures.

The standing directions are most prescriptive for purchasing cards, mandating a detailed control regime, so that:

- adequate training is given to employees before they are issued with a card

- cardholders must sign a cardholder agreement before receiving a card

- expenditure does not exceed set monthly and transaction limits, as well as the cardholder's financial delegation

- sufficient documentation is maintained that adequately supports the payment process for all transactions

- monthly statements and supporting documentation are reviewed and approved by the appropriate approver.

The standing directions do not prescribe a control regime for travel, hospitality and reimbursed expenses. These expenses are, however, covered by government issued travel principles and hospitality guidelines that establish high-level, minimum requirements.

2.3.1 Developing, documenting and regularly reviewing policies and controls

Our observation of how agencies apply controls showed that all agencies include checks that encompass the purchasing card rules. The Department of Business and Innovation (DBI) was the exception because it did not enforce transaction limits or financial delegations.

Agencies audited had developed and documented policies covering the use and administration of purchasing cards, travel, hospitality and personal expense reimbursements. However, DOJ’s hospitality policy covers only the acceptance of, hospitality, not expenditure on it.

The depth and coverage of the policy documents and agencies’ effectiveness in communicating the rules varies and should be improved.

Purchasing card policies and controls

For purchasing cards, we assessed how well agencies had:

- established the necessary control regime

- documented the rules that regulate purchasing card use and administration

- identified and defined measures to control purchasing card use.

Application of controls

Agencies’ finance departments showed us how they applied the purchasing card controls as set out in the standing directions. This confirmed that all agencies, except DBI, check that the required controls are applied to purchasing card transactions.

DBI advised us that, in some instances, holders of purchasing cards had limits in excess of their financial delegations due to their roles in department-wide procurement activities. This is in breach of the purchasing card rules. It allows cardholders to create financial obligations for the agency greater than their legislative authority and DBI accepted that this practice should be corrected.

Documentation of controls

Audited agencies had met the standing direction’s minimum policy requirements for purchasing cards by providing cardholders with a copy of DTF’s purchasing card rules. However, the quality and depth of the documentation provided to help staff understand and apply these rules varied. DOJ and the Department of Human Services (DHS) had the most comprehensive documentation. They identified and documented the controls required and provided cardholders and authorising delegates with detailed flowcharts, screen shots and checklists to show how these rules should be applied.

DBI, the Country Fire Authority (CFA), the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) and Tourism Victoria (TV) did not provide the same level of detail about how staff should apply the rules. They should improve their documentation and provide a clear guide showing purchasing card users and approvers how to apply the required controls.

Review of policies and controls

DTF guidance recommends that policies and controls are reviewed every two years to incorporate changes in business requirements, technologies and emerging better practices.

We found mixed results when we assessed agencies’ performance in regularly reviewing policies and controls. TV, DOJ, DHS and DBI had policies that had been endorsed or reviewed within the past two years. However:

- CFA’s entertainment expenses policy was updated in September 2011 after remaining unchanged for 17 years

- DPC’s hospitality policy states it will be reviewed in January 2010, but this was delayed and DPC is currently reviewing the policy. In the meantime DPC has developed and issued interim, updated procedures to clarify hospitality policy requirements.

DTF has regularly updated the government's Purchasing Card Rules for Use and Administration since 2003. When this audit commenced in September 2011, only DHS and TV were using the latest version. This is concerning as the rules themselves mandate that any revisions to the rules or agency policies must be circulated to cardholders by the agency’s program administrator in a timely manner.

DTF should notify department contacts of all changes to the rules, even if these are considered minor, and agency contacts should communicate these to cardholders.

Personal expense reimbursement, travel and hospitality policies

We found that there is adequate whole-of-government guidance on personal expense reimbursement and travel. In contrast, agencies have not been able to draw on a whole-of-government guidance when deciding how to control hospitality expenditure. The government has recently approved, for subsequent distribution, an expanded policy framework covering hospitality expenditure and DPC needs to monitor its implementation and evaluate its effectiveness.

However, this framework is yet to be disseminated. Up to this point, the absence of a whole-of-government framework has led to inconsistencies in how audited agencies control hospitality expenditure. For example, the thresholds that triggered more onerous controls varied across agencies as did the controls on the supply of alcohol for agency events. For the supply of alcohol:

- DPC had the most stringent approach requiring the prior, written approval of the secretary and the assessment, monitoring and mitigation of the specific health and safety risks related to the supply of alcohol at events involving departmental staff

- TV’s policy requires the prior approval of the chief executive on a case-by-case basis when alcohol is supplied at an event

- DHS requires approval for all alcohol purchases, either by the secretary or a responsible executive or regional director. In addition, hospitality expenses over $2 000 require approval by an executive or regional director

- for CFA staff events, hospitality expenditure under $2 000, including the supply of alcohol, is authorised by the appropriate manager, whereas expenditure over $2000 requires the approval of a director or regional manager

- DBI’s hospitality policy does not include specific approval provisions for staff events involving alcohol and DOJ’s hospitality policy covers only the acceptance of hospitality, not expenditure on it.

Hospitality expenditure is an area of reputational risk for public sector agencies and the government. The media and the community are sensitive to what is perceived as excessive expenditure on food, alcohol and entertainment for public sector employees and those they are required to entertain.

In July 2011 the government asked the State Service Authority (SSA) to expand the 2010 Gifts, benefits and hospitality policy framework, guiding the receipt of gifts, benefits and hospitality, to cover hospitality expenditure. The government approved SSA’s proposed changes on 4 April 2012, asking it to prepare and publish the revised document under the cover of a Premier’s Circular to public sector agencies.

The acting Premier requested that the SSA:

- provide guidance on the key issues relating to the provision of hospitality

- advise departments about how to manage hospitality for staff-related functions, including advice on monetary thresholds and the appropriate service of alcohol

- describe appropriate mechanisms for the disclosure of hospitality expenditure

- indicate whether the expanded framework should be applied to all public sector hospitality without exemptions.

The expanded policy framework did not adopt a prescriptive approach to controlling expenditure on gifts and hospitality. It does not set monetary thresholds or specific rules for controlling hospitality expenditure. Instead it requires all public officials, as a minimum, to ‘ensure that:

- any gift or hospitality is provided for a business purpose in that it furthers the conduct of official business or other legitimate organisational goals, or promotes and supports government policy objectives and priorities

- any costs are proportionate to the benefits obtained for the State, and would be considered reasonable in terms of community expectations

- when hospitality is provided, individuals demonstrate professionalism in their conduct, and uphold their obligation to extend a duty of care to other participants’.

While the policy includes guidelines for containing the cost of hospitality and controlling the provision of alcohol, these are not mandatory and agencies need to develop their own policies to apply the high-level, minimum requirements.

Adopting a principle-based approach means that agencies are unlikely to apply uniform monetary thresholds or detailed controls to hospitality expenses.

The DPC should evaluate the effectiveness of these expanded guidelines within two years of their issue.

2.3.2 Communication of policies

The minimum communication requirement for reimbursed, travel and hospitality expenses is to provide access to these documents at all times and to inform staff of updates as they are authorised. Additional requirements apply to purchasing cards, because the rules mandate that agencies:

- provide appropriate training to cardholders before giving them a card

- require cardholders to sign an agreement which describes the terms and conditions for use.

Training for new cardholders

DHS best communicated policies and addressed the purchasing card requirements by:

- providing new cardholders with a full-day training course covering procurement principles, the responsibilities that come with a financial delegation and the purchasing card rules and controls

- incorporating the latest DTF purchasing card rules into cardholder agreements—DTF provides agencies with a model cardholder agreement incorporating the rules in the form of a template.

The five other agencies examined in this audit relied on less formal training, for example, one-on-one briefing sessions. Of these five agencies, only TV fully incorporated DTF’s latest template in their cardholder agreements.

For agencies with smaller numbers of purchasing cards, such as DPC, DBI and TV, the current one-on-one briefings should be adequate provided they have a clear structure backed by comprehensive content. For agencies, such as DOJ and CFA, with large numbers of cardholders, developing a formal training course similar to that provided by DHS would be beneficial.

Cardholder agreements that are up-to-date and comprehensive

Only DHS and TV used the most up-to-date DTF template. DBI was using an out‑dated template but has since updated its agreement with the latest DTF template. The remaining agencies, except for CFA, base their cardholder agreements on older, out‑dated versions. CFA did not use the template at all, but instead referred to the rules rather than reproducing them in the cardholder agreement.

However, the current DTF template is not comprehensive. For example, the template does not prohibit paying tips and gratuities or splitting transactions to stay within purchasing card transaction limits.

As a result, none of the agencies used cardholder agreements that comprehensively captured the government’s current purchasing card rules. DTF and the agencies in this audit should modify and update cardholder agreements to reflect the current rules.

DTF has advised that it will provide agencies with a template that is comprehensive. Agencies should use this as the minimum set of rules which all cardholders are required to sign.

2.4 Detecting and preventing inappropriate use

Agencies have applied controls to the expenses included in this audit requiring that:

- the purchaser provides evidence that the expense is legitimate

- a more senior person reviews and approves the expense taking account of government and agency policies, and the evidence of purchase.

These controls are the routine mechanism agencies use to prevent staff breaking the rules and to detect where this happens.

The government’s purchasing card rules require additional checks including:

- card administrators regularly checking a sample of transactions

- the annual review of card use by agencies’ internal auditors.

The standing directions do not mandate the same level of additional checks be applied to personal expense reimbursements.

2.4.1 Additional checks by agency staff

The level of scrutiny applied to personal expense reimbursements, beyond the core controls of approval, is lower than the level of scrutiny applied to purchasing card transactions.

Purchasing card transactions

Purchasing card program administrators for all the examined agencies monitor compliance and carry out checks on purchasing card transactions.

The card coordinators of TV, DBI and DPC check each monthly purchasing card statement for the probity of expenses and adherence to procedures. For CFA, DHS and DOJ, where the purchasing card programs are much larger, card coordinators check a sample of transactions:

- CFA check six or seven of 400 monthly purchase card statements against a checklist.

- DHS check a small sample (less than 50) of its 3 000 monthly transactions, it requires regular reports on card use by supervising managers,and conducts monthly reviews of overall card use.

- DOJ checks 20 randomly selected transactions from the 1500 transactions completed each month, and in addition, the CFO checks the monthly statements of the Secretary, the Fire Services Commissioner and those Executive Directors who are cardholders.

Personal expense reimbursements

Only TV applies additional checks to personal expense reimbursements. The finance section checks all claim forms, regardless of dollar amount, for the completeness of the form, supporting documentation and correct coding of the expense for tax purposes.

For the other agencies, the level of scrutiny applied to personal reimbursements was restricted to the core controls described above.

2.4.2 Meeting the internal audit requirements

The standing directions require agencies to implement an internal audit function to address relevant areas of their risk profile, as well as to include a review of purchasing card use in their internal audit programs on an annual basis.

Only TV, DBI and DHS examine personal expense reimbursements through their internal audit program. However, reimbursements can represent a significant amount of expenditure for the other audited agencies, and these expenses should be included in their internal audit program.

Annual purchasing card reviews

All agencies, except for DPC, provided evidence of annual purchasing card reviews for the period of July 2009 to June 2011.

DPC's purchasing card reviews are completed through DTF's internal audit activities under a shared services agreement. DPC sent us the review for 2009–10 and advised that, while DTF excluded DPC from the purchasing card review for 2010–11, the next review will include transactions from the 2010–11 financial year.

Purchasing card internal audit reviews can be improved by examining spending outside of State Purchasing Contracts (SPCs). The importance of this issue is confirmed by our own examination of SPC spending reported in Part 4.

Only two purchasing card reviews by the audited agencies examined this expenditure. These reports found that:

- At DOJ, only 17 per cent of the $2.35 million accommodation expenditure between 1 July 2009 and 31 May 2010 was spent on preferred suppliers. However, we note that this is not a mandatory SPC, and DOJ advised that the use of these preferred suppliers depends on their coverage, availability and price compared to the alternatives.

- At DHS, between October and December 2010, staff purchased stationery and office supplies from non-preferred suppliers to the value of $26 327.

These reports highlight the need and value of this kind of testing.

Personal expense reimbursements

For some agencies the value of reimbursements is similar to, or exceeds, purchasing card expenditures.

We compared the volume of spend committed through purchasing cards and personal expense reimbursements for 2010–11 and found that:

- DPC spent five times as much through personal expense reimbursements compared to purchasing cards

- DOJ and DBI spent approximately equal amounts across the two methods

- DHS and TV spent approximately five times more through purchasing cards.

For DPC, DOJ and DBI, personal expense reimbursements are of a similar or greater magnitude than expenses made using purchasing cards.

TV, DBI and DHS examined the controls for reimbursements through their internal audit programs. The other agencies should also decide how and when to include reviews of reimbursements in their internal audit programs.

2.5 Evidence of effectiveness of controls

In determining whether agencies had been effective in controlling expenditure so that it is legitimate and follows the purchasing rules, we examined:

- agencies’ records of rule breaches

- internal audit reviews that focused on purchasing cards

- a sample of 460 transactions drawn from across the six agencies including purchasing card, travel, hospitality, and reimbursed expenses.

2.5.1 Internal audit results

The annual purchasing card reviews selected a small sample of transactions and statements to test whether the use of purchasing cards complied with the rules. For one agency, DHS, the internal auditors completed more extensive analyses, identifying potential split transactions and breaches of monthly and single-transaction limits.

Overall, the level of unauthorised use was low and related to non-compliance with purchasing rules for transactions that had a legitimate business purpose.

However, there were occasional exceptions to these findings where non-compliance was more frequent or the business purpose was unclear, for example:

- At CFA—in 2010, two out of the 60 transactions examined involved the purchase of alcohol with no documentation to explain the business purpose and three purchases of gifts without evidence of prior approval. Internal audit found that the CFA policy at the time did not provide adequate guidance to employees on these expenses. These types of breaches fell to one out of 60 transactions in 2011. CFA updated its hospitality policy in September 2011 to strengthen approval requirements and to require that business purposes can be demonstrated. Also in 2010, 18 of the 60 transactions tested were not adequately coded in the general ledger, but this fell to three of 60 transactions for the 2011 audit.

- At DBI—the 2010 audit found that 60 per cent, or 146 of the 242 statements tested, had not been reconciled within the agencies’ required time lines. Reasons for this include the delay in obtaining supporting documentation from ministerial and other agency staff who travel overseas. DBI reminded staff of their obligation to acquit statements in a timely manner and the 2011 audit results showed that this widespread breach had been addressed.

- At DHS—the 2011 audit found 46 transactions where invoices had potentially been split to avoid breaching transaction limits and 22 transactions where flowers or other gifts had been purchased without evidence of prior approval as required by the agency’s policy.

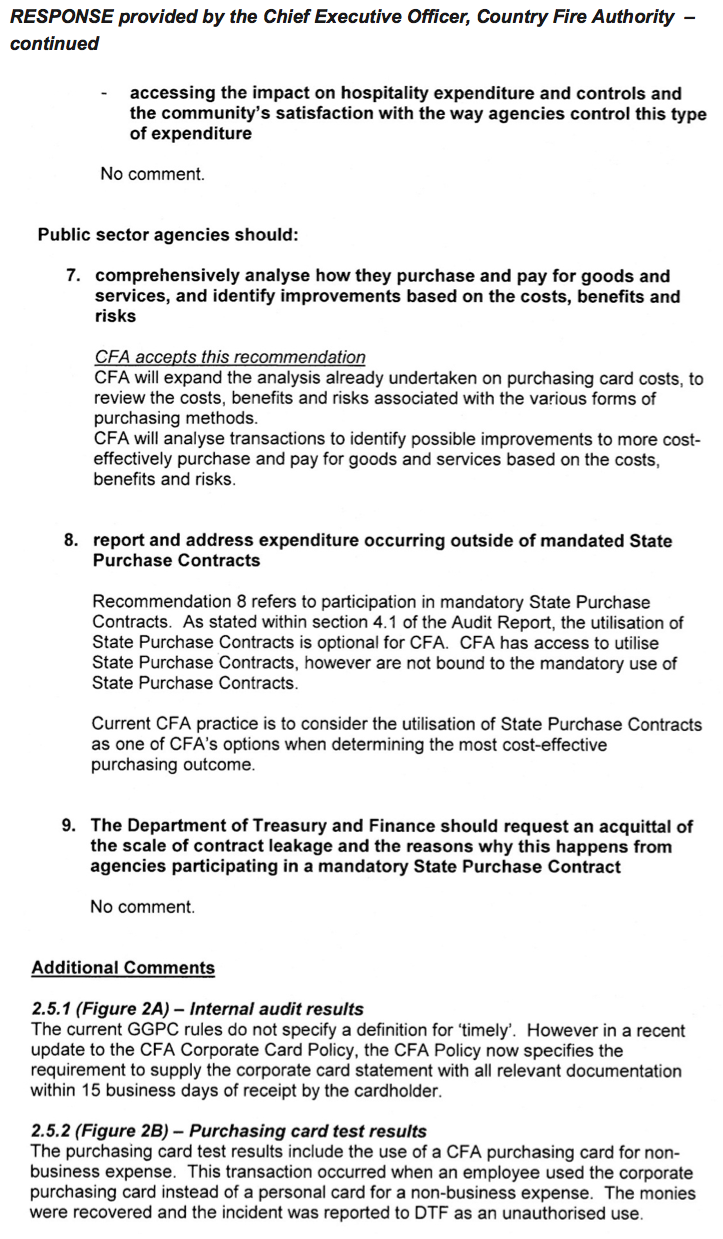

Figure 2A describes the type of purchasing card rule breaches found by internal audits.

Figure 2A

Internal audit rule breaches for purchasing cards 2009–10 and

2010–11

Type of non-compliance |

CFA |

DBI |

DHS |

DOJ |

DPC |

TV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Insufficient supporting documentation |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

Untimely reconciliation of statements |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

Non-compliant purchases―gifts, alcohol and flowers |

X |

X |

||||

Exceeding transaction limits |

X |

X |

X |

|

||

Card used by someone other than the cardholder |

X |

X |

X |

|||

Purchasing cards issued to ineligible persons |

X |

|||||

Splitting card transactions to keep within limits |

X |

X |

||||

Purchase from non-preferred supplier(s) |

X |

X |

||||

Card payment processed without approval |

X |

|||||

Cardholder agreement out of date or not signed |

X |

X |

||||

Inappropriate or unclear general ledger coding |

X |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office analysis of agencies' internal audit reports.

The breaches where the card is used by someone other than the cardholder include:

- A person in the organisation uses a government purchasing card allocated to another employee. This is not allowed but happened in TV on a small number of occasions in 2010 (four out of 423 transactions tested). These purchases were for legitimate business needs but were driven because of the limited access to purchasing cards.

- Card details are obtained and fraudulently used by a third party to purchase goods and services. DOJ identified that this happened for 87 of the 153 rule breaches it reported in 2009–10 and 2010–11. These did not involve improper behaviour on the part of employees because third parties unknown to DOJ personnel obtained card details through their normal use and fraudulently used this information to purchase goods and services.

DBI provided evidence that it has addressed the issues found by internal audit. TV has addressed the issue of ineligible staff having purchasing cards.

2.5.2 VAGO’s testing of transactions

VAGO selected 460 transactions for detailed testing, including 182 purchasing card transactions and a combined total of 278 personal reimbursements, travel and hospitality transactions. We selected these transactions based on analyses of agencies’ expenditure records for 2009–10 and 2010–11 to further test the types of rule breaches identified in internal audit reports.

We found that 7 per cent of all of the transactions tested had breached the rules. In total, one transaction, or less than 1 per cent of the total, involved the use of resources for a non‑business expense. The agency detected and took action to correct this.

Figure 2B and Figure 2C show that we found that a total of 32, or 7 per cent, of transactions, breached purchasing rules—nine involved purchasing card transactions and the remaining 23 involved other types of expenses.

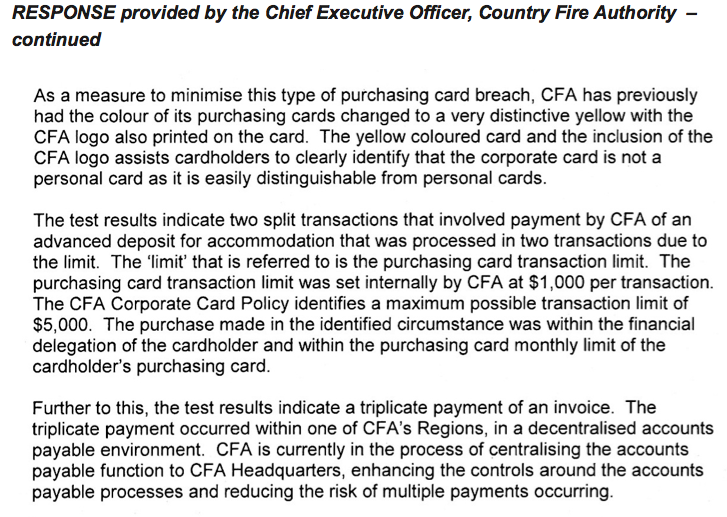

Figure 2B summarises the results of our testing of purchasing card transactions.

Figure 2B

Purchasing card test results

Type of rule breach |

CFA |

DBI |

DHS |

DOJ |

DPC |

TV |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Non-business expense |

1 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

1 |

Insufficient supporting documentation |

– |

– |

– |

– |

3 |

1 |

4 |

Purchase exceeded transaction limit |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

0 |

Split transactions |

2 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

2 |

Processed without approval from authorised signatory |

– |

– |

– |

1 |

– |

– |

1 |

Card used by person other than cardholder |

– |

– |

– |

1 |

– |

– |

1 |

Total rule breaches |

3 |

– |

– |

2 |

3 |

1 |

9 |

Sample size |

43 |

17 |

47 |

33 |

27 |

15 |

182 |

Breaches as a percentage |

7 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

11 |

7 |

5(a) |

(a) We found a total of nine breaches out of 182 samples. This represents 5 per cent.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office analysis of agencies' documentation.

For the purchasing card transactions examined we found:

- One transaction was clearly not for a legitimate business expense at CFA, where one employee used the corporate purchasing card instead of a personal card for a non-business expense. The monies were recovered and the incident was reported to DTF as an unauthorised use.

-

Four transactions had insufficient supporting documentation:

- three transactions at DPC where the supporting documents were not sufficient to establish the business purpose of the transactions. We established their legitimacy but found they needed to be supported by better documentation.

- one transaction at TV where an employee included a mini-bar expense on an accommodation bill for a legitimate business trip. While this should not have been paid for using the purchasing card, we established that the cardholder had arrived at the hotel at a time of night when the mini-bar was the only practical option for food and water. TV acknowledges that the cardholder should have included this information in the supporting documentation and the approver should have detected and questioned this.

Figure 2C summarises the results of our testing for non-purchasing card transactions.

Figure 2C

Personal reimbursements, travel and hospitality expenses test results

Type of rule breach |

CFA |

DBI |

DHS |

DOJ |

DPC |

TV |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Reimbursement claim not signed by authoriser |

– |

– |

– |

1 |

– |

– |

1 |

Insufficient supporting documentation |

2 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

2 |

Invoice not authorised prior to payment |

1 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

1 |

Duplicate or triplicate payment |

4 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

4 |

Expense allocated to inappropriate general ledger code |

14 |

– |

– |

1 |

– |

– |

15 |

Total rule breaches |

21 |

– |

– |

2 |

– |

– |

23 |

Sample size |

61 |

51 |

38 |

62 |

36 |

30 |

278 |

Breaches as a percentage |

34 |

– |

– |

3 |

– |

– |

8(a) |

(a) We found a total of 23 breaches in 278 samples. This represents 8 per cent.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office analysis of agencies' documentation.

We found that 21 of the 23 breaches were for CFA transactions:

- Fourteen involved the inappropriate coding of expenses to a general ledger account code. Four instances happened in 2009–10, five in 2010–11 and we found fourinstances in the first seven months of 2011–12. This appears to be a persistent problem.

- Two involved insufficient supporting documentation; one where the receipt covered only a part of the expense, and one where the supporting documentation was insufficient to explain the reason for the purchase.

- One was for a $152.48 invoice that had not been authorised prior to payment.

-

Four were for multiple payments of the same expense:

- one triplicate payment of a $500 catering invoice. CFA advised that onepayment occurred due to the supplier re-invoicing on a different invoice number, and the other payment occurred due to use of the wrong vendor number, which was not picked up by the accounts payable system

- one duplicate payment of a $700 catering invoice.

CFA are pursuing the recovery of funds from these multiple payments.

Overall, we found 32 exceptions in a sample size of 460. This represents 7 per cent. The majority of these cases were for expenditure that had a legitimate business purposes, but where one of the purchasing rules was not followed. The one expense that did not have a business purpose had been detected and rectified.

This shows that the effectiveness of the control framework around expenses is reasonable. However, agencies must be rigorous in applying all the controls to each transaction. Allowing employees to circumvent the required processes weakens the framework that is in place and increases the risk that funds may be used for illegitimate purposes.

2.6 Reporting and oversight

The reporting and oversight mechanisms intended to provide assurance that agencies are controlling expenditure according to the standing directions are failing because:

- except for DOJ, agencies under-reported unauthorised purchasing card use and DTF did not detect this

- the definition of a ‘significant instance of unauthorised use’ of a purchasing card remains unclear

- two of four agencies that reported significant thefts and losses of more than $1000 did not fully comply with the requirement to provide a separate incident report within two months.

2.6.1 Agencies’ reporting

The standing directions require agencies to report on unauthorised use of purchasing cards, as well as all cases of suspected or actual monetary thefts and losses.

Unauthorised use of purchasing cards

The purchasing card rules define ‘unauthorised use’ as any instance of non‑compliance with the standing directions and rules. These kinds of breaches must be reported to DTF and the Minister for Finance annually for the period ending 30 June. All ‘significant instances of unauthorised use’ must be reported as soon as the inquiry into the incident is complete.

All agencies were made aware of multiple cases of unauthorised purchasing card use through internal audit reviews but only DOJ has reported all of these to the minister in its 30 June report.

The rules do not define what is meant by a ‘significant’ instance of unauthorised use and therefore do not provide enough clarity around this reporting requirement. DTF provided evidence that it had acted to more clearly define when a ‘significant’ instance has occurred.

Only two agencies, DOJ and CFA, maintain registers where they record and track identified purchasing card breaches. It would be beneficial for the other agencies to establish and maintain similar registers, so that management can effectively:

- report all instances of unauthorised use to DTF by 30 June

- report all instances of significant breaches within two months of completing the investigation

- monitor the progress of corrective action

- track the number of times a cardholder has incurred an unauthorised use.

Monetary thefts and losses

All agencies are required to report to DTF and the Minister for Finance on thefts and losses involving money by:

- reporting annually on all cases under $1 000 for the period ending 30 June, together with an incident report

- providing an incident report within two months in cases where the loss is equal to or greater than $1 000.

All agencies provided summarised incident reports with their year-end returns. However, of the four agencies that had more serious incidents of over $1 000 in 2009–10 and 2010–11, only two agencies, CFA and DPC, reported accurately within two months of detecting these cases.

DHS and DBI did not fulfil their reporting requirements because:

- DHS provided only one incident report, despite having two cases above $1 000

- DBI confirmed that it did not report a serious incident within two months, but noted that the inquiry went for an extended period of time and this meant it reported on this incident in its annual return to DTF.

2.6.2 Department of Treasury and Finance oversight

DTF had not adequately reviewed and scrutinised the accuracy of agencies’ reports and did not detect the reporting failures of the agencies.

We confirmed that DTF interprets agencies' responses as having complied with the standing directions, unless they inform DTF otherwise. In late 2011, DTF informed agencies that the absence of reports on the unauthorised use of purchasing cards or thefts and losses would be interpreted as meaning there were no reportable breaches.

DTF must apply greater scrutiny to agencies' submissions under these standing directions.

Recommendations

Public sector agencies should:

- review and increase the level of scrutiny and control applied to

transactions by:

- making greater use of in-built card limits

- running regular, automated tests to detect control breaches and better target detailed reviews

- including reviews of personal expenses in their forward internal audit programs

- review and, where required, strengthen how they document and communicate rules so that staff have a comprehensive understanding of their obligations

- meet the mandatory requirements for reporting unauthorised purchasing card use and thefts and losses.

The Department of Treasury and Finance should:

- improve its communication of changes to the legislated purchasing rules so that agencies have a comprehensive and current understanding of what is required

- significantly improve its scrutiny of agencies’ reporting on breaches of the purchasing card rules and reports on thefts and losses.

- The Department of Premier and Cabinet should evaluate the

effectiveness of the 2012 hospitality guidelines, within two years of their

issue, by:

- confirming that agencies have adequately reflected the revised framework in their individual policies

- assessing the impact on hospitality expenditure and controls, and the community’s satisfaction with the way agencies control this type of expenditure.

3 Efficiently purchasing and paying for goods and services

At a glance

Background

We examined whether agencies had considered the costs, benefits and risks when deciding how to purchase and pay for goods and services.

Conclusion

The agencies included in this audit could not demonstrate that they had efficiently managed the transactions we examined. They could not show that decisions about how to purchase and pay for goods and services had been based on an objective understanding of the costs, benefits and risks of the alternatives.

Findings

Understanding the costs of invoice payment processes is most advanced because five of the six agencies we examined had upgraded these in the past two years. We found that four of the five business cases developed to support this upgrade fell short of requirements of the Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance under the Financial Management Act 1994.

None of the agencies in this audit had, however, documented the costs, benefits and risks of other forms of purchase and payment, such as for purchasing cards, despite this being a mandatory requirement of the standing directions.

An analysis of transactions, and particularly the balance between the use of purchasing cards and reimbursements for small transactions, would address the standing directions' requirement and confirm or improve agencies' efficiency.

Recommendation

Public sector agencies should comprehensively analyse how they purchase and pay for goods and services, and identify improvements based on the costs, benefits and risks.

3.1 Introduction

Agencies can purchase goods and services by:

- issuing cheques or transferring funds to pay for invoices received following an approval to purchase

- settling expenses incurred by employees using a corporate purchasing card

- reimbursing employees for expenses incurred during the course of their work

- allowing employees to use petty cash for low-value expenses.

Each of these methods of purchase has different:

- costs—including the time and money involved in preparing, checking, paying for and auditing transactions

- benefits—including their impact on employees’ effectiveness

- risks—including the likelihood that resources are misused.

The mix of purchasing and payment types that best balances the required levels of control against costs are likely to vary by agency. For example, decentralised agencies, where large numbers of staff need to make frequent, small purchases, will gain most value from the widespread use of credit cards. Smaller, more centralised agencies are more likely to rely on an automated accounts payable system.

In this Part of the report we examine whether agencies followed the requirements of the Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance under the Financial Management Act 1994 (the standing directions) by:

- assessing the costs and benefits of using purchasing cards

- reviewing at least annually whether core financial processes should be upgraded and automated for greater efficiency and effectiveness

- documenting an adequate business case for major financial upgrades, and here we examine the adequacy of agencies' documentation for upgrading their invoice processing systems.

This Part examines how the audited agencies met these requirements of the standing directions.

3.2 Conclusion

Public sector agencies need to demonstrate that the way they purchase and pay for goods and services is effective and efficient.

The agencies included in this audit could not demonstrate that they had efficiently managed the transactions we examined. They could not show that decisions about how to purchase and pay for goods and services had been based on an objective understanding of the costs, benefits and risks of the alternatives.

Four of the five agencies that had invested in more automated and efficient invoice processing did not have documented business cases to inform this change that met the requirements of the standing directions.

3.3 Assessing the costs and benefits of using purchasing cards

A cost-benefit analysis involves comparing the costs, benefits and risks of using purchasing cards with alternative forms of purchase and payment.

Agencies had not:

- quantified the costs, benefits and risks of purchasing cards and the alternative methods of purchase and payment

- explained their rationale for current patterns of procurement.

Without this type of systematic analysis, they cannot provide assurance that their use of purchasing cards and alternative forms of payment is efficient.

The Country Fire Authority (CFA) was the only agency that provided any information on purchasing card costs. It quantified the dollar costs attributed to:

- cardholders’ time for preparing statements and assembling supporting evidence

- managers’ time for reviewing and approving statements

- finance department staff time for processing statements and recording data

- credit card controller time for checking statements

- merchant fees.

The five other agencies provided no evidence that they had estimated the whole‑of‑organisation costs and benefits for purchasing cards and other types of transaction.

None of the agencies had sufficient information to determine whether the balance of transactions between purchasing cards and other forms of purchase and payment took account of the costs, benefits and risks.

Figure 3A shows the amount five of the agencies spent through purchasing cards and personal reimbursements. We could not calculate the information for CFA because of the form of data provided. The Department of Human Services (DHS) and Tourism Victoria have a greater reliance on purchasing cards compared to personal reimbursements. Agencies need to provide assurance that their current purchasing activity reasonably balances the costs, benefits and risks.

Figure 3A

Purchasing card and reimbursed transactions 2010–11

|

Purchasing card |

Personal reimbursements |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Agency |

Number |

$ million |

Number |

$ million |

|

Department of Justice |

15 538 |

3.34 |

10 121 |

4.35 |

|

Department of Business and Innovation |

2 099 |

0.68 |

2 400 |

0.55 |

|

Department of Premier and Cabinet |

71 |

0.03 |

532 |

0.12 |

|

Department of Human Services |

36 127 |

8.90 |

9 869 |

1.60 |

|

Tourism Victoria |

4 351 |

0.92 |

1 582 |

0.17 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office analysis of agencies’ expenditure data.

All agencies should analyse transactions to recommend how to more cost-effectively purchase and pay for goods and services by documenting the:

- type, value and frequency of transactions by the method of payment

- costs of applying for, approving, verifying and reporting on transactions

- business benefits of different forms of purchase and payment

- risks associated with the alternative types of purchase and payment.

3.4 Annual review of financial systems

The standing directions require an annual review of financial systems which should encompass the way agencies manage all types of financial expenditure.

DHS, the departments of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) and Justice (DOJ) provided the clearest and most comprehensive evidence of this type of review:

- DHS included a review of the accounts payable processes that resulted in an upgrade of the Oracle Financials system.

- DPC reviewed their financial systems and developed the State Resource Information Management System, which supports the effective management of the state's financial resources.

- DOJ developed a comprehensive Financial Systems Strategic Plan that reviewed current financial systems and led to the development various projects including Procure to Pay, which included implementing the invoice scanning system.

The remaining three agencies have not fully demonstrated how they have fulfilled the annual review obligation under the standing directions across their financial systems.

However, one area that all the audited agencies had reviewed was the use of automated invoice scanning and we report on this below.

3.5 Business cases for scanned invoice processing

Business cases are required for major financial upgrades. Five of the six agencies' upgrades resulted in scanned invoice processing. One agency, DHS, retained its existing system after investigating the options.

Moving to scanned invoice operation has benefits in terms of reducing the staff time required to raise, approve and process payments and accurately record information about the transaction. For the Department of Business and Innovation (DBI), the upgrade was intended to improve its performance in paying invoices on time, especially to small businesses.

The quality and coverage of the business cases for these investments varied. The standing directions’ guidelines require that business cases quantify the proposed benefits and associated measures, budgets, key risks and actions to address risks.

DOJ’s scanned invoice business case best fulfilled these requirements including:

- benchmarking its ‘as is’ costs of processing invoices against industry norms

- detailed options

- expected benefits, including target values and key performance indicators

- a thorough description of the key risks and mitigation measures

- implementation time lines and the expected cost of the upgrade

- documentation describing how people would be trained to use the new system.

The business cases put forward by the remaining four agencies did not meet the requirements of the standing directions because:

- DPC’s business case, written by DTF under the shared services arrangement, omitted a baseline review, benchmarks, target costs and efficiency savings

- CFA’s business case did not estimate efficiency savings or include risk mitigation

- DBI's (applying to DBI and Tourism Victoria) did not assess the risks or alternatives to the upgrade proposal beyond the option of doing nothing.

While we acknowledge that the DPC upgrade project required only linking existing equipment to form a more efficient system, the business case should still have met the requirements under the standing directions.

DHS decided not to upgrade its invoicing processes. While it did not conduct a formal cost-benefit analysis, it provided documentation that explained why the current non‑centralised method for processing invoices is the department's preferred option. DHS advised that it will engage with those departments that have implemented invoice scanning to reassess whether upgrading to scanning will benefit DHS in the future.

Recommendation

- Public sector agencies should comprehensively analyse how they purchase and pay for goods and services, and identify improvements based on the costs, benefits and risks.

4 Realising the potential of State Purchase Contracts

At a glance

Background

State Purchase Contracts (SPCs) are whole-of-government arrangements for aggregating purchases of goods and services to secure significant discounts. We examined the use and management of the travel services and stationery contracts that are mandatory for departments.

Conclusion

The departments in this audit made significant savings from using these contracts. However, audited departments and the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) have not fully realised potential savings because significant purchasing still occurs outside these contracts. Apart from the Department of Justice (DOJ), departments have not understood or managed contract leakage—spending made outside of these mandatory arrangements. Realising savings through SPCs directly affects the government's savings targets.

Findings

Apart from DOJ, the departments in this audit had not estimated or managed spending outside of the travel and stationery SPCs. DTF confirmed that agencies had not provided them with information on contract leakage by, for example, meeting their obligations to report where they had not complied with government supply policies.

The evidence shows that this gap is significant:

- When first measured in 2008, DOJ's leakage across all mandatory SPCs exceeded 70 per cent for three of nine SPCs.

- Our analysis shows significant spending outside of these contracts occurs, with 14 per cent indicated leakage of the $4.3m air travel spend by three departments.

- Managing leakage is a core requirement if agencies are to realise potential savings and DTF is to effectively monitor and evaluate success.

Recommendations

- Public sector agencies should report and address expenditure occurring outside of mandated State Purchase Contracts.

- DTF should request an acquittal of contract leakage from participating agencies.

4.1 Introduction

State Purchasing Contracts (SPC) provide for the purchase of goods and services across agencies where value-for-money can be achieved by aggregating demand. There are currently 44 active SPCs—29 are mandatory and 15 are optional for departments.

The mandatory SPCs apply to government departments. The Country Fire Authority and Tourism Victoria are only obliged to exclusively use SPCs where these agencies ‘opt in’ to these arrangements. Accordingly the focus of this Part is on government departments.

The Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance under the Financial Management Act 1994 require effective controls over procurement so that public sector agencies comply with government supply policies. These policies include the requirement that agencies exclusively use SPCs where these are mandatory.

Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) guidance material identifies monitoring and reducing expenditure made outside of SPCs as a minimum requirement. The overall management of SPCs is the responsibility of category managers, who report quarterly on the benefits realised and the challenges that need to be addressed.

Departments are required to report annually to the Victorian Government Purchasing Board (VGPB) where they have not fully complied with government’s supply policies, including exclusively using mandatory SPCs.

We examined how well DTF had overseen, and departments had managed SPCs, and we specifically assessed their understanding and management of contract leakage.

4.2 Conclusion

For the travel services and stationery SPCs, participating agencies had secured significant savings and DTF had monitored their use and acted to increase savings.

However, the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) experience and VAGO’s analysis of departments’ expenditure shows that contract leakage is significant. Except for DOJ, we did not find that agencies had:

- understood how much they spent outside of these arrangements

- acted to reduce this expenditure and increase savings

- reported the scale and reasons for non-compliance to category managers, or to VGPB in their annual submissions.

DTF has not effectively overseen agencies’ compliance with the requirement that they purchase exclusively through the whole-of-government contract.

4.3 Understanding and managing contract leakage

Apart from DOJ, the agencies in this audit could not demonstrate that they had estimated or managed contract leakage. The DTF category managers for the travel services and stationery SPCs confirmed that agencies had not provided them with information on contract leakage.

These gaps are significant because:

- DOJ’s experience shows that leakage is likely to be significant and costly

- the analysis of the travel services and stationery SPCs confirms this significance.

Managing leakage is a core requirement if agencies are to realise potential savings and DTF is to effectively monitor and evaluate success.

4.3.1 The Department of Justice’s management of State Purchase Contracts

DOJ stood out as the only audited agency that could show that it had:

- monitored and managed leakage from SPCs

- found ways to manage the stationery SPC to secure additional savings.

Managing leakage from State Purchase Contracts

DOJ commissioned an internal audit review of SPC spending for 2008 and followed this up with three further analyses covering the periods: September 2008 to September 2009, October 2009 to February 2010 and March 2010 to August 2010.

The review generated recommendations and the successive analyses tracked the impact of these changes on contract leakage.

Figure 4A shows how much expenditure happened within SPCs based on the internal audit review in 2008 and strategic analyses between late 2008 and August 2010.

Figure 4A

Percentage of expenditure through State Purchase Contracts

|

Internal audit |

Strategic analyses |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

State purchase contract |

2008 |

Sept 08 – Sept 09 |

Oct 09 – Feb 10 |