Universities: 2015 Audit Snapshot

Overview

The university sector, comprised of the eight Victorian universities, generated a net surplus of $509.1 million for the year to 31 December 2015. This continues a strong financial result for the sector, which has generated similar surpluses in each of the past five years.

The sector has been assessed as a low financial sustainability risk. However, our financial sustainability review noted that the sector has emerging issues regarding longer-term capital renewal, which need to be reviewed and addressed by the universities.

Two universities, Deakin and Melbourne, have received modified audit opinions regarding their treatment of grant funding. These qualified opinions have been issued to both entities for nearly ten consecutive years. Parliament and the public can have confidence in the financial reports of the remaining six universities and 51 controlled entities, who received clear audit opinions for their 2015 financial reports.

We reviewed the governance frameworks in place at universities oversighting the awarding of qualifications to overseas-based international students. This review highlighted issues with the recognition, mitigation and management of reputational and other risks linked to these ventures. The universities are also not reviewing whether the expected benefits of these ventures are being achieved.

Universities: 2015 Audit Snapshot: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER May 2016

PP No 158, Session 2014-16

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Universities: 2015 Audit Snapshot.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

26 May 2016

Auditor-General's comments

|

Dr Peter Frost Acting Auditor-General |

Audit team Simone Bohan—Engagement Leader Helen Grube—Team Leader Kevin Chan—Analyst Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Tim Loughnan |

The university sector, comprised of the eight Victorian universities, generated a net surplus of $509.1 million for the year to 31 December 2015. This continues a strong financial result for the sector, which has generated similar surpluses in each of the past five years. We have assessed the sector as having a low financial sustainability risk.

However, my review of financial sustainability risks has identified some longer-term risks regarding capital renewal. Five of the eight universities have recently built or are building new student accommodation. Most of these buildings are now in use. This expenditure on new assets is potentially masking a lack of spending on replacement assets, and the sector is facing the longer-term risk that its asset base is not being replaced or renewed in a timely manner. Over time, this may result in some assets not being fully fit to provide the services required.

For the financial year ending 31 December 2015, two universities received modified financial audit opinions. Both Deakin University and the University of Melbourne again received qualified audit opinions due to their treatment of grant funding, which did not comply with the Australian Accounting Standards. The universities have not resolved this issue in almost 10 years.

The Australian Accounting Standards Board is currently considering a new accounting standard for the treatment of income by not-for-profit entities, and universities will be expected to implement this new standard.

Parliament and the public can have confidence in the financial reports of the remaining six universities and 44 controlled entities, who received clear audit opinions for their 2015 financial reports. The financial statements of seven controlled entities had not been completed at the time of finalising this report.

During the audits, we raised 60 high- and medium-risk issues relating to the control environments at the eight universities, with 23 of these relating to the IT control framework in place across the sector. Additionally, universities had not resolved 29 per cent of the issues raised by my office in prior years. Universities should aim to resolve these issues as soon as possible to reduce the risk of undetected fraud and error occurring.

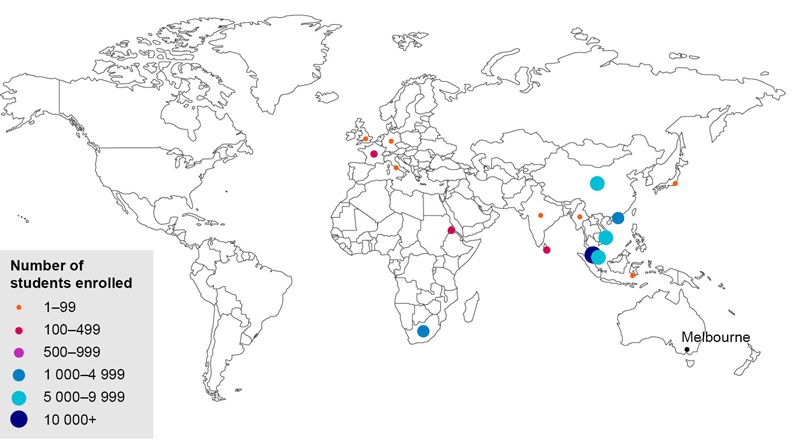

Victorian universities are looking to expand their engagement overseas in a number of ways, including through overseas-based courses that are offered through partnership institutions and overseas campuses. At 31 December 2015, 41 136 students were enrolled in Victorian universities in 16 countries outside Australia.

It is important that the university councils based in Victoria maintain appropriate oversight of these ventures to realise expected benefits and to mitigate risks to the university. This oversight can be improved, particularly regarding the identification and management of reputational and other risks.

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

May 2016

Audit Summary

This report details the outcomes of the 2015 financial audits of the eight Victorian universities and 51 entities they control.

This report also includes a review of the financial sustainability of the sector and discusses the frameworks in place for managing the universities' international operations.

Conclusions

The university sector is in a strong financial position. It has generated a surplus of over $400 million in each of the past five financial years and has an overall low financial sustainability risk. However, emerging longer-term risks regarding asset renewal should be addressed.

This surplus includes audit adjusted figures for two universities, who again received a modified audit opinion regarding their treatment of grant funding in their financial reports. All other entities within the sector who have finalised their financial statements received clear audit opinions, and Parliament and the community can rely on these financial statements.

Our review of the central governance frameworks governing the awarding of Victorian qualifications to overseas-based students indicated that university councils can improve their oversight of these operations, in particular, identifying and mitigating the reputational and other risks arising from these overseas-based ventures.

Findings

Audit reports

Financial audit opinions have been issued for 52 entities within the university sector for the financial year ending 31 December 2015. Parliament and the citizens of Victoria can have confidence in the 50 financial reports that received clear audit opinions. The financial statements of seven controlled entities had not been completed at the time of finalising this report.

Two entities received a modified audit opinion for the financial year ending 31 December 2015. The audit opinions of Deakin University and the University of Melbourne included a qualification regarding their treatment of grant funding, which did not comply with the Australian Accounting Standards. Both of these entities have received this qualification on their financial reports for almost 10 consecutive years.

The Australian Accounting Standards Board is currently considering updating the accounting standards regarding the treatment of income by not-for-profit entities. Universities will need to monitor and seek to comply with the new standard once it is released.

In conducting our financial audits, we noted that the financial reporting internal controls at the eight universities, to the extent we tested them during our audit, were adequate for the preparation of each universities' financial report. We raised 60 high- and medium-risk control-related issues in our 2015 management letters, with 23 of these relating to the IT control framework in place across the sector.

Universities should aim to resolve these issues as soon as possible to reduce the risk of undetected fraud and error occurring. Our audits noted that universities had not resolved 29 per cent of the issues raised by VAGO in prior years.

Financial sustainability risks

At 31 December 2015, the university sector—consisting of the consolidated results of the eight universities—reported a combined net surplus of $509.1 million ($534.6 million in 2014) and jointly held net assets of $15.1 billion. The sector held cash and investment assets of $4.0 billion at 31 December 2015. This is the fifth consecutive year that the sector has made a surplus of over $400 million.

Based on our analysis of four risk indicators, the sector continues to face a low overall financial sustainability risk driven by these strong surpluses. However, at an individual level, some universities are starting to face emerging short- and longer‑term risks.

Two universities, Monash and RMIT, have been assessed as having a high liquidity risk for each of the past five years. However, both universities have significant longer-term investments that could be drawn upon if needed for cash flow purposes, negating the risk. We have reviewed the cash management policy, practices and oversight in place at Monash University during the 2015 financial year and found that the university has a clear liquidity policy—although it does not use the same calculation as our indicator—and good oversight of its investments.

In the longer term, our analysis of the capital replacement indicator—which assesses spending on fixed assets against the annual depreciation expense—showed that universities are not spending as much on renewing or replacing assets as they are consuming each year. The capital replacement indicator does not differentiate between expenditure on new or replacement assets. As such, the spending by five universities on new student accommodation assets—where directly funded by the universities—potentially masks a deeper issue regarding the replacement and renewal of existing assets.

It is recommended that universities continue to monitor their asset replacement programs and ensure that the assets they hold continue to be fit for service.

International operations

Victorian universities have sought to expand their international presence and to engage with institutions, businesses, students and communities overseas. These opportunities can bring reputational and financial benefits to the university, but there are also risks associated with these activities.

In 2015, 41 136 students based in 16 countries outside Australia were enrolled in Victorian university qualifications in those countries. These students are predominantly based in Asia, but also Europe and America. The university sector generated $202.5 million in revenue from these activities.

It is important that the relevant Victorian university councils are able to monitor and oversee the risks and rewards associated with these activities. Our review of these arrangements highlighted that the reputational and other risks to the universities arising from these international activities are not being identified, mitigated and managed through the universities' risk management processes. This is consistent with our 2002 report regarding universities' international overseas campuses.

Our review of three universities where qualifications are awarded to overseas-based students noted that we could not determine the level of oversight by Swinburne University regarding the financial aspects of its Malaysian campus due to a lack of documentation. However, RMIT University demonstrated effective oversight of RMIT Vietnam, a wholly owned overseas campus. None of the three universities reviewed are monitoring whether or not the expected benefits of these international engagements are being realised.

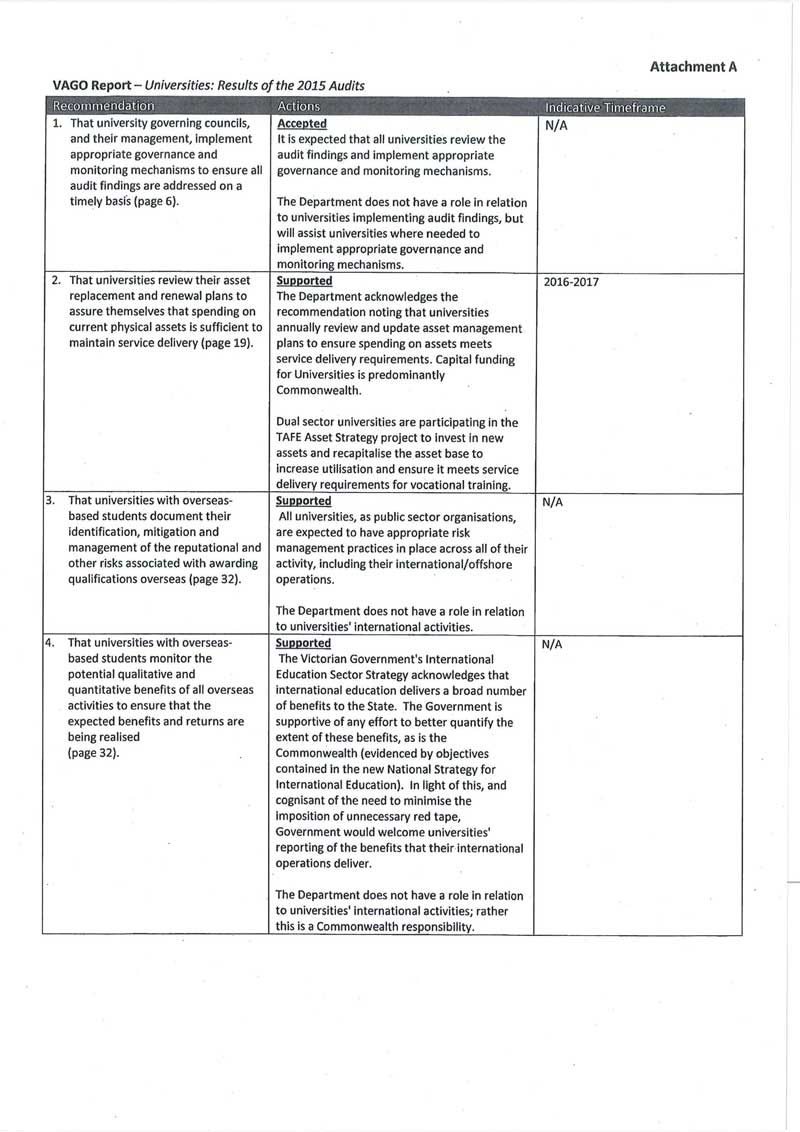

Recommendations

- That university governing councils and their management implement appropriate governance and monitoring mechanisms to ensure all audit findings are addressed in a timely manner.

- That universities review their asset replacement and renewal plans to assure themselves that spending on current physical assets is sufficient to maintain service delivery.

- That universities with overseas-based students document the identification, mitigation and management of reputational and other risks associated with awarding qualifications overseas.

- That universities with overseas-based students monitor the potential qualitative and quantitative benefits of all overseas activities to ensure that the expected benefits and returns are being realised.

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with the Department of Education & Training and the eight Victorian universities throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report, or relevant extracts to those agencies and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix E.

1 Context

1.1 Report coverage

This report provides information on the outcomes and findings of the 2015 financial audits of the eight universities and the 51 entities they control. Appendix A details the entities included in this report.

Figure 1A outlines the structure of this report.

Figure 1A

Report structure

Part |

Description |

|---|---|

Part 1: Context |

Discusses the outcome of the 2015 financial audits and the internal control issues identified across the sector. |

Part 2: Financial outcomes |

Comments on the financial outcomes of the university sector over the five-year period to 31 December 2015, including discussion of key financial issues impacting the 2015 financial statements. |

Part 3: International operations |

Highlights the range of international activities universities are involved in and reviews the governance and risk management in place regarding the awarding of qualifications to international overseas-based students. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

Parliament should be aware that the Auditor-General has given information to a person or body under section 16(f) of the Audit Act 1994 during the conduct of the audit.

The total cost of this report was $140 000.

1.2 Financial audit outcomes for 2015

1.2.1 Financial audit opinions

At the time of tabling, the financial audits of the 2015 financial reports of the eight Victorian universities and 44 of their 51 controlled entities had been completed. Clear audit opinions were issued for six of the universities and the 44 controlled entities. The financial statements of seven controlled entities had not been completed at the time of finalising this report.

Modified audit opinions

A modified audit opinion is issued when the auditor cannot be satisfied that the financial report is free from material error, or when the financial report is materially different to the relevant financial reporting framework.

For the year ending 31 December 2015, modified audit opinions were issued to Deakin University and the University of Melbourne. Both were qualified because their recognition of Commonwealth Government grant income was not in accordance with the Australian Accounting Standards. This qualification is an ongoing issue—the University of Melbourne has received a qualified audit opinion because of this issue each year since its financial report for the year ending 31 December 2006, and Deakin University since 31 December 2007.

Each of these entities elected to treat Commonwealth grant income as a 'reciprocal transfer', thereby only recognising revenue in the reporting periods when the grant money was spent. In the interim, unspent grant income is recognised as a liability in the balance sheet. This means that if funding is received in December 2015 but not spent until May 2016, the revenue would only be recognised in the 2016 year.

However, this funding is 'non-reciprocal' in nature and should be recognised as revenue in the financial year it is received, to accord with the requirements of the Australian Accounting Standards—particularly AASB 1004 Contributions (AASB 1004). Grant funding received in December 2015 should be recognised as revenue in the 2015 financial year because this is when the university gains control of the funds.

The qualified audit opinions detail the balances impacted by the differences in revenue recognition, and the impact this would have on the retained surplus of the entity at 31 December 2015.

Figure 1B summarises the impact of the qualification for these two universities at 31 December 2015.

Figure 1B

Impact of qualifications in the

university sector at 31 December 2015

Financial report line item |

Balance as per financial report ($ million) |

Audit adjustment for 2015 financial year ($ million) |

Balance with audit adjustment ($ million) |

Audit adjustment for 2014 financial year ($ million) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

University of Melbourne |

||||

Other liabilities (current and non‑current) |

414.6 |

213.0 ↓ |

201.6 |

217.0 ↓ |

Australian, state and local government financial assistance income—grant income which should have been recognised:

|

1 059.0 1 063.3 |

213.0 ↑ 217.0 ↓ |

1 272.0 850.3 |

217.0 ↑ 226.0 ↓ |

Impact on net earnings |

142.3 |

4.0 ↓ |

138.3 |

9.0 ↓ |

Retained earnings |

1 517.5 |

217.0 ↑ |

1 734.5 |

226.0 ↑ |

Deakin University |

||||

Trade and other payables |

202.3 |

27.9 ↓ |

174.4 |

27.9 ↓ |

Australian, state and local government financial assistance income—grant income which should have been recognised:

|

613.6 581.1 |

18.9 ↑ 18.9 ↓ |

632.5 562.2 |

18.2 ↑ 23.5 ↓ |

Impact on net earnings |

68.0 |

Nil impact |

68.0 |

5.3 ↓ |

Retained earnings |

1 253.3 |

27.9 ↑ |

1 281.2 |

33.2 ↑ |

Note: ‚ ↓ = reduce by, ↑ = increase by.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In Part 2, our analysis of the financial sustainability risks of the universities for the past five financial years ending 31 December 2011 to 2015 assesses these universities based on balances that include the above audit adjustments.

Potential changes to the Australian Accounting Standards

In April 2015, the Australian Accounting Standards Board released Exposure Draft 260: Income for not-for-profit entities (ED 260) for comment. The draft provides details of potential changes regarding the recognition of grant and other types of income currently recognised in accordance with AASB 1004.

If the changes proposed in ED 260 are adopted, then a new Australian Accounting Standard regarding the recognition of income by not-for-profit entities will be published.

As detailed in ED 260, the changes would require universities to recognise grant funding income in one of two ways:

- If the funding comes from a contract that contains details of services that the university is to provide, and to whom, then the university can recognise the income as its obligation is fulfilled, over multiple years if required, in accordance with AASB 15 Revenue from contracts with customers.

- If the funding is received without these performance obligations, then the university should recognise the income when it obtains control of the funding—which is determined as when the entity can direct the use of, and obtain substantially all of the benefits from, the asset.

It is important that universities comply with any changes to the Australian Accounting Standards. All universities need to keep informed about pending changes relating to the accounting standard requirements for income recognition and ensure that they are adequately prepared to implement the new accounting standard from the anticipated start date of 1 January 2018.

1.2.2 General internal controls

We reviewed the financial reporting internal controls in place at universities and, to the extent that these controls were tested through our audits, we found these controls were adequate for the fair preparation of the universities' financial reports.

However, we identified a number of instances where important internal controls need to be strengthened. These weaknesses were reported to the council, Vice-Chancellor and audit committee of each university through a formal letter, called a management letter. Typically, two management letters are provided throughout a financial audit—an interim and a final. Each identified issue receives a risk rating. See Appendix B for more information about the risk ratings used.

In 2015, 60 high- and medium-rated control weaknesses were reported to the entities through management letters. Figure 1C summarises the control weaknesses reported.

Figure 1C

2015 control issues identified

by audit at the eight universities

Area of issue |

Risk rating of issue | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Extreme |

High |

Medium |

Total |

||

Assets |

– |

– |

4 |

4 |

|

Expenditure / Accounts payable |

– |

2 |

4 |

6 |

|

Financial reporting |

– |

5 |

13 |

18 |

|

Governance |

– |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

IT controls |

– |

10 |

13 |

23 |

|

Payroll |

– |

– |

4 |

4 |

|

Reconciliations |

– |

– |

1 |

1 |

|

Revenue |

– |

– |

1 |

1 |

|

Total |

– |

18 |

42 |

60 |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Thirty-eight per cent of the issues identified relate to the IT control environment in place at the universities. Universities, as with other public sector entities, are heavily reliant on IT systems, and control weaknesses in these systems increase the risk that material errors or fraudulent activity will occur and may not be detected.

Of the 23 IT control issues noted in Figure 1C, 10 related to either poor user access or poor password controls. Four issues were raised regarding weaknesses in disaster recovery programs.

Universities should address all the issues raised to remove potential weaknesses in their control frameworks. Recommended time lines for the resolution of these issues are included in the rating definitions in Appendix B.

Status of prior period issues

The status of internal control weaknesses identified in prior periods is presented and communicated to universities and their audit committees through the current year's management letters. These issues are monitored to ensure previously identified weaknesses are resolved promptly. Figure 1D shows the resolution status of internal control weaknesses from prior periods by risk.

Figure 1D

Prior period internal control weaknesses—resolution status by risk

Risk rating |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Area of issue |

Extreme |

High |

Medium |

Total |

Unresolved |

– |

– |

12 |

12 |

Resolved |

– |

5 |

25 |

30 |

Total |

– |

5 |

37 |

42 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Of the 42 issues raised in prior years, 28.6 per cent remain unresolved by the universities as at 31 December 2015. Universities should seek to resolve the remaining outstanding issues as soon as possible.

Recommendation

- That university governing councils and their management implement appropriate governance and monitoring mechanisms to ensure all audit findings are addressed in a timely manner.

2 Financial outcomes

At a glance

Background

To be financially sustainable, universities need to be able to meet their current and future expenditure as and when it falls due. They also need to be able to absorb the financial impacts of any changes and financial risks that materialise, without significantly changing their revenue and expenditure policies.

Conclusion

The university sector has been assessed as having a low overall financial sustainability risk as at 31 December 2015. However, the individual university results flag some high risks in liquidity and capital replacement that need to be monitored and managed.

Findings

- The university sector made a combined net surplus of $509.1 million for the financial year ending 31 December 2015 ($534.6 million in 2014).

- Two universities, Monash and RMIT, have high liquidity risks for each of the past five years. In both cases liquidity is less than 0.75, meaning the university has only 75 cents in liquid assets for every $1 in current liabilities.

- Monash University has cash management processes in place and manages in accordance with a liquidity policy. In particular, the university council has oversight of the university's cash management processes.

- Three universities have been assessed as having a high capital replacement risk, indicating that these universities are not renewing or replacing assets at the rate they are being consumed.

Recommendation

That universities review their asset replacement and renewal plans to assure themselves that spending on current physical assets is sufficient to maintain service delivery.

2.1 Introduction

This part looks at the collective financial position of the eight universities and their financial outcomes for 2015. It details the main drivers behind the net result achieved by the sector and analyses the sector against four financial sustainability risk indicators.

2.2 Conclusion

The financial position and outcomes of the Victorian university sector demonstrate that the sector is financially sound. Our analysis of the sector as a whole assessed only low risks across all four financial sustainability indicators. However, the individual university results flag some high risks in liquidity and capital replacement that need to be monitored and managed.

2.3 Financial overview of the sector

At 31 December 2015, the university sector—consisting of the consolidated results of the eight universities—reported a combined net surplus of $509.1 million ($534.6 million in 2014).

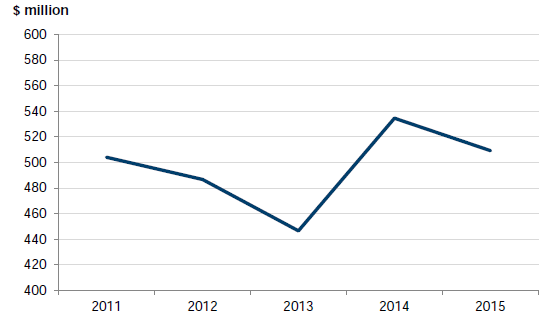

Figure 2A shows the net results of the university sector for the past five years.

Figure 2A

Net result of university sector for the five years ending 31 December

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure 2A illustrates that the university sector consistently reports positive results year on year. The peak in 2014 was largely due to two universities realising profits on financial investments when they altered the nature of those investments. In the absence of any such realisations in 2015, the net profit for the sector declined slightly.

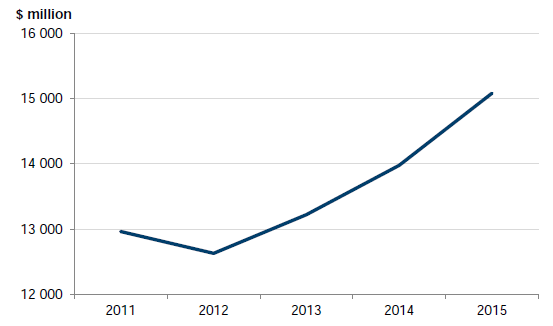

The university sector maintains a strong position with net assets of $15.1 billion at 31 December 2015, as shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2B

Net assets of the university sector for the five years ending 31 December

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The net assets held by the sector increased by $1.1 billion over 2015. Half of this relates to the net surplus result. The remainder reflects an increase of $1.0 billion in the value of fixed assets held, partly offset by an increase in interest-bearing borrowings of $244.0 million. At 31 December 2015, the university sector's net assets included cash holdings of $0.8 billion, other investments of $3.2 billion and interest-bearing liabilities of $1.0 billion. The university sector held $13.3 billion in fixed assets.

Five of the eight Victorian universities invested in, or were in the process of investing in, student accommodation infrastructure in 2015. Four of these are being built as new purpose-built accommodation. Deakin University is renovating/repurposing an existing building. The total value of these projects across the five universities is $470.8 million. A summary of the student accommodation projects is shown in Figure 2C.

Figure 2C

Student accommodation investment by Victorian Universities as at 31 December 2015

|

University and campus location |

Project description |

Funding method |

Project status |

Cost of project ($ million) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Deakin University |

||||

|

Waurn Ponds |

Construction of 309 residential studio apartments to increase the availability and affordability of on-campus accommodation. Apartments will have access to shared facilities and student support services. |

NRAS funding and internal financing(a) |

Completed November 2015 |

38.9 |

|

Burwood |

Construction of purpose-built 505-bed student residence, with 174 car parks. |

Internal financing |

In progress— March 2017 completion date |

73.6 |

|

Geelong |

This project involves the acquisition and conversion of the T&G Building at 157 Moorabool Street, Geelong. The five-level building will be refurbished into 33 self-contained student dwellings with access to shared services. The ground level of the building will retain existing commercial tenancies. |

Internal financing |

In progress—June 2016 completion date |

10.6 |

|

Monash University |

||||

|

Clayton |

Construction of 1 000 new student beds across four buildings, with shared facilities. |

Borrowings (from international sources) |

Completed November 2015 |

153.0 |

|

RMIT University |

||||

|

Bundoora West |

Construction of a new building with 370 student beds. |

Internal financing |

Completed February 2016 |

50.5 |

|

University of Melbourne |

||||

|

Parkville |

Construction of 648-bed accommodation facility. The university entered into an arrangement where student accommodation will be constructed and operated by a private-sector body on university land under a 38-year lease. Ownership of the complex reverts to the university in 38 years. |

Build, Own, Operate, Transfer (BOOT) |

Completed March 2016 |

87.4(b) |

|

Victoria University |

||||

|

Footscray |

The university entered a private partnership agreement to lease the land it owns at 101 Ballarat Road, Footscray, to a private enterprise to develop and operate a 500-bed accommodation complex. Ownership of the complex reverts to the university in 35 years. |

Public private partnership (PPP) |

Completed February 2016 |

56.8(b) |

(a) Deakin University funded this project through $7.7 million in funding from the National Rental Affordability Scheme (NRAS) and through internal financing.

(b) Project costs of building the asset incurred by the private partner in the agreement, not the university.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

2.4 Risks to financial sustainability

To be financially sustainable, universities need to be able to meet their current and future expenditure as it falls due. They also need to be able to absorb the financial impacts of any changes and financial risks that materialise, without significantly changing their revenue and expenditure policies.

Financial sustainability should be viewed from both a short- and long-term perspective. Short-term indicators relate to the ability of an entity to maintain positive operating cash flows, or the ability to generate an operating surplus over the short-term. Long‑term indicators focus on an entities' ability to fund significant asset replacement or to minimise future financial sustainability risks.

In this section, we provide insight into the financial sustainability risks of the university sector at 31 December 2015 and trends over a five-year period. The indicator results are calculated using the consolidated financial transactions and balances of all the universities. Where qualifications have been issued, the results used have been adjusted by audit for the qualification, as discussed in Section 1.2.1.

The indicators highlight risks, however, forming a definitive view of any entity's financial sustainability requires a holistic analysis that moves beyond historical financial considerations to also include the financial forecasts, strategic plans and their operations and environment.

Appendix C describes the financial sustainability indicators, risk assessment criteria and benchmarks that are used in this report, and details the changes made to the indicators since our previous report Universities: 2014 Audit Snapshot (May 2015). The results for all five financial years across the four indicators for each individual university have been recast and disclosed in Appendix C, based on the updated financial sustainability indicators.

2.4.1 Overall analysis

Figure 2D provides a snapshot of the financial sustainability risk ratings for the sector at 31 December 2015.

As noted in Part 1, Deakin University and the University of Melbourne received a modified audit opinion. Our analysis below has been completed based on the audited financial report for these entities, adjusted for the qualification issue as detailed in Figure 1B.

Figure 2D

Financial sustainability risk indicators for the university sector at 31 December

|

Indicator |

Average across sector entities per year |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

|

|

Net result |

8.79% |

7.65% |

5.45% |

4.32% |

4.79% |

|

Liquidity |

1.68 |

1.50 |

1.47 |

1.16 |

1.27 |

|

Capital replacement |

2.77 |

2.71 |

2.10 |

1.52 |

1.66 |

|

Internal financing |

1.32% |

123% |

107% |

187% |

168% |

Note: A green result is a low-risk assessment.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

At a sector level, there are no short- or long-term sustainability risks. This is consistent with the strong net results and positive net asset positions at 31 December 2015. However, within the sector, the results for some universities have flagged emerging risks that need to be monitored and managed. A discussion of each individual indicator follows.

As at April 2016, the Australian Government is still considering if any changes will be made to the federal funding model for universities. While there is little detail of the proposed changes at this point, it is expected that this will reduce the level of federal funding provided to universities. The sector will need to promptly review and adjust its business models to ensure that any funding changes do not result in an increased financial sustainability risk.

2.4.2 Net result

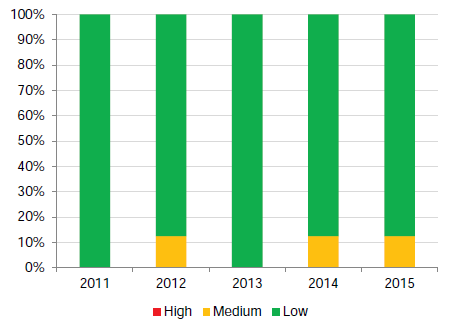

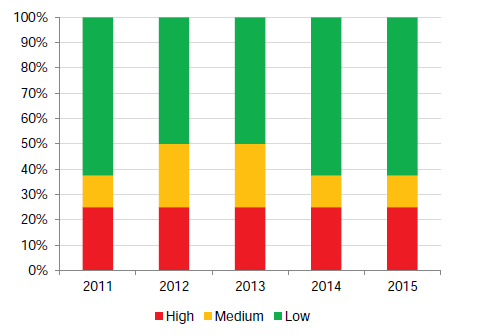

The universities largely continue to report strong net surpluses. As displayed in Figure 2E, consistent positive net surpluses have been reported for the past five years by all universities except Victoria University. It is the only university to receive a medium-risk rating for this indicator over the past five years.

Figure 2E

Universities' net result risk indicators as at 31 December

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Victoria University has had a net deficit outcome in three of the past five years. The deficits in 2014 and 2015 were driven by the university's redundancy program—costing $16.8 million in 2014 (contributing to the deficit of $15.6 million) and $15.3 million in 2015 (deficit of $11.8 million).

2.4.3 Liquidity

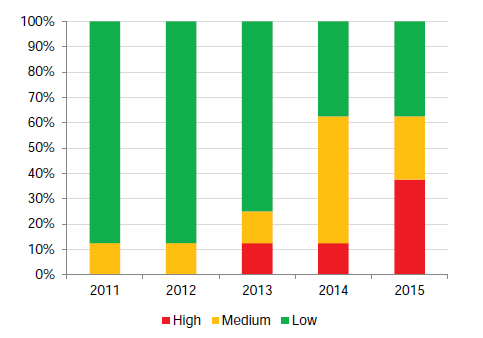

The liquidity of universities varies, but the individual results for each university are largely consistent year on year. This is demonstrated in Figure 2F and indicates that universities are making strategic choices regarding short-term versus long‑term investments based on cash flow needs.

As detailed in Appendix C, this calculation is derived from the reported current assets and current liabilities of the university as per its audited financial reports. No adjustments have been made to adjust for current liabilities relating to employee benefits that are not likely to be paid out within the next 12 months.

Figure 2F

Universities' liquidity risk indicators as at 31 December

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Two universities, Monash and RMIT, have been as assessed as having a high liquidity risk for each of the past five years. In both cases, liquidity is less than 0.75, meaning the university has less than 75 cents in liquid assets for every $1 in current liabilities. However, both universities have significant longer-term investments that could be drawn upon if needed for cash flow purposes, negating the risk.

This year we conducted further analysis of Monash University's cash management practices, which is discussed in Section 2.5. While the university has cash management processes and oversight in place, liquidity is still a risk if short-term cash management forecasting is not accurate.

2.4.4 Capital replacement

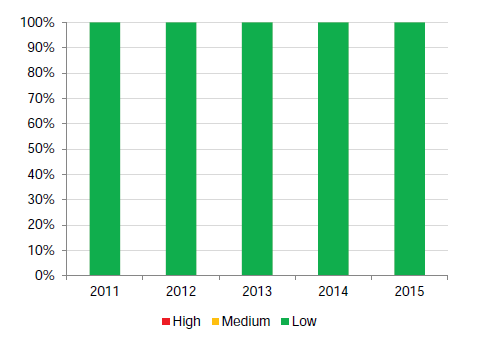

In our 2014 report, we flagged an emerging risk that capital replacement was declining in the university sector. The results for 2015 in Figure 2G show that the decline has continued.

Figure 2G

Universities' capital replacement risk indicators as at 31 December

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Three universities have been assessed as high risk in 2015, an increase on 2014 and 2013, when only one university was flagged as high risk. A high capital replacement risk indicates that the university consumed more assets than it built or regenerated in the year.

This indicator does not differentiate between expenditure on new or replacement assets. As such, spending on new student accommodation during the 2015 financial year, where funded directly by the university, will be included in the assessment. Spending on new assets may mask a lack of investment in existing asset replacement.

Over time, the impact of this is that the condition of assets may decline and they may cease being suitable for use. Universities need to be measuring asset consumption and asset condition so that they become aware if this capital replacement risk materialises.

2.4.5 Internal financing

Results for the internal financing ratio show that this is an area of strength and opportunity—all universities were assessed as low risk, as depicted in Figure 2H. This means all universities generated enough cash from operations to fund new assets or asset renewal.

Figure 2H

Universities' internal financing risk indicators as at 31 December

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

All universities scored strongly for the internal financing indicator, exceeding the 35 per cent benchmark we set for universities to be considered low risk.

The internal financing indicator should be read in conjunction with the capital replacement results, with one indicating whether funds should be available for asset investment and the other indicating whether asset investment is occurring at an appropriate level compared to consumption. When taken together, the low-risk ratings for internal financing and the emerging higher-risk ratings for capital replacement indicate that universities have the opportunity to be investing more in assets to maintain the current level of service provision.

2.5 Monash University cash management

Since 2011, we have assessed Monash University as having a high liquidity risk, as shown in Figure 2I.

As detailed in Appendix C, the calculation we use to calculate liquidity is current assets divided by current liabilities held at the 31 December each year.

Figure 2I

Liquidity risk rating for Monash University at 31 December

|

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Liquidity |

0.42 |

0.46 |

0.45 |

0.42 |

0.47 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

As per our May 2015 report Universities: 2014 Audit Snapshot, in response to our assessment, Monash University has noted that it has a strong cash management strategy in place, and our indicator is a 'point-in-time' measurement.

2.5.1 Conclusion

We have reviewed the cash management policy, practices and oversight in place at Monash University during the 2015 financial year. The university has a clear liquidity policy—although it does not use the same calculation as our assessment—and strong oversight regarding its investments.

2.5.2 Policy

The Monash University liquidity policy seeks to maintain a set liquidity ratio throughout the financial year.

The calculation used in the policy is different to the standard methodology of calculating liquidity. The calculation used is current assets plus financial investments divided by current liabilities. It is university policy to maintain this ratio between 1.5 and 3.0.

Our analysis of the financial statements for 2011 to 2015 shows that this ratio was achieved for three of the five financial years, 2013 to 2015.

2.5.3 Management practices

Monash University invests its funds into two pools—one short term and one long term. The short-term pool is primarily used to manage day-to-day cash flow requirements, and any surplus cash is invested in term deposits until the funds are required. The long-term pool is aimed at maximising returns within an acceptable level of risk so that funds are available for future expenditure.

We have focused on the short-term pool, as the liquidity calculation is a short-term measure.

The amount of cash in the short-term pool fluctuates considerably during the financial year. The university receives significant cash receipts at two key points in the year, being the start of the university semesters. However, expenditure, such as staff salaries, occurs consistently throughout the year.

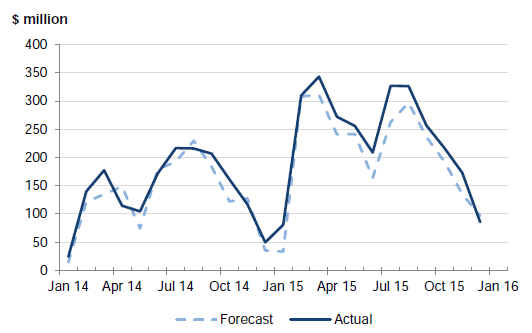

Figure 2J shows the forecast and actual balances of the short-term pool for the past two financial years. This graph illustrates the 'peak and trough' nature of the short-term pool. As a result of the university's cash flow patterns, the university's liquidity is lowest at balance date.

Figure 2J

Short-term pool cash balance for the period 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2015

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The university operating bank account, from which most expenditure is paid, is part of the short-term pool. Limited funds are held in the operating account—usually enough for the day's expected transactions—and it is therefore critical that cash flow forecasts are accurate and the liquidity buffer is sufficient to ensure money can be transferred to the operating account when it is needed. These forecasts are reviewed and updated on a daily basis.

Using the end of each month as an illustration of the daily process, Figure 2J shows that the university is generally accurate in its forecasting of the cash required in the short-term pool to meet daily expenditure obligations. The gap between actual and forecast was greater in the second 12 months.

If management's projections of cash requirements are not accurate, there is a risk that the operating bank account may be in overdraft. An overdraft generally incurs additional bank fees and may mean payments are not processed in a timely manner.

The university's operating bank account was overdrawn on three occasions during the 2015 financial year. The short-term pool also includes other externally managed cash accounts which hold easily accessible funds. These are contingency funds that can quickly be moved into the operating account if required.

2.5.4 Oversight

Figure 2K shows the key groups and their responsibilities in managing the university's investments and short-term pool.

Figure 2K

Key groups and responsibilities

|

Group |

Responsibilities |

|---|---|

|

Resources and Finance Committee (RFC) |

This is a subcommittee of the university council. RFC has a governance oversight role, approving investment policy and strategy. |

|

Investment Advisory Committee (IAC) |

A subcommittee of RFC which has a management oversight role. It monitors and reviews investments relative to strategy and approves investment management appointments. |

|

External advisors |

Independent consultants engaged to review performance of investments and provide recommendations to IAC. |

|

Treasury Division |

University employees responsible for daily cash management processes and administering outsourced arrangements with fund managers. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Monash University Council has effective oversight of the university's cash management function. Through the groups in Figure 2K, the university council has a high level of involvement in the strategic direction of investment policies and actions.

RFC consists of eight members, including the Chancellor and four university council members. The RFC's terms of reference require it to review and monitor the university's financial performance and to advise the council on financial investment matters.

RFC is supported by the advice of IAC, which consists of two council members, including the chair, and up to three independent members. These independent members are experienced financial service and board members. IAC is expected to recommend investment objectives and strategies to RFC and the university council, based on members' knowledge and other external expert advisors. These advisors are independent consultants engaged to evaluate the performance of the university's investments. IAC's terms of reference include monitoring and oversight of the short‑term and long-term investment pools, based on management reports prepared by the Treasury Division. It is the IAC's responsibility to monitor the achievement of the university's liquidity policy.

Recommendation

- That universities review their asset replacement and renewal plans to assure themselves that spending on current physical assets is sufficient to maintain service delivery.

3 International operations

At a glance

Background

Victorian universities have a variety of ways in which they can engage with institutions, businesses, students and communities internationally, including through the awarding of Victorian qualifications to overseas-based students. This part looks at the governance and risk management arrangements in place to enable these operations to be overseen by the university councils, based in Victoria.

Conclusion

University councils can improve their oversight and monitoring of the reputational and financial aspects of overseas operations. This is consistent with our findings in 2002 and shows that university councils continue not to learn the lessons from our previous work.

Findings

- As at 31 December 2015, 41 136 overseas-based students were enrolled in qualifications offered by Victorian universities, across 16 countries, generating $202.5 million in revenue.

- Victorian universities are not reporting the reputational and other risks linked to awarding qualifications to overseas-based students in their risk registers. This means there is no tracking of the risks and no clear documentation on how they are being mitigated and managed. RMIT University is the exception, demonstrating effective oversight of RMIT Vietnam, a wholly owned overseas-campus.

- Victorian universities are not monitoring whether the benefits of setting up their international operations are being realised.

Recommendations

That universities with overseas-based students:

- document the identification, mitigation and management of reputational and other risks associated with awarding qualifications overseas

- monitor the potential qualitative and quantitative benefits of all overseas activities to ensure that the expected benefits and returns are being realised.

3.1 Introduction

In today's global economy, Victorian universities are seeking to make the most of opportunities available to them through increased international engagement. Universities are using a variety of channels to build up their international presence, including building partnerships with overseas universities, developing business relationships and offering students based outside Australia the chance to gain qualifications offered by Victorian universities.

When operating overseas, Victorian universities are exposed to both risks and rewards.

We first commented on universities' international engagements in our Report on Public Sector Agencies (June 2002). In that report, we identified the opportunities afforded to Victorian universities undertaking international operations—enhanced revenues, university profile, staff development and student mobility. The report also noted that universities should be ensuring that they monitor the delivery of these benefits from their international operations.

Those potential upsides are still valid in 2016—the risks with international operations can be both financial and reputational. The financial risks are particularly important given it is public money the universities are investing, therefore, any losses incurred represent a loss of public funds. Management and oversight of international operations is crucial to both maximise rewards and manage risks.

The purpose of this part is to review the governance frameworks in place at a selection of universities to monitor and oversee their international operations.

3.2 Conclusion

University councils can improve the oversight and monitoring of the qualitative and quantitative aspects of overseas operations. University councils were not able to demonstrate that they were monitoring the actual benefits of overseas operations, nor documenting the mitigation of risks. This is consistent with the conclusions in our 2002 report and, therefore, the sector has largely continued not to learn the lessons from our previous work.

3.3 International engagement

As at 31 December 2015, the eight public Victorian universities had set up formal arrangements to undertake a variety of international study, business and research opportunities. The types of engagement include:

- operating overseas campuses, as subsidiaries and through joint ventures

- offering branded courses through partner universities

- forming partnerships for research and teaching facilities

- reaching formal agreements with overseas universities to share knowledge and partake in student exchange programs

- advertising for and enrolment of international students, for study both in Victoria and overseas

- forming partnerships or agreements with international businesses for research and funding

- engaging individual staff through arrangements with overseas universities/businesses for teaching/consultancy contracts.

This part focuses on the first two of types of engagement—overseas campuses and branded courses. In particular, we have focused on the oversight and governance of these arrangements by the Victorian-based university councils through their risk management frameworks.

Our 2002 report noted that the success of the international arrangements relies upon an effective business plan, which should be underpinned by comprehensive feasibility studies and an assessment of the risks and potential rewards. Once assessed, the risks and rewards need to be continually monitored to ensure that risks are mitigated and the aims of the investment are being achieved. This oversight is the responsibility of the university council, assisted by management.

Figure 3A details the framework we have used for this review.

Figure 3A

Framework for review of international operations governance framework

|

Framework area |

|---|

|

Setting up international arrangements |

|

|

Overseas campus governance framework |

|

|

Governance and oversight by the Victorian-based university |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

3.4 Overseas-based students

Our review of the university sector found that, in 2015, Victorian universities had 41 136 overseas-based student enrolments, across 16 countries. This generated $202.5 million in revenue. Figure 3B provides an overview of this international engagement, showing the countries these students are located in. Enrolments are predominately based in Asia, although universities have expanded into other areas such as Europe and the Middle East.

Figure 3B

Overseas-based international student enrolments for the university sector in 2015

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office

Students are either:

- enrolled directly at the Victorian-based university, through an overseas campus—for example, RMIT Vietnam is a wholly owned subsidiary of RMIT University

- enrolled at a university based outside of Australia, but can undertake a qualification offered by the Victorian university.

In both cases, assessments and coursework are expected to be completed to the Victorian university's standards before a qualification can be awarded.

The advantage of this approach for Victorian universities is an increased recognition of their brand overseas, a source of additional revenue through royalties from the overseas partner university, and potential future students for the Victorian-based campus.

RMIT University and Victoria University have the largest number of students enrolled in branded courses overseas. RMIT had 12 974 enrolments in 2015, generating $106.2 million in revenue for the university. These enrolments were largely in Vietnam and Singapore. Some universities, such as Deakin University and Federation University Australia, had a very limited number of overseas-based enrolled students.

3.5 Oversight and governance

When setting up these international arrangements, Victorian universities need to ensure that their councils have adequate oversight over the financial and governance arrangements. This enables the council to assure itself that the investment is delivering the expected benefits, that public funds are not being used inappropriately, and that the reputation of the university is not damaged in the event that qualifications are awarded in their name without the student achieving the standards expected.

We have undertaken a review of the oversight arrangements for three universities with overseas-based international students, against the criteria outlined in Figure 3A.

3.5.1 RMIT University

In 2000, RMIT established RMIT University Vietnam LLC (RMIT Vietnam), setting up a campus in Ho Chi Minh City. In 2004, a second campus was set up in Hanoi. RMIT Vietnam is a 100 per cent owned subsidiary of RMIT University. The Vietnam campuses were set up to add value to RMIT's asset base, as well as increasing the university's overseas standing and international presence.

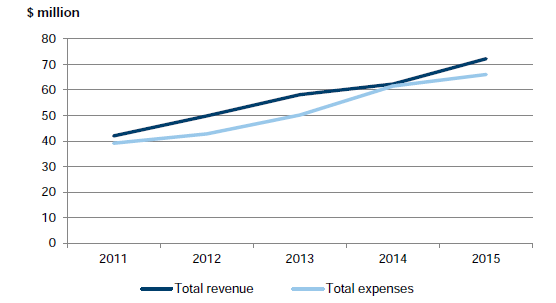

As at 31 December 2015, the Vietnamese campuses had 6 050 student enrolments and employed 562 staff overseas. Combined, the Vietnam campuses generated $4.84 million in net profit for RMIT University and held net assets of $81.2 million. The financial statements of RMIT Vietnam are consolidated into the financial report for RMIT University. Figure 3C shows the revenue and expenses recorded by the university for the overseas campuses over the past five years.

Figure 3C

Revenue and expenditure recognised by RMIT Vietnam for the financial years ending 31 December

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

RMIT University's council retains appropriate oversight of the operations of RMIT Vietnam. As a material subsidiary of the university, the council receives regular reports on the financial aspects of the company as part of its wider financial oversight of RMIT University.

The risks associated with the Vietnam campus are identified and mitigated through RMIT's risk management processes, and RMIT's internal auditors are able to review and scrutinise RMIT Vietnam's operations and processes as part of their work program.

RMIT University has undertaken an assessment of the risks to the university arising from RMIT Vietnam. RMIT's Enterprise Risk Perspectives Report (June 2015) states that 'the reputation and position of the university needs to be underpinned by ongoing and effective professional development for staff; innovation and improvement in curriculum and pedagogy; delivery of high quality teaching facilities and information technology; and efficient supporting administrative and other services we provide for students'. The university clearly demonstrates that it has considered the reputational risk of operating RMIT Vietnam, and these risks are clearly linked to a number of mitigation plans.

The council has not undertaken a recent review to assess whether RMIT Vietnam is achieving its original aims and objectives. However, it has reviewed the ongoing potential of the campus through its recent strategic plan, Ready for Life and Work: RMIT's strategic plan to 2020 (published November 2015). This plan notes that the links RMIT has with Vietnam are important as part of the 'global operations that contribute to RMIT's reputation and financial performance'. It is important that the university's council continually monitors the overseas campuses to make sure that this is being achieved.

3.5.2 Swinburne University of Technology

The Swinburne Sarawak campus in Malaysia was set up by Swinburne University of Technology in 2000. It is a separate legal entity from Swinburne University, and is not controlled by the university. As such, it has its own board, audit committee and other governance operations.

Swinburne has a 25 per cent share in Swinburne Sarawak and employs one member of staff involved in the campus—the chief executive officer. All other staff are employed by the campus directly. Swinburne Sarawak makes royalty payments to Swinburne University, which are recognised in the university's financial statements.

As at 31 December 2015, the Malaysian campus had 4 716 student enrolments and reported income of $3.0 million. Swinburne University's council does not have any direct governance role over Swinburne Sarawak—as a standalone entity, this is the responsibility of the board of the overseas campus. However, two university representatives—the senior vice-chancellor and president, and the vice president, strategy and business innovation—sit on the campus board.

Our review could not determine the level of oversight of Swinburne Sarawak's financial and performance information by Swinburne University management due to a lack of documented evidence. While the university received regular revenue payments—classed as royalties—there was no additional information available to enable management to verify the calculation of royalties paid to the university. Revenue and expenditure transactions relating to the Sarawak campus are managed by the respective Swinburne University operating units and faculties, with no overall oversight by the Swinburne University finance team or management.

Swinburne University's management team does not regularly undertake strategic reviews of the Sarawak campus for council to consider whether or not it is appropriate to continue with its investment. A review was completed in June 2015 with a proceeding financial review of the support provided by Swinburne University to the Sarawak campus completed in February 2006. We noted that some parts of the June 2015 review were based on 2010 financial data, extrapolated over the subsequent four financial years. The irregularity of these strategic reviews means the council is not able to make decisions about its future involvement or to adequately assess its relationship with the campus in a timely manner.

Swinburne Sarawak has its own internal audit and risk management framework. As a result, tailored risks to the campus are not included in the Swinburne University governance processes. While this is appropriate for a standalone entity, Swinburne University needs to identify and mitigate its risks arising from the investment. In particular, the investment opens Swinburne University up to a potential reputational risk that qualifications are awarded in its name without the requisite standards being met by the students.

A risk register relating to Swinburne Sarawak was identified as part of the strategic review completed in June 2015. While the Swinburne Sarawak risk register did provide some commentary and risk ratings in the form of likelihood and consequence level, it did not articulate the mitigating controls or activities in response to the risk, or the business unit responsible for monitoring these risks.

Furthermore, we could not identify how the risks identified by Swinburne Sarawak were considered and included in the Swinburne University main risk register. Swinburne University identifies 'SUT reputation and quality of transnational activity' as a risk, but this lacks specificity and no mitigation controls were identified. We were therefore unable to determine how effectively this risk was being mitigated.

3.5.3 Monash University

Monash University set up the Monash University Malaysia campus (Sunway campus) in 1998. The campus is a joint arrangement with Sunway Group Malaysia and is a standalone entity. The university has a 45 per cent share in the entity. As such, it does not control the entity, and the entity is not consolidated into Monash University's financial report for 31 December.

Monash University recognises costs associated with its provision of staff and materials to the campus, and revenue through royalties paid by Sunway campus. As at 31 December 2015, the Sunway campus had an equivalent full-time student load (EFTSL) of 5 997 and reported a net profit of $260 698. The campus made royalty payments of $13.4 million to Monash University for the 2015 financial year.

In a similar arrangement to the Swinburne Sarawak campus, the Sunway campus has its own board, consisting of 12 members. One board member is Monash University's vice-chancellor and president. Three other members of the board are nominated by the university—the senior vice-president, the chief financial officer, and another staff member of Monash University.

Sunway campus does not have a separate audit committee but does engage an internal auditor who reports to the board.

Our review found that Monash University management undertook regular reviews of the financial revenue and expenditure associated with the Sunway campus. This included quarterly analysis of the information for consideration by the Resources and Finance Committee (RFC), a subcommittee of Monash University's Council.

In addition, Monash's finance team regularly reviews the financial reports of the Sunway campus, with the campus's enrolment, budget and actual financial reports reviewed on a quarterly basis. This enables management to confirm the accuracy of the royalties received.

The central management and council of Monash University have considered the risks relating to the quality of teaching and awarding of qualifications by Sunway campus in the main university risk register, also including this item in the strategic risk register. Mitigation plans have been developed by the university, focusing on quality assurance programs.

As noted in our 2002 report, Monash University set up the Sunway campus joint venture to achieve 10 distinct benefits, including:

- enhanced regional and international profile

- increased income from students

- enhanced academic networking in the region

- enhanced research and development opportunities.

Monash University has not undertaken a recent review to ascertain if these outcomes are being achieved. Monitoring to date has focused on the financial performance and enrolment numbers of the Sunway campus, through the work completed by the RFC.

Recommendations

- That universities with overseas-based students document the identification, mitigation and management of reputational and other risks associated with awarding qualifications overseas.

- That universities with overseas-based students monitor the potential qualitative and quantitative benefits of all overseas activities to ensure that the expected benefits and returns are being realised.

Appendix A. Audited entities

Figure A1 lists the eight universities and their 51 controlled entities which form the university sector at 31 December 2015.

Figure A1

University sector entities at 31 December 2015

Entity |

|---|

|

Deakin University

Federation University

La Trobe University

Monash University

RMIT University

Swinburne University of Technology

The University of Melbourne

Victoria University

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Appendix B. Risk ratings

Figure B1 shows the risk ratings applied to management letter points raised during an audit review.

Figure B1

Risk definitions applied to issues reported in audit management letters

Rating |

Definition |

Management action required |

|---|---|---|

Extreme |

The issue represents:

|

Requires immediate management intervention with a detailed action plan to be implemented within one month. Requires executive management to correct the material misstatement in the financial report as a matter of urgency to avoid a qualified audit opinion. |

High |

The issue represents:

|

Requires prompt management intervention with a detailed action plan implemented within two months. Requires executive management to correct the material misstatement in the financial report to avoid a qualified audit opinion. |

Medium |

The issue represents:

|

Requires management intervention with a detailed action plan implemented within three to six months. |

Low |

The issue represents:

|

Requires management intervention with a detailed action plan implemented within six to 12 months |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Appendix C. Financial sustainability indicators

Financial sustainability risk indicators

Figure C1 shows the indicators used in assessing the financial sustainability risks of universities in Part 2 of this report. These indicators should be considered collectively and are more useful when assessed over time as part of a trend analysis.

Figure C1

Financial sustainability risk indicators

Indicator |

Formula |

Description |

|---|---|---|

Net result (%) |

Net result / Total revenue |

A positive result indicates a surplus, and the larger the percentage, the stronger the result. A negative result indicates a deficit. Operating deficits cannot be sustained in the long term. Net result and total revenue is obtained from the comprehensive operating statement. |

Liquidity (ratio) |

Current assets / Current liabilities |

This measures the ability to pay existing liabilities in the next 12 months. A ratio of one or more means there are more cash and liquid assets than short-term liabilities. |

Capital replacement (ratio) |

Cash outflows for property, plant and equipment / Depreciation |

Comparison of the rate of spending on infrastructure with its depreciation. Ratios higher than 1:1 indicate that spending is faster than the depreciating rate. This is a long-term indicator, as capital expenditure can be deferred in the short term if there are insufficient funds available from operations and borrowing is not an option. Cash outflows for infrastructure are taken from the cash flow statement. Depreciation is taken from the comprehensive operating statement. |

Internal financing (%) |

Net operating cash flow / Net capital expenditure |

This measures the ability of an entity to finance capital works from generated cash flow. The higher the percentage, the greater the ability for the entity to finance capital works from its own funds. Net operating cash flows and net capital expenditure are obtained from the cash flow statement. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The analysis of financial sustainability risk in this report reflects on the position of each university.

Financial sustainability risk assessment criteria

The financial sustainability risk of each university has been assessed using the criteria outlined in Figure C2.

Figure C2 Financial sustainability risk indicators—risk assessment criteria

Risk |

Underlying result |

Liquidity |

Capital replacement |

Internal-financing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

High |

Negative 10% or less |

Less than 0.75 |

More than 1.0 |

Less than 10% |

Insufficient revenue is being generated to fund operations and asset renewal. |

Immediate sustainability issues with insufficient current assets to cover liabilities. |

Spending on capital works has not kept pace with consumption of assets. |

Limited cash generated from operations to fund new assets and asset renewal. |

|

Medium |

Negative 10%–0% |

0.75–1.0 |

1.0–1.5 |

10–35% |

A risk of long‑term run down to cash reserves and inability to fund asset renewals. |

Need for caution with cash flow, as issues could arise with meeting obligations as they fall due. |

May indicate spending on asset renewal is insufficient. |

May not be generating sufficient cash from operations to fund new assets. |

|

Low |

More than 0% |

More than 1.0 |

More than 1.5 |

More than 35% |

Generating surpluses consistently. |

No immediate issues with repaying short‑term liabilities as they fall due. |

Low risk of insufficient spending on asset renewal. |

Generating enough cash from operations to fund new assets. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Changes to prior year reports

The financial sustainability risk indicators used in this report have changed slightly from prior years. The changes are detailed below:

- The indicators have been calculated from the information in the published financial statements for the entity, with no adjustments made to these figures, other than audit adjustments to reflect issues raised in the Deakin University and the University of Melbourne modified audit opinions.

- The net result indicator has replaced the previous underlying result indicator.

- The internal financing indicator has replaced the previous self-financing indicator.

Financial sustainability risk analysis results

The financial sustainability risk for each consolidated university institute, for each financial year ending 31 December 2011 through to 2015 are shown in Figures C3 to C10.

The following trend analysis has been applied to the results for each university:

↓ |

Deteriorating trend |

↑ |

Improving trend |

■ |

No substantial trend identified |

Figure C3

Financial sustainability risk indicator results for

Deakin University for the year ending 31 December

Net result |

Liquidity |

Capital replacement |

Internal financing |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

2011 |

11.51% |

1.76 |

2.70 |

115% |

2012 |

13.31% |

1.39 |

3.94 |

99% |

2013 |

8.94% |

1.16 |

2.79 |

101% |

2014 |

7.04% |

1.26 |

1.05 |

215% |

2015 |

7.16% |

1.28 |

1.42 |

165% |

Trend |

↓ |

↓ |

↓ |

↑ |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure C4

Financial sustainability risk indicator results for

Federation University Australia for the year ending 31 December

Net result |

Liquidity |

Capital replacement |

Internal financing |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

2011 |

17.95% |

5.22 |

1.36 |

396% |

2012 |

22.36% |

5.33 |

3.36 |

223% |

2013 |

1.83% |

5.02 |

2.37 |

58% |

2014 |

1.02% |

2.64 |

0.46 |

369% |

2015 |

2.33% |

3.18 |

0.50 |

206% |

Trend |

↓ |

↓ |

↓ |

↓ |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure C5

Financial sustainability risk indicator results for

La Trobe University for the year ending 31 December

Net result |

Liquidity |

Capital replacement |

Internal financing |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

2011 |

13.72% |

1.75 |

3.40 |

108% |

2012 |

5.77% |

1.16 |

4.15 |

63% |

2013 |

7.19% |

0.99 |

2.67 |

95% |

2014 |

2.70% |

1.02 |

1.52 |

159% |

2015 |

8.85% |

0.99 |

1.63 |

111% |

Trend |

↓ |

↓ |

↓ |

■ |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure C6

Financial sustainability risk indicator results for

Monash University for the year ending 31 December

Net result |

Liquidity |

Capital replacement |

Internal financing |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

2011 |

6.05% |

0.42 |

3.14 |

81% |

2012 |

5.43% |

0.46 |

2.11 |

127% |

2013 |

3.33% |

0.45 |

1.89 |

106% |

2014 |

10.73% |

0.42 |

2.61 |

110% |

2015 |

7.98% |

0.47 |

3.85 |

82% |

Trend |

↑ |

■ |

↑ |

■ |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure C7

Financial sustainability risk indicator results for

RMIT University for the year ending 31 December

Net result |

Liquidity |

Capital replacement |

Internal financing |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

2011 |

6.04% |

0.55 |

3.33 |

54% |

2012 |

5.32% |

0.64 |

2.60 |

86% |

2013 |

6.62% |

0.66 |

1.17 |

195% |

2014 |

6.78% |

0.59 |

2.35 |

99% |

2015 |

5.81% |

0.59 |

3.35 |

69% |

Trend |

↑ |

■ |

↑ |

■ |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure C8

Financial sustainability risk indicator results for

Swinburne University of Technology for the year ending 31 December

Net result |

Liquidity |

Capital replacement |

Internal financing |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

2011 |

7.74% |

1.67 |

4.65 |

65% |

2012 |

3.80% |

1.40 |

1.15 |

202% |

2013 |

9.52% |

1.35 |

3.30 |

105% |

2014 |

2.38% |

1.27 |

1.25 |

172% |

2015 |

2.71% |

1.28 |

0.48 |

393% |

Trend |

↓ |

↓ |

↓ |

■ |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure C9

Financial sustainability risk indicator results for

The University of Melbourne for the year ending 31 December

Net result |

Liquidity |

Capital replacement |

Internal financing |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

2011 |

5.41% |

0.96 |

1.50 |

147% |

2012 |

6.63% |

0.80 |

2.41 |

98% |

2013 |

4.84% |

0.80 |

1.75 |

119% |

2014 |

7.59% |

0.81 |

1.46 |

95% |

2015 |

6.33% |

1.07 |

1.30 |

170% |

Trend |

■ |

↑ |

↓ |

■ |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure C10

Financial sustainability risk indicator results for

Victoria University for the year ending 31 December

Net result |

Liquidity |

Capital replacement |

Internal financing |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

2011 |

1.87% |

1.13 |

2.04 |

86% |

2012 |

-1.42% |

0.83 |

1.97 |

88% |

2013 |

1.33% |

1.36 |

0.88 |

81% |

2014 |

-3.64% |

1.27 |

1.47 |

279% |

2015 |

-2.81% |

1.26 |

0.74 |

151% |

Trend |

↓ |

↑ |

↓ |

↓ |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Appendix D. Glossary

Accountability

Responsibility on public entities to achieve their objectives, with regard to reliability of financial reporting, effectiveness and efficiency of operations, compliance with applicable laws, and reporting to interested parties.

Asset

A resource controlled by an entity from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the entity.

Audit Act 1994

The Audit Act 1994 establishes the operating powers and responsibilities of the Auditor-General. This includes the operations of his office—the Victorian Auditor‑General's Office (VAGO)—as well as the nature and scope of audits that VAGO carries out.

Auditor's opinion

Written expression within a specified framework indicating the auditor's overall conclusion on the financial (and performance) reports based on audit evidence obtained.

Capital expenditure

Amount capitalised to the balance sheet for contributions by a public sector entity to major assets owned by the entity, including expenditure on:

- capital renewal of existing assets that returns the service potential or the life of these assets

- expenditure on new assets, including buildings, infrastructure, plant and equipment.

Clear audit opinion