Managing and Reporting on the Performance and Cost of Capital Projects

Overview

This report was initially tabled on 4 May but has been reissued because information in the original report was incorrect and needed to be updated as a matter of public record. More specifically, the original report mistakenly identified a Royal Children’s Hospital ICT investment project as being over approved time and over budget. See the transmittal letter on page iii of the report for more detail. It should be noted that the removal of the Royal Children’s Hospital ICT investment project had only a minor impact on the aggregated numbers and did not materially affect the report’s findings.

The limited transparency on the status of government's major capital projects means Parliament and the public cannot easily access information on the progress of each project against cost and time line targets.

While it is encouraging that agencies are using the Department of Treasury & Finance's (DTF) Investment Lifecycle and High Value/High Risk Guidelines (lifecycle guidelines), our more detailed examination of 15 projects showed gaps or weaknesses in around half the documentation reviewed. This is a significant concern because complying with the guidelines can help mitigate the risks that projects will be late, over budget or not adequately define and deliver on their intended benefits.

The report's recommendations highlight the need for:

- DTF and the Department of Premier & Cabinet to advise government how best to track the progress of government capital projects and make this information available to Parliament and the community

- DTF to periodically review agencies’ performance in applying the lifecycle guidelines

- individual agencies to appropriately assess and improve compliance with the lifecycle guidelines.

Transmittal letter

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER June 2016

PP No 154, Session 2014-16

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my revised Managing and Reporting on the Performance and Cost of Capital Projects report, to be tabled in lieu of the original report tabled on 4 May 2016.

Your Clerks advised that this revised report should be tabled after I became aware that information in the original report was incorrect and needed to be updated as a matter of public record. More specifically, the original report mistakenly identified a Royal Children’s Hospital ICT investment project as being over approved time and over budget.

The removal of reference to the Royal Children’s Hospital ICT investment project being over approved time and over budget in this revised report has resulted in this project being deleted from Figure 2O on page 29 and Figure 2R on page 32 as well as showing that the project is on time and budget in Figure C1 on page 54. The removal also had flow-on impacts to the aggregated numbers referred to in the Audit summary paragraph five on page xi, Figure 2A on pages 15 and 16, Figure 2D on page 18, Figure 2N (and the associated text) on page 29, the text on pages 29 and 30 associated with Figure 2O, as well as Figures 2P and 2Q (and the text associated with them) on page 31.

It should be noted that the removal of the Royal Children’s Hospital ICT investment project had only a minor impact on the aggregated numbers and did not materially affect the report’s findings.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

8 June 2016

Auditor-General's comments

|

Dr Peter Frost Acting Auditor-General |

Audit team Ray Winn and Michael Herbert—Engagement Leaders Rocco Rottura—Team Leader Hayley Svenson—Team member Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Tony Brown |

The state is investing billions of dollars in its capital works program to improve and build hospitals, schools, roads, public transport and other infrastructure to support the delivery of a wide range of important services.

Parliament and the community rightly expect that publicly funded capital investments are planned and managed in a way that delivers the predicted benefits on time and within allocated budgets. The scale and complexity of capital projects in the State Budget mean that successful delivery represents a major challenge for public sector agencies. Unexpected cost blowouts can significantly impact the state's finances and affect the government's ability to deliver its wider policy agenda. Unforeseen delays also mean the community has to wait longer for the promised benefits, and unreliable benefit estimates risk distorting government's decision-making.

Previous VAGO reports on major infrastructure have identified significant weaknesses and recommended improvements in the way projects are developed and delivered, and in how outcomes are measured and reported.

This audit builds on those previous audits of individual major projects. It is a broader examination of projects with a total estimated investment of $10 million or more, and which are listed in the 2015–16 State Capital Program Budget Paper. Specifically, I examined how effectively agencies manage the time, cost, scope, development and delivery of major capital projects.

Despite the significant capital expenditure, I found that obtaining current information on capital projects across the public sector is a complex and challenging exercise and there is limited public reporting. This lack of transparency makes it difficult to determine whether investments have enhanced government services and whether public resources have been spent in an efficient, effective and economical way. Some agencies found providing the information requested for this audit onerous and resource intensive. This raises concern about the level of scrutiny they apply to their capital projects as part of their governance processes.

The information provided shows that a high proportion of agencies purport to prepare capital project documentation in line with the Department of Treasury & Finance's (DTF) Investment Lifecycle and High Value/High Risk Guidelines (lifecycle guidelines). However, my more detailed examination of 15 projects showed gaps or weaknesses in around half of the documentation reviewed. This is a significant concern because complying with the lifecycle guidelines can help mitigate the risks that projects will be late or over budget or will not adequately define and deliver their intended benefits.

My recommendations accordingly target the need for agencies to implement a documented and consistent approach to verify that they have complied with DTF's lifecycle guidelines. They also address the need for DTF and the Department of Premier & Cabinet to advise government on how best to track the progress of capital projects and make this information available to Parliament and the community. By providing this information, the government can improve project transparency and accountability, and allow the public to compare projects using standardised metrics across agencies. Further, it will make it harder for underperforming projects to go unnoticed and easier for government to focus effort on projects where it is most needed.

In future years, I intend to use the information obtained in this audit to identify selected capital projects for more focused audits.

Finally, I wish to thank staff at the agencies for their assistance and cooperation during this audit.

Dr Peter Frost Acting Auditor-General

May 2016

Audit Summary

Background

The effective planning and delivery of major capital projects is critical to governments achieving their policy objectives. If delivered well, infrastructure enhances services to the public and improves productivity. Poor management diminishes the benefits of these projects, potentially delays delivery and creates additional costs for taxpayers.

In 2015–16, the total estimated investment in new and previously announced projects in the State Capital Program Budget is approximately $52 billion, comprising $28 billion in existing and $24 billion in new investments.

Previous VAGO reports on major infrastructure investments have identified significant weaknesses and recommended improvements to the way projects are developed and delivered, and in how outcomes are measured and reported.

The Department of Treasury & Finance (DTF) and the Department of Premier & Cabinet (DPC) advise government on infrastructure investment and delivery.

DTF also has oversight of the Investment Lifecycle and High Value/High Risk Guidelines (lifecycle guidelines) that guide project development and delivery.

DPC in consultation with DTF is responsible for setting up Projects Victoria, a new entity, that is expected to oversee the delivery of all major capital projects, research and develop appropriate delivery models, review and improve capability in project development and delivery, and publicly report on their performance.

Although guidance and support is currently provided centrally, the government's devolved model of responsibility means that individual agencies are responsible for developing and successfully delivering infrastructure projects.

Objectives and scope of this audit

The objective of the audit is to assess how effectively agencies manage the time, cost, scope, development and delivery of major capital projects by examining whether they have:

- developed business cases that provide a sound basis for the government to decide if, and in what form, investments should proceed

- developed sound procurement processes

- monitored and managed projects' progress and risks during delivery

- demonstrated that completed projects have achieved the intended outputs and outcomes.

The audit examined self-attested information from agencies and included a limited examination of key project documentation for a sample of 15 projects, to verify its completeness and help focus future audits of major infrastructure projects. Specifically, the audit assessed whether the documents included content as required by the lifecycle guidelines and how well this material addressed the requirements.

The audit scope includes Victorian public sector agencies responsible for managing capital projects with a total estimated investment of $10 million or more, as listed in the 2015–16 State Capital Program Budget Paper.

Conclusions

The limited transparency on the status of government's major capital projects means Parliament and the public cannot easily access information on the progress of each project against cost and time targets.

The difficulty many agencies had in providing basic information also raises concerns about the current level of scrutiny they apply to these projects as part of their governance processes. Had agencies been properly monitoring their investments, the information sought for this audit would have been readily available.

While it is encouraging that agencies are using DTF's lifecycle guidelines, our more detailed examination of 15 projects showed gaps or weaknesses in around half of the documentation reviewed. This is a significant concern because complying with the guidelines can help mitigate the risks that projects will be late or over budget or will not adequately deliver their intended benefits.

The governance and ongoing monitoring of a small number of projects were affected by the absence of key project documentation because it had been subject to the Cabinet-in-Confidence processes of a previous government. In these cases, agencies mistakenly assumed they no longer had access to critical documents, such as business cases. However, mechanisms do exist which enable agencies to retain or obtain assess to Cabinet-in-Confidence material where it can be justified that it relates to ongoing business. However, this is not comprehensively understood across all public sector agencies.

Findings

Self-attested survey and provision of documents

The 30 audited agencies identified a total of 251 projects within the 2015–16 Budget Papers as being above the $10 million threshold for this audit. These projects have a combined total estimated investment of $35.7 billion.

The self-reported and attested information obtained through the survey indicates that a high proportion of agencies are preparing documentation in line with DTF's lifecycle guidelines,including establishing appropriate governance and management structures.

Of the 251 projects, 47 projects were at the initiation stage and two were postponed while in the initiation stage, meaning they would not yet have business cases. Of the remaining 202 projects, well over 90 per cent had the relevant information within business cases or supporting plans. However, only 65 of the 197 projects with a business case (33 per cent) reported reviewing the business case after approval. Further, benefits management plans were reported as being reviewed for only 24 of the 35 projects where there were changes in the project scope, costs or time lines after the business case was approved.

Similarly agencies reported that of the 155 projects that had undertaken procurement, over 85 per cent had prepared a procurement plan and tender evaluation report. However, despite a requirement that probity plans are prepared for all projects over $10 million, 38 projects (25 per cent) had not done so. Without a probity plan, it is unclear how agencies manage probity risks including tender communications, late tenders, tender security, confidentiality and intellectual property.

Agencies indicated that only 12 of 41 completed and terminated projects (29 per cent) had undertaken post-implementation reviews. For the vast majority of the remaining projects, agencies advised they planned to do so.

Despite agencies asserting that a high proportion of projects have capital project documentation in line with the lifecycle guidelines, a significant number of projects are, or are expected to be, over budget and/or late. Of these:

- eight of 215 projects (4 per cent) are over budget by more than 5 per cent or $47.6 million in total

- 70 of 212 projects (33 per cent) are either completed or forecast to be late.

Limited examination of 15 projects

Agencies are clearly using the lifecycle guideline templates to structure their project documentation. While this is encouraging, in about half of the documentation reviewed there were significant gaps or weaknesses in the content used to populate these templates.

Some agencies fell short of the standards required in describing the benefits, documenting the solution, analysing the options, proving deliverability and identifying the probity risks. This raises concerns about the reliability of the self‑reported and attested information submitted in response to our survey.

The absence of documentation for three of the 15 selected projects is a significant issue, as it is impeding effective project governance by agencies and means we have been unable to assess if these projects addressed key elements in the investment lifecycle guidance. For one of these projects, a business case for the full program of works is under development and expected to be submitted to government in mid-2016. For the other two projects, the agency could not provide critical documentation (e.g. full business cases), because these had been put in secure storage and not returned under the current Cabinet conventions covering a change of government. Our follow-up inquiries to DPC have been unsuccessful in locating and accessing these documents.

Recommendations

- That the Department of Treasury & Finance and the Department of Premier & Cabinet advise government on how best to establish a public reporting mechanism that provides relevant project status information on capital projects costing $10 million or more, planned and actual costs, time lines, governance arrangements, and the extent to which benefits are realised.

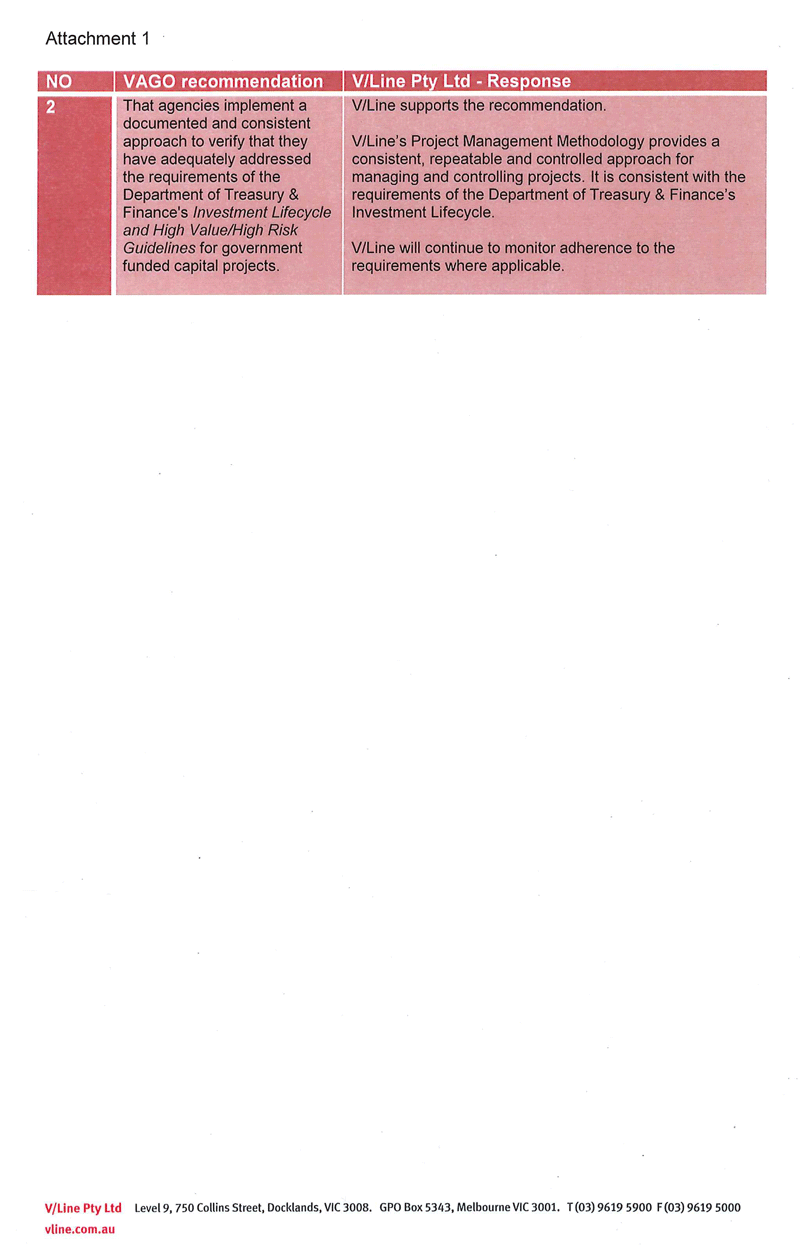

- That agencies implement a documented and consistent approach to verify that they have adequately addressed the requirements of the Department of Treasury & Finance's Investment Lifecycle and High Value/High Risk Guidelines for government-funded capital projects.

- That the Department of Treasury & Finance periodically reviews agencies' performance in applying the Investment Lifecycle and High Value/High Risk Guidelines for projects costing $10 million or more and provides feedback to agencies on areas requiring improvement.

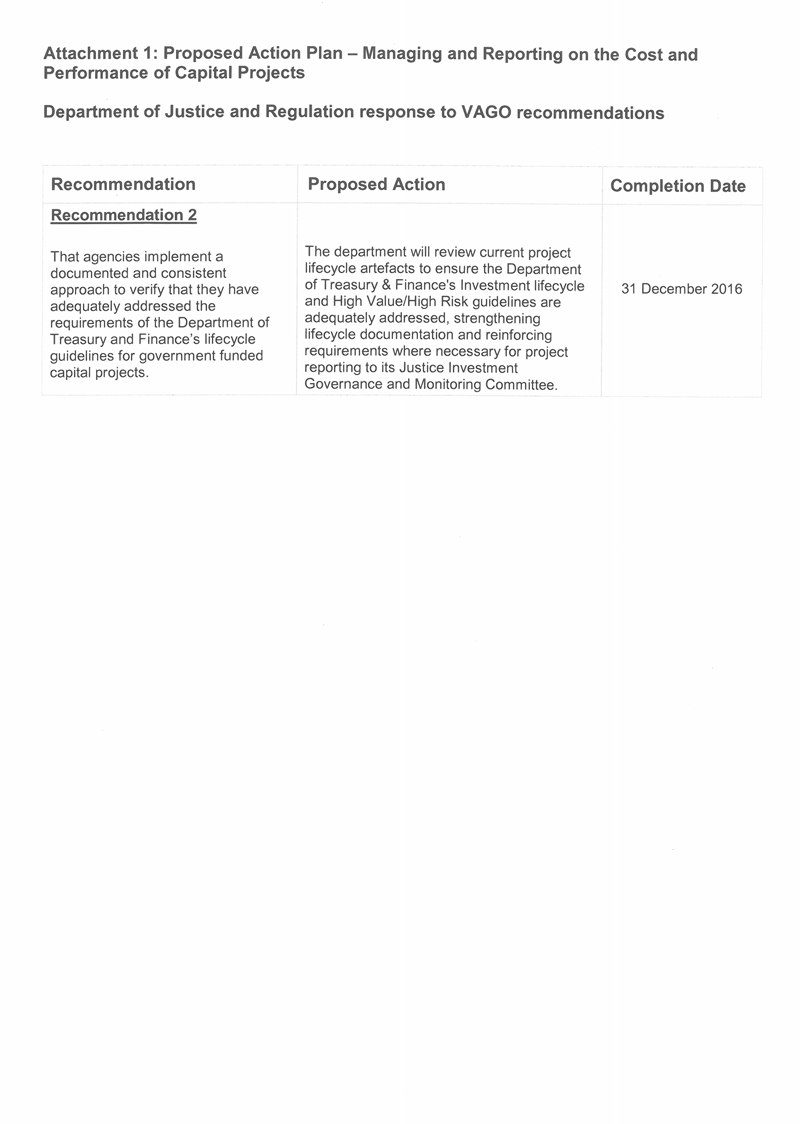

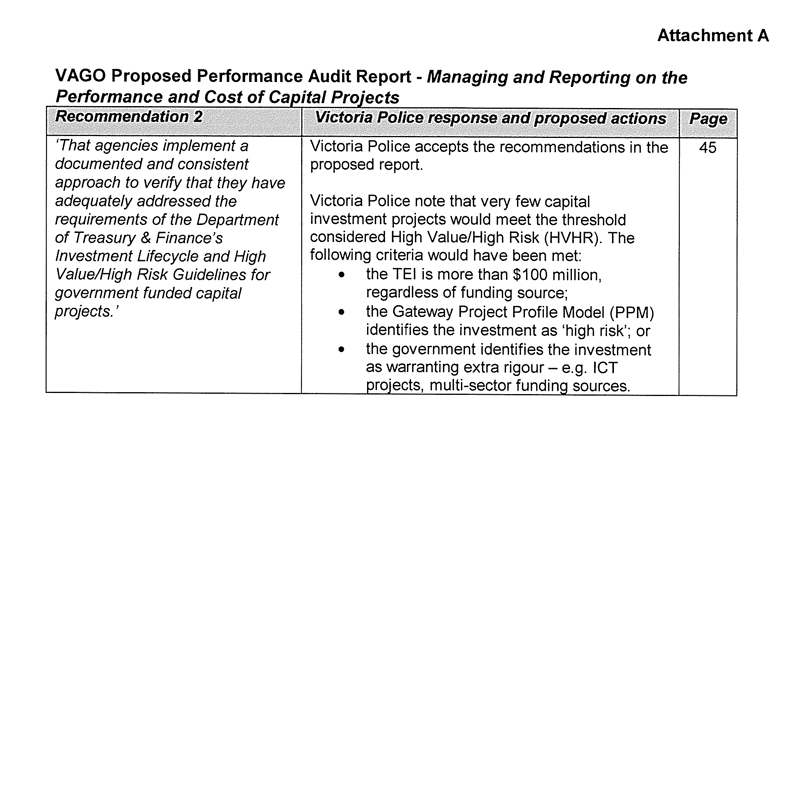

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with the surveyed agencies listed in Appendix A and the Department of Premier & Cabinet, the Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board, VicTrack and RMIT University throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report, or part of this report, to those agencies and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix D.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

The quality of life and economic success of any community is heavily influenced by the quality of its water supply, sewerage systems, roads, public transport, education facilities, health facilities, communications systems, communal facilities and recreational infrastructure.

The effective planning and delivery of major capital projects is critical to governments achieving their policy objectives. If delivered well, infrastructure enhances services to the public and improves productivity. Poor management diminishes the benefits of these projects, potentially delays delivery and creates additional costs for taxpayers.

1.2 State Capital Program

The state is investing billions of dollars in its capital works program to build and improve hospitals, schools, roads, public transport and other infrastructure. For 2015−16, the total estimated investment (TEI) in new projects and previously announced projects still under construction in the State Capital Program Budget is approximately $52 billion. This includes $28 billion in existing investments and $24 billion in new investments.

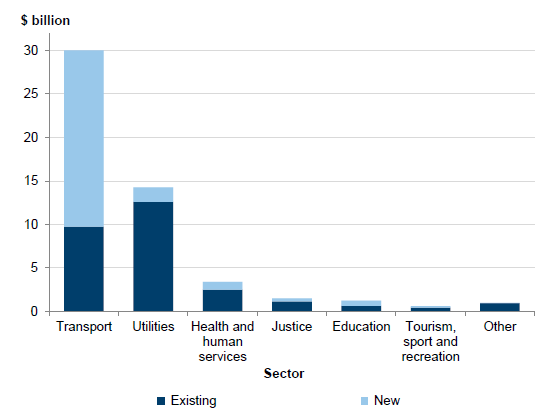

Figure 1A shows that the transport sector—comprising roads, rail and ports—accounts for the largest proportion of expenditure, with a TEI of $30 billion, making up 58 per cent of the State Capital Program.

The utilities sector—which includes water infrastructure—is second in terms of expenditure, with $14.3 billion in projects. The balance of the state's capital program is invested as follows:

- $3.4 billion in health and human services, including hospitals, medical research centres, health facilities, residential housing for people with disabilities and public and community housing

- $1.5 billion in justice, including courts, police stations, correctional facilities, fire stations and other emergency management stations and facilities

- $0.7 billion in education, including preschool, primary and secondary schools, university and technical and further education (TAFE) institutes

- $0.6 billion in tourism, sport and recreation, including recreational areas, mixed‑use facilities, convention facilities, cultural institutions (such as museums), entertainment facilities (such as music venues and theatres) and sporting facilities, art precincts and galleries, and tourist attractions

- $1.0 billion in other miscellaneous projects.

Figure 1A

Existing and new estimated investment by sector

Source: VAGO based on the State Capital Program, Budget Paper No. 4, 2015–16.

Details including the TEI of new and previously announced major infrastructure investments, by sector, are outlined in Figure 1B. The largest Budget commitments include $9–$11 billion to deliver the Melbourne Metro Rail Project and $5–$6 billion allocated for the removal of 50 level crossings. These two projects comprise almost one-third of the State Capital Program Budget.

Figure 1B

Major infrastructure investments, by sector

|

Transport |

|---|

|

|

Utilities |

|

|

Education |

|

|

Health and human services |

|

|

Justice |

|

|

Tourism, sport and recreation |

|

Source: VAGO from the State Capital Program, Budget Paper No. 4, 2015–16, and the Victorian Budget 15/16 for Families.

1.3 Victoria's approach to managing investments

This capital expenditure represents a major investment and financial risk for the state and requires effective planning and management to deliver projects on time and within budget while realising the intended benefits.

Previous VAGO reports on major infrastructure investments have identified significant weaknesses and recommended improvements to the way projects are developed and delivered, and in how outcomes are measured and reported.

The less-than-satisfactory performance of certain projects was also highlighted in the former government's April 2011 Victorian Economic and Financial Statement which referred to 'a range of capital projects beset by inadequate management and very significant cost overrun'. The aggregate impact of these cost overruns was estimated to be in around $2 billion.

1.3.1 Guidance and assurance

In response, the government introduced the High Value High Risk (HVHR) process to provide greater assurance that major projects will deliver the intended benefits within scheduled time lines and approved budgets. Managed through the Department of Treasury & Finance (DTF), the process requires greater centralised oversight of projects that meet one or all of the following criteria:

- a TEI of $100 million or more

- identified as high risk and/or highly complex during planning processes

- considered by government to warrant greater oversight and assurance.

The HVHR process requires the Treasurer's approval of project documentation at key stages in a project's lifecycle.

The HVHR process builds on DTF's existing Investment Lifecycle and High Value/High Risk Guidelines (lifecycle guidelines) and gateway reviews, which involve reviews at the main stages of a project.

The lifecycle guidelines apply to all government departments, corporations, authorities and other bodies falling under the Financial Management Act 1994.

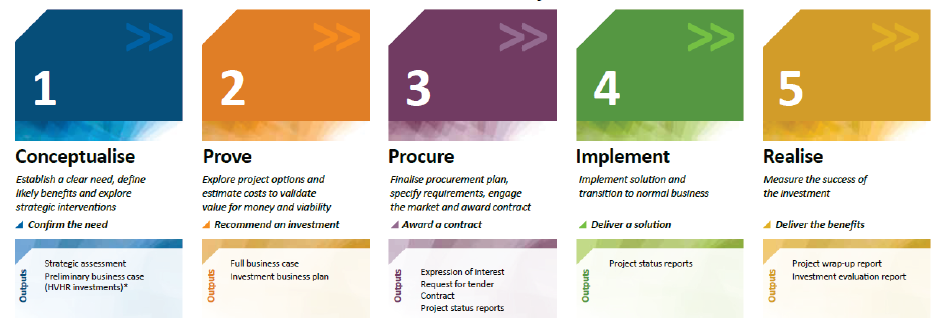

The lifecycle guidelines support the development of business cases which are mandatory for capital investments with a TEI of $10 million or more and provide guidance to agencies across five identified stages of the investment lifecycle, by helping them to:

- conceptualise an investment by establishing the need and defining the benefits

- prove a solution by assessing the costs, benefits and risks of likely options

- procure the investment by awarding a contract that best delivers the solution and provides value for money

- implement the solution to realise benefits and manage costs and risks

- realise the benefits and measure the success of the investment.

Figure 1C shows the investment lifecycle framework.

Figure 1C

Investment lifecycle framework

Source: Department of Treasury & Finance, Investment Lifecycle and High Value High Risk Guidelines—Overview.

1.3.2 Capital projects reporting in the Victorian Government

DTF, in consultation with the Department of Premier & Cabinet (DPC), provides information to government on the progress of capital projects on a quarterly basis that:

- examines the progress and performance of departments, public hospitals and TAFE institutes in managing the risks associated with implementing projects

- includes commentary focused on major projects and the most material issues given the magnitude of the state's capital program

- summarises the mitigation strategies implemented and decisions already taken to address identified key risks and issues

- highlights risks and issues with major projects and, where appropriate, proposes recommendations for government consideration.

However, for the public, knowing the status, progress and outcomes of capital projects is currently difficult as there is limited information made publicly available. The public must search various information sources and even then is only likely to gain a limited understanding of progress against cost and time targets.

The use of digital dashboards in other jurisdictions

A digital dashboard is a reporting tool that presents key metrics in an easy to interpret visual interface. It provides a bird's-eye view of key up-to-date information on projects and initiatives.

The transparency provided by a digital dashboard can reveal emerging trends in project expenditure and make it harder for underperforming projects to go unnoticed, and easier for the government to focus efforts where they are most needed.

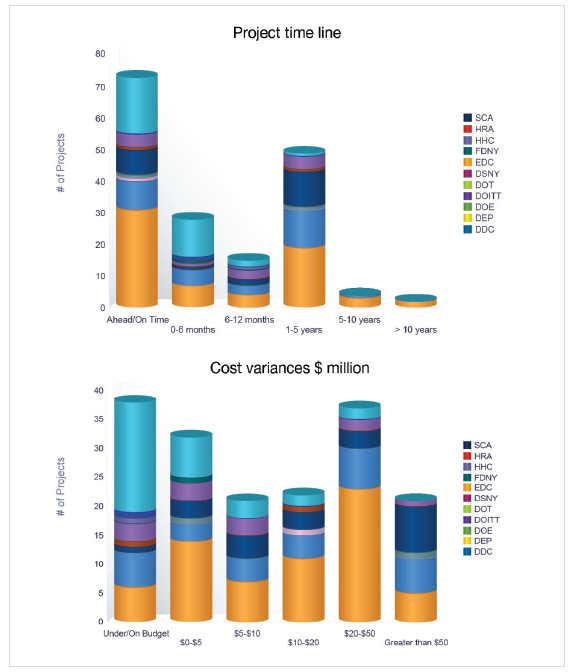

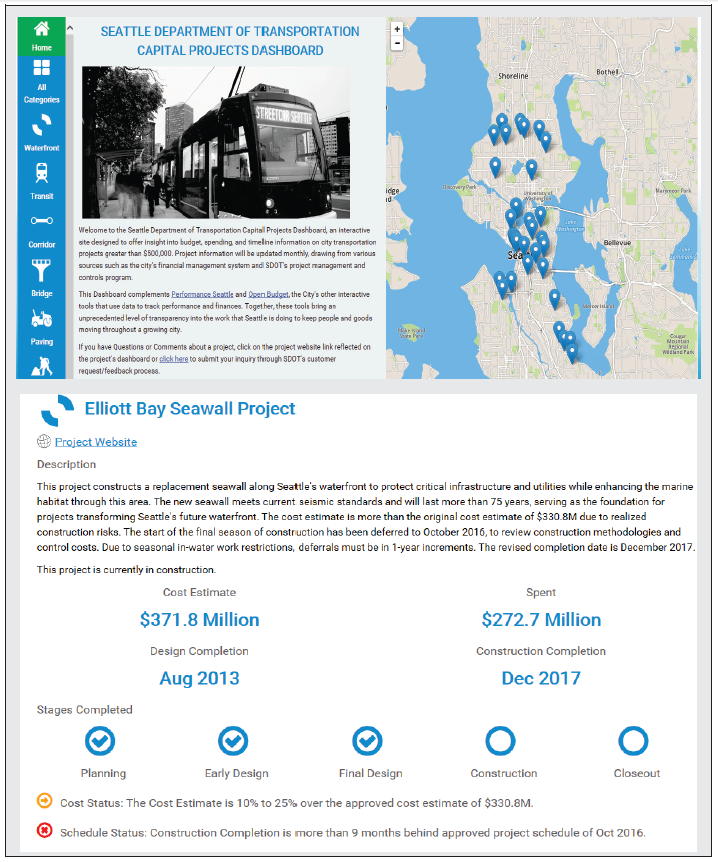

Governments in other jurisdictions have acknowledged the need to provide greater visibility of their capital projects and activities. For example, the Capital Projects Dashboard used by New York City's Office of the Mayor, shown in Figure 1D, provides a view into the city's most costly infrastructure and information technology projects. The dashboard displays an overview of all capital projects managed by the city with budgets of $25 million or more, and includes a summary status of projects by schedule—the difference between the current anticipated completion date and the previously estimated completion date—and by cost variance.

Figure 1D

New York City's Office of the Mayor, Capital Projects Dashboard

Source: http://www.nyc.gov/html/ops/capital/html/dashboard/project_schedule.shtml, as at 22 January 2016.

Similarly the Seattle Department of Transportation maintains the Capital Projects Dashboard—an interactive site designed to provide key project status information on transportation projects greater than $500 000. Figure 1E shows the Capital Projects Dashboard and an example of the information available for a project.

Figure 1E

Seattle Department of Transportation Capital Projects Dashboard

Source: https://capitalprojects.seattle.gov/#/, as at 22 January 2016.

Similar dashboards have also been developed for information and communications technology (ICT) projects in other jurisdictions, including the Queensland Government dashboard which monitors the progress of major ICT projects. VAGO's 2015 report Digital Dashboard: Status Review of ICT Projects and Initiatives applied this approach to ICT projects.

By providing this information, governments aim to improve project transparency and accountability, allow the public to compare projects using standardised metrics across agencies, and maintain and track project information over time. This can also inform government policy on the budgeting and management of capital projects.

1.4 Institutional arrangements and responsibilities

As indicated earlier:

- DTF and DPC advise the government on infrastructure investment and delivery

- DTF has also developed guidance for agencies to develop, procure, deliver and evaluate capital projects.

Although guidance is provided centrally, the government's devolved model of responsibility means that individual agencies are responsible for developing and successfully delivering infrastructure projects.

A range of public sector agencies routinely deliver major projects in Victoria. These agencies, and their typical projects, include:

- Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR) through the following portfolio agencies:

- Public Transport Victoria—rail infrastructure and trains and trams

- Port of Melbourne Corporation—port infrastructure

- VicRoads—road building and upgrades

- Melbourne Metro Rail Authority—metropolitan rail project

- Level Crossing Removal Authority—removal of level crossing

- other—a variety of capital projects may also be delivered in agriculture, events and tourism and creative sectors

- Department of Justice & Regulation—prisons and police stations

- Court Services Victoria—courts and tribunals

- Department of Health & Human Services—new and upgraded hospitals and public housing

- Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning and the Water Corporations—water infrastructure

- Department of Education & Training—schools.

Infrastructure Victoria, a new statutory authority, was established in September 2015 to provide independent and expert advice about Victoria's current and future infrastructure needs and priorities to support improved social, economic and environmental outcomes for the state. A key function of the new organisation is to develop a 30-year infrastructure strategy that identifies the state's infrastructure needs.

Projects Victoria, a new entity, when fully established, is expected to oversee the delivery of major capital projects, to research and develop appropriate delivery models and to review and improve capability in project development and delivery. It will also publicly report on the performance of all the projects it oversees.

1.5 Recent reviews of major infrastructure projects

1.5.1 Parliamentary inquiries

The Economy and Infrastructure Committee's 2015 First report into infrastructure projects examined five key infrastructure projects. It found that three of the projects that were currently underway—the Level Crossing Removal Program, the Western Distributor and the Melbourne Metro Rail Project—were still in the early stages, so business cases and detailed plans had not been finalised.

The committee concluded that the completion and release of the business cases and plans, including details on managing the disruption caused by these projects, the finalisation of funding arrangements and more precise cost estimates, was a key priority.

A 2012 Public Accounts and Estimates Committee Inquiry into Effective Decision‑Making for the Successful Delivery of Significant Infrastructure Projects examined six major infrastructure projects to identify lessons to inform decision-making and implementation of future infrastructure projects. The inquiry found that:

- poorly defined governance structures with unclear roles and responsibilities have hampered project management

- inadequate planning has led to significant delays, cost increases and failures to achieve original objectives

- overly ambitious and poorly scoped projects have unnecessarily heightened project complexity and risk.

1.5.2 Previous performance audits

Over the past six years,VAGO has tabled several audit reports that have considered the management, delivery and oversight of capital projects including:

- Management of Major Rail Projects, June 2010

- Construction of Police Stations and Courthouses, February 2011

- Management of Major Road Projects, June 2011

- Melbourne Markets Redevelopment, March 2012

- Managing Major Projects, October 2012

- Operating Water Infrastructure Using Public Private Partnerships, August 2013

- Impact of Increased Scrutiny of High Value High Risk Projects, June 2014

- Digital Dashboard: Status Review of ICT Projects and Initiatives, April 2015

- Operational Effectiveness of the myki Ticketing System, June 2015

- Applying the High Value High Risk Process to Unsolicited Proposals, August 2015

- East West Link Project, December 2015.

These VAGO reports have identified significant time and cost overruns in some projects, and recommended improvements to the way projects are developed and procured and to how outcomes are measured and reported. The audits have also identified poor business case development, including gaps in the information underpinning decisions, and the inadequate consideration of available procurement options as recurring shortcomings in government projects.

1.6 Audit objective and scope

The objective of the audit is to assess how effectively agencies manage the time, cost, scope, development and delivery of major capital projects by examining whether they have:

- developed business cases that provide a sound basis for the government to decide if, and in what form, investments should proceed

- developed sound procurement processes

- monitored and managed projects' progress and risks during delivery

- demonstrated that completed projects have achieved the intended outputs and outcomes.

The audit examined self-attested information from agencies and included a limited examination of key project documentation collected for a sample of 15 projects to verify its completeness and help focus future audits of major infrastructure projects. Specifically, the audit assessed whether the documents included content as required by the lifecycle guidelines and how well this material addressed the requirements.

The audit scope included Victorian public sector agencies responsible for managing capital projects with a TEI of $10 million or more, as listed in the 2015–16 State Capital Program Budget Paper.

This also included projects with a value of $10 million or more within programs that bring together multiple projects. Smaller capitals projects—less than $10 million—were excluded even if the program's TEI presented in the Budget Papers exceeded the $10 million threshold for the audit.

Construction underway to remove the level crossing at North Road in Ormond. Photograph courtesy of the Level Crossing Removal Authority.

1.7 Audit method and cost

In total, 33 agencies were asked to complete a survey and provide documentation detailing time, cost, development, delivery, governance, and performance information for each of their relevant capital projects.

Of these, two agencies attested that they did not have any projects that met our audit scope—RMIT University and the Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board—and one—VicTrack—advised that although they are listed as the agency responsible for projects, these are being managed by other agencies.

The list of surveyed agencies is included in Appendix A. In addition, DPC was included given its role in advising the government on infrastructure investment and delivery.

Agencies were requested to provide an attestation that the information provided in their response was accurate and complete, to the best of their knowledge. Our summary of the self-attested information provided by agencies is set out in Part 2 of this report.

During the course of the audit, information submitted by agencies was in some instances clearly inaccurate.

A limited examination of supporting documentation for 15 projects, based on the size, sector and performance of projects, was undertaken to verify the documentation's completeness. Appendix B lists the capital projects selected for further review.

We have used DTF's lifecycle guidelines as a better practice guide and view the core components and requirements within the guidelines as essential and scalable across major projects.

The audit was conducted in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The cost of the audit was $495 000.

1.8 Structure of the report

This report has two further parts:

- Part 2 examines the survey responses provided by agencies relating to planning documents, governance structures, project management, procurement, post‑implementation reviews and project costs and time lines

- Part 3 examines the documentation collected for a selection of projects to verify its completeness and help focus future audits of major infrastructure projects.

2 Analysis of capital projects survey

At a glance

Background

The Department of Treasury & Finance's (DTF) Investment Lifecycle and High Value/High Risk Guidelines (lifecycle guidelines) provide guidance to agencies on managing projects. This part examines agencies' survey responses relating to planning, governance, project management, procurement, post-implementation reviews and project costs and time lines.

Conclusion

There is limited transparency on the status of major capital projects across the Victorian public sector, which means that Parliament and the public are restricted in their ability to access information on the progress of each project against cost and time targets.

The self-reported and attested information provided by agencies shows that a high proportion purport to prepare capital project documentation in line with the lifecycle guidelines and to have established appropriate governance and management structures.

Findings

- The vast majority of agencies reported compliance with DTF's lifecycle guidelines.

- Agencies identified a total of 251 projects within 2015–16 State Budget on 251 projects, with a total estimated investments (TEI) of $10 million or more, with a combined TEI of $35.7 billion.

- In total, 4 per cent of projects have already exceeded, or are forecast to exceed, their budgets by more than 5 per cent.

- Around one-third of projects are already late or are forecast to finish after their planned completion dates.

Recommendation

- That Department of Treasury & Finance and the Department of Premier & Cabinet advise government on how best to establish a public reporting mechanism that provides relevant project status information on capital projects costing $10 million or more, planned and actual costs, time lines, governance arrangements, and the extent to which benefits are realised.

2.1 Introduction

This part examines agencies' responses to the survey for capital projects over $10 million. After providing an overview in section 2.3, this part examines:

- planning documents, including business cases, procurement strategies and risk management, engagement and benefit management plans (section 2.4)

- procurement documents, including procurement and probity plans and tender evaluation reports (section 2.5)

- post-implementation reviews (section 2.6)

- governance and management structures (section 2.7)

- performance against budget and time lines (section 2.8).

2.2 Conclusion

There is limited transparency on the status of major capital projects across the Victorian public sector which means that Parliament and the public are restricted in their ability to access information on progress against cost and time targets.

The self-reported and attested information obtained through our survey indicates that a high proportion of agencies are preparing documentation in line with the lifecycle guidelines, including establishing appropriate governance and management structures. However, a significant number of projects are over budget and/or are late.

Obtaining current information on capital projects across the public sector is a complex and challenging exercise for many agencies. They found providing the information requested as part of this audit onerous and resource intensive due to:

- decentralised management and functions which require coordination across numerous units within the agency

- machinery-of-government changes

- some information, including business cases, being held by another agency.

Had agencies been applying regular high-level scrutiny to their investments, this information would have been readily available.

While the Department of Treasury & Finance (DTF) collects information on capital projects for presentation to government on a quarterly basis, there is an absence of detailed public reporting on a project-by-project basis. The transparency and oversight benefits of establishing a capital projects dashboard are significant.

2.3 Overview of results

2.3.1 Reported capital projects

The audited agencies identified a total of 251 projects within the 2015–16 Budget Papers as being above the $10 million threshold for this audit. These projects have a combined total estimated investment (TEI) of $35.7 billion, accounting for 69 per cent of the TEI for all capital projects in the State Budget. The remaining 31 per cent comprises:

- $2.3 billion worth of projects having a TEI of less than $10 million

- an estimated $14 billion in programs that bring together multiple smaller projects with individual TEIs of less than $10 million.

Figure 2A shows the number of projects and their reported TEIs by agency.

Five agencies—the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR), the Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS), Melbourne Water Corporation, Public Transport Victoria and VicRoads—account for around 69 per cent of projects, and 86 per cent of the combined TEI of $35.7 billion.

Figure 2A

Number of projects and their value by agency

Agency |

Number of projects |

Budget |

|---|---|---|

Barwon Water Corporation |

2 |

50.3 |

Bendigo Kangan Institute |

1 |

12.2 |

Central Gippsland Region Water Corporation |

1 |

40.4 |

Country Fire Authority |

3 |

36.3 |

Chisholm Institute |

1 |

70.5 |

City West Water Corporation |

2 |

310.9 |

Coliban Water Corporation |

3 |

63.1 |

Court Services Victoria |

2 |

79.0 |

Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources |

13 |

17 731.3(a) |

Department of Environment Land Water & Planning |

2 |

29.4 |

Department of Education & Training |

18 |

265.7 |

Department of Health & Human Services |

39 |

3 461.3 |

Department of Justice & Regulation |

16 |

680.5 |

Department of Treasury & Finance |

1 |

31.5 |

Goulburn Murray Rural Water Corporation |

2 |

932.8 |

Grampians Wimmera Mallee Water Corporation |

1 |

688.0 |

Lower Murray Urban & Rural Water Corporation |

1 |

119.8 |

Melbourne Water Corporation |

54 |

1 072.1(b) |

Places Victoria |

2 |

34.0 |

Port of Melbourne Corporation |

2 |

935.9 |

Public Transport Victoria |

38 |

4 282.3 |

Southern Metropolitan Cemeteries Trust |

1 |

53.4 |

South East Water Corporation |

4 |

275.6 |

South Gippsland Region Water Corporation |

1 |

20.0 |

Transport Accident Commission |

1 |

45.8 |

V/Line |

1 |

14.8 |

VicRoads |

28 |

4 051.3 |

Victoria Police |

4 |

54.6 |

Western Water Corporation |

2 |

63.7 |

Yarra Valley Water Corporation |

5 |

238.6 |

Total |

251 |

35 745.1 |

(a) This includes the Melbourne Metro Rail Project and the Level Crossing Removal Program which have a TEI range of $9–$11 billion and $5–$6 billion respectively and relates to funding for the full term of the projects. We have used the higher range of the estimate.

(b) The budgeted cost does not include 36 projects which are in the early planning stage and do not yet have a budget estimate.

Source: VAGO survey of 30 agencies, 2015.

2.3.2 Top 10 projects in terms of costs

Figure 2B shows the top 10 projects ranked by budgeted TEI where:

- transport projects account for 88.5 per cent of the top 10

- the top 10 projects account for 62.8 per cent of the TEI of all 251 reported projects.

Figure 2B

Top 10 capital projects by cost

Agency |

Project name |

Original cost ($ million) |

Forecast/ actual cost ($ million) |

Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

DEDJTR |

Melbourne Metro Rail Project |

9 000–11 000 |

9 000–11 000 |

Initiated |

Level Crossing Removal Program |

5 000–6 000 |

5 000–6 000 |

In delivery |

|

Port of Melbourne Corporation |

Port Capacity Project |

920.6 |

802.2 |

In delivery |

Goulburn Murray Rural Water Corporation |

Connections Program |

918.0 |

918.0 |

In delivery |

Public Transport Victoria |

Interim Rolling Stock |

817.1 |

782.7 |

Completed |

Grampians Wimmera Mallee Water Corporation |

Wimmera Mallee Pipeline Project |

688.0 |

657.5 |

Completed |

VicRoads |

Western Highway Duplication |

662.3 |

662.3 |

In delivery |

DHHS |

Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre |

501.5 |

501.5 |

In delivery |

Bendigo Hospital redevelopment |

473.0 |

129.5 |

In delivery |

|

Public Transport Victoria |

Tram Rolling Stock |

439.8 |

383.3 |

In delivery |

Source: VAGO survey of 30 agencies, 2015.

2.3.3 Capital project phases

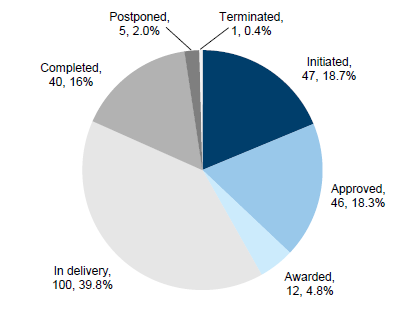

Figure 2C shows that of the 251 capital projects reported:

- 47 (18.7 per cent) were at the initiation phase—detailed planning including research and project design/or development had commenced

- 46 (18.3 per cent) were at the approved phase—a business case had been approved

- 12 (4.8 per cent) were at the awarded phase—tendering process for the construction phase of the project had commenced and/or had been completed

- 100 (39.8 per cent) were in delivery—construction had commenced

- 40 (16 per cent) had been completed—project works were completed

- 5 (2 per cent) had been postponed—project was put on temporary hold

- 1 (0.4 per cent) had been terminated—project was terminated before completion and total expenditure has or will be written off.

Figure 2C

Number of capital projects by phase

Source: VAGO survey of 30 agencies, 2015.

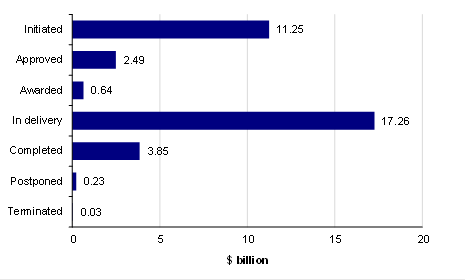

Figure 2D shows the cost of projects in each phase, with approximately half of the projects—in terms of cost ($17.2 billion)—being in delivery.

Figure 2D

Total budgeted project cost by phase, $ billion

Source: VAGO survey of 30 agencies, 2015.

Agencies reported that more than $256.7 million of capital projects were either terminated or postponed comprising:

- The Department of Justice & Regulation's (DJR) Infringement Management and Enforcement Services project, worth $24.9 million, was terminated in March2015, following significant difficulties and delays with the system build since 2007.

- Public Transport Victoria's Comeng Trains Life Extension project, worth $75 million, has been postponed pending the resolution of a safety issue significant for defining the project scope.

- DJR's Corrections System Expansion project, worth $65.1 million, was postponed. No reasons were provided—DJR stated that consideration through Cabinet was currently underway.

- DEDJTR's Port-Rail Shuttle–Metropolitan Intermodal System, worth $58 million, was postponed because it may not be the only way of achieving improved rail outcomes at the Port of Melbourne. The current government has decided to seek rail proposals as part of the Port of Melbourne lease.

- The Western Water Corporation's Surbiton Park winter storage project, worth $17.7 million, was postponed until further investigation of other projects that may provide greater cost efficiencies.

- Places Victoria's Harbour Esplanade Redevelopment Stage 2 Docklands project, worth $16 million, was postponed due to a revised project scope.

2.4 Planning documents

The lifecycle guidelines require all investment proposals over $10 million seeking Budget funding to submit a full business case which includes a:

- procurement strategy

- risk management plan

- stakeholder engagement and communication plan

- benefits management plan.

The level of technical detail required will vary depending on the size, scale and complexity of the investment.

Of the 251 projects, 47 were at the initiation stage and two were postponed while in the initiation stage, meaning they would not yet have business cases. Of the remaining 202 projects, well over 90 per cent had the relevant information within business cases or supporting plans, as shown in Figure 2E.

Figure 2E

Project planning documents

Document |

Document in place |

No document in place |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Number of projects |

Percentage of all projects |

Number of projects |

Percentage of all projects |

|

Business case |

197 |

97.5 |

5 |

2.5 |

Procurement strategy |

195 |

96.5 |

7 |

3.5 |

Risk management plan |

201 |

99.5 |

1 |

0.5 |

Stakeholder engagement plan |

191 |

94.6 |

11 |

5.4 |

Benefits management plan |

192 |

95.0 |

10 |

5.0 |

Source: VAGO survey of 30 agencies, 2015.

Planning documents were prepared for all projects except the Level Crossing Removal Program. The government committed to remove 50 specific level crossings and the overall business case is currently being prepared for completion in mid-2016.

The works to remove level crossings are proceeding, with the first crossings having individual, business cases or project proposals covering, among other things, the key technical elements and deliverability information required in a business case.

However, proceeding with this program without an overall business case is not recommended practice and raises the risks around the timely and efficient delivery of the intended benefits. Precise cost and benefit estimates for the program have not yet been prepared and validated.

DTF and the Department of Premier & Cabinet (DPC) advice to government, in June 2015, noted the challenge in delivering the entire Level Crossing Removal Program within the $5–$6 billion commitment. Given the significant expenditure and risks in delivering such a large program, it is critical that a comprehensive program business case is completed and that it adequately considers the costs, benefits and risks together with an options analysis to assure government that the preferred approach represents good value.

2.4.1 Business cases

The lifecycle guidelines require a full business case to set out the problem, intended benefits, strategic options and recommended solution. The level of technical detail required will vary depending on the size, scale and complexity of the project.

Figure 2F shows that agencies attested that a business case was developed for 197 of the 202 projects (around 97.5 per cent) and that for 184 (93 per cent) business cases included all the required elements.

Figure 2F

Development of business cases

Agency response |

Business case developed |

Contains all required elements |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Number of projects |

Percentage of all projects |

Number of projects |

Percentage of all projects |

|

Yes |

197 |

97.5 |

184 |

93 |

No |

5 |

2.5 |

13 |

7 |

Total |

202 |

100 |

197 |

100 |

Source: VAGO survey of 30 agencies, 2015.

One problem agencies encountered was difficulty in accessing businesses cases. This affected 66 of the 197 projects for which business cases had been prepared. Agencies advised VAGO to obtain these Cabinet-in-Confidence documents from DPC because:

- 49 had been surrendered to DPC on the change of government and agencies no longer had access to these documents

- for the remaining 17, agencies were unsure whether the versions held were the same as the final documents presented to government.

DPC quickly identified and provided 30 of these documents. However, locating the remaining 36 business cases proved very difficult and after an extensive search, DPC:

- provided a further 21 cases where agencies had not initially provided sufficient information to locate the documents—for example, where the project was part of the business case for a wider initiative

- identified four projects as not being covered by standalone business cases because they had been identified within a high-level plan—for example, the 'Tram procurement project' was only presented as part of the 'Victorian Transport Plan'

- confirmed that for two projects, the relevant departments (DHHS and DJR) held this documentation and it had not been submitted to Cabinet or a Cabinet committee

- could not find nine business cases that had been recorded as part of a single submission for a former government's budget review process.

The difficulties DPC encountered in providing access to 36 of the 66 business cases were due mainly to agencies providing insufficient or inaccurate information about the project title or whether it was part of the business case for a wider program. Agencies did not use the index information they would have provided in surrendering these documents to DPC—this is a records management failure they need to address.

DPC could not find nine of these business cases that were recorded as being submitted to Cabinet. This is DPC's responsibility, but the department has advised that changes in its process for the filing and auditing of cabinet and committee records mean this issue is now unlikely to be repeated.

Five of the 202 projects, with budgeted costs of up to $6 billion, did not have or could not provide a business case, as shown in Figure 2G.

Figure 2G

Projects without a business case

Agency |

Project |

Budgeted cost |

Reason for no business case |

|---|---|---|---|

DEDJTR |

Level Crossing Removal Program |

5 000–6 000 |

VicRoads and DEDJTR have prepared business cases or project proposals for four packages of works comprising 19 crossings in advance of a business case for all 50 level crossings. |

DEDJTR |

Parkville Gardens |

43.5 |

DEDJTR advised that this is a legacy project from the 20 per cent social housing mandate as part of the delivery of the Commonwealth Games Village, entered into in December 2003, and that it was covered in a former department's Commonwealth Games Budget submission in 2003.However, DEDJTR could not find this submission in its records. |

DHHS |

Simonds Stadium redevelopment—Stage 4 |

75.0 |

The project was originally an output funding submission that subsequently became a capital‑funded project. As a result, a full business case was not prepared. |

DJR |

Corrections systems expansion—emergency beds program |

19.5 |

In early 2014, a spike in prisoner numbers created a pressing need for additional prison beds. This urgent need for 300 emergency beds across the prison system was supported and funded by government. Given the time-sensitive nature of this project, DJR decided to forgo the development of a comprehensive business case. |

Victoria Police |

Victoria Police Mounted Branch Relocation |

11.9 |

Victoria Police advised that the business case was a DPC-led initiative because the Victoria Police Mounted Branch was required to be relocated so the site could be redeveloped by Arts Victoria. This is not a valid reason for not developing a business case. |

Source: VAGO survey of 30 agencies, 2015.

Review of business cases

The lifecycle guidelines indicate that business cases should be regularly reviewed by agencies or project managers to reflect significant changes to the project environment and provide an up-to-date case for the project throughout its life. However, Figure 2H shows that only 65 of business cases (33 per cent) were reviewed after approval.

Figure 2H

Review of business cases

Agency response |

Business case reviewed |

|

|---|---|---|

Number of projects |

Percentage of projects |

|

Yes |

65 |

33 |

No |

132 |

67 |

Total |

197 |

100 |

Source: VAGO survey of 30 agencies, 2015.

This lack of review after approval risks the business case becoming a static document used for funding but not updated and used for driving and managing the intended project outcomes.

2.4.2 Procurement strategies

Choosing the right procurement model is a significant decision requiring in-depth analysis and consideration. Getting it wrong could have a serious impact on the project delivery and realisation of benefits. The business case should include a procurement strategy analysing options and making recommendations on the preferred procurement method to inform the project approval and funding decision.

Agency responses indicate that a procurement strategy was developed for 195 of the 202 capital projects reported (96.5 per cent). The seven projects shown in Figure 2I, with a cumulative cost of $187 million, did not have such a strategy.

Figure 2I

Projects without a procurement strategy

Agency |

Project |

Budgeted cost ($ million) |

Reason for no procurement strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

DEDJTR |

Parkville Gardens |

43.5 |

See comments in Figure 2G. |

DJR |

Expanding Community Correctional Services |

25.9 |

Procurement conducted through the shared service provider within DTF that undertakes property searches, leasing arrangements and fit-out services on behalf of government departments. This is not a competitive process. DJR advised that, therefore, no procurement strategy was required. |

DJR |

Fines Reform Information and Communications Technology (ICT) Project |

15.0 |

This project was merged into another project for which a procurement strategy was developed. |

DJR |

Mobile Camera Replacement Program |

17.1 |

DJR advised that a procurement strategy will be developed upon completion of the proof of concept stage of the project. |

VicRoads |

Geelong-Bacchus Marsh Road |

27.0 |

VicRoads advised that these three projects are currently at an early stage of development, with procurement strategies currently being developed. |

Goulburn Valley Highway—Molesworth to Yea |

18.5 |

||

Hume Freeway—Continuous Wire Rope Safety Barrier |

40.0 |

Source: VAGO survey of 30 agencies, 2015.

2.4.3 Risk management plans

A risk management plan—usually included in the business case—identifies, assesses, prioritises and describes how to mitigate project risks.

Agency responses indicate that a risk management plan was developed for 201 of the 202 capital projects reported (99.5 per cent). The Corrections system expansion—emergency beds program, with a budgeted value of $19.5 million, did not have a risk management plan.

2.4.4 Stakeholder engagement and communication plans

A stakeholder engagement plan identifies, assesses and prioritises key stakeholder groups to ensure that they are effectively engaged throughout the project.

Agency responses indicate that a stakeholder engagement and communication plan was developed for 191 of the 202 capital projects reported (94.6 per cent). The 11 projects shown in Figure 2J, with a cumulative cost of $479.4 million, did not have stakeholder engagement and communication plans.

Figure 2J

Projects without a stakeholder engagement and communication plan

Agency |

Project |

Budgeted cost ($ million) |

Reason for no stakeholder engagement and communication plan |

|---|---|---|---|

DELWP |

More effective support for strategic fuel management |

16.8 |

A specific stakeholder engagement and communication plan was not developed. However, internal and external stakeholders were regularly consulted to ensure effective design and interoperability with other agencies. |

DJR |

Corrections system expansion—emergency beds program |

19.5 |

See comments in Figure 2G. However, DJR advised various stakeholder engagement and communications activities did occur. |

DJR

|

Barwon High Security Unit |

35.0 |

Stakeholder engagement and management forms part of the project governance forums. |

DJR |

Critical infrastructure and services—Barwon Waste Water Treatment Plant |

17.0 |

Stakeholder engagement and management forms part of the project governance forums. |

DJR |

Critical infrastructure and services—Melbourne Assessment Prison Reception |

11.8 |

Stakeholder engagement and management forms part of the project governance forums. |

DJR |

Karreenga Annexe—Marngoneet |

79.6 |

Stakeholder engagement and management forms part of the project governance forums. |

DJR |

Middleton Annexe—Loddon prison |

79.0 |

Stakeholder engagement and management forms part of the project governance forums. |

DJR

|

State Coronial Services Centre |

113.0 |

Stakeholder engagement and management forms part of the project governance forums. |

DJR |

Women's prison expansion strategy—Dame Phyllis Frost Centre Mental Health Unit |

40.7 |

Stakeholder engagement and management forms part of the project governance forums. |

VicRoads |

Geelong-Bacchus Marsh Road |

27.0 |

VicRoads advised that these two projects are currently at an early stage of development, with stakeholder engagement and communication plans currently being developed. |

Hume Freeway—Continuous Wire Rope Safety Barrier |

40.0 |

Source: VAGO survey of 30 agencies, 2015.

2.4.5 Benefits management plan

Investments in capital projects are intended to provide benefits to the state and community. Projects are only valuable if they deliver these benefits. A benefits management plan sets out how benefits defined in the business case are going to be monitored, evaluated and reported.

Responses show that benefits management plans were in place for 192 of the 202 projects reported (95 per cent). However, as highlighted in Figure 2K, 10 projects (5 per cent), cumulatively valued at around $288.5 million, did not have a benefits management plan.

Further, benefits management plans were reported as being reviewed for only 24 of the 35 projects where there were changes in the project scope, costs or time lines after the business case was approved. It is important that benefits management plans are live, up-to-date documents that reflect changes in project scope.

Figure 2K

Projects without benefits management plan

Agency |

Project |

Budgeted cost ($ million) |

Reason for no benefits management plan |

|---|---|---|---|

Barwon Water |

Black Rock Water Reclamation Plant Inlet Hydraulic Capacity Upgrade |

14.3 |

Barwon Water considers that the cost benefit in the business case analysis serves the same purpose as a benefits management plan. This is not consistent with the lifecycle guidelines which require a separately documented benefits management plan. |

Coliban Water |

Rochester to Echuca Water Reclamation Plant |

10.0 |

Benefits management plan not required when business case prepared in late 1990s. |

DEDJTR |

Parkville Gardens |

43.5 |

See comments in Figure 2G. |

DHHS |

Westmeadows Redevelopment—144 units/sites |

71.8 |

No reason provided. |

DJR |

Corrections system expansion—emergency beds program |

19.5 |

See comments in Figure 2G. |

DJR |

Hopkins Correctional Centre Expansion Project |

45.9 |

No reason provided. |

Victoria Police |

Victoria Police Mounted Branch Relocation |

11.9 |

Victoria Police advised that it did not develop a business case including a benefits management plan because the relocation was driven by a DPC-led initiative to expand the Victorian College of the Arts to the South Melbourne site. This is not a valid reason for not developing a business case and benefits management plan. |

Yarra Valley Water |

Aurora Waste to Energy Facility |

27.1 |

Yarra Valley Water advised that a benefits management plan will be developed for the project as part of the transition from construction to operation. |

Donvale Backlog Sewerage —Package C |

22.5 |

Yarra Valley Water advised that a benefits management plan was not prepared because benefit tracking is embedded within standard business processes. |

|

Wallan Sewerage Treatment Plant Upgrade |

22.0 |

Yarra Valley Water advised that a benefits management plan was not developed. that the projects' key benefits will be tracked through operational performance tracking indicators e.g. volume of sewerage treated, quality of effluent produced, volume of water recycled etc. |

Source: VAGO survey of 30 agencies, 2015.

2.5 Procurement processes

It is important that procurement for large capital projects is well conducted given the significant expenditure involved and the impact it can have on delivering government programs and services and on the achievement of the intended outcomes.

Agencies are required to develop a procurement plan after funding has been approved. This is a key product of the procurement stage of the investment lifecycle, providing guidance about the expression of interest, tendering and contract negotiation phases and how to effectively manage probity and procurement risks.

A probity plan is required for all major projects exceeding $10 million and also for other projects assessed as complex or high risk.

Upon completion of the procurement activities, the results of the tender evaluation process must be comprehensively documented in a final report.

Figure 2L shows which documents were in place for the 155 projects that undertook procurement.

Figure 2L

Procurement documents

Document |

Document in place |

No document in place |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Number of projects |

Percentage of all projects |

Number of projects |

Percentage of all projects |

|

Procurement plan |

131 |

85 |

24 |

15 |

Probity plan |

117 |

75 |

38 |

25 |

Tender evaluation report |

140 |

90 |

15 |

10 |

Source: VAGO survey of 30 agencies, 2015.

Agencies reported the following:

- A procurement plan had been prepared for 131 of the 155 projects (around 85 per cent)

- A probity plan had been prepared for 117 of the 155 projects (around 75 per cent). This means that 38 projects, valued at $1.64 billion, did not have a probity plan as required under the lifecycle guidelines. Without a probity plan, it is unclear how agencies manage probity risks including managing tender communications, late tenders, tender security and confidentiality, intellectual property, etc.

- A tender evaluation report had been prepared for 140 of the 155 projects (90 per cent). Fifteen projects had not prepared such a report, and this is a significant omission because there is no documented explanation of the reason for selecting a preferred tenderer.

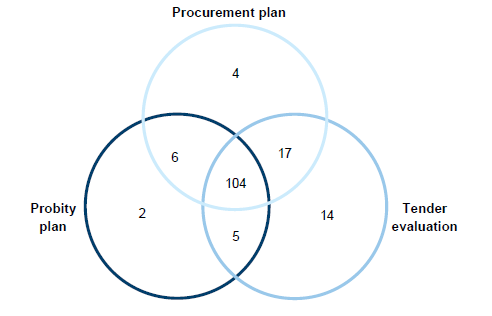

From a project perspective, Figure 2M shows that of the 155 procured projects:

- 104, or two-thirds, had all the required documentation

- 28 had two of the three required documents

- 20 reported having one of the three required documents.

The following three projects, with a budgeted cost of $83 million, reported having no procurement plan, probity plan or tender evaluation report:

- Cardinia Road Station, managed by Public Transport Victoria.

- Corrections system expansion—emergency beds program, managed by DJR.DJR received ministerial approval for the procurement of emergency beds in response to the urgent demand for additional prison beds across the prison system.

- Expanding Community Correctional Services, managed by DJR.

Figure 2M

Project procurement documentation

Source: VAGO survey of 30 agencies, 2015.

2.6 Post-implementation reviews

Realising the benefits of an investment is the important final stage of an investment's lifecycle. The key is to develop a benefits management plan at the start, to make it possible to track, report, validate and evaluate the delivery of the expected benefits. It also involves conducting a post-implementation review to find out whether the expected benefits of the investment have been realised, and what lessons can be learned from the project for both current and future projects.

Agencies indicated that 12 of 41 completed and terminated projects (29 per cent) had undertaken post-implementation reviews. Of the remaining 29 completed projects:

- 28 had yet to commence the post-implementation review but agencies advised that they planned to do so

- one project, Middleton Annexe—Loddon Prison, managed by DJR, with an estimated cost of $79 million, did not do a post-implementation review.

2.7 Governance and management structures

Project governance and management structures should be in place throughout the life of a project. They set the framework for transparency, provide assurance about the way decisions are made and clarify roles and responsibilities.

Survey responses indicate that all 202 reported capital projects had established a defined governance structure. This excludes 47 projects at the initiation stage and two projects that were postponed in the initiation stage, as they do not have approved business cases setting out governance and management structures.

A robust project management methodology is required to guide the project to deliver its intended investment benefits.

A commonly cited reason for project failures is poor project management. Therefore, applying a formalised project management methodology can help to clarify goals, identify resources needed, ensure accountability for results and performance, and foster a focus on the intended benefits.

Of the capital projects report, 198 (98 per cent) were managed using recognised project management methodologies or the agencies' own project management methodologies. Of the 198 projects:

- 4 per cent used Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBoK)

- 3 per cent used PRINCE2

- 85 per cent used their own in-house methodology

- 8 per cent used other recognised methodologies.

Given the large proportion of agencies using their own project management methodologies, future audits of capital projects will examine the adequacy of these methodologies.

2.8 Performance against budget and time lines

Cost and time variances are important because they defer the realisation of intended project benefits and may require government to divert funds from other activities. If large enough, they can undermine the completion of projects and lead to their cancellation.

2.8.1 Actual versus budgeted cost

The agencies reported costs for 215 of the 251 projects. No budget or actual figures were provided for 36 projects because they had only recently been initiated. The total reported cost for the 215 projects was $35.7 billion, which is around $0.74 billion less than the approved budget estimates.

While this represents an overall budget saving, the reality is masked by the 55 projects which are, or are expected to be, completed $1.2 billion under budget.

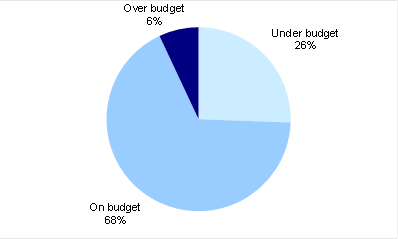

Figure 2N shows the percentage of projects on, over or under their approved budget.

Figure 2N

Percentage of projects on, over or under budget

Source: VAGO survey of 30 agencies, 2015.

Eight projects are or are expected to be over their approved budget by over 5 per cent. As shown in Figure 2O, these projects had a total cost of $379.9 million, meaning they are or are expected to be $47.6 million (14.3 per cent) over the total budgeted cost of $332.2 million. Agencies identified that the main factors contributing to cost overruns were design and/or scope changes.

Figure 2O

Projects over approved budget

Agency |

Project |

Phase |

Budget ($ million) |

Actual ($ million) |

Per cent over budget |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Melbourne Water Corporation |

Dandenong Creek Wetland |

Completed |

19.7 |

35.4 |

80.1 |

Country Fire Authority |

Dandenong Fire Station |

Completed |

10.7 |

12.9 |

20.2 |

Public Transport Victoria |

Lynbrook Station |

Completed |

28.6 |

33.0 |

15.4 |

City West Water Corporation |

The Arrow Program |

In delivery |

106.0 |

119.6 |

12.8 |

Coliban Water Corporation |

Rural System Reconfiguration—Harcourt |

In delivery |

39.5 |

42.6 |

7.8 |

South East Water Corporation |

Frankston Head Office Construction |

In delivery |

91.6 |

98.1 |

7.1 |

VicRoads |

High Street Road Improvement Project |

In delivery |

16.2 |

17.2 |

6.2 |

Melbourne Water Corporation |

Asset Management Information System—AMIS |

Completed |

19.9 |

21.0 |

5.6 |

Total |

332.2 |

379.8 |

14.3 |

||

Source: VAGO survey of 30 agencies, 2015.

Of the projects that are over budget:

- Four (50 per cent) are over budget by more than 10 per cent, or $35.9 million across all projects.

- Four (50 per cent) are over budget by less than 10 per cent, or $11.7 million across all projects.

In addition to the eight projects in Figure 2O, there were a further six projects more than 5 per cent over their original budget. These projects, with a combined original budget value of $937.7 million, have received additional funding of $270.7 million following approved project scope changes. These projects include:

- Geelong Hospital major upgrade—original budget $93.3 million, revised budget $118.2 million

- Barwon Health—original budget $28.1 million, revised budget $33.1 million

- Box Hill hospital redevelopment—original budget $407.5 million, revised budget $447.5 million

- Bayside Rail Improvement project—original budget $100 million, revised budget $115 million

- Regional Fast Rail Passenger Information Display—original budget $8.8 million, revised budget $10.2 million

- Melbourne Market Relocation Project—original budget $300 million, revised budget $484.4 million.

For some projects the scope changes and associated budget revisions raise questions about whether the basis for the original investment decisions was sound. For example, the Melbourne Market Relocation Project had an original approved budget of $300 million for the purchase of a suitable site and construction of the trading floor and associated infrastructure. No funding was provided for warehousing or other site development. This budget was later revised in April 2009 and June 2011 to $484.4 million due to:

- the addition of warehousing, which was originally to be financed by a private company, with costs recovered through rental or sale to market tenants and users

- $116 million in additional costs for land purchases and construction

- $65 million for site preparation and project management costs which had been omitted from the original budget.

While the final forecast TEI for this project of $438.2 million represents an expected saving of $46.2 million against the revised budget, the need to revise the budget indicates that the project was not adequately costed prior to seeking funding. VAGO's 2012 audit Melbourne Markets Redevelopment found that the business case was deficient in relation to project costing and time frame.

Appendix C provides a snapshot of reported and approved budgeted costs for all projects.

2.8.2 Actual versus planned time lines

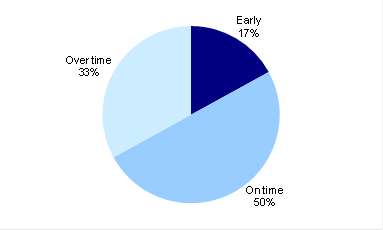

Agencies reported the time lines for 212 of the 251 projects, because 39 projects were in early planning and milestone dates had yet to be determined. Figure 2P shows that half the projects were completed, or forecast to be completed, on time and 17 per cent (37 projects) were delivered early.

Figure 2P

Percentage of projects completed, or forecast to be completed,

early, on time and over time

Source: VAGO survey of 30 agencies, 2015.

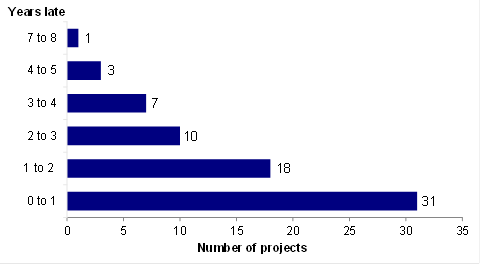

The 70 projects which are or are likely to be late have a budgeted cost of around $5.5 billion, or more than 14 per cent of the total budgeted cost. Figure 2Q shows the time variation of these 70 projects.

Figure 2Q

Projects over time

Source: VAGO survey of 30 agencies, 2015.

Of these projects, almost one-third are more than two years late, as listed in Figure 2R.

Figure 2R

Projects over two years late

Agency |

Project |

Time over |

|---|---|---|

DEDJTR |

Melbourne Market Relocation Project |

7 years 8 months |

Public Transport Victoria |

Regional Fast Rail Passenger Information Displays |

4 years 6 months |

City West Water Corporation |

The Arrow Program |

4 years 0 months |

West Werribee Dual Water Supply Scheme |

3 years 9 months |

|

Melbourne Water |

Aeration Tanks—additional aeration tanks |

3 years 7 months |

Coliban Water Corporation |

Echuca and Cohuna taste, toxin and odour |

3 years 5 months |

Public Transport Victoria |

Replacement of Electrol SCADA System |

3 years 3 months |

VicRoads |

Princes Highway East—Traralgon to Sale duplication |

3 years 3 months |

Public Transport Victoria |

Tram Automatic Vehicle Monitoring System Replacement |

3 years 2 months |

VicRoads |

Western Highway Improvements – Stawell to SA Border |

3 years 0 months |

DHHS |

Efficient Government Building (statewide) |

3 years 0 months |

Public Transport Victoria |

Caroline Springs Station |

2 years 11 months |

DEDJTR |

Frankston Station Precinct Redevelopment |

2 years 11 months |

Public Transport Victoria |

Route 96 |

2 years 9 months |

Places Victoria |

Harbour Esplanade Redevelopment Stage 2 (Docklands) |

2 years 6 months |

DJR |

State Coronial Services Centre |

2 years 4 months |