Assuring the Integrity of the Victorian Government’s Procurement Activities

Audit snapshot

What we examined

We examined if departments use suitable controls to prevent, detect and investigate fraud and corruption when procuring goods and services.

We assessed all 10 Victorian Government departments during the planning stage of our audit. We then selected 3 departments for an in-depth analysis – the Department of Education, the Department of Justice and Community Safety and the Department of Jobs, Skills, Industry and Regions.

Why this is important

The government uses public money to procure goods and services.

Parliament and the public need to know this money is spent fairly and transparently.

Each stage of the procurement process is vulnerable to fraud and corruption. If departments do not manage the risk of fraud and corruption they may lose money or not get value for money.

Departments can manage these risks by using controls to prevent, detect and investigate fraud and corruption.

What we concluded

Departments have further work to do to effectively manage the risk of fraud and corruption when procuring goods and services.

While all departments have fraud and corruption controls, they are at different stages in making sure their controls work as intended. And some controls could be better designed.

All departments have processes for investigating fraud and corruption incidents when they have been alerted to them. But only 2 departments use data analytics to flag unusual or suspicious activity to proactively detect risks.

What we recommended

We made 5 recommendations about:

- reviewing and updating fraud and corruption policies and plans

- reviewing and updating procurement, conflict of interest and vendor master files policies and procedures

- reviewing fraud and corruption incidents and other integrity investigations

- introducing regular refresher training

- setting up a data analytics program to proactively identify fraud and corruption risks.

Video presentation

Key facts

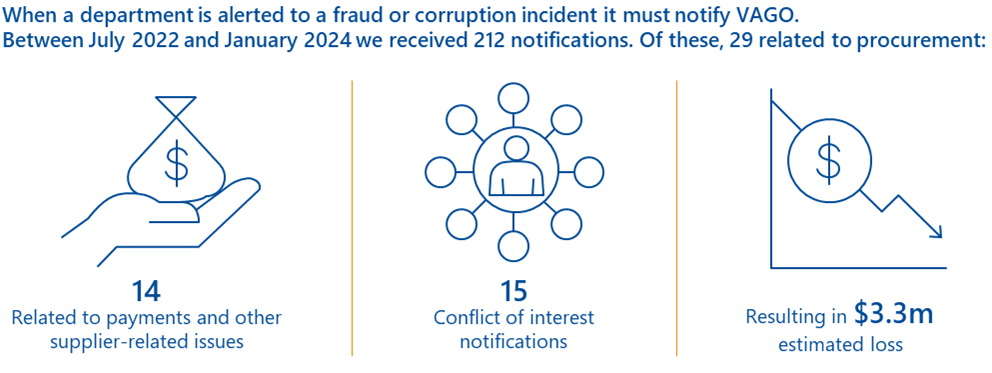

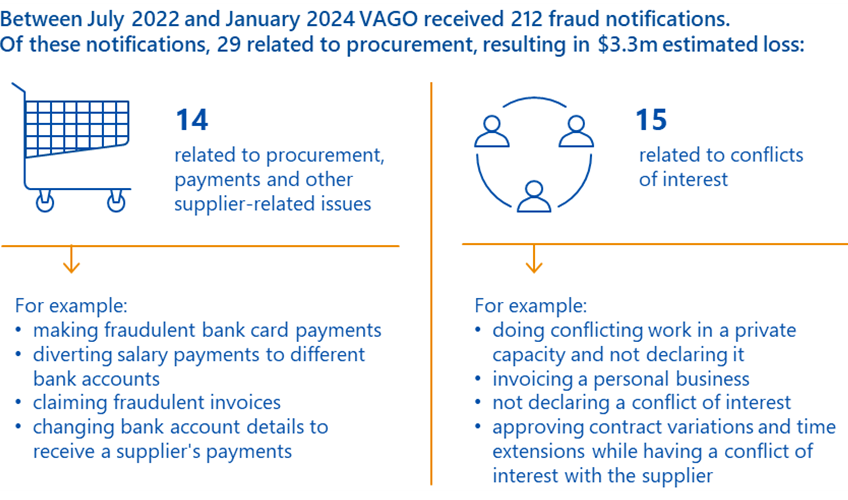

Note: The requirement to report incidents applies to losses above $5,000 in cash or $50,000 in property. Numbers in this graphic have been rounded.

Source: VAGO.

Our recommendations

We made 5 recommendations to departments to address 2 issues. The relevant agencies have accepted our recommendations in full or in principle.

| Key issues and corresponding recommendations | Agency response(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Issue: Departments have controls to prevent, detect and investigate fraud and corruption during procurement. But they are at different stages in making sure their controls work as intended | ||||

| All 10 departments | 1 | Review their fraud and corruption control policies and plans to make sure they are accurate and up to date. At a minimum, this involves setting timeframes to review and update policies and plans (see Section 1). | Accepted by all departments | |

2

| Review and update their policies and procedures for procurement, conflicts of interest and maintaining vendor master files. This should involve reviewing and updating:

| Accepted by 8 departments

| ||

| 3 | Set up a regular monitoring program to review fraud and corruption incidents and integrity investigations to identify how they can improve their controls (see Section 2). | Accepted by 9 departments Accepted in principle by Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action | ||

| Department of Justice and Community Safety | 4 | Introduce a regular training refresher program for all staff that covers fraud and corruption (see Section 1). | Accepted | |

| Issue: Only 2 departments use data analytics to proactively detect fraud and corruption risks | ||||

| Eight departments (excluding the Department of Jobs, Skills, Industry and Regions and the Department of Transport and Planning) | 5 | Set up regular data analytics reviews to assess their procurement activities for fraud and corruption risks. At a minimum, this involves collating and centralising data so they can export and review it (see Section 2). | Accepted by 3 departments Accepted in principle by Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action, Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, Department of Government Services, Department of Premier and Cabinet and Department of Treasury and Finance | |

What we found

This section summarises our key findings. The numbered sections detail our complete findings, including supporting evidence.

When reaching our conclusions, we consulted with the audited agencies and considered their views. The agencies’ full responses are in Appendix A.

Why we did this audit

Fraud and corruption by Victorian public sector employees can damage the government's reputation and waste public resources.

In 2018–19 the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC) identified procurement as one of the highest-risk areas for fraud and corruption in the public sector.

We did this audit to assess if government departments are actively managing these risks by preventing, detecting and investigating fraud and corruption during the procurement process.

The procurement process

Procurement involves the whole process of buying goods or services. The process starts when an organisation identifies that it needs a good or service.

As Figure 1 shows, the process continues through stages to seek quotes, evaluate potential suppliers and award the contract.

Figure 1: Stages of the procurement process

Source: VAGO.

Procurement risks

Fraud and corruption risks can arise at every stage of the procurement process. For example:

| When a department is … | There is a risk that … |

|---|---|

| planning a procurement | an employee could split a procurement into 2 contracts to deliberately avoid needing to follow a competitive bidding process. |

| evaluating and awarding the contract | if a conflict of interest is not declared and known, an employee could be biased towards a potential supplier and skew the evaluation process. |

| paying an invoice | a supplier could submit a false, inflated or duplicate invoice or an invoice with obvious errors. |

AS 8001:2021, Fraud and corruption control

In this audit we assessed departments' fraud and corruption controls for procurement against requirements in:

- the Australian Standard AS 8001:2021, Fraud and corruption control (the Standard)

- the Standing Directions 2018 Under the Financial Management Act 1994 (the Standing Directions)

- Guidance supporting the Standing Directions 2018 under the Financial Management Act 1994.

The Standard outlines the minimum requirements for developing, setting up and maintaining an effective fraud and corruption control system.

Departments do not legally have to follow the Standard. But the Standing Directions recommend that departments make sure their fraud and corruption control policies and frameworks are consistent with the Standard.

Fraud

According to the Standard, fraud is 'dishonest activity causing actual or potential gain or loss to any person or organization including theft of moneys or other property by persons internal and/or external to the organization and/or where deception is used at the time, immediately before or immediately following the activity'.

Corruption

According to the Standard, corruption is 'dishonest activity in which a person associated with an organization (e.g. director, executive, manager, employee or contractor) acts contrary to the interests of the organization and abuses their position of trust in order to achieve personal advantage or advantage for another person or organization'.

Source: The Standard.

Our key findings

Our findings fall into 2 key areas:

| 1 | Departments have controls to prevent, detect and investigate fraud and corruption during procurement. But they are at different stages in making sure their controls work as intended. |

| 2 | Only 2 departments use data analytics to proactively detect fraud and corruption risks. |

Key finding 1: Departments have controls to prevent, detect and investigate fraud and corruption during procurement. But they are at different stages in making sure their controls work as intended

Fraud and corruption controls

The Standard recommends setting up the following controls to prevent, detect and investigate fraud and corruption:

- establish the organisation's fraud and corruption control objectives and values

- develop, implement, communicate and maintain an integrity framework

- develop and implement a fraud and corruption control system

- raise awareness of fraud and corruption control issues

- establish clear accountability structures for escalating and responding to fraud and corruption incidents

- set guidelines on how to recover losses from fraud or corruption.

We found that departments have controls to prevent, detect and investigate fraud and corruption. But they are at different stages in making sure their controls work as intended.

Foundational controls

Departments have controls to prevent, detect and investigate fraud and corruption, including:

- policies and procedures to develop a fraud and corruption control system

- processes to internally report fraud incidents during procurements

- forms and reporting channels to investigate fraud and corruption allegations.

This means departments have the tools to manage and reduce the risk of fraud and corruption during the procurement process.

Applying controls

Departments are at different stages in making sure their controls work as intended.

For example, the 3 departments we looked at in detail have fraud and corruption policies, processes and forms. But the currency of policies and forms differs in practice:

- The Department of Education (DE) has not reviewed its supplier maintenance policy for maintaining its vendor master file in 4 years. This means there is a risk that DE's current process is outdated.

- The Department of Jobs, Skills, Industry and Regions' (DJSIR) conflict of interest declaration forms do not have key fields to confirm that an employee with appropriate authority, such as a manager, has reviewed a conflict and, if required, set up a plan to manage it.

- The Department of Justice and Community Safety (DJCS) has not reviewed its fraud policy in 2 years. DJCS has advised us that this policy is now under review. It intends to publish it in the next quarter.

Vendor master file

A vendor master file is a central database that holds information about an agency’s supplier details, including their bank account details, Australian Business Number (ABN) and invoice records.

Areas for improvement

Departments can improve how they apply their controls by:

- making sure their fraud and corruption control policies, processes and forms are up to date

- reviewing and updating forms and procedures to reflect any changes or gaps in their procurement processes

- reviewing and updating their controls after a fraud and corruption incident.

The 3 departments in our in-depth analysis are at different stages in improving their controls. For example:

- DJSIR is currently updating its conflict of interest declaration form to make sure it captures all the necessary information

- DJCS is updating its fraud policy to make sure it is up to date

- DE is planning training reminders for executives to ensure staff training is completed.

Key finding 2: Only 2 departments use data analytics to proactively detect fraud and corruption risks

Proactively detecting fraud and corruption

Proactively detecting potential fraud and corruption can further reduce the likelihood of a department losing money or not getting value for money during a procurement.

The Standard outlines actions an organisation can take to proactively detect fraud. These actions include:

- setting up a data analytics program to analyse transactions, purchase orders and employee information in real time, near real time or retrospectively

- setting up and promoting clear channels for staff and other relevant parties to report suspicious, fraudulent or corrupt conduct.

We found that all departments have processes for investigating and reporting fraud and corruption incidents when they have been alerted to them.

But only 2 departments use data analytics to proactively detect risks during the procurement process.

Proactively detecting risks

Of the 10 departments, only DJSIR and the Department of Transport and Planning (DTP) use data analytics to proactively detect fraud and corruption risks prior to awarding contracts.

DJSIR's data analytics program reviews its procurement data against its other internal data.

For example, the program compares employee data against DJSIR's vendor list datasets to check if there are undeclared conflicts of interest. If it finds an undeclared conflict, DJSIR can escalate and manage it to reduce the risk of bias during a procurement.

DTP uses specialised software to identify and reduce fraud and corruption risks. For example, the software checks DTP's system for duplicate vendors to reduce the risk of DTP paying the same vendor twice. The software also checks vendors' details to make sure they are up to date and legitimate and it also checks vendors' bank details against employees' bank details.

Barriers to proactively detecting risks

Barriers to the 8 other departments using data analytics to proactively detect fraud and corruption risks include:

- some departments have stalled the projects to develop tests and programs due to competing priorities and a lack of resources

- some departments do not store their procurement data in a format that lets them comprehensively analyse it. For example, they have not collated the data into one system from which it can be easily exported.

1. Preventing fraud and corruption

All departments have controls to prevent, detect and investigate fraud and corruption during the procurement process. Examples of these controls include running fraud and corruption training for new employees and having internal processes to report procurement and integrity matters to senior management.

However, departments are at different stages in making sure their controls work as they intended them to. In particular, not all departments make sure that:

- staff complete and approve conflict of interest declaration forms in a timely way

- more than one person is responsible for making decisions during a procurement.

Most departments run fraud and corruption training for all employees

Recommended training

The Standard recommends that organisations regularly run training for staff on:

- the organisation’s risk of fraud and corruption

- how to respond if they detect or suspect fraud and corruption.

IBAC recognises that the procurement process has a higher risk of fraud and corruption because:

- it can involve large sums of public money

- it can be affected by limited oversight and inadequate staff training.

To reduce this risk, IBAC recommends that departments run mandatory:

- regular training for staff on fraud, corruption and conflicts of interest during procurement

- specialist training for staff who have higher-risk roles.

We found that most departments run induction training that covers fraud and corruption.

The 3 departments in our deep-dive analysis (DE, DJCS and DJSIR) run specific mandatory training and keep participation records. DE and DJSIR require existing staff to do refresher training. All 3 departments run specialist training for staff in higher-risk roles.

Mandatory training at induction

Nine out of 10 departments run induction training for new staff that covers some information on fraud and corruption, such as:

- what constitutes fraud and corruption

- how to identify it

- how to report potential incidents.

One department, the Department of Government Services, had not developed this training as at June 2024.

The departments in our deep-dive analysis provide specific fraud and corruption training for new staff as part of their broader integrity training.

These 3 departments all:

- require new staff to participate in this training during induction

- keep participation records.

This helps these departments make sure new employees understand what fraud and corruption is and their responsibilities to prevent and report it.

Refresher training

The Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre recommends that government officials complete regular refresher training on fraud and corruption.

Of the 3 departments in our deep-dive analysis:

- DJSIR requires staff to do refresher training every year

- DE requires all staff to do refresher training every 2 years

- DJCS does not require its staff to do refresher training.

By running refresher training, DJSIR and DE regularly remind staff about their responsibilities for preventing, detecting and reporting fraud and corruption.

DJCS told us it intends to start requiring all staff to do mandatory refresher training every 2 years. DJCS has updated this training and, as of May 2024, this is pending approval.

Following up on training

All 3 departments in our deep-dive analysis follow up employees who have not completed the training:

- DJSIR sends email reminders to staff near the end of their performance cycle. It also requires managers to review if the staff they oversee have completed the training.

- DJCS sends email reminders to staff 7 days before the training due date. If an employee does not complete training by this date, it sends another email one day after it is overdue. Managers are responsible for following up on training to make sure employees complete it.

- DE sends reminder emails to its executives about staff training. Managers are responsible for following up to make sure employees complete training.

Specialist training

In addition to their mandatory fraud and corruption training, DE, DJCS and DJSIR also run additional training for staff in roles that they assess as higher risk.

DE has an integrity capability tool that outlines fraud and corruption, procurement and contract management capabilities for:

- staff working in corporate areas

- people managers

- senior leaders.

The tool covers information for employees at these levels, including expected behaviour and capability goals. It also links to internal and external learning and development resources.

DJCS has recently started running integrity training for non-executive people managers, with a two-streamed program for custodial and non-custodial workforces.

The aim of this training is to help employees:

- manage staff who are not meeting behavioural expectations

- report fraud and corruption.

DJCS also has separate training for new managers and refresher training for frontline and public-facing staff.

DJSIR has specific integrity training for:

- managers and executives

- contractors.

Procurement training

DE's, DJSIR's and DJCS's procurement training covers some content on fraud and corruption, including their expectations for staff to prevent and detect it during the procurement process.

This helps these departments make sure that staff who are involved in procuring goods and services understand their responsibilities to prevent fraud and corruption in this context.

All departments have policies for screening new employees and the 3 deep-dive departments have offboarding processes to prevent unauthorised users accessing their systems and equipment

Employee screening and offboarding

The Standard recommends that organisations have a process to screen new staff before appointing them.

Screening applicants can reduce the risk of fraud and corruption by identifying potential risk factors, such as prior criminal convictions associated with dishonesty.

In the Victorian public sector, departments complete pre-employment screening before a new employee starts working.

It is also important that departments have controls to prevent fraud and corruption when an employee resigns. Offboarding processes help departments:

- protect their systems from unauthorised users

- prevent departing employees from leaking confidential information via email.

Pre-employment screening

All departments have policies that require pre-employment screening when they recruit new staff.

The Victorian Public Sector Commission provides guidance about how to do these checks. It requires departments to do the following checks:

- misconduct screening for all employees, which checks for misconduct within the last 7 years

- misconduct screening for executives, which checks for misconduct within the last 10 years

- a police check.

We found the policies of the 3 deep-dive departments comply with the Victorian Public Sector Commission's requirements.

DE, DJCS and DJSIR also require successful candidates for high-risk positions to declare their private interests before their employment starts.

Staff in high-risk positions include financial delegates, staff in key decision-making roles and staff who approve new processes.

Offboarding employees

Organisations use offboarding processes to remove an employee's access to their systems and records when they leave the organisation.

DE, DJCS and DJSIR have checklists to make sure they complete their offboarding processes.

Their processes all involve revoking the departing employee's access to their systems and requiring them to return the department's property, corporate cards and security passes.

DJSIR and DE have automated their offboarding process to make sure it is followed consistently.

Monitoring departing employees' emails

DE told us it does not monitor departing employees' emails due to privacy considerations.

DJSIR told us it does not monitor departing employees' emails unless there are circumstances that trigger it to access and review employee emails under the relevant policies, such as investigating suspected fraud, corruption or misconduct.

DJCS told us it only monitors outbound emails from departing employees when it has identified integrity risks.

DJCS is piloting a routine email monitoring program that scans outbound emails from identified high-risk business areas to private email addresses, whether or not an employee has resigned.

Departments have policies for preventing and managing conflicts of interest, but they need to improve their templates, forms and processes in practice

Controls for reducing fraud, corruption and conflicts of interest

IBAC recommends that public sector agencies use the following controls to reduce the risk of fraud and corruption:

- conduct audits to check the accuracy of invoices and confirm if suppliers have delivered goods and services

- check financial delegate paperwork is complete before approving spending

- control subcontracting processes

- monitor tenders and contracts to detect contract splitting

- require staff to sign invoices to verify the agency has received the goods and services

- use payment system controls to detect duplicate invoices

- run regular training for staff.

Conflicts of interest

The Standard defines a conflict of interest as a situation where a person's business, financial, family, political or personal interests could interfere with their judgement while carrying out their duties for an organisation.

The Standard recommends that organisations have a policy and/or procedure for staff and relevant business associates, such as a supplier who provides a quote for tender, to disclose actual, potential or perceived conflicts of interest.

The Standard also recommends that organisations:

- monitor and actively manage declared conflicts of interest to reduce the risk of fraud and corruption

- keep records of:

- staff's relevant business, financial, family, political or personal interests that could conflict with their duties at work

- actions they have taken to avoid, eliminate or manage any perceived, potential and/or actual conflicts of interest.

If a department ignores or conceals a conflict, or a conflict influences an employee's decision, it could be seen as misconduct or abuse of public office.

Managing conflicts of interest

All 10 departments have policies that require staff involved in a procurement to declare conflicts of interest.

Their policies require:

- an appropriate authority, such as the procurement's evaluation panel chair or the declarer's line manager, to sign off declaration forms to record they have reviewed them

- the declarer and approver to complete and record a management plan when a conflict has been identified.

We looked at 311 conflict of interest declaration forms across 27 procurements at DE, DJCS and DJSIR. In this sample we found examples where:

- forms were not approved

- forms were not approved in a timely way

- the department did not follow its processes for probity advisor reviews

- a procurement was exempted from using an existing professional advisory service but staff did not complete declaration forms.

Probity in procurement

In the procurement process, probity involves:

- making sure processes, actions and decisions are consistent, accountable, transparent and auditable

- keeping complete records and maintaining an audit trail

- communicating clearly and honestly

- making sure checks and approvals are independent

- keeping information secure and confidential

- identifying and managing actual, perceived and potential conflicts of interest.

Professional advisory service

A professional advisory service is a service provided by an expert, such as an accountant, lawyer or surveyor, to offer guidance and recommendations to an organisation. This advice helps the organisation make informed decisions and mitigate risks.

Declaration forms

Of the 311 conflict of interest declaration forms in our sample, at least 10 per cent of each department's declaration forms had not been signed off for approval by an appropriate authority.

This means we could not verify if an appropriate authority had reviewed them or not.

The departments also did not have management plans for some declared conflicts.

This means we could not assess if the departments had considered the risk of these staff continuing to be involved in a procurement.

At the time of our review, DJCS's, and DJSIR's declaration form templates did not request enough detail from declarers to help them actively manage and mitigate risks.

Figure 2 outlines some of the gaps we found in their declaration forms. It also explains how these gaps could impact the effectiveness of their other conflict of interest controls.

Figure 2: Gaps in DJCS's and DJSIR's declaration forms

| Department | Gap | Impact |

|---|---|---|

DJCS

| No field for staff or approvers to identify the declarer or approver's role in the procurement process

| DJCS cannot verify:

|

| DJSIR | Offline and online versions of the form did not have the same fields | There is a risk that DJSIR did not consistently collect all the information it needs to assess and manage conflicts of interest across all its procurements. |

Source: VAGO, based on information from DJCS and DJSIR.

DE, DJCS and DJSIR told us that they are in various stages of updating and introducing new declaration forms:

- DE told us it is finalising a new form.

- DJCS told us it is updating its integrity processes. It digitised and launched its new conflict of interest declaration form in March 2024.

- DJSIR told us it launched a new form in February 2024.

Timeliness targets

DE, DJCS and DJSIR have expectations for when employees must complete conflict of interest declaration forms during the procurement process.

DE and DJCS require employees to complete a declaration form before they evaluate tender submissions.

DJSIR requires staff on the evaluation panel to complete a form before viewing any tender responses.

Of the 311 declaration forms we looked at:

- 136 were not approved

- 66 were approved on the day the declaration was completed

- 93 were approved at least one day after the declaration was completed. Of these:

- 24 were approved more than 3 months later

- one was approved 7 months later

- 16 were approved but did not specify when, so we could not verify timeliness.

Approving declarations in a timely way is important because it can reduce the risk of unmitigated conflicts of interest during a procurement.

Probity advisors and auditors

A probity advisor gives a department independent and objective advice on its procurement activities. A department can engage a probity advisor to help it make sure its procurement processes are fair and transparent.

A probity auditor reviews a department's compliance with tender documents, government policies and probity principles at one or more key milestones during a procurement. An auditor also reports on the outcomes of procurements.

DE's, DJCS's and DJSIR's procurement policies require them to use a probity advisor for certain procurements. For example, high-value or more complex procurements.

In the 27 procurements we tested, 21 required a probity advisor or auditor because they were over a specified value or the department deemed them as high risk. Of these 21 procurements, one from DJCS did not have an explanation why an advisor or auditor was not involved.

Of the 46 declaration forms that included probity sign-off:

- 2 were signed off by the advisor or auditor on the day the declaration was completed

- 29 were signed off by the advisor or auditor at least one day after the declaration was completed

- 13 were signed off but did not have a sign-off date

- 2 did not have a declaration date, so we could not verify the timeliness of the reviewer or auditor's sign-off.

We could not verify what departments considered timely for probity advisor or auditor sign-offs because their policies do not specify timeframes.

Procurement exemptions

A department may need to get an exemption from following its procurement process when the good or service it needs can only be provided by a particular supplier, or the good or service is for a limited trial.

For example, if a department needs to procure specialist software to resolve a critical incident that is disrupting an essential service there may be grounds for an exemption from the procurement process.

Procurement exemptions depart from the standard process because they typically do not involve competitive bidding or approval at key stages.

When a procurement gets an exemption from following the standard process, the department needs to rely on its other fraud and corruption controls, including conflict of interest controls, to make sure it still follows a robust process.

Of the 9 procurements we looked at that had exemptions from the standard process, 2 did not have completed conflict of interest declarations for all staff who were involved.

Separation of duties is clear in departments' policies, but this is not always confirmed in practice

Separating duties

Guidance supporting the Standing Directions 2018 under the Financial Management Act 1994 recommends that agencies make sure they delegate decision-making to more than one person during the procurement process.

Separating roles and delegations is particularly important when an agency is:

- sending or receiving money

- signing or administering a contract

- remunerating staff.

This is because these activities have a higher risk of fraud or corruption.

Agencies can minimise this risk by:

- clearly documenting the roles and responsibilities of individuals involved in a procurement

- making sure their policies clearly outline who is the appropriate approver or delegated authority for procurements.

Separating duties

Separating duties is when an agency requires more than one person to complete tasks to make sure no one delegate has control or authority over an end-to-end process.

In procurement, this means that different employees are responsible for the steps required for spending public money.

Gaps in documentation

All 10 departments have policies that require them to separate duties during the procurement process.

We did not find evidence that DE's, DJCS's or DJSIR's employees had inappropriate access or responsibility across the 27 procurements we looked at in detail.

However, there were gaps in DE's, DJCS's and DJSIR's documentation that made it difficult for us to confirm that they consistently maintained appropriate separation of duties beyond the scope of the 27 procurements we looked at.

For example, 303 of the 311 conflict of interest declaration forms we looked at did not identify the approver's role. This means we could not confirm if the approver:

- had another role in the procurement that conflicted with their role as an approver

- had the appropriate authority to approve declaration forms.

For 68 of the 311 declaration forms, the declarer did not identify their job title or their role in the procurement. Of these 68 forms, 5 identified a conflict of interest. This means we could not confirm if these declarers were involved in receiving or approving purchases or had access to financial systems.

It is important that departments clearly document the roles and responsibilities of staff members involved at each stage of a procurement to make sure:

- their duties do not conflict with each other

- no staff member is solely responsible for making decisions across the lifecycle of a procurement.

All departments have policies to screen new suppliers, but their policies do not require staff to review ongoing suppliers

Victorian Government Purchasing Board

The Victorian Government Purchasing Board (VGPB) sets the policies that govern procuring goods and services for all Victorian Government departments.

VGPB has published a set of procurement guides to help departments make sure their procurements are fair, open and transparent.

The guides suggest departments include in their evaluation plan the ways to assess a tender offer against the evaluation criteria. This is important because it allows the procurer to verify that the offer meets requirements and to inform risk assessments.

Validating suppliers

The Standard provides an extensive list of checks an organisation should consider to validate a potential supplier.

This can help the organisation make sure a new supplier is viable and legitimate before it awards them a contract.

If the organisation finds there is a heightened risk of fraud and corruption it should consider not proceeding with the business relationship.

The Standard also recommends that organisations periodically confirm the legitimacy of ongoing suppliers to reduce the risk of them becoming complacent about certain controls.

Validating a supplier

Validating a supplier involves doing checks to make sure they are legitimate. These checks can include:

- searching a company register for the supplier's details

- confirming ABN and bank account information

- searching for pending legal proceedings and judgements to check the supplier can legally do business

- confirming that the supplier's directors or management have not been disqualified from operating.

Screening new suppliers

All 10 departments' procurement policies and processes require them to complete some level of checks before contracting a new supplier.

For example, DJCS's process requires it to research the history and activities of a potential supplier's parent company.

DE's process involves using a professional advisory service to formally assess financial risks before awarding a contract.

DJSIR's process specifies that it can use a supplier's annual report to confirm its employee headcount. This is an effective way to check the supplier has the capacity to complete the department's scope of work. It is also a useful way to check the validity of a potential supplier's tender response when they have identified the capacity of their business.

However, none of the 10 departments' policies require them to periodically check ongoing suppliers.

Guidance in policies

DE's, DJCS's and DJSIR's policies recommend doing reference checks to evaluate potential suppliers, including using weighted evaluation criteria.

However, their policies have limited guidance for staff involved in procurements about:

- what the procurer must consider when deciding how much weight to assign to due diligence checks when completing a value-for-money assessment

- how to use information they receive through due diligence checks to inform the suitability of the offer.

Only DE's policy outlines the level of due diligence checks required when a procurement is high risk or highly complex.

Weighted evaluation criteria

Weighted evaluation criteria are criteria that an evaluation team uses to score tender responses.

Examples of commonly used criteria include the potential supplier's capability, past performance and current work.

An evaluation team can rank criteria based on their importance to their organisation.

For example, an organisation that values a potential supplier's competence may assign a higher weighting, such as 60 per cent, to the competence criteria.

Departments' policies for preventing, detecting and investigating fraud and corruption are not always up to date. But departments communicate employees' responsibilities for preventing and reporting incidents through other channels

Communicating roles and responsibilities

The Standard recommends that organisations clearly communicate employees' roles and responsibilities in detecting and reporting fraud and corruption.

This includes:

- distributing information in a way that is easily accessible to the wider organisation

- keeping policies and procedures up to date.

Communicating with staff

The departments in our deep-dive analysis communicate this information via their intranet and other internally distributed material. For example, they:

- email staff links to:

- fraud and corruption frameworks

- channels where they can report suspected fraud and corruption

- distribute resources, such as internal newsletters, on integrity

- post information on their intranet about what fraud and corruption risks are.

Keeping policies, plans and procedures up to date

The Standard recommends that organisations keep their fraud and corruption control system up to date by:

- regularly reviewing their fraud and corruption policies, plans and procedures

- updating their policies, plans and procedures to reflect recent risk assessments and process changes.

We found that 4 departments had either:

- never reviewed their fraud and corruption policies

- not scheduled to review their policies

- not reviewed their policies within their set timeframes.

At the time of our assessment in September 2023, the Department of Government Services was recently established and had only developed basic fraud and corruption control policies.

Departments have policies for internally reporting on integrity and procurement activities and risks

Reporting requirements

The Standing Directions require departments to report on both their procurement activities and fraud and corruption incidents.

The Standing Directions require:

- departments to include fraud and corruption detection and reporting in their processes for managing fraud, corruption and other losses

- a department's accountable officer, such as its secretary, to:

- attest in the department's annual report for the relevant financial year its compliance with applicable requirements in the Financial Management Act 1994, the Standing Directions and the Instructions supporting the Standing Directions 2018 under the Financial Management Act 1994

- disclose all material compliance deficiencies.

Material compliance deficiency

According to Guidance supporting the Standing Directions 2018 under the Financial Management Act 1994 a material compliance deficiency is a gap that ‘a reasonable person would consider has a material impact on the Agency or the State's reputation, financial position or financial management'.

Source: Guidance supporting the Standing Directions 2018 under the Financial Management Act 1994.

Internal reporting policies

All 10 departments have a policy and process for internally reporting fraud and corruption incidents.

Their policies also require staff to externally report incidents to integrity bodies, including VAGO, IBAC and the Victorian Ombudsman, when the Standing Directions require it.

Internal reporting

The departments in our deep-dive analysis adhere to their reporting policies.

They all provide regular integrity-related updates to their audit and risk committees.

This reporting includes:

- information on fraud and corruption incidents

- the number of open investigations or assessments

- the content of these investigations.

Reporting to VGPB

VGPB requires each department to annually attest:

- that its governance framework establishes processes, authorities and accountabilities for the department's procurement function

- that it has an activity plan that shows its upcoming procurements for the year

- that it has an action plan to reduce risks from staff resourcing, approaching the market and managing probity.

VGPB uses this information to confirm that the department complies with VGPB's supply policies and, if the department complies, VGPB gives it accreditation. To maintain VGPB accreditation, departments complete an annual attestation that their policies align with VGPB's policies.

The departments in our deep-dive analysis have completed this attestation for each year that we tested within the scope of this audit.

Departments continue with some procurements despite key documents not being approved

IBAC's corruption red flags

According to IBAC, there is a higher risk of fraud and corruption at certain approval stages in the procurement process:

| When a department approves ... | There is a risk that … |

|---|---|

| a new procurement | staff may not keep the appropriate paperwork or document decisions. |

| a new supplier | staff may not submit the appropriate paperwork to support the decision. |

To mitigate these risks, IBAC recommends that organisations check financial paperwork is complete before approving a contract with a new supplier.

Approving procurements

Departments need to document approvals at key stages of the procurement process to:

- make decisions transparent

- make sure the approval process follows their procurement policy.

For the 27 procurements we looked at, DE, DJCS and DJSIR had documentation to show that an appropriate authority had approved the procurement.

However, not all the key documents from DJCS and DJSIR were approved. For example:

- market strategies for 3 procurements were not approved and of these, one did not get documented approval until the stage for awarding the contract

- one procurement did not have approval for awarding the contract but the tender evaluation team's report on the outcome of their evaluation was approved

- none of the 8 evaluation plans we looked at were approved.

DE manages its approvals, including approvals of conflict of interest declaration forms, online within its Oracle system.

Departments’ policies require them to check supplier details before changing their vendor master file

Verifying changes

The Standard recommends that departments independently verify updates to their vendor master file. This can involve:

- checking suppliers' details compared to tenders and quotes

- searching the Australian Securities and Investments Commission's registers to identify possible links between prospective suppliers and employees

- checking suppliers have appropriate assets or business facilities.

These checks apply to both new and existing suppliers.

To reduce the risk of fraud and corruption from doing business with an illegitimate supplier, the Standard recommends that a department regularly checks a supplier's general details are correct.

To maintain an accurate and complete vendor master file and do thorough checks, departments need:

- clear procedures on how to maintain the file

- clear accountabilities for who maintains the file

- up-to-date policies.

Maintaining vendor master files

Eight departments have a documented procedure for managing their vendor master file. But these procedures mostly refer to updating bank details.

These departments require either their finance team or the business unit undertaking a procurement to verify changes to their vendor master file before making them. This includes:

- seeking additional documents to confirm a supplier's bank and ABN details

- calling a supplier to confirm a change.

Vendor master file fraud notifications

VAGO received 212 mandatory fraud notifications between July 2022 and January 2024 across all government departments and agencies.

Of the 212 notifications, 5 related to unauthorised changes to a vendor master file. This included:

- one case where an employee substituted their bank account details in place of a supplier's details to receive payments intended for the supplier

- one case where a scammer provided bank account details to a department under the guise of an existing supplier. The department went on to pay invoices to this bank account.

Departments also notified us of 4 cases where bank details in their master file were changed due to a cyber attack.

Departments can reduce the risk of these incidents by proactively monitoring and managing their vendor master file.

Supplier maintenance processes

DE, DJCS and DJSIR get regular reports from their finance teams on changes to their vendor master files.

Each department has different controls to prevent vendor master file fraud. But we found remaining risks at each department:

- DE has a supplier maintenance policy for maintaining its vendor master file. But it has not reviewed this policy for 4 years. This means there is a risk that DE's current process is outdated.

- DJCS manually checks its suppliers' details. This is in line with its process. But manual checks introduce the risk of human error or the reviewer unintentionally overlooking key details.

- DJSIR relies on the individual business unit undertaking a procurement to confirm a new supplier's payment details. This is in line with its process. But it means the department cannot oversee the checks to make sure they are comprehensive and regular.

2. Detecting and responding to fraud and corruption

All departments have processes for investigating and reporting fraud and corruption incidents when they have been alerted to them by individuals.

Most departments test their procurement data to look for procurement and financial errors. However, only 2 departments use data analytics tests that specifically focus on proactively detecting fraud and corruption risks.

Only 2 departments use data analytics to proactively detect fraud and corruption risks

Proactively detecting risks

The Standard recommends that departments proactively identify and detect fraud and corruption.

This can include:

- using data analytics to assess data, such as:

- comparing employee information with supplier details or gift, benefits and hospitality data

- flagging irregular transactions

- identifying early warning signs

- analysing management accounting reports.

Using data analytics to detect risks

Eight departments advise that they do not proactively use data analytics to detect fraud and corruption risks prior to awarding contracts. Of these 8 departments, 3 aimed to set up a data analytics program to test their fraud and corruption vulnerabilities but have not yet set these up due to competing priorities and a lack of resources.

Of the departments in our deep-dive analysis, DE and DJCS test their procurement data. But these tests are not designed to specifically identify fraud and corruption risks in their procurements.

For example, DE uses computer-assisted auditing tools under its continuous control monitoring program. The program uses an automated system to check invoices each day before the department pays suppliers. The department uses the program to detect errors in its procurement and payment activities. But the program does not identify early warning signs of fraud and corruption risks.

DJCS does not have a data analytics program to proactively detect fraud and corruption. However, it does quarterly variance testing for financial reporting purposes. But these tests also do not identify early warning signs of fraud and corruption risks.

Variance testing

Variance testing involves detecting odd instances or outliers in a dataset. For example, comparing transactions across multiple financial years and identifying irregular payments or payments that are consistently under a threshold that would have otherwise required additional financial approval.

Good-practice examples

DJSIR and DTP are the only departments that use data analytics to proactively detect fraud and corruption during the procurement process.

DJSIR uses data analytics to compare:

- employee data against other datasets, such as vendors, ABNs and grants

- gifts, benefits and hospitality data against procurement data.

DJSIR also does spot checks and tests depending on its reporting needs. These checks and its use of data analytics help it further investigate fraud and corruption incidents and risks.

In 2019 DTP started a pilot data analytics program to proactively detect fraud and corruption risks. Since then, DTP have acquired a specialised analytic software to identify red flags in its processes and reduce the risk of fraud and corruption.

This pilot program considers risks outside the procurement process, such as duplicate invoices. But it also monitors areas that are vulnerable to fraud and corruption, such as updates to DTP's vendor master file and employee and supplier relationships.

DTP's data analytics testing includes:

- checking active supplier details against cancelled ABNs

- matching vendor addresses to employee addresses.

Most departments have procedures to investigate and respond to incidents

Fraud and corruption investigations

The Standard recommends that departments have:

- a procedure for investigating and responding to a fraud or corruption incident

- an action plan to investigate all incidents.

The Standard also recommends that departments use appropriately skilled, experienced, independent investigators to:

- reduce the risk of conflicts of interest

- make sure they get objective advice.

Examples of independent investigators include:

- an external law enforcement agency

- a specialist fraud and corruption resource within the organisation

- an internal manager or other senior person.

The Standard emphasises that is it important for departments to prepare and maintain adequate records for all investigations.

Investigation process and manuals

All departments have a high-level process for managing and reporting fraud and corruption incidents. Their processes:

- outline the steps to complete an investigation

- require the department to refer incidents to an appropriate integrity agency or Victoria Police after it has assessed the seriousness of the event.

In addition to this:

- 4 departments have specific templates and manuals for investigations

- 2 departments have documented forms, manuals or guides for their investigations

- one department is currently updating its investigation manual

- one department has forms and a process for conducting IBAC and public interest disclosure assessments.

Four departments' policies say the department can choose an external party to do an investigation. But only one of these policies specifically requires the investigator to be experienced and independent.

DE's, DJCS's and DJSIR's investigation processes

DE, DJCS and DJSIR have processes and action plans to investigate and respond to alleged fraud and corruption incidents.

We looked at 18 cases of procurement fraud or corruption at these 3 departments from 2022 to 2024. We found that they followed their processes and action plans in practice.

Of these incidents:

- all were assessed by internal investigators

- DE and DJCS had 11 cases in which they determined that no formal investigations were needed. This is in line with their process to assess if an incident needs a formal investigation

- DJSIR referred 4 of its 7 incidents to its internal workplace relations business unit

- all 3 departments documented case notes, evidence and outcomes in their case management systems.

DE's and DJCS's incidents were reported by individuals.

DJSIR was alerted to 4 of its 7 incidents by its data analytics program or routine compliance checks by its integrity team. The remaining 3 were reported by individuals.

This highlights the benefits of proactively assessing risks.

All departments have policies that require them to follow the Standing Directions' requirement to report incidents to VAGO and other bodies

Reporting fraud and corruption incidents

The Standing Directions require agencies to report suspected significant or systemic fraud, corruption and other loss to:

- VAGO

- their responsible minister

- their audit and risk committee

- their portfolio department, for example, a school reporting to DE.

The Standing Directions also require the department to take remedial action as soon as practicable.

This requirement applies to losses above $5,000 in cash or $50,000 in property.

All 10 departments' fraud and corruption policies require them to report incidents to VAGO and other responsible bodies.

All 3 departments in our deep-dive analysis also internally report on fraud and corruption incidents, including reporting to their audit and risk committees.

Reporting incidents to VAGO

We reviewed DE's, DJCS's and DJSIR's fraud and corruption registers and VAGO's mandatory notifications register between July 2022 and January 2024.

We also asked for and received clarification from these departments on all mandatory fraud notifications sent to VAGO, not just notifications related to procurement.

All 3 departments confirmed the number of notifications they made to VAGO between July 2022 and January 2024. The departments' records match VAGO's records.

This demonstrates that DE, DJCS and DJSIR comply with the Standing Directions' requirement to report fraud and corruption incidents to VAGO.

Figure 3 shows the number, type and estimated loss for procurement-related mandatory fraud notifications made to VAGO by government departments and agencies between 2022 and 2024.

Figure 3: Mandatory fraud notifications VAGO received between July 2022 and January 2024

Note: Numbers in this graphic have been rounded. Of the 212 notifications, 183 did not relate to procurement, fraudulent bank detail changes, fraudulent suppliers or conflicts of interest. These notifications include incidents such as arson, medical certificate fraud and falsifying funding requests.

Source: VAGO.

Departments do not consistently review and update their controls after an incident

Reviewing existing controls

The Standard recommends that organisations assess their controls after a fraud or corruption incident to consider if they need to update them.

Eight departments' fraud and corruption policies state they will consider learnings from incidents to review and update their controls.

It was not clear if DE, DJCS and DJSIR review controls after every fraud and corruption incident because only some incidents led to updates.

An update may not be required each time an incident occurs. But consistently reviewing controls after an incident can help departments prevent future fraud and corruption incidents.

Updating existing controls

DE, DJCS and DJSIR have updated their controls after some fraud and corruption incidents.

For example:

- DE changed its financial policies and processes after identifying a fraud event at a school

- DJCS and DJSIR expanded their integrity training to business units after identifying fraud events.

Updating controls can protect departments from future fraud and corruption risks because it reduces the likelihood of a similar incident happening again.

Appendix A: Submissions and comments

Download a PDF copy of Appendix A: Submissions and comments.

Appendix B: Abbreviations, acronyms and glossary

Download a PDF copy of Appendix B: Abbreviations, acronyms and glossary.

Appendix C: Audit scope and method

Download a PDF copy of Appendix C: Audit scope and method.