Digital Dashboard: Status Review of ICT Projects and Initiatives – Phase 2

Overview

This audit is Phase 2 of the 2015 Digital Dashboard: Status Review of ICT Projects and Initiatives. It examined six information and communications technology (ICT) projects to determine if they were appropriately planned, managed and implemented in terms of time, cost, benefits realisation and governance.

The audit confirms that ICT projects continue to show poor planning and implementation with cost and scheduling overruns. While one of the six projects examined finished on schedule, none was or will be completed as initially budgeted. One project was terminated prior to system delivery, six years after its planned completion date and over twice its intended budget. Most of the projects examined faced significant challenges at various points during implementation.

Despite this, the audit saw some elements of better practice at the University of Melbourne and Yarra Valley Water which contributed to project completion.

Clearly defined governance arrangements do not necessarily guarantee a successful ICT project. Agencies should work on developing a robust culture of active governance at the senior management level to make informed decisions and to effectively engage with consultants and vendors.

The audit restates better practice elements from VAGO’s 2008 guide, Investing Smarter in Public Sector ICT, to assist agencies in delivering successful ICT projects.

Link to Digital Dashboard: Status Review of ICT Projects and Initiatives – Phase 1

Digital Dashboard: Status Review of ICT Projects and Initiatives – Phase 2: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER March 2016

PP No 146, Session 2014–16

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Digital Dashboard: Status Review of ICT Projects and Initiatives – Phase 2.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

March 2016

Auditor-General's comments

|

Dr Peter Frost Acting Auditor-General |

Audit team Karen Phillips—Engagement Leader Elsie Alcordo—Team Leader Kate Day—Senior Analyst Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Tony Brown |

Auditor-General's comments

Effective information and communications technology (ICT) projects enable government agencies to deliver their programs more efficiently. They meet citizens' growing expectation for faster and more reliable services.

Unfortunately, the Victorian public sector does not have a good track record of successfully completing ICT projects. As highlighted in many previous VAGO audits, and again in this audit, weaknesses in planning and implementation mean that these investments often:

- do not meet functionality expectations nor demonstrate expected outcomes

- cost much more than the planned budget, and/or are delivered much later than planned

- are cancelled prior to completion, while still incurring significant costs.

In one of the audited projects, the government agreed to terminate its investment when it became clear that the vendor could not complete the project—more than six years after its original completion date. This cancelled project cost nearly $60 million in Victorian taxpayers' funds. This is simply not acceptable.

It is the responsibility of the executive leadership teams to ensure that their agencies and entities demonstrate the appropriate behaviours and required skills to ensure successful delivery of ICT projects. A robust culture of active governance at the senior management level enables agencies to make well-considered decisions and to effectively engage with vendors. Being an informed and vigilant ICT buyer is critical to success.

The focus should not just be on the delivery of new capabilities but also on realising the project's intended benefits.

It was heartening to see some elements of better practice that contributed to project completion. The University of Melbourne, Yarra Valley Water and, to some extent, WorkSafe Victoria should be commended for successfully completing their respective projects.

This audit demonstrated the continuing value of the better practice elements in VAGO's 2008 guide Investing Smarter in Public Sector ICT, which were specifically designed to assist agencies to deliver ICT-enabled projects.

Agencies are now in need of further guidance that will allow them to share what they have learned through their ICT projects while also learning from the collective experience of other agencies across government.

Dr Peter Frost Acting Auditor-General

March 2016

Audit Summary

Information and communications technology (ICT) is a significant enabler in the delivery of government programs and services.

With government's increasing reliance on ICT to deliver services and manage information, it is of critical importance that ICT projects are successfully implemented. However, VAGO's April 2015 audit Digital Dashboard: Status Review of ICT Projects and Initiatives – Phase 1 confirmed that agencies and entities find planning and implementing ICT projects particularly complex and difficult. Many of these projects come in well over budget and are delivered much later than scheduled or, on occasion, are cancelled prior to completion.

This second phase of the audit examined in greater detail six of the projects reported in Phase 1 to assess governance effectiveness and benefits realisation.

Conclusions

ICT projects in the Victorian Government should be more effectively planned and managed to avoid cost and schedule overruns. This audit confirms that ICT projects continue to show poor planning and implementation, resulting in significant delays and budget blowouts.

Nevertheless, we saw some elements of better practice at the University of Melbourne and Yarra Valley Water which contributed to the completion of their respective ICT-enabled projects.

While clearly defined governance arrangements do not necessarily guarantee a successful ICT project, agencies should work on developing a robust culture of active governance at the senior management level, to make informed decisions and to effectively engage with consultants and vendors.

The challenges faced by agencies included in this audit are not unique. There are opportunities to learn from the experience of other similarly situated agencies, to better plan and implement effective ICT projects.

Agencies would greatly benefit from revisiting and applying the lessons learned by others in the planning and implementation of their ICT projects. VAGO's July 2008 better practice guide Investing Smarter in Public Sector ICT continues to be sound and relevant, and may be used as a starting point for managing ICT projects more effectively.

Findings

None of the ICT projects considered in this audit were completed or will be completed as initially budgeted. One of the six projects examined finished on schedule. One project was terminated prior to system delivery, six years after the planned completion date and having cost twice the intended budget. Most of the six projects examined in this audit faced significant challenges at various points during implementation.

All six audited agencies had defined and formalised governance arrangements in place for their ICT projects. However, these arrangements did not prevent other project management weaknesses from adversely affecting the effective planning and implementation of their ICT projects. Weaknesses observed include:

- inadequate assessment of the vendor's capability to deliver the project

- ineffective project governance and poor project management

- inability to fully appreciate and specify the business requirements for the ICT system being purchased, including the changes/upgrades required for it to integrate with the existing information technology (IT) infrastructure and systems

- failure to provide appropriately considered advice to senior management at key stages of the project.

Nevertheless, we saw some elements of better practice at the University of Melbourne and Yarra Valley Water, which contributed to the completion of their respective ICT-enabled projects, including:

- clearly articulated business requirements for the ICT systems being procured

- appointment of appropriately skilled project managers and IT personnel in the project team

- consistent and tenacious monitoring of the vendor's progress in project delivery

- commitment to comprehensively and adequately test the new system prior to go-live or project rollout.

Three of the projects examined have been completed. Two of these have benefits-management plans in place and will be in a position to report on benefits realisation at a later stage.

Recommendations

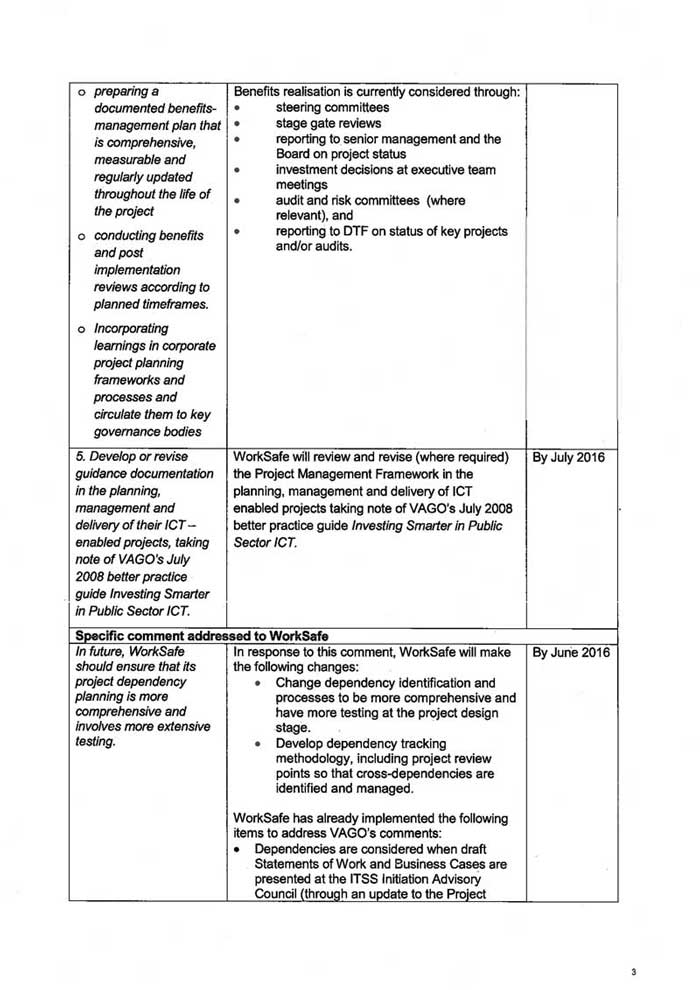

That agencies and entities:

- consider the total project cost—from inception to completion through to evaluation of benefits realisation

- ensure project status reporting is regular, reliable and easy to follow, making agency decision-makers aware of total project cost to date against planned milestones and forecast cost to completion

- ensure that they have the appropriate governance arrangements in place throughout the life of their ICT projects

- ensure there is sufficient focus on the realisation of expected benefits by:

- preparing a documented benefits-management plan that is comprehensive, measurable and regularly updated throughout the life of the project

- conducting benefits and post-implementation reviews according to planned time frames

- incorporating learnings in corporate project planning frameworks and processes and circulating them to key governance bodies

- develop or revise guidance documentation in the planning, management and delivery of ICT-enabled projects, taking note of VAGO's July 2008 better practice guide Investing Smarter in Public Sector ICT.

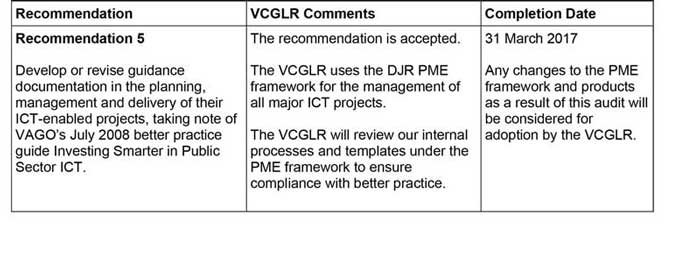

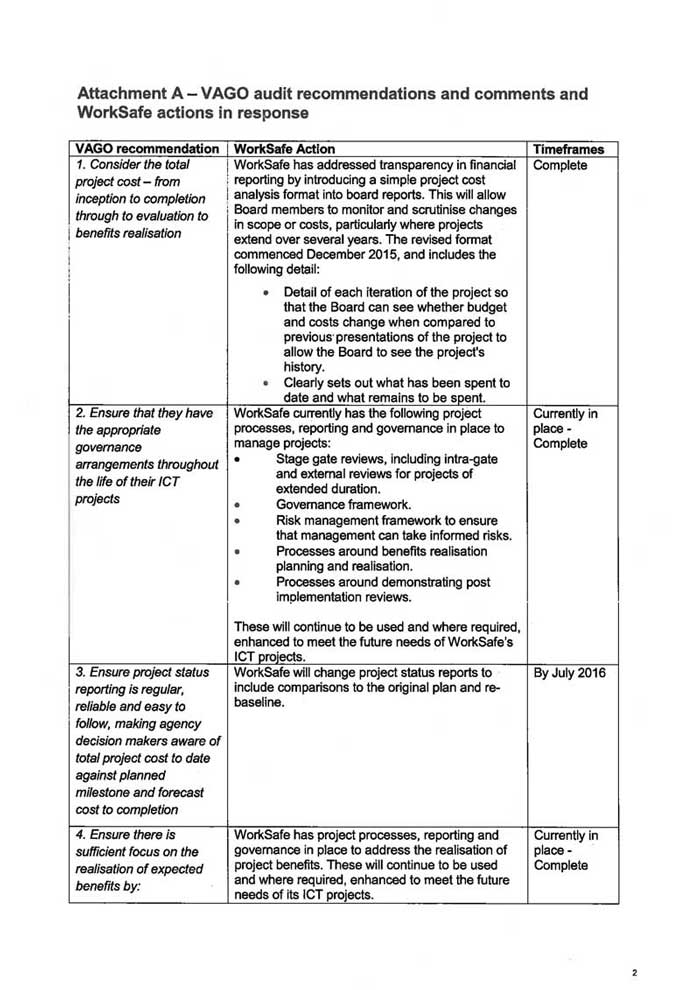

Submissions and comments received

Throughout the course of the audit, we have professionally engaged with:

- City West Water

- the Department of Justice & Regulation

- the University of Melbourne

- the Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation

- WorkSafe Victoria

- Yarra Valley Water.

In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we provided relevant extracts of this report to those agencies and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Information and communications technology (ICT) has become integral to how governments manage information and deliver services. This steadily increasing reliance on ICT is reflected in the Victorian Government's significant $3 billion annual ICT investment across the public sector, as reported by VAGO in its April 2015 report Digital Dashboard: Status Review of ICT Projects and Initiatives – Phase 1

1.2 Digital Dashboard – Phase 1

Digital Dashboard – Phase 1 found significant issues in the development and implementation of ICT projects:

- Nearly 35 per cent of the 1 249 reported projects went over budget or are over budget prior to completion.

- Nearly half of the reported ICT projects were completed, or were expected to be completed, after their initially planned completion dates.

- A business case was prepared for just over 70 per cent of ICT projects, but our review of a sample revealed that only 38 per cent of these business cases included the minimum required elements, such as financial analysis and expected benefits.

- Very few agencies measure the effectiveness of their ICT projects. Of the 788 completed projects, a little over 10 per cent had undertaken some assessment of their expected benefits.

Definitions

The Digital Dashboard – Phase 1 report used the following definitions:

- ICT—any technology that stores, retrieves, manipulates, transmits or receives information electronically or in a digital form. ICT includes communication devices or applications, computer hardware, software, network infrastructure, video conferencing technology, telephones and mobile phones.

- ICT projects—any project or initiative where ICT investment is fundamental to achieving the agreed objectives, benefits or outputs. ICT projects have a defined start and end, and focus on delivering:

- management, information security or infrastructure improvements, e.g. upgrades and asset replacement

- a government strategy or program where ICT is used in whole or in part to effect change and/or deliver outputs and outcomes and/or realise benefits, such as business change—not necessarily technological in nature, e.g. business process improvement, community engagement, legislative policy.

Monitoring ICT expenditure

Whereas 'ICT project expenditure' refers to all cost components associated with a particular project, 'ICT expenditure' refers to an agency's aggregated expenditure for ICT, i.e. capital and operational including all ICT projects' expenditure.

The report highlighted the need for agencies to be committed to and deliberate in recording and maintaining information on ICT expenditure. Parliament and the Victorian community rightly expect that the expenditure of public funds is being appropriately accounted for.

In addition to the obvious transparency requirements of good government, effective monitoring and recording of ICT project expenditure will assist Victorian public sector agencies to understand the true business value of their ICT activities. It is not possible for government to demonstrate the public value of ICT investments when it cannot accurately report on the actual cost.

Cost elements

The Digital Dashboard – Phase 1 report also listed the following cost components that should be considered by agencies when developing the business case and planning the budget for ICT investments. These components should also be reliably tracked and monitored throughout the project's life:

- Hardware expenditure—expenditure on purchasing, leases, maintenance and repair for all physical ICT equipment, such as servers, PCs, terminals, printers, peripherals, printing equipment, networking and telecommunications equipment, materials, accessories and disaster-recovery hardware.

- Software expenditure—expenditure on licences, as well as repair and maintenance for external and standard software, systems software, and standard office productivity applications.

- Services outsourced to external providers.

- External personnel expenditure—external personnel are staff who provide services on a time and materials basis. These staff are generally contractors, but may also be described as consultants.

- Internal personnel expenditure—for all internal Victorian public service staff involved in ICT activities, including all wages and salaries, training, provisions for staff entitlements and staff on-costs.

- Carriage—the costs of providing digital or analogue electronic impulses, including data, voice or video, over a distance.

- Other expenditure—expenditure on occupancy, facilities, utilities and other ICT spend not captured in other cost element categories.

1.3 Digital Dashboard – Phase 2

This second phase of the audit examined in greater detail six of the projects reported in Phase 1. Collectively, over $200 million was initially allocated for the six projects.

City West Water—Arrow Program

The Arrow Program involves a business-wide transformation to migrate most of City West Water's core business and operational systems to an integrated platform. The implementation of an enterprise resource planning solution was originally intended to comprise five key releases:

- financial systems

- asset management

- customer billing

- environmental services (including payroll and human resources functionalities)

- strategy and planning.

In line with the Department of Treasury & Finance's 2009 Corporate planning and performance reporting requirements: Government Business Enterprises, the Arrow Program business case required the Treasurer's approval, as its proposed capital expenditure was greater than $50 million. The endorsement of the Minister for Water—the portfolio minister for City West Water—was also obtained, as this was a precondition of the Treasurer's approval.

In May 2012, following work to develop the requirements for the program and a cost−benefit assessment of the planned functionality, the last two releases relating to environmental services and strategy and planning were removed from the scope of the program.

Department of Justice & Regulation—Infringement Management and Enforcement System Project

The scope of the project was for a new Infringement and Enforcement Management System to replace the legacy system. In 2007, the Victorian Government engaged a contractor to build the new ICT system by October 2009. In early 2015, following significant delays, the parties reached a legal settlement and the project was terminated. At the time of the audit, the Department of Justice & Regulation was looking into procuring a new solution.

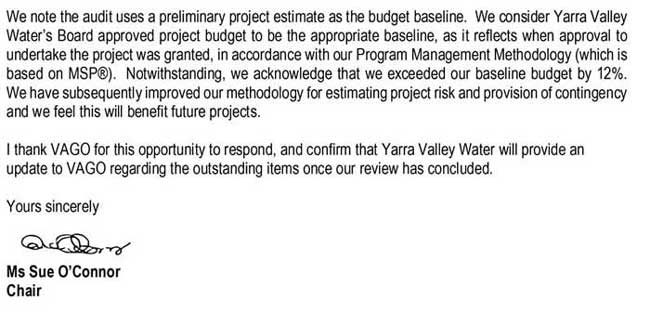

University of Melbourne—ISIS Student Management System Project

The University of Melbourne's (UoM) student management system, ISIS, went live in 2010 as part of a significant university-wide reform agenda. ISIS is a core business system that supports UoM's teaching and research-training mission. It has a significant and highly visible impact on administrative and academic staff, as well as students. ISIS covers major business processes of the student life cycle such as:

- admissions and enrolments

- fees and payments

- results and academic progression

- compliance and government reporting.

Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation—Liquor and Gambling Information System Project

The scope of the Liquor and Gambling Information System Project is for a solution to support the Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation's (VCGLR) operations and to securely capture, link, store and manage data in one place. A predecessor project commenced by the former Responsible Alcohol Victoria (RAV) in 2009 was impacted by the amalgamation of RAV and the Victorian Commission for Gambling Regulation, forming VCGLR in 2012. The project was reinitiated to provide a solution that would support both alcohol and gaming operations. The project is in progress.

WorkSafe Victoria—Electronic Document and Records Management System Project

The scope of the project is an Electronic Document and Records Management System for the storage of documents associated with WorkSafe Victoria claims, to replace the existing paper-based system. Scanned and digitised emails, faxes and paper documents are to be stored in a new electronic document management repository. The implementation of a revised project scope was completed in December 2015.

Yarra Valley Water—Improving Infrastructure Management System Program

Yarra Valley Water's Improving Infrastructure Management System Program included a number of component projects intended to improve infrastructure management systems and address issues with unsupported and ageing infrastructure applications. The implementation of a new asset management system was the final major component of the program and it went live in November 2014.

1.4 High failure rate of ICT projects

The increasing reliance on ICT to manage information and deliver services has led to the implementation of a large number of ICT projects in both government and private organisations across Australia and overseas. Many of these projects have attracted significant attention due to their failure to deliver systems as intended and also because of extensive cost and time overruns.

The Digital Dashboard – Phase 1 report found that nearly 35 per cent of Victorian Government ICT projects went over budget, while some 50 per cent were completed after their initially planned completion dates.

A review of available literature for ICT projects outside Australia suggests similar high failure rates. United States figures for 2015 indicate that 19 per cent of private companies' and government agencies' ICT projects were cancelled prior to completion or were delivered but never used, while 52 per cent were delivered over time, over budget and/or with less functionality than was required.

A review of this literature likewise shows that both private and government organisations have found—and continue to find—it challenging to effectively plan and successfully deliver ICT projects.

1.5 Audit objectives and scope

The objective of the audit is to examine whether Victorian public sector agencies and entities are appropriately planning, managing and implementing selected ICT projects in terms of cost, time, benefits realisation and governance.

1.6 Audit method and cost

This audit involves two phases. This report covers the results of Phase 2. At the discretion of the Auditor-General, subsequent reports may also be prepared.

The audit was conducted in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The cost of the audit was $480 000.

1.7 Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 discusses agency performance in terms of cost and time.

- Part 3 discusses governance and benefits realisation.

- Part 4 discusses lessons learned and better practice elements.

2 Project cost and time

At a glance

Background

VAGO's 2015 audit Digital Dashboard: Status Review of ICT Projects and Initiatives – Phase 1 found that nearly 35 per cent of Victorian Government information and communications technology (ICT) projects went over budget, while some 50 per cent were completed after their initially planned completion dates.

Conclusion

ICT projects continue to show poor planning and implementation, with cost and scheduling overruns a common occurrence. Nevertheless, some elements of better practice were identified in ICT project planning and implementation at the University of Melbourne and Yarra Valley Water.

Findings

- None of the six ICT projects included in this audit were or will be completed as initially budgeted.

- Only one of the ICT projects included in this audit was or will be delivered on time.

Recommendations

That agencies and entities:

- consider total project cost—from inception to completion through to evaluation of benefits realisation

- ensure project status reporting is regular, reliable and easy to follow, making agency decision-makers aware of total project cost to date against planned milestones and forecast cost to completion.

2.1 Introduction

VAGO's 2015 audit Digital Dashboard: Status Review of ICT Projects and Initiatives – Phase 1 reported on the status of 1 249 information and communications technology (ICT) projects across the Victorian public sector.

The audit found that nearly 35 per cent of reported projects went over budget, while some 50 per cent were either completed after their due date or are expected to be completed after their initially planned completion dates.

2.2 Conclusion

ICT projects in the Victorian Government should be more effectively planned and managed to avoid cost and schedule overruns.

While one of the six projects examined finished on schedule, none were completed or will be completed as initially budgeted. One project was terminated prior to system delivery, six years after planned completion date and costing over twice the intended budget. Most of the six projects examined in this audit faced significant challenges at various points during implementation.

Nevertheless, the audit saw some elements of better practice at the University of Melbourne (UoM) and Yarra Valley Water (YVW) which contributed to the completion of their respective ICT-enabled projects.

2.3 Actual versus planned cost

None of the ICT projects included in this audit was completed or will be completed as initially budgeted.

In the case of WorkSafe Victoria, the expected final cost of $25.5 million is less than the initial planned cost of $33.6 million. This, however, followed a WorkSafe-commissioned review that resulted in the de-scoping and subsequent removal of some functionality from the original project scope.

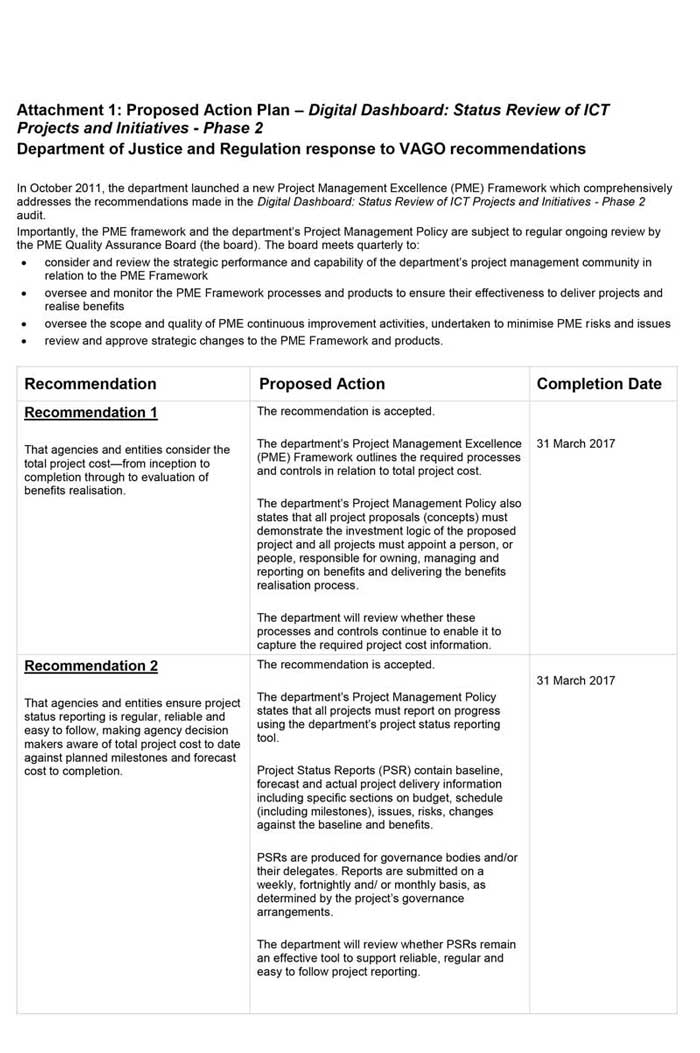

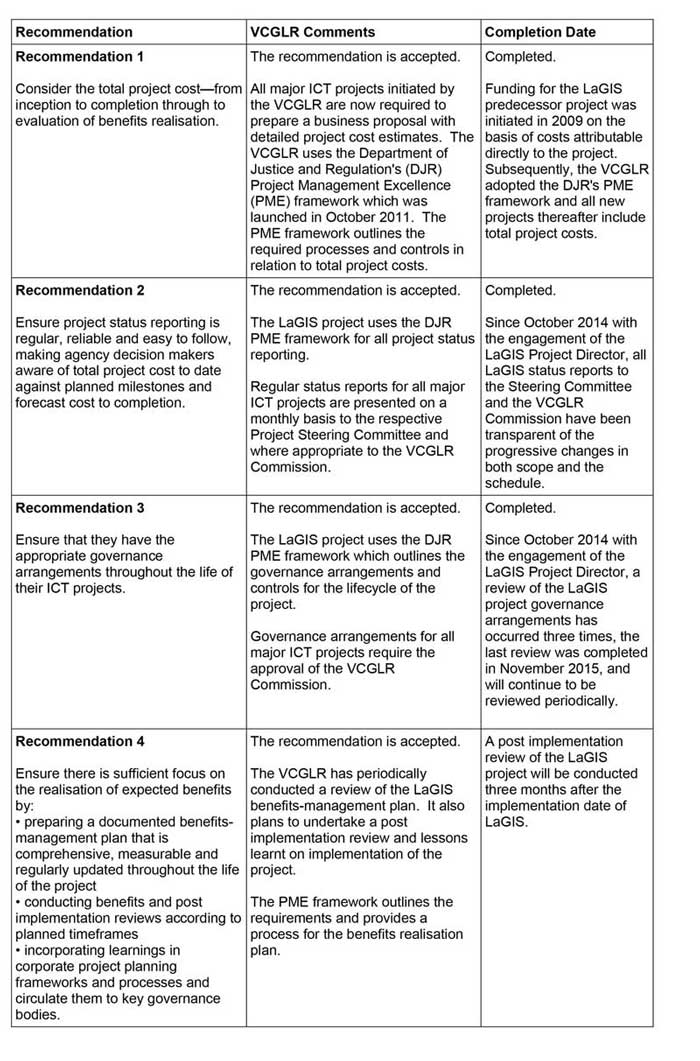

Figure 2A

Actual versus planned cost of selected ICT projects

|

Project |

Project status |

Initially planned cost ($ million) |

Actual cost ($ million) |

Expected final cost ($ million) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

City West Water—Arrow Program |

In progress |

106 |

63.2 as at Dec 2015 |

122 |

|

Department of Justice & Regulation —Infringement Management and Enforcement System Project(a) |

Terminated |

24.9 |

59.9 |

Terminated |

|

University of Melbourne—ISIS Student Management System Project(b) |

Completed |

23 |

30 |

Completed |

|

Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation—Liquor and Gambling Information System Project(c) |

In progress |

14.1 |

11.61 as at Nov 2015 |

14.1 De-scoped |

|

WorkSafe—Electronic Document and Records Management System Project(c) |

Completed |

33.6 |

25.4 |

Completed, |

|

Yarra Valley Water—Improving Infrastructure Management System Program(d) |

Completed |

17 |

26 |

Completed |

(a) The Department of Justice & Regulation advised that the $59.9 million actual cost is comprised of $35.8 million in project costs and $24 million in vendor costs.

(b) Since 2011, additional funding of up to $7.65 million has been spent to address post-implementation issues, enhance user experience and enable further business change.

(c) These projects have been de-scoped and will not deliver all initially intended functionality.

(d) The original June 2011 budget estimate was $17 million. Following the procurement process, it was determined that Yarra Valley Water had underestimated the cost, and board approval was obtained for $23 million for the project.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

2.3.1 Findings on cost by agency

City West Water—Arrow Program

While still within budget, City West Water's (CWW) project is a long way from completion. The project has been staged by three releases:

- release one—financials

- release two—asset management

- release three—customer billing.

To date, CWW has completed release one, which was delivered on budget. At the time of the audit, however, release two was proving more difficult to complete.

Following the design phase, release two was found to require a far costlier and higher level of system customisation than assumed in the business case. At the time of the audit, CWW was working with the vendor and systems integrator to simplify the system design based on the latest version of the vendor's product as well as an alternative product that was not available during the planning phase.

Release three has not yet commenced. CWW's review of the planned cost and time for this phase of the program indicates a likely cost increase of $6.5 million. CWW advised that this is based on its experience of the program to date, as well as that of another water corporation who recently implemented a new customer billing system.

The expected final cost for the program is $122 million, which is $16 million or 15 per cent over the $106 million initial cost. CWW maintains that the expected additional cost requirement can be funded from the program's 15 per cent contingency budget.

Department of Justice & Regulation—Infringement Management and Enforcement System Project

To address inadequacies in its existing infringement management and enforcement system, the Department of Justice & Regulation (DJR) entered into a contract with a vendor in 2007 to build a new Infringement Management and Enforcement System (IMES). The project was initially budgeted at $24.9 million, with delivery of the new system due by October 2009.

DJR documentation shows that the $24.9 million budget refers to the fixed contract cost payable to the vendor. Other costs relative to project delivery, such as staff cost, training and consultants' fees, were not considered in the planning phase and do not form part of the reported initial project budget. In future, DJR should consider total project cost—from inception to completion through to evaluation of benefits realisation— when determining the project budget.

Following significant project delays and ongoing performance issues with the contractor, the government terminated the project in March 2015.

The $59.9 million actual project cost at termination was over twice the planned cost.

The delays and ultimate cancellation of the project mean that DJR has no choice but to use a dated legacy system. Moreover, proposed legislative reforms that are dependent on DJR's delivery and deployment of the new system have been postponed. The implications of these two issues are outlined below.

Continued reliance on a legacy system

DJR continues to rely on a legacy system, which, as early as 2006, was found by DJR to be incapable of meeting user requirements due to its limited reporting functionality and its inability to implement service change management and productivity improvements.

According to the 2006 IMES business case, 'extensive changes are required to effectively comply with the business processes specified in more than 50 pieces of legislation'.

The cost of keeping the existing system up to date is significant. A 2014 DJR‑commissioned review further found that the legacy system infrastructure is aged and showing signs of declining performance and occasional failure.

DJR documentation reveals that business continuity and disaster recovery arrangements to support the legacy system are inadequate, such that in the event of a major failure of core infrastructure, it is unlikely that the legacy system could be recovered within an appropriate time frame. DJR documentation likewise reveals that its legacy system has significant security vulnerabilities and should be more appropriately managed.

Delay in the commencement of the Fines Reform Act 2014

The Fines Reform Act 2014 introduced changes to the collection and enforcement of fines in Victoria. The new IMES was intended to support amendments introduced by the Act to enhance debt collection. For example, by enabling outstanding fines and court orders to be bundled as one debtor account, instead of requiring the enforcement of each warrant separately where an individual has multiple warrants.

The Act was scheduled to take effect on 1 July 2016. This was premised on DJR’s delivery and deployment of the new IMES prior to this time. As a result of the problems with the IMES build, commencement of the Act has been delayed to a future date

University of Melbourne—ISIS Student Management System Project

UoM planned to implement its student management system, ISIS, in 2008 at a cost of $23 million. UoM advised that in order to tightly manage costs, it chose not to allocate a contingency for the project. Following a two-year delay, the total cost of implementation in 2010 was $30 million. A significant portion of the $7 million in increased costs reflects extended project team costs as well as additional expenses for remedial work on the legacy system.

UoM documentation acknowledges that, while the system worked when installed in 2011, there were issues with its usability. According to the UoM-commissioned post-implementation review, 'in the post go live period, there has been a rocky period of stabilisation activity. The system hasn't fallen over, but there has [sic] been significant reinforcements needed in the form of additional labour, some reversion to manual practices, gaps in management information/reporting and large draw-downs on goodwill across the University of Melbourne (UoM) community.'

Since 2011, UoM has undertaken further project work to address deficiencies, to achieve the expected benefits from ISIS, to enhance user experience and to enable further business change. This further project work has cost $7.65 million (as at September 2015) in addition to the $30 million.

Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation—Liquor and Gambling Information System Project

The Liquor and Gambling Information System (LaGIS) project is still in progress.

The Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation (VCGLR) entered into a contract with the vendor in July 2013 for the delivery of the LaGIS system in June 2014. Following significant delays in project implementation, VCGLR entered into a second revised deed with the vendor in July 2015, which saw the scope of the project significantly reduced and a revised delivery date of October 2015. VCGLR advised that this milestone has not been met and that the new expected date of implementation is April 2016.

VCGLR estimates that its initially approved project budget of $14.1 million will be exhausted by April 2016 and that additional funds will be required if the project continues beyond this date.

WorkSafe Victoria—Electronic Document and Records Management System Project

The WorkSafe Victoria Electronic Document and Records Management System (EDRMS) Project was approved in 2012 with a budget of $33.6 million spanning five phases.

Phase one costs increased beyond initial estimates, as the underlying information technology (IT) infrastructure (server platforms, databases, etc.) required major upgrades. Associated delays and cost overruns prompted WorkSafe Victoria to commission an independent review of the project in 2014.

The review found that simplifying the design and development of the system would reduce costs by removing the need to deliver complex workflows. Consequently, some functionality was removed from the initial project scope, e.g. automated account entry. The project budget was correspondingly reduced to $25.4 million. At project completion in December 2015, actual project cost was $25.4 million.

WorkSafe Victoria advised that it found the review process useful and, for future projects, will continually assess options for improved functionality.

Yarra Valley Water—Improving Infrastructure Management System Program

The original budget estimate for the YVW Improving Infrastructure Management System (I2MS) program was $17 million. The managing director advised the board of this initial estimate on 23 June 2011. The board noted the estimated costs, but no approval was sought or given.

The program included a number of component projects. A replacement asset management system (AMS) was the largest and final component of the program, originally estimated to cost $6.8 million.

Following the procurement process for the AMS project, YVW determined that it had underestimated the costs of the AMS component of the program. YVW remained committed to completing the project, as the business case continued to support the intended benefits of the overall I2MS program.

Consequently, board approval was obtained for $23 million for the project in 2012. An additional amount of $3.07 million was approved by the board in 2014.

Accordingly, the actual project cost of the whole I2MS Program at completion was $26 million, 53 per cent more than the initial 2011 estimated cost, and 12 per cent more than the revised 2012 budget.

2.3.2 Transparency of ICT expenditure

The method and process by which agencies monitor and report on project costs should be improved for greater transparency and reliability.

While agencies periodically provide project cost reports to their steering committees and boards/senior management, the audit team found that these are often confusing and difficult to track against baseline milestones. Costs are usually indicated for a period of time or a particular project component, without giving a full account of the total running cost for the whole project.

More comprehensive reporting on costs would assist agency decision-makers to better appreciate the full extent of project expenditure and, as a result, to better assess the actual business value of the ICT investment.

Tracking full project costs

This audit confirms findings from Digital Dashboard: Status Review of ICT Projects and Initiatives – Phase 1 that agencies are not tracking complete project costs and that there is no consistent method of capturing actual total costs.

For the six projects examined in this audit, the agencies' default position has been to monitor only those costs which are directly attributable to the project, while other costs incurred across the various business units are not captured.

This practice appears to relate directly to the way the business case was prepared—i.e. agencies only monitor the planned costs that are itemised in the business case. For example, vendor, hardware and project delivery costs, when indicated in the business case budget, are monitored through the life of the project. However, staff costs outside the project team, training, consultancy and other costs incurred in project implementation are not necessarily tracked if these have not been specified in the business case budget.

To determine the true value of government investment in ICT projects, agencies need to carefully plan beyond the obvious vendor and project team costs. They should consider all project costs—from planning through to evaluation and reporting of project benefits, including internal staff costs, training and other costs associated with preparing the business for the transformational effect of the project.

As an example, post project termination, DJR estimated the total project cost, including in-house staff costs. While this attempt to quantify actual staff cost at project termination is laudable, systematically tracking it during the life of the project—including when planning the initial budget—is preferable. DJR advised that new methodologies in place across the department should be able to fully account for actual project costs.

Contingency funding

Contingency funding should generally cater for unexpected future events that may impact on the cost of the project. The 2013 report Own motion investigation into ICT‑enabled projects, by the Victorian Ombudsman in consultation with the Victorian Auditor General's Office, identified issues in the use of contingency funding, with agencies treating contingency funds as approved funding to be spent freely.

This audit found inconsistency in the use of contingency funding across the audited agencies. We noted discrepancies in the extent of contingency funding allocated, ranging from zero to 30 per cent of project costs. Moreover, while some project budgets included contingency funding as a line item, some considered it as an add-on to the approved budget.

2.4 Actual versus planned time

Of the projects examined in this audit, only YVW's I2MS Program was completed as initially scheduled. The remaining five projects have faced significant challenges at various points during implementation.

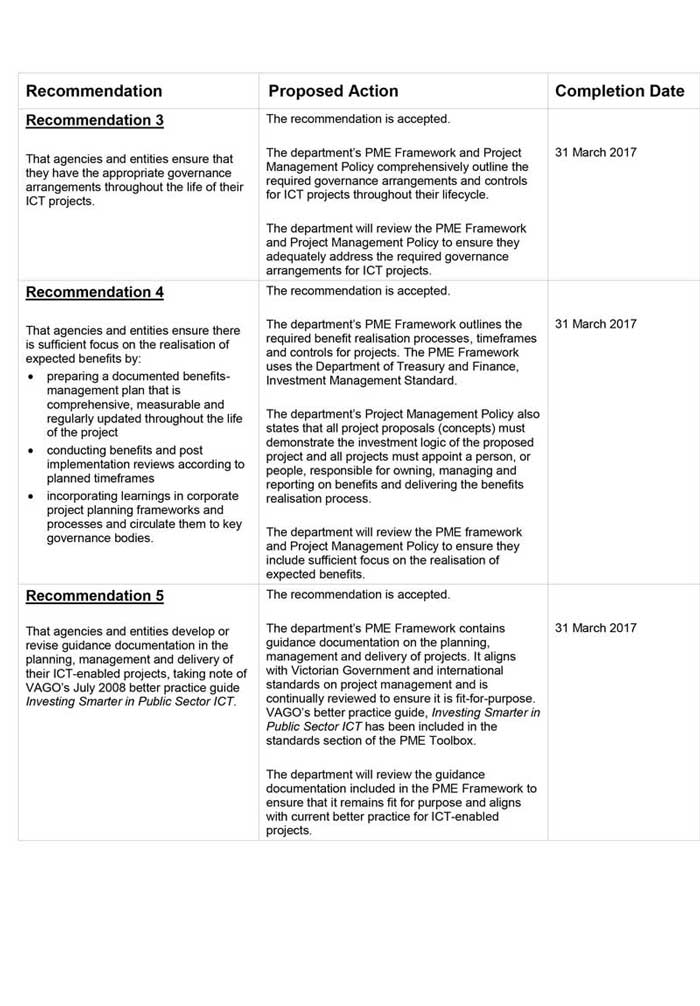

Figure 2B

Actual versus planned time of selected ICT projects

|

Project |

Project status |

Planned completion date |

Actual or expected completion date |

|---|---|---|---|

|

City West Water—Arrow Program |

In progress |

March 2016 |

Oct 2019 |

|

Department of Justice & Regulation—Infringement Management and Enforcement System Project |

Terminated |

August 2009 |

March 2015 (termination date) |

|

University of Melbourne—ISIS Student Management System Project |

Completed |

June 2008 |

June 2010 |

|

Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation—Liquor and Gambling Information System Project |

In progress |

June 2014 |

April 2016 |

|

Worksafe—Electronic Document and Records Management System Project |

Completed |

June 2015 |

December 2015 |

|

Yarra Valley Water—Improving Infrastructure Management System Program |

Completed |

November 2014 |

November 2014 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

2.4.1 Findings on time by agency

City West Water—Arrow Program

CWW delivered release one (financials) on time. However, it has since experienced problems with the design and build of release two (asset management)—the scheduled implementation date for this release was March 2014, but the design phase was only completed in October 2015. After delays in simplifying the design, the build phase for this release is progressing.

While work on release three (customer billing) is yet to commence, its estimated implementation time line has been extended from 12 to 36 months. Following problems encountered with release two, the Minister for Water requested CWW to prepare a revised business case for approval before progressing with release three.

The business case for the Arrow Program required the Treasurer's approval, as the proposed capital expenditure was greater than $50 million. This was consistent with the Department of Treasury & Finance's 2009 publication Corporate planning and performance reporting requirements – Government Business Enterprises.

Department of Justice & Regulation—Infringement Management and Enforcement System Project

DJR documentation shows that shortly after the execution of the contract in 2007, the vendor advised DJR that it needed more time to clarify the requirements for the IMES build and that this would delay the project. It also advised that the task of clarifying business requirements was beyond the scope of the original cost. The vendor claimed nearly $60 million for work done.

As indicated in Figure 2C, DJR and the vendor agreed to a number of contract variations prior to the termination of the project in March 2015. However, DJR documentation indicates that the vendor was unable to meet the revised and agreed time lines.

The decision to terminate the project was made nearly six years after its initial planned completion date of August 2009. As indicated in Section 2.3.1, the final actual project cost was reported by DJR at $59.9 million, comprising $35.8 million in project delivery costs and $24 million in vendor costs.

Figure 2C

Time line of contract variations for the Department of Justice & Regulation's IMES Project

|

Date of variation |

Description of events |

|---|---|

|

Original contract —July 2007 |

This agreement required the vendor to clarify and document detailed requirements for the IMES build. Scheduled system deployment was set for August 2009. |

|

Amending Agreement 1 —June 2009 |

Early in 2008, the vendor advised DJR that it needed more time to clarify the requirements for the IMES build and that completing this would delay the project. The vendor also advised that clarifying the requirements was beyond the initial scope and would attract additional costs. By June 2009, the vendor was claiming nearly $60 million for work done that was out of scope. Following negotiations, Amending Agreement 1 was signed, requiring the vendor to deploy the system by September 2010 and authorising additional payment to the vendor of $19.7 million for additional work. |

|

Amending Agreement 2 June 2012 |

The vendor failed to build and deploy the IMES in September 2010, as agreed in Amending Agreement 1. DJR received legal advice that despite the vendor's failure to deliver the system build, it was unable to terminate the contract without affecting the vendor's existing obligations to manage the legacy system. On 29 June 2012, Amending Agreement 2 was signed, extending deployment to August 2013 and authorising additional payment to the vendor of $6.4 million for additional system functionality. This brought total contract cost to $52 million. In February 2013, the vendor advised DJR that it expected further delays in the delivery of the system and anticipated a revised deployment date of November 2013. With the vendor failing to deliver system build and deployment time after time, DJR commissioned an independent auditor in September 2014 to determine whether the vendor had the capability to complete the project. The external auditor reported that, by the second quarter of 2014, the vendor had significantly reduced its project team and was no longer planning to do further work on the system build. According to DJR documentation, the vendor decided that it was not in its financial interest to complete the project. Given this, DJR had little choice but to recommend the cancellation of the project. A legal settlement between the parties was reached in March 2015. |

|

Deed of Settlement —13 March 2015 |

Government approved the termination of the IMES build project. |

Note: DJR advised that final actual cost for the project was $59.9 million, comprising of $35.8 million for project delivery costs and $24 million in vendor cost.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

University of Melbourne—ISIS Student Management System Project

In November 2006, UoM signed a contract with the vendor to implement its student management system. The initial go-live date was June 2008.

Documentation provided by UoM indicates that it experienced performance issues with the vendor throughout the project, mainly around software quality and failure to deliver as scheduled. According to UoM documentation, the project go-live was first delayed from June to September 2008, but the continued inability of the vendor to deliver the required software quality left UoM little choice but to call off the September go-live.

Given the serious threat of project failure, the project director and senior responsible owner, together with other key UoM officers, met with the vendor's chief executive officer to discuss the issues. UoM also engaged an external project auditor, legal advisor and due diligence consultant to assess its position and consider its options.

A deed of variation was executed in June 2008 which agreed on a go‑live date of June 2010, a greater level of engagement from the vendor, an implementation plan to be developed and agreed within 14 days, and an arrangement to second UoM staff to work with the vendor over the next nine months.

With the project team's consistent engagement with the vendor and monitoring of project progress, ISIS went live in line with the revised schedule in June 2010. It was not a smooth implementation, with some functionality only partially delivered and some other functionality scheduled for implementation post-go-live. Nonetheless, the legacy system was successfully decommissioned shortly after the project went live.

Since 2011, UoM has followed up with further project work to address deficiencies, to achieve the expected benefits from ISIS, to enhance user experience and to enable further business change.

Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation—Liquor and Gambling Information System Project

The LaGIS Project has experienced significant delays and is now expected to be completed two years after its initial planned implementation date of June 2014.

VCGLR documentation attributes the delay to the unrealistic schedule set out by the vendor, which was developed without a full appreciation of the requirements of the project, including the breadth of the required functionality and the volume and complexity of data sources that needed to be migrated to the new system.

VCGLR's efforts to hold regular meetings with the vendor—including attendance by the VCGLR chair—did not result in meeting project milestones. A deed of variation was signed with the vendor in December 2014 to reflect the revised two-phase implementation milestones in July and December 2015.

A month later, in January 2015, the vendor proposed further dividing phase one into two releases, for July 2015 and January 2016. VCGLR agreed to this proposal, but no date was agreed for phase two.

Another deed of variation was executed in July 2015, limiting the project scope to the first release of phase one—effectively 25 per cent of the original project scope—by October 2015.

VCGLR has the option to proceed with additional releases of the system. VCGLR has advised that this will allow it to investigate alternative solution providers for the remaining functionality or to continue with the current vendor.

VCGLR documentation shows that it considered the vendor in material breach of the contract when the vendor did not meet a major contractual milestone by October 2015. Following discussions with the vendor, VCGLR has decided to continue with the implementation of release one of phase one but it reserves its right to terminate the contract at any time.

WorkSafe Victoria—Electronic Document and Records Management System Project

The EDRMS Project has also experienced delays. The whole project, consisting of five phases, was expected to be completed in June 2015, but a revised and de-scoped phase one was subsequently completed in December 2015. Progress on the remaining portions of the initially approved project scope will be subject to WorkSafe Victoria preparing a new business case for approval by the board.

Yarra Valley Water—Improving Infrastructure Management System Program

While the go-live date of the project's AMS component was delayed by two months, YVW met the actual project end date and the overall project was delivered on time. This is the only project examined in this audit that was delivered on schedule.

2.4.2 Transparency of information

All agencies provided progress reports to senior management or the board. However this information was not always presented with an identifiable baseline from which to track performance against initially approved project milestones. As a result, cost and schedule over-runs were not readily apparent.

In the WorkSafe Victoria and VCGLR projects, time lines were revised ('re-baselined') on several occasions when initial deadlines were not met. Once time lines are re-baselined, the project status turns from 'delayed' (red) to 'on track' (green). As new time lines replace the previous ones, it becomes difficult to determine how the project is performing against the initially approved time lines. This is particularly problematic when there are changes in the board or committee membership.

When time lines or budgets are revised, agencies should ensure that information provided to steering committees and/or the board clearly and transparently reflects all progressive changes throughout the life of the project.

2.5 Elements of better practice

Yarra Valley Water—Improving Infrastructure Management System Program

In the case of YVW, factors contributing to the timely implementation of the project included:

- clearly articulated business requirements

- appointment of appropriately skilled resources in the project team and systems integrator

- an effective data migration strategy, which regularly updated data from existing systems, allowing early identification of errors and minimising delays prior to go‑live

- thorough testing of the AMS prior to go-live.

University of Melbourne—ISIS Student Management System Project

UoM's ISIS project was delivered two years behind schedule, at $7 million or 30 per cent more than the initially approved budget. UoM documentation indicates that the delay and cost overrun were due to issues with vendor delivery. UoM should be commended for its consistent and tenacious monitoring of the vendor's progress to deliver the system, and its appointment of a skilled and tested project manager, sponsor and team. The robust involvement of UoM senior management in managing the relationship with the vendor also supported the eventual project implementation.

Recommendations

That agencies and entities:

- consider the total project cost—from inception to completion through to evaluation of benefits realisation

- ensure project status reporting is regular, reliable and easy to follow, making agency decision-makers aware of total project cost to date against planned milestones and forecast cost to completion.

3 Governance and benefits realisation

At a glance

Background

Appropriate governance arrangements play an important role in the effective implementation of ICT projects and their ability to deliver intended benefits.

Conclusion

By themselves, the defined governance arrangements in the six examined ICT projects could not guarantee successful implementation. The involvement of senior management in actively engaging with the vendor, particularly when there are vendor performance concerns, is critical to project implementation.

Three of the projects examined have been completed. Two of these have benefits-management plans and will be in a position to report on the realisation of intended benefits at a later stage.

Findings

- All six agencies had defined and formalised governance arrangements in place for their ICT projects. However, these arrangements did not prevent other project management issues from adversely affecting the effective planning and implementation of ICT projects.

- Of the three completed projects, two have benefits-realisation plans in place against which to measure project effectiveness at a later date. One did not have a plan in place and will be unable to report on the achievement of intended benefits.

Recommendations

That agencies and entities:

- ensure that appropriate governance arrangements are in place throughout the life of their ICT projects

- focus on the realisation of expected benefits from project commencement.

3.1 Introduction

Appropriate governance arrangements play an important role in the effective planning and implementation of information and communications technology (ICT) projects. They set the framework for transparent and confident decision-making, clarify roles and responsibilities and assist in considering stakeholder interests.

Government investments in ICT projects are intended to realise identified benefits. It is important to develop a benefits-realisation plan at project commencement to allow project managers to track, evaluate and report on the delivery of identified benefits. Parliament and the Victorian community require assurance that the investment of public funds has resulted in public value.

3.2 Conclusion

While clearly defined governance arrangements do not necessarily guarantee a successful ICT project, agencies should work on developing a robust culture of active governance at the senior management level. Moreover, technical ICT competence needs to be enhanced so that agencies can have sufficient expertise to make decisions and to effectively liaise with consultants and vendors.

Agencies need to better embed the process of identifying intended benefits and reporting on ICT project achievements. Three of the projects examined have been completed. Two of these have benefits-management plans in place and will be in a position to report on benefits realisation at a later stage.

3.3 Governance arrangements

Appropriate governance arrangements throughout the life of an ICT project are important for:

- enabling informed decision-making by the senior responsible owner and steering committee which had oversight of the project

- developing and documenting the business requirements for the proposed ICT system and understanding the current ICT infrastructure and its capability

- identifying, assessing, communicating, mitigating and addressing risks thoroughly and prudently

- focusing on change management activities, including sufficient training and communication, to prepare users for the change.

Active engagement by agencies' senior management with the vendor, particularly when there are vendor performance issues, is also critical to successful project implementation.

All six agencies had defined and formalised governance arrangements in place for their ICT projects.

Figure 3A

Governance arrangements in place for selected ICT projects

|

Project |

Governance arrangements |

|---|---|

|

City West Water (CWW)—Arrow Program |

|

|

Department of Justice & Regulation (DJR)—Infringement Management and Enforcement System (IMES) Project |

|

|

University of Melbourne (UoM)—ISIS Student Management System Project |

|

|

WorkSafe Victoria—Electronic Document and Records Management System Project |

|

|

Yarra Valley Water (YVW)—Improving Infrastructure Management System Program |

|

|

Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation (VCGLR)— Liquor and Gambling Information System Project |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation—Liquor and Gambling Information System Project

At VCGLR, the governance arrangements initially caused confusion about who was responsible for enforcing vendor performance.

VCGLR commenced operations as an independent statutory authority that regulates Victoria's gambling and liquor industries in February 2012. Previously, liquor and gambling were administered and regulated by two independent bodies—the Director of Liquor Licensing and Responsible Alcohol Victoria (RAV) and the Victorian Commission for Gambling Regulation. This amalgamation led to complex governance arrangements for the Liquor and Gambling Information System (LaGIS) Project.

The original project commenced under RAV and comprised a suite of integrated systems, which was to be called Victoria's Alcohol Regulation Information System or VARIS. A business case was approved by the project steering committee in 2009. Following the amalgamation, VARIS was reinitiated as LaGIS and scoped to provide VCGLR with an IT solution that would support the management of the consolidated alcohol and gaming licensing, compliance and secretariat operations.

As a result of the historical arrangements, VCGLR is the project owner but DJR is responsible for the administration and management of the project through its Major Procurement Program Office. Funding for the project sits with DJR, although some funds were vested to VCGLR for payments to the vendor.

The costs associated with the build and implementation come from the VCGLR budget (as project owner), however, funds are vested to them by DJR in line with periodic payments to the vendor and external consultants that are due.

As a result of this arrangement, costs are not fully transparent to VCGLR, despite it being accountable for the project. Moreover, the responsibility and accountability was diffused across two governance bodies—the project control group and the project steering committee. There was no clarity on the roles and responsibilities, which resulted in some confusion about who was responsible for managing vendor performance.

VCGLR has since addressed this issue, clarifying roles and responsibilities. In addition to the project governance framework, monthly meetings are held between the VCGLR chief executive officer, the project director and the vendor's managing director to monitor the overall status of the contract.

3.3.1 Requisite ICT and technical skill set

Agencies must have the technical skill set to effectively plan and implement the project. A lack of ICT and commercial acumen often contribute to poor ICT outcomes.

Department of Justice & Regulation—Infringement Management and Enforcement System Project

DJR acknowledges that it was far from being an informed buyer and that it relied on external legal advice to outsource the risks associated with the bespoke IMES ICT build by:

- tightly binding the purchase with a service contract, which prevented DJR from having any direct relationship with any technical provider engaged by the service provider

- having a fixed-price contract

- assigning responsibility for the development of the system business requirements to the vendor.

DJR did not engage appropriately skilled technical people who could have guided it through the challenges of procuring a bespoke ICT system. DJR had inadequate technical resources or ICT capability to plan and implement this project. DJR documentation acknowledges that the staff involved in the procurement of the system build focused on achieving 'best pricing' and meeting procurement obligations and the related legal considerations. The technical ICT components required for appropriate planning did not receive sufficient attention from DJR.

DJR documentation acknowledges that the steering committee likewise lacked independent ICT advice, relying solely on that provided by the project management team. DJR says it was 'probable' that the steering committee lacked suitably skilled and experienced staff for the type of project being embarked upon.

3.3.2 Advice provided to senior management

Key decision-makers require access to independent specialist advice and guidance in order to make informed decisions.

Although governance arrangements at all six agencies were supported by project status reporting, issues with the quality and transparency of information and advice provided to senior management or the board were identified.

As indicated in Section 2.4.3, cost and time line revisions (or re-baselining) throughout the life of the project should be clearly indicated in status reports provided to senior management or steering committees, to give them a clear picture of how the project is tracking against initially approved budgets and time lines.

Department of Justice & Regulation—Infringement Management and Enforcement System Project

In the case of DJR, business case documentation provided to the steering committee did not include sufficient content to properly inform decision-making. This means that the steering committee considered and recommended for approval a business case that did not clearly articulate the specifics of the IMES that it was planning for.

The business case was written by DJR's Major Projects division with minimal consultation with the Infringement Management and Enforcement Services division. As a result, it did not articulate the specific IT requirements for the development of the IMES.

Instead of clearly assessing and articulating the IMES requirements to address the identified business need, the business case was prepared primarily for procedural purposes, i.e. to facilitate approval.

DJR documentation also reveals that a critical issue relating to the two tender bids received was not brought to the attention of the steering committee. The chosen vendor's bid was significantly lower than the other tenderer, and the project team recommended its acceptance without advising the steering committee that no analysis was undertaken to determine whether such a low bid price was reasonable for the proposed ICT system build.

The 2007 agreement required the vendor to specify and document detailed requirements for the IMES build. When seeking approval for the contract, DJR did not advise the steering committee on the risks that came with this arrangement, including:

- not really knowing what the resulting system would be like and that it may result in the development of a system that would not meet DJR's requirements

- increased costs as a result of giving the contractor the liberty to specify system functionality.

DJR acknowledges that the steering committee did not receive independent ICT advice and relied solely on information provided by the project management team.

3.3.3 Business requirements

It is essential for agencies to accurately identify business requirements prior to system development. In its technical guidance Developing ICT Investments, the Department of Treasury & Finance (DTF) advises agencies to commission an independent check of the specification and requirements, to make sure the solution is both affordable and technically feasible. However, we found deficiencies in this area at several agencies.

City West Water—Arrow Program

CWW undertook an 'enterprise design' phase from September 2011 to April 2012 in order to develop the requirements and high-level business process design for the Arrow Program, at a cost of $13 million.

In 2014, CWW engaged a systems integrator to develop release two (asset management), based on two modules procured from the vendor. During this phase it was acknowledged that the design was too complex and could not be implemented within the planned budget. Following completion of release one, a number of issues were identified that required it to be redesigned in order to integrate with release two.

CWW has worked with both the vendor and the systems integrator to simplify the design of release two to meet its requirements and deliver business benefits, within the remaining approved budget.

Despite CWW's significant multimillion-dollar investment in planning, it failed to identify the complexity involved in implementing the procured solution.

Department of Justice & Regulation—Infringement Management and Enforcement System Project

DJR acknowledges that it was 'out of its depth' when planning for the IMES build.

As discussed in Section 3.3.2, although DJR engaged commercial and legal experts during the procurement process for IMES, it did not engage appropriately skilled ICT people to detail the system requirements for the ICT build. This critical planning component was, in fact, passed on to the vendor by DJR.

WorkSafe Victoria—Electronic Document and Records Management System Project

Although WorkSafe Victoria documented its business requirements, an external review of the Electronic Document and Records Management System (EDRMS) in 2014 found that it was possible to simplify business processes, thereby significantly reducing the original requirements while delivering the majority of the business benefits. This review recommended re-scoping the project to simplify workflows and reduce costs.

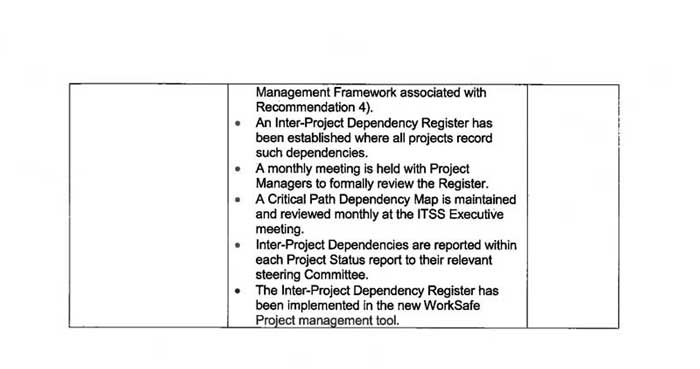

While WorkSafe Victoria identified and addressed project dependencies during the planning phase, this was eventually found insufficient to mitigate the IT infrastructure problems that presented during project implementation in 2013. This significantly impacted project time lines, as the required infrastructure changes were made prior to continuing with project implementation.

In future, WorkSafe Victoria should ensure that its project dependency planning is more comprehensive and involves more extensive testing.

3.3.4 Vendor capability

During procurement, agencies must be informed buyers and assess whether the market is equipped to meet their specifications. Agencies require the skills to assess the competence of vendors or contractors who may overstate their ability.

In two instances, agencies purchased commercial off-the-shelf solutions—i.e. a product that doesn’t require custom development before installation—where the vendors have not yet implemented the software in the form required. As such, these were still undeveloped and untested products.

Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation—Liquor and Gambling Information System Project

During the tender evaluation for the LaGIS Project, DJR relied on references from the vendor's existing clients, even though these clients' projects were only in the planning phase. Further, neither of these existing clients required the software to be implemented to the extent required by VCGLR—the existing clients only procured component modules rather than the whole solution. As such, it was an unproven product, but these issues were not identified during the tender evaluation.

University of Melbourne—ISIS Student Management System Project

UoM's procurement process identified a limited choice of vendors that could provide a system to satisfy its requirements. The successful vendor had implemented student management systems at several other Australian universities, however, these were significantly smaller and less complex implementations. UoM documentation shows that it recognised the risk of vendor non-delivery, but determined that proceeding with the vendor was the best available option.

While UoM acknowledged during planning that its implementation would be more complex than those of the existing institutions, a post-implementation review commissioned by UoM in March 2011 found that planning could have been improved.

The post-implementation review noted the following as key lessons that UoM should consider for future similar projects:

- 'Build into the evaluation and selection process that, when sourcing new software that it is better to 'do nothing' than pick the best product of a bad lot if it won't "cut the mustard" [sic].'

- 'Do full due diligence on the vendor, their software and its response time performance with other customers.'

- 'Ensure the vendor can operate as a tier 1 vendor [i.e. one of the largest and most well-known in its field—often enjoying national or international recognition and acceptance], and service tier 1 needs.'

UoM put its governance to good use by promptly escalating the issue to the UoM Council and proactively engaging with the chief executive officer of the vendor to rectify the problems. UoM also set stringent testing requirements prior to making a decision to go live with the system.

3.4 Benefits realisation

In order to understand the value of an ICT investment, intended benefits need to be effectively identified, monitored and reported.

3.4.1 Benefits-realisation plan

A benefits-realisation plan should be prepared at project commencement to allow project managers to track, evaluate and report on the delivery of identified benefits. Figure 3B shows which projects are supported by a benefits-realisation plan and project evaluation.

Figure 3B

Documented benefits-realisation plans for selected ICT projects

|

Project |

Benefits-realisation plan |

Project evaluation |

|---|---|---|

|

City West Water—Arrow Program |

Yes |

N/A—project in progress |

|

Department of Justice & Regulation—Infringement Management and Enforcement System Project |

Yes |

Project terminated (project closure report completed) |

|

University of Melbourne—ISIS Student Management System Project |

No |

Not undertaken |

|

Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation—Liquor and Gambling Information System Project |

Yes |

N/A—project in progress |

|

WorkSafe Victoria—Electronic Document and Records Management System Project |

Yes |

Plan under review following de-scoping of the project |

|

Yarra Valley Water—Improving Infrastructure Management System Program |

Yes |

Underway |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

To date, only UoM, WorkSafe Victoria and YVW have completed their projects.

Of the audited projects, UoM is the only agency that did not document a benefits-realisation plan as part of its project methodology. UoM advised that benefits realisation was not a standard part of its project methodology when planning the project in 2005 but that it is now a standard part of their planning activities.

There is anecdotal evidence that the functionality of UoM's ISIS system and user satisfaction have both improved. However, because there was no formal benefits-realisation framework put in place, benefits have not been identified, measured or monitored. Because UoM is unable to demonstrate realised benefits, it cannot give assurance that the project was a sound investment.

WorkSafe Victoria does not intend to start analysing benefits realisation until it has completed phase 2 of the EDRMS project.

YVW advised that it will start a formal benefits review in 2016.

3.4.2 Delivery of planned project scope

During the course of a project, the originally planned project scope may be decreased in order to meet budget or schedule deadlines. This can impact on the realisation of intended benefits. Figure 3C shows whether each project's intended scope has been or will be delivered.

Figure 3C

Delivery of intended scope for selected ICT projects

|

Project |

Project status |

Originally intended scope was or will be delivered |

|---|---|---|

|

City West Water—Arrow Program |

In progress |

✔ |

|

Department of Justice & Regulation—Infringement Management and Enforcement System Project |

Terminated/cancelled |

N/A—terminated |

|

University of Melbourne—ISIS Student Management System Project |

Completed |

✔ |

|

Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation—Liquor and Gambling Information System Project |

In progress |

✘ |

|

WorkSafe Victoria—Electronic Document and Records Management System Project |

Completed |

✘ |

|

Yarra Valley Water—Improving Infrastructure Management System Program |

Completed |

Not clear |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

At WorkSafe Victoria and VCGLR, the intended project scope was revised in order to meet budget and/or delivery time lines.

University of Melbourne—ISIS Student Management System Project

The ISIS system did not undergo formal de-scoping in the course of the project. Although there was functionality that was not able to be delivered at go-live in 2010, UoM has made significant effort to address this. At the time of the audit, enhancements and improvement activities continued to be implemented and the previously intended functionalities have been delivered.

Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation—Liquor and Gambling Information System Project

Due to ongoing performance issues with the vendor, VCGLR has significantly decreased the scope of the original project. It decided to continue with the implementation of release one of phase one but reserves its right to terminate the contract at any time. If successfully implemented, release one will deliver approximately 25 per cent of the original scope. VCGLR is currently assessing its options on how best to deliver the remaining project scope.

WorkSafe Victoria—Electronic Document and Records Management System Project

The original business case for WorkSafe Victoria's EDRMS Project was approved in June 2012 and varied in May 2014. A key part of the original scope for phase one was an automated accounts entry function, but it has not been delivered and this task is now carried out manually.

Automated accounts entry was a core business benefit in the original business case, and financial benefits attributable to this function were estimated at $5 million per year, reducing over time. While non-financial benefits are expected to be realised, only a modest financial benefit of $0.35 million per annum is expected under the revised scope.

Yarra Valley Water—Improving Infrastructure Management System Program

YVW did not formally de-scope the I2MS Program. However, as YVW has not yet conducted a post-implementation review to acquit the functionality delivered against the originally intended requirements, it is unable to report the extent to which project scope was delivered.

3.4.3 Post-implementation review conducted

The purpose of a post-implementation review (PIR) is to evaluate how successfully the project objectives have been met and to identify lessons learned that will assist in planning, managing and meeting the objectives of future projects. It is a critical part of the project life cycle and should be conducted between one and six months after a project has been completed.

YVW has not yet conducted a PIR of its project, despite it being one year since go-live. YVW advised that a PIR has been planned for early 2016.

UoM conducted a PIR in March 2011. Relevant project stakeholders were consulted to identify success points, challenges and lessons learned to assist similar future projects.

At the time of the audit, a PIR was underway at WorkSafe Victoria.

Recommendations

That agencies and entities:

- ensure that they have appropriate governance arrangements in place throughout the life of their ICT projects

- ensure there is sufficient focus on the realisation of expected benefits by:

- preparing a documented benefits-management plan that is comprehensive, measurable and regularly updated throughout the life of the project

- conducting benefits and post-implementation reviews according to planned time frames

- incorporating learnings in corporate project planning frameworks and processes and circulating them to key governance bodies.

4 Doing ICT projects better

At a glance

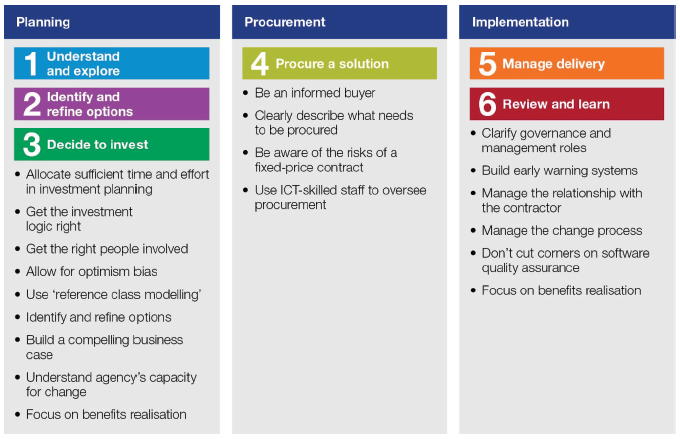

Background

The purpose of this Part is to restate some practices that may assist in the delivery of successful information and communications technology (ICT) projects by public sector agencies and entities.

Conclusion

The challenges faced by agencies included in this audit are not unique. There is opportunity to learn from the experience of other similarly situated agencies, as well as better practice documentation, in an attempt to plan and implement effective ICT projects.

Findings

- VAGO's July 2008 better practice guide Investing Smarter in Public Sector ICT continues to be sound and relevant for today's purposes.

- Key lessons identified include:

- get the right people involved

- get the investment logic right—focus on benefits realisation

- be an informed buyer

- build early warning systems.

Recommendation