Early Intervention Services for Vulnerable Children and Families

Overview

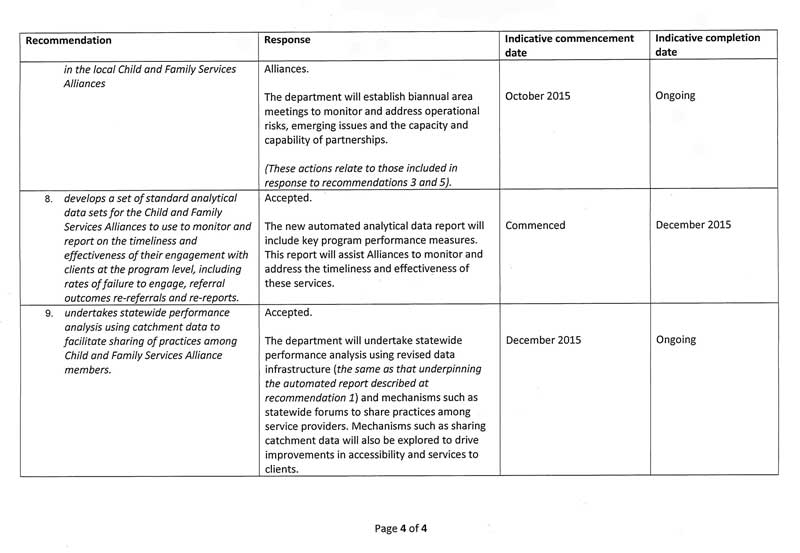

In 2013–14, there were 82 075 reports to child protection in Victoria, a 92 per cent increase since 2008–09. Early intervention is important to prevent ‘at risk’ family situations from escalating.

This audit focused on early intervention services provided through the Child and Family Information, Referral and Support Teams (Child FIRST) and Integrated Family Services (IFS) system. It examined whether families can readily access these services and whether services are leading to positive outcomes for vulnerable families.

The audit found that because of the growing demand and complexity of referrals, Child FIRST and IFS are increasingly providing intervention to high needs families, which means that families with low to medium needs are missing out.

The Department of Health & Human Services needs to improve strategic planning, strengthen partnerships and governance arrangements, and improve communication across local, divisional and central levels of the department and with alliances. It also needs to improve the quality of engagement with service providers, better monitor program risks through routine and systematic data analysis, identify and address key performance issues and measure outcomes.

The audit recommends a comprehensive and urgent whole-of-system review of early intervention, including funding.

Early Intervention Services for Vulnerable Children and Families: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER May 2015

PP No 34, Session 2014–15

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Early Intervention Services for Vulnerable Children and Families.

This audit examined whether vulnerable children and families are able to access the early intervention services provided by Child and Family Information, Referral and Support Teams (Child FIRST) and Integrated Family Services (IFS) and whether the Department of Health & Human Services (the department) can show that outcomes for families have improved as a result of this intervention.

I found that while the department monitors the contractual performance of family service providers, it does not measure the effectiveness of service delivery. It has not established an outcomes framework to assist in measuring the impact on families.

Increased demand for community-based child and family services, and the increased complexity of the cases that are being referred, mean that vulnerable children and families may not always be able to access the services when needed or to maintain engagement with services once these are provided.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

27 May 2015

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Michele Lonsdale—Engagement Leader Fei Wang—Team Leader Melinda Gambrell—Analysts Aina Anisimova—Analysts Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Kristopher Waring |

We have an obligation as a community to protect and nurture our children by doing what we can to give them stable and safe family environments. Unfortunately, not all children have this stability and safety, for the number of children reported to child protection in Victoria has more than doubled in the past seven years—to over 80 000 in 2013–14.

When children and families display early signs that may lead to child abuse or neglect there are intervention services designed to provide them with timely support.

In this audit I looked at whether vulnerable families can readily access early intervention services through the Child and Family Information, Referral and Support Teams (Child FIRST) and Integrated Family Services (IFS) system. I also looked at whether outcomes for these families are improving as a result of this early intervention.

I found that Child FIRST and IFS are struggling to cope with the increased number and complexity of referrals. This means that increasingly these services need to focus on families with high needs rather than those families assessed as low or moderate risk. Yet these are the very families that would benefit most from being able to access early intervention services—when intervention is early enough to prevent escalation.

While the Department of Health & Human Services (the department) requires IFS providers to manage demand, it has not analysed the impact of the strategies that are being used when demand is high. For example, service providers report placing families in longer periods of 'active holding' until a case can be allocated, or spending less time engaging with families than they might do otherwise. The number of 'non-substantive' referrals—those dealt with in less than two hours by Child FIRST—is also higher when demand is high. It is difficult to see how such measures can lead to improved outcomes for children.

Although there are examples of vulnerable children and families being better supported, the department does not know whether the services provided are effectively meeting the needs of vulnerable families. This is because of significant data limitations and a lack of outcomes monitoring at the system level. It is especially concerning that the department does not analyse data relating to the complexity of cases and funding allocations to Child FIRST and IFS providers, and that initially it was not able to provide accurate data on these matters. It is my view that this kind of analysis—and other analysis identified in my report—needs to be done routinely by the department, and naturally supported by accurate data.

We found that community-based service providers are delivering more services than they are funded for by around $5.3 million but the department has not analysed its data to better understand why this has occurred. Are providers 'over performing' because they are efficient or inefficient? Does the system rely too much on the goodwill of providers to meet the costs of service delivery? Are service providers accurately recording hours and cases? Is the funding adequate for the growing level of demand? Without 'follow-the-dollar' powers I was not able to examine how effectively IFS providers are managing the funding they receive to understand the answers to these questions.

The department's introduction of Child and Youth Area Partnerships in May 2014 is a positive step towards achieving a more coordinated approach. However, generally the department has not acted swiftly enough to address the significant impact that a changing external environment has had on the capacity of Child FIRST and IFS to provide early support for struggling families.

The systemic deficiencies that my office has identified suggest that the department needs to undertake a comprehensive and urgent review of its approach to early intervention services, including its whole-of-system funding.

I have made 10 recommendations aimed at improving early intervention support for vulnerable children and families in Victoria. I welcome the department's detailed actions in response to these recommendations and its willingness to engage openly and constructively with the audit team throughout the audit.

I will be following up the department to determine how well it has addressed my recommendations. I note that the findings of my report, and the actions being proposed and undertaken by the department, are likely to be highly relevant to the current Royal Commission on Family Violence and to other departments involved in the delivery of early intervention services.

I want to thank the many service providers involved in Child FIRST and IFS for their valuable contribution to this audit.

This is the second of three audits examining the effectiveness of systems designed to protect children, young people and families. The first, in 2014, reported on residential care services for children. The third—to be tabled in 2016—will assess the effectiveness of diversionary strategies to keep 'at risk' young people from entering the criminal justice system.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

May 2015

Audit Summary

Children and young people are vulnerable when their parents or family have limited capacity to effectively care for them, protect them and provide for their long-term development and wellbeing. That capacity can be affected by a range of factors such as alcohol or substance abuse, family violence, mental health issues, disability, isolation, financial stress, homelessness or bereavement.

In Victoria, the number of children reported to the Victorian Child Protection Service (Child Protection) has increased significantly in recent years. In 2013–14, there were 82 075 reports made to Child Protection. This represents an increase of 92 per cent since 2008–09.

VAGO has previously examined issues relating to child protection and residential care services for children. Prevention and early intervention are important not only for the protection and wellbeing of vulnerable children and their families, but also for the community, which ultimately bears the economic and social costs of any failure to intervene effectively.

The importance of early intervention has been reflected in the significant reforms in legislation, government policies and service delivery over the past two decades. In particular, the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005 (CWSA) and the Children, Youth and Families Act 2005 (CYFA) have focused on:

- using community-based intake, assessment and referral services through Child and Family Information, Referral and Support Teams (Child FIRST)

- building an integrated system of family services by establishing Child and Family Services Alliances (alliances) in sub-regional catchment between department-funded Integrated Family Services (IFS) providers, Child Protection and other relevant service providers.

Since 2009, when Child FIRST and IFS were fully implemented, there has been a significant increase in the number and complexity of the cases being referred to these services.

We recognise that an appropriate and adequate response to protecting vulnerable children and families is a shared responsibility. However, this audit focused on the Department of Health & Human Services (the department), as it has the oversight and leadership role of funding the community-based organisations that deliver services for vulnerable children and families. We also examined whether the outcomes for vulnerable children and families are improving. The current lack of 'follow-the-dollar' powers means that we were unable to examine the effectiveness and efficiency of services being provided to vulnerable children and families by community-based and contracted service providers.

Conclusions

Child FIRST and IFS are failing to provide effective services for vulnerable children and families. The increasing number of high-priority cases has made IFS less available to families who are 'at risk' and qualify for an early intervention response, and to professionals seeking to refer vulnerable children and families.

While the department is aware of the significant increase in the number and complexity of cases being referred to Child FIRST and IFS, it has not systematically analysed this demand or planned for early intervention services that can meet the needs of vulnerable children and families at different stages of their vulnerability. The current funding structure does not reflect the growth in the number and complexity of cases or the impact this has had on service providers' capacity to meet the needs of vulnerable families.

The partnership structure that brings together family service providers and department representatives in local alliances is a positive initiative of the department. However, there is great variability in the level of coordination and the maturity of alliances across the 24 catchments. In some catchments, weak partnerships and inadequate governance arrangements have impeded the delivery of integrated and coordinated Child FIRST and IFS. Although the department has worked to improve this, ineffective communication between and across department levels and family service providers remains a problem.

There are isolated examples of vulnerable children and families being better supported. However, the department does not know whether the services provided are effectively meeting the needs of vulnerable groups seven years after the establishment of Child FIRST and IFS. This is because there are significant limitations in the service performance data and a lack of outcomes monitoring at the system level.

Findings

Inadequate and reactive planning

The department's strategic planning for Child FIRST and IFS has been reactive and rudimentary. While the department has made a significant effort to build the capacity of alliances to undertake catchment planning, it has not forecast overall demand for services, assessed unmet or potential demand, or responded to emerging demand drivers—such as family violence—in a timely manner. It lacks the robust evidence base that would enable it to respond to emerging issues effectively at the catchment, divisional and state levels.

Child FIRST and IFS have implemented a range of demand management strategies to cope with the number and complexity of cases being referred. While alliances review their demand management strategies, the department has not identified and evaluated the overall implications of these demand management strategies on the effectiveness of service providers' interventions.

Child FIRST and IFS are operating above their funded capacity in the context of increasing demand and the growing complexity of family needs. The department's failure to adequately monitor or assess why services are delivering above their targets and the consequences of this limits its capacity to redirect scarce resources.

Serious limitations on the department's performance data, and a lack of sound analysis of the available data, limit its capacity to plan proactively and effectively, and reduce the ability of the alliances to plan effectively.

Inadequate partnerships and governance

Child FIRST and IFS rely on multiple providers to deliver services. Effective partnerships and governance arrangements are critical to the coordinated and efficient delivery of these services. The department needs to develop an effective statewide mechanism to engage better with current and potential service providers.

While there are some examples across the state of effective alliances and mature relationships within alliances, these are not always embedded in the organisational system and structure, but rather are dependent on the level of professional capability of individuals.

Effective governance requires clear roles, responsibilities and accountabilities. The department has set up alliances that require Child FIRST and IFS providers to undertake catchment planning together and apply demand management strategies to prioritise local needs. While these steps are positive, the department has not established effective governance mechanisms at the local catchment, divisional or statewide levels. This means there is great variability across catchments in terms of how coordinated planning is, and in the operational and strategic management of service delivery. The department could be doing more to support the development of these partnerships.

The department has identified the need for stronger governance and more clarity around roles and responsibilities between Child FIRST, IFS and Child Protection as key priorities for its next round of catchment plans.

Inadequate performance and outcomes monitoring

While the department has a monitoring framework to assess community-based child and family service compliance with service standards, there is little monitoring of the performance of alliances.

The department's monitoring of services focuses on outputs—such as the number of cases and service hours—rather than requiring service providers to show positive outcomes for families.

There are significant limitations to the department's Integrated Reports and Information System—such as inconsistencies in data collection and poor-quality data. Limited system-level analysis of service data makes it difficult for the department to know whether Child FIRST and IFS are improving outcomes for vulnerable families.

The department does not have a framework for measuring the effectiveness of services for vulnerable children and families. Its 2007 document, A Strategic Framework for Family Services, outlines a plan to develop measures to allow the monitoring of outcomes at the individual, program or catchment, and statewide levels. However, seven years after the framework was released, the department has still not implemented the outcomes component of the plan.

Recommendations

We made one overarching recommendation—that the Department of Health & Human Services takes the key shortfalls identified in this report as the starting point for a comprehensive and urgent review of its current approach to early intervention. This overarching recommendation is supported by nine specific recommendations.

That the Department of Health & Human Services takes the key shortfalls identified in this report as the starting point for a comprehensive and urgent review of its current approach to early intervention and, as part of this review:

- improves planning by better demand forecasting and more systematic analysis of existing program performance data—including analysis of the level and nature of non‑substantive referrals—to understand gaps in service response

- develops a regular statewide engagement mechanism to identify issues and risks in a timely manner and to design solutions with the input of the service sector

- provides targeted training to service providers in catchment planning and data analysis

- reviews its whole-of-system funding for early intervention to better reflect the impact of demand drivers on Child and Family Information, Referral and Support Teams and Integrated Family Services

- provides targeted support to those Child and Family Services Alliance members whose partnerships are still underdeveloped, and supports them to become more collaborative in their interactions

- investigates and implements ways of improving the effectiveness of its communications about operational and strategic issues between and across the department centrally, regionally and locally, and with community service organisations

- provides explicit requirements for its local and divisional staff regarding the monitoring of operational risks, emerging issues, and the capacity and capability of the partnerships involved in the local Child and Family Services Alliances

- develops a set of standard analytical data sets for the Child and Family Services Alliances to use to monitor and report on the timeliness and effectiveness of their engagement with clients at the program level, including rates of failure to engage, referral outcomes re-referrals and re-reports

- undertakes statewide performance analysis using catchment data to facilitate sharing of practices among Child and Family Services Alliance members.

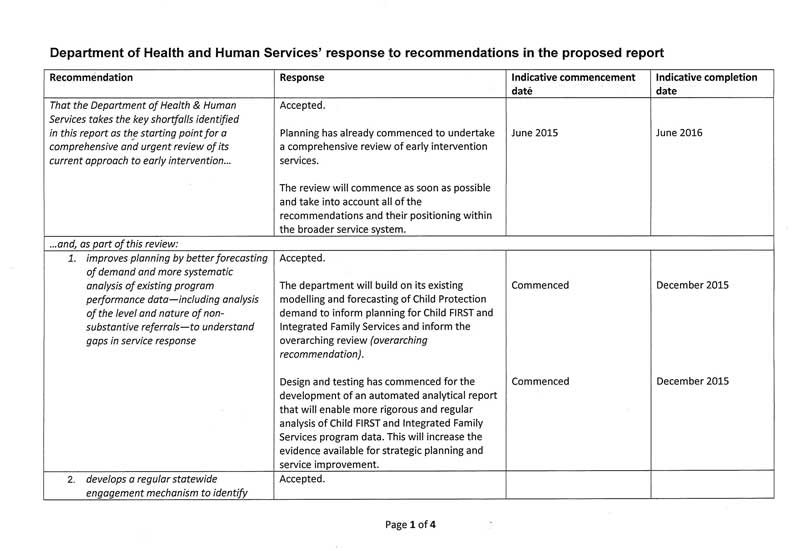

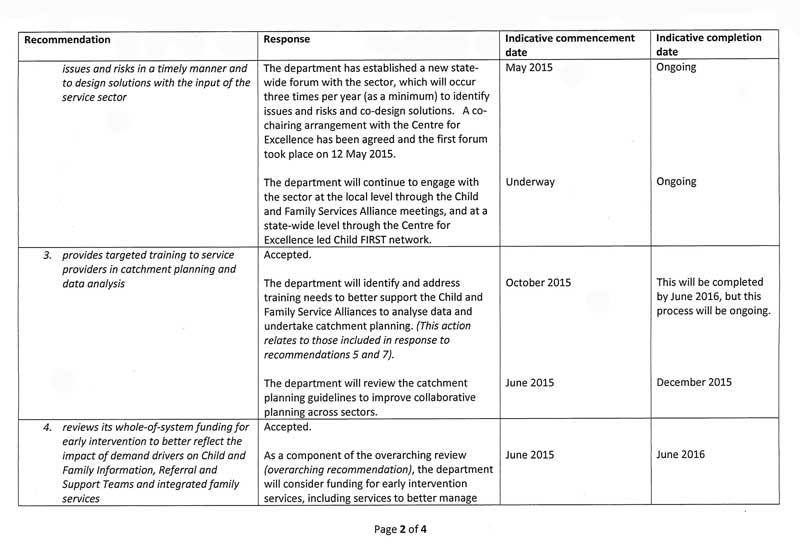

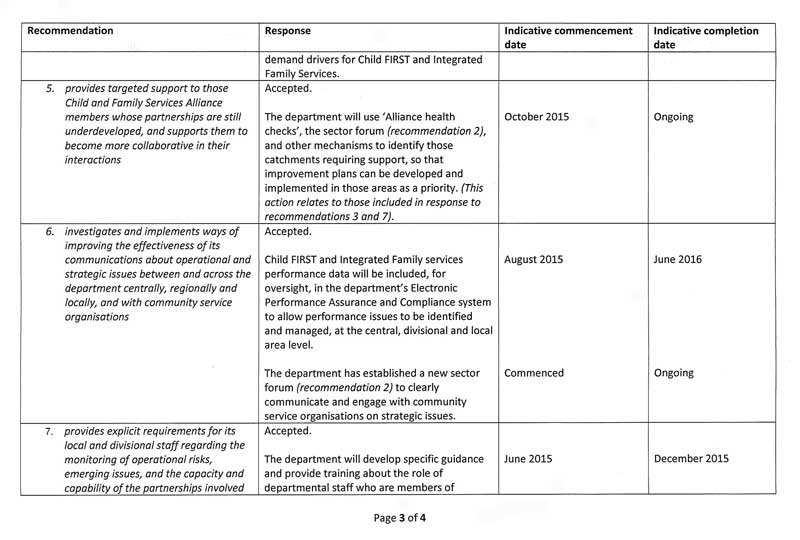

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with the Department of Health & Human Services throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report to the department and requested its submission or comments.

We have considered the department's views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. The department's full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix B.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

The 1996 VAGO report,Protecting Victoria's Children: The role of the Department of Human Services, identified ongoing strain in the statutory child protection system. It recognised that effective prevention and early intervention strategies were key to preventing children from entering the child protection system.

In almost 20 years since the report, the landscape has changed significantly. Successive Victorian governments have commissioned reviews and inquiries into Victoria's child protection system and committed significant funding to supporting and improving this system. While substantial reform has taken place, the demand on the child protection system remains.

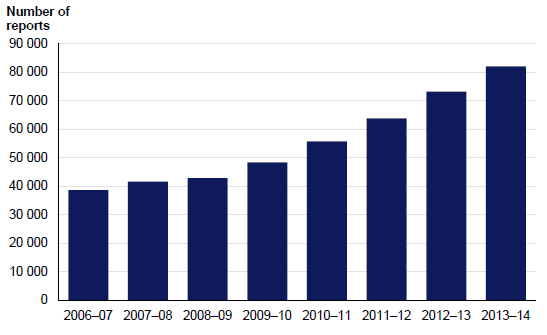

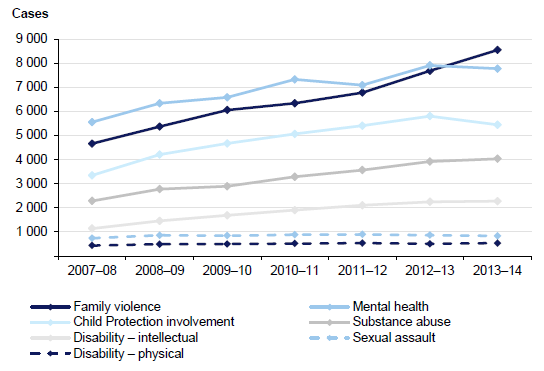

Figure 1A shows that there has been a steady growth in the number of children reported as being at risk of abuse and neglect in Victoria, with reports to the Victorian Child Protection Service (Child Protection) doubling between 2006–07 and 2013–14.

Figure 1A

Reports to Child Protection

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office, using Report on Government Services data.

VAGO's 2014 audit on Residential Care Services for Children found that the system was unable to respond to the growing demand and level of complexity of children's needs, and that diversion strategies in the Out of Home Care system had shown mixed results.

1.2 Vulnerable children and families

The Protecting Victoria's Vulnerable Children Inquiry (the Inquiry) was announced in January 2011 and the report was delivered in February 2012. The Inquiry considered Victoria's system for protecting its vulnerable children and young people as a whole. In response to the Inquiry, in 2013 the government released Victoria's Vulnerable Children—Our Shared Responsibility Strategy 2013–2022, which defined children and young people as vulnerable 'if the capacity of parents and family to effectively care, protect and provide for their long-term development and wellbeing is limited'.

1.2.1 Who is at risk?

A child or young person can be vulnerable for a range of reasons:

- a parent, family member or caregiver may havea history of family violence, alcohol or substance abuse, mental health issues, chronic physical illness or is experiencing financial stress or bereavement

- parents may be young, isolated,unsupported or havelimited parenting skills

- the child or young person may have health issues or a disability

- there may be societal, economic and environmental factors, such as poor social connections in the community, poverty and residential instability.

Some unborn children may be identified as vulnerable during a woman's pregnancy if risk factors for subsequent child abuse or neglect are present. Others only become known to the Department of Health & Human Services (the department) or Victoria Police when they are adolescents and their circumstances have made them vulnerable.

There is a risk that these factors, if not addressed, may escalate and lead to the child and their family becoming involved in the child protection system.

1.2.2 Early intervention

The Inquiry referred to early intervention services as interventions 'directed to individuals, families or communities displaying the early signs, symptoms or predispositions that may lead to child abuse or neglect'.

Figure 1B shows the public health model—used by the Council of Australian Governments in the National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children 2009‑2020—which describes the range of interventions that apply to protecting children.

Figure 1B

Public health pyramid

Source: Australian Institute of Family Studies (2009) adapted from Bromfield & Holzer model (2008).

As shown in Figure 1B, the model is represented as a pyramid of escalating interventions. Primary intervention (universal) services target the entire community to prevent the kinds of social problems that can lead to vulnerability. Secondary intervention services target families in need, where vulnerability has been identified and children are at risk of abuse or neglect. Tertiary intervention services target families where abuse or neglect has already occurred.

The delivery of early intervention services to vulnerable children and families is a secondary intervention.

1.3 Legislative framework

In 2005, the government released the White Paper Protecting Children: the next steps, which aimed to create a more integrated system of child, youth and family services—an accessible adaptable system with a focus on children's safety, health, learning, wellbeing and development.

Two key pieces of legislation were introduced—the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005 (CWSA) and the Children, Youth and Families Act 2005 (CYFA).

1.3.1 Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005

The overarching principles for the wellbeing of children are established in Section 5 of the CWSA. These principles relate to the design and provision of services for children and families, and include protecting the rights of children and families and acknowledging the child's individual identity, including cultural identity.

The legislation requires that, when designing services, consideration be given to:

- minimising harm and strengthening the capacity of parents

- meeting the cultural needs of the local community

- giving the highest priority to those known to have the greatest need

- promoting continuous improvement in the quality of service provision.

Three fundamental principles underpin the provision of services:

- society as a whole shares responsibility for promoting the wellbeing and safety of children

- all children should be given the opportunity to reach their full potential and participate in society, irrespective of their family circumstances and background

- those who develop and provide services, as well as parents, should give the highest priority to the promotion and protection of a child's safety, health, development, education and wellbeing.

The CWSA also recognises that parents are the primary nurturers of a child and government intervention in family life should be limited to that necessary to secure the child's safety and wellbeing. However, government is ultimately responsible for meeting the needs of the child when the child's family is unable to provide adequate care and protection.

1.3.2 Children, Youth and Families Act 2005

One of the key objectives of the CYFA is to support a more integrated system of effective and accessible child and family services, with a focus on prevention and earlier intervention.

Under the CYFA, the key responsibilities of the secretary of the department include:

- promoting the prevention of child abuse and neglect

- assisting children who have suffered abuse and neglect and providing services to their families to prevent further abuse and neglect from occurring

- working with community services to promote the development and adoption of common policies on risk and need assessment for vulnerable children and families

- conducting research on child development, abuse and neglect and evaluating the effectiveness of community-based and protective interventions in protecting children from harm, protecting their rights and promoting their development

- leading the ongoing development of an integrated child and family service system.

The secretary through the department is also responsible for registering, funding, and setting performance standards for community-based child and family services.

Community-based child and family services

The CYFA defines a 'community-based child and family service', as a registered community service organisation established to meet the needs of children requiring care, support, protection or accommodation, or families requiring support.

Community-based child and family services are to:

- provide a point of entry into an integrated local service network that is readily accessible by families, that allows for early intervention in support of families and provides child and family services

- receive referrals about vulnerable children and families where there are significant concerns about their wellbeing

- undertake assessments of needs and risks to assist in the provision of services to children and families and to determine if a child is in need of protection

- make referrals to other relevant IFS providers if this is necessary to assist vulnerable children and families

- promote and facilitate integrated local service networks working collaboratively to coordinate services and supports to children and families

- provide ongoing services to support vulnerable children and families.

1.4 A strategic framework for family services

In 2007, the former Department of Human Services released A Strategic Framework for Family Services (the framework). The framework aims to improve outcomes for vulnerable children, young people and families, by focusing on the:

- 'safety, stability, health, development and learning of children and young people

- cultural connection for Aboriginal children, young people and families

- capacity of families to provide effective care, and of communities to support them

- effectiveness of the supports and services in meeting the changing needs of children, young people and families'.

The framework established an integrated system of family services that included a range of community service organisations and a new central community-based intake model—Child and Family Information, Referral and Support Teams (Child FIRST). The establishment of Child FIRST was based on the evidence of a successful trial that the department had piloted and evaluated from 2003 to 2006. Prior to the introduction of Child FIRST, there were multiple entry points into family services, which had led to inefficient and sometimes duplicated services.

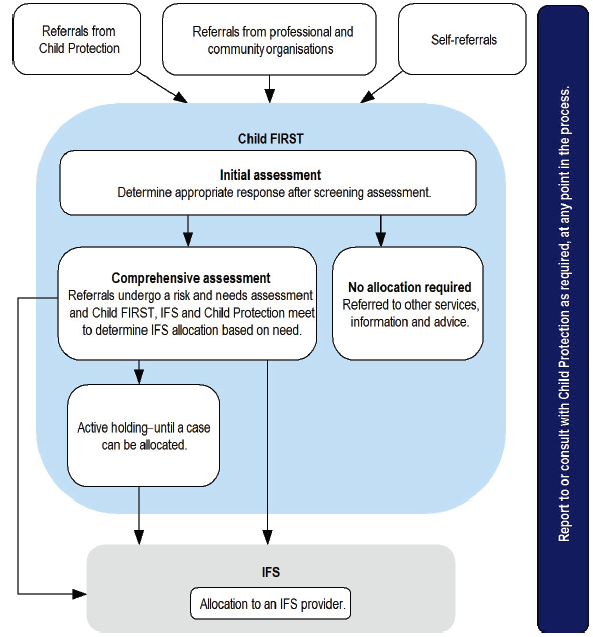

Child FIRST is responsible for the intake and initial assessment phase, while family services are providers responsible for the case work response. This system is commonly referred to as Child FIRST and Integrated Family Services (IFS). Figure 1C shows the most common process once a referral is made to Child FIRST, although there can be local variations.

Figure 1C

The usual process for entering the integrated system of family services

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

There were 96 community-based child and family services, registered and funded by the department in 2013–14 to provide Child FIRST and IFS in Victoria. Appendix A provides a full list of these organisations. These include some of the largest faith‑based service providers whose services are underpinned by a strong ethical commitment to protecting the most vulnerable in our community.

In 2013–14, the budget for both the Child FIRST and IFS components was just over $88 million, including just over $6 million to facilitate Child and Family Services Alliances (alliance) coordination, program development and the employment of Early Childhood Development workers.

1.4.1 Child FIRST

The purpose of Child FIRST is to provide an identifiable and easily accessible entry point into the integrated system of family services within a designated catchment or geographical area. The intention is to effectively link vulnerable children and their families to relevant services based on assessed need and risk.

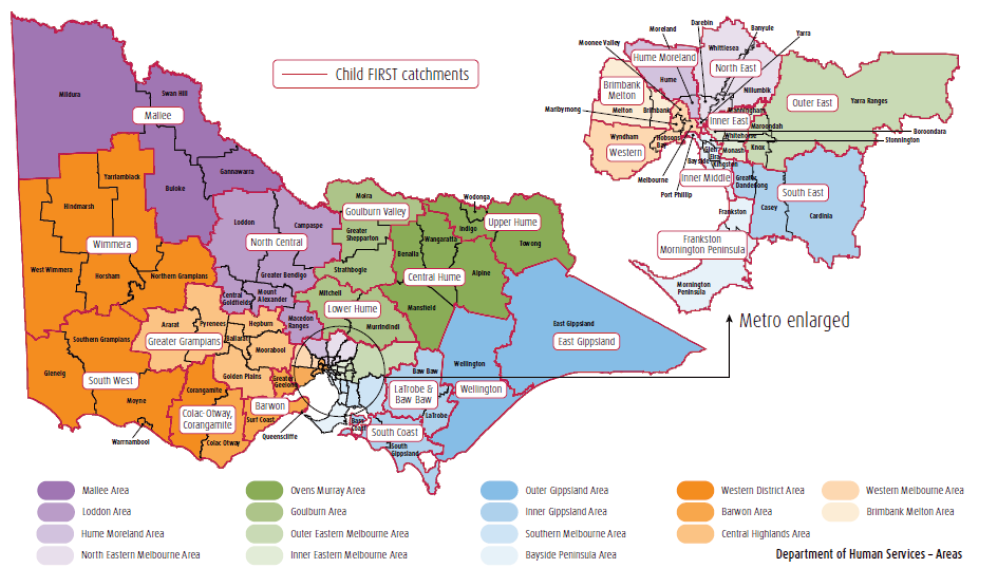

Child FIRST was rolled out from 2006 to 2009. There are 24 Child FIRST catchment areas across Victoria, as shown in Figure 1D.

Figure 1D

Child FIRST catchment areas

Source: Department of Health & Human Services.

The key functions of Child FIRST are to:

- provide information and advice

- identify initial needs and assess underlying risks to the child or young person in consultation with Child Protection, family services and other services or professionals

- identify the Aboriginal status of children and families and consult with an Aboriginal Liaison Worker or Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisation

- actively engage with the child and their family as appropriate to complete an initial risk assessment to determine the priority of a response and allocation of families to the integrated system of family services in consultation with family services and Child Protection, where required

- deliver timely responses through the provision or oversight of 'active-holding responses' that involves short-term work with children and families, before they are allocated to family services.

1.4.2 Integrated Family Services

The aim of IFS is to promote the safety, stability and development of vulnerable children, young people and their families, and to build capacity and resilience for them and their communities.

The primary client group for IFS is vulnerable children and young people aged 0 to 17 years—including unborn children—and their families who are:

- likely to experience greater challenges because the child or young person's development has been affected by the experience of risk factors and cumulative harm

- at risk of becoming involved with Child Protection if problems are not addressed.

1.4.3 Child and Family Services Alliances

To support an integrated and coordinated service response for vulnerable children and families, the department has established alliances as part of the operational and governance arrangements.

These alliances have been set up in each catchment and include Child FIRST, IFS, the department, Child Protection, and—where capacity exists—an Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisation. Other sector representatives and professional groups may be invited to participate, as agreed by the core alliance partners.

Alliances have three key functions:

- undertaking catchment planning

- providing operational management

- coordinating service delivery.

1.4.4 Role of Child Protection

The role of Child Protection workers is to:

- receive reports from people who believe a child needs protection from harm or abuse

- provide advice to people who report cases of abuse and neglect

- investigate when a child is believed to have been abused or is at risk of abuse or neglect

- refer children and families to services in the communityfor ongoing support and prevention

- take matters to the Children's Court if the child's safety within the family cannot be guaranteed

- supervise children on legal orders granted by the Children's Court.

Community-based Child Protection is the term used to describe a range of roles and functions that support partnerships between Child FIRST and IFS and Child Protection, as well as the delivery of family services.

As a central intake point, Child FIRST can receive referrals from Child Protection and can refer families to Child Protection.

1.4.5 Role of the Department of Health & Human Services

The department is responsible for registering, accrediting and funding the community service organisations that deliver services for vulnerable children and families. It is also responsible for leading the ongoing development of an integrated child and family service system.

The department is represented at divisional (regional) and local (catchment) levels.

1.4.6 The Shell Agreement

The operational requirements between the department and IFS are found in the 2013 Child Protection and Integrated Family Services State-wide Agreement (Shell Agreement). The purpose of the Shell Agreement is to bring together key partners from IFS and Child Protection to formalise a shared purpose and consistent approach for working together. The Shell Agreement articulates the importance of the relationship between IFS and Child Protection and the significant role of community-based Child Protection in supporting these relationships.

1.5 Past reviews and evaluations

In 2011, the former Department of Human Services commissioned an evaluation of Child FIRST and IFS. The evaluation identified a need to:

- improve coordination activities

- take a stronger statewide approach to demand management.

- improve how IFS and Child Protection work together

- strengthen partnership and governance.

The 2012 Report of the Protecting Victoria's Vulnerable Children Inquiry found the role of Child FIRST to be ill-defined and its governance structure inadequate. The Inquiry also identified that some Child FIRST networks were significantly under-resourced, while others were unable to meet their required service quotas. Recommendations to improve Child FIRST focused on governance—the creation of Area Reference Committees to oversee the monitoring, planning and coordination of services and management of operational issues within catchments—and a more consolidated intake model that would combine Child FIRST and statutory child protection intake processes.

In 2010, the Victorian Ombudsman's Own motion investigation into Child Protection – out of home care found that:

- Child FIRST was experiencing a level of demand that it could not satisfy

- there were variations in the thresholds that applied when Child FIRST was deciding whether to investigate a child or family

- performance measures needed to be more comprehensive and to measure effectiveness.

The Victorian Ombudsman recommended the development of a comprehensive strategy for improving understanding between Child Protection and Child FIRST workers regarding their respective roles and agreed processes.

1.6 Audit objective and scope

The objective of this audit was to determine the effectiveness of community-based child and family services for vulnerable children and families. Specifically we examined whether:

- community-based child and family services are improving outcomes for vulnerable children and families

- vulnerable children and families are able to access community-based child and family services as needed.

This audit focused on the department and its key family services program—Child FIRST and IFS.

The audit did not include other government departments with responsibilities for the provision of early intervention services for children at risk. It also did not examine the effectiveness and efficiency of services provided by community-based and contracted services providers to vulnerable children and families.

1.7 Audit method and cost

The audit methodology included:

- review of relevant documents and data

- interviews with relevant department staff

- site visits and interviews with a sample of community-based family services including executive and operational staff

- attendance at, and discussion with, a selection of Child FIRST and IFS alliance members

- focus groups with:

- Child FIRST and IFS workers

- chief executive officers of alliances

- chairs of alliances.

The audit was conducted in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards.

Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of the audit was $445 000.

1.8 Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

2 Planning an integrated system of family services

At a glance

Background

Planning for integrated services at the strategic and local levels needs to be informed by a sound understanding of the changing demand drivers that contribute to vulnerability, gaps in service supply, and how well resources are allocated and prioritised.

Conclusion

The Department of Health & Human Services' (the department) planning for Child and Family Information, Referral and Support Teams (Child FIRST) and Integrated Family Services (IFS) has been reactive and rudimentary. While the department has made a significant effort to build the capacity of Child and Family Services Alliances (alliances) to undertake catchment planning, it has not forecast overall demand for these services, assessed unmet or potential demand, or responded to emerging demand drivers in a timely manner. IFS are delivering beyond their funded capacity, casting doubt on the sustainability of the current model.

Findings

- The department's capacity to plan effectively has been undermined by inadequate performance data and limited analysis of the available data.

- In the context of increasing demand and the growing complexity of families being referred to Child FIRST, Child FIRST and IFS are operating above their funded capacity—in 2013–14, service providers contributed the equivalent of $5.3 million hours of service.

- The department has not engaged sufficiently with the sector in responding to emerging issues, such as family violence.

Recommendation

That the department takes the key shortfalls identified in this report as the starting point for a comprehensive and urgent review of its current approach to early intervention and, as part of this review, undertakes a comprehensive review of its current approach to early intervention, including reviewing its planning, engagement with the sector, training for alliances, and whole-of-system funding for IFS.

2.1 Introduction

Effective early intervention to support vulnerable children and families requires ongoing and evidence-based service planning at the strategic and local levels. In a devolved service delivery model, the Department of Health & Human Services (the department) is responsible for strategic planning and Child and Family Services Alliances (alliances) are responsible for developing and implementing catchment plans. Catchment planning is one of the three key functions of an alliance.

At both the strategic and alliance levels, effective planning needs to be informed by:

- changes in demand drivers that contribute to vulnerability—factors that are leading to more or different families becoming vulnerable and therefore in need of support services

- gaps in service supply—information about changing demographics and whether services are appropriate and sufficient to meet the populations changing needs

- an understanding of how well resources and processes are organised and prioritised to support the best possible delivery of services to achieve the intended outcomes.

This Part examines whether:

- the department's strategic planning has been based on a sound understanding of demand, and adequately addresses service gaps

- the department has provided adequate leadership and support for the service sector

- the current funding structure accurately reflects the services that are required.

2.2 Conclusion

The department's strategic planning for Child and Family Information, Referral and Support Teams (Child FIRST) and Integrated Family Services (IFS) has been reactive and rudimentary. While the department has made a significant effort to build the capacity of alliances to undertake catchment planning, it has not forecast overall demand for Child FIRST and IFS, assessed unmet or potential demand, or responded to emerging demand drivers in a timely manner. The department lacks the robust evidence base that would enable it to respond to emerging issues effectively at the alliance, divisional and state level. In the face of significant growth in demand for services, IFS are delivering beyond their funded capacity, casting doubt on the sustainability of the current model.

2.3 Understanding demand and supply

The department is aware of the significant increase in the number and complexity of cases referred to Child FIRST and IFS. However, it has not systematically analysed this demand at the alliance or state level to inform its strategic planning. It has not systemically planned for early intervention services that can meet the needs of vulnerable children and families at different stages of their vulnerability.

While acknowledging that the department is currently doing preliminary work on child protection demand drivers and their locations, a system-wide approach and understanding is needed if the department is to be assured that services and resources are appropriate and sufficient.

2.3.1 Understanding and forecasting demand

Demand for Child FIRST and IFS is driven by changes in:

- risk factors that contribute to vulnerability within a family and local community—such as unemployment, family violence, substance abuse, mental and physical disability, social exclusion

- referrals from the Victorian Child Protection Service (Child Protection) which have grown substantially since 2006–07.

Since Child FIRST and IFS were fully implemented in 2008–09, there has been a noticeable increase in the number and complexity of the cases being referred to them—as shown in Figure 2A. While the overall number of referrals to Child FIRST and IFS combined has only increased by 7 per cent, the number of referrals to Child FIRST—as the gateway—has increased significantly. However, we have not been able to gain sufficient assurance that the data in Figure 2A is reliable as the department does not routinely do this type of analysis, and the first data set it provided was inaccurate.

Figure 2A

Increases in demand and complexity of cases referred

2008–09 |

2013–14 |

Change (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Referrals to Child FIRST/IFS |

62 902 |

67 510 |

7 |

Non-substantive referrals to Child FIRST(a) |

41 989 |

44 205 |

5 |

Substantive referrals to Child FIRST(b) |

8 053 |

12 763 |

58 |

Accepted cases with one to four complex issues to Child FIRST/IFS |

11 527 |

15 519 |

35 |

(a) A

non-substantive case is where less than two hours of service, typically through

information and advice, is provided.

(b) Substantive

referrals require the establishment of a case and allocation of a case worker.

Source: Victorian

Auditor-General's Office based on data provided by the department.

Despite the significant increase in demand, the department has not sufficiently analysed the:

- nature and service outcomes of the non-substantive referrals

- capacity of Child FIRST and IFS to respond to the growing complexity of cases

- implications of not providing early intervention for those who—based on prioritisation of need—do not receive services from Child FIRST and IFS.

Non-substantive referrals

The department collects Child FIRST and IFS data at the service level using the Integrated Reports and Information System. It defines non-substantive referrals as those receiving less than two hours where one or more of the following applies:

- there is insufficient information about the family to officially register the family with a service provider and establish a file

- the family receives a one-off intervention

- there is no comprehensive assessment to identify the family's issues

- the family does not receive more than two staff-hours of services from all staff combined.

Alliances report that when demand is high, they record more referrals as non‑substantive because they have limited capacity to provide anything other than information and advice. Non-substantive referrals do not require the opening and registering of a case in the Integrated Reports and Information System. When demand is high this practice is also considered expedient but creates a risk that the real level and nature of family vulnerability is not being captured. Because no case is opened, the nature of the risk is not identified and potential precursors for escalating risk are not recorded or able to be tracked.

The department has not monitored or analysed data on non-substantive referrals. It does not know whether the families of non-substantive referrals represent unmet demand for early intervention or whether the lack of services being provided at this stage potentially leads to escalation of family issues that increases vulnerability.

Child FIRST is required to prioritise service provision to the most vulnerable families in keeping with the legislative intent of the Children, Youth and Families Act 2005. However, this creates tension for family services, which are also required to fulfil another important legislative mandate—to 'provide a point of entry into an integrated local service network that is readily accessible by families, that allows for early intervention in support of families'.

This gap between the need for early intervention and the alliances' capacity to respond to vulnerable families with lower levels of risk, was identified as early as 2009 when the department evaluated the roll out of Child FIRST and IFS across the state. However, it has not taken steps to understand and address the impact of this gap on the system. While the provision of appropriate child and family services is influenced by available government funding, the department's lack of robust, system-level demand forecasting has limited its ability to provide sound evidence to support government decision‑making.

The department's main focus has been on understanding the demand for Child Protection services. Over time it has gradually improved its demand forecast capability for these services. This has included identifying how different demographic groups respond to Child Protection services, the factors that contribute to growth in demand, and gaining a better understanding of pathways and flows within the Child Protection system.

These developments have been positive and have contributed to a more reliable prediction of demand for Child Protection services, which has been reflected in the department's recent budget submissions. However, it needs to apply a similar methodology to Child FIRST and IFS to improve its demand forecasting to enable an appropriate and sufficient service response.

In late 2014, the department began two pilot projects to examine:

- individuals' likely lifetime contact with Child Protection and associated services, such as family services

- complex client groups and the effective timing of interventions across the whole government service system—in a joint investigation with the Department of Premier and Cabinet as lead agency it is investigating those who use multiple government services.

Both initiatives are likely to inform demand planning, but it is too early for their effectiveness to be assessed.

2.3.2 Managing demand

Regular analysis of service response patterns at alliance and state levels should enable the timely identification of service gaps and capacity shortages. This is critical to effective service planning. While alliances review demand management strategies locally, the department has not identified and evaluated the overall implications of the demand management strategies being implemented by alliance members. Not knowing the impact of these strategies has limited the department's capacity to take a strategic, targeted and proactive approach to planning.

Faced with the challenges of increased demand and complexity of cases coming to Child FIRST and IFS, alliance members have adopted a range of demand management strategies, including:

- reducing the number of attempts to engage with families

- engaging with families for shorter periods of time than they might otherwise have done

- introducing a longer period for 'active holding' of families, during which information and advice is provided while waiting for a case manager to become available. Alliance members advise that prolonged delays in allocating families to services are a key reason for families becoming disengaged.

Figure 2B shows some of the implications for vulnerable families arising from the demand pressures at one local alliance.

Figure 2B

One alliance's approach to managing increased demand

Demand has been so high at one Child FIRST alliance located in a growth corridor of metropolitan Melbourne that it restricted its access by not accepting any new cases for two weeks in June 2014 and a further two weeks in November 2014. During this time it only offered information and advice. This occurred despite alliance members having already applied several other demand management strategies, including:

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information provided by one alliance member.

Engaging vulnerable families is critical to the success of family services work. Across the state, the increase in the demand and complexity of cases is compromising the quality of engagement and case support.

Between 2008–09 and 2013–14—as a result of demand increases—there has been:

- an increase of 37 per cent in the number of referrals that are diverted or not recorded as a 'case' at intake and therefore closed prior to being assessed or at assessment, before getting the full benefit of family service support

- an overall increase of 75 per cent in the number of cases closed at these early stages due to the family not engaging with the service.

As effective intervention is predicated on successful and meaningful engagement with vulnerable families, this trend should be of particular concern to the department.

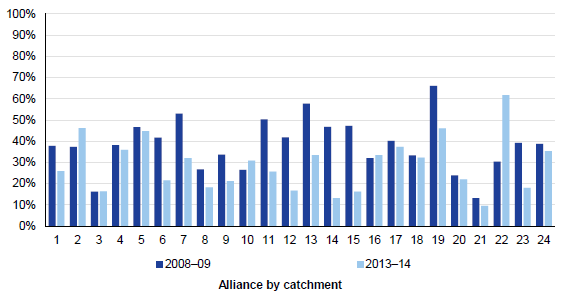

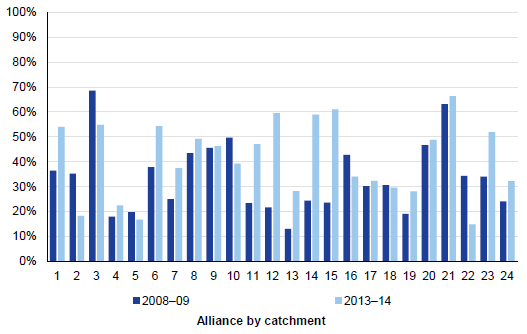

The department has not identified whether services are adequately responding to this increase in demand and complexity. Figures 2C and 2D show great variation across the 24 Child FIRST catchments in the proportion of complex cases they responded to between 2008–09 and 2013–14. While most alliances have taken on more complex cases, catchments 2 and 22 have taken on smaller proportions of complex cases and increased the number of cases with no complex issues. The department has not identified or addressed the underlying reasons for these trends and variations or the implications for vulnerable families.

Figure 2C

Cases with no complex issues by alliance catchment (per cent),

2008–09 versus 2013–14

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data provided by the department.

In 2013–14, 12 of the 24 alliances delivered more than 30 per cent of all their cases to clients with no complex issues, even though the intent of the program is to prioritise the most vulnerable clients.

Figure 2D

Cases with two or more complex issues by alliance catchment (per cent), 2008–09

versus 2013–14

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data provided by the department.

Six alliances delivered less than 30 per cent of their cases to clients with more than two complex issues. This included alliances in areas identified by the department as containing some of the most vulnerable client groups—with high levels of reported domestic violence incidents, Child Protection reports and alcohol and other drug treatment clients. This raises the question of whether these alliances are appropriately targeting their services to the most vulnerable families.

2.4 Planning for diversity

An accurate understanding of family diversity and need is essential for effective local- and system-level planning

2.4.1 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families

The department reports regularly at the alliance and system level on the number of cases involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, in response to recommendations from the 2011 Protecting Victoria's Vulnerable Children Inquiry. Departmental data shows that the number of family service cases involving these families has increased by 51 per cent from 1 582 in 2009–10 to 2 388 in 2013–14.

However, the data shows the number of cases, not families. A case is measured as a single episode of support. As multiple cases can relate to one family, the department does not know:

- how many families were involved in these cases

- how many cases were provided to each of these families

- whether some families have presented in the system multiple times

- the level of unmet demand in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population.

The department should report on the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families receiving family service support as well as the number of cases to improve its understanding of need and trends.

2.4.2 Culturally and linguistically diverse groups

Currently there is no monitoring or reporting requirement for culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) family access to Child FIRST and IFS. Across the system, the proportion of families registered by Child FIRST in 2013–14 who were born overseas and who do not speak English well, or at all, is relatively small at 6.8 per cent. However, there has been noticeable population growth in CALD families across the state, especially in the growth corridors in the south-east and north-west metropolitan areas. For example, in the City of Greater Dandenong 60 per cent of the population was born overseas and 55 per cent are from nations where English is not the main language. The department needs to examine whether the very low representation in Child FIRST reflects a lack of awareness of services by these groups, a lack of access or a lack of appropriate cultural competency by the alliances.

Refining the measurement and reporting on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and CALD family access will assist the department's planning in this regard.

2.5 Planning to support the service sector

The department has provided guidance material to support the service sector—such as promoting a common approach to needs and risk assessment, and providing professional development through the Office of Professional Practice. It has also undertaken initiatives—such as Cradle to Kinder and Early Childhood Development workers—to target specific groups of vulnerable children during their early years.

However, it has been slow to address the implications of changing demand trends on service providers. For example, as shown in Figure 2E, between 2008–09 and 2013–14, there was a dramatic rise in the number of family violence referrals to Child FIRST and IFS—an increase of around 52 per cent overall, or an average of around 9 per cent per year. Referrals associated with intellectual disability, substance abuse and mental health issues also grew in this period by 49 per cent, 36 per cent and 16 per cent respectively. Referrals of families previously involved with Child Protection grew by 22 per cent. All of these changes have affected the capacity of Child FIRST and IFS to effectively meet the needs of these vulnerable families.

Figure 2E

Number of new cases opened by recorded issue

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data provided by the department.

Recognising the significance of family violence as a key driver of vulnerability in families, the department has led a statewide approach to responding to family violence and has developed appropriate risk assessment tools. Figure 2F provides two examples where the department has effectively supported the sector.

Figure 2F

Sector support materials for family violence

In 2007, the former Department of Human Services (DHS) published the Family Violence Risk Assessment and Risk Management Framework—referred to as the Common Risk Assessment Framework—after extensive consultation. This guide was well received and used by professionals and service providers. A second edition was released in June 2012. In 2013, DHS published Assessing children and young people experiencing family violence: A practice guide for family violence practitioners. Training sessions have been rolled out across the state and have been well attended. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information provided by the department.

Despite these initiatives, the department's response has not been timely in terms of sector need. For example, in October 2010, Victoria Police reviewed its code of practice which led to an unprecedented increase in referrals for family violence being made to family violence specialists, Child Protection and Child FIRST. One alliance member reported receiving an average of over 15 reports a month from Victoria Police between 2011 and 2013, compared to two or three a month prior to 2010. This increase was accompanied by uncertainty, inconsistent practices and the duplication of effort by the multiple service providers that were receiving reports. This alliance reports that the average number of family violence referrals has increased to 22 a month in 2014 and 35 a month in 2015.

While Victoria Police did not intend to change the established referral pathways, the respective roles and responsibilities of Child Protection and Child FIRST became unclear. The department worked with Victoria Police to clarify and develop a common approach to referral pathways and later engaged with a small group of representatives from the service sector. It released a family violence referral protocol in May 2013 with the agreement of the sector. However, it took the department over 2.5 years to fully implement this change at a time when alliance members were struggling to cope with the high numbers of family violence-related referrals.

2.6 Funding to support service delivery

Currently, the demand for Child FIRST and IFS exceeds the funding provided to the sector. This has been the case since 2011–12. In the face of significant growth in demand for services, Child FIRST and IFS alliances are delivering beyond their funded capacity. The department needs to investigate whether this 'over-performance' is due to increased efficiency or alliance self-funding.

2.6.1 Service delivery funding

The department funds providers of Child FIRST and IFS according to agreed targets based on the number of service hours and cases delivered. Cases are classified as follows:

- entry level—up to 10 hours

- short response—between 10 to 40 hours

- long response—from 40 to 110 hours.

In 2013–14, just over $88 million was given to Child FIRST and IFS providers to deliver 33 527 cases of family support. This funding includes around $4 million for alliance facilitation and development. In 2013–14, the department's funding model allowed for 923 539 hours of services.

Adequacy of the funding model

The funding model no longer reflects what services are being delivered on the ground, or for how long. Most notably, in 2013–14, the department's data on actual cases delivered showed that Child FIRST—funded only as an intake gateway to IFS—delivered:

- short responses to 4 619 families

- long responses to 239 families

- services extending beyond 110 hours to eight families.

By contrast, IFS provided fewer entry level responses than funded, yet significantly more extended responses—which were not originally planned for when the program was first established.

The department has not analysed this data to gain a better understanding of why Child FIRST is going beyond its entry level role to take on so many short and long responses. The department advises that at least some of these cases may be the result of inaccurate recording but the extent of this is not known.

Between 2007–08 and 2013–14, the department increased funding to Child FIRST by 217 per cent, but decreased case targets to IFS by 2 per cent in the same period. The funding has not supported the progression of cases beyond Child FIRST to an IFS response. Insufficient IFS capacity means it is likely that some families who may be willing to engage with IFS are not getting beyond the intake gateway. This is counter to the intent of the Child FIRST role as originally conceived. The department has not analysed the data to determine whether there is a bottleneck at Child FIRST.

Actual cases and hours of service delivery

In 2013–14, while the department funded for 33 527 cases, alliances only delivered 32 346 cases. However, what was delivered used more hours, as evidenced by the number of cases exceeding 110 hours (2 071 cases). Service delivery above 110 hours was not budgeted for by the department. The department's funding approach does not reflect the changing reality of service demand. The department advises it is developing a new funding category of 200 hours in recognition of the extended time being taken to support vulnerable families.

In 2013–14, alliances delivered 982 441 hours of service while the department funded for a total of 923 539 hours. This means that providers self-funded more than 58 000 hours of service delivery.

Based on the 2013–14 unit price of $90.28 per hour, providers of Child FIRST and IFS have delivered an additional $5.3 million worth of services above the funding provided by the department. The department does not know if this is because of service provider inefficiency, inaccurate reporting or because of a strong ethical commitment to support families over and above funded capacity.

'Over performance' of IFS providers

The department does not assess the reasons for 'over-performance' or whether the reported performance is accurate or sustainable. This means the department has accepted the additional hours provided by alliance members without seeking a comprehensive picture of what is really happening. The department should be asking questions:

- Are these hours the product of considerable goodwill on the part of service providers that is not being recognised?

- Could service providers be using their time with families more efficiently and effectively?

- Are hours being reported accurately?

- Above all, are vulnerable families receiving the level and kind of support that they need?

The department needs to undertake a comprehensive and urgent review of its funding model, including the assumptions that underpin this model and the outcomes it is intended to deliver.

2.6.2 Alliance activity funding

In 2013–14, just over $6 million was provided to facilitate and develop Child FIRST alliances. This included:

- $2.7 million of program development funding—provided to all department‑funded alliance members at 3 per cent on top of service delivery funding per member, andintended to support member participation in alliance activities

- just under $1.4 million of alliance facilitation funding—provided to the designated lead member of each alliance, which may be used to supportcatchment planning, demand management, or to employ a project manager within the alliance

- around $2 million—provided to employ EarlyChildhood Development workers.

There is no requirement for alliance members to report how they use this funding. The department has advised that program and facilitation funding is recorded only by the department's local areas. The department's financial systems, which report based on the 17 departmental areas, do not provide information about funding at a catchment level. This makes it difficult for the department to gain a clear picture of whether funding at an alliance level is adequate for intended activities.

We analysed the self-reported funding activities of five lead organisations in different catchment areas and found that:

- It is common for the lead organisations to cross-subsidise their Child FIRST function using other state-funded program resources—in agreement with the department—including funding allocated to IFS. This includes IFS staff taking on referral intake and assessments, and the allocation of IFS staff to Child FIRST.

- Program management funding received from the department only partially covers the program management role for the lead members of alliances. Service provider-generated funding isused to subsidise this function, which providers considered to be unsustainable.

- These lead members have also contributed to program administration from their own funding.

- Two of the five service providers used local government funding to support their work with children from vulnerable families. Most of the five have used short-term responses to accommodate demand and limited resources.

- Current funding and service agreements no longer align with the services delivered. As cases become more complex, alliances report it is often not possible to close a case within 110 hours. The department advises that it is now working on a 200-hour funding category although it has been aware of the increase in complexity for the past six years.

- Significant variation in case complexity between alliances also indicates some areas may be over-serviced while others may be under-serviced.The department needs to undertake a system-level review of its funding structure. While it needs to enable local providers to make decisions about funding expenditure that reflect local priorities, it should nevertheless monitor how funds are being used and whether current performance in relation to set targets is sustainable.

2.6.3 Support for catchment planning

Catchment planning by alliances is aimed at achieving:

- a more integrated and coordinated service system

- earlier identification and intervention to support vulnerable families

- streamlined referral pathways among local community-based organisations involved in child and family services.

The department has made a significant effort to build the capacity of alliances to undertake catchment planning, including:

- holding workshops focusing on planning processes, the use of planning data and issues arising from catchment planning

- developing a catchment planning reference guide and template—released in July2009 and updated in August 2012.

However, effective catchment planning needs to be informed by reliable, accurate data on population trends and the associated demand for services. This includes Child Protection data as Child Protection notifications are a common demand driver for IFS. While issues to do with a lack of Child Protection data for catchment planning purposes were identified by alliances in discussions with the department—and the provision of such data centrally was made available to alliances in 2008–09—it was not until after 2013 that the department made data available to alliances statewide.

Recommendations

That the Department of Health & Human Services takes the key shortfalls identified in this report as the starting point for a comprehensive and urgent review of its current approach to early intervention and, as part of this review:

- improves planning by better demand forecasting and more systematic analysis of existing program performance data—including analysis of the level and nature of non-substantive referrals—to understand gaps in service response

- develops a regular statewide engagement mechanism to identify issues and risks in a timely manner and to design solutions with the input of the service sector

- provides targeted training to service providers in catchment planning and data analysis

- reviews its whole-of-system funding for early intervention to better reflect the impact of demand drivers on Child and Family Information, Referral and Support Teams and Integrated Family Services.

3 Effective governance and partnership

At a glance

Background

Effective partnerships and governance are characterised by mutual trust and accountability, clear roles and responsibilities, a common purpose, and regular monitoring and review of these arrangements. These features are critical to the coordinated and efficient delivery of Child and Family Information, Referral and Support Teams (Child FIRST) and Integrated Family Services (IFS), given that multiple organisations are involved in responding to vulnerable children and families.

Conclusion

Inadequate governance arrangements and significant variability in the quality of the local IFS partnerships have impeded the delivery of integrated and well-coordinated Child FIRST and IFS. Although the Department of Health & Human Services (the department) has worked towards building effective and strong governance over the years, there are still issues to do with a lack of clarity around roles and responsibilities, and inadequate communication between the department's staff locally, regionally and centrally, and with local service networks.

Findings

- Alliance members do not always work collaboratively, which reduces their capacity to provide coordinated and integrated services.

- The department has not established effective governance mechanisms at the catchment, divisional or state levels.

- Engagement with the sector across the different levels—catchment, divisional and state—has not been consistent or adequate.

Recommendation

That the Department of Health & Human Services takes the key findings identified in this report as the starting point for a comprehensive and urgent review of its current approach to early intervention and, as part of this review, provides targeted support to Child and Family Services Alliance (alliance) members, and improves the effectiveness of its communications about operational and strategic issues between and across the department centrally, regionally and locally and with alliance members.

3.1 Introduction

Child and Family Information, Referral and Support Teams (Child FIRST) and Integrated Family Services (IFS) rely on multiple community organisations to deliver services. Effective partnerships and governance are critical to the coordinated and efficient delivery of these services.

The 2011 Protecting Victoria's Vulnerable Children Inquiry identified partnership and governance issues as inhibiting factors for integrated service delivery in the early stages of the Child FIRST and IFS rollout in 2009.

This Part examines whether the Department of Health & Human Services (the department) has established clear strategies and guidelines to enable the development of effective partnerships and governance.

3.2 Conclusion

Currently there is great variability in the level of coordination and the maturity of the Child and Family Services Alliances (alliance) across the 24 catchment areas. The department could be doing more to support the development of these partnerships.

Weak partnerships and inadequate governance arrangements have impeded the delivery of integrated and coordinated Child FIRST and IFS. Although the department has worked towards building effective alliances and strong governance over the years, there are still issues to do with a lack of clarity around roles and responsibilities, and inadequate communication between IFS providers and the department's staff locally in the catchment areas, divisionally and centrally.

3.3 Developing effective partnerships

3.3.1 Characteristics of mature alliances

We found examples of mature relationships between alliance members and effective alliances across the state—as shown in Figure 3A. However, many alliances function more as collections of individual members. In these alliances there is limited data and resource sharing, or transparency around funding capacity. Collaboration does not appear to be embedded in the organisational system and structure of member organisations.

Figure 3A

Characteristics of better practice in one alliance

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information provided by one alliance.

3.3.2 The need to better support alliances

The department did not address the critical prerequisite of developing and facilitating the partnerships of alliance members when it rolled out Child FIRST and IFS. This was a significant strategic oversight.

During the department's catchment planning workshops in 2008, 2009 and 2010, alliance members consistently identified the need to strengthen partnership and governance arrangements within alliances.

In 2008, the department commissioned a three-year evaluation of the statewide implementation of Child FIRST and IFS. The consultant's 2009 interim and 2011 final reports both concluded that there was a critical need to strengthen the sustainability of alliance partnerships. The 2011 report proposed that the department should:

- provide the alliances with tools and resources to monitor the 'health' or soundness and sustainability of their partnerships

- enable effective management of leadership succession

- develop stronger accountability for partnership performance

- provide resources for an alliance project officer across all catchments.

In 2012, the department developed its Strengthening partnership strategy in response to the 2009 Ombudsman Victoria report Own motion investigation into the Department of Human Services Child Protection Program. It requested that alliances use this strategy to examine the health of their relationships and to identify problems and strengths. The department now requires this partnership 'health-check' process to be embedded as part of annual catchment planning activities. This kind of self-help is a positive step supporting the growth of stronger partnerships.

3.3.3 A continuum of partnership development

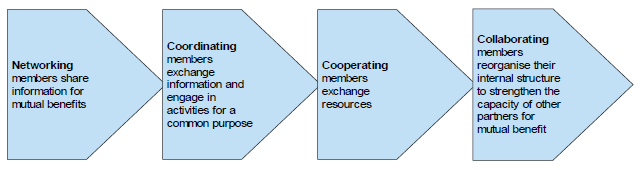

VicHealth's The partnerships analysis tool identifies the critical stages of a partnership. Figure 3B shows this continuum, with collaborating being the most advanced form of partnership.

Figure 3B

Stages of partnership

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on VicHealth's The partnerships analysis tool.

Based on our survey of alliances and review of relevant documents at a number of alliances—such as memorandums of understanding (MoU), demand management strategies and catchment planning documents—we found many alliances still at the 'coordinating' stage. Members participate in alliance activities as individual organisations within their funded capacity to take on cases referred to them, rather than working collaboratively for a common purpose. Most alliance members only share demand information and case allocations with each other. Sometimes assessments are shared. Few share their funding and case capacity.

There are a small number of alliances with advanced partnerships and strong performance in service delivery. Figure 3A shows the characteristics of an effective alliance performing at the 'collaborating' stage of partnership.

Figure 3C shows how client outcomes improved as a result of integrated service delivery. The family described has complex issues, with both parents having learning difficulties and the children having been diagnosed with learning difficulties, disability and developmental delay.

Figure 3C

An example of integrated service delivery

|