Effectiveness of the Tutor Learning Initiative

Audit snapshot

What we examined

We examined whether the Tutor Learning Initiative improved learning and engagement outcomes for participating students in government schools.

Agency examined: Department of Education.

Why this is important

When students fall behind in school, not getting the support they need can have lifelong consequences. Small group tutoring can help these students catch up and succeed in the classroom.

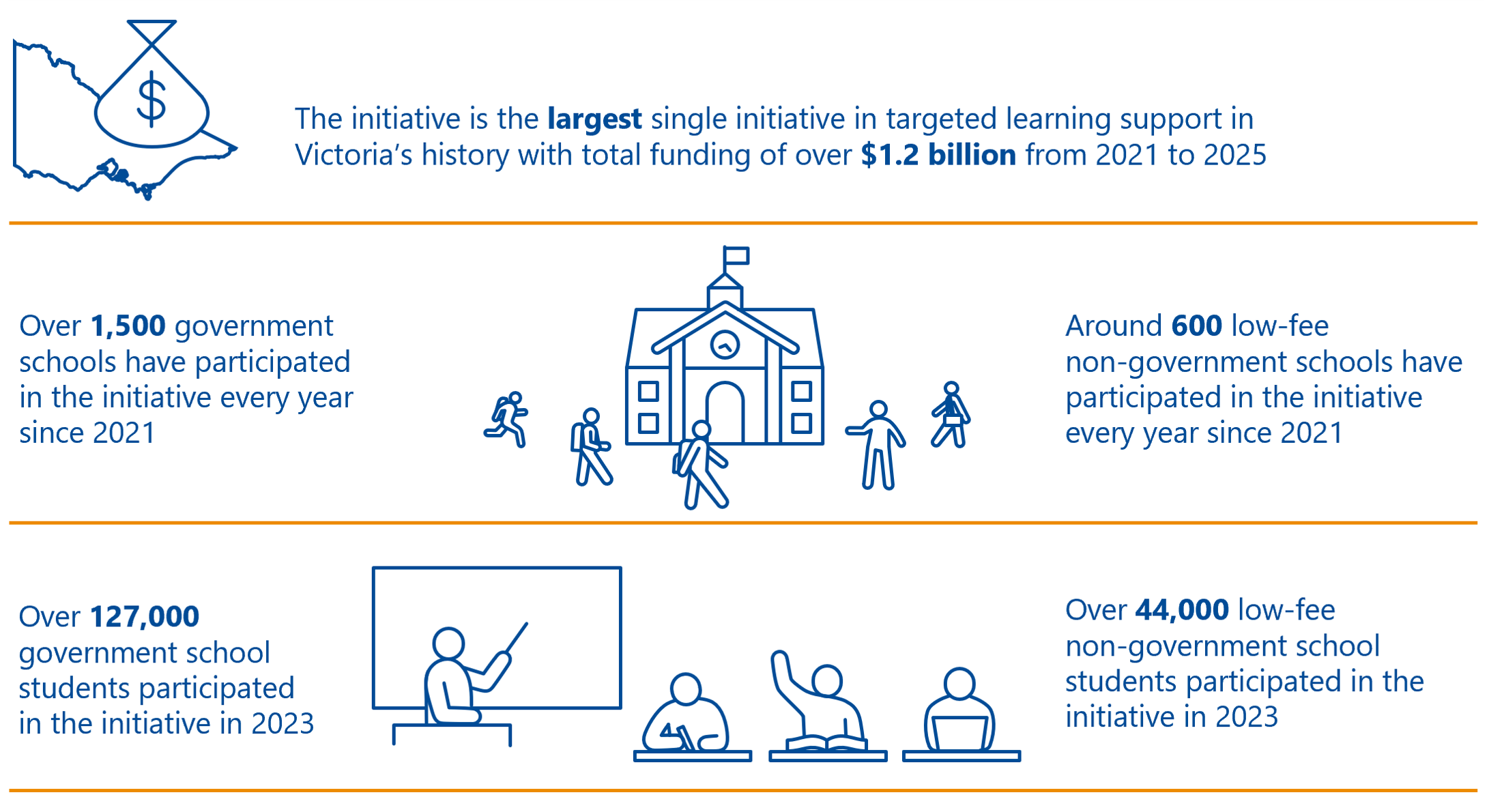

The Victorian Government has invested $1.2 billion in the Tutor Learning Initiative (the initiative). This statewide program funds schools to employ tutors to deliver targeted small group learning support to students who need it most.

The Department of Education (the department) has a responsibility to improve schools' delivery so these statewide programs achieve their objectives.

What we concluded

We found that the initiative did not significantly improve students’ learning compared to similar non tutored students.

The department provided effective support so that schools delivered tutoring when students needed it.

Many schools' tutoring practices in 2023 were not fully effective. When this happened, schools' tutoring was not well targeted and not well enough connected to students' classroom learning and their particular learning needs.

The department can do more to improve schools' delivery of the initiative. The department has the information it needs to do this but has not used it to drive improvement.

What we recommended

We made 2 recommendations to the department about improving the delivery of the initiative and one recommendation about:

- adopting a staged roll-out for system-wide programs

- using the department's implementation tools to improve schools' delivery of the initiative.

Video presentation

Key facts

Note: Further information about the tutoring model is available in Appendix D.

Source: VAGO.

Our recommendations

We made 3 recommendations to address one issue. The agency has accepted all recommendations in full or in principle.

| Key issues and corresponding recommendations | Agency responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Issue: The Department of Education can do more to improve schools' delivery of the Tutor Learning Initiative | ||||

| Department of Education | 1 | Collect and analyse data on schools' tutoring model and dosage so the Department of Education understands and promotes the models and dosage that are effective for different school types and student groups (see Section 2). | Accepted | |

| 2 | Establish measurable goals for schools' performance in the Tutor Learning Initiative with processes to drive sustained improvement (see sections 2 and 3). | Accepted in principle | ||

3

| Establish practices and procedures to pilot statewide learning interventions so that the Department of Education understands:

| Accepted

| ||

What we found

This section summarises our key findings. The chapters detail our complete findings, including supporting evidence.

When reaching our conclusions, we consulted with the audited agency and considered its views. The agency’s full response is in Appendix A.

Why we did this audit

The Tutor Learning Initiative (the initiative) is receiving total funding of over $1.2 billion over 5 years. This is a significant investment to improve learning outcomes for students who need it most.

It is important to understand if the initiative is achieving this to make sure all Victorian students get the help they need to learn at their best.

Over 1,500 government schools and over 600 low-fee non-government schools have participated in the initiative each year since 2021. In this audit we looked at government schools.

The initiative’s objective

In October 2020, the Victorian Government announced the initiative to support students whose learning had been most disrupted by the COVID-19 response.

The initiative gives funding to schools for tutors to work with students and address their particular learning needs. It began in 2021 and the government has funded it until the end of 2025.

From 2023, the Department of Education (the department) shifted the initiative’s focus to support students whose literacy and numeracy skills were below the expected level for their year.

The initiative is an additional support to help students who are behind in their learning to catch up and continue learning with their peers in the classroom.

Effective tutoring

The initiative funds a model of tutoring called small group learning, where a tutor works with groups of 2 to 5 students with similar learning needs. The tutor, who must be a qualified teacher, generally works with students in regular sessions for 6 to 20 weeks.

Tutoring sessions addresses gaps in students’ knowledge or skills. Once these gaps are closed, students continue learning in the classroom with quality teaching that is adapted to their needs.

Research in Australia and overseas shows that tutoring can be highly effective to help students catch up with their learning.

| Tutoring is effective when it is … | This means that students … |

|---|---|

| timely | receive support when they need it most. |

| targeted | learn the skills they need most. |

| appropriate to school context | learn in a tutoring environment that is integrated with the way their school runs. |

| appropriate to student need | learn with approaches designed to meet their particular skills gaps. |

Our key findings

Our findings fall into 3 key areas:

| 1 | Overall, the initiative did not have a significant impact on students' learning results compared to similar non-tutored students. |

| 2 | Many schools' tutoring practices were not fully effective in ways that are targeted and appropriate to school context and student need. |

| 3 | The department can do more to improve schools' delivery of the initiative. It has the information to do this but is not using it to drive improvement. |

Key finding 1: The initiative did not have a significant impact on students' learning results compared to similar non-tutored students

Expectations of learning gain

The initiative is intended for students who begin the year behind their peers to receive tutoring and to:

- catch up with their learning

- continue learning in the classroom with their peers.

To do this, tutored students need to learn faster than they would have without tutoring and faster than their classroom peers who are not receiving tutoring.

For the initiative to be effective overall, we expect tutored students who receive tutoring should have greater learning gains than similar students who did not.

This means they will have learnt at a faster rate than their non-tutored peers and are more likely to catch up to their expected level.

No significant effect

Students who received tutoring in 2023 did not show greater learning gains than similar students who did not receive tutoring.

We looked at results for students who received tutoring compared to students who did not. We used test data from the department to measure how much students learnt in 2023 by comparing their 2022 and 2023 test scores.

When we compared similar students from each group, we found that students who received tutoring learnt less than those who did not receive tutoring.

Among disadvantaged students, there was no difference in learning gains between tutored and non-tutored students. There was also no significant difference in learning gains between tutored students in metropolitan, regional or rural Victoria.

Key finding 2: Many schools' tutoring practices in 2023 were not fully effective

Many schools did not have fully effective tutoring practices

We analysed schools' delivery of the initiative against the continuous improvement tool the department uses. This tool describes the elements of effective tutoring and uses a 4-point maturity scale to measure schools’ tutoring practices.

After having offered tutoring throughout 2021 and 2022, fewer than one-third of all government schools in 2023 had fully effective tutoring practices that were targeted, appropriate to school context and appropriate to student need.

We found primary schools generally had more effective tutoring than other school types.

Our audit focuses on schools’ tutoring practices in 2023. This is because in previous years, staff and student absences (because of COVID-19 and influenza) affected schools’ tutoring programs. Schools were also delivering most of their learning remotely in 2021.

Tutoring was timely despite workforce shortages

We found schools have generally provided tutoring in a timely way for each school term.

The department's recruitment support has been effective, particularly for schools facing challenges such as secondary and rural schools. The department also provided rural schools with additional support through its Virtual Tutor Program.

Survey data from school principals shows that teacher workforce shortages have meant schools could not always meet tutoring demand. This is particularly the case for secondary schools and primary–secondary schools.

Key finding 3: The department can do more to improve schools' delivery of the initiative

The department monitors schools' delivery

The department:

- monitors schools' delivery of the initiative

- regularly collects data from school leaders about the initiative

- evaluated the initiative in 2021 and 2022

- uses assessment data to understand students' learning gains.

The department provides support and guidance to schools and has adapted this support based on its evaluation findings.

The department’s current support is not enough to drive improvement

We examined the proportion of schools whose tutoring practices were rated as fully or partially effective in achieving student learning growth.

We found that between 2021 and 2023, the department's support and guidance had not been enough to drive sustained and significant improvement in schools’ practices.

The department has also not used its monitoring data to drive improvement in schools’ tutoring practices. It has evaluation findings about the initiative’s impact on student learning outcomes. But it has not used these findings to generate system-wide improvements.

For the initiative to improve learning outcomes for students, the department must make a sustained effort to understand what works, why it works and how to support all schools to be fully effective.

1. Impact of the initiative

Overall, the initiative did not sufficiently improve students' learning results compared to similar non-tutored students.

Understanding improvements in students' learning

Expected learning benefits

The department wants students who receive tutoring to improve their literacy and numeracy skills to help them succeed in the general classroom.

All students learn and increase their skills over the school year. But not all students begin the year at the same level.

If all students learn at similar rates, those who are behind at the start of the year will still be behind at the end. And they may move further behind as the class moves on.

The initiative offers tutoring to these students to help them catch up to their expected level. To do this, they need to learn faster than they would have without tutoring and faster than their non-tutored classroom peers.

Measuring learning benefits

Teachers measure students' learning in different ways throughout the school year. The type of assessment a teacher uses depend on the student's age, stage of learning and other factors, such as whether English is an additional language for the student or if they have a disability.

But using different tests makes it difficult to compare students' learning and measure how they benefit from tutoring.

To address this, the department made 2 tests available to all government schools. They are the:

- Progressive Achievement Test – Reading (PAT Reading)

- Progressive Achievement Test – Mathematics (PAT Maths).

The department encourages schools to use these tests at the beginning and end of the school year for years 3 to 10. It collects the test data and can analyse students' learning gains.

While these tests do not cover all students receiving tutoring, they do make it possible to measure learning gain for most students participating in the initiative in each year.

Our analysis

We used PAT Reading and PAT Maths data for 2021 to 2023 to understand students' learning gains.

The results we discuss in this report are for students who received tutoring in 2023. This is because by then, schools have had 2 full years to implement and refine their tutoring models and meet students' needs. We note that schools’ delivery in 2021 and 2022 was affected by COVID-19 and influenza.

We assessed how much students who received tutoring had learnt during the year. We did this in 3 ways using unmatched and matched analysis.

| Unmatched analysis | We compared the learning gains for all tutored students with all non-tutored students. |

| Matched analysis | We grouped tutored students with non-tutored students with similar test scores and characteristics, such as disadvantage and where they lived. We compared the learning gains of tutored and non-tutored students who had the same test scores at the end of 2022. |

For the initiative to be effective overall, we would expect students who received tutoring to have greater learning gains than similar students who did not. This would mean they will have learnt more quickly than their peers and be more likely to catch up to their expected literacy and numeracy levels.

This means we relied on matched analysis to assess the impact of tutoring on students.

Further information

For in-depth information about the methodologies we used and students’ learning gains, see Appendix E and Appendix F.

The initiative did not substantially improve students' learning results

Tutoring had no strong impact on students' learning results

Students who received tutoring in 2023 did not show more learning gains than similar students who did not receive tutoring. This means tutored students remained behind their classroom peers at the end of 2023.

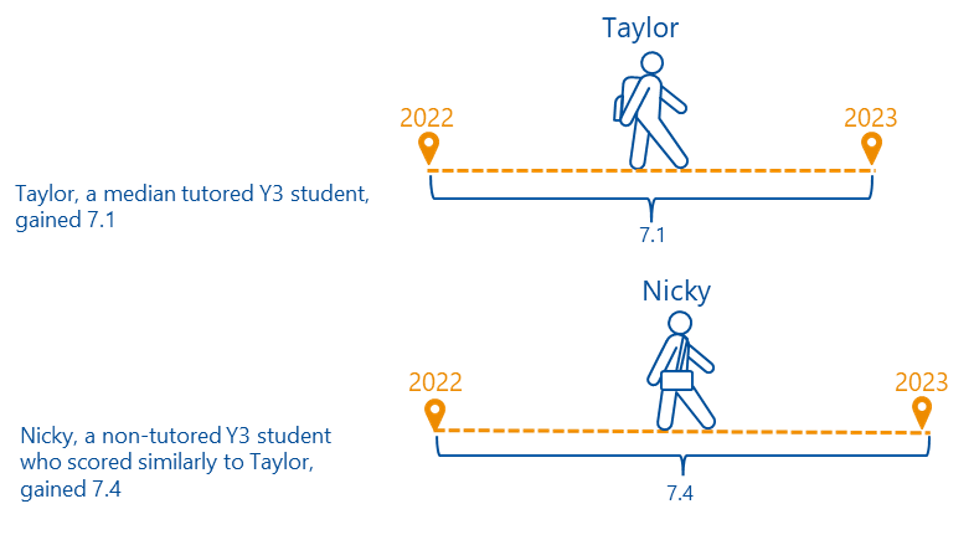

Figure 1 shows the case of year 3 reading. The reading score of a median tutored year 3 student increased by 7.1 over 2023. In this illustration we call this student Taylor.

A median year 3 student who had a similar reading score at the end of 2022 but did not receive tutoring gained 7.4 over the same period. We call this student Nicky.

If the initiative was effective, Taylor's learning gain should be more than Nicky's – not the other way around.

Figure 1: Reading learning gains in year 3 for median tutored and non-tutored students with similar prior scores

Note: This example reflects the highest level of learning gain for tutored students VAGO observed across all year levels and learning focus.

Source: VAGO, using department data.

Other comparisons show no significant impact

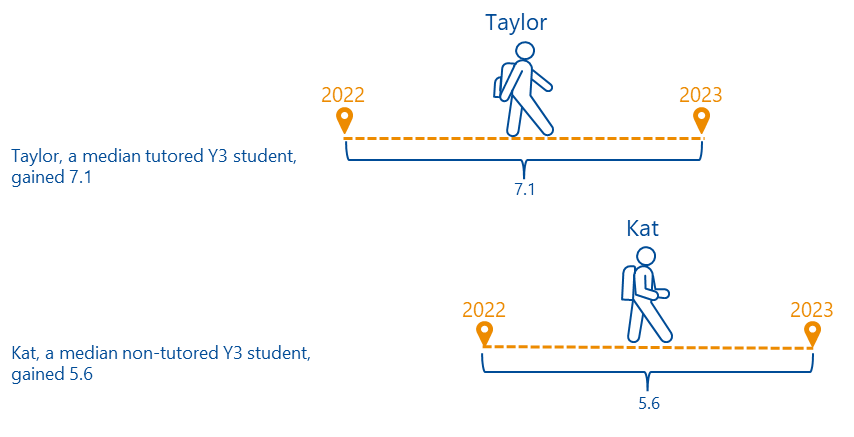

Another approach is to compare the scores of the median student who received tutoring in 2023 with the median student who did not, without considering their prior scores at the end of 2022.

Figure 2 shows this comparison, again using the case of year 3 reading.

We call the median student who did not receive tutoring Kat. Kat's learning gain over 2023 was 5.6, compared to the median tutored student Taylor's learning gain of 7.1.

This comparison seems to show that tutoring was effective. But it does not consider the fact that Kat's score at the end of 2022 was higher than Taylor's.

Figure 2: Reading learning gains in year 3 for median tutored and non-tutored students

Source: VAGO, using department data.

We used the comparison between similarly skilled students to assess the initiative’s effectiveness (Taylor compared to Nicky, as shown in Figure 1). This is because we wanted to accurately quantify the initiative’s effect by removing the impacts of prior scores.

Within the limitations of the data, we attempted to address this by creating a comparable group who did not participate in the initiative.

But whichever comparison we use, Taylor remains behind his peers at the end of 2023.

The initiative has not achieved its intended outcome, which is for tutored students to improve their literacy and numeracy skills to succeed in the general classroom.

The learning gains shown in figures 1 and 2 are based on the year 3 reading results. According to the available data (years 3 to 10), year 3 students had the highest learning gains of all year levels in both reading and maths, for tutored and non-tutored students. From year 3 onward, students’ learning generally slowed whether they received tutoring or not.

For a detailed breakdown of students’ learning gains in all year levels in reading and maths, see Appendix F, figures F1 and F2.

Effect on students with different characteristics

We looked at whether the initiative was more effective for some groups of students than others.

Disadvantaged students who received tutoring did not have more learning gain than disadvantaged students who did not receive tutoring.

There was also no significant difference in learning gains between tutored students in metropolitan, regional or rural Victoria.

For a detailed breakdown of learning gains for disadvantaged students in all year levels, see Appendix F, figures F3 and F4.

Limitations to analysis

Both this audit and the department's analysis have limitations that may influence estimates of the initiative's impact. These limitations (see Figure 3) affect how certain we can be about the effect of tutoring on each student who participated in the initiative.

Figure 3: Limitations in data that may affect results

| Limitation | Impact on understanding students' learning gain |

|---|---|

| Unknown or unmeasured factors | It is not possible to know or accurately measure all the factors that affected each student's learning. |

| Limited data on the type of tutoring students received | The department's data shows if a student participated in tutoring. But it does not show if the student attended one or all tutoring sessions, or which tutoring method was used. |

| Support from other programs | Students may have participated in other programs to support their learning, whether at school or at home. If they have, we could not attribute their learning gain only to the initiative. |

Source: VAGO.

Our analysis still provides a reliable understanding of how effective the initiative is overall.

But there is not enough data to fully understand how and where the initiative is working well and which tutoring model works best for different students' learning needs.

The initiative improved student engagement but it did not improve school attendance

Expected engagement benefits

The department intends for students participating in the initiative to engage more with education. It measures this through:

- school leader and tutor reports of student learning engagement

- school attendance data.

Through regular surveys, school leaders and tutors have told the department that they see students becoming more engaged in their learning because of the initiative.

No effect on student attendance

We analysed student absence and demographic data to estimate the effect of tutoring on student absences.

Our baseline measure was the total number of absence days for all students in 2022. We looked at the same data for 2023 and checked whether there was a difference between tutored and non-tutored students.

We did not find any consistent, discernible effect the initiative had on tutored students’ absence days in 2023.

2. Implementing the initiative

In 2023, most schools delivered tutoring in a timely way but did not have fully effective tutoring practices. Primary schools were more likely to be better at delivering the initiative than secondary schools.

The department supports schools to deliver the initiative

What effective tutoring looks like

Support for school's tutoring models

The department is responsible for establishing, managing, monitoring and reporting on the initiative.

Schools are responsible for delivering the initiative to their students within the department’s guidelines. They have the flexibility to design a model that works best for their school setting and students' needs.

The department supports schools through:

- policy and guidance

- staffing resources

- funding

- professional practice guides.

This support includes information about:

- tutor arrangements

- student selection

- program design

- assessment

- monitoring requirements.

Schools have access to department staff who help schools design and deliver the initiative.

Further information

For in-depth background information, see Appendix D.

How schools delivered the initiative in 2023

Framework for monitoring schools’ delivery

The department has designed a framework to help schools to reflect on, self-evaluate and track their progress in delivering the initiative. It calls this framework the Tutor Learning Initiative Implementation Continua (the framework).

This framework describes what effective tutoring practice looks like across 6 dimensions.

This information, together with the department's Tutor Practice Guide, helps schools design and deliver a tutoring model for their school community.

The department uses the framework to rate schools’ progress in each of its dimensions on a 4-point scale:

- emerging

- evolving

- embedding

- excelling.

School leaders, teachers and tutors may work with department staff to reflect on the schools' tutoring model and how it supports student's learning. They then identify where and how to improve the tutoring. Appendix G includes the framework’s tutoring dimensions and 4-point scale.

We assessed schools' delivery based on the framework’s data

Department staff record the dimension ratings of schools twice per year. The department collects this data in its School Evaluation and Evidence Database.

This means schools and the department have the data they need to understand areas of effective practice and areas for improvement. The department does not set benchmarks for schools' performance against the framework.

We used this data to understand how well schools delivered the initiative in 2023 based on 3 elements of effective tutoring practice.

| We assess if tutoring is … | To achieve this, schools need to … | This is aligned with the framework dimension(s) … |

|---|---|---|

| targeted | select students for the right type of tutoring | student selection and focus area |

| appropriate to school context | lead effective tutoring practice across the whole school | school leadership |

| appropriate to student need | design a tutoring model that responds to students' learning needs and monitors their learning growth | tutoring model and dosage |

| collaboration, curriculum and practice | ||

| monitoring learning growth | ||

| student voice. |

For the fourth element of timely access to tutoring, we tested schools' ability to offer tutoring by week 6 of each term.

Use of the framework’s rating scale

In this audit, we based our analysis of the effectiveness of schools' tutoring practices on the framework's rating scale.

We used schools' ratings in semester 1, 2023 as a snapshot of how they are delivering the initiative.

| For each dimension, we consider a school to have … | If the dimension is rated as … | Based on the department's instruction that … |

|---|---|---|

| fully effective practices | excelling | 'excelling' is associated with sustained learning gain for most students and the school uses a well-developed Response to Intervention model to support students into and out of the initiative. |

| partially effective practices | embedding | 'embedding' is associated with some learning gain for some students and there is some evidence the school uses a Response to Intervention model. |

| insufficient practice | emerging or evolving | ‘emerging’ and ‘evolving’ are not associated with student learning gain or that the school uses a Response to Intervention model. |

Response to Intervention model

In the Response to Intervention model, each tutoring session addresses gaps in students' knowledge or skills. Once these gaps are closed, students continue learning in the classroom with quality teaching practice that is adapted to their needs.

The Response to Intervention model also requires schools to offer students support from a range of learning or behaviour programs at a level that best responds to their individual needs.

Expectations of schools' delivery by 2023

For students to get the learning support they need, as many schools as possible should be practicing effective tutoring.

When schools excel across all or most dimensions, the department and other schools can learn about what worked well in different circumstances. Schools rated as 'embedding' can use the framework to identify what they can change to better help more students.

We do not expect to see all schools rated as 'excelling'. But we do expect most schools to be rated as either 'excelling' or ‘embedding’. In 2023, this was achieved on all dimensions of tutoring except for one.

We keep these categories separate because there is significant variation in performance across the dimensions. This is particularly the case for the critical elements of tutoring model and dosage, collaboration curriculum and practice, and monitoring learning growth.

There is a material difference between ‘excelling’ and ‘embedding’ with regards to the impact on students’ learning. For this reason, this report distinguishes between the 2.

Constraints on schools’ delivery

This audit focuses on schools' delivery of the initiative in 2023. This is because in previous years, staff and student absences (because of COVID-19 and influenza) affected schools’ tutoring programs. Schools were also delivering most of their learning remotely in 2021.

The department told us schools had significant staff shortages throughout 2023. This likely affected how schools delivered the initiative.

Many schools' tutoring practices in 2023 were not fully effective

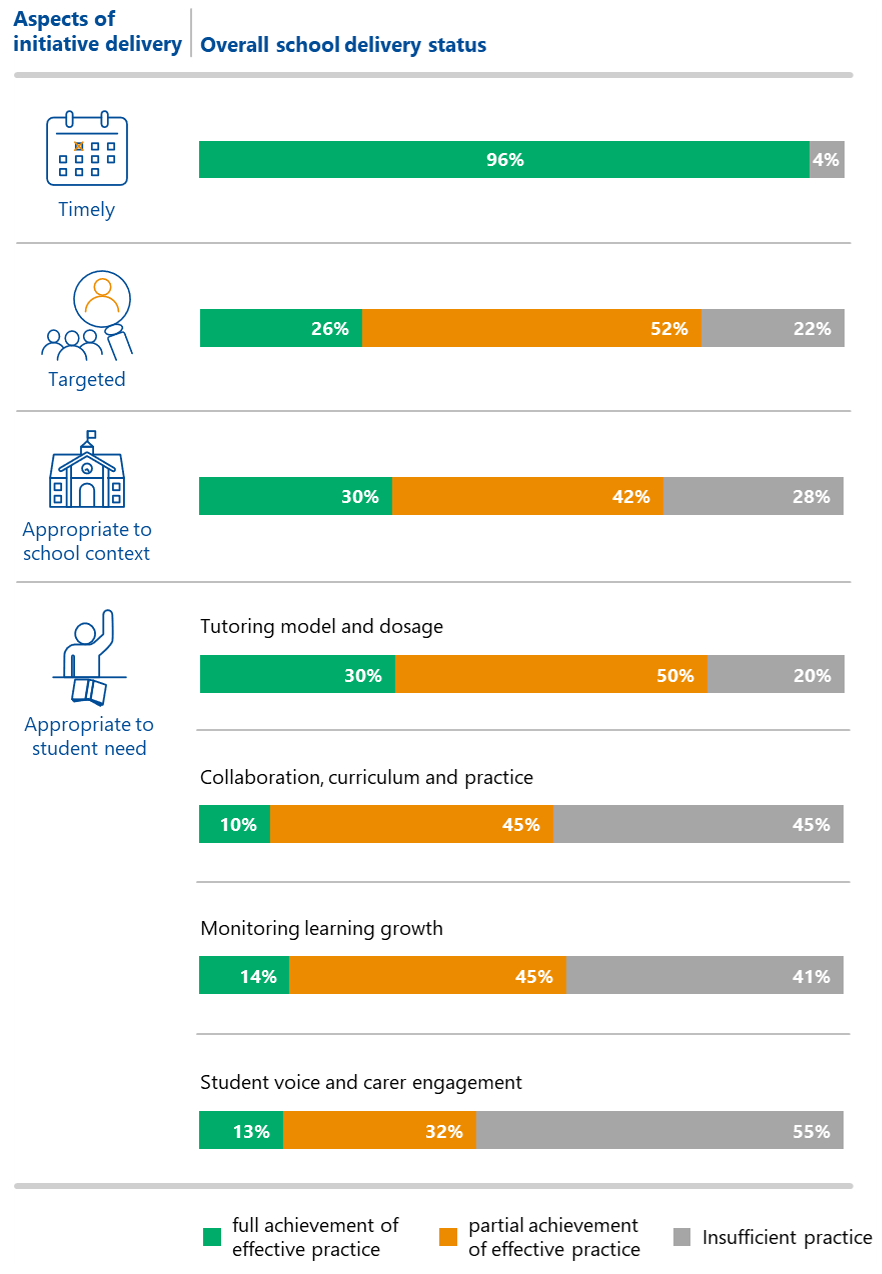

Nearly all schools delivered timely tutoring in 2023, despite workforce shortages. But fewer than one-third of all schools had fully effective tutoring practices that were:

- targeted

- appropriate to school context

- appropriate to student need.

The department expected schools to embed tutoring as an effective, ongoing learning support. But the tutoring model and dosage dimension results suggest that many schools may not have capacity to do this.

Figure 4 shows our analysis of schools' ratings from semester 1, 2023.

Figure 4: Schools' delivery of the initiative in 2023

Source: VAGO, using department data.

Tutoring was timely despite workforce shortage

Tutoring needs to be timely for students who fall behind in their learning to catch up. We found that schools consistently deliver tutoring in a timely way. The department's support for recruitment is effective.

Over 95 per cent of schools offered tutoring by week 6 of each term in 2022 and 2023, across all types of schools and all parts of Victoria. This was despite a teacher and tutor shortage across Victoria and Australia.

Surveys of school principals show the workforce was not necessarily enough to meet tutoring demand.

This is especially the case for secondary schools and primary–secondary schools. Much higher proportions of these schools reported workforce shortages as a major issue compared to primary schools.

| In the term 2, 2023 survey … | Of principals from … | |

|---|---|---|

| 50 per cent | secondary schools | reported tutor supply as one of the largest barriers to delivering the initiative. |

| 57 per cent | primary–secondary schools | |

| 14 per cent | primary schools | |

Lower tutor availability likely affects the tutoring models and dosage schools choose. For example, it may mean they choose less effective models.

Tutoring was not well targeted

The 'targeted' element of effective tutoring relates to student selection and learning focus. This is essential to the initiative because the department expects schools to target those most in need of support and to choose the right focus for them.

In 2023, targeted tutoring:

| Was … | By … |

|---|---|

| fully effective | 25 per cent of schools. |

| partially effective | 52 per cent of schools. |

| insufficient | 23 per cent of schools. |

School type plays a role in this element of tutoring. For example, a higher proportion of primary schools (29 per cent) were fully effective in this element of the initiative than other school types (17 per cent for secondary schools and 18 per cent for primary–secondary schools).

Schools did not always integrate tutoring

The ‘appropriate to school context' element of tutoring relates to integrating tutoring. This is tutoring that establishes and links teaching practices within the school so:

- tutoring leads to student learning gain

- staff are proactive and plan for successful practice

- improvement is ongoing.

In 2023, integrated tutoring:

| Was … | By … |

|---|---|

| fully effective | 30 per cent of schools. |

| partially effective | 42 per cent of schools. |

| insufficient | 28 per cent of schools. |

We found 34 per cent of primary schools were fully effective in integrating tutoring. This is compared to 19 per cent of secondary schools and 18 per cent primary–secondary schools.

Primary schools also outperformed other school types in in being partially effective in this tutoring element.

Tutoring did not always support students' learning needs

The appropriate to student need element of tutoring relates to designing a tutoring program that responds to students' learning needs. This includes:

- tutoring model and dosage

- collaboration, curriculum and practice

- monitoring learning growth

- student voice and carer engagement.

Overall, in 2023, primary schools were more likely than other school types to have fully effective tutoring practices that meet student need.

We found 35 per cent of primary schools had fully effective practices for tutoring model and dosage. But fewer were fully effective against collaboration, curriculum and practice (12 per cent) and monitoring learning growth (17 per cent).

Very few secondary schools had fully effective practices that met student need. For tutoring model and dosage, only 12 per cent of secondary schools had fully effective practices. The proportion is even lower for the other dimensions, with only 6 per cent fully delivering against collaboration, curriculum and practice, and monitoring learning growth.

For both primary and secondary schools, only 13 per cent had fully effective practices for the student voice element.

Key barriers identified by principals

The department gives principal check-in surveys to all government schools. The surveys ask principals to choose up to 5 challenges they consider the largest barriers to the initiative.

In 2023, 41 per cent of principals said one of the largest barriers was student attendance. This is where students are present at school but do not attend tutoring. This affected regional centre schools (48 per cent) slightly more than urban schools (38 per cent) and rural schools (43 per cent).

Student absence also presented significant challenges. In 2023, 31 per cent of responding principals cited student absence (not due to COVID-19) was one of the largest barriers. And 11 per cent said student absence related to COVID-19.

Absence related to COVID-19 affected rural schools (19 per cent) more than urban schools (7 per cent) and regional centre schools (11 per cent).

In 2023, 7 per cent of principals said student engagement was a barrier. It affected secondary schools (20 per cent) more than primary schools (3 per cent) and primary–secondary schools (11 per cent).

3. Improving the initiative

The department is not improving schools' delivery of the initiative. It has the tools and information to do this, but schools have not substantially improved since 2021.

The department monitors schools' delivery of the initiative

Support for continuous improvement

The department intends for its support and guidance to continuously improve schools' delivery of the initiative. It designed the framework for department staff and schools to reflect on tutoring models and identify where schools can improve their tutoring practices.

Between semester 2, 2021 and the end of 2023, department staff have worked with schools to assess and record their improvement progress in the department's School Evaluation and Evidence Database. We have used this data to understand how schools' delivery of the initiative has changed since 2021.

The department has taken some steps to respond to schools' needs

In 2021 and 2022, the department conducted evaluations that included schools' experiences of the initiative. These evaluations showed that school leaders, teachers and tutors highly valued the initiative and wanted it to continue. They also identified opportunities for the department to refine its support and guidance to make the initiative more effective.

The department adapted its support and guidance after each evaluation.

| In response to … | The department… |

|---|---|

schools finding it difficult to design an effective tutoring model, especially:

| published learnings about ‘what works’ when implementing the initiative in 2022 to support school leaders and tutors.

|

| tutor staffing challenges reducing delivery in some schools | set up a Virtual Tutor Program in 2022. This involved making 6 Virtual Tutor Learning Specialists available to support schools struggling with tutor recruitment. |

| significant differences in how schools selected students for the initiative | more clearly described its intended tutoring participants. In 2023, it emphasised that students being at or below expected levels in literacy and numeracy should be the main factor schools consider when choosing initiative participants. |

Schools' delivery of the initiative has not significantly improved

Delivery of the initiative is not improving

We examined the proportion of schools rated as having fully or partially effective tutoring practices.

We found that between 2021 and 2023, the department's support and guidance had not been enough to drive sustained and significant improvement in schools’ practices.

When we examined the data, we found that most of the performance improvement occurred between late 2021 and early 2022. But there has been little change in performance since.

Improvement rate varies by school type

Primary schools are more likely to have improved since 2021 and secondary schools are more likely to have declined.

Figure 5 shows the changes in schools' performance between 2021 and 2023 and how this varies across primary, secondary and primary–secondary schools.

Primary schools have improved across all dimensions. Their rates of improvement are not higher than 9 per cent. Primary–secondary schools have improved somewhat against most of the elements.

Secondary schools' performance has declined against all dimensions, except student voice and carer engagement.

Across all school types, there was no significant increase in schools that had partially effective practices. We did find there was an increase in all schools having partially effective practices for student voice and carer engagement.

Figure 5: Change in proportion of schools fully delivering the initiative from 2021 to 2023 by school type

| Dimension | Primary schools | Secondary schools | Primary–secondary schools | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Targeted | 8% | −4% | 0% | |

Appropriate to school context | 9% | −6% | 7% | |

Appropriate to student needs | tutoring model and dosage | 8% | −6% | 9% |

| collaboration, curriculum and planning | 4% | −3% | 2% | |

| monitoring learning growth | 8% | −8% | 0% | |

| student voice and carer engagement | 3% | 4% | 2% | |

Source: VAGO, using department data.

The department can do more to drive improvement

The department collects and uses data about the initiative

The department has the staff, tools and data it can use to make the initiative more effective.

The framework is a useful tool to understand schools' progress in improving their practices and identify schools that need more support.

The department has a database to record implementation maturity over time.

The department collects data on schools' experiences of the initiative through regular surveys of school leaders. It collects test data from schools and undertakes complex analysis to understand student learning outcomes.

The department has also commissioned or conducted evaluations of the initiative in its first 2 years. These evaluations brought together all this data to identify and understand how schools were implementing the initiative and its effect on student learning.

This means the department has a sound framework to continuously improve schools' delivery of the initiative.

Changes to support and guidance have not improved delivery

The department improved its support and guidance in response to the initiative’s first evaluation. This appears to be associated with improvement in schools' practices from late 2021 to mid-2022.

But when the initiative’s second evaluation found it was not significantly increasing learning for most students, the department made only minor modifications in 2023.

We also found that changes the department made to its student selection guidance did not alter schools’ approaches.

The department emphasised that schools should prioritise students with literacy and numeracy below expected levels. But the proportion of these students receiving tutoring did not change between 2022 and 2023.

Schools need more delivery support

The department needs to give schools more specific and specialised support for them to deliver the initiative as planned.

The department intends that schools deliver the initiative within a Response to Intervention model. By definition, tutoring is an intervention that addresses learning needs the general classroom cannot fully meet.

It is apparent from our analysis that, for most schools, this kind of intervention is not business as usual.

It is an additional and particular type of teaching that requires expertise in all elements, from selecting students and designing a tutoring model, to monitoring students' learning growth and integrating that learning with the general classroom.

For the initiative to succeed and improve student learning outcomes, the department must make a sustained effort to understand what works, why it works and how to support all schools to fully deliver the initiative.

Moving from monitoring to accountability

The department needs to hold schools accountable for improving their delivery of the initiative.

The department has a responsibility to improve the school system’s performance so large-scale intervention programs achieve their objectives.

The department has accountability measures in place for schools' funding and recruitment for the initiative. It collects and analyses dimension implementation data. But it has not used this to drive improvement within schools.

It has evaluated the effect of the initiative on student learning outcomes. But it has not used these findings to significantly change its support for schools.

We understand the department rolled out the initiative quickly in response to students' learning support needs during the COVID-19 response and that schools were still affected in 2022. However, the initiative has been in place for 3 years with a total commitment of over $1.2 billion and it does not show evidence of sustained improvement over time, either in schools' practices or student learning outcomes.

Trialling and improving system-wide programs

The department should reconsider the way it evaluates and improves system-wide interventions.

It needs to use relevant and evidence-based measures for success focused on students’ learning and apply these throughout the life of the program. The department needs to understand how different factors influence the impact of these programs on students. These factors include:

- school type

- students' prior achievement and engagement

- other interventions

- school leadership

- data literacy

- classroom teaching

- cultural and socioeconomic contexts.

The department has demonstrated it can plan and stage system-wide interventions so it understands early effects and takes steps to continuously improve implementation. It is doing this with its rollout of Disability Inclusion, which we examined in 2023.

The department has other options available for early understanding of its programs’ effectiveness. This includes randomised control trials or pilot programs, which would allow the department to try interventions in particular circumstances, measure their effects, assess their benefits and consider how to effectively scale them up for the whole of Victoria.

Appendix A: Submissions and comments

Download a PDF copy of Appendix A: Submissions and comments.

Appendix B: Abbreviations, acronyms and glossary

Download a PDF copy of Appendix B: Abbreviations, acronyms and glossary.

Appendix C: Audit scope and method

Download a PDF copy of Appendix C: Audit scope and method.

Appendix D: Audit background

Appendix E: Methodologies for comparing student learning growth

Download a PDF copy of Appendix E: Methodologies for comparing student learning growth.

Download Appendix E: Methodologies for comparing student learning growth

Appendix F: Comparison of learning gains

Download a PDF copy of Appendix F: Comparison of learning gains.

Appendix G: Implementation framework

Download a PDF copy of Appendix G: Implementation framework.