Efficiency and Effectiveness of Hospital Services: Emergency Care

Overview

Longer stays in an emergency department (ED) are associated with poorer patient outcomes. Long waits to see emergency staff can discourage people who need care from waiting and may lead to reduced morale among ED staff.

In 2015, the Department of Health & Human Services (the department) set a target for 81 per cent of patients who present at public hospital EDs to be admitted to the hospital for treatment, to be referred to another hospital for treatment, or to be discharged within four hours. The health services and the Minister for Health agreed to this target in their annual Statement of Priorities. This new target replaces the ambitious previous national target of having 90 per cent of ED patients discharged home or admitted for further treatment within four hours by 2015.

We assessed whether public hospitals are managing EDs efficiently and effectively. We compared the efficiency and effectiveness of all Victorian public EDs. We looked at four hospitals in closer detail to understand why performance varies, and we also assessed how the department supports and oversees emergency care.

The report includes a series of recommendations for health services and the department.

Efficiency and Effectiveness of Hospital Services: Emergency Care: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER October 2016

PP No 217, Session 2014–16

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Efficiency and Effectiveness of Hospital Services: Emergency Care.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

26 October 2016

Audit overview

Longer stays in an emergency department (ED) are associated with poorer patient outcomes. Long waits to see emergency staff can discourage people who need care from waiting and may lead to reduced morale among ED staff.

Efficient EDs help people to get the care they need in a time frame that suits the urgency of the situation. Effective emergency care is coordinated so that patients have access to the staff and services required for accurate diagnosis and treatment.

ED visits can result in lower out-of-pocket expenses for patients than visits to a specialist following referral by a general practitioner. This, coupled with population growth, is leading to more patients presenting at EDs.

In 2015, the Department of Health & Human Services (the department) set a target of 81 per cent of patients who present at public hospital EDs to be admitted to the hospital for treatment, referred to another hospital for treatment, or discharged within four hours. The health services and the Minister for Health agreed to this target in their annual Statement of Priorities. This new target replaces the ambitious previous national target of having 90 per cent of ED patients discharged home or admitted for further treatment within four hours by 2015.

We assessed whether public hospitals are managing EDs efficiently and effectively. We compared the efficiency and effectiveness of all Victorian public EDs. We looked at four hospitals in closer detail to understand why performance varies, and we also assessed how the department supports and oversees emergency care.

Conclusion

During the past four years, public hospitals have reduced the average length of stay for ED patients, despite a rise in the volume and complexity of patients presenting to EDs.

A common theme in hospitals whose performance remained the same or improved between 2010–11 and 2014–15 is effective leadership to ensure the whole hospital is accountable for managing demand in the ED. Strong direction and a united approach to ED care helped patients to access in-patient wards faster. Early decision-making by senior staff, good patient discharge planning, and a commitment to removing barriers between the ED and in-patient wards help to improve the flow of patients through the hospital. These approaches to managing EDs are not new, but they require considerable staff engagement and commitment to become embedded in daily routines.

Good performance is also associated with admitting patients to a short-stay unit (SSU)—a facility used for further observing and assessing patients. However, four hospitals admit to using SSUs for purposes contrary to the department's guidelines, and 17 hospitals had patients in SSUs for more than 48 hours in 2013−14. There is a risk that short-stay admissions can be used to mask long waiting times in ED.

The average length of stay within an ED varies by the triage category. As could be reasonably expected, those patients categorised as 'urgent' on average stay longer in an ED than less urgent patients. Hospitals have improved their efficiency in treating and discharging less urgent patients, but for urgent patients improvements have been slower. Sometimes the length of stay for patients who need to be admitted for further treatment is protracted because there are no in-patient beds available in wards.

The department has not sufficiently monitored ED performance and has not held hospitals to account for under performance. Few hospitals meet the target of 81 per cent of presentations discharged or admitted within four hours, as set out in the Statement of Priorities.

The performance data the department relies on has weaknesses due to inaccurate recording of patient re-presentations to ED. Its performance measures for effectiveness lack quality and safety indicators, and its approach to managing poor hospital performance has been, until recently, informal and insufficiently documented.

The strength of departmental monitoring has not been commensurate with the serious risk of adverse patient outcomes that could occur through poor ED performance. The department recognises this and we have observed that the department has taken steps to improve its performance framework, including strengthening how it monitors EDs that do not perform well.

Findings

Uneven gains in efficiency

In the four years to June 2015, the proportion of patients with a length of stay of less than four hours in emergency care at a Victorian public hospital has improved from 62 per cent to 69 per cent. We examined 39 of the 40 Victorian public hospitals that reported emergency data. In 2014–15, only 13 of the 39 hospitals met the target of 81 per cent of presentations having a length of stay of less than four hours, as set out in the Statement of Priorities. Although the rate of improvement varied widely between hospitals, efficiency gains were common in lower triage categories—patients with less serious symptoms. The average length of stay for urgent patients—triage category 3—has improved more slowly, averaging from four to six hours, compared with 2.9 hours for patients typically categorised as less urgent, who are discharged home.

Hospitals that performed better against the four-hour target were more likely to admit ED patients to an SSU. The department has guidelines on how SSUs should be used—for patients who require observational care for up to 24 hours—but hospitals did not routinely follow these guidelines. Staff from four EDs said that use of SSUs varied from the guidelines. In 2013–14, 17 hospitals with SSUs had patients staying for over 48 hours. Two EDs felt that 48 hours was an appropriate length of stay. In making these decisions, clinicians considered the comfort of the patient, the availability of beds in the ward and ED resources. The department does not oversee these practices.

We did not see any evidence to indicate that hospitals use SSUs to manipulate their ED length-of-stay performance, but the department's lack of oversight increases the risk of such manipulation.

Effectiveness

The current indicators set by the department do not fully capture the effectiveness of ED care in hospitals. This limits our ability to make a conclusive assessment of ED effectiveness.

A new measure that hospitals will report to the department in 2016–17 is the rate of patients re‑presenting after discharge from the ED. We found that most hospitals had an acceptable rate of 6 per cent of re-presentations within 48 hours. However, measuring re‑presentations is of limited use as an effectiveness measure because hospitals record data inconsistently. Hospitals also do not consistently record when re‑presentations are 'planned' (patients who have been instructed to return to the ED to access care that was not available when they first presented). Therefore, the data on re-presentation rates does not provide a complete picture.

Oversight and support

The department is responsible for overseeing and validating the emergency data that is used in hospitals' performance reports. The department tracks how well hospitals meet the indicators described in the annual Statement of Priorities. Hospitals also receive a performance assessment score based on a range of indicators, including emergency care. The department uses the score to work out how intensively to monitor hospitals.

This emergency data captures critical times in patients' journeys to calculate performance scores on a range of ED indicators, such as the time it takes to be triaged, and the time patients wait before being seen by a doctor, nurse or mental health practitioner. All of the hospitals in the audit sample used the department's data and internal data to understand daily demand and patient flow through the hospital.

Despite weaknesses in re-presentation data and the department being slow to address other known flaws in the dataset, the department relies on this information to assess how hospitals perform against indicators in their Statement of Priorities.

The department puts hospitals with a low overall performance score on phases known as 'performance watch' or 'intensive monitoring'. However, the department's approach to supporting these hospitals was poorly documented. As a result, we were unable to assess whether the department's support led to improvements at these hospitals. The department appears to have addressed this matter—its oversight approach for 2016–17 requires hospitals to record their proposed corrective actions to improve performance. However, it is too soon for us to judge the effectiveness of this new approach.

Recommendations

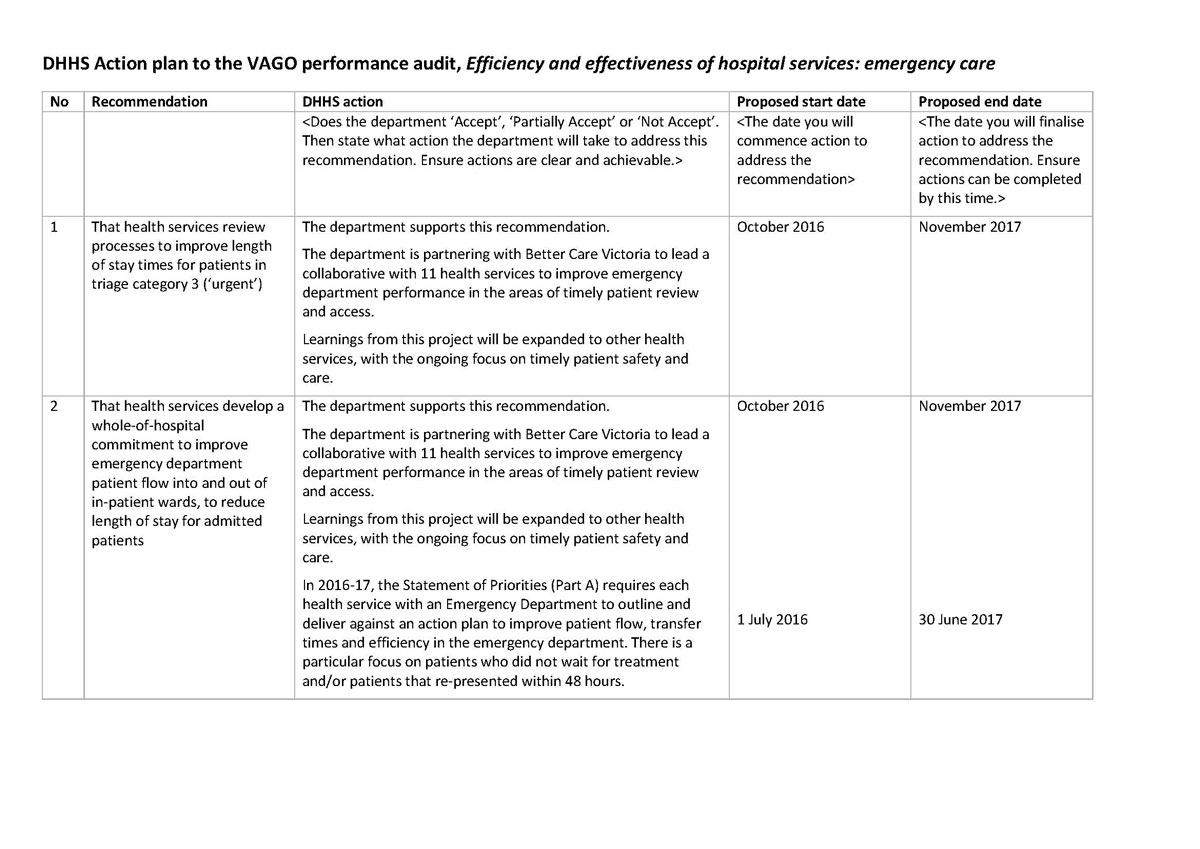

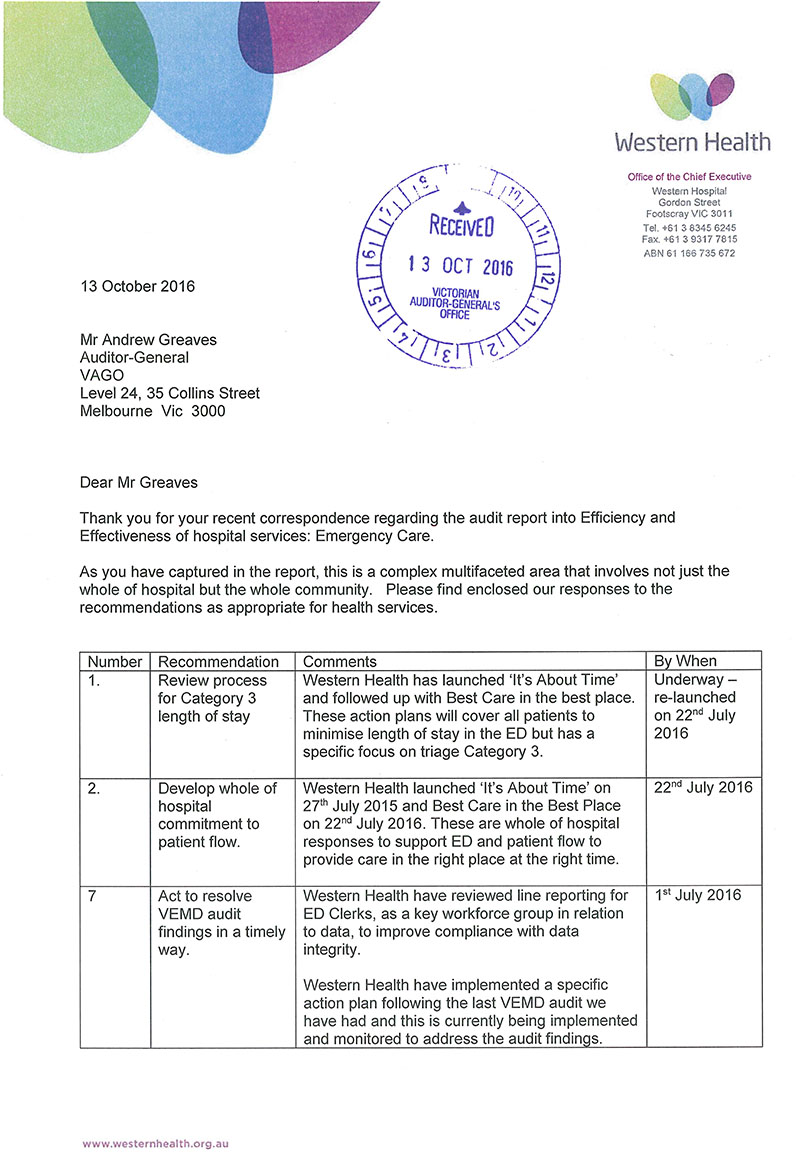

We recommend that health services:

- review processes to improve length-of-stay times for patients in triage category 3 ('urgent') (see Section 2.5)

- develop a whole-of-hospital commitment to improve emergency department patient flow into and out of in‑patient wards, to reduce length of stay for admitted patients (see Section 2.3.1)

- act to resolve Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset audit findings in a timely way (see Section 4.4.1).

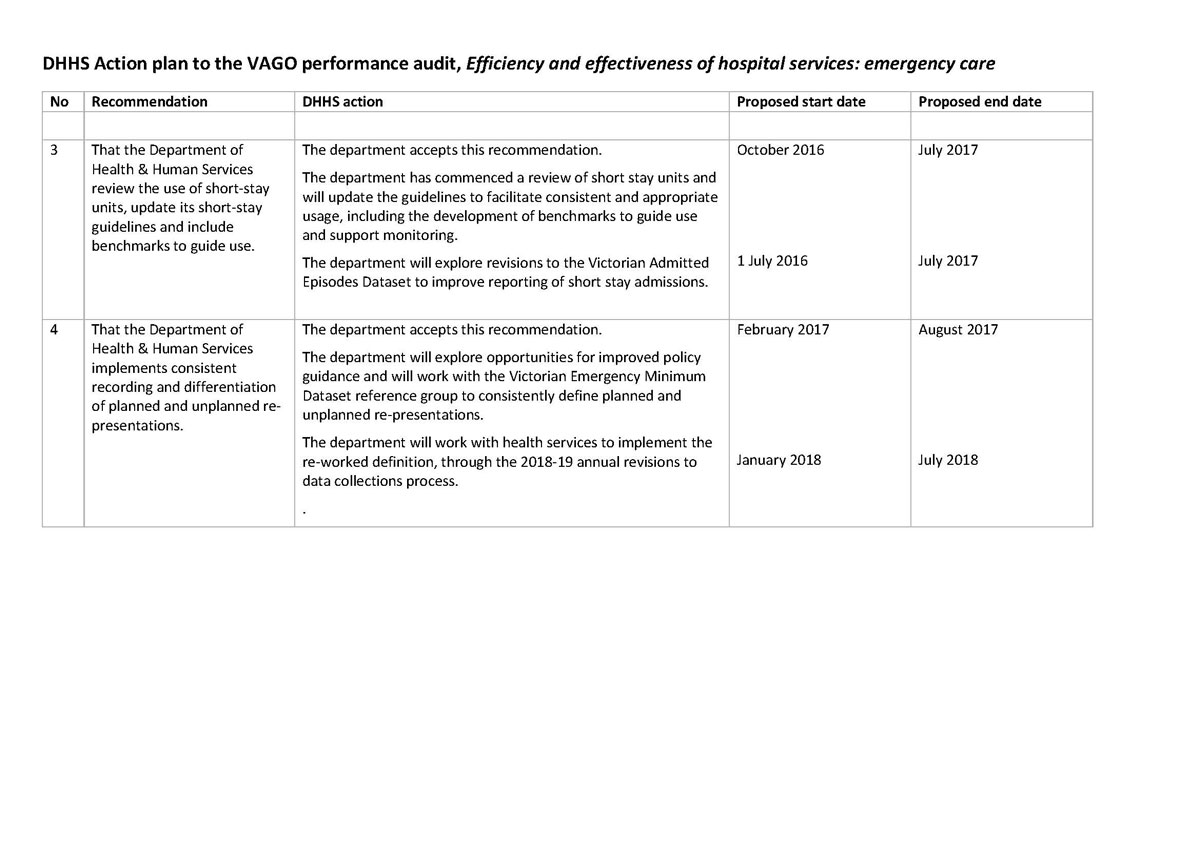

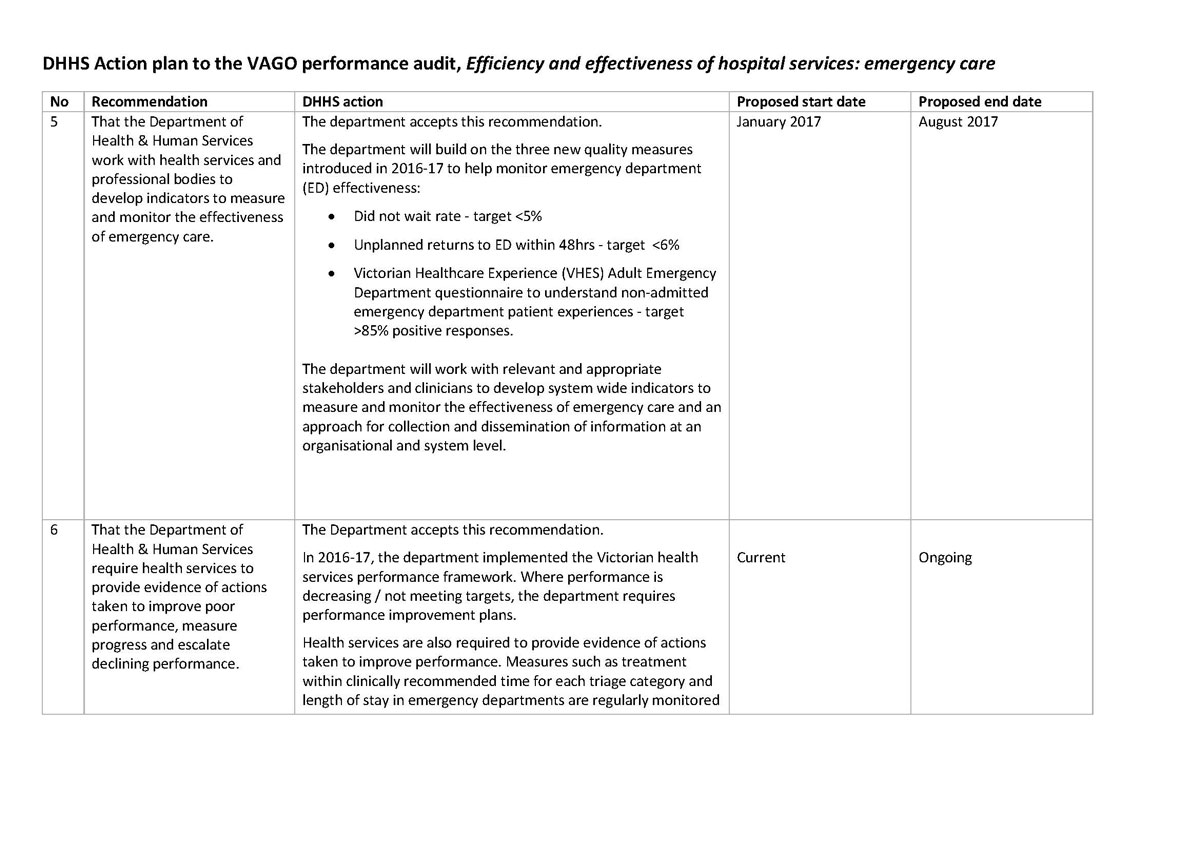

We recommend that the Department of Health & Human Services:

- review the use of short-stay units, update its short-stay guidelines and include benchmarks to guide use (see Section 2.4)

- implement consistent recording and differentiation of planned and unplanned re-presentations (see Section 3.2)

- work with health services and professional bodies to develop indicators to measure and monitor the effectiveness of emergency care (see Section 3.3)

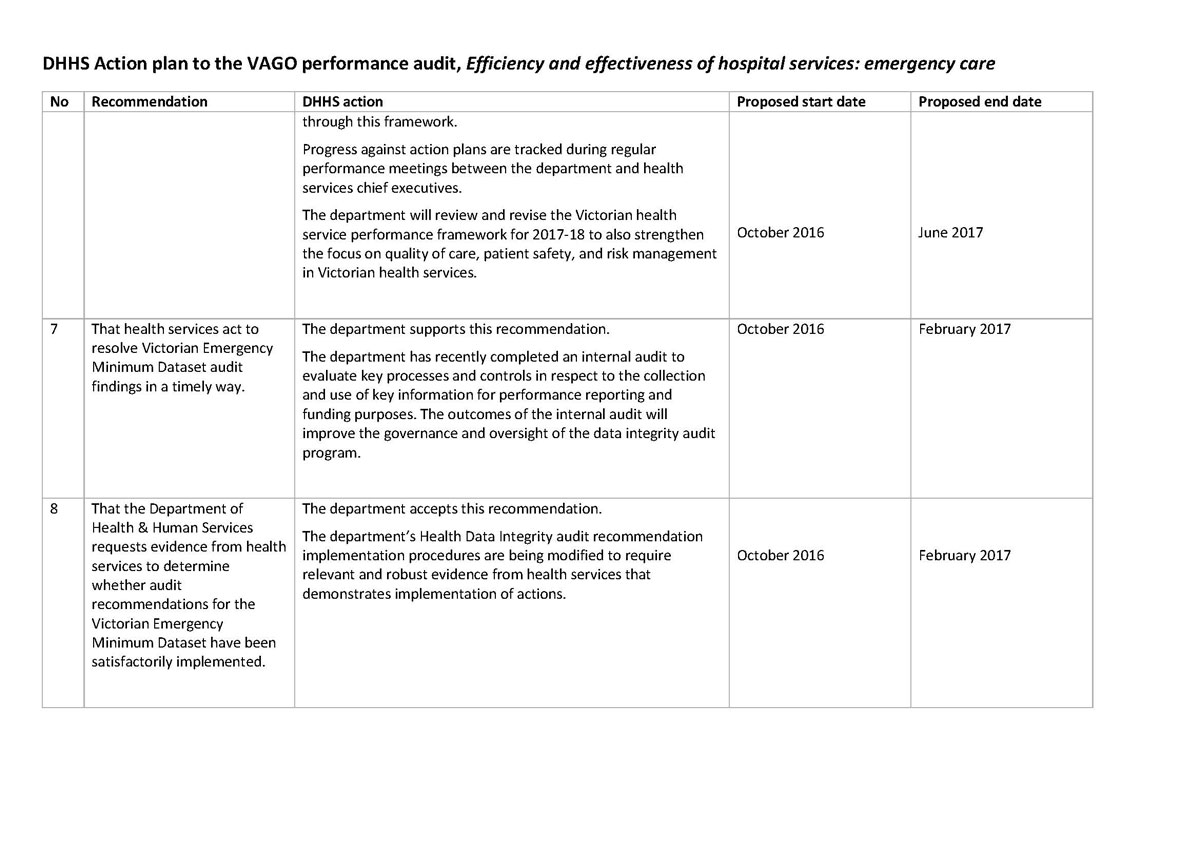

- require health services to provide evidence of actions taken to improve poor performance, measure progress and escalate declining performance (see Section 4.2)

- request evidence from health services to determine whether audit recommendations for the Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset have been satisfactorily implemented (see Section 4.4.1)

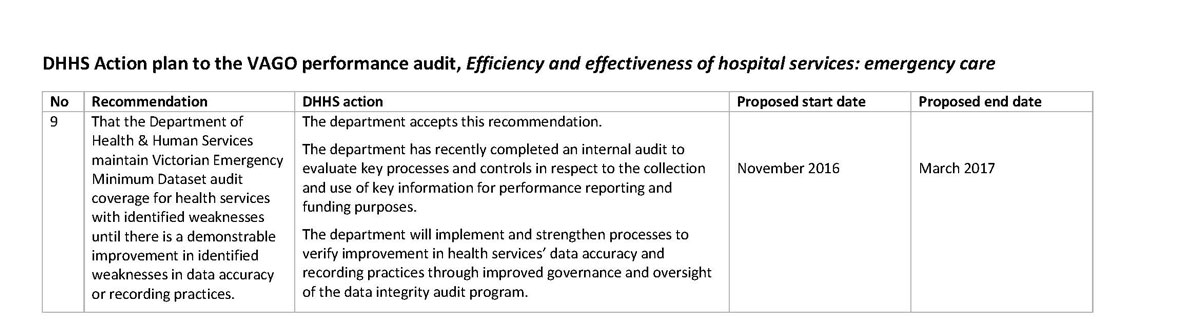

- maintain Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset audit coverage for health services with identified weaknesses until there is a measurable improvement in identified weaknesses in data accuracy or recording practices (see Section 4.4.1).

Responses to recommendations

We have professionally engaged with the Department of Health & Human Services and 30 health services during this audit. In keeping with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we provided a copy of this report, or relevant extracts, to those agencies and requested their submissions and comments. We also provided a copy of the report to the Department of Premier & Cabinet.

The following is a summary of those responses. The full responses are included in Appendix A.

The Department of Health & Human Services, Alfred Health, Barwon Health, Bass Coast Health, Eastern Health, GV Health, Latrobe Regional Hospital, the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital (RVEEH), the Royal Women's Hospital (RWH), Western Health and Wimmera Health Care Group (WHCG) responded, accepting all of the recommendations. The Department of Health & Human Services provided a detailed action plan on how it will implement recommendations. Health services also provided information on how they intend to address the recommendations that relate to them. RVEEH, RWH and WHCG supplied data on how they are already meeting targets for urgent and admitted patients.

1 Audit context

1.1 Introduction

Growing demand for hospital services has been a persistent problem in Victoria and nationally for more than a decade. The effects of higher demand are most visible in the pressure point of public hospitals: emergency departments (ED).

In 2014–15, more than 1.5 million people attended a public ED in Victoria, an increase of 8.2 per cent from 2010–11. In comparison, Victoria's population increased by 6.1 per cent between 2010 and 2014. In 2014–15, one-third of presentations—almost 500 000—were at a major metropolitan hospital.

The reasons for increasing demand are well documented. They include a growing and ageing population, higher rates of chronic and complex disease, and consumers becoming more aware of health problems. For some people, presenting to a public hospital ED may make financial sense—the hospital bears the cost of emergency care services such as scans, which would be an out-of-pocket expense if the patient were referred by a general practitioner. There is also a high demand to treat young people in EDs. Over the past five years, children aged four or under accounted for the greatest number of ED presentations, followed by 20–24 year olds.

Meeting demand for emergency care is a priority for the Department of Health & Human Services (the department). In 2015–16, the department spent around $565 million on emergency care, which is almost 5 per cent of the budget for acute services.

With demand for hospital services expected to increase, efficient and effective emergency care will be vital for Victorians to access high-quality treatment in public hospitals.

1.1.1 Four-hour emergency access target

The Council of Australian Governments established the National Emergency Access Target (NEAT) in 2011, and aimed to have 90 per cent of ED patients in Australia discharged or admitted to an in-patient ward within four hours by 2015. A national partnership agreement (NPA) provided financial incentives for states that achieved the emergency access targets in incremental stages. The National Health and Performance Authority used NEAT as a measure of ED overcrowding, when producing reports on Australian health care. The four-hour target was based on a target established in the United Kingdom (UK) to have 98 per cent of patients discharged or admitted within four hours. In 2010, this target was revised to 95 per cent, but UK hospitals have struggled to meet this target over the past two years.

When NEAT was established, Victoria agreed to staged targets to meet the four-hour goal—70 per cent of ED patients in 2011, 75 per cent in 2012, 81 per cent in 2013, and 90 per cent by 1 January 2015. However, most hospitals were not able to achieve their targets. The targets and NPA were withdrawn in 2014 following the change in federal government. In 2015, the department revised the four-hour target to 81 per cent for all Victorian EDs. New South Wales and Queensland also reverted to the 81 per cent target, but Western Australia adopted a target of 90 per cent. In 2014–15, Victoria was the fourth most efficient at meeting the four-hour target behind these three states.

1.1.2 Roles and responsibilities

Department of Health & Human Services

As the health system manager, the department is responsible for monitoring the performance of health services and providing system-wide guidance and funding.

One of the department's main objectives is to 'improve the quality, effectiveness and efficiency of healthcare services for Victorians'. To achieve this, the department aims to meet demand for hospital services, including ED presentations. Ensuring that public hospitals manage EDs efficiently and effectively is an important part of achieving this objective.

Health services and public hospitals

In Victoria, public EDs are typically located within public hospitals and are managed by health services, which are incorporated public statutory authorities established under the Health Services Act 1988.

The board of each health service is responsible for its governance and for managing and overseeing how EDs perform. Health services may manage several hospitals within a geographical location. In this report, each ED is identified by the hospital's name rather than the health service that manages it. 'Health service' is used to refer to the whole organisation.

1.2 Funding and monitoring performance

1.2.1 Funding

Funding for ED patients follows the clinical pathway for that patient. Emergency patients who are subsequently admitted to an in-patient ward are funded as part of the Activity Based Funding model and included in the Weighted Inlier Equivalent Separation cost weightings. ED patients who are discharged home are funded via the Non-Admitted Emergency Services Grant (NAESG). The NAESG funding is based on a combination of the cost of making resources available and the cost of the activity required to treat the patient.

1.2.2 Monitoring performance

Every year, the Minister for Health and individual health services agree on expected activity and performance goals for each health service. This is set out in their Statement of Priorities. The department monitors how well each health service meets the targets in its Statement of Priorities.

Its Victorian Health Services Performance Monitoring Framework outlines specific performance measures and the mechanisms used to monitor health services. The department updates this framework every year, and the most recent was published in July 2016.

The department measures the performance of an ED against access, timeliness, re‑presentations and patient experience targets. Figure 1A shows the key performance indicators and their related targets.

Figure 1A

Key performance indicators and targets for EDs

|

Key performance indicator |

Target |

|---|---|

|

Percentage of ambulance patients transferred within 40 minutes |

Equal to or greater than 90 per cent |

|

Percentage of patients treated within the clinically recommended time frame |

Varies depending on triage category |

|

Percentage of emergency patients with a length of stay in ED of four hours or less |

Equal to or greater than 81 per cent(a) |

|

Number of patients with a length of stay in ED longer than 24 hours |

Zero |

|

Percentage of emergency patients who did not wait for treatment |

Less than 5 per cent |

|

Percentage of emergency patients who re‑presented to the ED within 48 hours of previous presentation |

Less than 6 per cent |

|

Patient's experience of ED care |

85 per cent positive |

(a) A target of 75 per cent for this key performance indicator is stated in the Budget Papers. For this report, we have used the 81 per cent target agreed to by the Minister for Health and the health services in their Statement of Priorities.

Source: VAGO, based on information from the Department of Health & Human Services.

While these key performance indicators measure how efficient an ED is, there has been a lack of consensus within the health sector on which indicators are appropriate for measuring the effectiveness of emergency care. In 2016 the department introduced the last three effectiveness indicators shown in Figure 1A.

1.3 Defining emergency care

In this report, the term 'emergency care' means care that patients receive within the ED of a public hospital. An ED's core business is to provide urgent and emergency care for those who are acutely unwell, injured or have unexplained or undiagnosed problems. EDs are designed for short-term treatment and stabilising patients before they are discharged home or on to further care.

Efficiency

Efficient emergency care is aimed at meeting patients' needs in the most timely way possible, by using staff time and hospital resources to their best capacity and reducing unnecessary delays. We compared hospital performance data with the Victorian target —a length of stay in ED of less than four hours—as the main indicator of efficiency.

Effectiveness

Effective emergency care involves responding to patients' needs by providing access to the specialist services, treatment and advice they require. To measure effectiveness, we looked at re‑presentations to EDs and the proportion of patients who did not wait for treatment. We did not look at clinical standards such as the timeliness of interventions for specific conditions, because these standards do not allow us to assess the effectiveness of emergency care.

Discharge and admission

Patients presenting to an ED are assessed and then are usually either discharged home or admitted to the hospital. For the purpose of this report, admitted patients are those who are admitted to an in-patient ward or unit after ED assessment. Non‑admitted patients are those who did not require admission to the hospital and are instead discharged home after presenting to the ED.

Triage categories

When patients present to an ED, they are typically triaged based on the clinical urgency of their presentation. Victorian public EDs follow the Australasian Triage Scale, which consists of five categories. Category 1 indicates an immediate life threat where patients are to be seen immediately, while category 5 is used for less urgent problems where the patient is deemed able to wait up to two hours to be seen.

Short-stay units

Short-stay units (SSU) are a type of medical observation unit, separate from the ED. They are designed for ED patients who, with proper assessment, treatment and planning, are likely to be discharged within 24 hours. ED patients who are likely to require observation or treatment for more than four hours but less than 24 hours are ideally admitted to an SSU following ED assessment, and are classified as 'admitted' patients.

The department's guidelines on using SSUs emphasise that they are not to be used as an overflow for the ED, for patients waiting to be admitted to an in-patient ward or for patients awaiting transfer to another facility.

Fast-track services

Fast-track services are designed to improve flow within an ED by providing the less seriously ill patients with access to timely assessment, treatment and discharge. These services may differ between hospitals, as EDs adopt slightly different practices and resource models.

'Did not wait' and 'left at own risk'

'Did not wait' is a classification that describes patients who departed the ED:

- before being seen by or notifying clinical staff

- without receiving advice about alternatives to treatment in the ED.

This classification differs from 'left at own risk', which describes patients who leave the ED after being seen by staff despite being advised by clinical staff not to leave.

Hospital peer groups

We have grouped hospitals to allow us to more fairly compare performance based on ED resources, capacity and demand. The groups we use are based on the categories the department uses for ED performance reporting, and include major metropolitan, tertiary, other metropolitan, regional, subregional, specialist and local groups.

Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset

We used emergency care data from the Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset from 2011–12 to 2014–15. Data for 2015–16 was not available in time to include in this report.

Figure 1B depicts a patient's journey through an ED from presentation to discharge.

Figure 1B

Patient journey through an emergency department

Source: VAGO.

1.4 Previous audits

Two previous VAGO audit reports, Managing Acute Patient Flows (2008) and Hospital Performance: Length of Stay (2016), looked at how effectively and efficiently public hospitals manage beds and the flow of patients.

Both audits found that poor bed management practices and delays in discharging patients were reducing efficiency. The audits also found that the former Department of Health could better help public hospitals to benchmark their performance and share better practice improvements to services.

Our 2009 report Access to Public Hospitals: Measuring Performance looked at whether the indicators to measure access to emergency care used by the former Department of Health were relevant, appropriate and fairly represented hospital performance. We found that some data was inaccurate or had been manipulated, that data collection lacked rigour, and the indicators' appropriateness and relevance was limited.

1.5 Why this audit is important

When EDs run optimally, patients can access care that is appropriate, meets their needs and involves no unnecessary waiting. Shorter visits to the EDs are better for patients and are a more efficient use of public resources.

This audit highlights gaps and weaknesses in emergency care, which can help the department to set the right goals and incentives to achieve more consistent hospital performance. It can also lead to more targeted monitoring and oversight for areas that most need support. The audit also promotes good practice in emergency care so that hospitals can improve the patients' hospital experience and achieve greater efficiency and effectiveness.

1.6 What this audit examined and how

We looked at whether public hospitals are managing EDs efficiently and effectively. To determine this, we assessed whether:

- public hospital EDs are operating efficiently

- public hospital EDs manage patient flow effectively

- the department monitors and supports EDs to achieve efficient and effective patient care.

During this audit, we analysed data from 39 of the 40 Victorian public hospital EDs that report emergency patient data. We also looked in detail at four EDs within the major metropolitan hospital peer group—our 'audit sample'. We chose to sample major metropolitan EDs because of the relatively high demand they experience and because of the varied performance within the group.

During the audit, we:

- interviewed hospital staff at four hospitals

- toured EDs

- reviewed hospital evidence and data

- reviewed the department's quarterly data

- analysed data from the Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset.

We conducted the audit in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. In accordance with section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we express no adverse comment or opinion about anyone we name in this report.

The total cost of this audit was $462 000.

1.7 Report structure

This report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 looks at the efficiency of care in EDs

- Part 3 looks at the effectiveness of care in EDs

- Part 4 looks at the department's support for EDs.

2 Variation in the efficiency of emergency care

Access and timeliness are critical aspects of emergency care. Hospitals report regularly to the Department of Health & Human Services (the department) on patients' access to emergency services. Length of stay within an emergency department (ED) is an indicator of how well a hospital is managing patient demand. Hospitals are also benchmarked on the time it takes to treat patients based on urgency categories.

When a patient's entire episode of care takes place within an ED, ED staff have greater control over the patient's length of stay in the ED. Once a decision is made to admit a patient to an in-patient ward, ED staff rely on and coordinate with other departments in the hospital to try to admit patients efficiently.

This Part of the report looks at the efficiency of 39 Victorian public hospitals by comparing:

- length of stay in the ED

- use of short-stay units (SSU)—observation units

- length of stay in the ED for different cohorts of patients.

We also audited a sample of four hospitals selected from the major metropolitan peer group to understand how performance varied.

2.1 Conclusion

Public hospitals have reduced the average length of stay for ED patients between 2011 and 2015. However, despite this improvement, few hospitals meet the target of 81 per cent of presentations discharged or admitted within four hours, as set out in the Minister for Health's Statement of Priorities.

The average length of stay in an ED varies depending on the triage category of the patient. Patients with serious conditions were more likely to stay longer in the ED than those presenting with less serious conditions. One of the causes of a longer stay in the ED was the lack of available in-patient ward beds—essentially, some patients are staying longer in the ED than necessary because they cannot be discharged to another part of the hospital.

A common theme in hospitals that maintained or improved performance was strong leadership and whole-of-hospital accountability for managing demand in the ED.

Early decision-making by senior staff, good discharge planning and a commitment to removing silos between the ED and in-patient wards help to improve the flow of patients through the hospital. These approaches to managing EDs are not new, but they require considerable staff engagement and commitment to embed them in the hospital's daily routines.

SSUs are designed to keep patients who require further observation and assessment comfortable and separate from the ED for up to 24 hours. However, hospitals are using SSUs in ways that do not align with the department's guidelines. All hospitals have had patients breach the recommended 24-hour length of stay in SSU.

There is a risk that in busy EDs where patients are facing long waits, staff could transfer patients to SSUs in order to artificially improve ED waiting times and performance against the four-hour target. Longer hospital stays in EDs or SSUs are both inefficient and, with some exceptions, not in a patient's best interests. The department needs to determine if misuse is occurring. It has begun visiting hospitals to understand SSU practices.

2.2 Improved efficiency throughout the system

Hospital staff record the timing of key elements of a patient's journey through an ED for the Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset. The data is used to monitor the efficiency of hospitals in treating emergency patients and the accessibility of care. Comparing the average length of stay of patients in EDs against the four-hour target shows that Victorian public hospitals have gradually improved ED length of stay between 2011 and 2015. Despite this improvement, hospitals are consistently failing to meet the four-hour target.

For patients who need to be admitted to an in-patient ward, the wait time is particularly long, averaging 5.7 hours across all Victorian public hospitals, but reaching over seven hours in eight EDs. Only one hospital reached the four-hour target.

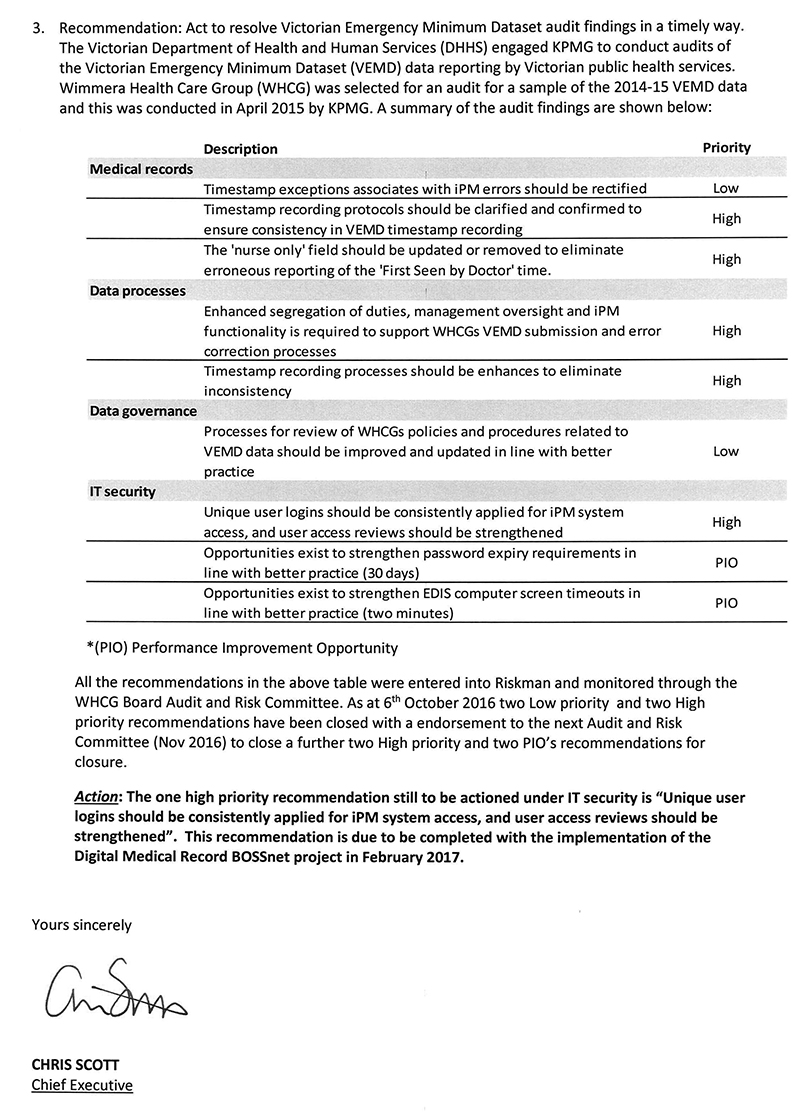

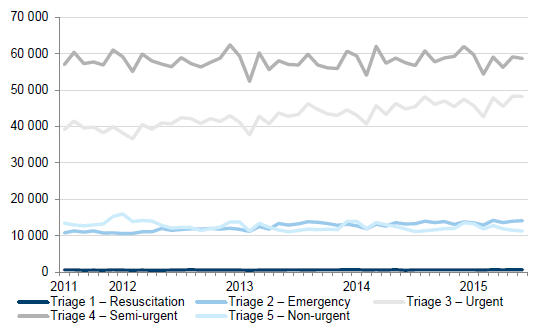

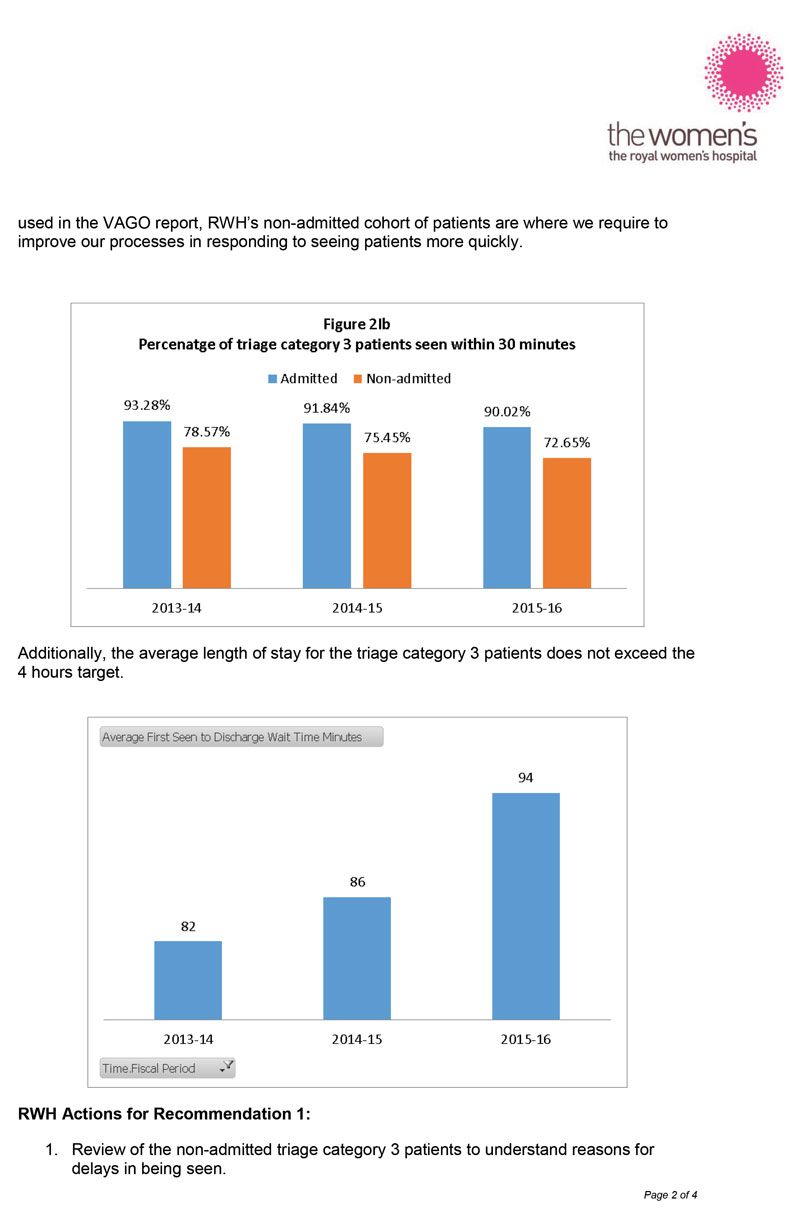

Figure 2A shows that demand for emergency care in Victorian public hospitals increased in the four years to June 2015. Major metropolitan hospitals experienced the most significant growth compared with other hospital peer groups.

Figure 2A

Total number of presentations to EDs, July 2011 to June 2015

Source: VAGO, based on data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

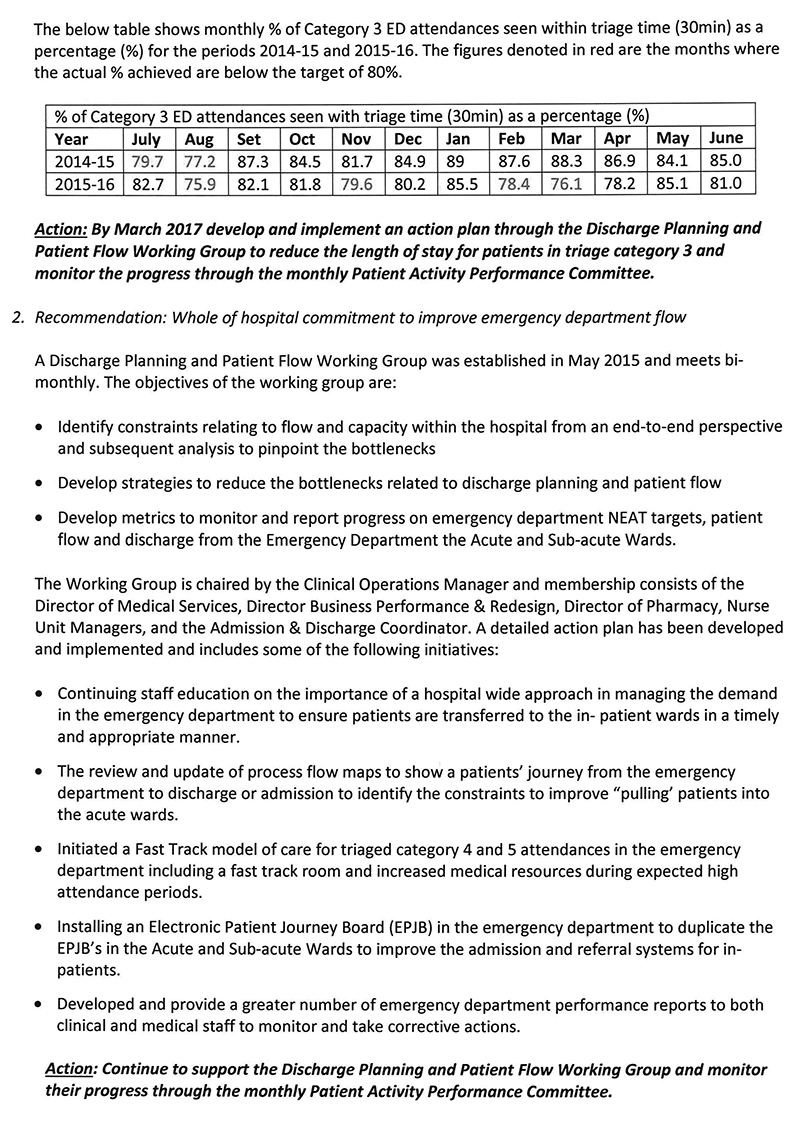

In addition to a rise in the overall volume of patients, there was also a rise in the number of patients presenting who are classified as 'urgent'—triage category 3, indicating patients who are likely to have more complex or pressing needs—as shown in Figure 2B. Despite this increase in demand and complexity, hospitals were able to reduce the average length of stay for patients in EDs during this four-year period.

Figure 2B

Total number of presentations to EDs by triage category, July 2011 to June 2015

Source: VAGO, based on data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

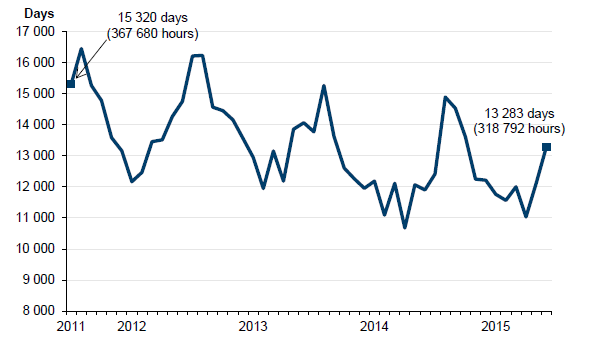

The average time patients were in ED beyond the four-hour target reduced by 13 per cent between 2011 and 2015, or 48 888 hours. This is evidence of hospitals' continued commitment to caring for patients more efficiently. Figure 2C shows this reduction in days.

Figure 2C

Total number of days patients spent in EDs beyond the target of four hours, July 2011 to June 2015

Source: VAGO, based on data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

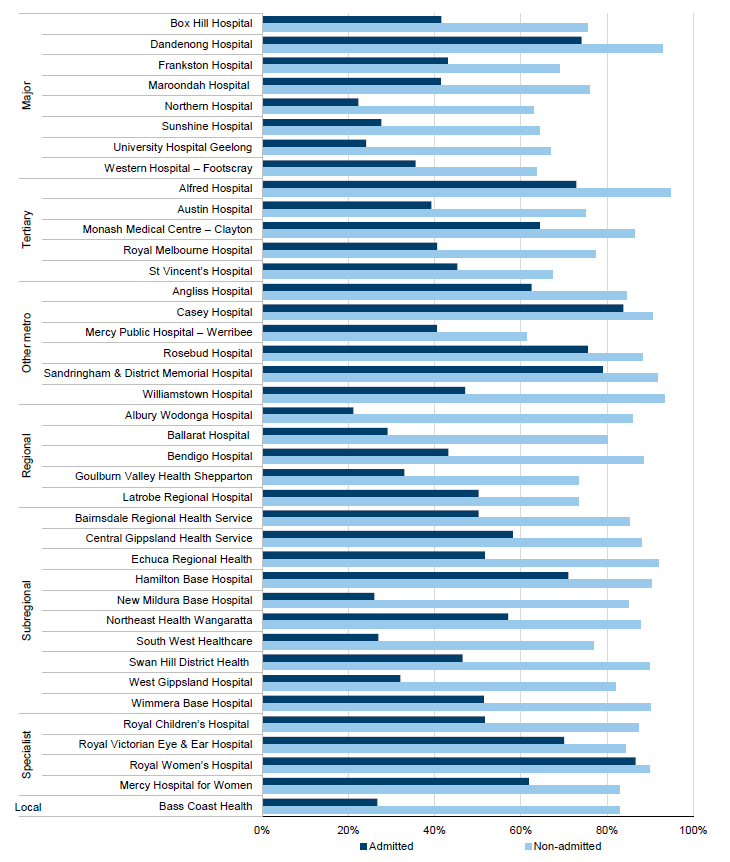

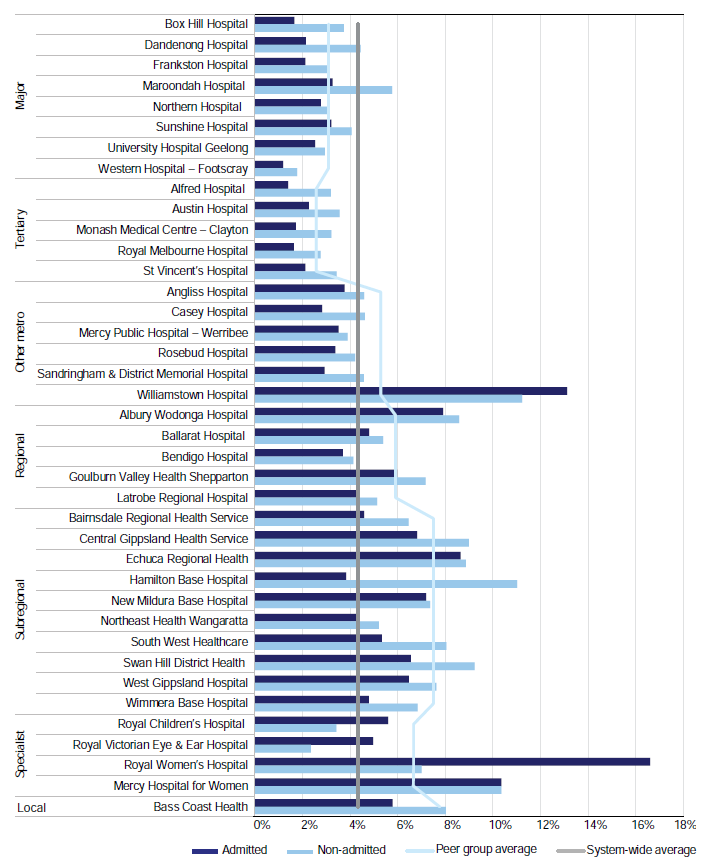

The length of stay for non-admitted ED patients varies dramatically from that of patients admitted to an in-patient ward in the majority of hospitals. Figure 2D shows the variation in the proportion of admitted and non-admitted patients who were discharged from EDs within the four-hour target. Gaining access to an in-patient ward is a longer process and is influenced by staffing levels, the availability of beds throughout the hospital, the processes for discharge in acute and sub-acute wards, and a range of other factors. ED staff also point out that when a patient needs to be transferred to another hospital, the time it takes for the transfer to be completed and the resulting 'length of stay' is often beyond the control of the transferring hospital.

Figure 2D

Percentage of presentations discharged from EDs within four hours, 2014–15

Source: VAGO, based on data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

This variation in length of stay indicates that efficiency gains are yet to be realised for the admitted cohort of ED presentations. The reduced length of stay of patients who are not admitted to an in-patient ward can, in part, be attributed to their admission to an SSU—see Section 2.5.

2.3 Variation within hospital peer groups

Patients with similar presenting symptoms should expect similar access to emergency care, irrespective of which hospital they attend. Variation in the performance of hospitals can highlight different organisational strategies, challenges in responding to demand, staffing issues, problems with access to beds and specialist services, and a range of other underlying problems.

While the average ED length of stay has decreased across public hospitals since 2011, the performance of hospitals within peer groups has varied widely. Analysing system‑wide data using urgency-related groupings—for example, injury, respiratory and mental health-related presentations—can test whether access to services is consistent across public hospitals for patients with similar symptoms.

2.3.1 Reasons for variation

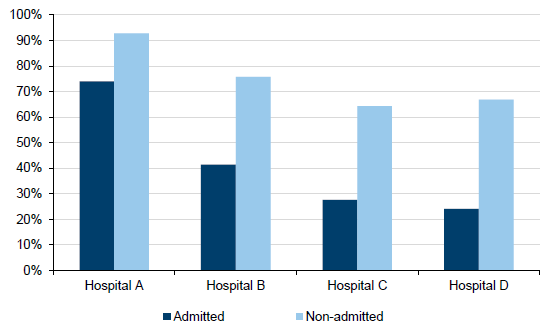

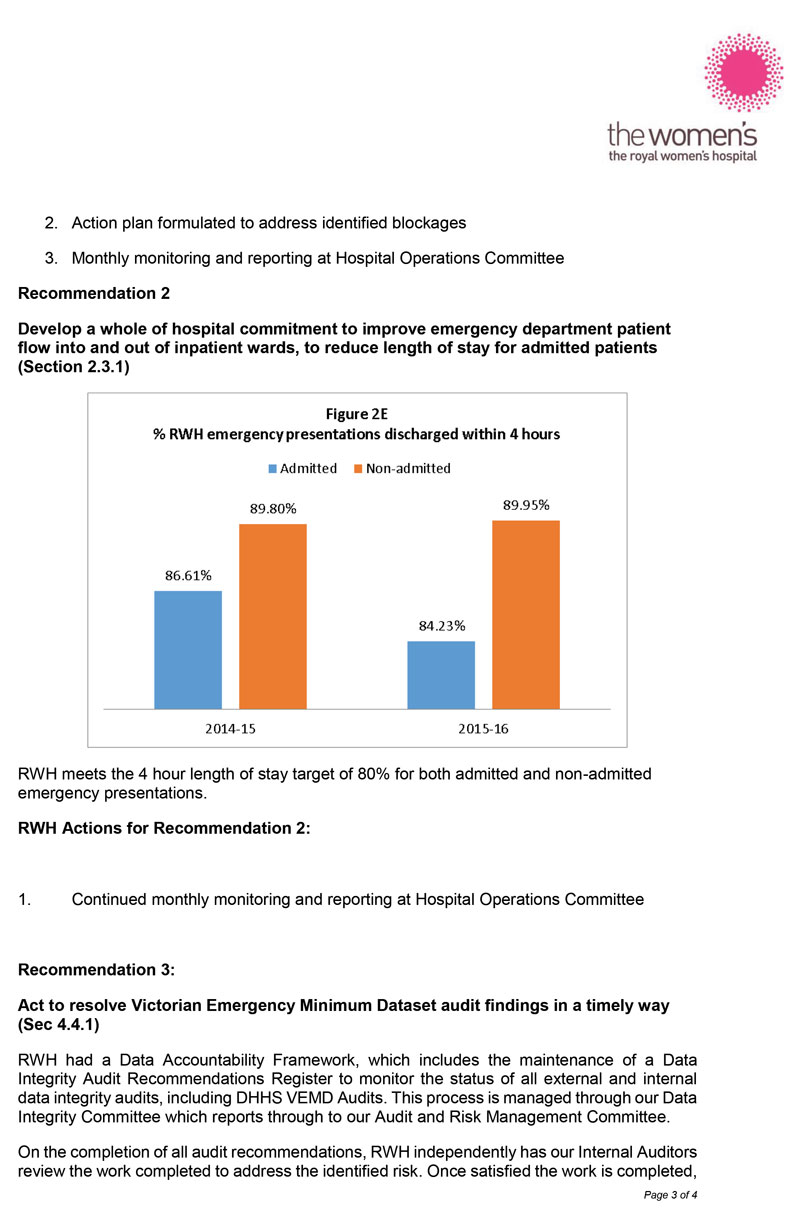

We assessed an audit sample of four hospitals from the major metropolitan peer group to understand why performance varies. Figure 2E shows the variation in the sample group's performance against the four-hour target during 2014–15. Results from the audit sample indicate that efficient EDs require strong top-down leadership and cooperation from in-patient wards and units.

Figure 2E

Percentage of presentations discharged within four hours from a sample of major metropolitan EDs, 2014–15

Source: VAGO, based on data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

Results from the two better-performing hospitals and one that had recently improved its performance indicate that a whole-of-hospital approach to ED demand, supported by senior staff, is critical. When staff feel responsible for helping ED patients to move through the hospital, a 'pull' model is created, where staff in acute and sub-acute wards are able to draw patients from the ED, rather than ED staff having to 'push' patients through.

In contrast, interviews with hospital staff highlighted that a siloed culture and resistance from senior clinicians can hamper attempts by senior management to establish whole‑of-hospital responsibility for ED demand and patient flow through the hospital.

One of the better-performing hospitals in our sample had access to more in-patient beds and SSUs than the others. This, in addition to its whole-of-hospital approach to ED care, is likely to account for its superior performance. Another hospital recently changed its model of care, but its staff felt that a lack of beds and the hospital's inability to keep pace with demand would limit their capacity to achieve further efficiency gains. Some ED directors told us that the efficiency gains possible for non-admitted patients had largely been made already and that the focus needed to shift to improving the timeliness of transfers to in-patient wards.

2.3.2 Variation in urgency-related groups

ED patients are classified in urgency-related groups, based on the type of condition and its complexity. For this audit, we analysed data from all EDs on respiratory-related presentations in 2014–15, to check whether there was variation in patients' length of stay within this urgency-related group. Patients with respiratory problems are likely to have their symptoms worsen in winter, so results for this group should also show how hospitals respond to seasonal changes in demand.

Length-of-stay data for respiratory patients across all peer groups was consistent with the results for all emergency patients—the length of stay in EDs for admitted presentations was much greater than for non-admitted presentations. This is most evident in regional hospitals, where the gap between admitted and non-admitted length of stay is widest. Once again, ED staff spoke of the importance of whole-of-hospital responsibility for managing ED demand.

While there was a dip in performance in colder months, it was not pronounced. This shows that hospitals are probably planning for and are able to cope with additional seasonal demand.

In the sample group, there was also a gap between the length of stay in EDs for admitted and non-admitted patients, but it was more pronounced in Hospitals C and D. The hospitals in our sample that performed well generally also performed well for this urgency-related group.

2.4 Short-stay units

If patients presenting to an ED require longer observation, ED staff can admit them to an SSU. The primary purpose of SSUs is to provide intensive short-term assessment, observation or treatment of patients to optimise early treatment and discharge, and to reduce the overall length of time patients stay in hospital.

Some hospitals have designated SSUs for paediatric patients (children) and for mental health patients. Ideally, paediatric, adult and mental health patients should be kept apart—but when space is limited this can be a challenge.

In 2009, the department released Observation Medicine Guidelines. In June 2015, the department updated the Victorian Hospital Admission Policy to include clearer patient inclusion and exclusion criteria, staffing models and potential indicators for monitoring use of SSUs. A criterion for admission to an SSU is that a patient transferring from the ED must have a clearly documented clinical management plan or pathway while in the SSU.

The department's guidelines also state that SSUs:

- are designed for stays no longer than 24 hours

- are physically separate from the ED acute assessment area

- have a static number of beds

- must not operate as a temporary ED overflow area

- must not be used to keep patients solely awaiting discharge, admission to an in‑patient ward, transport or ED treatment.

Staff in four hospitals argued that SSUs are an appropriate place for patients waiting for discharge and transfer. Across public hospitals, there is now a variety of adult, paediatric and mental health SSUs. During the audit, we observed adult and paediatric patients in the same SSU area, but it was not clear whether all EDs had separate units for patients presenting with mental health symptoms.

Hospital practice may also vary in the number and type of staff who are rostered to supervise SSU patients overnight. Typically hospitals reduce staffing at night but SSU patients may need more intense observation. The department needs to understand how these practices impact on patient care and update its guidance accordingly.

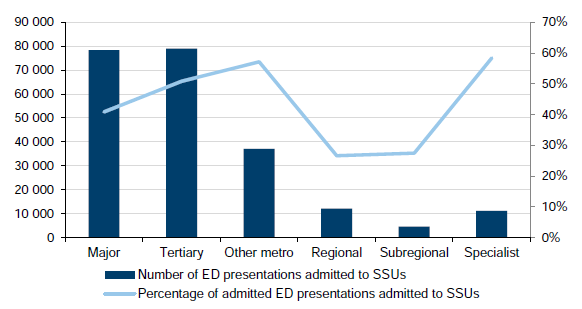

Figure 2F shows that SSUs are used predominantly in tertiary and metropolitan hospitals.

Figure 2F

Number of presentations and percentage of admitted ED presentations admitted to SSUs by peer group, 2014–15

Note: The percentage used is an average for each peer group. We excluded hospitals that did not report admissions to SSUs in 2014–15.

Source: VAGO, based on data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

2.4.1 Funding

Public hospitals receive funding for ED presentations and also receive separate funding for ED patients if they are admitted to an in-patient ward, to follow their pathway through the hospital and to align with the costs of care. Patients who are admitted to an SSU are classified and funded as an admitted patient, so the hospital receives funding for both their ED and SSU visits. Some ED staff expressed concern that funding could be maximised by increasing the number of patients admitted to an SSU. Other ED staff were not aware of how funding related to different ED activities.

The department states that a set amount of funding for admitted patients is calculated using the Weighted Inlier Equivalent Separation (WIES) unit, and using SSUs disproportionately will dilute the average WIES price a hospital receives over time. The department does not currently benchmark SSU performance. The introduction of benchmarks for using SSUs should reduce the potential for hospitals to over-admit patients to SSUs in the belief they are improving ED performance.

Hospital funding is complex, and emergency access performance is interdependent with performance in the rest of the hospital. Therefore, the design of emergency care systems and funding models need to encourage timely and appropriate practices for assessment and treatment. While we did not consider ED funding in this audit, we note that the department has said that it plans to review SSU pricing in 2016, to assess how to better align funding policy with program policy and system design.

2.4.2 Admission and performance

Admissions to SSUs are correlated with better performance against the four-hour target for admitted patients. In 2014–15, up to 36 per cent of all ED presentations and up to 80 per cent of admitted ED presentations were admitted to an SSU. This is an efficient model of care for patients requiring further observation and assessment.

After being admitted to an SSU, patients are no longer recorded as waiting in the ED. So, in hospitals where ED patients face waits of more than four hours, an unnecessary admission to an SSU helps the hospital to meet the four-hour target. It is not clear whether SSUs have been used in this way but, without proper departmental oversight, the potential for such use exists.

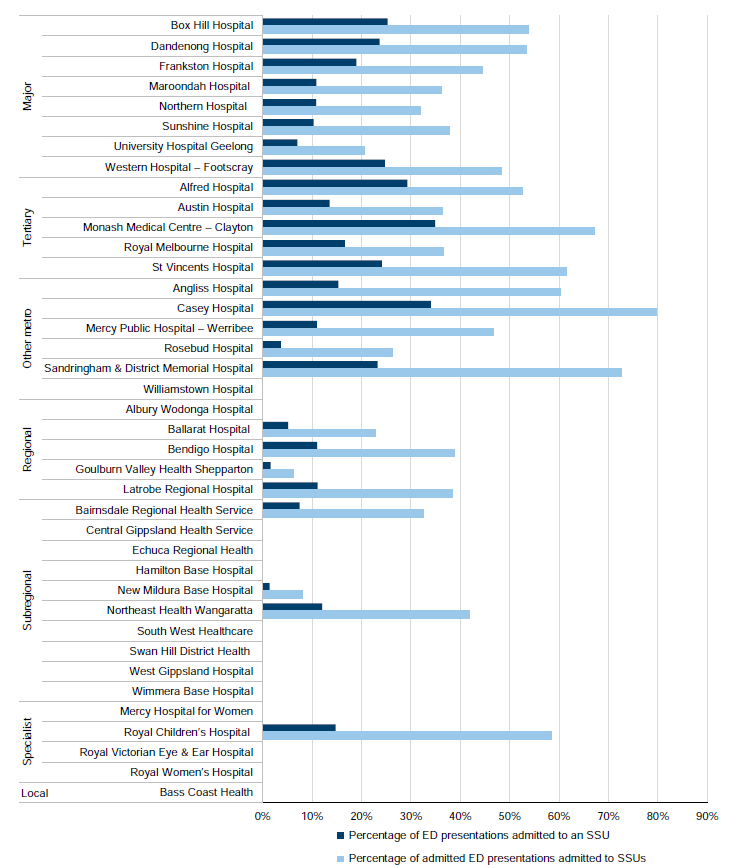

Figure 2G shows the percentage of all ED presentations admitted to SSUs and the percentage of those in SSUs who are subsequently admitted to an in-patient ward.

Figure 2G

Percentage of ED presentations admitted to SSUs, 2014–15

Note: Where no data is listed for a hospital, they have not reported any admissions to an SSU in 2014–15.

Source: VAGO, based on data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

The number of SSU beds per hospital does not appear to be proportional to current ED demand. According to departmental data from 2015–16, on average 7 per cent of patients in SSUs were then admitted as in-patients across the system, but three outliers had rates of 12, 14 and 20 per cent. Hospitals may share information on rates of admission to SSUs and subsequent admission to an in-patient ward, but the department does not request this information, which means that the use and level of internal reporting of this information varies. One hospital was unable to match the department's data on subsequent admission to an in-patient ward following an SSU stay to their internally recorded data.

In the audit sample of four major metropolitan hospitals, higher rates of admission to an SSU were associated with a shorter length of stay. The number of SSU beds per ED varied, as did rates of subsequent admission to in-patient wards and approaches to SSU use. Hospital C had a lower rate of SSU admission compared with its peer group, and a longer length of stay for all ED presentations. Hospital B had only a small number of adult beds in its SSU, but had comparatively fewer ED presentations and performed well against the four‑hour target. Staff at Hospital B told us that this performance resulted from their whole-of-hospital approach. However, they acknowledged that increasing the number of SSU beds would improve their efficiency.

Figure 2H

Percentage of ED presentations admitted to SSUs in the audit sample, 2014–15

Source: VAGO, based on data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

2.4.3 Varied use

The department's guidelines state that SSUs are not intended for patients waiting for admission or transfer to another facility. However, some ED directors argue that SSUs are an appropriate place for these waiting patients when there are no adequate or separate facilities.

The department monitors some SSU activity but does not understand the extent to which the use of SSUs varies from the guidelines and the pressures that cause EDs to use SSUs in these ways. The department needs to better understand the extent and causes of variation in SSU use to determine whether it needs to update its criteria.

The department advises that it is examining SSU use and plans to improve SSU performance by developing quality and timeliness measures.

2.5 Length of stay for patients in triage category 3

The Australasian Triage Scale is used to benchmark hospitals on how quickly they respond to patients. For example, patients triaged as 'resuscitation' (triage category 1) must be seen immediately, but for less acute cases (triage categories 4 and 5), the benchmark is for patients to be seen within one to two hours respectively.

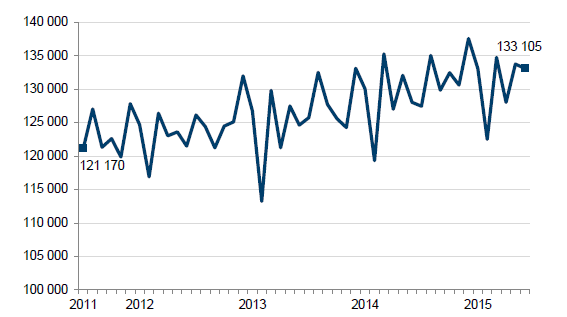

EDs are seeing the most urgent patients in a timely way, and have made considerable progress in reducing the waiting time for patients in triage categories 4 and 5. In March 2016, 73 per cent of hospitals met the target of seeing 80 per cent of triage category 3 ('urgent') patients within the clinically recommended time frame of 30 minutes. However, these urgent patients have a longer overall stay in ED, especially in metropolitan hospitals—on average between four and six hours—most likely due to delays in availability of in-patient staff and beds.

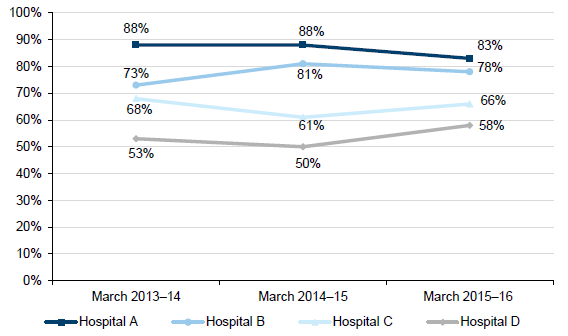

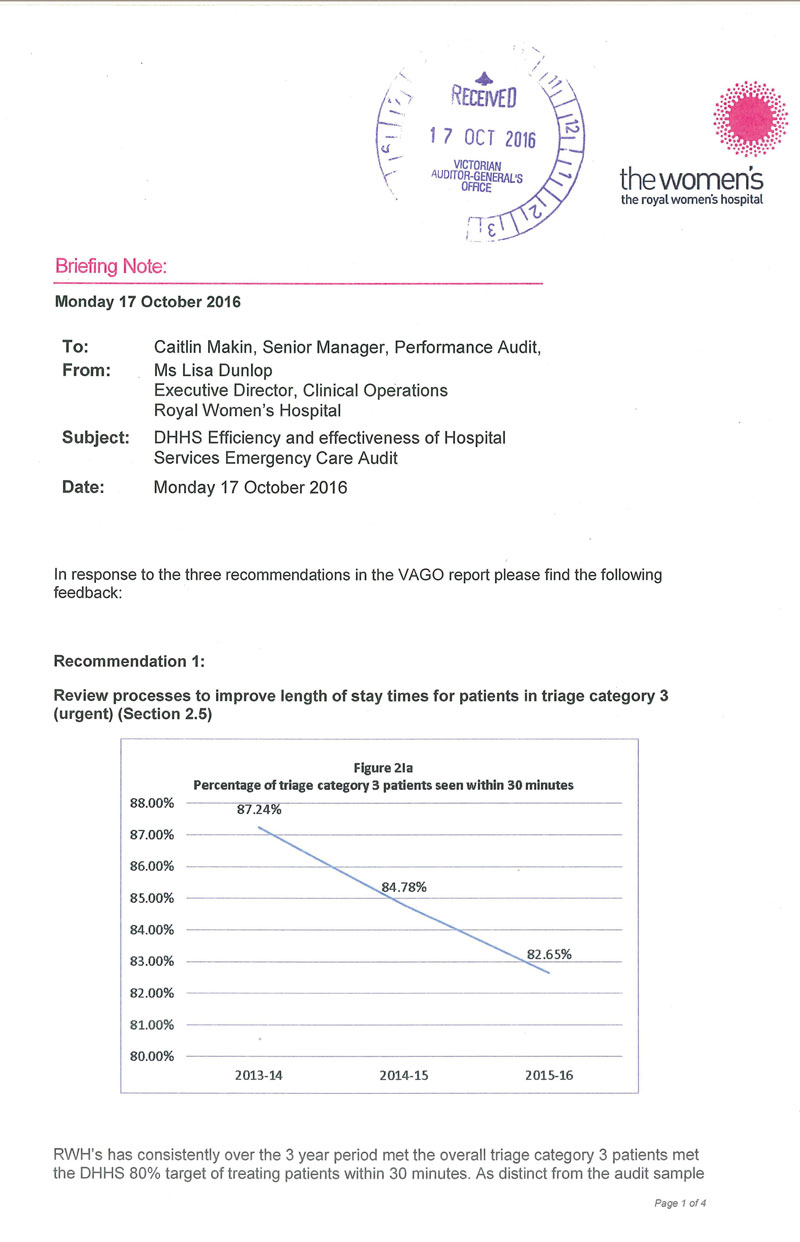

Improvements in wait times for less acute patients (triage categories 4 and 5) have not been consistently matched at the same rate for patients in triage category 3. Figure 2I shows that, in the audit sample of four hospitals, only one hospital treated triage category 3 patients within the clinically recommended time frame more than 80 per cent of the time in 2015–16. The other three hospitals met this time frame only 58–78 per cent of the time.

Figure 2I

Percentage of triage category 3 patients seen within 30 minutes in the audit sample, 2013–14 to 2015–16

Source: VAGO, based on data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

One ED director noted that triage category 3 patients often miss out on resources when the department is busy and, therefore, triage category 3 treatment times are a good measure of how a hospital copes with high demand in the ED. Another argued that measuring the time that elapses before a request is made for a bed in the in‑patient ward, and the total length of stay for non-admitted category 3 patients, would be useful.

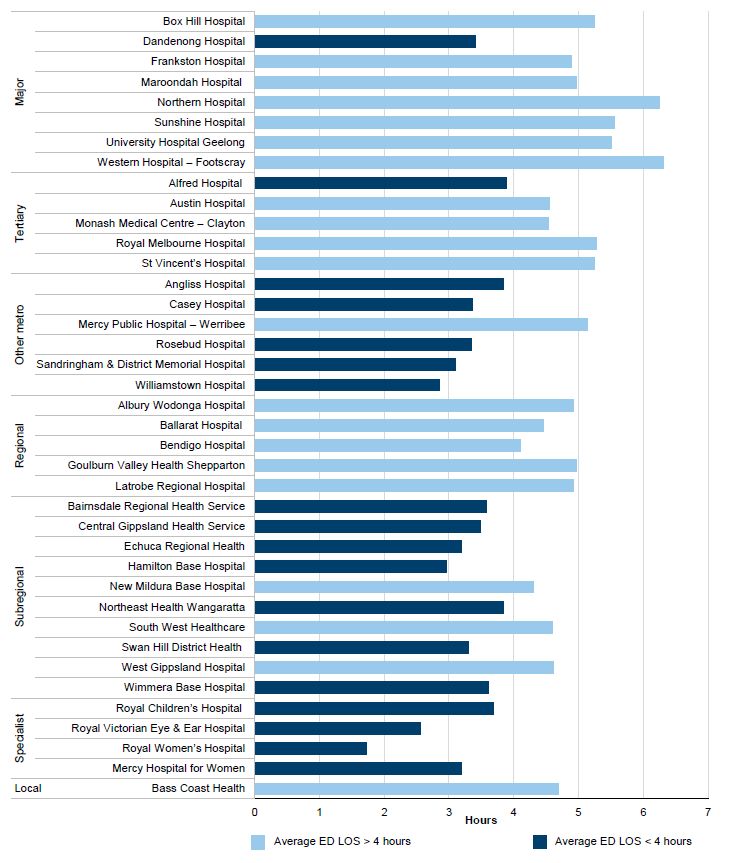

Figure 2J shows that 21 of the 39 hospitals in the broader sample did not meet the four-hour time frame. These hospitals need to review their processes to reduce the time that urgent patients wait in the ED. This may involve making concerted efforts to engage staff throughout the hospital to help respond to the demand. A number of ED staff told us that when sub-acute facilities are discharging patients efficiently, this has a positive effect on the ED's ability to move patients to in-patient wards.

Figure 2J

Average length of stay in EDs for triage category 3 patients, 2014–15

Note: LOS = length of stay.

Source: VAGO, based on data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

3 Effective emergency care

Emergency departments (ED) are often designed to reflect their specific case mix and clinical specialities, the available resources and infrastructure, and patient demand. The Department of Health & Human Services (the department) provides guidance on hospital admissions, triage approaches and observational units, and in 2016 introduced three measures of effectiveness. EDs also look to high-performing services to improve patients' experience at the hospital.

Hospitals must report to the department the percentage of patients who re-present to the ED after being discharged. We found that re-presentations within 48 hours to the same ED were within an acceptable rate of 6 per cent for most hospitals.

While hospitals continue to debate the most appropriate measures of ED effectiveness, there are two commonly used sets of data that provide a reasonable insight into effective care. To see how an ED responds to patients' needs, we can use data that measures:

- the proportion of patients who re-presented to the ED after an initial visit

- the proportion of patients who chose to leave the ED without being seen.

In this Part, we assess these two measures and look at different strategies to improve the movement of patients through hospitals.

3.1 Conclusion

Without comprehensive measures for effective emergency care it is difficult to assess whether ED care was appropriate for a patient's needs.

Measuring the rate of patient re-presentation is currently of limited use for assessing effectiveness because hospitals record the data inconsistently. They do not identify 'planned' re-presentations—patients who were told to return to the ED to access care that was not available when they first presented. Therefore, we cannot use this data on re-presentation rates to understand potential problems in caring for patients, such as the patient being unable to access services.

A common theme in hospitals that maintained or improved performance was leaders who were able to engage the whole hospital in managing demand in the ED. Senior staff making timely decisions, planning discharges well and committing to removing barriers between the ED and in-patient wards help to improve how patients move through the hospital. These approaches are not new—but they require considerable staff engagement and commitment to embed them in daily routines.

3.2 Initiatives to improve patient flow

Having a good flow of patients through an ED requires a system that:

- is coordinated to avoid unnecessary waiting and bottlenecks

- connects patients to relevant specialists and diagnostics

- adapts to high demand throughout the hospital.

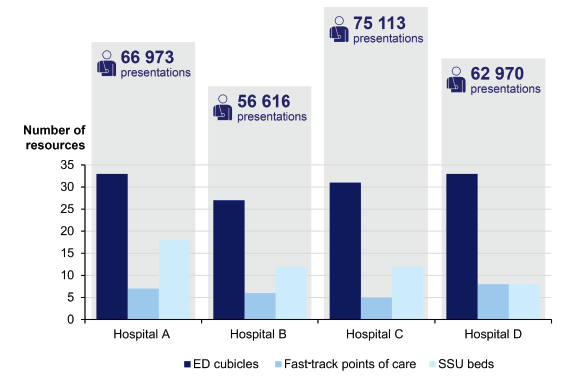

Figure 3A shows the different bed configurations in the four hospitals in our audit sample, and the number of presentations they received in 2014–15. EDs use a combination of resources:

- ED cubicles

- short-stay unit (SSU) beds, used to observe and assess patients for up to 24 hours

- fast-track points of care, which are beds or chairs in areas designated for less urgent patients.

Figure 3A

Resources and presentations in the audit sample, 2014–15

Source: VAGO, based on hospital data.

Hospital D has half the number of SSUs as Hospital A. Hospital C has the fewest fast‑track points of care but the most presentations.

The hospitals in the audit sample identified a range of initiatives that had helped to improve their efficiency and effectiveness, such as early decision-making by senior staff and 'fast-tracking' less acute patients. When the whole hospital takes responsibility for coping with high demand for ED services, patients who need to be admitted to an in‑patient ward are likely to get there more quickly.

The smooth flow of patients through the hospital also improves when senior staff have the authority to admit patients to an in-patient ward without having to wait for the receiving unit to review the patient, and have an understanding of the complete patient journey.

3.2.1 Admission to in-patient wards

Giving ED clinicians 'authority to admit' worked well in three of the four hospitals in the audit sample, backed by strong leadership and cooperation throughout the hospital. The fourth hospital did not use this approach, and its staff reported a lack of cooperation between their ED and in-patient units.

3.2.2 Decision-making at senior levels

Three out of the four hospitals in the audit sample have successfully used senior staff early in the patient's journey—for example, at triage, when a patient first arrives—to help with decision-making. However, not all hospitals were able to properly staff the senior positions at peak times or later in the day or night shift. A subregional hospital not included in the audit sample told us that not having a triage nurse on night shift reduces the ability of other nursing staff to cover all duties effectively.

Hospital D told us that it employed a higher proportion of junior staff than other hospitals. Junior staff often work night shifts and may be reluctant to make decisions about discharging, admitting or transferring a patient. This can lead to a backlog of patients to be discharged or admitted to an in-patient ward in the morning. ED directors told us that, ideally, senior physicians should review and make decisions throughout the patient's journey through the hospital.

3.2.3 Understanding the patient's journey

Our interviews with hospital staff identified that some hospitals have an inadequate understanding of the causes of bottlenecks in a patient's journey.

Hospital D had recently improved the range and type of data it reported and held weekly meetings to identify access problems, but staff throughout the hospital did not fully understand the delays, did not feel adequately engaged or did not feel a sense of ownership of the patient journey.

During this audit, we observed an 'escalation' phase at Hospital D, due to high demand in the ED. An ED can enter an escalation when demand is high and there is a backlog of patients needing to be admitted to an in-patient ward. During the escalation, senior staff and in-patient ward staff are notified so that they can intervene, to help to discharge or transfer patients and free up beds. At Hospital D, the escalation was ignored by the rest of the hospital, and we saw no evidence of staff working together to solve problems with admissions and discharges or making the admission or discharge process smoother.

Mapping ED processes for allocating beds and admitting patients to wards, and assigning targets, can help hospitals to identify bottlenecks. Some hospitals have their own targets to identify delays between a bed request being made and the patient being transferred to the bed, but unless the hospitals try to understand the causes of delays, this data loses impact. Hospital staff identified wait times for cleaning as another possible cause of delay. All of the hospitals tried to improve the patient discharge process, but they had mixed results.

Every hospital in the audit sample has systems and staff to improve access to available in-patient beds. Of the four hospitals in our audit sample:

- three give emergency clinicians the authority to admit patients, but the fourth does not

- three had discharge lounges to help with the flow of patients out of in-patient wards, and the fourth hospital told us it had piloted this approach but it had been misused and had failed.

3.2.4 Coordinating discharges

Clinicians and ED directors told us about the need to focus on the patient's journey beyond the ED into in-patient wards and sub-acute facilities such as rehabilitation units. Although it takes considerable effort to get hospital staff to coordinate and improve the way they discharge patients, staff felt that freeing up beds in sub-acute facilities helped to make more beds available throughout the hospital.

3.3 Re-presentations

Benchmarks for measuring the effectiveness of emergency care are not well defined. In the past, the department reported on the rate of re-presentations to in-patient wards but not to EDs. The department needs to consult with EDs to develop more comprehensive indicators. ED clinicians told us that, despite considerable debate, there is little consensus about what measures of effectiveness are appropriate. Hospital staff need to follow rules for data collection consistently to ensure that new benchmarks help to accurately record the number of re‑presentations.

For 2016–17, the department has introduced three quality performance measures that health services are required to report against, which are outlined in Figure 3B.

Figure 3B Quality performance measures, introduced in 2016–17

|

Performance measure |

Target |

|---|---|

|

Percentage of emergency patients who did not wait for treatment |

Less than 5 per cent |

|

Percentage of emergency patients who re-presented to the ED within 48 hours of previous presentation |

Less than 6 per cent |

|

Patient's experience of ED care |

85 per cent positive |

Source: VAGO, based on information from the Department of Health & Human Services.

The new measures are a good starting point, and hospitals in the audit sample were completing internal reporting against these measures prior to July 2016. However, re‑presentation rates may point to a lack of access to specialist services, rather than a problem arising from the initial ED visit, such as misdiagnosis. The department needs to work with health services to develop measures that will provide a meaningful indicator of effectiveness.

Data from the Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset shows that the percentage of ED patients re-presenting to an ED within 48 hours fell in the four years to June 2015. However, some ED staff told us that hospitals were recording data inconsistently and others were unsure about whether planned re-presentations were accurately recorded. These inaccuracies will not show up during the department's quality assurance checks of the dataset.

Figure 3C shows that, in 2014–15, re-presentations were around 4 per cent—close to the national benchmark of 5 per cent and in line with the new Victorian target of less than 6 per cent.

Figure 3C

Percentage of re-presentations to the same ED within 48 hours, 2014–15

Source: VAGO, based on data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

Regional hospitals are more likely to have a higher rate of re-presentation if patients are returning to the ED to access services such as imaging and allied health, which are only available during business hours.

In the audit sample, Hospital B asked for funding to improve its rate of re‑presentations. The hospital believes that a lack of timely access to specialists affects its ability to provide 24-hour services. It is common for hospitals in areas where access to specialists is limited to discharge a patient and ask that they return to be readmitted when specialists are available.

It is unclear how Hospital B reports re-presentations. For example, hospital staff may advise a patient or carer to return to the ED if symptoms worsen, and this is common in paediatric presentations. Hospital B staff told us that their higher rate of re‑presentations could be due to patients, who would otherwise face long waits for imaging or other specialist services, being discharged and asked to present at a later agreed time.

These 'planned re-presentations' can be recorded on the Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset, but it is not clear whether clerical staff and others recording patients' data consistently follow the dataset's guidelines for recording planned re‑presentations. The department and hospitals need to clearly communicate rules for recording data and improve processes to ensure that they are followed.

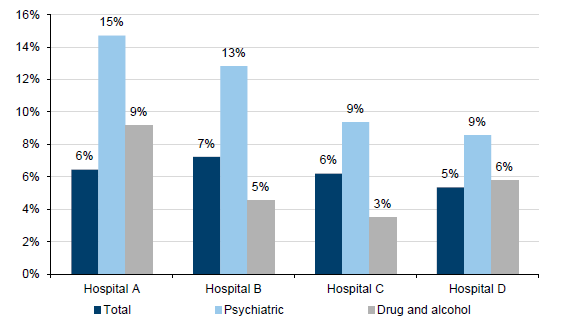

Psychiatric and drug-related re-presentations to EDs within 48 hours for the sample group show that the rate is about 6 per cent. These cohorts often have higher rates of re-presentation and are also likely to stay longer in EDs. Patients who present with drug or alcohol intoxication need to wait while they detox or may be sedated in the ED before being admitted. Staff also reported that access to in-patient beds is limited.

Hospitals report on re-presentations within 48 hours, however, when the data period is extended to 72 hours the rate for psychiatric re-presentation jumps. In Hospital A psychiatric re-presentations rise from 7 per cent to 15 per cent, and in Hospital B they rise from 4 per cent to 13 per cent. The rate also rises between 4 and 5 per cent in Hospitals C and D when the data period is 72 rather than 48 hours.

ED staff confirm that most stays in an ED that exceed 24 hours are for patients presenting with mental health problems. In 2016–17, hospitals will lose performance points for stays in an ED of longer than 24 hours. A hospital's performance score determines how much the department monitors the hospital. Performance monitoring is discussed in more detail in Part 4 of this report.

Figure 3D compares re-presentation data on psychiatric and drug patients within 72 hours in the audit sample for 2014–15.

Figure 3D

Percentage of re-presentations to EDs in the audit sample within 72 hours, 2014–15

Source: VAGO, based on data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

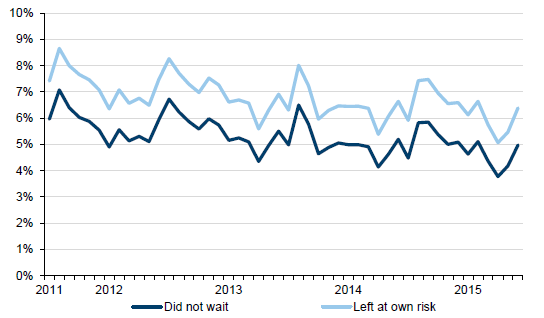

3.4 Not waiting for treatment

The proportion of patients who did not wait for treatment in EDs fell between 2011 and 2015, as shown in Figure 3E. 'Did not wait' rates are often an indicator of both long waits in the ED and how well staff communicate wait times to patients.

Some hospitals are working to better communicate expected wait times in EDs and to patients throughout their stay. This can affect a patient's decision to wait, particularly in the case of non-urgent presentations. As would be expected, ED staff report that 'did not waits' increase when demand is high and waits in the ED are long.

Figure 3E

Percentage of ED presentations who 'did not wait' or 'left at own risk', July 2011 to June 2015

Source: VAGO, based on data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

4 Support for hospital emergency departments

In August 2015, the Department of Health & Human Services (the department) published a performance monitoring framework, High-performing Health Services, which sets out how it monitors health services in five key areas. In July 2016, the department updated this framework.

Performance data is derived from the Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset (VEMD). Emergency staff record the critical times in a patient's journey in the VEMD. Performance data is regularly circulated to health services so that they can benchmark their performance. The department also coordinates a number of networks and projects designed to help hospitals keep up to date with the latest research and best practice.

In this Part, we look at how the department supports the performance of hospital emergency departments (ED) and oversees the VEMD.

4.1 Conclusion

To better understand performance, the department monitors ED access and timeliness indicators as part of its hospital performance monitoring framework. The department increases engagement where an ED's performance is poor, but for some chronically underperforming EDs it is unclear whether the department's intervention has helped improve performance.

The department routinely examines VEMD data for consistency and accuracy, but its approach to resolving problems with data integrity is inadequate. The department does not investigate data integrity issues rigorously or provide assurance that identified issues are adequately resolved.

The department helps health services to share good practices that have been proven to improve patient flow.

4.2 Performance management

The department's performance monitoring framework for health services covers ED performance and a range of areas that support and influence a health service's performance. The framework outlines clear triggers for the department to intervene when performance is poor and allows hospitals to compare performance with their peers against a range of benchmarks. However, some hospitals persistently underperform against emergency care indicators, and we could not assess whether the department's increased support for those hospitals was useful.

4.2.1 Performance framework

The department rates health services quarterly, using a performance assessment score (PAS). PAS and performance results are circulated to health services quarterly, helping them to compare their performance and identify services that are improving. ED performance is only one part of a health service's overall score and is rated against access and timeliness indicators. The department categorises health services based on their PAS:

- standard monitoring (PAS >=70)

- performance watch (PAS 50–69)

- intensive monitoring (PAS <=49).

The department holds quarterly health service performance meetings with senior staff from health services that achieve a 'standard monitoring' rating. Health services that receive a poor PAS ('performance watch' or 'intensive monitoring') are subject to more frequent performance meetings. Intensive monitoring should involve monthly meetings and improvement plans that outline how the health service will address performance weaknesses. However, we found little evidence of improvement plans until recently.

To encourage open dialogue at these performance meetings, the department does not take minutes. However, this makes it difficult for the department to demonstrate that it has agreed to specific actions to assist health services to improve their performance.

In July 2016, the department introduced a new performance management framework that better targets underperformance and requires more assurance that health services are actively addressing performance matters. Three of the access and timeliness key performance indicators (KPI) in the PAS now have conditions that must be met, such as patients having ED stays of less than 24 hours. If a health service fails to achieve these KPIs, it will lose PAS points, which will affect the level of monitoring applied by the department. By introducing 'must achieve' access and timeliness KPIs, the department is now placing greater emphasis on these particular measures of health service performance.

Performance in the sample group

We looked at a sample of four hospitals from the major metropolitan peer group. The department acknowledges that it accepted poor access performance from an ED in the audit sample for two years while it focused on improving performance in another part of the hospital. The department argued that driving performance improvement in one area would likely lead to improvement in a number of areas. However, this hospital did not show any flow-on improvement.

During the two years, the hospital's ED performance continued to be significantly poorer than that of its peers. Despite this, the department did not request any action to improve this underperformance. In this case, timely access to emergency care might have been compromised for gains in another area of the hospital's performance.

Although the hospital's ED performance against the four-hour target improved during 2015–16 and the hospital is now redesigning its approach to patient flow, the department's previous oversight and performance management was inadequate for ensuring timely access to emergency care at this hospital.

4.3 Sharing best practice initiatives

The department facilitates networks to share best practice initiatives between health services and improve patient flow. ED staff told us that they found the networks useful, but not all hospitals are making the most of these opportunities.

The Emergency Care Clinical Network (ECCN) comprises health service clinicians and is supported by the department. ECCN helps to develop initiatives to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of emergency care and broadcasts the results to health services. Staff at hospitals in the audit sample spoke positively about these initiatives.

The department also supports the Health Service Access Managers Group and Emergency Access Reference Group. The Health Service Access Managers Group meets quarterly to discuss strategies for improving patient flow in health services and the wider health system. The group discusses efficient bed management, different approaches to improving patient flow throughout a hospital, and processes to alert staff about 'access block', which occurs when in-patient wards do not have enough beds to meet demand.

The Emergency Access Reference Group advises the department on ED access and patient flow matters and ways to improve. The group aims to improve access throughout the health system and has the potential to contribute to better planning of patient flow throughout the state.

Sharing and introducing strategies that other hospitals use effectively can help to increase patient flow. However, it is evident that some health services are not benefiting fully from these opportunities and resources. It is not clear whether this is because it is difficult for health services to incorporate new strategies or whether some health services are less engaged, or a combination of both. By promoting knowledge sharing in a more targeted way, the department can help underperforming health services find ways to improve patient flow.

4.4 Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset

The department uses time stamps recorded in the VEMD to generate data on the timeliness of patients' access to emergency care and help determine how an ED is performing. VEMD use is outlined in a user manual, which is reviewed annually.

VEMD data must be recorded accurately to give the department sufficient oversight of patient care and health service performance. However, the department does not adequately investigate how data integrity issues identified during audits are resolved within health services, limiting its ability to ensure the integrity of the VEMD.

4.4.1 Data audits and integrity issues

The VEMD audit program was first tested in 2007 and was set up on an ongoing basis in 2009. The ongoing audit program met a recommendation in our audit Access to Public Hospitals: Measuring Performance and is designed to validate the accuracy of data about emergency presentations.

Every health service is audited once every three years. Auditors check hospital data for consistency with the department's dataset. They also check the data processes that health services use for consistency with the VEMD manual and the department's data integrity policies. The department's oversight of VEMD audit recommendations has been inconsistent, and has led to repeated recommendations for some hospitals.

The department continually validates consolidated data from health services and can adequately identify data errors. This involves checking that all mandatory fields have date stamps, scanning for incorrect use of codes, and reconciling patient discharge times with times in other datasets, such as the Victorian Admitted Episodes Dataset for in‑patients.

The department has provided health services with a computer program that identifies errors before they are submitted. Hospitals in the audit sample told us that they were able to identify and satisfactorily resolve unintended errors.

A VEMD reference group is responsible for reviewing VEMD audit findings, business rules and data definitions to ensure that they are consistent with ED management practice. The reference group also makes recommendations on ways to improve data quality. However, the department has not acted on these recommendations in a timely way, resulting in unclear triage time reporting from 2012–13 to 2014–15. Due to delayed and ineffective resolution of these matters, the department has not been using the VEMD audit process efficiently.

The department requests annual updates from health services on their progress in addressing VEMD audit recommendations. However, the updates are self-attested. With this weak evidentiary standard, the department has only limited assurance that problems with the data have been resolved.

Since 2010, the department's audits have consistently found that, in many health services, data entry and data validation duties are inadequately segregated. Not segregating duties increases the risk of data error and manipulation—a risk that we identified in our 2009 audit Access to Public Hospitals: Measuring Performance. Two hospitals in the audit sample had centralised data units that did not have a dedicated staff member who had knowledge of the VEMD. This creates a significant risk to the accuracy of reported data and the knowledge base of the health service.

The department advised that it is aware of shortcomings in its approach to overseeing hospitals' actions to address VEMD audit recommendations. The department also advised that it is moving to a risk-based approach that focuses more on health services with identified problems and less on hospitals that have performed well. Given the persistence of issues relating to consistent and robust data recording, we caution the department against moving towards a risk-based approach. The department must ensure that reducing the scope and coverage of VEMD audits does not compromise the integrity of the dataset.

The VEMD can be made more useful by the inclusion of more mandatory data fields. For example, a mandatory requirement for health services to consistently differentiate between planned and unplanned ED presentations would allow unplanned re‑presentations to be more reliably examined and would strengthen reporting on the effectiveness of care.

Appendix A. Audit Act 1994 section 16—submissions and comments

Introduction

In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Health & Human Services and 30 health services for submissions and comments.

Responsibility for the accuracy, fairness and balance of those comments rests solely with the agency head.

Responses were received as follows:

- Department of Health & Human Services

- Alfred Health

- Barwon Health

- Bass Coast Health

- Eastern Health

- GV Health

- Latrobe Regional Hospital

- Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital

- Royal Women's Hospital

- Western Health

- Wimmera Health Care Group

RESPONSE provided by the Secretary, Department of Health & Human Services

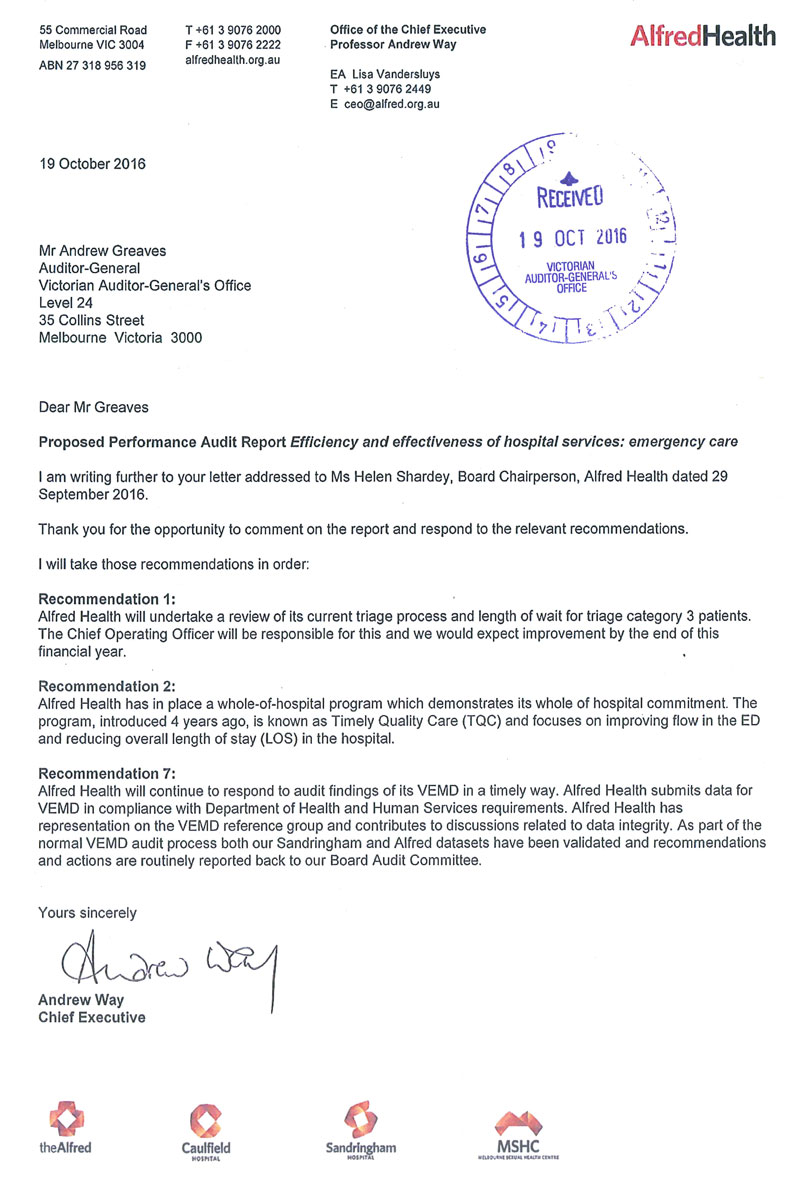

RESPONSE provided by the Chief Executive, Alfred Health

RESPONSE provided by the Chair, Barwon Health

RESPONSE provided by the Chief Executive Officer, Bass Coast Health

RESPONSE provided by the Chief Executive, Eastern Health

RESPONSE provided by the Interim Chief Executive Officer, GV Health

RESPONSE provided by the Chief Executive, Latrobe Regional Hospital

RESPONSE provided by the Chief Executive Officer, Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital

RESPONSE provided by the Executive Director, Clinical Operations, Royal Women's Hospital

RESPONSE provided by the Chief Executive, Western Health

RESPONSE provided by the Chief Executive, Wimmera Health Care Group