Freedom of Information

Overview

The audit examined the extent to which the 11 Victorian public sector (VPS) departments and Victoria Police meet the requirements of the Freedom of Information Act 1982.

Freedom of Information (FOI) is a cornerstone of a thriving democracy.

Since FOI legislation was introduced 30 years ago, Victoria has gone from being at the forefront of FOI law and administration to one of the least progressive jurisdictions in Australia. Over time, apathy and resistance to scrutiny have adversely affected the operation of the Act, restricting the amount of information being released. As a result, agencies are not meeting the object of the Act, which is ‘to extend as far as possible the right of the community to access information’.

The public’s right to timely, comprehensive and accurate information is consequently being frustrated. The VPS’s systemic failure to support this right is a failure to deliver Parliament’s intent.

The prevailing culture and lack of transparent processes allow principal officers—secretaries and chief executive officers of agencies—to avoid fulfilling their responsibilities. Principal officers are not being held to account for their agency’s underperformance and non-compliance. Agencies are routinely disregarding the 45- day statutory time limit for processing requests and the five-day ministerial noting period, and there are serious flaws in record keeping practices and FOI searches in the Department of Human Services and Victoria Police.

The Department of Justice has not satisfactorily fulfilled its role as lead agency for FOI. More effective leadership is required to promote an appropriate culture, improve transparency of government information and adequately inform Parliament and the community about FOI.

Freedom of Information: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER April 2012

PP No 125, Session 2010–12

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Freedom of Information.

Yours faithfully

![]()

D D R PEARSON

Auditor-General

18 April 2012

Audit summary

Background

Freedom of information (FOI) is a cornerstone of a thriving democracy. FOI upholds the public’s fundamental right to access information held by the government. The community’s ability to scrutinise public sector activities and hold the government of the day accountable for its decisions is affected by the transparency and accessibility of government information.

Since the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (the Act) was introduced, both the number and the complexity of requests for information have increased considerably. In 2010–11 there were 34 052 FOI requests, compared to 4 702 requests in 1984–85, the first full year the Act was in operation.

The Victorian Ombudsman identified systemic problems in his 2006 review of FOI. These included a lack of timely responses, inconsistent application of the Act and lost or non‑existent documents. In his 2011 Annual Report the Ombudsman concluded that these problems still remained five years later.

The audit examined the extent to which all 11 Victorian public sector departments and Victoria Police meet the requirements of the Act and associated guidelines. A detailed assessment of the effectiveness and efficiency of FOI processes in Victoria Police and the Department of Human Services (DHS) was also performed. These two agencies were selected because they process 68 per cent of the FOI requests received by the 12 agencies audited.

Conclusions

Since FOI legislation was introduced 30 years ago, Victoria has gone from being at the forefront of FOI law and administration to one of the least progressive jurisdictions in Australia. Over time, apathy and resistance to scrutiny have adversely affected the operation of the Act, restricting the amount of information being released. As a result, agencies are not meeting the object of the Act, which is ‘to extend as far as possible the right of the community to access information’.

The public’s right to timely, comprehensive and accurate information is consequently being frustrated. The Victorian public sector’s systemic failure to support this right is a failure to deliver Parliament’s intent.

The prevailing culture and lack of transparent processes allow principal officers—secretaries and chief executive officers of agencies—to avoid fulfilling their responsibilities. Principal officers are not being held to account for their agency’s underperformance and non-compliance:

- In 2010–11, the average response time for eight of the 12 audited agencies exceeded the statutory deadline for responding to applicants’ requests.

- Of these agencies, four exceeded the 45-day time limit for over half of their requests.

- None of the agencies adequately complied with the mandatory reporting requirements of the Act.

- The principal officers of the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC), the Department of Health (DOH) and DHS have not managed adherence with ministerial noting periods consistent with the Attorney-General’s 2009 Guidelines on the Responsibilities and Obligations of Principal Officers and Agencies (the FOI Guidelines). This has led to delays in the release of documents.

- Agencies have not managed to reach agreement on a consistent, whole‑of‑government approach to the proactive release of information, which would reduce the reliance on FOI processes for the release of non-personal information.

- The more detailed review of DHS and Victoria Police revealed serious flaws in record keeping practices and FOI searches.

The cumulative effect of the multiple cultural and process issues is that the community does not receive the information it is entitled to receive, when it should receive it. Agency senior management is aware of these longstanding issues and their consequences, but has not taken sufficient action to address these systemic weaknesses.

This points to an absence of leadership and responsiveness, and a willingness of agencies to compromise the fundamental public service principles of integrity, accountability and respect. These are values that all public sector officials are expected to demonstrate under the Code of Conduct for Victorian Public Sector Employees. Principal officers who do not observe these values are failing the community and Parliament.

Embedding the appropriate pro-disclosure culture and processes, which underpin the intent of the Act, requires effective leadership. The Department of Justice (DOJ) has not adequately championed FOI across the public sector and, as such, has not satisfactorily fulfilled its role as the lead agency for FOI.

The introduction of the FOI Commissioner presents an opportunity for more proactive FOI leadership—in particular driving the cultural shift that is necessary to provide better quality services to the community. Significant change will only be possible if the commissioner is granted sufficient powers and resources. Since these amendments have not yet commenced, recommendations relating to the lead agency for FOI are addressed to DOJ, but will subsequently need to be reviewed once the FOI Commissioner has been appointed.

Findings

Department of Justice leadership

As the lead agency for FOI, DOJ is accountable for providing agencies with guidance and advising the minister responsible for the administration of the Act through the production of annual reports to Parliament on FOI performance. There have been significant shortcomings in the department’s approach in both of these areas.

Freedom of information culture and practices

DOJ has not adequately promoted and modelled the intent of the Act and accepted better practice, either in its own department or across the public sector. Specifically, DOJ has not:

- developed a proactive release framework for agencies

- addressed its own or other agencies’ processing delays

- complied with the reporting or timeliness requirements of the Act, nor encouraged other agencies to do so

- complied with the five-day ministerial noting time frame before documents are released.

The tolerance of these longstanding substandard practices, particularly with regard to proactive release, reflects an apathetic and obstructive culture. DOJ has acknowledged that it could have taken a stronger approach with agencies, but stated that its ability to address substandard practices is limited because it does not have adequate powers to mandate good practices. This lack of powers is not sufficient justification for DOJ to not exercise leadership. Further, there is no evidence that DOJ sought to extend its powers to address its inability to achieve an acceptable level of practice, consistent with the object of the legislation.

Proactively releasing information is an effective means of disseminating the maximum possible amount of information. It is recognised as better practice and, accordingly, is the approach adopted in other jurisdictions. Although Victorian agencies are publishing information, this does not necessarily constitute proactive release unless they have properly assessed the information to determine whether it is of significant public interest, appropriate, accurate, accessible and easy to use. This, combined with the continued reliance on formal FOI applications, means Victoria is less progressive than other jurisdictions.

Performance reporting

The apathy with regard to FOI is also evident in the reporting regime. The minister responsible for the Act relies on DOJ to collect, check and prepare data for inclusion in the FOI Annual Report to Parliament. However, DOJ is not reporting to the minister aspects of agencies’ performance as the letter and spirit of the Act requires.

DOJ does not report on measures that are explicitly specified in the Act, including disciplinary action taken against officers in respect to the administration of the Act, such as a breach of duty or misconduct.

DOJ collects information on the timeliness of agencies’ responses to FOI requests but does not include this information in the minister’s report to Parliament. Although DOJ is not specifically required to disclose this information to the minister, it is not precluded from doing so. Releasing agencies’ timeliness statistics would be in the spirit of the Act and encourage better performance.

Parliament and the public have the right to know if agencies’ performance is unsatisfactory. DOJ’s lack of comprehensive and transparent reporting in relation to the minister’s annual report does not satisfy the community’s expectations of a public sector agency.

Training

Training is an effective way to instil a positive FOI culture in agencies and to emphasise the importance of openness and transparency. DOJ’s FOI training program places too much emphasis on basic administrative process, rather than the intent of the Act. An important opportunity to promote a positive pro-release FOI culture has been missed.

Agency management

Timeliness of response is a good indicator of senior management’s attitude towards the importance of FOI. The number and complexity of requests can influence performance against the statutory time limit, however, the onus is on principal officers to provide adequate resources and support to meet the timeliness requirements. Only two of the audited agencies meet both the 45-day time limit and the five-day ministerial noting period.

Of the 12 agencies audited, only four had average request processing times that met the 45-day statutory limit in 2010–11. These were the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, Department of Transport, Department of Primary Industries and Department of Treasury and Finance. The worst performing agencies were Victoria Police, DPC and DHS, which averaged 98, 92 and 75 days respectively.

Victoria’s underperformance against its legislative target is even more concerning when compared with other states. Other states have better processing completion rates against shorter or similar standard time limits. Extensions to these time limits may be granted, in certain circumstances.

The five-day ministerial noting period recommended in the FOI Guidelines was exceeded by eight of the 12 agencies. The worst performing department was DPC, with an average noting period of 41 days. One FOI request was with the Office of the Premier for 88 days. DHS and DOH also recorded noting periods in excess of 20 days. Long noting periods delay the release of information and impede the effective operation of the Act.

When agencies do not respect the FOI Guidelines, this not only compounds the delays in processing FOI requests but also contributes to the public perception that there is political interference in the FOI process, particularly when there is repeated consultation between an agency and a minister’s office on requests.

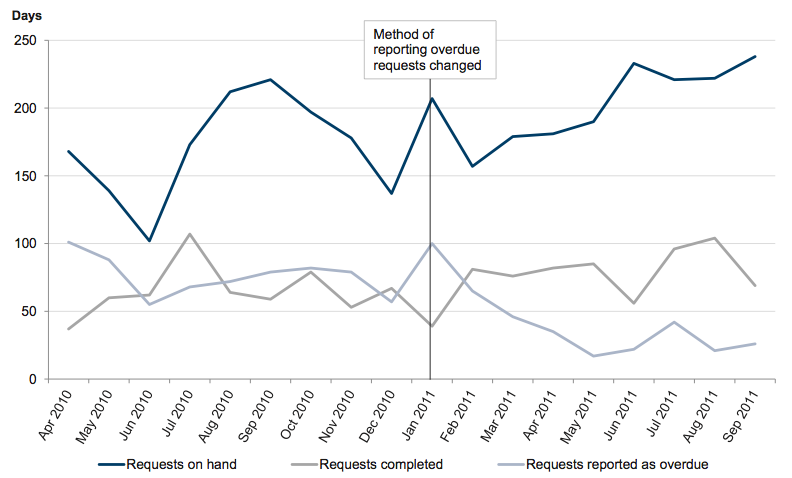

Victoria Police and DHS have both attempted to improve the timeliness of their responses. At Victoria Police, timeliness improved when additional resources were temporarily assigned to the FOI unit, while DHS improved its response time by prioritising requests.

Department of Human Services and Victoria Police

An effective FOI system relies on strong agency leadership and support, a robust understanding and application of the Act, good records management, appropriately defined searches and open communication with applicants.

DHS and Victoria Police, the two agencies reviewed in more detail, have significant deficiencies in these areas. As a consequence, the public is being denied access to information.

Processing fees and waiver of time frame

DHS is offering applicants the opportunity to waive processing charges if they forgo the requirement for DHS to meet the 45-day processing time limit. DHS is not advising applicants who have little or no money and are seeking information that relates to their personal affairs that they have a right to request a waiver of charges under the Act without waiving the 45-day time limit.

This unacceptable practice was not observed in any of the other audited agencies. It allows DHS to extend its time frame for responding to requests without recording those requests as overdue, giving the mistaken impression that the department’s timeliness performance is better than it actually is.

Records management

DHS and Victoria Police need to address deficiencies in their record keeping practices as a priority. Records are being lost, disposed of incorrectly or rendered inaccessible.

DHS’s record management facility has inappropriate physical storage conditions—causing records to deteriorate—and inefficient indexing systems. As a result, information cannot be found when needed.

Although Victoria Police has a policy outlining the appropriate storage of records, it has not addressed the informal practice of police officers storing records, such as note books, at their homes. This practice increases the likelihood that these records may be lost or difficult for Victoria Police to locate.

Search techniques

DHS and Victoria Police both need to remedy weaknesses in their FOI searches to provide appropriately scoped responses.

DHS does not include records held by its contracted community service organisations (CSO) in the FOI requests the department processes. Instead, DHS refers applicants to the relevant CSOs. The quality of record keeping practices of CSOs varies widely and, consequently, so does the amount of information available to DHS’s clients.

DHS is failing to discharge its obligations to its clients. The Act refers to ‘possession’ when defining a document, not ownership. DHS has a right to possess CSO records under its service agreements, therefore CSO documents are subject to the Act. Furthermore, the department is contravening the specifications set out by the Public Records Office Victoria and the FOI Guidelines.

Victoria Police’s FOI unit does not conduct sufficiently thorough and diligent searches. The unit does not inspect proof of disposal documents to confirm whether documents cannot be provided because they no longer exist.

Communication with applicants

DHS employs specialists to assist clients with child protection and ward of the state requests. These officers discuss the applicants’ needs, which enables them to scope requests to better meet applicants’ requirements. This is good practice and helps DHS redefine requests to better provide applicants with the information they need. DHS also surveys applicants to promote continuous improvement.

Although internal reviews upheld the original decision in 79 per cent of cases in the 12 audited agencies, it is unknown how many FOI applicants are dissatisfied with the outcome of their request but did not appeal the decision, either out of choice or ignorance of their rights. The in‑depth review of Victoria Police’s practices revealed applicants are not being appropriately advised of their right to complain to the Victorian Ombudsman or appeal decisions. This is contrary to legislative requirements.

Victoria Police could provide clearer information on its website on those areas where information is released outside of the Act. For instance, motor vehicle accident information can be purchased outside of the Act and information for court proceedings can be obtained through subpoenas. Clearer communication would reduce the number of requests for these types of information that are currently incorrectly made under FOI.

Recommendations

-

The Department of Justice should provide stronger leadership in acquitting its statutory obligations to Parliament by:

- reviewing the Freedom of Information Act 1982 to improve its currency and to champion the proactive release of information

- overhauling the content and frequency of current reporting requirements

- providing detailed guidance on proactive disclosure for agencies

- providing more comprehensive and tailored training.

-

Principal officers of agencies should diligently discharge their responsibilities under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 by:

- improving the transparency of their processes

- maximising the information made available to the public through a proactive release framework.

-

Principal officers should:

- promote the appropriate ‘tone at the top’ with regard to the object of the Freedom of Information Act 1982

- monitor their performance against the requirements of the Freedom of Information Act 1982, the Attorney‑General’s 2009 Guidelines on the Responsibilities and Obligations of Principal Officers and Agencies and related policies and procedures, identify areas of underperformance or non-compliance and remedy any shortcomings

- review the support and guidance they provide to confirm their agency is meeting its obligations under the Freedom of Information Act 1982.

-

Agencies should:

- seek to continually improve their processes to comply with the 45-day statutory time limit for processing freedom of information requests

- routinely release information on day six of the ministerial noting period.

-

The Department of Justice should drive continuous improvement by, in the longer term, giving consideration to adjusting the statutory time frame in line with other Australian jurisdictions.

-

The Department of Human Services should:

- improve its record management practices to minimise loss of documents and enhance access to information

- cease its practice of using section 22(6) for clients who have little or no money and are seeking their own records

- include community service organisations’ records when processing freedom of information applications

- improve its method of prioritising freedom of information requests.

-

Agencies should review the findings relating to the Department of Human Services and apply lessons where necessary in their own organisation.

-

Victoria Police should:

- improve its record management practices to minimise loss of documents and enhance access to information

- improve its responsiveness by reviewing its work practices in the first instance, and then, if necessary, considering the resources of its freedom of information unit

- appropriately scope freedom of information requests

- inform freedom of information applicants of their review rights.

-

Agencies should review the findings relating to Victoria Police and apply lessons where necessary in their own organisation.

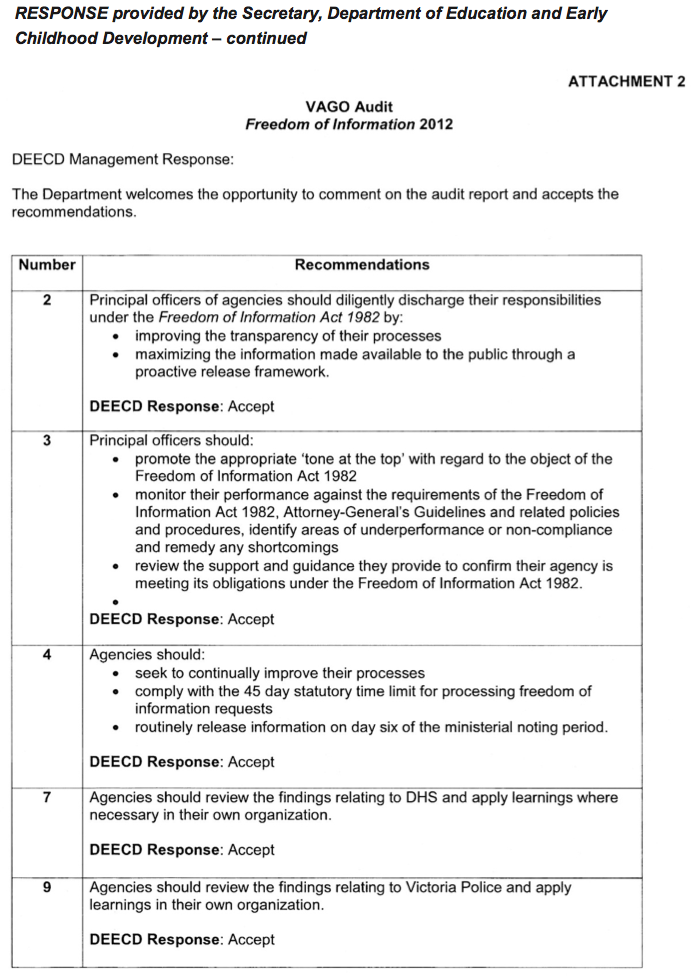

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Business and Innovation, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, the Department of Health, the Department of Human Services, the Department of Justice, the Department of Planning and Community Development, the Department of Premier and Cabinet, the Department of Primary Industries, the Department of Sustainability and Environment, the Department of Transport, the Department of Treasury and Finance and Victoria Police with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments however, are included in Appendix B.

1. Background

1.1 Introduction

Openness, accountability and transparency are fundamental principles of democratic government. The Freedom of Information Act 1982 (the Act) was designed to promote these principles in the Victorian public sector by giving the public the right to access government information.

The second reading speech of the Freedom of Information Bill advised Parliament that:

‘Freedom of information is very closely connected with the fundamental principles of a democratic society and is based on three major premises:

- The individual has a right to know what information is contained in government records about him or herself.

- A government that is open to public scrutiny is more accountable to the people who elect it.

- Where people are informed about government policies, they are more likely to become involved in policy making and in government itself’.

Government information does not belong to government. It belongs to the public to whom the government is accountable. The public can therefore rightfully expect freedom of information (FOI) practices, and public sector officials, to support and uphold the community’s democratic right to access government information.

1.2 Freedom of information legislation

The Commonwealth Government enacted the first Australian FOI legislation in 1982. Victoria was at the forefront of FOI law and administration at that time, being the first of the states to pass its own legislation.

1.2.1 Purpose of the Freedom of Information Act 1982

The object of the Act is to ‘extend as far as possible the right of the community to access information in the possession of the Government of Victoria’. This general right of access to information should only be limited when it is necessary to protect public, personal and commercial interests.

The Act applies to information held by government ministers and 1 000 public sector agencies, including departments, local councils, statutory authorities, public hospitals, universities, TAFE colleges and schools.

The Act gives members of the public:

- a legally enforceable right of access to documents in the possession of government bodies, subject to certain exemptions

- the ability to request the correction of information on personal files where this information is inaccurate or incomplete

- a right to seek a review of decisions made.

The Act also requires agencies to:

- publish information on their organisation, functions, documents, internal rules and reports

- respond to applicants within 45 days of receiving an FOI request. This time period may be extended with the applicant’s agreement.

The second reading speech of the FOI Bill also stated that, in situations where it may not be clear whether information should be released, the guiding principle should be to facilitate disclosure where possible.

In order to assist with the effective administration of FOI legislation, in December 2009 the Department of Justice (DOJ) released the Attorney-General’s Guidelines on the Responsibilities and Obligations of Principal Officers and Agencies (the FOI Guidelines). The FOI Guidelines define the principles underpinning the responsibilities of principal officers—secretaries and chief operating officers of agencies—and other participants in the FOI process. They also provide the minimum standards for FOI processes that agencies are required to follow. DOJ has also issued a set of Practice Notes to assist FOI practitioners.

1.3 Roles and responsibilities

1.3.1 Lead agency role

As the lead agency for FOI, DOJ oversees the application of FOI across the public sector. While the primary responsibility for FOI decisions rests with individual agencies, DOJ coordinates as far as possible an agreed approach to achieve consistency in the interpretation and processing of multi-agency requests. DOJ provides FOI training and prepares the Freedom of Information Annual Report, which is a statistical overview of agencies’ administration of the Act.

1.3.2 Decision-maker role

Ministers and principal officers are empowered to make FOI decisions on behalf of their agency and are responsible for overseeing their agency’s obligations under the Act. However, in practice FOI officers are authorised to make FOI decisions on behalf of the principal officer.

FOI officers across the 11 departments and Victoria Police are typically mid‑level public sector employees.

In broad terms, FOI officers are responsible for:

- consulting with applicants who are requesting information

- searching for documents and liaising with content experts and other third parties regarding the release of information

- assessing documents in accordance with the Act

- preparing letters of outcome, which contain the reasons for their decision on an FOI request, any exemptions applied and the applicants’ review rights.

1.3.3 Code of conduct

Public servants are bound by a code of conduct under the Public Administration Act 2004. The Code of Conduct for Victorian Public Sector Employees describes how public officials are expected to conduct themselves in their role. The code of conduct is particularly relevant to FOI officers, as their work requires them to interact directly with the public and make important judgements on the release of information.

The code of conduct directs public officials to demonstrate values including:

- responsiveness—by providing high quality services to the Victorian community, and identifying and promoting best practice

- integrity—by being honest, open and transparent, using powers responsibly, and striving to earn and sustain public trust of a high level

- impartiality—by making decisions and providing advice on merit and without bias, caprice, favouritism or self-interest

- accountability—by accepting responsibility for their decisions and actions,submitting themselves to appropriate scrutiny, and respecting colleagues, public officials and members of the Victorian community by treating them fairly and objectively

- leadership—by actively implementing, promoting and supporting these principles.

There are also special requirements, in the code of conduct, that apply to information that may be called upon under FOI legislation. Public sector employees are required to:

- handle official and personal information according to relevant legislation and public sector body policies and procedures

- maintain accurate and reliable records as required by legislation, policies and procedures. These records are to be kept in a way that assures their security and reliability, and allows them to be made available to appropriate scrutiny when required.

1.4 Number, nature and complexity of requests

According to DOJ’s annual report on FOI, 34 052 requests for information were made in 2010–11. This is a substantial increase of 624 per cent since the first record of FOI requests in 1984–85.

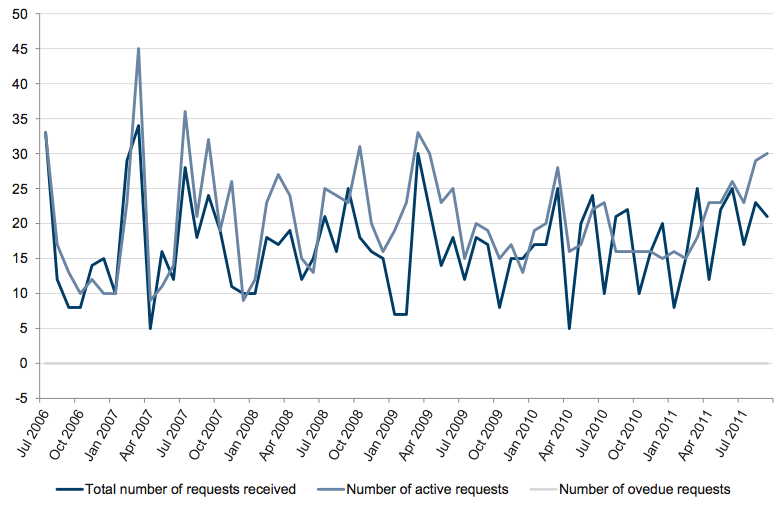

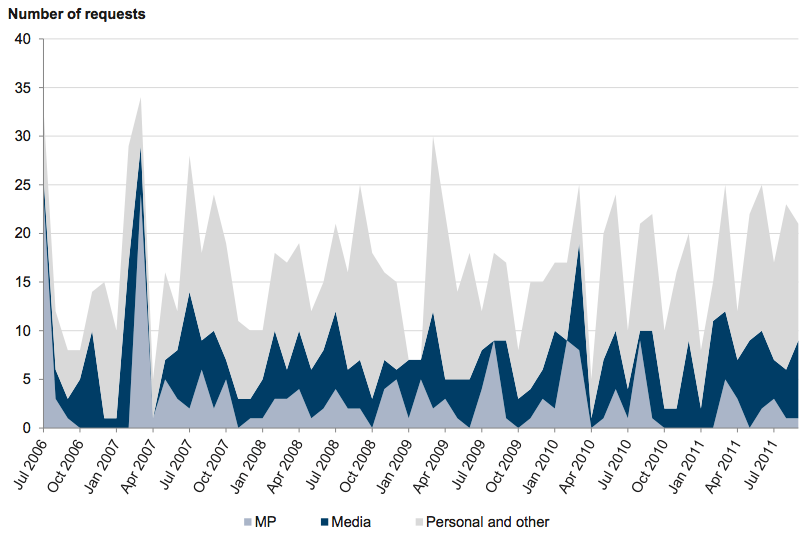

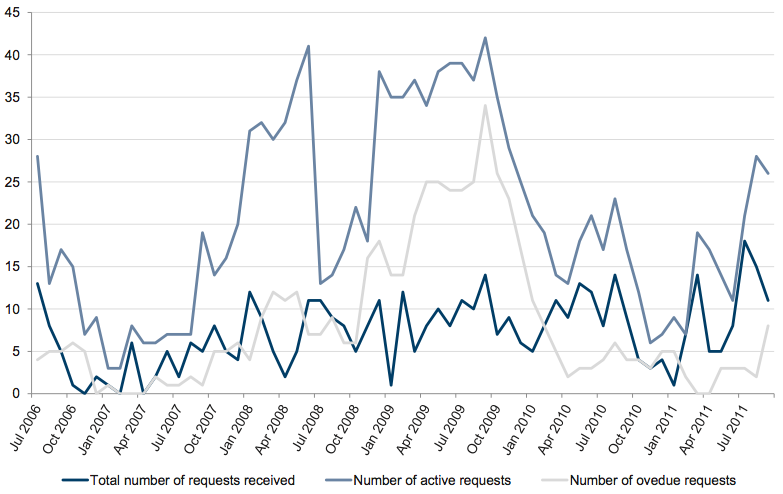

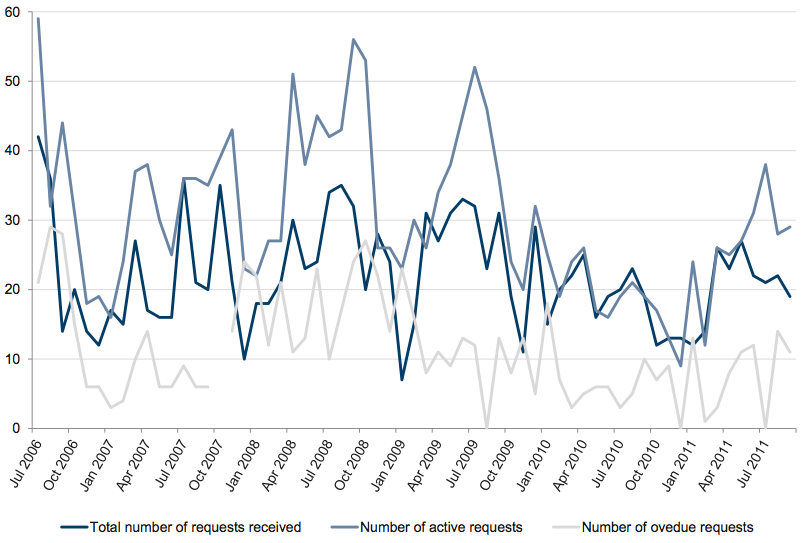

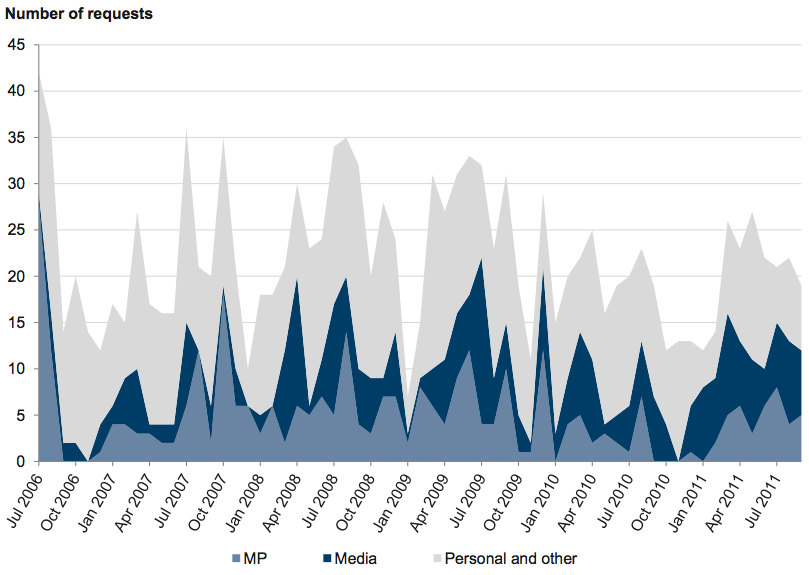

There is considerable variation in the number, nature and complexity of FOI requests received by agencies:

- Of the 5052 FOI requests received by the 12 agencies subject to this audit, 2381 were sent to Victoria Police (47 percent), 1047 to DHS (21 percent) and 546 to DOJ (11 percent).

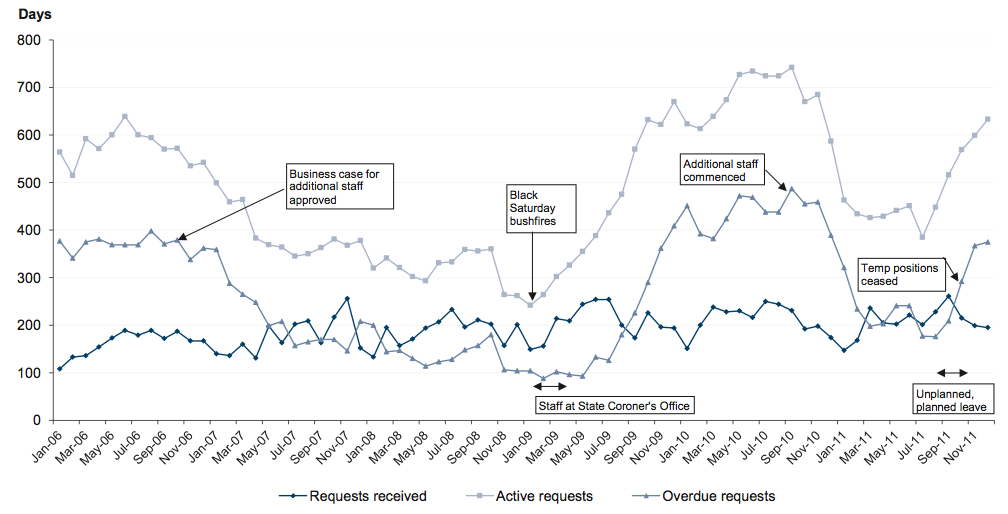

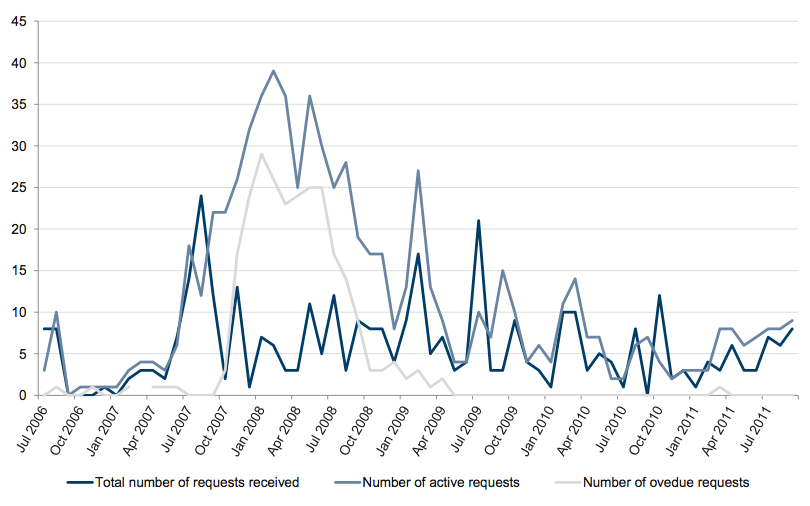

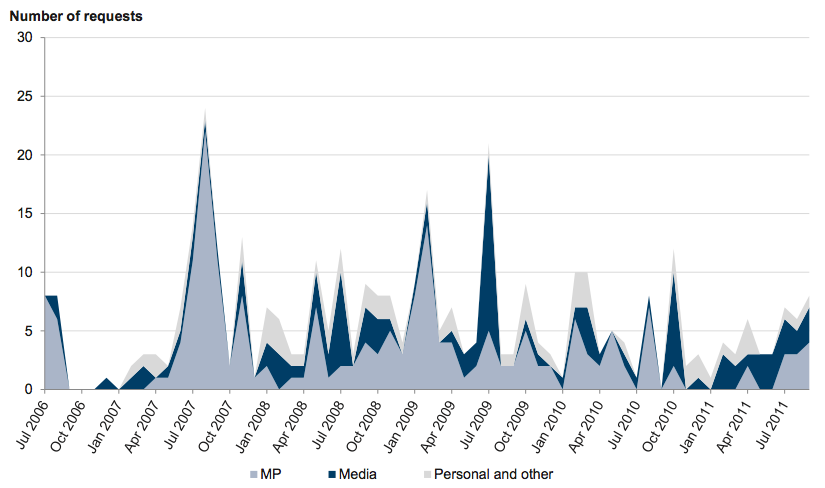

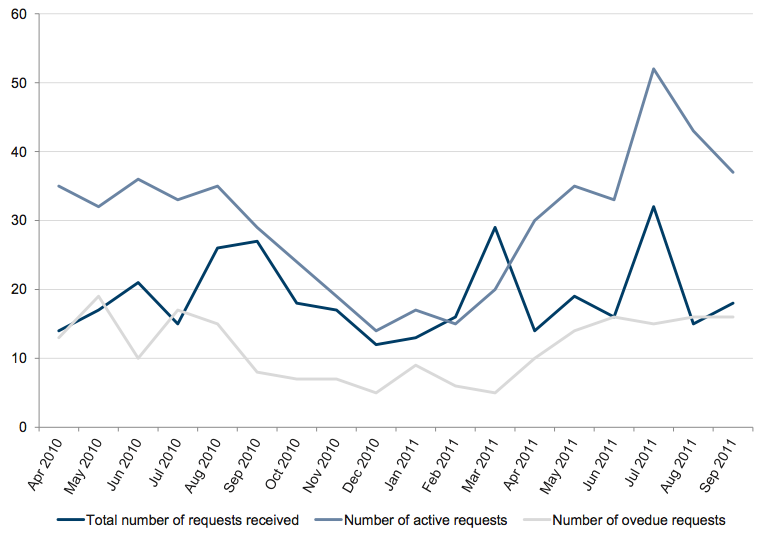

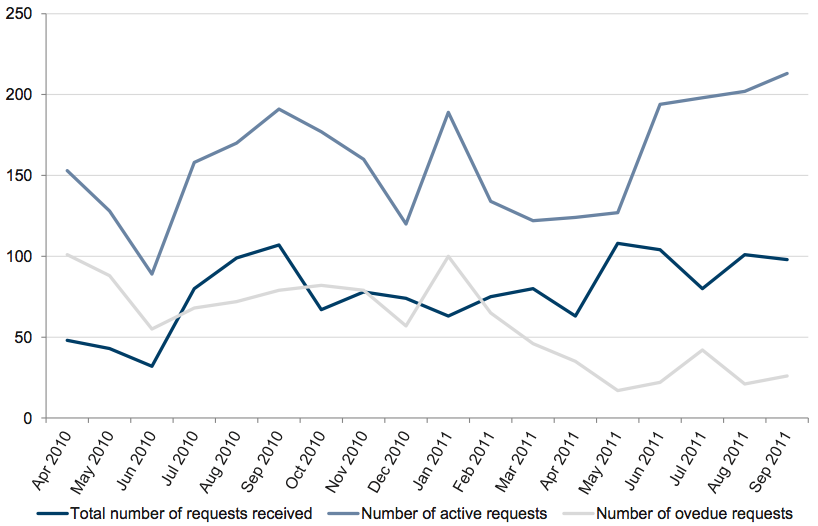

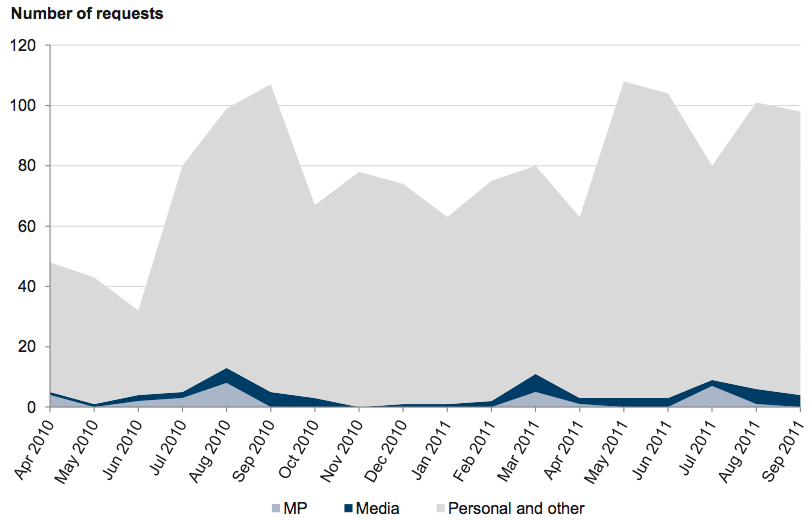

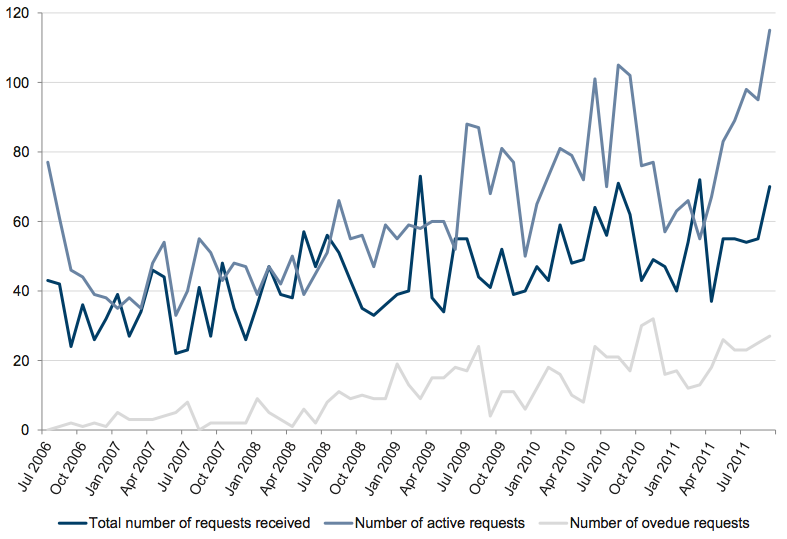

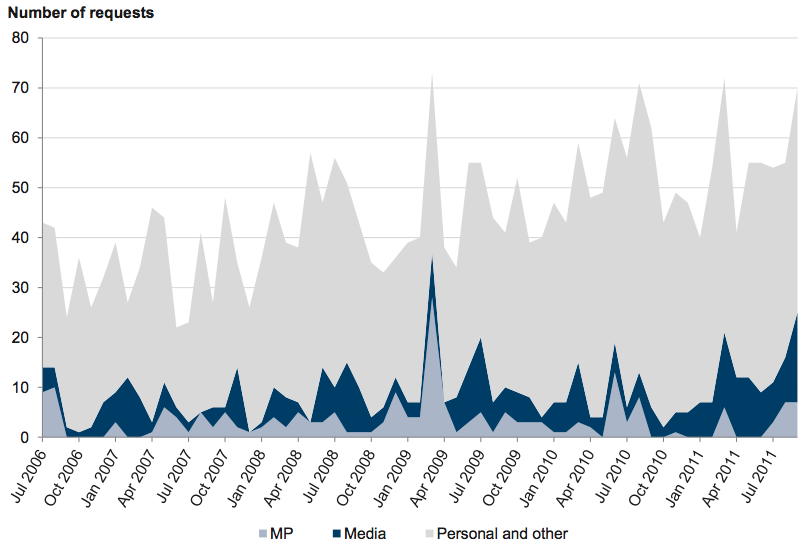

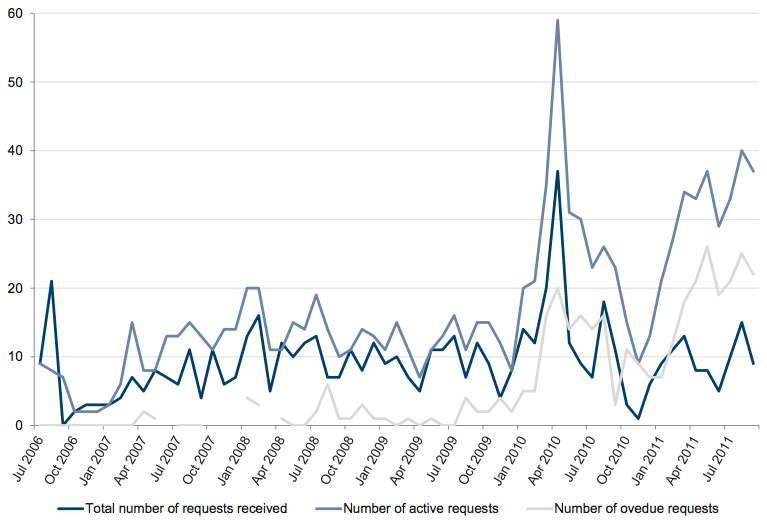

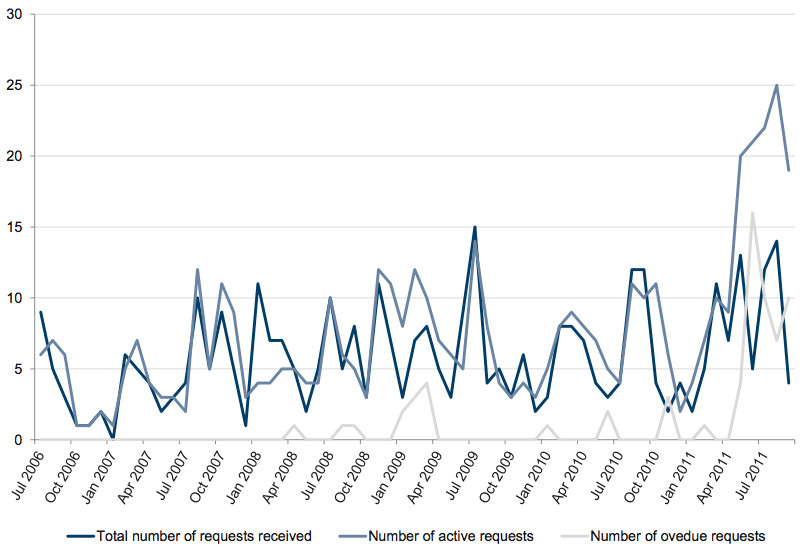

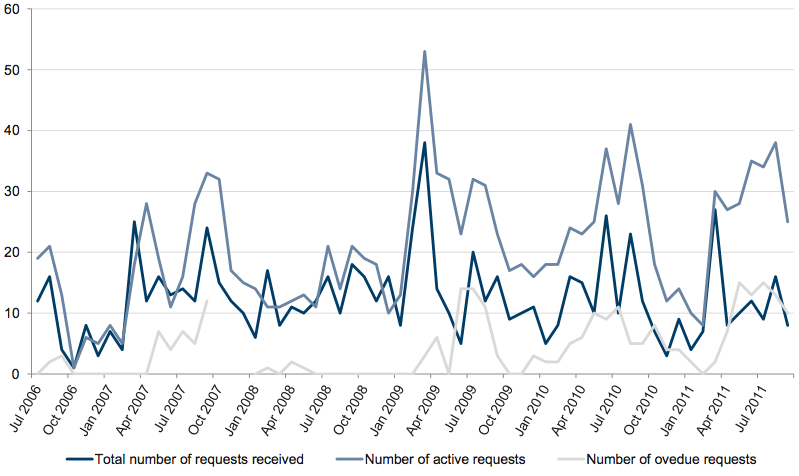

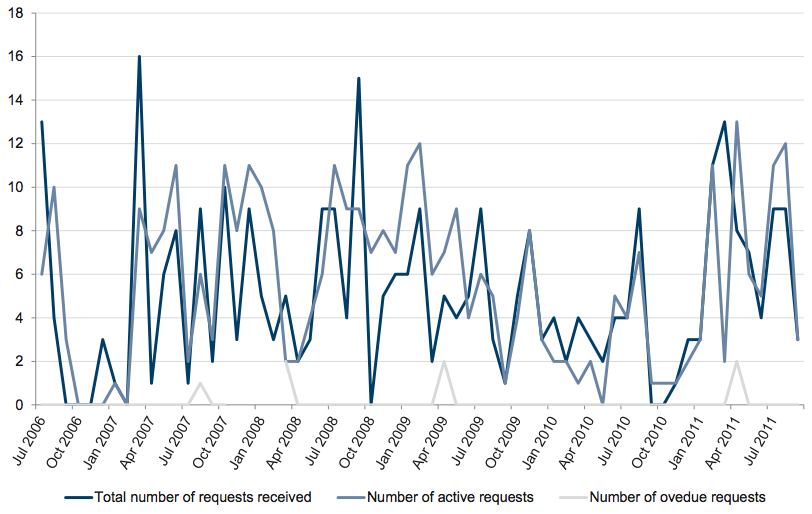

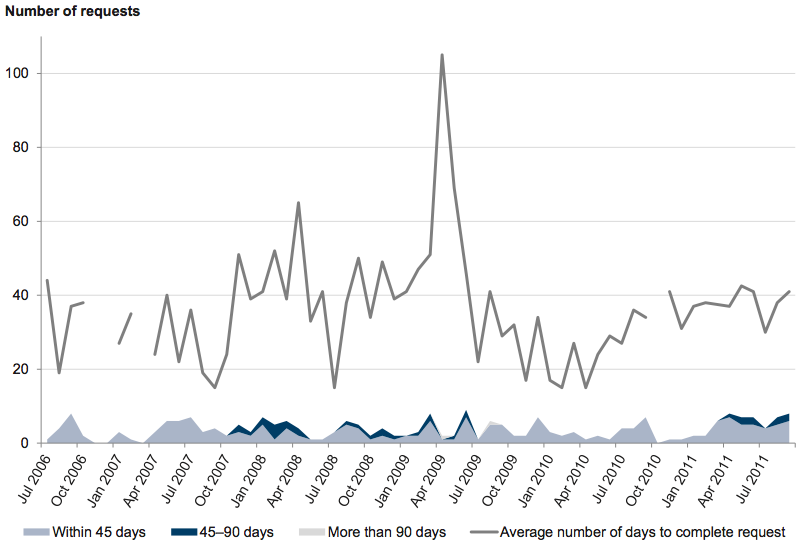

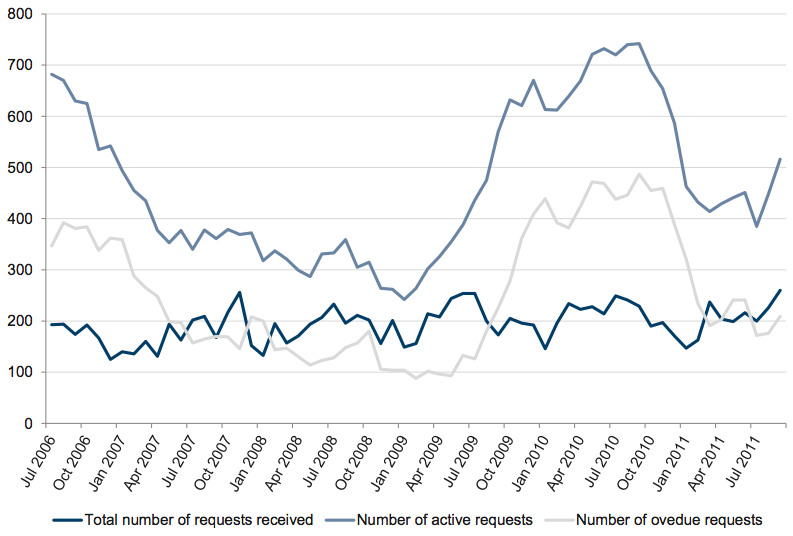

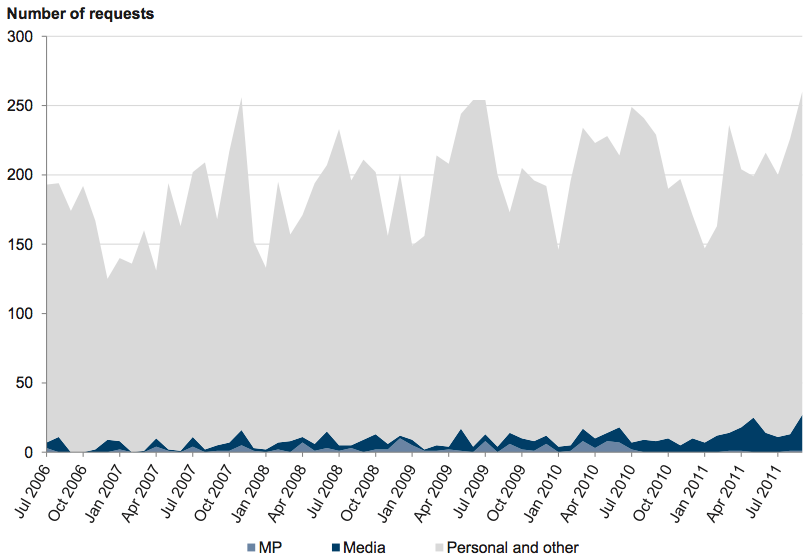

- The number of requests received varies significantly from month to month, as shown in Appendix A. This can present challenges in planning and resourcing.

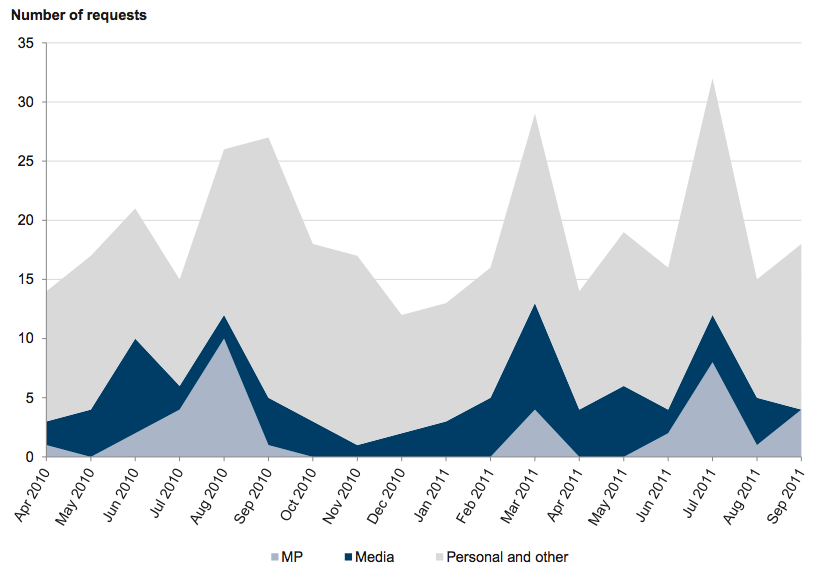

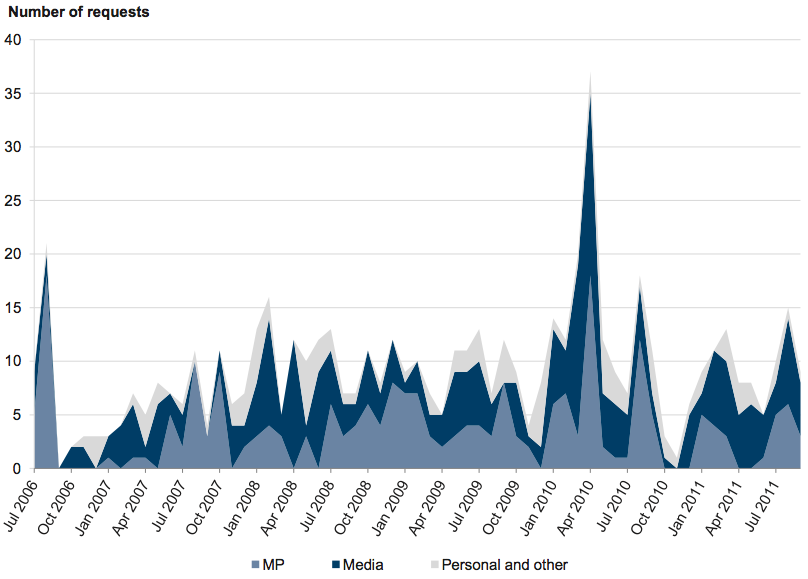

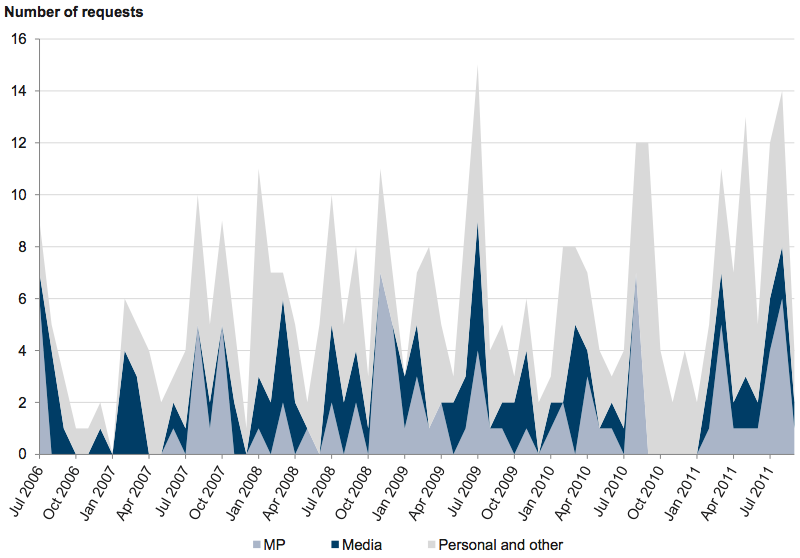

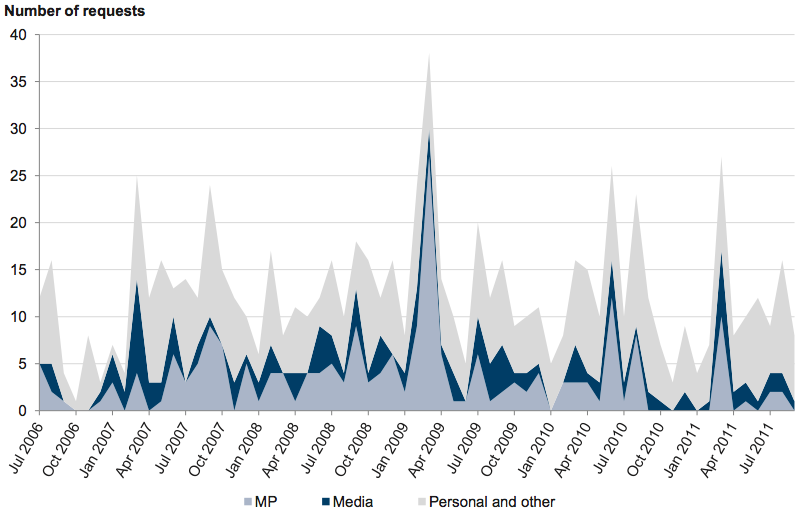

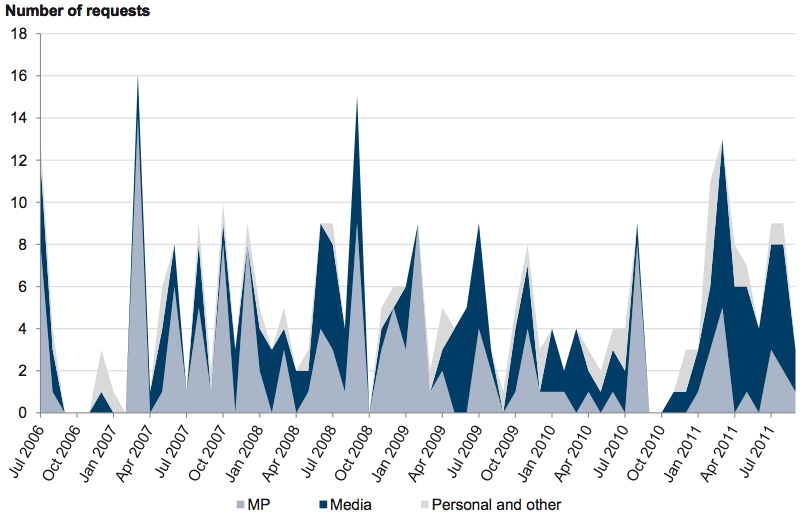

- Victoria Police, DHS and DOJ mainly receive personal requests while the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC), Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) and Department of Business and Innovation (DBI) are more likely to receive requests from the media and Members of Parliament.

- Some FOI requests are more complex than others. For example, in the case of child protection matters, FOI officers must carefully consider extensive, and sometimes complicated, family relationships.

These factors naturally have some influence on how agencies manage and resource their FOI process.

1.5 Freedom of information process

The FOI process is informed by the Act, the FOI Guidelines and DOJ’s Practice Notes.

1.5.1 Freedom of information requests

FOI requests must be made in writing, either in a letter or electronically, and an application fee and access charges apply, except in limited circumstances. The Act requires agencies to waive their fees for applicants who are deemed to have little or no money if they are seeking information regarding their personal affairs.

Agencies are required to assist applicants if the request is unclear, too broad, or if there is a more efficient way of obtaining the information.

1.5.2 Processing freedom of information requests

The nature of FOI requests differs across agencies in terms of the number of requests received, the number of pages to be analysed per request and their complexity.

Nonetheless, the steps taken to process an FOI application are essentially the same across all agencies. DOJ has developed recommended time lines for its own FOI process, as shown in Figure 1A.

Figure

1A

Stages and time lines for completing FOI requests

Stage |

Time line (calendar days) |

Action |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Receipt and acknowledgment |

Days 1–3 |

The FOI unit receives the FOI request, and checks it is clear and that the application fee has been paid or waived. |

|

Search |

Days 3–10 |

The FOI unit asks the relevant business units to conduct a document search. The business units provide the relevant documents and advice to the FOI unit. |

|

Document assessment |

Days 10–24 |

An FOI officer assesses the documents to determine what information may be released and if any exemptions should be applied. The FOI officer drafts a proposed response to the applicant. |

|

Noting by the department |

Days 24–30 |

The FOI unit sends the proposed response to the business unit’s executive director for noting. The FOI unit may also send topical requests from Members of Parliament and the media to the secretary for noting. |

|

Noting by the minister’s office |

Days 30–36 |

The FOI unit sends topical requests to the minister’s office for noting. |

|

Release |

By day 45 |

The FOI unit advises the applicant of its decision and the decision letter is sent to them along with any released information. |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor General’s Office.

1.5.3 Exemptions

Although the purpose of the Act is to make the maximum possible amount of information held by government available to the public, the Act recognises that the disclosure of certain information could have adverse effects. Consequently, exemptions may be applied to avoid releasing particularly sensitive information.

The three most common exemptions claimed by agencies in 2010–11 were:

- personal affairs (2 908 exemptions)—where releasing a document would involve unreasonable disclosure of another individual’s personal information

- internal working documents (371 exemptions)—opinions, advice or recommendations prepared by agency or ministerial staff as part of deliberations or consultations, where it is not in the public interest to release this information

- documents to which secrecy provisions apply (346 exemptions)—a document is exempt if there is a secrecy provision which prohibits the disclosure of this information.

Exemptions may also apply to voluminous requests, Cabinet documents, law enforcement information, commercially sensitive materials and documents that are subject to the secrecy provisions of other Acts.

Of the total requests received across the public sector in 2010–11, 78 per cent of applicants were eventually granted full access, 20 per cent were granted partial access and 2 per cent were denied access.

1.5.4 Right to appeal a decision

Applicants have a right to appeal when access to documentation is denied or when only partial access is granted. Applicants may:

- request an internal review of an FOI officer’s decision. Victorian public sector agencies carried out internal reviews of 400 application decisions in 2010–11. These reviews confirmed the initial decision in 70 percent of cases, varied the decision in 25percent and overturned the decision in 5percent.

- lodge an appeal with the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT). In 2010–11, 172 appeals were lodged at VCAT, 125 were withdrawn and 54 decided. VCAT confirmed agency decisions in 91 per cent of cases decided and partially upheld the decisions in 9 per cent. VCAT did not overturn any FOI decisions made by agencies. The rounding difference is due to requests being lodged and decided in different years.

- complain to the Victorian Ombudsman if the documents do not exist or cannot be located. Agencies are required to inform applicants of this right.

Responsibility for some of these actions is expected to transfer to the proposed new FOI Commissioner.

1.6 Evolution of freedom of information

In recent years, comprehensive legislative reforms regarding the release of public information have been undertaken in Queensland, Western Australia, New South Wales and by the Commonwealth government. Similar wide-ranging reforms have not taken place in Victoria since the Act was introduced in 1982.

The most significant proposed amendment to the Victorian FOI Act in recent times is the creation of the FOI Commissioner.

1.6.1 Freedom of Information Commissioner

The Freedom of Information Amendment (Freedom of Information Commissioner) Bill 2011 received Royal Assent on 6 March 2012.

The functions and powers of the FOI Commissioner as set out in the Bill are to:

- promote agencies’ understanding and acceptance of the Act and its purpose

- provide advice, education and guidance to agencies in relation to professional standards prescribed by the regulations, and monitor compliance with those standards

- provide advice, education and guidance to agencies and the public in relation to the commissioner’s functions

- conduct reviews of agencies’ decisions on applicants’ requests for information, replacing the current internal review process

- receive and handle complaints

- report on the operation of the Act

- provide advice to the minister responsible for the administration of the Act, on request, in relation to the operation and administration of the Act

- perform any other functions conferred on the commissioner under this or any other Act.

The FOI Commissioner, once appointed, will take on many of DOJ’s leadership responsibilities. Consequently, recommendations in this report that relate to DOJ’s lead agency role will naturally transfer to the FOI Commissioner. This report should serve as a basis to the FOI Commissioner’s endeavours to drive change.

Previous reviews

The Victorian Ombudsman has tabled several reports in Parliament in recent years, highlighting serious deficiencies in FOI administration.

The Ombudsman’s last comprehensive review of FOI was in 2006. The Review of the Freedom of Information Act identified a lack of timely responses, inconsistencies in the application of the Act, a refusal to provide access to information, and lost or non‑existent documents.

The Ombudsman’s Annual Report 2011 Part 1 also reported on significant and systemic concerns with the administration of the Act by government agencies. The Ombudsman commented that he continued to see significant delays and restrictive practices and that, despite assurances from agencies that processes would be improved, the same issues arise each year.

The FOI Commissioner will deal with all complaints regarding FOI matters, replacing the Victorian Ombudsman’s oversight role in this area. The FOI Commissioner does not have the coercive powers of the Ombudsman, which include summonsing people and evidence, and taking sworn evidence.

1.7 Audit objectives and scope

The audit objectives are to determine the extent to which:

- departments and agencies comply with the Act and the FOI Guidelines

- FOI is administered effectively and efficiently in selected agencies.

This audit included the 11 departments and Victoria Police, with detailed examination of two agencies: Victoria Police and DHS.

1.8 Report structure

The rest of this report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 assesses DOJ’s leadership with regard to compliance and better practice

- Part 3 examines agencies’ management of FOI

- Part 4 analyses DHS’s management of FOI

- Part 5 analyses Victoria Police’s management of FOI.

1.9 Audit method and cost

The audit was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. The total cost of the audit was $475 000.

2. Department of Justice leadership

At a glance

Background

The Department of Justice (DOJ) is the lead agency for freedom of information (FOI). It is responsible for promoting FOI better practice across the public sector and reporting agencies’ FOI performance to Parliament.

Conclusion

Victoria was at the forefront of FOI legislation and practices 30 years ago. However, it has fallen behind other states in terms of the information being released and the reporting of FOI. More effective leadership and oversight from DOJ are required to promote an appropriate pro-release culture, to improve transparency of government information and to adequately inform Parliament and the community about FOI.

Findings

- DOJ has not adequately championed the proactive release of information.

- DOJ’s preparation of the annual report to Parliament on agencies’ FOI performance does not fulfil the letter or intent of the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (the Act).

- Training for FOI officers is inconsistent and focuses on the technical application of the Act, rather than the outcomes sought by the legislation.

- There is considerable scope and opportunity for the new FOI Commissioner to improve practices and the culture.

Recommendations

DOJ should provide stronger leadership in acquitting its statutory obligations to Parliament by:

- reviewing the Act to improve its currency and to champion the proactive release of information

- overhauling the content and frequency of current reporting requirements

- providing detailed guidance on proactive disclosure for agencies.

Principal officers should diligently discharge their responsibilities under the Act by improving the transparency of their processes and by maximising the information made available to the public through a proactive release framework.

2.1 Introduction

The Department of Justice (DOJ) is the lead agency for freedom of information (FOI). It is accountable for promoting FOI compliance and better practice across the Victorian public sector (VPS).

The Freedom of Information Act 1982 (the Act), and the Attorney-General’s 2009 Guidelines on the Responsibilities and Obligations of Principal Officers and Agencies (the FOI Guidelines) provide the legislative and policy framework for FOI.

These documents promote the disclosure and dissemination of information through practices such as proactively releasing information to inform the public instead of reactively responding to individual FOI requests. The Act and the FOI Guidelines also set out the general reporting requirements on FOI operations, including a consolidated annual FOI report produced by DOJ on behalf of all VPS agencies. DOJ also provides additional guidance to help agencies interpret and apply the Act and The FOI Guidelines in the form of officer training, an FOI website and Practice Notes.

DOJ’s leadership role will largely transfer to the new FOI Commissioner following the passage into law of the Freedom of Information Amendment (Freedom of Information Commissioner) Bill 2011.

This Part examines DOJ’s leadership performance and role in setting the culture around FOI, including DOJ’s actions with regard to establishing a proactive release framework, fulfilling FOI reporting requirements and providing guidance to agencies.

2.2 Conclusion

Victoria was a leader in FOI 30 years ago. However, since then, its approach has deteriorated seriously and it is now less transparent than other jurisdictions. A lack of strong leadership by DOJ has allowed the emergence of a culture that is resistant to scrutiny. As a result, Parliament and the community are not being adequately informed about agencies’ business and the operation of FOI in the VPS.

More purposeful leadership is required to promote the proactive release of information that is of significant public interest. This approach is in the spirit of the Act and is also recognised as better practice in other jurisdictions.

DOJ’s attempts to put in place a whole-of-government proactive release framework have met with resistance from agencies. This framework presents an opportunity to improve the transparency of agencies’ operations and should be pursued. Agencies’ application of this model should be centrally monitored and action plans promptly put in place to remedy underperformance.

Progress against these plans should be followed up on a regular basis, as agencies have an unsatisfactory record of taking action to improve FOI practices. None of the 12 audited agencies implemented all of the recommendations made by the Victorian Ombudsman in 2006. This is indicative of a poor, resistant culture and low level of priority placed on FOI, which DOJ has not managed to address effectively.

Reporting practices also require more purposeful leadership and oversight. The current reporting regime is neither transparent nor robust. DOJ is tolerating disregard for the letter and spirit of the legislation, and has not led by example:

- DOJ and the 11 other agencies do not fully comply with legislative reporting requirements.

- DOJ has not taken the initiative to release information that was not required by legislation, but was in the public interest. The most notable example of this is non-reporting of agencies’ poor performance against the statutory time frame for responding to FOI requests.

While DOJ’s website and Practice Notes provide guidance to agencies, these do not replace the need for formal training. The current training is focused on basic administrative processes. DOJ should tailor the training to better suit participants’ needs and to place more emphasis on the outcomes sought by the Act. This important opportunity to promote a positive pro-release FOI culture has been missed.

The introduction of the new FOI Commissioner presents the opportunity for more proactive FOI leadership—particularly in driving the cultural shift that is necessary to provide better quality FOI services to the community.

2.3 Proactive release

The object of the Act is to release the maximum possible amount of information. Proactively releasing information, instead of responding to individual FOI requests, is an effective means of achieving this aim.

Agencies publish a significant amount of information both, in hard copy and on the internet, and particularly in the case of Victoria Police, through press conferences. However, there is a distinction between publishing information and proactively releasing information.

Proactive release involves a structured, wide-ranging assessment of the information held by an agency to determine what should be disseminated to the public and how this should be managed. The information should be of significant public interest, appropriate, accurate, accessible and easy to use. The cost to the public of obtaining the information should also be considered.

When managed effectively, proactive release increases the amount of information available to the public. This means there is less need for the public to use the FOI process, which in turn reduces agencies’ FOI workload for non-personal information requests. It is also consistent with the intent of the Act.

2.3.1 Impetus for proactive release

Legislative provisions and other directions exist to support the proactive release of information.

The Act states that ministers and agencies should make the ‘maximum amount of government information promptly and inexpensively available to the public’.

The FOI Guidelines state that ‘freedom of information applications should be a means of last resort to gain access to information on the policies and activities of government’.

The FOI Guidelines further encourage agencies to consider ways of releasing information outside the FOI process and on a regular proactive basis. Principal officers—secretaries and chief executive officers of agencies—are accountable for confirming their agency meets these requirements.

The Code of Conduct for Victorian Public Sector Employees, issued by the Public Sector Standards Commissioner, requires public officials to provide high-quality services to the Victorian community and to identify and promote better practice. Proactive release is widely regarded as better practice in other jurisdictions.

However, the lack of strong leadership and the tolerance of a culture that resists transparency mean that VPS agencies are not reflecting these directions in their current practices. Victorian agencies are less progressive than their counterparts in other jurisdictions.

2.3.2 Proactive release framework

As the lead agency for FOI, DOJ has not persistently championed the proactive release of information across the VPS.

DOJ attempted to progress a specific framework for proactive release, the Proactive Publication Scheme (PPS), in 2009. Under the scheme, agencies would publish information commonly sought under FOI, such as executive officers’ salary bonuses and expenditure on taxis. However, agencies could not agree on common templates that would allow DOJ to collate the required information and PPS stalled. DOJ has not progressed PPS since 2010.

In February 2011 work began on the development of the Public Sector Information Release Framework (PSIRF) to guide the management and release of public sector information. All 12 agencies are participants in the development of PSIRF. PSIRF could potentially provide a framework for greater proactive release across the VPS. However, more than a year after the project began, there is still no scheduled release date for this framework.

Although agencies do release large amounts of information to the public, the absence of a proactive release framework means there are inconsistencies between agencies in the information available to the public. A framework would provide a coordinated and consistent whole‑of-government approach to proactively releasing information. This would help agencies use a standard method and criteria to identify what type of information they should be releasing and how they should go about doing this. This involves determining whether information is of significant public interest, appropriate, accurate, accessible and easy to use.

Without the structured assessment process of a PPS, agencies’ actions constitute publication, but not proactive release.

Figure 2A provides some examples of information published by agencies.

Figure

2A

Agency publication

Department of Treasury and Finance:

- reports, guidelines and research papers

- financial data sets

- details of overseas visits undertaken by staff

- major promotional, public relations and marketing activities

Department of Health:

- the Victorian Health Services Performance website provides timely information about the activity and performance of hospitals and health services across the state

Department of Education and Early Childhood Development:

- statistics of school education

- department structure and annual reports

- FOI policy and procedures and a selection of advice and information

Department of Business and Innovation:

- Tourism Victoria website

- Business Online

Department of Planning and Community Development:

- publications and research including newsletters, bulletins, fact sheets, brochures, practice and advisory notes, reports, policies, codes and guidelines

Source: Victorian Auditor General’s Office.

2.3.3 Comparison against better practice models

In other jurisdictions, agencies have shifted their focus away from reactively releasing information in response to individual FOI requests, to proactively publishing information within a robust framework.

The United Kingdom (UK) and Queensland governments have embraced proactive release. In 2000, the UK Government passed legislation that required all public sector agencies to maintain an information publication scheme. Agencies’ schemes are approved by the Information Commissioner and detail key organisational information, income and expenditure, decision-making structures, agency priorities and performance against objectives.

In 2008, the Queensland Government embarked on a major review of its FOI legislation. The case study in Figure 2B illustrates how Queensland has achieved better information disclosure outcomes by changing the culture and adopting a proactive release strategy.

Figure

2B

Proactive release in Queensland

In 2008 the Queensland Government appointed a panel to review its 1992 FOI legislation. The government accepted 139 of the 141 recommendations in the panel’s report, The Right to Information: Reviewing Queensland’s Freedom of Information Act.

The panel found that a key barrier to implementing FOI was the closed culture of the public sector. The report recommended the Queensland Government address this by changing its approach to FOI to routinely and proactively release government information instead of relying on the FOI process to inform the public.

Queensland’s shift in approach placed greater emphasis on the public’s right to information, rather than the right to request information. The change was reflected in the title of the new Act—the Right to Information Act 2009 (Qld). The Queensland Information Commissioner commented in 2011 that proactive release of information had reduced the number of adverse media reports on FOI practices in the state.

Other measures introduced in Queensland include:

- a publication scheme—Queensland’s approach is similar to the UK model

- disclosure logs—these allow the community to see what type of information is being requested. The same information may be of interest to a wider range of people than the FOI applicant. This approach encourages broader access to information

- summaries of Cabinet decisions—these are available on the Queensland Government’s website. Interested members of the public can search the register by date or topic.

Source: Victorian Auditor General’s Office.

The information Victorian agencies release is not as extensive or detailed as other jurisdictions. Victoria does not use disclosure logs or produce summaries of Cabinet decisions, while crime statistics in the UK and child protection statistics in Queensland are available at a more localised level than in Victoria.

The transparency of the VPS would be improved by adopting the better practices observed in other jurisdictions and pursuing a proactive release framework.

2.4 Reporting requirements

Reporting on the operation of FOI to Parliament and the community is important for a number of reasons. Reports demonstrate how agencies are complying with the legislation, identify any problems encountered in administering the Act, promote accountability and help embed good governance. Agencies can also compare their performance and share better practice among FOI policy makers and practitioners.

2.4.1 Department of Justice and non-compliance with reporting requirements

The minister responsible for the administration of the Act tables in Parliament an annual report on the operation of the Act. The minister relies on DOJ to produce the report. The Act specifies the items that should be included in the report. However, in 2009–10 and 2010–11, DOJ did not report to the minister on four of the specified items, including details of any difficulties encountered in the administration of the Act in relation to staffing and costs, and any efforts by the agency or ministers to administer and implement the spirit and intention of the Act.

DOJ advised it is taking a number of actions to improve the quality and timeliness of its responses to FOI requests, including earlier and more comprehensive engagement with senior management. However, it has not reported on these actions as the Act requires it to do.

DOJ has not led by example and, as a consequence, key information has not been reported to Parliament or the public. This limits the transparency of agencies’ performance in relation to FOI.

DOJ described this as a ‘longstanding administrative oversight’ and has advised that, subject to the approval of the minister, it will include all items in the 2011–12 report.

2.4.2 Additional information not reported

As outlined in the FOI Guidelines, agencies are required to report additional information to DOJ on a monthly basis. This information is not included in the annual report on FOI but is reported regularly to the State Coordination and Management Council. The principal officers of the 12 agencies examined in this audit are members of the council.

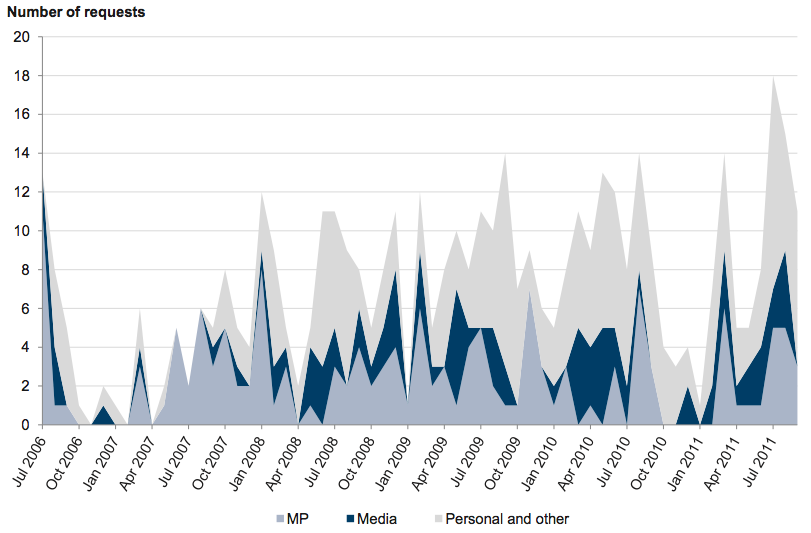

There are two items included in the State Coordination and Management Council FOI reports, but not the annual FOI report, that would greatly enhance public awareness of FOI performance across the VPS if released—agencies’ timeliness performance and the sources of FOI requests.

DOJ advised it does not release this information because the Act does not require it to do so. However, nothing in the legislation prevents DOJ from recommending to the minister that this additional information be included in the annual report. This information is clearly relevant to understanding the operation of FOI and is in the public interest. It should therefore be released.

DOJ has advised that, subject to the minister’s approval, it will include agencies’ timeliness performance and the sources of requests in the annual report. In addition, DOJ has advised that it will report on its own performance in its 2011–12 annual report.

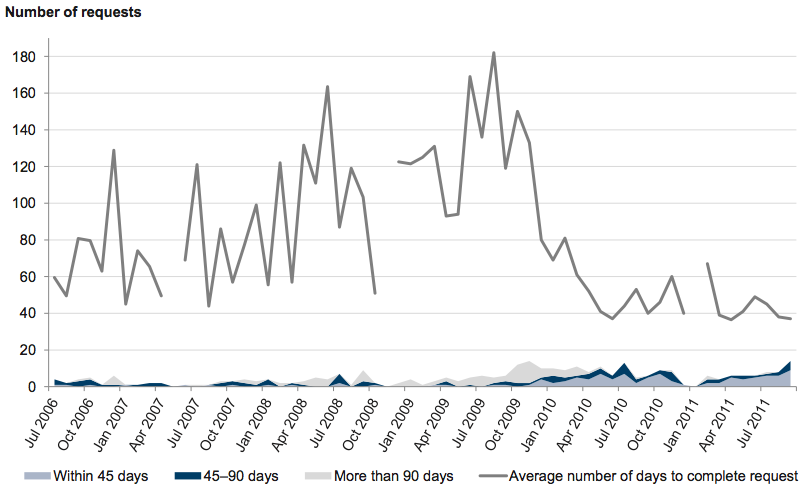

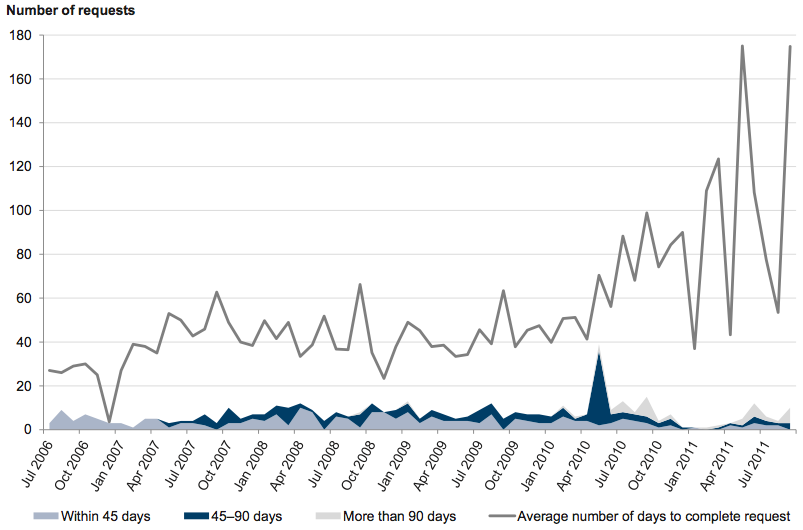

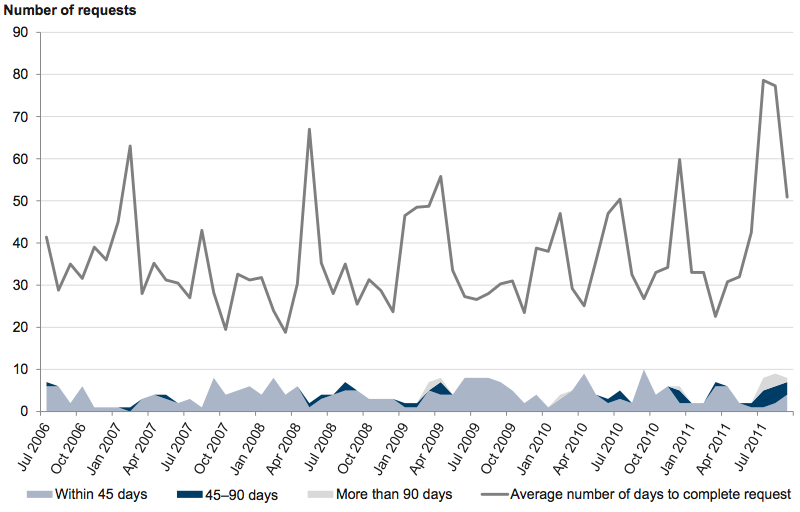

Timeliness

DOJ collects, but does not release, monthly data on agencies’ performance against the 45-day statutory time limit. Releasing this information would inform Parliament and the public, rather than just the principal officers, which agencies are meeting their statutory requirements.

Performance in this area was weak in two-thirds of the agencies reviewed. This information is in the public interest and its non-disclosure reduces the transparency of agencies’ performance. Timeliness data is discussed in more detail in Part 3 of this report.

Source of freedom of information requests

DOJ collects information about FOI applicants. Applicants are categorised as either media, Members of Parliament or ‘personal and other’, which is predominantly private citizens. The number of applications from each source varies significantly between agencies. Releasing this information would provide a clearer understanding of the type of requests each agency receives. Information on the source of FOI requests is provided in Appendix A.

2.4.3 Better practice reporting

There are many examples of better practice FOI reporting that DOJ can draw on to strengthen its reporting to Parliament. Some examples include:

- The Commonwealth FOI annual reports provide readers with a breakdown of timeliness performance of agencies.

- The New South Wales FOI annual reports categorise FOI requests by applicant type such as media, Members of Parliament, private sector businesses, not‑for‑profit organisations and members of the public.

- The UK produces a monitoring bulletin four times a year, containing key performance information.

- The Queensland FOI annual reports describe efforts made by agencies to further the object of the Right to Information Act 2009 (Qld).

These examples make agencies’ performance more transparent and relevant to the public, and help agencies share better practice.

2.4.4 Non-compliance with legislation

It is not enough for the public to have a right to access information. The public also needs to understand how to exercise that right. Part II of the Act describes the information agencies are required to disclose about their operations to help the public identify and request information they may not otherwise be aware exists.

Part II stipulates that agencies should set out information on their operations in a statement that includes:

- information on the functions of the agency

- categories of documents in the possession of the agency, and how to access these documents

- a list specifying the documents containing rules, policies, guidelines, practices or precedents

- information on Acts or schemes administered by the agency.

None of the 12 agencies included in the scope of this audit prepares a Part II statement.

The developments in information technology have rendered strict compliance with Part II unreasonably onerous for agencies. The Victorian Ombudsman’s 2006 report Review of the Freedom of Information Act recommended that Part II be revised in order to mandate publishing information that is relevant and useful without creating an unnecessary administrative burden. This recommendation was reflected in proposed legislative amendments in 2008, however, these amendments were not passed.

While the format of Part II may be dated, the concept remains current. DOJ has not reviewed the requirements of Part II to assess how the Act could better serve the needs of the public, nor provided guidelines to help agencies to meet their obligations.

DOJ advised that it will prepare guidance on how other agencies can best meet their requirements under Part II.

2.5 Freedom of information guidance

DOJ provides guidance for agencies and their FOI officers through two main mechanisms: a website and training. Responsibility for these activities may transfer to the new FOI Commissioner once appointed.

2.5.1 Website

DOJ maintains an FOI website to provide a range of information for FOI officers and members of the public. The website includes 13 Practice Notes, which provide guidance on topics such as requests for access, fees and charges, and dealing with ‘voluminous’ requests.

The Practice Notes are an accurate and useful quick reference tool for FOI officers on the administrative requirements of the Act. However, the complex nature of FOI means these Practice Notes can only supplement, rather than replace the need for formal training and robust procedures. For instance, although DOJ issued a Practice Note on timely decision-making, it did not address the issue of delay. Further action is required from DOJ to improve agencies’ lack of timely responses to requests.

2.5.2 Training

Training is an important opportunity to instil a positive FOI culture in agencies and to emphasise the importance of openness and transparency. DOJ has not capitalised on this opportunity.

To maximise its effectiveness, FOI training should cover both the letter and intent of the Act and be appropriately tailored to trainees’ requirements. DOJ’s current one-day training session focuses on the basic administration of the FOI process, not the spirit or outcomes sought by the legislation. There would be merit in revising the content of the basic course and holding intermediate and advanced sessions that have been tailored for more experienced FOI officers.

DOJ advised that, in light of the audit findings, it would strengthen its training seminars to reinforce the spirit and intent of the Act. This is an encouraging sign.

Agencies supplement the existing training with information relevant to their organisation. This is covered in more detail in Part 3.

2.6 Department of Justice performance

DOJ considers its leadership role is fulfilled through the provision of support and guidance to other agencies. The department acknowledges that it could have been stronger in its coordination role and its own performance, but considers that it cannot address substandard practices because it does not have sufficient powers to do so. DOJ’s position is that the principal officers of each agency are accountable for regulating good practice and enforcing compliance. While principal officers are indeed accountable for their agencies’ performance, DOJ could have sought to extend its powers. It did not do so.

As the lead agency for FOI, it would be reasonable to expect DOJ would set a strong example in its own FOI performance for other agencies to follow. DOJ has acknowledged that this is not the case.

DOJ’s practices were deficient in all of the three case studies reviewed:

- Two requests were inappropriately narrowed, which resulted in costs being under-reported.

- In the third case, DOJ did not apply the appropriate section of the Act when consulting with the applicant on the scope and size of their request. This resulted in extra time being allowed to complete the request without being reported.

Although not numerically significant, it is concerning that there were issues with all of the cases reviewed. DOJ received 546 FOI requests in 2010–11.

Recommendations

-

The Department of Justice should provide stronger leadership in

acquitting its statutory obligations to Parliament by:

- reviewing the Freedom of Information Act 1982 to improve its currency and to champion the proactive release of information

- overhauling the content and frequency of current reporting requirements

- providing detailed guidance on proactive disclosure for agencies

- providing more comprehensive and tailored training.

-

Principal officers of agencies should diligently discharge their responsibilities under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 by:

- improving the transparency of their processes

- maximising the information made available to the public through a proactive release framework.

3. Agencies' management of freedom of information

At a glance

Background

The Attorney-General’s Guidelines on the Responsibilities and Obligations of Principal Officers and Agencies (the FOI Guidelines) require principal officers—secretaries and chief operating officers of agencies—to provide adequate resources and support to deliver timely and accurate freedom of information (FOI) responses.

Conclusion

Agencies that routinely disregard the 45-day statutory time limit for processing requests and the five day ministerial noting period reflect a culture of apathy that has developed towards the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (the Act). Principal officers of these agencies are not being held to account for their agency’s poor FOI management practices.

Findings

- Only four out of 12 agencies’ average response times complied with the 45-day time limit in 2010–11.

- Three of the 12 agencies routinely accept long delays in ministerial noting, with average noting periods of between 20 and 41days instead of five.

Recommendations

Principal officers should:

- promote the appropriate ‘tone at the top’ with regard to the object of the Act

- monitor their performance against the requirements of the Act, the FOI Guidelines and related policies and procedures, identify areas of underperformance or non‑compliance and remedy any shortcomings

- review the support and guidance they provide to confirm their agency is meeting its obligations under the Act.

Agencies should:

- improve their processes to comply with the 45-day statutory time limit

- routinely release information on day six of the ministerial noting period.

The Department of Justice should drive continuous improvement by, in the longer term, giving consideration to adjusting the statutory time frame.

3.1 Introduction

The Attorney-General’s 2009 Guidelines on the Responsibilities and Obligations of Principal Officers and Agencies (the FOI Guidelines) state that the timeliness of responses to freedom of information (FOI) requests is fundamental to the purpose of FOI and that delays in processing requests undermine its usefulness.

The FOI Guidelines also state that principal officers—secretaries and chief operating officers of agencies—should provide an appropriate level of resources, support and guidance to provide timely responses that meet their statutory obligations.

The Freedom of Information Act 1982 (the Act) allows agencies 45 calendar days to respond to applicants’ requests for information. The FOI Guidelines recommend agencies allow five business days from within the legislated 45-day response period to inform their ministers of decisions on FOI requests.

This Part examines the timeliness performance of all 12 audited agencies, their ministerial noting practices and the support provided to meet FOI requirements.

3.2 Conclusion

Timeliness of response is an important indicator of FOI performance and culture. In 2010–11, eight of the 12 agencies reviewed had an average response time that exceeded the 45-day statutory limit.

The Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC), the Department of Human Services (DHS) and Victoria Police were substantially above the 45-day limit. Victoria Police and DHS did not comply with the 45-day time limit in every financial year from 2006–07 to 2010–11. This indicates the presence of significant systemic problems within these agencies.

Although the Department of Justice (DOJ) is the lead agency for FOI, principal officers are responsible for managing their own agency’s obligations under the Act. They are also responsible for promoting the importance of FOI. However, the prevailing Victorian public service culture of apathy and resistance to scrutiny means that principal officers have not adequately addressed their agency’s non-compliance with FOI legislation.

Poor performance in relation to timeliness indicates the low regard for both the purpose of the Act and agencies’ legislative obligations under it. The slow response times contravene the Act and are contrary to the principals of the Code of Conduct for Victorian Public Sector Employees, which expects public officials to deliver high quality services to the community. Principal officers are not being held to account for their agency’s non-compliance with the Act.

The Act requires FOI officers to independently perform a statutory decision-making function. Lengthy ministerial noting periods, particularly at DPC, DHS and the Department of Health (DOH) increase the perception of political interference in the FOI process.

Principal officers do not adequately support their FOI officers’ independence because they have not sent the clear message that it is unacceptable to frustrate the FOI process, or to seek to unduly influence an FOI officer in the execution of their duties under the Act. Principal officers should, but do not, insist that FOI documents be released on day six of the noting period.

Principal officers are in a unique and powerful position to influence the attitudes and approaches of their staff by sending clear messages about what is expected in regard to FOI. They are not doing this.

3.3 Timeliness performance

Agencies’ response times can vary according to the nature of the request and the availability of resources. Due to the statutory requirement to process FOI requests within 45 days, timeliness performance is a good indicator of the priority senior management place on FOI.

The length of time taken to process an FOI request can have a significant impact on applicants and the value of the information being sought. Timeliness is particularly important for:

- former wards of the state trying to establish their identity and reconnect with family members

- people making a decision about whether to go to court

- Opposition Members of Parliament preparing for informed debate in Parliament

- journalists reporting on matters of current public interest.

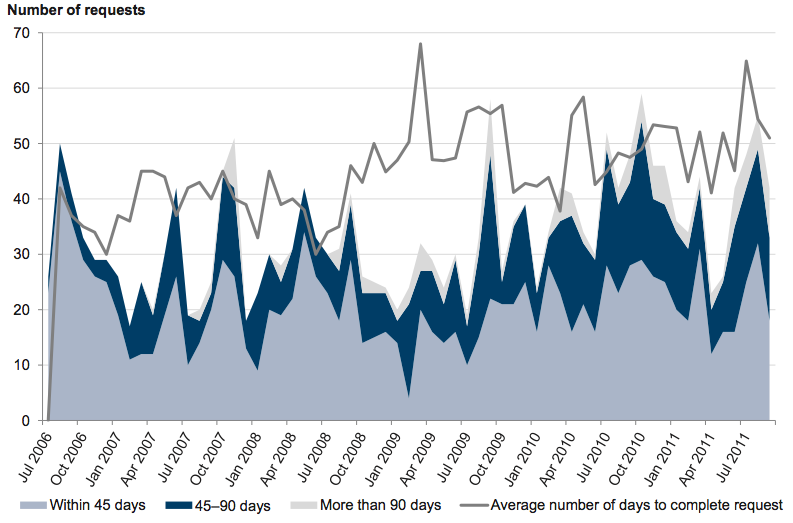

3.3.1 Comparison of agencies’ performance

Principal officers receive regular reports from DOJ on agencies’ timeliness performance, such as agencies’ average response time and the percentage of requests fulfilled within 45 days. However, this important information is not currently reported to Parliament and the public.

Average response time

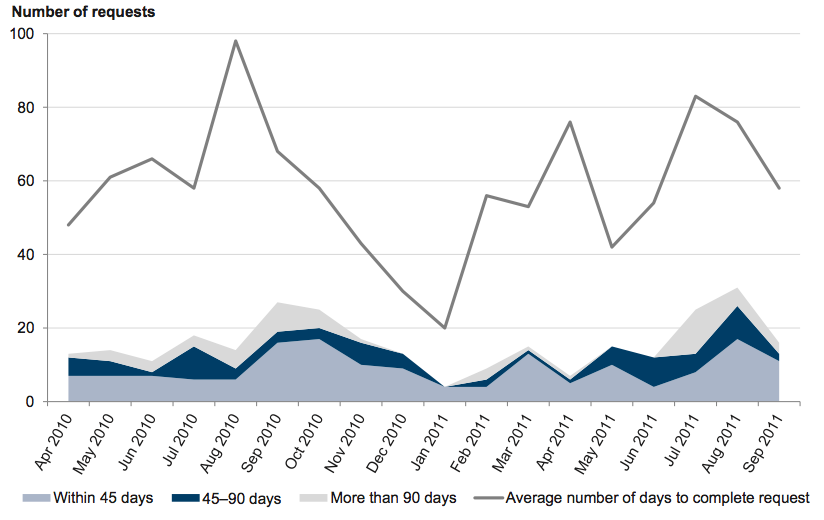

Of the 12 agencies reviewed during the audit, only the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD), the Department of Transport (DOT), the Department of Primary Industries (DPI) and the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) had average response times in 2010–11 that met the 45-day time limit.

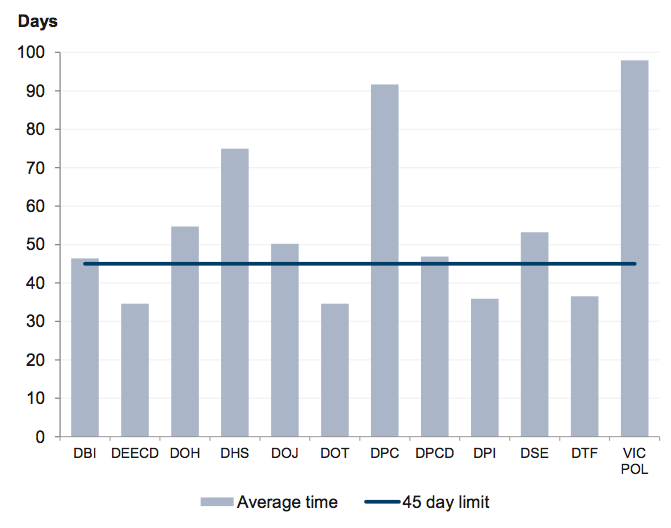

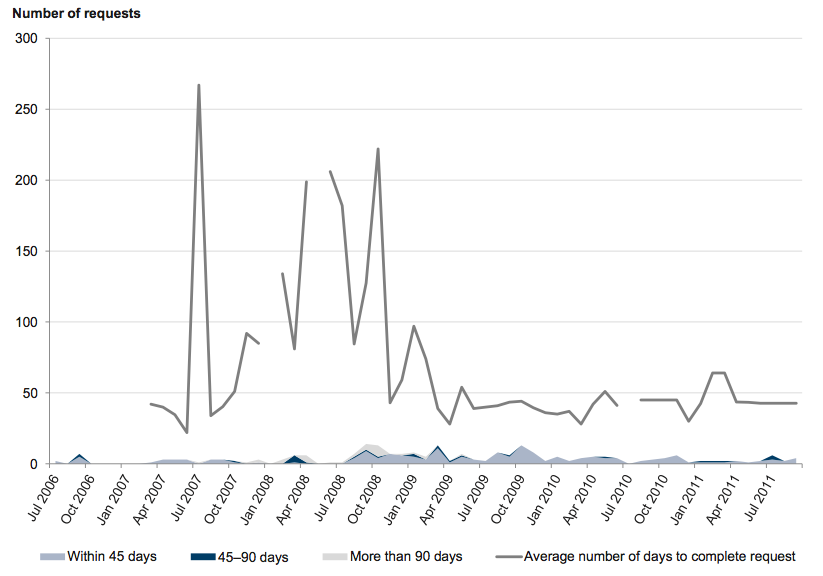

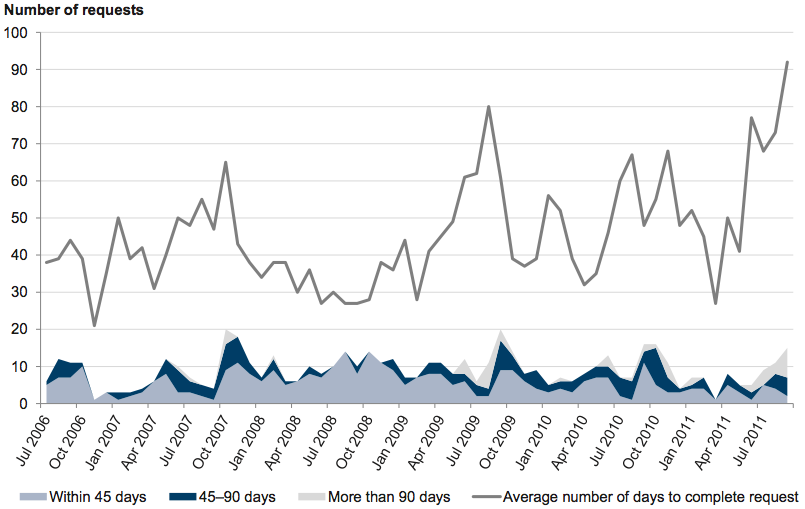

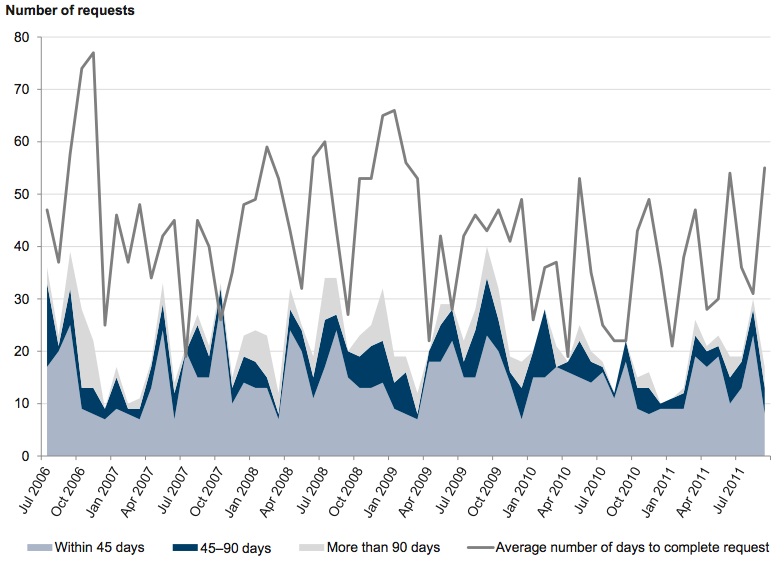

The worst performers were Victoria Police (98 days), DPC (92 days) and DHS (75 days), as Figure 3A shows.

Figure

3A

Average time to complete FOI requests by agency 2010–11

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Figure 3B shows where agencies have met the statutory time limit (Y) and where they have not (N). It reveals that:

- DEECD and DPI have been the strongest performing agencies over the past five years

- Victoria Police and DHS have been among the worst performing agencies

- DOJ, despite being the lead agency for FOI, has an average response time that exceeded the 45-day limit in each of the past three financial years.

Figure

3B

Agencies’ adherence to the 45-day limit

Agency |

2006–07 |

2007–08 |

2008–09 |

2009–10 |

2010–11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Department of Business and Innovation |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

Department of Education and Early Childhood Development |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Department of Health |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Department of Human Services |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Department of Justice |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

Department of Planning and Community Development |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Department of Premier and Cabinet |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

Department of Primary Industries |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Department of Sustainability and Environment |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

Department of Transport |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Department of Treasury and Finance |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Victoria Police |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

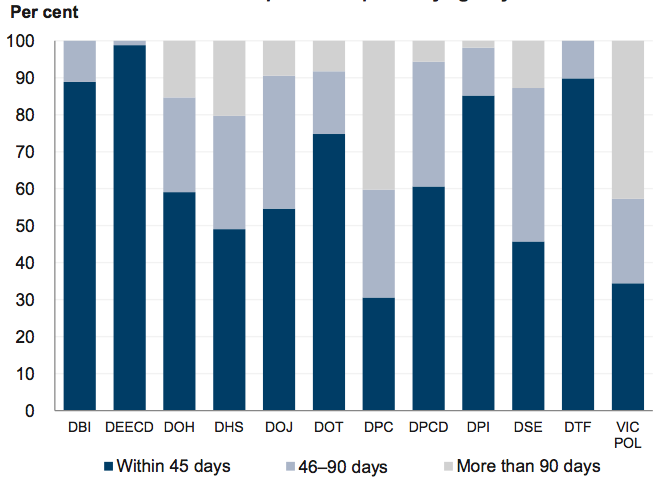

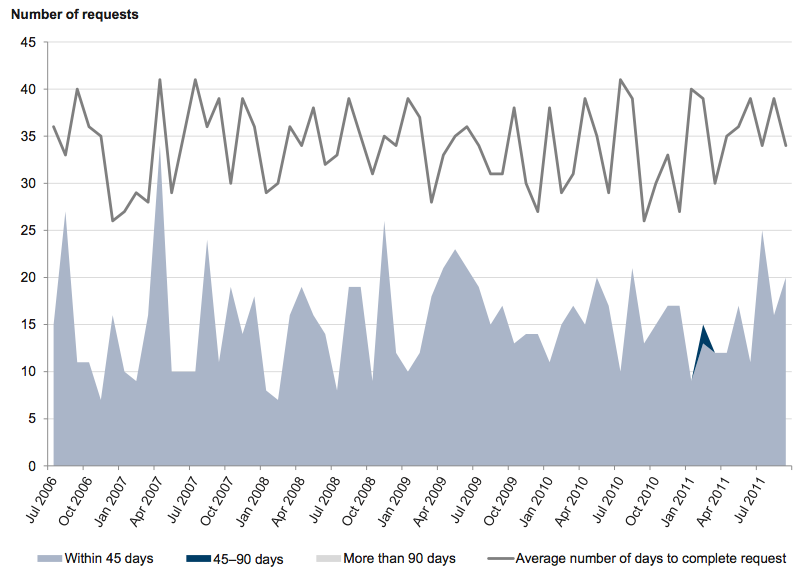

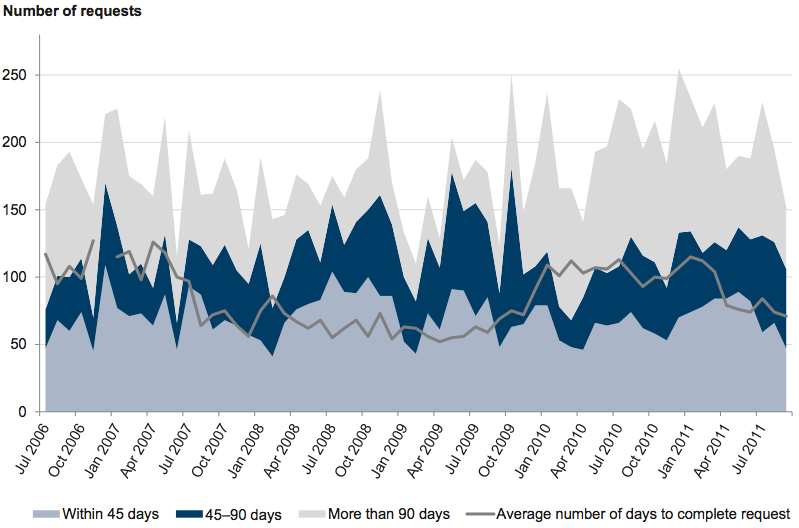

Requests fulfilled within 45 days

It is also important to consider the percentage of requests processed within the 45-day time limit when assessing the consistency of performance. In 2010–11:

- the strongest performers were DEECD, DTF and the Department of Business and Innovation (DBI)—these agencies respectively processed 99 percent, 90 percent and 89 percent of their requests within 45 days

- the worst performers were DPC and Victoria Police—these agencies respectively processed 31 per cent and 34 per cent of their requests within 45 days.

Agencies’ performance is outlined in Figure 3C.

Figure

3C

Timeliness of FOI requests completed by agency 2010–11

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

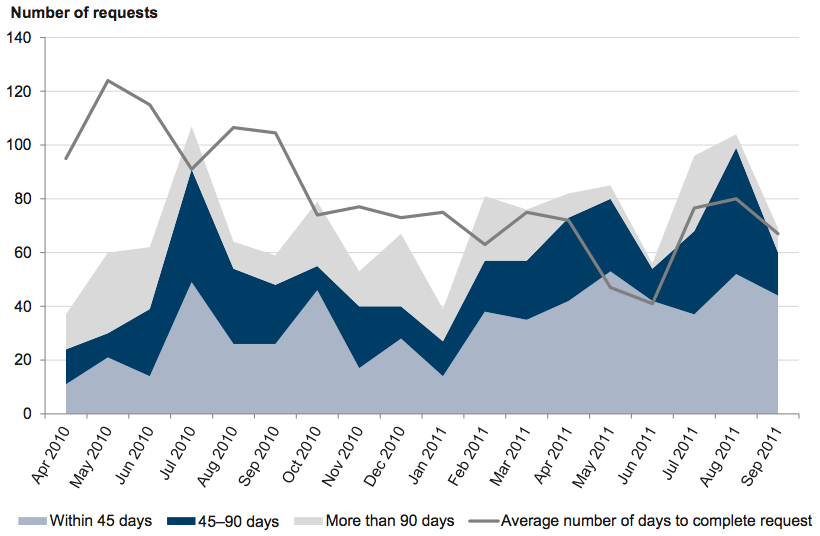

Further analysis of agencies’ performance with regard to timeliness and other benchmarks can be found in Appendix A.

3.3.2 Better practice comparison

Timeliness is clearly an issue for Victorian agencies. However, Victoria’s underperformance against its own legislation is even more concerning when compared with the performance of other states.

New South Wales, the Commonwealth, South Australia, Queensland and Tasmania all have shorter standard statutory processing time frames than the 45 calendar days permitted in Victoria. Extensions may be granted in certain circumstances.

New South Wales’ processing time is 20 business days with an extension of up to 15 days in some circumstances. Its level of compliance in 2010–11 was significantly better than the equivalent agencies in Victoria:

- The New South Wales Police Force complied with the permitted time limit in 97 per cent of cases in 2010–11, despite handling approximately three times more requests than Victoria Police.

- The New South Wales Department of Family and Community Services complied in 93 per cent of cases in 2010–11, while handling half the number of requests of DHS in Victoria.

- The New South Wales Department of Premier and Cabinet complied in 81 percent of cases.

3.3.3 Causes of delays

The time agencies take to respond to applicants can vary according to the nature of requests and the resources available to manage them. These factors can create variability in performance standards and make it more difficult for management to monitor that performance.

It is nonetheless incumbent on agencies to understand the causes of delays and to take appropriate remedial action. With the exception of DHS and DOH’s shared FOI unit and—prompted in October 2011 by this audit—the Department of Planning and Community Development (DPCD), the audited agencies do not monitor the time taken to complete each stage of the FOI process. Without analysing the time taken to complete each step, it is difficult for agencies to identify and remedy the main causes of the delays.

3.4 Ministerial noting

The FOI Guidelines require FOI officers to brief ministers on sensitive requests. However, the FOI Guidelines also state that responsibility for FOI decisions rests with the FOI officer making the decision.

Although it is appropriate for agencies to keep ministers informed of matters relevant to their portfolio, this practice increases the risk of actual, or perceived, political influence on the FOI officer’s decision. It therefore warrants agencies’ close attention and proactive management.

3.4.1 Adherence to noting period time lines

According to the FOI Guidelines, the ministerial noting period should be five business days. The purpose of this time limit is to reduce the risk of information being deliberately delayed to minimise its political impact, for example, withholding information until after an election or until a topic is no longer of public interest.

Of the 12 audited agencies, on average, only DEECD, DPCD, DPI and Victoria Police adhered to the FOI Guidelines. The worst performers were DOH (20 days), DHS (25 days) and DPC (41 days). Long delays in noting may create the perception that there are attempts to exert political influence on the FOI process.

Even those agencies that are meeting the 45-day statutory time limit to respond to requests should demonstrate responsiveness to the community by adhering to the five day ministerial noting period. It is not acceptable practice for agencies to disregard the FOI Guidelines. The FOI officer has already made a decision on the request when the response is forwarded to the minister for noting. Extending the noting period is therefore inappropriately prolonging the length of time taken to respond to the public. The Act requires applicants to be informed of decisions ‘as soon as practicable’, even if this is before the 45 days have elapsed.

Principal officers need to develop appropriate strategies to mitigate the perception of improper influence on the FOI process by reinforcing the independent role of their FOI unit and routinely releasing documents on day six.

3.4.2 Ministerial noting at the Department of Premier and Cabinet

DPC’s Legal Branch advised the secretary on 31 August 2011 of delays in noting by the Office of the Premier. Attached to the briefing was a log containing details of the department’s current FOI requests. Of the 36 active FOI requests on this log, 13 were with the Office of the Premier for noting. DPC’s briefing stated that the Office of the Premier was taking significantly longer than the five day noting period, which was contributing to processing delays.

Although it is correct that the noting period was being exceeded, analysis of the log attached to the briefing revealed that DPC had contributed to the greater part of the delays, as shown in Figure 3D.

Figure

3D

Log of requests with the Office of the Premier on 31 August 2011,

showing elapsed time

Number of days |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Type of request |