Guardianship and Decision-making for Vulnerable Adults

Audit snapshot

What we examined

We assessed if the Office of the Public Advocate (the office) provides guardianship and investigation services that promote and protect the rights and interests of vulnerable adults.

We examined the office and the Department of Justice and Community Safety (the department).

Why this is important

Sometimes disability reduces a person's capacity to make decisions for themselves, even with support. In these cases, a guardian may be legally appointed to make decisions for the person.

The office acts as a guardian of ‘last resort’ when there is no other suitable person who can do this.

Guardians often make difficult decisions for some of the most vulnerable people in our community. These decisions can have a significant impact on these people, such as where they live, what services they can access and their healthcare.

It is important that the office protects and promotes these individuals' rights, interests and dignity in its guardianship and investigation services.

What we concluded

The office provides crucial guardianship and investigation services for thousands of vulnerable adults each year in complex and challenging circumstances. But it could do more to protect and promote their interests.

The office can improve:

- how long it takes to appoint guardians to people

- when and how well it engages with its clients

- its record keeping.

The office can do more to understand the resources it needs to deliver its guardianship and investigation services.

It can also improve how it monitors performance to make sure staff protect and promote people's rights and interests in all cases.

What we recommended

We made 10 recommendations to the office about improving:

- its documentation

- how it engages with clients

- its training and guidance for staff

- how it collects and uses data

- its planning and oversight.

We also made 3 recommendations to both the department and the office about improving their:

- planning and recruitment processes

- performance measures.

Easy English version of the report snapshot

The Easy English version of the report snapshot is intended to meet the needs of some people who have difficulty reading and understanding written information.

The Easy English document is not the final audit report that has been prepared and tabled in the Victorian Parliament under the provisions of the Audit Act 1994. It should not be relied on or quoted from as the final audit report.

Video presentation

Key facts

Source: VAGO, based on the Office of the Public Advocate's data.

Our recommendations

We made 13 recommendations to address 3 key issues. The relevant agencies have accepted our recommendations in full or in principle.

| Key issues and corresponding recommendations | Agency responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Issue: The Office of the Public Advocate has not met its target timeframes to deliver guardianship and investigation services and has gaps in its record keeping | ||||

| Office of the Public Advocate | 1 | Within 14 days of receiving an order, give clients on the waitlist information about guardianship and investigations, including:

| Accepted | |

| 2 | Require investigators to consult with proposed represented people during investigations as far as practicable (see Section 1). | Accepted | ||

| 3 | Review and update its guidance to staff, including guidance about allocating orders and balancing the risk of harm when making decisions (see Section 1). | Accepted | ||

| 4 | Improve its training program by:

| Accepted | ||

| 5 | Develop internal reporting on:

| Accepted | ||

| 6 | Implement a risk-based quality assurance process to review a sample of guardianship, investigation and complaint files at least every 12 months (see Section 1). | Accepted | ||

| Issue: There are gaps in how the Office of the Public Advocate plans, uses and oversees its resources | ||||

| Department of Justice and Community Safety and the Office of the Public Advocate | 7 | Revise their recruitment process to give the Office of the Public Advocate greater independence in its process and decisions (see Section 2). | Accepted | |

| 8 | Work together to:

| Accepted in principle | ||

| 9 | Seek amendments to the Office of the Public Advocate's performance measures in Budget Paper 3: Service Delivery to ensure it has a meaningful mix of quantity, quality and timeliness measures that provide appropriate service coverage, subject to available data (see Section 2). | Accepted in principle by the Department of Justice and Community Safety Accepted by the Office of the Public Advocate | ||

| Office of the Public Advocate | 10 | Determine the ideal caseload for guardians and investigators to operate effectively, considering case complexity and staff experience (see Section 2). | Accepted | |

| 11 | Ensure it assesses all guardianship orders against its complexity tool before allocating cases to staff (see Section 2). | Accepted | ||

| 12 | Consider the skills, size, shape and source of its future workforce to design and implement a workforce model that:

| Accepted in principle | ||

| 13 | Implement changes to its client management system to improve the quality of data it collects and reports, and ensure this data is accurate, complete, timely, consistent and collected appropriately (see Section 2). | Accepted in principle | ||

What we found

This section summarises our key findings. Sections 1 and 2 detail our complete findings, including supporting evidence.

When reaching our conclusions, we consulted with the audited agencies and considered their views. The agencies’ full responses are in Appendix A.

What is guardianship?

Guardianship aims to protect and promote the rights and interests of people with disability that reduces their capacity to make decisions for themselves.

The Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) can appoint a guardian (either an individual or the Public Advocate) to make specific decisions on a person's behalf if they determine that:

- the person does not have decision-making capacity due to disability

- there is a need to make a decision

- having a guardian will promote the proposed represented person's personal and social wellbeing.

VCAT can appoint a guardian to make decisions for a person, such as:

- where they live

- what services they can access and who can provide them

- their healthcare

- who can have contact with them.

VCAT may also ask the Public Advocate to investigate if someone needs a:

- guardian if it is unclear about the person’s disability, there is significant family conflict or there are substantial risks

- financial administrator.

Once the Public Advocate gets an order from VCAT, they can delegate their legal decision-making authority to a staff member at the Office of the Public Advocate (the office).

The office is a business unit of the Department of Justice and Community Safety (the department).

Decision-making capacity

VCAT can appoint a guardian to a person if disability, such as neurological or intellectual impairment, dementia, mental disorder, physical disability or brain injury, reduces their capacity such that they are unable to make decisions, even with support. A person's decision-making capacity can change over time and they may have capacity to make decisions about some matters but not others.

Why we did this audit

The office represents some of the most vulnerable people in our community in challenging and complex circumstances.

However, the office has only met its public performance measure in Budget Paper No. 3: Service Delivery (BP3) to allocate guardianship and investigation matters within its target timeframe once since 2018.

When planning this audit, we heard that several factors impacted the office's service delivery over this period, including:

- indirect effects of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), such as increased complexity and length of guardianship orders

- a cap on guardian caseloads by WorkSafe Victoria following reports of excessive workload at the office.

In 2020, the office also transitioned to a new legislative framework to put a represented person's will and preferences at the forefront of how a guardian makes decisions for them.

Our audit looks at an area where people may not be able to effectively raise issues themselves. It is also an opportunity for Parliament and the public to understand if the office is meeting the needs of these vulnerable people.

Will and preferences

The Guardianship and Administration Act 2019 (the Act) requires guardians to 'give effect to a person's will and preferences as far as practicable'.

The office's guidance to guardians says that in the simplest terms, a person's will and preferences are what is important to them.

A person's will and preferences can change over time. If a guardian cannot find out what they are or are likely to be, they must act in a manner that promotes the represented person's personal and social wellbeing.

Represented person

A represented person is a person under a guardianship order. When the office is investigating if a person has decision-making capacity it refers to them as a proposed represented person. We use the term 'client' to refer to both proposed represented people and represented people in this report.

Our key findings

Our findings fall into 3 key areas:

| 1 | The office has not met its target timeframes to deliver guardianship and investigation services. |

| 2 | Gaps in the office's record keeping limit its ability to oversee and report on its service delivery. |

| 3 | There are gaps in how the office plans, uses and oversees its resources. |

Key finding 1: The office has not met its target timeframes to deliver guardianship and investigation services

Why timeliness is important

Guardians make decisions that are often significant and time sensitive, such as where a person will live or who can visit them.

Sometimes factors outside of the office's control, such as availability of aged care or rental accommodation, delay these decisions. But the office can control how quickly it allocates orders and when it engages with clients.

Strong and timely engagement helps the office:

- find out a person's will and preferences, which the Act requires

- be responsive to a person's changing circumstances and needs

- strengthen public trust in it, which helps it deliver its mandate to promote the rights of Victorians with disability.

We found that the office has not met its internal and external timeliness targets and can improve how it engages with its clients.

Timeliness targets

Since 2018 the office has not met its BP3 target timeframe to allocate guardianship and investigation orders, except in 2020–21.

We analysed selected case files and the office's data from 2018 to 2023 and found it also did not meet other target timeframes at key points throughout its investigation and guardianship processes.

| The office should … | We found ... |

|---|---|

| conduct urgent investigations in a timely manner | from 2018 to 2023 it completed 90% of urgent investigations within 3 days, which is a positive result. |

| allocate orders within 15–19 days | it took an average of 44.5 days for the office to allocate orders in 2022–23. |

| contact a represented person within 10 days of allocating their case to a guardian | it did this in 50% of cases we reviewed. |

| physically meet with a represented person within 28 days of allocating their case to a guardian* | it did this in 37% of cases we reviewed. |

| physically meet with a represented person at least once per year if their order lasts longer than one year* | it did this in 13% of cases we reviewed. |

| make decisions in a timely manner** | it did this in 69% of cases we reviewed. |

conduct non-urgent investigations within the following timeframes:

| it met these timeframes in 35% of cases we reviewed. Data also shows that its median time to complete a low, medium and high-risk investigation exceeded its timeframes from 2018 to 2023. |

resolve complaints within the following timeframes:

| it did this in 72% of cases we reviewed. |

Note: The office's target to allocate orders is from the BP3. The other targets in this table are from the office's internal policies and the National Standards of Public Guardianship.

*If a represented person's disability or circumstances or external factors, such as COVID-19 restrictions, do not allow face to-face contact, the office uses technology such as video calls to meet with these people. We included video calls as evidence of physical meetings in these cases.

**We assessed the timeliness of each decision by considering the office's assessment of the relative risk to the represented person, the represented person's needs and the options available to the represented person. The result includes cases where all decisions were made in a timely manner, or decisions were partly made in a timely manner. For example, if the guardian made timely decisions about a person's access to services, but not their accommodation.

Engaging with clients

The office deals with complex issues that can change over time. So it is important for it to build strong relationships with clients and communicate with them on an ongoing basis.

The office sets minimum standards for how guardians should engage with represented people. These standards include when and how often guardians should meet with them.

However, in many of the case files we reviewed, the guardian did not engage with the represented person in line with the office's timeframes.

Data we analysed also showed that 25 per cent of represented people waited more than 6 months for a guardian to physically visit them between 2018 and 2023.

We found issues with how guardians record their interactions with represented people and use the office's client management system (CMS), which reduces the reliability of this data.

For example, one guardian recorded their meeting with a represented person as 'Establishing Contact', while another recorded the same type of meeting as 'Represented Person Contact'. This makes it difficult for the office to oversee if all guardians engage or meet with clients in line with the office's requirements.

Impact of timeliness on clients

When the office does not meet its timeframes for allocating an order and contacting a represented person, this person may not:

- have the opportunity to meaningfully engage with the office for extended periods of time

- feel that they have had their voice heard.

This may reduce the office's ability to make decisions that reflect the represented person's current will and preferences.

The office's intake team can make decisions for people on its waitlist. But delays in allocating orders and contact with a client increase the risk that the person will not have timely access to services that require complex decisions, such as permanent or complex accommodation decisions. The office does monitor all cases on its waitlist, and can prioritise allocating orders to staff if a person's circumstances change and they require an urgent, complex decision.

Key finding 2: Gaps in the office's record keeping limit its ability to oversee and report on its service delivery

Gaps in record keeping

The office's staff need to record details about decisions they make. This allows the office to:

- check staff are meeting their obligations under the Act, the Victorian Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (the Charter), the National Standards of Public Guardianship (the Standards) and the office's policies

- efficiently find the information it needs to handle or review an order.

But we found issues with how staff recorded information in the office's CMS, which limit the office's ability to do this.

The Standards

The Standards outline best-practice principles for public guardians across Australia. They were last updated in 2016 by the Australian Guardianship and Administration Council, which is made up of public guardian and administrator offices across Australia, including the office.

Documentation

The office's internal policies and the Standards require guardians to document the following information when they make key decisions about a represented person's life:

- information about the decision, including the person's will and preferences and risks to the person

- the guardian's consideration of the person's human rights.

However, we found gaps in the office's record keeping. These gaps were worsened by staff inconsistently recording data in the CMS. For example:

- staff recorded the same type of information about contacting clients differently

- staff did not always record important information about a case, such as a risk rating

- the CMS did not have validation rules, which means the office may not promptly identify and address data entry errors.

Key finding 3: There are gaps in how the office plans, uses and oversees its resources

Organisation context

Because the office is a business unit of the department, the department employs the office's staff and provides central services, such as recruitment and funding.

The office also gets funding from other departments for specific projects.

Planning and oversight

We found opportunities for the office to improve:

- its organisational planning

- how it prioritises and allocates orders

- its performance measures to oversee its performance.

Organisational planning

Organisational planning helps an organisation achieve its business goals and find opportunities to increase its efficiency.

To do this properly, an organisation needs to understand its staff's skills and capabilities, the time, cost and amount of work it takes to deliver its services, and the future demand for its services.

But we found gaps in the office's understanding of:

- the skills and capability of its current workforce

- the time, cost and amount of work it takes to deliver its services

- the complexity of its services

- future demand for its services.

This means the office does not have enough information to adequately identify the resources it needs to deliver its services now and in the future.

Over the last 5 years the office has relied on lapsing funding to deliver core guardianship and investigation services. This is funding for a set period of time. In 2022–23, 36.4 per cent of the office's funding for these services was lapsing funding.

The office told us that this:

- limits its ability to plan for the future

- has contributed to staff turnover because it relies on fixed-term contracts.

But the office should still plan and manage its resources within its existing resource constraints.

Prioritising and allocating orders

To use its resources effectively, it is important that the office:

- allocates and actions orders in a timely way

- prioritises high-risk orders

- makes sure staff have the skills, experience and capacity to action an order.

| But we found that … | Which means that … |

|---|---|

Between 2018–19 and 2022–23 the office did not rate the risk level of:

| it might not be able to identify and immediately action all high-risk cases. |

| Certain teams in the guardianship program have larger waitlists than other teams | some orders may be on the waitlist while staff in other teams have capacity to take new orders. |

|

|

| The office does not know the optimal caseload for staff to operate efficiently and effectively | some staff may have too many cases and/or too many complex cases to manage them effectively. |

These factors may contribute to the issues we found with the office's timeliness and engagement with clients.

These factors may also contribute to workload issues.

For example, in the 2022–23 People Matter Survey, 82 per cent of the office's staff who completed the survey reported work-related stress. Of these staff, 62 per cent of staff reported stress from their workload.

Overseeing service delivery

The office uses the following 2 BP3 performance measures to oversee its guardianship and investigation services:

- the number of new guardianship and investigation orders actioned by the office

- the average number of days a guardianship or investigation order is on a waitlist before the office allocates it to a staff member.

However, these measures do not give Parliament and the public a complete understanding of the office’s performance because they do not assess how:

- effective its services are

- efficient its services are.

The measures are also not completely attributable to the office's performance because they are affected by the number of orders VCAT makes.

This means the office does not have a meaningful mix of performance measures that provide good service coverage.

1. Making decisions for vulnerable adults

Strong and timely engagement is essential to ensure the Office of the Public Advocate makes good decisions that enact a person's will and preferences where practicable and promote their human rights.

But we found the office has not met its target timeframe to allocate cases. And there are gaps in its timeliness and engagement with its clients. These issues mean the office cannot be sure that it is always delivering its mandate and meeting the needs of vulnerable adults.

Background information

The guardianship system in Victoria

Under the Act, guardians have a role in making decisions for represented people and advocating for their rights and interests in different situations. Guardians often do this in challenging circumstances.

Peoples' lives are complex. Some represented people have a history of trauma, family conflict and insecure housing and services.

The office may need to interact with multiple systems, such as the NDIS, aged care providers, hospitals, accommodation providers and support services, and liaise with family and caregivers.

In the recent Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability, Public Advocates and Public Guardians across Australia also noted that the NDIS has increased the complexity and number of guardianship orders since its introduction.

Of the office's 977 new guardianship matters in 2022–23, 574 (59 per cent) were NDIS participants. The office advised that its NDIS client cases often require more decisions and work, such as managing clients' service deeds.

Additionally, the Public Advocate has publicly reported that over the last 5 years, represented persons who are also NDIS participants spend around double the length of time under public guardianship than clients who are not NDIS participants.

These factors contribute to the complexity of the external environment the office operates within.

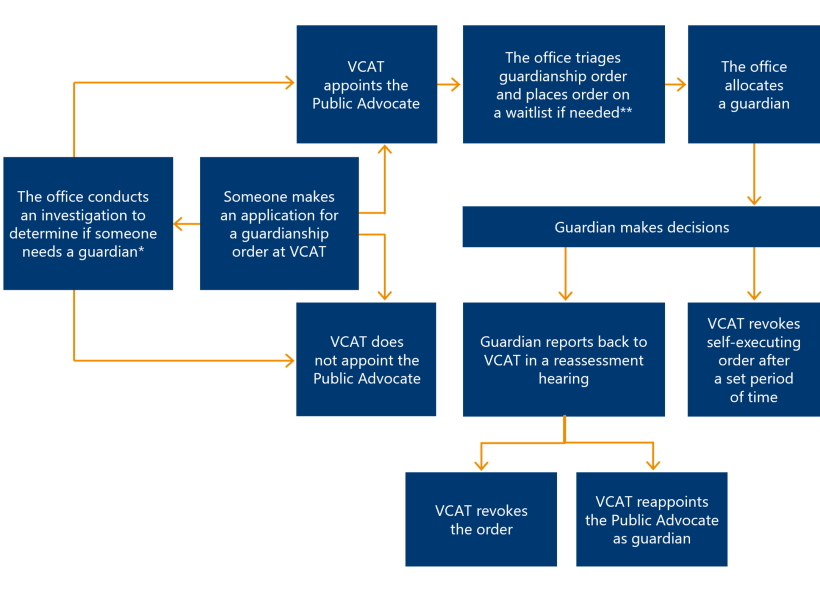

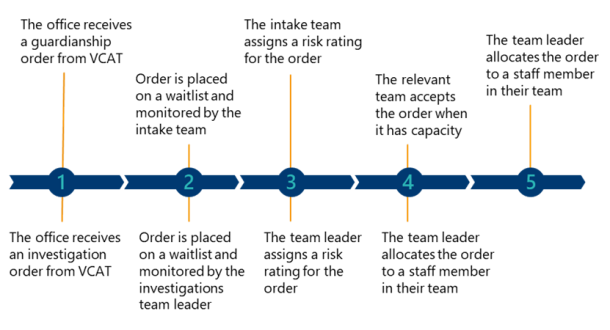

Guardianship and investigations process

Figure 1 shows the office's process to manage guardianship orders and investigations.

Figure 1: The office's standard process to manage guardianship orders and investigations

Note: *The Public Advocate can decide to do an investigation if they determine this is warranted. VCAT can also refer matters for the Public Advocate to investigate. VCAT may refer a matter for investigation if it is unclear about the person’s disability or the use of powers of attorneys by financial and personal attorneys, if there is significant family conflict or there are substantial risks. It can also ask the office to investigate whether a person needs an administrator or about special medical procedures.

**The office's intake team makes some decisions for people on its waitlist. It also manages communication and correspondence for the case until allocation.

Source: VAGO, based on information from the office.

Data on guardianship and investigations

Guardianship orders may last months or even many years.

While some guardianship orders are self-revoking (they end after a specified period of time), the office often needs to apply to VCAT to have an order revoked (closed) when it no longer applies.

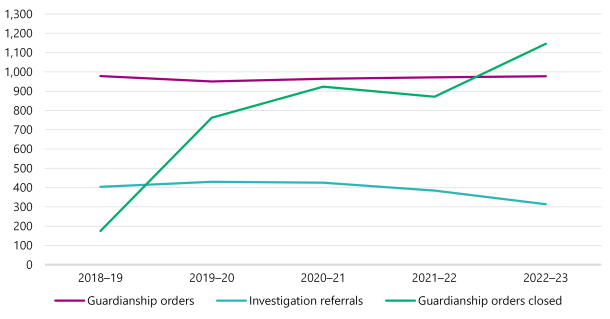

As Figure 2 shows, the number of guardianship orders and investigations has remained relatively stable between 2018 and 2023.

Figure 2: Number of guardianship orders, investigations and revocations from 2018 to 2023

Note: Guardianship orders include new orders and orders where the Public Advocate is reappointed to be someone's guardian.

Source: VAGO, based on data from the office.

Investigations

Investigation referrals

VCAT can ask the office to investigate a wide range of matters, including:

- whether a person has decision-making capacity

- allegations of abuse, neglect, exploitation or unauthorised restrictive practices, such as chemical or physical restraint

- whether the person has health issues or family conflict.

These factors help VCAT decide if a person needs a guardian.

The office must gather enough evidence to address questions VCAT has about a person's decision-making capacity and other important information and report back to VCAT.

Figure 3 shows the potential outcomes from an investigation.

Figure 3: Potential outcomes from the office's investigations

Note: A supportive guardian is appointed by VCAT to support a person with disability to make their own decisions. A supportive guardian has the legal authority to do things like access information from third parties about the person and act as an intermediary between the person and other people or organisations to fulfil their role. The Public Advocate cannot be appointed as a supportive guardian.

Source: VAGO.

Investigations can divert proposed represented people from public guardianship. This is a positive outcome because it:

- limits restrictions on the proposed represented person's decision-making where possible

- reduces the number of guardianship orders the office has to manage.

We found the office can improve how it:

- gathers information for VCAT

- consults with proposed represented people

- completes investigations within its timeframes.

The office's performance in these areas may reduce VCAT's ability to make informed decisions about whether to appoint a guardian to a person.

Gathering information for VCAT

VCAT asks the office to investigate and gather information, such as a person's disability status, will and preferences, decision-making capacity and the views of any significant people in their life, to determine if a person needs a guardian.

The office gathered all the information that VCAT asked for in 58 per cent of cases we reviewed. In the other 42 per cent of cases, investigators did not do this because:

- they could not get evidence about a person's decision-making capacity or will and preferences

- they only gathered information about a person's will and preferences for some matters, or example, where they want to live but not who could support them to make decisions.

Consulting with the proposed represented person

There is no requirement under legislation or the office's policies for an investigator to speak with a proposed represented person during an investigation.

Despite this, the office consulted with the proposed represented person in 75 per cent of the cases we reviewed.

This helps the office build trust in the system and ensure a person's voice is heard.

The office could further improve this consultation by requiring investigators to meet with proposed represented people in all its investigations unless exceptional circumstances apply.

Timeliness of investigations

The office receives some urgent investigation referrals from VCAT where the proposed represented person:

- needs an urgent assessment

- may need a guardian appointed quickly.

We found that the office manages most of these orders in a timely way. Between 1 July 2018 and 30 June 2023, it reported back to VCAT within 3 days for 90 per cent of urgent referrals.

The office has different target timeframes to respond to non-urgent investigations depending on their risk level. But it is not meeting these timeframes.

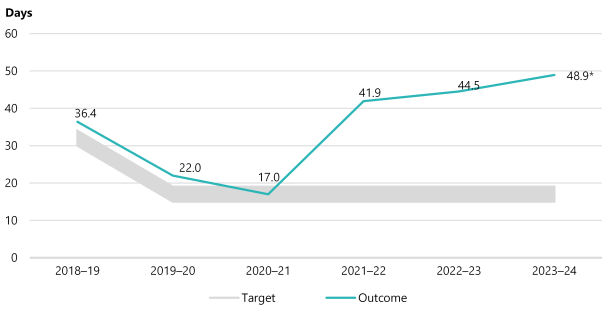

As Figure 4 shows, the office's median time to complete non-urgent investigations exceeded its internal targets between 2018 and 2023.

Figure 4: Timeframe to report back to VCAT on non-urgent investigations from 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2023

| Risk level | Target (business days after allocation) | Median time to report back from 2018 to 2023 (days) |

|---|---|---|

| Low | 20 | 91 |

| Medium | 10 | 68 |

| High | Immediately | 52 |

Source: VAGO, based on data from the office.

There are some external factors that may influence the office's ability to meet investigation deadlines.

For example, some investigations require the office to consult with specialist doctors who have long waiting lists. Or the office may need to wait to receive information from other agencies about a proposed represented person.

Investigation delays mean that proposed represented people may need to wait for months to find out whether a guardian will be appointed to them.

In high-risk cases, there is also a risk that people will remain in unsafe situations until the office completes its investigation.

Starting guardianship orders

Starting guardianship orders in a timely manner

After it receives a guardianship order from VCAT, the office's process is to:

- place the order on its waitlist

- make any urgent decisions for the person while they are on the waitlist

- allocate the order to a guardian when one becomes available.

It is important that the office allocates guardians as quickly as possible to ensure that decisions are made in a timely manner and supported by up-to-date information. Allocating orders in a timely way also helps build trust with clients.

We found delays in the office:

- receiving orders from VCAT

- allocating orders to guardians.

In 2023, the office started a pilot program to help manage its waitlist and improve its timeliness and engagement with clients at the beginning of guardianship orders.

Receiving orders from VCAT

Once VCAT makes a guardianship order or investigation referral, it sends the case to the office to action.

But between 1 July 2018 and 30 June 2023, it took VCAT an average of 10 days to send an order to the office.

The office's timeframe to allocate a case starts when it receives the order from VCAT. But these administrative delays at VCAT extend the length of time a client must wait for a guardian to be allocated to them.

The office requests monthly reports from VCAT about the orders it makes to minimise the impact that delays have on its operations.

Allocating orders

The office has public BP3 performance measures and targets. One of these targets is the amount of time it takes to allocate new guardianship and investigation orders.

In 2018–19 this target was between 30 to 34 days. In 2019–20 it was lowered to between 15 and 19 days.

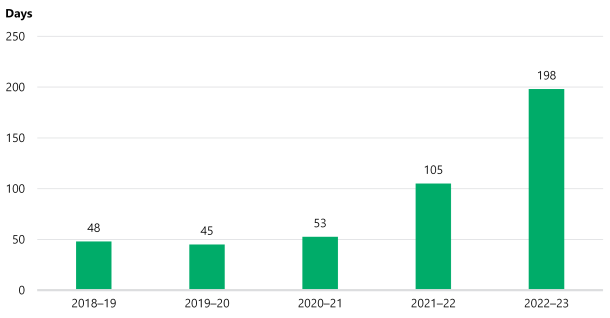

Figure 5 shows that since 2018, the office only met its target in 2020–21.

Figure 5: Time to allocate new guardianship and investigation orders against its BP3 target from 2018 to 2024

Note: *The 2023–24 result is an expected outcome based on the office's data from 1 July 2023 to 20 February 2024.

The 2019–20 BP3 says that the office's target decreased in 2019–20 to reflect the office's 'anticipated increased capacity to reduce the time individuals with disability wait for the allocation of a delegated officer due to the flow-on impacts of increased funding in the 2018–19 Budget'.

The office told us that the delay in allocating orders in previous years is due to several factors, including significant uptake of the Victorian Government's early retirement packages in 2022 and 2023 as well as the ongoing impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This figure excludes cases where the Public Advocate was reappointed. This is because these orders are typically allocated immediately to the same guardian that previously managed the case.

Source: VAGO, based on data from the BP3 and the office between 1 July 2018 to 20 February 2024.

It is important for the office to allocate cases to guardians within its target timeframe.

While the office has guardians that can make decisions for people on the waitlist, it is important for guardians to build trust with a represented person and find out their will and preferences.

Managing the office's waitlist

When the office receives an order, it puts it on a waitlist until it can allocate the order to a guardian. We discuss the allocation process further in Section 2.

If a represented person needs to have an urgent decision made for them, the office's intake team has guardians who can step in.

Intake guardians typically make decisions that are not irrevocable. For example, they would not independently consent to move a person to a permanent aged care facility.

The office told us that its intake team also advocates for people on the waitlist and seeks a person's will and preferences when it has capacity.

For example, it may advocate for the person to transition to a less-restrictive option than guardianship, such as supported decision-making, where appropriate. But this is not always possible when there are many cases on the office's waitlist.

As the table below shows, the office has several initiatives to improve its engagement with clients and is currently trialling a new structure in its intake team. This is a positive change to help the office contact represented people earlier.

| Before its pilot initiative … | But under the pilot initiative the office has … | Which … |

|---|---|---|

| the office's intake team, which included guardians, primarily responded to people's urgent needs while on the waitlist, unless they had capacity to do additional work, such as finding out a person's will and preferences | increased its intake team's resources so staff have more capacity to start working on orders and contact people before they are allocated a guardian | is intended to:

Initial staff reports have been positive but further time is needed to assess the success of this initiative. |

| Guardianship and investigation teams only had VPS 5 level guardians, investigators and team leaders | integrated officers at a VPS 4 level to some of its guardianship and investigation teams to provide administrative support | has allowed guardians in these teams to engage more quickly and frequently with represented people. |

| the office had one waitlist, which held all orders waiting to be allocated to all guardianship teams |

|

|

| the office's team leaders monitored the waitlist through a weekly meeting using a manually updated spreadsheet | introduced a new data visualisation report for guardianship orders | has helped team leaders and the office's executive team track and action orders on the waitlist more effectively. |

Note: All of the office's pilot programs started in 2023. VPS means Victorian Public Service.

Finding out a represented person's will and preferences

Understanding a person's will and preferences

Under the Act, a guardian must actively find out and enact a person's will and preferences as far as practicable when making decisions for them.

| The Act says that if a guardian cannot find out a person's … | Then they must ... |

|---|---|

| will and preferences | find out what they are likely to be. |

| likely will and preferences | act in a manner that promotes the person's personal and social wellbeing. |

Good communication and strong engagement with a represented person help the office:

- build trust so the represented person feels comfortable sharing their will and preferences about sensitive issues, such as who can contact them and where they should live

- understand a represented person's circumstances to inform the office's decisions

- respond to a represented person's needs throughout an order

- make sure it is enacting a person's up-to-date will and preferences.

But we found issues that limit the office's ability to communicate and engage well with clients. In particular, the office did not:

- contact clients in line with its policies in 50 per cent of the cases we reviewed

- physically meet with clients in line with its policies in all the cases we reviewed

- consistently document contact with the represented person and their will and preferences.

Lived experience of a former client

We consulted with people who had a guardian or investigation and asked them to share their feelings and experiences about guardianship. We also accepted submissions from the public about their lived experience.

VAGO acknowledges that the office was not able to respond to individual stories due to their anonymous nature.

We did not independently verify the accuracy of information provided to us through these consultations and submissions. And we did not verify if the expectations of the people we spoke to are consistent with guardians' requirements.

The people we spoke to told us that the most important thing the office could do for them is to listen. See Appendix D for the other stories we heard.

Figure 6: Lived experience of a represented person

Matthew told us about a situation where he said his guardian decided to remove him from his accommodation. He had to ask to stay with a family member, despite having previous altercations with another family member in that house.

Matthew was then put in refuge housing, which he said was not suitable for him and led him to be asked to leave.

He told us, 'they* didn’t listen to me, they didn’t hear where I was coming from. They just thought they knew what was best, but they didn’t know me'.

He also said the guardian’s communication about decisions could have been better. 'They didn’t tell me about the decisions they made, they just made them'.

When asked what would have changed if his guardian had listened to him, Matthew said it would make him feel 'human and wanted'.

He told us guardians should visit represented people to understand what they want and to tell them how they can complain.

Note: *We changed the person's name and identifying details to protect their anonymity.

Source: VAGO.

Contacting the represented person after allocation

Once the office allocates an order to a guardian, the office requires the guardian to contact the represented person within 10 days.

The office's staff told us that it may sometimes be appropriate for a guardian to contact another person, such as a person's doctor, to find out more information before contacting the represented person.

In 50 per cent of the cases we reviewed, the office did not contact the client within its 10-day target.

We could not determine the average time it took the office to contact a represented person between 2018 to 2023 because the office:

- inconsistently records interactions in its CMS

- does not have data validation and quality controls for its CMS.

This also limits the office's ability to oversee guardians' performance and monitor if they meet the office's legislative requirements and policies.

Visiting represented people

Physical visits are important because they can help a guardian build trust with the person they are representing, communicate with them more clearly and understand their will and preferences.

| For the cases we reviewed ... | Of guardians did not physically meet with the represented person ... | Even though this is required by … |

|---|---|---|

| 63% | within 28 days of being allocated to a case | the office's polices. |

| 88% | once a year for orders that lasted longer than one year | the Standards. |

The office's data also shows that 25 per cent of represented people waited more than 6 months for a guardian to physically visit them for the first time between 2018 and 2023. This result may be impacted by the office's poor data quality.

The office told us that COVID-19 restrictions impacted its ability to visit clients during 2020 and 2021.

The office records a video call as the same 'action' as visiting a client face to face in its CMS. So it is difficult to quantify the pandemic's impact on guardians visiting clients.

Documenting contact with represented people

Guardians should document their contact, including visits and phone calls, with represented people in the office's CMS. But we found gaps in this documentation.

Figure 7 shows an example of how these gaps reduce visibility over guardians' contact with clients and how they make decisions.

Figure 7: Case study: Gaps in documenting contact with a represented person

In this case, VCAT appointed the Public Advocate to make a decision about a person's accommodation. But the first documented contact with the represented person was 8 months after the office allocated the order to a guardian.

The guardian made a decision about the represented person's accommodation more than one year after their last documented contact with them.

In the case file, the guardian noted that this decision was in line with the represented person's wishes from 'some time ago'. However, there was not any documentation to show that the guardian contacted the person before making the decision to make sure this is still what they wanted.

This lack of documentation means it is not possible to know if the guardian made this decision in line with the represented person's current will and preferences.

Source: VAGO, based on case files from the office.

Documenting a represented person's will and preferences

It can take some time for a guardian to find out a represented person's will and preferences, which can change over time.

For example, some represented people have different communication styles or abilities. When they are not with someone who knows them, it may be difficult for a guardian to understand what the person wants.

The office may need to consider a represented person's background, previous preferences and the views of people close to them to understand their will and preferences, while managing other cases as well.

Despite these complex circumstances, we found that the office:

- adequately documented the represented person's will and preferences in 76 per cent of the cases we looked at

- partly documented them in a further 24 per cent of cases (for example, the guardian documented a person's will and preferences, but did not update or check them for over a year).

The office's CMS has a specific field to record a person's will and preferences. But we found that guardians did not always use it.

Given guardianship case files can have thousands of recorded emails, phone calls and other documentation over the life of an order, staff could improve transparency and efficiency by using the right fields to record information.

We also found that guardians did not document how they determined a person's will and preferences in 33 per cent of cases we reviewed. For example, documenting that the person told the guardian their preferences when they visited them.

Represented people's human rights

Overview

The Charter outlines 20 human rights that all people have.

As a public authority, the office must 'give proper consideration' to a person's human rights when it makes decisions on their behalf and act compatibly with those rights.

The office's policies and staff training about human rights are strong. It also requires staff to document their consideration of human rights. But we found guardians did not do this in most cases we reviewed.

Guardians must consider the risk of harm to a represented person when they decide if they can enact their will and preferences.

The office can improve its guidance for guardians to help them make these difficult decisions.

The office's obligations

There are some situations where a public authority's obligations under the Charter do not apply.

For example, if a public authority could not reasonably have acted differently or needed to make a particular decision in line with another law.

The nature of guardianship means that guardians must sometimes limit a represented person's rights, including their right to choose where they want to live or travel.

The Charter allows this, but only so far as can be demonstrably justified. Delays in allocating or revoking a case may mean that a person is under a guardianship order for longer than required, which could impact people's rights under the Charter and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

Article 12 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities sets out the right of people with disability to legal capacity, or the right to act and make decisions and have those decisions legally recognised.

The Australian Government's interpretive declaration on Article 12 allows for fully supported or substituted decision-making arrangements only where such arrangements are necessary, as a last resort and subject to safeguards.

One of the convention's safeguards is that measures relating to the exercise of legal capacity of persons with disability apply for the shortest time possible.

The office's training and policies

The office regularly provides training to guardians on the Charter and how it impacts their work. It also has policies that require guardians to consider a represented person's human rights.

These are positive measures that help guardians meet their legal obligations.

Documenting consideration of human rights

It is important for a guardian to document how they considered a represented person's human rights when they make a decision because:

- it helps the office make sure guardians act in line with the Charter

- it makes a guardian's decision-making process more transparent, which is important if someone requests the office to review a guardian's decision.

However, we found that in 82 per cent of cases we reviewed where a guardian made a decision that was not in line with the represented person's will and preferences, the guardian did not appropriately document how they considered the person's human rights.

Dignity of risk

People with disability have the right to what the Australian Government's National Standards for Disability Services calls the 'dignity of risk'. This means that a person has the right to choose to take some risks in their life.

A guardian can only override a person's will and preferences if there is a risk of serious harm. The Act does not define serious harm and there is a risk that individuals may interpret this differently.

The office's risk management framework says it has a low to moderate risk appetite. It provides training and guidance to guardians about how to consider the risk of serious harm to represented people, such as the risk of death or severe physical injury resulting from a decision.

But this guidance does not cover how guardians should balance the risk of non-life-threatening harm with a person's rights.

Guardians must exercise professional judgement to determine when the risk of harm overrides a person's will and preferences or human rights, such as freedom of movement.

Figure 8 shows an example of the type of complex decisions guardians need to make for represented people.

Figure 8: Case study: Balancing risk and rights in challenging circumstances

The represented person often 'absconded'* from their accommodation to a different suburb. They did so more than 10 times over 6 months.

The person's support coordinator told the guardian they thought the person wanted to socialise with people from their cultural background in the area.

The person's guardian had concerns that the person may have been using illicit drugs when they left their accommodation. They made an application to VCAT under section 45 of the Act to enable an ambulance to transport the person back to their accommodation without their consent.

The guardian told the person's accommodation manager to request an ambulance using section 45 powers if they did not want to return home in the future.

In this case, the guardian had to balance the risk of harm to the person with their right to freedom of movement.

Note: *The office used the term 'abscond' to describe the represented person leaving their accommodation in the case file.

Source: VAGO, based on case files from the office.

Represented people have different abilities, backgrounds and life circumstances that inform the risks they face.

While each case may require different risk management strategies, the office could improve its guidance for guardians to help them make these difficult decisions.

Making decisions for represented people

The importance of good decision-making

VCAT appoints a guardian to make specific decisions about a represented person, such as:

- where they live

- the services they can access

- who can contact them

- their healthcare.

To make a good decision, the guardian must consider:

- what options are available for the person

- any risks to the person

- what the person wants (or their will and preferences)

- the views of any significant people in their life

- the timing of their decision.

After considering these factors, the guardian must make their decision and tell the represented person what they have decided.

Considering risks and options

The Standards say that guardians should consider options and risks associated with a decision.

The office's policies require guardians to consider the risks associated with their decisions. But they do not require guardians to consider all reasonable options that may be available.

We found that guardians did document how they considered both the risks and options associated with their decisions in 86 per cent of cases we reviewed.

This suggests that guardians regularly consider different options and the potential impacts of their decisions to ensure they are achieving a good outcome for a represented people.

But the office could clarify its guidance to guardians to ensure:

- this is consistent practice across the office

- guardians are confident in balancing risks with a person's will, preferences and human rights.

Enacting a represented person's will and preferences

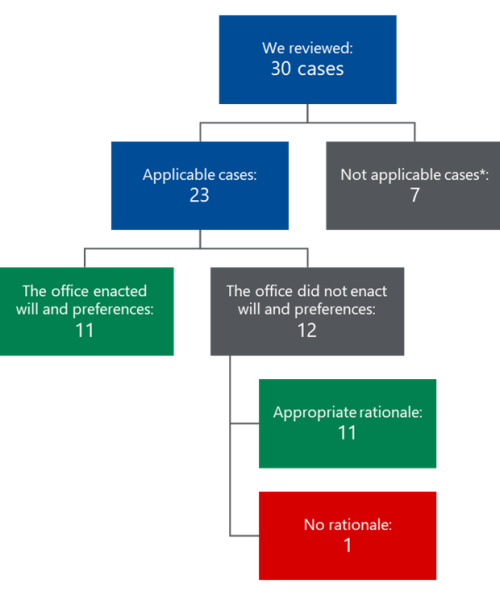

As Figure 9 shows, in all but one case we reviewed, guardians made decisions that either:

- enacted the represented person's will and preferences

- did not enact the person's will and preferences but appropriately justified why. For example, a guardian can decide to override a person's will and preferences if enacting them would cause the person serious harm.

It is important that guardians document their rationale for not enacting a person's will and preferences to demonstrate that their decision meets the Act's requirements.

Figure 9: Our analysis of whether the office's decisions enacted a person's will and preferences in 30 cases we reviewed

Note: *Our testing was not applicable for these 7 cases. For example, some cases did not have any documented decisions.

Source: VAGO, based on case files from the office.

Making timely decisions

Guardians can only make decisions when there are suitable options available.

For example, when a guardian decides where a represented person will live, their accommodation options may be limited by:

- the low level of available rental properties in Victoria

- demand for NDIS-approved specialist disability accommodation

- funding available to the represented person.

We assessed a selection of guardianship cases to see if the office made decisions in a timely way. As part of this review, we considered if guardians had documented any issues with identifying suitable options for the represented person.

We found that the office did not make timely decisions for 31 per cent of the cases we reviewed.

Telling the represented person about a decision

The office's policies require guardians to visit represented people before they make a decision on their behalf. This is in line with the Standards' requirements. There are some cases where it may not be practical for the office to contact the represented person due to their disability or circumstances.

In 52 per cent of the cases we reviewed the office did not contact the represented person before making a decision on their behalf.

It is important the office talks to the people it represents about decisions to ensure:

- it is considering a person's current will and preferences

- the person knows the outcome of the decision.

Revoking guardianship orders

Revoking orders in a timely way

Guardianship orders are intended to remain in place for as long as required to make necessary decisions for represented people.

The length of an order depends on the type of order VCAT makes.

Sometimes, a person does not need a guardian anymore but still has time remaining on their order. In these cases, it is important that the office gathers evidence that the person no longer needs the order and submits this evidence to VCAT so it can revoke the order.

When orders should be revoked

VCAT can specify how long a guardianship order will last when it makes the order.

| A guardianship order can be ... | Which means ... |

|---|---|

| self-revoking | the order automatically ends at a specified date, usually one year after it starts. |

| not self-revoking | the order will remain in place until VCAT assesses the order. |

In some cases, a represented person may no longer need a guardian but their guardianship order may not be due to end for some time. This could be because the:

- guardian finished making all the necessary decisions

- person's circumstances changed and no further decisions are needed.

In these circumstances, guardians must gather evidence that shows the person no longer needs an order and apply for VCAT to revoke it.

Why some revocations are delayed

In testimony provided to the Australian Royal Commission into Violence, Neglect, Abuse and Exploitation of People with Disability, the Victorian Public Advocate noted that guardians may not prioritise gathering this evidence due to their high workloads and competing demands.

For a guardianship order to be revoked, staff at the office may also need to do significant work to make sure the person will have supports in place to safeguard and promote their rights once the guardianship order ends.

This can contribute to delays in revoking orders, which means that a represented person may be under a guardianship order for longer than required.

The office does not consistently collect data to quantify the delays caused by these circumstances.

Delays at VCAT can also impact reassessment hearings. As of February 2024, the office had 57 orders that were overdue for a VCAT reassessment. These orders were an average of 96.6 days overdue.

VCAT has a process to automatically revoke orders that the office recommends should be revoked. Under this process, VCAT makes an order (without a hearing) that explains that the guardianship order will automatically self-revoke after a 2-week period, as long as a person with a direct interest or party does not object. If someone objects to the order being revoked, the matter will be heard at a reassessment hearing.

It is important for the office to take proactive steps to revoke orders when they are no longer needed. Doing so promotes represented people's human rights and improves the office's capacity to manage new orders.

Handling complaints

Transparent and timely complaint handling

Complaints can give an organisation valuable information about their clients' experience and gaps in their performance.

It is important that the office:

- encourages complaints from clients

- manages complaints fairly and within its target timeframes

- uses complaints to improve its processes.

Encouraging complaints

The office's policies meet most of the Victorian Ombudsman's guidance on better-practice complaint management.

But the office could do more to encourage complaints from clients.

For example, at the beginning of a guardianship order the office does not tell a represented person:

- that they are allowed to make a complaint

- how to make a complaint.

As a result, represented people may not understand the office's complaint process and how to use it if they have an issue they need addressed.

This limits the office's ability to identify and fix any systemic issues.

Managing complaints

We reviewed 20 complaints from 2018 to 2023 to assess how the office manages them. For all the complaints we looked at, the office assigned a separate officer to the one involved in the complaint to review it, which is good practice.

But the office can improve other aspects of how it manages complaints.

| The office ... | However, it ... |

|---|---|

| assigned a separate person to review each of the complaints we reviewed, which helps the office make sure it handles complaints fairly and independently. | has not provided training to staff on managing complaints since before 2018. This increases the risk that staff may not manage complaints consistently or in line with the office's policies. |

| handled complaints in line with its own target timeframes in 72% of cases we reviewed.* | did not clearly communicate the outcome of the complaint in 39% of the cases we reviewed. Of the remaining 61% of complaint cases where the office did communicate the outcome, the office did not tell 36% of complainants how to appeal their cases. |

*The office aims to resolve routine complaints within 10 days, moderately complex complaints within 30 days, and multiple or complex complaints within 90 days

Using complaints to improve processes

The office can improve its training for staff, timeliness and communication with complainants to make sure it handles complaints consistently and in line with better-practice guidance.

The office could also do more to learn from complaints and use them to improve its processes.

The office reviews complaints in a quarterly meeting to discuss its services and potential improvements.

But the office does not look at complaint trends over time or document if it analyses complaints to assess if issues are systemic.

The office can also improve its guidance to staff on what complaints they need to escalate to the executive team.

2. Managing and overseeing resources

The Office of the Public Advocate does not fully understand the time, costs and amount of work it needs to deliver its services. This limits its ability to strategically plan and allocate its resources.

The office can also improve how it manages and monitors its services to make sure it protects and promotes the rights and interests of its clients.

Financial and organisational planning

Why strong organisational planning is important

All organisations and government agencies, including the office, operate within resource constraints. So the office must plan how it uses its resources to deliver its objectives.

To do this, the office must understand:

- what services it needs to deliver

- what resources it needs to do this, including the number of people, type of skills and funding.

We found that the office has a strong strategic plan that sets out its objectives. It also has a good understanding of the services it needs to deliver.

But we found it does not have a good understanding of the time, cost and amount of work it takes to deliver these services.

These issues compromise the office's ability to:

- determine what resources it needs in the future

- plan its workforce to meet these needs.

The office relies on lapsing funding to deliver its guardianship and investigation services. It told us that the uncertainty in its funding affects its ability to plan for the future.

However, the office should still plan and manage its resources within its existing resource constraints.

The office's funding sources

The office receives an appropriation each year via the department's output for advocacy, human rights and victim support. This includes base funding and lapsing funding for specific programs or projects.

The office also gets a small amount of its funding from other agencies, including the Department of Health and the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, to deliver specific projects and services.

The office must make a business case to the Victorian Government for extensions to lapsing funding. It must make requests for additional funding requests through the relevant department.

Base and lapsing funding

Base funding is ongoing funding that the Victorian Government allocates to the office each year. The government indexes this funding to account for inflation.

Lapsing funding is funding that the government provides for a specific, time-limited period.

Funding for investigation and guardianship services

The office received $18.7 million of funding in 2022–23.

In 2022–23, $12.4 million of the office's funding was for its guardianship and investigation services.

The office used the rest of its funding for other services, such as its Community Visitors Program.

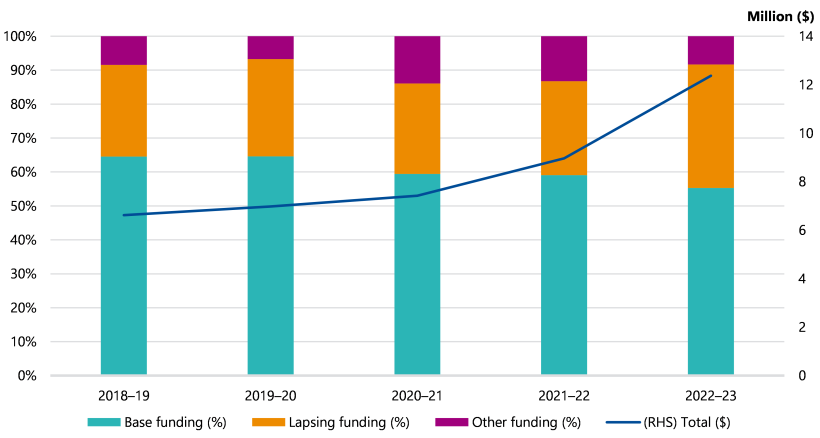

As Figure 10 shows, a proportion of the office's funding is either lapsing or from other sources.

Figure 10: The office's funding for guardianship and investigation services between 2018–19 and 2022–23

Note: Other funding is the office's funding for the guardianship in hospitals and health service guardianship projects. This funding is administered with a memorandum of understanding with the Department of Health. The Department of Health determines this funding each year. RHS refers to the right-hand side axis.

Source: VAGO, based on data from the office.

Funding impacts

In total, $4.5 million of the office's guardianship and investigations funding in 2022–23 was lapsing funding. This was out of a total of $12.4 million funding for these programs.

Typically, lapsing funding is for specific, time-limited projects. The office has received lapsing funding for at least the last 5 years (between 2018–19 and 2022–23).

In 2022–23, 36.4 per cent of the office's funding for its guardianship and investigation services was lapsing. This included funding to extend 14 guardianship and investigation staff positions.

The office relies on this funding to deliver its guardianship and investigation services. It told us that this:

- limits its ability to plan its services in the long term because it is uncertain about its future funding

- has contributed to turnover in these programs.

However, the office should still plan and manage its resources within its existing resource constraints.

Strategic planning

The office released its Strategic Directions 2023–2026 in July 2023.

Program plans support the strategic directions. The plans outline the office's priorities and the actions it plans to take.

| The office's plan for its … | Includes actions such as… |

|---|---|

| guardianship program |

|

| advice and response division, which includes its investigation and intake teams |

|

Understanding the components of its service delivery

One of the office's strategic priorities is to make sure that its budget and resources reflect its role and functions.

To do this effectively, the office needs to clearly understand the different components that contribute to the delivery of its guardianship and investigation services.

The office does not control the number of VCAT referrals it gets and the volume of work this generates.

However, the number of guardianship and investigation orders from VCAT was stable between 2018–19 and 2022–23. The office monitors and reports this data.

While the total number of cases has remained stable, some cases are more complex than others. We found gaps in the office's understanding of the components that contribute to the delivery of its guardianship and investigation services.

| We found gaps in the office's understanding of … | Because … |

|---|---|

| how long it takes for staff to action and complete an order | it does not track how long it takes to deliver services at an order level. |

| how much it costs to action and complete an order |

|

| how much work it takes to deliver its services | data entry issues make it difficult to determine how many decisions and actions are needed to deliver its services. We talk about this in more detail below. |

| the complexity of its services |

|

| future demand for its services | it has not modelled future demand. |

| the number of staff it needs to deliver its services | it has not determined the appropriate caseload for staff to operate effectively and efficiently. The office told us this is complex due to WorkSafe Victoria's cap on guardian caseloads. |

This means that the office does not have the right information to:

- identify the resources it needs to deliver its services

- plan and implement a workforce model to effectively delivers its services.

The office's workforce

Having the right workforce resources to deliver services

It is important that the office has the right staff skills, capabilities, behaviour and experience to deliver its services effectively.

Since 2022, the office has had higher staff turnover than in previous years. This is because 15 staff from its guardianship and investigation programs accepted the Victorian Government's early retirement packages.

The department must approve the office's recruitment at several stages. The office told us that this leads to delays in filling vacant positions.

The office revised its staff supervision process in 2023. This is a positive step that should help the office to consistently review staff performance.

But we found gaps in the office's staff training and supervision process before it introduced its new process. These issues limit the office's ability to:

- identify and address gaps in skills or knowledge across its programs

- determine if it needs additional, or a different mix of, resources to deliver its services.

Staff data

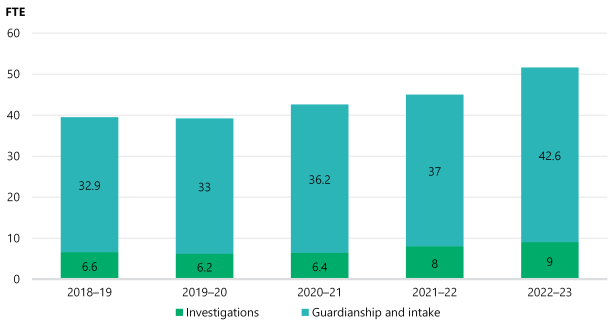

Most of the office's expenses are staffing costs. As Figure 11 shows, the office had 51.6 full-time-equivalent (FTE) staff in its guardianship and investigation teams in 2022–23. This includes:

- team leaders

- support officers

- guardians

- investigators.

Figure 11: Number of FTE staff in the office's guardianship and investigation teams between 2018–19 and 2022–23

Source: VAGO, based on data from the office.

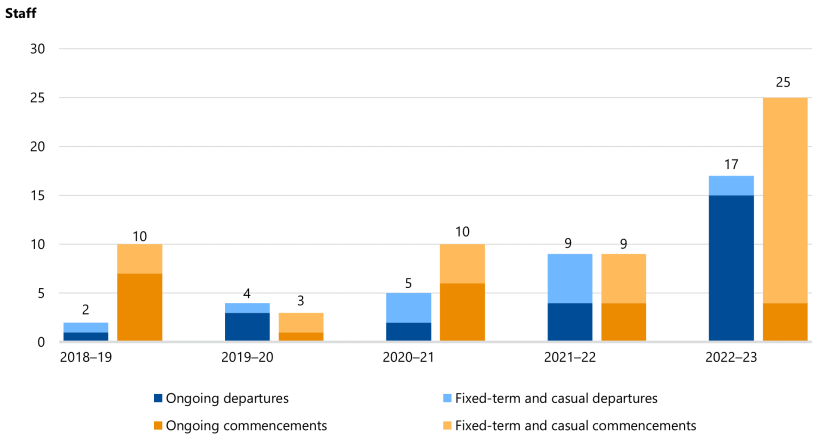

The office's turnover

The office's guardianship and investigation programs had high staff turnover in 2022–23.

In 2022–23:

- 25 new staff started

- 17 staff departed.

Over 40 per cent of positions in the guardianship and investigation programs are fixed-term positions.

The office told us that this, as well as staff take-up of the government's early retirement packages in 2022 and 2023, has contributed to higher turnover.

Figure 12: Staff departures and commencements in the office's guardianship and investigation program between 2018–19 and 2022–23

Note: Numbers in the graph detail total commencements and departures.

Source: VAGO, based on data from the department.

The impact of staff turnover

The office told us that it takes between 6 to 12 months for new guardians to carry similar caseloads to other staff. This may contribute to workload pressure and delays in allocating orders.

High turnover can also lead to higher staff recruitment and training costs. However, turnover can bring opportunities for:

- existing staff to develop through promotions and acting arrangements

- the office to recruit new staff with different skills and experiences.

Recruiting staff to fill vacant positions

It is important for the office to recruit staff as efficiently as possible to minimise the impact of vacancies.

As the office is a business unit of the department, it cannot independently recruit staff. It must also follow the department's recruitment policies and processes.

Figure 13 shows which recruitment steps the office can complete independently.

Figure 13: Recruitment steps the office can and cannot complete independently

| Recruitment step | Can the office independently complete this step? |

|---|---|

| Advertise for vacancies | ✕ |

| Advertise externally if advertising on the Jobs and Skills Exchange has been unsuccessful | ✕ |

| Fill internal temporary vacancies of up to 6 months without advertising (temporary assignment) | ✓ |

| Fill internal temporary vacancies for more than 6 months (higher duties assignment or fixed-term contract) | ✕ |

| Appoint the next-ranked candidate in a competitive recruitment process | ✕ |

| Make a job offer to a staff member for non-executive positions | ✓ |

Source: VAGO, based on information from the department.

As Figure 13 shows, the office needs the department's approval for all key steps in the recruitment process except filling temporary vacancies and making job offers.

The office told us this contributes to delays in recruiting staff because:

- its staff in these programs require specialist skills that may not always be available within the public service

- it needs the department's approval to recruit outside the public service.

As Figure 14 shows, it took the office an average of 198 days to recruit new guardianship and investigation program employees in 2022–23.

Due to gaps in the department's data, we could not assess how long it took the department to approve the office's recruitment.

Figure 14: Average number of days to recruit for roles in the office's guardianship and investigations programs

Note: This graph shows the days between a request being entered into the department's recruitment system and when that request was marked as filled in the system.

Source: VAGO, based on data from the department.

Understanding of staff capabilities

The office has not mapped its workforce's capabilities, skills and training needs. This may limit its ability to:

- understand the skills staff need to deliver its services

- make sure its training meets staff needs and job requirements.

The office delivers formal training to its staff that covers key aspects of its services. But there are gaps in this training. For example:

| The office's formal training covers … | But does not cover … |

|---|---|

| its legislative requirements under the Act and the Charter | the Standards, which include guidance and principles for providing best-practice public guardianship. |

| internal requirements and guidance for staff. For example, guidance on how to manage and action an order. | |

| how to manage and resolve complaints. |

The office does not consistently document the training sessions it has run and which staff have attended.

In addition to formal training, staff do on-the-job training and supervision sessions with their team leader.

In supervision sessions, team leaders may identify areas where staff can grow their capabilities. But the content and frequency of these sessions varies between teams.

Gaps and inconsistencies in the office's training, documentation and supervision sessions limit its ability to:

- monitor staff capabilities

- identify and address gaps in skills or knowledge

- make sure that staff have the support and skills to effectively do their jobs.

The office introduced a new supervision process in 2023. This is a positive development that should help to standardise supervision sessions.

Systems and ways of working

Why effective systems are important

The office must have appropriate systems and processes that enable it to govern and support staff to deliver its services. For example:

- technology, including its CMS

- processes, such as its process for allocating orders.

As we discuss in Section 1, the office introduced support officers to its guardianship and investigation programs in 2023.

This is a positive development because these staff help reduce guardian and investigator workloads.

But we found issues in the office's key systems and processes.

| We found ... | Which ... |

|---|---|

| staff do not use the office's CMS consistently | can reduce their efficiency and the office's ability to oversee their performance. |

| the office has not determined the ideal caseload for staff to operate effectively |

|

| the office does not consistently use its complexity tool to assess orders | may make its allocation process less effective. |

The office's CMS

The office's CMS stores important information about its clients, including:

- details about an order, such as the decision/s that need to be made

- a client's will and preferences

- information on a client's situation, including any issues

- decisions made about a client, including why each decision was made

- emails, documents and actions related to an order.

Data collection and reporting

The CMS is crucial to the office's delivery of its guardianship and investigation services.

It is important that the CMS has high-quality data and enables staff to work efficiently and effectively.

However, we found that staff do not use the system consistently.

During our file review we observed:

- information, documents and emails duplicated throughout a client's case file

- inconsistent information in a client's case file

- information missing from a client's case file.

Multiple reviews of the office's CMS have found similar issues. The office obtained a quote to implement recommended changes from these reviews. But it has not engaged a supplier to address the recommendations yet. The office told us it does not have a dedicated budget to update its CMS.

This means the CMS does not give staff quick and easy access to the information they need to deliver the office's services. It also limits the office's ability to monitor and report on its performance.

Allocating orders

Figure 15 shows the office's process for allocating guardianship and investigation orders to staff.

It is important for the office to use its resources effectively. To do this, it needs to:

- identify and prioritise allocating high-risk orders

- allocate orders based on the skills, experience and capacity of its staff.

Figure 15: Process to allocate new guardianship and investigation orders

Note: Guardianship reappointments do not follow this process. Reappointments are allocated to the same guardian.

Source: VAGO, based on information from the office.

Assessing risk

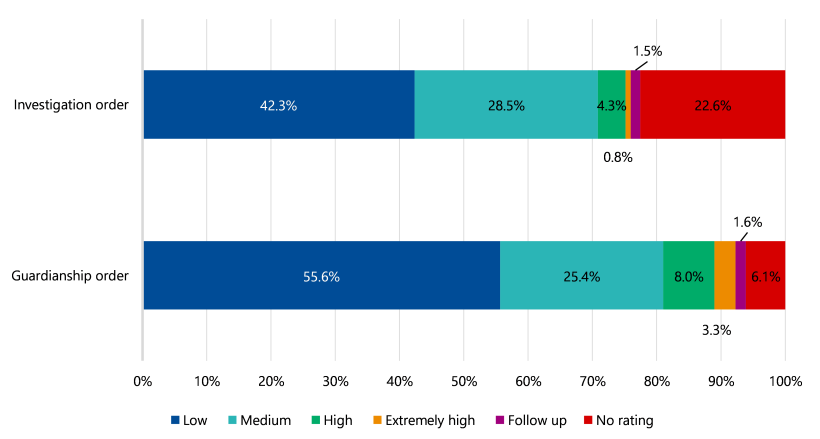

As Figure 15 shows, the intake team and investigations team leaders assess the risk of orders. This information is used to prioritise and allocate higher-risk orders.

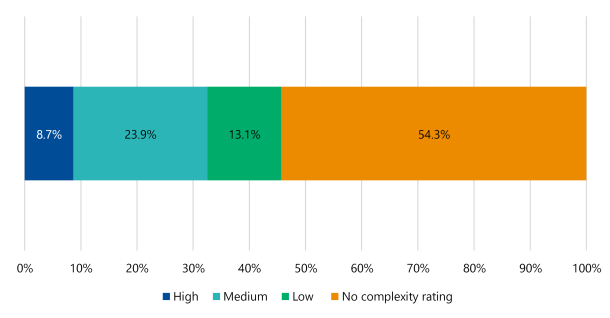

However, as Figure 16 shows, some orders received between 2018–19 and 2022–23 did not have a risk rating.

Risk rating

The office bases risk ratings on the risks a person may face without having a guardian. Risks can include life threatening medical conditions or injuries due to abuse or neglect.

Figure 16: Risk ratings for orders the office received from 2018–19 to 2022–23

Note: This analysis excludes guardianship reappointments because these orders are not risk rated.

Source: VAGO, based on data from the office.

This may reduce the office's ability to identify and immediately action all high-risk cases.

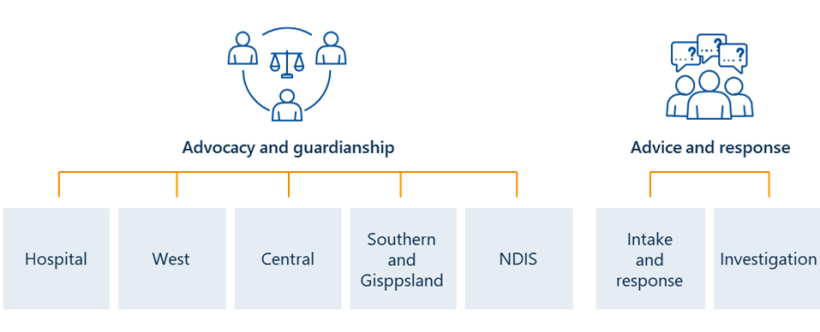

Allocating orders to teams

As Figure 17 shows, the office has 5 regional and specialist guardianship teams, an intake team and an investigation team.

Figure 17: The office's guardianship and investigation structure

Note: The advice and response team also includes the medical decision treatment team and the advice and education team. For simplicity, these teams are not shown here.

Source: VAGO, based on information from the office.

As we discuss in Section 1, the intake team monitors orders before they are allocated.

The region based team structure allows staff to:

- visit clients near their workplace and in groups

- build an in-depth understanding of the services in a particular area.

However, this structure may not allow the office to allocate orders in a timely way because teams will only accept orders when they have capacity.

As Figure 18 shows, certain teams have larger waitlists. This is because there are different levels of demand, capacity and experience in each team.

This means orders may be on the waitlist while staff in other teams have capacity to take new orders.

Figure 18: Waitlisted guardianship orders at 30 June 2023

| Team | High risk | Medium risk | Low risk | No risk rating | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central | 3 | 4 | 9 | 1 | 17 |

| Hospital | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 8 |

| NDIS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Southern and Gippsland | 1 | 9 | 13 | 0 | 23 |

| West | 1 | 9 | 14 | 0 | 24 |

| Total | 6 | 26 | 39 | 1 | 72 |

Source: VAGO, based on data from the office.