Managing Consultants and Contractors

Overview

This audit examined how effectively selected government departments (the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, the Department of Environment and Primary Industries, the Department of Justice and the Department of Treasury and Finance) are managing advisory engagements that help them inform government decisions. It also assessed oversight arrangements applying to these procurement processes, and outcomes and monitoring of consultancy savings targets set by government.

The audit found that departments largely followed the Victorian Government Procurement Board's (VGPB) specific, mandated requirements for engagements of their size and complexity. However, the documentary evidence falls well short of demonstrating that these engagements achieved VGPB's goals of value for money and process integrity.

There are also significant gaps in the way individual departments and DTF, in its whole-of-government role, oversee procurement.

The early evidence suggests that procurement reform is an opportunity for departments to transform the way they govern and manage procurement and address the weaknesses identified in this report.

Managing Consultants and Contractors: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER June 2014

PP No 331, Session 2010–14

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Managing Consultants and Contractors.

This audit examined how effectively selected government departments are managing advisory engagements that help them make decisions.

The report highlights significant gaps in the way sampled departments have managed advisory engagements and in the central oversight of these practices.

It also encourages departments to take the opportunity offered by government's current procurement reform to address these weaknesses and notes the early signs that departments are starting to do this.

I have made eight recommendations to improve how:

- departments demonstrate the integrity and value for money of advisory engagements

- the Victorian Government Purchasing Board and the Department of Treasury and Finance guide and oversee departments' application of government policy to these types of engagement.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

11 June 2014

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Ray Winn—Sector Director Nerillee Miller—Team Leader Louise Gelling—Analyst Chris Sheard—Engagement Quality Control Reviewer |

Departments often use contractors and consultants to provide advice about how to best realise government policy goals. While the costs of these advisory engagements are usually small relative to the service and infrastructure decisions they inform, they are critical because they help shape and direct these much larger expenditures to deliver better outcomes.

In addition, the community rightly expects that departments are able to demonstrate high levels of integrity and value-for-money outcomes when using public funds.

In this audit I found that four selected departments were unable to demonstrate consistently that their advisory engagements had been well planned, effectively procured, well managed, comprehensively evaluated and transparently reported.

The departments generally followed the minimum, mandated rules covering engagements of this scale, but this did not address these issues. I found an absence of a structured, documented and transparent approach to managing these engagements that was tantamount to maladministration.

The departments I examined managed engagements individually, without the type of intelligence gathering, analysis and leadership needed to understand and improve overall performance across all advisory engagements.

This shortfall in oversight also extended to the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) in its whole-of-government role. DTF did not adequately check that departments correctly classified and disclosed advisory engagements, nor verify the savings departments reported against government targets.

These targets were proposed prior to the 2010 election and subsequently adopted without evidence that DTF had reviewed their basis and advised government about their reliability and implications. As a matter of standard practice, DTF needs to verify the basis of all the government's financial commitments and advise it of the implications.

By the end of 2014 all departments should have transitioned to a new approach to procurement. Instead of having to comply with detailed, centrally mandated rules, departments will now be responsible for designing their own detailed practices to achieve high-level reform principles. DTF transitioned in June 2013, and the three other departments included in this audit are likely to follow by August 2014.

The early signs are promising. DTF has upgraded its procurement processes, intelligence gathering and analysis as the basis for improved practices and oversight. The other departments are following a similar development path, and our recommendations encourage them to address past weaknesses.

I intend to return to this area to see whether departments follow through on this promising start to improve their performance in managing advisory engagements.

I would like to thank the Department of Treasury and Finance, Department of Justice, Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, Department of Environment and Primary Industries, and Victorian Government Purchasing Board for their assistance and cooperation during this audit.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

June 2014

Audit Summary

Public sector agencies engage external resources to advise them on how best to realise government policy and to help them implement these decisions. The Department of Treasury and Finance's (DTF) June 2013 definition of a consultancy is the provision of advice to facilitate decision-making, whereas a contractor helps implement decisions.

This audit examined how effectively selected government departments are managing advisory engagements that help them make decisions.

Our audit found that advisory engagements had not been consistently classified because of the way consultancies had been defined before DTF issued the revised definition in June 2013. Prior to this, an engagement for a one-off task to inform a decision would only be classified as a consultancy if the agency judged it to involve 'skills and perspectives not normally expected to reside in the department'.

All engagements are governed by the mandatory supply policies set by the Victorian Government Purchasing Board (VGPB) and two financial reporting ministerial directions. The goals of these policies are to maintain the integrity of the procurement process and deliver value for money from all purchases of goods and services.

While the same principles apply to all procurements, the specific documentation requirements are more prescriptive and specific for high-value—over $10 million—or high-risk contracts. Advisory engagements do not often fall into this category because they mostly cost under $150 000 and make up a small proportion of the $16 billion the general government sector spends on goods and services.

However, they play a critical role in fully informing decisions that involve much larger sums. As with any expenditure of public monies, it is important that departments are able to demonstrate the integrity of these procurements and their value for money.

The VGPB defines value for money as the achievement of a desired procurement outcome at the best possible price—not necessarily the lowest price—based on a balanced judgement of financial and non-financial factors relevant to the procurement. This needs to be demonstrated in the decision to use external resources, throughout the procurement process and after completion through a post-implementation review.

The audit examined whether DTF and the departments of Justice, Education and Early Childhood Development, and Environment and Primary Industries had effectively applied VGPB's requirements for advisory engagements, demonstrating high levels of integrity and value for money through:

- good planning—documenting the essential planning work used to justify the use of external resources, identify risks and choose a preferred procurement

- effective tendering and appointments—applying processes clearly aligned with VGPB's requirements of consistent, fair and transparent treatment, and delivering outcomes consistent with or exceeding the planned value proposition

- sound engagement management—showing how progress had been monitored, deliverables tracked and risks appropriately managed

- comprehensive evaluation—completing a post-implementation review confirming the intended outputs and outcomes and applying the lessons learned.

We also examined DTF's and VGPB's oversight of these procurement processes and outcomes for the Minister for Finance and DTF's monitoring of the $185 million consultancy savings target set by government's Better Financial Management policy.

The conclusions and findings in this report refer to the likely impacts of procurement reform, which represents a fundamental change in how departments manage procurement. VGPB's goal is for all departments to transition to the new procurement approach by August 2014, with DTF being the only department included in this audit to have transitioned in June 2013.

This reform will see VGPB's extensive and prescriptive policies replaced by a set of high‑level reform policies around governance, appropriately matching capable resources to different procurements, market analysis and review, a structured approach to the market and how contracts will be managed and disclosed.

Departments must ensure that the application of these policies in specific processes meets the principles of value for money, accountability, probity and scalability. This puts a greater onus on departments to manage different types of procurement, appropriately aligning capabilities and oversight across procurement types.

The transition will give rise to risks and opportunities. Before making the change, departments have to secure VGPB's approval of a procurement strategy showing how they will manage the transition. Departments complete an assessment tool to demonstrate they are fully capable of managing their procurement activities under the new framework and this informs VGPB's assessment and approval decisions.

VGPB has not defined a formal framework for monitoring the results of transitioning to the new procurement environment. Its guidance on making a submission states that:

'The VGPB may also determine that elements of your submission that will be subject to ongoing assessment or may need to be resubmitted as a result of changes that impact on the structure and/or operation of the organisation.'

Conclusions

For advisory engagements, the combined efforts of departments, as accountable managers, and VGPB and DTF, in their oversight capacities, have not delivered on the VGPB requirement that:

'Government and public officials must be able to demonstrate high levels of integrity in processes while pursuing value-for-money outcomes...'.

We found very few cases in our sampled engagements where agencies had clearly ignored or broken the mandatory rules governing advisory engagements. Instead the lack of assurance resulted from maladministration—where for the most part departments did not apply processes in a way that was structured, documented and transparent to the sampled engagements.

This shortfall meant departments did not generate the information needed to effectively oversee these engagements. There are significant gaps in the way individual departments and DTF, in its whole-of-government role, oversee these engagements.

Procurement reform is an opportunity for departments to transform how they approach procurement and address the issues raised in this report about advisory engagements.

Findings

Planning, procuring, managing and evaluating engagements

In the context of this audit the indicators of maladministration are:

- the absence of a structured and documented approach to management

- the lack of adequate post-engagement evaluation to verify the outcomes and to understand and embed the lessons learned.

While the departments we reviewed largely followed VGPB's specific, mandated requirements for engagements of their size and complexity, the documentary evidence falls well short of demonstrating that these engagements achieved value for money.

Departments could not adequately and consistently demonstrate that engagements were:

- well planned—they did not document the essential planning work used to justify the use of external resources, identify and manage risks, and choose a preferred procurement approach

- effectively procured—they had not adequately assessed the overall impact of exemptions, the way they used panel appointments requiring only one bidder and the use of variations on value for money

- well managed—they could not show how they had monitored progress and performance and appropriately managed risks

- comprehensively evaluated—there was a systemic failure to evaluate performance to confirm they had achieved the intended value-for-money outcomes or to distil and apply the lessons learned.

In addition, a small number of engagements are unlikely to have achieved value for money because of materialising risks that were not well assessed and managed.

Oversight

There are significant gaps in the way individual departments and DTF, in its whole‑of‑government role, oversee procurement. Procurement reform offers the opportunity for individual departments to transform their approach to procurement and address the issues raised in this report.

Departments largely managed engagements on a case-by-case basis without the type of intelligence gathering, analysis and leadership needed to drive significant improvements. They had not effectively captured and analysed agency-wide information about the conduct of advisory engagements in a way that would help them to identify trends, monitor risks and improve value-for-money outcomes.

In terms of central oversight, DTF needs to raise the level of assurance it provides to government about correctly classifying and fully disclosing consultancies, and it also needs to take a more structured and evidence-based approach to verifying the consultancy savings claimed by departments.

We note that DTF has committed to review and analyse departments' consultancy expenditure to ensure expenses are correctly reported.

Impact of procurement reform

The early evidence suggests that procurement reform is an opportunity for departments to transform the way they govern and manage procurement, and address the weaknesses identified in this report.

Our initial review of DTF's progress shows very promising signs, with evidence of upgraded processes, intelligence gathering and analysis underpinning improved procurement practices and oversight.

This transition marks a significant improvement in DTF's approach to procurement. We have examined the revised documentation and examples of DTF's analysis. We have seen some early benefits, and if the implementation happens as intended, this approach is likely to address identified weaknesses in process and oversight.

The other departments in this audit have a similar opportunity to transform their approach to procurement and the early signs are that they intend to do this. However, we are concerned at the absence of a formal process across government to evaluate the impacts of procurement reform, address emerging issues and reinforce demonstrated benefits. VGPB needs to define how it will monitor impacts and report back to government.

We intend to come back to this area to determine whether departments subsequently realise this opportunity for improved oversight and performance.

Recommendations

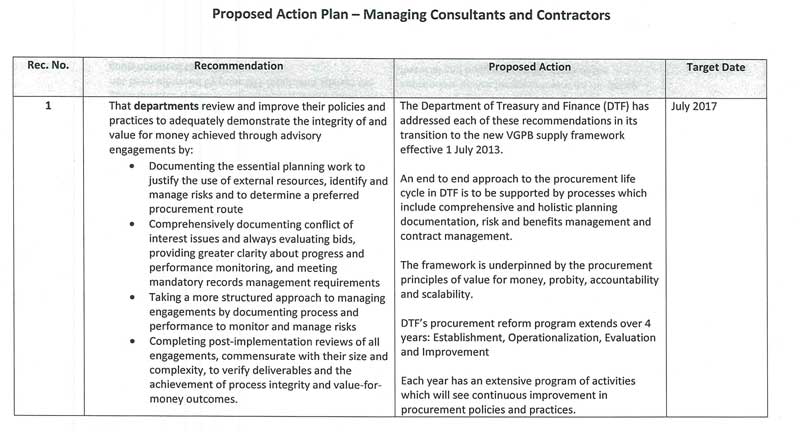

That departments:

- review and improve their policies and practices to adequately demonstrate the integrity of and value for money achieved through advisory engagements by:

- documenting the essential planning work to justify the use of external resources, to identify and manage risks, and to determine a preferred procurement route

- comprehensively documenting conflict of interest issues and always evaluating bids, providing greater clarity about progress and performance monitoring, and meeting mandatory records management requirements

- taking a more structured approach to managing engagements by documenting progress and performance to monitor and manage risks

- completing post-implementation reviews of all engagements, commensurate with their size and complexity, to verify deliverables and the achievement of process integrity and value‑for‑money outcomes

- collect and analyse the information needed to confirm that business units are complying with mandated policies and practices, and manage the risks to achieving value for money and maintaining process integrity.

That the Victorian Government Purchasing Board:

- updates its guidance to more clearly explain departments' records management obligations and how these should be incorporated in contracts

- defines how it will monitor, evaluate and report on the impacts of procurement reform and the actions needed to address emerging issues and reinforce beneficial outcomes.

That the Department of Treasury and Finance:

- describes in its response to this recommendation the steps it will take to verify the accuracy of departments' classification and reporting of consultancy expenditure

- as a matter of standard practice, verifies the basis of government's financial commitments, where these have not been informed by prior Department of Treasury and Finance input, and advises the government of the implications

- better understands and verifies the evidential basis for departments' assertions about the Better Financial Management policy savings achieved

- reviews users' satisfaction with the performance of the Contracts Publishing System website and upgrades the website to provide more effective and user‑friendly access to the contract information it contains.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Treasury and Finance, Department of Justice, Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, Department of Environment and Primary Industries, and Victorian Government Purchasing Board with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix B.

1 Background

1.1 Scope and significance of external advice

Public sector agencies engage external resources to advise them on how best to realise government policy and to help them implement it. From July 2013, the Department of Treasury and Finance's (DTF) revised definitions make the provision of advice to facilitate decision-making the distinguishing feature of a consultancy, whereas a contractor helps implement decisions.

This audit examines how effectively selected government departments are managing these advisory engagements that help them make decisions.

Our planning work for this audit revealed that advisory engagements had not been consistently classified in the past because of the way DTF's Financial Reporting Directions defined consultants and contractors. Accordingly, the scope of the audit includes both consultancy and contractor engagements that inform decision-making.

There is no consolidated record across government of spending on advisory engagements but expenditure is likely to be significant. The 2011–12 annual reports for 65 of the 289 state entities within the general government sector declared consultancy expenditures of $49.5 million, with government departments accounting for $4.1 million of this total.

These figures are unlikely to be a good guide to the amount spent on advisory engagements. Under the definition that applied before July 2013, agencies did not have to classify all advisory engagements as consultancies. For example, an engagement to perform a one-off task to facilitate decision-making would only be classified as a consultancy if the agency judged that it involved 'skills and perspectives which would not normally be expected to reside in the department'.

The new definition from July 2013 provides greater clarity by focusing on the provision of expert analysis or advice to facilitate decision-making without the need to judge whether the skills should or should not normally reside in the department. This is likely to increase the number of advisory engagements classified as consultancies.

Expenditure on advisory engagements is a relatively small proportion of the $16.5 billion of operating expenses budgeted in 2013–14 by the general government sector. While individual advisory engagements are relatively small and are almost always under $1 million, they are critical in fully informing decisions that involve much larger sums of money. As with any expenditure of public monies, it is important that departments are able to demonstrate value for money and the integrity of these procurements.

1.2 Policies and guidance—advisory engagements

This section explains:

- the framework that governs departments when engaging external advisors

- how the Better Financial Management policy changed this framework after 2010

- how procurement reform aims to transition departments by August 2014 to a framework where they take greater responsibility for procurement as a core business function.

1.2.1 Framework for governing advisory engagements

The framework comprises:

- principles and supply policies set by the Victorian Government Purchasing Board (VGPB), under section 54L of the Financial Management Act 1994 (the Act)

- two of the Minister for Finance's directions, made under section 8 of the Act

- responsibilities for monitoring and reporting on agencies' compliance.

VGPB's procurement framework

VGPB's goals are to lead government's procurement of goods and services. They also aim to deliver value-for-money outcomes, with integrity, by setting mandatory purchasing principles and supply policies, and by providing guidelines and advice.

VGPB's policies govern the procurement of non-construction goods and services for 289 state entities, including all nine government departments.

Departmental purchasing must be based on the following principles:

- value for money—taking full account of quality, the total cost of ownership, fitness for purpose and risk in making procurement decisions

- open and fair competition—providing opportunities that enable more businesses to compete on the same basis for government contracts

- accountability—ensuring that accountable officers have the flexibility and capability to achieve value-for-money outcomes

- probity and transparency—applying the highest standards of behaviour to protect the integrity of procurements

- risk management—continuously identifying, evaluating and appropriately treating risks that threaten the achievement of these principles.

Figure 1A summarises VGPB's current supply policy requirements for planning, tendering, and awarding and managing contracts. Overall—according to the Conduct of Commercial Engagements Policy—'Government and public officials must be able to demonstrate high levels of integrity in processes while pursuing value-for-money outcomes'.

VGPB's existing supply policies place more onerous and specific requirements on procurements that are valued in excess of $10 million and for other procurements considered high risk or complex. For the most part, advisory engagements do not fall into this high-value, high-complexity category and are therefore not subject to the more onerous requirements.

Figure 1A

Victorian Government Purchasing Board requirements

| Supply policy requirements | |

|---|---|

| Planning | |

| Planning intent

Planning the purchasing process from start to finish is essential for all procurements. This includes:

|

Planning requirements

All procurements will:

For procurements over $10 million and/or that are high risk or complex, departments will develop:

|

| Bid process and contract award | |

| Intent

Bids and award processes must adhere to VGPB's five procurement principles so that:

|

Bid process requirements

Departments must:

Contract evaluation and award requirements Contract managers must:

|

| Contract management | |

Intent The processes, structure and resources to manage the contract should be identified during planning, where the degree of management depends on the contract complexity and assessed risk levels. |

Contract management requirements

Departments must:

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Victorian Government Purchasing Board supply policies.

Minister for Finance's directions covering procurement

The Minister for Finance has issued two directions under section 8 of the Act that reinforce VGPB's supply policies:

- Standing Direction 3.4.5 provides that departments must implement effective internal controls so procurement is authorised in accordance with business needs and within a framework of policies and procedures based on VGPB's key principles

- Financial Reporting Direction 22—Standard Disclosures in the Report of Operations—includes consultancy disclosure requirements. We note that the information requirements of VGPB's consultancy register are more extensive and detailed than the material that needs to be disclosed under this direction.

Compliance, reporting and monitoring responsibilities

The primary accountability for complying with VGPB's policies and the Minister for Finance's directions rests with individual agencies, and for this audit, with the four departments being examined.

To give assurance that they are following requirements, departments provide:

- VGPB with an annual supply report summarising procurement activity, exemptions and any breaches of VGPB policies

- DTF with a certification that includes a tick box confirmation that procurement policies are based on each of VGPB's procurement principles.

VGPB and DTF are responsible for monitoring and reporting on compliance with respect to procurement. They review, collate and consolidate the reported material so that the Minister for Finance can inform Parliament about whether appropriate controls are in place across the Victorian public service.

DTF's monitoring responsibilities extend beyond procurement to cover all directions set under the Act. DTF supplements agencies' assertions with sampled assurance reviews targeted at areas and agencies it perceives to carry significant risks. To date, DTF has not completed an assurance review around consultancy disclosures.

VAGO's 2012 audit Personal Expense Reimbursement, Travel Expenses and Corporate Credit Cards identified weaknesses in DTF's approach to monitoring and providing assurance to the minister about compliance with purchasing card rules. The audit:

- concluded that 'the mechanisms for assuring government about performance are not working' because five of six agencies 'did not accurately report rule breaches to the Minister for Finance, and DTF did not adequately review this information'

- recommended that, DTF 'significantly improve its scrutiny of agencies' reporting on breaches of the purchasing card rules and reports on thefts and losses' and 'request an acquittal of the scale of contract leakage and the reasons why this happens from agencies participating in a mandatory State Purchase Contract'.

DTF accepted the report's conclusions and recommendations. This audit examined DTF's approach to providing assurance about agencies' compliance with the procurement requirements for advisory engagements.

1.2.2 Applying the Better Financial Management policy

Coalition's Better Financial Management Plan

The Coalition's pre-election Better Financial Management Plan set a savings target of $1.57 billion over the period 2010–11 to 2014–15. It encompassed 11 savings initiatives, including reduced spending on advertising, travel expenses, head office staff, legal bills and consultants.

The plan recognised that consultants had a role in providing impartial and specialist advice but committed to 'end the wasteful use of consultancies and lower the bill for consultants by around $185 million over five years'.

The plan described how many consultancies added little value and that the true value of advisory engagements was hidden from scrutiny because agencies:

- did not have to disclose details of individual consultancies valued under $10 0000

- classified many advisory engagements as 'contractors', thus avoiding the more stringent disclosure rules applied to consultancies.

The Coalition therefore committed to:

- '...issue clear guidelines and definitions on the use of consultants...'

- ensure that 'all consultancies—including those under $100 000—are reported in annual reports'.

Better Financial Management policy

This plan formed the basis of the government's Better Financial Management policy, which retains the specific savings targets set out in the pre-election plan. After the November 2010 election, the newly formed government required DTF to:

- update the consultancy definition and disclosure rules

- advise departments about their allocation of target savings for each of the 11 savings initiatives

- as part of the 2011–12 Budget process, review and refine the allocation of savings and propose a detailed monitoring and reporting framework.

Updating consultancy definition and disclosure rules

Figure A1 in Appendix A provides a detailed description of how DTF changed Financial Reporting Direction 22 to increase the consultancy reporting requirements and set out new consultant and contractor definitions.

The amended July 2013 definitions are likely to change how agencies classify advisory engagements and significantly increase declared expenditures on consultancies. This disclosure should make information on consultancies more publicly accessible.

Managing the implementation of consultancy savings

As part of this audit we examine DTF's performance in tracking and verifying reported progress towards the government's goal of reducing spending on consultancies by $185 million between 2010–11 and 2014–15.

1.2.3 Procurement reform

Current VGPB policies are being replaced under a reform process intended to support a more strategic, flexible and efficient approach to procurement.

VGPB's 'process based' approach will be replaced by a less prescriptive set of high‑level reform policies underpinned by the requirement that all procurement activity applies the following principles—value for money, accountability, probity and scalability. VGPB's definitions of the first three principles are outlined in Section 1.2.1. Scalability has been added and means matching organisational capability and oversight to the complexity and risk of procurement projects. Departments must ensure that all procurement activity meets these principles.

This approach puts a greater onus on a department to decide how best to manage different types of procurement, and to appropriately align its capabilities and oversight across this range of procurement types. VGPB has issued the following five reform policies to guide agencies in developing their own detailed framework:

- governance policy—embedding procurement as a core business function with greater focus on up-front strategic planning and transparency to deliver consistency and better value for money

- complexity and capability assessment policy—understanding the complexity of engagements and ensuring sufficient capability to effectively manage them

- market analysis and review policy—effectively using market intelligence to determine the most appropriate procurement path

- market approach policy—applying a structured, measured approach to informing, evaluating and negotiating with suppliers

- contract management and disclosure policy—focusing consideration early in the planning process to determine an integrated, end-to-end approach.

The transition will give rise to risks and opportunities. Before making the change departments have to secure VGPB's approval of a procurement strategy that shows how they will manage the transition. Departments complete an assessment tool to demonstrate they are fully capable of managing their procurement activities under the new framework, and this informs VGPB's assessment and approval decisions.

VGPB has not defined how it will monitor the results of transitioning to the new procurement environment. In its guidance documentation for making a submission, it states that:

'The VGPB may also determine that elements of your submission that will be subject to ongoing assessment or may need to be resubmitted as a result of changes that impact on the structure and/or operation of the organisation.'

Currently DTF is the only department included in this audit that has transitioned to this new approach, and we describe our early observations on the potential benefits of this in Part 3 of the report.

1.3 Previous audits

Previous audits found a range of common practice deficiencies and also the need for departments to improve their understanding and oversight of advisory procurements if they are to effectively address these issues.

1.3.1 VAGO's contracting and tendering audit

The 2007 audit Contracting and Tendering Practices in Selected Agencies assessed whether 'practices in selected agencies comply with government policy and procedures, and deliver on expected outcomes for the public sector' by examining a sample of 15 contracts. These included mostly larger construction and service delivery contracts of a scale that activated the more detailed VGPB requirements applied to large or complex contracts. Only three were for advisory services.

The audit concluded that while, 'the tendering approach selected, and the tender process, were consistent with procurement policies and guidelines... for nine of the contracts, however, there was scope for improvement in the key procurement stages, of specifying what is to be procured, evaluating the bids, assuring the quality of the procurement process, and monitoring and evaluating contractor performance'. It singled out monitoring and evaluation of performance as the key deficiency.

The audit recommended that agencies clearly specify and monitor performance standards and improve their records management of procurement activities to adequately demonstrate the basis for decisions.

VAGO published the guide Sector Procurement: Turning Principles into Practice based on the good practice principles used to assess engagements during the 2007 audit. We took account of these good practices in forming the approach used in this audit.

1.3.2 Audits from other jurisdictions

The findings of recent audits from the UK and South Africa on the use of consultants are typical of the type of findings found in overseas audits. They raise issues around the incomplete application of processes and a consequent lack of assurance about value for money, but also clearly identify the need for department and government‑wide intelligence and oversight to address these issues.

The Auditor-General of South Africa

The January 2013 Report of the Auditor-General of South Africa on a performance audit of the use of consultants at selected national departments found similar practice issues to VAGO's 2007 audit, where departments did not:

- comprehensively assess needs before engaging consultants, nor adequately plan consultancy engagements

- consistently evaluate the success of engagements and the lessons learned.

In addition, the report found insufficient evidence of how departments had considered the use of internal resources before appointing consultants or effectively transferred the skills and knowledge from engagements.

The UK National Audit Office

The October 2010 audit Central government's use of consultants and interims was the latest in a series of audits on the use of consultants.

The audit found that departments' progress in applying previous recommendations had been slow. Given previously well-defined practice issues, the audit focused on the quality of whole‑of‑department and central government management systems to address these issues, finding that departments:

- have poor quality management information—there was an absence of timely, complete and accurate information to effectively plan and manage the future use of consultants

- are not smart customers—they did not clearly define required services, were unclear how consultants contribute to objectives and did not assess benefits

- have not identified and addressed core skill gaps which would allow them to use more cost-effective alternatives—they repeatedly used consultants for the same basic skills without addressing these needs through improved recruitment

- have not used the knowledge generated from centrally collated information to improve how they use consultants.

The report called for leadership by departments to address these findings and improved central analysis and oversight by the Cabinet Office to drive good practices.

1.4 Audit objective, scope and approach

1.4.1 Objective

The objective of this audit was to assess whether selected departments are effectively managing advisory engagements that inform their decisions by examining how well they are:

- planning, procuring and managing these engagements

- evaluating engagements and demonstrating that they achieve value for money and process integrity.

1.4.2 Scope

The audit examined for the period 2011–12 to 2013–14 the following agencies—Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD), Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI), Department of Justice (DOJ) and DTF. We also examined how well DTF monitors compliance with financial reporting direction requirements for disclosing consultant and contractor spending.

In these departments we selected a sample of 63 advisory engagements for detailed examination, and Figure 1B summarises their characteristics. The selection was designed to cover a range of contract values and types of advice engaged by agencies.

Figure 1B

Details of sample advisory engagements examined during the audit

Department |

Classification |

Range of contract values ($) |

Date for applying reform |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Consultants |

Contractors |

Total |

Lower |

Upper |

||

DEECD |

4 |

12 |

16 |

61 000 |

613 000 |

July 2014 |

DEPI |

6 |

12 |

18 |

49 000 |

355 000 |

July 2014 |

DOJ |

5 |

9 |

14 |

85 000 |

1 610 000 |

August 2014 |

DTF |

5 |

10 |

15 |

12 000 |

650 000 |

June 2013 |

Total |

20 |

43 |

63 |

|||

Note: DTF has completed its application of VGPB reforms.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.4.3 Approach to assessing departments' performance

Demonstrating delivery against VGPB's intended outcomes

Our approach tests whether departments have effectively applied VGPB's overarching requirements for advisory engagements by demonstrating that they have:

- achieved value for money and high levels of integrity through open and fair competition, clear accountability and high standards of probity and transparency

- identified, assessed and effectively managed the risks that threaten to undermine these intended outcomes.

Integrity

The State Services Authority review of Victoria's integrity system explained that 'the public is entitled to expect that public officials will act with integrity' because citizens expect them 'to uphold values such as honesty and truthfulness and to act in the public's interest in performing their duties. Fair, reliable and systematic decision‑making in public services engenders public trust and creates a level playing field...'.

This is consistent with the values set out in section 7 of the Public Administration Act 2004 to guide the conduct and performance of the Victorian public sector.

On Page 3 the review defined a spectrum of behaviour comprising:

- acting with integrity—acting with honesty and transparency, managing resources appropriately and using powers responsibly

- maladministration—where administrative tasks are not performed properly or appropriately, encompassing inefficiency, incompetence and poorly reasoned decision-making

- misconduct—this is more serious than maladministration, involving more than not paying attention or not exercising due diligence, such as breaches of codes of conduct or an element of dishonesty

- corruption—this goes beyond misconduct and involves the misuse of power and the misuse of office, with the term usually applying to serious wrongdoing such as bribery, embezzlement, fraud and extortion.

The audit examined whether agencies could demonstrate how they had acted with integrity in planning, completing and evaluating advisory engagements.

Value for money

VGPB defines value for money from the point where an agency has decided to procure goods or services to meet identified needs. The Achieving value for money procurement guide says:

- 'Value for money (VFM) underpins Victorian Government procurement. It is the achievement of a desired procurement outcome at the best possible price—not necessarily the lowest price—based on a balanced judgement of financial and non-financial factors relevant to the procurement'.

This guide makes it clear that value for money has to be considered and demonstrated throughout the procurement process and after completion when doing a final evaluation of the procurement. This is consistent with existing supply policies.

Demonstrating integrity and value for money

We tested the integrity and value for money by assessing whether departments could demonstrate that engagements were:

- well planned, by:

- justifying the need for external resources

- clearly defining engagement objectives, intended outcomes, staff capability requirements, and the engagement risks and how these should be managed

- justifying the intended procurement approach in terms of the costs and benefits of alternative procurement options and the impacts on encouraging open and fair competition

- effectively procured, by applying tender and appointment processes that:

- clearly align with VGPB's requirements

- are consistent, fair and transparent

- deliver tender outcomes consistent with, or exceeding, the planned value proposition

- well managed, by showing monitoring of progress, tracking of contracted deliverables and appropriately managed engagement risks

- comprehensively evaluated, by:

- completing a post-implementation evaluation confirming the delivery of intended outputs

- measuring performance in terms of the intended outcomes

- applying the lessons learned.

We note that the advisory engagements we examined are unlikely to be classified under VGPB as large or complex. For these types of projects, VGPB's policies define the principles and outcomes without mandating the specific form and content of documentation required for large—greater than $10 million—or complex procurements.

For all advisory engagements, and indeed all procurements, we expect agencies to create and retain sufficient documentation to demonstrate the achievement of VGPB's intended outcomes.

The audit was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of the audit was $470 000.

1.5 Structure of the report

The report has two further parts:

- Part 2 examines how agencies plan, procure, manage and evaluate advisory engagements based on our review of 63 of these engagements

- Part 3 examines department-wide and whole-of-government oversight and reporting, how procurement reform has the potential to improve departments' performance and what departments need to do to realise this potential.

2 Planning, procuring, managing and evaluating

At a glance

Background

Demonstrating process integrity and value for money of advisory engagements requires evidence that engagements are well planned, effectively procured, well managed and comprehensively evaluated.

Conclusion

Departments largely followed the Victorian Government Purchasing Board's (VGPB) specific, mandated requirements for engagements of different sizes and complexity. However, the evidence falls well short of demonstrating that these engagements achieved VGPB's goals of value for money and process integrity.

Instead maladministration—where processes were not properly or appropriately performed—characterised how departments managed the sampled advisory engagements.

Findings

Departments could not demonstrate that advisory engagements were well planned, effectively procured, well managed and comprehensively evaluated.

In addition, a small number of engagements are unlikely to have achieved value for money because of materialising risks that were not well assessed and managed.

Recommendations

- That departments review and improve policies and practices to address procurement weaknesses and adequately demonstrate the integrity and value for money achieved through advisory engagements.

- That VGPB updates its guidance to more clearly explain departments' records management obligations and how these should be incorporated in contracts.

2.1 Introduction

An essential part of good public administration involves applying appropriate processes and documenting the basis for decisions about the expenditure of public funds. The opposite of this is maladministration, where there are process failures and the absence of adequate documentation. While not as serious as misconduct or corruption, maladministration obscures and undermines performance.

We drew on our work within selected departments to determine whether they could demonstrate that engagements had been effectively planned, procured—that is, tendered and appointed—well managed and comprehensively evaluated.

We used these findings to form conclusions on whether departments could adequately demonstrate they had achieved the Victorian Government Purchasing Board's (VGPB) intended outcomes of process integrity and value for money for advisory engagements.

2.2 Conclusion

While the departments we reviewed largely followed VGPB's specific, mandated requirements for engagements of their size and complexity, the documentary evidence falls well short of demonstrating that these engagements achieved value for money.

Departments have not delivered on the VGPB's requirement that, 'Government and public officials must be able to demonstrate high levels of integrity in processes while pursuing value-for-money outcomes...'.

Instead, maladministration characterised how departments managed the sampled advisory engagements—where processes were not properly or appropriately performed.

Departments could not adequately and consistently demonstrate that engagements were:

- well planned—as they did not document the essential planning work used to justify the use of external resources, identify and manage risks, and choose a preferred procurement approach

- effectively procured—as they had not adequately assessed the overall impact of exemptions, the way they used panel appointments requiring only one bidder and the use of variations on value for money

- well managed—as they could not show how they had consistently monitored progress and performance and appropriately managed risks

- comprehensively evaluated—in fact the opposite was true, as there was systemic failure to evaluate performance to confirm that the intended value‑for‑money outcomes had been achieved and to distil and apply the lessons learned.

In addition, a small number of engagements are unlikely to have achieved value for money because of materialising risks that were not well assessed and managed.

These findings are consistent with the internal audit evidence we examined. The Department of Justice's (DOJ) December 2013 internal audit of contractor and consultant performance concluded:

- '...we identified inconsistent contractor and consultant appointment‑to‑completion activity...and inconsistency in the extent and transparency of documentation completed and maintained to justify the activity...'.

The departments we examined had not effectively captured and analysed agency-wide information about the conduct of advisory engagements in a way that would help them to identify trends, monitor risks and improve value-for-money outcomes.

In Part 3 of the report we describe how procurement reform offers the opportunity to address these issues. Departments need to seize this opportunity to revamp their processes and realise the significant potential benefits of doing this.

2.3 Planning

Thorough planning is essential if departments are to create a solid foundation for adequately informing procurement decisions and delivering value for money by:

- clearly establishing the business need

- carefully considering the internal and external options for meeting this need

- developing an evidence-based strategy to recommend a preferred procurement option, taking account of the costs, benefits and risks of alternative options

- doing the preparatory work needed to effectively engage the market and match appropriate internal resources to the procurement's risk and complexity.

The four departments reviewed did not adequately document engagement planning. While our interviews with contract managers partly addressed this gap by, for example, explaining the reasons for using external resources, we found limited supporting evidence of the depth and consistency required.

The absence of a comprehensive and transparent approach is significant because we are not assured that departments have adequately:

- considered the use of internal resources

- prepared for engagements by fully assessing potential risks and documenting the basis for a preferred approach that best addresses these.

2.3.1 Establishing the need for external advice

We found little documentary evidence of establishing the need for external advice in advance of going to the market with a request for tender, or of making a compelling case for engaging external resources to meet this need. Contract managers explained that they engaged external advisers to:

- access specialist skills or knowledge not residing in the department

- get an independent or objective assessment, even when skills resided internally

- supplement skills that resided in the department but which were unavailable.

These interviews did not assure us that departments routinely and consistently assessed the availability of suitable internal resources to meet these needs.

For engagements under $100 000, the DOJ 2013 internal audit found:

- a lack of evidence of a systematic approach to assessing whether departmental resources could meet needs that were put to the market

- the absence of departmental guidance about how to assess this capability.

2.3.2 Adequately preparing for the engagement

The VGPB's policies encourage departments to properly prepare for a potential engagement before going to the market. In addition to deciding whether to engage external resources, this preparatory work should clearly document departments' understanding of:

- the need for external advice, the engagement objectives and the expected deliverables

- the expected cost of the advice and the departmental resources needed to effectively manage the engagement, given its scale and complexity

- how the engagement should be managed,including identifying, assessing and working out how to treat risks and setting up a clear and appropriate structure for managing the contract.

The documentation we reviewed did not meet these requirements for all departments.

Figure 2A summarises the planning requirements applied by the audited departments, together with VAGO's assessment of the gaps in documentation.

While there were occasional examples of good practice for parts of the planning process, none of the documentation fully conveyed essential planning information and in all cases there were substantial gaps. This represents a missed opportunity to identify, assess and start to manage risks that are likely to threaten the engagement's objectives. The worst consequences are seen for a small number of engagements where materialising risks seriously undermined their value for money.

Finally, departments did not consistently identify, assess and describe how they intended to manage engagement risks.

Departments need to improve the comprehensiveness and clarity of their engagement planning and document this as the foundation for their preferred procurement approach and the effective management of engagements through to delivery.

2.3.3 Benefits of improved planning and documentation

A rigorous and documented approach is likely to better identify and manage key risks, provide greater assurance about planning decisions and identify where resource gaps could be cost-effectively addressed over time through recruitment and training.

Figure 2A

Departments' approach to engagement planning

|

Number of |

Departmental planning requirements |

VAGO assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Education and Early Childhood Development | ||

|

16 |

All contracts should:

|

None of the 16 engagements adequately documented engagement planning:

There was no risk register or procurement plan for the 10 projects over $150 000, although three had risk analyses in charters. |

| Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI) | ||

|

18 |

For all procurement over $500 000:

|

None of the 18 engagements adequately documented the engagement planning:

|

| Department of Justice | ||

|

14 |

For all contracts:

For all consultancies:

|

None of the 14 engagements adequately documented engagement planning. All five consultancies completed consultancy engagement approval forms:

For the remaining nine contractors, DOJ has been unable to provide planning documentation. |

| Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) | ||

|

15 |

Prior to July 2013, no formal planning requirements. Since July 2013, for all engagements over $10 000:

|

Our review of DTF contracts found the same lack of comprehensive planning up to July 2013. DTF upgraded its processes in July 2013 as part of its transition to a reformed approach. These processes are more extensive and significantly improved, but their recent addition means their application is not yet able to be tested. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

2.4 Procuring—tender and appointment

Tender and appointment processes must adhere to VGPB's principles of value for money, open and fair competition, clear accountability, probity and transparency, and the effective management of risks. Departments need to demonstrate that bidders have been given the same fair opportunity to compete and that engagements are awarded on the basis of value for money.

We found that departments largely complied with VGPB's requirements, although this section also describes areas where they fell short and need to act.

However, VGPB's specific minimum requirements for procurements of this scale and complexity are not sufficient to demonstrate that departments achieved value for money through the tender and appointment processes.

Departments need to do more to extract additional value from these engagements and provide greater assurance about their value for money by extending practices beyond VGPB's requirements and better monitoring their application.

2.4.1 Where departments fell short of VGPB requirements

Departments largely met VGPB's requirements for panel arrangements, where these applied, and by either seeking the number of bids consistent with an engagement's expected value or seeking an appropriately authorised exemption.

However, we found two areas where departments clearly fell short of the requirements:

- firstly, for 40 of the 63 engagements departments failed to complete and retain conflict of interest forms for engagement assessors

- secondly, there were 17 cases where departments received a single quotation but did not assess it against evaluation criteria.

In addition, we found a further three isolated examples of engagements that had breached other VGPB requirements.

Conflict of interest documentation

The one recurring area where agencies inconsistently applied requirements is in assessors completing conflict of interest forms. Across departments we found:

- documented declarations for 23 engagements

- no documented declarations for 40engagements.

One of these examples of missing documentation involved an engagement without the required documentation that was inherited following a machinery-of-government change.

Departments were unable to provide declarations for the remaining 39 engagements or explain their absence.

Evaluating single bids

VGPB supply policy advises that 'All offers must be evaluated in a consistent manner against the evaluation criteria adopted for the tender', and the VGPB Conduct of Commercial Engagements good practice guidelines note that, 'It is critical to apply the evaluation criteria consistently and transparently to all tenderers and to all tenders'.

We found 24 engagements where departments appointed based on a single, written quotation. This occurred where an exemption from seeking three quotes or public tender was obtained from the Accredited Purchasing Unit (APU), or when the proposed engagement had an expected value of less than $25 000. For 17 of these, departments did not document an assessment of the submission against its procurement criteria—eight of these 17 engagements were for sums in excess of $150 000.

VGPB advised that departments must evaluate all bids—including single bids—to confirm that they meet departments' minimum requirements.

Figure 2B describes a Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) advisory engagement that was legitimately appointed through a single quotation under a panel arrangement but without evaluating the adequacy of the bid.

Figure 2B

DEECD—absence of adequate planning and evaluation of a single bid

|

Risks around inadequate planning and diminished value for money |

|

|---|---|

|

Description |

Implications |

|

DEECD used an internal research panel to directly engage a contractor for a $548 900 research project. |

|

Source:Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

2.4.4 Specific examples of noncompliance with VGPB policies

Aside from the conflict of interest declarations, we found three engagements that did not meet VGPB's requirements—these are described in Figure 2C.

Figure 2C

Specific examples of noncompliance with VGPB policies

|

DOJ variation without approval |

|

|---|---|

|

Description |

Implications |

|

|

|

DTF potential contract splitting |

|

|

Description |

Implications |

|

|

|

DEECD commencing an engagement before gaining appropriate approvals |

|

|

Description |

Implications |

|

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

2.4.5 Practice and oversight improvement opportunities

Departments should improve their practices by:

- better monitoring how they use exemptions and panels, and understanding the potential impacts of these practices on value for money

- reviewing how they deal with single bids for engagements over $25 000

- standardising tender evaluation and reporting processes

- providing greater clarity about progress monitoring

- identifying and securing access to records that are of value to departments.

Using panel arrangements and exemptions

Figure 2D describes VGPB's supply policies for using whole-of-government or departmental panels and exemptions from normal competitive processes.

For 33 of the 63 engagements, departments used these mechanisms and followed VGPB's rules for securing the required authorisations. However, we have not seen evidence that departments monitored trends in the use of exemptions and panels, and increased cross-departmental scrutiny is likely to be required.

For example, understanding the incidence of and rationale for inviting single panel quotes, or for exempting procurements from competition, will provide the information needed to test and continuously improve value for money.

Figure 2D

VGPB supply policies—panel arrangements and exemptions

| Panel arrangements |

|---|

|

There are two broad types of panel arrangement:

Both of these typically:

The departmental arrangements we examined further reduce the transaction costs by allowing a higher threshold than the normal VGPB rules before requiring multiple quotes. However, contract managers are able to invite multiple quotes below the minimum level if they think the benefits outweigh the additional costs. Panels set up to secure advisory services provide easier and less costly access to quality tested resources invited to compete for entry on to the panel. |

| Exemptions |

|

Under VGPB's supply policies, departments can seek an exemption from normal competitive processes and quotation thresholds where these may not be the optimal sourcing strategy. They do this by satisfying the appropriate financial delegate, based on the expected value of the contract, that the exemption:

The policy describes a non-exhaustive list of exemption factors including:

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Victorian Government Purchasing Board supply policies.

Use of panel arrangements

Eighteen engagements, with an average value of $231 800, were contracted using whole-of-government or departmental panels. Departments used single bidder quotations to appoint contractors to eight of these engagements. The final value of these direct appointments ranged from a DTF engagement for $59 600 to a DEECD engagement for $548 900 involving a company updating an earlier modelling exercise.

We are not assured that departments adequately compared the additional costs of going beyond a single panel quotation with the potential benefits of the increased competitive tension of inviting multiple bids.

When a single quote is accepted because of a bidder's specialist expertise or knowledge, departments need to assess and mitigate the risk that the engagement will consolidate a single bidder's hold on future work.

Use of exemptions

Figure 2E shows that 15 of 63 sampled engagements were subject to an exemption, with four of these avoiding a public tender but still being required to obtain a minimum of three bids and the remaining 11 exempt from any competition.

Figure 2E

Exemptions from VGPB's default competition rules

|

Department |

Exemptions from |

Total number of exemptions |

Total number of engagements |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Public tender (>$150 000) |

Three quotes (>$25 000) |

Public tender/ three quotes |

|||

|

DEECD |

1 |

0 |

2 |

3 |

16 |

|

DEPI |

0 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

18 |

|

DOJ |

3 |

1 |

3 |

7 |

14 |

|

DTF |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

15 |

|

Total |

4 |

4 |

7 |

15 |

63 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The average value of these engagements was $285 870, with four valued under and the remaining 11 valued over $150 000. Agencies usually cited more than one reason for these exemptions. Needing to meet tight deadlines and a contractor's unique expertise or prior knowledge was used to explain about half of the exemptions. In four cases agencies justified exemptions based on the confidential nature of engagements.

Departments need a cross-organisation appreciation of the incidence, frequency and type of all exemptions granted. They should regularly analyse this information to understand exemption trends and characteristics and conduct appropriate testing to confirm that exemptions do not lessen competitive tension and value for money.

Single bids for engagements over $25 000

We found a small number of non-panel and non-exempt engagements where departments made appointments for over $25 000 based on single bids, including:

- three cases where a department sought three bids but received only one, subsequently accepting these single bids for between $49 000 and $300 000

- one case where departments requested a single written quote, expecting the cost to be less than $25 000, but appointed for a sum in excess of $25 000.

VGPB has clarified that these examples do not contravene its supply policies.

Departments are required to seek—not obtain—three written quotations for engagements between $25 000 and $150 000.

For the second case, VGPB advised that if a quotation exceeded the one quote threshold by a small amount it would not expect a department to start a new procurement process. However, a significant excess of the threshold should be accompanied by a rigorous appraisal of the case for a new, three quotation process. The recommendation and approval should take account of the value for money and integrity impacts.

Figure 2F shows an example where DTF appointed to an $88 000 advisory engagement based on a single bid without adequate documentation underpinning the decision to do this.

Figure 2F

DTF—informal and inadequate appointment process

| DTF advisory engagement based on single bid | |

|---|---|

|

Description |

Implications |

|

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Standardising tender evaluation and reporting approaches

We found diverse approaches to documenting the same type of tender evaluations even within the same department. These varied between evaluations that provided combined assessment panel scores as the sole basis for making an appointment, to evaluations providing a much fuller description of relative strengths and weaknesses, panel member scores and a clearly stated rationale for the recommended appointment.

Greater clarity around progress and performance monitoring

We found variable and inconsistent contractual requirements defining how departments would monitor progress and performance. We deal with this and its impacts under Section 2.5 on engagement management.

Records management requirements

Neither the contracts reviewed, nor VGPB's 2013 contract templates and guidance, fully address the mandatory records management requirements defined by the Public Records Office of Victoria (PROV).

VGPB needs to update its guidance to more clearly explain departments' records management obligations and how these should be incorporated in contracts. VGPB has indicated it will liaise with PROV to ensure that both VGPB and PROV guidance and templates are sufficiently clear as to the applicability of PROV standards to advisory engagements.

While departments routinely identified deliverables such as draft and final reports, they did not adequately address how the full set of records generated by the engagement should be managed. This exposes departments to risks that:

- the record of their activities will fall short of legislative requirements

- they will not realise the full benefits because they have not secured access to valuable information created through these advisory engagements

- the state may be exposed to difficulties in accessing records where this is disputed by consultants and contractors

- consultants and contractors may use the records created through government engagements for their own commercial benefit without any reference to the state.

Legislated requirements

PROV's Specification 1—Strategic Management states that, 'Contracts, agreements or legislative instruments for outsourcing or privatisation must specify records management and monitoring practices that meet government and legislative records management requirements'. We note that the VGPB webpage 'Contract Management Step 6' references PROV's non-mandatory guideline Managing Records of Outsourced Activity, but does not reference the strategic management specification, which is mandatory.

Figure 2G summarises departments' obligations for managing records from outsourced arrangements, including advisory engagements.

Engagement contracts

While contracts typically include clauses to establish the ownership of records created as a result of the engagement, we did not find sufficient detail covering the security of and access to the full records of the engagement.

For example, arrangements did not:

- clearly identify the underlying data and analysis supporting engagements' deliverables

- describe how this information would be preserved

- explain how departments could access and reuse this information.

As well as raising legislative compliance issues, this gap has the potential to reduce the value of these engagements by:

- making it difficult for departments to access and use valuable information for other purposes

- reducing the level of competition for follow-on work because access to records generated under previous engagements has not been well managed.

Figure 2G

Public Records Office of Victoria records management requirements

|

Requirement Number |

Description |

|---|---|

|

21 |

Ownership and custody of records of outsourced or privatised activities is determined and documented in the legal documents that govern the relationship with contracted service providers or privatised entities. |

|

22 |

Contracted service providers and privatised entities must be required to comply with records management requirements determined by the agency. |

|

23 |

Records of outsourced or privatised activities must only be disposed of in accordance with the Public Records Act 1973 and other relevant legislation. |

|

24 |

The same level of access to records of outsourced or privatised activities must be available to the public regardless of who is delivering the service. |

|

25 |

The contractual or legislative arrangements must specify appropriate standards of storage for any records of outsourced or privatised activities which are not in government custody. |

|

26 |

The contractual or legislative arrangements must specify appropriate standards of security for any records of outsourced or privatised activities which are not in government custody. |

|

27 |

Arrangements for monitoring and audit of contracted service provider or privatised entity records management practices are agreed and specified. |

|

28 |

Outstanding records management issues, including disposal, must be addressed by contracted service providers prior to the completion of the contract. |

|

29 |

The agency must ensure that the total budget for a contract includes sufficient resources to fund the cost of the record-keeping requirements specified in the contract. |

Source: Public Records Office of Victoria's strategic management specification.

VGPB's latest contract templates

VGPB's templates for departments embed practices that address PROV's requirements in the way they plan for and contract advisory engagements. One department raised this issue with us during the audit conduct.

We asked VGPB to confirm that the templates covering the provision of services took PROV's requirements into account, and specifically asked how the nine requirements in Figure 2G had been integrated within these contracts.

VGPB responded that:

- the new templates are a baseline, to which departments can incorporate additional clauses depending on the complexity of the outsourced arrangement

- the Victorian Government Solicitor's Office confirmed that the templates are sufficiently robust to be legally defensible in court.

The evidence offered has not provided sufficient assurance that VGPB's current guidelines and contract templates are sufficient to guide departments in meeting their records management obligations for advisory engagements. VGPB's planned consultation with PROV provides the opportunity to address this issue.

2.5 Managing engagements

There is insufficient documentary evidence to assure us that departments have applied a structured and effective approach to managing advisory engagements in terms of monitoring progress and performance and managing risks.

2.5.1 Monitoring progress and performance

The approach to monitoring progress and performance against engagements' objectives is inconsistent, and for the most part not adequately documented. Except for a few isolated examples of better practice, departments did not document an adequate plan for measuring progress and, for the most part, did not document key interactions between contract managers and consultants.

Our interviews with contract managers showed they relied on general contract provisions about producing specified deliverables and they informally checked on progress. They consistently advised us that they tracked progress and performance through informal discussions.

We found little evidence of performance measures or benchmarks being developed and applied to engagements, irrespective of their relative cost, size or complexity.

2.5.2 Managing risks

Our findings were similar when we assessed how departments managed engagement risks. Except for a small number of engagements, this was informal with no clear assessment of the risks and no structured approach to monitoring and managing risks during engagements.

We did not see how departments applied the formal frameworks they make reference to throughout the term of engagements. Contract managers frequently referred to their informal or non-documented management of emerging risks, but it is very difficult to gain assurance about the effectiveness of this type of approach.

This level of ongoing monitoring and oversight is insufficient to adequately manage the potential risks that threaten effective performance. The absence of a structured, documented approach to monitoring does not adequately address the risks that would flow from a contract dispute and is unlikely to systematically identify and proactively deal with emerging risks.

Figure 2H describes the material consequences from inadequate risk management for:

- a DTF advisory engagement to review a major commercial transaction

- two DEPI engagements where shortfalls in planning and risk management led to substantial variations that are likely to have diminished value for money.

Figure 2H

Examples of inadequate risk management

|

DTF engagement to advise on a commercial transaction |

|

|---|---|

|

Description |

Implications |

|

|

|

DEPI examples of inadequate planning, risk management and subsequent extensive variations |

|

|

Description |

Implications |

|

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

2.5.3 Actions to address this

Departments need to better define progress and performance measures and their approach to managing risk, and better record their contract management actions.

Applying a structured, scalable and documented approach to managing engagements of different sizes and complexities does not necessarily require more resources, but it will require more discipline in following well-designed minimum requirements and documenting the outcomes.

This will bring greater rigour and consistency to how departments manage these engagements and make it possible for departments to monitor and improve practices across business units.

2.6 Evaluating and learning from engagements

As documented in our 2012 publication Reflections on audits 2006–2012: Lessons from the past, challenges for the future, VAGO's audits since 2006 have found that agencies are frequently unable to clearly demonstrate how well they have performed. In this context, post-implementation reviews are essential to verify the value for money and integrity of advisory engagements and to learn from procurements and continuously improve.

Our conclusions on this type of activity are clear—VGPB's supply policies do not mandate this and none of the departments completed post-implementation reviews.