Managing Regulator Performance in the Health Portfolio

Overview

Regulation is a key instrument used by government to achieve its social, economic and environmental goals. To be effective, regulation requires a well-targeted and evidence-based approach which efficiently achieves government’s intended outcomes while minimising the burden placed on businesses.

Recent reviews have identified the absence of an effective risk-based approach to regulation as a significant weakness in the current system.

This audit assessed how well four selected regulators, the Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) in its portfolio oversight role, and the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) in its whole-of-government role, have contributed to improved regulatory performance in the health portfolio.

We found that regulatory practices within the health portfolio are at a low level of maturity because:

- regulators have not taken a systematic, risk-based approach and do not fully understand the impact of their regulatory activities

- DHHS has not effectively overseen and supported health regulators

- DTF has not applied government's Statement of Expectations policy in a way that has helped address these gaps and weaknesses.

DHHS has committed to developing and implementing a regulatory reform strategy, and it is important that this work proceeds because, if done well, it will help improve performance in the medium to long term.

We recommend that health portfolio regulators address the specific weaknesses identified in this audit, that DHHS develop and implement a strategy for the effective oversight of portfolio regulators and that DTF improves how it develops, supports and evaluates regulatory reform programs.

Managing Regulator Performance in the Health Portfolio: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER March 2015

PP No 23, Session 2014–15

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Managing Regulator Performance in the Health Portfolio.

The audit examined how well the selected regulators, the Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) in its portfolio oversight role, and the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) in its whole-of-government role, have contributed to improved regulatory performance in the health portfolio.

We found that regulatory practices within the health portfolio are at a low level of maturity because:

- regulators have not taken a systematic, risk-based approach and do not fully understand the impact of their regulatory activities

- DHHS has not effectively overseen and supported health portfolio regulators

- DTF has not applied the government's Statements of Expectations policy in a way that has helped address these gaps and weaknesses.

The recommendations are designed to address these shortfalls. Health portfolio regulators need to improve their performance by addressing the specific weaknesses identified in the audit but progress will be severely limited without more effective oversight and support from DHHS and DTF to help them do this.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

18 March 2015

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Ray Winn and Kate Kuring—Engagement Leaders Nerillee Miller—Team Leader Louise Gelling, Ronan McCabe and Celinda Estallo—Analysts Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Andrew Evans |

Over the past five years, my office has focused attention on the performance of some of the state's largest regulators because of their critical role in protecting the environment, keeping workers safe, sustaining healthy fisheries, guarding consumers' rights and maintaining safe food and dairy products.

Regulation provides important protections to Victorians. But it can also be challenging because administering regulation can be costly and has the potential to burden businesses with requirements that can dampen productivity and affect economic growth.

Getting this balance right and addressing risks is at the heart of good regulation. A good regulator has to be clear about the regulatory outcomes that it is meant to achieve, the costs and effectiveness of its activities and the burden it imposes on the businesses it regulates so that it can effectively and efficiently manage the risks that might undermine intended outcomes.

To date, the results of my audits of regulators have been mixed. They have shown that departments and the regulators they oversee are at varying and mostly lower levels of maturity in applying better practice risk-based regulation. For example, in 2012 we concluded that the former departments of Primary Industries and Sustainability and Environment did not have comprehensive, risk-based approaches to managing their considerable compliance responsibilities.

But some regulators have worked hard to develop better approaches. For example, in 2011 we reported that the Environment Protection Agency's (EPA) regulation of contaminated sites had been ineffective. However, three years later our 2014 audit on Managing Landfills found that the EPA had developed a better practice risk‑based approach to regulating this area. This illustrates the progress that can be made in developing and applying risk-based approaches to improve regulatory outcomes.

This audit focused on regulation in the health portfolio—comprising 14 regulators, which by virtue of their size have not received the same level of scrutiny as, for example, large environmental regulators. I examined four health regulators in detail that are responsible for Victorian pharmacies, radiation safety, drugs and poisons, and pest control operators.

I found that the four health portfolio regulators are a considerable way off applying the type of systematic, risk-based approach that is required to significantly improve regulatory outcomes. Instead, they are mainly focused on the day-to-day application of the regulations they oversee and do not adequately understand the costs and effectiveness of their activities or the burden imposed on the parties they regulate.

Unlike large regulators that are likely to have more resources to develop and apply a risk-based approach, the smaller health regulators we examined need more help to lift their performance. This help should come in the form of the Department of Health & Human Services' (DHHS) oversight and support to its regulators and the Department of Treasury and Finance's (DTF) leadership and management of the Government's Statement of Expectations policy.

To date these departments have not effectively played their part in lifting the practices and performance of health regulators. DHHS oversight and support has not been effective because until recently it had not started to develop a coherent whole-of-department approach to supporting and overseeing its regulators. DTF's approach to implementing government policy may work with larger, more mature regulators in departments that have a structured approach to oversight and support, but is unlikely to connect with the type of regulators included in this audit.

My recommendations are designed to address these shortfalls. Health portfolio regulators need to improve their performance, but progress will be severely limited without more effective oversight and support from DHHS and DTF. The lessons from this audit are likely to have clear and relevant application to others and I urge all departments and their regulators to consider whether they are doing all that they can to improve their regulatory performance.

I want to thank the staff from the DHHS, DTF and the Victorian Pharmacy Authority who worked with the team on this audit.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

March 2015

Audit Summary

Background

Regulations have a significant role in the Victorian economy. They are a key instrument used by government to achieve its social, economic and environmental goals by directly influencing how private firms and not-for-profit organisations do business. Regulation is meant to effectively protect the community and the environment while allowing regulated businesses and professionals to prosper.

Effective regulation requires a well-targeted and evidence-based approach, which efficiently achieves government's intended outcomes while minimising the burden placed on businesses. Poorly designed and applied regulation risks overburdening businesses and depressing economic growth.

Between 2011 and 2014 two Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission inquiries and several VAGO audits identified significant weaknesses in the current system. Central to these criticisms was the absence of an effective risk-based approach to regulation. Such an approach would apply a systematic framework to prioritise regulatory activities and to deploy resources using an evidence-based risk assessment.

In response, government created policy goals focused on reducing the burden that regulators impose on businesses, while improving regulators' effectiveness and reducing their cost base.

To achieve meaningful change, government required departments and regulators to provide responses to ministerial Statements of Expectations (SOE) establishing performance expectations. This was a two-stage process:

- Stage 1 applied to five of the state's largest regulators—Consumer Affairs Victoria, Environment Protection Authority, Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation, VicRoads and WorkSafe Victoria. These SOEs described how these agencies would reduce the red tape burden on regulated businesses by 25 per cent by July 2014.

- Stage 2 SOEs applied to all departments and their regulators and required them to improve regulatory outcomes across a range of areas that constitute good regulatory practice, including by developing more risk‐based and targeted approaches.

In terms of responsibilities:

- regulators are responsible for achieving their objectives efficiently while minimising the burden imposed on the organisations they regulate

- departments oversee the performance of portfolio regulations and advise ministers about how to improve regulators' performance

- the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) advises on how to achieve policy goals, guides and supports implementation, and reports on outcomes.

This audit focuses on regulation within the health portfolio. The Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) has 14 regulators administering 36 pieces of legislation. While health regulators do not rate among the largest in the state in terms of expenditure or staff, they cover areas that are of critical importance to the community and government.

In this audit we focused on Stage 2 of the government's SOE policy because it applied to all regulators, including those in the health portfolio. We formed criteria for assessing performance based on a risk-based approach to regulation. While the application of risk-based practices was one of eight good regulatory practices included in the SOE Stage 2 framework, we found these criteria covered all the essential elements of good regulatory practice.

The objective of the audit was to assess how well the selected regulators, DHHS in its portfolio oversight role, and DTF in its whole-of-government role, have contributed to improved regulatory performance in the health portfolio.

This audit was commenced assessing the Department of Health. On 1 January 2015, machinery-of-government changes took effect and the responsibilities of the former Department of Health transferred to DHHS.

The audit examined in detail:

- three departmental regulators—Radiation Safety, Pest Control, and Drugs and Poisons Regulation

- one statutory authority—Victorian Pharmacy Authority.

Conclusion

Regulatory practices within the health portfolio are at a low level of maturity because:

- regulators have not taken a systematic, risk-based approach and do not fully understand the impact of their regulatory activities

- DHHS has not effectively overseen and supported health portfolio regulators

- DTF has not applied government's SOE policy in a way that has helped address these gaps and weaknesses.

Findings

Health regulators

The four health regulators examined have not systematically applied a risk-based approach to regulation and do not fully understand the impact of their regulatory activities. There is insufficient evidence to show that these regulators have applied a structured approach to managing and prioritising risks, and this compromises their ability to demonstrate that regulatory outcomes have been achieved and the regulatory burden reduced.

Our assessment found that the health regulators are focused on the day-to-day delivery of their legislative responsibilities. Though we identified some instances of good practice, each of the regulators we audited has some distance to travel before they reach maturity and achieve better practice in administering and enforcing regulation.

The good practices we identified arose where regulators identified opportunities for improvement to specific practices. However, major weaknesses exist around:

- linking objectives to outcomes

- stakeholder engagement

- performance measurement and reporting.

The greatest potential for sustained improvement lies in regulators taking a strategic approach to adopting better practice. Doing so will have the greatest long-term impact on efficiently achieving regulatory outcomes.

There is significant scope for regulators to enhance the planning and delivery of their activities, while improving efficiency and effectiveness, and relieving regulated parties from the regulatory burden associated with compliance.

The Department of Health & Human Services—the portfolio department

To date DHHS has not helped health regulators address the weaknesses we identified in this audit.

Each regulator is accountable to senior executives and the Minister for Health through internal structures and processes. However, a lack of central monitoring across all regulators means there is no line of sight enabling DHHS to understand whether regulators are adopting efficient, risk-based approaches to regulation.

It also means DHHS has little opportunity to identify where separate regulators' practices reflect better practice approaches, or to capitalise on opportunities for improvement in accordance with government's broader regulatory reform agenda.

DHHS has a clear role to play in this regard. While we found instances of collaboration occurring between regulators, this was not part of a strategic approach by DHHS to coordinate and integrate regulatory activity.

DHHS has committed to developing and implementing a regulatory reform strategy for health portfolio regulators, but progress has been slow and it is unclear what reforms will take place and when they will be implemented.

It is important that the work to reform DHHS' approach to regulation proceeds because, if done well, it will help improve performance in the medium to long term. This reform takes on even greater significance with the combination of health and human services' regulators into a single portfolio department.

The Department of Treasury and Finance

In 2014, the Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission identified integration as a key opportunity for improving Victoria's regulatory system. It highlighted that fragmentation of the regulatory system undermines the capacity of regulators to adopt more efficient and effective practices, and weakens accountability. The Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission also noted a number of barriers to better integration of the regulatory system, including legislative impediments to information sharing and cultural impediments, such as regulators questioning the costs and benefits of collaboration.

DTF has a critical part to play in overcoming these barriers, especially where departmental oversight is not well developed.

For DHHS and the health portfolio regulators, DTF has not effectively managed the implementation of government's Stage 2 SOE policy for health regulators, and this has contributed to inadequate health portfolio SOEs.

DTF's recommended approach to implementing this policy included proactive support up to the point of implementation. For the implementation, DTF allowed a four-month time line, flexibility in how departments and regulators responded to the policy and a reactive rather than proactive approach to review and support. Government approved this.

However, DTF's advice did not adequately convey the risks this approach presented to achieving government's objectives. The risks of not having sufficient time nor the support needed to develop adequate SOEs are relevant for the health portfolio, where departmental oversight is ineffective, and where regulators are not experienced in applying risk-based regulation.

In addition, DTF did not adequately define how the responses to SOEs written by departments and regulators would be evaluated to measure intended outcomes. Our repeated experience in past VAGO audits is that the absence of a fit-for-purpose evaluation framework at the start of the process undermines performance measurement.

Recommendations

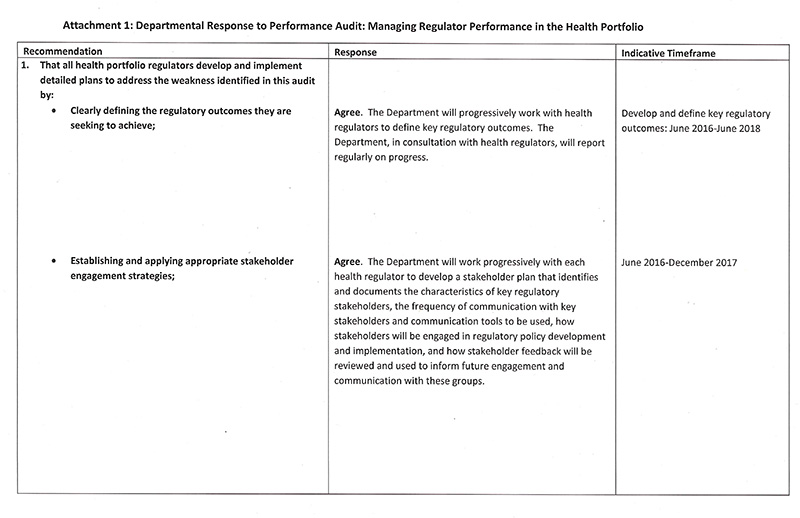

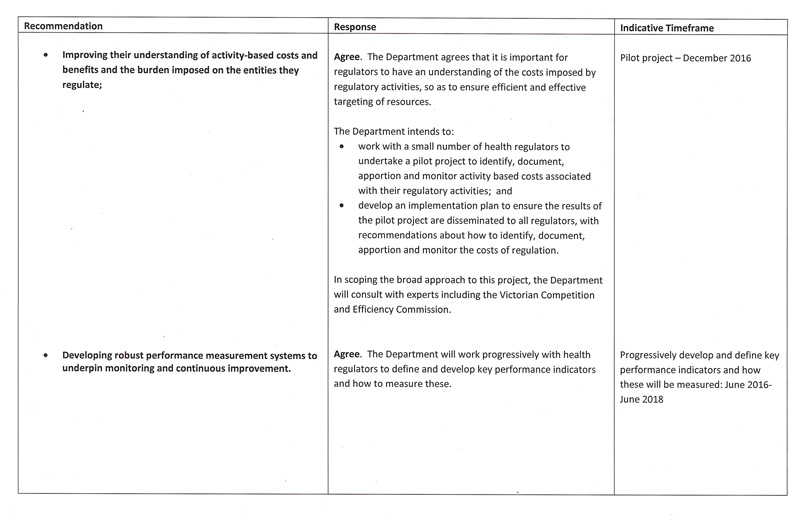

- That all health portfolio regulators develop and implement detailed plans to address the weaknesses identified in this audit by:

- clearly defining the regulatory outcomes they are seeking to achieve

- establishing and applying appropriate stakeholder engagement strategies

- improving their understanding of activity-based costs and benefits and the burden imposed on the entities they regulate

- developing robust performance measurement systems to underpin monitoring and continuous improvement.

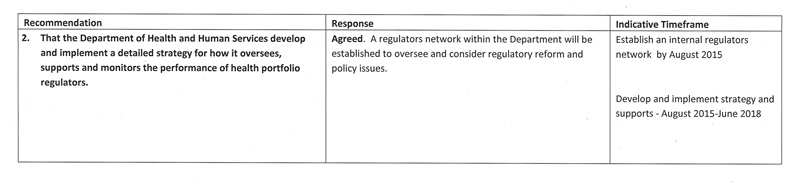

- That the Department of Health & Human Services develops and implements a detailed strategy for how it oversees, supports and monitors the performance of health portfolio regulators.

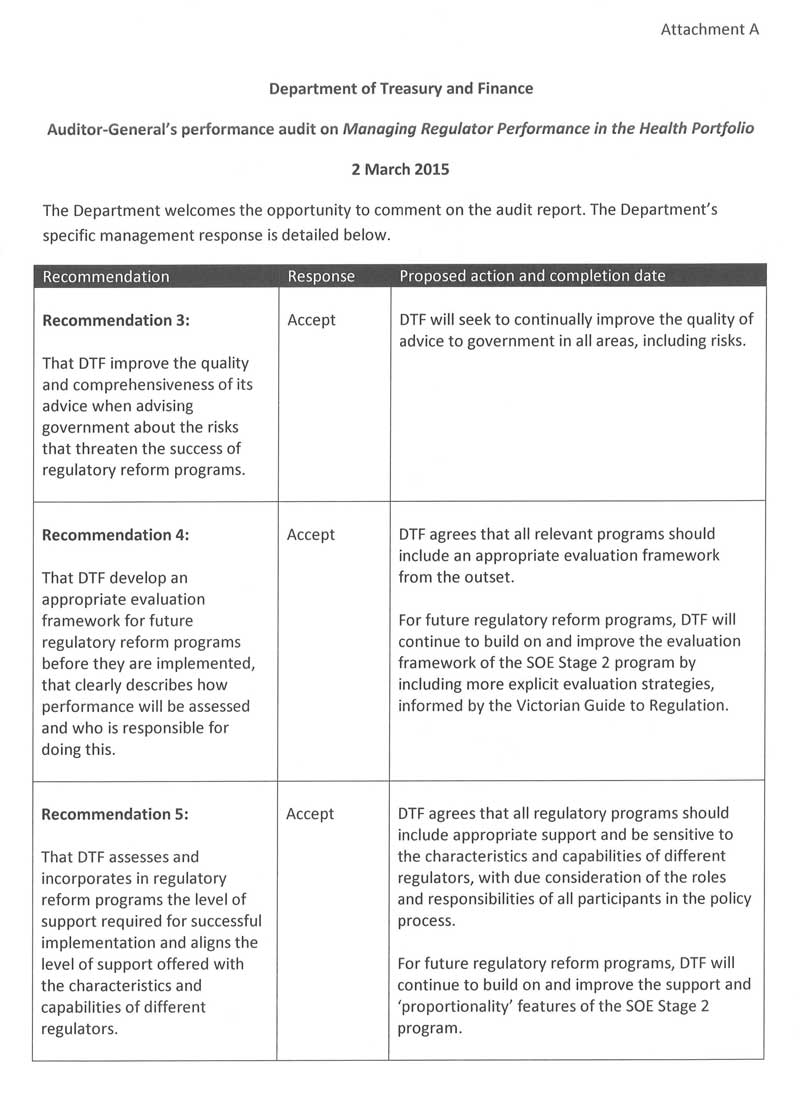

- That the Department of Treasury and Finance improves the quality and comprehensiveness of its advice to government about the risks that threaten the success of regulatory reform programs.

- That the Department of Treasury and Finance develops an appropriate evaluation framework for future regulatory reform programs, before they are implemented, that clearly describes how performance will be assessed and who is responsible for doing this.

- That the Department of Treasury and Finance assesses and incorporates in regulatory reform programs the level of support required for successful implementation and aligns the level of support offered with the characteristics and capabilities of different regulators.

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with the Department of Treasury and Finance, the Department of Health & Human Services—including the audited regulators within the department—and the Victorian Pharmacy Authority throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report to those agencies and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix B.

1 Background

1.1 Regulation in Victoria

1.1.1 The purpose of regulation

Regulations have a significant role in the Victorian economy. They are a key instrument used by government to achieve its social, economic and environmental goals by directly influencing how private firms and not-for-profit organisations do business. Regulation is meant to effectively protect the community and the environment while allowing individuals and businesses to prosper.

Achieving this requires a well-targeted and evidence-based approach that accomplishes government's intended outcomes in a way that efficiently uses the available resources while minimising the burden placed on businesses. Poorly designed and applied regulation risks achieving little and depressing economic growth because of the burden placed on businesses and professionals.

1.1.2 Regulators in Victoria

There are currently 58 entities in Victoria regulating businesses and organisations, with diverse responsibilities, ranging from ensuring that the food and water we consume is safe, to making sure that architects, plumbers and surveyors are appropriately qualified. Regulators acquit their responsibilities through education, inspection, monitoring and enforcement.

Collectively, Victorian regulators administer 171 different pieces of legislation, a further 191 regulations and around 2.9 million licences. To carry out this work they employ over 7 000 staff, have an annual expenditure of around $1.3 billion and recoup around $575 million through fees. The 14 largest Victorian regulators account for around 70 per cent of that total expenditure, and employ 59 per cent of the staff.

Two-thirds of Victoria's regulators are established as statutory bodies through legislation. The remaining third administer regulatory responsibilities from within government departments.

1.1.3 Weaknesses in the current system of regulation

Recent inquiries by VCEC and audits by VAGO identified significant weaknesses in the current system.

Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission reports

In 2011, VCEC found Victoria's overarching regulatory framework compared favourably with other Australian jurisdictions, but also 'identified deficiencies that, taken together imply that the system is operating well below its potential'. Victoria's framework is some way from being a best practice regime, with examples of:

- the need for regulation not being rigorously tested

- a lack of assurance that regulation is effective and efficient

- the ongoing need for and impacts of regulation not being systematically evaluated.

It concluded that there was considerable scope to improve outcomes and efficiency and to better address cases where an excessive burden had been placed on businesses.

In July 2014 VCEC reported on a further review that aimed to identify efficiency savings of at least $30 million per year from four of the state's largest regulators. This review also identified how long-term performance could be improved by:

- better integrating regulators to simplify the regulatory system

- adopting more risk-based approaches to administering regulation

- strengthening incentives to regulators to operate efficiently and effectively

- developing generic and consistent efficiency indicators

- reforming unnecessary or excessive internal red tape.

This report also proposed a framework for performance reporting, focusing on risk‑based regulation, stakeholder experience, and cost-effectiveness, as these are an essential foundation for understanding regulator performance. The government is yet to respond to VCEC's review.

Recent VAGO reports

VAGO's recent audits of Recreational Maritime Safety (2013–14), Effectiveness of Compliance Activities: Departments of Primary Industries and Sustainability and Environment (2012–13), Consumer Protection (2012–13), Managing Contaminated Sites (2011–12) and Compliance with Building Permits (2011–12) identified:

- a failure on the part of regulators to demonstrate how they achieve legislative objectives, and to measure, monitor and report on their performance

- a lack of whole-of-organisation, risk-based approaches to managing regulatory and compliance responsibilities

- poor coordination between individual regulators and a lack of effective departmental oversight of regulators within their portfolios.

1.2 Government policy and programs

Government's policy goals have focused on addressing these issues by reducing the burden that regulators impose on businesses, while improving regulators' effectiveness and efficiency.

To further these goals government took several steps:

- Government used responses to ministerial Statements of Expectations (SOE) to establish agreement between portfolio ministers and regulators about actions for reducing the regulatory burden and improving outcomes, as detailed in Figure1A:

- In Stage 1, five large regulators described how they would reduce the red tape burden on regulated businesses by 25 per cent, by July 2014.

- In Stage 2, SOEs required the state's regulators to describe how they would improve regulatory outcomes, including by developing more risk‐based, proportionate and targeted approaches to regulation. Responses were required by July 2014 with the achievement of intended outcomes set for July 2016.

- The 2011 red tape reduction program applied to all the state's regulators, and was run in parallel with the Stage 1 SOE process, aiming to cut regulatory costs to business by 25 per cent, or $715 million, by July 2014.

- VCEC was commissioned to identify $30 million of efficiency savings from four large regulators and to propose a framework for measuring regulator performance. VCEC submitted its report to government in July 2014, including proposals for $50 million in efficiency savings. Government is considering its response.

Figure 1A

The Statement of Expectations framework

|

Stage 1 |

|

|---|---|

|

Applicable to |

Consumer Affairs Victoria, Environment Protection Authority, Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation, VicRoads, WorkSafe Victoria. |

|

Focus |

Driving efficiencies in regulators' high-impact or high-volume compliance activities, such as approvals, inspections and business reporting requirements. |

|

Process |

Departments and regulators agree to performance measures for reducing the impact these activities have on business, with the aim of achieving government's goal of a 25 per cent reduction in red tape by July 2014. |

|

Time frames |

SOEs issued by ministers to regulators by March 2013. |

|

Stage 2 |

|

|

Applicable to |

All state regulators—but not mandatory—41 of 58 regulators responded to SOEs and five regulators were exempted from the process by portfolio ministers. |

|

Focus |

Governance—role clarity, cooperation with other regulators, stakeholder engagement, accountability and transparency. Performance—risk-based regulation, timeliness of processes and effectiveness of compliance-related activities. |

|

Time frame |

SOEs issued to regulators by December 2013. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.3 Agencies' regulation responsibilities

The agencies that have a role to play in moving regulators towards better practice and addressing government policy goals are clear from the government's response to VCEC's 2011 inquiry.

The Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) is:

- responsible for advising the Treasurer on the government's SOE policy and guidelines

- responsible for the whole-of-government coordination of, and reporting on, regulation reform including the government's red tape reduction program

- responsible for playing a coordinating role across government in relation to improving performance

- available to support regulators and departments in developing SOEs, including by advising them on the consistency of draft SOEs with the SOE guidelines.

Departments are responsible for:

- advising portfolio ministers about achieving red tape reduction and ensuring that the regulation they administer achieves its objectives with the lowest possible burden being imposed on businesses and professionals

- overseeing and managing the regulators they directly control to improve performance including developing SOEs in consultation with regulators, submitting them to ministers to finalise and issuing them to regulators for their responses

- understanding the performance of regulators in their portfolios and supporting them to improve performance and achieve government's policy goals.

Individual regulators are responsible for:

- achieving their objectives efficiently, while understanding and minimising the burden imposed on the organisations they regulate

- meeting their SOE obligations and publicly reporting on progress.

1.4 The importance of risk-based regulation

Effective application of a risk-based approach to regulation aligns with and is critical to achieving government's policy goals.

Risk-based regulation is the application of a systematic framework that prioritises regulatory activities and the deployment of regulators' resources on an evidence-based assessment of risk. It places risk assessment, quantification and monitoring at the heart of regulation and has the potential to create greater efficiency and effectiveness.

Successfully applying this demands clarity about a regulator's intended outcomes and an evidence-based approach founded on identifying, understanding and appropriately treating the risks that threaten these outcomes.

Under a risk-based regulatory approach, decisions on if and how a risk should be treated, depend on the collection of relevant data, the expected outcomes, the cost of regulation and the burden imposed on businesses. The continuous and meaningful evaluation of effectiveness and efficiency is critical to using this information to drive further improvements.

1.5 Regulation in the health portfolio

This audit focuses on regulation within the health portfolio. The audit was commenced under the Department of Health. On 1 January 2015, machinery-of-government changes took effect and the responsibilities of the former Department of Health transferred to the Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS). We consistently refer to DHHS in the remainder of this report.

DHHS is responsible for 14 regulators administering 36 pieces of legislation—half of which also have associated regulations.

1.5.1 Overview of health portfolio regulators

Figure 1B lists the key features of the regulators in the health portfolio, and shows which are established as units of DHHS, and which are statutory authorities.

While health regulators do not rate among the largest in the state in terms of expenditure or staff, they cover areas that are of critical importance to the community and government. For example, health regulators are responsible for administering legislation covering the safety of drinking water, the standards of care people receive in supported residential care services and for addressing the harm associated with the misuse of drugs and poisons.

Figure 1B

Key features of health portfolio regulators, 2011–12

|

Regulator |

Staff |

Regulated parties |

Expenditure |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Regulators embedded in DHHS |

|||

|

Communicable Disease Prevention and Control Unit |

Not supplied |

Not supplied |

Not supplied |

|

Cooling Towers and Warm Water Systems |

6.6 |

3 491 |

0.6 |

|

Drugs and Poisons Regulation Group |

20.0 |

1 364 |

2.2 |

|

Food Safety Group |

23.1 |

78 |

4.1 |

|

Pest Control Operators |

1.6 |

1 211 |

0.2 |

|

Private Hospitals Non-Emergency Patient Transport |

5.0 |

164 |

<1.0 |

|

Public Swimming Pools and Spa Baths |

1.0 |

NA |

<0.1 |

|

Safe Drinking Water |

4.0 |

85 |

1.0 |

|

Tobacco Policy |

NA |

NA |

1.1 |

|

Radiation Safety |

14.9 |

13 633 |

1.4 |

|

Supported Residential Services |

20.0 |

164 |

3.0 |

|

Statutory authorities |

|||

|

Health Services Commissioner |

21.4 |

NA |

2.3 |

|

Victorian Assisted Reproductive Treatment Authority |

4.8 |

5.3 |

0.8 |

|

Victorian Pharmacy Authority |

8.0 |

>2 000 |

1.0 |

Note: Victorian Assisted Reproductive Treatment Authority and Victorian Pharmacy Authority data is for 2013–14.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on Victorian Regulatory System September 2013, Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission and annual reports.

1.5.2 Regulators examined in detail

The audit examined in detail:

- three departmental regulators—Radiation Safety, Pest Control, and Drugs and Poisons Regulation

- onestatutory authority—Victorian Pharmacy Authority.

These regulators adequately represent DHHS' regulatory activities while excluding regulators undergoing legislative changes.

Radiation Safety

Radiation Safety administers the Radiation Act 2005 and the Radiation Regulations 2007 on behalf of the Secretary of DHHS. It regulates radiation practices and individuals authorised to use radiation sources in order to protect worker health, public health, and the environment from the harmful effects of radiation. It is also responsible for preparing for, and responding to, emergency radiation incidents.

Radiation Safety regulates by licensing medical, dental, veterinary, industrial, educational, and research entities that use radiation sources.

It shares licensing, registration and database management resources with two other health regulators—Pest Control and Cooling Tower Systems—which together form the Environmental Health Regulation and Compliance section of DHHS.

Pest Control

Pest Control administers sections of the Public Health and Wellbeing Act 2008 and the Public Health and Wellbeing Regulations 2009.

Pest Control is responsible for licensing pest-control operators in order to protect them, as well as consumers, members of the public, and the environment, from the harmful effects of pesticides.

Drugs and Poisons Regulation

Drugs and Poisons Regulation administers the Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Act 1981, Therapeutic Goods (Victoria) Act 2010, the Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Regulations 2006, and the Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances (Commonwealth Standard) Regulations 2011.

It is responsible for protecting public health and safety by preventing accidental and deliberate poisoning, medicinal misadventure, and the diversion or theft of drugs for the manufacture or direct use as substances for abuse.

Drugs and Poisons Regulation regulates the orderly sale, supply, prescription, administration and use of drugs, poisons and controlled substances. It also prescribes licence and permit fees.

Victorian Pharmacy Authority

The Victorian Pharmacy Authority (VPA) is an industry-funded statutory authority responsible for administering the Pharmacy Regulation Act 2010 which provides for the regulation of pharmacy businesses, pharmacy departments in hospitals and health services, and pharmacy depots.

VPA aims to support a safe pharmacy system that is responsive to community needs and interests. Specific activities that VPA is responsible for include:

- licensing a person to run a pharmacy business or a pharmacy department

- registering the premises of a pharmacy business, pharmacy department or pharmacy depot

- issuing standards in relation to the operation of pharmacy businesses, pharmacy departments and pharmacy depots

- advising the Minister for Health on any matters relating to its functions and providing information upon request

- keeping a public register of pharmacy premises and owners.

1.6 Audit objective and scope

The focus of this audit was on regulation in the health portfolio, examining how effectively and efficiently a sample of small but important health regulators, DHHS and DTF are working to improve regulatory performance.

The audit assessed progress towards achieving the government's goals of improving regulator effectiveness and efficiency and reducing the red tape they impose on those they regulate, by examining whether:

- selected health regulators have used available resources to efficiently achieve intended outcomes while reducing the red tape they impose on regulated businesses and professionals

- DHHS has effectively overseen the regulators in the health portfolio, supported them in addressing government's policy goals and advised the minister on the regulator performance

- DTF has adequately acquitted its responsibilities in relation to SOE policy and guidelines, supporting regulators and departments in developing SOEs, and coordinating and reporting on whole-of-government regulatory reform.

1.7 Audit method and cost

The audit involved:

- the review of publicly-available information

- the examination of documents provided by agencies

- consultation with staff at the audited agencies.

The audit was conducted in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The cost of the audit was $430 000.

1.8 Structure of the report

The report is structured in three further parts:

2 Regulators in the health portfolio

At a glance

Background

Regulators in the health portfolio have diverse areas of responsibility. We looked at whether Drugs and Poisons Regulation, Pest Control, Radiation Safety and the Victorian Pharmacy Authority are efficiently achieving their intended outcomes while reducing the red tape they impose.

Conclusion

The four health regulators examined in this audit have not systematically taken a risk-based approach to their regulatory obligations and do not fully understand the impact of their regulatory activities. They cannot demonstrate that regulatory outcomes are being achieved, or that they are reducing the regulatory burden. We found some instances of good practice, but significant progress is needed for these regulators to reach maturity in better-practice regulation.

Findings

- Major weaknesses exist around linking objectives to outcomes, stakeholder engagement, and performance measurement and reporting.

- There are encouraging instances of good practice at each of the regulators we examined. However, they have not been developed as part of a thorough strategic approach and there is no comprehensive collaboration with other regulators.

Recommendation

That all health portfolio regulators develop and implement detailed plans to address the weaknesses identified in this audit by defining the outcomes they are seeking to achieve, establishing stakeholder engagement strategies, understanding the costs, benefits and burdens they impose, and effectively measuring performance.

2.1 Introduction

We examined how well four of the regulators in the health portfolio—Drugs and Poisons Regulation, Pest Control, Radiation Safety and the Victorian Pharmacy Authority (VPA)—had achieved their regulatory objectives and whether this was done in a way that was efficient and reduced the red tape burden imposed on businesses.

We specifically tested this by assessing how regulators had applied better practice, risk-based approaches to regulation by examining whether they had:

- established the context for regulation by defining clear objectives and outcomes

- a good understanding of the costs of their activities and the burden imposed on regulated organisations

- prioritised their activities based on a good understanding of the regulatory risks

- engaged stakeholders critical to their success

- collaborated with other regulators to improve performance

- adequately measured and reported on their performance.

2.2 Conclusion

The four health portfolio regulators examined in this audit have not systematically developed risk-based approaches to their regulatory obligations, nor established processes to fully understand the impact of their activities on those they regulate. This compromises their ability to demonstrate that regulatory outcomes have been achieved and the regulatory burden reduced.

These regulators are focused on the day-to-day delivery of their legislative responsibilities. Though we found some instances of good practice, each of the regulators we audited has some distance to travel before they reach maturity and achieve better practice in administering and enforcing regulation.

The good practices we identified arose where regulators identified opportunities for improvement to specific practices. However, the greatest potential for sustained improvement lies in regulators taking a strategic approach to adopting better practice. Doing so will have the greatest long-term impact on efficiently achieving regulatory outcomes.

There is significant scope for regulators to enhance the planning and delivery of their activities, while improving efficiency and effectiveness, and relieving regulated parties from the burden of compliance.

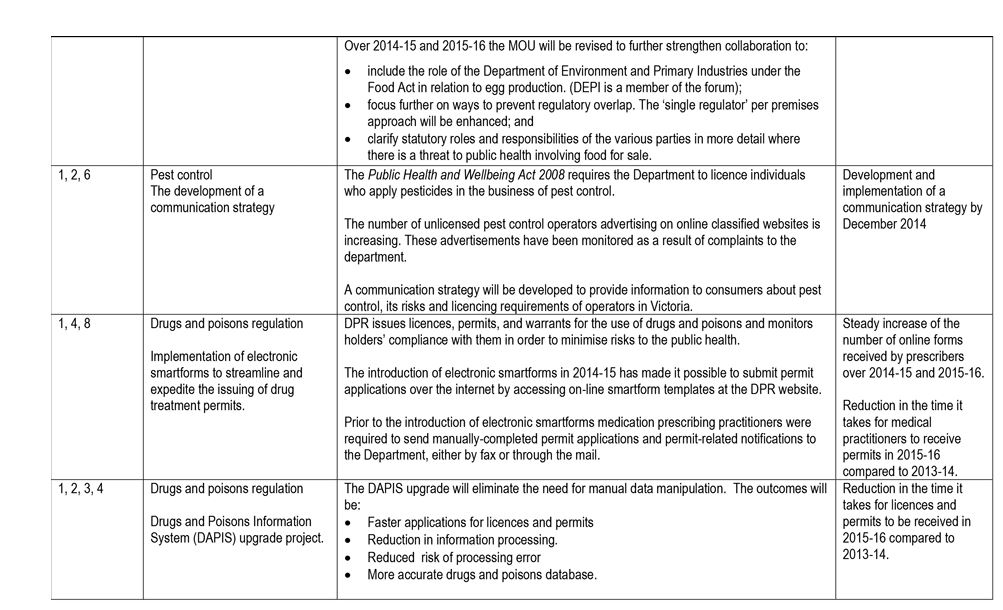

2.3 Overall assessment of selected regulators

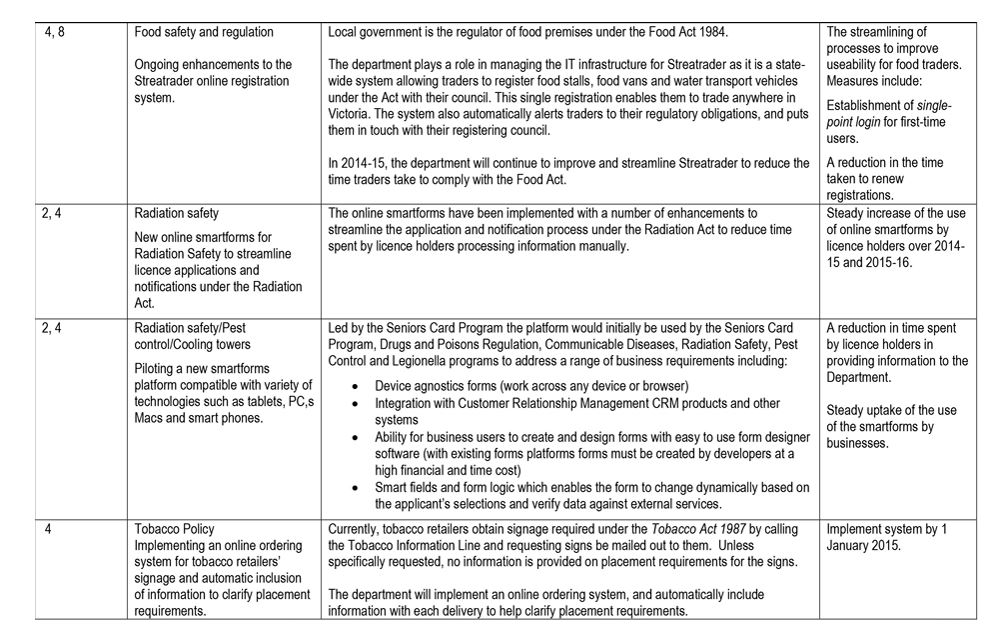

Figure 2A shows a summary assessment of each regulator's performance against the core elements of risk-based approach to regulation. The four regulators recognised that they had some way to go in achieving a mature risk-based approach to regulation.

The four regulators:

- partly meet the requirement to collaborate with other regulators

- partly meet requirements about establishing the context, and understanding their costs and the burden they impose on organisations

- clearly do not meet the remaining requirements about setting risk-based priorities, effectively engaging stakeholders and measuring and reporting on performance.

Figure 2A

Summary of regulator performance against best practice

Drugs and Poisons Regulation |

Radiation Safety |

Pest Control |

Victorian Pharmacy Authority |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Establishing the context: |

~ |

~ |

~ |

✔ |

|

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

Understanding costs, benefits and burdens |

~ |

~ |

~ |

~ |

Comprehensive risk-based prioritisation |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

~ |

Stakeholder engagement and consultation |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

~ |

Collaboration between regulators |

~ |

~ |

~ |

~ |

Performance measurement and reporting |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

Note: ✔ = met; ✘ = not met; ~ = partly met

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on review of documents provided by health regulators.

2.3.1 Establishing the context

Establishing clear objectives and linking these to well-defined and measurable outcomes is essential if regulators are to be effective. This type of clarity reduces the potential for duplication or conflict between functions, and establishes a framework against which the regulator can be held accountable for its performance.

Each of the four regulators examined clearly documented their regulatory objectives. However, the three regulators embedded in the Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) had not defined or documented their intended outcomes. Only VPA could demonstrate the link between its objectives and outcomes—its strategic plan clearly sets out the relationship between its regulatory functions, the achievement of goals, and their contribution to the intended outcomes.

Both Radiation Safety and Pest Control provided evidence that they had identified the expected outcomes of their activities through regulatory impact statements written in 2007 and 2009 respectively. While this indicates that these matters were considered when the regulations were reviewed, there is no evidence that they have been embedded into the agencies' own governance processes or been reported on.

2.3.2 Understanding costs, benefits and burdens

In deciding how best to use their available resources regulators need to understand how much their activities cost, the burden and costs imposed on regulated organisations, and the contribution of these activities to achieving their objectives.

The health regulators understood and tracked their overall costs but could not show that they had a detailed understanding of the burden imposed, or the impact different activities had on the achievement of their objectives. While there are practical challenges in addressing these shortfalls, an improved understanding of activity-related costs and benefits, and the regulatory burden, is achievable and will improve regulators decision-making and transparency.

Regulators' costs

Regulators demonstrated a broad understanding of operational costs. This was strongest at VPA, which produces monthly financial reports and audited financial statements. For health portfolio regulators, overall regulatory staff costs are set out in regulatory impact statements.

However, these costs are not regularly refreshed and we found no breakdown of costs by specific regulatory activities, such as educational activities, processing a licence or carrying out an inspection. Regulators explained that this absence reflects the practical challenges of costing specific activities. For example, separating staff and overhead costs between activities such as education, inspections and compliance monitoring, can be difficult where an inspection visit might relate to all three activities.

We do not accept these challenges as justifying the lack of effort and progress in this area. Commercial companies face the same challenges in disaggregating costs and in estimating the benefits of specific activities. However, doing this while understanding the limitations of the estimates is essential for continually improving effectiveness and efficiency.

Regulatory burden

Regulators were unable to quantify the burden imposed on regulated parties, such as the additional staff and costs of compliance and any efficiency impacts on businesses, for example from delayed decisions.

Regulators have not devoted sufficient effort to measuring and understanding this burden.

While each of the regulators considered these additional costs to be minimal and to be part of the general cost of doing business, none could provide documentary evidence to support these assertions. Again, there are challenges in measuring this burden. Organisations are often regulated by multiple agencies making it difficult to isolate the compliance costs relating to a single regulator.

Impact of activities on outcomes—the benefits

Fully informed decisions require regulators to understand how their activities have or are likely to contribute to intended outcomes.

Regulators have not articulated these linkages because they found this difficult to do. The impact of multiple regulators with overlapping responsibilities and legislation make it difficult to estimate the benefits arising from the activities of a single regulator.

Developing an improved understanding

Agencies need to improve their detailed understanding of the costs and benefits of their activities and the specific burdens they impose on regulated organisations. We acknowledge the practical challenges, but see the potential for improved effectiveness and efficiency by targeting effort to these areas.

Regulators need to estimate the cost and impact of key activities and programs and they need to research their impact on the organisations they regulate.

2.3.3 Comprehensive risk-based prioritisation

A robust risk-based approach to regulation requires regulators to:

- identify risks that pose a threat to achieving regulatory objectives

- assess the consequences and likelihood of these risks occurring

- prioritise regulatory activities to treat the most significant risks

- monitor and report on the implementation of treatments and their impacts on targeted risks and adjust strategies in response to this information.

There is insufficient evidence to show that regulators have applied a structured approach to understanding and prioritising the treatment of the risks preventing them from achieving their regulatory objectives.

None of the regulators included in the audit could demonstrate that they had appropriately prioritised their risks. They provided examples of how their knowledge of risks influenced their prioritisation of day-to-day regulatory activities:

- The VPA targets their resources to inspect premises following a change of ownership, maintains a list of inspection comments that should trigger a fuller review and re-inspects pharmacies where breaches require a panel hearing.

- Radiation Safety bases its inspections on a 2008 risk assessment of radiation sources. However, the regulator could not show us evidence verifying the use of this survey to target inspections.

Prioritising regulatory activities on the basis of a working knowledge of risks does not provide the same level of assurance as a structured and disciplined approach to managing regulatory risks.

VPA had the most advanced, structured approach to risk management. It has documented a policy that defines the objectives of its risk management process and establishes key responsibilities. It also maintains a risk database. However, VPA's focus is on organisational risks—such as occupational health and safety, or data security—rather than the risks that threaten regulatory outcomes. VPA has committed to improving its approach to address these issues.

2.3.4 Stakeholder engagement and consultation

Effectively engaging the stakeholders that frame regulators' performance expectations and that are affected by regulatory activities is critical to a regulator's success. These stakeholders include:

- the government, which sets the legislative and policy context

- DHHS, which supports regulators and monitors their performance

- the Department of Treasury and Finance, which is responsible for advising government on regulation policy and performance

- organisations that are subject to regulatory activities

- members of the community that are affected by the business practices that are regulated.

Understanding how these stakeholders are affected by regulation and how they perceive regulators' performance provides essential information for better achieving government's policy goals.

The regulators we examined identified practices where they engaged with regulated organisations, such as when conducting inspections, and one off exercises with other stakeholders such as industry groups and members of the public. However, as we found more generally, the regulators lacked a structured and systematic approach—none have developed a plan to systematically engage with stakeholders and capture feedback from regulated parties or those otherwise affected by regulation, and to use the information gained to improve performance.

All four regulators were able to identify and demonstrate an understanding of their primary stakeholders, although this was not always clearly documented. VPA was the only regulator to have a documented communication plan, setting out the frequency, timing and target audience of its communication activities.

Apart from contact when carrying out inspections, licence renewals and monitoring and enforcement activities, other engagement included telephone information lines, newsletters, presentations to training colleges and industry groups, and membership on national and state-based committees that engage with relevant industry bodies.

These are valuable feedback activities but none of the regulators we examined routinely recorded or documented this information. This is a lost opportunity to improve practices. In addition, the regulators we examined could not demonstrate that they assessed the effectiveness of stakeholder communication activities through mechanisms such as feedback forms or surveys.

One regulator advised that due to resource constraints, it placed a low priority on thorough stakeholder engagement activities and had not received any adverse feedback. While resource constraints are likely to influence the extent, frequency and form of community engagement, the absence of a structured approach is an omission which needs to be addressed.

2.3.5 Collaboration between regulators

Positively, we found examples where the health regulators examined had been proactive in collaborating with each other and with external organisations in areas of shared interest. We identified the following examples where regulators collaborated to improve their operations and avoid duplication:

- VPA communicated breaches of the drugs and poisons legislation by their regulated parties to Drugs and Poisons Regulation. This ensured that VPA minimised overlap and duplication, and did not compromise any existing investigation or enforcement activities.

- Radiation Safety and Pest Control have combined their back office registration and licensing operations into shared systems and databases.

- Pest Control signed a memorandum of understanding with the former Department of Environment and Primary Industries to avoid duplication of overlapping licensing requirements set out in the Public Health and Wellbeing Act 2008 and the Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals (Control of Use) Act 1992.

While we have observed this type of operational collaboration, there is potential for much greater efficiency to be realised through a more coordinated cross-portfolio approach. DHHS is critical to achieving this and we discuss its role in Part 3 of this report.

2.3.6 Performance measurement and reporting

Linking activities and outputs to the achievement of government objectives is a requirement of the government's performance measurement and reporting framework. Doing this well allows regulators and their stakeholders to understand how well they are performing. However, a series of VAGO audits have noted that this has proved very challenging for public sector agencies to do.

Our 2014 audit on Public Sector Performance Measurement and Reporting (2013–14 highlighted that DHHS, in its public reporting, did not adequately link output measures to the achievement of intended objectives. This finding is consistent with what we found in this audit at the four health regulators. In particular, they have not adequately measured and reported on the achievement of regulatory objectives.

Instead the health regulators we looked at have relied on measures of activity or outputs, such as the number of registrations, investigations and inspections. We found few examples of indicators that link these outputs to the intended regulatory outcomes. Current approaches to measuring performance are inadequate to convey performance and to drive continuous improvement.

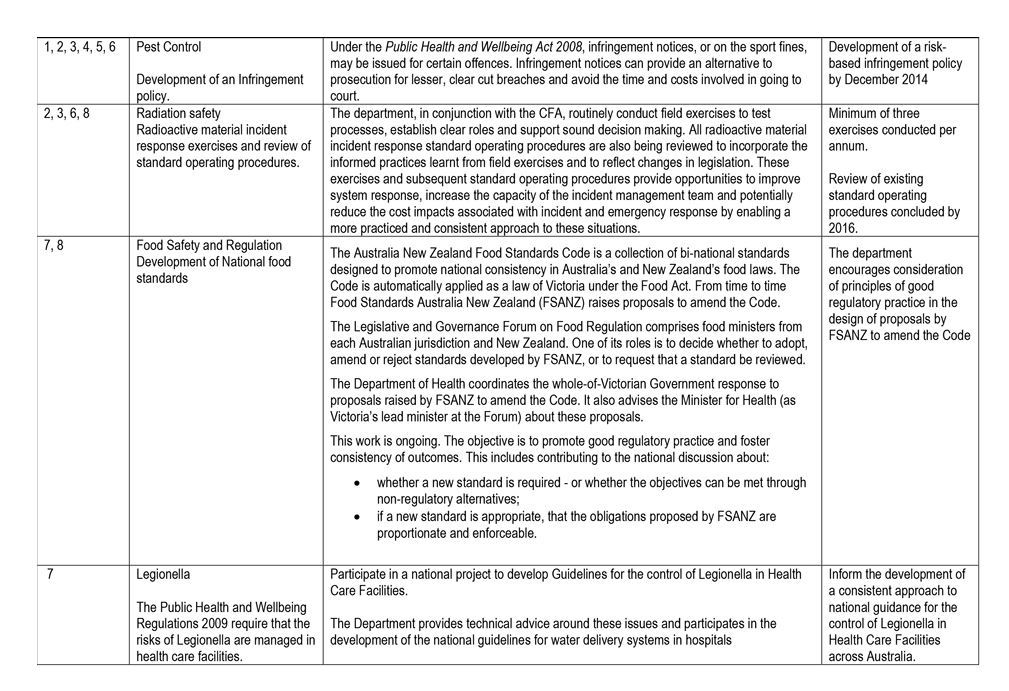

Figure 2B summarises regulators' performance reporting.

Figure 2B

Performance reporting by health portfolio regulators

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on interviews and the review of documents provided by health regulators.

All the regulators we examined need to design and then implement a performance measurement framework that provides sufficient information on their activities and intended outcomes to convey performance and to drive improvements.

2.4 Pathway to improved performance

While the selected health regulators practices are a considerable way short of the better practices we assessed them against, we saw some examples of better practices that illustrate their potential to improve.

Figure 2C describes good practice examples that illustrate how staff are engaged and proactive in carrying out their regulatory responsibilities.

The repeated finding of this Part of the report is the absence of a structured and well planned approach to several components of risk-based regulation. Applying the knowledge and experience displayed through these better practice examples has the potential to significantly improve performance.

As we illustrate in Part 3 of the report, DHHS has a critical role in helping regulators achieve these changes because it offers a perspective that is not immersed in day-to-day regulatory operations and can identify and promote better practice examples.

Figure 2C

Good practice in health portfolio regulators

Drugs and Poisons Regulation: Real-time prescription monitoring system Drugs and Poisons Regulation is working to implement a real-time prescription monitoring system in Victoria. It has developed a business case for a web portal and database designed to enable doctors, pharmacists and jurisdictional health authorities to access real-time information about prescriptions that have been issued for drugs of dependence, such as morphine and methadone, across all pharmacies nationwide. This system is intended to reduce instances of 'prescription shopping', seen as a significant risk to Drugs and Poisons Regulation's objective of protecting public health and safety. It is informed by Coroners Court's findings that illicit drugs were present in 83 per cent of 367 overdose deaths in 2012. Potential benefits Improve efficiency in issuing these drugs, while minimising the harms associated with their misuse. |

Radiation Safety: Tollgate risk management process Radiation Safety has developed a risk management process which it is currently implementing in five regulated areas. Called 'Tollgate', it comprises four 'gates' or stages of risk management:

The most developed application of the Tollgate process is for computed tomography scanning. Having begun in 2011, this process is now at the assessment stage where inspections are being held. Radiation Safety's early evidence indicates that this application of the Tollgate process has reduced noncompliance. Potential benefits Provides a framework to identify, assess, and address significant risks in selected areas of regulatory practice and develop inspection programs that are designed to mitigate these risks. |

Victorian Pharmacy Authority: Collaboration with other regulators VPA and Radiation Safety are working together on a joint approach to managing the risks associated with dispensing drugs containing radioactive materials. They are currently collaborating on a joint inspection protocol which VPA will trial, while Radiation Safety will work to educate inspecting officers about the risks of radiopharmaceuticals. Potential benefits This demonstrates collaboration between regulators in order to address common objectives and new and emerging risks. |

Pest Control: Communication strategy Pest Control is currently developing a communication strategy to raise community awareness of the licensing requirements for pest controllers, and the health risks of using an unlicensed pest controller. It will comprise proactive media and stakeholder engagement, including paid advertisements. The draft strategy includes mechanisms to evaluate the media campaign's effectiveness, such as increases in web hits, feedback or requests for brochures, media coverage, and an increase in public enquiries. Further detail about how the evaluation process will occur is yet to be determined. Potential benefits The draft strategy provides a starting point for a more comprehensive stakeholder engagement plan, which is an important component of effective regulation. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Recommendation

- That all health portfolio regulators develop and implement detailed plans to address the weaknesses identified in this audit by:

- clearly defining the regulatory outcomes they are seeking to achieve

- establishing and applying appropriate stakeholder engagement strategies

- improving their understanding of activity-based costs and benefits and the burden imposed on the entities they regulate

- developing robust performance measurement systems to underpin monitoring and continuous improvement.

3 Departmental oversight

At a glance

Background

This part of the report examines whether the Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) has effectively overseen the regulators in its portfolio, supported them in addressing government's policy goals and advised the Minister for Health on regulator performance.

Conclusion

DHHS has not effectively overseen and supported the regulators within the health portfolio. It currently does not have the structures and processes in place to understand regulators' performance or effectively support continuous improvement.

While instances of collaboration occur between regulators, these are not part of a strategic approach by DHHS to coordinate and integrate regulatory activity.

The lack of central coordination means that DHHS is not capitalising on opportunities to improve regulatory practices in accordance with government's broader regulatory reform agenda. DHHS needs to follow through on the actions it began to transform its approach to managing health regulators.

Findings

- DHHS has not adopted a consistent or coordinated approach to regulation in the health portfolio and departmental oversight of regulators' performance is inadequate.

- These structural deficiencies are reflected in the quality and substance of the Statements of Expectations developed by DHHS for health portfolio regulators.

- Progress on the development of a regulatory reform strategy has been slow and it is unclear what reforms will take place and when they will be implemented.

Recommendation

That DHHS develops and implements a detailed strategy for how it oversees, supports and monitors the performance of health portfolio regulators.

3.1 Introduction

This Part of the report examines whether the Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) has effectively overseen the regulators in its portfolio, supported them in addressing government's policy goals and advised the Minister for Health on regulator performance.

3.2 Conclusion

DHHS has not effectively overseen and supported the regulators within the health portfolio. It currently does not have the structures and processes in place to understand regulators' performance or effectively support continuous improvement.

The lack of a consistent and coordinated approach to regulation in the health portfolio, together with DHHS' limited oversight of the performance of its regulators, is a barrier to regulators' improving their performance. These deficiencies can clearly be seen in the quality and substance of the single Statement of Expectations (SOE) developed by DHHS with embedded health portfolio regulators, which did not provide an adequate framework for measuring and reporting on regulatory progress or the achievement of outcomes.

DHHS has committed to developing and implementing a regulatory reform strategy, but progress to date has been slow and it is unclear what reforms will take place and when they will be implemented. It is important that the work to reform DHHS' approach to regulation proceed because, if done well, it will form the basis for improve performance in the medium to long term.

3.3 Oversight and support weaknesses

Issues with the current oversight framework

DHHS has not adopted a strategic or coordinated approach to the oversight of regulators within the health portfolio. As a result, the regulators embedded within DHHS largely operate as independent units, with distinct practices and approaches to planning and administering regulation.

Each regulator is accountable to senior executives and the Minister for Health through internal structures and processes. However, a lack of central monitoring across all regulators means there is no line of sight enabling DHHS to understand whether regulators are adopting efficient, risk-based approaches to regulation. It also means DHHS has little opportunity to identify where regulators' practices reflect better practice approaches to regulation, or to identify opportunities for improvement.

The potential benefits of improved oversight and support

The co-location of related regulatory units within DHHS provides substantial opportunities for efficiency gains and for improving regulatory practices. Such opportunities include sharing information to gain additional insight that can improve practices, and integrating processes such as inspections to reduce the resources and time required. Closer collaboration between regulators can also improve the experience for regulated parties by minimising the need for numerous interactions with multiple regulators.

The need for reform in departmental oversight and support

In 2014, the Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission (VCEC) identified integration as a key opportunity for improving Victoria's regulatory system. It highlighted that fragmentation of the system undermines the capacity of regulators to adopt more efficient and effective practices, and weakens accountability. VCEC also noted a number of barriers to better integration, including legislative impediments to information sharing, and cultural impediments such as regulators questioning the costs and benefits of collaboration.

Overcoming these barriers requires sustained focus, and a strong understanding of the benefits that could be gained from closer integration. DHHS has a clear role to play in this regard. While we found instances of collaboration occurring between regulators, these were not part of a strategic approach to coordinate and integrate regulatory activity by DHHS. This lack of central coordination means that DHHS is not capitalising on opportunities to improve regulatory practices in accordance with government's broader regulatory reform agenda. This is a significant missed opportunity for DHHS.

3.4 Developing SOEs—the need for improved oversight and support

The Stage 2 SOEs applied to all regulators, including those in the health portfolio. These SOEs and the departmental and regulator responses to them were intended to form the basis for improved regulatory outcomes, including through the application of more risk‐based, proportionate and targeted approaches to regulation.

We found significant shortcomings in the content of these SOEs and responses and with DHHS' management of this process. DHHS has acknowledged these shortcomings and recognised the need to more effectively manage government initiatives to improve regulator performance. The 2014 SOE process presented considerable challenges for DHHS because it was the first time it had to prepare SOEs and within tight time lines that coincided with it implementing an organisational restructure.

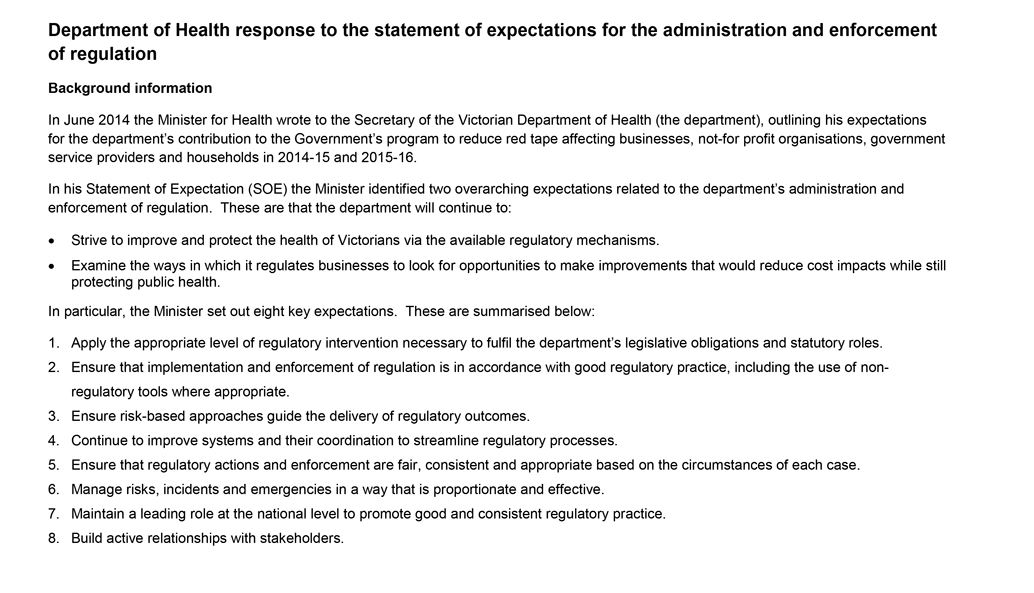

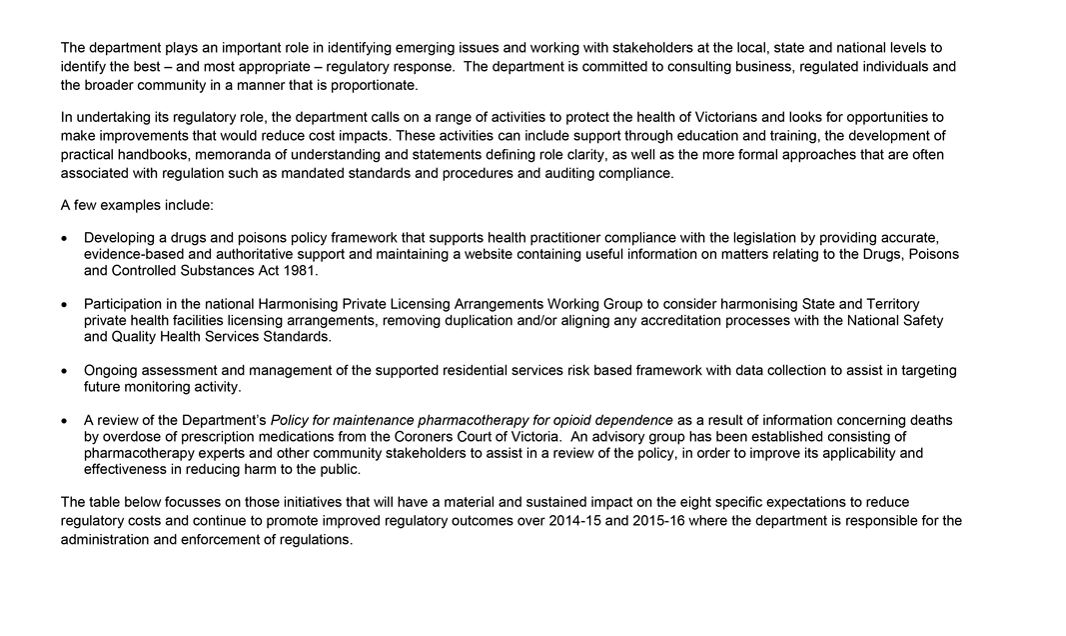

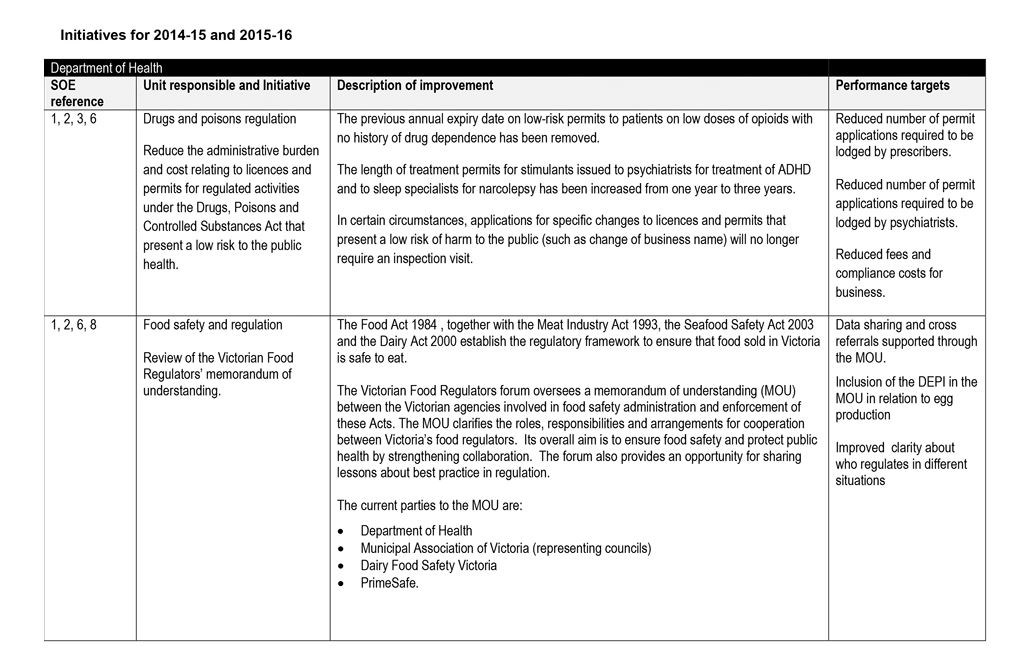

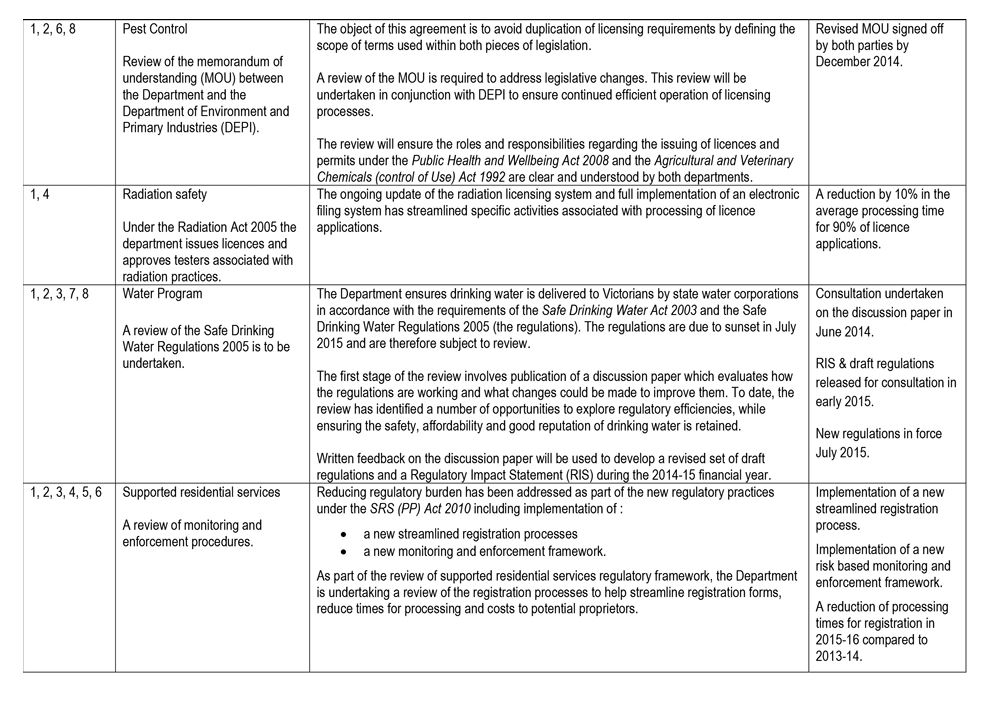

SOE for regulators embedded in DHHS

DHHS created a single SOE for the embedded regulators. It:

- defined eight common expectations for these regulators

- documented regulators' responses to the agreed improvements and performance targets in a single SOE—see Appendix A.

Figure 3A lists the minister's eight key expectations of DHHS' administration and enforcement of regulation.

Figure 3A

Ministerial expectations

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on DHHS information.

While DHHS met the July 2014 deadline for submitting the SOE and the response, this material does not form an adequate basis for improving regulation and regulatory outcomes as intended by government because:

- the stated expectations were too generic and were not underpinned with specific targets or a framework for measuring and reporting on progress

- regulators' responses were high level and did not address all of the expectations—for example, three regulators committed to a single initiative in response to the eight expectations, and one regulator provided no initiatives

- the performance targets provided by regulators were vague and generic, with few specific metrics, and largely described outputs rather than outcomes—for example, 'Improve clarity about who regulates in different situations' and 'steady increase in the number of online forms received by prescribers'

- the agreed improvements did not comprehensively describe how regulators would develop and implement risk-based regulation to improve performance.

The three regulators embedded within DHHS advised that many of the initiatives incorporated into the SOE were already underway. As such, the SOE process did not map a clear and comprehensive path to improve regulatory performance.

Appendix A contains the combined departmental response to the SOE for regulators embedded in DHHS.

SOEs for statutory authority health regulators

Two of the three statutory regulators in the health portfolio were required by the Minister for Health to respond to SOEs. The role of the Health Services Commissioner is being substantially changed and was not required to respond to an SOE.

DHHS' management of the SOE development process for these two regulators was inadequate and poorly documented. As a result both SOEs and responses missed the July 2014 deadline. The SOE and response from the Victorian Assisted Reproduction Treatment Authority's was submitted in November 2014 while the Victorian Pharmacy Authority's response was not finalised at the time of publishing this report.

The evidence shows that DHHS did not effectively engage with these statutory authority regulators and it cannot provide a clear account of the process it followed because of the absence of documentation. This absence of a structured and methodical approach by DHHS was the primary cause of the delays.

This again highlights the need for a structured and consistent approach to the oversight of and communication with health portfolio regulators, including the independent statutory regulators within the portfolio.

3.5 Restructure and reform at DHHS

DHHS has recognised the need for greater coordination of regulatory practices and the allocation of resources. In April 2014, a departmental restructure led to the establishment of a new division, which from 1 January 2015 has been called the Health Regulation, Protection and Emergency Management Division. A key aim of this restructure was to achieve a renewed focus on regulatory reform and red tape reduction in the health system.

Within this newly created division, the Health Review and Regulation Branch is responsible for policy development and giving strategic advice on how regulation and the statutory roles of DHHS can support reform and innovation in the health care system—improving health outcomes for Victorians. A key initiative of this branch is to develop a regulatory reform strategy, intended to deliver significant benefits by developing and sharing best practice across health regulators.

This is a positive development that has the potential to drive improvements in the administration of regulation, and in turn, the efficient achievement of objectives. However, work to develop a department-wide approach to regulation—an action committed to in the 2014–15 divisional plan—remains in its very early stages.

DHHS has yet to prepare a project plan or time line for its implementation. Doing so is critical for DHHS to achieve broader regulatory reform, as well as departmental objectives. The machinery-of-government changes which came into effect on 1 January 2015 will create additional challenges for this work.

DHHS has previously identified the value of a coordinated, department-wide approach to regulation. In 2009, the former Department of Health commissioned work to explore the diversity of regulatory practices used by its regulatory units, with a view to identifying better practice principles. This work concluded that there was very limited sharing of existing practices, and limited documentation on current approaches or the rationale for these approaches.

This work recommended a set of better practice principles to guide DHHS' regulatory functions, including that:

- regulation is a common system with complementary aims

- regulation should be based on risk

- there be consistency, predictability and enforcement in regulation

- the department review performance in market segments on an annual basis, and conduct a full review of regulation every three years.

DHHS advised that this work was not progressed as it was required to reorient its priorities towards the government's red tape reduction agenda, developing legislation to support this agenda, and administering regulation. However, the insight gained through this work remains relevant.

Developing more effective oversight and support for health portfolio regulators has the potential to unlock significant benefits by:

- better identifying and disseminate better practice across regulators, for example, through regular communications and forums

- identifying synergies, efficiencies and the potential benefits of legislative reform and consolidation

- helping regulators address the identified weaknesses in their approach to risk-based regulation through specific research, for example, research into activity-based costs, benefits and the impact of regulation on businesses.

As a first step, DHHS needs to develop and implement a detailed strategy to shape and direct its regulatory activity. To be effective, this strategy will need to include:

- clear regulatory objectives

- a framework that defines intended outcomes and how these will be measured and reported on

- an evidence-based description of the barriers to change

- specific actions designed to achieve the objectives and overcome these barriers

- a governance structure that clearly allocates roles and responsibilities and encourages cross-departmental collaboration

- support mechanisms to implement, monitor and evaluate the strategy.

Recommendation

- That the Department of Health & Human Services develops and implements a detailed strategy for how it oversees, supports and monitors the performance of health portfolio regulators.

4 DTF's delivery of the SOE framework

At a glance

Background

The Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) plays a key role in furthering government's objectives of providing more efficient, effective and less burdensome regulation. DTF advises government on how to best achieve these goals, guides and supports program implementation and reports on progress and outcomes.

We examined how well DTF had done this for reforms affecting regulators in the health portfolio—the application of Stage 2 Statements of Expectation (SOE).

Conclusion

DTF's management of the Stage 2 SOE policy contributed to inadequate health portfolio SOEs. We identified weaknesses in how DTF managed the reform process and these need to be addressed.

Findings

- DTF's advice to government regarding the Stage 2 process did not adequately convey the risks that the proposed time lines and level of support presented to delivering SOE's that would help achieve government's objectives.

- DTF did not adequately define how SOEs would be evaluated to measure the achievement of intended outcomes.

Recommendations

That DTF:

- improves the quality and comprehensiveness of its advice to government about the risks that threaten the success of regulatory reform programs

- develops an appropriate evaluation framework for future regulatory reform programs, before they are implemented, that clearly describes how performance will be assessed and who is responsible for doing this

- assesses and incorporates in regulatory reform programs the level of support required for successful implementation and aligns the level of support offered with the characteristics and capabilities of different regulators.

4.1 Introduction

Government aimed to reduce the burden that regulators impose on businesses, while improving their effectiveness and efficiency. The mechanisms for achieving these improvements included a red tape reduction program and a requirement for departments and regulators to respond to ministerial Statements of Expectations (SOE).

In this Part we examine whether the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) had adequately acquitted its responsibilities of advising on government policy, supporting regulators and departments in developing SOEs, and coordinating and reporting on whole-of-government reforms.

This forms only a partial assessment of DTF's performance, because we have based the findings on how health portfolio regulators and the Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) have applied this government policy.

We have focused on the second stage of the SOE policy because this applied to DHHS regulators. The objective of Stage 2 was to provide the platform for regulators to significantly improve their governance and performance across a range of areas that constitute good regulatory practice.

4.2 Conclusion

DTF's management of the government's Stage 2 SOE policy has not been effective and has contributed to inadequate health portfolio SOEs.

DTF's recommended approach to implementing this policy included proactive support up to the point of implementation. For the implementation DTF allowed a four-month time line, flexibility in how departments and regulators responded to the policy and a reactive rather than proactive approach to review and support. Government approved this.

However, DTF's advice did not adequately convey the risks this approach presented to achieving government's objectives. The risks of not having sufficient time or the support needed to develop adequate SOEs are relevant for the health portfolio, where departmental oversight is ineffective, and where regulators are not advanced in their application of risk-based regulation.

DTF underestimated the varying support needs of agencies and did not realistically assess the time health portfolio agencies would need to adequately address the SOE requirements.

In addition, DTF did not adequately define how regulators' responses to SOEs would be evaluated to measure the achievement of intended outcomes. Our repeated experience in past VAGO audits is that the absence of a fit-for-purpose evaluation framework at the start of the process undermines performance measurement and the focus on achieving outcomes.