Portfolio Departments and Associated Entities: Results of the 2011–12 Audits

Overview

This report presents the outcomes and observations from the external financial audit of 11 portfolio departments and 193 associated entities. Additionally, it comments on the quality of financial reporting, the financial sustainability of self-funded state entities and the effectiveness of internal controls over the appropriation framework, trust funds and risk management.

Financial reporting by the portfolio departments and associate entities is reliable. However, shortcomings were observed in the control frameworks governing appropriations and trust funds, and of disclosure of post-employment remuneration and ex gratia payments.

Portfolio Departments and Associated Entities: Results of the 2011–12 Audits: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER November 2012

PP No 198, Session 2010–12

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on Portfolio Departments and Associated Entities: Results of the 2011–12 Audits.

Yours faithfully

D D R PEARSON

Auditor-General

28 November 2012

Audit summary

This report presents the outcomes and observations from the external financial audit of 11 portfolio departments and 193 associated entities. Additionally, it comments on the quality of financial reporting, the financial sustainability of self-funded state entities and the effectiveness of internal controls over the appropriation framework, trust funds and risk management.

Conclusion

Financial reporting by portfolio departments and associated entities is reliable. However, shortcomings were observed in the control frameworks governing appropriations and trust funds, and of disclosures of post-employment remuneration and ex gratia payments.

Quality of financial reporting

The Financial Reporting Direction (FRD) to public sector entities covering the reporting of responsible person and executive officer remuneration has a narrow definition of remuneration.

As a consequence, three public sector bodies, including one portfolio department, were able to limit disclosure of information relating to post‑employment benefits paid to former responsible persons.

The requirement to report ex gratia payments made by a public sector entity is similarly covered in an FRD. The requirement, however, is minimal and allows public sector agencies to exercise significant discretion over the level of disclosure made on the nature and reasons for the payments.

Financial sustainability

The financial sustainability of 46 self-funded state entities was assessed using four indicators that consider both short-term and long-term sustainability. The assessment flags short-term financial risks for 13 entities and long-term financial risks for a further 16 entities. This result is consistent with prior years and indicates continuing challenges for these entities to generate revenue from operations to fund asset replacement.

The appropriation framework

The principal source of funding for the general government sector is through the annual Appropriation Act, which in 2011–12 allocated $39.2 billion to the 11 portfolio departments.

The funding for portfolio departments is based on a purchaser-provider model, where appropriations are awarded by the Treasurer for the delivery of services to an agreed output standard. At 30 June 2012, portfolio departments had delivered 71.4 per cent of the agreed output targets for the financial year, but 99.97 per cent of requested appropriations were awarded. It is not evident that there are adverse consequences for underdelivery or non-delivery.

Portfolio departments can generate a surplus by delivering outputs at a cost less than the agreed level. Surpluses can be accumulated and used to deliver additional public services or infrastructure above those funded annually by appropriation. Portfolio departments report the accumulated amount as a receivable in their financial statements; operationally, it is referred to as the state administration unit (SAU).

At 30 June 2012, $1.4 billion was available across the 11 portfolio departments to deliver additional public services and infrastructure. Nevertheless, no portfolio department other than the Department of Health could demonstrate strategies to use these reserves in the current economic climate.

Where required, portfolio departments can access additional funds to meet urgent expense claims which are unforeseen and therefore not provided for in the Budget. Commonly known as Treasurer’s advances, this emergency funding is permitted under the Appropriation Act, where money is set aside as an ‘advance to Treasurer to enable Treasurer to meet urgent claims that may arise before Parliamentary sanction is obtained, which will afterwards be submitted for Parliamentary authority’.

During 2011–12, the Treasurer approved 48 Treasurer’s advances with a total value of $776 million. Over the past five years, 56 per cent of the Treasurer’s advances awarded have been to assist portfolio departments in meeting wages, depreciation, administration costs and capital projects. These types of expenses are routine, yet the use of Treasurer’s advances to meet them is inconsistent with the Appropriation Act, which provides for Treasurer’s advances to be used only for urgent expenditure which is unforeseen.

Trust funds

Trust funds are discrete accounts established to record the receipt and disbursement of state funds for specified purposes. They can be set up under their own legislation or by the Minister for Finance under the Financial Management Act 1994.

At 30 June 2012, 111 trust funds were held across the 11 portfolio departments, with a total value of $2.7 billion. The number and value of trust funds held is growing year on year, however, with one exception, portfolio departments and the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) (on behalf of the Minister for Finance) could not demonstrate they had systematically reviewed the nature and purpose of each trust to confirm relevance and alignment with the strategic objectives of government.

There is evidence that treasury trust funds are not being used as intended. Treasury trust funds are established to hold unclaimed and unidentified money, however, there is evidence that revenue and appropriations are being deposited, and expenses raised, out of these trust funds. Further, the Department of Business and Innovation is operating a working trust; however, neither the department nor DTF could provide evidence that the trust had been legally established.

While trust fund balances are reported by portfolio departments in their financial statements at the end of each financial year, there is no public reporting of the amount of money flowing into and out of each trust annually. There is also no disclosure of the nature and purpose of each trust. Consequently, there is a lack of transparency in reporting to Parliament on trust funds.

Risk management

The risk management practices at the 11 portfolio departments are adequate, with general compliance against the Victorian Government Risk Management Framework and the international risk management standard. Further improvements in risk management could be achieved by portfolio departments strengthening risk management policies and training.

An annual attestation on compliance with the international risk management standard has been required since 2007. Three portfolio departments are still developing or improving their risk management controls and framework.

Recommendations

- The Department of Treasury and Finance should:

- revise Financial Reporting Direction (FRD) 21B to align the disclosure of remuneration of responsible persons and executive officers with Australian Accounting Standards for private sector entities

- revise FRD 11 to mandate meaningful disclosure of the nature, purpose and amount of ex gratia payments made by public sector entities.

- The implications of the financial sustainability challenges for the accountability of boards, councils and trusts should be reviewed, and a strategy to address them developed.

- The Department of Treasury and Finance should review the implementation of the appropriation framework to determine whether acquittal and approval procedures are delivering funding outcomes consistent with its aims.

- Portfolio departments should, in consultation with the Department of Treasury and Finance, include in their long‑ and short-term plans a clear link between the use of the accumulated state administration unit balances, and the provision of additional services to the public, and infrastructure, consistent with the model.

- The Department of Treasury and Finance should adopt a definition of urgent that would mean that Treasurer’s advances are awarded only for purposes consistent with the Appropriation Act.

- The Department of Treasury and Finance should:

- review every treasury trust fund to determine whether it is being used as intended, and address noncompliance as necessary

- review its trust fund guidelines for consistency with better practice.

- The Department of Business and Innovation should confirm its legal authority to operate its working trust or close the trust.

- The Department of Treasury and Finance and portfolio departments should periodically review the purpose and currency of trusts to assess alignment with changing government objectives.

- To better inform users of financial statements and provide greater transparency to the Parliament and the public, reporting requirements should be enhanced to require annual disclosure of the nature and purpose of each trust and the amount of its revenue and expenditure.

- That portfolio departments should:

- review and approve risk management policies annually

- conduct regular tailored training for all staff on risk identification and management

- act decisively to address areas of noncompliance with the risk management standard.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report, or relevant extracts from the report, was provided to all portfolio departments and named agencies with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix F.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

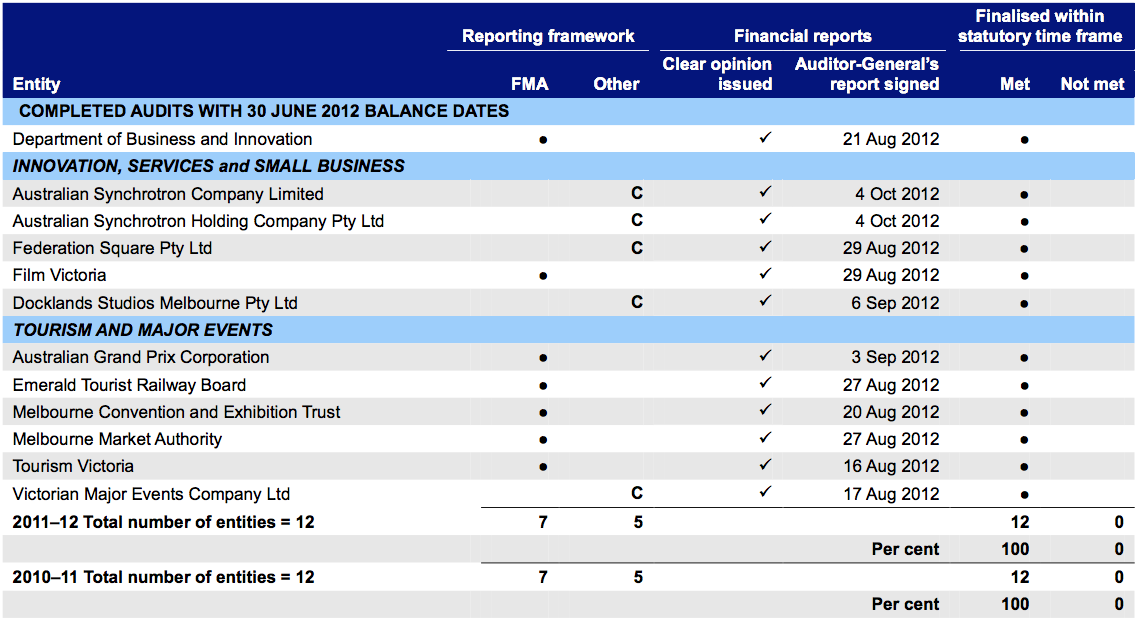

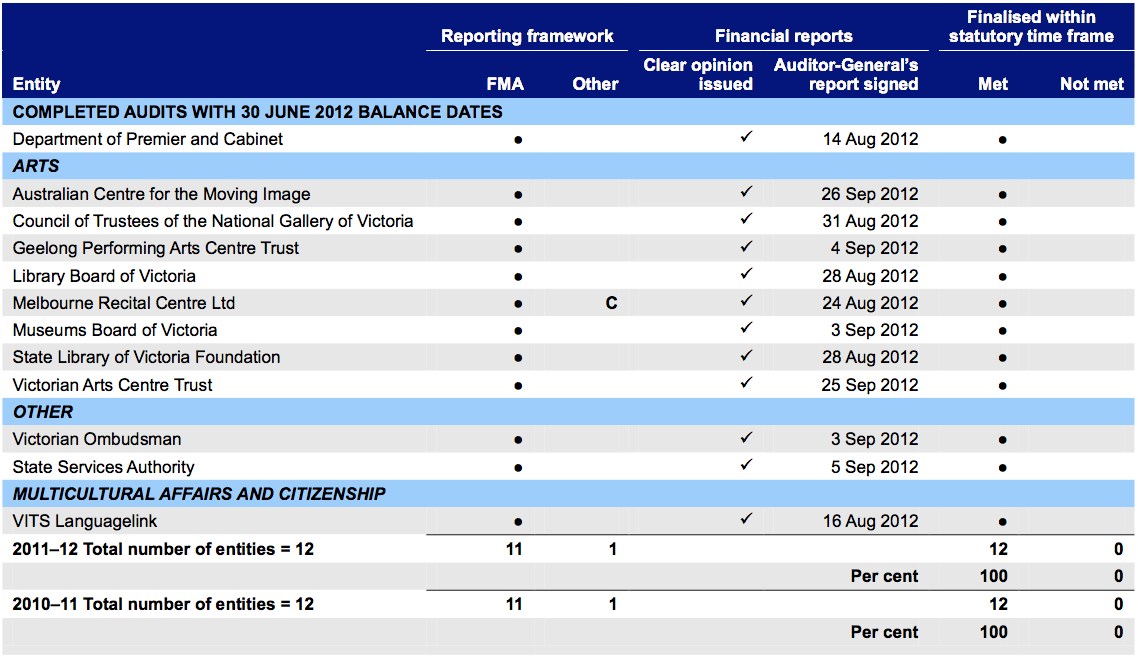

This report covers 11 portfolio departments and 193 associated entities with 30 June 2012 balance dates. These entities report under a range of legislation, the most common being the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA) and the Corporations Act 2001. Figure 1A shows the number of entities per portfolio and legislative reporting framework.

Figure

1A

Entities by portfolio and legislative reporting framework

Financial Management Act |

Corporations Act |

Other |

Total |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portfolio |

2011–12 |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2010–11 |

Parliament |

2 |

2 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

2 |

2 |

Business and Innovation |

7 |

7 |

5 |

5 |

– |

– |

12 |

12 |

Education and Early Childhood Development |

6 |

6 |

2 |

3 |

– |

– |

8 |

9 |

Health |

15 |

14 |

– |

– |

1 |

1 |

16 |

15 |

Human Services |

2 |

3 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

2 |

3 |

Justice |

26 |

25 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

30 |

28 |

Planning and Community Development |

13 |

13 |

1 |

1 |

– |

– |

14 |

14 |

Premier and Cabinet |

11 |

11 |

1 |

1 |

– |

– |

12 |

12 |

Primary Industries |

10 |

10 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

13 |

13 |

Sustainability and Environment |

38 |

36 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

38 |

36 |

Transport |

10 |

8 |

7 |

6 |

– |

– |

17 |

14 |

Treasury and Finance |

15 |

17 |

7 |

20 |

18 |

19 |

40 |

56 |

155 |

152 |

27 |

40 |

22 |

22 |

204 |

214 |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

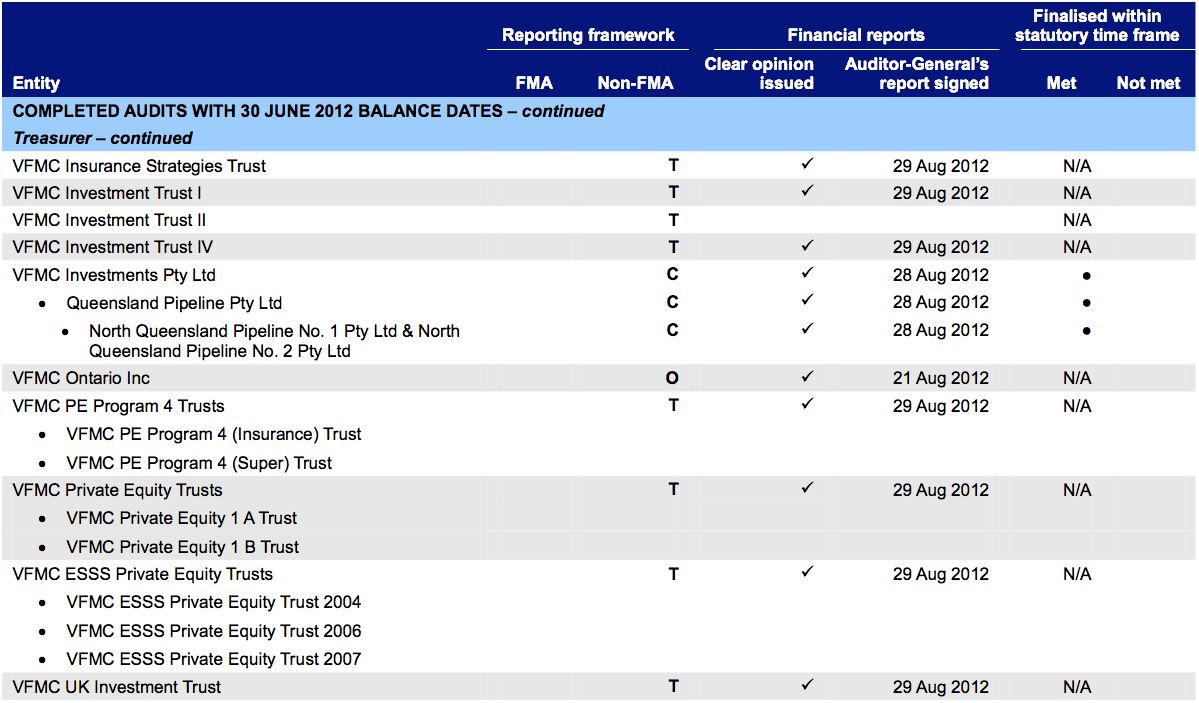

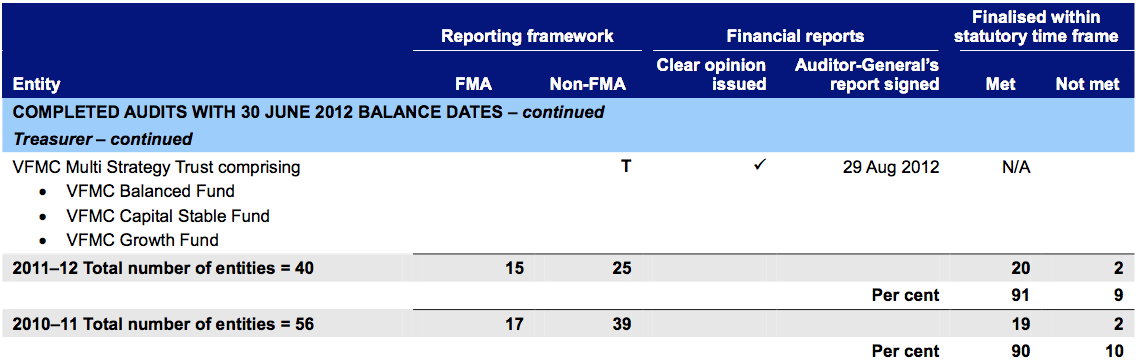

The total number of entities subject to audit decreased by 10 in 2011–12. A list of the changes is provided in Figure 1B.

Figure

1B

Changes to audited entities

Merged with another entity |

|

Registrar of Housing Agencies |

Previously in the Human Services portfolio, subsequently transferred to the Treasury and Finance portfolio, where an exemption from separately reporting was granted under the Financial Management Act 1994. The transactions and balances are reported by the Department of Treasury and Finance. |

New audits |

|

Victorian Traditional Owners Trust |

Established on 13 September 2011 following introduction of the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010, which required a trust fund to be created for settlement proceeds. |

Victorian Traditional Fund Limited |

Established on 13 September 2011 under a settlement agreement between the Attorney-General (on behalf of the State of Victoria) and the Gunaikurani people. |

Port of Hastings Development Authority |

Established to facilitate development of the Port of Hastings to increase capacity and competition in the container ports sector servicing Melbourne and Victoria. Commenced operations on 1 January 2012. |

Taxi Services Commission |

Established in July 2011 to conduct a major inquiry into the Victorian taxi and hire car industry. Will also take on the role of the industry regulator in place of the current regulator, the Victorian Taxi Directorate. |

Metlink Victoria Pty Ltd |

On 2 April 2012, the Public Transport Development Authority acquired all Metlink shares. All the employees, assets and liabilities were transferred. |

VFMC PE Program 4 (Insurance) Trust and VFMC PE Program 4 (Super) Trust |

Constituted together as VFMC PE Program 4 Trusts on 13 December 2010. |

VFMC Investment Trust IV |

Constituted on 20 February 2012. |

VFMC Insurance Strategies Trust |

Constituted on 10 June 2011. |

North Queensland Pipeline No. 1 Pty Ltd & North Queensland Pipeline No. 2 Pty Ltd |

Subsidiaries created by Queensland Pipeline Pty Ltd. |

Victorian Pharmacy Authority |

Established under the Pharmacy Regulation Act 2010 (the Act). Successor in law to the Pharmacy Board of Victoria. Responsible for administration of the Act, which provides for the regulation of pharmacy businesses, pharmacy departments and pharmacy depots. |

Victorian Environmental Water Holder |

Established on 1 July 2011 under the Water Act 1989. An independent statutory body to decide on the best use of Victoria’s environmental water entitlements. |

Wound up |

|

Victorian Commission for Gambling Regulation |

Wound up on 5 February 2012 and a final audit opinion issued on 1 June 2012. Replaced by the Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation, which reported at 30 June 2012. |

Responsible Gambling Advocacy Centre Ltd |

Operations ceased 29 June 2012. Many functions, including providing information to the public about responsible gambling and its regulation in Victoria, to be provided by the Gambling Information Resource Office, part of the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation. |

Housing Guarantee Claims Fund |

Ministerial notice issued on 6 May 2011 to wind up the fund. |

Victorian Neurotrauma Initiative Pty Ltd |

Ceased as a company on 30 May 2011. All committed funded activities have continued. Committed research activities transitioned to the Transport Accident Commission (TAC). Deeds of novation executed, transferring all previous rights and responsibilities to TAC. |

State Electricity Commission of Victoria subsidiary company A.C.N 151803629 Pty Ltd and the 13 companies held by the subsidiary:

|

Wound up on 22 December 2011. |

Transferred between portfolios |

|

Victorian Plantations Corporation |

Transferred from the Treasury and Finance portfolio to the Sustainability and Environment portfolio. |

Other |

|

TAFE Development Centre |

Changed from a 30 June balance date to a 31 December balance date. |

Victorian Urban Development Authority |

Victorian Urban Development Authority Amendment (Urban Renewal Authority Victoria) Act 2011 discontinued this entity and established Places Victoria, proclaimed on 25 October 2011. Places Victoria reported at 30 June 2012. |

VFMC Private Equity Trust 1A VFMC Private Equity Trust 1B |

These trusts reported separately in 2010–11, however prepared only one consolidated report in 2011–12. |

VFMC ESSS Private Equity Trust 2004 VFMC ESSS Private Equity Trust 2006 VFMC ESSS Private Equity Trust 2007 |

These trusts reported separately in 2010–11, however prepared only one consolidated report in 2011–12. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

This report comments on the quality of financial reporting, the financial sustainability of self-funded state entities and the effectiveness of internal controls over the appropriation framework, trust funds and risk management. The other VAGO reports on the results of our 2011–12 financial audits are outlined in Appendix A.

1.2 Reporting framework

Financial statements are required to be prepared in accordance with Australian Accounting Standards, including the Australian Accounting Interpretations and legislated reporting frameworks. Under the FMA, the Minister for Finance has the authority to issue directions in relation to finance administration and reporting issues.

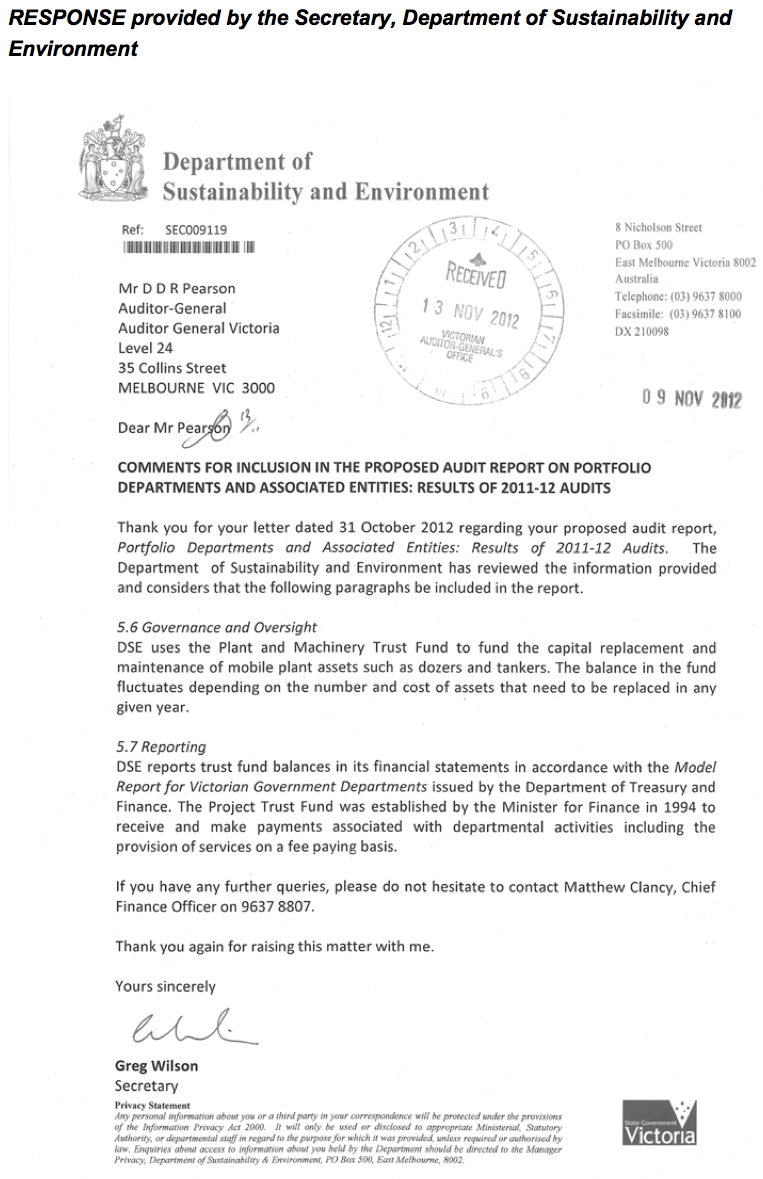

The FMA requires annual reports to be submitted to the relevant minister and tabled in Parliament within four months of the end of the financial year. These reports should include financial reports for the entity and any controlled entities, and are required to be prepared and audited within 12 weeks of the end of the financial year.

Entities reporting under the Corporations Act 2001 are required to report to their members within four months of the end of the financial year.

A summary of the FMA and Corporations Act 2001 reporting time frames is provided in Figure 1C.

Figure

1C

Legislated

financial reporting time frames

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

To achieve timelier reporting more consistent with current community standards, the Premier issued a circular on 10 February 2012 requiring annual reports to be tabled within three months of the end of the financial year. This was consistent with the past two years, but meant that the timeframe for preparing, auditing and tabling financial statements was shorter than shown in Figure 1C. Ministers and government departments work with their portfolio public sector entities with a view to progressively tabling annual reports in Parliament from the end of the second month after the end of the financial year.

1.3 Internal controls

Effective internal controls help entities reliably and cost-effectively meet their objectives; they underpin the reliable, accurate and timely delivery of external and internal reports.

Senior management of an entity is responsible for developing and maintaining adequate systems of internal control to enable:

- preparation of accurate financial records and other information

- timely and reliable external and internal reporting

- appropriate safeguarding of assets

- prevention or detection of errors and other irregularities.

The FMA requires management to implement an effective internal control structure. In establishing effective controls, it should adopt a control framework that has:

- comprehensive policies

- effective management practices

- sound governance and oversight.

In our annual financial audits, we focus on the internal controls relating to financial reporting and assess whether entities have managed the risk that their financial statements will not be complete and accurate. Poor controls diminish management’s ability to achieve strategic objectives and to comply with relevant legislation. They also increase the risk of fraud. Internal control weaknesses identified during our audits are reported to an entity’s management and audit committee.

For portfolio departments, in addition to reviewing general internal controls, a cyclical approach to reviewing internal controls relating to significant annual financial report balances and disclosures is adopted, consistent with Australian Auditing Standards.

This report includes the results of our cyclical review of the appropriation framework, trust funds and risk management.

1.4 Structure of this report

The structure of this report is set out in Figure 1D.

Figure

1D

Report structure

Parts |

Description |

|---|---|

Part 2: Quality of financial reporting |

Comments on the quality of financial reports prepared by portfolio departments and associated entities. |

Part 3: Financial sustainability |

Provides insight into the financial sustainability of the 46 self-funded state entities based on assessment of four indicators that consider both short-term and long-term sustainability. |

Part 4: The appropriation framework |

Comments on aspects of the appropriation framework and the policies, controls, governance and oversight to support the framework. |

Part 5: Trust funds |

Comments on the controls, governance, oversight and reporting of trust funds used to receive and distribute funds for designated purposes. |

Part 6: Risk management |

Reviews risk management practices at the 11 portfolio departments against the Victorian Government Risk Management Framework and international risk management standard. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

1.5 Audit conduct

The audits were undertaken in accordance with Australian Accounting Standards.

The total cost of preparing and printing this report was $200 000.

2 Quality of financial reporting

At a glance

Background

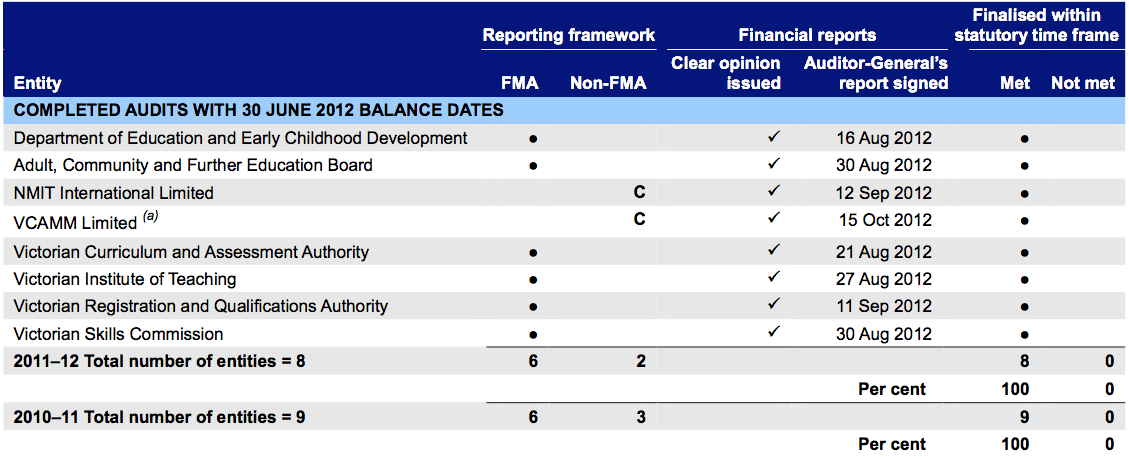

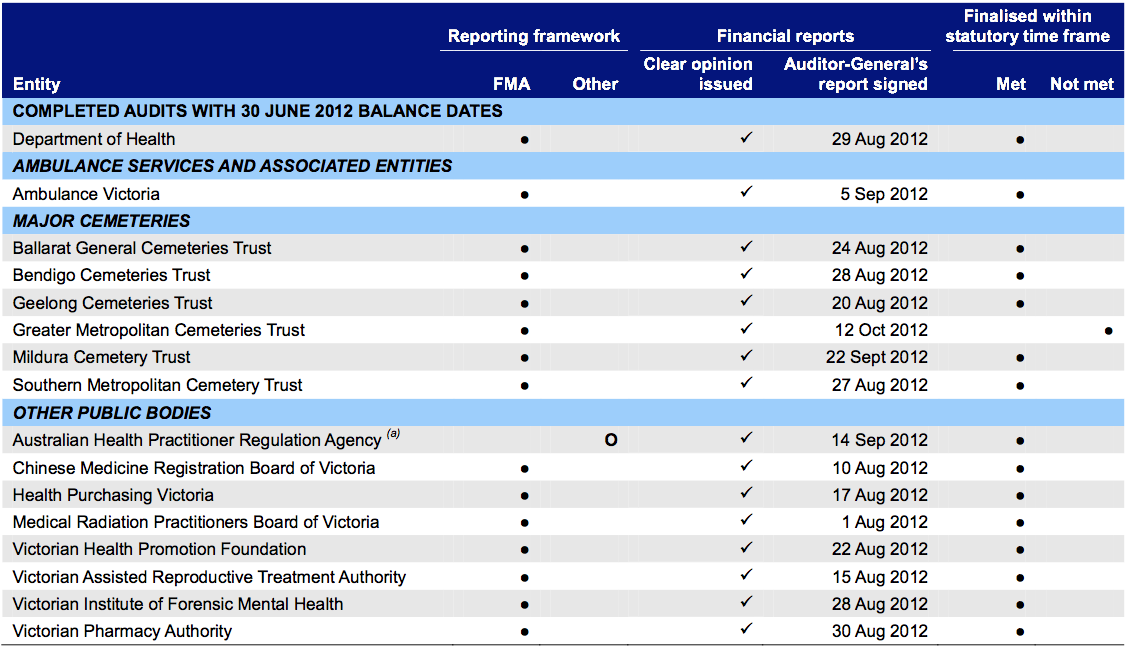

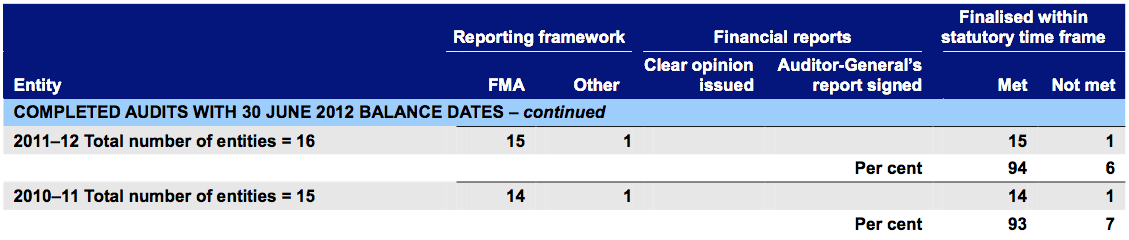

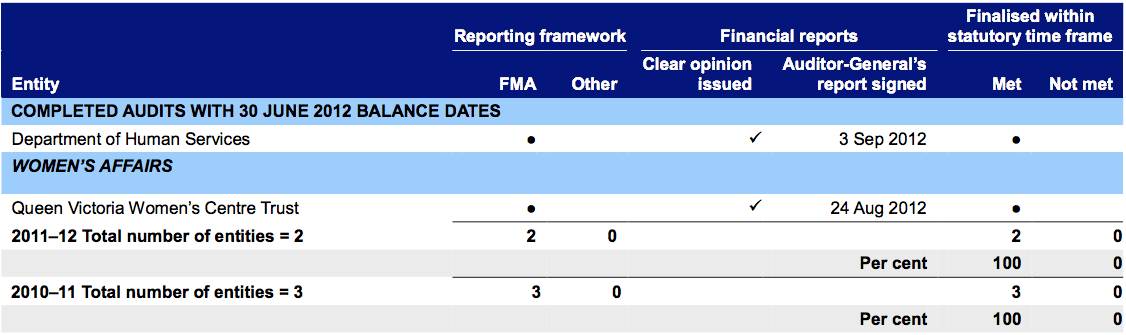

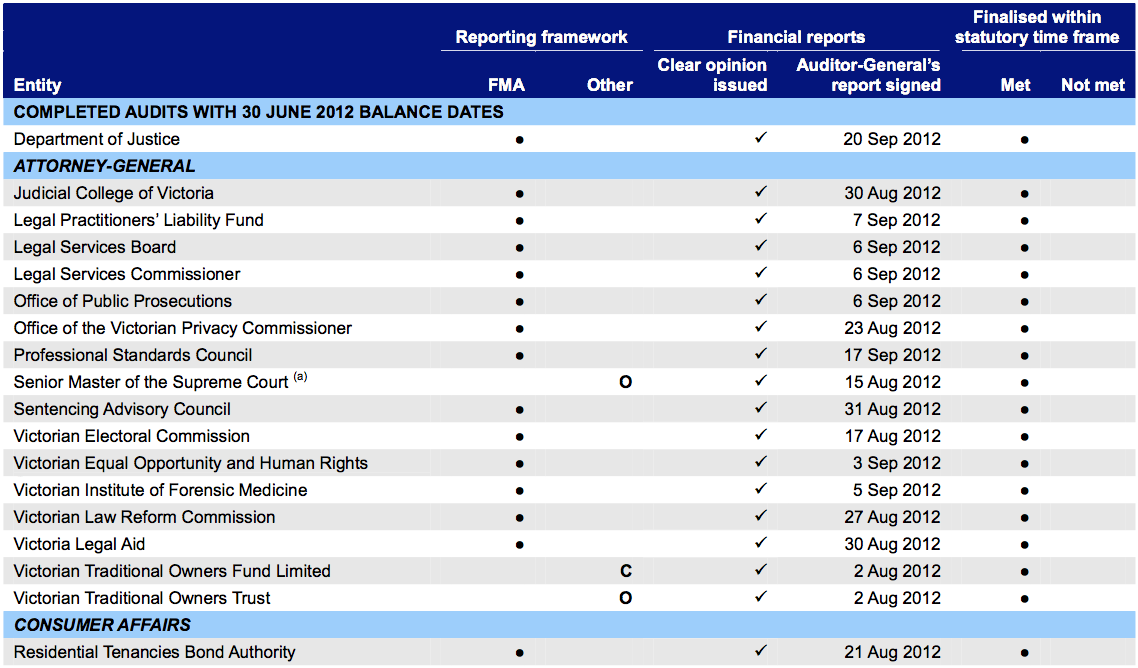

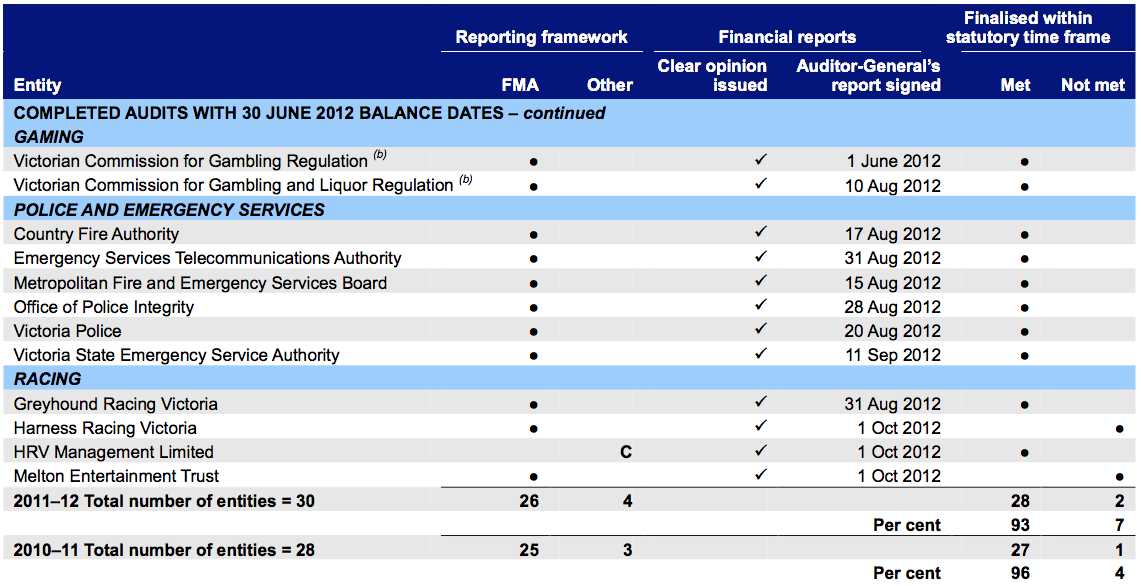

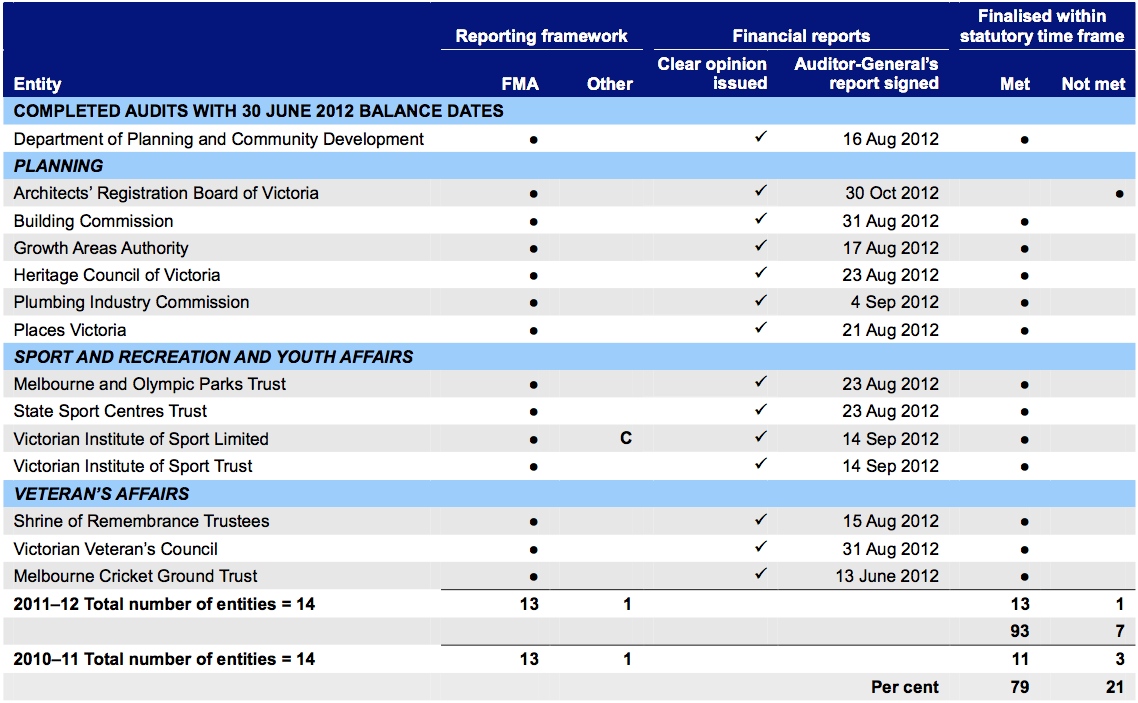

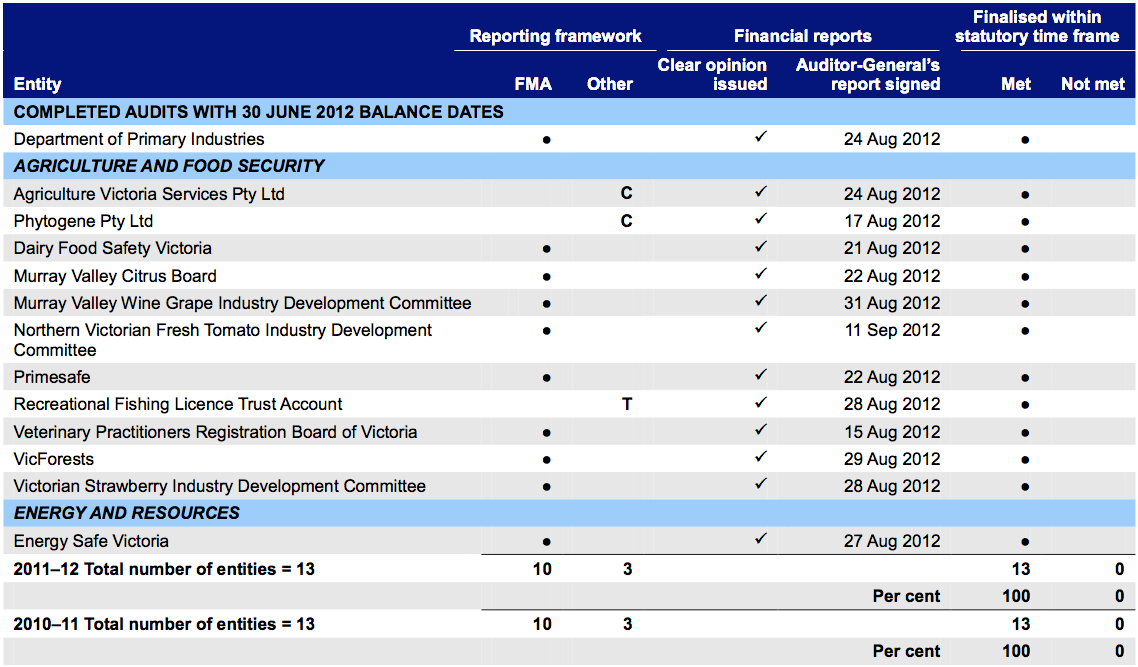

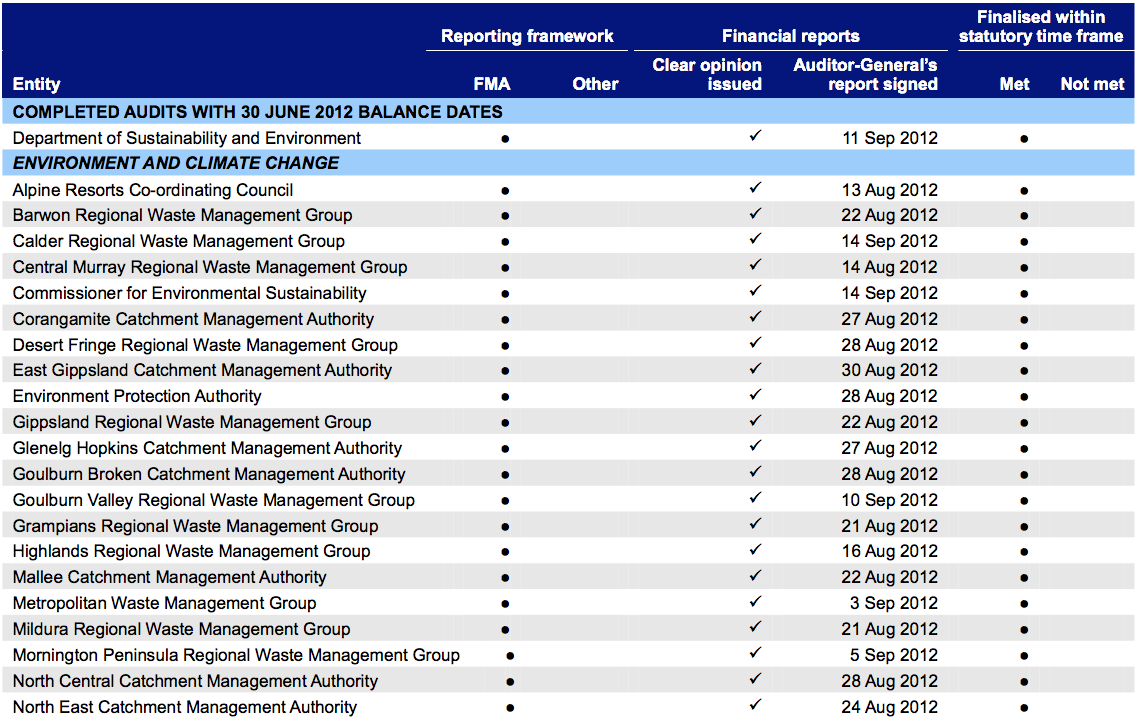

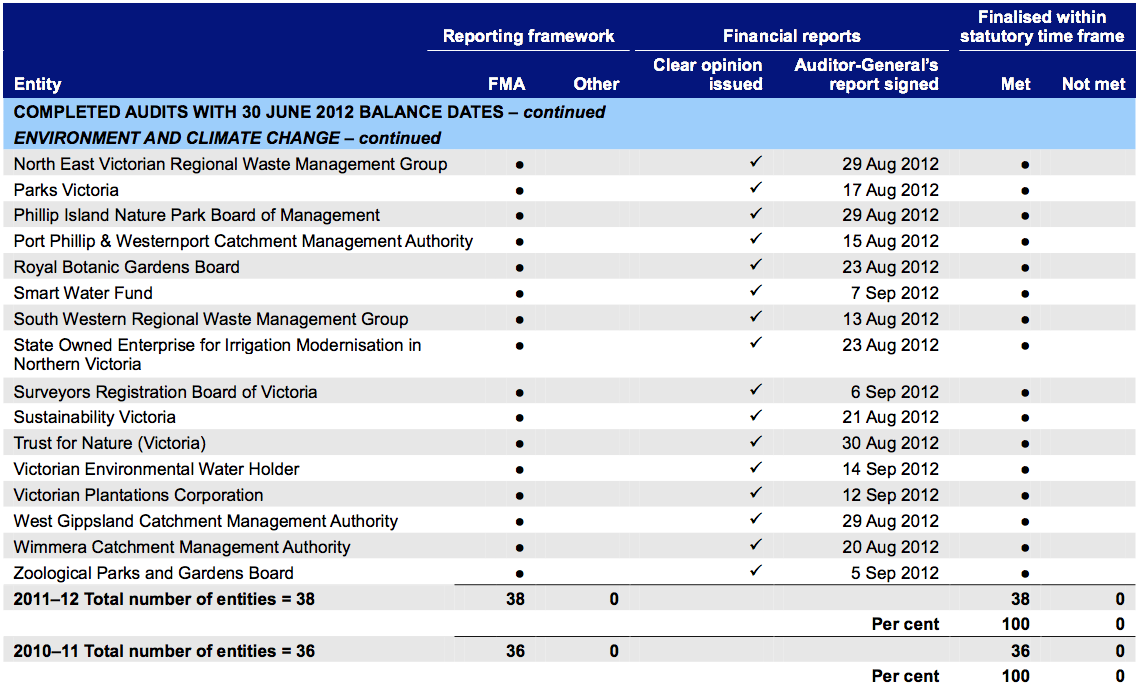

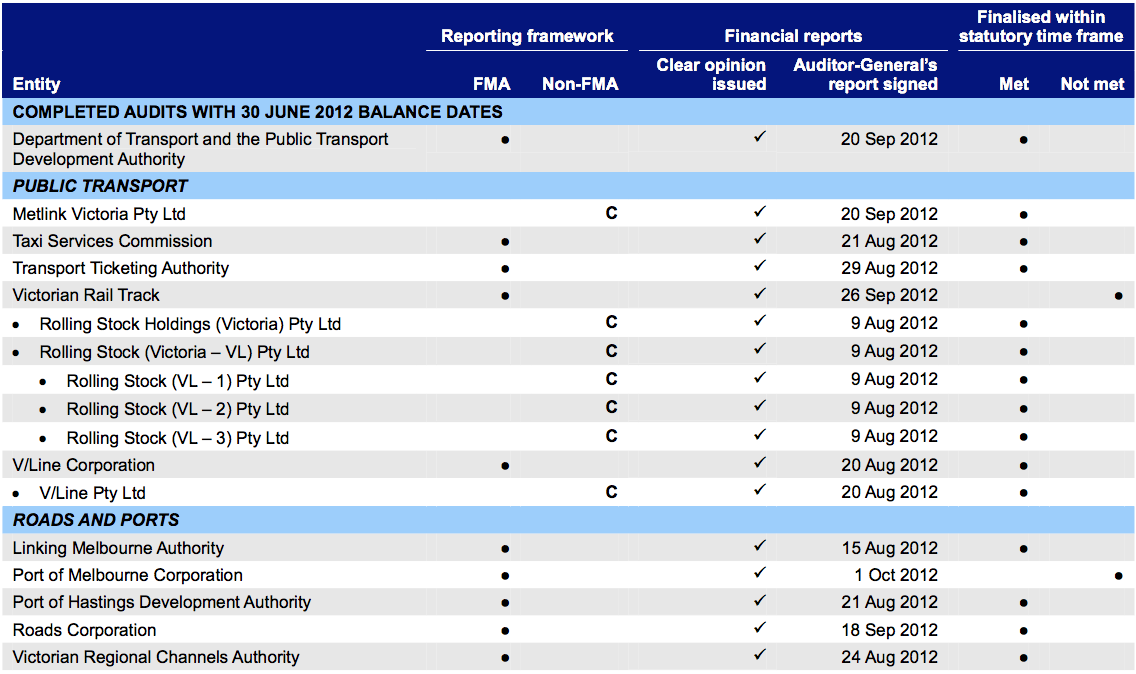

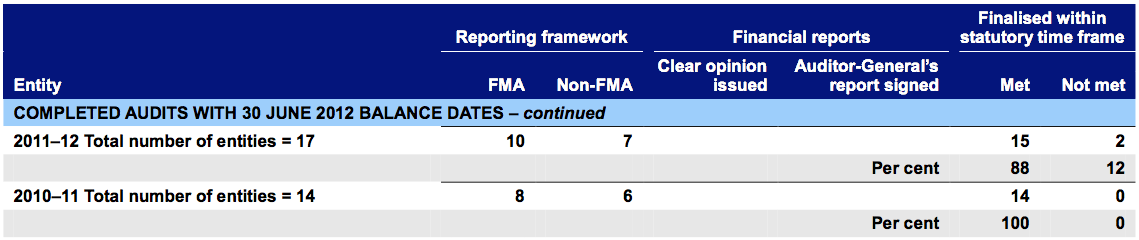

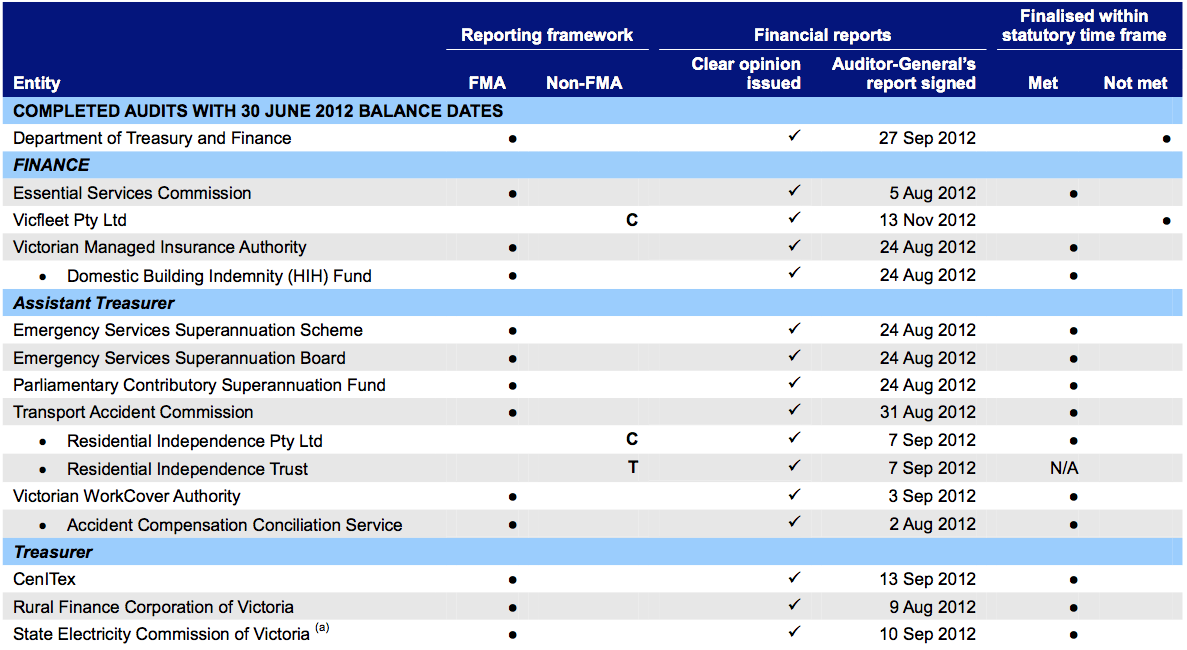

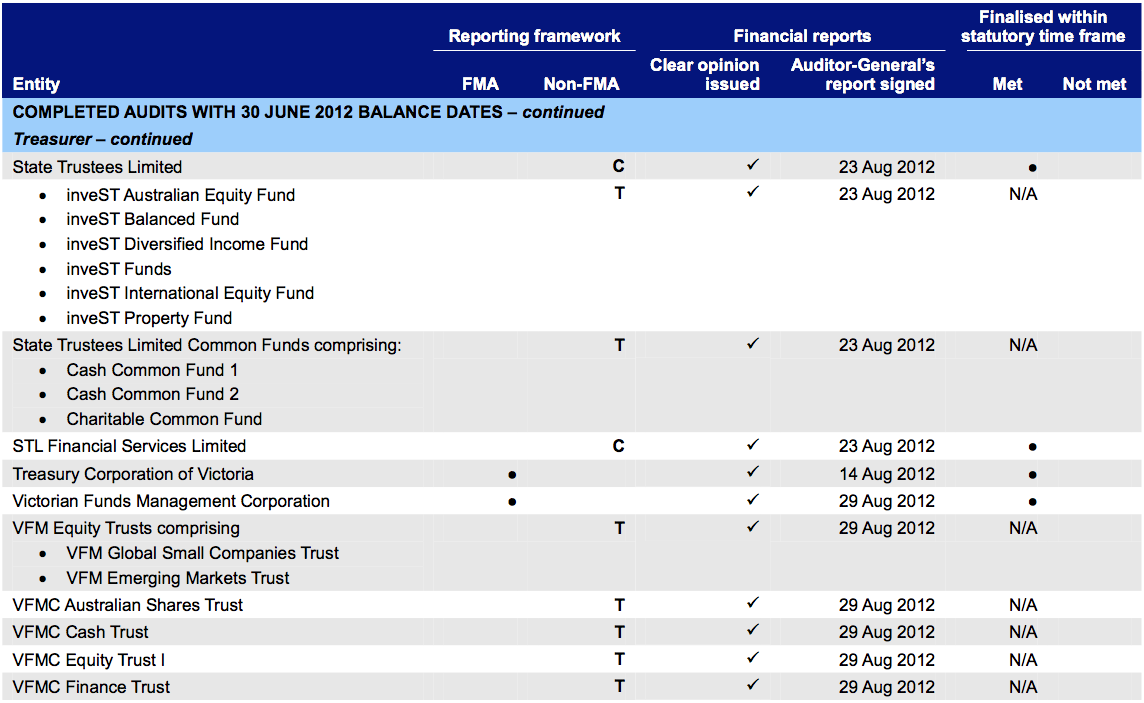

Independent audit opinions add credibility to financial reports by providing reasonable assurance that the information reported is reliable. This Part covers the results of the 2011–12 audits of the 11 portfolio departments and 193 associated entities that had finalised their financial reports at the time of this report.

Conclusion

No qualified audit opinions were issued for 2011–12. The quality of financial reporting to Parliament is constrained by the narrow definitions within financial reporting directions relating to disclosure of responsible person and executive officer remuneration, and ex gratia payments.

Findings

- In the public sector, the disclosure of responsible persons’ and executive officers’ remuneration is less than is required in the private sector. This limits transparency in a sensitive area of public spending and is not in the public interest.

- Disclosure requirements for ex gratia payments are minimal and allow entities significant discretion in reporting the nature and reasons for ex gratia payments.

Recommendations

The Department of Treasury and Finance should:

- revise Financial Reporting Direction (FRD) 21B to align the disclosure of remuneration of responsible persons and executive officers with Australian Accounting Standards for private sector entities

- revise FRD 11 to mandate meaningful disclosure of the nature, purpose and amount of ex gratia payments made by public sector entities.

2.1 Introduction

This Part comments on the results of the audits of the 11 portfolio departments and 193 associated entities that had finalised their 2011–12 financial reports at the time this report was prepared.

2.2 Conclusion

As no qualified audit opinions were issued, portfolio departments and associated entities are to be commended on the quality of financial reporting achieved in 2011–12. However, the quality of reporting to Parliament would improve if the disclosure of responsible person and executive officer remuneration was aligned with the requirements for private sector bodies under the Australian Accounting Standards, and if more details of the nature and circumstances of ex gratia payments were provided.

2.3 Reliability

2.3.1 Audit opinions

Independent audit opinions add credibility to financial reports by providing assurance that the information is reliable. A clear audit opinion confirms that the financial report has been prepared according to the requirements of relevant accounting standards and legislation.

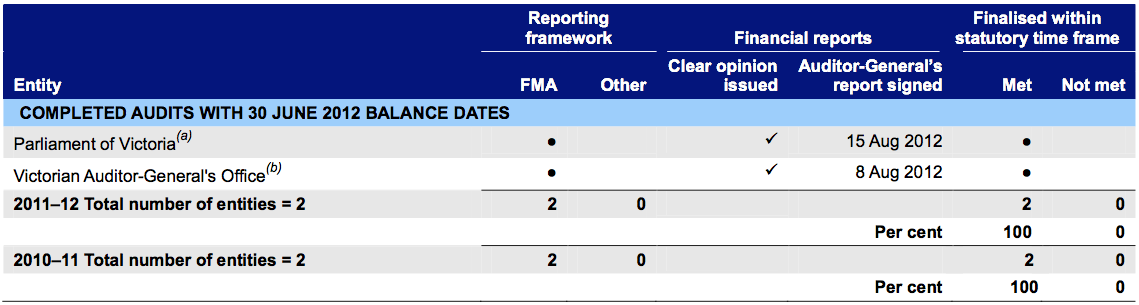

At the date of preparation of this report, 204 audit opinions on financial reports had been issued, all with clear opinions.

Emphasis of matter

An auditor can draw a reader’s attention to a matter or disclosure in the financial statements that provides important context. This is not a qualification and is known as an ‘emphasis of matter’.

Three entities received an auditor’s report containing an emphasis of matter for 2011–12, compared with five in 2010–11. Figure 2A lists the entities and the reasons for the emphases.

Figure

2A

Opinions with emphasis of matter paragraphs, 2011–12

Entity |

Reason |

|---|---|

Department of Transport and Public Transport Development Authority |

The emphasis of matter drew the reader’s attention to the fact the financial report was a composite report that included the financial results and positions of both entities. |

Metlink Victoria Pty Ltd |

The financial statements were prepared on a basis to reflect the orderly winding up of the company. The emphasis of matter drew the reader’s attention to the fact that the going concern basis was not appropriate for the preparation of the financial statements for the period ended 21 June 2012. |

VicFleet Pty Ltd |

The financial statements were prepared on a basis to reflect the orderly winding up of the company. The emphasis of matter drew the reader’s attention to the fact that the going concern basis was not appropriate for the preparation of the financial statements for the period ending 30 June 2012. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Other matter

Where an entity’s auditor has changed, auditing standards allow for the current year’s audit opinion to include an ‘other matter’ paragraph that discloses this to aid users’ understanding of the financial report.

The financial report of Metlink Victoria Pty Ltd for the year ended 30 June 2011 was not audited by the Auditor-General, as the company was not a public body. Therefore, the audit opinion for Metlink Victoria Pty Ltd for 21 June 2012 disclosed this as an ‘other matter’.

2.4 Audits by invitation

Under section 16G of the Audit Act 1994, the Auditor-General can accept an invitation to conduct the financial audit of an entity that is not an ‘authority' under the Act. An entity that does not meet the definition of an authority is not required to have the Auditor‑General conduct its financial audit.

Before accepting such an engagement the Auditor-General must be satisfied that the person or body exists for a public purpose, and that it is practicable and in the public interest for the Auditor-General to conduct the audit.

The Auditor-General conducted financial audits of four entities by invitation in 2011–12:

- Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency

- Parliament of Victoria

- Senior Master of the Supreme Court

- VCAMM Limited.

When conducting financial audits under section 16G, the Auditor-General is precluded from considering issues of waste, probity and lack of financial prudence. These considerations are a requirement of all other financial audits conducted by the Auditor‑General, and are a generally expected focus of public sector audit.

For 2011–12, the opinions issued for audits conducted under section 16G show that no consideration was given to matters relating to waste, probity and lack of financial prudence in the conduct of the audits. This made clear to the users that such issues were not considered and, if identified, were not reported to Parliament.

2.5 Disclosure by public sector entities

Portfolio departments and public bodies prepare financial reports in accordance with Australian Accounting Standards and the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA). While the accounting standards are primarily written for the private sector, the public sector is also required to comply with the standards in most instances. But, in some specific areas the accounting standards explicitly exclude public sector not‑for-profit entities from the requirement to comply.

In such cases, in order to fill the reporting gap and to enhance the consistency of disclosures in the financial reports of public sector entities, the Minister for Finance may elect to issue financial reporting directions (FRD) under the FMA with which public sector not‑for-profit entities must comply.

Where FRDs provide interpretations of terminology narrower than those in the accounting standards, or provide for entities to exercise discretion in what and how much they disclose, the impact is to limit the disclosures made by public sector entities, and is therefore inconsistent with reporting in the public interest.

2.5.1 Transparency of reporting of responsible person and executive officer remuneration

In the case of responsible person and executive officer remuneration, ‘for‑profit’ reporting entities make disclosures in accordance with Australian Accounting Standard AASB 124 Related Party Disclosures (AASB 124). However, not-for-profit public sector entities, including portfolio departments and most public bodies, are not required to apply AASB 124 to their reporting.

AASB 124 requires an entity to disclose all forms of consideration paid, payable or provided by the entity, or on behalf of the entity, in exchange for services rendered to the entity by responsible persons and executive officers. This includes payments of:

- short-term employee benefits

- post-employment benefits such as pensions, retirement benefits, life insurance and medical care

- other long-term employee benefits

- termination benefits

- share-based payments.

FRD 21B Disclosures of Responsible Persons, Executive Officers and other Personnel in the Financial Report (FRD 21B) defines a responsible person's or executive officer’s remuneration as the ‘remuneration package and includes any money, consideration or benefit received or receivable by the person as a responsible person or executive officer’. This narrow definition restricts the disclosure of responsible person and executive officer remuneration to payments included in their remuneration package. Additional payments made outside their remuneration package, such as termination benefits or post-employment benefits, are not required to be disclosed separately in the entity’s financial report.

In 2011–12, compliance with FRD 21B enabled three public sector bodies, including one portfolio department, to disclose limited information only relating to post‑employment benefits paid to former responsible persons. The narrow interpretation in the FRD meant that substantial payments made to these individuals were afforded far less disclosure than would have been required of a for‑profit or private sector entity. The limited disclosure made by the not-for-profit entities, while compliant with the FRD, was not in the public interest.

The Australian Accounting Standards Board is considering expanding the application of AASB 124 to not-for-profit entities, which would address the current reporting and disclosure gap. However, until not-for-profit entities are required to comply with AASB124, or FRD 21B is changed to mirror the requirements of the accounting standard, the potential remains for large payments to be made to responsible persons or executive officers outside the terms of their remuneration packages with limited or no disclosure.

2.5.2 Transparency of reporting of ex gratia payments

During 2011–12 a significant payout was made to an individual leaving the employment of a public sector entity. In this case, as the individual was not the responsible officer of the entity, FRD 21B did not apply. The associated portfolio department deemed the payment to be ex gratia in nature and reported it as such in the department’s financial statements.

Where a public sector entity makes a payment in addition to an entitlement or a legal obligation, that payment is required to be disclosed under FRD 11 Disclosure of Ex‑gratia Payments (FRD 11) as an ex gratia payment in the entity’s financial report. However, the disclosures required under FRD 11 are minimal, and there is limited guidance as to what should be disclosed.

In consequence, disclosure of details and circumstances of ex gratia payments made to individuals, to both Parliament and the public is limited and also results in inconsistent disclosures across the public sector, as entities are able to exercise significant discretion over what they choose to disclose.

Recommendation

-

The Department of Treasury and Finance should:

- revise Financial Reporting Direction (FRD) 21B to align the disclosure of remuneration of responsible persons and executive officers with Australian Accounting Standards for private sector entities

- revise FRD 11 to mandate meaningful disclosure of the nature, purpose and amount of ex gratia payments made by public sector entities.

3 Financial sustainability

At a glance

Background

Financially sustainable entities have the capacity to meet current and future expenditure, and absorb foreseeable changes and risks without significantly changing their revenue and expenditure policies. This Part presents the result of our financial sustainability assessments of the 46 self-funded state entities at 30 June 2012. The assessment is based on four financial sustainability indicators that consider both short-term and long-term sustainability.

Conclusion

The financial sustainability assessment outcome for self-funded entities has not changed from previous years. Self-funded entities still face challenges in generating sufficient cash flows to replace assets over the long term.

Findings

- Thirteen entities were rated as a high financial sustainability risk, and a further 16 were rated as medium risk at 30 June 2012. These results are consistent with the previous financial year.

- The long-term financial ratios of self-financing and capital replacement indicate that entities are not generating enough funds to invest in or maintain their assets.

Recommendation

The implications of the financial sustainability challenges for the accountability of boards, councils and trusts should be reviewed, and a strategy to address them developed.

3.1 Introduction

In this Part we provide insight into the financial sustainability of the 46 self-funded entities that mainly generate their own revenue rather than depend upon government funding.

The 11 portfolio departments and 147 other entities are excluded from the assessment as they are predominantly funded through the State Budget or have developed and already separately reported on sustainability indicators.

The objective of self-funded entities should be to generate a sufficient surplus from operations to meet their financial obligations, and fund asset replacement and new asset acquisitions. The ability of self-funded entities to do this depends largely on their expenditure management and revenue maximisation practices, which is reflected in the composition and rate of change of their operating revenue and expenses.

3.2 Financial sustainability

By analysing four core indicators over a five-year period, we provide insight into the financial sustainability of the self-funded entities. The indicators are:

- underlying result

- liquidity

- self-financing

- capital replacement.

The indicators reflect each entity’s funding and expenditure policies, and indicate whether the policies are sustainable.

Financial sustainability should be viewed from both a short- and long-term perspective. The short-term indicators—in this case, underlying result and liquidity—measure an entity’s ability to maintain a positive operating cash flow and adequate cash holdings, and to generate an operating surplus over time.

The long-term indicators—self-financing and capital replacement—signify whether adequate funding is available, and whether it is being spent on asset renewal to maintain the quality of service delivery, and to help meet community expectations and the demand for services.

Appendix C describes the sustainability indicators and risk assessment criteria we use in this report.

3.3 Financial sustainability risk assessment results

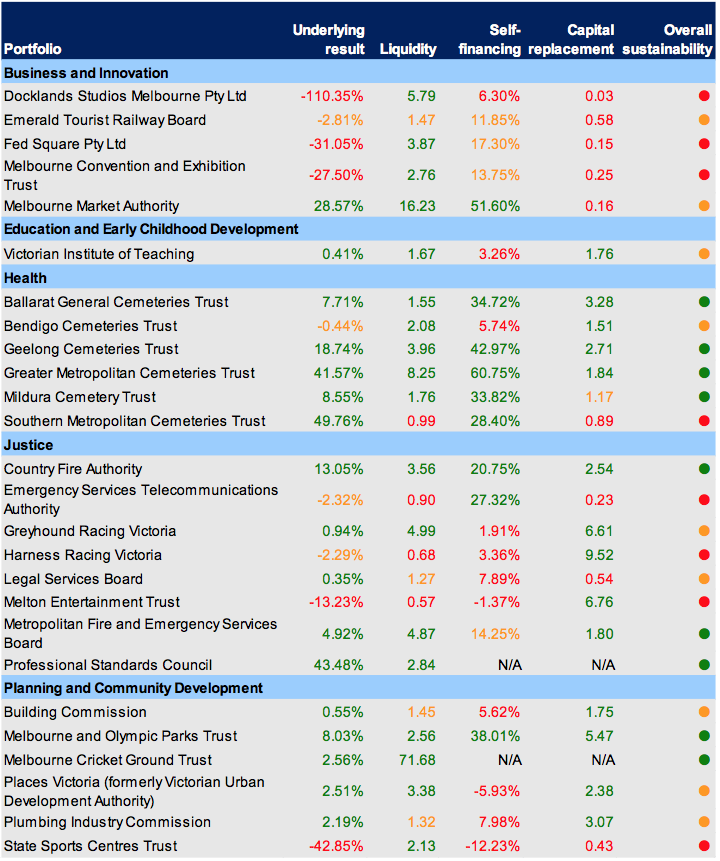

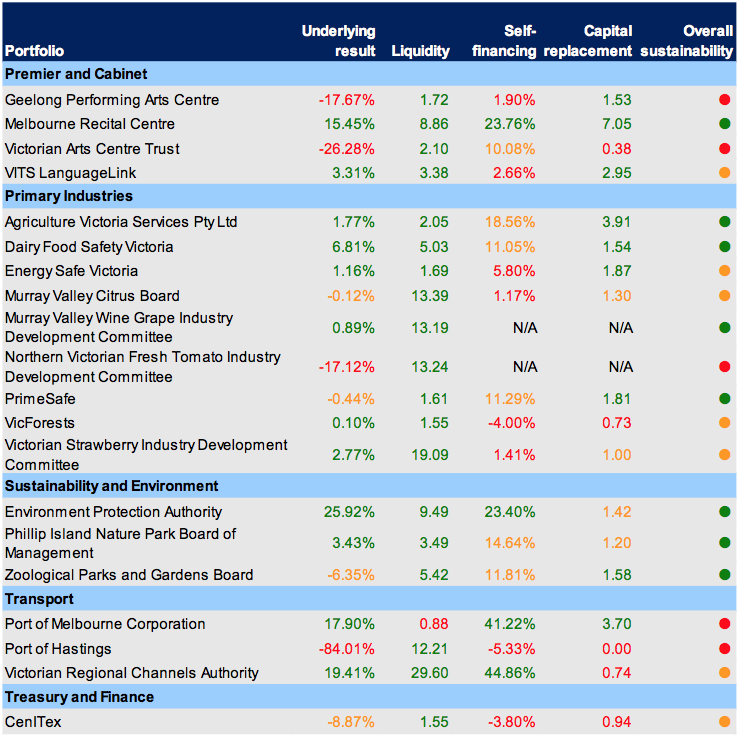

The five-year average financial sustainability results for the 46 self-funded entities are shown by portfolio in Figure 3A.

Figure 3A

Five-year average financial sustainability risk assessments for self-funded entities, at 30 June 2012

Figure 3A

Five-year average financial sustainability risk assessments for self-funded entities, at 30 June 2012, continued

Note: Legend: Red = high risk; Amber = medium risk; Green = low risk.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Only a third of the 46 entities were assessed as being financially sustainable overall. This was consistent with the five-year average assessments for the last two financial years. As the short-term indicators are generally positive, the overall result suggests that action to address the capital replacement challenge facing most of the 46 entities has been insufficient.

The longer-term ratios are still the most challenging, with the self-financing indicator showing 19 entities generating insufficient cash from operations to fund new assets or asset renewal, with a further 10 at risk. This is consistent with last year, when 23 entities were rated high risk in this aspect, and 13 at medium risk.

The condition of assets may deteriorate in the 14 entities flagged as not investing enough to renew assets, with a further five entities at risk. Failure to maintain assets may affect an entity’s ability to operate in the longer term. These entities may need to rely more on the state for funds to address asset maintenance in the future.

Recommendation

- The implications of the financial sustainability challenges for the accountability of boards, councils and trusts should be reviewed, and a strategy to address them developed.

4 The appropriation framework

At a glance

Background

The general government sector is funded mainly through Parliamentary appropriations. This Part examines key aspects of the appropriation framework and the supporting policies, controls, governance and oversight.

Conclusion

Oversight of the appropriation framework by the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) needs strengthening to demonstrate that the purchaser-provider model is delivering its intended outcomes.

Findings

- It is not evident there are adverse consequences for under-delivery or non-delivery of funded outputs. While 99.97 per cent of appropriations were certified, 21.8 per cent of outputs were delivered below the output target, and 6.8per cent of outputs were not delivered.

- Notwithstanding that $1.4 billion of surpluses and unused depreciation funding has been accumulated and is available to provide additional services for the public and infrastructure, portfolio departments—other than the Department of Health—have no plans to use these reserves.

Recommendations

- The Department of Treasury and Finance should review the implementation of the appropriation framework to determine whether acquittal and approval procedures are delivering funding outcomes consistent with its aims.

- Portfolio departments should, in consultation with the Department of Treasury and Finance, include in their long- and short-term plans a clear link between the use of the accumulated state administration unit balances, and the provision of additional services to the public, and infrastructure, consistent with the model.

4.1 Introduction

The principal source of funding for the general government sector comes through appropriations. Most appropriations are disclosed in the State Budget, tabled in Parliament in May each year, and legislated in an annual Appropriation Act. In some cases special appropriations are made to allow portfolio departments to meet payments required by other Acts of Parliament such as the costs of Parliament and the judiciary.

In 2011–12, appropriations to the 11 portfolio departments totalled $39.2 billion.

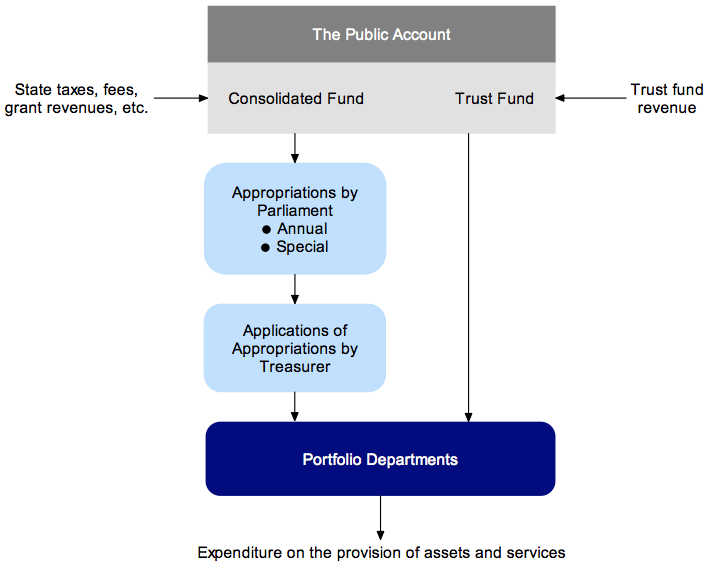

Portfolio departments access additional funding during the financial year through provisions within the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA). A summary of the financial framework is shown in Figure 4A.

Figure 4A

Victoria’s financial framework

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

This Part reports on the operation of key aspects of the appropriation framework and its supporting policies, controls, governance and oversight.

4.2 Conclusion

Oversight of the appropriation framework by the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) needs strengthening to demonstrate that the purchaser-provider model is delivering its intended outcomes. We observed that:

- performance against agreed targets and measures is not driving the disbursement of appropriations to portfolio departments

- with the exception of the Department of Health,there are no coherent plans to use the surpluses and unused depreciation funding that has been accumulated by portfolio departments

- there is not a clear definition to guide the making of Treasurer’s advances to meet the provisions of the Appropriation Act.

Portfolio departments account to DTF as to how they have earned their appropriations, as required. However, they need to plan more purposefully for, and use, all funding available to deliver more public services and infrastructure.

4.3 Appropriations

Appropriations to portfolio departments are disbursed under a purchaser‑provider model. Under the model, the Treasurer (the purchaser) purchases an agreed output from a portfolio department (the provider) for an agreed cost (the appropriation). The type and volume of outputs to be delivered in the coming financial year, and their cost, is recorded within the Appropriation Act, and the State Budget.

The purchaser-provider model is an accrual based model; it provides for portfolio departments to have their agreed appropriation revenue certified once they have demonstrated to the Treasurer that the agreed output has been delivered.

4.3.1 Central agency governance and oversight

DTF is the central agency responsible for the governance and oversight of appropriations. DTF’s role includes analysing and assessing the satisfactory delivery of outputs on behalf of the Treasurer. To support DTF in this role, portfolio departments make biannual submissions on the outputs achieved against agreed targets detailed in the State Budget.

At 31 December and 30 June of each financial year to which an appropriation applies, portfolio departments are required to submit to DTF a certification of the outputs delivered during the six-month period. DTF analyses each portfolio department’s submission and makes an assessment of whether, for each output group, the department is:

- on track to deliver the agreed outputs

- delivering outputs, but below the agreed performance levels

- at risk of not delivering the agreed outputs.

Based on the assessment, DTF makes a recommendation for the year ending 30 June to the Treasurer to certify part or all of the appropriation applicable to the period.

We reviewed portfolio department submissions to DTF for the year ending 30 June 2012, and found that DTF’s assessment was that:

- 71.4 per cent of output groups across the 11 portfolio departments were being delivered to target

- 21.8 per cent of output groups were delivered, but below target

- 6.8 per cent of output groups were not delivered.

Where the output groups are not delivered to target, DTF can recommend to the Treasurer action that can be taken to address this and to assist in performance improvement.

Notwithstanding this, DTF recommended to the Treasurer that 99.97 per cent of appropriations be certified. It was recommended that the Department of Transport did not receive the full appropriation requested, with $9.5 million not approved due to issues with metropolitan franchise operator incentive payments. Accordingly, the Treasurer certified 99.97 per cent of the appropriations requested by portfolio departments for the year. The total value awarded was $36.4 billion. Under the purchaser-provider model, portfolio departments should receive their appropriations only when they have delivered the outputs to the standard or quality agreed in the State Budget. By awarding the full amount to portfolio departments, regardless of the outputs achieved, it is not evident the purchaser-provider model is being used to drive effective and efficient delivery of outputs. There is little effective response when agreed outputs are not delivered.

Based on DTF’s assessment of portfolio department submissions for the period to 30 June 2012, $2.4 billion of the $36.4 billion was awarded for outputs where performance indicators were not delivered.

4.3.2 Management practices at portfolio departments

To enable their achievements to be assessed and to determine the level of appropriation to be certified, all portfolio departments provide to DTF:

- a request for appropriation monies representing the value of outputs delivered during the period

- an output performance report detailing achievements against each output target for the period

- significant risks the department faces of not achieving output targets for the remainder of the financial year.

All portfolio departments provided the requested information for both the 30 December 2011 and the 30 June 2012 analysis to DTF in a complete and timely manner. However, the accuracy of the information provided needs to be improved. Errors progressively identified during audit resulted in the Treasurer having to sign the appropriations approval certification for the year three times instead of once.

4.4 The state administration unit

To accurately report the balance of appropriations certified as earned, but which were not spent, in delivering outputs under the purchaser-provider model, portfolio departments record a receivable in their annual financial statements. The receivable is reported as ‘Amounts owing from the Victorian Government’ and is referred to operationally as the state administration unit (SAU).

The balances held in the SAU for each department have three key components, as detailed in Figure 4B.

Figure 4B

Key components of the state administration unit

|

Component |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Surpluses earned from the provision of outputs |

Financial surpluses accruing to departments due to outputs being delivered for a lower cost than the revenue appropriated from the Consolidated Fund. Surpluses can only be used to fund additional initiatives with the Treasurer’s prior approval. |

|

Depreciation funding not yet spent on assets |

Appropriations received, equivalent to actual depreciation expenses incurred by departments in delivering outputs, but not yet spent on asset replacement and/or acquisition. |

|

Appropriation accruals |

Appropriation not drawn down yet to pay creditors, employee entitlements and other amounts payable by departments. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Budget and Financial Management Guidelines, Department of Treasury and Finance (2007).

4.4.1 Funds held in the state administration unit

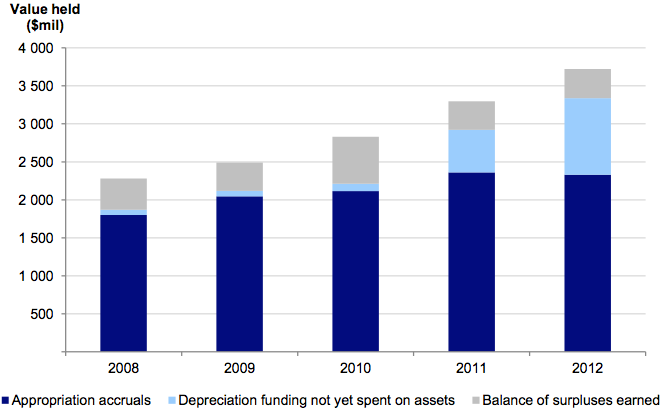

The total value of the SAU receivable by portfolio departments increased by 63.1 per cent over the last five financial years, and has increased year-on-year during that period. At 30 June 2012, the 11 portfolio departments reported a total of $3.7 billion as SAU receivables in their financial statements. The balance held by the 11 portfolio departments for each of the past five years is shown in Figure 4C.

Figure 4C

Amounts owing from the Victorian Government to portfolio departments at 30 June

|

Department |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Business and Innovation |

68.9 |

87.2 |

106.9 |

72.6 |

84.7 |

|

Education and Early Childhood Development |

706.6 |

789.0 |

895.5 |

1 120.3 |

1 099.5 |

|

Health |

N/A |

N/A |

379.4 |

696.0 |

925.9 |

|

Human Services |

333.9 |

318.5 |

92.9 |

176.9 |

213.7 |

|

Justice |

225.0 |

248.9 |

250.8 |

237.4 |

266.9 |

|

Planning and Community Development |

72.0 |

60.3 |

55.9 |

61.7 |

49.1 |

|

Premier and Cabinet |

50.5 |

84.0 |

89.1 |

93.7 |

121.5 |

|

Primary Industries |

105.1 |

105.0 |

119.7 |

97.6 |

86.6 |

|

Sustainability and Environment |

184.9 |

271.5 |

190.6 |

172.9 |

158.2 |

|

Transport |

443.4 |

438.9 |

544.0 |

472.2 |

610.8 |

|

Treasury and Finance |

90.1 |

87.7 |

104.5 |

96.0 |

102.7 |

|

Total |

2 280.4 |

2 491.0 |

2 829.3 |

3 297.3 |

3 719.6 |

Note: The Department of Health was formed in August 2008 when its functions were moved out of the Department of Human Services.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

4.4.2 Management practices at portfolio departments

As at 30 June 2012, $2.3 billion of the $3.7 billion SAU receivable (62.2 per cent) related to accruals such as employee entitlements and payables. These monies are committed to be spent when payments to the creditors to which they relate are required. Portfolio departments have little discretion over the use of these amounts.

The remaining $1.4 billion SAU receivable is available to portfolio departments with the approval of the Treasurer. Under the purchaser-provider model, portfolio departments that achieve efficiencies and deliver surpluses may apply to the Treasurer to use the money to deliver additional public services and infrastructure. Almost half of the $1.4 billion ($668 million) was held by the Department of Health (DH). DH plans to use these funds for the health sector capital program over the next few years, subject to government approval in future state budgets. However, none of the 10 remaining portfolio departments had plans to use the remainder of their SAU funds.

Approval processes

Line management in portfolio departments stated that a key impediment to using the SAU receivables, and therefore planning for their use, is that the money can only be spent with the Treasurer’s approval.

The FMA provides for comprehensive checks so that portfolio departments have access to SAU receivables only when the money is legally available to be spent. This is important, and controls the need to provide adequate assurance to Parliament, as this money is spent outside the current year’s Appropriation Act. If not adequately controlled, the funds could be spent for purposes inconsistent with government policy outcomes or without proper accountability or transparency.

However, oversight arrangements should not hinder portfolio departments from planning and delivering additional public services or infrastructure for legitimate purposes, as the framework intends.

4.4.3 Governance and oversight

The government has an obligation to pay the SAU receivables to portfolio departments. It also has a responsibility to maintain effective oversight of SAU balances. This role is undertaken on its behalf by DTF.

DTF receives quarterly SAU reconciliations from each portfolio department and confirms that it agrees with information held centrally. Responsibility for the accuracy of the quarterly reconciliations rests with chief finance officers of portfolio departments.

The oversight exercised by DTF is sufficient to give comfort on the accuracy of the SAU figures. While there is a budget process in place that considers the long- and short-term plans of the portfolio departments, this does not provide a clear link between expenditure of the SAU balance and the provision of additional services and infrastructure. This reduces DTF’s ability to plan the cash flow it requires to have available at any time to meet requests for funds by portfolio departments.

Portfolio departments regularly review their individual SAU balances to identify and correct errors, and to maintain oversight of the receivable. We observed that this occurred in each portfolio department at least quarterly.

Capping of the SAU

Our 2003 report, Parliamentary control and management of appropriations, recommended that the SAU be capped to manage its growth and the corresponding drawdown of cash from the Consolidated Fund.

A cap has not been introduced and the SAU receivable has continued to grow. Figure 4D breaks down the growth of the SAU balance across the three key components over the past five years.

Figure 4D

State administration unit receivable held by portfolio departments at 30 June

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The largest areas of growth are in the components that can be used by portfolio departments to deliver additional services or infrastructure—depreciation funding not yet spent, and the balance of surpluses earned. Given the trend to date, unless action is taken to use these funds, or to establish a cap, the growth in the SAU balances will likely continue.

This growth poses a problem for government, as its obligation to service the receivable is also growing. At 30 June 2012, the SAU payable by the government to portfolio departments was $3.7 billion, compared to a general government sector cash balance of $433 million held in the Consolidated Fund. This shows that there was not enough money in the bank to fund the SAU payable at 30 June 2012 if all portfolio departments were to seek their money.

4.5 Treasurer’s advances

Under the Appropriation Act, the Treasurer has available to him a pool of funds to meet urgent expense claims. This is because appropriations to portfolio departments and entities are set in the budget, well in advance of the financial year and unforeseen circumstances that require additional expenditure inevitably arise during each year.

The Appropriation Act 2011–12 sets aside $779 million as an ‘Advance to Treasurer to enable Treasurer to meet urgent claims that may arise before Parliamentary sanction is obtained, which will afterwards be submitted for Parliamentary authority’ during the financial year. These payments are commonly referred to as a Treasurer’s advance (TA). A disclosure of the money actually provided through these advances was included in the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria, 2011–12, provided to Parliament on 15 October 2012.

4.5.1 The value of Treasurer’s advances

The number and value of TAs varies year-on-year because, by their nature, they are for urgent items not foreseen in the budget. In 2011–12, the Treasurer approved 48 TAs totalling $776 million.

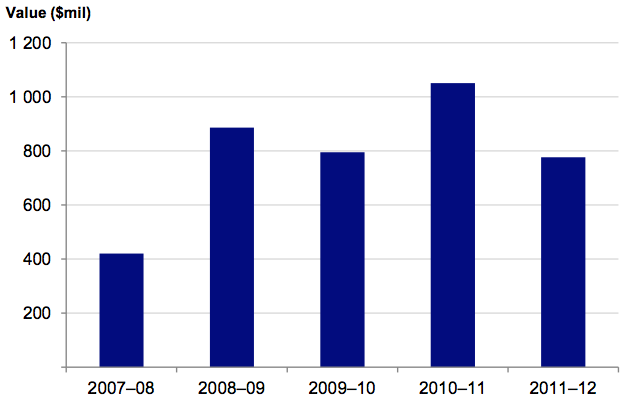

Figure 4E shows the aggregate of TAs awarded across the 11 portfolio departments over each of the past five years.

Figure 4E

Value of Treasurer’s advances approved, 2007–08 to 2011–12

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The value of TAs awarded peaked in 2008–09 and 2010–11. This coincided with two natural disaster events:

- the bushfires in February 2009

- the floods in September 2010 and January/February 2011.

The 2010–11 TA value also includes money for the implementation of the recommendations of the Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission.

4.5.2 Central agency governance and oversight

DTF receives TA requests from portfolio departments and is responsible for analysing the validity of the request, and making a recommendation to the Treasurer.

To properly assess the validity of a TA request, the definition of ‘urgent’ should be clear and a set of criteria relevant to the purpose for TAs developed and documented. This would provide greater assurance that funds allocated meet the purpose of TAs established under the Appropriation Act.

In practice, there is no definition of ‘urgent’. The criterion that DTF applies to TA requests is that applications should only be made ‘where a department has exhausted, or is close to exhausting, all available legal sources of funding’.

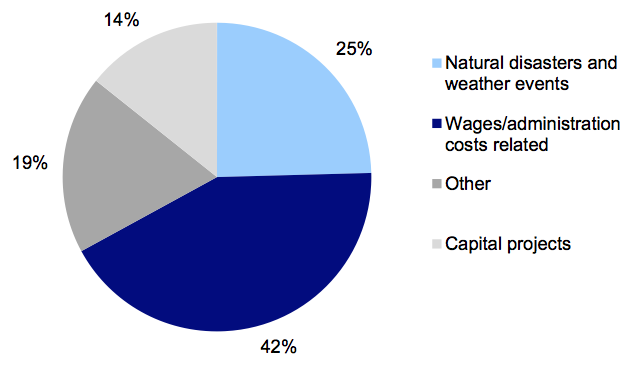

We analysed the nature of expenditure approved under TAs over the past five years and the results are shown in Figure 4F.

Figure 4F

Treasurer’s advances per expenditure type as a percentage of all Treasurer’s advances, 2007–08 to 2011–12

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Figure 4F shows that 25 per cent of the value of TAs was for expenditure relating to natural disasters. Based on the definition of ‘urgent’ as something that calls for immediate attention this would clearly be considered urgent expenditure and therefore fit the intention of the Appropriation Act.

However, 42 per cent of TAs went to wages, depreciation, administration costs and other expenditure within portfolio departments. A further 14 per cent related to capital projects. These expenses do not clearly present as ‘urgent’. It is not evident why they were unforeseen, or were not met from appropriated recurrent or capital funding or specific project funding.

An example of the way TAs have been used to provide non-urgent funding to one portfolio department is shown in Figure 4G.

Figure 4G

Case study – Education sector enrolment-based funding

Enrolment-based funding is a funding component for Victoria’s Tertiary and Further Education Institutes (TAFEs) and adult and community further education, schools and kindergartens. It is calculated each financial year based on the number of enrolled students in such education institutions. Variations in pupil numbers between schools and school years make the exact amount of funding required difficult to predict.

Since 2008–09, enrolment-based funding provided for these institutions to the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) through appropriation has been supplemented through TAs to cover the difference between the amount appropriated and the actual funding required. The value of TAs awarded by type of educational institution for each year is shown below.

|

Educational institution |

2008–09 |

2009–10 |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kindergartens |

8.0 |

6.0 |

0.5 |

10.5 |

|

Schools |

– |

35.7 |

38.9 |

51.7 |

|

TAFEs, adult, community and further education |

– |

– |

150.0 |

459.8 |

|

Total |

8.0 |

41.7 |

189.4 |

522.0 |

Enrolment-based funding is an annual expenditure item for DEECD. It should be capable of being forecast with reasonable accuracy. Where the forecast falls short, an agreement between DEECD and DTF allows for the difference to be made up by TAs or an alternative funding source.

The year on year requirement to source additional funds through TAs raises concerns with the method for calculating the budget figures.

In using TAs to make up the funding shortfall, TAs are being used as an additional funding source, not for urgent expenditure.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

This example and our analysis of other documentation suggests that TAs are used by portfolio departments as an alternative source of funding.

While we acknowledge that portfolio departments may experience difficulty and inconvenience in continuing their day-to-day operations when funding is short, it is not evident that the imminent exhaustion of a department’s appropriation or available funding, or the inability to predict funding needs accurately, constitutes ‘urgency’. Providing funding for the normal operations of a portfolio department over and above its annual or special appropriations could be seen to reward ineffective resource management and poor performance. Furthermore, awarding TAs for non‑urgent items means that the level of funds available for the state to respond to genuine urgent events in a timely manner is reduced.

The Treasurer, and DTF as the central agency, should work with portfolio departments so that only TA requests which meet the generally accepted definition of urgent are approved.

Recommendations

- The Department of Treasury and Finance should review the implementation of the appropriation framework to determine whether acquittal and approval procedures are delivering funding outcomes consistent with its aims.

- Portfolio departments should, in consultation with the Department of Treasury and Finance, include in their long- and short-term plans a clear link between the use of the accumulated state administration unit balances, and the provision of additional services to the public, and infrastructure, consistent with the model.

- The Department of Treasury and Finance should adopt a definition of urgent that would mean that Treasurer’s advances are awarded only for purposes consistent with the Appropriation Act.

5 Trust funds

At a glance

Background

Trust funds are discrete accounts that receive and distribute money for designated purposes. At 30 June 2012, the state had 111 trust funds that collectively held $2.7 billion. This Part reports on our review of key aspects of the controls, governance, oversight and reporting of trust funds.

Conclusion

The number of trusts, and the total money held in each, is growing. However, there is minimal disclosure, and a lack of policies and guidelines to support their use. No recent assessments have been performed to as to whether trust funds are being used as intended and that they are aligned with government objectives.

Findings

- There is evidence that Treasury trust funds are not being used as intended.

- There is no evidence that the working trust operated by the Department of Business and Innovation is legally established.

- With one exception, portfolio departments and the Department of Treasury and Finance (on behalf of the Minister for Finance), could not demonstrate they periodically reviewed the nature and purpose of each trust fund to confirm its relevance and alignment with the strategic objectives of government.

- The purpose for each trust, and the amounts paid into and out of it annually, is not publicly reported.

Recommendations

- The Department of Treasury and Finance should:

- review every treasury trust fund to determine whether it is being used as intended, and address noncompliance as necessary

- review its trust fund guidelines for consistency with better practice.

- The Department of Business and Innovation should confirm its legal authority to operate its working trust or close the trust.

5.1 Introduction

Trust funds are discrete accounts established to record the receipt and disbursement of state funds for specified purposes. They can be set up under their own legislation or by the Minister for Finance under the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA). At that stage the trust’s purpose is established, and it is specified how its funds can be spent.

Each trust fund is assigned to one of the 11 portfolio departments. The portfolio department is responsible for reporting the balance of the trust within its audited financial statements. A high level report of all trust funds is also included in the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria prepared by the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) and tabled in the Parliament in October each year.

This Part reports on our review of key aspects of trust fund policies, controls and governance in place at portfolio departments and within DTF, the central oversight entity.

5.2 Conclusion

Portfolio departments lacked policies for controlling and monitoring trust funds, and the supporting guidelines issued by DTF, the central agency, were not current.

The number of trusts, and total money held in each, is growing year on year; however, DTF has not recently assessed whether trusts are being used as intended and are aligned with the priorities and strategic objectives of government.

Notwithstanding the significant funds held, and which flow in and out of the state’s 111 trust accounts annually, there is minimal disclosure to Parliament or the public about them.

5.3 Trust fund balances

As at 30 June 2012, the state had 111 trust funds with a combined value of $2.7 billion. A summary of where the trusts are held is shown by portfolio department in Figure 5A.

Figure 5A

Trust funds held by portfolio departments as at 30 June 2012

|

Department |

Number |

Value |

|---|---|---|

|

Business and Innovation |

6 |

23.5 |

|

Education and Early Childhood Development |

6 |

119.0 |

|

Health |

7 |

73.4 |

|

Human Services |

6 |

26.0 |

|

Justice |

19 |

495.8 |

|

Planning and Community Development |

12 |

323.2 |

|

Premier and Cabinet |

7 |

11.9 |

|

Primary Industries |

12 |

91.8 |

|

Sustainability and Environment |

20 |

260.7 |

|

Transport |

5 |

768.0 |

|

Treasury and Finance |

11 |

534.4 |

|

Total |

111 |

2 727.7 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

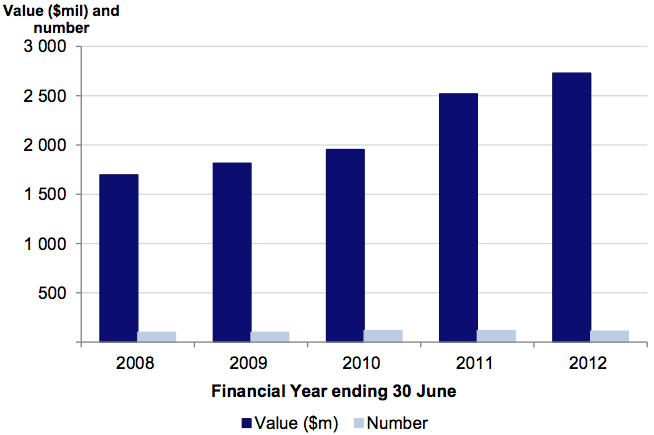

The value and number of trust funds has grown over the past five years. The value increased by 59 per cent, from $1.7 billion in 2008 to $2.7 billion in 2012. Over the same period the number of trust funds increased from 100 to 111. These are set out in Figure 5B.

Figure 5B

Value and number of trust funds held by portfolio departments 2007–08 to 2011–12

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The key drivers behind increases in the value of trust funds include:

- an increase in the amounts held for natural disaster relief from $6.4 million in 2008 to $462.6 million in 2012 due to the 2009 bushfires and 2010 floods

- growth in the Department of Transport’s Better Roads Trust Fund from $69.7million in 2008 to $476.2 million in 2012 due to more money being received from state appropriations for road projects including maintenance and vehicle registration. The balance of the trust fluctuates year on year in part due to the timing of Commonwealth funding for joint projects.

- an increase in amounts held in treasury trust funds at portfolio departments. These are discussed in further detail below.

5.3.1 Treasury trusts

Each portfolio department can operate a treasury trust, created under the FMA, to capture and record unclaimed and unidentified money. Across the 11 portfolio departments there were 13 treasury trust funds at 30 June 2012. Combined, they held $253 million, up from $152.9 million five years ago.

In practice, treasury trust funds hold more than unclaimed and unidentified monies and are no longer being used for the purpose for which they were intended. They were holding monies that would normally be paid into the Consolidated Fund and available for appropriation. In particular, there were examples where unspent grants and revenue from asset sales were held in treasury trust funds. In these cases decisions around future spending could be made at the discretion of the portfolio department rather than through the established appropriation process. This is inconsistent with the FMA and is a missed opportunity for the state to make strategic decisions around allocations and the most appropriate use of funds for the state as a whole.

We expected that DTF, on behalf of the Minister for Finance, would monitor the amounts held in treasury trusts and, consequently, would have identified the trend of increasing balances and transactions. If monitoring was occurring the trend should have prompted further investigation. However, there was no evidence of such monitoring or that any action had been taken to address the inappropriate use of treasury trusts.

5.3.2 Working trust funds

The FMA allows a portfolio department to establish a working trust fund into which agreed revenue received from delivering outputs can be placed. The Minister for Finance and the minister responsible for the portfolio department must agree on:

- the purpose and outputs for which money can be spent

- the conditions attached to the trust.

At 30 June 2012, five working trusts were in operation. The most significant was a Department of Business and Innovation (DBI) trust with a balance of $21.8 million. DBI was unable to produce evidence:

- to prove that the trust was legally established

- of an agreement between the Minister for Finance and the portfolio minister on the purpose, outputs and conditions attached to the trust.

Further, DTF had no record of DBI receiving authority to operate a working trust.

The trust is being used by DBI to set aside unspent appropriations on projects and programs which are incomplete or ongoing. This use is not consistent with the intended purpose of working trusts. Where appropriation funding remains unspent at the end of a financial year, there is provision under the FMA to carry it forward, subject to approval from the Treasurer. This is the appropriate way for DBI to manage its unspent appropriations and to increase transparency over the funds set aside.

5.4 Policies

Responsibility for managing individual trust funds rests with the respective portfolio departments. Portfolio departments should have approved policies and procedures to control and manage the funds held within, and moving in and out of, trust funds.

The departments of Planning and Community Development, Primary Industries and Sustainability and Environment (DSE) had tailored policies and guidelines that had been approved by their secretaries. The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development had a policy in draft.

The remaining seven portfolio departments did not have policies and relied on guidelines issued by DTF in 2007 for managing their trust funds. While the guidelines provide some foundation for portfolio departments, they have not been revised for five years and may not reflect better practice. They also warrant tailoring to address individual departmental circumstances.

5.5 Management practices

Portfolio departments play a pivotal role in collecting and recording details of all money paid into and moved out of their trust funds. They should also have controls so that all money paid out is used for purposes consistent with the designated purpose of their trusts.

A review of a sample of 129 special purpose trust fund receipts and 140 trust fund payments was conducted across the 11 portfolio departments during 2011–12. All payments tested had been made in accordance with the trust fund legislation or designated purpose. Furthermore, no exceptions were noted with the receipts tested.

5.6 Governance and oversight

As the objectives and goals of government change, it is prudent for portfolio departments and the Minister for Finance to review trust funds to determine whether they remain relevant and aligned with government objectives. At the same time, trust funds with stagnant balances should be reviewed, as this may indicate that a trust fund is no longer active or required, and the money should be transferred to the Consolidated Fund.

DTF, on behalf of the Minister for Finance, could not demonstrate that regular reviews of trust funds were undertaken to determine alignment with government objectives. Similarly, with one exception, portfolio departments had not routinely documented whether they had revisited the nature and purpose of their trust funds.

As an example, DSE operates a plant and machinery trust fund. The fund was established in 1987 to collect revenue from hiring out of equipment and to use that money to replace hired equipment. The trust had a balance of $46.6 million at 30 June 2012, up from $1.2 million five years ago. DSE could not provide plans about how the money in the trust is to be spent, whether it is still required for asset replacement, why the accumulation of funds has continued, or why such a large amount has been accumulated.

Notwithstanding the lack of reviews, we did not identify any stagnant trust funds. Of the 111 trust funds at 30 June 2012, only six had had the same balance for each of the past five financial years. A further 16 had the same balance for two consecutive financial years. However, each of the 22 had received income and made payments in each of the five financial years.

5.7 Reporting

Trust funds fall into two categories:

- Controlled trust funds: trust funds where the responsible portfolio department can make decisions about how the funds are used.

- Administered trust funds: trust funds for which decisions about how the funds are used are made outside the portfolio department. The department’s responsibility for these trust funds is limited to processing the trust’s receipts and payments.

Portfolio departments are required to report on both categories of trust funds within their audited financial statements. Controlled trust funds are reported in the operating statement and balance sheet of the portfolio department, and administered trust funds are reported as a year-end balance in the notes to a department’s financial statements.

At a minimum, portfolio departments are encouraged, through the DTF‑issued model financial statements, to report the following information about their trust funds:

- the name of the trust fund

- the closing balance at 30 June for the current and prior year

- details of any trust funds closed or opened during the current financial year.

Complete and accurate reporting of the nature and purpose of the trust fund, the transaction flows in and out, and balance at the end of the financial year can provide useful information to users of the financial statements. Currently, there is no requirement to report:

- the value of receipts received by each trust fund in the current financial year

- the value of payments made by each trust fund in the current financial year

- a description of the purpose of each trust fund.

The only portfolio department that provided some of the above listed additional information at 30 June 2012 was DBI. It detailed the receipts and payments made in the current financial year for each of its trust funds.

We were unable to ascertain the value of transactions handled through the remaining 105 trust funds during 2011–12. However, given the large amount of money held at 30 June 2012, we expect the quantum of inflows and outflows would be significant.

As well as a lack of transparency over the payments into and out of trust funds, there is a lack of transparency around the nature and purpose of each trust, with only the name of a trust fund currently disclosed. In many instances the name of the fund provides little information to the reader of the accounts. For example, the DSE operates a Project Trust Fund. Its balance was $142.1 million at 30 June 2012. The name of the fund and the balance are reported in the audited financial statements of the portfolio department, however, this provides no meaningful indication to a reader about what project or projects the money is intended to fund.

Recommendations

- The Department of Treasury and Finance should:

- review every treasury trust fund to determine whether it is being used as intended, and address noncompliance as necessary

- review its trust fund guidelines for consistency with better practice.

- The Department of Business and Innovation should confirm its legal authority to operate its working trust or close the trust.

- The Department of Treasury and Finance and portfolio departments should periodically review the purpose and currency of trusts to assess alignment with changing government objectives.

- To better inform users of financial statements and provide greater transparency to the Parliament and the public, reporting requirements should be enhanced to require annual disclosure of the nature and purpose of each trust and the amount of its revenue and expenditure.

6 Risk management

At a glance

Background

Effective risk management is an important element of governance. In this Part we comment on risk management practices at the 11 portfolio departments against the Victorian Government Risk Management Framework and the international risk management standard.

Conclusion