Public Hospitals: Results of the 2010–11 Audits

Overview

This report covers the results of the financial audits of 112 entities within the public hospital sector, comprising 87 public hospitals and the 25 entities they control. It informs Parliament about significant issues arising from the audits and augments the assurance provided through audit opinions included in the entities’ annual reports.

The report recommends that public hospitals assess their policies and procedures against the commonly identified control weaknesses, and that comprehensive policies and procedures over procurement, tendering and information technology system security be developed and regularly reviewed.

Public Hospitals: Results of the 2010–11 Audits: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER November 2011

PP No 84, Session 2011–12

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on Public Hospitals: Results of the 2010–11 Audits.

Yours faithfully

![]()

D D R PEARSON

Auditor-General

9 November 2011

Audit summary

Background

This report covers the results of our financial audits of 112 entities within the public hospital sector, comprising 87 public hospitals and the 25 entities they control. It informs Parliament about significant issues arising from the audits and augments the assurance provided through audit opinions included in the entities’ annual reports.

This report comments on the quality and timeliness of financial reporting, the financial sustainability of public hospitals and the effectiveness of procurement practices and information technology security.

Conclusion

Clear audit opinions were issued on all completed public hospital and associated entities’ financial statements for the financial year ended 30 June 2011.

The operating result for hospitals improved significantly from a deficit of $156 million in 2009–10 to a deficit of $102 million in 2010–11, mainly due to additional capital grants provided to regional hospitals during the year.

The overall risk to financial sustainability for each public hospital category was assessed as moderate for 2010–11. However, the risk was assessed as high for 33 per cent of public hospitals (29 of 87) mainly because they generated insufficient cash to adequately fund their operations. It is concerning that 61 per cent of public hospitals, including 25 major metropolitan and regional hospitals, had cash holdings equivalent to less than 30 days operating cash outflows. Some hospitals had cash holdings of less than seven days

Twenty-nine public hospitals did not meet the going concern test of the Australian Accounting Standards at 30 June 2011. The 29 relied upon a letter of comfort from the Department of Health that stated it would provide adequate cash flows to enable them to meet their financial obligations if required.

The above data demonstrates that while public hospitals have their own boards of management that are responsible for the day-to-day oversight of the entities, the financial sustainability of hospitals is significantly affected by funding decisions made by the department. The current departmental funding model limits the ability of governing bodies and management to make decisions around asset maintenance and replacement. The funding arrangements have implications for governing boards of public hospitals and their ability to fulfil their legislative responsibilities.

Findings

Audit opinions and the quality of reporting

Clear audit opinions were issued on 111 entities, comprising the 87 public hospitals and 24 of the entities they controlled. The audit of one of the controlled entities was still to be finalised. The financial reports were prepared in accordance with the applicable reporting framework. This continued the positive result from 2009–10 when no modified audit opinions were issued.

Quality of reporting

Overall, the financial report preparation processes of public hospitals and their controlled entities were adequate and produced accurate, complete and reliable information, but there are opportunities for improvement in:

- establishing financial report preparation plans outlining the processes, resources, milestones and quality assurance practices required

- preparing and providing timely shell financial statements to enable issues to be identified and resolved earlier

- preparing materiality assessments to identify potential errors in the financial statements

- undertaking periodic compliance reviews to identify non-compliance or changes to legislation that impact the financial report.

The average time taken by public hospitals and their controlled entities to finalise their financial statements increased from 7.9 weeks in 2009–10 to 8 weeks in 2010–11. Although a slight increase, this result maintained the significant improvement on 2008–09 when it took an average of 10 weeks to finalise financial statements.

Financial sustainability

To be financially sustainable, public hospitals need to be able to meet current and future expenditure as it falls due. They must also be able to absorb foreseeable changes and financial risks as they materialise.

The five financial sustainability indicators, analysed for the five years from 2006–07 to 2010–11 were:

- the underlying result

- liquidity

- average days cash available

- self-financing

- capital replacement.

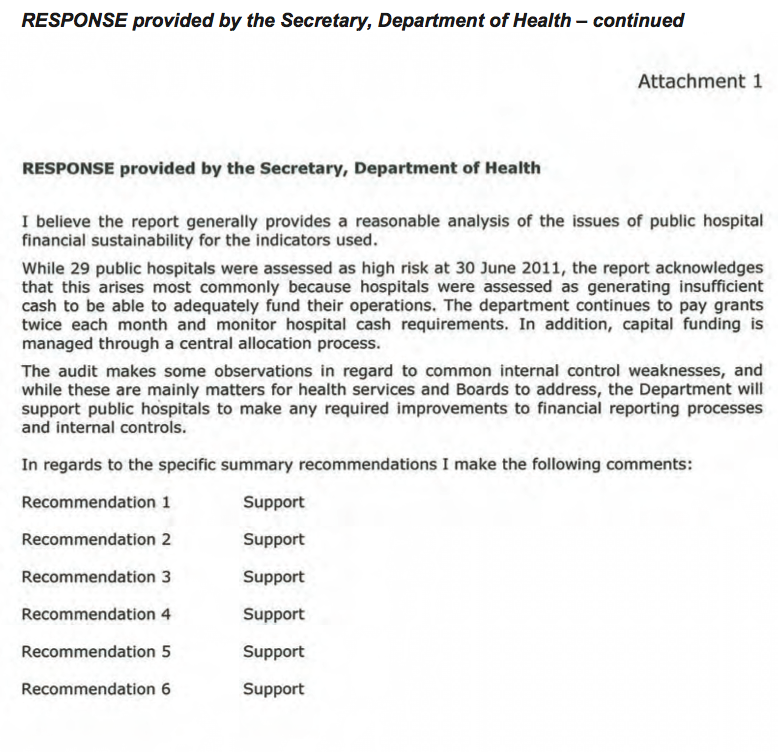

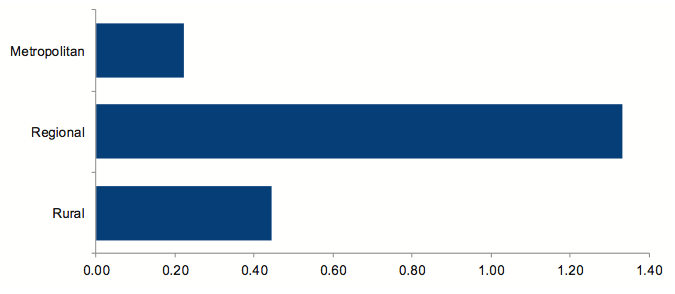

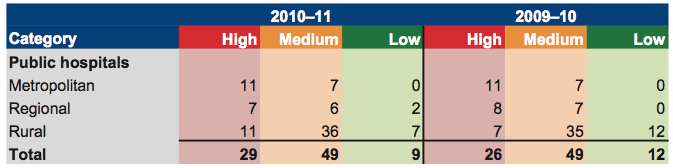

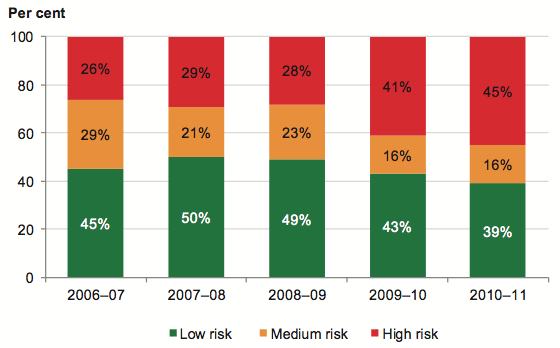

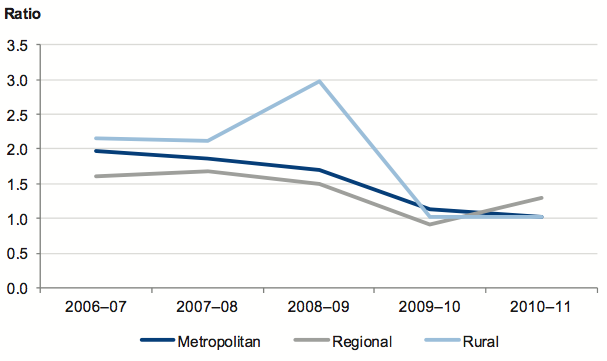

The results of our analysis of the 87 public hospitals, at the hospital category level, are summarised in Figure A.

Figure

A

Financial sustainability risk assessment by hospital category

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

An analysis of five financial sustainability indicators over a five-year trend period found that the public hospital sector, on average, has an overall medium-risk financial sustainability assessment consistent with 2009–10. The trends showed a slightly improved capacity for hospitals to meet their short-term commitments. However, they are under continuing pressure to meet their long-term commitments from the proceeds of their own operations, particularly to maintain and replace their assets as and when necessary.

The overall risk to the financial sustainability for public hospitals is medium. However:

- Twenty-nine public hospitals were considered high risk at 30 June 2011 (26in2009–10), most commonly because they were assessed as generating insufficient cash to adequately fund their operations

- 61 per cent of hospitals, including 25 major metropolitan and regional hospitals, had cash holdings equivalent to less than 30 days operating cash outflows. This included 24 hospitals with less than seven days operating cash flows (17 in 2009–10), nine of which were metropolitan hospitals.

Individual public hospital boards and the department share responsibility for financial performance and management within the sector. During 2011, the department concluded that 29 public hospitals (30 in 2010) did not technically meet the going concern test in the Australian Accounting Standards. This was consistent with our analysis. Consequently, the department provided the boards of those hospitals with a letter of comfort stating that it would provide adequate cash flows to enable them to meet their current and future obligations up to September 2012, should this be required.

Over and above the analysis of financial sustainability indicators, trends and risks, the ability of management and the governing body to make decisions necessary to affect an entity’s operations needs to be considered in assessing an entity’s performance. For public hospitals, despite the application of sector neutral Australian Accounting Standards and accrual accounting, the funding model does not progressively fund entities for the depreciation of their assets.

The funding model allocates capital grants strategically across the sector rather than progressively to each entity. Funds for replacing assets are not provided until the government considers replacement is appropriate given its strategic review of the sector’s needs and other spending priorities. Nevertheless, legislatively the governing board of each hospital is required to be accountable for the entity’s financial management and performance.

Our analysis showed that funding arrangements have a direct and significant impact on the financial sustainability of public hospitals. The funding model limits the ability of governing bodies and management to make decisions around asset maintenance and replacement, and some major hospitals consistently experience cash shortages. This has implications for the governing boards of public hospitals and their ability to fulfil their legislative responsibilities.

Common internal control weaknesses

General internal controls

Public hospital internal control structures were adequate for financial reporting purposes, although the strength of these systems varied between public hospitals. We identified instances where important internal control mechanisms commonly needed to be strengthened.

The following internal control mechanisms require strengthening at public hospitals:

- 30 per cent of public hospitals were not independently reviewing masterfile standing data changes

- 24 per cent had deficiencies in preparing and reviewing key account reconciliations

- 26 per cent needed to improve their management reporting and governance

- 22 per cent had control weaknesses over the acquisition, maintenance and monitoring of assets

- 22 per cent had control weaknesses relating to payroll authorisation and management

- 17 per cent had control weaknesses over the authorisation of supplier payments.

These matters, together with other audit findings and recommendations, were reported to the relevant hospital boards and their management teams.

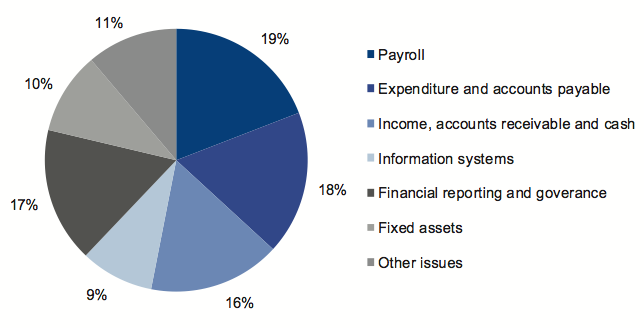

Controls over procurement

For the financial year ended 30 June 2011, public hospitals procured goods and services in excess of $1.6 billion. This was an increase of $74 million from the previous year.

Given the financial significance of public hospital expenditure on supplies and services, and the importance of hospitals achieving value-for-money using taxpayer funds, we reviewed controls and processes for purchasing, in particular those for procurement, tendering and related governance.

The larger metropolitan and regional hospitals generally had more comprehensive policies and internal controls in place compared to rural hospitals, which was pleasing given the relative proportion of expenditure they incur. However, there are opportunities for improvement across the sector, particularly relating to procurement reporting requirements and benchmarking procurement outcomes. The following was noted:

- 58 per cent of public hospitals did not specify reporting requirements or frequency in their procurement policies

- 55 per cent had not developed a clear definition of high-risk, high-value or complex procurement

- 91 per cent did not benchmark their procurement outcomes and costs against external standards

- 46 per cent were unable to demonstrate that procurement policies, practices and processes had been reviewed since 30 June 2009

- 53 per cent had not commissioned internal audits of their procurement activities or practices

- 37 per cent had not included risks associated with procurement in their risk management register.

Controls over information technology security

Given the highly sensitive nature of information held by public hospitals in relation to patients, as well as the financial and operational aspects of the business, effective security over information systems is critical. To protect information from theft or manipulation, hospitals should have appropriate controls over their information technology systems.

Information technology (IT) system security at public hospitals was generally adequate for protecting and restricting access to sensitive data. The following positive aspects were noted:

- 84 per cent of public hospitals had a documented IT security policy or were in the process of developing one

- 85 per cent of the policies had been reviewed and updated at least once in the past three years

- 68 per cent of public hospitals, including all major metropolitan and regional hospitals, trained staff in IT security policies and procedures

- 92 per cent had established adequate controls and processes to manage changes to IT systems

- 92 per cent had adequate IT risk management policies

- 100 per cent had adequate backup and recovery procedures.

Despite the positive results there are opportunities for improvement at most public hospitals. The opportunities particularly relate to developing information security classification policies for sensitive data, establishing an IT steering committee and monitoring compliance with policies and procedures. Specifically:

- 88 per cent had not developed an information security classification policy to protect sensitive data

- 55 per cent had not incorporated an IT steering committee into their governance structure

- 74 per cent had not performed an internal audit of their IT security in the past threeyears

- 61 per cent had not established arrangements to monitor compliance with policies and procedures

- 33 per cent did not provide their boards with updates on the status of IT systems and security arrangements.

Recommendations

That public hospitals:

- further refine their financial reporting processes by establishing financial report preparation plans, preparing timely shell financial statements and materiality assessments and performing periodic financial compliance reviews

- assess their policies and practices against the identified general internal control weaknesses to determine the adequacy of their controls, and whether they are operating reliably, efficiently and effectively

- develop comprehensive policies and procedures for procurement and tendering which are appropriately approved and subject to regular review

- develop comprehensive policies and procedures over information technology system security which are approved at board level and subject to regular review

- develop an information security classification policy that outlines criteria for assigning security classifications to information and the required security controls for each classification

- undertake periodic assessments of the adequacy of, and compliance with, information technology security requirements.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report, or relevant extracts from the report, was provided to the Department of Health with a request for comments or submissions.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) comments and submissions, however, are included in Appendix D.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Public hospitals provide complex acute care, prevention, early intervention and primary care, aged care and mental health services.

While metropolitan and regional public hospitals largely provide acute health services, they also provide a mix of mental health, sub-acute, community health services and aged care programs. Rural public hospitals generally offer a higher proportion of aged care and community health services.

This report includes the results of our audit of 87 public hospitals and 25 associated entities, as set out in Figure 1A.

Figure

1A

Public hospitals and controlled entities

Hospital category |

2010 |

2011 |

|---|---|---|

Metropolitan |

||

Public hospitals |

18 |

18 |

Entities controlled by public hospitals |

14 |

14 |

Other associated entities |

2 |

2 |

Regional |

||

Public hospitals |

15 |

15 |

Entities controlled by public hospitals |

2 |

2 |

Rural |

|

|

Public hospitals |

54 |

54 |

Entities controlled by public hospitals |

6 |

6 |

Other associated entities |

1 |

1 |

Total |

112 |

112 |

Note: Entities controlled by public hospitals generally comprise foundations and trusts.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure 1A shows that there have been no changes to the entities that were subject to our 2010–11 audits.

This report informs Parliament about significant issues arising from the financial audits within the public hospital sector, and augments the assurance provided through audit opinions on financial statements that are included in the respective entities' annual reports.

The report comments on the quality and timeliness of financial reporting in the sector, the financial sustainability of public hospitals, and the effectiveness of procurement practices and information technology security.

This report is the second of six reports to be presented to Parliament covering the results of our audits of public sector financial reports. The reports in this series are outlined in Figure 1B.

Figure

1B

VAGO reports on the results of the 2010–11 financial audits

Report |

Description |

|---|---|

Auditor-General's Report on the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria, 2010–11 |

Reports on the results of the audit of the state's annual financial report and addresses the quality and timeliness of financial reporting, explanation of significant financial results for the state and observations on the status and financial implications of significant projects and developments that occurred during 2010–11 and subsequent to year end. Tabled in Parliament on 9 November 2011. |

Public Hospitals: Results of the 2010–11 Audits |

This report provides the results of the audits of approximately 110 entities, addressing the timeliness of their financial reporting, their financial sustainability, and aspects of how they manage procurement and information technology security. Tabled in Parliament on 9 November 2011. |

Water Entities: Results of the 2010–11 Audits |

The report will provide the results of the audits of 20 water entities addressing the timeliness of their financial and performance reporting, their financial sustainability and aspects of how they manage declarations of interests, asset valuations and outsourcing. Proposed to be tabled in Parliament in November 2011 |

Portfolio Departments and Associated Entities: Results of the 2010–11 Audits |

The report will provide the results of the annual financial statement audits of approximately 210 entities. The report will include comment on the timeliness of their financial reporting, financial sustainability and aspects of how they manage grants administration, employee leave, information technology change, and information technology security. Proposed to be tabled in Parliament in November 2011 |

Local Government: Results of the 2010–11 Audits |

The report will provide the results of the audits of approximately 100 entities in the local government sector. It will address the timeliness of their financial and performance reporting, their financial sustainability, their utilisation of internal audit and aspects of how they manage assets and procurement. Proposed to be tabled in Parliament in November 2011 |

Tertiary Education and Other Entities: Results of the 2011 Audits |

The report will provide the results of the annual financial audits of approximately 120 entities with a financial year end other than 30 June 2011 It will address the timeliness of their financial and performance reporting, their financial sustainability and aspects of how they manage capital projects, information technology security, and international student fee revenue. Proposed to be tabled in Parliament in May 2012 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.2 Financial audit framework

1.2.1 Audit of financial reports

An annual financial audit has two aims:

- to give an opinion consistent with section 9 of the Audit Act 1994, on whether financial reports are fairly stated

- to consider whether there has been wastage of public resources or a lack of probity or financial prudence in the management or application of public resources, consistent with section 3A(2) of the Audit Act 1994.

The financial audit framework applied in the conduct of the 2011 audits of public hospitals is set out in Figure 1C.

Figure

1C

Financial audit framework

Planning

Planning is not a discrete phase of a financial audit, rather it continues throughout the engagement. However, initial audit planning is conducted at two levels:

- At a high or entity level, planning involves obtaining an understanding of the entity and its environment, including its internal controls. The auditor identifies and assesses: the key risks facing the entity; the entity’s risk mitigation strategies; any significant recent developments; and the entity’s governance and management control framework.

- At a low or financial reports line item level, planning involves the identification, documentation and initial assessment of processes and controls over management, accounting and information technology systems.

The output from the initial audit planning process is a detailed audit plan and a client strategy document, which outlines the proposed approach to the audit. This strategy document is issued to the client after initial audit planning and includes an estimate of the audit fee.

Conduct

The conduct phase involves the performance of audit procedures aimed at testing whether or not financial statement balances and transactions are free of material error. There are two types of tests undertaken during this phase:

- Tests of controls, which determine whether controls identified during planning were effective throughout the period of the audit and can be relied upon to reduce the risk of material error.

- Substantive tests, which involve: detailed examination of balances and underlying transactions; assessment of the reasonableness of balances using analytical procedures; and a review of the presentation and disclosure in the financial reports, for compliance with the applicable reporting framework.

The output from this phase is a final (and possibly an interim) management letter which details significant findings along with value-adding recommendations on improving controls and processes. These documents are issued to the client after any interim audit work and during the reporting phase.

Reporting

The reporting phase involves the formal presentation and discussion of audit findings with the client management, and/or the audit committee. The key outputs from this process are:

- A signed audit opinion, which is presented in the client’s annual report alongside the certified financial reports.

- A report to Parliament on significant issues arising from audits either for the individual entity or for the sector as a whole.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.2.2 Audit of internal controls

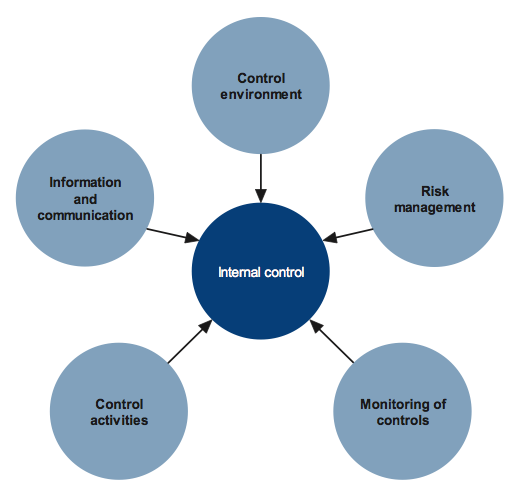

An entity's governing body is responsible for developing and maintaining its internal control framework. Internal controls are systems, policies and procedures that help an entity to reliably and cost effectively meet its objectives. Sound internal controls enable the delivery of reliable, accurate and timely external and internal reporting.

Figure 1D identifies the main components of an effective internal control framework.

Figure

1D

Components of an internal control framework

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In the diagram:

- the control environment provides the fundamental discipline and structure for the controls and includes governance and management functions and the attitudes awareness, and actions of those charged with governance and management of an entity

- risk management involves identifying, analysing and mitigating risks

- monitoring of controls involves observing the internal controls in practice and assessing their effectiveness

- control activities are policies, procedures and practices prescribed by management to help meet an entity's objectives

- information and communication involves communicating control responsibilities throughout the entity and providing information in a form and time frame that allows officers to discharge their responsibilities.

The annual financial audit enables the Auditor-General to form an opinion on an entity's financial report. An integral part of this, and a requirement of Australian Auditing Standard 315 Understanding the Entity and its Environment and Assessing the Risk of Material Misstatement, is to assess the adequacy of an entity's internal control framework and governance processes related to its financial reporting.

Internal control weaknesses we identify during an audit do not usually result in a 'qualified' audit opinion. A qualification is usually warranted only if weaknesses cause significant uncertainty about the accuracy, completeness and reliability of the financial information being reported. Often, an entity will have compensating controls that mitigate the risk of a material error in the financial report.

Weaknesses we find during an audit are brought to the attention of an entity's chairperson, chief executive officer and audit committee by way of a management letter.

Section 16 of the Audit Act 1994 empowers the Auditor-General to report to Parliament on the results of audits. This report includes the results of our review of internal controls related to the financial reporting responsibilities of the public hospital sector.

1.3 Audit conduct

The audits were undertaken in accordance with the Australian Auditing Standards.

The total cost of preparing and printing this report was $205 000.

1.4 Structure of this report

The details in relation to public hospital sector activities covered within each Part of this report are as set out in Figure 1E.

Figure 1E

Report structure – sector entities

Part |

Description |

|---|---|

Part 2: Audit opinions and quality of reporting |

Covers the results of the audits of the 2010–11 financial reports of 87 public hospitals and 25 associated entities. It comments on the timeliness and accuracy of financial reporting and compares practices in 2010–11 against better practice and past performance. |

Part 3: Financial results |

Illustrates the financial results of 87 public hospitals, including financial performance for 2010–11 and financial position at 30 June 2011. |

Part 4: Financial sustainability |

Provides insight into the financial sustainability of 87 public hospitals obtained from analysing the trends in five financial sustainability indicators over a five-year period. |

Part 5: Internal controls |

Assesses internal controls at 87 public hospitals and summarises the control weaknesses commonly identified for the year ended 30 June 2011. It also comments on procurement and information technology security controls across the public hospital sector. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

2 Audit opinions and quality of reporting

At a glance

Background

This Part covers the results of the audits of the 2010–11 financial reports of 87 public hospitals and 25 associated entities.

Independent audit opinions add credibility to financial reports by providing reasonable assurance that the information reported is reliable.

The timeliness and accuracy of the preparation of an entity's financial report is integral to the quality of financial reporting. This chapter compares financial reporting practices in 2010–11 against better practice and time lines, and with 2009–10 performance.

Conclusion

Parliament can have confidence in the financial reports as all completed audits received clear audit opinions.

Overall, the financial report preparation processes of public hospitals and their controlled entities are adequate. They produced accurate, complete and reliable information; however there remain opportunities for further improvement.

Findings

- At 31 October 2011 clear audit opinions had been issued on 111 public hospitals and controlled entities' financial reports for the financial year ended 30June2011.

- Compared with 2010, the overall timeliness of financial reporting in 2011 decreased slightly, nevertheless 100 per cent of public hospitals were finalised within twelve weeks.

- Financial reporting quality would improve if entities prepared shell financial statements early to identify issues to be resolved, performed financial compliance reviews, developed a financial report preparation plan and prepared materiality assessments.

Recommendation

- That public hospitals further refine their financial reporting processes by establishing financial report preparation plans, preparing timely shell financial statements and materiality assessments and performing periodic financial compliance reviews.

2.1 Reporting framework

2.1.1 Financial reporting

This Part covers the results from the audits of 112 public hospitals and associated entities for the 2010–11 reporting period.

Each of the audited entities must prepare its financial report in accordance with Australian Accounting Standards, including the Australian Accounting Interpretations.

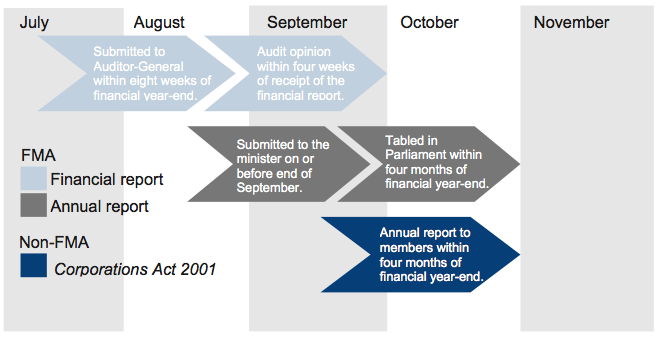

The principal legislation governing financial reporting by public hospitals is the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA) and the Corporations Act 2001. Figure 2A shows the legislative framework applying to each entity.

Figure

2A

Legislative framework for public hospitals and associated entities

Legislative framework |

Public hospitals |

Entities controlled by public hospitals |

Other associated entities |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Financial Management Act 1994 |

84 |

4 |

– |

88 |

Corporations Act 2001 |

3 |

15 |

– |

18 |

Associations Incorporation Act 1981 |

– |

1 |

– |

1 |

No applicable legislative framework |

– |

2 |

3 |

5 |

Total |

87 |

22 |

3 |

112 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Appendix B details the legislative framework applying to each public hospital sector entity.

The FMA requires an entity to submit its annual report to its minister. The report should include financial reports for the entity and any controlled entities and are to be prepared and audited within 12 weeks of the end of the financial year. The annual report should be tabled in Parliament within four months of the end of the financial year.

The Corporations Act 2001 requires a company to report to their members within four months after the end of their financial year. However, the need to consolidate the results of controlled entities into their parent entity's financial report means that controlled entities reporting under the Corporations Act 2001 are, in effect, also required to report within 12 weeks of the end of the financial year.

Figure 2B summarises the legislated reporting time frames.

Figure

2B

Legislative reporting time frames

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The Auditor-General's report, Acquittal Report: Results of the 2009–10 Audits, recommended that entities should adopt the shortened annual reporting time frames achieved for the 2009–10 reporting cycle as the standard for future reporting cycles. Premier's Circular No. 2011/12 issued on 18 May 2011 requests ministers, departments and public bodies to table annual reports between 30 August and 15 September 2011, or earlier if available. This is consistent with the 2009–10 reporting time frame.

2.2 Audit opinions issued

At 31 October 2011, clear audit opinions had been issued on 111 public hospital and controlled entities' financial statements for the financial year ended 30 June 2011. The audit of one of the controlled entities was still to be finalised.

Independent audit opinions add credibility to financial reports by providing reasonable assurance that the information is reliable. A clear audit opinion confirms that the financial report has been prepared according to the requirements of relevant accounting standards and legislation. If the report has not been prepared in accordance with the relevant reporting framework it is issued with a qualified audit opinion. A qualified audit opinion means that the financial report is materially different to the requirements of the relevant reporting framework or accounting standards, and is less reliable and useful as an accountability document.

Definitions of qualified and clear audit opinions are included in Appendix A of this report.

2.3 Quality of reporting

2.3.1 Introduction

The quality of an entity's financial reporting can be measured by the timeliness and accuracy of the preparation and finalisation of its financial report. To achieve cost effective financial reporting, public hospitals and their controlled entities need to have well planned and managed financial report preparation processes.

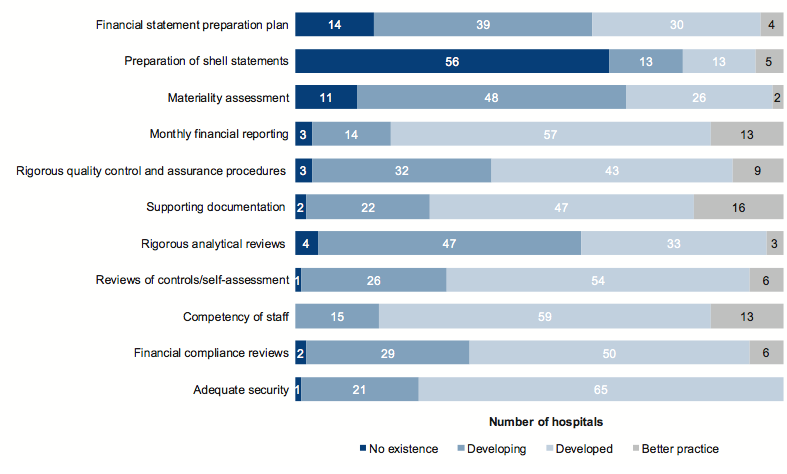

Entities should aim for the better practice elements detailed in Figure 2C to assist them to produce a complete, accurate and compliant financial report within the legislative time frame.

Figure 2C

Selected better practice – financial report preparation

Key area |

Better practice |

|---|---|

Financial report preparation plan |

Establish a plan that outlines the processes, resources, milestones, oversight, and quality assurance practices required in preparing the financial report. |

Preparation of shell statements |

Prepare a shell financial report and provide early to the auditors to enable early identification of amendments, minimising the need for significant disclosure changes at year-end. |

Materiality assessment |

Assess materiality, including quantitative and qualitative thresholds, at the planning phase in consultation with the audit committee. The assessment assists preparers in identifying potential errors in the financial report. |

Monthly financial reporting |

Adopt full accrual monthly reporting to assist in preparing the annual financial report. This allows for the year-end process to be an extension of the month-end process. |

Rigorous quality control and assurance procedures |

Require review of the supporting documentation, data and the financial report itself by an appropriately experienced and independent officer prior to providing to the auditors. |

Supporting documentation |

Prepare high standard documentation to support and validate the financial report, and provide a management trail. |

Rigorous analytical reviews |

Undertake rigorous and objective analytical review during the financial report preparation process to help improve the accuracy of the report. |

Reviews of controls/ self-assessment |

Establish sufficiently robust quality control and assurance processes to provide assurance to the audit committee on the accuracy and completeness of the financial report. |

Competency of staff |

Require that preparers of the financial report have a good understanding and experience in applying relevant accounting standards and legislation. Require that they also have project management and interpersonal skills. |

Financial compliance reviews |

Undertake periodic compliance reviews to identify areas of noncompliance or changes to legislation that impact the financial report. |

Adequate security |

Protect and safeguard sensitive information throughout the process to prevent inappropriate public disclosure. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office and Australian National Audit Office Better Practice Guide: Preparation of Financial Statements, June 2009.

2.3.2 Quality of financial reporting

As shown in Figure 2D, the overall quality of financial reporting in 2010–11 at 80 of the 112 public hospitals and associated entities was substantially the same as in 2009–10. It was positive to note that 26 entities have improved the quality of their financial reporting over that of the previous period.

Figure

2D

Quality of financial reporting in 2010–11

Quality of financial reporting |

Public hospitals |

Entities controlled by public hospitals |

Other health entities |

All entities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Improved from previous year |

22 |

4 |

– |

26 |

Same as previous year |

59 |

18 |

3 |

80 |

Worse than previous year |

6 |

– |

– |

6 |

Total |

87 |

22 |

3 |

112 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The assessment of performance was against better practice criteria using the following scale:

- no existence—function not conducted by the entity

- developing—partially encompassed in the entity's financial reporting preparation processes

- developed—entity has implemented the process, however, it is not fully effective or efficient

- better practice—entity has implemented the processes which are effective and efficient.

The results of our analysis are summarised in Figure 2E.

Figure

2E

Results of assessment of report preparation processes

against better practice elements

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The developed or better practice elements commonly shared by public hospitals and their controlled entities include:

- monthly financial reporting

- rigorous quality control and assurance procedures

- supporting documentation

- reviews of controls/self-assessment

- competency of staff

- adequacy of security.

However, further improvement is needed in relation to:

- financial report preparation plan

- preparation of shell financial statements

- materiality assessment.

Improving these areas will assist the timely preparation of quality financial reports, oversight of resource allocation planning and quality assurance procedures and the early detection and correction of errors.

2.4 Timeliness of reporting

Recognising the importance of financial reports in providing accountability for the use of public monies, entities should prepare and publish their financial information on a timely basis. The later the reports are produced and published after year-end, the less useful they are for stakeholders and for informing decision-making.

The legislated time frame for entities reporting under the FMA to finalise their audited financial reports is within 12 weeks of the end of the financial year. These requirements also apply to entities controlled by public hospitals, as the finalised financial report of the controlling entity is to include the consolidation of the controlled entities.

Following on from the earlier mandated reporting times that applied and were largely achieved in 2009–10; the Premier issued a circular requiring all entities to also meet these earlier reporting time frames in 2010–11.

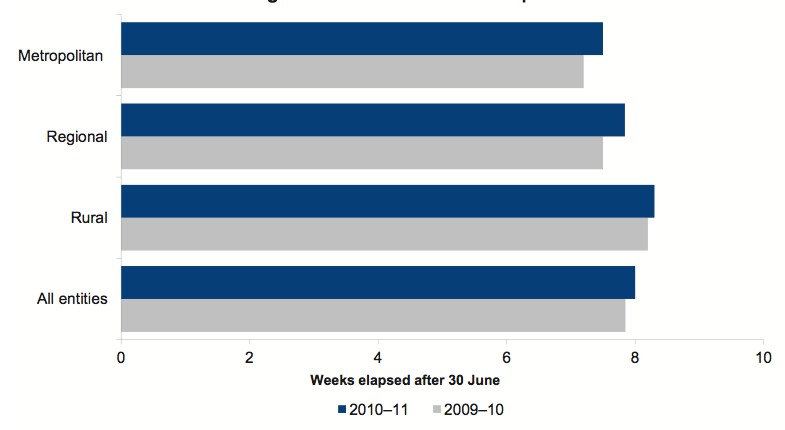

Figure 2F shows that the average time taken by public hospitals and associated entities to finalise their financial reports has slightly increased for metropolitan and regional hospitals, although there was an improvement for rural hospitals for 2010–11.

Overall the average time across all hospitals increased from 7.9 weeks in 2009–10 to 8 weeks in 2010–11. Metropolitan hospitals had an average reporting time of 7.5 weeks in 2010–11, an increase from 7.2 weeks in the prior year. Regional and rural hospitals took on average 7.8 and 8.3 weeks to report in 2010–11, compared to prior year averages of 7.5 and 8.2 weeks respectively.

This result essentially maintains the significant improvement on the 2008–09 financial reporting period where public hospitals took an average of 10 weeks to finalise their financial statements.

Figure

2F

Average time to finalise financial reports

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

For 2010–11, 100 per cent of public hospitals achieved the 12-week time frame. This is in line with 2009–10, when 100 per cent met the 12-week requirement. Figure 2G shows the overall assessment of the timeliness of financial reporting for the 2010–11 reporting period.

Figure

2G

Overall timeliness of financial reporting in 2010–11

Timeliness of financial reporting |

Public hospitals |

Entities controlled by public hospitals |

Other health entities |

All entities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Improved from previous year |

7 |

3 |

– |

10 |

Same as previous year |

73 |

18 |

3 |

94 |

Worse than previous year |

7 |

1 |

– |

8 |

Total |

87 |

22 |

3 |

112 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

It was encouraging to note that the shortened annual reporting time frames were achieved at almost all public hospitals and associated entities for 2010–11, consistent with the Premier's Circular No. 2011/02.

2.5 Accuracy

The frequency and size of errors in the draft financial statements requiring adjustment are direct measures of accuracy. Ideally, there should be no errors or adjustments arising through the audit process.

When our staff detect errors in the draft financial statements they are raised with management. Material errors need to be corrected before a clear audit opinion can be issued.

Overall, there are two types of adjustments:

- financial balance adjustments—changes to the balances being reported

- disclosure adjustments—changes to the commentary or financial note disclosure within the financial statements.

There were a total of 28 material financial balance adjustments to the net result or the net asset position reported in the draft financial statements across the 87 public hospitals in 2010–11 (39 in 2009–10). This means that on average there was about one material adjustment for every three entities. In addition, there were 32 significant amounts incorrectly classified that required adjustment in the draft financial statements.

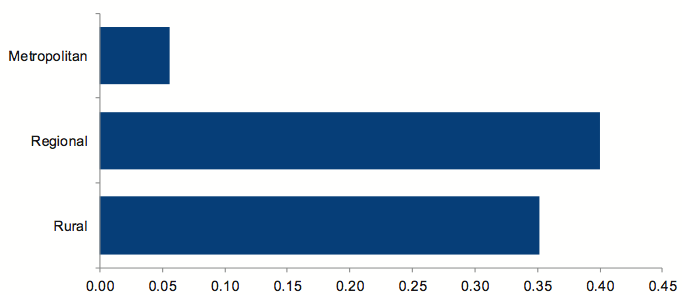

Figure 2H shows the number of material financial balance adjustments per hospital by hospital category.

Figure

2H

Average number of material financial balance adjustments

per public hospital in 2010–11

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The total value of the adjustments to the net asset position was $16.9 million ($16.3 million in 2009–10), comprising a total increase of $21.8 million and a decrease of $4.9 million. The total value of adjustments to the net result was $4.6 million ($3.4 million in 2009–10), comprising adjustments to revenue of $12.3 million and adjustments to expenses of $7.7 million.

In addition to the financial balance adjustments, there were 32 significant disclosure errors that required adjustment in the 2010–11 draft financial statements (79 in 2009–10). This result is reflective of the increased effort made by the Department of Health and agencies to improve the quality of their financial reporting processes. Figure 2I shows the number of significant disclosure adjustments per hospital by hospital category.

Figure

2I

Average number of material disclosure errors per public hospital in

2010–11

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

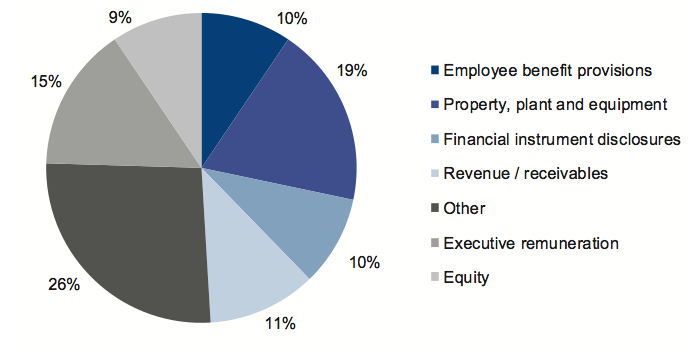

Figure 2J identifies the proportion of material adjustments required to the draft financial statements by category.

Figure

2J

Material financial balance and disclosure adjustments

by category for 2010–11

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The nature of the material adjustments and disclosure adjustments are as follows:

- Property, plant and equipment—a substantial number of adjustments were required to correct the disclosure of property, plant and equipment, particularly in regard to land and building revaluation amounts and classifications, and the calculation of depreciation.

- Executive remuneration—adjustments were required to errors in the disclosure of executive remuneration in the notes to the financial statements. Common errors included not including all responsible persons, including persons in the incorrect income bracket and understating executive remuneration totals.

- Revenue/receivables—adjustments were required to the amount of revenue recognised where entities had incorrectly brought certain revenue to account or had brought revenue to account in the wrong year, contrary to the applicable accounting standard.

- Financial instrument disclosures—adjustments were required to be made to financial instrument disclosures due to errors in the amounts being reported and other incomplete or incorrect disclosures.

- Employee benefits provisions—adjustments were required to errors in the calculation of long-service leave provisions, generally caused by the incorrect application of on-costs, bond rates, wage inflation and probability factors.

Recommendation

- That public hospitals further refine their financial reporting processes by establishing financial report preparation plans, preparing timely shell financial statements and materiality assessments and performing periodic financial compliance reviews.

3 Financial results

At a glance

Background

The financial objective for public hospitals should be to generate a sufficient surplus from operations to meet their financial obligations, and to fund asset replacement and new asset acquisitions. The ability of public hospitals to achieve this depends largely on how well they manage their expenditure and whether they maximise revenue. The performance is measured by the operating result—the difference between revenue inflows and expenditure outflows.

Findings

- Public hospitals had a total operating deficit of $102 million for 2010–11; a significant improvement on the total operating deficit of $156 million in 2009–10.

- This improvement was mainly due to additional capital grants received by the regional hospital sector that are treated as revenue but are not expensed through the Comprehensive Operating Statement.

- Public hospitals generated revenue of $10.8 billion ($10.1 billion in 2009–10) and had expenditure of $10.9 billion ($10.3 billion in 2009–10). The growth in revenue and expenditure mainly arose from an increase in service provision and additional costs associated with CPI increases and previous wage outcomes.

- At 30 June 2011 public hospitals controlled $10.4 billion in total assets ($10.5 billion at 30 June 2010) and $3.1 billion of total liabilities ($3.0 billion at 30June 2010).

3.1 Introduction

The financial objective for public hospitals should be to generate a sufficient surplus from operations to be able to fund asset replacement, new asset acquisition and retirement of debt. The ability of public hospitals to achieve this depends largely on the funding policies established by the Department of Health and on each hospital's expenditure management and revenue maximisation practices. This is reflected in the composition and rate of change in their operating revenue and expenses.

3.2 Financial performance

Financial performance is measured by the result, the difference between revenue inflows and expenditure outflows. Consistent with the provisions of the Health Services Act 1988, public hospital boards and the department share responsibility for financial performance and management within the sector.

The department directly impacts on the financial performance of individual public hospitals. The level of health services to be delivered is negotiated between each hospital and the department each year, and is included in an annual health services agreement or statement of priorities. These agreements specify the volume, scope and quality of services to be provided by the hospital, and the funding to be provided by the department.

The funding cap for acute health services for each hospital is calculated based on the number of treatment services in the agreement and the average cost of care for each acute health treatment service. This casemix funding model takes into account a range of assumptions, including the typical length of a patient's stay in hospital and the category of hospital providing the service. The key assumptions used in the model are reviewed annually. Public hospitals are only partially funded for services that exceed the target. No funding is received for services that exceed the target by more than 2 per cent.

3.2.1 Operating result

The overall operating result for public hospitals improved significantly from a $156 million deficit in 2009–10 to a $102 million deficit in 2010–11. This was mainly due to the regional hospital sector, which went from an operating deficit of $17.8 million in 2009–10 to an operating surplus of $15.5 million in 2010–11. The turnaround in financial performance for regional hospitals occurred largely as a result of increased capital funding provided by the department. Although treated as part of the revenue stream, the resulting expenditure is capitalised and not expensed through the Comprehensive Operating Statement.

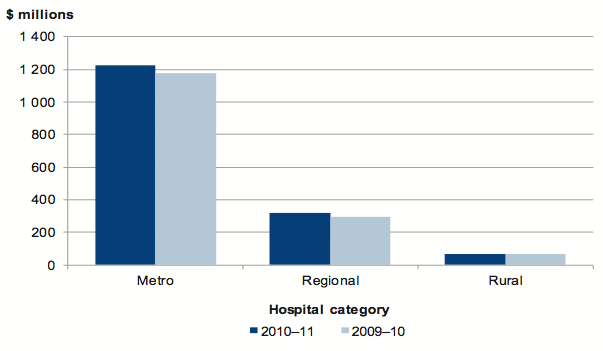

Figure 3A provides a comparison of the total operating results for each category of public hospital over the past two years.

Figure 3A

Total operating results of public hospitals for 2009–10 and 2010–11

|

Category |

Operating result for 2009–10 ($'000) |

Operating result for 2010–11 ($'000) |

|---|---|---|

|

Metropolitan |

(108 982) |

(100 871) |

|

Regional |

(17 801) |

15 544 |

|

Rural |

(29 564) |

(16 894) |

|

All hospitals |

(156 347) |

(102 221) |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Appendix C provides information on the composition of revenue, expenses, assets and liabilities for each public hospital category for 2010–11.

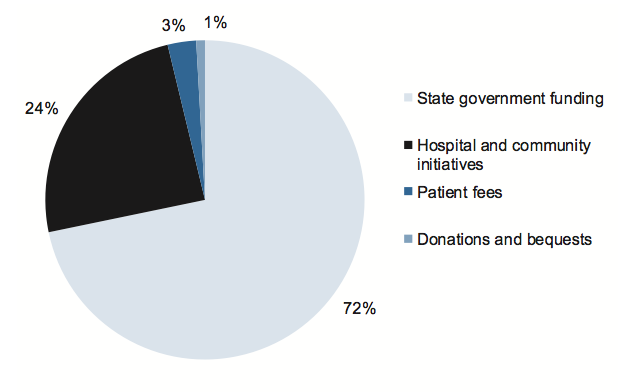

Revenue

The composition of operating revenue remained consistent with that of the previous year. The composition of public hospital revenue for 2010–11 is presented in Figure 3B.

Figure 3B

Revenue composition for 2010–11

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Public hospitals collectively generated $10.8 billion in revenue in 2010–11, an increase of $0.7 billion, or 7 per cent, from 2009–10 ($10.1 billion). The growth was primarily due to an increase in state government funding because more treatment services were provided, and an increase in private patient fees in line with the CPI.

Revenue from hospital and community initiatives, which includes funds generated through additional hospital sources, such as pharmacy, car parks and investments, remained stable.

State government funding remained the largest revenue component for public hospitals, providing 72 per cent of total revenue. Around 40 per cent of state government funding was derived from the Commonwealth Government under the National Healthcare Agreement.

The revenue composition among the three hospital categories differed. The major difference was that rural hospitals derived 54 per cent of their revenue from state government funding, compared with 74 per cent and 70 per cent for metropolitan and regional hospitals respectively. This is because rural hospitals have a larger proportion of residential aged care service facilities which are mainly funded directly from the Commonwealth.

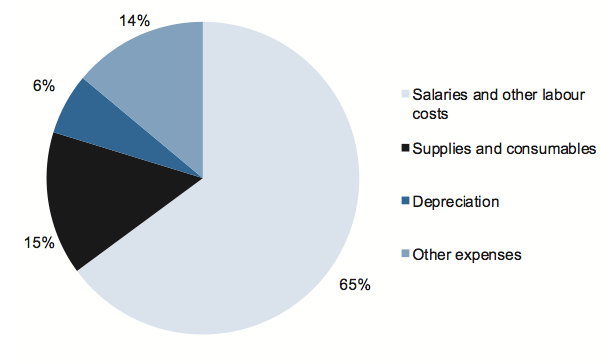

Expenditure

The composition of public hospital expenditure also remained consistent with that of the previous year. The composition is presented in Figure 3C.

Figure 3C

Expenditure composition for 2010–11

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In 2010–11, public hospitals collectively spent $10.9 billion, an increase of $0.6 billion, or 6 per cent, compared to 2009–10 ($10.3 billion).

The growth was primarily a result of a 7 per cent ($466 million) increase in employee benefit costs in line with an increase in services provided and award increases for public hospital sector employees. There was no discernable difference in expenditure patterns between the metropolitan, regional and rural hospital sectors.

3.2.2 Financial position

An entity's financial position is generally measured by reference to net assets—the difference between total assets and total liabilities. However, this measure is less relevant for public hospitals, as they are not-for-profit, and generally do not hold assets from which they generate revenue.

As the revenue base for public hospitals is not tied to the value of their asset base and they cannot sell most of their assets to obtain funds, their objective should be to maintain their assets and related service provision, while managing the level of debt so it can be paid from future operations.

The ability of public hospitals to maintain their assets depends on asset and liability management policies, and is reflected in the composition and rate of change in the value of assets and liabilities.

Assets

In 2010–11 total public hospital assets decreased slightly from $10.5 billion to $10.4 billion. This was mainly due to a decrease in the written down value of assets held by rural hospitals, arising from the year's depreciation charges and the limited amount of new capital works in rural public hospitals.

Liabilities

As at 30 June 2011, total liabilities amounted to $3.1 billion, an increase of $96 million (3 per cent) compared to the same time in 2010.

Current liabilities increased by 5 per cent, from $2.2 billion in 2009–10 to $2.3 billion in 2010–11. Current liabilities were predominately made up of employee leave provisions and accounts payable. The overall increase in current liabilities was largely driven by an increase in employee leave provisions. The overall composition has not changed significantly since prior years.

Non-current liabilities of $787 million for 2010–11 were 7 per cent lower than for 2009–10 when they totalled $843 million. Almost two-thirds of non-current liabilities related to borrowings and finance leases, while non-current employee benefit provisions made up most of the remainder. The overall movement mainly reflected a further year's repayment of finance lease liabilities and the absence of any significant new borrowings taken on by public hospitals in 2010–11.

4 Financial sustainability

At a glance

Background

To be financially sustainable, public hospitals need the capacity to meet current and future expenditure as it falls due, and to be able to absorb foreseeable changes and financial risks as they materialise. This Part provides our insight into the financial sustainability of public hospitals obtained from analysing the trends in five indicators over a five‑year period.

Conclusions

Notwithstanding that 33 per cent of public hospitals (29 of 87) were assessed as having a high financial sustainability risk, the overall financial sustainability of public hospitals in 2010–11 remained stable. The indicators showed a slightly improved capacity for hospitals to meet short-term commitments. However, they are under continuing pressure to meet long-term commitments from the proceeds of their own operations, particularly to maintain and replace their assets as and when necessary.

The funding model has a direct and significant impact on the financial sustainability of public hospitals. It limits the ability of governing bodies and management to maintain and replace assets. The limitations on the governing bodies have implications for the discharge of, and accountability for, the performance of the hospitals.

Findings

- The risk to the overall financial sustainability of public hospitals is medium.

- 33 per cent (29 of 87) of public hospitals were considered high risk at 30 June 2011 (26 in 2009–10); mainly due to generating insufficient cash to adequately fund their operations.

- 61 per cent (53 of 87) of hospitals, including 25 major metropolitan and regional hospitals, had cash holdings equivalent to less than 30 days operating cash outflows.

- Twenty-nine public hospitals (30 in 2010) did not meet the going concern test of the Australian Accounting Standards. The Department of Health provided a letter of comfort for each of the 29, stating it would provide adequate cash flows to enable them to meet their financial obligations if required.

4.1 Introduction

To be financially sustainable, public hospitals need the capacity to meet their current and future expenditure as it falls due. They must also be able to absorb foreseeable changes and financial risks as they materialise.

As detailed in the Department of Health's 2010 report, Your Hospitals – A report on Victoria's public hospitals, public hospital admissions in Victoria have increased by 22 per cent since 2000. To meet the increasing demand for health services and deliver a high quality service, it is essential that hospitals are financially sustainable and maintain and upgrade their infrastructure and property assets. This is particularly challenging given the high costs of technological advances in medical treatments, changing community needs, an ageing population and workforce supply issues.

Insight into the financial sustainability of Victoria's 87 public hospitals is obtained from analysing the trends in five financial sustainability indicators over a five-year period. The analysis reflects on the position of individual hospitals, for the public hospital sector as a whole, and also on the basis of the three categories of hospitals: metropolitan, regional and rural. Appendix D of this report describes the sustainability indicators and risk assessment criteria used in this report.

The financial sustainability indicators and assessments flag departures from the norm that warrant attention. However, to form a definitive view of any entity's financial sustainability requires a holistic analysis that moves beyond financial considerations to include the entity's operations and environment. These further considerations are not examined in this report.

The results in this chapter should be analysed in the context of the regulatory environment in which the hospitals operate. This report also acknowledges the monitoring regime, including some key financial benchmarks, applied by the department in discharging its legislative responsibilities for evaluating and reviewing publicly funded health services.

4.2 Financial sustainability

4.2.1 Overall assessment

Twenty-nine public hospitals had a high risk sustainability assessment at 30 June 2011 (26 in 2009–10) mainly because they were generating insufficient cash to adequately fund their operations.

At 30 June 2011, 53 of 87 hospitals (61 per cent), including 25 major metropolitan and regional hospitals, had cash holdings equivalent to less than 30 days operating cash outflows. This included 24 hospitals that had less than seven days operating cash flows at 30 June 2011 (17 in 2009–10), nine of which were metropolitan hospitals.

In 2011, 29 public hospitals (30 in 2010) did not meet the going concern test in the Australian Accounting Standards. Those hospitals were provided with a letter of comfort that the department would provide adequate cash flows to enable them to meet their obligations should this be required.

Our analysis shows that funding arrangements have a direct and significant impact on the financial sustainability of public hospitals. The funding model limits the ability of governing bodies and management to make decisions around asset maintenance and replacement, and some major hospitals consistently experience cash shortages. This has implications for the governing boards of public hospitals and their ability to fulfil their legislative responsibilities.

Overall risk assessment

A financial sustainability analysis was performed on the 87 public hospitals. The analysis showed that 29 public hospitals had a high sustainability risk at 30 June 2011 (26 in 2009–10) because they were generating insufficient cash to adequately fund their operations.

A summary of the financial sustainability results for each hospital by category, metropolitan, regional and rural, is provided in Figure 4A.

Figure 4A

Financial sustainability risk assessment by hospital category

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

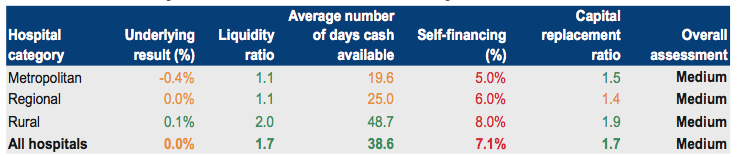

Figure 4B shows the five-year mean financial sustainability risk assessments for each public hospital category. Apart from the self-financing indicator, each financial sustainability indicator recorded a low or medium assessment. Risk for the self‑financing indicator was assessed as high. This led to an overall financial sustainability assessment of moderate risk for all categories of public hospitals and at the public hospital sector level as a whole.

Figure 4B

Five-year mean financial sustainability risk assessment

Legend: Red = High risk; Amber = Medium risk; Green = Low risk.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The individual financial sustainability assessment results for 2006–07 to 2010–11 are provided in Appendix C, along with the risk assessment criteria.

4.2.2 Summary of trends in risk assessments over five‑year period

When the risk assessments for each indicator are analysed individually they show the following trends over the five years to 2010–11:

- Underlying result—the proportion of underlying result risk assessments in the medium category increased over the period. However, the 2008–09 revaluation of assets significantly decreased the number of hospitals in the low-risk category from 2009–10 onward.

- Liquidity—the ability of public hospitals to repay their short-term financial obligations improved, including a slight improvement between the high and medium risk categories in 2010–11.

- Average number of days cash available—the number of hospitals in the low‑risk category was stable over the period however, there was a significant shift from the medium to the high-risk category.

- Self-financing—the mix of high, medium and low risk has remained stable, with a consistently high number of entities with a high-risk rating.

- Capital replacement—the number of hospitals with a high-risk capital replacement assessment remained stable in 2010–11 after deteriorating over the preceding four years.

In summary, the trend shows an improving capacity for hospitals to meet their short‑term commitments. However, they are under continuing pressure to meet their long-term commitments from the proceeds of their own operations, particularly to maintain and replace their assets as and when necessary.

Further information about the risk assessments for each indicator is presented later in this Part.

4.2.3 Impact of the funding model on sustainability

Over and above the analysis of financial sustainability indicators, trends and risks, the ability of management and the governing body to make decisions necessary to affect an entity's operations needs to be taken into account in assessing the entity's performance. Under section 33 of the Health Services Act 1988, the functions of the board of a public hospital are to oversee and manage the hospital, and to ensure that services provided comply with the requirements of the Act and the hospital's objectives.

Notwithstanding the application of transaction and sector neutral Australian Accounting Standards and accrual accounting by public hospitals, the departmental funding model does not fully provide for depreciation until the department has determined the capital requirements of individual hospitals. The department allocates capital grants strategically across the sector rather than progressively to each hospital. However, public hospitals are governed by boards which are legislatively established to be accountable for financial management and performance.

This mismatch between the governance and funding models blurs accountability for the financial performance of the individual hospitals. Management and the governing bodies of hospitals have limited control over capital funding whilst legislatively remaining accountable for the impacts of ageing infrastructure and associated expenditure.

For hospitals to maintain an adequate level of service, their assets need to be maintained and replaced when necessary. Sixty-eight of the 87 public hospitals (78 per cent) had a self-financing risk assessment of high in 2010–11. These public hospitals were essentially dependent on additional funding from the department for most of their maintenance, upgrade and capital needs. For 2010–11, around half of all public hospitals received state capital grants of less than 20 per cent of their depreciation expense for the reporting period (53 per cent for 2009–10).

4.3 Five-year trend analysis

This section provides an analysis and commentary on each indicator's trends for the past five years. The five indicators used are the underlying result, liquidity, average number of day's cash available, self-financing and capital replacement.

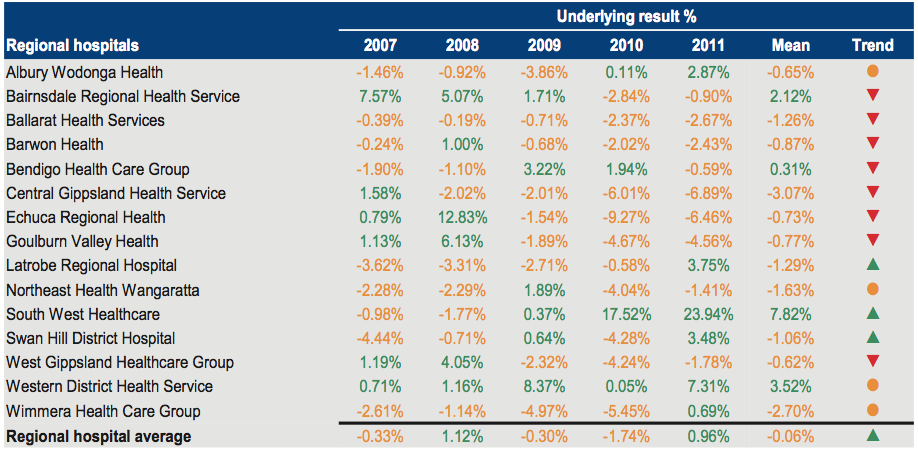

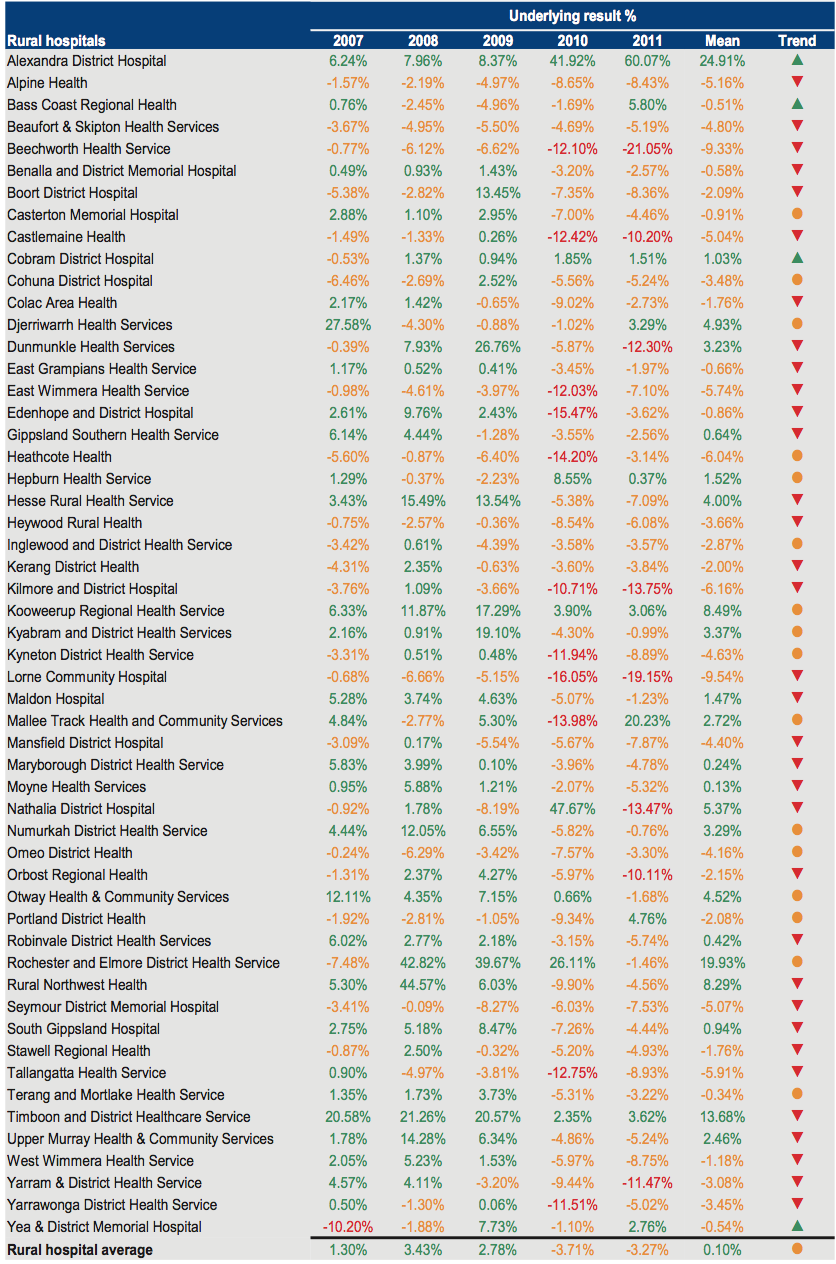

4.3.1 Underlying result

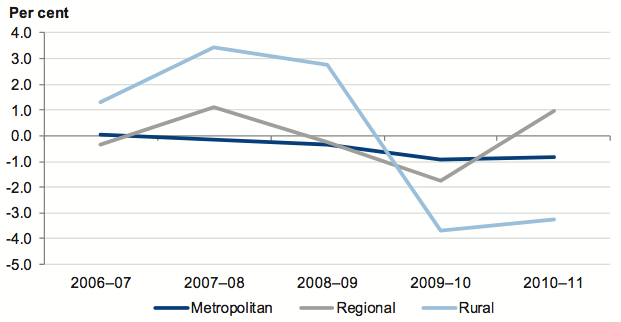

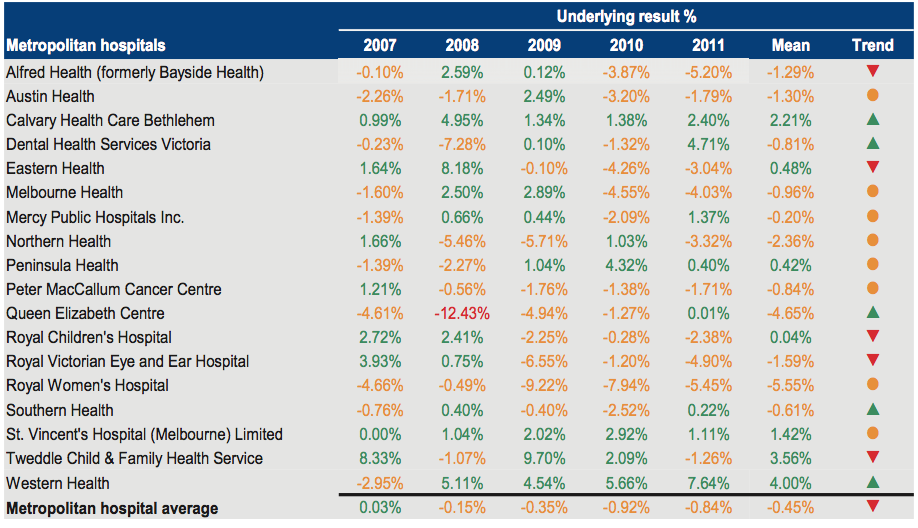

Figure 4C shows that the average underlying result has deteriorated across the five years, although it improved in 2010–11 across all categories of public hospitals.

Figure 4C

Average underlying result by hospital category

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The trend since 2009–10 indicates that revenue has grown faster than expenditure. Depreciation expenses increased significantly in 2009–10, following asset revaluations at 30 June 2009. The significant increase in 2009–10 has now flowed through to 2010–11.

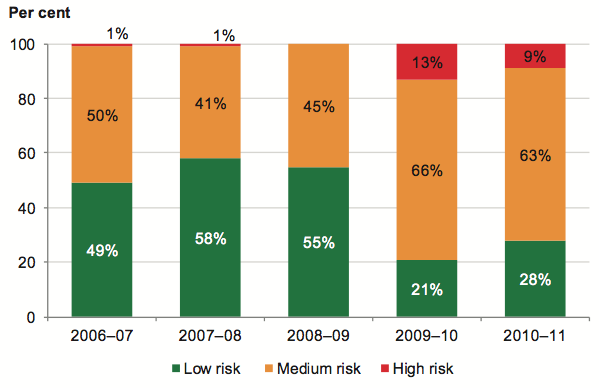

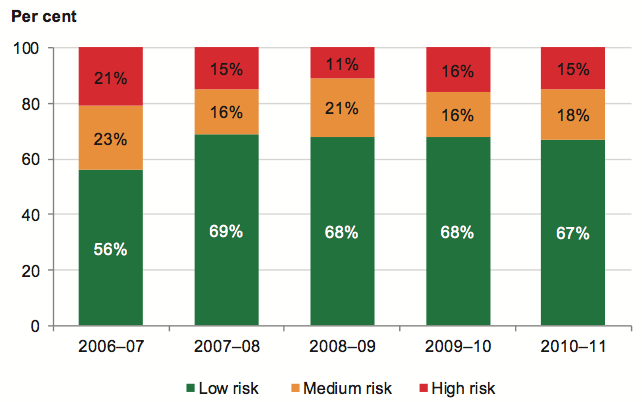

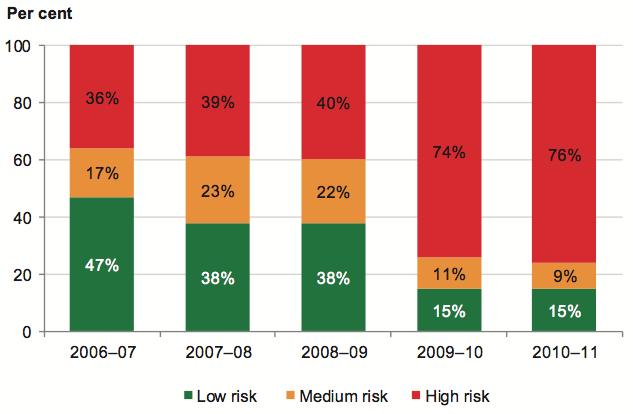

Figure 4D shows that 9 per cent (eight of 87) of public hospitals had a risk assessment for their underlying result of high for 2010–11, an improvement on 2009–10 when 13 per cent (11 of 87) of public hospitals were assessed as high risk.

Figure 4D

Underlying result risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The proportion of underlying result assessments in the medium category increased to 63 per cent (55 of 87) from 49 per cent over the five-year period. However, the effect of the 2008–09 revaluation of assets can be clearly seen in the significant decrease in the number of hospitals in the low risk category from 2009–10 onward.

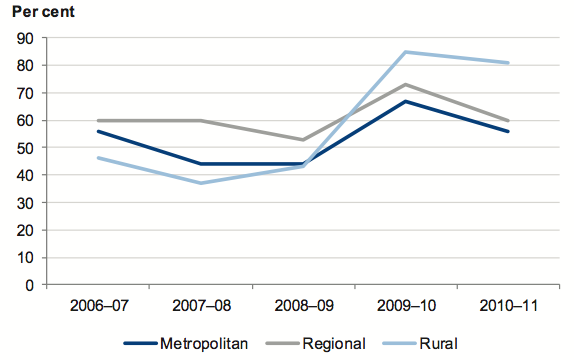

In 2010–11, 68 of 87 public hospitals recorded a negative underlying result compared to 69 in 2009–10. As shown in Figure 4E, 80 per cent of rural hospitals and around 60 per cent of metropolitan and regional hospitals had an underlying deficit for the year.

Figure 4E

Percentage of public hospitals with an underlying deficit

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

While underlying financial performance improved slightly this year, it was still impacted by the substantially higher depreciation charges which commenced in 2009–10, following the revaluation of hospital buildings. Under the funding model, the department does not fund hospitals for depreciation. Therefore it is expected that some hospitals will record operating deficits from time to time.

Over time total revenue from whatever source must equal or exceed total expenditure, or an entity will not be able to sustain its operations. If operating deficits persist there is a real risk that cash reserves will be depleted, and that expenditure and capital programs will need to be curtailed. In particular, expenditure that is perceived to be discretionary, for example maintenance, may be deferred or abandoned, leading to higher demand for replacement of assets in the longer-term.

The department monitors the 'net result before capital and specific items' of public hospitals, rather than the underlying result. The net result before capital and specific items excludes revenue and expenditure types such as:

- capital grants and related expenditure

- depreciation and amortisation

- non-current asset revaluation increments and decrements

- reductions in the value of investments

- reversals of provisions

- the effects of voluntary changes in accounting policies

- impairment of financial and non-financial assets.

Under this measure 31 per cent (27 of 87) of public hospitals recorded a net deficit before capital and specific items for 2010–11, compared with 40 per cent (35 of 87) for 2009–10. These percentages are notably less than those in Figure 4E. There is a risk that decisions made on these figures will be unsound and not provide a sustainable basis for public hospitals, in the event that capital funding is not forthcoming.

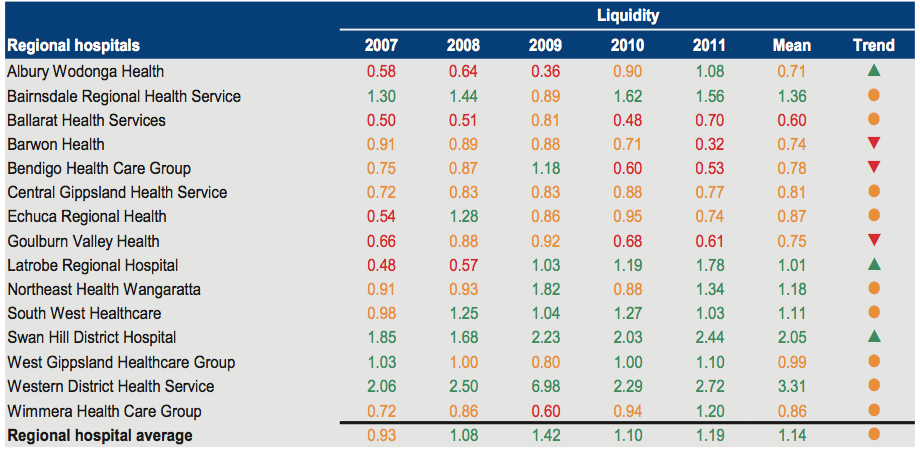

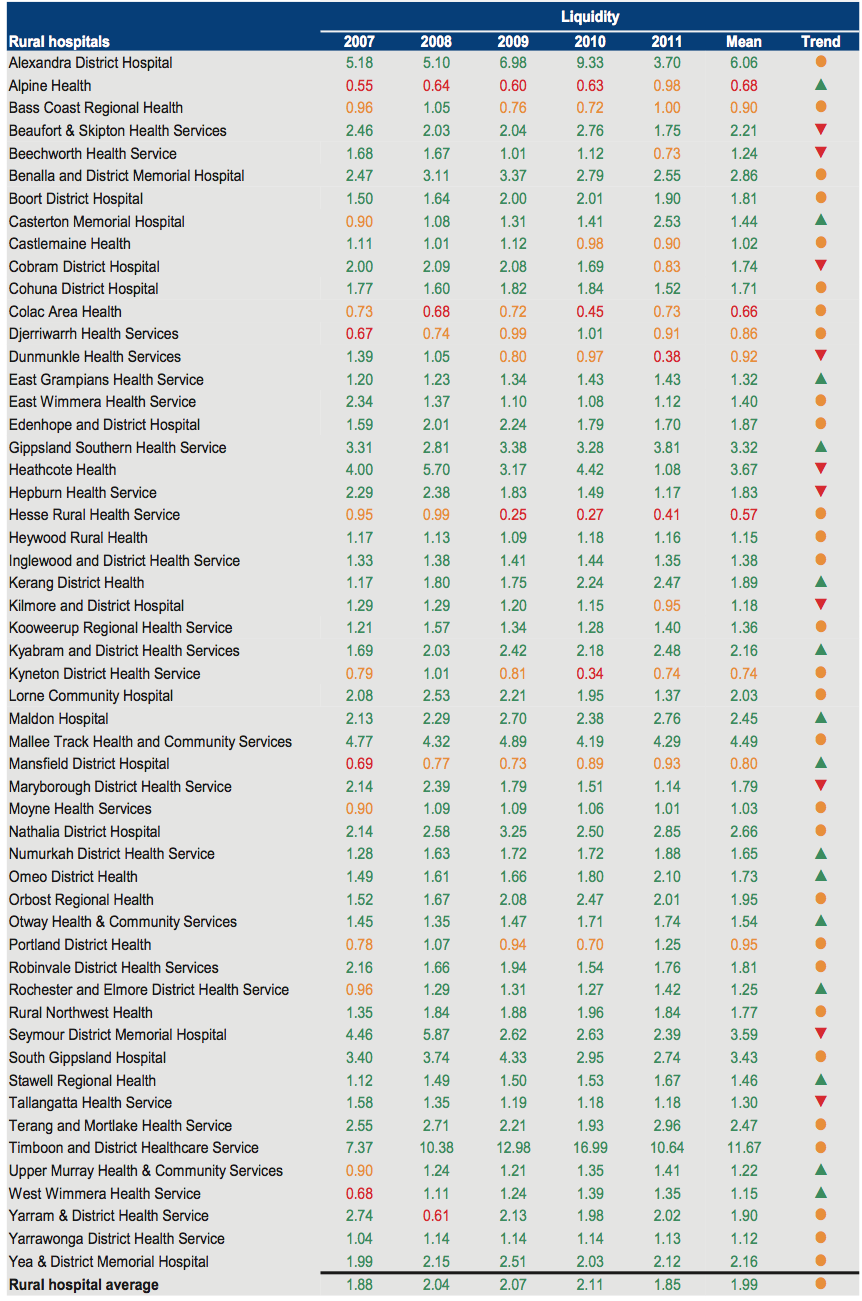

4.3.2 Liquidity

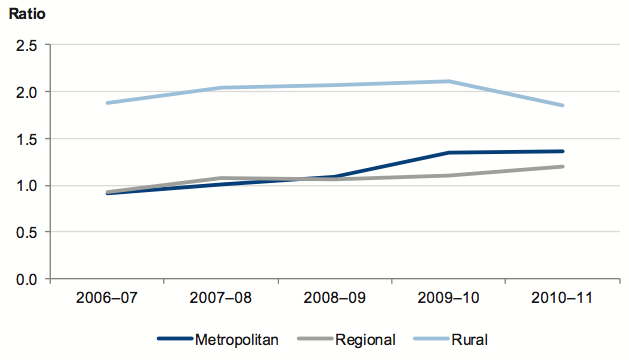

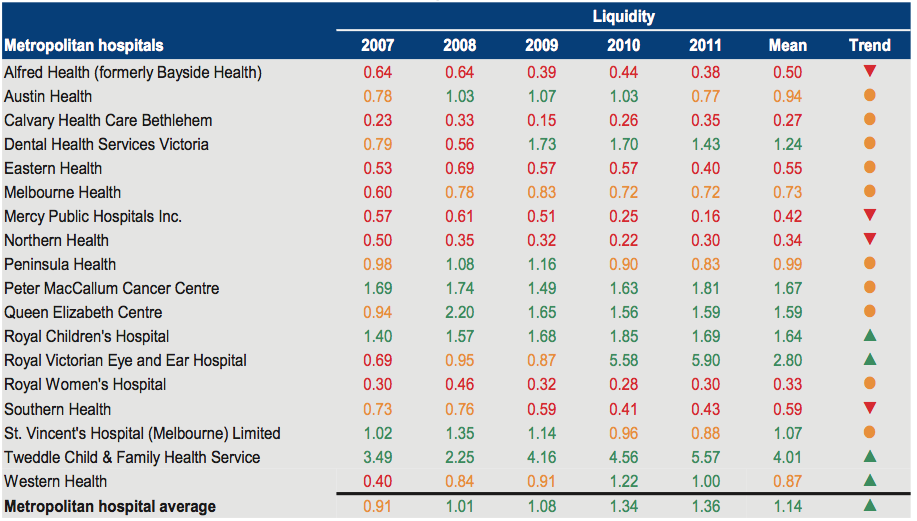

Public hospital liquidity of the larger metropolitan and regional hospitals is monitored by the department. The department's liquidity ratio benchmark is 0.7, which takes into account the funding arrangements it applies to public hospitals.

Figure 4F shows that over the five-year trend period rural hospitals had the highest average liquidity ratio, measuring 1.85 in 2010–11. Although showing some improvement, metropolitan and regional hospitals had the lowest ratios, with averages for 2010–11 of 1.36 and 1.19 respectively.

Figure 4F

Average liquidity ratio by hospital category

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

There has been a relatively stable positive trend in this indicator across all categories of public hospitals over the past five years. Nevertheless, 2010–11 saw deterioration in liquidity ratios for rural hospitals and a slight improvement for metropolitan and regional hospitals.

Overall, 28 of 87 public hospitals had higher current liabilities than current assets in 2010–11, resulting in an assessment of either moderate or high risk. Hospitals in this category must rely on new funds generated in the next financial year to meet some of their existing short-term obligations.

Figure 4G shows that overall the ability of public hospitals to repay their short-term financial obligations has improved over the five-year period, including a slight improvement between high and medium risk in 2010–11.

Figure 4G

Public hospital liquidity risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

During 2011, the department concluded that 29 public hospitals (30 in 2010) did not technically comply with the going concern test in the Australian Accounting Standards. This is consistent with the number of hospitals identified in our analysis as having either a high or medium liquidity risk assessment.

Consequently, the department provided the boards of the 29 hospitals with a written commitment—a letter of comfort—that it would provide adequate cash flows to enable them to meet their current and future obligations as and when they fall due up to September 2012, should this be required. The hospitals, including 16 of the 33 major metropolitan and regional hospitals, account for 66 per cent of the total turnover of all Victorian public hospitals.

Figure 4H provides a listing of hospitals that had a letter of comfort from the department at the date of signing their 2010–11 financial reports.

Figure 4H

Public hospitals receiving a letter of comfort from the Department of Health for 2010–11

|

Metropolitan

Regional

|

Rural

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

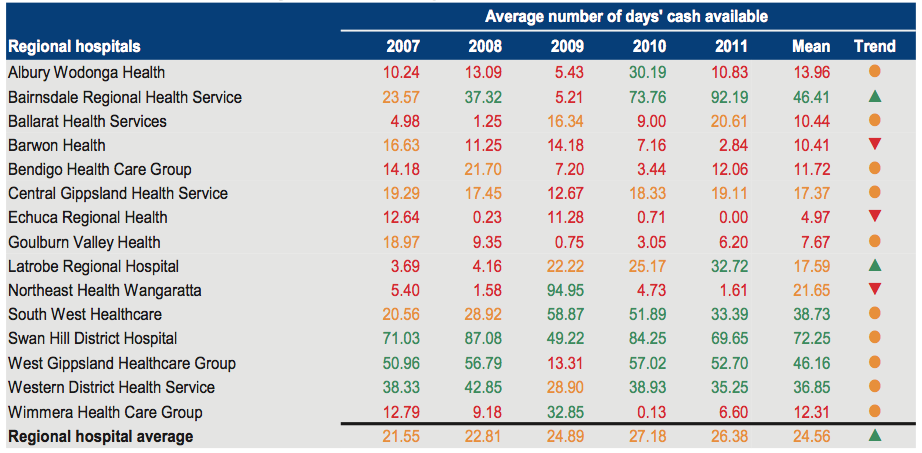

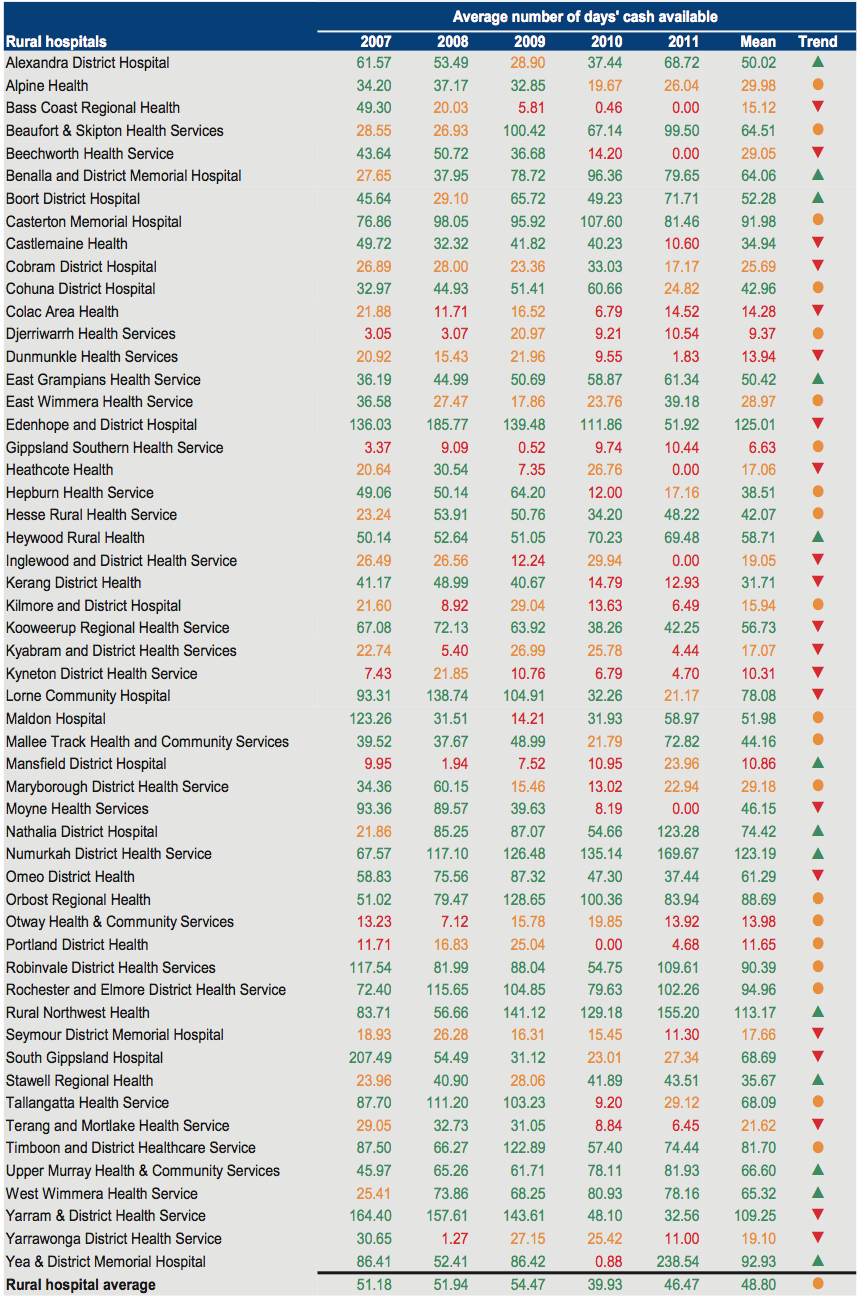

4.3.3 Average number of days cash available

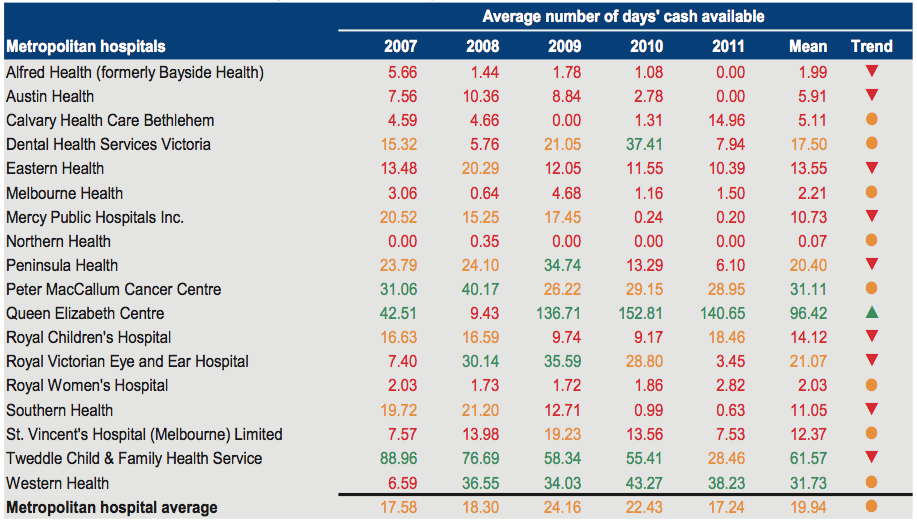

Payments are made to each public hospital fortnightly by the department. While cash management is the responsibility of the hospitals themselves, the department has a significant impact on their ability to do so, given the established hospital funding arrangements.

Prudent financial management provides for an entity to have the equivalent of at least one month's operating cash outflows available as unrestricted cash holdings. This is consistent with the departmental funding model.

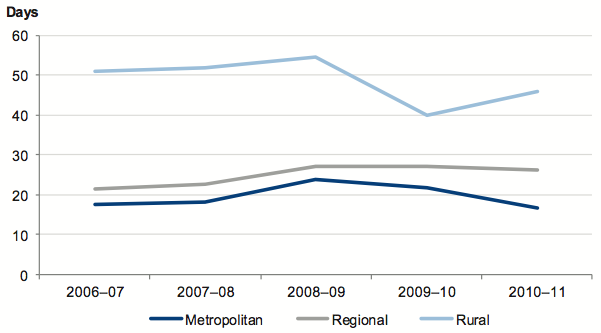

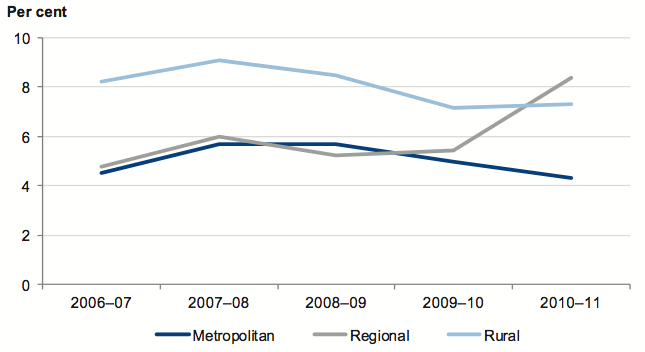

Figure 4I shows that the average number of days of unrestricted cash available at year end to cover operating cash outflows has steadily deteriorated across each public hospital category. The position of rural hospitals on this measure is significantly better than metropolitan and regional hospitals on average.

Figure 4I

Average number of days cash available by hospital category

Note: Restricted cash, comprising funds held in trust, unspent capital grants, as well as other restricted special purpose funds has been excluded from this analysis.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The figure shows that there was a substantial improvement in the rural hospitals' ability to meet their cash flow commitments as at 30 June 2011. However, on average, metropolitan hospitals were not able to fund their operations for more than 20 days.

Figure 4J shows that 53 of 87 public hospitals (61 per cent) had a high- or medium-risk assessment for cash holdings for 2010–11, with cash holdings equivalent to less than 30 days operating cash outflows. This included 25 major metropolitan and regional public hospitals.

Figure 4J

Public hospital average number of days cash available risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Twenty-four hospitals had less than 7 days operating cash flows at 30 June 2011 (17 in 2009–10). Nine of the 24 were metropolitan hospitals. Of the eight larger metropolitan and regional hospitals with low cash holdings at 30 June 2011, five had other less‑liquid financial instruments to call upon in the event of a cash shortage.

Over the five-year period, the number of hospitals in the low-risk category has been stable. However, there has been a significant shift from the medium to the high-risk category.

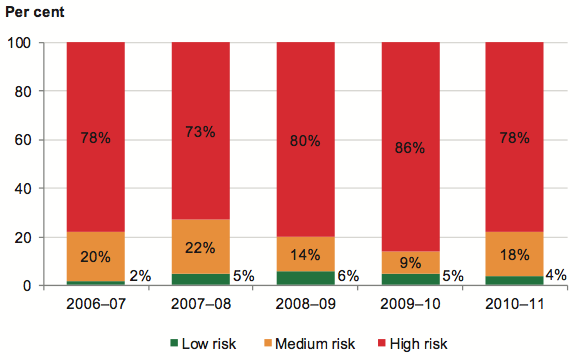

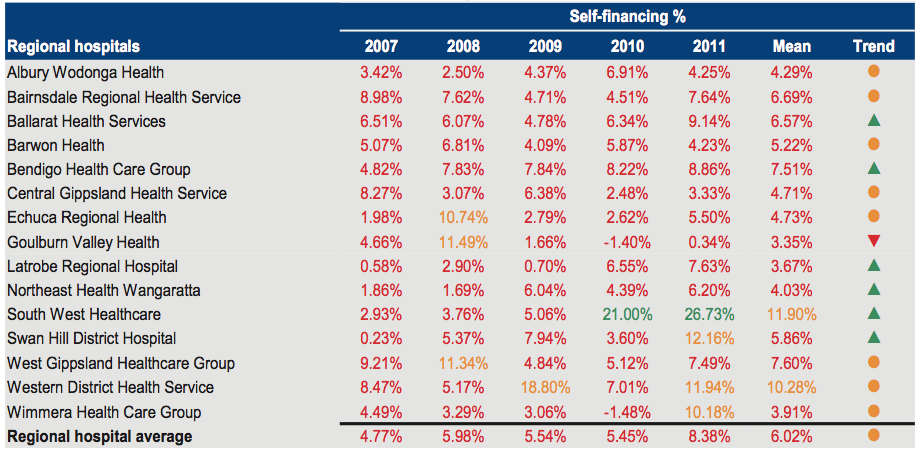

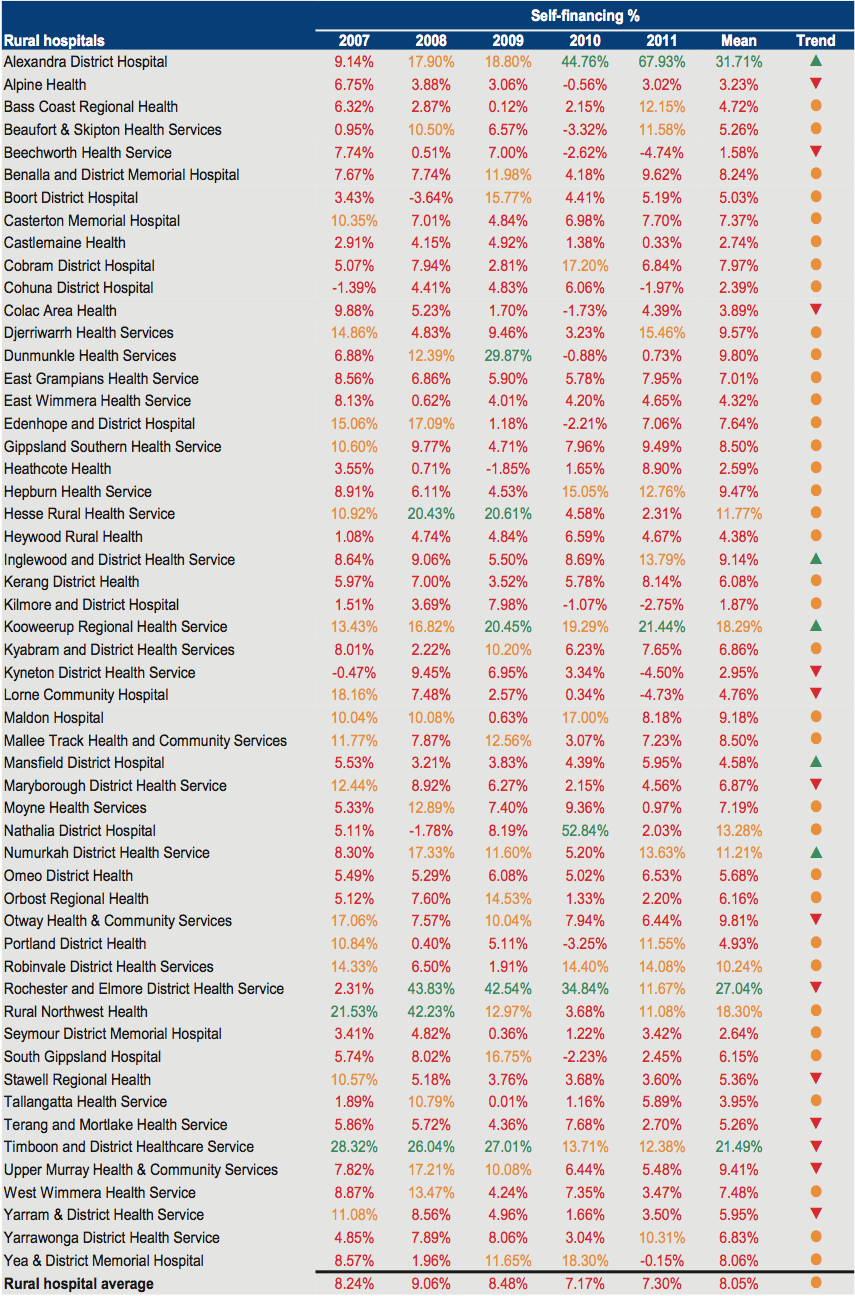

4.3.4 Self-financing

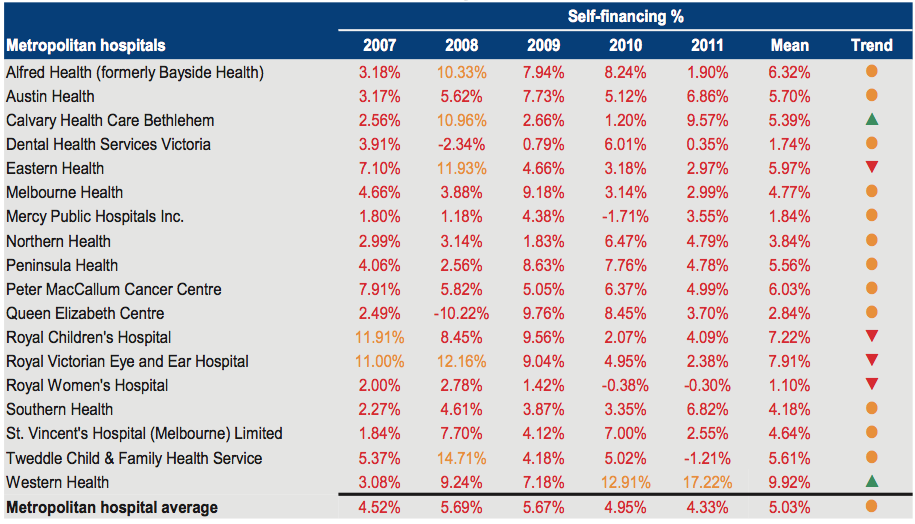

Figure 4K shows that the movement in the average self-financing ratio has been variable for each of the three hospital categories over the five-year period.

Figure 4K

Average self-financing indicator by hospital category

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Regional hospitals improved substantially on this measure for 2010–11 and achieved a notably higher average self-financing ratio than both metropolitan hospitals and rural hospitals.

However, the 2010–11 average self-financing ratio was less than the minimum 10 per cent high-risk benchmark for all three hospital categories, indicating hospitals cannot effectively replace their assets over the long term using income generated by their operations. Under these circumstances there is a greater reliance on the provision of additional government funding for asset renewal and replacement.

Figure 4L further illustrates this with 68 of 87 public hospitals (78 per cent) having a self-financing risk assessment of high. This is largely a consequence of the departmental capital funding model.

Figure 4L

Public hospital self-financing risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Over the five-year period, the mix of high, medium and low risk for this indicator has remained stable.

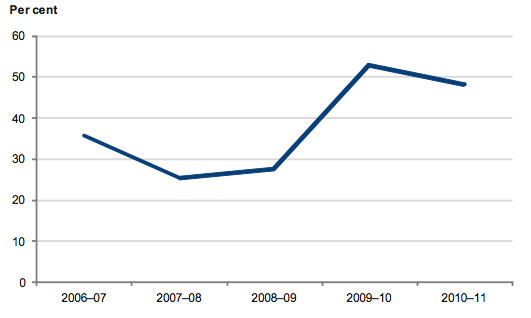

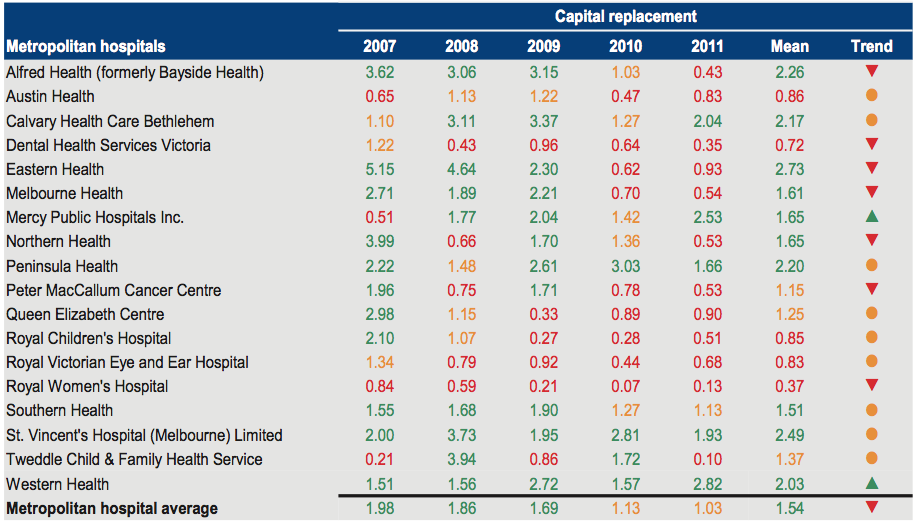

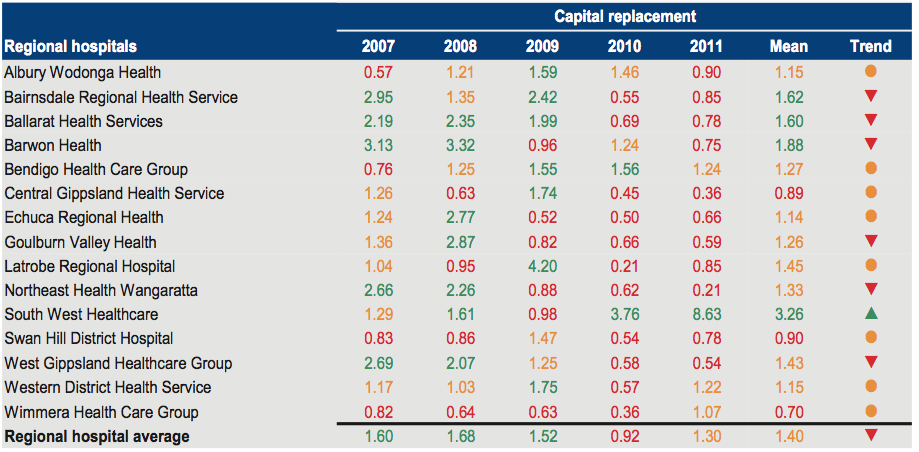

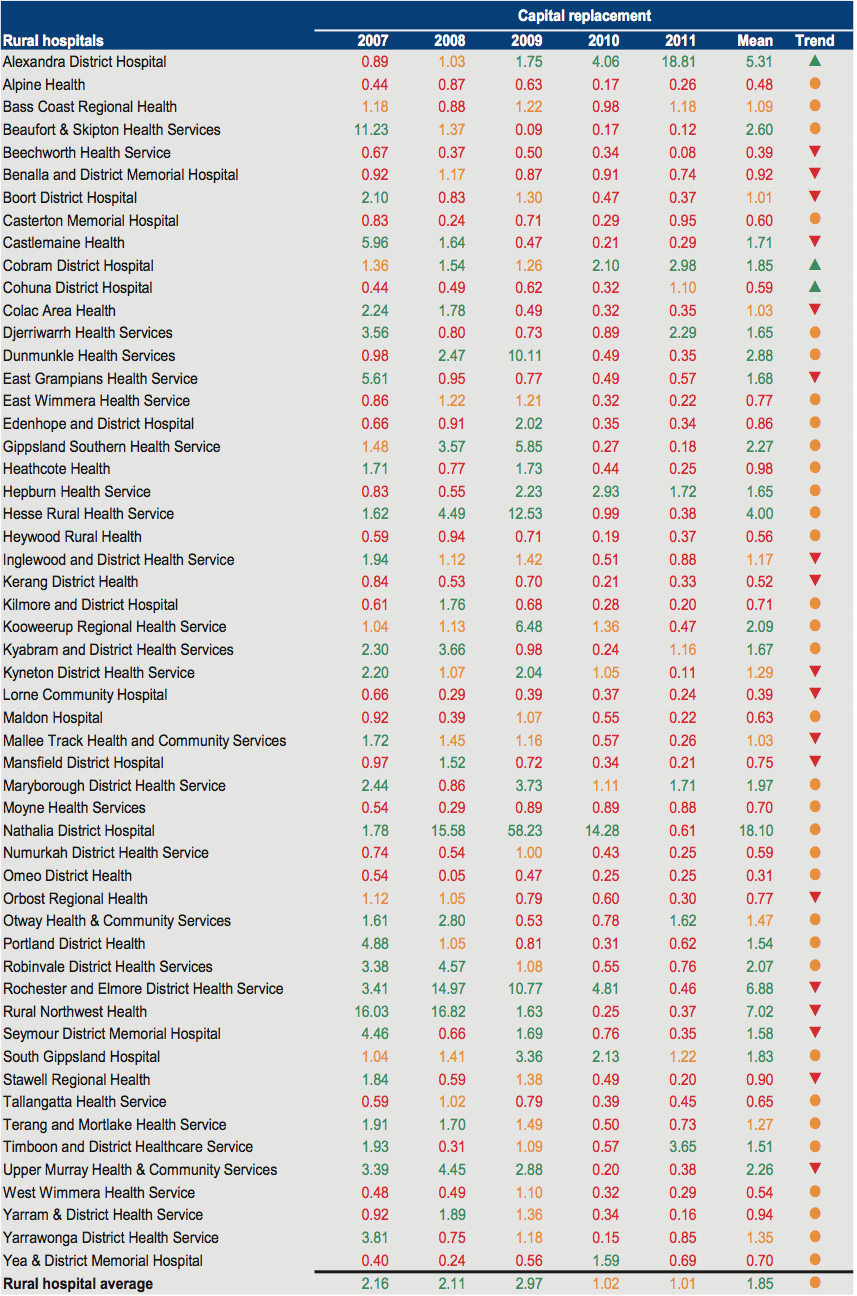

4.3.5 Capital replacement

Figure 4M shows the percentage of hospitals that have received state capital grants of less than 20 per cent of their depreciation expense for each financial year over the five‑year period. For 2010–11, 42 of 87 public hospitals (48 per cent) were in this category (53 per cent for 2009–10).

Figure 4M

Percentage of hospitals with capital grants of less than 20 per cent of depreciation expense

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The capital replacement indicator compares the rate of spending on infrastructure, property, plant and equipment with an entity's depreciation. This is a long-term indicator as capital expenditure can be deferred in the short term if there are insufficient funds available from operations.

Figure 4N shows that the capital replacement indicator deteriorated across all public hospital categories to 2009–10, however, improved slightly in 2010–11.

Figure 4N

Average capital replacement indicator by category

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office

Figure 4O shows the number of hospitals with a high-risk capital replacement assessment remained stable in 2010–11 after having deteriorated over the preceding four years. This indicator was significantly impacted by the upward valuation of hospital buildings in prior reporting periods, and the reassessment of their useful lives.

Figure 4O

Public hospital capital replacement risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The data illustrates that spending on capital works is not sufficient to maintain and upgrade existing infrastructure and equipment, posing a risk to the hospital sector's ability to keep up with the increasing demand for health services. This outcome is consistent with that for the self-financing indicator, and essentially is a consequence of the departmental capital funding model.

It should be noted that the asset spending data used in Figure 4O includes spending on both new and existing facilities. As a result, the true level of underspending on renewing existing assets is understated. The results, nevertheless, remain indicative and identify challenges for the department and a large portion of public hospitals.

5 Internal controls

At a glance

Background

This Part presents the results of our assessment of general internal controls and controls over procurement and information technology security in public hospitals.

Conclusion

Internal controls at public hospitals and controlled entities were adequate for producing reliable, accurate and timely financial reports. Nevertheless, a number of areas for improvement were identified.

Findings