Reducing the Burden of Red Tape

Overview

Red tape can be broadly defined as the excessive, unnecessary or confusing burden imposed on organisations and individuals as a result of regulation. Successive Victorian governments since 2006 and repeated industry surveys have identified reducing red tape as critical to unlocking significant economic growth. Effective red tape reduction must strike a balance between reducing the burden imposed and not detracting from the achievement of regulatory outcomes.

Governments have consistently claimed to have achieved targeted reductions in the regulatory burden. In reporting to government over the last decade, the cumulative reduction is estimated to be at least $3.1 billion. However, weaknesses in the assessment and evaluation of programs, and in the controls to prevent the creation of new red tape have undermined the effectiveness of these programs.

Our assessment of the approach to red tape reduction, and the feedback received from regulators and regulatory commissioners, shows that the current approach needs to be reviewed and options for its renewal provided to government. The current approach is likely providing diminishing returns and future sustained reductions will more likely be achieved through broader structural regulatory reforms.

We have identified practices that need to be improved. These include better understanding red tape, improving how initiatives are selected and evaluated, and critically revising the approach to stakeholder engagement.

Reducing the Burden of Red Tape: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER May 2016

PP No 156, Session 2014-16

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Reducing the Burden of Red Tape.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

26 May 2016

Auditor-General's comments

|

Dr Peter Frost Acting Auditor-General |

Audit team Ray Winn—Engagement Leader Dallas Mischkulnig—Engagement Leader Charles Tyers—Team Leader Jason Cullen—Team member Stefania Colla—Team member Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Andrew Evans |

Reducing the burden of red tape has long been on the agenda for Victoria and governments around the world. Estimates of the impact of red tape have varied and are complicated by perceptions and understanding of what red tape is. In this audit, we define red tape as the excessive, unnecessary or confusing burden imposed on organisations and individuals as a result of regulation. Regardless of how red tape is defined and what it captures, stakeholder groups agree that the effects of red tape are clearly felt. Reducing red tape has the potential to offer significant economic benefits for both organisations and individuals.

Over the past decade, successive Victorian governments have maintained a focus on red tape reduction. In this regard, Victoria has led the way nationally. However, in this audit, I found that the red tape reduction programs that have been in place during this period—Reducing the Regulatory Burden and the Red Tape Reduction Program—needed improved assurance, public reporting and transparency.

The longstanding focus on tackling obvious sources of red tape offers diminishing returns. Agencies now need to turn their attention to identifying more complex, cross-portfolio strategies that can drive further improvements in regulatory efficiency and effectiveness. New regulations must be subject to greater scrutiny and oversight to ensure any additional red tape they create is minimised.

The programs devised over the past decade have reflected the red tape priorities of the government of the day. Although the overall target—to achieve a 25 per cent reduction in red tape—has not significantly changed over this time, the scope of the programs has expanded to capture more regulatory costs and include a greater number of beneficiaries. While this may extend potential benefits to a broader group of stakeholders, greater transparency and accountability is needed to make the claimed monetary savings more credible.

The ultimate beneficiaries of these initiatives—businesses, not-for-profit organisations, hospitals, schools and private individuals—also need to be able to understand and have confidence in the changes made as a result of red tape reduction initiatives. Agencies should focus on engaging with beneficiaries after the introduction of burden-reduction measures to verify that the claimed savings are real and have resulted in meaningful improvement.

To fully appreciate the benefits of red tape reduction programs, it is important to understand the balance between savings, investment and accepted risks. The tools provided by the Department of Treasury & Finance for each of the programs have helped agencies estimate savings. However, agencies have not sufficiently measured the true costs of implementing red tape reduction initiatives or assessed any associated risks. Greater attention is needed to ensure that new initiatives do not cause any adverse social or economic outcomes.

My recommendations are designed to improve stakeholder confidence in the impact of these programs on reducing regulatory burden. The government's new program and commitment to continue its focus on red tape reduction is encouraging, but it needs to improve the selection and evaluation of its initiatives. This has also been highlighted by regulators and the Commissioner for Better Regulation.

It is pleasing to see that my recommendations have been accepted by the departments and agencies involved in this audit and that they have identified the actions they intend to take to address the issues raised.

I extend my thanks to the officers from all departments and the regulators participating in the audit, as well as the Commissioner for Better Regulation and the Red Tape Commissioner.

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

May 2015

Audit summary

Regulation involves the imposition of government-authorised rules through the use of primary or subordinate legislation. These rules can impose obligations on businesses, not-for-profit organisations, government agencies and individuals, and are a critical means used to achieve the economic, social and environmental policies of government.

The decision to regulate must be carefully considered as it can impose a burden on the regulated organisations and individuals and can divert government resources away from service delivery. Regulation is appropriate when:

- it is the most effective and efficient way of achieving desired government outcomes

- the benefits clearly outweigh the costs

- the benefits would not have been achieved through a non-regulatory approach.

In this audit, we define red tape as the excessive, unnecessary or confusing burden imposed on organisations and individuals as a result of regulation. Regulatory burden is not always bad—where it effectively and efficiently achieves the type of protections and outcomes intended by government it is justified because its benefits outweigh the burden imposed and the resource costs to government.

However, where regulation is ineffective or where a given outcome could have been achieved without regulation it can have significant consequences for all Victorians because it diverts resources from productive uses and can undermine economic growth. The aims of red tape reduction programs are to identify and eliminate regulatory burden that is unnecessary, ineffective or inefficient.

Successive governments since 2006 and repeated industry surveys have identified reducing red tape as critical to unlocking significant additional economic growth. Over the past decade, governments have maintained a commitment to reducing red tape based on the perception that there is considerable scope for improvement and that the economic benefits of doing so are significant. Governments have consistently targeted and claimed to have achieved 25 per cent reductions of the regulatory burden. Government has claimed that over the past decade its programs have cumulatively reduced red tape by at least $3.1 billion.

This audit examined whether red tape reduction initiatives have been effective in reducing the burden of regulation in Victoria.

Conclusions

While red tape reduction programs have focused on reducing the regulatory burden faced by different sections of the community, the evidence about their management and effectiveness falls short of confirming the scale of benefits claimed by agencies in reporting to government by the Department of Treasury & Finance (DTF).

Weaknesses in the assessment and evaluation of these programs and in the controls to prevent the creation of red tape have undermined the effectiveness of red tape reduction programs.

In addition, gaps and weaknesses in the review processes for new or renewed regulation have added or maintained red tape that has not been adequately tested to assure its necessity or efficiency. As there has been no central, coordinated oversight of these review processes, it is unclear to what extent untested regulation has negated the gains from red tape reduction programs.

Our assessment of the current approach to red tape reduction and the feedback received from regulators and regulatory commissioners shows that the approach needs to be reviewed and options for its renewal provided to government. Our assessment also suggests diminishing returns from this approach and that most future sustained reductions will be achieved through broader structural regulatory reforms.

We have also identified practices that need to be improved under the current approach or a refreshed approach. These include better understanding red tape, improving how initiatives are selected and evaluated, and critically revising the approach to stakeholder engagement.

Findings

Effectiveness in reducing red tape

Unnecessary and inefficient regulation has a significant effect on economic growth. Red tape reduction programs since 2006 have focused departments and regulators on minimising this burden.

Our review of how DTF, the first Red Tape Commissioner (RTC) and a sample of regulators have acquitted their red tape reduction responsibilities found positive practices, but also clear weaknesses that have diminished the effectiveness of these programs and that need to be addressed.

Positive practices

Several positive practices have been identified in the course of this audit:

- The consistent government and DTF focus on red tape reduction has driven heightened activity across departments and regulators to implement initiatives.

- DTF has developed, regularly updated and supported a systematic approach for agencies to estimate red tape savings. Regulators have largely applied the mandated approach to estimating reductions in red tape.

- DTF's reports to government on a six-monthly basis on progress towards targets describe individual initiatives and identify many of the risks threatening the success of red tape reduction programs.

- There have been some examples of targeted consultation with the intended beneficiaries of red tape reduction programs, however, this has been limited.

Weaknesses

There are several weaknesses undermining the impact of reduction programs:

- There is a compromised understanding across government, by portfolio and for individual regulators, of red tape imposed and how this burden has changed over time with new or renewed legislation. This makes it difficult to confirm that targets are appropriate and that programs have been effective in reducing the burden imposed by red tape.

- There is a lack of assurance about the effectiveness of existing controls. DTF's advice and inquiries by the former Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission show that the additional or continuing burden from new or renewed legislation is significant and that the controls for eliminating red tape are not fully effective.

- The partial assessment of proposed red tape initiatives focuses on estimating the reduction in the burden without adequately describing implementation costs and the threats to regulatory outcomes.

- The absence of any meaningful evaluation of these programs over the past decade makes it unclear whether forecast benefits have been realised, and whether there were any unforeseen impacts.

- There is inadequate consultation with those affected by red tape reduction programs. Engagement with those affected by red tape or the realisation of benefits has not been effectively structured across government. Current programs need to be more inclusive, understandable and transparent.

- Public reporting lacks transparency and has been inadequate over the past decade. Public reporting has been occasional and sparse, focusing on claimed savings and showcasing selected case studies. The absence of sufficient information on the changing scope and components of these initiatives make the content and impacts of these programs impenetrable to citizens and targeted beneficiaries.

Making red tape reduction more effective

Red tape reduction programs to date have focused the attention and effort of government agencies on reducing the burden of unnecessary and inefficient regulation, but it is not clear whether programs have effectively reduced this burden for beneficiaries. The focus of red tape reduction over the past decade has been on removing the obvious and less complex causes of red tape. However, it is time to consider the more complex, cross-regulator sources of unnecessary burden. These should be integrated into wider regulatory improvement and reform programs.

Management and performance of programs

The way red tape has been understood and the way potential initiatives have been assessed, managed, evaluated and reported on, has not made for coherent, transparent programs that can demonstrate the effective reduction in red tape.

This is evident in the way stakeholders are managed. Red tape programs set poorly informed targets and then fail to adequately evaluate or communicate the outcomes.

We found that:

- departments and regulators have not had the opportunity to suggest how best to reduce red tape in a way that is integrated with wider regulatory reform and that improves regulatory outcomes and regulator efficiency

- intended beneficiaries know too little about the content and intended outcomes of red tape programs. Indeed the information published does not support stakeholders to fully understand the scope of red tape programs

- it is not clear that government is making the best use of the expert regulator resources such as the new commissioners for red tape and better regulation.

Agencies' observations on red tape programs

The common issues raised by regulators and by the newly created Commissioner for Better Regulation demonstrate a need for the target-based approach to red tape reduction and its application to be critically reviewed. They note reduction targets are useful in focusing attention on the removal of redundant, duplicative and unnecessary regulations and the targets can play an important role in highlighting the need to embed regulation reviews in day-to-day practices. The current approach is likely to work well for addressing obvious and less complex causes of red tape but targets should not necessarily be the principal or only mechanism for reducing red tape. Removing red tape should be embedded in programs that will also improve regulatory outcomes and efficiency.

The Environment Protection Authority (EPA) recognised that the current approach is less effective at addressing complex and connected sources of red tape. It risks creating an incentive for regulators to focus on 'low hanging fruit' at the expense of more complex initiatives that may provide greater impacts in terms of both red tape reduction and improved regulatory outcomes.

EPA also highlighted the potential for more significant gains from embedding a focus on red tape reduction into broader initiatives to improve regulatory practice. A broadened approach would allow regulators to gain the benefits of joined up initiatives, and to pilot and identify best practice approaches that can be more widely applied.

All of the regulators identified the need to integrate red tape reduction into their broader work, both at the state and national level to improve how regulation is applied to better achieve intended outcomes.

Recommendations

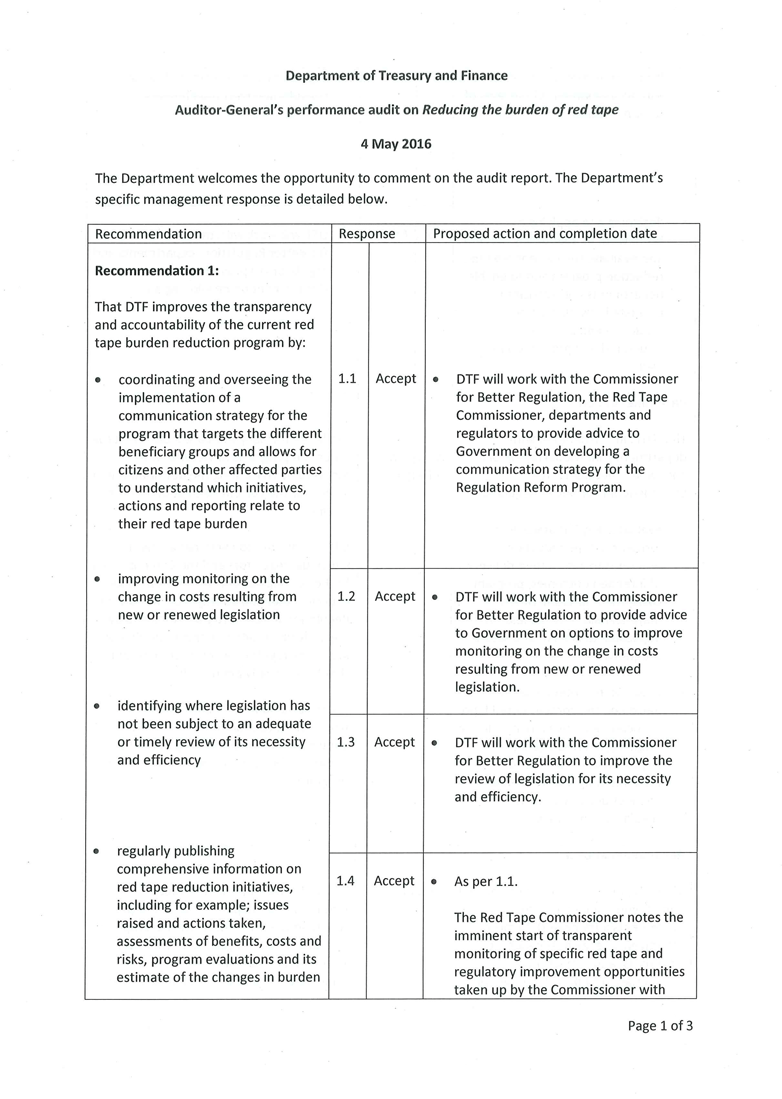

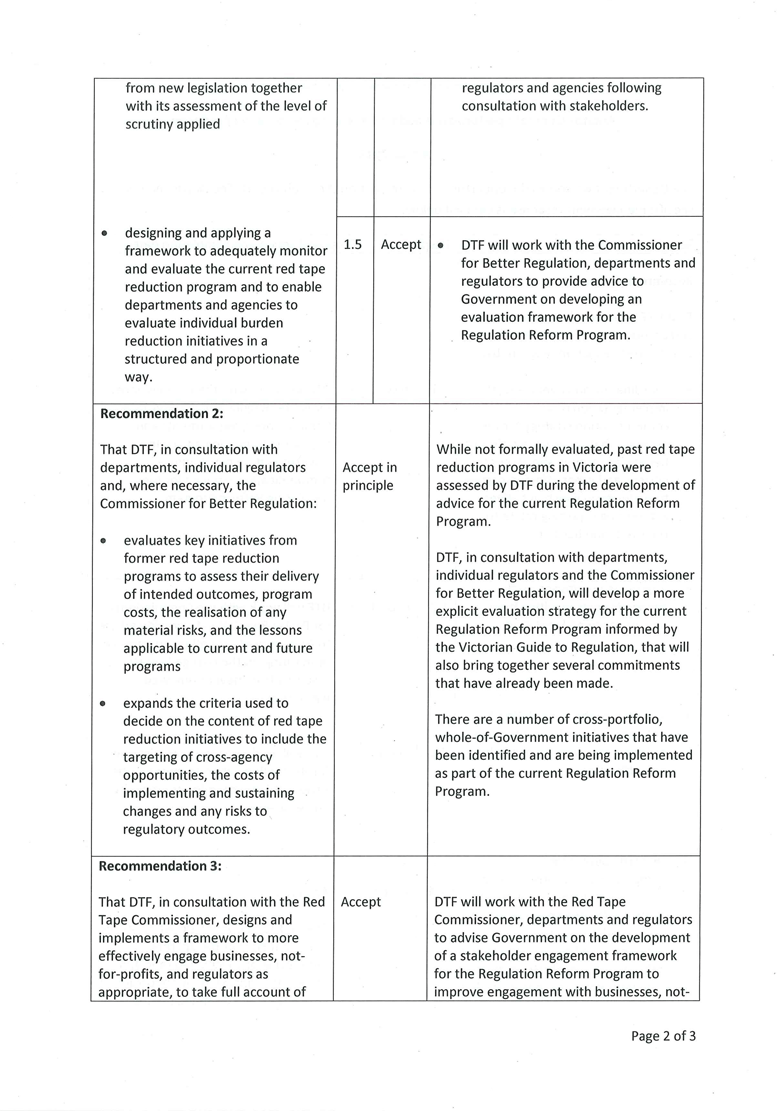

- That the Department of Treasury & Finance improves the transparency and accountability of the current red tape burden reduction program by:

- coordinating and overseeing the implementation of a communication strategy for the program that targets the different beneficiary groups and allows for citizens and other affected parties to understand which initiatives, actions and reporting relate to their red tape burden

- improving monitoring on the change in costs resulting from new or renewed legislation

- identifying where legislation has not been subject to an adequate or timely review of its necessity and efficiency

- regularly publishing comprehensive information on red tape reduction initiatives, including for example; issues raised and actions taken, assessments of benefits, costs and risks, program evaluations and its estimate of the changes in burden from new legislation together with its assessment of the level of scrutiny applied

- designing and applying a framework to adequately monitor and evaluate the current red tape reduction program and to enable departments and agencies to evaluate individual burden reduction initiatives in a structured and proportionate way.

- That the Department of Treasury & Finance, in consultation with departments, individual regulators and, where necessary, the Commissioner for Better Regulation:

- evaluates key initiatives from former red tape reduction programs to assess their delivery of intended outcomes, program costs, the realisation of any material risks, and the lessons applicable to current and future programs

- expands the criteria used to decide on the content of red tape reduction initiatives to include the targeting of cross-agency opportunities, the costs of implementing and sustaining changes and any risks to regulatory outcomes.

- That the Department of Treasury & Finance, in consultation with the Red Tape Commissioner, designs and implements a framework to more effectively engage businesses, not-for-profits, and regulators as appropriate, to take full account of their concerns, proposals and feedback in designing and modifying programs.

- That the Department of Treasury & Finance:

- enhances its advice to government to fully inform it of the inherent uncertainty regarding the baseline, expected benefits, costs and risks of red tape initiatives presented for its approval

- advises government on appropriate red tape targets based on an improved understanding of the red tape burden while explaining how these targets relate to distinct stakeholder groups.

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged throughout the course of the audit with the Department of Treasury & Finance, the Department of Premier & Cabinet, the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning, the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources, the Commissioners for Better Regulation and Red Tape, and the following regulators:

- WorkSafe

- VicRoads

- Consumer Affairs Victoria (part of the Department of Justice & Regulation)

- the Environment Protection Authority Victoria.

In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report or relevant extracts to those agencies and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

1.1.1 The role and significance of regulation in Victoria

Regulation involves the imposition of government-authorised rules through the use of:

- primary legislation, which is scrutinised and made by Parliament

- subordinate legislation, where Parliament authorises the sitting government to make rules without the same level of scrutiny that is applied to primary legislation.

Both types of legislation can impose obligations on businesses, not-for-profit organisations, government agencies and individuals and are critical to achieving the economic, social and environmental policies of government.

The scale and significance of regulation is illustrated by the former Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission's (VCEC) 2013 report on The Victorian Regulatory System. It shows that in 2011–12, the 59 agencies that were regulating state (but excluding local government) legislation applying to Victorian businesses and not-for-profit organisations:

- employed just under 7 500 full-time equivalent staff

- encompassed over 2.2 million licensed/registered parties

- spent $1.3 billion

- collected revenue from licences and registrations of $0.57 billion.

1.1.2 Balancing the costs and benefits of regulation

Regulation is typically considered where the normal functioning of markets or public services does not achieve the outcomes that government wants. Regulation is appropriate when:

- it is the most effective and efficient way of achieving governments desired outcomes

- the benefits clearly outweigh the costs

- the benefits would not have been achieved through a non-regulatory approach, such as voluntary industry changes in behaviour.

The decision to regulate has to be carefully considered because it can impose a significant burden on the regulated organisations and individuals by:

- diverting resources from productive uses to administer and comply with obligations

- delaying decisions

- making it more difficult for new industry entrants to start up

- increasing costs through regulatory fees and charges.

Regulating through legislation can also require a subsidy if regulatory fees do not cover the costs of regulation.

1.2 What is red tape and why is it important?

1.2.1 Defining red tape and its components

In this audit, we define red tape as the excessive, unnecessary or confusing burden imposed on organisations and individuals as a result of regulation. Figure 1A describes the different types of red tape targeted by Victorian programs that aim to reduce this burden.

Drawing on various definitions and from programs operating in Victoria, regulatory burden is not always bad. Where it effectively and efficiently achieves the type of protections and outcomes intended by government it is justified because its benefits outweigh the burden imposed and the resource costs to government.

However, where it is ineffective or where a given outcome could have been achieved without regulation it can have significant consequences for all Victorians because it diverts resources from productive uses and undermines economic growth. The aims of government's red tape reduction programs are to identify and eliminate regulatory burden that is unnecessary, ineffective or inefficient.

Figure 1A

Types of regulatory burden

|

Administrative costs |

|---|

|

Costs incurred to demonstrate compliance with the regulation or to allow government to administer the regulation—including filling in and storing paperwork, conducting tests, responding to notifications and cooperating with inspections. |

|

Substantive compliance costs |

|

Costs that are the direct result of regulations—for example, conducting training, purchasing and maintaining equipment, providing information or completing other actions required to meet the regulatory requirements. |

|

Delay costs |

|

Additional expenses or loss of income resulting from regulation including:

|

|

Economic costs of prohibition |

|

Other costs arising indirectly from the impacts of regulation or how these are administered that limit the ability of businesses to expand or innovate, or that create a barrier to new businesses entering the industry. |

|

Financial costs |

|

The regulatory obligation to pay administrative charges, permit or license fees, taxes, premiums and levies. |

Source: VAGO, and the Department of Treasury & Finance, Victorian Guide to Regulation, December 2014.

1.2.2 Importance of reducing regulatory burden

Since 2006, governments and repeated industry surveys have identified reducing unnecessary and inefficient regulatory burden as critical to unlocking significant additional economic growth. Over the past decade, governments have maintained a commitment to reducing red tape based on the perception that there is considerable scope for improvement and that the economic benefits are significant.

The Department of Treasury & Finance (DTF) estimates that state regulation imposes a multi-billion dollar burden on businesses and not-for-profit organisations, with government consistently targeting 25 per cent reductions in this burden.

Business surveys strongly support the need to reduce red tape to improve competitiveness, boost innovation and deliver improved productivity and economic growth. An increase in regulatory activity increases the potential exposure to excessive, unnecessary or confusing regulatory burden. For example:

- Australian chief executive officers (CEO) across the manufacturing, services, construction and mining industries expected government regulation to place a medium to high cost on their businesses in 2014

- submissions to a 2011 VCEC inquiry found businesses and not-for-profit organisations perceived that the burden of red tape remained large and significant to their operations despite past efforts to reduce this.

1.3 Controlling red tape

1.3.1 Mechanisms to control new and existing red tape

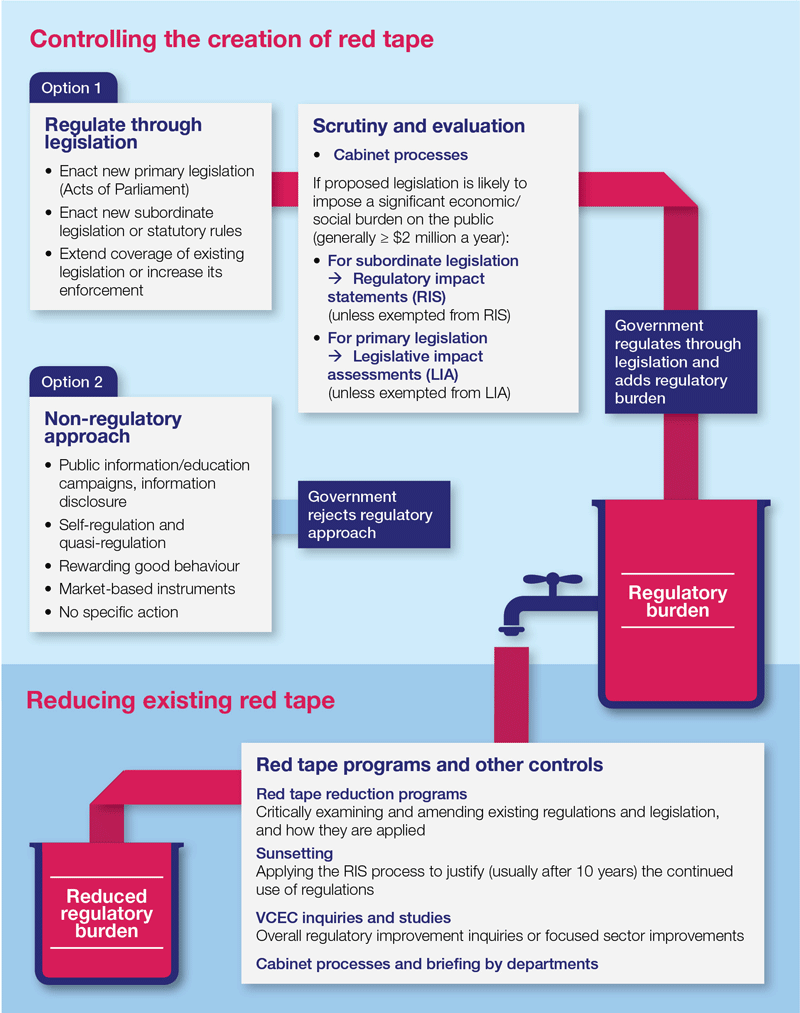

Figure 1B describes the available mechanisms for controlling new and existing regulatory burden to ensure that red tape is not introduced through new regulation and that it is eliminated from existing or renewed legislation.

The upper half of the figure describes the processes used to ensure that:

- regulation is not used where a superior non-regulatory option exists

- where regulation is used, the burden minimised.

If complete and effective, these processes should result in the minimum regulatory burden needed to achieve the desired outcomes.

The lower part of the figure describes controls to reduce red tape from existing regulation, including:

- the red tape reduction programs that are the focus of this audit

- the review of regulations that are 'sunsetting' (the automatic lapsing of subordinate legislation after a fixed period of time—usually 10 years)

- specific regulatory inquiries and improvement studies that were completed in the past by VCEC.

Figure 1B

Controlling unnecessary regulatory burden

Source: VAGO.

1.3.2 Victorian red tape reduction programs

From 2006 to now, there has been a sustained focus on red tape reduction. To address this, there have been three main programs by three governments. Figure 1C summarises the changing targets, scope and stated achievements of red tape reduction programs since 2006 including:

- Reducing the Regulatory Burden (RRB), 2006–10

- Red Tape Reduction Program (RTRP), 2011–14

- the current Regulatory Reform Program (RRP), from 2015.

Targets

All three programs adopted the target of reducing existing red tape by 25 per cent but differed in whether this represented a net reduction (taking account of additional red tape created by new legislation) or gross reduction in red tape. Specifically:

- RRB in August 2007 targeted a $256 million yearly net reduction in administrative red tape, but this was revised in July 2009 to a $500 million yearly reduction made up of:

- a $256 million net reduction in administrative red tape by July 2011

- a $244 million gross reduction in compliance and delay costs by July 2012

- RTRP in March 2011 targeted a $715 million yearly gross reduction in administration, compliance and delay costs by July 2014

- RRP in October 2015 targeted a yearly gross reduction in red tape of between $600 million and $1.6 billion by July 2018. This range was based on estimates from the two earlier program methodologies, alongside 2013–14 nation survey and research data.

Scope

The scope of these programs changed in two respects:

- first, by expanding the type of regulatory costs that would be targeted, going beyond administration costs to also encompass compliance and delay costs

- second, by expanding the type of legislation and parties included.

In 2006, the RRB program excluded from its scope the regulation specifically managed by local government and was only concerned with red tape affecting businesses and not-for-profit organisations. There were subsequent major scope expansions:

- In November 2009, regulatory burden was extended to include local government regulation and the impact on schools, hospitals and individuals' employment, e.g. training and licensing requirements.

- In October 2011, the RTRP program expanded to include state-owned enterprises, the economic activities of individuals and all government services where there are comparable private services, e.g. schools, hospitals, aged care and community services.

- In November 2013, the Victorian Regulatory Change Measurement Manual defined the RTRP program as including the costs imposed by legally enforceable obligations from ministers, departments, regulatory agencies and local governments on businesses, not-for-profit organisations, government service providers that deliver services comparable to those provided by business or the not-for-profit sector, and individuals.

Figure 1C

Controlling red tape

|

Reducing the Regulatory Burden (RRB), 2006–10 |

|

|---|---|

|

RRB starting scope |

|

|

|

|

Targets, changes in scope and reported achievements |

|

|

May 2006 |

Targets—$825 million yearly (25 per cent) net reduction in estimated administrative burden of $3.3 billion by June 2011 (target of $495 million yearly (15 per cent) reduction by June 2009). |

|

April 2007 |

Victorian Standard Cost Model (SCM), published by DTF, describes how to estimate reductions in administrative costs in line with RRB starting scope. |

|

August 2007 |

Revised targets—$256 million yearly (25 per cent) and $154 million yearly (15 per cent) revised targets (because DTF revised estimate of the administrative burden from $3.3 billion to $1.03 billion). |

|

July 2009 |

Expanded scope—new $500 million target confirmed (first flagged in July 2009), comprising:

|

|

November 2009 |

Expanded scope with same target—$500 million target extends coverage to include:

|

|

June 2010 |

Regulatory Change Measurement (RCM) model updated to incorporate the expanded costs and scope. |

|

August 2010 |

Claimed achievements—forecast reduction in red tape of $400 million, exceeding the July 2011 $256 million target but falling short of the $500 million target set for July 2012. |

|

Red Tape Reduction Program (RTRP), 2011–14 |

|

|

RTRP starting scope |

|

|

Scope similar to the previous program, covering administrative, compliance and delay costs imposed by state and local government regulation on businesses, not-for-profits, schools and hospitals and on individuals (where these costs affect employment). |

|

|

Targets, changes in scope and reported achievements |

|

|

March 2011 |

Target—$715 million yearly (25 per cent) gross reduction in combined administrative, compliance and delay burden estimate of $2.86 billion, to be delivered by July 2014. |

|

September 2011 |

Target clarification—includes $262 million of red tape reductions started but not delivered under previous government towards the $715 million target. |

|

October 2011 |

Refined scope—in terms of those affected by state and now local government regulation:

|

|

December 2012 |

Five regulators required to respond to Statement of Expectations 1 and identify red tape reduction initiatives for delivery by July 2014 (and included in RTRP). |

|

January 2013 |

Appointment of the Red Tape Commissioner. |

|

November 2013 |

RCM model updated, incorporating October 2011 scope and further expanding this to include all regulatory impacts on individuals. |

|

October 2014 |

Forecast results—program expected to reduce red tape by $1.04 billion by July 2014, exceeding the $715 million target. This estimate falls to $820 million if (as happened) government did not abolish the Victorian Energy Efficiency Target. |

|

December 2015 |

Estimated government spending on programs 2007–2015 is $53 million. |

|

Regulation Reform Program (RRP), 2015 onwards |

|

|

October 2015 |

Government committed to a 25 per cent reduction in red tape (estimated between $600 million and $1.6 billion) by July 2018:

|

Source: VAGO based on evidence provided from government.

1.4 Agencies' responsibilities

1.4.1 Department of Treasury & Finance

DTF is responsible for:

- advising the Treasurer and government on red tape reduction policy and guidelines

- whole-of-government support, coordination, monitoring and reporting on each of the red tape reduction programs and their measurement

- supporting regulators and departments in developing successive red tape reduction programs

- acting as a 'gatekeeper' regarding requirements to undertake regulatory impact statements (RIS) and legislative impact assessments (LIA) and advising the Treasurer on compliance with the Victorian Guide to Regulation.

1.4.2 Department of Premier & Cabinet

The Department of Premier & Cabinet (DPC) is responsible for informing policy and providing whole-of-government reporting on reform programs, including red tape reduction initiatives. DPC also supports the Premier in administering the Subordinate Legislation Act 1994 and is responsible for ensuring the integrity of the exemption process for RISs and LIAs.

1.4.3 Scrutiny of Acts and Regulations Committee

The Scrutiny of Acts and Regulations Committee (SARC) is an all-party Joint House Committee, which examines all Bills and subordinate legislation (regulations and legislative instruments) presented to Parliament. It does not make any comments on the policy merits of the legislation and it is required to apply non-partisan legislative scrutiny.

For primary legislation, the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 provides that SARC must report to Parliament whether any Bill is incompatible with human rights. SARC has no role in assessing LIAs or the grounds on which exemptions to preparing an LIA have been granted.

The Regulation Review Subcommittee of SARC reviews whether regulations comply with section 21 of the Subordinate Legislation Act 1994. This includes the RIS or the exemption from preparing an RIS and whether statutory rules are likely to result in administration and compliance costs that outweigh the intended benefits.

1.4.4 Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission

In September 2015 VCEC was abolished and its review functions were allocated to the Commissioner for Better Regulation (CBR). VCEC had:

- completed inquiries, including advice for the Treasurer on red tape reduction

- completed regulatory improvement studies, including red tape proposals and studies for supporting regulators in their pursuit of improved regulatory practices

- provided independent advice on the adequacy of measurements used to assess the change in regulatory burden and claimed savings.

1.4.5 Commissioner for Better Regulation

Established in September 2015, the CBR is supported by a secretariat housed in DTF. The CBR provides independent advice on matters of regulatory improvement and other regulatory matters as required by the Treasurer or the Secretary of DTF. The CBR's responsibilities include:

- assessing the adequacy of RIS and LIA

- providing independent advice on the adequacy of any measurements used to assess the change in regulatory burden for initiatives reducing red tape

- assisting agencies responsible for regulation with the design, application and administration of the regulation so they can improve its quality

- completing research on regulatory issues as specified by the Treasurer or the Secretary of DTF.

1.4.6 Red Tape Commissioner

The first Red Tape Commissioner (RTC) was appointed as an executive officer in January 2013 and was responsible for liaising with the business community to identify opportunities to reduce red tape, such as instances of poor regulatory design or overlapping, duplicated and unnecessary obligations.

The first RTC resigned in December 2014. A new commissioner was appointed in September 2015, and the RTC's overall remit remains the same. The RTC is supported by DTF.

The current RTC is required to report specific regulatory problems and recommendations for practical solutions to the Treasurer twice each year. Public release of these reports is at the Treasurer's discretion.

1.4.7 Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources

The Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR) was responsible for preparing government responses to the first RTC's proposals and providing administrative support from July 2013 until the resignation of the first RTC in December 2014. The RTC now sits within DTF, as was the case for the initial period of the first RTC. In addition, DEDJTR—and its predecessor, the Department of State Development, Business & Innovation—plays a key role in liaising with businesses.

1.4.8 Portfolio departments and regulators

These are responsible for:

- achieving their objectives efficiently, while understanding and minimising the burden imposed on the organisations they regulate

- meeting government's red tape reduction targets and reporting to portfolio ministers and government as required, on their progress towards these targets.

1.5 Audit objective, scope and agencies

1.5.1 Audit objective

The objective of the audit is to examine whether red tape reduction initiatives have been effective in reducing the burden of regulation by assessing whether:

- DTF has acquitted its responsibilities for successive red tape reduction programs by advising government on their design and effectiveness, supporting departments and regulators to achieve their goals, and verifying, reporting on and advising government on how to improve these programs

- the RTC between January 2013 and December 2014 had effectively contributed to reducing red tape by developing and prioritising proposals and clearly communicating the costs and benefits to government

- selected regulators can demonstrate that they have effectively reduced red tape by developing, implementing, evaluating and reporting on sound red tape reduction programs.

1.5.2 Audit scope

The audit examined government-sponsored red tape reduction programs between 2011 and 2015. It also examined advice to government, and the verification and reporting of red tape reduction from 2006 to 2016.

1.5.3 Agencies included in the audit

The audit includes agencies with whole-of-government responsibilities (DTF, DPC and the former VCEC), the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning (DELWP), DEDJTR, the RTC (initially in DTF, then DEDJTR and now in DTF), the CBR, and the following regulators:

- WorkSafe

- VicRoads

- Consumer Affairs Victoria, part of the Department of Justice & Regulation

- Environment Protection Authority Victoria, under the DELWP portfolio.

These regulators were selected in consultation with DTF, having been assessed as high-impact regulators.

1.6 Audit method and cost

The audit was conducted in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The cost of the audit was $445 000.

1.7 Structure of this report

This report has further parts:

- Part 2 examines whether the agencies included in this audit have been effective in reducing red tape

- Part 3 describes the current and future challenges facing responsible agencies in better controlling red tape and recommends what they need to do to meet these challenges and improve the effectiveness of red tape reduction.

2 Effectiveness in reducing red tape

At a glance

Background

Red tape reduction programs have existed in Victoria for over a decade and have progressively expanded the group of beneficiaries. Each program has had a set target, represented in either percentage or monetary terms, and these targets have been determined to have been met or exceeded. Burden reduction has been measured through monetary savings to program beneficiaries and recorded as an overall program saving by government rather than measured by individual portfolios.

Conclusion

The expanding focus of successive programs, their reliance on estimated savings, and weak controls underpinning the growth of regulation reduces the reliability of claimed monetary benefits. The transparency and accountability of the reported achievements is compromised by the insufficient evaluation of implementation and a lack of verification of the savings with the targeted beneficiaries. Although these programs have targeted initiatives that contribute to the overall reduction in red tape, evidence about their management and effectiveness falls short of confirming the scale of benefits claimed by agencies in reporting to government by the Department of Treasury & Finance.

Findings

- Reducing unnecessary regulatory burden has been a sustained focus of government since 2006.

- Departments and regulators have adhered to established guidance and methods of recording burden reduction for the intended beneficiaries.

- The Department of Treasury & Finance has consistently reported to government on the progress towards the set targets.

- There has been insufficient evaluation of program achievements and limited understanding of true costs and risks of adverse outcomes.

2.1 Introduction

Unnecessary or inefficient regulation has a significant effect on economic growth. Since 2006 red tape programs have focused departments and regulators on minimising this burden.

This Part examines whether agencies' efforts to control and reduce red tape have been effective. Specifically, we examined the performance of:

- the Department of Treasury & Finance (DTF) in advising government on, overseeing and supporting red tape reduction programs

- the previous Red Tape Commissioner (RTC) in consulting those affected by red tape and developing proposals for government's consideration

- the four sampled regulators by assessing whether they could demonstrate the basis for their proposals and the realisation of their intended benefits.

The positive practices and the weaknesses identified often applied across all these entities. For this reason, the findings described in Section 2.3 are structured in terms of key themes rather than by type of agency.

2.2 Conclusion

Weaknesses in the assessment and evaluation of red tape reduction programs, coupled with the absence of fully effective controls to prevent the creation of additional red tape, have undermined the effectiveness of the various red tape reduction programs in place since 2006.

Although these programs included targeted initiatives that contributed to the overall reduction in red tape, the evidence about their management and effectiveness falls short of confirming the scale of benefits claimed by agencies in reporting to government by DTF. In addition, gaps and weaknesses in regulatory review processes mean new or renewed regulation has added or maintained regulatory burden that has not been adequately tested to assure it is necessity or efficiency. This risks negating some of the gains from red tape reduction programs. The extent to which additional regulation has offset the gains from red tape reduction programs is unclear because it has not been adequately measured.

These factors may explain why non-government organisations consistently assert that the red tape burden has increased, despite government claims of multi-billion dollar savings from red tape reduction programs.

2.3 Overall findings

Our review of how DTF, the first RTC and a sample of regulators acquitted their red tape responsibilities identified positive practices but also clear weaknesses that have diminished the effectiveness of these programs and that need to be addressed.

We found several positive practices:

- Sustained government and DTF focus on red tape reduction—this focus drives activity across departments and regulators to implement initiatives.

- A systematic approach to estimating red tape impacts—DTF has developed a systematic approach, which it regularly updates, to help agencies estimate red tape impact. Regulators largely applied the mandated approach to estimating the reduction in red tape and, before 2011, to documenting overall burden reduction plans.

- Regular reporting by DTF to government on progress towards targets—DTF reporting describes individual initiatives and many of the risks threatening success.

- Examples of targeted consultation—there are some examples of targeted consultation with the intended beneficiaries of red tape reduction programs.

There are weaknesses undermining the impact of red tape reduction programs:

- An incomplete understanding of red tape and how this burden has changed over time with new or renewed legislation—this incomplete understanding applies across government, by portfolio and for individual regulators, making it difficult to confirm that targets are appropriate and that programs have been effective in reducing the net burden imposed by red tape.

- A lack of assurance about the effectiveness of existing controls—this has the potential to result in the creation of additional red tape through the passage of new regulation.

- Partial assessment of proposed red tape initiatives—assessment focuses on estimating the reduction in the burden without adequately describing implementation costs and the threats to regulatory outcomes.

- Absence of meaningful evaluation of these programs over the past decade—this means that it is unclear whether forecast benefits have been realised, and whether there were any unforeseen impacts.

- Partial and inconsistent consultation with intended beneficiaries—engagement with intended beneficiaries has not been effectively structured across government.

- Lack of transparency and inadequate public reporting—reporting to the public has been occasional and sparse, focusing on claimed savings and showcasing selected case studies. The absence of sufficient information on the changing scope and programs' component initiatives make the content and impacts of these programs impenetrable to citizens and targeted beneficiaries outside of government.

The remainder of this Part describes in greater detail these positive attributes and weaknesses, while Part 3 focuses on the actions needed to improve the management of red tape given the challenges regulators face.

2.4 Positive attributes of red tape programs

2.4.1 Consistent long-term focus on red tape

Changes in government in the past decade have been followed by early commitments to specific percentage and dollar targets, and time lines for reducing red tape. This has maintained a focus on red tape and generated a higher level of activity than if departments and regulators were left to reduce red tape as part of their normal activities.

2.4.2 A structured and supported approach to red tape

DTF has devised, communicated, supported and updated a structured approach for agencies to follow in proposing red tape reduction initiatives.

DTF's approach has focused on assessing the expected benefits and monetising the impact of reducing red tape by applying a Standard Cost Model. Since mid‑2009, DTF adopted the Regulatory Change Measurement (RCM) model which has, through several versions, also incorporated an expanded set of red tape costs. This approach, if applied as intended, produces logical and understandable monetary estimates of red tape reduction.

DTF supported departments and regulators by:

- communicating reduction targets and time lines and their expected contribution

- identifying potential areas of red tape reduction

- providing training and guidance about how to develop and assess initiatives

- together with the former Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission (VCEC), reviewing agencies' proposals

- responding to agencies' feedback on practical difficulties in achieving targets.

For all three red tape programs, DTF communicated government's mandated targets and time lines. It also set portfolio targets for the first two programs but conceded that these were not evidence-based and it did not have sufficient information to set specific portfolio targets.

DTF provided adequate support and updated guidelines to help agencies assess initiatives, including several versions of model documentation explaining how to assess and report on initiatives. These complemented DTF's Victorian Guide to Regulation publications.

DTF also regularly communicated with departments to check on progress, provide training and offer informal support in identifying and developing red tape initiatives. In addition, VCEC was available to advise departments and regulators about red tape.

While this support and guidance is positive overall, it is offset by the lack of coverage of the costs of initiatives and the practical challenges of continually achieving ambitious targets.

2.4.3 Regular advice to government on progress and risks

DTF played the lead role in advising government about:

- the basis for red tape programs' scope, targets and content

- progress towards agreed goals

- how this should be communicated to the community.

The Department of Premier & Cabinet (DPC) also provided advice on these issues as part of its role of briefing the Premier and government.

DTF regularly reported to successive governments on red tape programs. These reports described progress on specific initiatives and their contribution to reducing red tape. In addition, DTF and DPC regularly raised risks relating to:

- the ambitious targets set by successive government, in terms of the scale of red tape reduction and the time lines for their achievement

- the need to appropriately offset additional red tape created by new legislation and the need to improve the controls used to assess and address this risk

- regulated parties' perceptions of programs and the need to adequately communicate progress.

While the frequency and detail of progress reports usefully advised government about these issues, the overall quality of advice was mixed. In Section 2.5 we explain where DTF's advice should be improved.

2.4.4 Consultation with affected parties

Two objectives of the RTC are to communicate the government commitment and progress toward cutting red tape, and to encourage business people and industry associations to come forward with their red tape concerns. The RTC's key audiences were Victorian businesses, industry associations, members of the community, regulators, as well as national and interstate businesses, industry associations and politicians.

From the time of the first RTC appointment until October 2014, the RTC reportedly consulted with many business sectors, meeting with around 80 individual companies, associations and other business organisations. The RTC also reportedly met with individuals on red tape concerns on a regular basis.

2.5 Weaknesses undermining program outcomes

2.5.1 Lack of clarity about programs' targets and scope

Successive governments have, as a matter of policy, set and publicised time lines and targets for reducing red tape by 25 per cent. DTF estimated what these targets meant as an equivalent monetary reduction in red tape and, for all but the current red tape program, these yearly monetary targets were publically announced.

DTF regularly reported to government on the expected monetary impacts of red tape initiatives in comparison to these targets, and government publicised these overall expectations through an annual industry presentation.

The significant level of uncertainty around these estimates of red tape and the significant changes in the scope of red tape programs undermine the validity and clarity of these targets:

- Such targets convey a level of precision that is misleading and that, at the very least, needs to be fully explained to each program's intended beneficiaries.

- The breadth and diversity of those now covered by red tape programs makes a single, unexplained target of little meaning to these intended recipients.

DTF should advise government about these risks that potentially undermine the effectiveness of red tape programs and provide options for risk mitigation.

Quantifying red tape as the basis for setting targets

DTF advice to the current government is consistent with the advice provided over the past decade—a baseline of Victoria's regulatory burden has not and cannot be readily established. Estimates of the cost of the administration, compliance and delay burden now range between $2.4 and $6.4 billion. In addition, DTF confirmed its earlier advice that there is significant difficulty in accurately assigning a share of Victoria's total burden to specific departments or portfolios.

This issue was identified many times throughout the past decade by DTF, but it advised government against more detailed work to better understand the burden because, due to the ambitious targets and tight time lines of successive programs, it lacked the time to undertake this. They also advised that this work was expensive and would provide marginal benefit. DTF did not provide evidence substantiating its assertions about the high cost and low benefit of a reliable baseline measure and, before late 2015, we found no advice adequately explaining the implications of setting and publicly communicating red tape reduction targets.

The use of targets in this way, without explaining their basis or margin of error, risks misleading stakeholders and undermines the transparency and integrity of these programs. In addition, the change from net reduction targets—which take account of the red tape introduced by new legislation—to gross reduction targets has not been adequately explained to stakeholders.

DTF has not formulated options for more precisely estimating the red tape burden nor for advising government on options to address risks to the integrity, transparency and effectiveness of these programs.

Changing coverage of red tape programs

The scope of red tape programs has expanded significantly since 2006. Rather than just covering administrative costs, it now also includes compliance and delay costs. It also goes beyond businesses and not-for-profit organisations to include government service providers, where the private sector also provides a service—such as hospitals and schools—and private individuals.

Intended beneficiaries of red tape programs are not receiving sufficient information to understand how the programs are meant to help them. It is not clear whether these stakeholders understand the scope and content of red tape programs and can relate to what an overall 25 per cent reduction in red tape should mean for them.

The overall focus of red tape programs remains unlocking economic growth. However, the expansion to include schools, hospitals and individuals creates a risk of confusing the public understanding of these programs and diluting this focus. For example, the economic impact of reducing red tape in schools is likely to be less direct than if red tape is reduced for small businesses.

The expansion in program coverage brings into play a wider range of valuable social and indirect economic benefits. DTF needs to advise government how red tape reduction can be made more accessible and meaningful to these diverse groups. One option for doing this is to create streams within the overall program targeting these different beneficiaries. This would allow red tape actions and reporting to be targeted to the specific needs of these groups.

2.5.2 Controlling the creation of additional red tape

A constant theme in DTF's advice about red tape reduction programs is that ministers and departments need to ensure that additional regulation does not add to the unnecessary or inefficient regulatory burden targeted by these programs. DTF's advice and VCEC inquiries show that the additional or continuing burden from new or renewed legislation is significant and the controls for eliminating red tape are unlikely to be fully effective.

This is particularly the case for the review of primary legislation—where there is a lack of transparency about the rigour of scrutiny applied to detecting and addressing red tape.

This is a significant issue because VCEC and DTF estimates of the additional regulatory costs created in a typical year imply that the additional burden is likely to have been at least equal to claimed savings from red tape programs.

This is not to say that the additional burden was unnecessary or inefficient. However, weaknesses in the review of new legislation mean government cannot be assured that unnecessary or inefficient regulatory burden has been identified and minimised.

It is critical that DTF and DPC demonstrate that controls preventing additional red tape are effective. Improved assurance is also needed over the effectiveness of current controls for both primary and subordinate legislation.

Controls applied to new regulation

Figure 1B in Part 1 summarises the processes applied to control the creation of additional red tape through legislation. Where regulation is seen as necessary, costs and benefits are assessed through:

- a regulatory impact statement (RIS) for subordinate legislation, where the regulation imposes a significant economic or social burden ($2 million or more) on a sector of the public (unless an exemption provision applies)

- a legislative impact assessment (LIA) for primary legislation, where the regulation imposes potentially significant effects ($2 million or more) for business or competition (unless exempted).

For subordinate legislation, the Regulation Review Subcommittee of the Scrutiny of Acts and Regulations Committee (SARC) checks that regulations and legislative instruments made under the Subordinate Legislation Act 1994 conform to its requirements,

Since September 2015, the Commissioner for Better Regulation (CBR) has provided independent advice as to the adequacy of RISs and LIAs (previously VCEC fulfilled this role).

Potential gaps in the application of current controls

When subordinate or primary legislation is prepared with either a published RIS or a government-considered LIA, there is some assurance that its burden has been considered. This assurance ensures that focused analyses of the costs and benefits are completed and independently assessed by the CBR and, formerly, by VCEC. However, while SARC's Regulation Review Subcommittee checks whether RISs comply with the requirements of the Subordinate Legislation Act 1994, it does not usually validate cost and benefit assumptions and calculations.

Where agencies are exempted from preparing an RIS or LIA, the controls applied are much weaker, and there is insufficient assurance that new red tape is detected and addressed.

Figure 2A shows that for subordinate legislation created from 2011 to 2014:

- between 4.7 and 11.4 per cent of regulations were required to prepare an RIS—the 2014 figures show that agencies asserted that 98 of the 202 exemptions (49 percent) would not impose a significant economic or social burden.

- between 0 and 6.3 per cent of legislative instruments were required to prepare an RIS—in 2014 agencies asserted that 43 of the 60 exemptions (72 per cent) would not impose a significant economic or social burden.

Figure 2A

Subordinate legislation passed and number

of regulatory impact statements required

Year |

Regulations |

RIS |

Per cent |

Legislative instruments |

RIS |

Per cent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2011 |

166 |

12 |

7.2 |

24 |

0 |

0.0 |

2012 |

167 |

19 |

11.4 |

55 |

1 |

1.8 |

2013 |

180 |

12 |

6.7 |

70 |

2 |

2.9 |

2014 |

212 |

10 |

4.7 |

64 |

4 |

6.3 |

Source: VAGO based on SARC annual reviews 2011 to 2014.

SARC provides a definitive summary of the subordinate legislation passed, whether agencies had to prepare an RIS, the basis for exemptions, and whether agencies have complied with the Subordinate Legislation Act 1994. It does not normally test the validity of the assumptions and analysis justifying exemptions. For example, it does not assess whether assertions of an insignificant burden are adequately justified by evidence.

The controls—in terms of exemption criteria, their application and reporting—are far less clear and transparent for LIAs. LIAs are considered within government and not published. There is no documentation describing the exemption criteria or how exemptions are determined. However, the 2014 Victorian Guide to Regulation stated that a Bill may be exempted if the impacts on business/competition are not expected to be significant, or if the Premier decides to exempt a Bill from the requirement.

Unlike for subordinate legislation, we found no consolidated record describing the review of primary legislation and the basis for exempting Bills from undertaking an LIA. VCEC provided a summary of its LIA reviews—it completed 15 LIA reviews between 2011 and 2014, covering 5 per cent of the 332 pieces of primary legislation passed. It is not evident that VCEC received all the LIAs prepared, and the basis for exempting more than 90 per cent of primary legislation from this type of review is unclear.

The expanded scope of red tape programs means the narrow LIA definition of 'significant effects', used until 2014, covering business and competition was important. The narrower LIA definition risked exempting primary legislation that impacted these groups because the legislation did not directly impact business. In 2014 this definition was amended to require preparation of a LIA where it imposes a potentially significant economic or social burden on a sector of the public. The requirement for an RIS to be undertaken where legislation imposes a significant social or economic burden will capture impacts on all the red tape programs beneficiaries—schools, hospitals and private individuals.

Significance of additional red tape burden

Additional red tape created between 2006–07 and 2015–16 is likely to have matched claimed savings of at least $3.1 billion during this period.

These estimates are based on information from VCEC and DTF that shows that between $70 million and $100 million in regulatory costs was added each year from 2006–07 to 2015–16. This adds a cumulative total of:

- $3.8 billion if the lower estimate applies

- $5.5 billion if the higher estimate applies.

Based on DTF's claims, Reducing the Regulatory Burden (RRB) and the Red Tape Reduction Program (RTRP) reduced red tape by at least $3.1 billion in total over this period, based on assertions that:

- the RRB was expected to achieve annual and ongoing savings of $400 million per year in full from July 2011

- the RTRP was expected to achieve annual and ongoing savings of $558 million per year (taking into account the overlap between programs).

Agencies' advice on the need for improved controls

Figure 2B shows DTF, DPC and VCEC consistently and repeatedly identified the need to better control new red tape and the risk this would diminish program benefits.

Figure 2B

Effectiveness of controls on additional red tape

Date |

Commentary |

|---|---|

Mid 2006 to March 2007 (RRB program) |

|

2007 to 2010 (RRB program) |

|

2011 to 2014 (RTRP) |

|

Oct 2015 (Regulation Reform Program) |

|

Source: VAGO from DTF and DPC advice.

2.5.3 Incomplete assessment framework

For government to decide on a proposal, it needs to understand:

- the benefits

- the expected impact on the red tape burden

- the magnitude of set up and ongoing costs and how these will be funded

- any significant risks affecting regulatory outcomes.

DTF's approach has focused on assessing the expected benefits through the application and review of the Regulatory Change Measurement (RCM) model. However, this does not require agencies to report on the initiatives' costs and the potential risks to regulatory outcomes. Agencies occasionally raised the risks inherent in proposals and the funding required, but consideration of these issues is not built into current assessment processes—and this needs to change.

DTF advised that the assessment of red tape initiatives is done at the departmental level and informs ministers' decisions about whether to proceed. This assessment includes an examination of the costs and risks to regulatory outcomes. From our work with departments and regulators, we remain unassured that costs and risks have been adequately considered and found this is due in large measure to DTF's requirements.

Under the 2015 Regulatory Reform Program (RRP), independent scrutiny and verification of proposals' estimated benefits will no longer be required. On balance, we think this is a backward step and there is no information about how DTF will manage the risk of lower-quality estimates.

Benefits

The completed RCM models we reviewed provided reasonable and logical estimates of the expected red tape reduction burden, but RCM models were not completed or verified for all the savings estimated and reported to government.

The RCM models provide the opportunity to estimate, in a structured way, the expected impacts on red tape. Prior to 2015, VCEC reviewed RCM models that claimed benefits of $2 million or more, and DTF reviewed other lower-value initiatives.

We are concerned that the level of scrutiny has been reduced for the RRP. DTF advised the government to stop the independent scrutiny of RCM models because, while formal verification can strengthen the estimation process, it:

- did not generally lead to large revisions compared to agencies' early less-formal estimates, and revisions usually showed first estimates as being conservative

- can impose a significant internal red tape burden on departments

- leads to the unnecessary engagement of consultants to prepare estimates

- adds unnecessary delays to the measurement and reporting process.

In presenting the revised approach, DTF did not describe how the risks of this diminished level of scrutiny will be managed. The removal of external scrutiny should be accompanied by an appropriate measure that can provide satisfactory assurance on the department's assertions of estimated savings.

Costs and funding

Estimated costs of developing and implementing red tape initiatives have not been required by DTF over the 10 years that red tape programs have been implemented, and DTF has little visibility of the expected cost of proposed red tape programs. During the first program (the RRB program), government provided $53 million to support reviews to develop initiatives as incentive payments for departments with proposals to reduce red tape. Since 2011, DTF has maintained that red tape reduction should be funded as part of regulators' normal business activities.

In late 2011 and 2012, at least three agencies raised the potential impacts of this funding change, identifying $16 million in red tape savings that were dependent on securing budget funding.

Responding to agencies' comments about the lack of funding for the RTRP and the potential impact on red tape initiatives, DTF stated that:

- removing existing regulatory requirements is less costly than previous efforts to reduce the burden by implementing information and communications technology solutions

- as regulatory requirements are reduced, certain regulatory oversight functions will also decrease, freeing up departmental and regulator resources.

We have seen no evidence to substantiate these assertions.

DTF did not seek to fully understand the cost of red tape reduction initiatives or the impacts on other regulatory activities undertaken by departments and regulators prioritising red tape reduction initiatives. At a minimum, proposals should estimate the costs and impacts on other programs so that DTF has a full appreciation of the relevant factors when deciding on the content of red tape programs. Such factors include the evaluation of complex systems and problems, design, implementation—including retraining, restructuring teams, and redesigning systems—and the subsequent evaluation and monitoring to manage risks and maintain delivery of regulatory outcomes.

Risks to regulated outcomes

The current assessment framework does not require agencies to identify potential risks that would diminish regulatory outcomes. While we have seen examples where departments have rejected initiatives because of the risks to outcomes, the requirement to do this should be a mandatory part of the assessment. For example, in September 2012, a minister wrote to the Treasurer opposing reforms to swimming pool testing because stakeholders did not support the proposed changes.

Similarly, in late 2011, a proposal for a long-life vehicle registration sticker was put on hold by the former Department of Transport because of concerns raised by Victoria Police and VicRoads. Despite these concerns, there has been a subsequent initiative to remove physical registration stickers. In this instance, the physical sticker's role as a visual reminder to renew registration, and the social impact and inconvenience caused by its removal, were not sufficiently considered against the time savings determined by the department. If these risks are not considered, the estimated savings may not be fully achieved or may be offset by other adverse social or economic outcomes.

Contribution of the Red Tape Commissioner and regulators

The first RTC clearly engaged the business community and other stakeholders to help inform the development of red tape reduction proposals. However, the proposals were not subject to a structured assessment to determine costs, burden reduction benefits and risks. We did not find evidence that the former RTC consulted departments and regulators as this was left to the former Department of State Development, Business and Innovation. We also did not find evidence that departments and regulators produced information on the costs to government and risks to regulatory outcomes for the proposals identified by the RTC.

The sampled regulators had developed an understanding of the organisations they regulated and, through their day-to-day operations, an understanding of the burden affecting them. At the outset of the RRB program, we saw evidence from two agencies of three-year plans that included analysis of how legislation would impact relevant organisations.

However, information on the costs and risks of initiatives was absent, in large part, because these were not routinely required as part of the assessment process. In addition, we found cases where the assumptions underpinning estimates had not been adequately tested.

2.5.4 Absence of adequate evaluation

No matter how good the framework for estimating program impacts, well-structured, proportionate and timely evaluation is essential to verify outcomes and identify the lessons that will improve future performance. In the context of red tape programs, this type of approach to evaluation has been lacking over the past decade and, as such, there is limited confidence in the extent of the red tape savings claimed to have been delivered. Unverified estimated savings forecasts were 'banked' as achieved benefits.

At an initiative level, some agencies claimed that completion of RCM models shortly after implementation—rather than before—represents a form of evaluation. However, an RCM model's reliance on assumptions and estimates does not provide sufficient assurance like an evaluation after the completion of activity or regulatory change would.

At a program level, DTF needs to design an evaluation for the regulation reform program that tests the realisation of benefits, detects any unforeseen impacts, and identifies the improvement lessons for a representative sample of initiatives.

The latest 2015 program commits DTF to leading an evaluation of the Stage 2 Statement of Expectation (SOE) program by early 2016. The SOE guidelines had foreshadowed a post-implementation review by DTF which was to be completed in 2015, ensuring sufficient time for findings to be taken into account in developing a successor policy. This did not occur and, in response to our request for a progress report including the time lines for completing this evaluation, DTF provided an outline of its intended approach and broad time lines. The level of detail provided does not constitute sufficient evidence about the rigour and quality of this evaluation. This emphasises the need for DTF to upgrade its approach to program evaluation and build this into programs from the initial stages.

The current approach falls short of evaluating the most recent RTRP in a structured and defensible way, which would require the clear definition of objectives, outcomes and key performance indicators together with a structured, resourced program for setting a baseline and measuring progress towards defined objectives.

In October 2015, one department suggested that DTF should plan to evaluate the benefits realised for those targeted by red tape reduction programs. DTF considered that departments should evaluate their own initiatives and is planning to use yet‑to‑be‑implemented performance measures and a survey of business perceptions of regulation to evaluate the effectiveness of the wider regulation reform program.

Given the failure of DTF, departments and regulators to adequately evaluate red tape reduction initiatives over the past decade, this approach is not sufficient. A well‑designed and effectively executed survey of business community perceptions is a positive step forward. However, the decision to remove independent assessment of savings estimates, along with reliance on departments to voluntarily and consistently evaluate initiatives, presents a significant risk to the reliability, consistency of approach and integrity of estimates. This risk and appropriate mitigations should have been presented to government.

We did not find that these program evaluation deficiencies had been covered by departments and regulators. Instead, we found a lack of adequate and proportionate evaluation across departments and regulators.

2.5.5 Inconsistent stakeholder engagement and reporting

Inadequate consultation with those affected by red tape programs, and infrequent and sparse public reporting has led to a lack of meaningful input from those outside of government and a lack of transparency and understanding about the savings and benefits for beneficiaries. Given the government's clear commitment to transparent and evidence-based decision-making, DTF needs to advise on the options for making the current program more inclusive, understandable and transparent.

These comments apply to both the beneficiaries of red tape programs and the departments and regulators collectively responsible for achieving targets.

Consulting with and informing intended beneficiaries

Consultation over the past decade has been uneven and not driven by a clear and well‑defined stakeholder engagement strategy. We have seen examples of occasional roundtables, annual presentations to the Victorian Employers' Chamber of Commerce and Industry and intensified business consultation as part of the former Department of State Development, Business and Innovation's 2011 project to engage business in regulatory reform. The first RTC also focused on business engagement.

While the RTC and regulators consulted affected organisations as part of their day‑to‑day operations, these activities did not provide the type of structured approach that would have helped better target red tape programs while improving stakeholders' input into and understanding of the benefits.

Taken together, whole-of-government and regulator initiatives did not form a consistent and predictable approach to consultation in a way that significantly shaped successive red tape reduction programs.

The 2015 RRP committed to an annual business perception survey but did not define a stakeholder engagement strategy that would provide affected organisations with the type of predictable consultation opportunities needed.