TAFE Governance

Overview

Due to a major policy shift in the last decade TAFE institutes now operate in a competitive market. The Holmesglen Institute of TAFE is the largest TAFE institute in Victoria. It has been very successful in the new market.

In December 2010, the Holmesglen Institute of TAFE made a loan of $6.5 million to a financially distressed Registered Training Organisation as the first step in an acquisition strategy. In early 2011 the Holmesglen board chose not to proceed with the acquisition and began negotiations with a new buyer to recover its loan. Skills Victoria intervened and sought assistance from the Department of Treasury and Finance to negotiate the loan repayment. This was finalised in May 2011 leaving Holmesglen’s accounts impaired by $3 million.

The Holmesglen board lacked critical information necessary to make an informed decision on the wisdom of providing a loan and pursuing an acquisition. It acted outside its legal authority in making the loan, by not following government directions and clear signals about low risk in managing public funds.

The loan occurred in an environment lacking oversight and leadership from Skills Victoria. There were no policies to guide commercial activity by TAFE institutes and where requests for clarity were sought by Holmesglen, Skills Victoria did not respond. There was a history of inadequate and ineffective communication between Holmesglen and Skills Victoria.

TAFE Governance: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER October 2011

PP No 79, Session 2010–11

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my performance report on TAFE Governance.

Yours faithfully

![]()

D D R PEARSON

Auditor-General

26 October 2011

Audit summary

In Victoria, Technical and Further Education (TAFE) institutes offer vocational programs to meet the needs of industry, individual students and the general community. Each TAFE institute has a high degree of autonomy and is governed by a board which is accountable to the Minister for Higher Education and Skills for its educational and financial performance.

The Victorian Skills Commission (VSC) has a role to oversee the Victorian training system and it delegates many of its functions to Skills Victoria, a business unit in the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD). Skills Victoria supports TAFE institutes to meet government goals and targets and also manages the government’s relationship with the institutes.

There have been major policy changes affecting TAFE institutes over the past ten years. This has seen a shift away from a traditional model of TAFE institutes using block funding from government to provide services to their local community. Today, institutes operate in a contestable market where they are required to compete with other Registered Training Organisations (RTO), both public and private, for a share of the student market. Institutes are now encouraged to attract revenue in domestic and international markets.

The Holmesglen Institute of TAFE (Holmesglen) is one of Victoria’s 14 stand-alone TAFE institutes. It has been successful in expanding into overseas markets, developing new and innovative courses, and taking on other troubled TAFE operations, turning them into viable campuses.

In the course of the annual audit of Holmesglen’s 2010 financial statements, a financially material loan of $6.5 million made by the institute to an RTO in financial distress, as the first step in an acquisition strategy, was identified. Holmesglen’s board lacked the critical information necessary to make an informed decision on the wisdom of this transaction.

In early 2011 the Holmesglen board resolved not to proceed with the acquisition, and began negotiations with a new buyer to recover its loan. Skills Victoria intervened and sought assistance from the Department of Treasury and Finance to negotiate the loan repayment. This was finalised in May 2011 and Holmesglen’s accounts were impaired by $3 million.

This audit examined the legal authority and financial prudence of Holmesglen’s decision to enter into this arrangement as well as broader, systemic questions about the effectiveness of oversight of the sector.

Conclusions

There was inadequate and ineffective engagement between Holmesglen and Skills Victoria over a number of years leading up to, and during, the failed acquisition strategy. This was symptomatic of Skills Victoria’s general failure to provide sound oversight and leadership of the TAFE sector during a period of significant strategic repositioning. Leadership was needed to ensure that expectations of TAFE institutes were consistent with public sector accountability frameworks and to provide assurance on the efficient and transparent use of public resources.

Holmesglen’s acquisition strategy and provision of the loan to the RTO did not adhere to a Standing Direction set by the Minister for Finance and was outside the Victorian government’s policy on the management of public funds. The board was aware of this Standing Direction and made the decision that the Direction did not apply to it without obtaining clarity from Skills Victoria as the oversight body, its responsible minister or the Minister for Finance.

Although the board acted in good faith during its deliberations, it did not proactively engage with Skills Victoria during the transaction, and by failing to do so it fell short of the expectations of propriety for a public entity.

The board did not demonstrate financial prudence in entering into this arrangement. It lacked significant information on the RTO when making its decision to provide a loan, and as such it was unable to sufficiently analyse risk against return. It sought to protect Holmesglen’s funds through initiating a fixed and floating charge over the RTO. However, sufficient regard was not given to the effectiveness of this charge as a mitigation strategy and it ultimately proved to be ineffective.

The VSC has no processes in place to gain assurance that Skills Victoria is exercising its functions effectively or efficiently. There were significant gaps in Skills Victoria’s knowledge of Holmesglen’s strategies and actions, and poor communication between these agencies exacerbated the situation.

Although overarching strategic polices have been documented and communicated to the sector, comprehensive lower level operational policies have not been developed or appropriately promoted to the sector.

In the absence of predetermined policies, Holmesglen sought guidance from Skills Victoria on several issues, however, clear and timely direction was not provided. When Skills Victoria identified concerns with Holmesglen’s prior commercial undertakings, definitive action was not taken. Similarly, emerging issues affecting the whole TAFE sector were not identified or resolved in a timely manner. The ad hoc communication prior to and during the financial transaction, and its lack of clearly documented policies means that Skills Victoria cannot provide assurance that similar situations have not occurred.

Skills Victoria has not demonstrated that it has adapted its oversight role to respond to the contestable market model. This transition was always going to be challenging, for both TAFE institutes and for Skills Victoria. However, as the key oversight body, Skills Victoria needed to drive the change.

These oversight and leadership deficiencies by Skills Victoria need to be addressed as a priority if the TAFE sector is to move forward and play the role envisioned in the contestable vocational education and training market policy.

Findings

Holmesglen

All public entities, such as TAFE institutes, have a responsibility to ensure that public funds are being used economically, efficiently and effectively. Public entities are accountable for the manner in which they exercise the authority given to them by government.

Holmesglen’s strategy to acquire an RTO raised a number of new issues but Holmesglen did not make Skills Victoria aware of its decision to loan money as part of an acquisition strategy. This lack of engagement with Skills Victoria resulted in Holmesglen undertaking a strategy that was not supported by government or government financial management policy and did not adhere to a Standing Direction from the Minister for Finance. This Standing Direction constrains investment of public entities to only low-risk transactions by requiring all investments and financial arrangements to be made with state entities, or with entities that have a credit rating the same or better than the state’s. The RTO did not meet this criterion.

Holmesglen provided the $6.5 million loan to the RTO as part of an acquisition strategy before undertaking due diligence. In deciding to make the loan before due diligence was completed, the Holmesglen board put public money at risk by inadequately considering the likely need of repayment should the acquisition not proceed, which was the eventual outcome. Holmesglen lacked crucial information to inform its decisions, including an understanding of the value of the RTO, the likely income return and timing of the return, and the liquidity and marketability of the investment. Without this information the board’s analysis of the risk versus the potential return was limited. Although the board appreciated this investment was high risk, the financial arrangement by Holmesglen was not prudent and resulted in an impairment of $3 million of public money.

The new contestable model of vocational education and training provision requires TAFE institutes to combine private sector behaviour, such as entrepreneurial pursuits, with public sector requirements for accountability. Exactly how this was to be achieved was never clearly outlined by Skills Victoria. Holmesglen determined its own approach for balancing entrepreneurship against accountability and, up until this transaction, had been operating successfully on this basis for some time. This operating style did not include effective communication with Skills Victoria.

Oversight of the sector

As part of DEECD, Skills Victoria has policy responsibility for the TAFE sector and specific functions delegated to it by the VSC. This includes negotiating performance agreements and advising the minister on issuing guidelines or Ministerial Directions to TAFE institutes.

The case study of the Holmesglen financial transaction has demonstrated that Skills Victoria has failed to provide effective oversight of the TAFE sector.

Skills Victoria has not developed the new skills required to oversee TAFE institutes that now operate as more autonomous bodies competing with other training providers. The reforms required clarity about changed roles and responsibilities, yet, despite repeated reviews finding the need for greater role clarity, the problem has not been addressed. Confusion about roles and boundaries is evident in Skills Victoria’s belated involvement in the events that led to the loan repayment arrangement.

As a result of the Holmesglen financial transaction, Skills Victoria sought legal advice from the Victorian Government Solicitor’s Office about the loan and acquisition powers of TAFE institutes. This advice revealed a fundamental mismatch between the new policy, which encourages TAFE institutes to be entrepreneurial and seek opportunities interstate and overseas, and current legislation, which requires their function to be providing education and training to Victorians.

The relationship between Skills Victoria and Holmesglen is poor and characterised by limited communication and mutual distrust. Communication by Skills Victoria has typically been undocumented, including crucial information such as policy intentions, feedback on Holmesglen’s actions, expectations regarding information flow, and minutes from key meetings.

The VSC receives regular reports from Skills Victoria about the performance of the TAFE sector but has inadequate processes in place to assure itself that the functions delegated to Skills Victoria have been effectively performed.

Implications for the TAFE sector

Holmesglen has a history of being the TAFE institute to implement successful new and innovative strategies that are subsequently adopted by other TAFE institutes. Despite the legal authority and financial prudence issues, Holmesglen’s acquisition strategy was another attempt to adapt to the changing vocational education and training environment. Other TAFE institutes may also wish to pursue innovative strategies in the future that may take them into untested areas of activity.

Skills Victoria has not provided the leadership necessary to resolve its position on a number of key commercial issues central to how TAFE institutes can compete effectively with private training providers. The absence of defined parameters around commercial activity creates confusion and results in limited freedom for institutes to react and respond in a competitive way to each other and to the private sector. The lack of guidance is an even greater issue for TAFE institutes with smaller surpluses and less commercial knowledge than Holmesglen.

Recommendations

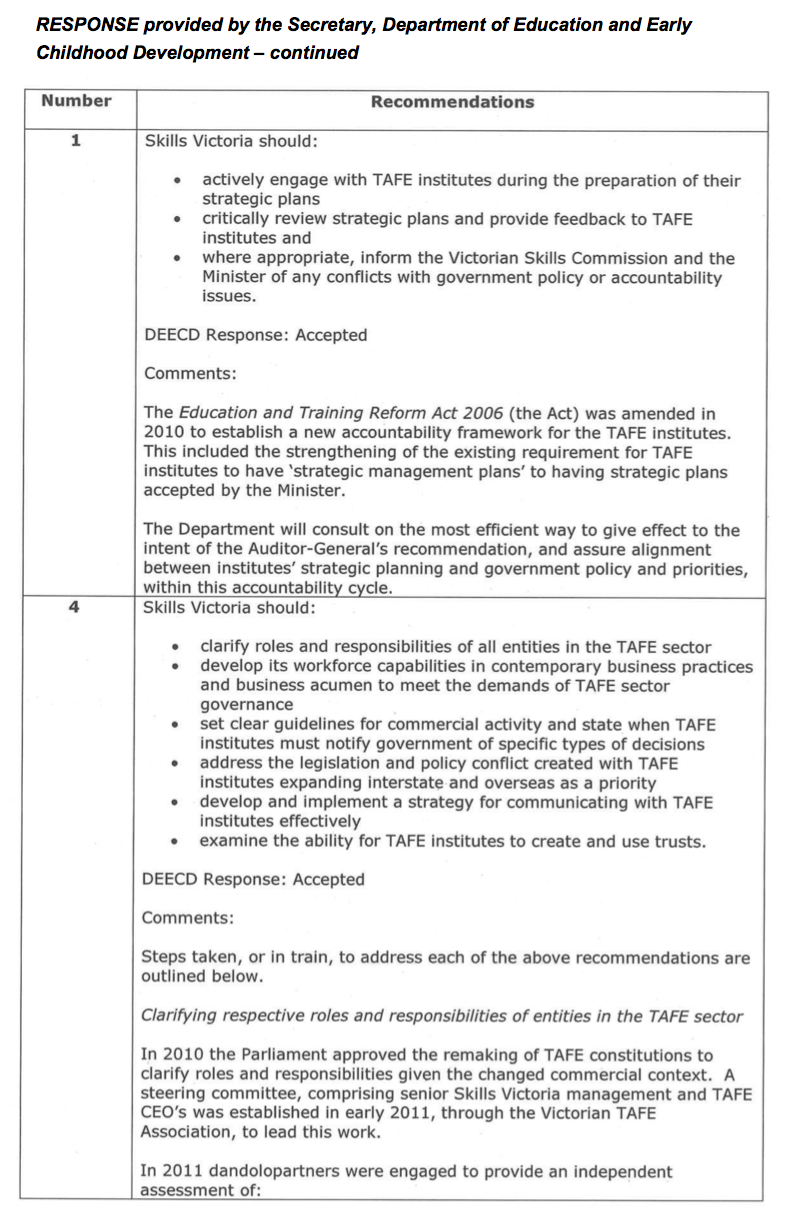

- Skills Victoria should:

- actively engage with TAFE institutes during the preparation of their strategic plans

- critically review strategic plans and provide feedback to TAFE institutes

- where appropriate, inform the Victorian Skills Commission and the Minister for Higher Education and Skillsof any conflicts with government policy or accountability issues.

Holmesglen should review its investment policy to ensure that investment decisions are consistent with its authority to invest, instructions from government and government policy, and that it embodies better practice prudential consideration.

The Department of Treasury and Finance should review the intended application of Standing Direction 4.5.6 and consider whether the exemption should be based on effective investment powers rather than the legal source of powers.

- Skills Victoria should:

- clarify the roles and responsibilities of all entities in the TAFE sector

- develop its workforce capabilities in contemporary business practices and business acumen to meet the demands of TAFE sector governance

- set clear guidelines for commercial activity and state when TAFE institutes must notify government of specific types of decisions

- address, as a priority, the legislation and policy conflict created by TAFE institutes expanding interstate and overseas

- develop and implement a strategy for communicating with TAFE institutes effectively

- examine the ability of TAFE institutes to create and use trusts.

The Victorian Skills Commission should develop and implement a mechanism to regularly test whether Skills Victoria is exercising its delegated functions effectively and efficiently.

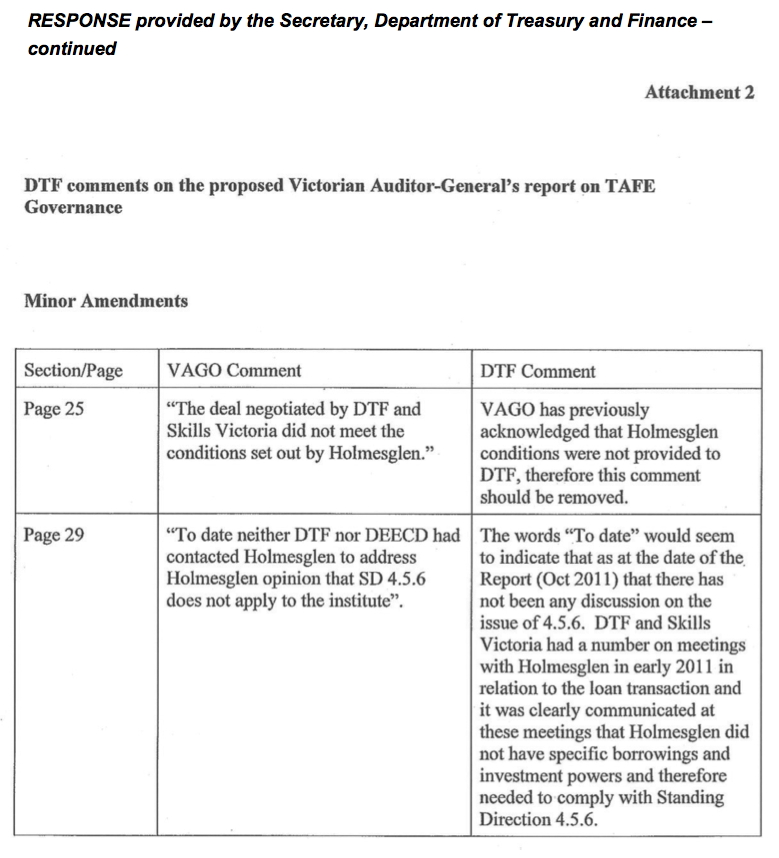

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, the Department of Treasury and Finance, the Holmesglen Institute of TAFE and the Victorian Skills Commission with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments, however, are included in Appendix B.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Technical and Further Education (TAFE) institutes provide the majority of reported vocational education and training (VET) in Victoria. VET is designed to equip students with specific workplace skills, including technical skills, through course design significantly influenced by industry.

There are over 1 300 providers registered to deliver VET in Victoria. They are a mix of TAFE institutes, universities, adult community education providers and private Registered Training Organisations (RTO). In 2008, 577 providers reported VET activity, including 14 TAFE institutes and 216 private RTOs.

In 2010 TAFE institutes in Victoria delivered approximately 126 million student contact hours. The total revenue for the TAFE sector was $1.585 billion, with $1.05 billion or about 66 per cent of this revenue coming from government sources.

VET is one component of Victoria's broader education sector and has links with both the school system and higher education.

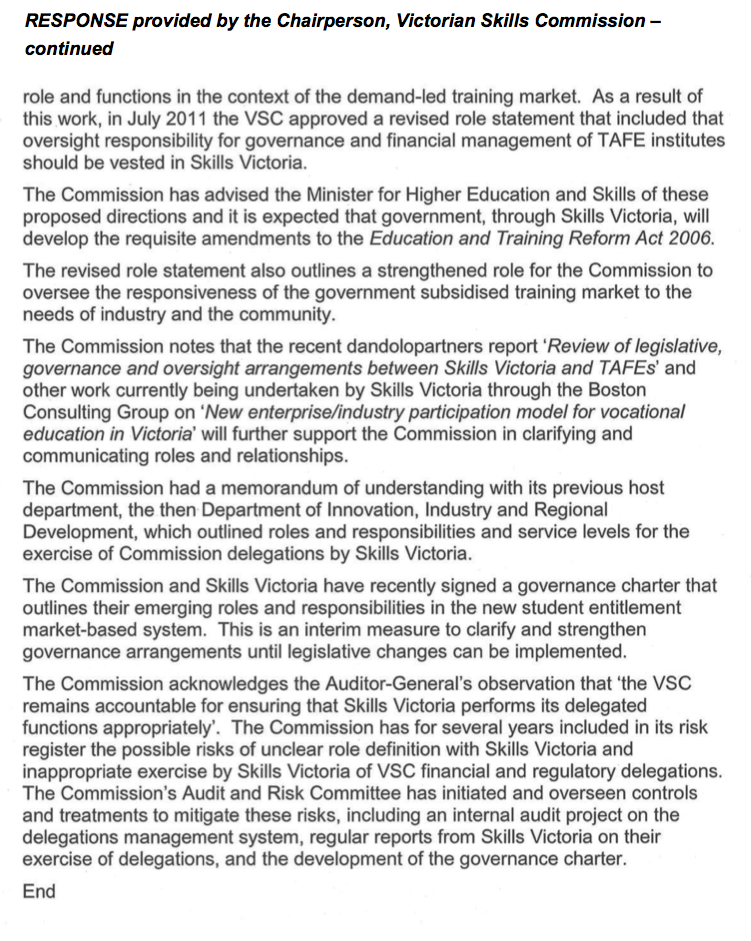

1.2 Roles and responsibilities

1.2.1 Victorian Skills Commission

The Victorian Skills Commission (VSC) is an industry-based body that oversees the Victorian training system. It provides policy advice and direction to the Minister for Higher Education and Skills on post-compulsory education and training.

The VSC has delegated many of its functions and powers to Skills Victoria, part of the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development.

1.2.2 Skills Victoria

Skills Victoria undertakes planning, policy making, regulation and resource allocation while also supporting TAFE institutes to meet government goals and targets. Skills Victoria also manages the government's relationship with TAFE institutes on a day‑to‑day basis.

1.2.3 TAFE institutes

TAFE institutes are responsible for providing education and skills training programs and services that meet the needs of industry, students and the general community. There is a high degree of flexibility in the delivery of programs including apprenticeships, traineeships, skills recognition, part time award courses and stand‑alone modules. Programs can be undertaken on campus, in workplace settings, in partnership with secondary schools, industry and universities, and through distance education arrangements including using online technologies.

Reporting structure

TAFE institutes are accountable to the Minister for Higher Education and Skills and report to Skills Victoria, although they may also report to other agencies, as reflected in Figure 1A.

Figure 1A

TAFE sector reporting lines

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.2.4 Registered Training Organisations

RTOs comprise public entities, such as TAFE institutes, and approximately 1 300 private training providers. RTOs include commercial training providers, training departments in manufacturing or service enterprises and secondary colleges providing VET programs in schools.

With the change in vocational education policy over the past decade, all RTOs, including TAFEs, compete for VET students, with the government paying students' fees for approved courses irrespective of the provider. Consistency is established through compulsory compliance with a set of national standards called the Australian Quality Training Framework. This is monitored by the Australian Skills Quality Authority.

1.3 Policy and legislation

1.3.1 Policy

In 2002 the government released Knowledge and Skills for the Innovation Economy, its policy for the future direction of the VET system, which sought to reshape planning, accountability and resourcing. TAFE institutes were encouraged to take an entrepreneurial approach to attract revenue in domestic and international markets. They were offered incentives to match government funding from their reserves to develop partnerships with business or industry. One third of TAFE funding came from sources other than state or Commonwealth payments.

In 2008 the Securing Jobs for Your Future policy moved TAFE institute funding from fixed allocations of state funding (input funding) to a model based on student enrolments (output funding). TAFE institutes now have to compete directly with RTOs to attract students and are paid in arrears after providing the training. They can also access block funding for some specific projects and initiatives.

1.3.2 Legislation

The Education Training and Reform Act 2006 (ETRA) outlines the functions, powers and accountabilities of the various agencies involved in the oversight and provision of TAFE services. These include VSC, TAFE institutes and the responsible minister.

ETRA outlines the role of VSC as an adviser to the minister on policy, statewide planning and the effective spending of money in the sector. ETRA is silent on the role of Skills Victoria.

ETRA sets out the role of the boards of TAFE institutes, which includes providing technical and further education programs and services to its population. ETRA also outlines board powers and accountabilities. Under ETRA, each TAFE board is responsible for overseeing and governing the institute efficiently and effectively and is accountable to the minister.

TAFE institutes are public bodies under the Financial Management Act 1994 and are required to comply with the Act and any general or specific direction given by the Minister for Finance. They are also subject to the Public Administration Act 2004, which provides a framework for governance in the public sector in Victoria.

1.4 The Holmesglen financial arrangement

In the course of the 2010 annual audit of the financial statements of the Holmesglen Institute of TAFE (Holmesglen) a financially material loan of $6.5 million to a private RTO in December 2010 was identified.

The loan was the first step in an acquisition strategy and would convert into equity in the RTO at the successful completion of due diligence. The loan was secured by a fixed and floating charge over the RTO's assets, an instrument similar to a mortgage, designed to protect the value of the initial loan.

Holmesglen's due diligence was completed in January 2011. The board did not progress with the original acquisition strategy leaving a fixed and floating charge over the RTO. Holmesglen ultimately removed the charge as part of negotiations with a new buyer of the RTO. The negotiations were finalised in early May 2011 and the agreement reached resulted in a $3 million impairment of Holmesglen's loan.

The events relevant to the arrangement are set out in full in Appendix A.

1.5 Audit objectives and scope

The objective of the audit was to examine:

- the legality, propriety and financial prudence of the financial arrangement in terms of the statutory powers and established operational remit of the Holmesglen Institute of TAFE and the TAFE sector

- the adequacy and effectiveness of oversight by the Holmesglen TAFE board of material investments by the institute

- the adequacy and effectiveness of coordination and oversight by Skills Victoria andthe Victorian Skills Commission of Holmesglen and the TAFE sector.

1.6 Method and cost

The audit was completed in accordance with Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. The cost of the audit was $335 000.

1.7 Report structure

The rest of this report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines the conduct of Holmesglen and the authority and financial prudence of the arrangement

- Part 3 deals with the oversight of the TAFE sector.

2 Holmesglen's financial arrangement

At a glance

Background

Over the past decade Technical and Further Education (TAFE) institutes have been encouraged to grow cash reserves by being entrepreneurial. In this context the Holmesglen Institute of TAFE (Holmesglen) entered into a financial arrangement with a private Registered Training Organisation (RTO). The investment raised critical issues about the legal framework and the exercise of financial prudence in the TAFE sector. The transaction ultimately resulted in a loss of $3 million of public funds.

Conclusion

By competing in an increasingly competitive market, TAFE institutes are at risk of acting outside the frameworks and standards necessary for public entities. In entering the financial transaction, Holmesglen acted outside its authority and without prudence.

Findings

- Holmesglen did not appropriately engage with its oversight bodies.

- Holmesglen acted beyond its legal authority as it did not comply with a direction made by the Minister for Finance in relation to investment risk, and did not comply with its own constitution which requires it to operate within public management policies established by the government.

- The exemption in Standing Direction 4.5.6 under the Financial Management Act 1994 is poorly designed which contributed to a poor understanding of its application.

- Holmesglen acted in good faith, but the $6.5 million loan it provided to the RTO as bridging finance was not prudent.

Recommendations

- Skills Victoria should critically review TAFE institutes’ strategic plans.

- Holmesglen should review its investment policy.

- The Department of Treasury and Finance should review the intended application of Standing Direction 4.5.6.

2.1 Introduction

On 17 November 2010 the board of the Holmesglen Institute of TAFE (Holmesglen) endorsed a strategy to acquire a substantial equity interest in a privately owned and run Registered Training Organisation (RTO).

The RTO was in financial distress and required access to immediate funds to remain solvent. Holmesglen approved a loan to the RTO of $6.5 million, with the intention that the loan amount would be converted to equity in the RTO following a due diligence process.

On 10 December 2010 a convertible loan agreement was executed, which allowed for the loan being converted into equity in the RTO and established a fixed and floating charge for the financial arrangement. A fixed and floating charge is a form of security similar to a mortgage. The charge sits as both a fixed charge over the non-trading assets of the company (land, buildings, machinery) and as a floating charge over trading assets (inventory, cash, accounts receivable). The floating component of the charge allows the company to operate normally, but ‘crystallises’, or freezes all assets, should the company default on the loan.

The $6.5 million was deposited into an escrow account and funds could only be drawn on for purposes specified in the agreement. In mid-December, the RTO began drawing money from the loan account.

The first $1.5 million of the loan amount was used to repay a loan, with interest, to a previous prospective purchaser. That prospective purchaser had lent money to sustain the RTO while undertaking its own due diligence assessment with a view to acquisition. The prospective purchaser chose not to proceed with the acquisition, and repayment of its loan was necessary to allow Holmesglen to secure priority for its fixed and floating charge.

During its 9 February 2011 meeting, the Holmesglen board was advised that its intended acquisition of the RTO had ‘failed the due diligence test’ and therefore Holmesglen was not proceeding to convert the loan to equity. At that meeting the board considered seeking 100 per cent equity in the RTO, but decided instead to withdraw from further negotiations, leaving in place the loan of $6.5 million, due for repayment with interest by December 2011.

Over the following weeks the previous prospective buyer for the RTO expressed renewed interest in acquiring the RTO and initiated discussions with Holmesglen to remove Holmesglen’s fixed and floating charge over the RTO.

Ultimately Holmesglen accepted a lump sum of $3.5 million on the fourth anniversary of the initial loan, and for the RTO to contract $1 million of Holmesglen’s consultancy services per year, for four years, as full repayment of the loan. This resulted in a loss of $3 million in the value of the loan, which was recognised in Holmesglen’s financial statements for the financial year ended 31 December 2010.

Details of the key events in this arrangement are provided in Appendix A.

2.2 Conclusion

By competing in an increasingly competitive market, TAFEs are at risk of acting outside the frameworks and standards necessary for public entities. The outcome of Holmesglen’s financial arrangement exemplified poor engagement between the TAFE institute and its oversight body. It also highlighted the misalignment between the new entrepreneurial expectations of TAFE institutes and the need for public accountability and transparency. When critical issues arose, Holmesglen did not adequately engage with Skills Victoria.

The financial arrangement entered into by Holmesglen was outside its legal authority and did not conform to the policy set out by government.

While there was no evidence that the board acted in bad faith, the financial arrangement by Holmesglen was not prudent and has led to a waste of $3 million of public resources. As the arrangement exhibited many of the features of a high-risk investment, prudent management required that the ‘capital’ value of the investment be protected. The security over the loan to the RTO, in the form of a fixed and floating charge, was never going to be effective in the event that the acquisition did not proceed and the value of the RTO decreased sharply. This was the eventual outcome and it should have been foreseen as a likely eventuality. A more prudent approach would have been to protect the capital value of the loan under all reasonably likely scenarios, and if this was not possible, not to proceed.

2.3 Engagement with Skills Victoria

This event followed a pattern of non-engagement between Holmesglen and its oversight bodies.

In June 2009, the Minister for Finance issued Standing Directions under the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA). Skills Victoria issued an executive memo to all TAFE institutes informing them of Standing Direction 4.5.6 (SD 4.5.6), which affected the investment activities of public entities. The Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) held information sessions for TAFE institutes about this Direction. Holmesglen did not formally seek to clarify the application of this Direction with DTF, which administers compliance with the Directions, or with Skills Victoria, which had issued the memo. Instead, it sought its own legal advice and concluded that it was not subject to the Direction. It did not share this advice with Skills Victoria. Holmesglen did not formally advise DTF that it believed SD 4.5.6 did not apply to it until September 2010. This demonstrated Holmesglen’s apparent attitude that it could act independently of government, and inconsistently with the government’s instructions. Holmesglen should have actively sought clarification about which rules applied to it.

Holmesglen met with Skills Victoria in October 2009 and asked whether a TAFE institute could acquire an RTO and access government funding. Skills Victoria agreed to seek further advice on this query. Despite that, Skills Victoria failed to provide further advice, and Holmesglen had not obtained clarity on this issue when, in late 2010, it moved to pursue the acquisition of the RTO.

Two days before the loan agreement was executed with the RTO, the board was advised that DTF had raised a concern about Holmesglen’s capacity to enter into the loan agreement, and that legal advice ‘will be sought’ by the chief executive officer. No legal advice was obtained before the agreement was executed. Without resolving this concern, Holmesglen could not have been certain of its legal authority to enter into the financial transaction. Holmesglen did not advise Skills Victoria of its decision to continue with the acquisition strategy or address concerns raised by Skills Victoria and DTF.

These cases of poor engagement are symptomatic of presumed autonomy, a lack of accountability and lack of effective oversight.

2.4 Authority to invest

TAFE institutes are public entities created under the Education and Training Reform Act 2006 (ETRA). ETRA confers on boards of TAFE institutes general powers to do ‘all things that are necessary or convenient’ in performing its legislated functions. There is no specific power to invest granted by ETRA, or any other source, although the general power granted would include a power to invest, subject to any limitations.

2.4.1 Limitations on investment powers

There are several sources of authority that limit the board’s authority to invest:

- ETRA is the primary authority for the governance of the board.

- All TAFE institutes, as public bodies, are subject to FMA and any applicable Standing Directions issued by the Minister for Finance under that Act.

- Holmesglen is subject its own constitution, issued as a Ministerial Order under ETRA.

The Education and Training Reform Act 2006

It is settled law that the powers of a statutory authority may only be used for its expressed functions, or functions that arise by implication or a reading of the whole Act. To this end, the powers of TAFE institutes can only be properly exercised for functions sufficiently connected to educating and training Victorians. This is a question of degree, and there was insufficient evidence to determine whether the intended acquisition of the RTO, which had substantial operations outside Victoria, would have met this condition.

Under ETRA, performance of the board’s functions and the exercise of its powers are also subject to the performance agreement between the board and the Victorian Skills Commission, and any economic and social objectives established by the Victorian Government. These ETRA requirements did not, in themselves, impair the authority of Holmesglen to enter into the transaction.

Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance

Standing Directions under FMA are instructions to public entities that must be followed.

From 1 July 2009, SD 4.5.6 instructed all departments and agencies subject to FMA to undertake their borrowings, investments and financial arrangements with state entities, or with other entities that have a credit rating the same or better than the state’s. The state has a AAA credit rating. This is a clear instruction to public entities to avoid ‘risky’ investments.

In entering into the convertible loan agreement with the RTO, Holmesglen did not follow this instruction.

Holmesglen considered that it was not required to follow SD 4.5.6 as it fell within one of the listed exemptions, and obtained legal advice supporting that view. Holmesglen did not engage with DTF about whether it was required to follow the Direction, or with Skills Victoria who had issued a memo to all TAFEs about the Direction.

SD 4.5.6 provides an exemption for any public entity that has been granted specific borrowing or investment powers under its constituting legislation, however, states that if the entity merely has general powers to do things necessary to perform its functions, the Direction applies. Notwithstanding that Holmesglen’s investment power is subject to the effect of its constitution, Ministerial Orders or other instruments, Holmesglen has not been granted specific borrowing or investment powers under ETRA, merely the general powers to do all things necessary to perform its functions. Therefore, the exemption cannot apply and Holmesglen should have followed the Direction.

The public policy is to ensure public entities only engage in low-risk activities. However this exemption in SD 4.5.6 is poorly designed, as it is based on the source of an entity’s investment power and has no regard for the state’s desired risk profile. As a result of its wording, two entities with different sources of investment power but the same effective investment abilities, in terms of scope or types of investments, are treated differently under SD 4.5.6. To argue that Holmesglen was exempt from the Direction because it had virtually the same investment ability as another body that had an explicit investment power ignores the words of the Direction. The exemption did not apply to Holmesglen.

The Standing Directions occur in a complex framework for public finance, accountability and resource management in Victoria. A recent attempt was made to streamline the legislative framework through the Public Finance and Accountability Legislation however this legislation was not passed. Improvements in the design of SD 4.5.6 are needed and may be achieved in isolation, or through a broader amendment to the legislative framework.

Holmesglen’s constitution

TAFE constitutions are issued as Ministerial Orders under ETRA, and therefore act as further instructions to boards.

Under its constitution, Holmesglen can only invest money in ‘investments authorised by the law related to trustees’. The Trustee Act 1958 allows a trustee to invest trust funds in any form of investment.

Holmesglen’s constitution requires the board to operate in accordance with public management policy established from time to time by the Victorian Government. In relation to investments, the government’s policy was stated in SD 4.5.6 as follows:

‘The objectives of this Direction are to ensure that treasury risks are effectively identified, assessed, monitored and managed by Public Sector Agencies, and that the strategies adopted by Public Sector Agencies are consistent with overall objectives of the government. The state has a conservative philosophy for the management of treasury risks and accordingly, Public Sector Agencies are encouraged to develop specific measures that best address the borrowing and investment risks of their business.’

This is a general statement of policy, and does not depend on whether SD 4.5.6 applies. It provides a clear signal to all public entities about the government’s risk appetite. The loan agreement with the RTO was outside this policy. Holmesglen, therefore, did not follow the instructions in its constitution.

The objectives of the constitution also state that the board will govern and control the TAFE institute efficiently and effectively, and optimise the efficient use of resources. Given the clear risk of the financial arrangement, and the ultimate impairment of the loan, Holmesglen has not been able to demonstrate that its acquisition strategy optimised the efficient use of public resources. It has, therefore, acted against the words and the intent of its instructions from government.

2.5 Propriety of the financial arrangement

Propriety is a subjective term. For the purpose of this audit, the propriety of the Holmesglen board in entering the financial arrangement was measured against whether their decision was:

- made with integrity, including whether the board acted honestly

- transparent and open to scrutiny

- based on board awareness of, and timely response to, its accountabilities.

Holmesglen had previously identified acquisitions as a key strategy and had signalled this to Skills Victoria. Holmesglen had also developed a good understanding of the RTO through previous dealings. While the information provided to the board was limited, the board considered this information and engaged in substantive deliberation about the strategic benefits of acquiring the RTO. The acquisition was consistent with Holmesglen’s strategic plan. There was no evidence that the board did not act in good faith and honestly.

The board deliberations and decision were clearly documented making its actions transparent.

Holmesglen did not adequately consider the implications of the financial arrangement on their accountabilities or respond appropriately when queries were raised. As noted above, Holmesglen was aware that Skills Victoria had concerns about the acquisition strategy but did not proactively address these concerns with Skills Victoria. Holmesglen did not consult Skills Victoria on the applicability of SD 4.5.6 and did not inform Skills Victoria of its decision to proceed with the financial arrangement. Because of this, Holmesglen fell short of the expectations of propriety for public entities. However, this was in the context of a lack of clarity about roles and responsibilities and Holmesglen’s established pattern of acting with a high level of autonomy which had not been sufficiently scrutinised. This is discussed in Part 3.

2.6 Financial prudence of the arrangement

In pursuit of the acquisition of the RTO, Holmesglen appropriately deferred a decision on the acquisition until due diligence was completed by external financial consultants. When the acquisition was shown to fail the due diligence process, Holmesglen appropriately decided not to proceed with the acquisition.

The audit found that the Holmesglen board gave consideration to the information that was provided to it. The acquisition of the RTO was consistent with Holmesglen’s strategic plan.

However, by setting up the convertible loan agreement prior to the due diligence, Holmesglen put a significant sum of public money at risk. Ultimately, the value of the loan was written down by $3 million.

The loan was drawn from cash reserves and was small in comparison to the size of Holmesglen’s business as measured by its net assets of over $320 million, and income of over $170 million in 2010. The full loss of the loan was not going to threaten Holmesglen’s ongoing operations or viability.

Nevertheless, these were public funds, and the board was subject to several sources of accountability for those funds.

2.6.1 Accountability for use of public funds

When using public resources the board are required to:

- be accountable to the minister for the effective and efficient governance of the TAFE institute under ETRA

- optimise the use of resources and operate in accordance with the public management policy of the government, as required under Holmesglen’s constitution

- comply with the Victorian Government Risk Management Framework

- act in a financially responsible manner and exercise due care, diligence and skill, as required by the government’s director’s code of conduct issued by the State Services Authority.

None of these sources give a definitive explanation of what steps are necessary to meet these duties. Nevertheless, the sheer number of sources of responsibilities should have caused any public officer to be cautious about entering into a financial transaction and to be able to demonstrate that it represented value‑for‑money for the community. The transaction needs not only to be considered prudently, but decision‑makers also need to be able to demonstrate that prudence was applied.

There is no definitive prescription of what is prudent in all cases, and the particular circumstances of any investment need to be taken into account in making such judgements.

Decision to enter into the loan agreement

Holmesglen recognised that the loan was high risk. The clearest signal of this was that the initial loan to the RTO was provided because it was in financial distress and it needed the funds immediately to pay its creditors and meet operating costs through to the end of January 2011.

In this scenario, the prudent course of action was to seek to secure the value of the loan, so that if the intended acquisition of the RTO did not proceed, the capital value of the loan was protected. Holmesglen tried to do this through a fixed and floating charge over the assets of the RTO.

At the time of implementing the charge, Holmesglen was advised that the net tangible assets of the RTO were around $16.8 million. This represented the minimum value of the physical and financial assets of the business as a going concern; or, in the event of their disposal, the likely proceeds from an orderly sale process.

In the event that the acquisition did not go ahead, and there were no other buyers, it was highly likely that the RTO would remain in financial distress and be unable to repay the loan by December 2011. In the financial statements of the RTO presented to Holmesglen in November 2010, the RTO had net current liabilities of $24 million and annual cash flows of less than this. The interest rate agreed, the official cash rate plus 2 per cent, did not adequately reflect the risk of the loan.

In the event of business failure the value of the net tangible assets of any entity are likely to be significantly lower, particularly if a ‘fire sale’ ensues. The tangible assets of the RTO comprised leasehold fit-out and lease deposit bonds. In the event of business failure the deposit bonds would likely be forfeited, with the possibility of a further contractual liability arising for unpaid rent, albeit unsecured. The leasehold fit-out would also be practically worthless, and a further unsecured liability may have been triggered for restoration of the leased premises.

While the charge was established to protect the value of the loan in the eventuality that the acquisition did not proceed, it was in just these circumstances that it was ineffective. Given the nature of the tangible assets of the RTO, the charge was only going to be effective if there were a number of potential buyers for the business. This was not the case. Consequently, in the absence of competitive tension, Holmesglen, and subsequently DTF, had little effective leverage in their negotiations with the eventual buyer of the business, to recover the full value of the loan.

Consistency with internal policies

Holmesglen has an investment policy and a strategic plan. While these are not strictly binding on the board, its investment decisions should have been in line with its own policies.

Holmesglen’s investment policy was approved in June 1997. The discussion of risk within this policy was minimal. It discussed acquisition risk only indirectly in the aim: ‘to minimise investment risk by holding a diversified portfolio of equities’. As such, there was nothing in the policy to adequately guide the consideration of the loan agreement. This absence of clearly articulated risk principles for considering the financial prudence of its investments meant that the board had no pre‑defined reference or benchmark against which to calibrate the financial risk of the acquisition of the RTO, or to otherwise assess its financial merits.

The policy was reviewed in 2004 with the intent that it be updated. The draft policy contained investment principles that included ‘to optimise returns while maintaining an acceptable level of risk’. The draft policy was never adopted.

Strategic plans are required under ETRA. Holmesglen’s strategic plan provides a high‑level mission statement and vision for the TAFE institute, which focuses on delivery of education and training, being a leader in international education, and supporting business development strategies that are ‘innovative, responsive and entrepreneurial’. The current plan, which covers the period 2007–12, includes strategies to expand the institute’s financial base, maximise new business opportunities, develop appropriate revenue generators, and invest in opportunities or acquisitions to foster growth and innovation.

The intended acquisition of the RTO is clearly consistent with Holmesglen’s articulated strategies. Indeed, the strategic plan encourages the pursuit of similar acquisitions.

While not in place at the time the loan agreement was made, new amendments to ETRA now require TAFE institutes to ensure that their operations are in accordance with their strategic plans. This raises serious issues in cases where the strategies in such plans are not aligned with established public sector accountabilities and controls.

Recommendations

- Skills

Victoria should:

- actively engage with TAFE institutes during the preparation of their strategic plans

- critically review strategic plans and provide feedback to TAFE institutes

- where appropriate, inform the Victorian Skills Commission and the Minister for Higher Education and Skills of any conflicts with government policy or accountability issues.

- Holmesglen should review its investment policy to ensure that investment decisions are consistent with its authority to invest, instructions from government and government policy, and that it embodies better practice prudential consideration.

- The Department of Treasury and Finance should review the intended application of Standing Direction 4.5.6 and consider whether the exemption should be based on effective investment powers rather than the legal source of powers.

3 TAFE sector oversight

At a glance

Background

The vocational education and training (VET) sector has changed substantially over time with the most fundamental reform being the transition to the fully contestable VET market over the past decade.

Conclusion

Skills Victoria has not provided effective leadership or oversight of the Technical and Further Education (TAFE) sector. During the transition to the contestable market, Skills Victoria has not adequately considered the implications of this policy change, including the legal consequences of TAFE institutes operating outside of Victoria. Skills Victoria created a conflict between policy, legal authority and standards of public sector accountability. Skills Victoria cannot be confident it has sufficient knowledge of TAFE institutes’ activities for effective oversight.

Findings

- The Holmesglen Institute of TAFE (Holmesglen) financial transaction indicates that TAFE institutes and their oversight agencies do not have clarity about their respective roles and responsibilities.

- Skills Victoria has little guidance for TAFE institutes on significant sector issues such as acceptable commercial activities.

- Skills Victoria has significant gaps in its understanding of Holmesglen’s strategies and activities, and failed to adequately respond to information it did have.

- Skills Victoria’s communication with Holmesglen has been ineffective.

Recommendations

Skills Victoria should:

- clarify roles and responsibilities of entities in the TAFE sector

- develop its workforce capabilities

- set clear guidelines for commercial activity

- address the legislative and policy conflict created by TAFE institutes expanding interstate and overseas

- develop and implement a communications strategy

- examine the ability of TAFE institutes to create and use trusts.

The Victorian Skills Commission should develop and implement mechanisms to test whether Skills Victoria is exercising its delegated functions effectively and efficiently.

3.1 Introduction

The Victorian Skills Commission (VSC) has an oversight role for the Victorian training system. The VSC is supported, through delegation, by Skills Victoria who undertake planning, policy making, regulation and resource allocation for the Technical and Further Education (TAFE) sector. Skills Victoria is the primary oversight body for the activities of individual TAFE institutes.

As TAFE institutes are public entities, the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) also has an oversight role in relation to the compliance of TAFE institutes with the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA).

Effective oversight of the TAFE sector requires sound relationship management, characterised by predictability and transparent communication, with individual TAFE institutes.

It also requires leadership. Effective leadership includes setting strategic policy direction, communicating this direction to the sector, developing operational policies for the successful implementation of strategic policy, as well as identifying emerging issues and taking action when required.

3.2 Conclusion

The VSC and Skills Victoria have not provided effective leadership or oversight of the TAFE sector. This is highlighted by the events leading up to and immediately following the Holmesglen financial transaction. In a number of key areas, Skills Victoria has not provided clear guidance or identified and resolved emerging TAFE sector issues in a timely manner.

During the 10-year transition to the contestable market, Skills Victoria has not fully considered the implications of this policy change, including the legal consequences of TAFE institutes operating outside of Victoria. Skills Victoria created a conflict between policy and legal authority, which may mean TAFE institutes are operating outside their powers where they have significant operations interstate and overseas. Skills Victoria cannot be confident that it has sufficient knowledge of other TAFE institutes’ activities or whether they are meeting the dual goals of commercial success and accountability for the use of public money.

While having a number of communication arrangements in place, these have not been effective. Skills Victoria had significant gaps in its understanding of the Holmesglen Institute of TAFE’s (Holmesglen) strategies and activities, and failed to adequately respond to information it did have.

The circumstances of the Holmesglen financial arrangement are a strong indication that Skills Victoria has not adequately changed the way it interacts with and oversees the TAFE sector, despite institutes now being expected to operate quite differently to 10 years ago. The new contestable model calls for new skills and competencies to guide and govern TAFE institutes which are required to operate as innovative and highly commercial bodies. These were not evident in Skills Victoria’s engagement with Holmesglen.

3.3 Roles and responsibilities

3.3.1 Oversight bodies

The Holmesglen financial transaction provides evidence that TAFE institutes and their oversight agencies do not have clarity about their respective roles and responsibilities.

Victorian Skills Commission

The VSC was established in July 2007 by the Education and Training Reform Act 2006 (ETRA). It provides advice to government on post-compulsory education and training, provides funding for training and further education, regulates the apprenticeship and traineeship system, and supports the Local Learning and Employment Networks.

The VSC does not play a day-to-day role in TAFE sector governance. Its main activity is advising the Minister for Higher Education and Skills on the whole of the vocational education and training (VET) sector, although it does still regulate apprenticeships and traineeships. VSC has delegated many of its functions relating to TAFE institutes to Skills Victoria, part of the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development.

Skills Victoria

Skills Victoria has no formal responsibilities, however it performs certain functions delegated to it by VSC and generally supports the minister in developing and implementing policies relevant to the VET sector. According to its website, it supports and facilitates access to training and tertiary education opportunities so that Victorians can acquire skills that are utilised by, and contribute to the success of, Victorian businesses.

Department of Treasury and Finance

DTF is responsible for the oversight of compliance to the FMA, and has a central agency interest in effective management of public resources across the public sector.

3.3.2 Lack of clarity

Skills Victoria has not clarified its roles or responsibilities for TAFE sector governance with the increase in autonomy of TAFE institute boards in the contestable environment. It has not established the nature or significance of events which should ‘trigger’ its examination of TAFE institute board governance processes, observation of board decisions or intervention in board decision-making.

The Review of Skills Victoria by the State Services Authority in 2009 also identified confusion over the role of Skills Victoria and other VET sector bodies. The review consequently recommended that roles be clarified for there to be effective governance of the TAFE sector. This has not occurred and confusion over responsibilities has been a factor in the Holmesglen financial arrangement and its consequences.

DTF has stated that Skills Victoria, as the portfolio agency, has primary responsibility for identifying TAFE institute non-compliance with directions under the FMA. Public entities declare their compliance with the legal requirements set out in the FMA via the self-assessment tool, the Financial Management Compliance Framework (FMCF). Compliance with Standing Direction 4.5.6 (SD 4.5.6) was included in the FMCF checklist in 2009–10.

Skills Victoria was part of the Department of Innovation, Industry and Regional Development (DIIRD), now the Department of Business and Innovation, when in September 2010, Holmesglen first reported that SD 4.5.6 did not apply to the institute.

When TAFE institutes certify their compliance with the FMCF, the information is visible to both DTF and the central finance team in the portfolio department. DTF have stated that they identify issues of clear non-compliance with Standing Directions and notify the portfolio department where it is felt that closer attention is warranted. DTF did not identify this as a clear issue of non‑compliance and did not alert DIIRD’s central finance team to Holmesglen’s lack of compliance. Neither did the central finance teams of DIIRD, and subsequently DEECD, alert Skills Victoria as the oversight body for the TAFE sector.

During the latter stages of finalising the loan, DTF negotiated directly with the Registered Training Organisation’s (RTO) buyer on behalf of Holmesglen. The parties involved in the Holmesglen transaction did not have a common understanding of DTF’s role or responsibility.

Skills Victoria and DTF had no documented authority from the Holmesglen board to negotiate with the RTO’s agent on Holmesglen’s behalf. Skills Victoria and DTF state that all parties had verbally agreed that DTF should take on the primary negotiation role. Holmesglen disputes this. This role confusion contributed to the poor outcome of recovering Holmesglen’s loan.

Under ETRA, TAFE institute boards are required to account for the performance of the institute in carrying out its functions and exercising its powers, to the minister. The authority for TAFE institutes to make independent commercial decisions without the involvement of the minister or Skills Victoria is ambiguous. This is a serious shortcoming, which Skills Victoria should address as a matter of urgency.

Skills Victoria has commenced a process to provide greater clarity of roles and responsibilities, including an internal restructure, which will start to address some of these issues.

3.4 Leadership and oversight

Skills Victoria and its predecessors have been responsible for the future of VET since the establishment of the State Training Board in 1987.

In a 2009 review, the State Services Authority stressed the importance of Skills Victoria’s workforce capabilities for a successful transition into the new environment. Skills Victoria has a heavy reliance on external consultants. It failed to respond to legitimate queries, and does not document key agreements and decisions. This combined with its poor communication during the Holmesglen financial arrangement, suggests that it has not developed the appropriate skillset required to meet its leadership responsibilities to govern the TAFE sector effectively in the new VET environment.

3.4.1 Policy inconsistencies

Skills Victoria has developed high level strategic policies for the fully contestable VET market over the past 10 years. However it has failed to identify that the Knowledge and Skills for the Innovation Economy policy, and subsequent VET policies encouraging TAFE expansion interstate and overseas, do not align with TAFE institutes’ legislated function to provide educational services for Victorians.

Skills Victoria only became aware of this fundamental inconsistency when it obtained advice from the Victorian Government Solicitor’s Office in January 2011. Based on this advice, many activities of TAFE institutes may be outside their legal authority if they are not sufficiently connected to providing education and training in Victoria. This conflict between policy and legislative authority needs to be addressed as a priority.

Many of the implications for TAFE institutes in the increasingly contestable environment have not been adequately considered and there remain significant gaps in the policies guiding the TAFE sector. Skills Victoria has not developed comprehensive lower level operational policies.

In particular there are no policies or guidelines clarifying:

- how TAFE institutes should operate in a contestable environment and be entrepreneurial while using public funds permissibly

- the extent of TAFE board autonomy, including whether, and under what circumstances, ministerial approval for a decision is required

- the timing and extent of disclosure of commercial activities to Skills Victoria, including those activities by associated trusts and related parties

- the definitions of investments, acquisitions and financial arrangements, to enable boards to comply with legislation, including whether loans are considered as investments

- the authority and power of government agencies to intervene if they disagree with a board decision.

This lack of guidance risks the successful transition of TAFE institutes into the new environment. This risk may be particularly pronounced for smaller TAFE institutes who, unlike Holmesglen, have smaller asset bases, less experience and fewer skilled human resources to draw on.

In response to Holmesglen’s financial arrangement and acquisition strategy, in March 2011 the Minister for Higher Education and Skills imposed a 12-month moratorium on TAFE institutes acquiring private RTOs without ministerial approval, via a Ministerial Direction. Figure 3A details Skills Victoria’s subsequent communication of its reasons for extending the conditions set out in the Ministerial Direction indefinitely, as government policy.

Figure

3A

Skills Victoria's rationale for preventing TAFE institutes from acquiring

private providers to run as separate, private entities

In August 2011 Skills Victoria outlined the following rationale as to why TAFE institutes should not be permitted to acquire private RTOs:

- The fulfilment of a TAFE institute’s broader service capabilities could be compromised.

- A TAFE institute could have a competitive advantage because it would indirectly enjoy the benefits of public ownership without having to comply with the obligations associated with public ownership.

- The community may perceive that public funds provided to TAFE institutes to enable them to deliver a range of objectives, including economic and social objectives of the government and to fulfil obligations to their communities, are being used to facilitate the operations of the private provider.

- The acquisition may set a precedent that government is willing to use public funding to save failing private providers.

- TAFE institutes may be exposed to unacceptable levels of financial liability.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office, based on Skills Victoria’s Policy Paper TAFE Institute Acquisition of Private Education Providers, August 2010.

Some of this reasoning is inconsistent with the central direction of the contestable VET market policy, which sees both public and private training entities as legitimate providers, with each competing for market share by endeavouring to deliver the best VET services for students.

Given that government has moved to a contestable model based on funding for education delivery, regardless of provider, the above policy position should be further developed to align with the TAFE institutes operating in a contestable environment.

An emerging problem is likely to be TAFE institutes’ strategic plans which set out the medium-term visions and objectives and identify and articulate strategies for achieving these.

Holmesglen’s current strategic plan, which covers the period 2007–12, envisions the institute to be a leader in international education, and supports business development strategies that are innovative, responsive and entrepreneurial. The plan includes strategies to expand its financial base, maximise new business opportunities, develop appropriate revenue generators, and invest in opportunities or acquisitions to foster growth and innovation.

These strategies are consistent with the contestable VET market model, but do not necessarily reflect the allowable functions of TAFE institutes as set out in ETRA, nor do they meet the standards of responsible use of public resources. Nevertheless, ETRA now requires TAFE boards to ensure the institute operates in accordance with its strategic plan. While the primary responsibility rests with TAFE institute boards, the role of Skills Victoria should include active engagement and critical review to provide systemic assurance that TAFE boards are operating within legislative and policy parameters.

3.4.2 Communicating the policy direction

Skills Victoria uses multiple methods to communicate information of differing levels of importance and urgency to the whole TAFE sector, including executive memos, presentations and messages posted on the TAFE institute computer training system.

Skills Victoria has publicised the strategic VET policies well, including communicating high level policy intentions to the sector. The Holmesglen case study however, shows that Skills Victoria has not yet developed comprehensive lower level working policies, and has therefore not been able to fully communicate the underlying implications of the changing VET environment to the TAFE sector.

3.4.3 Taking action when required

There are several examples of where Skills Victoria has not identified or resolved emerging issues signalled by the strategies and activities Holmesglen was undertaking in the contestable environment.

In 2007 a third party informed Skills Victoria about Holmesglen’s failed bid to acquire a central business district building. Skills Victoria states it voiced its concerns to Holmesglen about the size of the venture when it found out about the bid. It also had concerns about Holmesglen’s lack of disclosure of such a significant commercial decision, but did not communicate this concern in any way to Holmesglen or take action to address this issue.

During 2009, there were multiple signals to Skills Victoria that Holmesglen was considering RTO acquisitions. Holmesglen asked Skills Victoria if such acquisitions were allowable. Skills Victoria undertook to provide further advice on this, but failed to do so. Holmesglen’s intentions signalled how the new contestable policy would be tested, and the requirement for a policy position to be developed and communicated to the TAFE sector.

Skills Victoria should have identified that clear policy guidance was needed for the whole sector. It should have clarified its policy on the limits of property acquisition and developed communication protocols, including guidance on when TAFE institutes must notify Skills Victoria about a specific commercial decision. This guidance is yet to be developed.

Response to reviews about TAFE sector governance

Skills Victoria has not acted to resolve significant matters identified by the two reviews of TAFE governance it commissioned in the past decade.

The first review, completed in 2003, recommended actions that have yet to be fully implemented by Skills Victoria. These include:

- reviewing and documenting respective entities’ roles and responsibilities in the strategic planning process

- documenting protocols between the now TAFE institute boards, Skills Victoria and VSC in corporate governance charters

- reviewing TAFE institute reporting arrangements with a focus on underlying risk

- establishing continuous disclosure protocols between the now TAFE institute boards, Skills Victoria and the minister.

These actions are directly relevant to the events surrounding Holmesglen’s financial arrangement and, had they been implemented, may have produced a different outcome.

The second of the TAFE governance reviews, which commenced in 2007, was prompted by Holmesglen’s failed central business district bid. The report was finalised in 2009 and some recommendations have been implemented, including the development of a strategic dialogue process between individual TAFE institutes and Skills Victoria. Other recommendations are yet to be actioned.

Recommendations from both reviews sought to address issues with communication, and to clarify roles and responsibilities. These issues have persisted and remain current.

3.4.4 Use of trusts

During the course of the audit it was discovered that part of the original intention for the acquisition of the RTO involved the trustee of the Holmesglen Investment Trust (the Trust). The Trust was established to mortgage and obtain finance on properties owned by Holmesglen. In a discussion paper written by the chief executive officer of Holmesglen it was noted that the Trust and the trustee arrangement was important to Holmesglen as it can ‘purchase property and enter into loan agreements more easily than Holmesglen and can undertake projects that may be more speculative or commercial in nature than Holmesglen’.

The Holmesglen board has the power to appoint and remove the trustee. The trustee is a private company set up by three Holmesglen board members, initially appointed as directors of the Trust. One of these people remains as a current Holmesglen board member.

In 2010 Holmesglen loaned $16.8 million to the trustee to purchase property. As the financial arrangement with the RTO has shown, it is outside the authority of Holmesglen to loan money to a private company without a AAA credit rating and therefore this loan is subject to the same concerns raised in the audit. While outside the scope of this audit, this raises a number of questions that warrant further consideration by Skills Victoria.

3.5 Engagement with TAFE institutes

Skills Victoria failed to effectively engage with Holmesglen prior to and during the financial transaction.

The relationship between Skills Victoria and Holmesglen is poor, characterised by limited communication and mutual distrust. A lack of documented policies and communication protocols has contributed to unpredictable behaviour and the perception of disingenuous communication by both parties.

3.5.1 Reporting effectiveness

TAFE institutes provide Skills Victoria with their annual reports, quarterly financial statements, and annual statements of corporate intent.

The processes Skills Victoria has in place for TAFE institutes to report their commercial strategies and activities are not effective. Skills Victoria uses policy provisions to require TAFE institutes to provide it with the information it needs to effectively oversee the TAFE sector. However, it did not successfully analyse the information it received to identify that Holmesglen’s growth strategies were developing in areas where there was a policy vacuum.

Strategic dialogue process

In 2009, following the review of TAFE governance commissioned by Skills Victoria, it instigated annual meetings with individual TAFE institutes for those bodies to disclose how they were planning to grow within the contestable VET market. This is the strategic dialogue process and includes:

- Skills Victoria sending a letter of government expectations to TAFE institutes in October each year

- TAFE institutes responding to the points made in the letter with a Statement of Corporate Intent in November each year

- Skills Victoria and individual TAFE institutes meeting to discuss the Statement of Corporate Intent in November each year.

Skills Victoria aims to identify discrepancies between TAFE institutes’ strategies and government intentions through this process.

The strategic dialogue process has the potential to improve TAFE sector governance, provided information is shared and there is a common understanding of policies, strategies and activities. The strategic dialogue process between Holmesglen and Skills Victoria failed because there has not been the necessary common understanding of Holmesglen’s commercial intentions. Skills Victoria did not actively seek to understand those intentions.

3.6 Skills Victoria’s communication with Holmesglen

In addition to not having documented communication procedures for interactions with individual TAFE institutes, Skills Victoria’s contact with Holmesglen has typically been undocumented. Important information about policy intentions and issues about sector governance has been given verbally to Holmesglen. This is poor practice, especially for matters of significance.

It is the responsibility of Skills Victoria, as the oversight body, to set both the rules and tone of communication in its relationships with the TAFE sector. When Holmesglen established a pattern of no or minimal communication with Skills Victoria, including for some significant commercial decisions, Skills Victoria did not raise its concerns with Holmesglen. Skills Victoria has also not been clear about its expectations of Holmesglen for a number of years leading up to, and during, the financial arrangement, as illustrated in Figure 3B.

Figure

3B

Skills Victoria’s role during the Holmesglen financial

arrangement with the RTO

The financial arrangement between Holmesglen and the RTO highlighted Skills Victoria’s ineffective engagement with TAFE institutes.

In its 2009 and 2010 Statements of Corporate Intent, Holmesglen referred multiple times to an ‘acquisitions plan’ and its intention to seek ‘innovative and entrepreneurial’ business development opportunities. Skills Victoria sought no further information or clarification.

In October 2009, Holmesglen’s Statement of Corporate Intent was provided to Skills Victoria, signalling an intention to acquire RTOs and make other investments. Holmesglen asked Skills Victoria whether a TAFE institute could acquire an RTO and access government funding. Skills Victoria agreed to seek advice on this query. Skills Victoria neither followed up on the query nor sought further information on Holmesglen’s intentions.

Holmesglen submitted its FMCF compliance certification data in September 2010, answering the question about compliance with Standing Direction 4.5.6 with ‘N/A’. Neither Skills Victoria, nor DTF, contacted Holmesglen to challenge its opinion that the Direction did not apply to the institute.

In November 2010, following a meeting between Holmesglen, Skills Victoria and DTF, about the RTO acquisition strategy, Skills Victoria received an email from DTF raising concerns about the authority to make the acquisition. The email was forwarded to Holmesglen in abridged form only, which did not convey clearly the importance of the concerns being raised. Skills Victoria did not follow up with Holmesglen to determine if a decision had been made and if the concerns had been addressed. Skills Victoria found out about the acquisition through a third party after the loan agreement had been executed.

In January 2011, Skills Victoria sought legal advice about Holmesglen’s authority to pursue the acquisition, but it did not convey the information it received to Holmesglen.

In February 2011, Skills Victoria was taking independent action to deal with the RTO. It advised a potential new buyer that the government was not considering voluntary administration for the RTO without informing Holmesglen.

In April 2011, Skills Victoria requested DTF complete negotiations, on behalf of Holmesglen, to remove the fixed and floating charge over the RTO’s assets without documented agreement from the Holmesglen board.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

During the finalisation of the financial transaction, Skills Victoria, as the intermediary between Holmesglen and DTF, did not communicate transparently, which resulted in a situation where Holmesglen’s and DTF’s objectives were divergent. Neither party was aware of the other’s objectives. Holmesglen’s favoured option was to acquire equity in the RTO, yet one of DTF’s objectives was that Holmesglen should not acquire equity. These different agenda meant that inconsistent aims presented to the RTO’s buyer likely weakened Holmesglen’s negotiating position.

3.7 The Victorian Skills Commission

VSC has delegated key functions to Skills Victoria. This included making performance agreements with the boards of TAFE institutes with respect to the provision of vocational education and training or adult, community and further education. This also included making payments to the boards of TAFE institutes in accordance with performance agreements. TAFE boards are required to comply with performance agreements under ETRA.

While some of its functions may be delegated, VSC is accountable to the minister and must perform its functions, and exercise its powers, in line with any economic and social objectives, and public sector management policy, established by the government.

Delegation does not remove accountability. VSC remains accountable for ensuring that Skills Victoria performs its delegated functions appropriately.

VSC received regular reports from Skills Victoria about the performance of the TAFE sector, but received no reports on the performance of the delegated functions. VSC had no processes in place to gain any assurance that Skills Victoria was exercising these functions effectively or efficiently.

The current review of oversight arrangements being undertaken by Skills Victoria contains recommendations to clarify the role of VSC, including a recommendation to amend ETRA to remove VSC’s role in TAFE governance matters. These recommendations are being considered by government.

Recommendations

- Skills Victoria should:

- clarify the roles and responsibilities of all entities in the TAFE sector

- develop its workforce capabilities in contemporary business practices and business acumen to meet the demands of TAFE sector governance

- set clear guidelines for commercial activity and state when TAFE institutes must notify government of specific types of decisions

- address, as a priority, the legislation and policy conflict created by TAFE institutes expanding interstate and overseas

- develop and implement a strategy for communicating with TAFE institutes effectively

- examine the ability of TAFE institutes to create and use trusts.

- The Victorian Skills Commission should develop and implement a mechanism to regularly test whether Skills Victoria is exercising its delegated functions effectively and efficiently.

Appendix A. Events relevant to the financial arrangement