Tertiary and Further Education Institutes: Results of the 2013 Audits

Overview

This report covers the results of the 2013 financial audits of 27 entities, comprising 14 technical and further education (TAFE) institutes and the 13 entities they control.

Clear audit opinions were issued on the financial reports of all entities. An emphasis of matter paragraph was included in the financial report of Northern Melbourne Institute of TAFE, drawing attention to a material uncertainty in its ability to continue as a going concern.

Clear audit opinions were issued on all 19 performance reports for 2013. However, the TAFE sector did not have a framework that mandated relevant and appropriate key performance indicators, nor was it provided with sufficient guidance in establishing suitable targets and analysing performance. Accordingly, the sector's performance reporting was underdeveloped and inconsistent, lacked clear direction and did not facilitate comparability across the sector. From 2014, TAFEs are to implement a strategic planning framework requiring them to set key performance indicators clearly linked to their key strategies. While an improvement, the framework does not establish a core suite of indicators against which TAFEs are to report. Without the ability to compare performance across the sector and between entities, the value of performance reporting is diminished.

The 14 TAFEs generated a net deficit of $16.2 million, a decrease of $74.8 million from 2012. These results suggest that many TAFEs have yet to respond effectively to changes to the funding model and contestability arrangements. The changes were designed to improve the sector's financial sustainability and have increased TAFEs' reliance on student fee revenue in a contestable environment. While a majority of TAFEs reduced their expenditure during the year, the cost reductions and increases in student fee revenue were not sufficient to offset the reduction in funds from government of $116.3 million.

Consequently there has been a significant decline in the financial sustainability of the sector. We assessed the financial sustainability of five of the TAFEs as being high risk in 2013. This means that there are immediate or short term financial challenges at these TAFEs that need to be addressed.

Northern Melbourne Institute of Technology (NMIT) reported a net operating deficit of $31.7 million, and in the absence of any remedial action projected substantial cash-flow deficits for the next two years. As a result, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development has agreed to support NMIT in securing a two-year interest-free government bridging loan of $16 million to assist with proposed restructuring arrangements. Following changes to the board and executive team, NMIT has identified and commenced the implementation of various operational initiatives to improve its cash flows for 2014. NMIT has been flagged as an overall high financial sustainability risk in this report.

Against the trend, Chisholm, Goulburn Ovens, Kangan and Sunraysia TAFEs reported improved financial results. Some of the effective initiatives at these TAFES have included implementing service provision through third parties (Goulburn Ovens and Sunraysia), changed course offerings, staff redundancies and reduced operating costs. Early adoption of these initiatives has made these TAFEs more financially viable, and they are to be commended.

Tertiary and Further Education Institutes: Results of the 2013 Audits: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER August 2014

PP No 334, Session 2010–14

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Technical and Further Education Institutes: Results of the 2013 Audits.

This report summarises the financial reports of 14 technical and further education (TAFE) institutes and the 13 entities that they control at 31 December 2013.

It informs Parliament about significant issues identified during our audits and complements the assurance provided through individual audit opinions included in the entities' annual reports.

The report highlights that many TAFEs have not effectively adapted to the changed operating environment, and consequently the financial sustainability of the sector has declined.

The report also comments on performance reporting by TAFEs, and notes that the lack of appropriate direction by the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development has resulted in inconsistent presentation of performance information that is not easily comparable across the sector. While a new strategic planning framework being introduced in 2014 provides a number of improvements, further work is required to establish a robust and high quality performance reporting framework.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

6 August 2014

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Tim Loughnan—Sector Director Michael Almond—Team Leader Matthew Graver—Audit Senior Ryan Ackland and Alex Mulholland—Analysts Ellen Holland and Simone Bohan—Engagement Quality Control Reviewers |

Victoria's technical and further education (TAFE) institutes deliver post-secondary vocational educational services to both domestic and international students. There have been substantial changes to the market settings in the TAFE sector over recent years, culminating in changes to the funding model that were implemented by the government in 2012. These changes are designed to increase competition for students between public and private sector vocational training providers, and further changes for the sector have been foreshadowed.

One consequence of this changed operating environment in the TAFE sector has been a net deficit of $16.2 million in 2013—a $74.8 million deterioration from the $58.6 million surplus of 2012. The main driver for this result has been a decrease of $116.3 million—15 per cent—in government operating and capital grants.

These results suggest that many TAFEs have more work to do to effectively adapt to the sector's structural changes. While a majority of TAFEs reduced their expenditure during the year, the cost reductions and increases in student fee revenue were not sufficient to offset the reductions in operating funds from government.

The decline in financial performance is reflected in a significant decline in the financial sustainability of the sector. There are immediate or short-term financial challenges at five TAFEs causing their financial sustainability risk to be rated as high. A further eight TAFEs were assessed as medium risk, which continues the pattern of deterioration over the past five years. Against the trend, Chisholm Institute's financial sustainability risk rating improved in 2013.

Nevertheless, there are some positives that can be drawn from this report. Four TAFEs reported a surplus and improved financial performance in 2013—Chisholm, Goulburn Ovens, Kangan and Sunraysia. Restructuring arrangements undertaken early by these TAFEs—such as increasing the level of courses provided through third parties, changed course offerings, staff redundancies, campus rationalisation and reducing operating costs—have set them on a financially viable pathway, and they are to be commended.

More flexible financing arrangements for the sector were approved by the government in 2013, and TAFEs are now able to incur borrowings, subject to approval by the Treasurer. TAFEs currently have very low debt levels and although they now have more opportunity to use debt as a business tool, they should do so with caution. In particular, TAFEs should consider their capacity to service and repay debt in the context of their underlying results and any liquidity issues.

Disappointingly, performance reporting across the sector remains poor. Although clear audit opinions were issued on all 19 performance reports for 2013, the TAFE sector did not have a framework that mandates a core suite of relevant and appropriate key performance indicators, nor is there sufficient guidance to entities for establishing suitable targets and analysing performance. As a result, the sector's performance reporting remained underdeveloped and inconsistent, lacked clear direction and targets, and therefore did not facilitate comparison of performance across the sector or between years. This means that Parliament and the public are unable to monitor and assess the progress of TAFEs in this new operating environment.

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development has a key leadership role in assisting and supporting TAFEs to achieve effective performance reporting.

I note that a new performance reporting framework has been introduced for 2014 which will provide greater links between a TAFE's objectives and its key performance indicators. However, as the framework currently stands, it will not facilitate comparison of performance across the sector.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

August 2014

Audit Summary

This report covers the results of the 2013 financial audits of 27 entities, comprising 14 technical and further education (TAFE) institutes and the 13 entities they control.

Historically, the results of audits of universities and TAFEs were found in one report. This year, however, for the first time the results are presented in separate reports—Technical and Further Education Institutes: Results of the 2013 Audits and Universities: Results of the 2013 Audits.

This approach recognises the significant changes over recent years in the higher education and vocational education sectors. There have been changes to the market settings in both sectors, changes to legislation for both TAFEs and universities, and increased competition between public and private sector providers and between higher education and vocational training providers—with further changes signalled in the higher education sector. This means that TAFEs and universities are operating in increasingly disparate environments and are subject to different pressures on their operations. By reporting separately, we aim to provide the reader with greater clarity about the performance of entities in both sectors.

Conclusion

The quality of financial reporting in the TAFE sector is adequate. However, performance reporting remained underdeveloped and inconsistent, lacked clear direction and did not facilitate comparability across the sector. A new performance reporting framework being introduced in 2014 provides for greater links between strategic directions and key performance indicators, however, it does not address key elements aimed at providing greater comparison of performance across the sector.

The TAFE sector generated a net deficit of $16.2 million—a decrease of $74.8 million from the $58.6 million surplus in 2012. The results were affected by decreased government funding to the TAFE sector, partially offset by an increase in student fee revenue and reduced costs. The results suggest that many TAFEs have yet to adapt sufficiently to changes to the funding model and the new contestable environment.

Quality of financial reporting

Clear audit opinions were issued on the financial reports of 27 TAFE entities. An emphasis of matter paragraph was included in the financial report of Northern Melbourne Institute of TAFE (NMIT), drawing attention to a material uncertainty in its ability to continue as a going concern.

Overall, the financial report preparation processes of TAFEs produced accurate, complete and reliable information. In areas of monthly financial reporting and security over sensitive information better practice was noted. However, further improvement is needed in relation to all other financial report preparation areas. There was no noticeable improvement in financial report preparation in 2013 compared to previous financial years. In our future reports to Parliament, we intend to name the TAFEs that do not take appropriate steps to improve their practices.

Performance reporting

Clear audit opinions were issued on the performance reports required for the 14 TAFEs, four dual-sector universities and one associated entity for 2013. The TAFE sector, however, did not have a framework that mandated relevant and appropriate key performance indicators, nor was there any guidance to entities for establishing suitable targets and analysing performance. Accordingly, the sector's performance reporting was underdeveloped and inconsistent, lacked clear direction and did not facilitate comparability across the sector.

The lack of guidance resulted in:

- entities setting some indicators in isolation, which means they cannot be used to compare their performance against that of other entities

- the use of inconsistent methods for measuring performance against like indicators, resulting in information that cannot be used to compare performance between entities

- the use of measures that focus on pure quantitative inputs or outputs rather than considering performance in the context of the entity's strategic plan, relative size, geographic factors that affect performance, or efficiencies achieved

- failure to set targets for indicators—47percent of audited performance statements included targets for less than half the indicators they reported

- failure to provide performance results for the prior year, removing the ability to compare performance year on year—by eight of the 19 entities.

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) has recently implemented a strategic planning framework for the TAFE sector. The framework provides guidance and oversight on the development of key performance indicators linked to strategic plans and statements of corporate intent, targets, and analysing performance. While an improvement, the framework does not establish a core suite of indicators against which TAFEs are to report. Nor does it provide guidance to eliminate inconsistency in performance measurement against core indicators, setting targets at a level appropriate to each TAFE's individual circumstances and priorities, or on the development of relevant and appropriate indicators. Without these elements to enable comparison of performance across the sector and between entities, the value of performance reporting is diminished.

The challenge remains for DEECD to assist TAFEs to achieve effective performance reporting, and to put in place and demonstrate an appropriate level of oversight to mitigate the risk of misreporting in the newly competitive environment.

Financial results and sustainability

The 14 TAFEs generated a net deficit of $16.2 million, a decrease of $74.8 million from the $58.6 million surplus in 2012. The results were affected by a decrease of $116.3 million (15 per cent) in government operating and capital grants. The decrease was partially offset by an increase in student fee revenue and reduced costs.

These results suggest that many TAFEs have yet to effectively adapt to changes to the funding model announced in May 2012. The changes were designed to make vocational and education training funding more sustainable with a view to creating a sector characterised by sustainability, high quality and direct industry engagement. So far, the impact has been an increased reliance on student fee revenue in the contestable environment. While a majority of TAFEs reduced their expenditure during the year, the cost reductions and increases in student fee revenue were still not sufficient to offset reductions in the level of operating funds secured from government.

Consequently, there was a significant decline in the financial sustainability of the sector during 2013. We assessed the financial sustainability of five of the TAFEs as being high risk. This means that there are immediate or short-term financial challenges at these TAFEs that need to be addressed.

Eight TAFEs were assessed as medium risk. The remaining TAFE, Chisholm, improved its financial sustainability during the year from medium risk to low, against the trend, and this reflects the effective cost control strategies it implemented.

Against the trend, four TAFEs reported a surplus and improved financial performance in 2013. These were Chisholm, Goulburn Ovens, Kangan and Sunraysia.

NMIT reported a net operating deficit of $31.7 million, and projected substantial cash flow deficits for the next two years. NMIT has identified and commenced implementing various operational initiatives to improve its cash flows for 2014. The initiatives include reductions in staffing levels, increased student fees, changes to campus operations and various other restructuring arrangements. DEECD has also agreed to assist NMIT to secure bridging finance of $16 million to assist with its solvency and restructuring.

NMIT has been flagged as an overall high financial sustainability risk in this report. The combination of risk rating and predicted cash flows means this TAFE requires close monitoring.

Ten TAFEs had no debt at all at 30 June 2013, and the more flexible financing arrangements now open to TAFEs have increased borrowing options. Nevertheless, TAFEs should be cautious and assess their ability to repay associated financing costs, especially if operating results continue to deteriorate.

Internal controls

Controls over procurement across the TAFE sector were generally adequate. Documented policies exist and were comprehensive, and clear financial delegations had been established. Improvements can be made by documenting the key integrity activities that underpin a tender process, and by each TAFE defining high risk and complex procurement to set clear requirements for when probity plans need to be applied.

Probity issue at Box Hill Institute

During 2013, discrepancies were identified between employment entitlements agreed in 2008 between Box Hill Institute's then chief executive officer (CEO) and the board, and the employment agreement lodged with the office of the Minister for Higher Education and Skills as required under Ministerial Directions. The agreement between the CEO and the board provided additional entitlements, detailed in a formal letter of offer from the then board chair to the CEO. The additional entitlements were not standard entitlements under the state government's standard executive contract and were not provided to the minister's office for scrutiny.

Recommendations

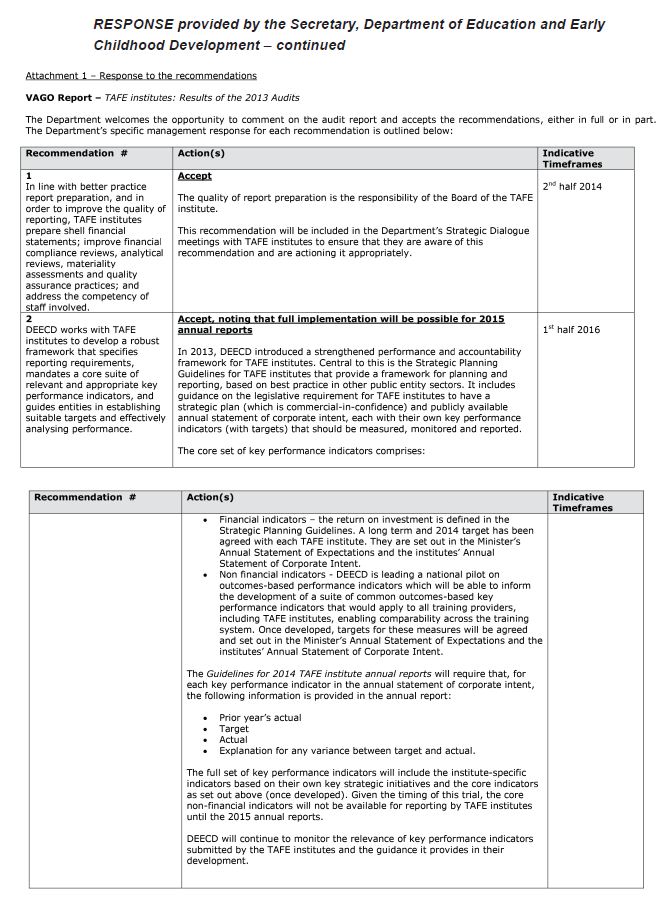

- That, in line with better practice report preparation, and in order to improve the quality of reporting, technical and further education institutes:

- prepare shell financial statements

- improve financial compliance reviews, analytical reviews, materiality assessments and quality assurance practices

- address the competency of staff involved.

- That the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development works with technical and further education institutes to develop a robust framework that specifies reporting requirements, mandates a core suite of relevant and appropriate key performance indicators, and guides entities in establishing suitable targets and effectively analysing performance.

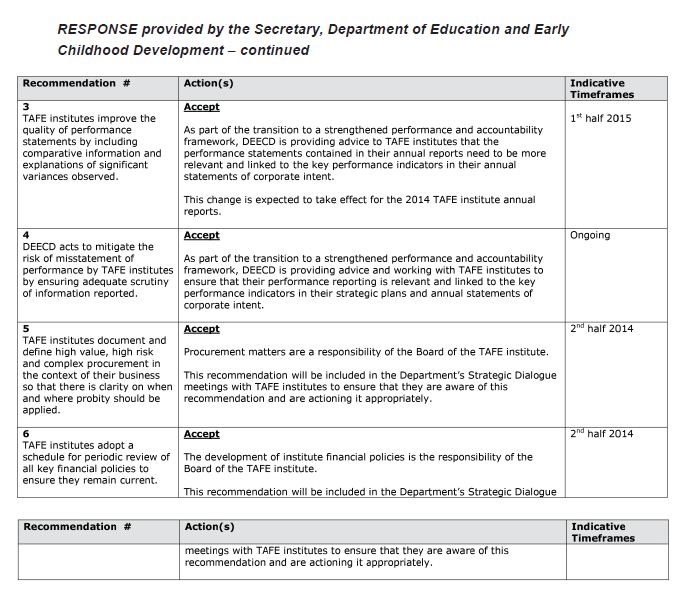

- That technical and further education institutes improve the quality of performance statements by including comparative information and explanations of significant variances observed.

- That the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development acts to mitigate the risk of misstatement of performance by technical and further education institutes by ensuring adequate scrutiny of information reported.

- That technical and further education institutes document and define high-value, high-risk and complex procurement in the context of their business so that there is clarity on when and where probity should be applied.

- That technical and further education institutes adopt a schedule for periodic review of all key financial policies to ensure they remain current.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report, or relevant extracts from the report, was provided to DEECD, the Department of Treasury and Finance and each of the 14 TAFEs with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix F.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Historically the results of audits of universities and technical and further education (TAFE) institutes were presented in one report, the Tertiary Education and Other Entities: Results of Audits report. However, this year for the first time the results are presented in separate reports—Technical and Further Education Institutes: Results of the 2013 Audits and Universities: Results of the 2013 Audits.

This approach recognises the significant changes over recent years in the higher education and vocational education sectors. There have been changes to the market settings in both sectors, changes to legislation for both TAFEs and universities, and increased competition between public and private sector providers and between higher education and vocational training providers—with further changes signalled in the higher education sector. This means that TAFEs and universities are operating in increasingly disparate environments. The entities in each sector are subject to different pressures on their operations. By reporting separately, we aim to provide the reader with greater clarity about the performance of entities in the two sectors.

1.1.1 This report

This report covers the 2013 results of 27 entities, comprising 14 TAFEs and the 13 entities they control. It is one of a suite of Parliamentary reports on the results of 2012–13 financial audits conducted by VAGO. The full list of reports can be found in Appendix A of this report.

A breakdown of the 27 entities covered by this report is set out in Figure 1A.

Figure 1A

TAFEs and controlled entities

Entity category |

2012 |

2013 |

|---|---|---|

TAFE |

14 |

14 |

Entities controlled by TAFEs(a) |

14 |

13 |

Total |

28 |

27 |

(a)Entities controlled by TAFEs generally comprise subsidiary companies.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Details of the entities covered in this report are set out in Appendix B.

The report informs Parliament about significant issues arising from the financial audits in addition to the assurance provided through audit opinions on financial reports and performance reports included in the respective entities' annual reports.

The report comments on the quality of financial reporting and the financial sustainability of TAFEs. It also comments on the effectiveness of controls over procurement, financial policies and financial delegations across the TAFE sector.

1.2 Recent changes to the TAFE sector

Over recent years, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development has acted to improve aspects of the accountability and oversight framework relating to the TAFE sector, in particular, by:

- reconstituting TAFE institutes in April 2013

- working to strengthen financial expertise and commercial acumen on TAFE institute boards progressively since April 2013

- removing chief executive officers (CEO) from TAFE institute boards in 2013 to clarify the relationship between governance and management, and reduce the potential for conflicts of interest, including relating to the remuneration and performance monitoring of the CEO

- making of Commercial Guidelines in April 2013 to provide accountabilities and parameters for TAFE commercial activities

- making of Strategic Planning Guidelines in April 2013 to establish a financial objective for TAFEs and set out a planning and reporting framework

- development of a performance monitoring framework to provide key stakeholders and the TAFE institutes with information on financial and non‑financial performance, and benchmarking data

- introducing an annual Minister's Statement of Expectations to TAFE institutes, which is a legislative requirement, as a mechanism for communicating additional expectations—including improved financial reporting—of government as owner, as opposed to funder.

Changes to the legislative framework and funding model, announced by the government in May 2012 became a catalyst for greater reliance by the sector on student tuition and other fees rather than on government grants.

During 2013, the government reiterated its commitment to competitive neutrality in the vocational training sector, and required TAFE institutes to demonstrate the capacity to operate commercially. In future, TAFEs will be required to maintain a specified return on non-current assets and cover their depreciation costs through their operations.

A rollout of $200 million in contestable funding over four years, referred to as the TAFE Structural Adjustment Fund, was announced in 2013, including $100 million in infrastructure funding. On 16 April 2014, it was announced that $40 million of this funding would be used to facilitate a merger between Advance and Central Gippsland TAFEs. It is intended that Federation University will then integrate the amalgamated institute into its operations from January 2016.

In a further restructuring arrangement, it was announced by the Minister for Higher Education and Skills on 23 May 2014 that $64 million of the contestable funding would be provided to support the amalgamation of Bendigo TAFE and Kangan Institute. The government has also announced $8.98 million for Sunraysia TAFE and $7.7 million for South West TAFE to undertake a number of projects to improve their financial sustainability.

1.3 Structure of this report

Figure 1B outlines the structure of this report.

Figure 1B

Report structure

Report part |

Description |

|---|---|

Part 2: Financial reporting |

Reports the results of the 2013 financial audits of 14 TAFEs and the 13 entities that they control. |

Part 3: Performance reporting |

Comments on performance reporting in the TAFE sector, including the results of the 2013 audits of 19 performance statements. |

Part 4: Financial results |

Summarises and analyses the financial results of 14 TAFEs, including financial performance for 2013. |

Part 5: Financial sustainability |

Provides insight into the financial sustainability of 14 TAFEs, based on the trends of five financial sustainability indicators over a five-year period. |

Part 6: Internal controls |

Assesses the internal controls, including over procurement, financial policies and financial delegations, across the TAFE sector. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

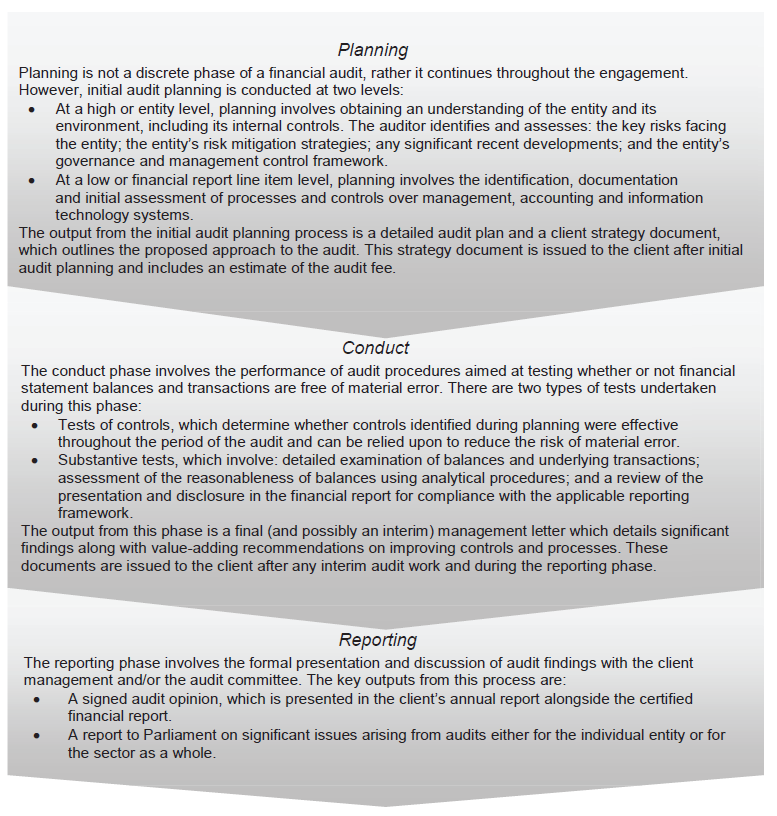

1.4 Audit of financial reports

An annual financial audit has two aims:

- to give an opinion consistent with section 9 of the Audit Act 1994, on whether the financial statements present fairly in all material respects in accordance with the Australian Accounting Standards and the Financial Management Act 1994

- to consider whether there has been wastage of public resources or a lack of probity or financial prudence in the management or application of public resources, consistent with section 3A(2) of the Audit Act 1994.

The financial audit framework applied in the conduct of the audits is set out in Appendix C.

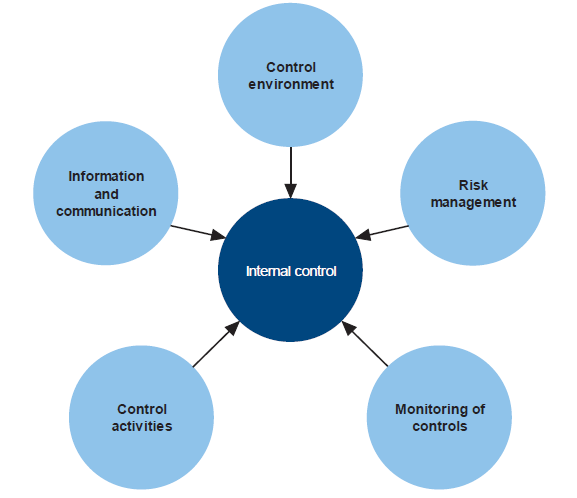

1.4.1 Audit of internal controls relevant to the preparation of the financial report

Internal controls are systems, policies and procedures that help an entity reliably and cost effectively meet its objectives. Sound internal controls enable the delivery of reliable, accurate and timely internal and external reporting.

Integral to the annual financial audit is an assessment of the adequacy of the internal control framework, and the governance processes, related to an entity's financial reporting. In making this assessment, consideration is given to the internal controls relevant to the entity's preparation and fair presentation of the financial report. This assessment is not used for the purpose of expressing an opinion on the effectiveness of the entity's internal controls.

An explanation of the internal control framework, and its main components, is set out in Appendix C. An entity's governing body is responsible for developing and maintaining its internal control framework.

Internal control weaknesses we identify during an audit do not usually result in a 'qualified' audit opinion because often an entity will have compensating controls in place that mitigate the risk of a material error in the financial report. A qualification is warranted only if weaknesses cause significant uncertainty about the accuracy, completeness and reliability of the financial information being reported.

Weaknesses in internal controls found during the audit of an entity are reported to its CEO and audit committee in a management letter.

Our reports to Parliament raise systemic or common weaknesses identified during our assessments of internal controls over financial reporting, across a sector.

1.5 Conduct of TAFE audits

The audits of the 14 TAFEs and 13 controlled entities were undertaken in accordance with the Australian Auditing Standards.

Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of this report was $170 000.

1.6 Audit of performance reports

Under section 8(3) of the Audit Act 1994, the Auditor-General is authorised to audit performance indicators of a public sector entity to determine whether they fairly represent the entity's actual performance. The Auditor-General uses this authority to audit the performance reports that are required to be prepared by the TAFE sector.

1.7 Subsequent events

1.7.1 Changes to reporting by dual-sector universities

Until 31 December 2013, four 'dual-sector' universities operated in Victoria, namely, Federation University (formerly University of Ballarat), RMIT University, Swinburne University of Technology and Victoria University. In addition to its higher education courses, a dual-sector university includes a TAFE component that delivers vocational education and training.

The Education and Training Reform Amendment (Dual Sector Universities) Act 2013 was enacted from 1 January 2014 and removed the requirement for dual-sector universities to make separate disclosure of their TAFE activities in their financial reports, or to include audited performance statements in their annual reports.

The legislative amendment reduces the reporting workload for the four universities and eliminates difficulties associated with separately reporting their TAFE and higher education activities given that administrative support and course delivery has been largely integrated over time.

From 1 January 2014, TAFE results of the four dual-sector universities will no longer be included in the Victorian whole-of-government consolidated financial statements.

2 Financial reporting

At a glance

Background

This Part covers the results from the 2013 audits of the 14 technical and further education (TAFE) institutes and the 13 entities they control.

Conclusion

The financial reports of the 27 TAFE entities received clear audit opinions, providing Parliament with confidence in these reports. Nevertheless, some entities have not acted to take up the range of better practice reporting elements which are designed to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of their financial report preparation process. In our future reports to Parliament, we intend to name the TAFEs that do not take appropriate steps to improve their practices.

Findings

- An emphasis of matter paragraph was included in the audit opinion for Northern Melbourne Institute of TAFE, drawing attention to a material uncertainty in its ability to continue as a going concern.

- Only 22 entities completed their financial reports within the mandated time frames.

Recommendation

That, in line with better practice report preparation, and in order to improve the quality of reporting, technical and further education institutes:

- prepare shell financial statements

- improve financial compliance reviews, analytical reviews, materiality assessments and quality assurance practices

- address the competency of staff involved.

2.1 Introduction

This Part covers the results of the 2013 audits of the 14 technical and further education (TAFE) institutes and the 13 entities they control.

The quality of an entity's financial reporting can be measured in part by the timeliness and accuracy of the preparation and finalisation of its financial report, as well as against better practice criteria.

Appendix B categorises the respective reporting frameworks and the completion time lines for the 27 entities.

2.2 Audit opinions issued

Independent audit opinions add credibility to financial reports by providing reasonable assurance that the information reported is reliable and accurate. A clear audit opinion confirms that the financial statements present fairly the transactions and balances for the reporting period, in accordance with the requirements of relevant accounting standards and legislation.

Clear audit opinions were issued on the financial reports of 27 entities for the year.

Emphasis of matter paragraph

In certain circumstances an audit opinion may draw attention to, or emphasise, a matter that is relevant to the users of an entity's financial report but does not warrant a qualification. Unqualified opinions can include an emphasis of matter (EOM) paragraph.

Northern Melbourne Institute of TAFE received an EOM opinion in 2013, which drew attention to the material uncertainty regarding its ability to continue as a going concern.

2.3 Quality of reporting

The quality of an entity's financial reporting can be measured in part by the timeliness and accuracy of the preparation and finalisation of its financial report, as well as against better practice criteria.

2.3.1 Accuracy

The frequency and size of errors in the draft financial reports submitted to audit are direct measures of the accuracy of those reports. Ideally, there should be no errors or adjustments required as a result of an audit.

Our expectation is that all entities will adjust any errors identified during an audit, other than those errors that are clearly trivial or clearly inconsequential to the financial report, as defined under the auditing standards.

The public is entitled to expect that any financial reports that bear the Auditor‑General's opinion are accurate and of the highest possible quality. Therefore, all errors identified during an audit should be adjusted, other than those that are clearly trivial.

Material adjustments

When we detect errors in the draft financial reports they are raised with management. Material errors need to be corrected before an unqualified audit opinion can be issued.

The entity itself may also change its draft financial reports after submitting them to audit if their quality assurance procedures identify that the draft information is incorrect or incomplete.

In relation to the 2013 audits, 25 material financial balance adjustments were made compared to 18 in the prior year. The adjustments related mainly to accrual accounting items associated with the preparation of the financial report. Adjustments were also required in respect of a number of one-off transactions, including the transfer of the student management system from the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, and accounting treatment of grant funding. The adjustments resulted in changes to the net result and/or the net asset position of entities.

In addition to the financial balance adjustments, there were two disclosure errors that required adjustment in 2013 (two in 2012). Other disclosure adjustments in 2013 related to the completeness of accounting policies and executive officer remuneration disclosures, as well as the classification of cash and short-term investments.

All material errors were adjusted prior to the completion of the financial reports.

2.3.2 Timeliness

Timely financial reporting is key to providing accountability to stakeholders, and enables informed decision-making. The later reports are produced and published after year end, the less useful they are.

The Financial Management Act 1994 requires an entity to submit its audited annual report to its minister within 12 weeks of the end of financial year. Its annual report should be tabled in Parliament within four months of the end of financial year.

In 2013, 22 entities completed their financial reports within their mandated time frames. The remaining five entities failed to finalise their financial reports within 12 weeks of their applicable balance date, although three of these entities were only one day late. The remaining two were late due to additional work they undertook relating to going concern issues.

Appendix B sets out the dates the 2013 financial reports were finalised.

2.3.3 Better practice

An assessment of the quality of financial reporting processes of the TAFEs was conducted against better practice criteria—detailed in Appendix C—using the following scale:

- no existence—process not conducted by the entity

- developing—partially encompassed in the entity's financial reporting process

- developed—entity has implemented the process, however, it is not fully effective or efficient

- better practice—entity has implemented efficient and effective processes.

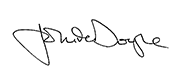

The results are summarised in Figure 2A.

Figure 2A

Results of assessment of report preparation processes against better practice elements

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Monthly financial reporting and security over sensitive information were assessed as the strongest areas, with a significant majority of entities' processes assessed as either 'better practice' or 'developed'. Further improvement is needed in relation to all other areas, particularly:

- preparation of shell statements

- materiality assessments

- rigorous analytical reviews

- quality assurance.

It was disappointing that there was no noticeable improvement in 2013, while some areas deteriorated in comparison to 2012.

Assessments against better practice elements have been reported over a number of years. Nevertheless, some entities have not acted to take up the range of elements which are designed to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of their financial report preparation. In our future reports to Parliament, we intend to name the TAFEs that do not take appropriate steps to improve their practices.

Recommendation

- That, in line with better practice report preparation, and in order to improve the quality of reporting, technical and further education institutes:

- prepare shell financial statements

- improve financial compliance reviews, analytical reviews, materiality assessments and quality assurance practices

- address the competency of staff involved.

3 Performance reporting

At a glance

Background

This Part covers the results of the 2013 audits of performance statements for the 14 technical and further education (TAFE) institutes, four dual-sector universities and one associated entity that are required to include an audited statement of performance in their annual report.

Conclusion

Clear audit opinions were issued on all 19 performance reports. However, the TAFE sector did not have a framework that mandated relevant and appropriate key performance indicators, nor was it provided with sufficient guidance for establishing suitable targets and analysing performance. Accordingly, the sector's performance reporting was underdeveloped and inconsistent, lacked clear direction and did not facilitate comparability across the sector. From 2014, TAFEs are to implement a strategic planning framework requiring them to set key performance indicators clearly linked to their key strategies. While an improvement, the framework does not establish a core suite of indicators against which TAFEs are to report, therefore, the value of the performance reporting is diminished.

Findings

- Forty-seven per cent of performance reports included targets for less than half of the performance indicators.

- Eight of the 19 entities did not include data to enable comparison of year on year performance.

Recommendations

- That DEECD work with TAFEs to develop a robust framework that specifies reporting requirements, mandates a core suite of relevant and appropriate key performance indicators, and guides entities in establishing suitable targets and effectively analysing performance.

- That TAFEs improve the quality of performance statements by including comparative information and explanations of significant variances observed.

- That DEECD act to mitigate the risk of misstatement of performance by TAFEs by ensuring adequate scrutiny of information reported.

3.1 Introduction

Victoria's 14 technical and further education (TAFE) institutes, the Centre for Adult Education and the TAFE components of:

- Ballarat University (known as Federation University from 1 January 2014)

- RMIT University

- Swinburne University of Technology

- Victoria University

are required to present audited performance statements in their annual reports.

The requirement to prepare performance statements was established by a November 2008 executive memorandum from the former Department of Innovation, Industry and Regional Development.

The Audit Act 1994 empowers the Auditor-General to audit any performance indicators in the report of operations of an audited entity to determine whether they:

- are relevant to any stated objectives of the entity

- are appropriate for the assessment of the entity's actual performance

- fairly represent the entity's actual performance.

This Part comments on the results of our 2013 audits of performance reports of 19 entities, and the progress made by the sector in regards to quality performance reporting.

3.2 Audit opinions issued

Our audits of performance statements produce opinions on whether the results reported are presented fairly and whether they have been prepared in accordance with the Financial Management Act 1994. The opinions do not conclude on the relevance or appropriateness of the performance information reported.

Clear audit opinions were issued on all 19 performance reports audited for 2013.

3.3 Quality of reporting

Mandated performance indicators that are relevant and appropriate, with suitable targets and adequate guidance, had not been established. In the absence of such direction, performance reporting in the TAFE sector remained underdeveloped and inconsistent, lacked clear direction and did not enable comparison of performance across the sector.

In 2013, this lack of guidance resulted in:

- entities setting some indicators in isolation, which means they cannot be used to compare their performance against that of other entities

- the use of inconsistent methods for measuring performance against like indicators, resulting in information that cannot be used to compare performance between entities

- the use of measures that focus on pure quantitative inputs or outputs rather than considering performance in the context of the entity's strategic plan, relative size, geographic factors that affect performance, or efficiencies achieved

- failure to set targets for indicators—47percent of performance statements audited included targets for less than half the indicators they reported

- failure to provide performance results for the prior year, removing the ability to compare performance year on year—for eight of the 19 entities.

3.3.1 Setting targets

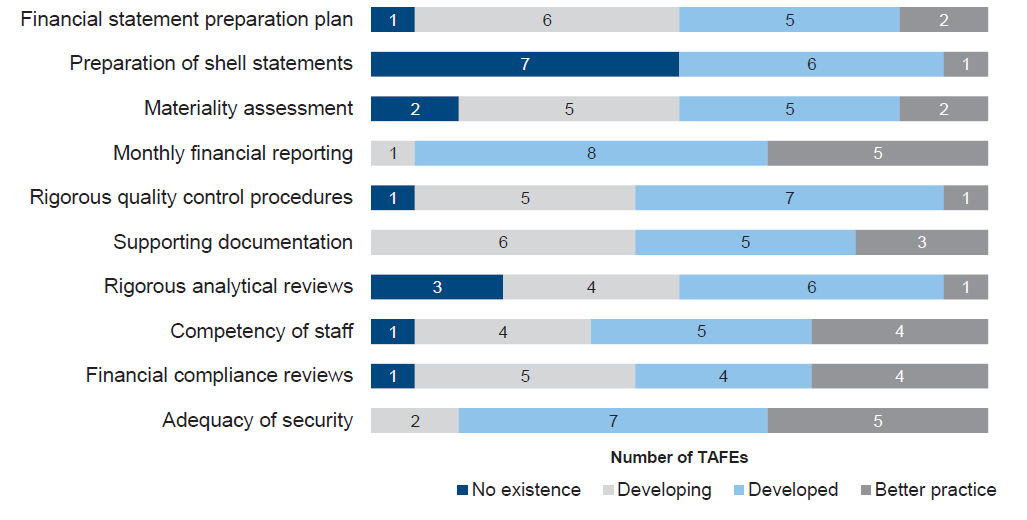

While target setting was still poor in 2013, it had at least improved—in 2013 seven entities set targets for each of their performance indicators, compared with four in 2012.

Figure 3A shows the performance of entities in 2013 in relation to target setting.

Figure 3A

Target setting by TAFEs

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

However, where targets were set, there was significant variation across entities. Figure 3B shows the range of targets set across the sector for four commonly reported indicators.

Figure 3B

Range in targets set for selected indicators

|

Target |

Working capital ratio |

Student satisfaction (%) |

Net operating margin (%) |

Revenue per staff FTE ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Median |

1.51 |

82.3 |

1.8 |

134 957 |

|

Highest |

4.52 |

93.0 |

7.8 |

171 387 |

|

Lowest |

0.19 |

75.0 |

-18.0 |

85 106 |

Note: 'FTE' refers to full-time equivalent positions.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Targets can legitimately vary between entities if priorities of entities differ, or if entities have different maturity levels. However, in many instances targets reflected the expected results, rather than a stretch target. To operate as drivers of performance, targets should be aspirational—neither too low as to be too easily achieved, nor too high as to be impossible to achieve.

3.3.2 Analysing performance

Performance reporting should be accompanied by commentary analysing variances from year to year and why prior year performance was exceeded or not. Such commentary provides users and the broader community with a clearer picture of the challenges faced or achievements made during the current year.

In 2013, 14 entities provided explanations of significant variances between actual and target or prior year results. However, in many cases the 'analysis' simply stated that there was a variance without explaining why.

3.4 Developments and challenges in performance reporting

Our 2013 audits show that the sector needs to improve significantly before it achieves a satisfactory standard of performance reporting.

On 17 April 2013, the Minister for Higher Education and Skills approved Strategic Planning Guidelines that require TAFEs to develop a strategic plan and include key performance indicators clearly linked to their key strategies. It acknowledged that the measures may vary across TAFEs based on the strategic goals set by their governing boards. Accordingly, TAFEs developed strategic plans in 2013 in consultation with the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD). The plans are to be implemented in 2014.

The framework provides guidance and oversight on the development of key performance indicators (KPI) linked to strategic plans and statements of corporate intent, suitable targets, and analysing performance.

While an improvement, the framework does not establish a core suite of indicators against which TAFEs are to report. Further, it does not provide guidance to eliminate inconsistency in performance measurement against core indicators, setting targets at a level appropriate to each TAFE's individual circumstances and priorities, or on the development of relevant and appropriate indicators.

The Victorian TAFE sector is diverse and ranges from organisations with revenues of $20 million to $170 million, from rural institutes to metropolitan institutes, and from niche providers to full service providers. It is entirely appropriate for a TAFE to develop a range of KPIs specific to its own circumstances, including size, geographic factors that affect performance and specific priorities.

Nevertheless, VAGO considers that TAFEs should also be required to report against a core suite of KPIs that are comparable across the sector and between TAFEs regardless of the size, geographic factors and specific priorities of individual TAFEs. This would enable comparison of operating and financial performance of TAFEs on some level despite their differences. Without the ability to compare performance across the sector and between entities, the value of performance reporting is diminished.

DEECD should work with TAFEs to develop a robust framework that specifies appropriate reporting requirements. This framework should enable entities to establish and report on suitable targets in a manner which facilitates comparison of performance across the sector.

3.4.1 Potential impact of performance reporting due to competition

Unlike other public sector entities subject to performance reporting, TAFEs operate in direct competition with each other and private sector operators. In addition, as government funding to the sector has reduced, TAFEs have become increasingly reliant on other revenue streams—principally student fees—to ensure their sustainability. In this context, attracting students has become even more critical.

Increased competition increases the risk that performance will be misrepresented in order to seek an advantage in the market. With the development of performance reporting, potential students, the public and other report users can use these reports to compare performance and guide decision-making.

To mitigate the risk of misstatement of performance and to ensure the quality and consistency of performance information reported by TAFEs, DEECD will need to establish and demonstrate an appropriate level of oversight.

3.5 Future audit approach

In our report Tertiary Education and Other Entities: Results of the 2012 Audits, we announced our intention to expand our audit of performance indicators for the TAFE sector in future periods. In our 2014 audit report, we intend to continue to express an opinion on the fair presentation of performance indicators and compliance with requirements, but provide entities with comments on the relevance and appropriateness of performance indicators through management letters.

From 2015, our audit opinion will also address the relevance and appropriateness of the indicators and whether they fairly present performance. Where these standards are not met, a qualified audit opinion may be issued on performance statements.

This approach will require the support of DEECD to achieve more transparent and meaningful reporting on TAFE performance to the community. Without this guidance, performance information will continue to be arbitrarily reported and results will be incomparable across the sector.

Recommendations

- That the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development works with technical and further education institutes to develop a robust framework that specifies reporting requirements, mandates a core suite of relevant and appropriate key performance indicators, and guides entities in establishing suitable targets and effectively analysing performance.

- That technical and further education institutes improve the quality of performance statements by including comparative information and explanations of significant variances observed.

- That the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development acts to mitigate the risk of misstatement of performance by technical and further education institutes by ensuring adequate scrutiny of information reported.

4 Financial results

At a glance

Background

This Part analyses the financial results of the 14 technical and further education (TAFE) institutes for the year ended 31 December 2013.

Conclusion

The 14 TAFEs generated a net deficit of $16.2 million, a decrease of $74.8 million from the $58.6 million surplus in 2012. Ten TAFEs reported a reduced financial result in 2013, with seven of these reporting an operating deficit in 2013 compared with four in 2012. The results were affected by a decrease of $116.3 million—15 per cent—in government operating and capital grants. This was partially offset by a reduction in costs and an increase in student fee revenue.

These results suggest that many TAFEs have yet to effectively adapt to changes to the funding model announced in May 2012, designed to make vocational and employment training funding arrangements more sustainable. The changes have increased the sector's reliance on other revenue streams, such as student fee revenue, in the contestable environment.

Findings

- A majority of TAFEs reduced their expenditure during the year. However, these reductions and increases in student fee revenue were not sufficient to offset the reductions in operating grants from government.

- Against the trend, four TAFES reported a surplus and improved financial performance in 2013—Chisholm, Goulburn Ovens, Kangan and Sunraysia.

- Northern Melbourne Institute of TAFE (NMIT) recognised a net operating deficit of $31.7 million. NMIT projected substantial cash-flow deficits for the next two years. As a result, NMIT is implementing operational initiatives to improve its cash flows for 2014, and the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development has agreed to support NMIT in securing bridging finance of $16 million to assist with solvency and restructuring arrangements.

- Capital expenditure by the sector has declined over the past three years and the financial position of TAFEs has deteriorated.

- Total debt for the sector remains low compared to equity.

4.1 Introduction

Accrual-based financial statements enable assessment of whether entities are generating sufficient surpluses from operations to maintain services, fund asset maintenance and retire debt. The ability to generate surpluses is subject to the regulatory environment in which entities operate, and their ability to minimise costs and maximise revenue.

4.2 Financial results

4.2.1 Financial performance

The 14 technical and further education (TAFE) institutes generated a collective deficit of $16.2 million in 2013. This was a decrease of $74.8 million from the collective surplus of $58.6 million in 2012. Ten TAFEs reported a reduced financial result in 2013, with seven reporting an operating deficit in 2013—compared with four in 2012.

The lower results largely reflected a 15 per cent—$102.9 million—decrease in state government operating grants during 2013.

These results suggest that many TAFEs have yet to effectively adapt to changes to the funding model, announced in May 2012. The changes were designed to make vocational and employment training funding arrangements more sustainable, with a view to creating a sector characterised by sustainability, high quality and direct industry engagement. To date, the impact has been an increase in the sector's reliance on other funding streams, including student fee revenue, in the new more contestable environment.

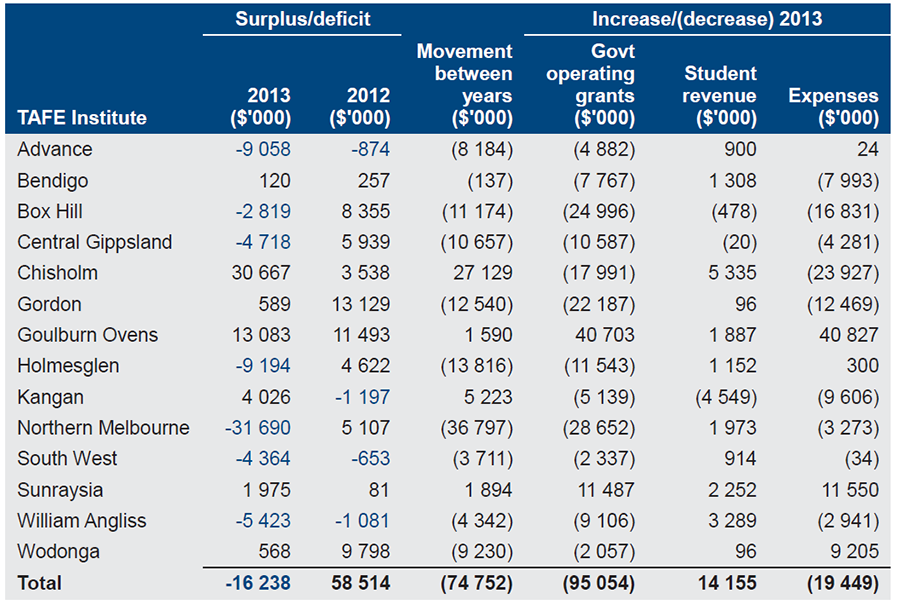

Figure 4A shows that while a majority of TAFEs reduced their expenditure during 2013, the cost reductions and increases in student fee revenue were not sufficient to offset the reductions in operating grants secured from government.

Figure 4A

Net surplus/deficit by TAFE and changes in funding sources from 2012 to 2013

Note: Government operating grants include Commonwealth and state funding.

Note: Figures in blue indicate a deficit. Figures in brackets indicate a decrease.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Northern Melbourne Institute of TAFE (NMIT) recognised a net operating deficit of $31.7 million and negative cash outflows from operating activities of $23.3 million in its 2013 financial report. This was predominantly driven by a $28.7 million—or 41 per cent—decrease in contestable government operating grants for TAFE students. NMIT has projected further cash flow deficits for the next two years. As a result, NMIT is implementing operational initiatives to improve its cash flows for 2014, and the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development has agreed to support NMIT in securing bridging finance of $16 million to assist with the entity's solvency and restructuring arrangements.

Another two TAFEs failed to achieve significant cost savings and consequently their operating results deteriorated. Advance and Holmesglen reported increases in expenses, while South West achieved a marginal reduction in costs only.

This suggests that these TAFEs, along with NMIT, have not responded sufficiently to the changed funding and operating conditions.

In 2013, Wodonga amalgamated with Driver Education Centre of Australia, leading to increased costs for the period.

Four TAFEs went against the downward trend and improved their financial performance in 2013. These TAFEs—Chisholm, Goulburn Ovens, Kangan and Sunraysia—are to be commended on their response to the changed operating environment. Restructuring arrangements undertaken by these TAFEs included:

- Goulburn Ovens and Sunraysia increased the number of courses provided by third parties rather than by their own employees. This service provision model enabled them to secure increases of $40.4 million and $11.3million in government grants, respectively, to cover the costs of the third party providers.

- Chisholm and Kangan embarked early on a program of staff redundancies in 2012 in order to reduce expenditure to address announced funding cuts.

- Kangan substantially reduced its operating costs.

Revenue

TAFEs generate their revenue from government grants, student fee revenue, investment revenue and various fees and charges.

In 2013, TAFEs collectively generated revenue of $1.08 billion, $89.4 million less than in 2012. The decrease was mainly due to a net reduction of $95.0 million in government operating grants—that is, a $102.9 million reduction in state operating grants offset by a $7.8 million increase in Commonwealth operating grants.

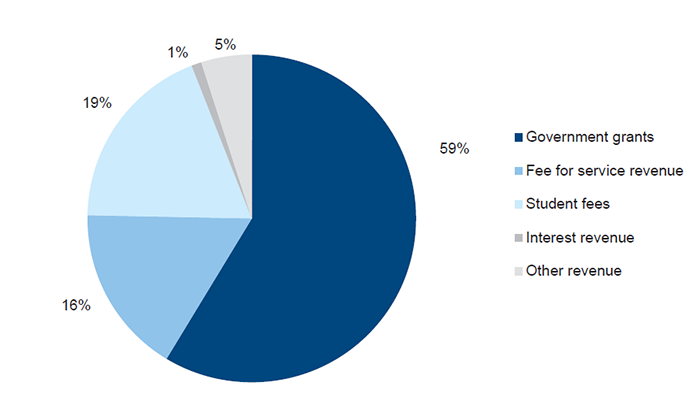

Despite the net decrease, government grants remained the largest component of operating revenue for TAFEs, representing 59 per cent of total revenue in 2013 (65 per cent in 2012), as shown in Figure 4B.

Figure 4B

Revenue composition, 2013

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

TAFEs also received reduced state capital grants ($14.5 million) and Commonwealth capital grants ($6.7 million) during 2013. When added to the reductions in operating grants, this resulted in an overall decrease in government grants of $116.3 million for the year.

Trends in student fee revenue

Recent policy changes were designed to increase competition between private and public sector training providers. As a result, it is important that TAFEs proactively target students and adjust their marketing activities and course design to attract enrolments in the domestic and international student markets.

Over the past five years, revenue from student fees has increased by 14.2 per cent, mainly driven by domestic student fee revenue. Total student fee revenue increased by 7.8 per cent to $195.3 million in 2013.

International students

International student fee revenue has fluctuated year on year, but overall has decreased by 26.4 per cent over the five-year period. However, this revenue stream continued to be important to TAFEs. In 2013 it generated $92.2 million ($105.5 million in 2012), or 47.2 per cent of total student fee revenue for the year. Student fees from offshore operations comprised $33.7 million, or 36.6 per cent of international student fee revenue ($40.7 million in 2012).

Although they represent only around 5 per cent of total student numbers, international students generate substantially higher revenue per student than do domestic students, and are an important factor in the ongoing viability of individual TAFEs and the sector.

New international student enrolments increased to 7 400 in 2013 (6 500 in 2012).

Domestic students

Between 2009 and 2013, total fees from domestic students increased by 125.2 per cent. The increase was due to increased TAFE fees for some courses, partially offset by a decrease in domestic student numbers.

New enrolments for domestic students decreased in 2013 to 196 500 (208 400 in 2012).

Expenses

In 2013, the 14 TAFEs collectively incurred operating expenses of $1.1 billion, a decrease of $19.4 million or 1.8 per cent from 2012. Although the decline in TAFE spending was much less than the decline in revenue during the year, the full effect of reduced employee numbers should impact on costs over the next two years.

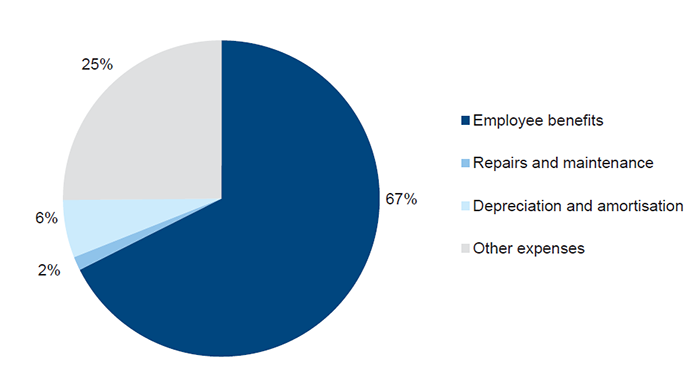

Figure 4C shows the composition of TAFE expenditure for 2013.

Figure 4C

Expenditure composition, 2013

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Employee-related costs remained the most significant expenditure item, representing 67 per cent of total expenses in 2013 (67 per cent in 2012). Expenditure composition for the TAFE sector was consistent with 2012.

4.3 Financial position

TAFEs carried land and buildings representing 76.8 per cent of their total assets on their balance sheets at 31 December 2013. However, their revenue base is not tied to the value of their assets and most of their assets cannot be readily sold to obtain funds.

The financial objective for an entity should be to maintain and improve its asset base and related service provision, while managing its levels of debt. Capital expenditure has declined over the past three years, and an increase in government loans provided in 2013 indicates that the financial position of TAFEs is deteriorating. However, total debt for the sector remains low compared to equity.

4.3.1 Assets

The total value of TAFE assets increased by $38.2 million to $2.43 billion at 31 December 2013, mainly as a result of:

- a $73.9million increase in intangible assets due to the transfer of the student management system asset from the state government to the TAFE sector upon its completion, offset by

- a $33.9million decrease in property, plant and equipment that was mainly due to the annual depreciation charge.

Valuations of land and buildings during 2013 resulted in asset write-downs at the following TAFEs:

- Advance—an impairment to capital works in progress of $2.0 million due to significant doubt over whether the project will proceed

- NMIT—a revaluation decrement to buildings of $14.3 million due to revaluation of certain buildings held for sale to market value, rather than carried at depreciated replacement cost

- Sunraysia—a revaluation decrement of $12.2 million to land, due to a decrease in the assessed valuation since the last revaluation in 2009.

4.3.2 Liabilities

At 31 December 2013, TAFEs had total liabilities of $238.9 million. Debt increased by $16.4 million in 2013 to 7 per cent of total TAFE liabilities (less than 1 per cent in 2012). The increase was due to loans made to Central Gippsland, Gordon, Kangan, South West and William Angliss Institute. Ten TAFEs had no debt at all at 30 June 2013. However, total debt for those entities, and the sector as a whole, remained low compared to equity. Nevertheless, TAFEs should be cautious and assess their ability to repay associated financing costs, especially if operating results continue to deteriorate.

An increase of $18 million in payables was partially offset by a $9.3 million decrease in employee benefit provisions. The decrease was due to staff reductions resulting from structured redundancy programs across the sector.

Provisions (42.8 per cent) and payables (46.0 per cent) continued to be the major components of total TAFE liabilities.

5 Financial sustainability

At a glance

Background

To be financially sustainable, entities need to be able to meet current and future expenditure as it falls due. They also need to absorb foreseeable changes and risks, and adapt their revenue and expenditure policies to address changes in their operating environment. This Part provides an insight into the financial sustainability of technical and further education (TAFE) institutes based on an analysis of the trends in their key financial indicators over the past five years.

Conclusion

The sector's financial sustainability deteriorated in 2013, continuing a pattern of deterioration over the past five years. TAFEs are finding it difficult to generate surpluses and to replace assets from operating activities. As at 31 December 2013, 10 TAFEs had no debt at all, and the more flexible financing arrangements now open to them have increased borrowing options. Nevertheless, TAFEs should be cautious and assess their ability to repay associated financing costs, especially if operating results continue to deteriorate.

Findings

- The financial sustainability of five TAFEs was assessed as high risk due to significant operating deficits. A further eight were assessed as having a medium financial sustainability risk due to poor self-financing and capital replacement indicators.

- Chisholm Institute's risk rating improved against the trend, reflecting the effective cost control strategies it implemented.

- Northern Melbourne Institute of TAFE (NMIT) has an overall high financial sustainability risk. Based on historical data, its liquidity risk is low. Future projections showed cash flow deficits over the next two years. As a result, NMIT is implementing operational initiatives to improve its cash flows for 2014. To assist with the projected cash shortfall and necessary restructuring arrangements, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development agreed to support NMIT in securing bridging finance of $16 million.

5.1 Introduction

To be financially sustainable, entities need to be able to meet their current and future expenditure as it falls due. They also need to absorb foreseeable changes and risks, and adapt their revenue and expenditure policies to address changes in their operating environment.

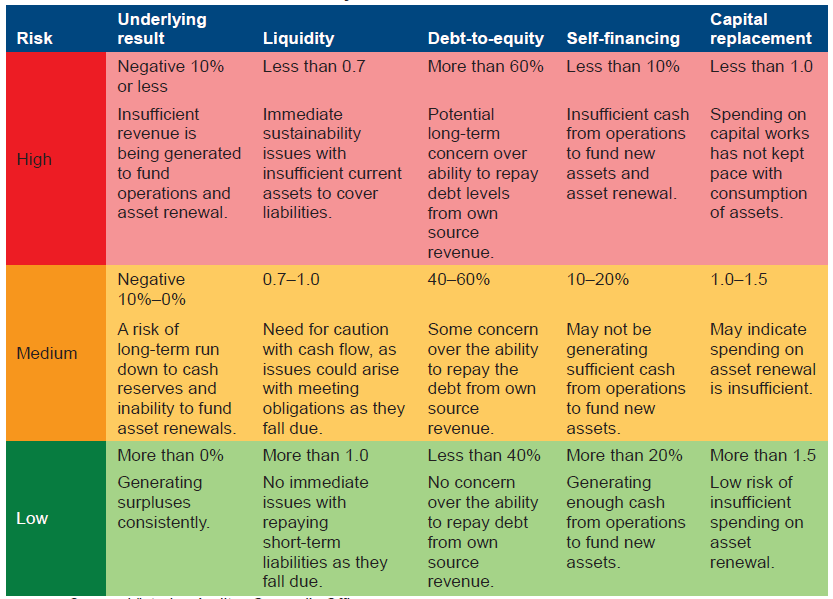

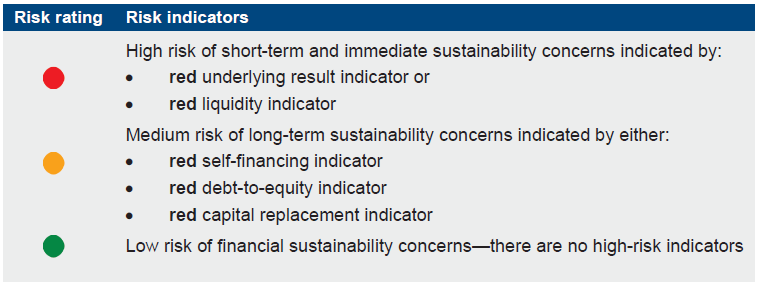

This Part examines the financial sustainability of the 14 technical and further education (TAFE) institutes through analysis of five financial sustainability indicators over a five‑year period. Appendix D describes the sustainability indicators and risk assessment criteria used in this report.

To form a definitive view of any entity's financial sustainability, a holistic analysis that moves beyond financial indicators would be required, including an assessment of the entity's operations and the regulatory environment in which the entity operates. These additional considerations are not examined in this report.

5.2 Financial sustainability risk assessment

5.2.1 Overall assessment

Overall the financial sustainability risk assessment for the TAFE sector deteriorated in 2013.

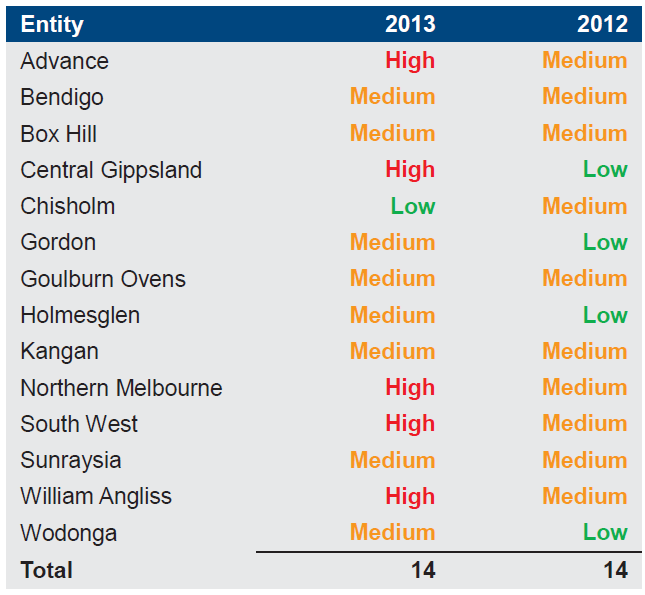

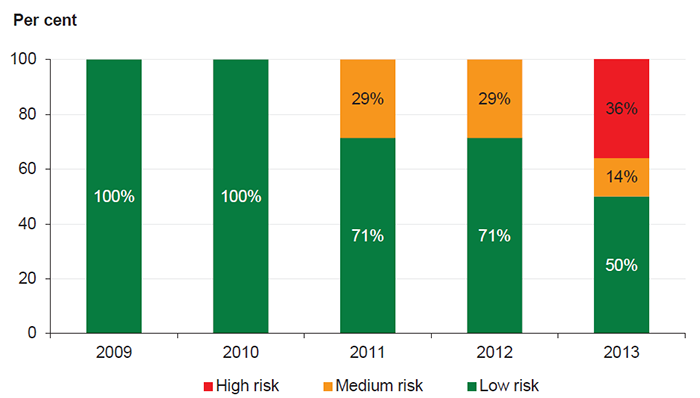

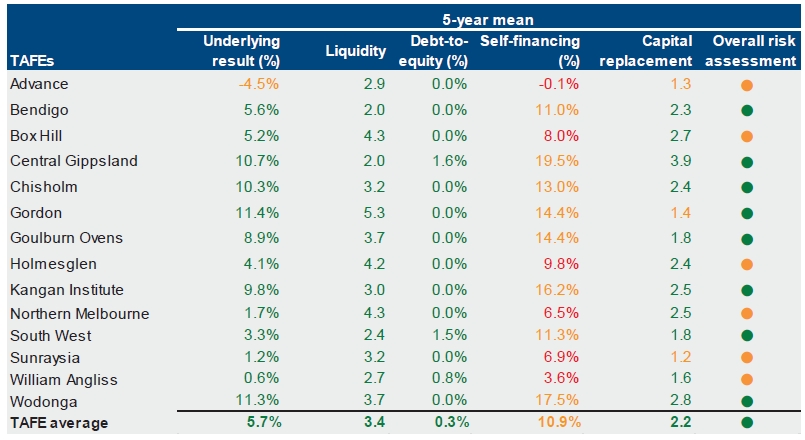

Figure 5A shows that the number of TAFEs with a high financial sustainability risk increased from none in 2012 to six in 2013.

Figure 5A

Two-year financial sustainability risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Five TAFEs were assessed as having a high risk to their financial sustainability due to significant operating deficits. A further eight TAFEs were assessed as medium risk due to their poor self‑financing and capital replacement indicators.

Only Chisholm Institute was assessed as having a low risk to its financial sustainability. The improvement in its risk rating in 2013 was due to the substantial changes made to its staffing and operating arrangements over the past two years, the cost savings from which were realised in 2013.

5.2.2 Summary of trends in risk assessments over the five-year period

To further understand the results, we analysed data for the five indicators from the previous five years. The relevant data, and the basis for calculating the indicators, is reproduced in Appendix D.

The five-year data shows that TAFEs are finding it increasingly difficult to generate surpluses and replace assets from operations. On the positive side, debt levels remain low and more flexible financing arrangements were approved for the sector during 2013. This provides opportunities for TAFEs. However, they need to carefully assess their ability to repay associated financing costs should their operating results continue to deteriorate.

When the risk assessments for each of the five sustainability indicators are analysed for the sector they show that over the five years to 2013:

- Underlying result—the number of TAFEs in the medium- and high-risk categories has risen significantly. The decline commenced in 2011, following a deterioration in student numbers, and fell at a greater rate in 2013.

- Liquidity—all TAFEs had low liquidity risk over the five-year period.

- Self-financing—the number of TAFEs in the high-risk category has increased from five to 11, showing a steady deterioration over the past three years.

- Capital replacement—the position has deteriorated significantly from 2011 onwards. Eleven of the 14 TAFEs (79 per cent) now have a risk assessment of medium or high. This means that their ability to fund asset replacement using funds generated from operating activities is restricted, and as a consequence, the condition of TAFE assets may start to deteriorate.

- Debt-to-equity—all TAFEs have had low debt-to-equity risk over the five‑year period.

Impact of changes in legislation and funding model on sustainability

Changes to the legislative framework and funding model, announced in May 2012, became a catalyst for greater reliance by the sector on student tuition and other fees rather than on government grants. The changes have had a significant impact on TAFEs, specifically:

- From 1 January 2013 the full impact of the previously announced changes to the funding model came into effect and most TAFEs took action to alleviate expected revenue shortfalls. As a result, the cost to students undertaking some vocational education and training courses increased, contributing to a decline in student participation. New student commencements were down in 2013 compared to 2012, while total student numbers also declined. TAFEs also reacted by reducing or changing course offerings.

- The sector also focused on reducing costs through staff redundancies. The full impact of action taken to reduce employee numbers should be realised over the next two years.

- Four TAFEs closed campuses between 2012 and 2013.

- Government capital funding declined by 36percent, and most TAFEs reduced 'non-essential' capital expenditure, resulting in substantially reduced capital expenditure across the sector in 2013.

Cost savings for the sector as a whole, however, were limited and inconsistent.

During 2013, the government reiterated its commitment to competitive neutrality in the vocational training sector, and required TAFE institutes to demonstrate the capacity to operate commercially. In future, TAFEs will be required to maintain a specified return on non-current assets and cover their depreciation costs through their operations.

A rollout of $200 million in contestable funding over four years, referred to as the TAFE Structural Adjustment Fund, was announced in 2013, including $100 million in infrastructure funding. On 16 April 2014 it was announced that $40 million of this funding would be used to facilitate a merger between Advance and Central Gippsland TAFEs. It is intended that Federation University will then integrate the amalgamated institute into its operations from January 2016.

In a further restructuring arrangement, it was announced by the Minister for Higher Education and Skills on 23 May 2014 that $64 million of the contestable funding would be provided to support the amalgamation of Bendigo TAFE and Kangan Institute. The government has also announced $8.98 million for Sunraysia TAFE and $7.7 million for South West TAFE to undertake a number of projects to improve their financial sustainability.

5.3 Five-year trend analysis

This section provides analysis and commentary on each indicator's trend for the past five years.

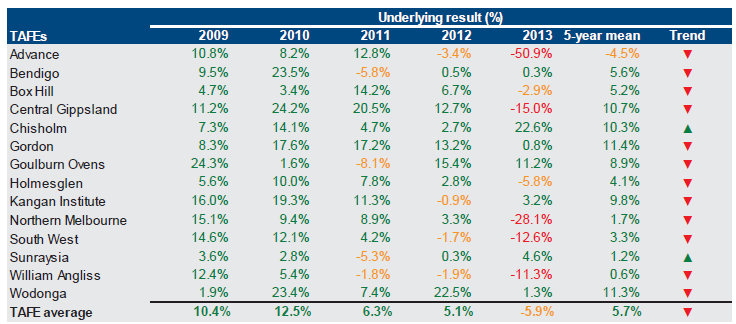

5.3.1 Underlying result

The average underlying result for TAFEs has declined over the five-year period, with 12 of the 14 TAFEs recording a lower result in 2013 than in 2009. The decline highlights the difficulties faced by the sector during a period of reduced enrolments following changes to the funding model.

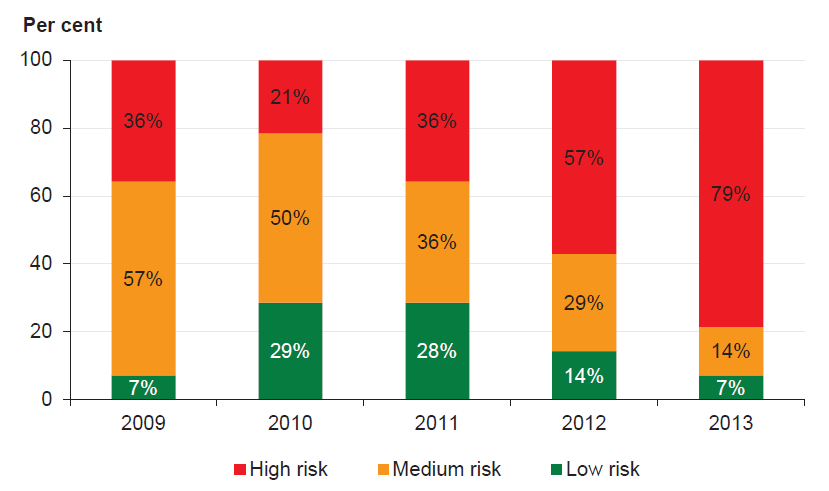

Figure 5B shows a sharp deterioration in the underlying result indicator, with the number of TAFEs moving into either the high- or medium-risk category substantially increasing in 2013.

Figure 5B

Underlying result risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Seven of 14 TAFEs generated an operating deficit in 2013 (four in 2012), with only three TAFEs reporting an improved underlying result. The deteriorating position indicates that cost savings are not being realised at the same rate as revenue is declining.

Advance TAFE was assessed as high risk in 2013, with an underlying result of negative 50.9 per cent. This means that the operating deficit was half of total revenue in 2013, indicating that this TAFE is in dire financial trouble.

Funding will be provided through the TAFE Structural Adjustment Fund to support Advance TAFE and its amalgamation with Central Gippsland and eventually, Federation University.

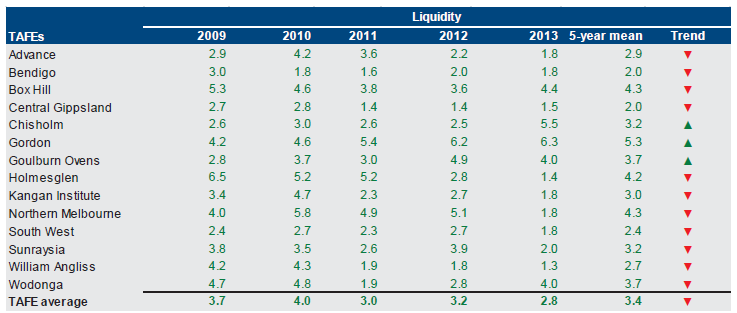

5.3.2 Liquidity

The liquidity indicator is a measure of whether an entity has sufficient cash to meet its liabilities when they become due. All 14 TAFEs were assessed as having low risk for the liquidity indicator. Across the sector, however, performance against this measure has declined over the five-year period for 11 of 14 TAFEs, mainly due to a reduction in cash holdings and the overall level of trade creditors increasing by $55.6 million (106 per cent) since 2009.

While Northern Melbourne Institute of TAFE (NMIT) was assessed as having low liquidity risk, this rating is based on historical information. NMIT's future projections indicated cash flow deficits for the next two years, meaning that budgeted expenses were expected to be substantially more than expected revenue.

NMIT has identified and commenced the implementation of various operational initiatives to improve its cash flows for 2014. These initiatives include a reduction in staffing levels, increased student fees, ceasing operations at the Greensborough campus, the finalisation of partnering and access arrangements with La Trobe University and Swinburne University respectively, and various other restructuring arrangements.

To assist with its solvency and restructuring arrangements, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) has agreed to support NMIT in securing bridging finance of $16 million.

Notwithstanding DEECD's support for NMIT, our audit opinion on its 2013 financial statements contained an emphasis of matter paragraph. This highlighted the risk that NMIT may be unable to meet expenditure commitments when they fall due, thereby putting at risk its continuation as a going concern.

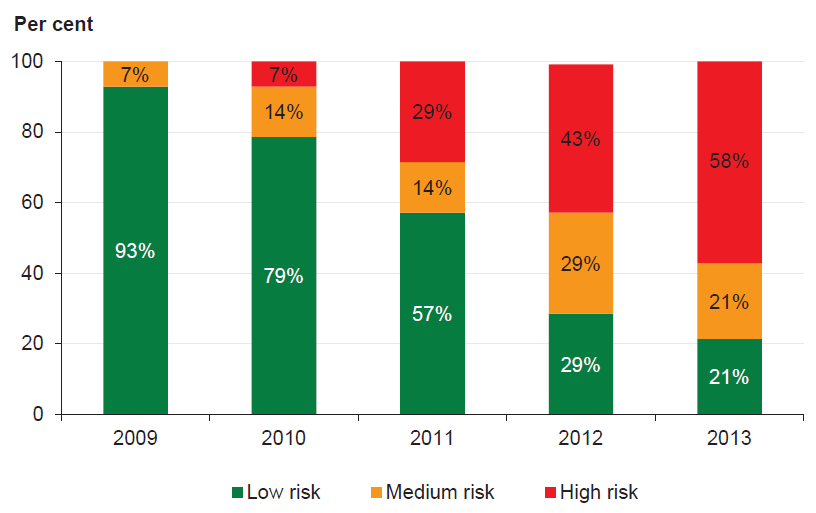

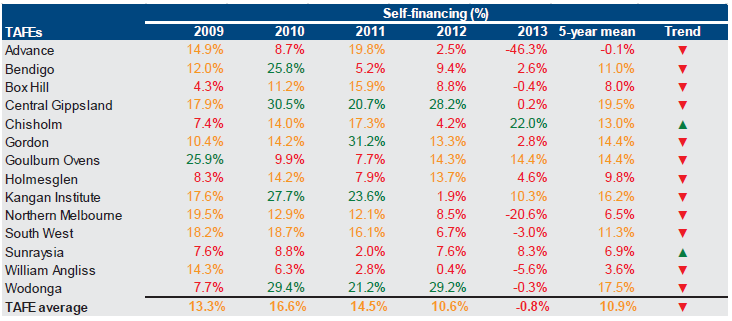

5.3.3 Self-financing

Figure 5C shows the weakening of self-financing indicator results for the TAFE sector over the past five years. TAFE self-financing results have deteriorated since 2009, particularly over the past three years. The average result for the sector decreased from 10.6 per cent in 2012 to negative 0.8 per cent in 2013.

Figure 5C

Self-financing risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The majority of TAFEs (11 of 14) now have a self-financing risk of high, with just one TAFE in the low-risk category. This indicates that where TAFEs have not responded sufficiently to policy changes, and where they require net capital investment in the short term, they are finding it increasingly difficult to generate sufficient cash to fund asset replacement from their operating activities.

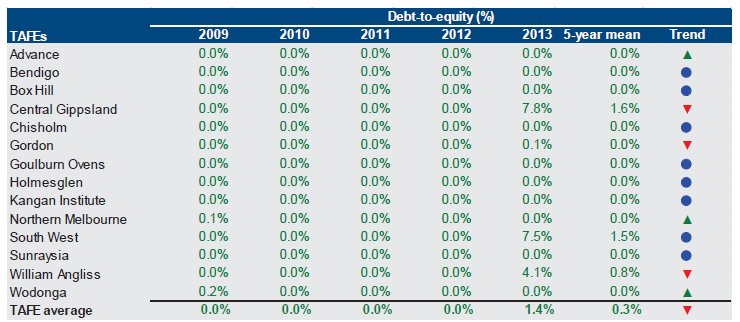

5.3.4 Debt-to-equity

All TAFEs were in the low-risk category for the debt-to-equity ratio for the past five years. Historically, TAFEs have been unable to incur debt. However, more flexible financing arrangements for the sector were approved by the government in 2013 and TAFEs are now able to incur borrowings, subject to approval by the Treasurer.

As at 31 December 2013, 10 TAFEs had no debt at all and more flexible financing arrangements now open to TAFEs provide opportunities. Nevertheless, TAFEs should be cautious and assess their ability to repay associated financing costs, especially if operating results continue to deteriorate.

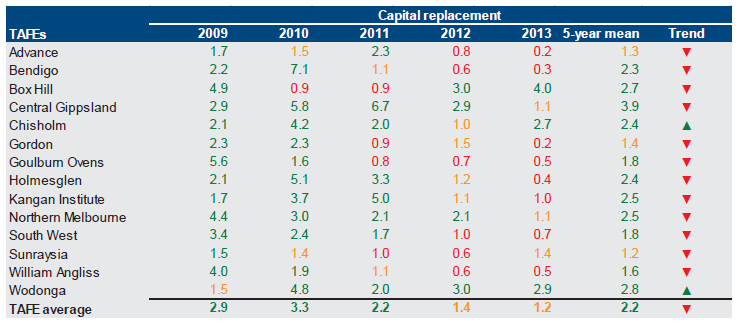

5.3.5 Capital replacement

Figure 5D shows that over the five-year period there has been a substantial decline in the ability of TAFEs to fund asset renewals, specifically highlighting a significant increase in the number of entities in the high-risk category.

Figure 5D

Capital replacement risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In 2013, government capital funding to the TAFE sector decreased by 36 per cent to $37.9 million. The decline in the capital replacement results highlights the dependence of TAFEs on government funding for their capital programs. Nevertheless, TAFEs are now able to fund capital expenditure from their cash reserves, by borrowing, or by the disposal of surplus assets. The data illustrate that spending on capital works is not sufficient to maintain and upgrade existing infrastructure and equipment.

Eleven of the 14 TAFEs (79 per cent) are now in either the medium- or high-risk category for this indicator. If greater investment does not occur, assets will deteriorate at a greater rate than they are replaced or renewed. This presents a risk to the long‑term financial sustainability of TAFEs as their buildings and other infrastructure assets progressively become less functional.

Capital grants have historically been strategically allocated across the sector, with funds for asset replacement not provided until the government considered replacement to be appropriate.

Under the government's competitive neutrality policy, all vocational training providers receive funding based on student contact hours and not for specific types of expenditure such as the depreciation of their assets.