Water Entities: 2015–16 Audit Snapshot

Overview

In this report we detail the matters arising from the 2015–16 financial and performance report audits of the 19 public entities that make up the water sector. We also assess the sector’s financial performance during 2015–16 and its sustainability as at 30 June 2016.

We comment on the key matters that arose during our audits and provide an analysis of information in water entity financial and performance reports. This is one of a set of parliamentary reports on the results of our 2015–16 financial audits.

Four recommendations are made to water entities in the report.

Water Entities: 2015–16 Audit Snapshot: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER November 2016

PP No 224, Session 2014–16

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Water Entities: 2015–16 Audit Snapshot.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

23 November 2016

Audit overview

In this report we detail the matters arising from the 2015–16 financial and performance report audits of the 19 public entities that make up the water sector. We also assess the sector's financial performance during 2015–16 and its sustainability as at 30 June 2016.

We comment on the key matters that arose during our audits and provide an analysis of information in water entity financial and performance reports. This is one of a set of parliamentary reports on the results of our 2015–16 financial audits.

Conclusion

In the year ended 30 June 2016, the water sector generated a net profit before income tax of $716.9 million. We have assessed the sector as being financially sustainable.

Last year, we issued four qualified opinions to the four metropolitan water entities because they had an error in the fair valuation of infrastructure assets. This year, we have removed these qualified opinions because of remedial actions the four metropolitan water entities took to correct the error.

In 2015–16, the water entities carried out a full revaluation of their physical assets. Although the valuation process has improved significantly since the last valuation exercise in 2010–11, water entities need to work on retaining and managing complete and accurate asset data. As well as improving their financial reporting processes, this will provide a good source of information for their asset planning.

Findings

Financial audit outcomes

All 19 water entities received clear audit opinions on their financial and performance reports for the financial year ended 30 June 2016. The Parliament and the Victorian community can have confidence in those reports.

In our financial audits, we reviewed the internal control frameworks of each water entity, and found 73 control weaknesses and/or financial reporting matters that water entities need to address. Water entities have acted to remediate matters raised in previous audits—resolving 70 per cent of such matters in 2015–16.

Financial performance and sustainability

In 2015–16, the water sector generated a net profit before income tax of $716.9 million, mainly due to an increase in regulated prices set by the Essential Services Commission as part of Water Plan 3 and favourable weather conditions leading to more water being used.

Developer contributions continue to grow, increasing by $134.6 million from 2014–15, reflecting the significant and continuing expansion of services in Melbourne's outer suburbs and growth corridors.

Overall, the water sector was in a financially sustainable position at 30 June 2016. When we assessed the sector against seven financial sustainability indicators, it received positive ratings for six of the seven.

Capital replacement remains a moderately rated financial sustainability risk indicator for the sector, particularly for the regional urban cohort. This indicator is likely to deteriorate in future periods as a result of the 2015–16 valuation, which increased the reported value of the sector's assets by $2.4 billion.

Asset valuations

At 30 June 2016, the water sector managed more than $42.3 billion in physical assets. These assets, such as reservoirs, pipes, pump stations and water storage tanks, are significant investments built up over a long time and critical to delivering essential services. We are satisfied that the value of physical assets reported by the sector at 30 June 2016 is materially accurate.

In 2015–16, the water entities carried out a revaluation of their physical assets. This resulted in a $2.4 billion increase in the value of their physical assets. The sector took a much more active role in the 2015–16 valuation exercise than in the equivalent valuation exercise in 2010–11. Although water entities scrutinised valuations more rigorously, problems with the quality of data submitted for valuation reduced the effectiveness of the valuation exercise.

Water entities will be able to use the information they received from the revaluations for more than financial reporting. In particular, the information will help water entities to better maintain assets and plan capital works.

Recommendations

We recommend that water entities:

- promptly address matters raised in this year's and previous audits to prevent their potential reoccurrence and rectify any weaknesses in their control environment to mitigate the risk of their financial statements having material errors (see Part 2)

- review their asset valuation frameworks and incorporate elements of better practice as required (see Part 4)

- continue to review the quality of their asset data, which is integral, not only for financial reporting purposes but for good asset management (see Part 4)

- review the use of indices that managers use when assessing fair value during intervening balance dates—taking into account all relevant internal and external indicators (see Part 4).

Responses to recommendations

We have consulted with all water entities, the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning, the Essential Services Commission and the Valuer-General Victoria throughout the course of the audit. As required by section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report, or relevant extracts, to those agencies and asked for their submissions or comments.

The Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning provided a response for inclusion, stating that it plans to address specific recommendations through water industry forums and the Victorian Water Industry Association.

Its full response is included in Appendix A.

1 Context

1.1 Victoria's water sector

Victoria's water sector is made up of 19 water entities and one controlled entity. The results of the controlled entity are consolidated into its parent entity and we do not discuss them separately. Appendix B includes a list of all 20 entities.

The entities are standalone businesses responsible for their own management and performance. They provide a range of water services, including supplying water and/or sewerage services. Several of the entities also manage bulk water storage and specific recreational areas.

The 19 water entities are split into three operating areas—metropolitan, regional urban and rural. Each water entity is governed by a constituted board with several responsibilities, including to:

- oversee the entity's strategic directions

- set objectives and performance targets

- ensure that the entity complies with legislation and government policy.

The board of each water entity reports to the Minister for Water through the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning. In turn, the minister is responsible for reporting to Parliament on the performance of each water business.

The Water Act 1989 is the central legislation for Victoria's water industry. Its objectives include to:

- promote the orderly, equitable and efficient use of water resources

- ensure that water resources are conserved and properly managed for sustainable use for the benefit of all Victorians

- maximise community involvement in making and implementing arrangements for using, conserving or managing water resources.

In addition to the 19 water entities, Victoria has 10 catchment management authorities, established under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 (Vic). These authorities are responsible for coordinated catchment management in their region. The Water Act 1989 gives them regional waterway, floodplain, drainage and environmental water reserve management powers. The Portfolio Departments and Associated Entities: 2015–16 Audit Snapshot report includes the results for the catchment management authorities.

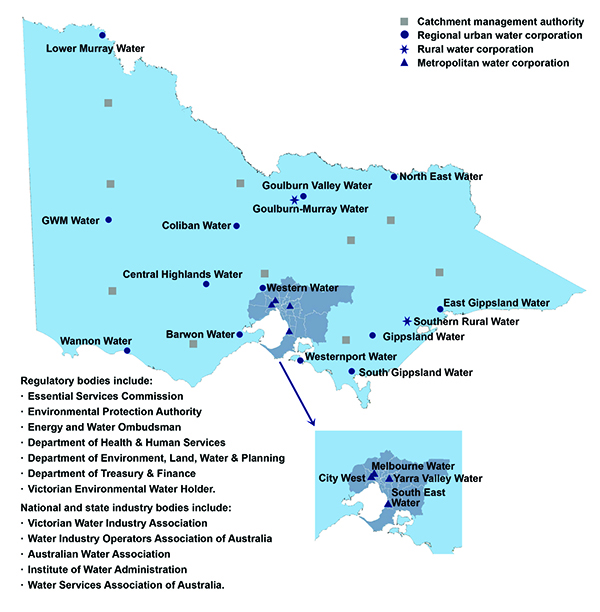

Figure 1A lists several key agencies that regulate the water sector. These agencies are responsible for setting economic, environmental and social obligations within which the water entities must operate. It also highlights some key industry bodies, such as the Victorian Water Industry Association, which has an important advocacy role, providing forums for industry discussions on priority matters and disseminating news and information to key industry stakeholders.

Figure 1A

Victorian water sector

Source: VAGO.

1.2 The regulatory pricing model

Since 1 January 2004, the Essential Services Commission (ESC) has been responsible for regulating and approving the maximum prices each water entity may charge its customers for supplying water and providing sewerage services. The ESC sets prices in accordance with the requirements of the Essential Services Commission Act 2001 (the Act), the Water Industry Act 1994, the Water Industry Regulatory Order and the Commonwealth Water Charge Infrastructure Rules, where applicable.

The ESC has approved prices for metropolitan and regional urban businesses since 1 July 2005 and for rural businesses since 1 July 2006. Its role includes regulating prices and monitoring service standards and market conduct.

The Act states that the ESC's objective is to promote the long-term interests of consumers in the price, quality and reliability of essential services.

To achieve this, the ESC needs to consider:

- regulated entities' efficiency and incentives for long-term investment

- the financial viability of regulated entities

- existing and potential competition in the sector

- relevant health, safety, environmental and social legislation

- the benefits and costs of regulation for consumers—including low-income or vulnerable consumers—and regulated entities

- consistency between state and national regulation.

Taking this into consideration, the ESC has reviewed prices every three-to-five years since 2004. As part of this review, water entities are required to provide the ESC with a water plan. The ESC then determines the maximum prices for each water entity's prescribed goods and services.

The water plan sets out:

- the expected costs of delivering water and sewerage services

- the planned capital works program

- the forecast volumes of water to be delivered

- the level of service provided to customers

- the prices proposed to raise enough revenue to recover expected costs.

ESC determines prices after undertaking an extensive review of the prices proposed by a water entity. These price reviews are iterative in nature and involve significant engagement with key stakeholders.

In October 2012, the 19 water entities submitted water plans for the period from 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2018 to the ESC for assessment. In June 2013, the ESC's released final price determinations for Water Plan 3 covered five years. The 2013 determinations continue to apply to all entities, except for Goulburn-Murray Water and Melbourne Water, which were covered during the three years to 30 June 2016.

Price determination for Melbourne Water and Goulburn-Murray Water

In June 2016, the ESC released its final price determination on Melbourne Water's price submission for the period from 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2021. The determination, driven by lower operating and capital forecasts by Melbourne Water and other cost-saving and efficiency initiatives, has resulted in broad reductions in prices charged to water retailers.

Goulburn-Murray Water also received ESC's final decision on the maximum prices and allowable revenue that Goulburn-Murray Water may charge over the fourth regulatory period, covering the period from 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2020. The determination forecasts a broad reduction in prices for medium and large customers across the service district.

1.3 What we cover in this report

In this report, we detail the outcomes of the 2015–16 financial audits of Victoria's 19 water entities.

We identify and discuss the key matters arising from our audits, and provide an analysis of information included in water entities' financial and performance reports.

Figure 1B

Report structure

Part |

Description |

|---|---|

2: Results of audits |

Comments on the results of the financial and performance report audits and the financial outcomes of the 19 water entities for 2015–16. Discusses our findings from our review of internal control and/or financial reporting matters identified during the 2015–16 financial audits and previous audits. |

3: Financial sustainability |

Provides an insight into the water sector's financial sustainability risks, based on trends in financial sustainability indicators in a five-year period. |

4: Asset valuations |

Comments on the water sector's asset revaluation process in 2015–16. |

The financial audits of the 20 entities included in this report were undertaken under section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and Australian Auditing Standards. The cost of these audits is paid for by each entity. The results of these audits were used in preparing this report. The cost of preparing this report was $210 000, which is funded by Parliament.

2 Results of audits

In this Part we comment on the results of our financial and performance report audits of the state's 19 water entities and the financial outcomes for the sector for 2015–16.

We also comment on the internal control and/or financial reporting matters we found during 2015–16 and provide an update on matters raised in previous audits.

2.1 Conclusion

We issued 19 clear financial and performance report audit opinions for the year ended 30 June 2016, up from 15 for 2014–15.

We found that water entities financial reporting internal controls, to the extent we tested them, were adequate for ensuring financial reporting is reliable.

The sector generated net profits before income tax of $716.9 million in 2015–16, up from $430.6 million in 2014–15, driven by strong results from the state's four metropolitan water entities.

The financial position of the state's water entities remains solid, increasing by $2.2 billion since last year. We can directly attribute this to the increase in the value of water entities' assets.

2.2 Audits for the year ended 30 June 2016

2.2.1 Financial report audit opinions

Independent audit opinions add credibility to financial reports by providing reasonable assurance that the information reported is reliable and accurate. A clear audit opinion confirms that the financial report presents fairly the transactions and balances for the reporting period, in keeping with the requirements of relevant accounting standards and applicable legislation. Water entities received 19 clear audit opinions for the financial year ended 30 June 2016, up from 15 for 2014–15.

We carried out our financial audits of the water entities in keeping with the Australian Auditing Standards.

Following up on 2014–15 qualified audit opinions

In 2014–15, the four metropolitan water entities received qualified audit opinions on their financial and performance reports. Auditors issue a qualified audit opinion when they are not satisfied that a financial report is free from material misstatement.

The reports received qualified opinions because they had an error in the fair valuation of infrastructure assets.

All four metropolitan water entities had inappropriately accounted for deferred tax benefits in their fair value calculations. Also, Melbourne Water had inappropriately accounted for developer contributions in its fair value calculation. These errors were a departure from Australian Accounting Standard AASB 13 Fair Value Measurement.

In 2015–16, the metropolitan water entities collectively hired a valuation expert to prepare a new way to value infrastructure assets. The new valuation method resolved and corrected the error identified in 2014–15 and was adequately disclosed in each of the entities' financial statements. The metropolitan entities' action resulted in the qualification being removed this year.

2.2.2 Performance report audit opinions

Financial Reporting Direction (FRD) 27C Presentation and Reporting of Performance Information, issued in May 2015, required all 19 water entities to, each year, prepare and have audited a report on their performance during the financial year.

An updated Ministerial Reporting Direction 01 (MRD01) Performance Reporting was issued on 18 May 2016 under section 51 of the Financial Management Act 1994. MRD01 supports the requirement under FRD 27C and specifies the format, content, and key performance indicators that the 19 water entities must include in their performance reports.

We issued clear audit opinions on all 19 performance reports.

A clear audit opinion confirms that the actual results reported on the performance report were fairly presented and complied with legislative requirements.

We do not form an opinion on the relevance or appropriateness of the reported performance indicators, because they are set by Ministerial Direction. We carried out the audits in keeping with the Australian Auditing Standards.

2.3 Sector financial results

We measure an entity's financial performance by its net operating result—the difference between its revenues and expenses. We measure an entity's financial position by looking at the difference between its total assets and total liabilities.

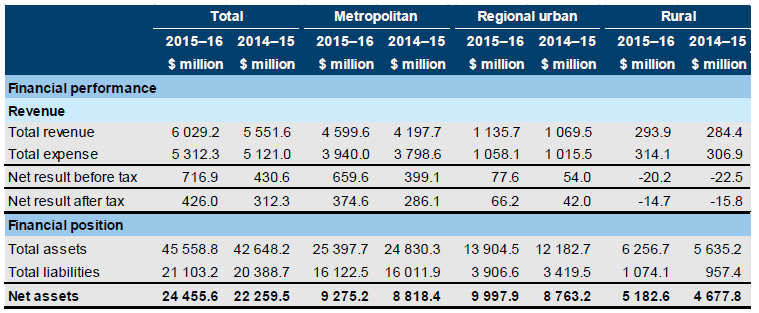

Figure 2A provides an overview of the financial performance and position of Victoria's water sector for 2015–16 and 2014–15, by metropolitan, regional urban and rural cohort.

The metropolitan water cohort—the metropolitan wholesaler and three metropolitan retail water entities—contributes much of the sector's transactions and balances.

Figure 2A

Financial overview of the water sector, 2014–15 and 2015–16

Note: The 2014–15 comparatives have been restated for the metropolitan water entities.

Source: VAGO.

The 19 water entities generated a combined net profit before income tax of $716.9 million for 2015–16, an increase of $286.3 million, or 66.5 per cent, on 2014–15. This was largely due to the metropolitan water entities generating $659.6 million of this net profit before income tax—a collective $260.5 million increase on the year before.

Revenue

In 2015–16, the 19 entities generated revenue of $6.0 billion, an increase of $477.6 million, or 8.6 per cent, on 2014–15.

Service and usage charges increased by $211.0 million, or 6.6 per cent, as a result of price increases set by the Essential Services Commission as part of Water Plan 3 and more water being used. The three metropolitan water retailers, which together service most of the state's population, had the greatest growth in service and usage charges—$171.8 million, or 8.2 per cent.

Developer contributions increased by $134.7 million, or 36.6 per cent, from 2014–15, reflecting the significant and continued expansion of services in Melbourne's outer suburbs and growth corridors.

Expenses

In 2015–16, the 19 water entities incurred $5.3 billion in total expenditure, an increase of $191.3 million, or 3.7 per cent, from 2014–15, mainly due to metropolitan water retailers paying higher bulk water and sewerage charges.

Dividends

The 19 entities are obliged to pay a dividend to the state if the Treasurer makes a formal determination that they have to. In the past, only the metropolitan water entities have been required to pay a dividend, because of the strong operating results generated.

Dividends are generally paid twice a year, based on a prescribed percentage of the net profit before tax:

- an interim dividend determined in April based on half-year financial results

- a final dividend determined in October based on annual financial results.

In 2015–16, the three metropolitan retailers paid dividends of $60.1 million—a decrease of $60.7 million or 50.2 per cent, on 2014–15. However, this was offset by the Treasurer asking the metropolitan water entities to return $56.1 million in capital contributions.

2.3.1 Financial position

Assets and liabilities

At 30 June 2016, the 19 water entities controlled $45.6 billion in assets, an increase of $2.9 billion, or 6.8 per cent, on June 2015. This was due to a net $2.4 billion revaluation increase to land, buildings and infrastructure assets. We discuss this further in Part 4.

At 30 June 2016, the water sector had combined liabilities of $21.1 billion, an increase of $714.5 million, or 3.5 per cent, on 2015. This was mainly a result of net deferred tax liabilities increasing by $694.0 million—a direct result of the water entities' asset valuation.

2.4 General internal controls and financial reporting

Effective internal controls help entities to meet their objectives reliably and cost-effectively. Strong internal controls are a prerequisite for delivering reliable, accurate and timely external and internal financial reports.

In our annual financial audits, we consider the internal controls relevant to financial reporting and assess whether entities have managed the risk that their financial reports will not be complete and accurate. Poor internal controls make it more difficult for managers to comply with relevant legislation and increase the risk of fraud and error.

The board of each water entity is responsible for setting up and maintaining internal controls that help to:

- prepare and maintain accurate financial records

- report promptly and reliably, externally and internally

- appropriately safeguard assets

- prevent and detect errors and other irregularities.

The Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance require managers to build effective internal control structures. In this section, we discuss:

- internal control weaknesses or financial reporting problems common in the 19 water entities in 2015–16

- the status of control weaknesses or financial reporting problems identified in audits in previous years.

2.4.1 Common internal control weaknesses and financial reporting problems

During our financial audits, we found that water entities' financial reporting internal controls, to the extent we tested them, were adequate for ensuring that financial reporting is reliable. However, we found some instances where important internal controls need to be strengthened or financial reporting matters need to be addressed.

During 2015–16, our audit teams identified 73 internal control weaknesses or financial reporting issues, which were reported to managers and their respective audit committees. Figure 2B shows the number of issues identified, by risk rating. We exclude 40 low-risk issues, most of which are minor control weaknesses or opportunities to improve existing processes or internal controls.

We define each risk rating in Appendix C.

Figure 2B

Reported issues by area and risk rating, 2015–16

Area of issue |

Risk rating of issue |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Extreme |

High |

Medium |

Total |

|

Information technology |

- |

3 |

8 |

11 |

Infrastructure assets, property, plant and equipment |

- |

4 |

9 |

13 |

Expenses and payables |

- |

- |

5 |

5 |

Revenue and receivables |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

Employee benefits |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

Other |

- |

1 |

1 |

2 |

Total |

- |

8 |

25 |

33 |

Percentage |

0% |

24% |

76% |

100% |

Source: VAGO.

Monitoring, maintaining and accounting for fixed assets

In 2015–16, the 19 water entities controlled more than $42.3 billion of physical assets. The entities need to appropriately record and maintain these assets and monitor their condition and use so that decisions can be made about whether they are appropriately valued and when they need to be replaced.

Common matters we found were:

- the untimely capitalisation of work in progress

- failing to adequately assess and review useful lives of assets

- a need to improve documents used to create and dispose of assets

- a need to improve the way managers oversee the valuation process.

Part 4 provides further details on problems encountered during the fair valuation exercise carried out on the water sector's physical assets.

Information technology

Information technology (IT) controls protect computer applications, infrastructure and information assets from many threats to security and access. Such controls:

- promote business continuity

- minimise business risk

- reduce the risk of fraud and error

- help meet business objectives.

Water entities rely extensively on IT and continually upgrade and replace systems to better manage information and the quality of services the community receives. Even with new IT and upgrading existing systems, the continuing emergence of external threats means that new security risks to the IT environment arise regularly.

In the Financial Systems Controls Report: 2015–16, tabled in November 2016, we noted that, as in 2015, cross-government matters raised in water sector management letters during 2015–16 were mostly about managing users' access and authentication controls.

2.4.2 Status of matters raised in previous audits

Managers and their respective audit committees receive information about the status of internal control weaknesses or financial reporting problems found in previous audits through management letters. We monitor these weaknesses and problems to ensure that entities act to promptly resolve them.

Figure 2C shows the internal control weaknesses and financial reporting issues raised in previous audits, with the resolution status by risk.

Figure 2C

Matters raised in previous audits—resolution status by risk

| Status of prior period issues | Risk rating of issue |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Extreme |

High |

Medium |

Total |

|

Unresolved issues |

- |

4 |

15 |

19 |

Resolved issues |

4 |

10 |

32 |

46 |

Total |

4 |

14 |

47 |

65 |

Note: Figure 2C excludes low-risk matters raised.

Source: VAGO.

Sixty-five issues remained open at the start of 2015–16. Encouragingly, 70 per cent of these matters were resolved during 2015–16.

However, four high-risk and 15 medium-risk problems raised in previous years remain unresolved. The failure to resolve these problems reduces the effectiveness of the internal control environment. This could lead to water entities being unable to achieve their process objectives, comply with relevant legislation or identify material misstatements. Appendix C includes information about time lines for resolution.

3 Financial sustainability

In this Part, we provide an insight into the 19 water entities' financial sustainability using a suite of commonly used financial indicators.

To be financially sustainable, entities need to be able to fund their current and future spending. They also need to be able to absorb the financial effects of changes and financial risks, without significantly changing their revenue and expenditure policies.

We should view financial sustainability from both short- and long-term perspectives. Short-term indicators provide information about how well an entity can keep positive operating cash flows or generate an operating surplus over the short term. Long-term indicators focus on an entity's ability to fund significant asset replacement or reduce long-term debt.

Below, we discuss current challenges to the financial sustainability of the water sector and trends over a five-year period. We use the financial transactions and balances of each entity's statutory financial report to calculate the values of indicators.

To do this, we assess whether water entities generate enough surpluses from operations to maintain services, maintain or renew assets and repay debt. Their ability to do so is subject to the regulatory environment in which they operate and their ability to minimise costs and maximise revenue.

3.1 Conclusion

For the year ended 30 June 2016, we have assessed the water sector's financial performance and position as being financially sustainable.

3.2 Challenges to financial sustainability

3.2.1 Financial sustainability

The indicators highlight potential risks to ongoing financial sustainability in either the short or longer term. However, forming a definitive view of any entity's financial sustainability requires an analysis that moves beyond historical financial considerations to include the entity's financial forecasts, strategic plans, operations and environment, including the regulatory environment.

We use seven financial sustainability risk indicators measured over a five-year period to assess the financial sustainability risks to the water sector. Appendix D describes the financial sustainability indicators, risk assessment criteria and benchmarks we use.

3.2.2 Overall assessment

Figure 3A provides a snapshot of the seven financial sustainability indicators, by cohort, against the sector average for the past five years.

Figure 3A

The water sector's financial sustainability

| Indicator | Sector average |

Sector average |

Metropolitan average |

Regional urban average |

Rural average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2011–12 to 2015–16 |

2015–16 |

2015–16 |

2015–16 |

2015–16 |

|

Net result |

1.32% |

3.84% |

7.98% |

4.38% |

-8.00% |

Interest Cover Ratio |

6.97 |

6.13 |

2.40 |

7.17 |

6.85 |

Liquidity Ratio |

0.90 |

1.03 |

0.63 |

1.09 |

1.42 |

Internal Financing |

69.13% |

94.14% |

74.25% |

110.83% |

25.41% |

Capital Replacement Ratio |

1.48 |

1.31 |

1.79 |

1.14 |

1.52 |

Debt to Assets |

0.19 |

0.19 |

0.47 |

0.13 |

0.02 |

Debt Service Cover |

4.90 |

3.69 |

2.79 |

3.76 |

7.29 |

Source: VAGO.

The results for 2015–16 indicate a low risk to financial sustainability. However, the cohorts face specific challenges:

- the metropolitan cohort reported a relatively higher liquidity risk

- the regional urban cohort reported a medium-risk capital replacement outcome

- the rural cohort reported medium-risk net result and internal financing outcomes for the period.

3.2.3 Short-term indicators

The short-term indicators—net result, interest cost and liquidity—focus on a water entity's ability to maintain positive operating cash flows and adequate cash holdings and to generate an operating surplus over the short term.

The water sector has shown an improvement in performance, reducing the risk of financial issues in the short term. However, some entities had continued to report losses from operations or poor liquidity results. We explore these factors in more detail below.

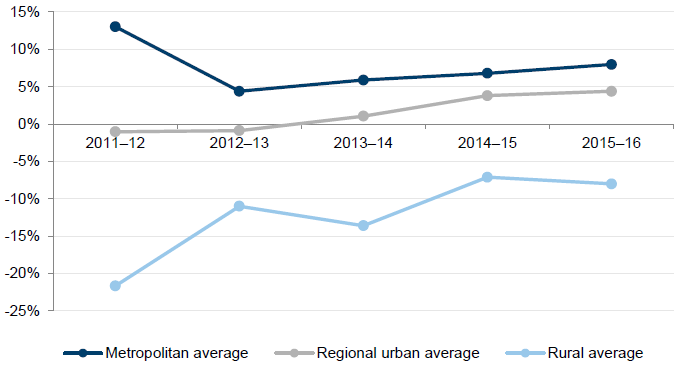

Net result

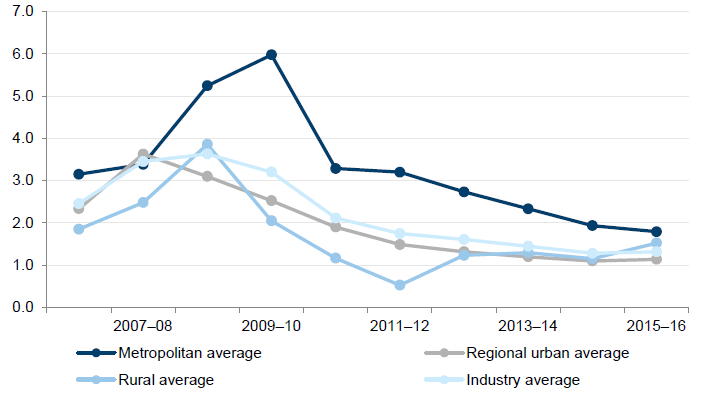

Figure 3B illustrates the average net result indicator by cohort for a five-year period.

Figure 3B

Average net result indicator, 2011–12 to 2015–16

Source: VAGO.

Water entities operate under a regulated pricing model that prevents the full amount of depreciation, as reported in their financial statements, being recovered through prices charged to customers. This is an ongoing problem for regional urban and rural entities because the regulatory asset values used to determine prices are much lower than the statutory asset values.

Liquidity

We assess an entity's overall liquidity position using all available information, including corporate plans, cash-flow projections, liquidity strategies and financial ratios.

The 2015–16 sector average liquidity ratio is above 1.0 and is above the five-year average.

Although the regional urban and rural water entities reported positive liquidity ratios, the metropolitan cohort reported an average liquidity ratio of less than 1.0. This outcome reflects the financial and debt management strategies, such as using excess cash to reduce outstanding debt, or the way the entity classifies the debt in keeping with Australian Accounting Standards.

3.2.4 Long-term indicators

Long-term indicators—internal financing, capital replacement, debt to asset and debt service cover—show whether revenue is enough to:

- replace assets to maintain the quality of service delivery, to meet community expectations and the demand for services

- repay debt in the longer term.

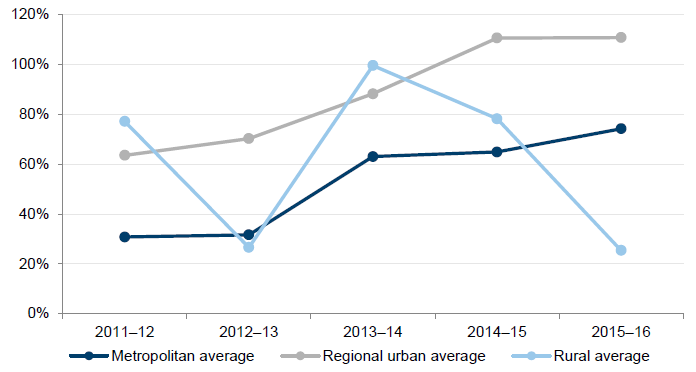

Internal financing ratio

Figure 3C shows that, over the past five years, metropolitan and regional urban water entities have become better able to finance capital investment using cash flows from operations.

Figure 3C

Average internal financing indicator for water entities, 2011–12 to 2015–16

Source: VAGO.

The fluctuating trend for the rural cohort is driven by the timing of state and Commonwealth funding received by Goulburn-Murray Water for the Connections Project and when this funding is used. The Connections Project is aimed at generating water savings and securing the future of irrigated agriculture in the Goulburn Murray Irrigation District through modernising the irrigation network.

Capital replacement indicator

The capital replacement indicator shows whether water entities spend more on replacing or renewing assets each year compared to their depreciation expense.

Figure 3D shows a downward trend for the average capital replacement indicator across the industry over 10 years. Noticeable peaks in 2008–09 and 2009–10 relate to:

- significant expenditure outlays for the Food Bowl Modernisation Program at Goulburn-Murray Water, now referred to as the Connections Project

- the change from cost to fair-value measurement of the metropolitan water entities' infrastructure assets—causing the depreciation expense to increase significantly in 2010–11 as a result of the higher asset values.

Figure 3D shows that the water entities struggle to sustain capital spending for renewing or replacing assets at the rate of depreciation.

Figure 3D

Average capital replacement indicator for water entities, 2006–07 to 2015–16

Source: VAGO.

The timing and extent of an entity's capital works program affects the outcome of this indicator. Entities need to balance their operational and capital cost savings and their capital works programs, because delays and reductions to capital works programs might have longer-term effects on core service delivery. Good asset data can help water entities in finding the right balance of capital spend. We discuss this in more detail in Part 4 of this report.

This indicator is likely to deteriorate, after the formal asset valuation exercise in 2015–16, which increased the estimated value of the sector's infrastructure, property, plant and equipment assets by $2.4 billion, or 5.8 per cent. The growth in the fair value of entity assets increases the annual depreciation charge. Therefore, we expect greater depreciation in 2016–17 and after.

We cannot view the capital replacement ratio in isolation. We need to take a longer-term view when assessing whether entities are investing enough in replacing capital. Entities with long-lived infrastructure assets require comprehensive asset renewal strategies to support the long-term replacement of core service delivery assets. The actual yearly capital expenditure fluctuates from year to year and can distort the capital replacement ratio.

4 Asset valuations

The state has invested significantly in water infrastructure assets to deliver essential water services to the community. In 2015–16, 19 water entities controlled more than $42.3 billion of the state's $226.6 billion in physical assets. These assets are measured at fair value in accordance with Australian Accounting Standards and government financial reporting directives.

Up-to-date and accurate valuations of these assets enable an entity to correctly account for the future economic benefits the assets embody. The valuations also give entities relevant and reliable information when deciding how to allocate resources, measuring performance and accounting for assets.

In this Part, we look at the fair valuation exercise the 19 water entities carried out for the year ended 30 June 2016.

4.1 Conclusion

The asset valuation process in 2015–16 was much more effective than the previous valuation process in 2010–11. Key stakeholders' acting early and effectively, and managers' better scrutinising valuation reports led to the improvement.

However, water entities should further improve the quality of their asset data.

4.2 Asset valuations in the water sector

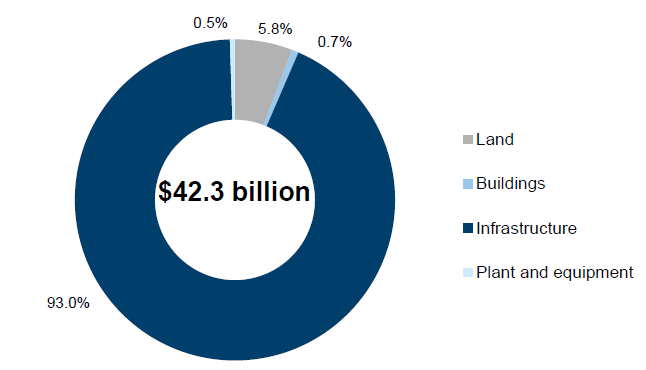

In 2015–16, the 19 water entities managed more than $42.3 billion in physical assets. These assets include land, buildings and water infrastructure—reservoirs, pipes, pump stations and water storage tanks. Figure 4A shows the composition of the physical assets the water entities manage.

Figure 4A

The types of physical asset the water entities manage

Note: Excludes work-in-progress which is measured at cost.

Source: VAGO.

Most—a total of $39.3 billion worth—of the physical assets the state's water entities manage are infrastructure assets. Of this, the state's four metropolitan water entities, which collectively service most Victorians, manage $21.2 billion.

4.2.1 Accounting and financial reporting framework

The Australian Accounting Standards Board sets the financial reporting standards for all reporting entities in Australia. Specifically, Australian Accounting Standards Board 116 Property Plant and Equipment prescribes how to measure physical assets at either cost or fair valuation. The Financial Reporting Direction 103F Non-Financial Physical Assets requires water entities to measure their physical assets at fair value. The Direction also requires a formal valuation every five years, with managers to make fair-value assessments at the end of each intervening financial reporting period. These fair-value assessments take into account all fair-value indicators, which include the use of Valuer-General of Victoria (VGV) indices and/or other relevant indicators. If a fair-value assessment indicates a movement of more than 10 per cent for an asset class, the Direction require managers to perform a managerial valuation.

Building indices

In 2014–15, managers at seven water entities revalued their buildings because a fair-value assessment of their carrying values identified a change of more than 10 per cent. However, in 2015–16, four of those entities recorded valuation decreases arising from formal valuation by the VGV.

Although these water entities acted in keeping with the Direction, the interim valuation did not consider internal specialist knowledge of buildings, particularly of their condition.

Infrastructure assets indices

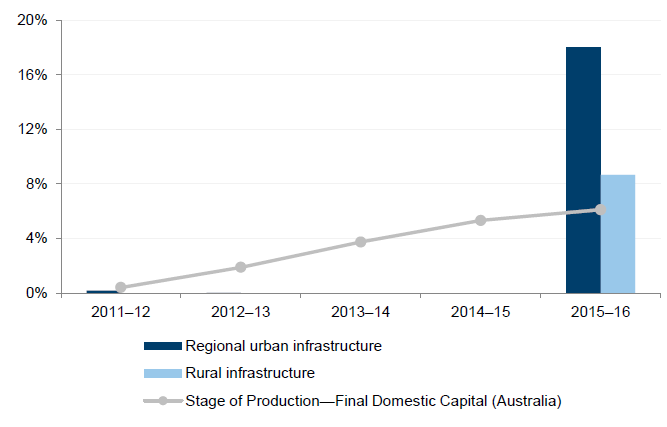

In 2013, the water sector hired a consultant to help identify a suitable index or set of indices that the sector could use to carry out a fair-value assessment during the intervening periods, as the financial reporting direction requires. The consultant concluded that the Australian Bureau of Statistics' Stage of Production—Final Domestic Capital (Australia) index was an appropriate single overall index.

No single index accurately accounts for all of the water sector's infrastructure assets, because each water entity is different and operates independently in unique geographic conditions. Figure 4B shows this case for regional urban and rural water entities.

Figure 4B

Maximum movement against revaluation reserve

Source: VAGO.

From 2011–12 to 2015–16, the compounded increase in the Stage of Production—Final Domestic Capital (Australia) index was 6 per cent—below the 10 per cent threshold that would trigger a managerial valuation. However, as a result of the formal valuation exercise, the sector recorded valuation increases in excess of the indices—18 per cent for regional urban infrastructure assets and 9 per cent for rural infrastructure assets.

4.2.2 Developments since the 2010–11 valuation

In 2011, a formal valuation of all Victorian water entities was carried out. The results of the valuation were recognised in the water entities financial statements of 30 June 2011. There were significant problems with the appropriateness of valuation techniques and data quality assurance processes over water entities' assets as they moved from a cost to fair-value model. In our report Water Entities: Results of the 2010–11 Audits, we recommended that water entities work with relevant government stakeholders to work out the most appropriate valuation methodology for infrastructure assets.

In response to our recommendations, the water industry, led by VicWater, formed a working group consisting of representatives from the water entities, VGV, the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning and the Department of Treasury & Finance. The group's objectives were to plan and manage the 2015–16 revaluation process and to work early with key stakeholders to address emerging matters and prevent similar problems arising as were experienced in the 2010–11 revaluation process.

In January 2016, VicWater published an infrastructure asset valuation guidance paper for water entities to use when carrying out asset revaluations. The main objective of the guidance paper was to encourage more consistent practice by outlining commonly accepted processes and procedures.

4.2.3 The 2015–16 valuation

The 2015–16 valuation process led to a $2.4 billion increase in the reported value of assets held by the 19 water entities. Figure 4C shows the movements in the major asset classes.

Figure 4C

Net revaluation increases as a result of the 2015–16 valuation process,

by class

Component |

Increase / (decrease) $ million |

Increase / (decrease) Per cent |

|---|---|---|

Land |

199.5 |

11.3 |

Buildings |

(10.0) |

(4.2) |

Infrastructure assets |

2 227.6 |

12.9 |

Total |

2 417.1 |

6.2 |

Source: VAGO.

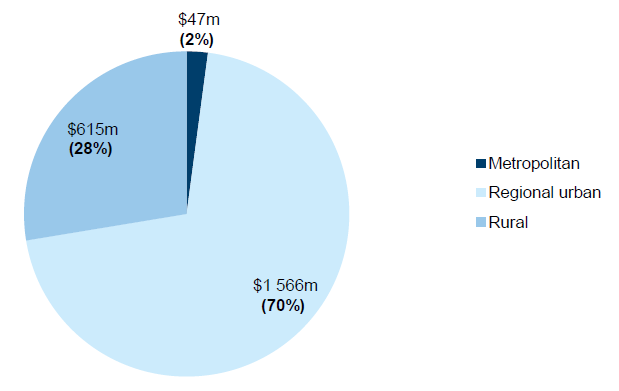

Figure 4D shows the breakdown by sector cohort.

Figure 4D

Changes in fair value of infrastructure as a result

of the 2015–16 revaluation process, by cohort

Source: VAGO.

Regional and rural water entities account for 98 per cent of the valuation increases in the water sector. This is because these entities determine the fair value of their infrastructure assets based on the cost of replacing the asset adjusted for accumulated depreciation. This is known as depreciated replacement cost and is applied to 'not-for-profit' water entities.

On the other hand, the state's metropolitan water entities, which are 'for-profit' businesses, use an income approach to determine fair value—a discounted cash-flow method that requires the determination of an appropriate discount rate and the projection of future cash flows. Every year, an independent valuer helps the metropolitan water corporations to carry out valuations. Because valuations happen regularly, carrying value approximates fair value and changes in fair value are smaller.

Valuing physical assets is highly complex and requires significant judgement, using an external valuation expert, and making some key assumptions underpinning how to determine fair value.

4.2.4 The Valuer-General of Victoria

VGV is the state's independent authority on government asset valuations. It plays a pivotal role in valuing the water sector's non-financial physical assets and is responsible for providing and overseeing valuation services to the state's 19 water entities. VGV does this work using in-house or contractually engaged valuers.

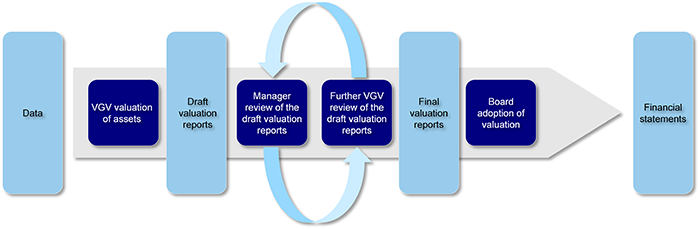

Figure 4E outlines the asset valuation process.

Figure 4E

Valuation process

Source: VAGO.

4.2.5 Asset valuation framework

Water entities should have an effective asset valuation framework in place to guide, oversee and manage the valuation process. Although managers are responsible for asset revaluations, boards are responsible for adopting the financial report and the final valuations, in line with managers' recommendations.

In Appendix E, we outline the key elements of this framework.

Figure 4F outlines Barwon Water's asset revaluation governance arrangements.

Figure 4F

Barwon Water

Barwon Water is Victoria's largest regional urban water corporation. It provides water and sewerage services to more than 298 700 permanent customers over 8 100 square kilometres. Barwon Water owns and operates $2.6 billion in assets and, along with the other 18 water entities, was required to carry out a formal valuation of its physical assets. A successful valuation process needs strong governance and reporting, early engagement of key stakeholders and a comprehensive timetable. Barwon Water began its valuation process after considering the draft VicWater valuation guidelines. It prepared a detailed valuation timetable outlining the tasks to be completed, asset components to be valued and quality assurance processes required. The timetable called for regular meetings between key internal and external stakeholders, providing a greater understanding of the role each played in the valuation exercise. As part of the governance framework, Barwon Water updated its asset revaluation policy. This comprehensive policy contained three key features:

Managers carried out a significant validation exercise before giving data to the VGV. Barwon Water's senior engineers worked with external consultants to assess assets using Barwon Water's condition categories. A detailed reconciliation between the asset management system and draft report provided more confidence in data quality. Barwon Water's Board reporting was comprehensive, with initial reports analysing the different valuation methods available. Subsequent reports to the audit committee included a management review of data integrity and an updated revaluation policy. The Board formally adopted the audit committee endorsed valuation at its August 2016 meeting. |

Source: VAGO.

Quality of data submitted to valuers

Water entities are responsible for the completeness and accuracy of underlying asset data provided to the VGV for the valuation. Poor asset data reduces the integrity and quality of the valuations and reduces water entities' ability to effectively monitor, evaluate and report asset performance. Setting up and embedding systems and practices that improve data usability and information quality is an important aspect of the revaluation exercise. A lack of data quality assurance processes can delay the exercise, increase costs and cause incorrect valuations.

Common problems the VGV faces include:

- submitted data being of inconsistent quality

- insufficient information, such as asset identifiers or locations of assets

- data being unsuitable for the valuation exercise.

Figure 4G shows how embedding quality assurance processes from the ground up resulted in a smoother valuation process for Coliban Water.

Figure 4G

Coliban Water

In 2014–15, Coliban Water completed an asset management improvement project which involved reviewing the composition of their infrastructure assets. The review also included assessing condition and useful lives of all above ground infrastructure assets and the introduction of decision models for below-ground infrastructure assets, such as pipes. The Board drove the project to help the corporation to meet its financial objectives—to cap its debt obligations, repay existing debt and use remaining cash for capital works. Therefore, it needed a sound understanding of its asset base, particularly its asset renewal profile—a challenge for regional water corporations. The asset management improvement project aimed to achieve consistency between asset data and financial information. This has allowed Coliban Water to align asset management decision-making with its fixed asset register, so establishing a single 'source of truth' for strategic, operational and financial decision-making and reporting. A third-party service provider also worked on the project, which included inspecting in detail infrastructure assets, condition assessments and asset valuations. This resulted in more components within individual infrastructure assets based on more reliable information, allowing managers to better assess and judge depreciation and written-down values. These changes helped Coliban Water to better decide how to spend money on assets. The work allowed Coliban Water to carry out the 2015–16 revaluation with a better understanding of its assets and their condition. Coliban Water had consulted early with the VGV about the information needed for the valuation, the detail required and the consistency of the condition assessments. Before submitting its asset data to VGV, Coliban Water ran an extensive quality assurance program looking at the data. Armed with a better understanding of its assets from the asset management project, Coliban Water was able to question the draft valuation with more rigour, querying not only material increases and decreases but unexpected changes in asset values. Coliban Water's review of the draft valuation included:

|

Source: VAGO.

4.3 Quality assurance over draft valuation reports

At the end of the valuation exercise, VGV gives the water entities a draft valuation report to consider and review. The water entities play an important role in assuring the quality of the report—they must be confident that the revalued assets are appropriate for statutory reporting purposes.

Figure 4H shows the differences between the fair values in the draft valuation reports submitted to the water entities for consideration and the valuations in the audited financial report.

Figure 4H

Fair values of assets in draft valuation reports and audited financial reports

Asset class |

Draft valuation $ million |

Final valuation $ million |

Difference $ million |

|---|---|---|---|

Land |

2 728.0 |

2 447.7 |

280.3 |

Buildings |

264.3 |

285.9 |

–21.6 |

Infrastructure assets* |

20 673.2 |

18 120.0 |

–2 553.2 |

Note: The values do not take into account the fair valuation of infrastructure assets for the four metropolitan water entities, which use the income approach and are not valued by the VGV.

Source: VAGO.

The differences between the draft valuation and the final valuation underline the importance of having good processes to assure quality and a collaborative approach between the valuers and the water entities to get a materially accurate and complete valuation of assets for statutory financial reporting.

Common problems identified were:

- the use of average unit construction costs against actual construction costs derived from recent contracts entered into by a water entity

- discrepancies in the valuer's assessment of conditions of assets compared with the water entity's assessment based on evidence of asset condition

- applying useful lives on perpetual assets

- the depth of detail of the data

- the water entity supplying additional information or evidence that was not originally asked for as part of the data-gathering exercise.

The most significant change between the draft valuations and the final valuations was in infrastructure assets. These assets underpin the core service delivery for water entities and by its nature are highly specialised, complex and, in some instances, are underground and not readily visible. Water entities know more about the intricacies of their infrastructure assets, including elements such as condition, recent contract construction prices and environmental factors that an independent valuer would otherwise not have. Therefore, it highlights the importance for water entities to adequately maintain quality asset data for this quality assurance process to be effective and for the VGV to consider when valuing such assets.

Appendix A. Audit Act 1994 section 16—submissions and comments

We have consulted with all water entities, the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning, the Essential Services Commission and the Valuer-General Victoria throughout the course of the audit. As required by section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report, or relevant extracts, to those agencies and asked for their submissions or comments.

Responsibility for the accuracy, fairness and balance of those comments rests solely with the agency head.

The full response from the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning is provided overleaf.

RESPONSE received from the Secretary, Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning

Appendix B. Water entities

Figure B1 lists the legal and trading names of the 20 entities including one controlled entity that form part of the Victorian water industry.

Figure B1

Water entities and controlled entity

Legal name |

Trading name |

|---|---|

Metropolitan cohort |

|

Wholesaler | |

Melbourne Water Corporation |

Melbourne Water |

Retailers | |

City West Water Corporation | City West Water |

South East Water Corporation | South East Water |

Yarra Valley Water Corporation | Yarra Valley Water |

iota Services Pty Ltd (subsidiary of South East Water Corporation) |

iota |

Regional urban cohort |

|

Barwon Region Water Corporation |

Barwon Water |

Central Gippsland Region Water Corporation |

Gippsland Water |

Central Highlands Region Water Corporation |

Central Highlands Water |

Coliban Region Water Corporation |

Coliban Water |

East Gippsland Region Water Corporation |

East Gippsland Water |

Goulburn Valley Region Water Corporation |

Goulburn Valley Water |

Grampians Wimmera Mallee Water Corporation |

GWMWater |

Lower Murray Urban and Rural Water Corporation |

Lower Murray Water |

North East Region Water Corporation |

North East Water |

South Gippsland Region Water Corporation |

South Gippsland Water |

Wannon Region Water Corporation |

Wannon Water |

Western Region Water Corporation |

Western Water |

Westernport Region Water Corporation |

Westernport Water |

Rural cohort |

|

Gippsland and Southern Rural Water Corporation |

Southern Rural Water |

Goulburn-Murray Rural Water Corporation |

Goulburn-Murray Water |

Source: VAGO.

Controlled entity

iota Services Pty Ltd

iota Services Pty Ltd (iota) is a wholly-owned subsidiary of South East Water, incorporated on 29 October 2014 under the Corporations Act 2001 and it commenced trading on 1 January 2015. The then Minister for Water approved the establishment of iota under the provisions of the Water Act 1989.

iota is responsible for the profitable commercialisation of South East Water's innovations, products and services.

The entity is consolidated into the financial report of South East Water, as per the requirements of AASB 10 Consolidated Financial Statements. As the entity is consolidated, the results of that audit are addressed throughout this report as part of the South East Water results.

For the 2015–16 reporting period, a financial report was prepared and audited, where an unqualified audit opinion was issued.

Appendix C. Management letter risk ratings

Figure C1 shows the risk ratings applied to management letter points raised during an audit.

Figure C1

Risk definitions applied to issues reported in audit management letters

Rating |

Definition |

Management action required |

|---|---|---|

Extreme |

The issue represents:

|

Requires immediate management intervention with a detailed action plan to be implemented within one month. Requires executive management to correct the material misstatement in the financial report as a matter of urgency to avoid a modified audit opinion. |

High |

The issue represents:

|

Requires prompt management intervention with a detailed action plan implemented within two months. Requires executive management to correct the material misstatement in the financial report to avoid a modified audit opinion. |

Medium |

The issue represents:

|

Requires management intervention with a detailed action plan implemented within three to six months. |

Low |

The issue represents:

|

Requires management intervention with a detailed action plan implemented within six to 12 months. |

Source: VAGO.

Appendix D. Financial sustainability risk indicators

This Appendix sets out the definitions and criterion applied in this report from prior years that assist us in conducting our assessment of risks to financial sustainability across the water sector.

The financial sustainability indicators used in this report are indicative and highlight risks to ongoing financial sustainability at a sector and cohort level—metropolitan, regional urban and rural.

It is important to note that forming a definitive view of financial sustainability requires a holistic analysis that moves beyond historical financial considerations to also include consideration of financial forecasts and plans, operations and an entity's environment, particularly the regulatory environment within which these water entities operate.

Figure D1 shows the indicators used in assessing the financial sustainability risks of entities covered by this report. These indicators should be considered collectively, and are more useful when assessed over time as part of a trend analysis.

Figure D1

Financial sustainability risk assessment indicators

Indicator |

Formula |

Description |

|---|---|---|

Net result (%) |

Net result / Total revenue |

A positive result indicates a surplus, and the larger the percentage, the stronger the result. A negative result indicates a deficit. Operating deficits cannot be sustained in the long term. Net result and total revenue are obtained from the comprehensive operating statement. |

Liquidity (ratio) |

Current assets / Current liabilities |

This measures the ability of an entity to pay existing liabilities in the next 12 months. A ratio of one or more means there are more cash and liquid assets than short-term liabilities. Current assets and current liabilities are obtained from the balance sheet. |

Internal financing (%) |

Net operating cash flow / Net capital expenditure |

This measures the ability of an entity to finance capital works generated from operating cash flows. The higher the percentage, the greater the ability for the entity to finance capital works from their own funds. This indicator is taken directly from the water entities published performance reports. |

Capital replacement (ratio) |

Cash outflows for property, plant and equipment / Depreciation |

Comparison of the rate of spending on infrastructure with its depreciation. Ratios higher than 1:1 indicate that spending is faster than the depreciating rate. This is a long-term indicator, as capital expenditure can be deferred in the short term if there are insufficient funds available from operations, and borrowing is not an option. Cash outflows for property, plant and equipment are taken from the cash flow statement. Depreciation is taken from the comprehensive operating statement. |

Interest cover |

Net operating cash flows before net interest and tax payments / Net interest payments |

This measures an entity's ability to meet ongoing interest payments and ability to service debt. Net operating cash flows and net interest and tax payments are obtained from the cash flow statement. |

Debt service cover |

Profit plus interest, depreciation and amortisation / Total interest, debt repayments and finance lease repayments |

This measures the ability of an entity to repay its debt (includes finance lease arrangements) from operating profits. Profit (i.e. net result), interest, depreciation and amortisation are taken from the comprehensive operating statement. Total interest, debt repayments and finance lease repayments are taken from the cash flow statement (net of any gross up rollover/refinancing impacts). |

Debt-to-assets |

Debt / Total assets |

This is a longer-term measure that compares all current and non-current interest bearing liabilities to total assets. It complements the liquidity ratio which is a short-term measure. A low ratio indicates less reliance on debt to finance the assets of an organisation. Balances are obtained from the balance sheet. |

Financial sustainability risk assessment criteria

The financial sustainability of each water entity has been assessed using the risk criteria outlined in Figure D2.

Figure D2

Financial sustainability risk indicators

– risk assessment criteria

Risk |

Net result (%) |

Liquidity (ratio) |

Internal financing (%) |

Capital replacement (ratio) |

Interest cover |

Debt service cover |

Debt-to-assets |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

High |

Negative 10% or greater |

Less than 0.75 |

Less than 10% |

Less than 1.0 |

Less than 1.0 |

Less than 0.9 |

More than 1.0 |

Insufficient revenue is being generated to fund operations and asset renewal. |

Immediate sustainability issues with insufficient current assets to cover liabilities. |

Limited cash generated from operations to fund new assets and asset renewal. |

Spending on capital works has not kept pace with consumption of assets. |

Insufficient interest cover to meet ongoing interest payments. |

Insufficient operating profit to meet debt and interest repayments. |

Long-term risk over ability to repay debt. |

|

Medium |

Negative 10%–0% |

0.75–1.0 |

10–35% |

1.0–1.5 |

1.0–2.0 |

0.9–1.0 |

0.5–1.0 |

A risk of long-term run down of cash reserves and inability to fund asset renewals. |

Need for caution with cash flow, as issues could arise with meeting obligations as they fall due. |

May not be generating sufficient cash from operations to fund new assets and asset renewal. |

May indicate spending on asset renewal is insufficient. |

May not be able to service debt as interest payments fall due. |

May indicate risks over the ability to repay debt. |

May indicate risks over the ability to repay the debt. |

|

Low |

More than 0% |

More than 1.0 |

More than 35% |

More than 1.5 |

More than 2.0 |

More than 1.0 |

Less than 0.5 |

Generating surpluses consistently. |

No immediate risks with repaying short-term liabilities as they fall due. |

Generating enough cash from operations to fund new assets and asset renewal. |

Low risk of insufficient spending on asset renewal. |

Low risk of debt servicing issues. |

Low risk over ability to repay debt. |

Low risk over repaying debt from own source revenue. |

Source: VAGO.

The financial sustainability risk for each water entity, for the financial years ended 30 June 2012 to 2016 are shown in Figures D3 to D21.

It is important to also note that all indicators used in our assessments are now directly calculated from financial transactions and balances reported as per published financial reports or performance reports of the water entities—no adjustments have been made to these figures—this is to ensure consistency among entities within the sector and across sector reports.

Metropolitan

Wholesaler

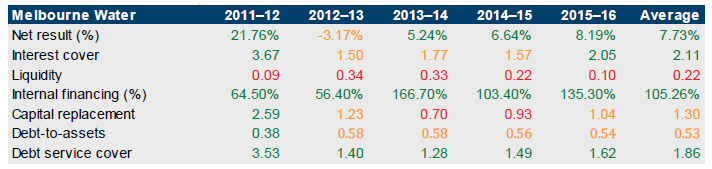

Figure D3

Melbourne Water

Source: VAGO.

Retailers

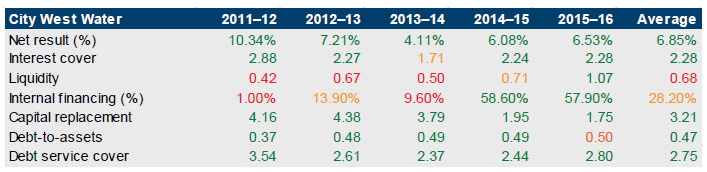

Figure D4

City West Water

Source: VAGO.

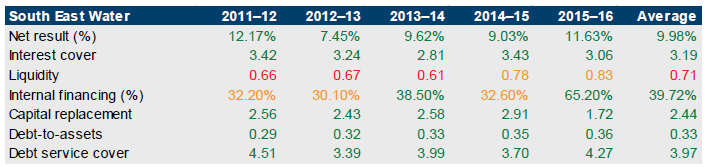

Figure D5

South East Water

Source: VAGO.

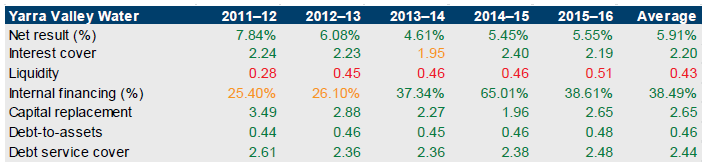

Figure D6

Yarra Valley Water

Source: VAGO.

Regional urban

Figure D7

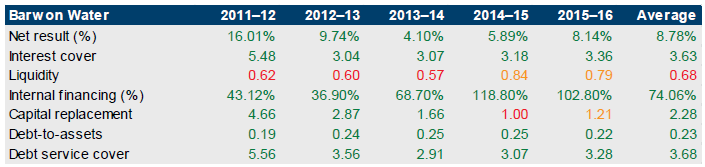

Barwon Water

Source: VAGO.

Figure D8

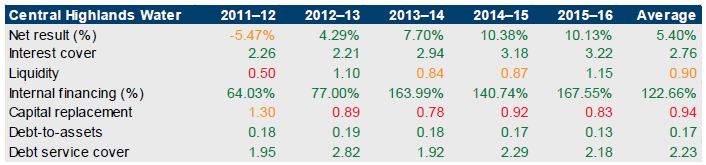

Central Highlands Water

Source: VAGO.

Figure D9

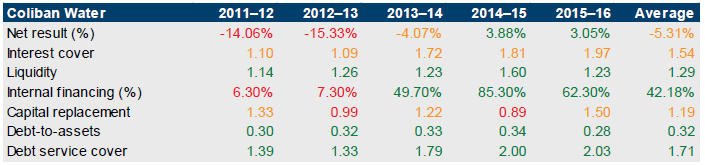

Coliban Water

Source: VAGO.

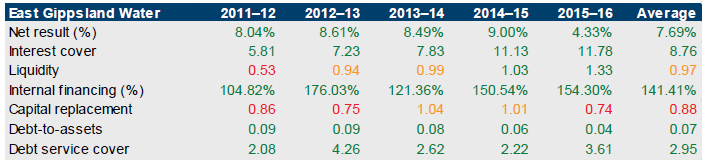

Figure D10

East Gippsland Water

Source: VAGO.

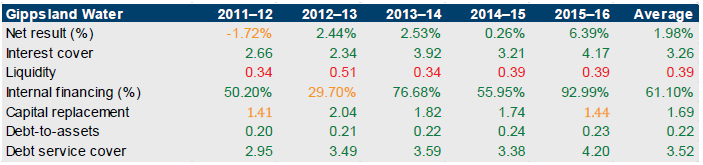

Figure D11

Gippsland Water

Source: VAGO.

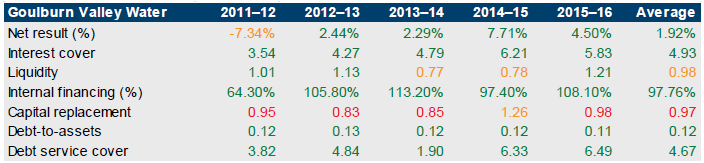

Figure D12

Goulburn Valley Water

Source: VAGO.

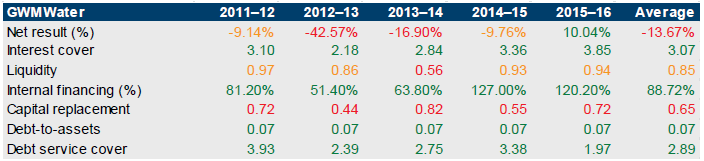

Figure D13

GWMWater

Source: VAGO.

Figure D14

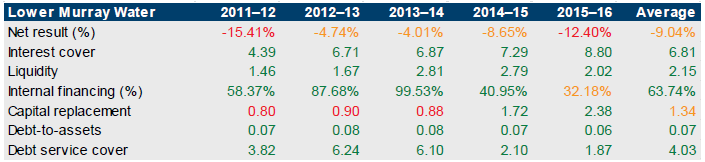

Lower Murray Water

Source: VAGO.

Figure D15

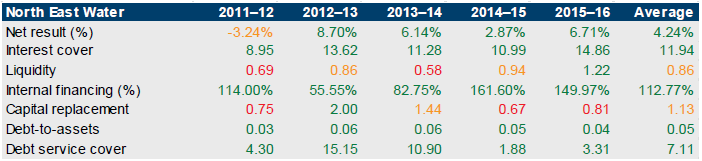

North East Water

Source: VAGO.

Figure D16

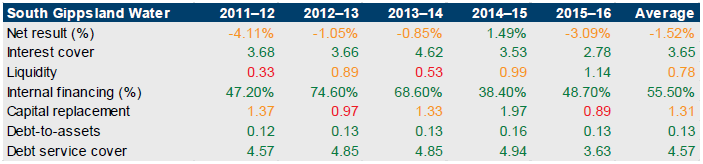

South Gippsland Water

Source: VAGO.

Figure D17

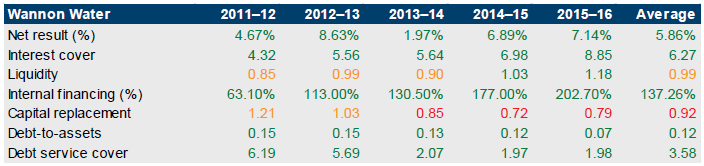

Wannon Water

Source: VAGO.

Figure D18

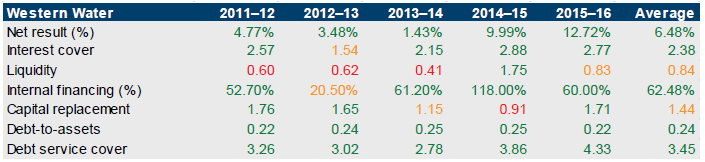

Western Water

Source: VAGO.

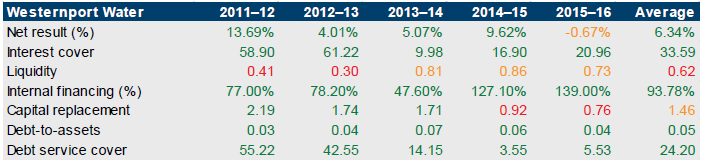

Figure D19

Westernport Water

Source: VAGO.

Rural

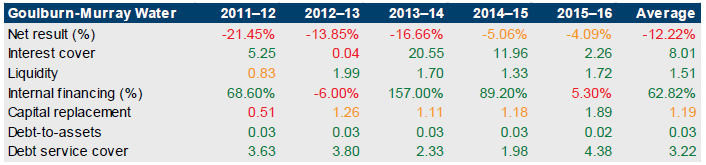

Figure D20

Goulburn-Murray Water

Source: VAGO.

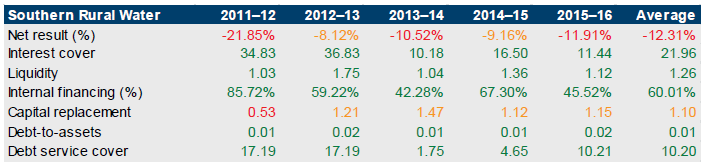

Figure D21

Southern Rural Water

Source: VAGO.

Appendix E. Asset valuation framework

Figure E1 shows the key elements of an effective asset valuation framework. Part 4 discusses the results of the 2015–16 valuation exercise.

Figure E1

Key elements of an effective asset valuation framework

Elements |

|

|---|---|

Policy |

|

Measurement and valuation of non-current physical assets policy and guidelines exist and:

|

|

Policy and guidelines are approved. |

|

Management practices |

|

Terms of engagement with the appointed valuer documented and agreed with management, and align with the requirements of the exercise. |

|

Comprehensive and regular reporting to management and audit committee. |

|

Reasonableness of the valuation result assessed considering:

|

|

Regular reporting by management to audit committee on the revaluation exercise and outcome. | |

|

Recommendation by management to the audit committee and board regarding adoption of valuation results. |

|

Management review of policy, procedures and practices periodically. |

|

Governance and oversight |

|

Policy and procedures approved by the audit committee. |

|

Periodic review of policies by management and audit committee. |

|

Internal audit used to review policy, processes and practice periodically. |

Source: VAGO.

Appendix F. Acronyms and glossary

Acronyms

AAS—Australian Auditing Standard

AASB—Australian Accounting Standards Board

DELWP—Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning

DTF—Department of Treasury & Finance

ESC—Essential Services Commission

FMA—Financial Management Act 1994

FRD—Financial Reporting Direction

MRD—Ministerial Reporting Direction

VAGO—Victorian Auditor-General's Office

VGV—Valuer-General Victoria

WIRO—Water Industry Regulatory Order

Glossary

Accountability

Responsibility of public entities to achieve their objectives in reliability of financial reporting, effectiveness and efficiency of operations, compliance with applicable laws, and reporting to interested parties.

Amortisation

The systematic allocation of the depreciable amount of an intangible asset over its expected useful life.

Asset

An item or resource controlled by an entity that will be used to generate future economic benefits.

See also physical asset.

Asset valuation

The fair value of a non-current asset on a specified date.

Audit Act 1994

Victorian legislation establishing the Auditor-General's operating powers and responsibilities and detailing the nature and scope of audits that the Auditor-General may carry out.

Audit committee

Helps a governing board to fulfil its governance and oversight responsibilities and strengthen accountability of senior management.

Audit opinion

A written expression, within a specified framework, indicating the auditor's overall conclusion about a financial (or performance) report based on audit evidence.

Carrying value

The original cost of an asset, less the accumulated amount of any depreciation or amortisation, less the accumulated amount of any asset impairment.

Capital expenditure

Money an entity spends on:

- new physical assets, including buildings, infrastructure, plant and equipment

- renewing existing physical assets to extend the service potential or life of the asset.

Catchment Management Authority

A body established under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 that has management powers over regional waterways, floodplains, drainage and other water to maintain the health of rivers and wetlands.

Clear audit opinion

A positive written expression provided when the financial report has been prepared and presents fairly the transactions and balances for the reporting period in keeping with the requirements of the relevant legislation and Australian Accounting Standards—also referred to as an unqualified audit opinion.

Corporations Act 2001

Commonwealth legislation governing corporations, including their financial reporting framework.

Debt

Money owed by one party to another party.

Depreciated replacement cost

Current replacement cost less accumulated depreciation to reflect the economic benefits of the assets that have been consumed.

Depreciation

Systematic allocation of the value of an asset over its expected useful life, recorded as an expense.

Entity

A corporate or unincorporated body that has a public function to exercise on behalf of the state or is wholly owned by the state, including departments, statutory authorities, statutory corporations and government business enterprises.

Equity or net assets

Residual interest in the assets of an entity after deduction of its liabilities.

Expense

The outflow of assets or the depletion of assets an entity controls during the financial year, including expenditure and the depreciation of physical assets. An expense can also be the incurrence of liabilities during the financial year, such as increases to a provision.

Fair value

The price that would be received if an asset was sold or the price paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date.

Financial Management Act 1994

Victorian legislation governing public sector entities, as determined by the Minister for Finance, including their financial reporting framework.

Financial report

A document reporting the financial outcome and position of an entity for a financial year, which contains an entity's financial statements, including a comprehensive income statement, a balance sheet, a cash flow statement, a comprehensive statement of equity and notes.

Financial Reporting Direction

Issued by the Minister for Finance for entities reporting under the Financial Management Act 1994, with the aim of:

- achieving consistency and improved disclosure in financial reporting for Victorian public entities by eliminating or reducing divergence in accounting practices

- prescribing the accounting treatment and disclosure of financial transactions in circumstances where there are choices in accounting treatment, or where existing accounting procurements have no guidance or requirements.

Financial sustainability

An entity's ability to manage financial resources so it can meet its current and future spending commitments, while maintaining assets in the condition required to provide services.

Financial year

A period of 12 months for which a financial report is prepared, which may be a different period to the calendar year.

Governance

The control arrangements used to govern and monitor an entity's activities to achieve its strategic and operational goals.

Income approach

A valuation technique that converts future amounts (such as cash flows or income and expense) to a single current (discounted) amount. The fair value is measured as the value indicated by current market expectations about those future amounts.

Internal audit

A function of an entity's governance framework that examines and reports to management on the effectiveness of the entity's risk management, internal control and governance processes.

Internal control

A method of directing, monitoring and measuring an entity's resources and processes to prevent and detect error and fraud.

Liability

A present obligation of the entity arising from past events, the settlement of which is expected to result in an outflow of assets from the entity.

Management letter

A letter the auditor writes to the governing body, the audit committee and management of an entity outlining issues identified during the financial audit.

Net result

The value that an entity has earned or lost over the stated period (usually a financial year), calculated by subtracting an entity's total expenses from the total revenue for that period.

Performance report

A statement detailing an entity's predetermined performance indicators and targets for the financial year, and the actual results achieved along with explanations for any significant variances between the actual result and the target.

Physical asset

A non-financial asset that is a tangible item an entity controls, and that will be used by the entity for more than 12 months to generate profit or provide services, such as building, equipment or land.

Price cap

An imposed limit on how high a price is charged for a product.

Qualified audit opinion

An opinion issued when the auditor concludes that an unqualified opinion cannot be expressed because of:

- disagreement with those charged with governance or

- conflict between applicable financial reporting frameworks or

- limitation of scope.

A qualified opinion is considered to be unqualified except for the effects of the matter to which the qualification relates.

Regulatory period

A statutory defined period that reflects all of the financial/operational activities that took place during that time.

Relevant measures or indicators

Measures or indicators an entity uses if they have a logical and consistent relationship to its objectives and are linked to the outcomes to be achieved.

Revaluation

The restatement of a value of non-current assets at a particular point in time.

Revenue

Inflows of funds or other assets or savings in outflows of service potential, or future economic benefits in the form of increases in assets or reductions in liabilities of an entity, other than those relating to contributions by owners, that result in an increase in equity during the reporting period.

Risk

The chance of a negative or positive impact on the objectives, outputs or outcomes of an entity.

Water Plan

A document prepared and published by a water business, setting out the services, key projects and prices that the business proposes to deliver over the regulatory period.