Water Entities: Results of the 2013–14 Audits

Overview

This report covers the results of our financial audits of 20 entities, comprising 19 water entities and one controlled entity. The report informs Parliament about significant issues arising from the audits of financial and performance reports and augments the assurance provided through audit opinions included in the respective entities’ annual reports.

Parliament can have confidence in the water entities financial reports and performance reports as all were given unmodified audit opinions for 2013–14. It is pleasing to note that both financial reports and performance reports met the legislated time frames and improvement has occurred in the quality of performance reporting during 2013–14.

The sector generated a net profit before income tax of $318.2 million, an increase of $234.5 million. The increase is largely due to two metropolitan water entities reporting significantly higher profits as a result of higher water consumption and increased water, sewerage and other prices, as approved under the regulatory price setting model.

This report highlights some key financial challenges and risks for the water entities, including repaying growing debt and continuing to meet ongoing financial obligations to the state, such as taxes and levies. It also highlights significant increases in total water and sewerage charges by the three metropolitan water retailers in 2013–14.

Water Entities: Results of the 2013–14 Audits: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER February 2014

PP No 5, Session 2014–15

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit the Auditor-General's report Water Entities: Results of the 2013–14 Audits.

This report summarises the results of the financial audits of the 19 water entities and one controlled entity for the year-ended 30 June 2014.

It informs Parliament about significant issues arising from the audits of financial and performance reports and complements the assurance provided through individual audit opinions included in the respective entities' annual reports.

The report also highlights the sector's financial results and financial sustainability risks.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

12 February 2015

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Roberta Skliros—Engagement Leader Jenneth Garcia—Team Leader Jie Yang—Team Senior Jessica Cross, Richard Ly and Steven Zanetti—Team members Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Craig Burke |

Victoria's water industry includes 20 public sector entities, comprising 19 water entities and one controlled entity. These entities are stand-alone businesses that are expected to adopt sustainable management practices, which allow water resources to be conserved, properly managed, and sustained.

Parliament can have confidence in the water entity financial reports and performance reports as all were given unmodified audit opinions for 2013–14. It is pleasing to note both financial reports and performance reports met the legislated time frames and improvement has occurred in the quality of performance reporting during 2013–14.

The sector generated a net profit before income tax of $318.2 million, an increase of $234.5 million. The increase is largely due to two metropolitan water entities reporting significantly higher profits as a result of increased water, sewerage and other prices, as approved under the regulatory price setting model, higher water consumption, and a reduction in refunds to customers because of the desalination plant.

The three metropolitan water retailers increased their total water and sewerage charges to customers by $474.9 million during 2013–14. However, they had increased costs of approximately $490 million for bulk water, sewerage and other charges they pay to the system's wholesaler, that is Melbourne Water. Both increases are a consequence of higher regulated prices and water consumption. Melbourne Water also had cost increases, such as a $178.3 million increase in finance costs, mainly because of the first full year impact of the desalination plant. Nevertheless, it reported a net profit before income tax of $131.9 million, an increase of $193.5 million on the prior year net loss.

While the three metropolitan water retailers increased their total water and sewerage charges by 25.5 per cent in 2013–14, the 13 regional urban water entities had an increase of 3.5 per cent, and the two rural water entities combined, declined by 3.1 per cent.

The water sector is facing increased financial sustainability risks given the five-year trend to 2013–14. Three entities had high financial sustainability risks and ten entities had medium financial sustainability risks in 2013–14. Some of these risk ratings are partly a consequence of the regulatory price setting model, where there is a shortfall between the price set and the total operating costs of some entities. I intend to take a closer look at the regulatory price setting model in the future.

Other key financial challenges for the water entities include repaying growing debt and continuing to meet ongoing financial obligations to the state such as taxes and levies. The depth and breadth of debt refinancing is another area I plan to assess more closely in future reports.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

February 2015

Audit Summary

This report covers the results of the 2013–14 financial audits of 20 entities, comprising 19 water entities and one controlled entity.

It provides an analysis of their financial and performance reporting, financial results and financial sustainability risks. It also comments on the effectiveness of general internal controls, the operations of audit committees and the management of gifts, benefits and hospitality.

Conclusions

Parliament can have confidence in the adequacy of financial and performance reporting of the water entities for the year-ended 30 June 2014.

Unqualified audit opinions were issued on the 20 financial reports, which means the audited financial information fairly presents the entities' transactions and cash flows for the 2013–14 financial year, and their assets and liabilities as at 30 June 2014.

Unqualified audit opinions were also issued on all 19 performance reports, which means that the audited information fairly presents the results against the specified performance indicators for the 2013–14 financial year. The controlled entity does not prepare a performance report.

The water sector is facing increased financial sustainability risks given the five year trend to 2013–14. Three entities had high financial sustainability risks and 10 entities had medium financial sustainability risks in 2013–14. Some of these risk ratings are partly a consequence of the regulatory price setting model, where there is a shortfall between the price set and the total operating costs of some entities. We intend to take a closer look at the regulatory price setting model in the future.

Key financial challenges for the water entities include repaying growing debt and continuing to meet ongoing financial obligations to the state such as taxes and levies. The depth and breadth of debt refinancing is another area we plan to assess more closely in future reports.

Parliament can have confidence that the role of audit committees at water entities is being carried out in an effective manner.

While the minimum required policies and processes are in place to manage gifts, benefits and hospitality for assessed entities, there are opportunities for improvement.

Findings

Financial and performance reporting

Financial reporting processes were generally adequate for preparing accurate and timely financial reports, although opportunity for improvement exists.

In the past only 16 of the 19 water entities were required to prepare audited performance reports, however the release of Financial Reporting Direction 27C Presentation and Reporting of Performance Information during 2013–14 extended this requirement to all 19 water entities.

An improvement has occurred in performance reporting during 2013–14, largely due to the efforts of an industry working group and the former Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI), however further areas still require attention.

Financial results and sustainability risks

The 19 water entities, excluding the controlled entity, generated a net profit before income tax of $318.2 million for the year-ended 30 June 2014, an increase of $234.5 million or 280 per cent from the prior year. The increase is largely due to two metropolitan water entities reporting significantly higher profits as a result of increased water, sewerage and other charges, as approved under the regulatory price setting model, higher water consumption, and a reduction in refunds to customers because of the desalination plant.

The three metropolitan water retailers increased their total water and sewerage charges to customers by $474.9 million during 2013–14. However, they had increased costs of approximately $490 million for bulk water, sewerage and other charges they pay to the system's wholesaler, that is Melbourne Water. Both increases are a consequence of higher regulated prices and water consumption. Melbourne Water also experienced cost increases, such as a $178.3 million increase in finance costs, mainly because of the first full year impact of the desalination plant. Nevertheless, it reported a net profit before income tax of $131.9 million, an increase of $193.5 million on the prior year net loss.

While the three metropolitan water retailers increased their total water and sewerage charges by 25.5 per cent in 2013–14, the 13 regional urban water entities had an increase of 3.5 per cent, and the two rural water entities combined, declined by 3.1 per cent.

At 30 June 2014, the 19 water entities controlled $42 billion in total assets ($41.4 billion at 30 June 2013) and had total liabilities of $20.3 billion ($20.1 billion at 30 June 2013).

Whilst increased profitability is apparent for some entities in 2013–14, several water entities continue to face challenges repaying growing debt, while also continuing to meet ongoing financial obligations to the state, such as taxes and levies, and addressing efficiency measures from sector reform, as experienced with the former government's Fairer Water Bills initiative.

The water sector is facing increased financial sustainability risks given the five-year trend to 2013–14. Three entities had high financial sustainability risks and ten entities had medium financial sustainability risks in 2013–14. Some of these risk ratings are partly a consequence of the regulatory price setting model, where there is a shortfall between the price set and the total operating costs of some entities.

Forming a definitive view of any entity's financial sustainability requires a holistic analysis that moves beyond financial considerations to include the water entity's ability to efficiently manage their operations, and the environment in which they operate—particularly the regulatory environment in which a water entity operates.

Audit committees

Audit committees play a significant role in assisting a governing board to fulfil its governance, oversight and accountability responsibilities. To be fully effective, an audit committee must be independent from management and free from any undue influence. Members of the audit committee should not have any executive powers, management functions or delegated financial responsibility.

The standing directions issued by the Minister for Finance, pursuant to the Financial Management Act 1994, require each entity to have an audit committee.

We reviewed the effectiveness of audit committees in discharging their responsibilities, including how they oversee an entity's control environment, the accountability of senior management and key outputs, and their relationship with internal and external auditors.

Our review shows a satisfactory situation, where the role is being carried out in an effective manner. We did, however identify opportunities for improvement to audit committees' engagement with internal and external auditors, the nature and conduct of self-assessments and fraud reporting. Further, elements of committee charters also require improvement to reflect better practice.

Gifts, benefits and hospitality

Gifts, benefits and hospitality are offered by, and provided to, water entities and employees for a variety of reasons. There is an expectation that water entities and employees should hold high standards of ethical behaviour and not accept gifts, benefits or hospitality from parties seeking to unfairly influence decision-making.

Between 2012–13 and 2013–14, the number of gifts, benefits and hospitality offered and/or accepted by the four metropolitan water entities increased from 423 in 2012–13 to 588 in 2013–14.

We assessed the management practices and oversight of gifts, benefits and hospitality at the four metropolitan water entities against the Victorian Public Sector Commission's Gifts, Benefits and Hospitality Policy Framework and other policy and guidance issued by the former DEPI.

Overall, the four metropolitan water entities had the minimum required policies in place, which are appropriate to manage the receipt of gifts, benefits and hospitality. Although policies and procedures were in place, these could benefit from a review to ensure greater consistency with the Commission's framework and the former DEPI's model policy and guidance. Further, all water entities should require staff to complete gift, benefit and hospitality declaration forms and improve the information recorded in their gift, benefits and hospitality registers.

Recommendations

That water entities:

-

continue to work closely with their industry body to ensure that the preparation and release of the industry's model financial report occurs earlier

-

identify, at an early stage, and understand the requirements that stem from financial reporting changes by the Australian Accounting Standards Board and/or the Financial Reporting Directions

-

further refine their financial reporting processes by conducting materiality assessments, preparing analytical reviews and preparing quality shell financial statements.

That the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning:

-

engages early with water entities to ensure that all indicators—at an appropriate level of granularity—are included in the corporate plans of water entities

-

enhances the guidance supporting the Ministerial Reporting Direction 01 Performance Reporting, to address issues encountered with the calculation of variances and the requirements of variance explanations.

That water entities:

-

critically assess the way they calculate and explain variances ensuring performance reports fully address the requirements of the Ministerial Reporting Direction 01 Performance Reporting.

That water entities, where relevant:

-

enhance their audit committee charters to incorporate all better practice requirements, such as developing an audit committee annual program, preparation and circulation of agendas and papers, and addressing requirements and nature of how declarations of conflicts of interest and pecuniary interests are conducted.

-

require audit committees to specifically conduct, at least annually, a self-assessment of their performance

-

enhance fraud reporting to audit committees including the annual report of suspected, alleged or actual frauds

-

provide internal and external auditors with open invitations to attend committee meetings and provide access to committee documentation for upcoming meetings

-

require audit committees to develop a process for assessing recommendations of relevance to them in VAGO performance audits to stimulate improvements in controls or operational performance

-

improve their gifts, benefits and hospitality policies to ensure they are fully consistent with Victorian Public Sector Commission's framework and the former Department of Environment and Primary Industries' model policy and guidance, and that policies are reviewed within specified time frames

-

enhance their processes to include a requirement for offers of gifts, benefits and hospitality that are declined, to be declared and recorded on the gift register

-

conduct training, on a regular basis, for employees to ensure they are well aware of, and understand, the policies and procedures relating to gifts, benefits and hospitality

-

enhance the contents of their gift registers to include all elements proposed in the Victorian Public Sector Commission's framework and the former Department of Environment and Primary Industries' model policy and guidance

-

record within a register any gifts, benefits and hospitality provided to vendors and/or other stakeholders

-

require all staff to complete a gift, benefit and hospitality declaration form for reportable gifts, which incorporates all better practice elements set out by the Victorian Public Sector Commission and the former Department of Environment and Primary Industries, and retain in a central repository

-

consider inclusion of a gift, benefit and hospitality review in their internal audit plans, or establish other internal review processes.

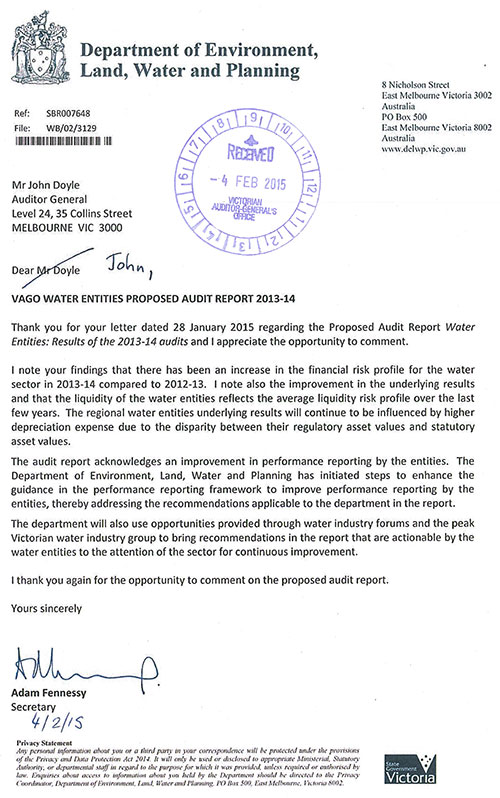

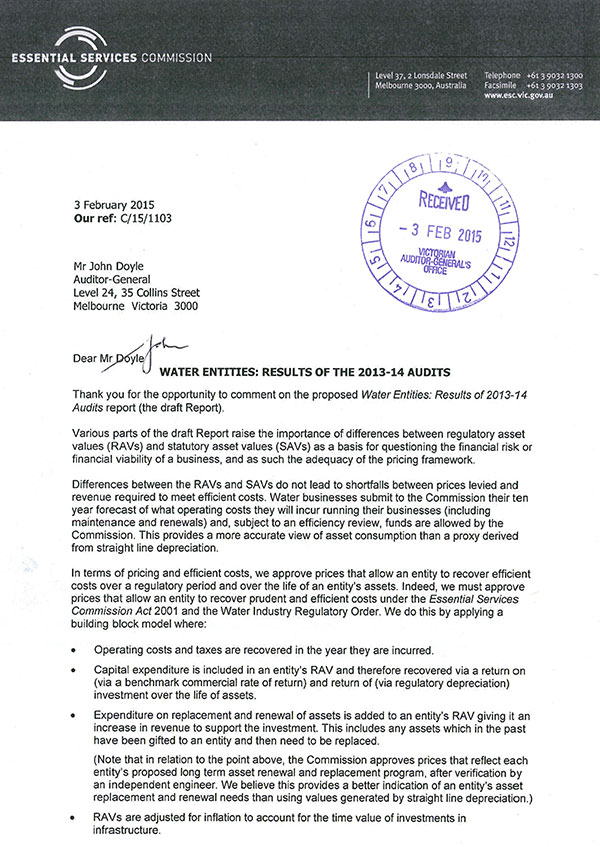

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report, or relevant extracts from the report, were provided to all water entities, the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, the Essential Services Commission and the Victorian Water Industry Association (VicWater), with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix H.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

The Victorian water industry includes 20 public sector entities, comprising 19 water entities and one controlled entity. The entities are stand-alone businesses responsible for their own management and performance. The 19 water entities are expected to adopt sustainable management practices which give due regard to environmental impacts that allow water resources to be conserved, properly managed, and sustained.

This report provides the results of the financial audits of the 20 entities. It is one of a suite of Parliamentary reports on the results of the 2013–14 financial audits conducted by VAGO. The full list of reports can be found in Appendix A of this report.

Figure 1A lists the legal and trading names of the 20 entities that form part of the Victorian water industry.

Figure 1A

Water entities and controlled entity

Legal name |

Trading name |

|---|---|

Metropolitan sector |

|

Wholesaler | |

|

Melbourne Water Corporation |

Melbourne Water |

Retailers | |

| City West Water Corporation | City West Water |

| South East Water Corporation | South East Water |

Yarra Valley Water Corporation | Yarra Valley Water |

Regional urban sector |

|

Barwon Region Water Corporation |

Barwon Water |

Central Gippsland Region Water Corporation |

Gippsland Water |

Central Highlands Region Water Corporation |

Central Highlands Water |

Coliban Region Water Corporation |

Coliban Water |

East Gippsland Region Water Corporation |

East Gippsland Water |

Goulburn Valley Region Water Corporation |

Goulburn Valley Water |

Grampians Wimmera Mallee Water Corporation |

GWMWater |

Lower Murray Urban and Rural Water Corporation |

Lower Murray Water |

North East Region Water Corporation |

North East Water |

South Gippsland Region Water Corporation |

South Gippsland Water |

Wannon Region Water Corporation |

Wannon Water |

Western Region Water Corporation |

Western Water |

Westernport Region Water Corporation |

Westernport Water |

Rural sector |

|

Gippsland and Southern Rural Water Corporation |

Southern Rural Water |

Goulburn-Murray Rural Water Corporation |

Goulburn-Murray Water |

Controlled entity |

|

Watermove Pty Ltd |

Watermove |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Watermove is a controlled entity of Goulburn-Murray Water. At a board meeting on 10 August 2012, the directors of Watermove resolved to discontinue the operations of the company. Watermove ceased trading on 13 August 2012.

As at 30 June 2014 and consistent with the prior year, there were no plans to wind up or deregister the company. Watermove continues to exist as a legal entity under the ownership of Goulburn-Murray Water, however does not actively trade. As a result, a financial report was prepared and audited, where an unqualified audit opinion was issued for the financial year-ended 30 June 2014.

As the entity no longer actively trades, we make no further comment on the results of that audit throughout this report.

1.2 Structure of this report

Figure 1B outlines the structure of this report.

Figure 1B

Report structure

Part |

Description |

|---|---|

Part 2: Financial reporting |

Reports on the results of the 2013–14 financial audits of the 19 water entities. |

Part 3: Performance reporting |

Reports on the results of the 2013–14 performance reports of the 19 water entities. |

Part 4: Financial results |

Summarises and analyses the financial results of the 19 water entities, including financial performance for the 2013–14 reporting period. |

Part 5: Financial sustainability risks |

Provides insight into the financial sustainability risks of the 19 water entities based on the trends of seven financial sustainability indicators over a five-year period. Provides commentary around the regulatory price setting process and how this impacts the financial performance of water entities, including the risks associated with financial sustainability. |

Part 6: Audit committees |

Assesses the key responsibilities and arrangements of the 19 water entity audit committees, including how they oversee an entity's control environment, accountability of senior management and key outputs, and their relationship with internal and external auditors. |

Part 7: Gifts, benefits and hospitality |

Assesses the processes established at the four metropolitan water entities relating to the management of gifts, benefits and hospitality. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.3 Audit of financial reports

A financial report is a structured representation of financial information, which usually includes accompanying notes, derived from accounting records. It indicates whether an entity generated a profit or loss and details an entity's assets and obligations at a point in time or the changes therein for a specified reporting period in accordance with a financial reporting framework.

An annual financial audit in the Victorian public sector has two aims:

- to give an opinion consistent with section 9 of the Audit Act 1994, on whether the financial report is presented fairly in accordance with the relevant financial reporting framework

- to consider whether there has been wastage of public resources or a lack of probity or financial prudence in the management or application of public resources, consistent with section 3A(2) of the Audit Act 1994.

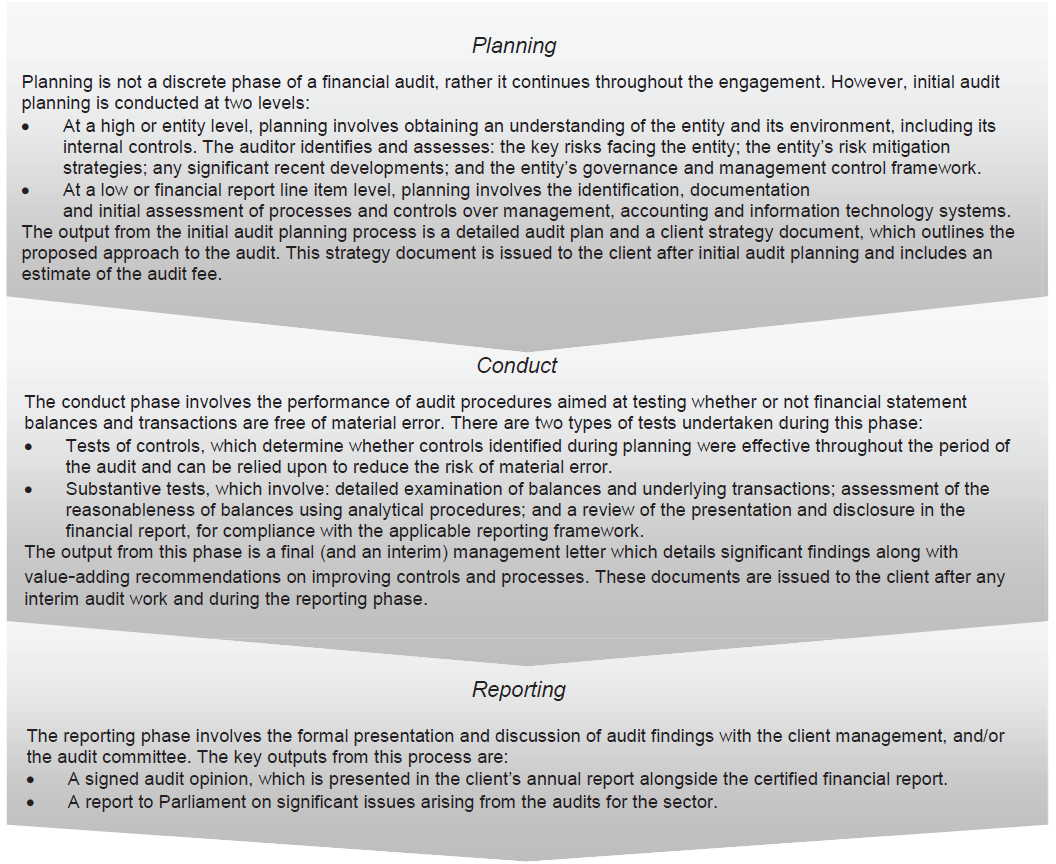

The financial audit framework applied in the conduct of the audits is set out in Appendix B.

1.3.1 Audit of internal controls relevant to the preparation of the financial report

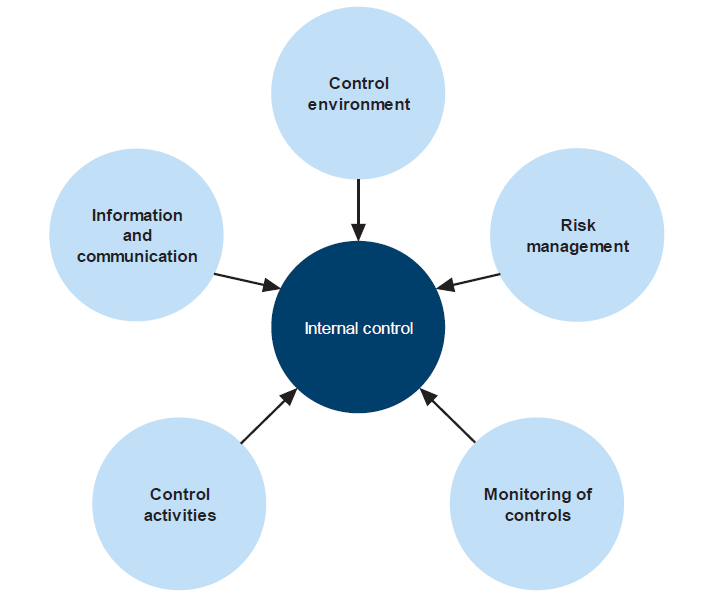

Integral to the annual financial audit is an assessment of the adequacy of the internal control framework, and the governance processes related to an entity's financial reporting. In making this assessment, consideration is given to the internal controls relevant to the entity's preparation and fair presentation of the financial report, but this assessment is not used for the purpose of expressing an opinion on the effectiveness of the entity's internal control.

Internal controls are systems, policies and procedures that help an entity reliably and cost effectively meet its objectives. Sound internal controls enable the delivery of reliable, accurate and timely internal and external reporting.

An explanation of the internal control framework, and its main components, is set out in Appendix B. An entity's governing body is responsible for developing and maintaining its internal control framework.

The internal control weaknesses we identify during an audit do not usually result in a 'qualified' audit opinion because often an entity will have compensating controls in place that mitigate the risk of a material error in the financial report, or we are able to undertake additional audit procedures to mitigate those risks. A qualification is warranted only if weaknesses cause significant uncertainty about the accuracy, completeness and reliability of the financial information being reported.

Weaknesses in internal controls found during the audit of an entity are reported to its board chairman, the managing director and audit committee chair, in a management letter.

Our reports to Parliament raise systemic or common weaknesses identified during our assessments of internal controls over financial reporting. Analysis of these weaknesses can be found in Part 2.

1.4 Conduct of water entity financial audits

The audits of the 19 water entities were undertaken in accordance with Australian Auditing Standards.

Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of preparing and printing this report was $210 000.

1.5 Audit of performance reports

A performance report is a statement containing:

- predetermined performance indicators which are financial and/or non-financial

- targets for each financial and/or non-financial performance indicator

- current year results for the performance indicators

- prior year results for the performance indicators

- explanations detailing the cause of significant variances from current year results to that of the target and/or prior year.

The reporting obligation and audit requirement for performance reports is imposed by Financial Reporting Direction (FRD) 27C Presentation and Reporting of Performance Information, which was released in May 2014 pursuant to the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA). For the 2013–14 reporting period, the performance indicators and reporting requirements for each water entity type (metropolitan, regional urban and rural) were determined by the then Minister for Water, as detailed in the Ministerial Reporting Direction (MRD) 01 Performance Reporting, also issued in May 2014.

Together, these two instruments require all water entities to prepare and have audited annual performance reports. In the past only 16 of the 19 water entities were required to prepare and have audited such reports, however the release of FRD 27C during the period extended the requirement to all water entities.

Pursuant to section 8(3) of the Audit Act 1994, the Auditor-General may audit any report of operations of an entity where performance reporting is contained, to determine whether any performance indicators:

- are relevant to any stated objectives of the entity

- are appropriate for the assessment of the entity's actual performance

- fairly represent the entity's actual performance.

The Auditor-General uses this authority to audit the performance reports prepared by the public sector water entities under FRD 27C. Currently, we form an opinion on whether the performance indicators fairly represent the entity's actual performance. We do not form an opinion on the relevance or appropriateness of the reported performance indicators.

Further analysis of performance reporting can be found in Part 3 of this report.

1.6 Emerging events

1.6.1 Industry initiatives

On 18 January 2014, the then Minister for Water announced the implementation of the Fairer Water Bills initiative. The initiative was designed to produce lower water bills for Victorian water consumers from the 2014–15 reporting period.

There were two key parts to the initiative:

- an efficiency review of Victoria's urban water entities

- a review of the economic regulation of the water industry.

Efficiency review

Under the initiative, the then Victorian Government requested water entities to identify cost savings to contribute to delivering lower household water bills via a direct rebate or tariff reduction to eligible customers. The initiative covered all metropolitan and regional urban water entities across Victoria. It did not include water entities that service only rural areas.

Relevant water entities identified capital and operational cost savings. Cost efficiencies were to be determined without impacting service standards or existing hardship provisions.

For relevant water entities, the implementation of cost-saving initiatives commenced for the 2014–15 reporting period, with the exception of Melbourne Water, which commenced cost-saving initiatives in the 2013–14 reporting period.

Customers received savings to their water bills, via a rebate or tariff adjustment, from 1 July 2014. Water entities have committed in principle to continue deriving savings to pass on to customers over the next four years.

Review of the economic regulation

The economic regulation framework review was incomplete leading into the November 2014 election. Its objective was to review the way in which water prices were set and consider whether opportunities existed for improvement to the current regulatory framework.

Preliminary advice stemming from this review was publically released in May 2014.

Stakeholders were consulted through public information and stakeholder engagement sessions, and written submissions were accepted up until June 2014. In total, 24 submissions were received. All of this feedback was under consideration at the time of the state election. The future progression of the review is contingent upon the reform agenda of the new government.

1.6.2 Water Industry Regulatory Order 2014

On 23 October 2014, the Water Industry Regulatory Order 2014 (WIRO 2014) was released in the Victoria government gazette, following approval by the Governor in Council. The purpose of WIRO 2014 is to provide a framework for economic regulation by the Essential Services Commission (ESC) for services provided by the water industry by:

- specifying which goods and services are to be prescribed goods and services in respect of which ESC has the power to regulate prices of

- declaring which goods and services are to be declared goods and services in respect of which ESC has the power to regulate standards and conditions of service and supply

- specifying the approach to be adopted by ESC in regulating the price of prescribed goods and services

- specifying particular matters to which ESC must have regard in exercising its powers and functions under the WIRO 2014

- conferring on ESC certain functions in relation to monitoring, performance reporting and auditing

- conferring on ESC certain functions in relation to dispute resolution.

It revokes the Water Industry Regulatory Order 2012 (WIRO 2012) and will impact the next pricing submission period. Melbourne Water and Goulburn-Murray Water will be the first pricing submissions impacted by the WIRO 2014, given their current water plans cease on 30 June 2016.

1.6.3 Water laws to be consolidated in a new Act

On 24 June 2014, the former Minister for Water introduced the Water Bill 2014 (the Bill) to Parliament. The Bill proposed to consolidate the Water Act 1989 and the Water Industry Act 1994 into a single piece of legislation for clarity. The Bill had not passed the Parliament prior to the November 2014 election.

The key elements of the Bill included:

- implementing a new approach to urban water cycle management planning

- updating the objectivesof water entitiesto reflect the way they carry out their business and to ensure consistency with the thengovernment's water policy and objectives regarding whole of water cycle management

- conferring clear statutory rights on water entities and local councils regarding water in their stormwater infrastructure

- creation of new water resource management orders, and clarification of the definition of 'environmental water'

- amending the powers of water entities, catchment management authorities or persons authorised by the Minister to enter land to perform functions or exercise powers under the Bill, to reflect current best practice

- consolidating changes to the existing statutory liability regime to reflect recent Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal and Supreme Court decisions

- establishing a new two-step process for identifying and managing long-term risks to water resources

- establishing a set of core considerations that decision-makers will be required to take into account before making certain decisions

- simplifying and regrouping the functions of water entities and catchment management authorities based on the current water industry structure

- setting out in primary legislation a licensing regime for activities which may have an impact on waterways and their surrounds

- creating an enhanced contemporary compliance and enforcement 'toolbox' with alternatives to court action and new penalties.

The progression of this Bill will be subject to any reform agenda of the new government.

1.6.4 Carbon tax repeal

Certain water entities were impacted by the former Australian government's carbon tax, where water and sewerage charges by water entities included a cost associated with meeting carbon tax obligations incurred through a water entity's supply chain.

The Australian Government abolished the carbon tax, with effect from 1 July 2014. The carbon tax repeal legislation received royal assent on 17 July 2014. With the repeal of the carbon tax, the water and sewerage charges by water entities no longer required inclusion of this impact.

This matter is currently being considered by the water entities, including the appropriateness of any returns of savings back to customers. At the time of preparing this report, the matter had not been finalised by all water entities.

1.6.5 2015–16 asset revaluation

A valuation of land, buildings and infrastructure assets for regional and rural water entities was conducted in 2010–11 as per the requirements under FRD 103D Non‑current physical assets. This was the first time in which infrastructure assets were required to be measured at fair value. Previously they were recorded at cost, as FRD 121 Infrastructure Assets (Water/Rail) provided water entities with an exemption from the fair value approach.

Our review of the 2010–11 revaluation found that improvements could be made to the processes applied to valuing infrastructure assets held by rural and regional water entities. In particular, in our Water Entities: Results of the 2010–11 Audits report we recommended that:

- water entities work with the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) and the Valuer-General Victoria (VGV) to determine the most appropriate valuation methodology for infrastructure assets

- the VGV should ensure all valuations conducted, including those by service providers, be subjected to rigorous quality assurance processes, and that appropriate effort is invested in establishing agreement with client entities before valuations are conducted.

The next scheduled revaluation will occur in 2015–16, in accordance with FRD 103E Non-current physical assets.

In preparation for the upcoming revaluation, the water industry has proactively formed an inter-agency working group, which is being administered by the industry body, Victorian Water Industry Association (VicWater). The group consists of representatives from water entities, VGV, the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) and DTF, and observers from VAGO.

The working group has been established to adequately plan and manage the upcoming revaluation process, and to engage early with key stakeholders to address emerging matters and prevent issues arising as experienced in the previous revaluation process of 2010–11.

The inter-agency working group commenced meeting on a bi-monthly basis in September 2014. The meetings are scheduled to occur up to the revaluation in June 2016. Key steps that have occurred to date are:

- establishing a timetable of key milestones, outputs and responsibilities over the revaluation process to ensure timely and accurate outcomes for 2015–16

- developing an asset valuation discussion paper, to assist in planning and conceptualising valuation guidance

- holding a workshop for representatives of water entities, to discuss the asset valuation methodology and other relevant processes to be applied

- developing asset valuation guidance—including valuation methodology—to be applied consistently across the regional and rural water entities

- developing data templates for the consistent collection, population and recording of key asset and other revaluation details.

2 Financial reporting

At a glance

Background

This Part covers the results of the 2013–14 audits of the 19 water entities. It also compares financial reporting practices in 2013–14 against better practice, legislated time lines and the prior year.

Conclusion

Parliament can have confidence in the 19 financial reports, as all were given unqualified audit opinions for 2013–14. Financial reporting preparation processes were generally adequate for preparing accurate and timely financial reports, although opportunity for improvement exists.

Findings

- The 19 water entities met the legislated 12-week financial reporting time frame.

- Water entities can improve their financial reporting preparation processes by preparing shell statements or enhancing their current shell statement preparation process, conducting materiality assessments and performing analytical reviews over their financial reports.

Recommendations

That water entities:

- continue to work closely with their industry body to ensure that the preparation and release of the industry's model financial report occurs earlier

- identify, at an early stage, and understand the requirements that stem from financial reporting changes by the Australian Accounting Standards Board and/or the Financial Reporting Directions

- further refine their financial reporting processes by conducting materiality assessments, preparing analytical reviews and preparing quality shell financial statements.

2.1 Introduction

This Part covers the results of the audits of the 2013–14 financial reports of the 19 water entities.

2.2 Audit opinions issued

Independent audit opinions add credibility to financial reports by providing reasonable assurance that the information reported is reliable and accurate. An unqualified or 'clear' audit opinion confirms that the financial report fairly presents the transactions and balances for the reporting period, in accordance with the requirements of relevant accounting standards and legislation.

Unqualified audit opinions were issued on the financial reports of all 19 entities for the 2013–14 financial year.

2.3 Quality of financial reporting

The timeliness and accuracy of the preparation of an entity's financial report is integral to the quality of reporting. Entities need to have well-planned and managed preparation processes to achieve cost-effective and efficient financial reporting.

The quality of an entity's financial reporting can be measured in part by the timeliness and accuracy of the preparation and finalisation of its financial report, as well as against better practice criteria.

Overall the financial report preparation processes of the water entities produced relevant and reliable information.

2.3.1 Accuracy

The frequency and size of errors in financial reports are direct measures of the accuracy of draft financial reports submitted for audit. Ideally, there should be no errors or adjustments required as a result of an audit.

Our expectation is that all entities will adjust any errors identified during an audit, other than those errors that are clearly trivial or clearly inconsequential to the financial report, as defined under the auditing standards. Therefore all errors identified during an audit should be adjusted, other than those that are clearly trivial.

The public is entitled to expect that any financial reports that bear the Auditor‑General's opinion are accurate and of the highest possible quality.

When our staff detect errors in draft financial reports they are raised with management. Material errors need to be corrected before an unqualified audit opinion can be issued.

The entity itself may also change its draft financial report after submitting it for audit, if they subsequently identify that the draft information is incorrect or incomplete.

Financial balance adjustments

In relation to the 2013–14 audits, 31 financial balance adjustments were made compared to 30 in the prior year. The adjustments primarily related to:

- revenue recognition

- expenditure classification

- recognition of prepayments

- recognition of developer contributed assets

- treatment of asset sales

- capitalisation of works in progress

- provisioning for expenditure

- provisioning for employee benefits

- tax effect accounting.

The adjustments resulted in changes to the net result and/or the net asset position of the relevant entities.

Financial disclosure adjustments

In addition to the financial balance adjustments, financial report disclosure amendments may be requested by VAGO, that do not necessarily impact balances or transactions on the principal financial statements, however impact how or what information may be disclosed in the notes to the financial report.

Areas where amendments were requested in 2013–14, related to the following.

AASB 13 Fair Value Measurement

The 2013–14 financial year was the first year that water entities were required to apply the requirements of AASB 13 Fair Value Measurements. It is encouraging to note that water entities prepared reasonable first drafts of the newly required disclosures.

Amendments were requested by VAGO to ensure the draft financial reports captured all significant aspects of the disclosure requirements, such as the contents and classification of assets in the fair value hierarchy, commentary on the valuation techniques applied and detail around significant unobservable inputs used to value assets.

As the understanding of AASB 13 evolves in subsequent years, further clarification as to the requirements of the standard will occur, and note disclosures will be further enhanced.

Financial Reporting Direction 11A Disclosure of ex-gratia expenses

The former Minister for Finance updated Financial Reporting Direction 11A Disclosure of ex-gratia expenses, which became applicable from 1 July 2013. In particular, the definition of an ex-gratia payment was expanded to be a 'voluntary payment of money or other non-monetary benefit—e.g. a write off—that is not made either to acquire goods, services or other benefits for the entity or to meet a legal liability, or to settle or resolve a possible legal liability of or claim against the entity'.

As a result of the change in the definition of ex-gratia expenses, some water entities were required to make ex-gratia disclosures in their 2013–14 financial report. There were a number of water entities that did not initially disclose ex-gratia expenses in line with the requirements of Financial Reporting Direction 11A.

Commitments for expenditure

A number of water entities were required to make material disclosure adjustments relating to inaccurate and/or incomplete commitment disclosures. This also occurred in 2012–13. These errors highlight that improvements can still be made to the processes adopted by water entities to capture and calculate their commitments disclosures.

AASB 119 Employee Benefits

AASB 119 Employee Benefits was revised for the 2013–14 reporting period. It clarified the requirement for the classification of short-term employee benefits and amended measurement and disclosure requirements for superannuation defined benefit obligations.

As a result of these changes, water entities were required to assess the materiality of such changes to financial reports, disclose the resultant impact in their accounting policy note, and where relevant, restate prior year comparatives. Some water entities did not initially disclose the impact on their financial reports appropriately.

Other disclosure amendments

Adjustments were required to be made by some water entities, to specific note disclosures—in some instances these disclosures were either incomplete or inaccurate, or contained disclosure of items irrelevant to the entity. These specific disclosures related to:

- accounting policies

- financial risk management policies and objectives

- financial instrument disclosures

- contingent assets and liabilities

- related party disclosures

- executive officer remuneration

- subsequent event disclosure.

All amendments were adjusted prior to the completion of the financial reports.

We recommend that water entities identify at an early stage and understand the requirements that stem from financial reporting changes, either made by the Australian Accounting Standards Board and/or the Minister for Finance, to enable entities to adequately address disclosure requirements in a timely manner and prior to year end.

Prior-period errors

An entity may become aware of an error that occurred in a prior period when preparing their current year financial report. Errors can arise in respect to the recognition, measurement, presentation or disclosure elements of a financial report, and can occur for a number of reasons, from process driven failings to unintentional omissions.

Under AASB 108 Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors, these prior-period errors are to be corrected in the comparative information presented in the financial report for the subsequent period.

Four of the 19 water entities identified errors relating to prior periods while preparing their financial reports for the 2013–14 reporting period. These errors related to:

- inappropriate recognition and measurement of assets

- inadequate tax effect accounting

- untimely recognition of developer contributed assets

- untimely capitalisation of works in progress.

Relevant restatements and associated disclosures were included in the financial reports, in accordance with Australian Accounting Standards.

2.3.2 Timeliness

Timely financial reporting is key to providing accountability to stakeholders and enables informed decision-making. The later reports are produced and published after year end, the less useful they are. Entities preparing financial reports under the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA) are required to finalise their audited report within 12 weeks of the end of the financial year. Their annual reports, containing the audited financial report, should be tabled in Parliament within four months of the end of the financial year.

Appendix D sets out the dates the 2013–14 audit reports were issued on the certified financial reports.

All 19 water entities met the legislated time frame in 2013–14, as was the case in 2012–13. The average time taken by the 19 water entities to finalise their 2013–14 financial reports was 8.8 weeks which was marginally greater than the prior period—8.4 weeks in 2012–13.

2.3.3 Better practice

An assessment of the quality of financial reporting processes was conducted against better practice criteria, detailed in Appendix B, using the following scale:

- non-existent—function not conducted by the entity

- developing—partially encompassed in the entity's financial reporting preparation processes

- developed—entity has implemented the process, however, it is not fully effective

- better practice—entity has implemented effective and efficient processes.

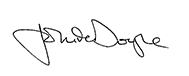

The results are summarised in Figure 2A.

Figure 2A

Results of assessment of financial report preparation

processes

against better practice elements

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Adopting the better practice elements can mitigate significant delays and additional costs in the finalisation of the audit. Unaddressed, these elements can jeopardise an entity's ability to meet legislated time lines and cause unnecessary cost increases due to the need for rework.

While most elements were developed with some entities having achieved better practice, the most significant elements to be addressed by water entities are:

- the preparation and quality of shell statements

- conducting materiality assessments

- preparing analytical reviews.

The regional urban and rural water entities, in particular, place heavy reliance on the Puddle Regional Water Corporation Model General Purpose Financial Report (Puddle) to assist in preparing their shell and draft financial reports annually.

Puddle presents example disclosures for a regional urban water entity. Puddle is prepared by the Victorian Water Industry Association (VicWater), an association of which all 19 water entities are members.

During the 2013–14 financial year, the planning process for Puddle did not occur until quite late, meaning that a draft version of the model financial statements was not available to water entities until July 2014. This was too late in the reporting period for water entities to prepare adequate shell financial statements, which are usually prepared in May. This caused delays in the year-end financial report preparation process and increased disclosure amendments requested by VAGO at year end.

It is imperative that water entities discuss the timing of the release of Puddle with VicWater, to ensure that it is available in sufficient time for water entities to consider and assess key financial reporting changes and to collate appropriate information to incorporate any changes in reporting requirements to shell statements.

We understand that in October 2014, the water entities and VicWater have proactively commenced discussions on the release of Puddle, to ensure that the timing occurs significantly earlier in the 2014–15 reporting period.

2.4 Internal control weaknesses

Effective internal controls help entities to reliably and cost-effectively meet their objectives. Strong internal controls are a prerequisite for the delivery of reliable, accurate and timely external and internal financial reports.

In our annual financial audits we focus on the internal controls relating to financial reporting and assess whether entities have managed the risk that their financial reports will not be complete and accurate. Poor internal controls diminish management's ability to comply with relevant legislation, and increase the risk of fraud and error.

The governing body of each water entity is responsible for developing and maintaining internal controls that enable:

- preparation of accurate financial records and other supporting documentation

- timely and reliable external and internal reporting

- appropriate safeguarding of assets

- prevention and detection of errors and other irregularities.

- internal control weaknesses commonly identified across the 19 water entities in 2013–14

- analysis of the status of internal control weaknesses identified in prior period audits.

Commonly identified internal control weaknesses or financial reporting issues

During the 2013–14 reporting period, audit teams identified 90 internal control weaknesses or financial reporting issues, and one process improvement matter, which were reported to those charged with governance and to audit committees. Figure 2B shows the number of issues identified by risk rating.

Figure 2B

Internal control weaknesses or financial reporting issues

identified during 2013–14, by risk rating

Risk rating |

Number of issues identified |

|---|---|

High |

9 |

Medium |

31 |

Low |

50 |

Process improvement |

1 |

Note: The criteria for high-, medium- and low-risk ratings, or a process improvement issue are explained in Appendix C.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The common areas requiring improvement to controls or financial reporting processes were:

- information technology

- payroll and provisions

- monitoring, maintenance and accounting for fixed assets

- preparation and review of general ledger reconciliations.

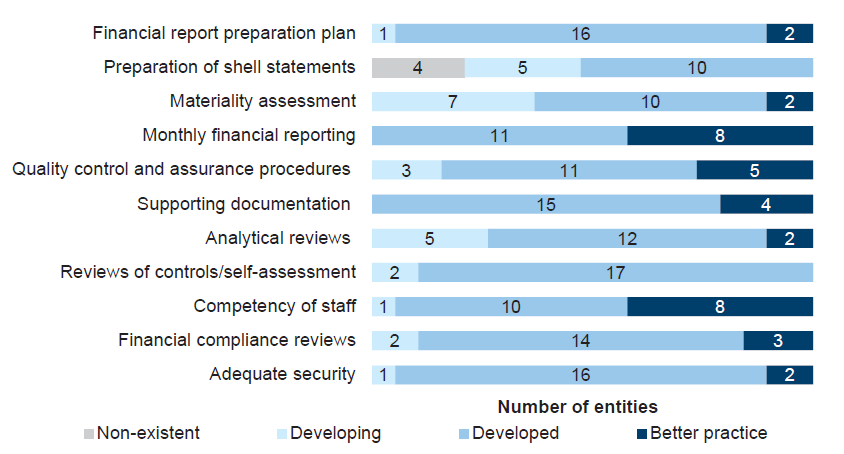

Figure 2C sets out the financial areas and systems in 2013–14.

Figure 2C

Occurrence of internal control weaknesses or financial reporting issues

by financial area and system

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Information technology

Information technology (IT) controls protect computer applications, infrastructure and information assets from a wide range of security and access threats. They promote business continuity, minimise business risk, reduce the risk of fraud and error, and help meet business objectives.

There is extensive reliance on IT across the water industry, and systems are continually upgraded and replaced to improve information management and the quality of services provided to the community. With the implementation of new IT, the upgrade of existing systems and the continuing emergence of external threats, new security risks to the IT environment can arise regularly.

Information held by water entities about employees, customers and suppliers, and the financial and operational aspects of the business, can be highly sensitive. It needs to be protected from unauthorised access, theft or manipulation.

Twenty-four IT control weaknesses were identified relating to:

- user access—13 issues

- software patches—five issues

- strategic frameworks—two issues

- third party assurance over the operation of controls—two issues

- business continuity management—one issue

- change management—one issue.

Payroll and provisions

Salaries and wages are a substantial business cost to water entities. Adequate internal controls should therefore exist over the processing and monitoring of salaries and related costs, to mitigate the risk of error, fraud or mismanagement.

The following payroll-related weaknesses were identified:

- lack of review of payroll pay-runs, payroll details, payroll exception reports and termination payments—six issues

- excessive annual leave—two issues

- lack of segregation of duties—one issue

- on-cost rates were not up to date—one issue

- staff approving payroll payments who have not been formally delegated the responsibility to do so—one issue.

Monitoring, maintenance and accounting for fixed assets

Water entities have substantial fixed assets including infrastructure, land, buildings and plant and equipment. The assets need to be appropriately recorded and maintained, and their condition and use monitored, so that decisions can be made about whether they are appropriately valued and when they need to be replaced. Inadequate recording and monitoring of assets can lead to their misappropriation and misplacement, or trigger material misstatements in the financial report.

Weaknesses were identified relating to:

- untimely capitalisation of fixed assets—four issues

- lack of clarity regarding fixed asset policies or classification—three issues

- untimely conduct of condition assessments of assets—one issue

- inadequate records managements of documentation to support capital projects—one issue

- incorrect data input into the fixed asset register—one issue

- inappropriate level of access provided to staff to the fixed asset register—one issue.

Preparation and review of general ledger reconciliations

A financial report is generally prepared based on information captured by the entity's general ledger, with key balances within the general ledger often supported by information recorded in subsidiary ledgers such as accounts payable, billings, fixed assets and payroll systems. Periodic reconciliation of the general ledger with the subsidiary ledger balances is vital to confirm the completeness and accuracy of data.

Timely preparation and independent review of key account reconciliations decreases the risk that errors may go undetected or may not be resolved in a timely manner, both of which can adversely affect the accuracy of periodic financial reporting.

Issues relating to key account reconciliations were identified at eight of the 19 water entities, comprising two metropolitan, five regional urban and one rural water entity. The key issues identified were:

- reconciliations not prepared and/or independently reviewed in a timely manner—eight issues

- long outstanding unreconciled amounts—three issues.

Action on issues identified in prior-year audits

Internal control weaknesses and financial reporting issues reported to management and the governing body should be actioned and resolved in a timely manner.

Ninety-two issues were raised across the 2011–12 and 2012–13 reporting periods, which were still unresolved at the commencement of the 2013–14 reporting period. However, it is pleasing to note that only 15 of these remained unresolved at the end of 2013–14. One of these was rated as high risk, eight were rated medium risk and the remaining six were rated as low risk.

The unresolved control weaknesses and financial reporting issues were reported to management at eight of the 19 water entities. The weaknesses were spread across metropolitan, regional urban and rural water entities.

The resolution of 77 of the previously identified and reported internal control weaknesses and financial reporting issues during 2013–14 suggests that water entities are aware and managing the risk of material misstatement. We encourage a continued focus on the resolution of prior-year internal control weaknesses and financial reporting issues.

Recommendations

That water entities:

- continue to work closely with their industry body to ensure that the preparation and release of the industry's model financial report occurs earlier

- identify, at an early stage, and understand the requirements that stem from financial reporting changes by the Australian Accounting Standards Board and/or the Financial Reporting Directions

- further refine their financial reporting processes by conducting materiality assessments, preparing analytical reviews and preparing quality shell financial statements.

3 Performance reporting

At a glance

Background

In the past only 16 of the 19 water entities were required to prepare audited performance reports, however the release of Financial Reporting Direction (FRD) 27C Presentation and Reporting of Performance Information during 2013–14 extended this requirement to all water entities. This Part covers the results of the 2013–14 audits of water entity performance reports. Currently, we form an opinion on whether the performance indicators fairly represent the entity's actual performance. We do not form an opinion on the relevance or appropriateness of the reported performance indicators.

Conclusion

Parliament can have confidence in the fair presentation of all 19 performance reports, as all received unqualified audit opinions for 2013–14.

Findings

Improvement has occurred in performance reporting during 2013–14, when compared to prior years, largely due to the efforts of an industry working group and the former Department of Environment and Primary Industries. Nevertheless, further improvement is still required to the reporting of targets, variance explanations, lay out and supporting calculations of performance reports. Water entities should also continue to improve performance reporting processes, such as preparing shell statements and enhancing quality control and assurance procedures.

Recommendations

- That the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning:

- engage early with water entities to ensure that all applicable indicators are included in the corporate plans of water entities

- enhance the guidance supporting the Ministerial Reporting Direction (MRD) 01 Performance Reporting, to address issues encountered in 2013–14.

- That water entities critically assess the way they calculate and explain variances ensuring performance reports fully address the requirements of the MRD 01.

3.1 Introduction

This Part covers the results of the audits of the 2013–14 performance reports of 19 water entities. This is the first year that all 19 water entities were required to prepare audited performance reports.

In 2012–13, 16 of the 19 water entities were required to prepare such reports, however the release of Financial Reporting Direction (FRD) 27C Presentation and Reporting of Performance Information during 2013–14 extended the requirement to all water entities.

On 4 December 2014, the Governor in Council, under section 10 of the Public Administration Act 2004, made an order to change the name of the Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI) to the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP).

3.2 Conclusion

Parliament can have confidence in the fair presentation of all 19 performance reports as they received unqualified audit opinions for 2013–14.

3.3 Performance reporting framework

FRD 27C Presentation and Reporting of Performance Information was issued in May 2014. It replaced FRD 27B Presentation and Reporting of Performance Information, effective for reporting periods commencing 1 July 2013. It was updated to capture all 19 water entities and to provide definitions for the 'Responsible Portfolio Minister' and 'Targets'.

During 2012–13, the former DEPI and a water industry performance reporting working group reviewed a suite of proposed key performance indicators (KPI). After consultation and feedback between the former DEPI and the water entities, a number of financial and non-financial indicators were agreed upon and reported against in 2013–14.

The water entities were required to reflect the agreed KPIs in their 2013–14 corporate plans which were submitted to the former DEPI. There was an expectation by the former DEPI that the corporate plans would contain all KPIs to be included in the 2013–14 performance reports and that targets would be set for all indicators.

Ministerial Reporting Direction (MRD) 01 Performance Reporting was issued on 20 May 2014 pursuant to section 51 of the Financial Management Act 1994. MRD 01 specified the format, content, and indicators to be included in performance reports.

On 9 July 2014, the former Minister for Water approved an addendum to MRD 01 to allow the aggregated reporting of results against targets for two non-financial KPIs—water quality compliances and effluent reuse. This addendum was issued as a number of water entities had not set disaggregated targets for these two KPIs in their 2013–14 corporate plans, and as such would not have been able to prepare their performance report in line with the originally released MRD 01.

It is important that early engagement occurs between DELWP and water entities to ensure that all water entities are made aware of the required performance indicators and set appropriate targets for these indicators in their corporate plans.

Figure 3A summarises the number and nature of indicators by water entity type.

Figure 3A

Key performance indicators by sector

Water sector |

Financial indicators |

Non-financial indicators |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

Metropolitan |

|||

|

7 |

15 |

22 |

|

7 |

11 |

18 |

Regional urban |

7 |

11 |

18 |

Rural |

7 |

5 |

12 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-Generals Office.

Appendix F provides further detail on the financial and non-financial indicators for each entity type.

3.4 Audit opinions issued

Unqualified audit opinions were issued on all 19 performance reports for 2013–14.

Our annual attest audit on the performance report of 19 water entities is currently limited to an opinion on whether the actual results reported are fairly presented and comply with legislative requirements. We do not form an opinion on the relevance or appropriateness of the reported performance indicators.

3.5 The quality of performance reporting

Overall the water entities produced reliable information in performance reports.

3.5.1 Timeliness of reporting

Performance reports are generally prepared and finalised in conjunction with financial reports and the common time line for their preparation is provided at Part 2.

Appendix D sets outs when the performance report for each entity was finalised.

3.5.2 Accuracy

In 2013–14:

- six of the 19 performance reports included key performance indicators where 2012–13 comparative results were not disclosed

- five of the 19 performance reports included indicators where targets were reported as 'not applicable', compared with nine of 16 in 2012–13.

Further, some water entities did not initially:

- calculate significant variations correctly—10 of the 19 water entities

- present and disclose the performance reports in line with the requirements of the updated MRD 01—four of the 19 water entities

- provide appropriate commentary to explain significant variations between targets and actual performance or between prior year and current year actual performance

- state what steps management have taken or planned to take to reduce variations against prior year and target—16 of the 19 water entities. The requirement to include this explanation against prior year results was new for 2013–14.

Of the five performance reports that contained key performance indicators without targets:

- Two performance reports included the mandated indicators from MRD 01 but reported the target as 'not applicable' as the indicator did not relate to the entity's operations—they were only included in the report as it was required under MRD01

- Three performance reports disclosed 'not applicable' against some key performance indicators, as no target was set in the 2013–14 corporate plan, approved by the former DEPI. The targets were either only set for 2014–15 onwards, or it had been agreed not to be included. The reporting of 'not applicable' against targets in the performance reports demonstrates a disconnect between the corporate planning process of water entities and the sector's performance reporting obligations.

The six performance reports that contained no comparative results for the key performance indicators did so because:

- the relevant entities did not track such information or data to allow for comparative results to be reported, as it was not a requirement to previously report

- the indicator did not relate to the entity's operations—it was only included in the report as it was required under MRD 01.

The MRD required water entities to provide explanations for all significant variances and to set out what steps management have taken or planned to take to reduce variations against the prior year and the target. It would be beneficial if water entities were only required to provide details of steps management have taken or planned to take with respect to unfavourable variances—such measures are not needed when considering favourable results.

Improvements to the consultation process between the water entities and DELWP are required, in terms of the overall requirements of, and key changes made to, MRD 01 annually, to ensure that water entities understand the full extent of the disclosures required and comply.

Water entities should also critically assess the explanations they provide for material variations to ensure that they addresses the requirements of MRD 01.

Inconsistencies were also identified in the way in which performance indicators were calculated against the required calculation format outlined in MRD 01. DELWP should consider providing further guidance on how each key performance indicator is to be calculated.

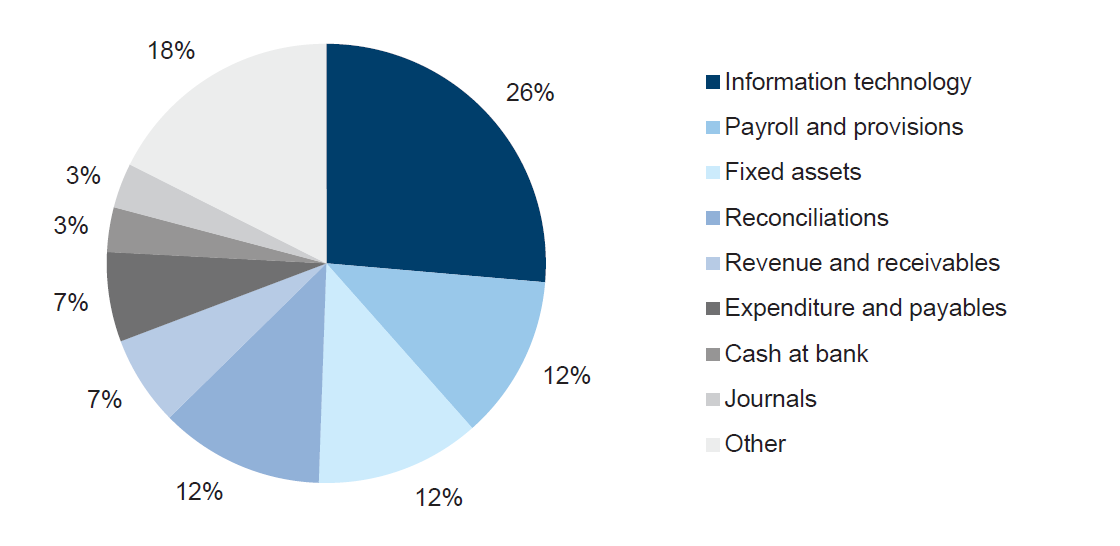

3.5.3 Better practice

Performance reports were assessed against better practice criteria, as per the framework detailed in Appendix B. The rating scale used in our assessment is consistent with that outlined in Part 2 of this report.

Figure 3B

Results of assessment of performance report preparation processes

against better practice elements

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure 3B shows that improvement is needed to performance reporting processes in the following areas:

- the development of a performance report preparation plan

- the preparation of shell statements

- regular performance reporting

- quality control and assurance procedures

- performance compliance reviews.

Performance reporting processes adopted by the water entities are not as mature or developed as those applied to financial reporting.

The early preparation of shell performance reports prior to year end could help reduce the number of errors in performance reports. This can provide water entities with the opportunity to reduce costs and achieve efficiencies during the year end process. This, however, is contingent upon the timing of the release of MRD 01 by DELWP.

3.6 Elements of effective performance reporting

The Audit Act 1994 provides the Auditor-General with a mandate to audit performance indicators in the report of operations of an audited entity to determine whether they:

- are relevant to the stated objectives of the entity

- are appropriate for the assessment of the entity's actual performance

- fairly represent the entity's actual performance.

Our annual audit on the performance report of water entities is currently limited to an opinion on whether the actual results reported are presented fairly and in compliance with the legislative requirements.

In our Water Entities: Results of the 2010–11 Audits report we indicated our intention to begin expressing opinions on the relevance and appropriateness of the indicators. In our Water Entities: Results of the 2012–13 Audits report we provided an update on progress made by the former DEPI and a water industry working group in developing a contemporary framework to facilitate the inclusion of relevant and appropriate financial and non‑financial indicators in the sector's future performance reports.

3.6.1 Progress in 2013–14

The 2013–14 reporting period was the first year where a consistent pro-forma and detailed guidance existed for each water entity type via MRD 01, and where the majority of targets were set in the 2013–14 corporate plan process. Deficiencies were encountered with the reporting of targets, variance explanations, lay out and supporting calculations. Nevertheless, an improvement in performance reporting occurred when compared to prior years given the framework established.

The 2014–15 corporate plan process was finalised in June 2014, where targets have been set for performance indicators which are expected to be prescribed in the MRD 01 for 2014–15. Moving forward, it is intended that audit opinions on performance reports may conclude on the relevance and appropriateness of the performance indicators and whether they fairly present performance.

Recommendations

That the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning:

- engages early with water entities to ensure that all indicators—at an appropriate level of granularity—are included in the corporate plans of water entities

- enhances the guidance supporting the Ministerial Reporting Direction 01 Performance Reporting, to address issues encountered with the calculation of variances and the requirements of variance explanations.

That water entities:

- critically assess the way they calculate and explain variances ensuring performance reports fully address the requirements of the Ministerial Reporting Direction 01 Performance Reporting.

4 Financial results

At a glance

Background

This Part covers the financial results of the 19 water entities for the year-ended 30 June 2014.

Conclusion

The 19 water entities generated a net profit before income tax of $318.2 million for the year-ended 30 June 2014, an increase of $234.5 million, or 280 per cent, from the prior year. This was largely due to two metropolitan water entities reporting significantly higher profits as a result of higher water, sewerage and other prices, as approved by the Essential Services Commission, and higher water consumption.

The profitability of the 19 water entities will be impacted by higher finance costs in the future as a result of increased borrowings up to 30 June 2014, continued commitments to government such as taxes and levies, and honouring commitments from the former Fairer Water Bills initiative.

Findings

- Finance costs increased by $213 million, or 23.4 per cent, compared to the prior year.

- In 2013–14 dividends paid totalled $38.4 million, a decrease of $105.4 million, or 73 per cent, on 2012–13. This excludes a dividend payment by Melbourne Water on 31 July 2013 of $94.5 million relating to their 2011–12 final dividend.

- At 30 June 2014, the 19 water entities controlled $42 billion in total assets—$41.4 billion at 30 June 2013—and had total liabilities of $20.3 billion—$20.1 billion at 30 June 2013.

- Interest‑bearing liabilities increased by $148 million, or 1 per cent, during the year, predominantly due to increases in borrowings to finance the construction of infrastructure assets and other obligations.

- Total payments to the state by water entities in 2013–14 amounted to approximately $474.7 million, for the environmental contribution levy, tax, financial accommodation levy and dividends.

4.1 Introduction

Accrual-based financial reports enable an assessment of whether water entities generate sufficient surpluses from their operations to maintain services, fund asset maintenance/renewal and repay debt. Their ability to generate surpluses is subject to the regulatory environment in which they operate and their ability to minimise costs and maximise revenue.

An entity's financial performance is measured by its net operating result—the difference between its revenues and expenses. An entity's financial position is measured by reference to its net assets—the difference between its total assets and total liabilities.

4.2 Financial results

4.2.1 Financial performance

The 19 water entities are subject to the National Tax Equivalent Regime (NTER) administered by the Australian Taxation Office. NTER is an administrative arrangement that results in government-owned enterprises paying a tax equivalent to the state government.

Accordingly, we present their net results before and after income tax in this section.

Net result before income tax

The 19 water entities generated a combined net profit before income tax of $318.2 million for the year-ended 30 June 2014, an increase of $234.5 million, or 280 per cent, on the prior year. This was largely due to two metropolitan water entities reporting significantly higher profits as a result of higher water, sewerage and other prices, as approved by the Essential Services Commission (ESC), and higher water consumption.

Sector performance

All four metropolitan water entities reported a net profit in 2013–14.

The regional urban water entities, as a cohort, improved their performance. Though the number of water entities reporting losses remained the same—four in 2013–14 and 2012–13—overall, regional urban water entities reported a net profit before income tax of $18.0 million, compared with $6 million in 2012–13.

The two rural water entities continued to report losses in 2013–14.

Figure 4A shows the net profit or loss before income tax for each entity for the past two years.

Figure 4A

Net profit/(loss) before income tax, by water entity

Entity |

2013–14 ($ mil) |

2012–13 ($ mil) |

|---|---|---|

Metropolitan sector |

||

Wholesaler |

||

Melbourne Water |

131.9 |

(61.6) |

Retailer |

||

City West Water |

36.1 |

44.9 |

South East Water |

126.4 |

75.3 |

Yarra Valley Water |

66.0 |

66.6 |

Regional urban sector |

||

Barwon Water |

11.3 |

28.3 |

Central Highlands Water |

10.3 |

5.5 |

Coliban Water |

(6.7) |

(21.6) |

East Gippsland Water |

4.0 |

4.0 |

Gippsland Water |

4.9 |

4.4 |

Goulburn Valley Water |

2.5 |

2.6 |

GWMWater |

(15.1) |

(34.3) |

Lower Murray Water |

(3.8) |

(4.4) |

North East Water |

5.5 |

7.9 |

South Gippsland Water |

(0.4) |

(0.3) |

Wannon Water |

2.6 |

8.6 |

Western Water |

1.6 |

4.1 |

Westernport Water |

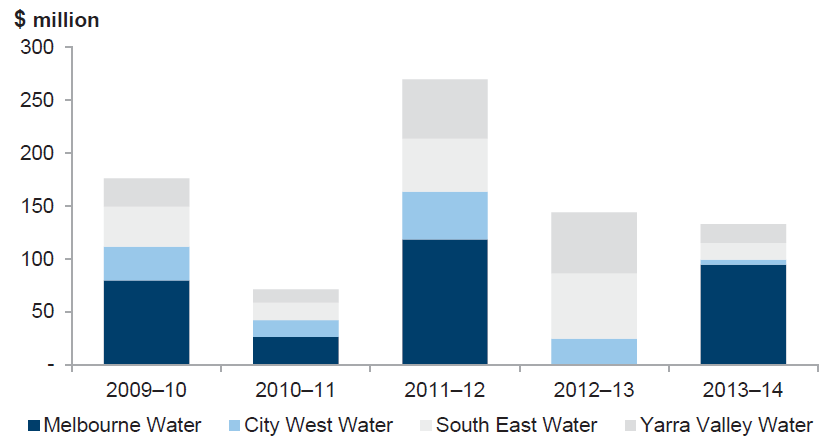

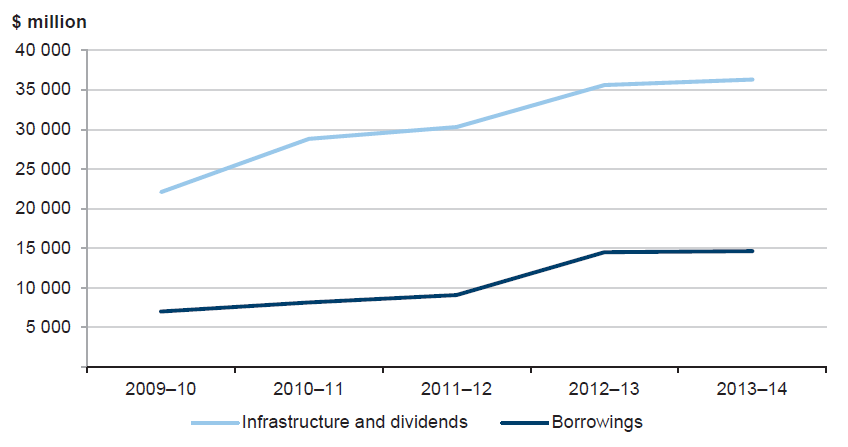

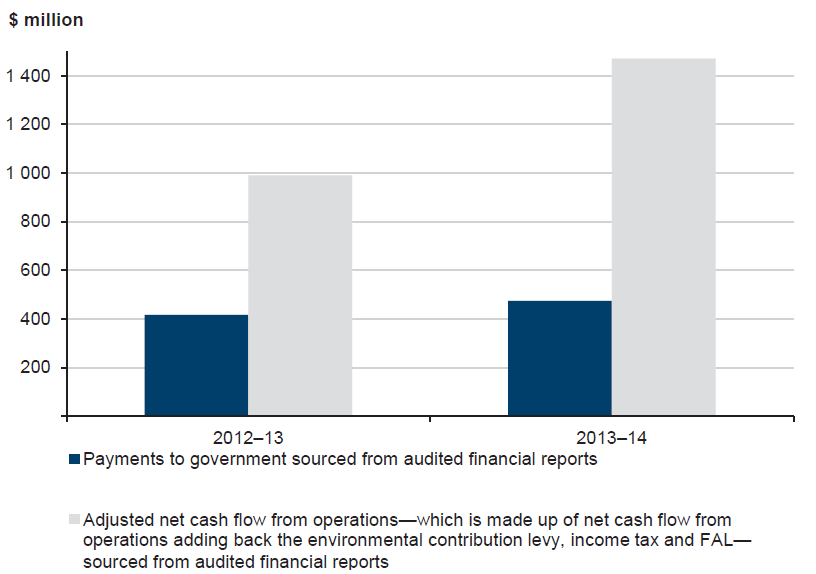

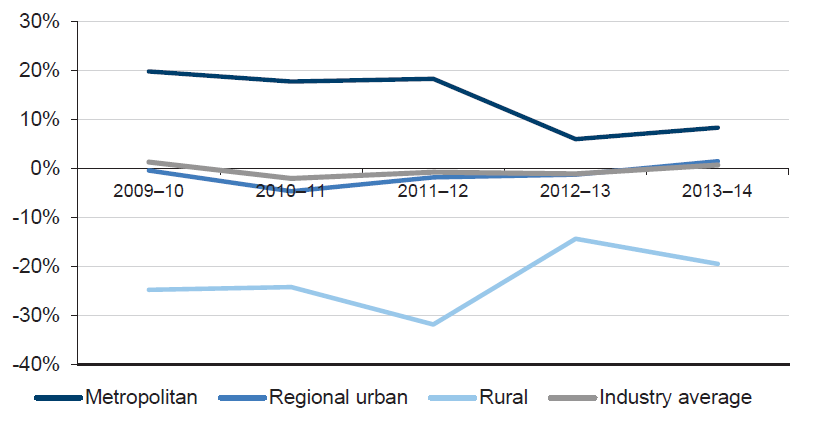

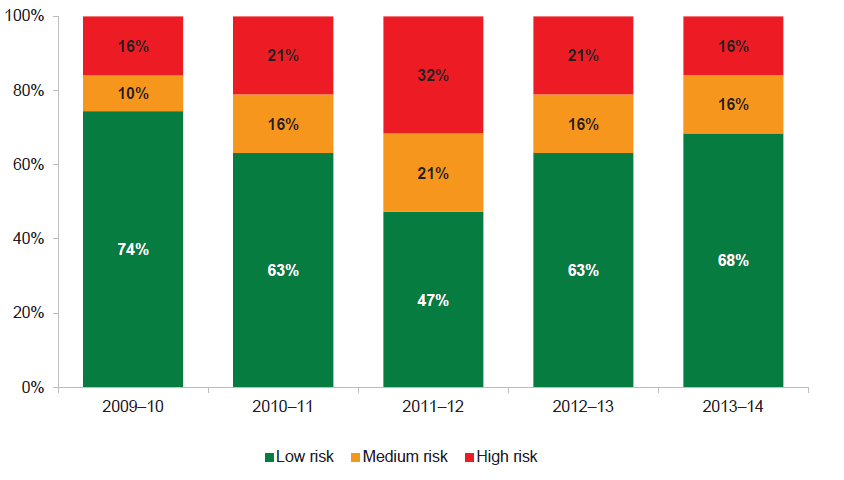

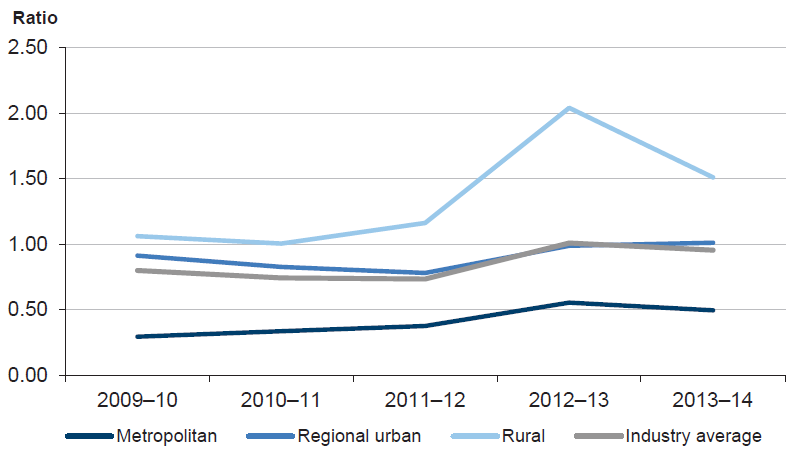

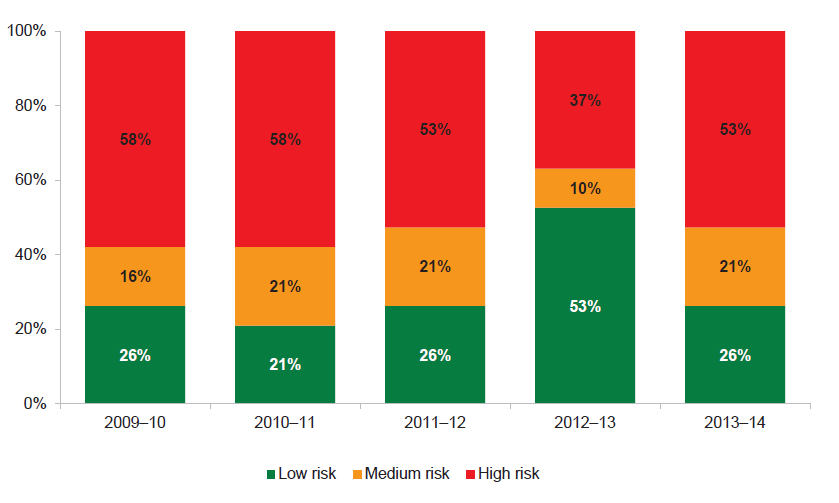

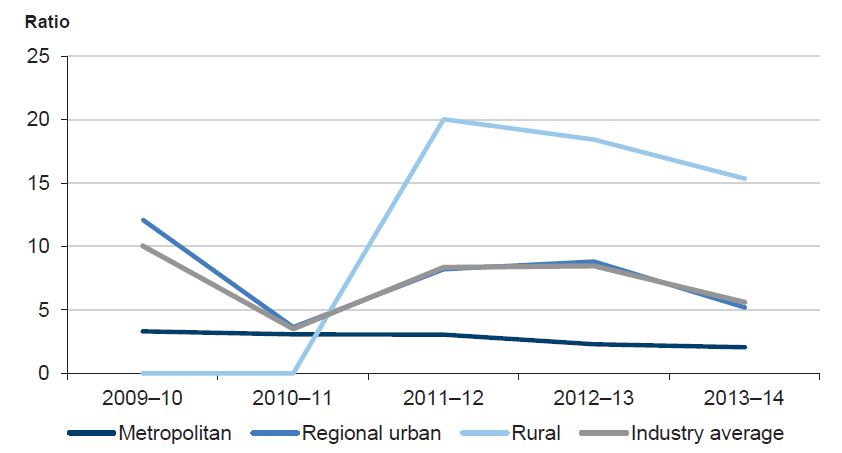

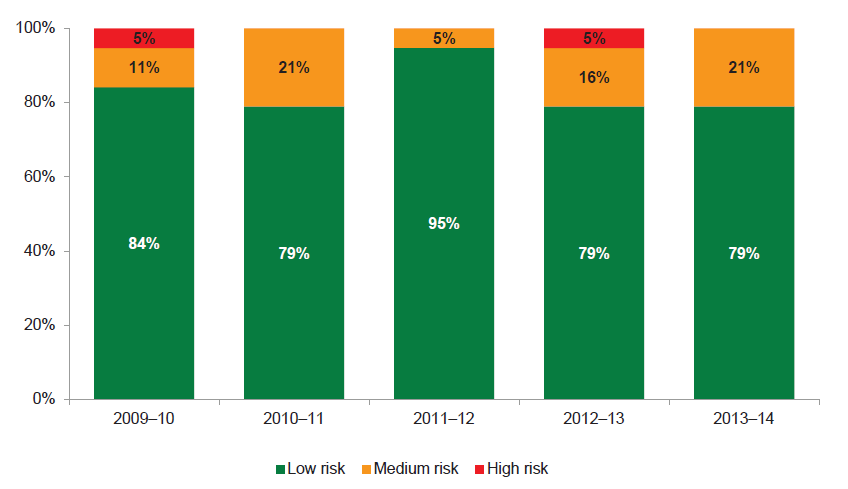

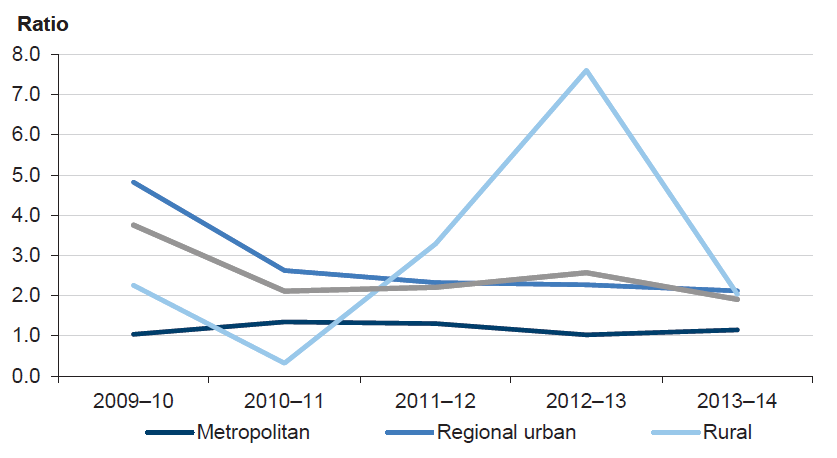

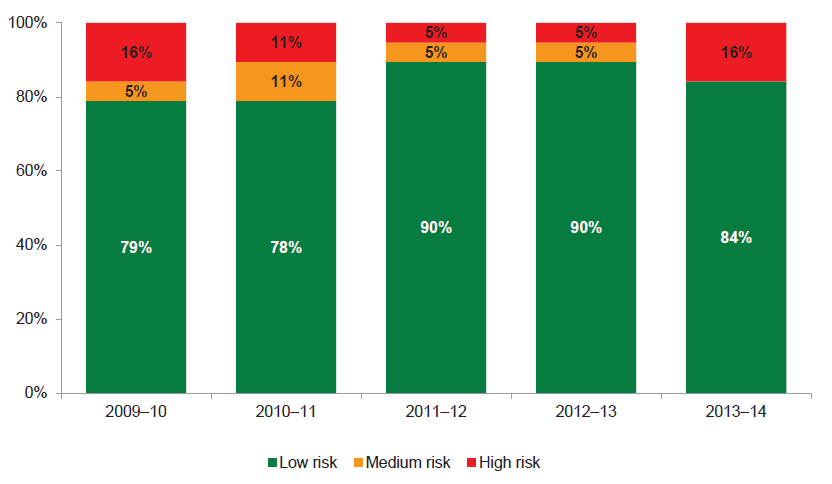

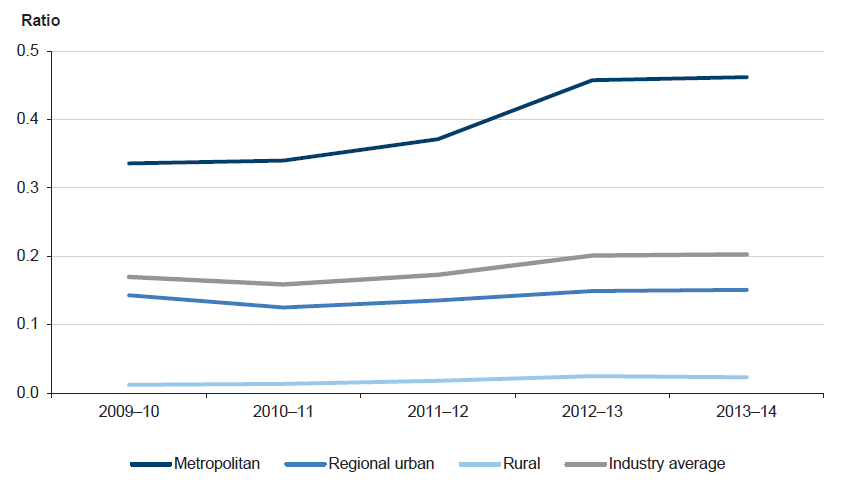

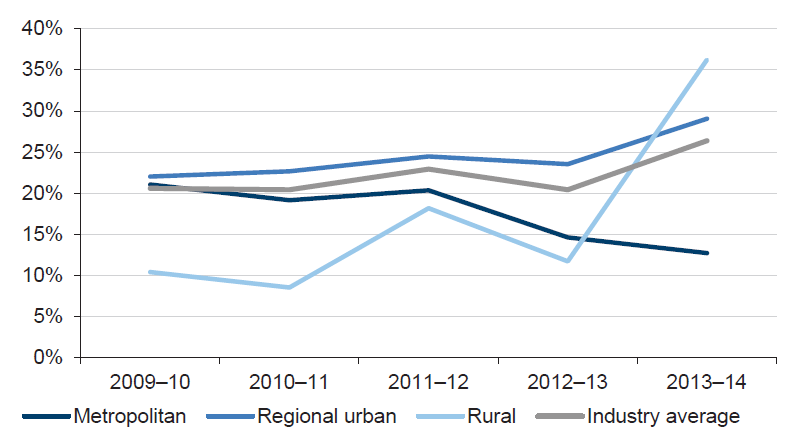

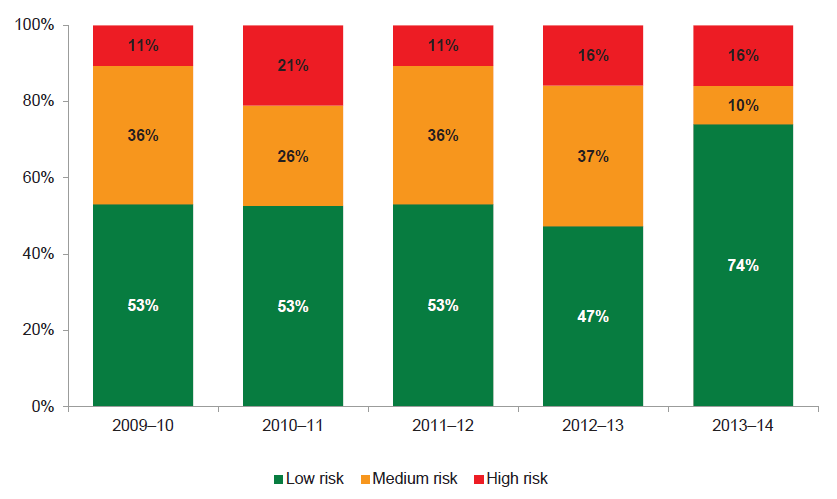

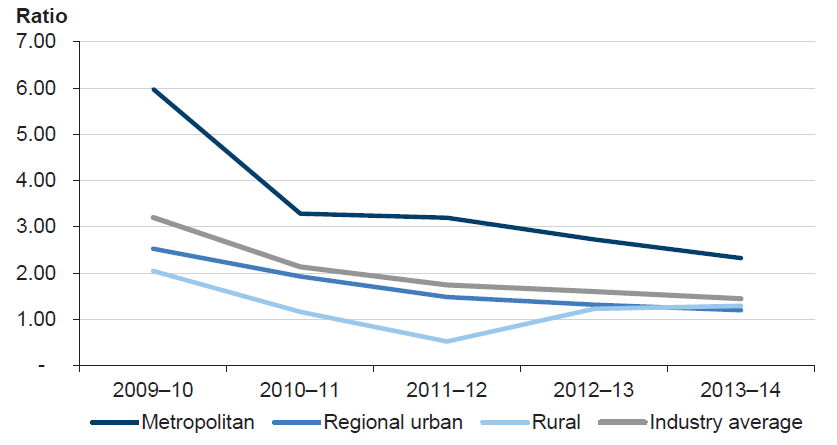

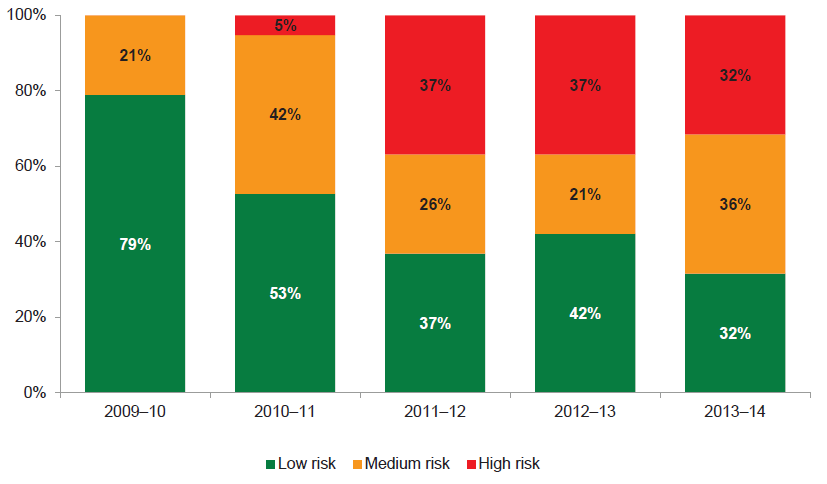

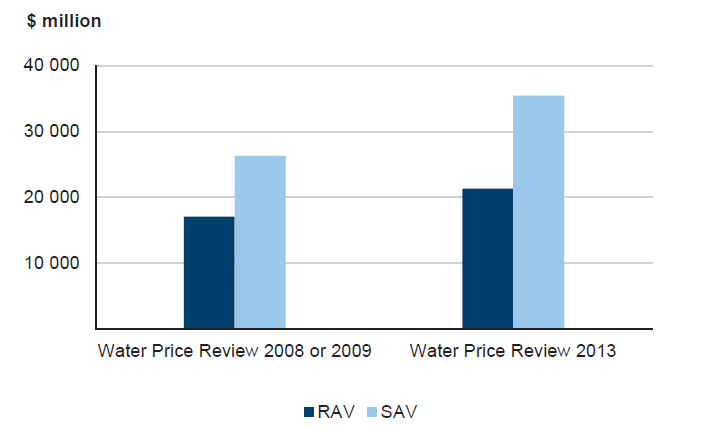

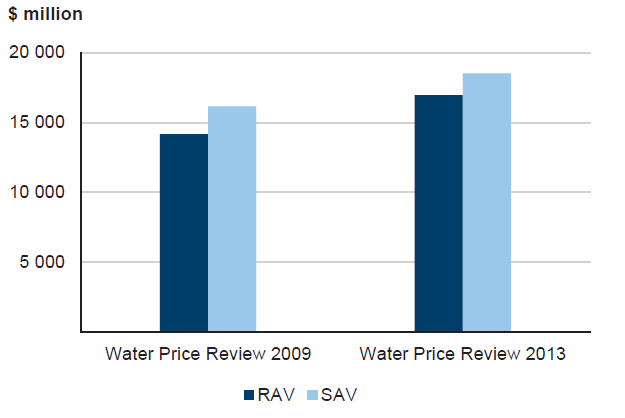

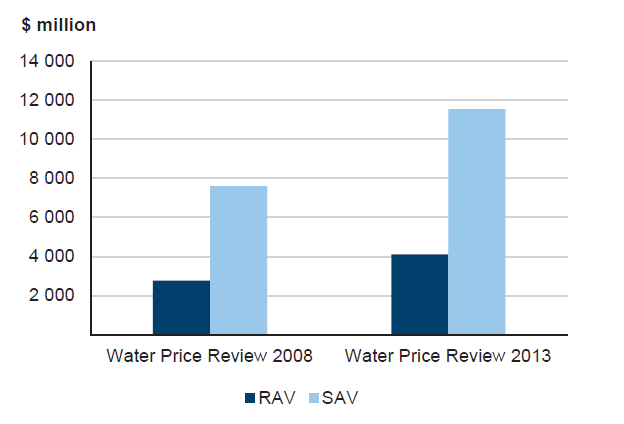

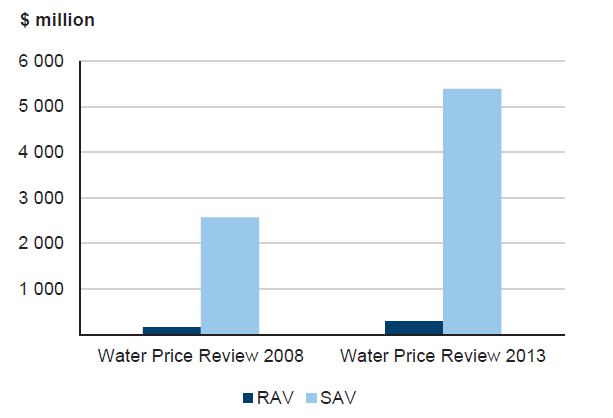

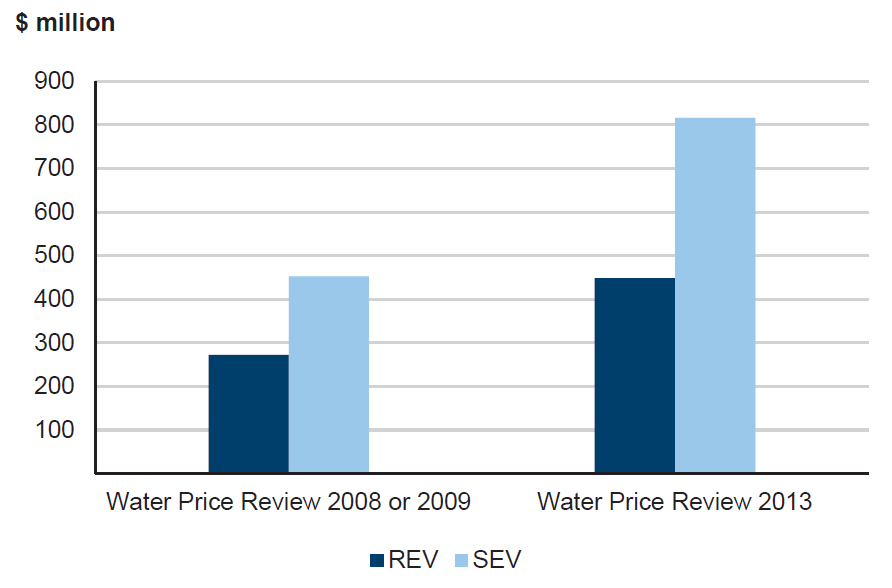

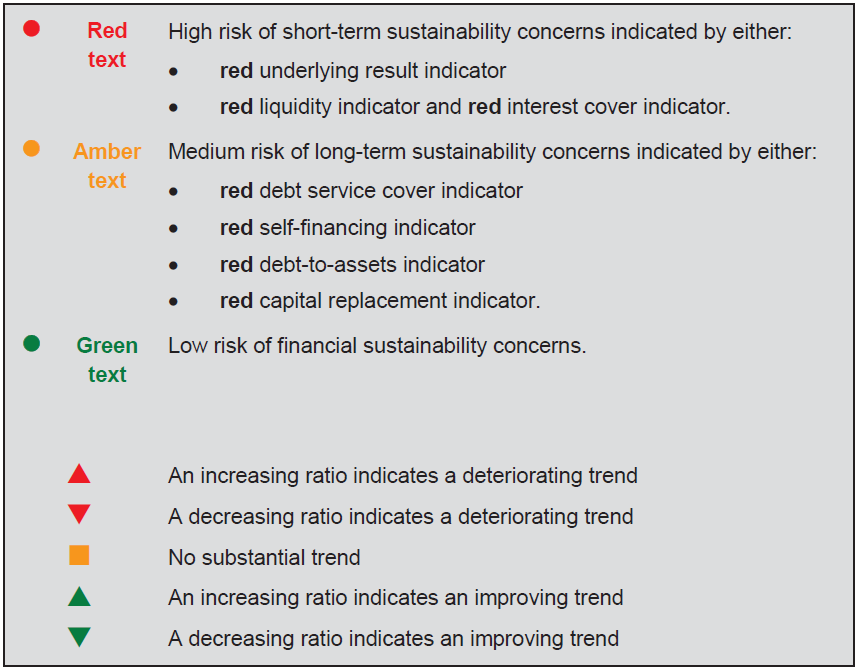

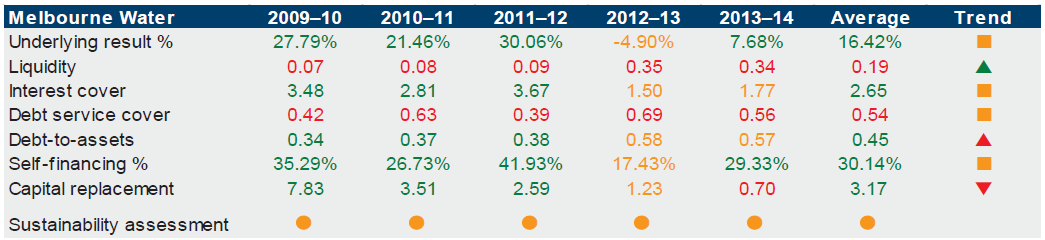

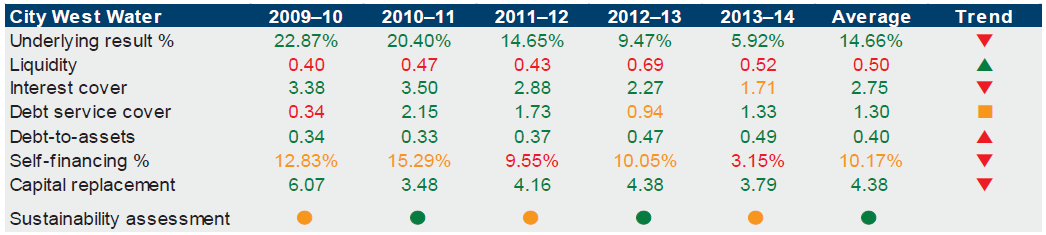

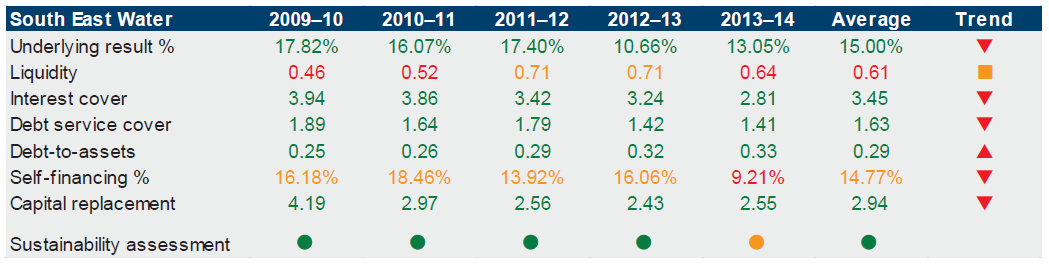

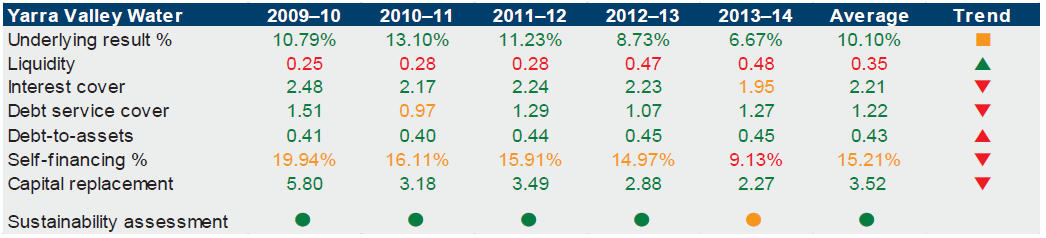

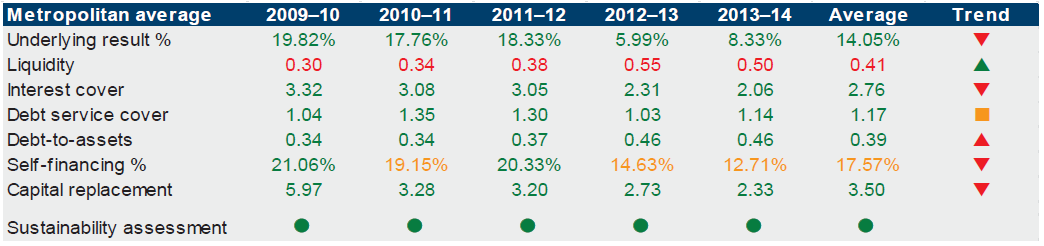

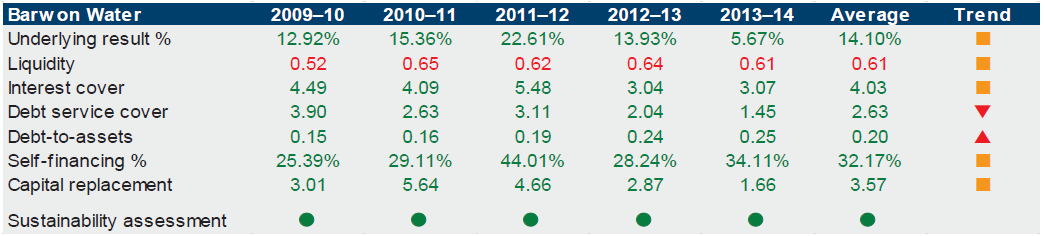

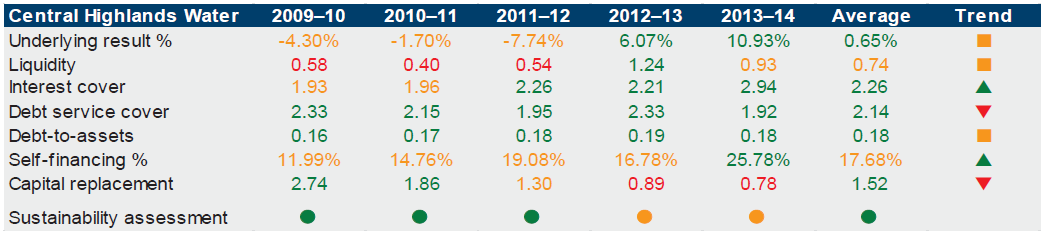

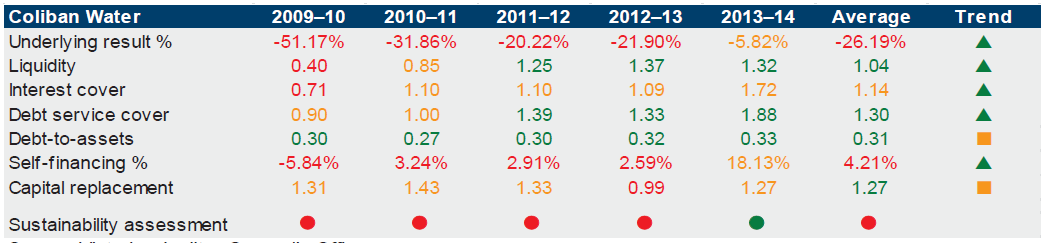

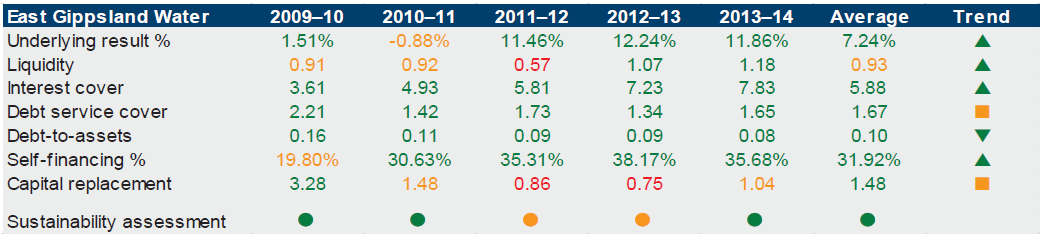

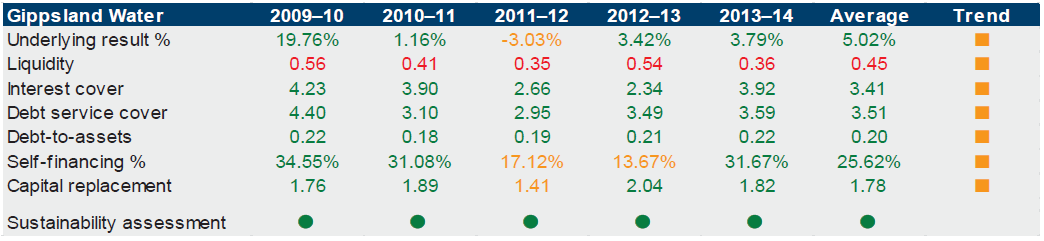

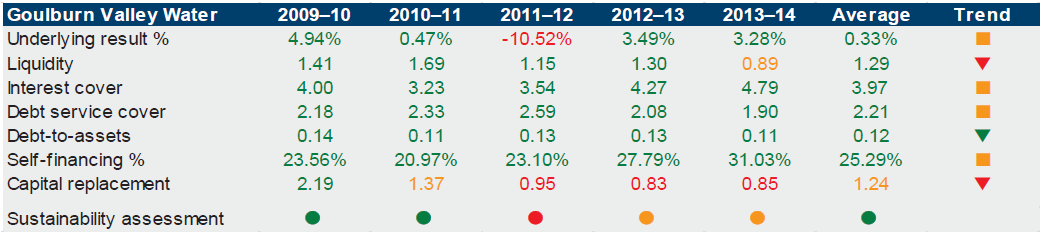

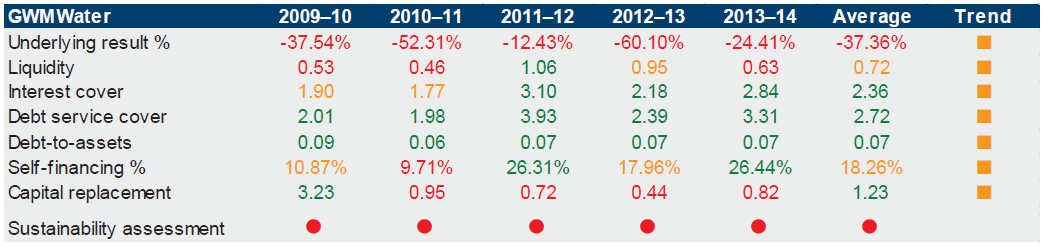

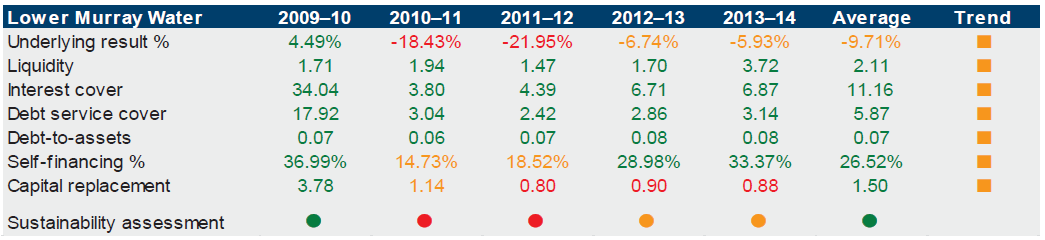

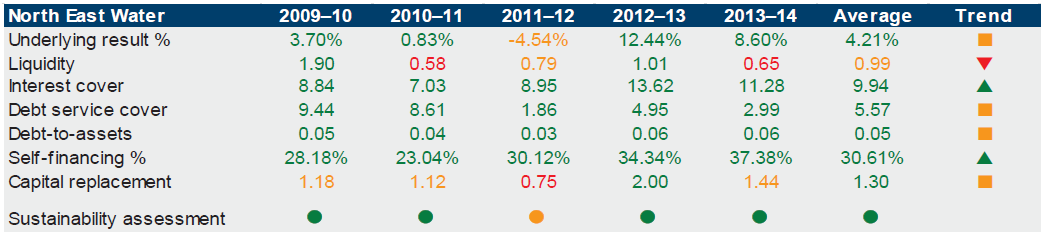

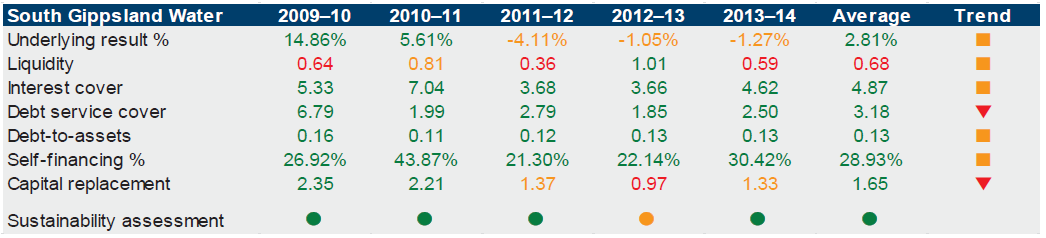

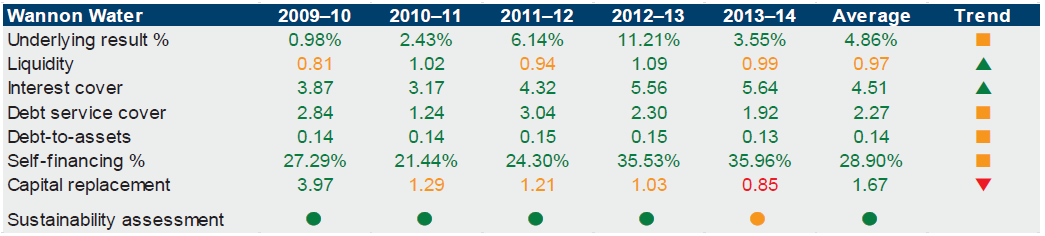

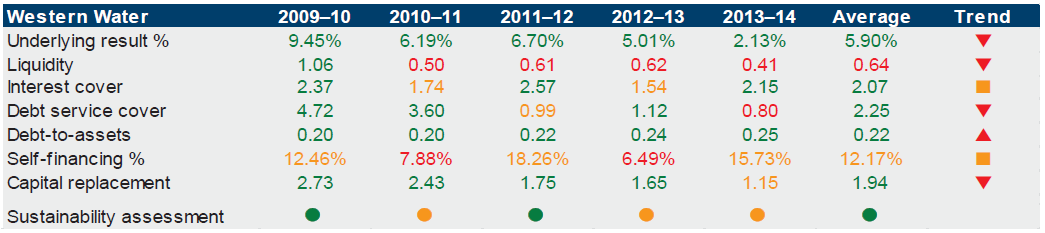

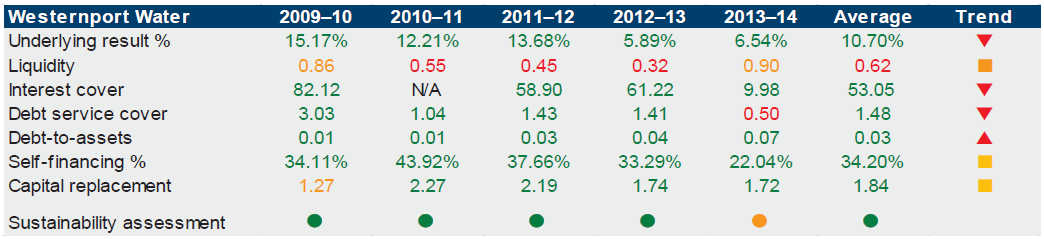

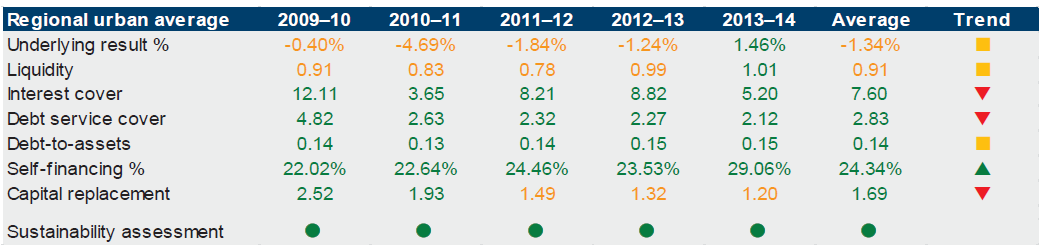

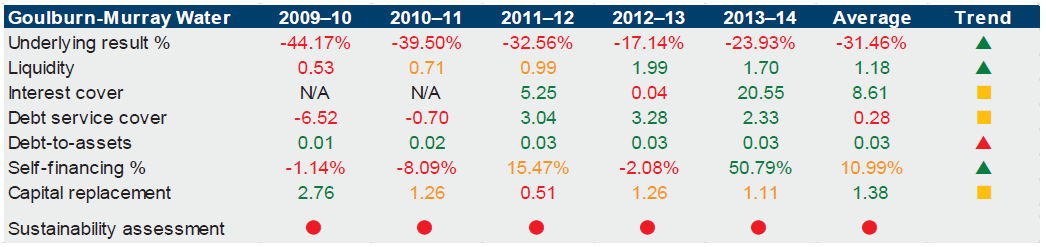

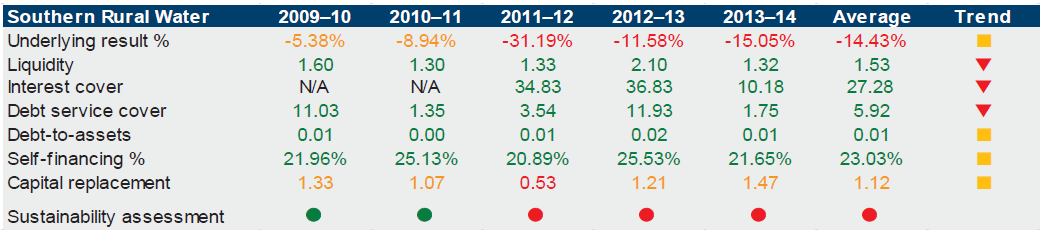

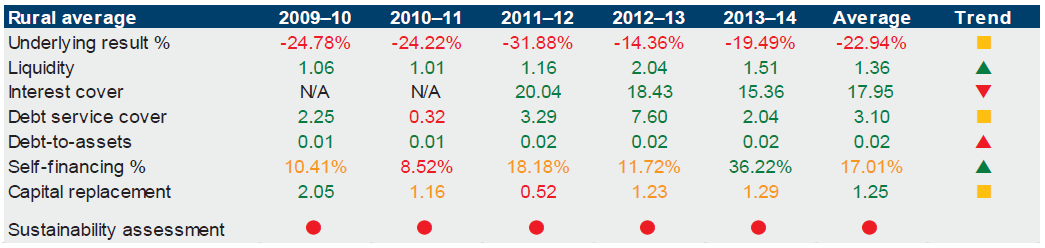

1.3 |