Auditor-General's Report on the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria: 2023–24

Report snapshot

About this report

In this report, we share outcomes of our audit on the state's financial report and our independent perspective on the state's financial outcomes and risks to fiscal sustainability.

Audit outcomes (Section 2)

The 2023–24 Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria (AFR) is free from material error and we issued an unmodified (clear) audit opinion on it.

We issued clear opinions on 28 of the 30 material entities’ financial reports.

We were unable to express an opinion on whether the distracted driver fines income reported by the Department of Justice and Community Safety (DJCS) was complete and therefore issued a modified opinion on its financial report.

We also continued to modify our audit opinion on the financial report of Victorian Rail Track (VicTrack) because of how it accounts for assets it leases to the Department of Transport and Planning (DTP).

These modifications did not impact our opinion on the AFR because:

- for DJCS, the matter was not material to the state's financial report

- for VicTrack, the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) made a central adjustment on consolidation of the state's financial report to correct the issue.

Financial outcomes for the general government sector and risks to fiscal sustainability (Section 3)

The general government sector (GGS) incurred another operating loss this year of $4.2 billion. This brings accumulated losses over the last 5 years to $48 billion. The government attributes $31.5 billion of these losses to its COVID-19 response and $16.5 billion to providing ongoing public services:

- Revenue was $8.4 billion higher compared to 2022–23 because of greater tax receipts from the COVID debt levy and improved economic conditions. The Transport Accident Commission (TAC) also paid the government a $1.1 billion dividend and the Australian Government paid $1.7 billion more in grant funding.

- Operating expenses increased by $3.7 billion compared to 2022–23 because of higher public sector employee costs and other operating expenses. Interest expenses on debt also increased by $1.7 billion due to new or refinanced borrowings at higher interest rates. The interest expense now makes up 6.1 per cent of the GGS operating revenue and is expected to increase to 8.8 per cent by 2027–28.

This year's GGS operating cash surplus of $2.6 billion included an unexpected $0.7 billion pass through grant from the Australian Government for local councils, paid at the end of the financial year. The pass-through grant was not paid out within the financial year.

The GGS fiscal cash deficit of $14.4 billion is expected to continue to 2027–28. This means the government's combined cash outlays on operating activities and its investment in capital projects remained greater than its operating cash inflows, which is a continuation of the last 8 years.

Prolonged operating losses and ongoing fiscal cash deficits are not financially sustainable, largely because they lead to higher debt levels than otherwise and indicate underlying structural risks.

The value of cumulative cost saving initiatives announced from 2019–20 to 2027–28 is now $9.0 billion, with $4.9 billion to be achieved over the next 4 years. Achieving these savings and maintaining current service levels will be challenging given several emerging financial risks.

GGS gross debt rose again this year at a pace faster than revenue and economic growth to $168.8 billion. It is projected to grow to $228.2 billion by 30 June 2028. The government’s present strategy is to manage debt levels relative to the state’s economy. In this regard, the government has committed to start reducing net debt to gross state product (GSP) in 2027–28.

Sound financial management is foundational to fiscal sustainability. A clear and well defined long term financial plan is required and integral to a robust and mature financial management framework.

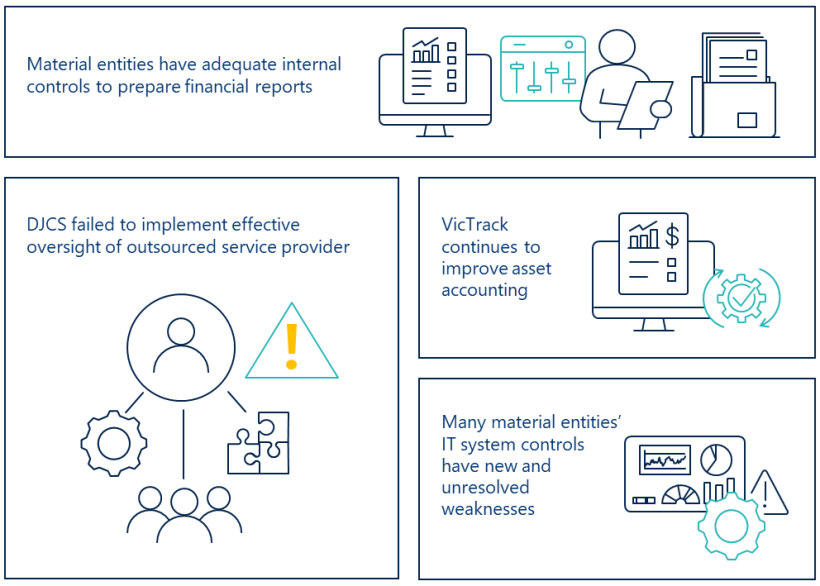

Key matters arising from our audits of material entities (Section 4)

We identified financial control weaknesses at some material entities that impact the reliability and usefulness of their financial reports.

We also continued to find significant weaknesses in information technology (IT) system controls across many material entities. Disappointingly, a number of prior-year IT control deficiencies remain unresolved, reflecting ongoing weaknesses in their control environments.

Key numbers: general government sector

Note: Numbers are rounded.

Source: VAGO.

Data dashboard

Interactive data dashboard for the Victorian general government sector (GGS)

This interactive dashboard enables you to:

- gain key insights about the state’s financial outcomes from our AFR Report

- immediately compare historical financial information with actual and forecast results.

It brings together current and historical information for the GGS reported in past state Budgets and the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria (AFR).

This dashboard is divided into 2 sections.

Explanatory section

In this section, we present key insights from the AFR report along with our independent perspectives on the GGS fiscal sustainability measures, key balances and transactions reported in the AFR for the GGS.

Exploratory section

This section enables you to immediately compare historical financial information with actual and forecast results, providing valuable insights. It includes projected Budget and forecast financial information derived from our audit of the AFR and the most recently tabled state Budget that we have reviewed.

Our recommendations

We consulted with the audited agencies and considered their views when reaching our conclusions. The agencies' full responses are in Appendix A.

This year's recommendations

| Recommendations | Agency response(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department of Treasury and Finance | 1

| Work with the government to:

| Noted | |

| 2 | Enhance its public reporting to demonstrate progress against saving initiatives and efficiency dividends outlined in the state Budgets and the realisation of their benefits (see Section 3). | Noted | ||

| Department of Premier and Cabinet | 3

| Undertake a post-implementation review of the 2022 machinery of government changes, including:

| Accepted | |

| Several material entities | 4

| Extending from our recommendation last year, we recommend relevant material entity chief financial officers:

| – | |

Follow-up on prior-year recommendations

| Recommendations | Agency response(s) | 2023–24 update | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department of Treasury and Finance | 1 | Consider why quality issues with information provided by material entities arise and determine whether further training and guidance are required. | Accepted | Quality issues with financial information continue to exist. Refer to Section 2 of the report for an extended recommendation on this. | |

| 2 | Work with the government to set specific targets and precise timing of achieving its key financial measures and targets of net debt to gross state product and interest expense to revenue. | Noted | – | ||

| 3 | Work with the government to outline its debt management strategy including when and how the state will be able to start to pay down the debt that it has and plans to accumulate. | Noted | The government’s present strategy is to manage debt levels relative to the state’s economy. In this regard the government has committed to reduce net debt to gross state product from 25.2 to 25.1 per cent by 2027–28. Refer to Section 3 of the report. | ||

| Relevant material entities | 4 | Develop and implement a robust quality assurance process over financial information provided to Department of Treasury and Finance for Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria purposes. | – | Quality issues with financial information continue to exist. An extended recommendation is provided in this year's recommendations above. | |

| 5 | Prioritise the resolution of information technology control deficiencies that pose a risk to achieving complete and accurate financial reporting, business objectives or compliance with legislation. | – | Information technology deficiencies continue to exist. Refer to Section 4 of the report. | ||

| Department of Premier and Cabinet | 6 | Work with the government, departments and state-controlled entities to reconsider the tabling schedule of annual reports, to reduce the information burden on Parliamentarians and the Victorian community, of tabling high volumes at the same time. | Not accepted | Tabling of annual reports remains delayed. Refer to Section 2 of the report. | |

| Department of Jobs, Skills, Industry and Regions | 7 | Appoint an independent evaluator to assess and report on the effectiveness of the Business Costs Assistance Program and Licensed Hospitality Venue Fund grants programs and whether value for money was achieved. The evaluation should identify lessons learnt and make recommendations for future programs. | Accepted | In progress. Refer to Section 4 for further details. | |

1. Why we do this report and what we look at

In this report, we share outcomes of our audit on the state's financial report and share our independent perspective on the state's financial outcomes and risks to fiscal sustainability.

We also share the audit outcomes of state-controlled material entities that make up significant components of the state's finances.

Our audit opinions provide confidence that the financial reports of the state and material entities are reliable to use and inform decision-making.

The AFR

DTF prepares the AFR. This is the state's consolidated financial report and is also known as the Financial Report (Incorporating Quarterly Financial Report No. 4).

The AFR shows the consolidated financial results for the State of Victoria for a given reporting period. Figure 1 outlines the 3 sectors within the state, which include over 271 state controlled entities that contribute to the consolidated financial results.

We issue an audit opinion on the AFR. Our opinion provides assurance that the published financial outcomes of the state are reliable. This means Parliament and the Victorian community can confidently use the information in the AFR to better understand the state's financial outcomes and, when relevant, make informed decisions.

Figure 1: Sectors in the State of Victoria

Source: VAGO.

Entities excluded from the AFR

The AFR only includes state-controlled entities. Other public sector entities that we audit are excluded from the AFR because the state does not control them for financial reporting purposes.

| The AFR excludes ... | Because ... |

|---|---|

| local government | it is a separate tier of government. Councils are elected by and accountable to their communities. |

| universities | they are mainly funded by the Australian Government. The state appoints a minority of university council members. |

| denominational hospitals | they are private providers of public health services and have their own governance arrangements. |

| state superannuation funds | their net assets are members' property. However, any net asset shortfalls related to certain defined benefit scheme entitlements are a state obligation and are reported as a liability in the AFR. |

| registered community health centres and aged-care providers | they have various funding streams, including from the Australian Government and owned-source revenue, with their own governance arrangements. |

These entities prepare separate financial reports and have them audited.

Material entities in the AFR

Each year we audit and provide separate audit opinions on the financial reports of the state controlled entities that are consolidated into the AFR.

In 2023–24, there were 30 material entities that accounted for most of the state's assets, liabilities, revenue and expenses. We therefore consider these entities to be significant components in the AFR.

We primarily focus on the financial transactions and balances of these material entities when forming our opinion on the AFR.

Reporting our insights on the state's finances

This report is the only report to Parliament that we must make under section 57(1) of the Audit Act 1994. The Act provides that we may comment on and make recommendations about the:

- effective and efficient management of public resources

- proper accounts and records.

We use this report to provide our independent perspective on the state's finances.

We also prepare a dashboard as a companion product to this report. It brings together current and historical financial information for the Victorian GGS reported in past state Budgets and AFRs. You can find this dashboard on our website.

Further information

See Appendix B for more information about our audit approach, independence and our costs.

2. Audit outcomes

Snapshot

Conclusion

We provided a clear audit opinion for the 2023–24 AFR.

Our clear opinion provides reasonable assurance that the financial performance and position of the State of Victoria, and within that the GGS, as reported in the 2023–24 AFR is reliable.

The separate financial reports of 28 of the 30 material entities are also reliable. We issued modified audit opinions on the DJCS's and VicTrack's financial reports. These matters were not material to the AFR.

The state's financial report is reliable

Audit opinion on the AFR

We provided a clear audit opinion on the 2023–24 AFR. Our clear opinion provides reasonable assurance that the financial performance and position of the State of Victoria, and within it the GGS, as reported in the AFR is free from material error.

Key audit matters

Auditors may include a description of key audit matters in the auditor's report, as described under the Australian Auditing Standards. We include such matters in the AFR and material entity audit reports where appropriate.

Key audit matters are those we identify as most significant to an audit and their inclusion in the audit report provides transparency and insight into the audit process.

We reported the following key audit matters for the AFR:

- recognition and measurement of transport assets

- recognition and measurement of service concession assets, liabilities and commitments

- valuation of defined benefit superannuation liability

- valuation of the provision for insurance claims.

A copy of our audit report is in Appendix C.

Most material entities' financial reports are reliable

Material entity audit outcomes

We issued clear opinions on 28 of the 30 material entities' financial reports at the time we issued our opinion on the AFR.

We issued modified opinions on 2 material entities – VicTrack and DJCS. We signed our audit opinion on DJCS after the AFR.

These modifications did not impact our opinion on the AFR because:

- for DJCS, the matter was not material to the state's financial report

- for VicTrack, DTF made a central adjustment on consolidation of the state's financial report to correct the issue.

Appendix D lists the material entities and summarises their financial results and our audit opinions.

Our qualified opinion for DJCS

DJCS is responsible for the road safety camera program, which includes the distracted driver and seatbelt offence detection system. The system detects drivers who are using portable devices while driving or who are not wearing their seatbelt correctly.

DJCS began issuing infringement notices relating to the distracted driver and seatbelt offence detection system on 1 July 2023. Income relating to those offences is recognised as fines income in its financial report.

DJCS outsources the operation of camera technology, information systems and processes used to detect, record and verify data for those offences. For the 2023–24 reporting period, DJCS did not ensure the outsourced provider maintained appropriate controls, accounts and records over these systems and processes.

As a result, we were unable to express an opinion on whether the fines income reported in DJCS's financial report is complete. Accordingly, we issued a qualified opinion.

See Section 4 for more information about how we came to this conclusion.

Our adverse opinion for VicTrack

We have continued to issue an adverse opinion on VicTrack's financial report. This means that its financial report does not accurately reflect its financial performance and position.

VicTrack has continued to account for assets it leases to DTP as operating leases. VicTrack asserts that it substantially holds all the risks and rewards incidental to ownership of the operational transport assets.

We disagree. VicTrack's incorrect accounting is material and pervasive to its financial report.

Our view is that DTP is responsible for the operation of the transport network as a whole and that in this regard DTP:

- directs the use of transport assets by setting the timetables and operating conditions for all modes of transport with no significant input from VicTrack

- substantially holds the risks and rewards of ownership of the operational transport assets.

This is why we formed the view that it is a finance lease. VicTrack continues to incorrectly recognise these leased assets and associated transactions that should be accounted for by DTP.

In the AFR, DTF made a central adjustment on consolidation to correct this inconsistent accounting treatment. This means the fair value of the underlying assets and associated transactions were correctly reinstated at the State-of-Victoria level.

Appendix E further explains the accounting for the lease arrangements of operational transport assets.

Adverse opinion

We make an adverse opinion when an entity's financial reports are misrepresented, misstated or do not accurately reflect the entity's financial health.

Financial report certifications are back to pre-COVID-19 timelines

Legislated timelines

DTF and the state-controlled entities must complete financial reporting tasks by the dates set in the Financial Management Act 1994. Entities are required to provide financial reports to us within 8 weeks of the balance date (30 June), which is 25 August.

The Audit Act 1994 requires us to provide the entity with an audit opinion within 4 weeks of receiving its financial report. That means we should provide audit opinions by 22 September.

To meet their legislative timelines, DTF and VAGO rely on entities providing complete and accurate financial information on time. Delays impact the timeliness of our audit opinions as well as the preparation and tabling of the material entities' financial reports and the AFR in Parliament.

Timely financial reports for material entities

There was a significant improvement in the timing of financial reports this year.

As shown in Figure 2, the median time for material entities to certify financial reports has remained stable at around 9 weeks after 30 June. The pandemic caused significant delays, with the last material entity certifying its financial report 24 weeks after the balance date in 2021–22. This has largely returned to pre-pandemic timelines over the last 2 years.

Figure 2: Timeliness of financial report certifications from 2019 to 2024

Source: VAGO.

This year, one material entity certified its financial report and a further 25 provided draft financial reports by the due date of 25 August. We were then able to provide:

- 20 of the 30 material entities with an audit opinion by the due date of 22 September

- a further 9 material entities with an audit opinion before we gave the Treasurer our audit opinion on the AFR.

Annual report tabling remains delayed

Annual reports are important accountability documents

Annual reports of public sector entities promote transparency and accountability. These reports provide an overview of an entity's activities, financial performance and use of public resources, including the audited financial report. They also ensure accountability by detailing how funds have been spent and outcomes achieved.

As required by the Financial Management Act 1994, state-controlled entities have until 31 October to table their annual reports. They must also table their annual reports when Parliament is sitting. If they do not meet this date, responsible ministers must:

- report this to Parliament, along with the reasons for the delay

- ensure the annual reports are tabled as soon as possible after they are received.

We have an obligation under the Australian Auditing Standards to consider whether financial information in annual reports is consistent with the audited financial report. If we identify an inconsistency, it may indicate a material misstatement in either the financial report or financial information of the annual report. This consistency check is done before we release our audit opinion if the annual report is available by the agency.

Delayed tabling of annual reports

By 31 October 2024, we had issued audit reports on 235 state-controlled entity financial reports. This includes audit reports of both parent and subsidiary entity financial reports. Of these:

- 124 state-controlled entity annual reports were tabled by 31 October 2024.

- 111 state-controlled entity annual reports were not tabled by 31 October 2024.

On 30 October 2024, the Assistant Treasurer, on behalf of the responsible ministers, informed Parliament that the annual reports of 131 public bodies would be delayed because the ministers had not received them in time. There was no explanation for these delays, as required by the Financial Management Act 1994.

Quality concerns with financial information submitted by material entities pose a risk to the state's financial report

Quality of information requires improvement

DTF relies on state-controlled entities providing it with timely, complete and accurate financial information so it can prepare and publish the AFR.

| DTF requested ... | To provide their trial balance by ... | And supplementary information for disclosures by … |

|---|---|---|

| GGS entities | 24 July 2024 | 7 August 2024. |

| public financial corporation (PFC) and public non-financial corporation (PNFC) entities | 1 August 2024 |

Each entity's chief financial officer (CFO) must certify that the information provided to DTF is complete and accurate.

In our Auditor-General's Report on the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria: 2022–23, we recommended that material entities develop and implement robust quality assurance processes on financial information provided to DTF.

This year, we continued to identify challenges with the quality of information provided. More specifically, we noted:

- delays in the provision of information

- significant errors in the information, including incorrect classification of liabilities, cashflows from investing activities and overstatements in service concession arrangement commitments

- changes to key finance staff and responsibilities, leading to a loss of knowledge on the submission processes and obligations required by DTF.

Delays and poor-quality financial information submitted puts pressure on DTF's quality assurance processes, increasing the risk of undetected material errors. This may lead to inaccurate financial reporting, which can negatively impact decision-making by the government, Parliament and the Victorian community.

Recommendations

Relevant material entities

Extending from our recommendation last year, we recommend relevant material entity CFOs:

- develop and implement robust quality assurance processes over the financial information provided to DTF

- ensure:

- internal processes are documented well enough to enable a new starter to understand what submission processes and obligations are required by DTF, how these processes are to be done and by when

- adequate training and knowledge transfer occurs for all key finance staff to support the process.

Department of Treasury and Finance

In our 2022–23 report, we recommended DTF investigates key drivers for the quality issues with financial information submitted and consider whether any further training or guidance may be required to support material entities and reduce the risk of inaccurate financial reporting.

3. Financial outcomes for the GGS and risks to fiscal sustainability

Snapshot

Conclusion

The GGS achieved an operating cash surplus this year, but it incurred another accrual operating loss, bringing accumulated losses over the last 5 years to $48 billion. It also reported a fiscal cash deficit as it has for the last 8 years.

Ongoing operating losses and fiscal cash deficits are indicators of structural issues with underlying revenue and expenditure policy settings that create risks to financial sustainability.

The government has announced further planned savings of $4.9 billion over the next 4 years to manage costs. Achieving these savings and maintaining current service levels will be a challenge given the current financial pressures and several emerging financial risks.

The GGS's gross debt rose again this year at a pace faster than revenue and economic growth. The government's present strategy is to manage debt levels relative to the state's economy. In this regard, the government has committed to start reducing net debt to GSP in 2027–28.

Sound financial management underpins fiscal sustainability. A clear and well defined longer term financial plan is an important part of this. Developing this longer-term plan will provide a clear framework against which government decision-making can be anchored.

Long-term focus to fiscal management is required, prioritising management of existing and emerging financial risks

Fiscal sustainability

What is fiscal sustainability?

To remain fiscally sustainable, the state must meet current and future expenditure requirements from revenue earned, absorb foreseeable changes and materialising risks and manage the impact from these factors to changing revenue and expenditure requirements.

Fiscal sustainability

Fiscal sustainability is the ability of the government to maintain public finances at a credible and serviceable position now and into the future. Ensuring long-term fiscal sustainability requires governments to engage in ongoing monitoring and strategic forecasting of future revenue and expenditure, environmental factors and socioeconomic trends to remain financially resilient.

Fiscal strategy

Fiscal strategy outlines the government's fiscal strategies and objectives

The state Budget sets out the Victorian Government’s long-term financial management objectives for the GGS along with short-term objectives and key financial measures and targets for achieving the government's fiscal strategy.

The state’s long-term financial management objectives, as outlined in the 2024–25 state Budget, are:

- sound financial management

- improved services

- building infrastructure

- efficient use of public resources

- a resilient economy.

The government acknowledges that sound fiscal management requires a realignment of revenue and expenditure, coupled with a strategy to fund the government’s infrastructure program.

Accordingly, the government developed a 4-step fiscal strategy aligned with its key financial measures and sustainability objectives in the 2020–21 state Budget. This strategy involved 4 steps:

- step 1: creating jobs, reducing unemployment and restoring economic growth

- step 2: returning to an operating cash surplus

- step 3: returning to operating surpluses

- step 4: stabilising debt levels.

In the 2024–25 state Budget, the government added a fifth step to this fiscal strategy – reducing net debt as a proportion of GSP by the end of its forward estimate period.

Fiscal strategy

A fiscal strategy is a clear statement of the government’s fiscal objectives and targets over a defined period. It sets out the government's short term and long-term fiscal strategies and objectives for managing its finances and existing and emerging risks. It also demonstrates how planned government policies will contribute to fiscal sustainability and macro-economic stability.

Short-term financial sustainability objectives

State's finances were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, rising debt and structural issues

The government has also developed short-term financial sustainability objectives given the fiscal position has been impacted by past underlying structural issues, the COVID-19 pandemic and borrowings to support its large infrastructure program.

Figure 3 shows these objectives as set out in the last 4 Budgets.

Figure 3: GGS short-term financial sustainability objectives

| Budget year | Operating cash surplus | Net operating balance | Net debt to GSP |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2024–25 | Operating cash surplus will be achieved by 2022–23 and maintained over the Budget and forward estimates period. | Net operating balance will return to a surplus by 2025–26. | Net debt to GSP will stabilise and begin to decline by the end of the forward estimates period. |

| 2023–24 | Operating cash surplus will be achieved by 2022–23 and maintained over the Budget and forward estimates period. | Net operating balance will return to a surplus by 2025–26. | – |

| 2022–23 | Operating cash surplus will be achieved by 2022–23. | Net operating balance will return to a surplus by the end of the forward estimates period. | – |

| 2021–22 | Operating cash surplus will be achieved before the end of the forward estimates period. | – | – |

Source: VAGO, based on the AFR and state Budget.

Financial measures and targets

Financial measures and targets are less defined and may undermine discipline in use of public resources

To support these objectives, the state has set key financial measures and targets. Figure 4 outlines the government's key financial measures and targets for the GGS set out in respective state Budgets along with the actual outcomes reported for the last 2 years.

The measures and targets are qualitative, except for one: fully funding the unfunded superannuation liability by 2035.

Figure 4: GGS key financial measures, targets and results

| Financial measure | Target | 2022–23 actual | 2023–24 Budget | 2023–24 actual |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operating cash surplus/deficit(a) | A net operating cash surplus consistent with maintaining GGS net debt at a sustainable level | $4.3 billion net operating cash surplus | $0.8 billion net operating cash surplus | $2.6 billion net operating cash surplus |

| Net debt to GSP(b) | GGS net debt as a percentage of GSP to stabilise in the medium term | 20.3% | 22.6% | 21.9% |

| Interest expense to revenue | GGS interest expense as a percentage of revenue to stabilise in the medium term | 4.7% | 6.2% | 6.1% |

| Superannuation liabilities (contribution to the State Superannuation Fund) | Fully fund the unfunded superannuation liability by 2035 | $0.6 billion | $0.3 billion | $0.1 billion |

Note: (a)These are the net cashflows from operating activities as disclosed in the consolidated cashflow statement.

(b)Net debt is gross debt less liquid financial assets. It is the sum of deposits held, advances received, government securities, loans and other borrowings less the sum of cash and deposits, advances paid, investments, loans and placements.

Source: VAGO, based on data from the state Budget, the AFR and a publicly announced policy costing.

Financial measures and targets have been progressively revised over the last 12 years from quantifiable targets to ones that are less defined, which can be seen in Appendix F. With the exception of fully funding the superannuation liability, these measures lack specific targets and clear timelines for achieving them.

The measures and targets were amended in 2020–21 to reflect the uncertain economic and fiscal environment and the government’s focus on economic recovery after the pandemic. For example, the 'operating surplus' target was removed and the 'operating cash surplus' and 'interest expense to revenue' targets were introduced. These new targets had no specific measures other than to achieve the outcome.

COVID debt repayment plan

In the 2023–24 state Budget, the government also introduced a temporary plan to reduce the cost of servicing the debt from its response to the COVID-19 pandemic of $31.5 billion. This plan is for a 10-year period to 2033 and has 3 parts:

- introduction of a temporary COVID debt levy on land and payroll tax

- rebalancing the public service through further savings and efficiency initiatives across the government, including reductions in corporate and back-office functions, labour hire and consultancy expenses. An estimated saving of $2.1 billion was included in the 2023–24 Budget for a 4-year period ending 30 June 2027

- establishing the Victorian Future Fund (VFF), where the $7.9 billion proceeds received in

2022–23 from outsourcing licensing, registration and custom plate services through the VicRoads modernisation joint venture arrangement will be invested.

The government took on COVID-19-related debt when interest rates were historically low. Given the current low cost of servicing this debt and its long repayment timeline, the government does not plan to pay it off immediately. Instead, funds from the COVID debt levies and savings and efficiency initiatives mean the government expects to borrow less than planned for the state's infrastructure program.

The VFF has been established as an offset account, where investments and their returns will be used to offset pandemic borrowings, lowering the cost of servicing debt.

The government has not publicly reported how it progressed with this plan during 2023–24, including realisation of benefits from saving and efficiency initiatives.

Our observations

Long-term fiscal focus needed

While strategies and objectives are in place, the state has not articulated a clear plan for long-term fiscal management. Current strategies are short term, reactive and do not address both the existing financial challenges and emerging financial risks that we comment on further in this section. A more comprehensive approach is needed to ensure long-term fiscal sustainability and proactive management of the state's finances.

Developing a well-defined, long-term plan will provide a clear framework for which government decision-making can be anchored to ensure the allocation of public resources are prioritised not only based on policy intent but align with the financial and economic strategies and constraints to maintain financial health. It will also enable ongoing monitoring and assessment, helping the government uncover risks to financial health and adapt accordingly.

The government can also use the plan to transparently report its progress, remaining accountable to managing fiscal sustainability of the state.

3.1 Financial outcomes for the GGS

Our analysis focuses on the GGS because movements between years in the GGS's results explain most of the movements in the state's consolidated results, with some notable exceptions.

The GGS reported another net operating loss of $4.2 billion this year, bringing accumulated losses over the last 5 years to $48 billion

What is the operating result and why is it important?

The net operating result is a key measure of the GGS's financial performance and fiscal sustainability. A positive operating result reflects the state’s capacity to earn revenue and effectively manage expenses, resulting in a surplus that can be used for future needs.

The GGS reported another net operating loss this year of $4.2 billion, as shown in Figure 5. This is an improvement of $4.6 billion compared with last year, however, more than the $4.0 billion estimated in the 2023–24 state Budget.

This result brings the state's total accumulated losses over the last 5 years to $48 billion. The government attributes approximately:

- $31.5 billion of these cumulative operating losses to its COVID-19 response from 2019–20 to 2022–23

- $16.5 billion of these cumulative operating losses to providing ongoing public services.

These operating losses deplete cash reserves, increase debt, and diminish the state's financial resilience and ability to respond to future shocks.

Figure 5: GGS net operating result

Source: VAGO, based on the AFR and state Budget.

The GGS is forecast to incur a further net operating loss of $2.2 billion in 2024–25 before expecting to return to a net operating surplus from 2025–26. This will bring the cumulative operating losses over 6 years to 2024–25 to $50.1 billion.

Of the $50.1 billion, $18.6 billion of losses are attributable to providing ongoing public services. The operating surpluses forecast from 2025–26 to 2027–28 in the 2024–25 state Budget only allow for recovery of $5.1 billion of the accumulated losses by 2027–28. The government will need to make significant surpluses beyond current budgetary forecasts to restore the financial resilience eroded by these losses.

The government has announced various saving initiatives and efficiency dividends to manage these weaker financial outcomes in the state Budget. Figure 6 shows the value of cumulative savings announced from 2019–20 to 2027–28 of $9.0 billion, with $4.9 billion to be realised from 2024–25 to 2027–28.

Figure 6: Cumulative saving initiatives announced in the state Budget

Source: VAGO, based on the state Budget.

Achieving these savings and maintaining current service levels will be difficult given the financial pressures faced, including the current financial outcomes, growing employee costs, interest expenses from servicing debt, inflation and demand for services due to the growing population.

These risks are discussed further in our emerging risks section. The government must manage these emerging risks closely if it is to achieve the forecast operating surplus in 2025–26.

How the operating deficit was achieved

Figure 7 shows the key contributors of this year's improvement in operating results compared with last year.

Figure 7: Changes in the GGS net operating result from 2023 to 2024

Note: Numbers have been rounded. ITE stands for income tax equivalents.

Source: VAGO, based on the AFR and state Budget.

This improved result is driven by operating revenue growing more than operating expenses.

Operating revenue rose by $8.4 billion, or 9.9 per cent, increasing from $84.7 billion in 2023 to $93.1 billion in 2024, mainly driven by higher:

- taxation income of $4.5 billion due to the COVID debt levy applied on payroll and land holdings and stronger economic conditions in property and labour markets

- grants received from the Australian Government of $1.7 billion mainly due to growth in the national GST pool, supported by elevated inflation and a resilient labour market

- dividends and income tax equivalents (ITE) of $1.4 billion, largely due a $1.1 billion dividend payment from the TAC due to its improved profitability in recent years from lower claims.

Operating expenses increased by $3.7 billion, or 4.0 per cent, from $93.6 billion in 2023 to $97.3 billion in 2024, mainly driven by:

- employee expenses of $2.4 billion from higher full-time employee (FTE) and wage growth

- interest expense of $1.7 billion due to new borrowings or refinanced borrowings at higher interest rates

- other operating expenses of $2.0 billion, including a $380 million payment for the withdrawal from the 2026 Commonwealth Games and $248 million for higher concession payments mainly relating to energy bill relief payments – additionally, a general increase in expenses due to inflationary pressures and government activity

- an offset of $2.4 billion reduction of grant expenses for on-passing local government grants and private sector and not-for-profit grants.

Funding from the Australian Government, increases in taxation income and income sourced from public corporations have continued to make a substantial contribution to the GGS's operating result.

Income sourced from public corporations comprise dividends, statutory fees and charges, financial accommodation levy, environmental contribution levy, grants and ITE receipts. The receipts of $2.4 billion have contributed to a reduction in the GGS's operating deficit and achieving positive operating cashflows in 2023–24.

Figure 8 shows income and revenue sourced from public corporations over the last 10 years together with the forecast from 2024–25 to 2027–28.

Figure 8: Income and revenue sourced from PFCs and PNFCs

Source: VAGO, based on the AFR and state Budget.

Income and revenue sourced from public corporations have fluctuated over the years. However, they saw a substantial increase this year, rising to $2.4 billion from $1.1 billion in 2022–23. This increase was primarily driven by one-off dividends of $1.1 billion from the TAC.

Public corporations

Public corporations are state-owned entities or statutory authorities established under legislation. They include:

- PNFCs that provide a wide range of goods and services while meeting commercial principles through cost recovery via user fees and charges

- PFCs that deal with financial aspects of the state. They have the power to borrow, accept deposits and acquire financial assets.

The GGS achieved a $2.6 billion operating cash surplus through higher tax income, dividends and more Australian Government funding

What is the operating cash result and why is it important?

The operating cash surplus is the extra money left over for the government in a financial year after paying for its operations and running expenses, such as employee salaries, supplier expenses, interest costs and utilities.

The state achieved an operating cash surplus of $2.6 billion this year. This is $1.8 billion higher than the forecast in the 2023–24 Budget of $0.8 billion. However, it is $1.6 billion less than last year's operating cash surplus of $4.2 billion.

Last year's operating cash surplus included $7.9 billion of proceeds received from VicRoads modernisation joint venture arrangement.

Achieving the operating cash surplus this year was possible because of:

- the increase in taxation income of $4.5 billion explained previously

- the one-off dividend payment of $1.1 billion from the TAC

- local government financial assistance grants of $0.7 billion received from the Australian Government before the year end and paid out to councils post year end.

Prolonged fiscal cash deficit is a challenge to ongoing fiscal sustainability and is set to continue

Fiscal net cash deficit outcome for a further year

A key indicator of financial sustainability is the fiscal cash surplus/deficit outcome. A fiscal cash surplus means the state's cash inflows from operations exceed its recurrent and capital outlays.

A fiscal cash surplus is a sign of good financial health because it means there is available cash for the state to invest in public services, pay down debt or build financial resilience for future uncertainties. A fiscal cash deficit means the state has to borrow to cover its net investments in non financial assets used to provide public services.

Figure 9 shows the fiscal cash surplus/deficit of the GGS since 2015–16, in addition to the projected outcome for the Budget and forecast years from 2024–25 to 2027–28.

Figure 9: Fiscal cash surplus/deficit

Source: VAGO, based on the AFR and state Budget.

The GGS made a fiscal cash deficit of $14.4 billion in 2023–24. It has not made a fiscal cash surplus for last 8 years, with this trend expected to continue over the next 4 years. This prolonged period of fiscal cash deficits demonstrates why the state has relied so heavily on borrowings to fund capital needs, which is a challenge to its financial sustainability.

Fiscal cash surplus/deficit

The cash surplus/deficit is calculated by:

- net cashflows received from operating activities, which are the sum of cash received from sources, such as taxes and government grants, offset by cash spent on operating expenses, such as employee costs

- plus net cashflows from investment in non-financial assets, being the sum of cash earned from investment activities, such as the sale of land and buildings, offset by cash spent on capital projects

- less dividends received from public corporations.

GGS gross debt rose by $24.9 billion to $168.8 billion, faster than revenue and economic growth

Victoria's debt is at a record high and projected to grow further

Victorian state debt is historically high and expected to grow as the government continues to borrow to fund its significant planned infrastructure program.

In Victoria, there is a total of $208 billion in new and existing capital projects underway. The state Budget committed to investing $132 billion in capital projects from the 2024–25 financial year and beyond. The majority of this investment is expected to be debt funded.

Figure 10 shows the growth of Victoria's gross debt since 2013–14 and forecast growth over the forward estimates to 2027–28.

Figure 10: Growth of Victoria's gross debt

Source: VAGO, based on the AFR and state Budget.

The GGS's gross debt rose from $33.4 billion at 30 June 2014 to $168.8 billion at 30 June 2024. In particular, rapid growth of 154 per cent was experienced since 2019–20, when debt was $66.5 billion.

GGS gross debt is projected to grow to $228.2 billion by 30 June 2028. The state's gross debt follows a similar growth pattern. It was $195.7 billion as at 30 June 2024 and is expected to grow to $268.4 billion by 30 June 2028.

The growth in debt was in part used to fund the state's operating deficit in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and in part to fund planned infrastructure programs and unplanned cost overruns of existing infrastructure projects, with this breakdown in Figure 11.

Figure 11: GGS gross debt profile by its purpose and use

Source: VAGO, based on the AFR and state Budget.

The state took on $31.5 billion debt in responding to the pandemic, more than 18.7 per cent of the government's current outstanding debt.

Using debt to fund investment in intergenerational infrastructure is common. It enables the government to allocate resources and invest in long-term projects that the taxpayers might not otherwise afford today. However, a higher and unsustainable level of public debt can pose a significant risk to future prosperity and economic stability. If not managed in a fiscally sustainable and responsible manner, debt imposes a direct cost on taxpayers both now and in the future.

Victoria's debt has been growing faster than other states

Figure 12 shows GGS total gross debt of all Australian states as a percentage of nominal GSP for each state. This is a common measure used across jurisdictions to understand their relative indebtedness. Victoria’s debt to GSP ratio was comparable to other states prior to the pandemic. Since then, it has diverged significantly. This trend is forecast to continue to 2027–28.

Figure 12: Gross debt of Australian GGS by state

Source: VAGO, based on each state Budget.

3.2 GGS emerging risks

Achieving fiscal sustainability requires close attention and management of several emerging risks

Risks to fiscal sustainability currently remain elevated

Achieving the current fiscal strategy is critical for the financial sustainability of the state.

The government aims to maintain the operating cash surplus achieved last year over the forward estimates to achieve a net operating surplus by 2025–26 and to stabilise and reduce debt as a proportion of GSP by 2027–28.

There are several emerging risks that require close attention and management if the government is to achieve its fiscal strategy and ensure fiscal sustainability over the medium and long term.

They include:

- growing indebtedness of the state

- rising interest costs of new and refinanced debt

- rising employee costs taking up a large portion of the GGS's revenue and income

- managing operating expenses growth amid rising service demand and high inflation

- limitations to new revenue and income streams

- unplanned and significant cost escalations of major infrastructure projects.

These risks are discussed below.

Growing indebtedness of the state

Managing debt at a sustainable level is an important requirement for fiscal sustainability

Managing debt at a sustainable level ensures that the government can access debt markets while keeping the cost of debt low, is able to respond to future crises and can ensure intergenerational equity.

Several measures of fiscal sustainability indicate that Victoria’s debt burden has increased and the state’s ability to service these debts has decreased.

The state Budget and fiscal strategy contain several measures aimed at achieving fiscal sustainability. The government assesses the sustainability of the debt by applying the following financial measures:

- net debt to GSP

- interest expense to revenue.

We also consider the following to be appropriate measures:

- gross debt to GSP

- gross debt to revenue (indebtedness) – gross debt as a proportion of operating revenue

- interest expense relative to the portfolio of debt – considering new and refinanced (rolled over) debt and the maturity profile.

The impact of rising debt and interest expense on these debt sustainability measures are discussed further below.

Intergenerational equity

Intergenerational equity means fairly sharing economic costs and benefits of the government's fiscal policy decisions, such as taxation, public spending and borrowing across different generations.

Gross debt as a proportion of GSP continues to increase

Gross debt to GSP is a key financial measure of the GGS and an indicator of the size of the state’s debt in relation to the size of the economy.

The higher this ratio, the more difficult it is for the state to pay back its debt.

An increasing ratio means that state debt is growing faster than the economy. This scenario puts additional pressure on debt service costs and consequently the net operating result, which makes it harder to repay debt.

Figure 13 shows that gross debt as a percentage of GSP has rapidly grown. The 2024–25 state Budget forecasts that debt will stabilise as a proportion of GSP by 2027–28.

Figure 13: GGS gross debt as a percentage of GSP

Source: VAGO, based on the AFR and state Budget.

Average growth of GGS gross debt from 2015–16 to 2018–19 was 7.6 per cent per year. GGS gross debt grew by an average rate of 33.3 per cent per year from 2019–20 to 2022–23 due to significant investment in infrastructure programs and pandemic-related expenses.

Gross debt is forecast to increase from 27.7 per cent in 2023–24 to 30.5 per cent of GSP in

2027–28, growing at an average rate of 7.9 per cent per year during that period, well above the growth in GSP and GGS revenue.

Figure 14 shows that while the growth rate of per capita debt growth is projected to slow, it will still outpace revenue growth through to 2027–28 thereby increasing the debt burden on Victorians.

Figure 14: Annual growth in per capita GSP and per capita gross debt of the GGS

Source: VAGO, based on the AFR and state Budget.

Steps 4 and 5 of the government’s fiscal strategy aim to stabilise and reduce net debt as a proportion of GSP by 2027–28. The government has committed to reduce net debt to GSP from 25.2 to 25.1 per cent by 2027–28. However, the government has not established a long-term specific target for net debt to GSP ratio or ceiling on the quantum of debt it plans to take on.

Achieving consistent and higher nominal economic growth is key to achieving steps 4 and 5 of the fiscal strategy. However, it may not address the sustainability risks associated with growing debt.

Gross debt as a proportion of revenue is projected to rise over 200 per cent in 2024–25

While governments commonly use net debt as a proportion of GSP as a measure, gross debt to public sector operating revenue is also a useful measure of fiscal sustainability. This can be particularly informative:

- if the growth in state revenue uncouples from economic growth

- in a higher interest rate environment, especially where the interest rate is higher than annual GSP growth and the government's revenue growth.

Figure 15 shows that gross debt as a proportion of operating revenue is continuing to increase.

Figure 15: GGS gross debt as a proportion of operating revenue

Source: VAGO, based on the AFR and state Budget.

In this scenario, debt servicing and allocating money to essential services can be problematic because interest repayments take a greater bite from operating revenue.

Rising interest costs for new and refinanced debt

Interest expense is rising faster than revenue – interest bite

Stabilising GGS interest expense as a percentage of revenue in the medium term is one of the government’s financial measures and targets. As the state’s debt increases, and interest rates remain elevated, so does the interest expense incurred to service the debt.

Comparing interest expense to operating revenue provides information on the share of revenue devoted to servicing debt costs (the interest bite).

Figure 16 shows that the interest bite will increase significantly over the next 4 financial years. In 2023–24, 6.1 per cent of the GGS operating revenue, or $5.6 billion, was needed to service debt costs compared to 3.4 per cent, or $2.3 billion, in 2019–20. This is estimated to increase to 8.8 per cent, or $9.4 billion, by 2027–28.

Figure 16: Interest expense as a percentage of revenue

Source: VAGO, based on the AFR and state Budget.

Although the government aims to stabilise interest expense to revenue in the medium term, it has not set a specific and measurable target or the year it expects to achieve this measure.

When the government spends more money on interest payments, there will be less money available for public services.

The move from low to high interest rates significantly increase the interest bite

The transition from a low interest rate to higher interest rate environment post COVID-19 has and will continue to increase the cost of borrowing, leading to the proportion of interest costs from new and refinanced debt becoming larger.

The Treasury Corporation of Victoria (TCV) facilitates the raising of debt for the state by issuing bonds to both the domestic and international capital markets. It then lends this (on-lends) to DTF or other government entities. Approximately 90 per cent of TCV's lending is to the GGS via DTF. DTF uses the amounts borrowed to fund the government's initiatives.

TCV has projected to borrow a further $71.2 billion over the next 4 years to 30 June 2028 as seen in Figure 17 for on-lending to the GGS and other government entities.

The 2024–25 state Budget estimates GGS gross debt to be $228.2 billion by 30 June 2028.

Figure 17: Total financing required by the state by origin over the next 4 years ($ billions)

Note: New money refers to the funds required to finance new capital projects and operational needs.

Refinancing refers to the replacement of an existing debt obligation with another debt obligation under different terms. It is usually performed to extend the original debt over a longer period of time, to change fees or interest rates or to move from a fixed to variable interest rate.

Source: VAGO, based on TCV.

In addition, TCV projects to refinance $52.1 billion of existing debt. This debt was originally entered into in a lower interest rate environment during the pandemic. In the current high interest rate environment it is likely these refinanced borrowings will come at higher interest rates, as will any new borrowings entered into. This presents a significant financial sustainability challenge because it reduces the proportion of revenue and income earned for use on public service delivery.

At 30 September 2024, the 10-year TCV government bond rate was 4.8 per cent, which is significantly higher than the average interest rate of around 3.6 per cent on TCV existing debt.

As currently issued TCV debt matures between 2025 and 2028, interest paid on it will decrease approximately from $4.8 billion to $3.8 billion. However, as this debt is refinanced and new funding requirements are financed, total new financing interest expenses are projected to rise approximately from $1.4 billion to over $5.2 billion over the same period as seen in Figure 18. This therefore means that the overall increase in interest expense for the period is projected to be approximately an increase of $2.8 billion.

Figure 18: Expected interest cost on TCV debt including new and refinanced debt ($ billion)

Source: VAGO, based on TCV.

Government bond

A government bond is a loan for a specified period with regular interest payments with repayment of face value in full at the maturity.

Rising employee costs consuming more revenue and income

Managing employee expense growth

Employees are the state’s largest single operating expense.

In 2023–24, the GGS paid its employees $36.0 billion, which represents 37.0 per cent of its total expenses, compared to 35.9 per cent in 2022–23.

GGS employee expense has risen by 32.4 per cent from $27.2 billion in 2019–20 to $36.0 billion in 2023–24. Growth in employee expense peaked at 10.4 per cent in 2020–21 due to the government's pandemic response, however, has since gradually declined to 7.2 per cent in 2023–24.

The government forecasts it will grow by another 10.8 per cent over the next 4 years to $39.9 billion in 2027–28. This forecast is a modest annual increase of 2.6 per cent compared with the annual growth of 7.6 per cent over last 8 years.

Managing employee expense growth at forecast levels will be a challenge, particularly in a period of enterprise bargaining where several sector-based enterprise bargaining agreements (for example, for police, teachers, paramedics and nurses) either have been or are due for renegotiation in coming years at higher rates, which will likely increase pressure on employee expenses. This, combined with growing demand for public services driven by population growth, will add further strain on employee expenses.

The government’s wages policy, established to set parameters around public sector enterprise bargaining, is expected to assist in managing some of these challenges.

Figure 19: Growth in GGS employee expenses

Note: Averages are shown as horizontal lines.

Source: VAGO, based on the AFR and state Budget.

Figure 20 shows that the number of Victorian Public Service (VPS) employees and all public sector employees increased over the 10-year period to 30 June 2023. At the time of writing this report, the Victorian Public Sector Commission had not released employee data for the year ended 30 June 2024.

The VPS grew by 64.0 per cent while all public sector employees grew by 39.5 per cent in that period.

Between 2018–19 to 2020–21, VPS FTE employees increased by 8,487, or 18.0 per cent, as the government responded to the COVID-19 pandemic. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, growth in VPS FTE employees has stabilised. There was 3.8 per cent decrease in FTE employees in 2021–22, followed by 2.1 per increase in 2022–23.

Figure 20: Number of FTE employees in the VPS public sector

Source: VAGO, based on the Victorian Public Sector Commission.

The government's Budget estimates of the last few years and in 2023–24 included implementing targeted cost saving initiatives through staff reductions. If the benefits of these initiatives are not realised as planned, the employee cost will be greater than estimated and forecast targets will not be achieved.

The VPS

The VPS comprises of around 40 government departments, agencies and administrative offices.

Overall public sector

The overall public sector comprises of around 1,750 organisations, including 1,500 schools and 250 entities, such as hospitals, emergency services, water authorities, cemetery trusts, creative industry agencies and sport and recreation organisations. These agencies fall within both the GGS and public corporation sectors.

Expense management amid rising service demand and high inflation

Cost management

Other operating expenses is the second largest component of GGS expenses, representing nearly 30 per cent of total expenses, or $29.1 billion, for 2023–24.

As shown in Figure 21, other operating expenses grew at an average rate of 4.5 per cent from 2015–16 to 2018–19. During the pandemic it peaked at 13.7 per cent per annum.

The government forecasts other operating expenses to reduce by an average rate of 0.7 per cent over the next 4 years to $28.2 billion by 2028.

Figure 21: GGS operating cost growth

Note: Averages are shown as horizontal lines.

Source: VAGO, based on the AFR and state Budget.

To achieve its financial objectives the government will need to ensure that the rate of growth in recurrent expenses falls and stays below revenue growth.

The government plans to reduce other operating expenses growth through various saving initiatives announced in past state Budgets. Realisation of these initiatives will be a challenge because of:

- unfavourable macro-economic conditions that accelerate expenses growth, including higher inflation and higher Victorian population forecasts increasing demand for public services

- financial discipline required by management of departments and agencies that face challenges from maintaining service delivery under constraints from previous saving initiatives and reduced funding from reprioritisation of programs and initiatives.

Some of the macro-economic conditions, such as higher inflation and population growth, may contribute to revenue and income growth.

The government will need to ensure relevant agencies, such as DTF, establish processes beyond current practices to monitor progress against these saving initiatives. This should help the government identify unexpected conditions and risks to both financial health and service delivery, allowing for timely change in approach.

Limitations to new revenue and income streams

Sources for raising additional revenue and new cash inflows are limited

In the 2023–24 financial year, the GGS reported revenue and income of $93.1 billion. A major portion of this came from taxation income and grants from the Australian Government, accounting for 39.6 per cent and 44.9 per cent of the total respectively.

Revenue and income grew by 37.1 per cent, rising from $67.9 billion in 2019–20 to $93.1 billion in 2023–24.

Figure 22: GGS revenue composition and growth

Source: VAGO, based on the AFR and state Budget.

Taxation income has grown by 59.2 per cent since 2019–20. The mental health and wellbeing surcharge and COVID debt levy contributed $0.9 billion and $3.1 billion in additional tax revenue in 2022–23 and 2023–24.

Figure 23: New taxes introduced by the government

Source: VAGO, based on the State Revenue Office Victoria

Commercialisation opportunities are diminishing

The commercialisation of government assets and services has been a significant source of cash inflow in recent years.

Over the last 8 years, the government has commercialised or leased several assets and functions to private sector entities. Key transactions include:

- leasing the Port of Melbourne land, channels and infrastructure assets for an upfront payment of $9.7 billion in 2016–17

- commercialisation of Victorian Land Registry Services for $2.9 billion in 2018–19

- VicRoads modernisation joint venture arrangement for $7.9 billion in 2022–23.

While the receipt of $20.5 billion in funds from these arrangements has assisted the government in managing operating and investing cash needs, it has also lost some future cash inflows generated from these assets and services.

Unplanned and significant cost escalations of major infrastructure projects

Cost escalations of major infrastructure projects

The GGS outlaid $17.4 billion on infrastructure and capital assets this year, an increase of $1.1 billion compared to last year's $16.3 billion.

For the last 4 years, we have tracked the performance of major projects expected to cost $100 million or more. We are currently reviewing major projects that were complete and active at 30 June 2024 and listed in Budget Paper 4: State Capital Program as part of our limited assurance review Major Projects Performance Reporting 2024. This limited assurance review report is currently scheduled for tabling in 2025.

Through our reviews, we have consistently observed cost escalations in major projects. For example, the total estimated investment (TEI) of the Metro Tunnel Project was $10.9 billion when it first appeared in Budget Paper 4. However, as of 30 June 2024, the TEI is estimated to reach $12.6 billion, representing an increase of $1.7 billion.

The costs escalations in major projects can be attributed to several reasons both within and beyond the control of the state, including:

- staging of funding increases after projects develop more detailed plans

- redesigning or increasing the scope or capacity of a proposed project

- the impact of decisions about adopting procurement models

- unexpected price increases after a market engagement

- volatility in the construction industry and supply chains

- contract variations signed with private sector parties.

Costs escalations, regardless of their causes, may need additional funding.

In the 2024–25 state Budget the government committed to investing $208 billion in capital projects. This is a net increase of $7.9 billion compared to the same time last year.

In the 2024–25 state Budget, the government announced that the Suburban Rail Loop (SRL) East is expected to cost between $30.0 billion and $34.5 billion. The government has not yet fully disclosed the TEI, estimated expenditure and estimated completion date of the entire SRL.

If cost escalations in current and new major projects persist, it will further significantly strain the state's fiscal sustainability.

3.3 Emerging risks beyond the GGS and their impact

Why the financial sustainability of public corporations is important for the GGS and Victorians

Public corporations' financial sustainability

Public corporations in Victoria play a crucial role in providing services to Victorians and fulfilling the government's economic, social and public policy objectives. They provide services in sectors considered essential or strategic, such as transportation, utilities and public financial services.

Financial sustainability of PFCs is critical for the government's overall fiscal sustainability. It allows these corporations to continue providing essential services without disruption and improve the quality of services by way of investing in innovation and new development.

Non-sustainable financial corporations can add financial strain on the GGS's financial position because taxpayers' money is often used to support the financial health of these corporations. Further, fees and levies charged by these corporations to the public may increase adding financial burden to citizens.

There are several emerging risks in the public corporations space that require close attention by the government to avoid further sustainability challenges. They are discussed below.

Continued trend of rising insurance liabilities

Insurance liabilities to rose to $50.1 billion

Three of the 7 PFCs are insurers – the Victorian WorkCover Authority (WorkSafe), the TAC and the Victorian Managed Insurance Authority. These entities, which are not in the GGS, have a considerable influence on the operating result, balance sheet and cashflow outcomes of the state.

Transactions with these PFCs also have a significant impact on the GGS operating result, balance sheet and operating cash result outcomes in varying ways. The government:

- in recent years, has used taxpayers' money to support the financial sustainability of WorkSafe – as an example, WorkSafe received $1.3 billion from the government across 2020–2023 to support its financial sustainability

- sources income from these corporations through dividends, grants, taxation equivalent payments, levies and capital repatriation that helps with the financial outcomes of the GGS – as an example, the TAC paid a $1.1 billion dividend to DTF this year.

At 30 June 2024, these insurers had $53.1 billion of total liabilities and held $53.3 billion of total assets. The majority of these assets were held to back insurance liabilities. Of those liabilities, $50.1 billion (94.5 per cent) related to outstanding insurance claims. Insurers paid $6.2 billion in claims during 2023–24 (compared with $5.4 billion in 2022–23).

Figure 24 shows that the value of the total outstanding insurance claim liabilities of the state continues to grow.

Figure 24: Total insurance claim liabilities at 30 June

Source: VAGO, based on the AFR.

WorkSafe contributes 58.2 per cent to the state's insurance liability and remains the primary driver of the growth

WorkSafe is Victoria's workplace health and safety regulator. It manages the WorkCover insurance scheme and aims to reduce harm in the workplace and improve outcomes for injured workers.

Figure 25 shows that the value of WorkSafe’s outstanding insurance claims has increased by more than 80 per cent since 2018–19.

Figure 25: WorkSafe's outstanding insurance claim liabilities at 30 June

Source: VAGO, based on data from WorkSafe's financial reports.

Weekly benefits paid to workers and common law claims are the major contributors to the significant growth of the WorkSafe claims cost and the outstanding insurance claim liabilities. Weekly benefit payments supplement wages when workers are unable to work due to mental or physical injuries. Common law claims arise where workers seek redress through the legal system.

In 2023–24 the liability increased by $2.5 billion (compared with $2.3 billion in 2022–23). The primary contributors to this increase were a 62 per cent increase in the liability for common law claims, offset by a 10 per cent decrease in the liability for weekly benefits for mental injury claims, and a 27 per cent decrease in the liability for weekly benefits for physical injury claims.

The decrease in claim liabilities for mental and physical injuries referred to above was a direct result of the WorkCover scheme reforms through the passing of the Workplace Injury Rehabilitation and Compensation Amendment (WorkCover Scheme Modernisation) Act 2024 on 31 March 2024. This is discussed further below.

WorkSafe's financial sustainability is key to achieving its purpose

Financial sustainability is a key to achieving WorkSafe’s purpose of reducing workplace harm and improving outcomes for injured workers. Rising claim costs from significant increases in claims and workers relying on the benefits for longer have deteriorated the financial sustainability of the WorkSafe scheme in recent years. This has been compounded by the gap between the premium revenue and claims cost (premium deficit).

In our past reports, we highlighted the challenges posed by adverse claims experience and the rising premium deficit, which significantly deteriorated financial sustainability of the scheme requiring the government's financial assistance. We emphasised the need for the government to take measures to ensure WorkSafe's long-term financial sustainability.

The long-term financial sustainability of insurers is measured using the insurance funding ratio, with a preferred range of 100 to 140 per cent for WorkSafe. WorkSafe’s insurance funding ratio was 106 per cent at 30 June 2024 (compared to 105 per cent at 30 June 2023).

In response to financial sustainability challenges, the government:

- approved a substantial premium increase effective from 1 July 2023 raising the average annual premium by 41.7 per cent

- legislated and implemented the scheme modernisation reforms, effective from 31 March 2024.

The premium increase and the implementation of scheme modernisation reforms, further discussed below, are expected to help WorkSafe maintain its insurance funding ratio within the preferred range without additional government assistance.

Insurance funding ratio

Insurance funding ratio is a measure of assets against claim liabilities used as a measure of long-term financial sustainability for a scheme.

WorkCover reforms decreased claim expenses and liabilities by $1.2 billion

On 31 March 2024, the government passed the Workplace Injury Rehabilitation and Compensation Amendment (WorkCover Scheme Modernisation) Act 2024. With that, following key changes came into effect:

- new eligibility requirements for mental injury claims

- an additional whole person impairment requirement for workers to continue receiving weekly payments after the 130-week second entitlement period

- establishment of Return to Work Victoria for supporting injured workers' recovery, rehabilitation and return to work.

WorkSafe expects these reforms to initially stabilise the scheme's claims experience and return its financial performance to a sustainable level in the mid to long term.

The financial impacts of these reforms reduced the claim liabilities at 30 June 2024 and claim expenses for 2023–24 by $1.2 billion. This reduction primarily resulted from reassessment of claims incurred prior to 31 March 2024 that had not yet reached 130 weeks by that date under the new eligibility requirements.

Risks to achieving the 2035 unfunded superannuation funding target

What is the state's superannuation liability?

The state’s public-sector-defined benefit superannuation plans are responsible for the liability for employee superannuation entitlements. These plans are not reported in the AFR because they are not controlled by the state.

The superannuation plans, which are principally operated for GGS employees, are not fully funded. The funding of these superannuation liabilities is the responsibility of the state and therefore a liability is recognised in the AFR for these obligations.

The state's liabilities include a superannuation liability of $18.2 billion at 30 June 2024.

In accordance with the requirements of Australian Accounting Standard AASB 119 Employees Benefits, this liability is valued using a discount rate based on Australian Government bond yields. However, the state's funding requirement is determined using the expected return on the superannuation fund's assets. On this basis, the state's actuarial service provider has estimated an unfunded superannuation liability lower than what is reported in the AFR, at $11.5 billion as at 30 June 2024. The government targets to fully fund this unfunded superannuation liability by 2035 by way of annual contributions, a key financial measure of the government.

The unfunded superannuation liability for funding purposes is lower than the superannuation liability reported in the AFR because the expected return on assets of the superannuation fund is currently greater than the Australian Government's bond yield.

$17.3 billion is required to fully fund the liability by 2035

In the last 5 years the government has contributed around $0.8 billion each year to achieve the funding target. The government deferred annual contributions from 2023 to 2027 by $3.0 billion following the Victorian election in 2022, as outlined in Labour's Financial Statement 2022. The government did not explain why the contribution payments were varied and deferred. However, it keeps its commitment to fully fund the liability by 2035.

The government will need to contribute $17.3 billion (nominal value) from 2024 to 2035 to meet its fully funded commitment. These estimates are based on current assumptions used to determine funding requirements.

Figure 26 shows, more specifically, that under its revised contribution plan, the government plans to contribute approximately $0.5 billion per year over the next 3 years to 2027. This means its annual contribution will need to increase to approximately $2.0 billion from 2028 to meet the full funding target by 2035.

Figure 26: Projected annual superannuation contributions

Note: Averages are shown as horizontal lines.

Source: VAGO, based on DTF.

This contribution deferral will result in the funding position falling below 40 per cent on the funding basis by 2027 as shown in Figure 27.

Figure 27: Projected funding position of superannuation liability on the funding basis

Source: VAGO, based on DTF.

There are several significant risks to achieving this funding target. Rising employee expenses, service delivery costs and interest payments continue to strain the state's fiscal capacity and can compound the challenge of making ongoing contributions.

Furthermore, the current estimate of the liability is subject to external risks, such as the fund's investment performance, salary and pension increases. For example, a lower than expected investment return from the fund’s assets would require more contributions from the government to fully fund the liability by 2035.

Nominal value

Nominal value is the value measured in terms of absolute money amount without taking inflation or other factors into account.

Funding position