Applying the High Value High Risk Process to Unsolicited Proposals

Overview

Effective infrastructure planning and delivery are critical to the state’s future prosperity and liveability. Government introduced the High Value High Risk (HVHR) process to address systematic weaknesses undermining agencies’ performance in managing major projects.

VAGO’s June 2014 HVHR audit called for the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) to apply the HVHR process to unsolicited proposals where the private sector approaches government with a proposal to build infrastructure and/or provide services.

DTF has not consistently applied the HVHR process to unsolicited proposals. DTF’s guidance falls short of ensuring a rigorous assessment of the likely benefits of unsolicited proposals, and of providing the transparency needed to enable affected stakeholders and the wider community to understand the full impacts.

Applying the HVHR process to the CityLink Tulla proposal has not resulted in the information underpinning this project’s approval comprehensively meeting DTF’s better practice guideline.

In contrast, the way in which the HVHR process was applied to the Cranbourne Pakenham interim offer was much better. However, it remains unclear how the absence of elements essential for defining and realising benefits, such as a cost benefit analysis and benefit management plan, would have been addressed to adequately inform government's consideration of a more detailed final offer.

My recommendations are designed to address deficiencies in how the HVHR process is applied to proposals and to improve how agencies scrutinise project benefits, assess funding options and engage affected stakeholders when informing government decisions.

Applying the High Value High Risk Process to Unsolicited Proposals: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER August 2015

PP No 75, Session 2014–15

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Applying the High Value High Risk Process to Unsolicited Proposals.

The audit assessed whether the High Value High Risk (HVHR) process has been effectively applied to two unsolicited proposals—the $1.3 billion CityLink Tulla Widening project and the $2.5 billion Cranbourne Pakenham Rail Corridor project (Cranbourne Pakenham).

I found that the Department of Treasury and Finance has been inconsistent in applying the HVHR process to these proposals.

For the CityLink Tulla Widening project, additional scrutiny had partly or fully assured the project costs, time lines, risks, governance, project management and procurement. However, I found weak assurance about the deliverability of the proposal's benefits, inadequate assessment of the alternative funding options and inadequate engagement with stakeholders about the likely impacts. These weaknesses affected the completeness of the advice provided to government.

The application of the process to the Cranbourne Pakenham interim offer was much better. However, it remains unclear how the absence of elements essential for defining and realising benefits, such as a cost benefit analysis and benefit management plan, would have been addressed if the proposal had proceeded to a final offer.

I have made three recommendations to address deficiencies in how the HVHR process is applied to proposals and to improve how agencies scrutinise project benefits, assess funding options and engage affected stakeholders when informing government decisions.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle MBA FCPA

Auditor-General

19 August 2015

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Ray Winn—Engagement Leader Kate Kuring—Team Leader Sid Nair—Analyst Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Tony Brown |

Well-planned, timely and high-quality infrastructure is essential in shaping a society that is prosperous, liveable and sustainable and this especially applies to Victoria with Melbourne expected to grow from 4.5 million to 8 million people by 2050.

My 2015–16 annual plan has a strong focus on infrastructure because of the scale of this challenge, community concerns over infrastructure provision and repeated, past audit findings highlighting planning and delivery weaknesses.

I am pleased that government has introduced the Infrastructure Victoria Bill in June 2015 to change how it plans and delivers infrastructure. Infrastructure Victoria will:

- develop a 30-year evidence based infrastructure strategy with strong community support as an essential input to setting government priorities, improving intended outcomes and advising on the funding options

- be available to provide independent scrutiny, especially for strategically important, complex, high-value projects, advising on alignment with long-term plans and the rigour of the business case, modelling and other assumptions.

The government's clear intent is that transparency and evidence must underpin infrastructure decision-making so that the community can be properly involved in decisions affecting them, and properly informed about the basis for proceeding.

Following my 2014 audit Impact of Increased Scrutiny of High Value High Risk Projects, government accepted that high value unsolicited proposals should be covered by the High Value, High Risk (HVHR) process. The Department of Treasury and Finance's (DTF) updated guidance integrated the unsolicited proposal, HVHR and Gateway Review processes.

This audit examined the application of this updated approach to two unsolicited proposals already in development—the $1.3 billion CityLink Tulla Widening project (CityLink Tulla) and the $2.5 billion Cranbourne Pakenham Rail Corridor project (Cranbourne Pakenham).

I found that DTF has been inconsistent in applying the HVHR process to unsolicited proposals.

For the CityLink Tulla final proposal, additional scrutiny had partly or fully assured the project costs, time lines, risks, governance, project management and procurement. However, I found weak assurance about the deliverability of the proposal's benefits, inadequate assessment of the alternative funding options and inadequate engagement with stakeholders about the likely impacts. These weaknesses affected the completeness of the advice provided to government.

The application of the HVHR process to the Cranbourne Pakenham interim offer was much better, especially in understanding how well the proposal would address a well-established need. In contrast to the road network, long-term plans for the rail network and the Dandenong corridor, provided a clear basis for assessing the proposal's benefits and risks at this stage of development.

For Cranbourne Pakenham, this information was sufficient to advise government whether the proposal should proceed beyond the interim offer. However, it remains unclear how the absence of a cost benefit analysis and benefit management plan, would be addressed to adequately inform consideration of a detailed final offer.

The way that unsolicited proposals are currently developed is insufficient. While DTF has improved the guidance for unsolicited proposals, it does not provide an adequate basis for applying the HVHR process.

DTF needs to address these deficiencies in the scope and quality of information and ensure that the community is properly involved in decisions and informed about their impacts.

Agencies also need to improve:

- the scrutiny applied to estimating and verifying the benefits of unsolicited proposals at the final offer stage—while there are clear benefits from these projects, we are not assured that agencies have adequately examined the risks and uncertainties that threaten to diminish these benefits over time

- how they assess alternative funding options because for CityLink Tulla we did not find a comprehensive analysis of the costs and benefits of the alternatives

- how they engage stakeholders because of the risk that decisions will be locked in that seriously affect stakeholders without their voice being heard.

Failing to adequately engage the public in developing strategies and projects risks alienating the community and is more likely to lead to poorly informed and implemented decisions. I found that the engagement of stakeholders significantly affected by the CityLink Tulla proposal was inadequate. For example, an approximate doubling of commercial vehicle tolls is likely to significantly impact the operators of these vehicles but they were not adequately consulted on the impacts.

In January 2015 I published a guide on Public Participation in Government Decision-making in the absence in Victoria of guidance to help agencies do this effectively. I encourage public sector agencies to apply the practices in this guide.

Finally, there is an urgent need for evidence-based, long-term infrastructure planning as the essential context for framing project decisions, improving scrutiny of business case assumptions and providing greater transparency to properly engage and inform the community.

I look forward to the implementation of Infrastructure Victoria and I intend to monitor progress towards its goals through my ongoing program of audits.

John Doyle MBA FCPA

Auditor-General

August 2015

Audit Summary

Background

Effective infrastructure planning and delivery are critical to the state's future prosperity and liveability. Government introduced the High Value High Risk (HVHR) process to address systemic weaknesses undermining agencies' performance in developing and investing in major projects.

The goal of the HVHR process is to achieve more certainty about the deliverability of infrastructure projects, including their intended benefits and ability to meet planned costs and time lines. The HVHR process does this by applying greater scrutiny, including a more rigorous review of business cases and procurements.

VAGO's June 2014 audit, Impact of Increased Scrutiny of High Value High Risk Projects, examined the application of the HVHR process to five infrastructure projects. The report concluded that the HVHR process had improved project scrutiny but not to a level where practices comprehensively met the Department of Treasury and Finance's (DTF) better practice guidelines. Significant gaps remained and government was still exposed to the risk of approving projects that would likely fail to deliver the intended benefits on time and on budget.

One of VAGO's recommendations called for DTF to apply HVHR reviews to unsolicited proposals where the private sector approached government with a proposal to build infrastructure or provide services. Unsolicited proposals are underpinned by basic project specifications before being developed into full proposals. In doing this DTF faced the challenge of adapting a process designed for public sector business cases to unsolicited proposals.

DTF accepted this recommendation, provided advice to government in July 2014 and published updated guidance integrating the unsolicited proposal, HVHR and Gateway Review processes in the following month—August 2014.

This audit assessed whether the HVHR process has been effectively applied to unsolicited proposals by examining:

- DTF's advice to government about how to do this

- the application of the HVHR process to two major unsolicited proposals namely:

- the CityLink Tulla Widening project (CityLink Tulla) involving the $1.3 billion expansion of the M1 freeway between the Burnley Tunnel and Tullamarine airport

- the Cranbourne Pakenham Rail Corridor project (Cranbourne Pakenham), a $2.5 billion proposal to expand the capacity of the Dandenong rail corridor and eliminate four major level crossings to reduce traffic delays.

These proposals were well underway when government announced they would be covered by the HVHR process in May 2014 and approved the guidelines for applying the HVHR process to them. HVHR assessments were critical inputs to government decisions in April 2015, when CityLink Tulla was approved for implementation, and in March 2015, when the Cranbourne Pakenham interim offer was rejected, thereby not allowing it to proceed.

Conclusions

DTF has not been effective in consistently and comprehensively applying the HVHR process to unsolicited proposals.

DTF's guidance falls short of ensuring a rigorous assessment of the likely benefits of unsolicited proposals and providing the transparency needed to enable stakeholders and the wider community to understand the full impacts of these proposals. These gaps are significant and evident—to different degrees—in the two unsolicited proposals examined.

Applying the HVHR process to the CityLink Tulla proposal has not resulted in the information underpinning this project meeting DTF's better practice guidelines consistently or comprehensively. When making the decision to support this proposal, government was not fully informed and DTF missed the opportunity to advise about the risks to realising the proposal's benefits and how to mitigate these.

The additional HVHR process scrutiny partly or fully assured the costs, time lines, risks, governance and project management, and procurement of CityLink Tulla. However, there was weak assurance about the deliverability of the proposal's benefits, inadequate assessment of the alternative funding options and inadequate engagement with stakeholders about the likely impacts.

In contrast, the way in which the HVHR process was applied to the Cranbourne Pakenham interim offer was much better. The proposal was subject to rigorous assessment of the costs, time lines, benefits and risks, and DTF fully advised government. This is partly because the evidence-based, long-term plans for the rail network and the Dandenong corridor provided a clear perspective on the problems that needed to be addressed and how the proponent could best contribute to improving services.

However, it remains unclear how the absence of elements essential for defining and realising benefits—such as a cost-benefit analysis and benefit management plan—would have been addressed in the Cranbourne Pakenham final offer.

The often inherent lack of competitive tension in these proposals, the likely long-term costs to the community and the significant impacts on specific stakeholders mean that DTF needs to improve:

- the level of rigour applied to assessing and realising the intended benefits

- the transparency of these proposals by requiring them to clearly communicate value for money, better justify the preferred funding approach and convey how affected stakeholders will be impacted by the proposal's costs and benefits.

The experience with Cranbourne Pakenham reinforces the importance of assessing proposals in the context of a well-developed, long-term planning framework.

Findings

Advice and guidelines on applying the HVHR process

The way that unsolicited proposals are currently developed is unlikely to consistently and comprehensively inform HVHR assessments. While DTF has improved the guidance for unsolicited proposals, it does not provide a comprehensive and adequate basis for applying the HVHR process to them.

The February 2015 Market-Led Proposals Interim Guideline marked a step forward with its commitment to greater transparency and developing a better understanding of the benefits. However, it was not underpinned by the type of detailed guidance and measures needed to do this. This is especially critical where government does not have a longer-term plan that adequately defines need and allows DTF and other agencies to see where a proposal might appropriately fit.

In terms of transparency, government has yet to finalise how it communicates the costs, funding, rationale and expected benefits of committed unsolicited proposals. Current approaches to reporting on infrastructure projects do not adequately convey this information to the community.

DTF publishes more information for public private partnerships (PPP) than for other infrastructure projects in the form of a project summary. However, this summary does not adequately explain the full costs and impacts on stakeholders nor provide sufficient assurance about the rigour of the options assessment. DTF needs to advise government how to better communicate this information for all infrastructure projects including unsolicited proposals.

For example, the private sector proponent will contribute $850 million (in September 2014 dollars) to CityLink Tulla and is expected to recover an equivalent toll revenue stream worth approximately $3.2 billion up to 2035. Providing sufficient detail to stakeholders—including the public—about the funding approach, the nature of payments and how these are calculated, and the impact on different stakeholders are critical aspects of transparency.

In terms of the rigour of advice, the guidelines are unlikely to produce proposals that provide the clarity and depth of information needed to rigorously and consistently assure that proposals' stated benefits are deliverable.

DTF needs to advise government on how to improve the unsolicited proposal guidance, its application and the public sector's role in assessing proposals, in order to:

- ensure that the essential information needed to inform government about the deliverability of a project is produced and verified

- more fully assure Parliament and the community about the rigour of accepted proposals

- better convey the financial and other impacts of the preferred option on government and other stakeholders.

Application to the CityLink Tulla proposal

The application of the HVHR process to CityLink Tulla had significant gaps which DTF needs to address for similar proposals in the future. The lack of sufficient information on the project's benefits, the absence of a full funding analysis and weaknesses in the approach to stakeholder engagement are fundamental gaps which compromise the quality of advice government is entitled to receive.

Benefits

The information provided on the project's benefits and the risks that threaten to undermine their realisation is inadequate. In reviewing the July 2014 draft business case, DTF found the discussion of benefits to be superficial and lacking validation. We agree with this assessment and did not find any material improvement in the information provided in the final April 2015 business case.

The material underpinning the business case identified potentially significant risks to the full realisation of the project benefits, and these risks were not described or mitigated in the final business case.

One area of recurrent concern is the absence of a structured and effective approach to assuring the quality of the transport modelling and the economic appraisal approach and results. Applying these models is complex and checking that assumptions are reasonable and properly applied is essential.

CityLink Tulla motorway. Photograph courtesy of VicRoads.

Over the past six months the Department of Economic Development Jobs Transport & Resources (DEDJTR) has put a governance framework in place to ensure that there are consistent assumptions underpinning the transport modelling and economic appraisal of projects, and that these have been properly applied. The formal processes to check that assumptions have been appropriately applied were agreed in June 2015 and therefore were not applied to the CityLink Tulla proposal.

It is critical that DEDJTR evaluate the effectiveness of these processes in improving the level of rigour and assurance applied to these areas for transport infrastructure projects.

Funding analysis

The value-for-money assessment for CityLink Tulla was narrow and did not incorporate a comprehensive and thorough analysis of the costs and benefits of alternative funding options. During the development process, government requested the assessment of a range of tolling options, in terms of their impacts on transport outcomes and toll revenue, while acknowledging that toll levels should reflect the benefits obtained by travellers and should avoid disproportionate impacts.

The audited agencies have been unable to justify the proposed tolling of goods vehicles as the preferred funding approach. They have not provided a full and objective assessment of a range of alternative funding options.

Stakeholder engagement

The approach to stakeholder engagement has not been satisfactory and the advice to government on stakeholder concerns has been incomplete. A stakeholder engagement strategy was not formed until after the funding approach had been decided.

DTF advised government that there was cautious industry support for funding the project through the proposed goods vehicle toll increases because the industry understands the intended benefits. VicRoads advice to us during the course of the audit was consistent with this DTF advice.

This advice is not consistent with the documentary evidence, especially the strong and public opposition by the major Victorian freight and logistics industry association—the Victorian Transport Association—to the increased tolls. Other freight industry stakeholders publicly supported the project but were not clear that they supported the funding arrangements.

Agencies need to form a stakeholder engagement strategy for government approval early in the unsolicited proposal process. This will formalise decisions on when, how and by whom stakeholders are engaged, while taking account of the risks.

Application to the Cranbourne Pakenham proposal

DTF effectively applied the HVHR process to inform government's decision about whether to proceed with this unsolicited proposal. The assessment described the progress made by the proponent but also the areas where it fell short of meeting the HVHR criteria.

DTF concluded that without an additional 12 to 16 weeks beyond the end of March 2015 deadline for the final offer, it was unlikely to pass the value-for-money and HVHR assessments. In this case, the HVHR assessment clearly fulfilled its role of informing government about whether to proceed with the proposal.

However, the process for developing this unsolicited proposal did not include a cost-benefit analysis or allocate responsibility for developing and applying a benefit management plan. These are mandatory for state-initiated projects and essential for informing government decisions and for tracking and managing benefits after delivery. It is unclear from the current guidelines how these practices should be applied to unsolicited proposals.

The major lessons to draw from Cranbourne Pakenham are:

- the ongoing importance of government decisions being informed by rigorous assessment and thorough information and advice

- the value of proposals' assessment taking place in the context of a comprehensive plan for addressing defined problems in the short, medium and long term

- the dangers of the current ambiguity about the inclusion of essential information in proposals—this needs to be better defined and the responsibility for doing this rests with DTF.

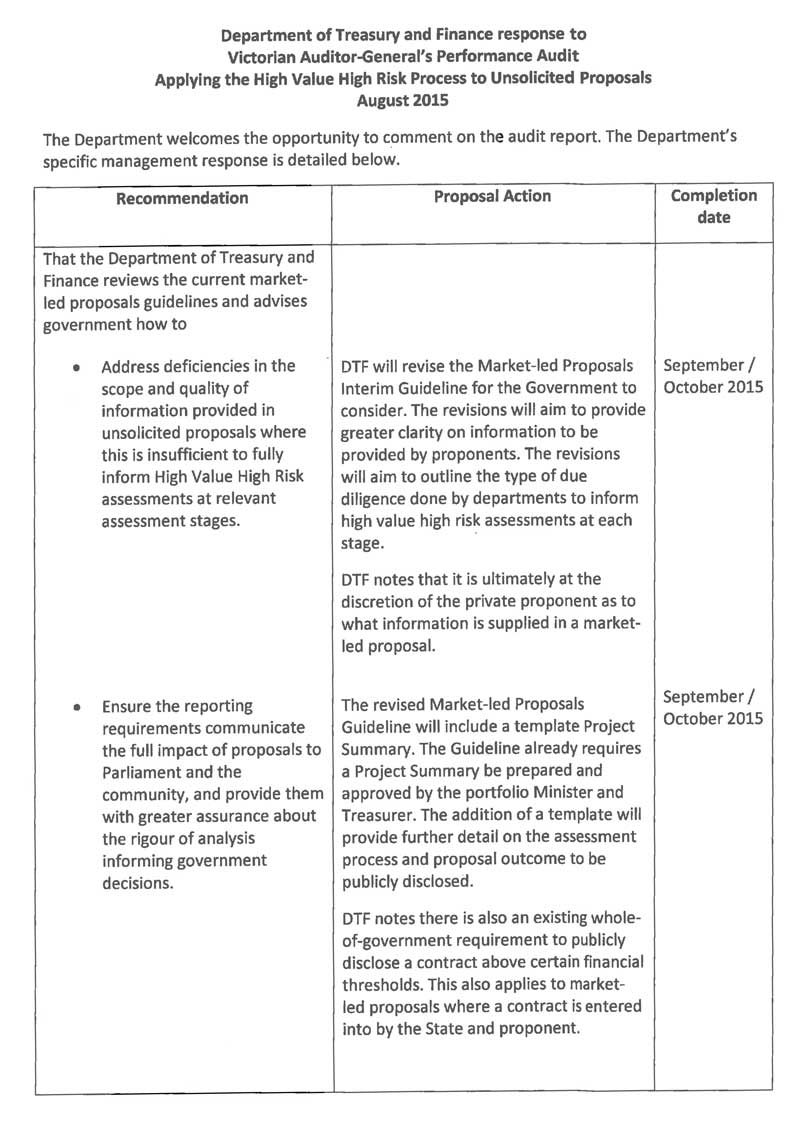

Recommendations

- That the Department of Treasury and Finance reviews the current market-led proposals guidelines and advises government how to:

- address deficiencies in the scope and quality of information provided in unsolicited proposals where this is insufficient to fully inform High Value High Risk assessments at relevant assessment stages

- ensure the reporting requirements communicate the full impact of proposals to Parliament and the community, and provide them with greater assurance about the rigour of the analysis informing government decisions.

- That the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources evaluates the effectiveness of the governance framework recently introduced to assure the quality of transport forecasts and economic appraisals.

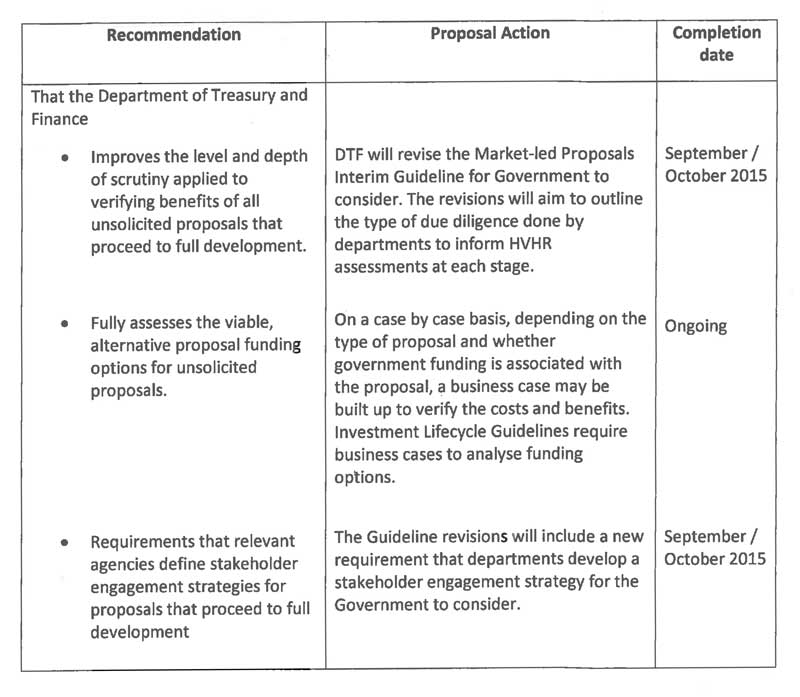

- That the Department of Treasury and Finance:

- improves the level and depth of scrutiny applied to verifying benefits of all unsolicited proposals that proceed to full development

- fully assesses the viable, alternative proposal funding options for unsolicited proposals

- requires that relevant agencies define stakeholder engagement strategies for proposals that proceed to full development.

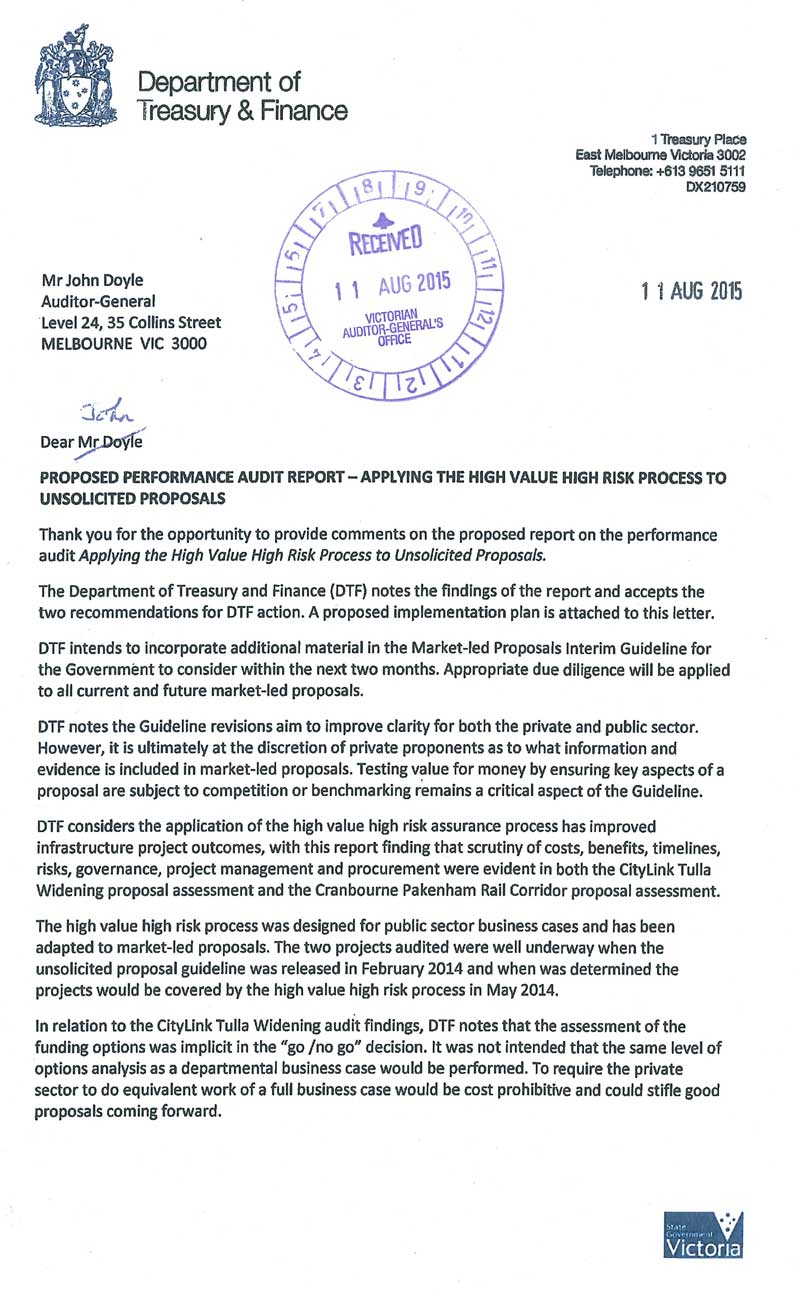

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with the Department of Treasury and Finance, the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources, VicRoads and Public Transport Victoria throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report, or relevant extracts to those agencies and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Effective infrastructure planning and delivery are critical to the state's future prosperity and liveability. Government introduced the High Value High Risk process (HVHR) to address systemic weaknesses undermining agencies' performance in developing and investing in major projects.

This Part of the report:

- outlines the purpose and nature of the HVHR process

- summarises VAGO's previous audit on the HVHR process as applied to traditional, state-initiated projects

- explains how the process has been modified for unsolicited proposals

- describes the scope and conduct of this audit with its focus on how well agencies applied the HVHR process to two major unsolicited proposals.

1.2 The HVHR process

The goal of the HVHR process is to achieve more certainty over the delivery of the intended benefits of infrastructure projects to planned budgets and time lines through more rigorous review of business cases and procurements.

In introducing the HVHR process, the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) advised government that the priority was to:

- enforce the requirement for a robust business case with clear project objectives, well-defined benefits, a rigorous appraisal of options, selection of appropriate procurement methods and appropriate governance and management

- clearly articulate a tender proposal, appointment approach and contract management framework that appropriately allocates and manages risk, delivers benefits and effectively manages scope and cost.

For a state-initiated project, HVHR involves DTF providing additional assurance to the Treasurer at key stages of the project to address these priorities.

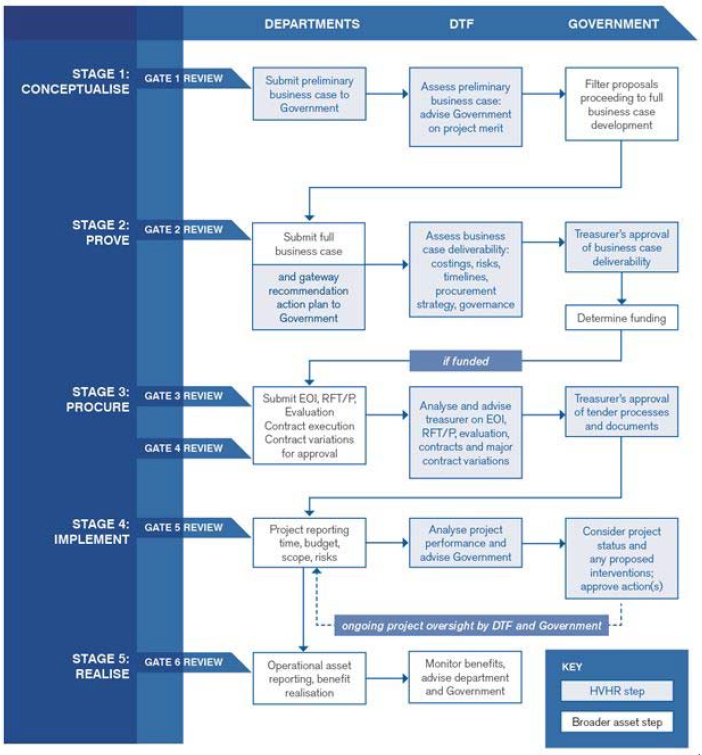

Figure 1A shows, for a state-initiated project, how HVHR is integrated with:

- departmental, quality-assured documentation—justifying the investment and its procurement and implementation approaches

- DTF review and advice to government—advising on the value and complexity of each investment, determining the depth and type of review applied

- the Gateway Review process—examining investments at key decision points and providing advice to the project's senior responsible person.

Figure 1A

Investment review process

Source: Department of Treasury and Finance, Investment Lifecycle and High Value/High Risk Guidelines—Overview, 2014.

1.2.1 VAGO's June 2014 HVHR audit

VAGO first audited the HVHR process and its application to five infrastructure projects in June 2014. The report, Impact of Increased Scrutiny of High Value High Risk Projects, concluded that applying the process had made a difference to the quality of the business cases and procurements of government's infrastructure investments. However, these improvements had not improved practices to the point that they consistently and comprehensively met DTF's better practice guidelines. Significant gaps remained and consequently the government was still exposed to the risk of projects failing to deliver the intended benefits on time and within approved budgets.

A key issue identified in the 2014 audit was a lack of clarity around whether all relevant projects were being included in the HVHR process, including high-risk projects valued between $5 million and $100 million, projects funded outside the typical budget process and projects arising from unsolicited proposals.

VAGO recommended that DTF improve how it:

- administers the process, addressing specific records management issues

- selects projects for inclusion in HVHR, especially for risky projects valued at less than $100 million and for projects generated as unsolicited proposals

- assesses the rigour of project business cases, especially in relation to project benefits

- evaluates the impact of HVHR and communicates learnings to departments.

DTF accepted all recommendations, with completion dates ranging from September 2014 to June 2015 for six recommendations.

In response to VAGO's recommendation that unsolicited proposals valued over $100 million be subject to HVHR processes, DTF committed to review the guideline and advise government by September 2014 on how HVHR should be applied.

1.3 Developing unsolicited proposal guidelines

An unsolicited proposal is one made to government by the private sector to build infrastructure and/or provide services. It involves the private sector seeking government support for proposals based on basic project specifications.

Government wants to realise the benefits of innovative ideas and unique options that offer great value, while continuing to apply rigorous assessment processes to prove these proposals are viable, and be assured that the expected benefits are deliverable within forecast costs and time lines.

The support being sought in these proposals is typically financial but may also include regulatory or other forms of assistance. Government may agree to advance the proposal in exclusive negotiations if the proponent can demonstrate that it alone can best deliver value for money and benefits that are valuable to government but it may also decide to go to a competitive tender process.

Proposals are assessed for uniqueness which might involve a proponent:

- having a unique idea or the use of Intellectual Property critical to the proposal

- holding a unique position or advantage, for example holding the rights under an existing contract, owning land, technology or software, or having exclusive access to or control over strategic assets.

DTF published the first Unsolicited Proposal Guideline in February 2014. The government elected in late 2014 replaced this with the Market-led Proposals Interim Guideline in February 2015. These, together with an August 2014 update about how the HVHR process should be applied to these proposals, are described in the following Sections.

1.3.1 February 2014 Unsolicited Proposal Guideline

This guideline aims to provide 'a transparent framework that sets out a clear and consistent process for project assessment and contracting where private sector parties approach government with an unsolicited proposal'.

The government's objectives for these proposals include:

- developing innovative ideas with the private sector where appropriate

- ensuring an open, transparent and fair process that involves a high standard of probity and public accountability

- incorporating open competition wherever possible

- ensuring value for money for government is achieved

- ensuring projects' benefits for government are measurable and can be maximised

- ensuring the private party's intellectual property is respected and that private parties are fairly compensated as part of the process.

It also stipulates minimum requirements that a proposal will only be pursued where:

- there is a need and appetite for the project that is consistent with government policy objectives and in the public interest

- it is financially, economically and socially feasible and capable of being delivered

- it has a degree of uniqueness that means it could not reasonably be delivered by another private party or achieve the same value for money through a competitive process within acceptable time frames

- it represents value for money and provides benefits to government.

Figure 1B summarises the guideline's five-stage process for achieving these things.

Figure 1B

Summary of Unsolicited

Proposal Guideline process

Stage |

Description |

|---|---|

Stage 1 |

Receiving an unsolicited proposal Defines minimum information required on uniqueness, commercial and financial details, delivery method and the intended benefits for the state and the community. |

Stage 2 |

Preliminary assessment An inter-agency working group is formed to assess:

A recommendation is made to government on whether and how the proposal should proceed. |

Stage 3 |

Developing the proposal in exclusive negotiations Formalise how the proposal will be developed and evaluate, in greater detail, its merits while confirming exclusive delivery and the best form of procurement. Form a steering committee to do this with determining value for money being a key concern at this stage. |

Stage 4 |

Negotiating and finalising a binding offer In making a recommendation, the steering committee should consider the final proposal's value for money, its cost compared to an approved budget, the risk allocation and the impact of any material changes that affect its desirability. |

Stage 5 |

Award contract Enter binding contractual arrangements, agree governance structure and publish a project summary. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.3.2 August 2014 incorporation within HVHR process

Following VAGO's recommendation that unsolicited proposals over $100 million be subject to HVHR, DTF proposed and government endorsed how unsolicited proposals should be integrated with the HVHR and Gateway Review processes.

The HVHR process should be applied to unsolicited proposals that:

- have a total estimated government investment of more than $100 million, or

- are identified as high risk using an approved risk assessment tool, noting that the focus would be on risk to government and residual risk, or

- government determines warrant the rigour of increased oversight.

DTF published a diagram showing the integration to supplement the February 2014 guidance and we examine the quality of this guidance and the analysis underpinning it in Part 2 of the report.

One of the challenges examined in Part 2 is how to apply HVHR requirements designed for conventional state-initiated projects to the process for developing unsolicited proposals. For state-initiated projects, portfolio agencies develop business cases and then tender documentation to inform the HVHR assessment.

In contrast, proponents of unsolicited proposals provide this information in their proposals, with government oversight agencies playing a greater role in helping them define the investment logic and the proposal's benefits. It is intended that the full set of information for the HVHR assessment and to support government decisions is built up throughout the stages both by the private sector and the public sector and generally is developed later in the process than for a conventional state-initiated project.

1.3.3 February 2015 Market-led Proposals Interim Guideline

The Unsolicited Proposal Guideline was updated in February 2015 by the new government which was elected to Parliament in November 2014.

The updated guideline provides more detail on the process but does not fundamentally change government's approach to unsolicited proposals. The objectives are similar and the five-stage approach has been retained.

The government wanted to provide additional transparency by explaining in more detail what the process involved and making some changes to its operation. These changes include:

- encouraging proponents to conduct a pre-submission meeting with government to discuss requirements and information expectations

- more clearly mandating whether a competitive approach should be pursued during the stage 2 preliminary assessment of the proposal

- providing more detail on the criteria used to determine uniqueness and on how value for money would be assessed through both quantitative and qualitative assessments of costs, risks and intended benefits

- more detailed requirements around probity planning

- earlier public disclosure of the unsolicited proposals government is considering.

1.4 Applying HVHR to two unsolicited proposals

May 2014 Budget Papers identified that government was progressing two unsolicited proposals that would be subject to the HVHR process—the CityLink Tulla Widening project (CityLink Tulla) and the Cranbourne Pakenham Rail Corridor project (Cranbourne Pakenham).

Figure 1C summarises the development of these proposals alongside the dates when DTF published its guidelines.

Figure 1C

Time line of process and project development

Date |

Process development |

CityLink Tulla |

Cranbourne Pakenham |

|---|---|---|---|

November 2011 |

Proponent approached state with initial concept |

||

August 2012 |

1. Proposal received |

||

October 2012 |

VicRoads initial due diligence |

||

December 2012 |

2. Preliminary assessment |

||

September 2013 |

Probity and process deed signed |

||

October 2013 |

1. Proposal received |

||

December 2013 |

Unsolicited Proposal Guideline endorsed |

||

January 2014 |

2. Preliminary assessment Proceed to full proposal |

||

February 2014 |

Unsolicited Proposal Guideline published |

||

March 2014 |

Commitment deed executed |

||

April 2014 |

In-principle agreement signed |

||

May 2014 |

May 2014 budget confirms proposals covered by HVHR |

||

June 2014 |

First VAGO HVHR report tabled |

||

July 2014 |

Government considers draft business case for all three sections in

support of sections 1 and 2 |

||

August 2014 |

Government approves process to apply HVHR to unsolicited proposals |

||

September 2014 |

Gateway Reviews 1–4 completed for all

sections of the project |

Gateway Reviews 1–3 completed |

|

October 2014 |

5. Award contract Commonwealth contribution to section 1 confirmed |

Project finalisation agreement 3. Develop full proposal |

|

November 2014 |

State election leads to change of government |

||

December 2014 |

East West Link halted and CityLink Tulla financial close suspended |

||

January 2015 |

Repeat 3. Revise full proposal |

4A. Submit interim offer |

|

February 2015 |

Market-led Proposals Interim Guideline published |

||

March 2015 |

Business case updated for all sections but specifically to support

state-initiated works |

DEDJTR evaluation of offer and DEDJTR/DTF advice on HVHR and alignment

of proposal with rail election commitments |

|

April 2015 |

Government agrees to proceed with the amended CityLink Tulla proposal |

||

Note: DEDJTR = the

Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources.

Source: Victorian

Auditor-General's Office based on DTF documentation.

1.4.1 CityLink Tulla Widening project

This project aims to build capacity, boost performance and improve safety on one of Melbourne's busiest roads.

The government received an unsolicited proposal in August 2012 to widen the CityLink freeway up to Bulla Road, to be funded through increased tolls. The government expanded the project to incorporate state-initiated works which expand the upgrade to cover a total of 23.8 kilometres of the freeway between the Burnley Tunnel and Melbourne Airport.

In October 2014, government entered into a contract for the proposal. Following the November 2014 election, government revised the proposal to take into account the cancelled East West Link project. In April 2015, government signed a contract with the proponent to fund and deliver works between the Burnley Tunnel and Bulla Road and to partly fund works between Bulla Road and Melrose Drive. The section of freeway between Melrose Drive and the airport is jointly funded by the Commonwealth and the state.

CityLink Tulla, Bolte Bridge. Photograph courtesy of Nils Versemann/Shutterstock.com.

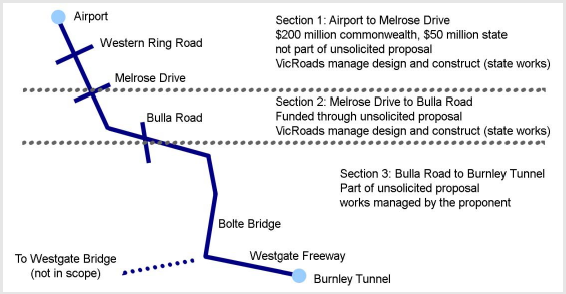

Figure 1D includes the unsolicited work—section 3—and state-initiated works—sections 1 and 2.

Figure 1D

CityLink Tulla scope

Project boundaries  Project scope Works

Costs and funding

Project development and assessment

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information from VicRoads.

1.4.2 Cranbourne Pakenham Rail Corridor project

In March 2014, the government announced the Cranbourne Pakenham Rail Corridor project as the first project to be progressed under the new unsolicited proposal guidelines. The project was a $2 to 2.5 billion—approximately $5 billion in total service payments—initiative to increase capacity on the rail corridor. The proponent under the Project Finalisation Agreement comprised the same entities as the shareholders of the current metropolitan rail franchise.

Figure 1C shows that, a year later in March 2015, government rejected this unsolicited proposal based on an evaluation of the interim offer which raised issues about the project's alignment with the government's broader transport policy commitments.

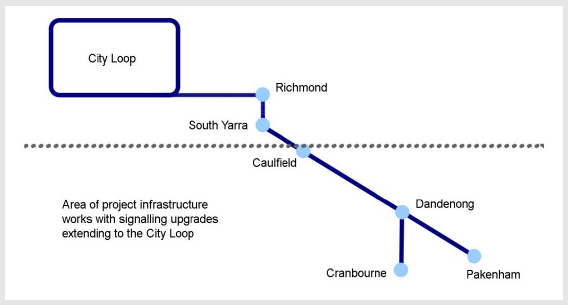

Figure 1E describes the proposal scope.

Figure 1E

Cranbourne Pakenham scope

Cranbourne and Pakenham lines  Project scope Works

Procurement

Cost

Project development and assessment

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information from DTF.

1.5 Audit objective, scope and criteria

The objective of this audit was to assess whether the HVHR process has been effectively applied to unsolicited proposals identified as HVHR projects by examining:

- DTF's advice to government about how to apply HVHR to unsolicited proposals

- the application of HVHR to the CityLink Tulla and Cranbourne Pakenham unsolicited proposals.

Government identified these proposals as subject to the HVHR process in the May 2014 Budget. We viewed the application of HVHR to these proposals as critical given their size, innovative development and procurement approach, which involved negotiations with single proponents.

In examining CityLink Tulla, we extended the scope of this audit to cover the application of the HVHR process to both the unsolicited proposal and state-initiated works because these components, and the material supporting their development and funding, are so closely connected. The audit time frame spanned the period of proposal negotiation and assessment conclusion for both unsolicited proposals.

The government agencies engaged in this audit were the Department of Treasury and Finance, the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources, VicRoads and Public Transport Victoria.

1.6 Audit method and cost

The audit team reviewed the documents held by the audited agencies and those generated by the government's consideration of the projects. The team also interviewed personnel responsible for the review and oversight of these projects.

The audit was conducted in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards.

Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of the audit was $485 000.

1.7 Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines the advice provided to government by DTF in applying VAGO's June 2014 recommendation about how unsolicited proposals should be subject to the HVHR process

- Part 3 examines the HVHR process as applied to the CityLink Tulla proposal

- Part 4 examines the application of the HVHR process to the Cranbourne Pakenham proposal.

2 Integrating the HVHR and unsolicited proposal processes

At a glance

Background

This Part examines whether the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) has adequately responded to VAGO's June 2014 recommendation to advise government on including unsolicited proposals in the High Value High Risk (HVHR) process.

Conclusion

DTF has improved the guidance for unsolicited proposals. However, the way unsolicited proposals are currently developed is unlikely to provide all the information needed to inform an HVHR assessment. Proposals developed in line with the guidance are unlikely to provide the clarity or depth of information required about project benefits to be assured of a projects deliverability. They are also unlikely to provide sufficient transparency to assure the community about the rigour of the process.

Findings

- DTF acted swiftly in August 2014 to implement VAGO's audit recommendation, but the resulting guidance and supporting analysis did not provide a comprehensive and effective basis for applying the HVHR process to unsolicited proposals.

- The Market-Led Proposals Interim Guideline places more emphasis on developing a good understanding of benefits but fails to explain how to do this.

- There is a lack of clarity about who is responsible for defining benefits and an ongoing risk that government decisions will not be adequately informed.

Recommendations

That the Department of Treasury and Finance advises government how to:

- address deficiencies in the scope and quality of information in unsolicited proposals where this is insufficient to fully inform HVHR assessments

- ensure the reporting requirements communicate the full impact of proposals to Parliament and the community, and provide them with greater assurance about the rigor of the analysis informing government decisions.

2.1 Introduction

This Part examines whether the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) has adequately responded to VAGO's June 2014 recommendation to subject unsolicited proposals over $100 million to the High Value High Risk (HVHR) process, by providing government with clear advice based on a comprehensive analysis of the issues.

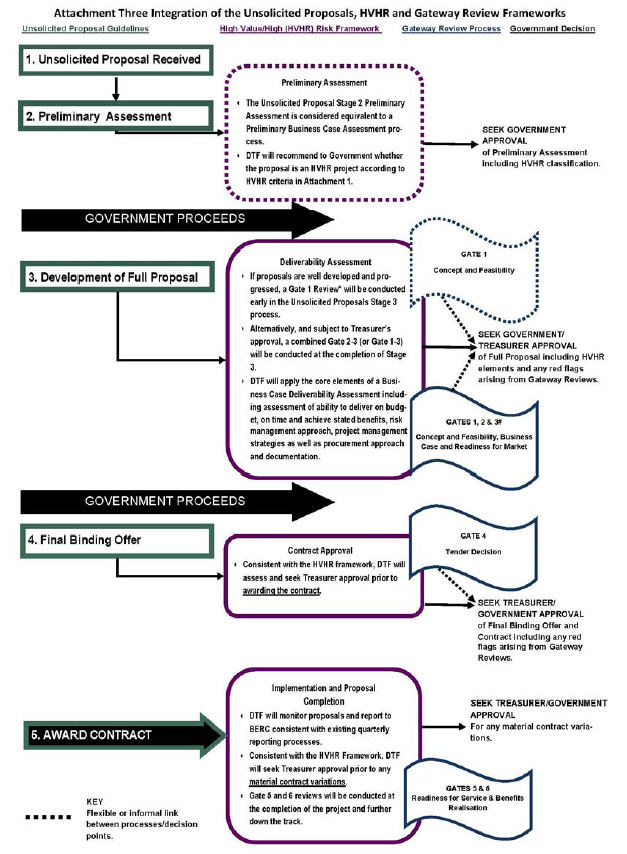

In August 2014, government approved that the criteria used to include state-initiated projects in the HVHR process should be applied to unsolicited proposals. DTF presented government with a diagram to show how the unsolicited proposal, Gateway Review and HVHR processes would be integrated and this is included as Figure 2A.

In February 2015, the new government asked DTF to revamp its guidelines and communicated them in the Market-led Proposals Interim Guideline. Figure 1A in the Background Part of this report describes the major changes.

This Part of the report describes the challenges of applying the HVHR process to unsolicited proposals and assesses the clarity and comprehensiveness of the changes made to the guideline to incorporate the HVHR process.

2.2 Conclusion

The way that unsolicited proposals are currently developed is unlikely to provide all the information needed to inform an HVHR assessment. Unsolicited proposals do not typically define their intended outcomes in terms of the service benefits delivered to the community, prove that these benefits will be achieved, or encompass the full range of risks that are relevant to government. This contrasts with a full business case for a conventional, state-initiated project, which requires all of this information.

While DTF acted swiftly in August 2014 to implement VAGO's June 2014 audit recommendation, it missed the opportunity to properly address this issue when advising how best to integrate unsolicited proposals with the HVHR process.

The February 2015 Market-Led Proposals Interim Guideline represents an important step in the right direction. It places more emphasis on developing a good understanding of the benefits, however, it fails to explain how this is to be achieved. There is a lack of clarity about who is responsible for identifying benefits and there is a continued risk that government decisions will not be adequately informed by detail of the expected benefits.

DTF needs to advise government how to address this gap and supplement its guidance so that agencies and potential proponents are aware of the requirements and their responsibilities.

2.3 Challenges in applying the HVHR process

The requirements for informing government decisions on supporting projects should be the same irrespective of whether it is a government-funded project developed by a department through the budget process or an unsolicited proposal initiated outside of government. Government needs to have confidence that a project will deliver clearly defined benefits for Victorians for the estimated cost and within expected time lines, while effectively managing the risks.

Over the past decade DTF has worked to improve the way state-initiated projects are developed because this is critical to fully informing government decisions and delivering successful projects. The Investment Lifecycle Guidelines and more recently the HVHR process are designed to help agencies better define, develop and deliver predictable and valuable projects.

The private sector is likely to be focused on its own commercial interests in generating a proposal. This creates the risk of a diminished focus on understanding, defining and realising the service outcomes (or benefits) critical to the community. A recurrent finding across a wide range of VAGO audits is that agencies are poorly demonstrating the benefits of projects.

DTF advised that it is aware of these issues and does not expect proponents to incorporate the same breadth of information in the early stages of the project development process. Private proponents are likely to be wary of investing too much up front when it is uncertain whether government will support their proposals. Instead DTF understands that more of the essential groundwork will happen later in the process for these proposals compared to conventional state-initiated projects.

DTF is also aware that proponents are likely to focus on the costs, risks and timing of the outputs they plan to deliver. DTF sees a role for portfolio agencies in helping shape and clarify the connection between these outputs and the improved service outcomes that are the final goal and of most importance to government. In turn, there is a role for DTF in undertaking HVHR reviews of proposals to ensure that this work has taken place and that the service outcomes and benefits are clearly demonstrated before government commits its support.

The highest standards of transparency need to be applied to proposals because:

- project ideas are generated by private companies that are commercially driven

- confidentiality concerns mean these ideas may be developed without the same level of stakeholder engagement as conventional state-initiated projects have.

DTF has not yet finalised the reporting requirements. However, simply replicating the information provided in recent summaries for public private partnership projects is unlikely to adequately convey the full costs and impacts on stakeholders, or provide assurance about the rigour of the option's assessment.

The unsolicited proposals included in this audit experienced these challenges and we expected DTF to advise government about these issues and provide clarity about how applying HVHR would address them.

2.4 August 2014 update of the guidelines

DTF updated its guidance in August 2014 by publishing Figure 2A, showing the integration of the unsolicited proposal and HVHR requirements. However, it could not demonstrate that this work included a comprehensive analysis of the risks and issues around the completion of HVHR assessments for unsolicited proposals. The advice to government did not adequately convey how these risks should be mitigated.

2.4.1 Analysis underpinning DTF's advice

The documents describing DTF's work to address VAGO's June 2014 recommendation are insufficient for us to see that it comprehensively analysed the issues.

DTF advised that it considered the risks and practical challenges in applying the HVHR process to unsolicited proposals and how to overcome them, by exploring:

- how to best align the HVHR and Gateway Review processes with the stages of assessment and delivery in the Unsolicited Proposal Guideline

- criteria to classify unsolicited proposals as HVHR, including by the size and type of contribution from government and by the scale and type of risks that government would be exposed to.

From the documentary evidence provided, DTF could demonstrate that it:

- consulted with the DTF HVHR committee in June 2014

- consulted with the Unsolicited Proposals Interdepartmental Committee(IDC) in July 2014, presenting a draft diagram for integrating the Gateway Review, HVHR and unsolicited proposal review processes

- further consulted the IDC to confirm a revised approach as shown in Figure 2A

- presented to and gained government's approval for this approach in August 2014

- published Figure 2A on its website where it remains a current document.

However, these documents did not show that DTF examined the practical challenges of applying the HVHR process to unsolicited proposals.

We did not find evidence showing how DTF determined that the existing criteria for including state-initiated projects in the HVHR process should be applied to unsolicited proposals. The effectiveness of this approach depends on the thorough application of a risk assessment tool for proposals requiring less than $100 million in state funding as these are not automatically subject to HVHR processes.

2.4.2 Advice to government

DTF provided advice to government in August 2014 recommending an approach to apply HVHR assessment to unsolicited proposals. This advice took the form of Figure 2A together with a brief providing the background and rationale for the proposed approach.

The main problem with the advice is that it did not raise the practical challenges of applying the HVHR criteria to unsolicited proposals and did not describe how DTF would address these challenges.

Figure 2A

Integration of the unsolicited proposals, HVHR and Gateway Review processes

Source: Department of Treasury and Finance.

2.5 February 2015 market-led proposals guideline

Changes in the 2015 Market-led Proposals Interim Guideline have the potential to address the issues we have identified by providing more direction on building a robust case for investment and how these will be assessed. However, the guidance still lacks detail around defining the intended outcomes and allocating clear responsibility between the proponent and government agencies for their achievement.

Under the revised guidelines:

- proponents are required to articulate the benefits of interest to the state, including how the proposal is in the public interest, at Stage 1—the initial proposal

- government must complete a qualitative and quantitative assessment of value for money that includes verifying these benefits at Stage 4—negotiating and finalising a binding offer.

An HVHR assessment of an unsolicited proposal should provide assurance about the deliverability of the intended benefits and the risks that threaten their realisation. It remains unclear who is responsible for generating the information needed to gain this type of assurance.

In presenting the revised guideline to government for approval, DTF did not specifically raise the significant difficulties in practically translating aspects of the HVHR assessment to unsolicited proposals. The advice highlighted the following key lessons from administering the previous guidelines with the need to better:

- explain to proponents how to show their proposals are unique, offer value for money and align with government priorities

- manage proponents' expectations, and draw their attention to the possibility that proposals may not proceed

- consult with government prior to submission to improve proponents' process understanding.

DTF recognises the need to learn from the early unsolicited proposals and improve the process to address clear gaps and weaknesses. As at 30 June 2015 DTF advised us that of 45 proposals received, only five proposals have proceeded past Stage 2 and only one proposal has progressed to contract award at Stage 5. As a result, there have been limited opportunities to learn lessons from the early implementation.

However, for those proposals that do progress, DTF recognises that it needs to address the issues around the clarity and assurance of the benefits that will be delivered to the community. Unsolicited proposals, like conventional state-initiated projects, need to:

- clearly define the investment logic, linking the proposal to the problems that need addressing and the benefits to the community that are valued by government

- develop an understanding of these problems and benefits to a depth and quality equivalent to what is meant to be provided in a final business case.

DTF needs to advise government about how best to do this so that quality information is available in time to inform its decisions throughout the proposal development.

Recommendation

- That the Department of Treasury and Finance reviews the current market-led proposals guidelines and advises government how to:

- address deficiencies in the scope and quality of information provided in unsolicited proposals where this is insufficient to fully inform High Value High Risk assessments at relevant assessment stages

- ensure the reporting requirements communicate the full impact of proposals to Parliament and the community, and provide them with greater assurance about the rigour of the analysis informing government decisions.

3 CityLink Tulla Widening project

At a glance

Background

This Part examines whether the High Value High Risk (HVHR) process has been effectively applied to the CityLink Tulla Widening project (CityLink Tulla) to provide rigorous and comprehensive advice to government about whether and how the proposal should proceed.

Conclusion

Applying HVHR has not resulted in the information underpinning the project's approval consistently and comprehensively meeting the Department of Treasury and Finance's better practice guidelines. These gaps are significant and mean that government decisions on CityLink Tulla were not adequately informed.

Findings

- The additional HVHR scrutiny improved assurance about costs, time lines, risks, governance, project management, and procurement, but significant gaps remain.

- The lack of sufficient information on the project's benefits, the absence of a full funding analysis and weaknesses in the approach to stakeholder engagement are fundamental gaps that compromise the quality of advice government is entitled to receive.

Recommendations

That the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources:

- evaluates the effectiveness of the governance framework recently introduced to assure the quality of transport forecasts and economic appraisals.

That the Department of Treasury and Finance:

- improves the level and depth of scrutiny applied to verifying benefits of all unsolicited proposals that proceed to full development

- fully assesses the viable, alternative proposal funding options for unsolicited proposals

- requires that relevant agencies define stakeholder engagement strategies for proposals that proceed to full development.

3.1 Introduction

This Part examines whether the High Value High Risk (HVHR) process has been effectively applied to the CityLink Tulla Widening project (CityLink Tulla) to provide rigorous and comprehensive advice to government about whether and how the proposal should proceed.

In this Part we assess the quality of the advice given about the proposal's deliverability and procurement, including whether government can be assured the proposal will be:

- delivered on budget

- delivered on time according to realistic time frames

- successful in delivering and sustaining the intended benefits

- comprehensively risk managed

- governed and managed effectively

- procured in a way that represented value for money by delivering intended benefits according to planned time lines and costs.

Our analysis covers both the unsolicited proposal—focused on the southern tolled section of the freeway—and the state-initiated works—between Bulla Road and Melbourne Airport—because of the connections and dependencies linking these components.

In October 2014, the previous government decided to proceed with the unsolicited proposal based on advice that it met the HVHR deliverability and procurement criteria. The change of government in November 2014 stopped the execution of this decision. However, in April 2015 the new government decided to proceed with the proposal and the state-initiated works based on a final business case, updated value-for-money assessment and a final HVHR assessment confirming the project's deliverability.

3.2 Conclusion

Applying the HVHR process has not resulted in the information underpinning the project's approval consistently and comprehensively meeting the Department of Treasury and Finance's (DTF) better practice guidelines. While the additional HVHR scrutiny improved assurance about costs, time lines, risks, governance and project management, and procurement, significant gaps remain.

These gaps and shortfalls in information include:

- the lack of sufficient information on the project's benefits, reliability and the risks that threaten to undermine its sustainability and realisation

- the narrowness of the value-for-money assessment and the lack of a comprehensive analysis of the costs and benefits of alternative funding options

- an inadequate approach to stakeholder engagement and the lack of a clear, coherent and endorsed engagement strategy early in the proposal's development.

These gaps are significant and mean that agencies have not fully informed government of the full range of issues and risks relevant to its decision-making.

3.3 Overall assessment

We tested the quality of the assurance provided by the HVHR review of CityLink Tulla against the criteria set out in relevant Investment Lifecycle and High Value/High Risk Guidelines criteria. Our assessment is based on the documentation provided by DTF, VicRoads and the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR). DTF assessed the HVHR criteria as assured and Figure 3A describes our assessment against these criteria.

Agencies applied the greatest amount of scrutiny and achieved partial or full assurance for project budgets, time lines, governance and project management, and procurement. In contrast, there are unaddressed issues that prevent us from being fully assured about the deliverability of benefits. These issues vary in their significance and are described in greater detail within the body of this Part.

However, we found a lack of assurance for the delivery of intended benefits. The documentation used to justify the project did not adequately explain the benefits, their distribution across stakeholder groups or the risks to their scale and sustainability. DTF applied insufficient scrutiny to test the project benefits and so the deficiencies of earlier business cases were not addressed in the final advice that informed government's decision to approve the project in May 2015.

Apart from the project benefits, there were other significant gaps in analysis and advice, including the inadequate:

- assessment of alternative funding options and communication of the impacts for stakeholder groups and government's wider policy objectives

- approach to consultation in terms of defining a clear approach to stakeholder engagement at the outset of the process, and adequately consulting affected groups on the impacts of locked in decisions.

Figure 3A

VAGO's assessment of final offer and business case against HVHR requirements

|

Deliverability criteria |

State-initiated works |

Proposal |

|---|---|---|

|

Deliver on budget—assurance about costs |

✔✔✔ |

✔✔✔ |

|

Deliver to planned time lines |

✔✔✔ |

✔✔✔ |

|

Deliver intended benefits |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Comprehensively manage risks to benefits |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Comprehensively manage other risks |

✔ |

✔✔✔ |

|

Governance and project management |

✔ |

✔✔✔ |

|

Procure for best value for money |

✔ |

✔ |

Note: ✔✔✔ = Fully assured—Project documentation and advice to government fully addresses Investment Lifecycle and HVHR Guidelines and provides a high level of assurance.

✔= Partly assured—Evidence that HVHR reviews improved the level of assurance while not fully addressing all issues. The significance of outstanding issues varies from relatively minor—business case is not updated with additional evidence—to more significant—where material issues are not raised or addressed. We provide a commentary on the issues.

✘ = Not assured—Insufficient evidence to be assured about the deliverability of the project.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

3.4 Deliver on budget

For a project to pass this HVHR criterion, DTF needs to be confident that estimated costs are based on a verified and detailed understanding of base costs, with evidence-based allowances for contingencies and risks. Costs should be:

- appropriately structured, clearly describing capital and ongoing whole-of-life costs and distinguishing base cost, base risk and contingency risk allocations

- reliable by being:

- based on a clear and appropriately defined project scope and design

- estimated by competent estimators and checked against benchmark data

- estimated using a recognised and rigorous approach to costing

- subject to a robust review process.

Figure 3B shows that we found that reviews of the project's costs had improved assurance. We found the level of assurance to be greater for the state-initiated works than for the unsolicited proposal. Figure 3B describes the outstanding issues.

Figure 3B

Findings on delivering on budget

|

Rating |

Reasons |

|---|---|

|

State-initiated works (sections 1 and 2) |

|

|

Fully assured |

|

|

Unsolicited proposal (section 3) |

|

|

Fully assured |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

3.5 Deliver on time

The Investment Lifecycle and HVHR Guidelines require the business case to include a detailed and realistic project implementation schedule that encompasses key milestones, decision points and delivery events. It also requires information on competing priorities, dependency analysis, required skills and capabilities, the availability of agency staff and on the public communication of time lines.

Figure 3C shows that we rated the reviews as providing full assurance for all three sections of the project. The combined procurement of sections 1 and 2 puts pressure on achieving the target completion date for section 2. However, we are assured that sufficient mitigation measures are in place, including clear requirements embedded in the contract that allocate the risk of achieving this completion date to the contractor.

Figure 3C

Findings on project time lines

|

Rating |

Reasons |

|---|---|

|

State-initiated works (sections 1 and 2) |

|

|

Fully assured |

|

|

Unsolicited proposal (section 3) |

|

|

Fully assured |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

3.6 Achieving the intended benefits

3.6.1 Overall assessment

Delivering benefits to the community is the key reason for investing in public infrastructure. Managing projects to realise, sustain and maximise benefits is therefore essential. This requires an evidence-based understanding of the expected benefits, their distribution and the risks to their realisation, together with clear advice about how best to address these risks.

There is sufficient evidence for us to see that this project is likely to deliver significant, net benefits to car travellers. However, proving the intended benefits and comprehensively assessing and advising government about the risks, are the weakest parts of the HVHR assessment. This replicates the findings from our 2014 HVHR audit, meaning that assuring the delivery of intended benefits continues to be the weakest link in the application of the HVHR process.

Figure 3D shows a 'not assured' rating for the HVHR review of benefits in relation to both the state-initiated works and the unsolicited proposal. Further details on these findings are in Sections 3.6.2 and 3.6.3.

Figure 3D

Overall findings on project benefits

|

Rating |

Reasons |

|---|---|

|

Not assured |

DTF concluded, for all sections of the project, that the proposed solution is an effective way to respond to the problem and deliver the expected benefits. DTF based this conclusion primarily on the content of the final business case. The weaknesses that undermine our confidence in the information presented to government in the business case and in HVHR reviews are:

The business case explained and quantified, at a high and aggregated level, the project's benefits. The absence of information on the impact of uncertainties and critical risks means that a balanced assessment or the opportunity for government to understand and possibly mitigate these risks was not provided. The documents underpinning the project development identified risks and uncertainties in relation to the project benefits. None of these risks were identified and reviewed in the final business case, HVHR assessments or the briefing papers provided to government. In its HVHR analysis of the April 2015 business case, DTF stated that, based on experience on recent similar road upgrades, it was satisfied that there was sufficient evidence provided to substantiate that the project will address the identified problems and deliver the intended benefits. We did not find documentary evidence showing the DTF analysis supporting this conclusion. The absence of sufficient scrutiny in this area is a critical shortfall that DTF needs to address if government is to make fully informed decisions. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

3.6.2 Understanding the problems and benefits

The Investment Lifecycle and HVHR Guidelines require proponents to define and measure the problems being addressed and the intended benefits. Agencies need to:

- show that they understand the causes and effects of the problems driving the investment, including the groups affected and the nature of these problems

- clearly define the project's benefits and any likely disadvantages, describing the impacts on different stakeholders and how they intend to measure and report on the achievement of the project's objectives.

Agencies have not demonstrated a thorough understanding of the problems and expected benefits essential to informing decisions about if and how the project should proceed and providing confidence that the outcomes will be monitored and managed.

Understanding the problems driving the project

The definition of the problem in the draft and final April 2015 business cases is at too high a level to fully convey the evidentiary basis for the project and its expected positive and potentially negative impacts.

We acknowledge that detailed documentation supporting the business case, such as the detailed traffic impact assessment for section 3, partly fills this gap. However, the key findings from this analysis have not been adequately conveyed in the business case. It does not describe the congested locations, on or adjacent to the project, where the assessment identifies the risk that current problems may persist or intensify after implementing the project.

Figure 3E illustrates this lack of detail, using road safety as an example.

Figure 3E

Scrutiny of the current and expected safety problems

|

The final business case describes the road safety problems by tabulating the number of casualty crashes between 2009 and 2013 for the project, divided into four sections. The project is designed to increase capacity, creating additional traffic lanes by narrowing existing lanes and using the emergency lane to convey traffic, while also improving safety through the provision of additional capacity and by introducing a Managed Motorway System to better control and smooth traffic flows. In our view the information provided in the business case about the potential impacts of the project on road safety is inadequate. We expected the business case to convey the results of a detailed and forensic examination of the pattern and characteristics of current road crashes together with an assessment of the full range of expected impacts resulting from the project. VicRoads provided us with a report by the toll operator that did this but did not include this information in the business case. From examining additional material outside of the business case we found that the net impact of these measures is likely to make the road safer. However, VicRoads' contractor advised considering the use of the Managed Motorway System to close the shoulder or what was previously an emergency lane in the inter and off-peak periods for use by emergency vehicles and as a refuge for vehicles that break down. More information on road safety together with a consideration of the options for flexibly operating the improved road should have been included in the business case. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on material from VicRoads.

Defining and monitoring the project's expected benefits

Agencies did not address DTF's July 2014 review findings that the draft business case:

- discussion of anticipated benefits was superficial and lacks validation through the provision of supporting evidence

- did not include a benefit management plan that adequately explained how expected benefits would be monitored and managed.

We agreed with these findings and the April 2015 final business case did not address them. Despite this, DTF did not raise them in advising government on the project's performance against the HVHR criteria.

The April 2015 business case is inadequate because:

- benefits are presented as aggregate, discounted monetary sums with insufficient detail on the travel time, operating cost, reliability and safety changes underpinning these estimates and the impacts on different stakeholders

- it is unclear how long it is likely to be before rapid traffic growth significantly erodes the travel time and reliability benefits provided by the project

- it does not describe the potential disadvantages of:

- greater traffic volumes affecting congestion upstream or downstream of the project

- making commercial vehicles bear the majority of the project cost through increased tolls and how this affects commercial vehicle productivity

- the operation of ramps and junctions with ramp metering and increased traffic.

The final business case includes an expanded benefit management plan. However, we are not assured of its quality because we are not convinced that:

- measures are appropriate—for example, measuring average travel times and travel time variability over a three- to four-hour period for trips traversing the entire project will not be sufficient to understand and manage emerging impacts

- targets are soundly based—they are not explained and stop after five years

- targets and measures are comprehensive—absence of measures for individual ramps and sections to show localised problems and bottlenecks

- a detailed plan is in place for how data will be generated, analysed and reported

- sufficient information will be collected to understand the safety impacts.

3.6.3 Reliability of the traffic and benefit estimates

VAGO's 2011 audit on the Management of Major Road Projects concluded that VicRoads had fallen short of the standards required to reliably forecast traffic and estimate projects' economic benefits when informing government decisions. We viewed addressing these weaknesses as critical because decisions had been reached without a full appreciation of the likely consequences.

While VicRoads has improved its approach to forecasting traffic and estimating economic benefits, it still lacks a structured and transparent approach to quality-assuring the results. In addition the CityLink Tulla business case did not explain how significant forecasting uncertainties are being managed. DTF did not scrutinise these issues.

Quality assurance

None of the versions of the business case adequately explain how the application of the transport model and the economic appraisal framework were quality assured.

The review comments from DTF and the former Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure reveal a superficial examination of the traffic forecasts and economic benefits. This was insufficient to verify these have been:

- based on reasonable approaches consistent with national and state guidelines

- applied and calculated as intended.

In past audits on the management of major road and rail projects, the absence of structured and rigorous quality assurance by portfolio and central agencies allowed significant errors and inconsistencies to go undetected.

Transport modelling and economic benefit uncertainties