Effectiveness of Justice Strategies in Preventing and Reducing Alcohol-Related Harm

Overview

The audit assessed the effectiveness of the Department of

Justice, Victoria Police and the Victorian Commission for Gambling

and Liquor Regulation in preventing and reducing the impact of

alcohol-related harm on the community.

Alcohol-related harm costs Victoria an estimated $4.3 billion per

year.

Despite the implementation of various strategies and

initiatives, the level of reported alcohol-related harm has

increased significantly over the past 10 years.

Harm minimisation efforts have been hampered by the lack of a

whole-of-government policy position on the role of alcohol in

society, by poorly chosen, implemented and evaluated initiatives,

by inconsistent and cumbersome liquor licensing processes and

legislation, and by a lack of coordinated, intelligence-led and

targeted enforcement.

The Department of Justice's initiatives to prevent and reduce alcohol-related harm were fragmented, superficial and reactive instead of targeted, evidence-based, complementary and well coordinated.

The liquor licensing regime is not effectively minimising alcohol-related harm. This is due to a lack of transparency in decision-making, insufficient guidance on regulatory processes, administrative errors, poor quality data and a lack of engagement from councils.

There is no overarching whole-of-government enforcement strategy to comprehensively address unlawful supply, particularly service to intoxicated patrons and minors, which is the cause of much alcohol-related harm. Inaccurate and incomplete data is further hampering enforcement efforts.

A fundamental change in approach to strategy development, licensing and enforcement is required before any noticeable impact on reducing harm is likely.

Audit summary

Background

Alcohol is a widely accepted part of Australian culture and generates positive impacts for the state in the form of revenue and employment. The number of liquor licences has more than doubled since the Liquor Control Reform Act 1998 was introduced. There are now over 19 000 active liquor licences in Victoria.

However, the misuse of alcohol can result in significant short-term and long-term harm for individual drinkers, their families, friends and the wider community.

Besides the detrimental effects of intoxication on health—injuries, violence, disease and death—risky levels of alcohol consumption have broader social and economic implications. A report commissioned by the Department of Justice (DOJ) estimated that the social cost of alcohol-related harm to Victoria in 2007–08 was $4.3 billion. Approximately $366 million of this, or 9 per cent of the total, was borne by the government, predominantly through policing and health services.

The Department of Health (DOH) has a coordinating role for whole‑of‑government alcohol policy development. However, DOJ, the Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation (VCGLR) and Victoria Police all have important roles in preventing and reducing alcohol-related harm, primarily through legislation, regulation of the liquor and licensed hospitality industry, and enforcement.

The audit assessed the effectiveness of DOJ, Victoria Police and VCGLR’s initiatives and actions in:

- enforcing controls on the sale and marketing of alcohol

- preventing and reducing the impact of short-term alcohol-related harm on the community.

Conclusions

The level of reported alcohol-related harm has increased significantly over the past 10 years. Alcohol-related ambulance attendances in metropolitan Melbourne more than tripled between 2000–01 and 2010–11, and alcohol-related assaults in Victoria increased 49 per cent. The rate of the increase in harm has slowed in recent years, but the number of reported incidents continues to rise.

Combating alcohol-related harm is challenging and costly. The underlying causes are complex and there are numerous public and private sector stakeholders involved, many with competing interests. Although alcohol can be harmful, over 80 per cent of adults drink. Some types of licensed premises have a stronger association with alcohol-related harm than others. This presents significant challenges for agencies in policy and strategy development.

For instance, there is clear evidence to indicate that strategies that increase the price and restrict the availability of alcohol are effective in reducing harm. However, these types of measures tend to be unpopular with the public because they increase costs and create inconvenience.

Various strategies and initiatives to prevent and reduce harm have been implemented, most notably since 2008. However, these efforts have been hampered by:

- the lack of a whole‑of‑government policy position on the role of alcohol in society

- poorly chosen, implemented and evaluated initiatives

- inconsistent and cumbersome liquor licensing processes and legislation

- the lack of coordinated, intelligence-led and targeted enforcement.

Instead of a coherent strategic framework consisting of a suite of targeted, evidence‑based, complementary and well-coordinated initiatives, DOJ’s alcohol initiatives have been largely fragmented, superficial, and reactive. Their lack of effectiveness is demonstrated by the same issues—such as the prevalence of under‑age drinking—persisting year after year, despite being highlighted in consecutive strategies as areas of particular focus.

The liquor licensing process is complex, inconsistent and lacks transparency. Since 2009, the primary objective of the Liquor Control Reform Act 1998 has been to minimise alcohol‑related harm. However, the Act also requires liquor licensing decisions to take into account community expectations and responsible industry development. There is inevitably tension between these competing interests.

The enforcement of alcohol-related offences committed by licensees has received greater attention since DOJ established the Compliance Unit in 2009. This unit, along with the liquor licence regulation and administration functions, moved from DOJ to the newly-created VCGLR in February 2012.

While Victoria Police and the Compliance Unit are targeting antisocial behaviour by individuals and minor breaches of the Act by licensees, there is no overarching whole‑of-government enforcement strategy to comprehensively address unlawful supply, particularly service to intoxicated patrons and minors, which is the cause of much of the alcohol-related harm.

A fundamental change in approach to strategy development, licensing and enforcement is required before any noticeable impact on reducing harm is likely. Unfortunately, steps taken to date in developing the new alcohol and drug strategy, which is currently still in draft, suggest that opportunities for meaningful change may again be missed.

Meanwhile, alcohol-related harm continues to rise.

Findings

Strategy development, implementation and evaluation

DOJ has devoted significant resources to minimising the harmful effects that can arise from alcohol consumption. However, the effectiveness of these efforts has been limited by poorly developed, implemented and evaluated strategies.

The whole-of-government strategy Restoring the Balance: Victoria’s Alcohol Action Plan 2008–13 (VAAP) aimed to reduce:

- risky drinking and its impact on families and young people

- the consequences of risky drinking on health, productivity and public safety

- the impact of alcohol-fuelled violence and antisocial behaviour on public safety.

There was no whole‑of‑government policy position on alcohol to guide how the competing interests of the health, business, tourism and community sectors should be prioritised and resolved in VAAP. Attempting to balance these interests resulted in a diluted and disjointed strategy.

DOJ advised that it does not dispute the research findings that the cost and availability of alcohol influence consumption and ultimately harm. Since the law does not allow the state to use pricing as a harm minimisation strategy, it is reasonable to expect DOJ to compensate for this by providing advice on ways to significantly enhance controls over supply instead. It has not done so.

The justice component of VAAP was a series of reactive, often small-scale and action-based initiatives that lacked substance and cohesion and were not strongly evidence-based. There was insufficient data available on consumption patterns and alcohol-related harm to comprehensively and objectively inform the development of the strategy. Although there were some exceptions—such as the increased level of compliance with licence conditions and the risk-based licence fee structure—these actions did not collectively or purposefully contribute towards achieving VAAP’s aims.

DOJ advised that heightened community and media concerns regarding alcohol‑related harm influenced decision-making in terms of both the content and timing of initiatives. A number of actions were authorised and undertaken outside the strategic framework and without a robust assessment of how they would contribute to minimising alcohol-related harm.

DOJ has spent approximately $67 million since 2007–08 on the development and implementation of alcohol policy, liquor licence regulation and compliance inspections. However, it has carried out only limited evaluation of what it has achieved from this significant investment.

Four years on, the issues of competing interests and data limitations have yet to be resolved. The opportunity to learn lessons from VAAP has been missed because no holistic performance evaluation has been carried out.

There is, therefore, a real risk that the new alcohol and drug strategy currently in development will make the same mistakes as VAAP.

Data collection and information sharing

Many of DOJ’s activities directly or indirectly target reducing excessive alcohol consumption as a means of reducing alcohol-related harm. However, DOJ cannot reliably measure its effectiveness in reducing overall consumption because alcohol sales data is not collected in Victoria.

Although agencies individually collect data on alcohol-related harm, there is no central database to collate, analyse and disseminate all of the data available. This data includes crime statistics from Victoria Police, the Compliance Unit and councils, ambulance attendances, emergency department presentations, hospitalisations, treatment episodes and deaths relating to alcohol.

This type of database would provide a comprehensive picture of alcohol consumption and harm in Victoria. It could be used to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of efforts to minimise alcohol-related harm by addressing the information gaps that currently exist for robust strategy development, focusing enforcement and compliance activities on high-risk areas, and encouraging greater inter-agency cooperation.

Liquor licensing regime

The liquor licensing regime is not effectively minimising alcohol-related harm due to a lack of transparency of decision-making, guidance on regulatory processes and engagement from councils. Administrative errors, poor records management and inconsistencies between liquor licence and planning permit conditions have further limited the effectiveness of the process.

Commercial interests have historically taken precedence over public health and community interests, thus compromising agencies’ ability to meet the Act’s harm minimisation objective. The planning permit and liquor licence application processes were enhanced following a series of joint reviews by DOJ and the Department of Planning and Community Development in 2009 and 2010. These reviews were comprehensive and evidence-based. However, the recommendations from these reviews were not accepted in full.

Although there has been a recent shift towards better consideration of public health and community interests, the existing regime is still weighted in favour of the liquor and hospitality industry. The number of objections to liquor licence applications by councils is exceptionally low.

Councils’ ability to influence the liquor and hospitality industry on behalf of the communities they represent is restricted by shortcomings in the planning permit and liquor licence application processes. The grounds for objecting to a liquor licence are narrow, and the evidentiary requirements and decision-making process for contested licence applications are not clear.

While VCGLR should provide clearer guidance on the liquor licensing process, councils should do more to work within the existing planning and liquor licensing arrangements to reduce their current sense of disempowerment and dissatisfaction. For example, councils could develop a local policy for licensed premises to guide decision-making on planning permits, or insert and enforce specific conditions on licensed premises’ planning permits.

DOJ implemented improvements in the mandatory industry training for licensees and staff following reviews in 2009 and 2010. There are, however, some inconsistencies in how the training is delivered. As VCGLR assumed responsibility for training in 2012, VCGLR could remedy this by more closely overseeing training providers. It could also further tailor the training to better meet attendees’ needs.

Training is important to assist licensees and their staff to understand their obligations. However, applying this training in a work environment can be challenging. Many licensees meet their legislative obligations. However, for those who are less diligent, enforcement—or the prospect of enforcement—and its associated financial penalties is likely to promote more appropriate industry practices.

Enforcement

Compliance inspections identify licensees’ compliance with the administrative requirements of their liquor licence, while Victoria Police is focusing on alcohol-related offences by individuals.

The compliance inspection program is having a noticeable and positive effect on licensees’ compliance with the administrative requirements of their liquor licence. Victoria Police has successfully carried out targeted and covert operations, and implemented other proactive initiatives, such as educational programs in local communities.

However, there is no whole-of-government alcohol enforcement strategy. While there have been localised examples of joint operations, inadequate strategic planning by and between enforcement agencies means there are gaps in the enforcement approach. Victoria Police and the Compliance Unit have not adequately targeted licensees who supply alcohol unlawfully.

Compliance Unit

Of the total inspections carried out by the regional compliance inspectors in 2010–11, only 20 per cent were conducted at the weekend, which is when most alcohol-related harm occurs. Inspectors’ work patterns should be amended as a matter of priority, as the current arrangements deliver poor value-for-money for taxpayers.

The Compliance Unit has adopted an educative approach to licensees to help them understand their obligations. However, for more serious or ongoing breaches, the Compliance Unit uses disciplinary actions, enforceable undertakings, penalty notices and written warnings.

Delays in processing these enforcement actions—which are not entirely within the Compliance Unit’s control—have allowed poorly-managed venues to continue to operate as sources of alcohol-related harm. Penalties for licensees who fail to comply with their obligations have recently been strengthened, with a demerit points system coming into effect in 2012. This initiative is expected to improve compliance rates, as consistent non-compliance will result in licences being automatically suspended.

Victoria Police

There is no formal policy on alcohol enforcement and harm minimisation, or a statewide operational framework to guide Victoria Police’s enforcement action against licensees. Responsibility for developing and implementing alcohol policing strategy is highly devolved, with local officers planning and carrying out their own enforcement activities. The current lack of centralised direction, coordination and training increases the risk of inconsistent practices and inefficiencies through duplication of effort.

The systems and processes for recording and analysing alcohol-related crime are weak. This reduces the availability and quality of intelligence data, which constrains Victoria Police’s ability to appropriately target enforcement action to the areas and premises where action is most urgently required.

Liquor legislation

Liquor legislation is not adequately supporting enforcement activities due to unclear legal definitions and inconsistencies.

Enforcement agencies are hindered in their efforts to take appropriate action against licensees that are unlawfully supplying alcohol by unclear legal definitions, which allow subjective interpretations of the Act. These licensees are avoiding penalties and are continuing to operate, tainting the whole licensed hospitality industry. This is a poor outcome for the community and a waste of public sector resources, particularly for the police and courts.

Inconsistencies exist within the Liquor Control Reform Act 1998 itself, and between the Act and other legislation and agency guidance. Under-age drinking is a case in point. Although health bodies recommend delaying the age at which alcohol is first consumed, minors are permitted to consume alcohol in certain supervised circumstances.

The penalty for a gambling provider that allows a minor to gamble is double the penalty for a licensee who illegally supplies a minor with alcohol. The penalty for a body corporate that sells tobacco to a minor is 10 times higher. Although the health impacts of smoking may be greater, the consumption of alcohol can result in adverse consequences—such as antisocial behaviour—that affect the wider community.

These inconsistencies undermine efforts to minimise harm. Since the functions of the gambling and liquor regulators have recently been integrated into one body, it is an opportune time to review and rationalise legislation and processes for consistency and appropriateness.

Recommendations

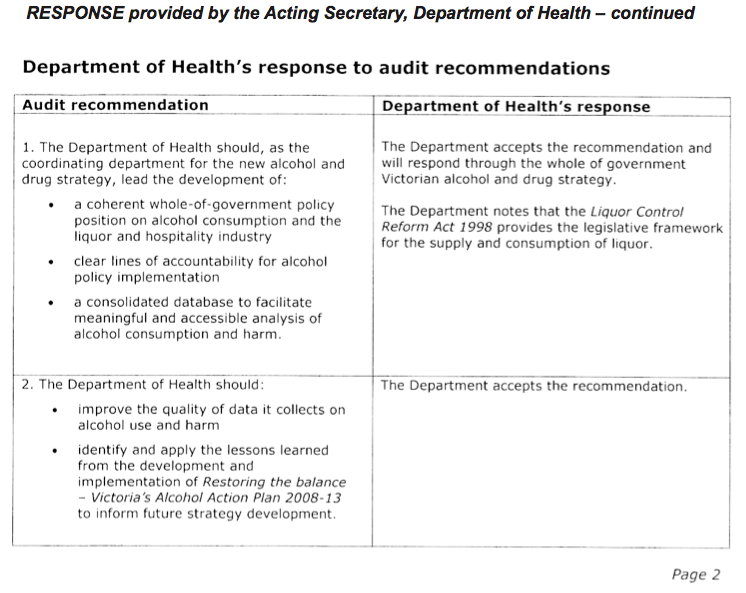

- The Department of Health should, as the coordinating

department for the new alcohol and drug strategy, lead the development of:

- a coherent whole-of-government policy position on alcohol consumption and the liquor and hospitality industry

- clear lines of accountability for alcohol policy implementation

- a consolidated database to facilitate meaningful and accessible analysis of alcohol consumption and harm.

-

The Department of Health should:

- identify and apply the lessons learned from the development and implementation of Restoring the Balance: Victoria’s Alcohol Action Plan 2008–13 to inform future strategy development

- improve the quality of data it collects on alcohol consumption and harm.

-

The Department of Justice should:

- pilot the collection and analysis of liquor sales data from wholesalers to retailers

- improve communication with stakeholders in the development and implementation of initiatives.

-

The Department of Justice should, together with the

Department of Planning and Community Development and in consultation with

local councils, overhaul the planning permit and liquor licence application

processes to:

- better address community and health concerns

- improve efficiency

- clarify roles and responsibilities

- incorporate an appropriate level of consultation and scrutiny.

-

The Department of Planning and Community Development should:

- create a model local planning policy for licensed premises

- require councils to adopt a local planning policy for licensed premises where there is a particular need or concern.

-

The Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation should:

- review its licensing administration practices

- improve its records management and data integrity

- exercise closer oversight over training providers to maintain standards and remove inconsistencies

- tailor the mandatory industry training to better meet attendees’ needs.

-

The Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation and Victoria Police should:

- develop a comprehensive and collaborative enforcement strategy to minimise harm more effectively and efficiently

- carry out more targeted and intelligence-led enforcement activities.

- The Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation should implement robust, efficient and, where appropriate, consistent practices across its compliance functions.

-

Victoria Police should:

- develop stronger central leadership for alcohol enforcement policy and activities

- improve the quality of the data it collects on alcohol‑related crime.

- The Department of Justice should review the Liquor Control Reform Act 1998 to facilitate more effective and efficient enforcement action.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Justice, Victoria Police, the Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation, the Department of Health, the Department of Planning and Community Development, the City of Casey Council, the City of Greater Geelong Council, the City of Melbourne Council and Swan Hill Rural City Council with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments however, are included in Appendix B.

1 Background

1.1 Alcohol consumption

Alcohol is a widely accepted part of Australian culture. It provides enjoyment to consumers and generates positive impacts for the state in the form of revenue and employment. In 2007–08, alcohol sales in the café, bar, catering service and restaurant industry contributed $3.4 billion to the Victorian economy, and employed 80 000 people. The food and wine tourism industry attracted 1.4 million visitors to Victoria in 2009.

However, the wide acceptance of alcohol can overshadow the fact that it is essentially a legal drug. The consumption of alcohol can impair judgement and coordination, trigger aggressive tendencies, cause nausea and may even result in death. The adverse consequences that arise from the misuse of alcohol may be both short-term and long-term and affect not only the drinker but also potentially their family, friends and the wider community.

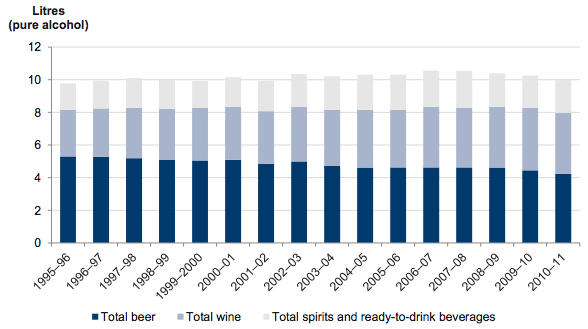

Australia is ranked 44th out of 188 countries surveyed by the World Health Organisation for alcohol consumption per capita. Figure 1A shows that Australians’ total alcohol consumption has remained relatively stable in recent times, but that consumers increasingly prefer to drink wine, spirits and ready-to-drink (RTD) beverages rather than beer.

Figure 1A

Alcohol consumption per capita in Australia

Note: Pure alcohol figures are based on the alcohol content of the beverage, rather than the total volume of liquid consumed.

Note: Per capita figures are calculated using population data for people aged 15 years and over.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on Australian Bureau of Statistics data.

In 2009, the National Health and Medical Research Council released the revised Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol. These guidelines are based on the concept of a ‘standard drink’, where one standard drink contains 10 grams of pure alcohol.

Examples of approximately one standard drink are:

- 375 ml or one ‘stubbie’ of mid-strength beer (3.5 per cent alcohol content)

- 100 ml or one small glass of wine (11.5 per cent alcohol content)

- 30 ml of spirits (40 per cent alcohol content).

The National Health and Medical Research Council’s guidelines are the same for both men and women. They recommend drinking no more than:

- two standard drinks on any day—to reduce the risk of suffering long-term alcohol‑related harm

- four standard drinks on a single occasion—to reduce the risk of suffering short‑term alcohol-related harm.

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s 2010 National Drug Strategy Household Survey, 20 per cent of Australians aged 14 and over consume more than two standard drinks per day on average, and 28 per cent drink more than four standard drinks on a single occasion at least once per month. The same survey indicates that 45 per cent of Victorians aged 14 years and older drink at least weekly.

1.2 Alcohol industry in Victoria

There are over 19 000 active liquor licences and BYO permits in Victoria. These are held by operators including pubs, bars, restaurants, clubs, bottle shops, wineries and event organisers. Approximately 78 per cent of the total volume of alcohol sold in Australia in 2009 was for off-premises consumption. Packaged liquor is primarily consumed in private homes.

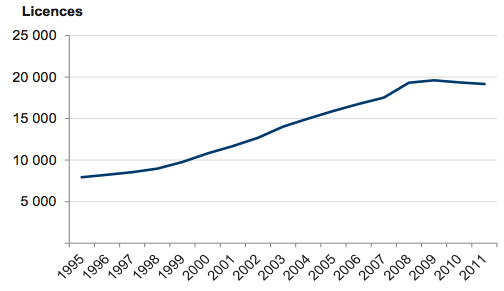

The number of licences does not reflect the number of actual licensed premises because a single venue may have multiple licences for different purposes. The number of licences has remained relatively constant since 2009 as new licence applications have been processed and existing premises have combined multiple licences into one.

Figure 1B shows how the number of active licences has changed since 1995.

Figure 1B

Active licences in Victoria as at 30 June 1995–2011

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

1.3 Addressing alcohol-related problems

The short- and long-term harm caused by alcohol can have wide-ranging impacts on the economy and society. According to a report commissioned by the Department of Justice (DOJ), the social cost of short- and long-term alcohol-related harm in Victoria in 2007–08 was $4.3 billion. However, the actual total is likely to be even higher, as some costs, such as those due to child abuse and neglect, are particularly difficult to quantify. Figure 1C shows the breakdown of the total measured cost to Victoria.

Figure 1C

Cost of alcohol-related harm to Victoria

Type of cost |

Cost ($ million) |

Per cent of total |

|---|---|---|

Direct costs |

1 987 |

46.3 |

Road accidents |

571 |

13.3 |

Healthcare |

530 |

12.3 |

Crime |

448 |

10.4 |

Resources used in abusive consumption |

438 |

10.2 |

Indirect costs |

1 144 |

26.6 |

Workforce labour costs |

1 139 |

19.3 |

Household labour costs |

414 |

7.0 |

Other costs including education and research |

15 |

0.4 |

Resources saved |

–425 |

N/A |

Intangible costs |

1 165 |

27.1 |

Loss of life |

1 073 |

25.0 |

Pain and suffering |

92 |

2.1 |

Total |

4 296 |

100 |

Note: Differences are due to rounding.

Note: Where available, the figures include the costs of alcohol and illicit drugs used together.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on Collins, DJ & Lapsley, HM, The costs of tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug abuse to Australian society in 2004/05, 2008, and Allen Consulting Group, Alcohol-related harm and the operation of licensed premises, 2009.

Contained within these figures is the cost to the public sector. Approximately $366 million, or 9 per cent of the total cost, was borne by the government, primarily through the provision of policing and health services.

Strategies, legislation and regulation have been put in place to minimise the potential adverse effects of alcohol misuse.

1.3.1 Strategies

In 2002, the Department of Human Services (DHS) launched the Victorian Alcohol Strategy: Stage One. The strategy was described as ‘the first stage in the government’s approach to alcohol misuse and harm’.

In 2005, DOJ began work on developing and implementing a range of localised initiatives in the entertainment precincts of the four inner-city councils: Melbourne, Port Phillip, Stonnington and Yarra.

In 2008, DHS released Restoring the Balance: Victoria’s Alcohol Action Plan 2008–13 (VAAP). Responsibility for implementing VAAP rested primarily with DHS, the Department of Health (DOH), DOJ and Victoria Police. The justice component of VAAP focused on enforcing controls over licensed premises and the sale and marketing of alcohol, and preventing and reducing the effects of alcohol misuse, such as alcohol‑fuelled violence.

DOJ and Victoria Police had 14 actions to deliver under VAAP, which largely focused on the licensed hospitality industry and alcohol-related harm in public places:

- enhance enforcement of the Liquor Control Reform Act 1998

- review liquor licensing fees

- review obligations of managers and employees of licensed premises

- consider introducing under-age operatives

- review compliance with the voluntary water guidelines to provide free or low-cost drinking water on licensed premises

- develop an assault reduction strategy

- introduce late-hour entry restrictions

- freeze the issuing of late night liquor licences

- implement new security camera regulations

- review patron numbers in high-risk venues

- amend the Victoria Planning Provisions

- consider a new rehabilitation system for high-risk drink-driving offenders

- extend the zero blood alcohol concentration limit for young drivers

- conduct the Safe Streets public safety research and pilot evaluation.

While implementing its VAAP actions, DOJ worked concurrently on additional measures to combat alcohol-related harm. These included issuing guidelines on appropriate alcohol promotions and venue design to improve safety.

Following the 2010 election, VAAP was replaced by the initiatives contained in the Plan for Liquor Licensing.

In 2011, consultation on the new whole-of-government alcohol and drug strategy began. The strategy is due to be launched in 2012.

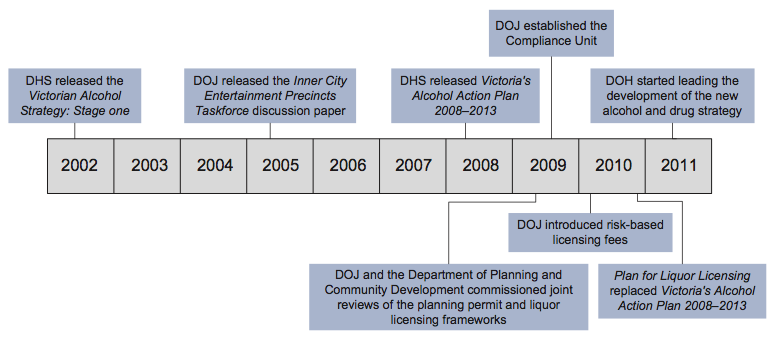

Figure 1D

Time line of whole-of-government alcohol strategies and initiatives

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

1.3.2 Legislation and regulation

The Liquor Control Reform Act 1998 regulates the supply and consumption of liquor. The Act aims to minimise harm arising from the misuse and abuse of alcohol by:

- providing adequate controls over the supply and consumption of liquor

- ensuring that the supply of liquor contributes to, and does not detract from, the amenity of community life

- restricting the supply of certain alcoholic products

- encouraging a culture of responsible consumption of alcohol and reducing risky drinking of alcohol and its impact on the community.

The Act also aims to:

- facilitate the development of a diversity of licensed facilities reflecting community expectations

- contribute to the responsible development of the liquor, licensed hospitality and live music industries.

The supply of alcohol is primarily regulated through liquor licences. As at May 2012, the Act identifies 11 categories of liquor licences and permits:

- general licence

- on-premises licence

- restaurant and café licence

- club licence

- packaged liquor licence

- late night licence

- pre-retail licence

- wine and beer producer’s licence

- limited licence

- major event licence

- BYO permit.

The applicant’s business determines the type of licence required. Licences associated with greater risk of alcohol-related harm have higher fees and more stringent conditions.

Licensees’ obligations under the Act include:

- supplying liquor in accordance with their licence conditions

- completing Responsible Service of Alcohol (RSA) training

- publicly displaying their licence and other prescribed information

- not allowing their venue to adversely affect the amenity of the surrounding area

- fulfilling administration and record keeping requirements

- supplying free drinking water

- allowing the premises to be inspected when required.

Licensees who do not meet their obligations may have their licence cancelled or suspended.

1.4 Stakeholders

Many government agencies and other groups contribute towards meeting the objectives of the Liquor Control Reform Act 1998 and managing alcohol-related harm.

Department of Justice Alcohol Policy Unit

The Alcohol Policy Unit within DOJ is responsible for developing alcohol policy and guiding the implementation of justice initiatives. Until February 2012 the Alcohol Policy Unit was part of Responsible Alcohol Victoria. Responsible Alcohol Victoria was also responsible for liquor legislation and regulation, and monitoring licensees’ compliance.

Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation

The Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation (VCGLR) determines licence applications and enforces liquor and gambling laws. Created in February 2012, this new body combines the business services, training and compliance areas of Responsible Alcohol Victoria with the functions of the Director of Liquor Licensing and the Victorian Commission for Gambling Regulation.

The liquor enforcement function is undertaken by specialist compliance inspectors. The Compliance Unit’s main aim is to ‘ensure that alcohol is promoted and sold in a way that encourages responsible and appropriate drinking’. Inspectors work to achieve this by educating licensees about their obligations, monitoring licensees’ compliance with liquor legislation and licence conditions and making recommendations about:

- varying licence conditions

- taking disciplinary action

- prosecuting licensees and their staff.

The Compliance Unit was created to supplement Victoria Police’s operations in enforcing liquor laws.

Victoria Police

Victoria Police focuses on serious breaches of liquor legislation and public order offences relating to alcohol consumption. This is achieved by carrying out targeted and covert operations in addition to day-to-day policing. Victoria Police’s other responsibilities relating to liquor include commenting on the suitability of liquor licence applicants and participating in liquor licensing forums.

Local councils

Local councils grant or reject planning permits. They also have the power and opportunity to provide input into licensing applications, participate in liquor licensing forums, and implement local strategies to minimise alcohol-related harm, for example by introducing and enforcing by-laws. Some councils have local alcohol action plans to guide policy development and set targets for reducing alcohol-related harm in their area.

Other stakeholders

Many other government and non-government bodies play a role in the liquor and licensed hospitality industry and the prevention of alcohol-related harm. These bodies have a range of interests and backgrounds, including health, transport, tourism, small business, alcohol dependency services, industry peak bodies and research organisations.

The number and type of stakeholders mean that consultation on alcohol strategy development and implementation is necessarily complex and wide ranging.

1.5 Audit objective and scope

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of DOJ, Victoria Police and VCGLR’s initiatives and actions in:

- enforcing controls on the sale and marketing of alcohol

- preventing and reducing the impact of short-term alcohol-related harm on the community.

Four councils were consulted during the audit: City of Casey, City of Greater Geelong, City of Melbourne and Swan Hill Rural City Council.

1.6 Structure of the report

The rest of this report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 provides an overview of alcohol-related harm, and examines strategy development, implementation and evaluation

- Part 3 analyses the liquor licensing regime

- Part 4 assesses the enforcement activities undertaken by Victoria Police and VCGLR

- Appendix A presents data on alcohol consumption and harm.

1.7 Audit method and cost

The audit was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. The total cost of the audit was $410 000.

2 Strategy development, implementation and evaluation

At a glance

Background

The Victorian Alcohol Strategy: Stage One was launched in 2002. It was followed six years later by Restoring the Balance: Victoria's Alcohol Action Plan 2008–13 (VAAP). In 2011, work began on a new alcohol and drug strategy.

Conclusion

Alcohol-related harm has increased over the past decade. The Department of Justice's (DOJ) poorly developed, implemented and evaluated initiatives have not been effective in reversing the trend of increasing harm.

Findings

- DOJ's initiatives to prevent and reduce alcohol-related harm were fragmented, superficial and reactive instead of targeted, evidence-based, complementary and well coordinated.

- Stakeholder consultation was inadequate and numerous ad hoc initiatives were implemented outside the strategy. This resulted in unintended financial consequences for small businesses.

- Due to the lack of comprehensive, accurate and shared data, and the inadequate evaluation of VAAP, it is likely that the new alcohol and drug strategy will be similarly limited in achieving the intended outcomes.

Recommendations

The Department of Health should lead the development of:

- a coherent whole‑of‑government policy position on alcohol consumption and the liquor and hospitality industry

- a consolidated database to facilitate meaningful and accessible analysis of alcohol consumption and harm.

DOJ should pilot the collection and analysis of liquor sales data from wholesalers to retailers.

2.1 Introduction

The Department of Health (DOH) coordinates alcohol policy development across government. The Department of Justice (DOJ) leads the Justice portfolio's alcohol activities within the overarching government framework.

The whole-of-government strategy Restoring the Balance: Victoria's Alcohol Action Plan 2008–13 (VAAP) aimed to reduce:

- risky drinking and its impact on families and young people

- the consequences of risky drinking on health, productivity and public safety

- the impact of alcohol-fuelled violence and antisocial behaviour on public safety.

In 2010, work began on implementing the initiatives in the Plan for Liquor Licensing.

In 2011, DOH started leading the development of a new alcohol and drug strategy. The new strategy had not been finalised by the tabling date of this audit report.

This Part provides an overview of alcohol-related harm data, and assesses the development, implementation and evaluation of alcohol initiatives, with a particular focus on DOJ's activities.

2.2 Conclusion

The increase in reported short-term alcohol-related harm over the past 10 years indicates that strategies to mitigate alcohol-related harm have not been successful. More people require medical attention for intoxication, and the number of assaults and injuries has increased. The extent of the problems caused by alcohol is, however, understated because of shortcomings in data collection, analysis and dissemination.

Multiple agencies are involved in alcohol policy, many with competing interests. There is no whole-of-government policy position on alcohol and the liquor and hospitality industry to resolve these competing interests. The consequence of these unresolved issues in 2008 was a diluted strategy with limited effectiveness.

DOJ has made efforts to minimise the harmful effects that can arise from alcohol consumption. However, the effectiveness of its efforts has been reduced by poorly chosen and implemented strategies. The DOJ component of VAAP was a fragmented series of reactive, often small-scale initiatives that were action-based, rather than outcome‑based. They did not make a purposeful, direct and collective contribution towards minimising harm, and were not sufficiently underpinned by evidence.

VAAP was launched six years after it was first proposed. Despite this length of time, poor planning meant DOJ's initiatives had unforeseen and unintended consequences—stakeholder consultation was inadequate and numerous ad hoc initiatives were implemented outside the strategy.

DOJ's ability to develop evidence-based strategies has been further limited by the inadequate evaluation of previous initiatives. DOJ has spent approximately $67 million since 2007–08 on developing and implementing alcohol policy, liquor licence regulation and compliance inspections, yet its evaluation of what it has achieved from this significant investment has been limited.

The lack of a centralised database of harm data also impedes evidence-based strategy development. The relationship between alcohol and harm is obscured by incomplete and inconsistent recording of the presence of alcohol in police and medical data. These gaps and inaccuracies diminish the quality of any analysis on alcohol's contribution to harm. In this regard, Victoria has fallen behind other jurisdictions.

The lack of comprehensive, accurate and shared data and inadequate evaluation of VAAP means it is likely that the new strategy will be similarly limited in achieving its intended outcomes.

2.3 Alcohol consumption and harm

Alcohol-related harm has increased significantly over the past 10 years. Although there are issues regarding the comprehensiveness and accuracy of data, there are strong patterns of increased harm across almost all indicators from a variety of sources. This provides a compelling case that harm is indeed widespread and increasing. These types of indicators are included in the draft alcohol and drug strategy as the best data currently available.

The increase indicates that harm reduction actions have had limited effectiveness.

2.3.1 Alcohol consumption and intoxication

Surveys have consistently revealed that over 80 per cent of the adult population drink. Approximately 75 per cent of Australians believe more needs to be done to reduce alcohol-related harm, but only 6 per cent are concerned about their own drinking.

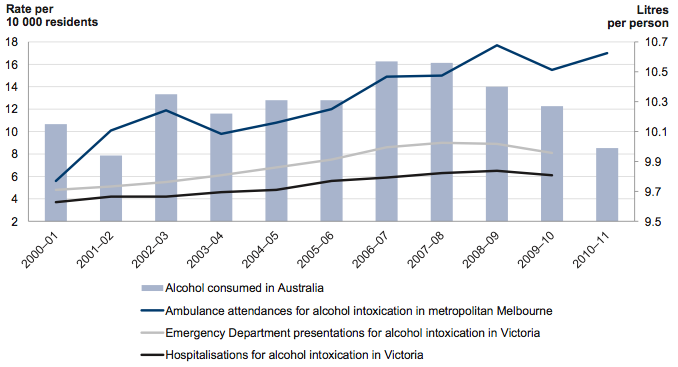

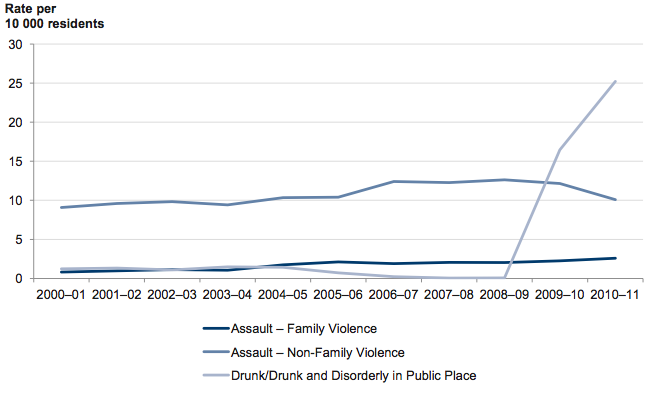

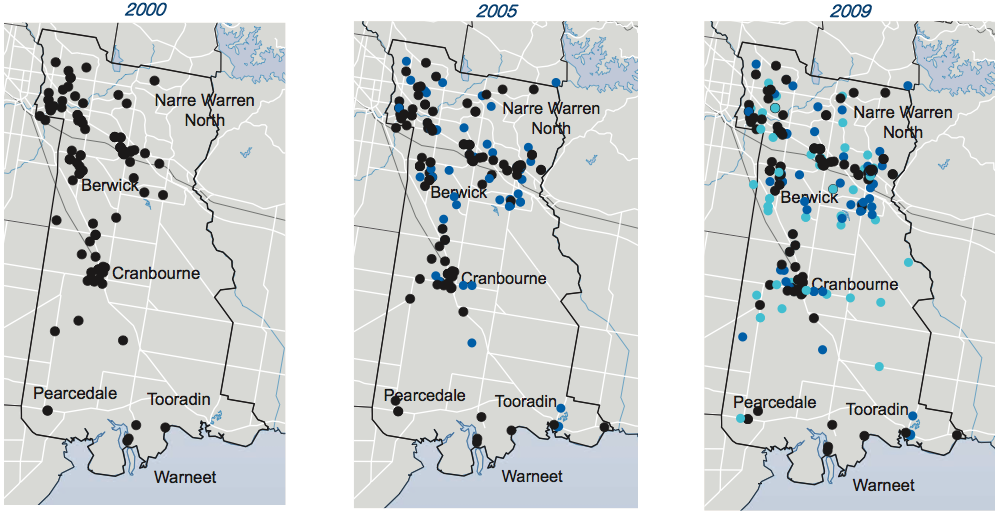

Figure 2A shows there are some similarities in medical data on alcohol intoxication and patterns of per capita consumption. This figure is based on population rates, and therefore adjusts for the impact that the rising number of residents has on the number of incidents.

Figure 2A

Ambulance, emergency department and hospitalisation rates for intoxication versus alcohol consumed

Note: Data for alcohol consumption and ambulance attendances is not available for Victoria.

Note: 2010–11 data was not available for Emergency Department presentations or hospitalisations at the tabling date of this report.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Turning Point and Australian Bureau of Statistics data.

While the above figure is based on rates per 10 000 residents, the total number of Victorians recorded as needing medical assistance as a result of alcohol intoxication has increased dramatically. According to Turning Point data:

- there were 6 946 ambulance attendances for alcohol intoxication in metropolitan Melbourne in 2010–11, which is more than 3.5 times higher than in 2000–01

- there were 4 425 emergency department presentations for intoxication in Victoria in 2009–10, which is an increase of 93 per cent since 2000–01

- there were 3 343 people hospitalised for alcohol intoxication in Victoria in 2009–10, which is an increase of 87 per cent since 2000–01.

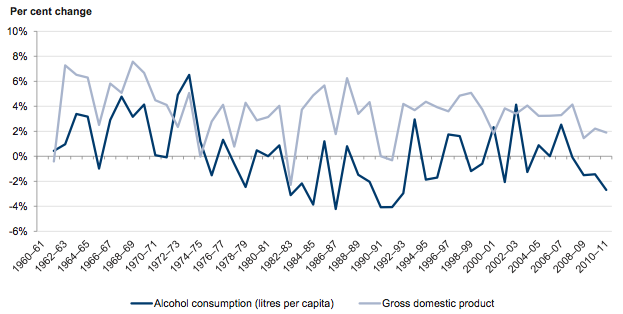

Besides government interventions, other factors, such as broader economic conditions, have a strong influence on alcohol consumption rates. For example, studies in both Europe and America have shown that the consumption of alcohol tends to increase during times of economic prosperity, and decrease during economic downturns.

2.3.2 Alcohol-related injuries and assaults

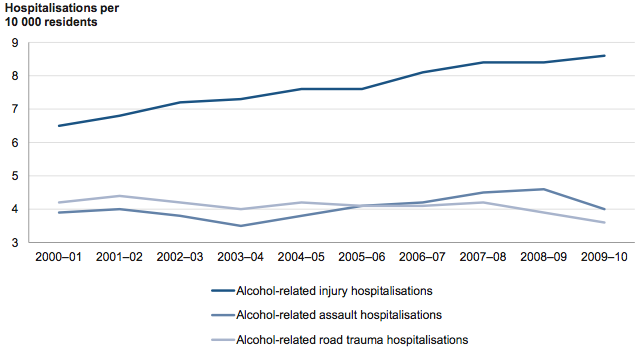

As Figure 2B shows, the recorded rates of hospital admissions for alcohol-related injuries have increased by 32 per cent over the past 10 years.

However, rates of hospitalisation for alcohol-related road trauma have remained relatively stable during the period. The comparative stability of these rates may be due to a range of other factors, including improved vehicle safety, drink-driving interventions and other measures, such as more road safety cameras.

Figure 2B

Alcohol-related hospitalisations in Victoria

Note: Alcohol-related hospitalisations are estimated using a formula based on analysis of past cases to calculate the likelihood of alcohol causing the patient's medical condition.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Turning Point data.

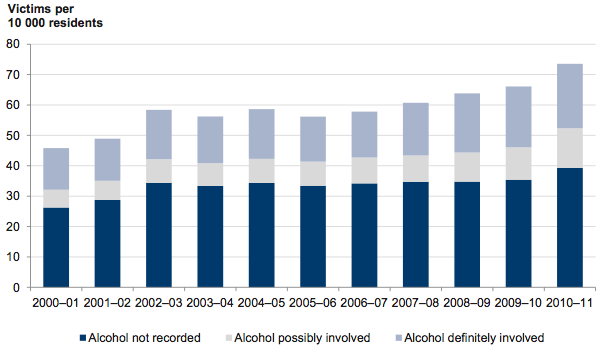

Victoria Police data indicates that the number of victims reporting alcohol-related family violence has more than doubled since 2000–01. This has been an area of focus for Victoria Police in recent years, and increased enforcement effort typically results in increased reporting. Neither DOJ nor Victoria Police can determine how much of the increase is due to a change in the approach to policing family violence and how much is due to the number of actual offences increasing. Figure 2C shows the number of victims per 10 000 residents reporting family violence.

Figure 2C

Alcohol-related family violence in Victoria

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Victoria Police data.

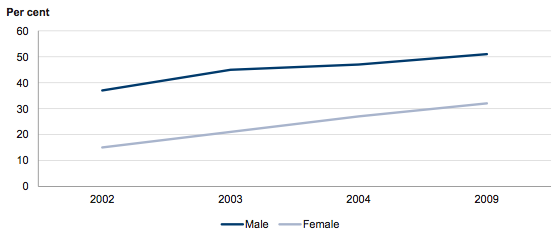

Rates of alcohol-related harm are increasing faster for women and young people than for other demographic groups. These trends are apparent across both health and police data.

Further analysis of consumption and harm data is in Appendix A.

2.4 Strategy development

Alcohol policy is highly contentious. Community attitudes to alcohol are complex and often ambiguous. Although alcohol is deeply embedded in the Australian culture, there is also widespread concern about the severe consequences that can result from excessive consumption.

Effective strategy development depends on a clear policy position, timely responses and a robust evidence base. Specific, targeted strategies may be required for particular groups in order to be effective.

2.4.1 Strategy coherence

A whole-of-government position on alcohol would set a clear direction for the new alcohol and drug strategy, and minimise the likelihood of repeating the same issues experienced with VAAP. No statement of policy had been endorsed by the tabling date of this audit report.

Stakeholders in alcohol policy are many and varied. They therefore have a range of differing perspectives on alcohol consumption and the industry:

- health—health services providers, such as hospitals and drug treatment centres, advocate tighter controls over the sale of alcohol in order to reduce the medical burden of injuries and disease that can result from alcohol consumption

- business—hospitality and tourism organisations aim to promote a thriving 'night‑time economy', which generally involves alcohol consumption

- community—councils and local interest groups seek to encourage local investment while preventing and reducing alcohol-related public disorder and health issues in their municipality

- justice—DOJ, the Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation (VCGLR) and Victoria Police aim to minimise harm by encouraging licensees and the public to serve and consume alcohol responsibly, and by carrying out enforcement action for more serious or ongoing offences.

In the absence of a statement of policy to guide how these competing interests should be resolved, the justice component of VAAP was little more than a series of superficial, standalone actions whose connection with the strategy's objectives was not explicit. For instance, although one of DOJ's stated intentions was to have 'properly enforced controls on the sale and marketing of alcohol', none of DOJ's actions related directly to product marketing.

This disconnect between the desired outcomes of the strategy and its actions has resulted in other ad hoc actions being developed separately in an attempt to achieve these outcomes. For instance, significant progress was made outside the VAAP framework in discouraging marketing and promotions that encouraged risky drinking. This might have been avoided had the strategy been based on more robust evidence and a stronger, more logical structure.

There has been ample time to prevent these issues arising. The whole-of-government Victorian Alcohol Strategy: Stage One was launched in 2002 as 'the first stage in the government's approach to alcohol misuse and harm'. The launch of VAAP was deferred until 2008, to allow time for further reviews and Parliamentary inquiries to be carried out.

Over the six-year period that VAAP was being developed, the number of licences in Victoria increased by 52 per cent. Hospitalisations for alcohol‑related assault increased by 22 per cent. The rate of ambulance attendances for intoxication and reported alcohol-related family violence also increased during this period.

At the tabling date of this report, the new alcohol and drug strategy had been under development for over a year. The strategy was initially due for release before the end of 2011, but is now expected to be launched later in 2012.

2.4.2 Evidence base

The availability and reliability of data underpins evidence-based strategy development and evaluation. Insufficient action has been taken to address the omissions and inaccuracies in the data and incorporate better practice.

Better practice

Harm minimisation has been the primary objective of the Liquor Control Reform Act 1998 since 2009. However, DOJ's strategies have not reflected better practice harm minimisation methods. Research has repeatedly shown that increasing the price of alcohol reduces demand and restricting its availability reduces supply. These measures have the effect of decreasing the level of overall consumption, which, in turn, reduces alcohol-related harm. DOJ advised that it does not dispute these research findings.

However, given a large proportion of the population drinks alcohol, increasing its price and reducing its availability by limiting the number of outlets and trading hours can be unpopular with the liquor and licensed hospitality industries, tourist organisations and the affected sections of the community.

Victoria cannot directly control the price of alcohol, as liquor licence fees based on sales volume are deemed an excise, which is a federal government power. Since the state cannot use pricing as a harm minimisation strategy, it is reasonable to expect DOJ to compensate for this by providing advice on ways to significantly enhance controls over supply instead. It has not done so.

Only one of the 14 justice actions in VAAP creates specific additional controls over availability and therefore supply—the freeze on issuing new late-night liquor licences. This measure was limited in scope, as it was only applicable to new licence applications in four local government areas.

VAAP was a missed opportunity to implement a range of actions that were proven to be effective at preventing and reducing alcohol-related harm by controlling supply.

Data on alcohol use

Many of DOJ's activities directly or indirectly target reducing consumption rates, yet it does not collect alcohol sales data. This data would allow DOJ to reliably measure the impact of its activities on overall consumption rates and comprehensively analyse the relationship between consumption patterns and alcohol-related harm.

DOJ stopped collecting sales data ostensibly because of a 1997 ruling by the High Court of Australia that liquor licensing fees levied by state governments based on sales data were duties of excise, and therefore not valid under the Australian Constitution. However, Western Australia, Queensland and the Northern Territory, with the same limitation of powers, continue to collect and analyse sales data.

The Drug and Crime Prevention Committee of Parliament, the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC), Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) DOH and DOJ have at various times all expressed their support for the collection of sales data. In particular, DTF emphasised that the current lack of data was inhibiting agencies’ ability to undertake Business Impact Assessments and Regulatory Impact Statements.

DOH commissioned a review in 2010 to assess the options and feasibility of collecting sales data. The review concluded that data on sales from wholesalers to retailers would provide the most reasonable balance between cost and accuracy, rather than collecting either a sample of, or full retail sales data. The review estimated that the cost to government over 10 years of collecting sales data from wholesalers would be $153 714, excluding IT system set-up and maintenance, communications, enforcement and data analysis. The cost to industry was estimated at $9.9 million, or $506 per licensee, over 10 years.

The collection of wholesale data was not pursued on the basis of these costs and the regulatory burden this was perceived to impose on industry. However, these costs are trivial compared with the estimated $4.3 billion that alcohol-related harm costs Victoria each year.

Other options that would improve data on the amount of liquor sold by licensees include requiring them to provide details of their turnover or the size of their premises as part of the annual licence renewal process. Changes to legislation may be required to enable VCGLR to obtain this information.

Data on alcohol-related harm

The lack of a centralised database of harm data limits:

- DOJ's capacity to develop evidence-based strategies

- the quality of decisions made on liquor licence applications

- the ability of Victoria Police and VCGLR to carry out intelligence-led enforcement.

The relationship between alcohol and harm is further obscured by incomplete and inconsistent recording of the presence of alcohol in police and medical data. Health data is slightly more robust than police data, as it is scrutinised more closely by research bodies.

Nonetheless, these gaps and inaccuracies diminish the quality of the analysis of alcohol's contribution to harm. Victoria has fallen behind other jurisdictions, where offenders and patients are asked about their alcohol consumption in a more structured and methodical manner.

Agencies have their own intelligence gathering procedures and methods, and develop enforcement strategies accordingly. Communication and information sharing between enforcement agencies, particularly in outer Melbourne and regional and rural Victoria, is largely ad hoc and on a 'need-to-know' basis. There is therefore duplication of effort without robust information sharing systems and strategies.

Multiple agencies including Victoria Police, VCGLR and local councils are involved in monitoring and responding to issues with licensed venues and to alcohol-related harm. Victoria Police and VCGLR separately record data on offences and infringements, VCGLR records breaches of liquor licence conditions and councils record breaches of the planning permit. Complaints from the public may be received by the police, VCGLR or councils.

This is a missed opportunity to build a whole-of-government 'early warning system' that identifies potential alcohol-related harm and problem venues before matters escalate. A central intelligence database to collate, analyse and share data from both crime and health sources would assist a coordinated effort by agencies to develop intelligence‑led strategies to deal with identified problems. Protocols on the sharing of information would appropriately reflect the sensitivity of the information.

Enforcement is covered in more detail in Part 4.

2.4.3 Strategy for vulnerable groups

Alcohol-related harm is increasing faster for young people than other age groups. Agencies' attempts to balance the health risks of alcohol consumption with public opinion and freedom have created inconsistencies between policy and within the legislation itself with regard to young people's consumption of alcohol. This sends mixed messages to the community and reduces the effectiveness of efforts to minimise harm.

Alcohol abuse in young people is linked to a range of harms including mental illness, sexual risk-taking and injuries. Early onset of alcohol abuse increases the risk of developing alcohol or other drug dependencies in later life. Because of the health risks associated with under-age alcohol consumption, health agencies recommend delaying the age at which alcohol is first consumed.

However, despite the health risks, the law permits under-18s to consume alcohol in certain supervised circumstances. According to a 2008 survey of Victorian secondary school students, by the age of 16:

- 92 per cent of respondents had consumed alcohol in their lifetime

- 40 per cent had consumed alcohol within the past week.

The Packaged Liquor Code of Conduct on VCGLR’s website does not, however, allow a packaged liquor outlet employee to sell alcohol if it appears that an adult is purchasing liquor for a minor, even if the adult in question is legally able to supply alcohol to that minor because they are either the child's parent or have the appropriate parental consent.

Under-age drinking has appeared in the Victorian Alcohol Strategy: Stage One and VAAP and the draft new alcohol and drug strategy. This repetition demonstrates agencies' lack of progress in addressing this problem area over the past 10 years. Statistics show that:

- there has been a 62 per cent increase between 2002 and 2009 in the number of 16–24 year olds who reported consuming 20 standard drinks or more in one day on at least one occasion within the past year

- the number of young people attending emergency departments for intoxication nearly tripled between 2000–01 and 2009–10.

2.5 Strategy implementation

Strategies that are poorly developed and/or implemented may have unintended consequences, such as heavy and often unnecessary financial costs being imposed on businesses and agencies.

2.5.1 Unintended consequences

DOJ’s alcohol actions were adversely affected not only by shortcomings in strategy development, but also in the implementation phase.

Figure 2D describes the unintended consequences from the late-night entry restrictions—‘the lockout’. The lockout was introduced to minimise the number of people moving between late-night venues in an attempt to reduce violence and antisocial behaviour.

Figure 2D

Case study—the lockout

In April 2008—two months before the lockout was launched—DPC noted: ‘There has been no industry consultation on the lockout proposal. There are a number of risks associated with this proposal, including unintended impacts, impacts on business and tourism and increased patronage for gaming venues’.

In May 2008 the Director of Liquor Licensing announced a temporary lockout covering the Melbourne, Port Phillip, Stonnington and Yarra local government areas.

In June 2008 the lockout began. The lockout lasted for three months, during which time licensees were banned from allowing patrons to enter or re‑enter their premises after 2 am. The lockout was not extended after the initial period ended in September 2008.

The lack of buy-in from the late-night licensed hospitality industry and their patrons fundamentally compromised the lockout. A total of 120, or approximately 25 per cent of affected venues, successfully applied for an exemption from the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT). There were public protests against the lockout.

According to focus groups conducted by the consultant engaged by DOJ to evaluate the lockout, smaller venues were most adversely affected by the entry restrictions, as patrons left them earlier than usual to get into late night venues prior to the 2 am lockout. This adverse unintended impact was not highlighted as a potential risk prior to implementation.

As a consequence of the large number of exemptions:

- enforcing the lockout was difficult

- patrons who were refused entry to one venue simply went to another that was exempt from the lockout

- the reduction in public order and drunkenness was much less than in the lockout implemented in the Gold Coast.

Further, although the number of reported assaults decreased between 8 pm and 12 am, they increased between 12 am and 4 am. The report suggests this was due in part to a lack of available late night transport options to move people away from Melbourne’s Central Business District.

Other, more successful, lockouts have been combined with actions such as graduated closing times and improved public transport. The temporary lockout may have been more successful if there had been better, more collaborative planning and more comprehensive consultation with stakeholders and the VAAP advisory group.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

2.5.2 Stakeholder engagement

DPC and DTF repeatedly raised concerns about the lack of effective consultation with stakeholders, following criticisms from the liquor and licensed hospitality industry on the poor quality of consultation.

DOJ advised that the short time lines set between announcing and delivering VAAP, and subsequent ad hoc initiatives, required DOJ to focus on implementing actions, rather than gathering evidence, consulting with stakeholders, and evaluating performance. A VAAP stakeholder engagement strategy was only endorsed in October 2008, five months after VAAP was launched.

2.5.3 Ad hoc actions

Over 50 actions have been undertaken by DOJ concurrently with, but outside, a strategic framework since 2008.

The measures introduced have included alcohol and violence media campaigns, design guidelines for licensed premises and amendments to legislation on disparate and topical matters such as party buses and ANZAC Day trading hours. There have been individual successes, such as the risk-based fee structure, which achieved a reduction in harm by encouraging venues to reduce patron numbers and trading hours.

However, the actions were fragmented in terms of both their design and implementation. This lack of cohesion limited the overall effectiveness and efficiency of DOJ's efforts.

It is to be expected that unforeseen issues will arise and require a rapid response. However, because the initiatives implemented were not part of a strategy, they were not subjected to a robust assessment or cost/benefit analysis to determine whether they were not only feasible but also the most effective and efficient use of resources.

As a result, actions were publicly announced but subsequently abandoned or postponed. For example, differentiated fees for different types of packaged liquor outlets were not implemented as they equate to an excise and are therefore unconstitutional. Another example was the review of restrictions on point-of-sale materials, which is described in Figure 2E.

Figure 2E

Liquor Control Advisory Council review of point-of-sale materials

The Liquor Control Advisory Council was established to advise the Minister for Consumer Affairs on problems of alcohol abuse and on any other matters referred to it by the minister. The council's members are drawn from the liquor industry and health service providers.

One of the matters the council was asked to advise on was the impact of point-of-sale promotions on alcohol consumption.

In an out-of-session meeting in September 2010, the council noted that ‘the gap in conclusive [point-of-sale] evidence suggests that no decisive action can be taken at this stage’ and recommended that further research be carried out.

Of the nine people who attended this meeting, four worked in the liquor industry. For these members, the point-of-sale assignment was a clear conflict of interest, as they were being asked to make recommendations on a matter that had the potential to reduce sales and therefore detrimentally affect their business.

This unsatisfactory stalemate might have been avoided had sales data been collected in Victoria. This information could have been used to map the correlation between promotions and sale patterns, rather than postponing a decision for two years while further research is conducted.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

2.6 Performance evaluation

The performance evaluation framework for VAAP was not robust and there was no holistic evaluation of the actions' impact. This is despite the statement in VAAP that 'the government will monitor progress against these outcome measures of the five-year period of the plan to 2013'.

The framework was ambiguous and not comprehensive, which meant that data and data sources could be used selectively for the evaluation:

- Only two of VAAP's three aims were included—'reduce the impact of alcohol‑fuelled violence and antisocial behaviour on public safety' was omitted, despite this being a key community concern.

- It was unclear how the outcomes would be measured, as the list of data sources was not comprehensive and it was not obvious which specific actions the data sources would be used to assess.

- Although VAAP was launched in May 2008, DOH did not commission work to define a more detailed set of measurement bases and data sources until March 2009.

- Performance targets were not quantified and there was no baseline data against which improvements would be measured in VAAP.

Inappropriately assessing options and evaluating performance can lead to decisions that are not soundly based. Not disclosing targets and detailed measurement bases allows improvements to be claimed even when they are marginal and below expectations.

DOJ commissioned reviews of some of its initiatives, including the lockout and the newly created Compliance Unit, which is discussed in more detail in Part 4. It also performed an internal review of the changes to the liquor licence fees. However:

- the usefulness of the department's reviews was limited due to factors including a lack of complete and accurate baseline data

- DOJ did not measure the effectiveness of other initiatives. For instance, the 12‑month ban on issuing new late-night liquor licences in the local government areas of Melbourne, Stonnington, Yarra and Port Phillip—'the freeze'—was not evaluated before it was extended.

DOJ believes that it would have acted inappropriately if it had allocated resources to carry out an evaluation after VAAP was replaced in November 2010.

The inadequate evaluation of VAAP means there is a risk that the new alcohol and drug strategy that is currently being developed will be similarly limited in achieving the intended outcomes.

The shortcomings in DOJ's strategy development, implementation and evaluation were compounded by deficiencies in liquor legislation and regulation. These issues are discussed in Part 3.

Recommendations

-

The Department of Health should, as the coordinating department

for the new alcohol and drug strategy, lead the development of:

- a coherent whole‑of‑government policy position on alcohol consumption and the liquor and hospitality industry

- clear lines of accountability for alcohol policy implementation

- a consolidated database to facilitate meaningful and accessible analysis of alcohol consumption and harm.

-

The Department of Health should:

- identify and apply the lessons learned from the development and implementation of Restoring the Balance: Victoria's Alcohol Action Plan 2008–13 to inform future strategy development

- improve the quality of data it collects on alcohol consumption and harm.

-

The Department of Justice should:

- pilot the collection and analysis of liquor sales data from wholesalers to retailers

- improve communication with stakeholders in the development and implementation of initiatives.

3 Liquor licensing regime

At a glance

Background

There are particular planning requirements for land used to sell or store liquor. Packaged liquor outlets, hotels, clubs and restaurants selling liquor are required to have both a planning permit from the local council and a liquor licence.

Conclusion

Weaknesses and inconsistencies in the legislation and licensing processes have reduced agencies’ ability to effectively minimise alcohol-related harm.

Findings

- Poor administration has resulted in licensing decisions that are not in line with the harm minimisation objective of the Liquor Control Reform Act 1998 and that do not reflect community interests.

- Inconsistencies, a lack of clarity and excessive restrictions in the legislation reduce the effectiveness of harm minimisation strategies.

- Liquor licensing processes are complex and opaque.

Recommendations

The Department of Justice should, together with the Department of Planning and Community Development, overhaul the planning permit and liquor licence application processes to better address community and health concerns.

The Department of Planning and Community Development should:

- create a model local planning policy for licensed premises

- require councils to adopt a local planning policy for licensed premises where there is a particular need or concern.

The Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation should:

- review its licensing administration practices

- exercise closer oversight over training providers.

3.1 Introduction

The harm minimisation objective of the Liquor Control Reform Act 1998 is intended to be met by measures that include ‘providing adequate controls over the supply and consumption of liquor’. The planning permit and liquor licence application processes are important mechanisms to control the licensed environment.

The Department of Planning and Community Development (DPCD) administers the planning system, which provides the framework for regulating and managing how land is developed and used. Each of the 79 local government areas has a planning scheme, which combines both statewide and local policies and provisions. Councils use the planning scheme to decide whether to grant or refuse planning permits. Planning permits are required for most types of licensed premises.

Until February 2012, the Director of Liquor Licensing granted or refused liquor licences, based on the suitability of the applicant and the potential impact of the licensed premises on the amenity of the surrounding area. This function transferred to the Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation (VCGLR) in February 2012.

Liquor licences are a mechanism used to regulate:

- who supplies liquor

- to whom it is supplied

- when it is supplied/consumed

- where it is supplied/consumed

- how it is supplied.

Part of VCGLR’s stated role is to inform and educate industry and the general public about regulatory practices and requirements. A licence application may be refused if the applicant cannot demonstrate sufficient understanding of their obligations under the Act. Mandatory industry training is provided to help licensees and their staff gain this knowledge.

This Part assesses the extent to which agencies are meeting the harm minimisation objective of the Act, the effectiveness and efficiency of the liquor licensing application process, including its interface with planning, and the appropriateness of the industry training overseen by VCGLR.

3.2 Conclusion

The liquor licensing and planning permit application processes do not sufficiently reflect community concerns. There are many instances where licences have been granted inappropriately—albeit not illegally—due to inconsistencies and weaknesses in the licensing regime. It is not possible to reliably quantify the extent of the issue due to the antiquated IT systems and the inaccurate, incomplete records VCGLR has inherited from the Department of Justice (DOJ).

The Act has been amended with the aim of achieving better community consultation on liquor licence applications. However, the intent of these changes is not being achieved due to a lack of effective engagement between VCGLR and councils.

Changes have also been made to the planning permit and liquor licence application system to improve the efficiency for stakeholders. Although the system is still not without flaws, councils could nevertheless engage more effectively. VCGLR could help councils in this regard by producing more comprehensive and timely guidance.

DOJ has recently reviewed and improved the industry training. However, inconsistencies in the delivery of the training, and poor quality data, indicate there is a need for closer oversight of training providers and the administration of the accreditation process.

Since the functions of the Victorian Commission for Gambling Regulation and Director of Liquor Licensing were recently integrated into one regulator, it is an opportune time to review their processes for consistency of application where appropriate.

3.3 Evolution of the licensed hospitality industry

There have been many significant changes in liquor legislation. These have been informed by various reviews of the industry, and have reflected changes in community attitudes and government policy regarding alcohol and the licensed hospitality industry.

3.3.1 Outcome of reviews

Successive changes to legislation in the 1980s and 1990s promoted competition and economic development. As these changes took effect, it became easier to obtain a liquor licence, and the number of licensed premises increased as a result. There has been some tightening of controls since 2008.

In 1986, the Nieuwenhuysen report Review of the Liquor Control Act 1968 was released. This review of the policy and legislative environment focused on the potential economic benefits that could be achieved by encouraging growth in the licensed hospitality industry. The review resulted in significant changes to liquor legislation and led to the development of Melbourne’s laneway culture.

However, there was also an unforeseen increase in large nightclubs and bars. These types of premises are associated with increased risk of alcohol-related harm because their late-night trading hours enable people to drink for an extended period.

Prior to 2002, no person or corporation was permitted to own more than 8 per cent of the general or packaged liquor licences. This restriction was deemed to breach the National Competition Policy and was consequently phased out. The number of packaged liquor licences increased 41 per cent between 2002 and 2011.

There have been several changes to the liquor licensing regime since Restoring the Balance: Victoria’s Alcohol Action Plan 2008–13 was launched in 2008, including:

- the harm minimisation objective of the Act has been strengthened by an amendment that broadened the definition of harm

- packaged liquor outlets are no longer exempt from the requirement to obtain a planning permit

- licence categories were amended to better reflect business needs

- a risk-based fee structure was introduced to require licensees associated with the most harm to pay comparatively higher licensing fees.

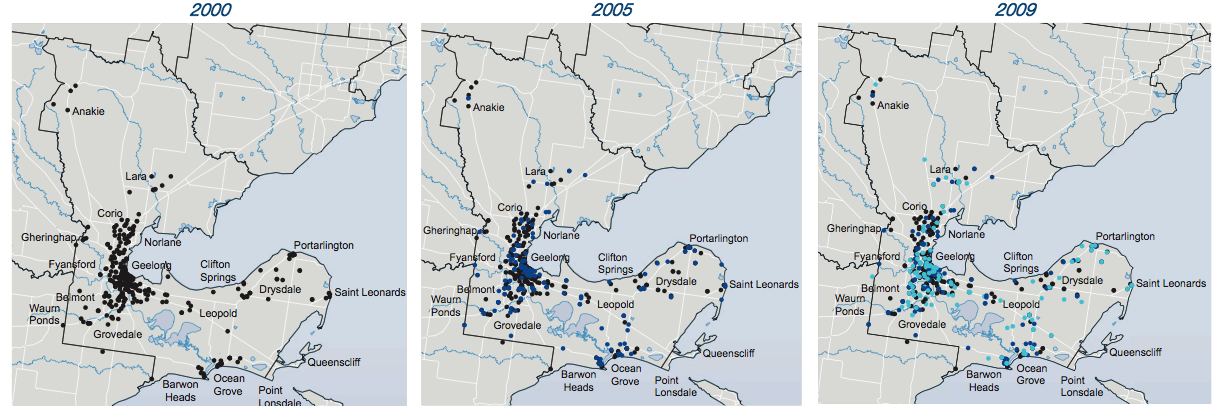

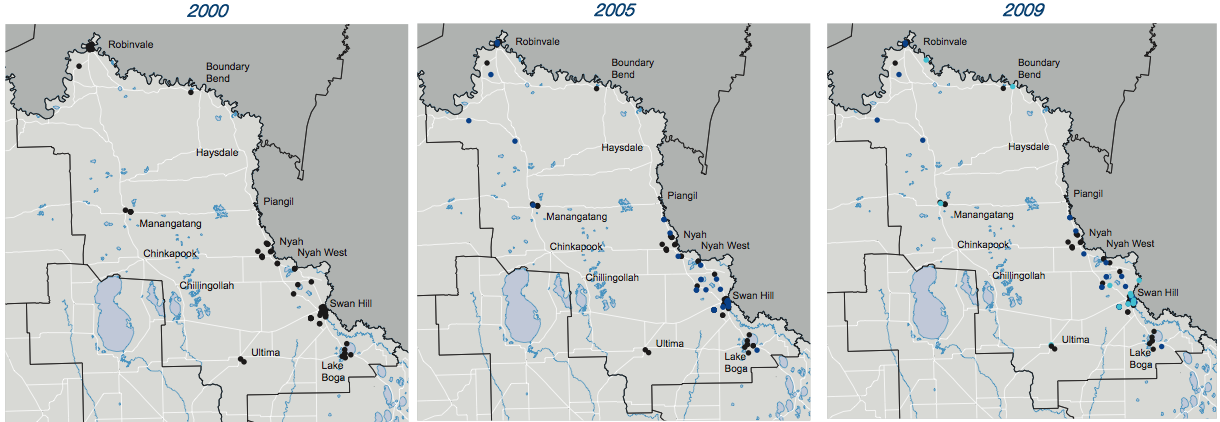

3.3.2 Research findings and industry data

A concentration of licensed premises in a particular area may provide economic and social benefits, such as creating a vibrant night-time activity centre that has a range of businesses and good transport links.

However, there is also evidence that increased outlet density is one factor that can result in a greater incidence of assaults, antisocial behaviour and drink driving. For example, research by Turning Point indicates there is a link between the density of packaged liquor outlets and rates of family violence, and that ‘policies that restrict the growth of the alcohol industry are likely to restrict increases in alcohol-related harm’.

The total number of licences in Victoria has remained relatively constant since 2009. However, the number of licences does not reflect the number of actual licensed premises, because a single venue may have multiple licences for different purposes.

Further, while one licensed premises may have held four or five licences for different activities in the past, VCGLR has worked with licensees to reflect a range of conditions that were previously covered by multiple licences—particularly temporary licences—on a single licence.

VCGLR is unable to measure the year-on-year movement in licensed premises due to poor quality address data.

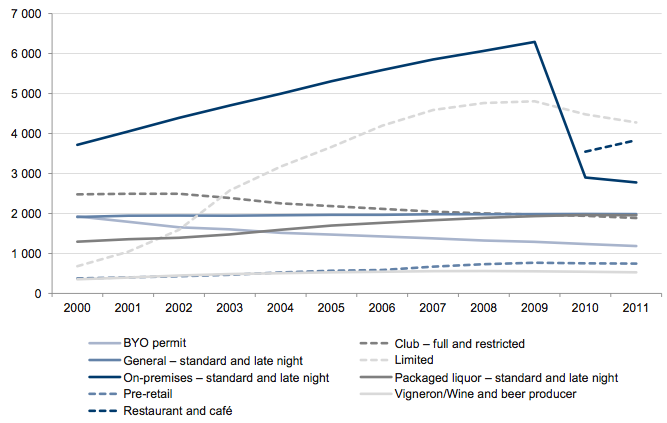

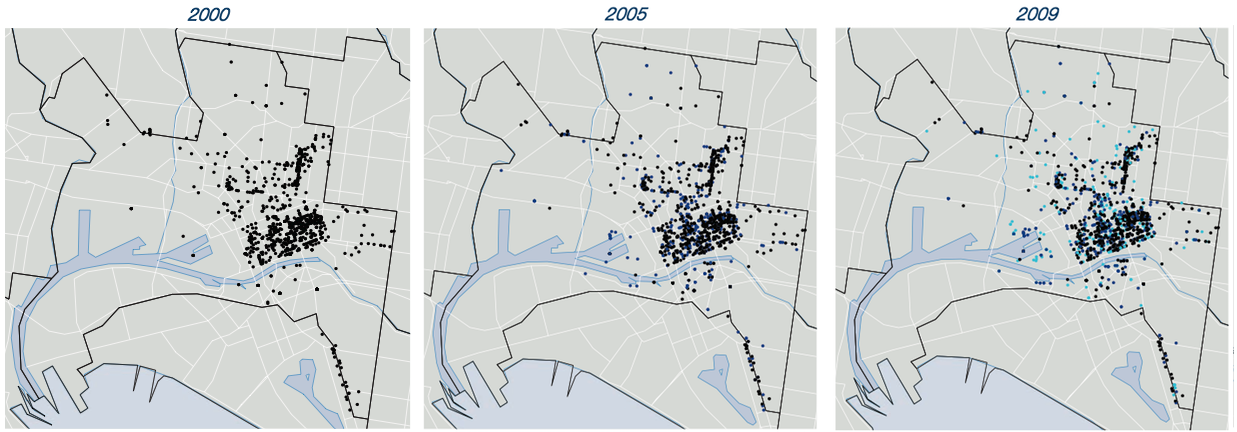

Figure 3A shows the increase in the number of different types of liquor licence in Victoria since 2000.

Figure 3A

Liquor licences as at 30 June 2000–11

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation data.

Alcohol-related harm has increased faster than the number of licences. While the total number of licences increased by 77 per cent between 30 June 2000 and 2011:

- ambulance attendances for intoxication in metropolitan Melbourne increased by 258 per cent between 2000–01 and 2010–11

- the reported number of victims of alcohol-related family violence more than doubled between 2000–01 and 2010–11.

It should also be noted that not all premises are considered to have the same risk of alcohol-related harm. For instance, restaurants and cafés present a lower risk of alcohol-related harm than late-night venues. In 2011, 1 246 new licences and BYO permits were granted. Of these, 62 per cent were for restaurant and café and limited licence types.

Further analysis of harm and the underlying causes is in Appendix A.

3.4 Planning and liquor licensing framework

The harm minimisation objective of the Act is intended to be met by measures including ‘ensuring as far as practicable that the supply of liquor contributes to, and does not detract from, the amenity of community life’.