Individualised Funding for Disability Services

Overview

Disability services in Victoria have been undergoing major reform since the early 1990s. A significant reform has been the development of Individual Support Packages (ISPs). People with ISPs can manage the funds themselves and choose the services and providers that best suit them. At least 7 800 Victorians have an ISP, accounting for 19 per cent of the Department of Human Services' (DHS) disability funds.

The audit found evidence of good outcomes for recipients and that all stakeholders are enthusiastic about the results of ISPs and their ongoing potential. However, benefits are not consistently delivered. Application processes are burdensome, allocation decisions can lack consistency and transparency, and DHS needs greater assurance that funds are spent appropriately. DHS also needs to support and develop the new marketplace in the disability services sector. Current departmental activities and forward planning align with these directions.

Individualised Funding for Disability Services: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER September 2011

PP No 54, Session 2010–11

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my performance report on Individualised Funding for Disability Services.

Yours faithfully

![]()

D D R PEARSON

Auditor-General

14 September 2011

Audit summary

Disability services in Victoria have been undergoing major reform since the early 1990s. Backed by research showing better outcomes, the human rights movement has been promoting the practice of people with disabilities deciding on and directing their own support services. The Disability Act 2006 and the Victorian State Disability Plan 2002–12 embody the principle that people with disabilities should control their own lives and have access to services that meet their needs.

One of the most significant ways the Department of Human Services (DHS) has responded is to offer individualised funding. Early examples, begun in the early 1990s were developed into various flexible funding packages that were consolidated in 2008, to create Individual Support Packages (ISP). People with ISPs can manage the funds themselves and choose the services and providers that best suit them. At least 7 800 Victorians have an ISP, accounting for 19 per cent of DHS disability funds.

The audit objective is to determine the effectiveness of individualised funding for disability services, including whether it:

- meets client needs including choice and control

- supports the provision of high quality services

- supports sector sustainability and capacity.

Conclusions

Victoria is a leader in Australia in reforming disability services, with ISPs playing a prominent role. DHS is empowering people with disabilities by giving them greater control over their funds, services and providers. This promotes the dignity and independence of those in our community with disabilities.

ISPs are benefiting lives. People can now negotiate attendant care hours around their lifestyle and live independently. People with disabilities, their families and carers, advocacy groups, disability service providers and DHS staff are all enthusiastic about the results of ISPs and their ongoing potential.

These successes, however, highlight the importance of allocating ISPs fairly. Accessing an ISP is unnecessarily complex and people are not treated consistently when applying for and planning their ISP. This is leading to inequitable outcomes, which is exacerbated by the fact that demand for ISPs exceeds supply.

While implementing the ISP model, DHS has reviewed and improved it. As ISPs are now a feature of the disability services system, DHS can focus on improving the infrastructure that supports them. This means clearer policy and guidelines, better resource allocation, staff training and monitoring, suitable information systems, and developing a customer-focused culture to help people understand and use the system. DHS needs better risk management to support vulnerable people, and greater assurance that funds are spent appropriately. It also needs to support and develop the new marketplace in the disability services sector.

Current DHS activities and forward planning align with these directions and DHS’s planned full evaluation of ISP outcomes, due March 2013, will drive further improvement.

Findings

Accessing an Individual Support Package

Applying for an ISP is time consuming. The process is hard for people to understand and requires significant administration. A person’s capacity to complete or get help with the application affects its quality and influences the result.

DHS staff assess and prioritise applications inconsistently. They do not always require evidence that the person with a disability directed and consented to the application, or seek an explanation when consent is not provided. These inconsistencies, together with the variable quality of applications, means that acceptance or rejection of the application, and the notional amount of funding and priority status applied, may not actually represent the person’s true need and urgency.

Demand for ISPs exceeds supply. In March 2011, 1 439 people were waiting for an ISP with the value of their requests totalling $38.6 million, $15.6 million more than new funds for ISPs allocated in 2011–12. As a result, people are waiting an average of 1.45 years for an ISP, although 60 per cent wait less than a year. DHS do not have a system to consistently identify people at risk of crisis while waiting, or support those in crisis. DHS regional offices allocate new ISPs without always considering those most in need.

Using an Individual Support Package

People who have ISPs are experiencing real benefits. They enjoy the flexibility to change their supports and providers as needed. They appreciate the control and consumer power of managing their own funds. People have described ISPs to our audit as ‘life-changing’. This is consistent with findings from DHS’s 2005 evaluation of ‘Support and Choice’ packages, the precursor to ISPs.

However, people who have ISPs are finding that planning how to best use their ISP is challenging. DHS has internal and contracted staff called facilitators who help people plan what they will buy with their ISP and from where. People with disabilities are not getting consistently good quality facilitation. DHS has contracted some disability service providers to also facilitate, thus creating a conflict of interest. In addition, contracted facilitators do not always get the same training, supervision and monitoring as DHS facilitators. Poor facilitation means a person may not get the full benefit from their ISP. DHS is planning a statewide training program to remedy this.

DHS recognises that some people are vulnerable and may need extra help to plan and use their ISP. However, DHS is not clear about who is responsible for identifying vulnerable people or how to help make their ISP a success.

The DHS funding administration options allow people to decide the level of control and administration that suits them. While these options give people independence in managing their funds, there are trade-offs. DHS has less assurance that people are spending ISP funds on genuine disability-related needs. DHS’s audit program for direct payments users helps address this, but there is no equivalent for other ISP users, who make up approximately 96 per cent of all ISP users and expend 97 per cent of ISP funds.

Individualised funding and the disability sector

DHS has supported the disability services sector move to individualised funding and services. It has given grants to help the sector adapt, and has targeted good business practices with training and resources. However, analysis of the spread of grants, evaluation findings of one grants program, and feedback from service providers, show that benefits from these activities have not spread through the sector, reducing impact.

DHS quality assurance for disability services is prompting service providers to be more responsive and accountable to their clients. DHS needs to maintain the good results the disability quality framework is achieving as it introduces the single accreditation model across all DHS portfolios.

Individualised funding requires more sophisticated accounting systems. DHS information systems cannot fully account for and transact individualised funding, resulting in work-around systems, significant manual data entry and errors. As a result, service providers regularly experience long delays and errors in DHS payments.

By giving funds and control to people with disabilities, DHS has created a marketplace for the disability sector. This has opened access to new providers offering more options, including in areas that previously lacked services. Individualised funding also allows service providers to expand and change in response to demand and the needs of their customers.

However, a market also creates risks. Complex clients or particular geographical areas may miss out on some services. Service providers also report financial pressures, particularly in providing day services. DHS has not researched disability services and unit prices in the context of ISPs. While provider numbers were relatively static over the past decade, shifts have occurred with mergers, closures and new providers altering the sector. DHS has not defined its role in managing the market, but it will need to if it is to maintain equitable access to high-quality disability services.

Recommendations

That the Department of Human Services:- develop a communication and engagement strategy to help people understand, navigate and use the disability service system and their Individual Support Package successfully

- improve, through training and guidance, staff consistency and fairness in assessing Individual Support Package applications and allocating them and monitoring performance

- investigate the causes of crises and better identify and support people at risk of, or experiencing, crisis

- separate Individual Support Package facilitation from service provision, and support it with consistent training, skill requirements and quality monitoring

- develop guidance on identifying, and planning with, vulnerable people, and clarify roles and responsibilities

- define what is appropriately funded through Individual Support Packages, train staff accordingly and monitor regularly

- develop a risk-based audit system for Individual Support Package users for all funding administration options

- more broadly engage disability service providers in sector development and share learnings across the sector

- develop and implement suitable information technology solutions for recording and tracking individualised funding

- investigate any cost impact of individualised funding on service delivery

- examine its role in managing the disability services market and use a risk-based approach to monitor the sector.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report, or relevant extracts from the report, was provided to the Department of Human Services with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments, however, are included in Appendix A.

1. Background

1.1 Introduction

‘Persons with a disability have the same rights and responsibilities as other members of the community and should be empowered to exercise those rights and responsibilities.’ As the first principle set out in the Disability Act 2006 (the Act), this idea underpins current reforms in disability services, laid out in the Victorian State Disability Plan 2002–12.

The aim of the reform is to focus disability support on individual needs and choices, and the needs of families and carers. Central to this has been to move funding from service providers to people with disabilities—‘individualised funding’. A person with such funds can choose and manage their own services.

Defining disability and disability services

This report adopts the definitions used in the Act. ‘Disability’ in relation to a person means:

-

a sensory, physical or neurological impairment or acquired brain

injury or any combination thereof, which:

- is, or likely to be, permanent; and

- causes a substantially reduced capacity in at least one of the areas of self‑care, self-management, mobility or communication; and

- requires significant ongoing or long-term episodic support; and

- is not related to ageing; or

- an intellectual disability; or

- a developmental delay.

‘Disability service’ is specifically for the support of persons with a disability, delivered by a disability service provider. A ‘disability service provider’ is:

- the Secretary of, and therefore, the Department of Human Services (DHS)

- a person or body registered on the register of disability service providers.

1.2 Individual Support Packages

Victoria used to only fund disability service providers directly through service agreements with DHS. This made it difficult for people with disabilities to change their provider or services.

Over the past decade, DHS has progressively moved to individualised responses. Beginning in the early 1990s, it began introducing flexible funding packages, where the person with the disability was allocated individually attached funding and chose their service providers. In 2008, DHS combined several funding and support packages into one Individual Support Package (ISP), which funds peoples' disability-related needs and goals. Figure 1A shows the main milestones of the reform.

Figure

1A

Milestones in implementing Individual Support Packages

| Date | Activity |

|---|---|

| Early 1990s | First DHS flexible funding packages, mostly for attendant care services. |

| 2002 | The Victorian State Disability Plan 2002—2010 prioritises individual choice and support in disability services. The implementation plan includes flexible funding. |

| 2004 | DHS introduces ‘Support and Choice’ packages, the precursor to ISPs. |

| 2008 | After evaluation of ‘Support and Choice’ DHS combines multiple flexible packages and implements ISPs. |

| Jan 2010 | DHS makes all funding for day services individually attached. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.2.1 Individual Support Packages

The ISP model has three elements:

- Self-directed planning—the person plans the support they need with help, if required. Parents or guardians plan for children.

- Self-directed funding—the person uses their funds to respond to change or preference.

- Self-directed support—tailored services to help the person achieve their goals, for example, to live independently.

An ISP is portable and 'attached' to the person, so they can change service type or provider. The funds in the ISP are set following assessment of the person's need. A person can use a facilitator who will help them plan how to use their package and create a funding plan. Funding is not income, must be used to purchase support directly related to the person's goals and needs, and should not be used where mainstream services are appropriate and available. Support that people purchase with their ISP includes attendant care services, a place in a day service, respite, therapy and so on.

ISP funds are applied in three ways, singly or in combination:

- direct payments to a person or nominated person to buy support in line with their funding plan. The person must sign a deed of agreement with DHS

- use of a statewide financial intermediary service, MOIRA, that holds a person's funding on their behalf and pays bills on request

- direct funding to a registered service provider through a service agreement with DHS. People use this when all, or the majority, of their supports are from one provider.

DHS reviews a person's ISP every three years, or earlier on request, or if DHS decides it is necessary.

1.2.2 Funding for Individual Support Packages

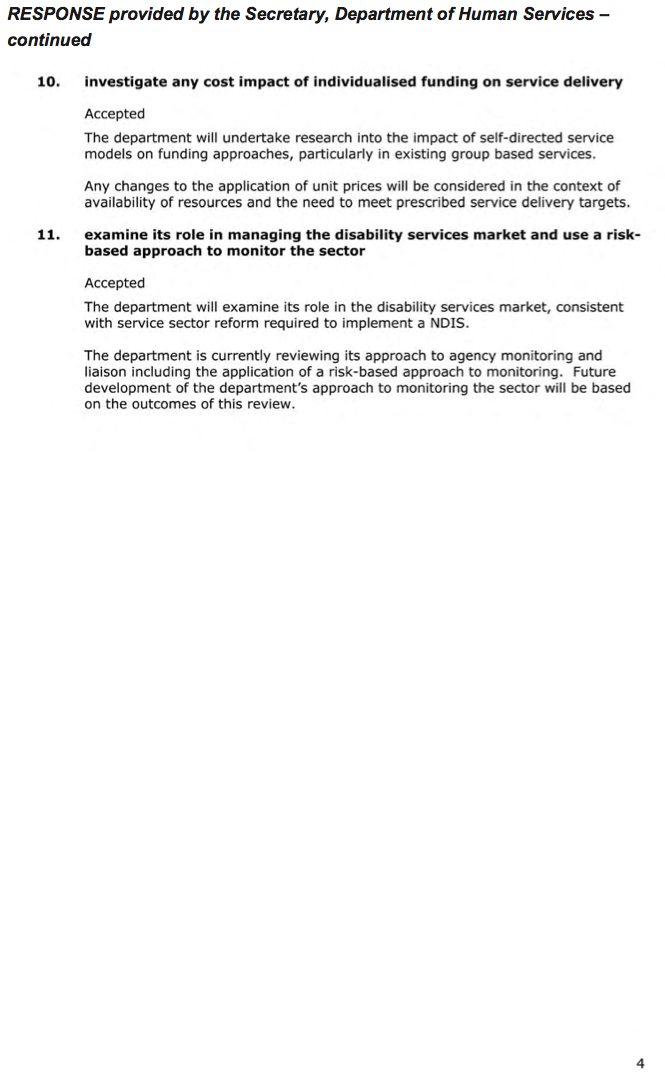

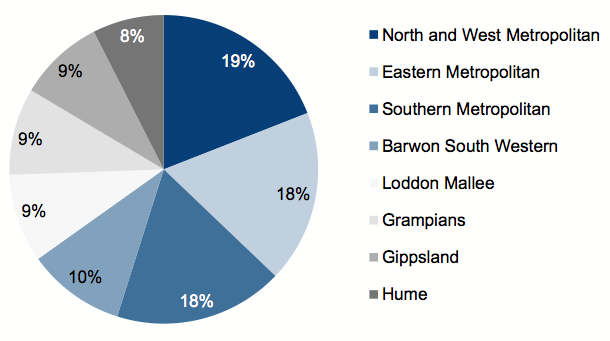

During 2010–11, around 7 800 people had an ISP, and received $263.1 million, or 19 per cent, of the annual total disability funding of $1 370.4 million for that year. Figure 1B shows the percentage breakdown of disability funding in 2010–11.

Figure

1B

2010–11 percentage breakdown of disability funding

Note: ‘Individual support — other’ includes outreach, respite and time-limited flexible funding packages called Futures for Young Adults.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Growth funding

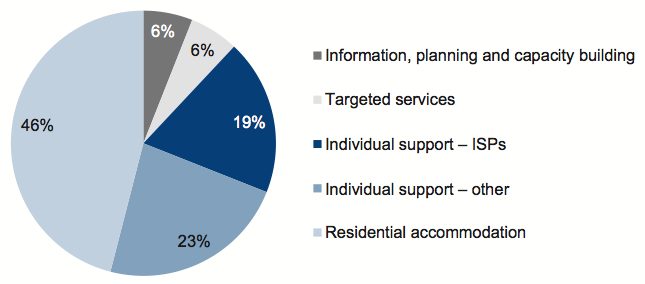

In addition to state funding, the Commonwealth funds ISPs through the National Disability Agreement. Figure 1C shows state and Commonwealth funding contributions for ISPs since 2008, when they were introduced. This totals $112.7 million in recurrent funds for 2 484 packages.

Figure

1C

Growth funding for and number of new Individual Support Packages

| Funder | 2007–08 | 2008–09 | 2009–10 | 2010–11 | 2011–12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commonwealth ($mil) | 0.0 | 10.0 | 12.6 | 21.2 | 23.0 |

| Commonwealth ISPs | 0 | 170 | 214 | 360 | 391 |

| State ($mil) | 8.0 | 29.0 | 7.0 | 1.9 | 0.0 |

| State ISPs | 380 | 690 | 179 | 100 | 0 |

| Total ($mil) | 8.0 | 39.0 | 19.6 | 23.1 | 23.0 |

| Total additional ISPs | 380 | 860 | 393 | 460 | 391 |

Note: The total number of ISPs in the table is less than 7 800, as ISPs converted from other funding types, such as day services and former ‘flexible funding’ packages, are not included in ‘new’ ISP figures.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.2.3 Demand for Individual Support Packages

The demand for ISPs exceeds supply. DHS record approved applications for ISPs on the Disability Support Register (the register). Figure 1D shows the mismatch between new ISPs available each year and the numbers registered for an ISP.

Figure

1D

Comparison of Individual Support Package registrations

and new funded Individual Support Packages

Note: Number registered includes ISPs for day service places and people who already have an ISP but are seeking a funding increase.

People may leave the register when allocated an ISP, or if they move interstate, or no longer need an ISP.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The unfunded cost of the 1 439 people waiting for a new ISP at 31 March 2011 was $38.6 million. This does not count a further 408 people who already have an ISP that have registered for more funds. This greatly exceeds the $23 million available for new ISPs in 2011–12.

1.3 Role of the Department of Human Services

DHS's Disability Services Division (DSD) is responsible for planning, funding, monitoring and developing policies and strategies for disability services. DSD develops the guidelines for ISPs and allocates funds for ISPs to the regional offices.

Regional DHS offices assess eligibility and allocate ISPs. They also manage the transfer and acquittal of ISP funds, and arrange assistance for people to plan their ISP.

1.4 Role of disability service providers

There are over 390 organisations funded via a service agreement that provide services to people with a disability. Of these, over 300 are considered to provide ‘disability services’ as defined by the Act, and are registered as ‘disability services providers’ under the Act.

DHS requires organisations that have a DHS service agreement for provision of ‘disability services’ to be registered as disability service providers. To be registered, an organisation must demonstrate to DHS that they can provide a service for persons with a disability and comply with the Act. DHS also requires funded providers to comply with its quality framework, which means an independent monitor will routinely assess them against quality standards.

Under the ISP model, clients pay their service providers directly or they may ask DHS to pay through a service agreement. Service providers are accountable to their clients, and must provide invoices and/or details of services rendered. The ISP model expects service providers to plan and deliver services in partnership with their clients.

A feature of the ISP model is that clients can also use services not on the register of disability service providers, such as gyms, training institutions or community health services.

1.5 Audit objective, scope and method

The objective of the audit is to determine the effectiveness of individualised funding for disability services, including whether it:

- meets client needs including choice and control

- supports the provision of high quality services

- supports sector sustainability and capacity.

The audit included the DHS central office, one metropolitan and two rural/regional offices. Nearly 100 people were consulted as stakeholders through interviews and forums, including those with disabilities, carers, family members, advocates, and disability service providers. A further 115 service providers participated in an online survey.

The audit complies with Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards.

1.6 Audit cost

The audit cost was $340 000 including printing.

1.7 Report structure

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines accessing an ISP

- Part 3 assesses using an ISP

- Part 4 evaluates individualised funding and the disability sector.

2. Accessing an Individual Support Package

At a glance

Background

To get an Individual Support Package (ISP) people first need to apply for ongoing support and have this application registered on the Disability Support Register. The Department of Human Services (DHS) assesses and prioritises applications, allocating ISPs based on need. Getting the application process right is crucial as it sets up a person's longer-term outcomes.

Conclusion

The process of applying for and getting an ISP produces inequitable outcomes for applicants. The department is aware of these issues and is addressing them.

Findings

- The process of applying for an ISP is hard to understand and requires significant administrative effort.

- Applicants need better support so they can submit good quality applications.

- DHS staff assess and prioritise applications inconsistently.

- The allocation of funding is not always transparent and does not always fully consider those most in need.

- DHS is not consistent in supporting people waiting for an ISP who may be in crisis or are at risk.

- DHS has identified necessary improvements through its own reviews.

Recommendations

That the Department of Human Services:- develop a communication and engagement strategy to help people understand, navigate and use the disability service system and their ISP successfully

- improve, through training and guidance, staff consistency and fairness in assessing ISP applications and allocating them and monitoring performance

- investigate the causes of crises and better identify and support people at risk of, or experiencing, crisis.

2.1 Introduction

People use Individual Support Packages (ISPs) to move from facility-based accommodation or to continue living independently. ISPs help with day-to-day living and in achieving goals such as getting education and work, and they also help support families of children with a disability. An ISP can make a real difference to a person with a disability and their family. It is, therefore, important that the process of applying for and getting an ISP is straightforward, fair and timely.

2.2 Conclusion

People experience inequities accessing ISPs. This is because the process to get an ISP is unnecessarily difficult and is exacerbated by the imbalance between the supply of, and the demand for, ISPs.

Simple, easy-to-find information is lacking and people experience difficulties seeking help with their application.

Department of Human Services (DHS) staff are assessing and prioritising applications inconsistently. Allocations are not always transparent or based on consideration of people's needs, meaning the person in greatest need may not be the next person to receive funding. For people waiting for an ISP, DHS has no consistent way of identifying and supporting those at risk of, or in crisis.

Through its own evaluations DHS has identified many of these issues and their need to improve application, assessment and allocation processes. It has begun making changes that should remain a priority if people are to have fairer access to ISPs.

2.3 Getting on the Disability Support Register

2.3.1 Starting out

Navigating the DHS disability system is not easy. Information is scattered across many web pages and documents, and people can ‘bounce’ between different DHS staff, disability service providers and advocacy agencies looking for help. It is even harder for people with communication difficulties.

People applying for support must demonstrate to DHS that they have a disability as defined in the Disability Act 2006, which may require evidence like medical assessments. Once DHS is satisfied the person has a disability, it decides if they meet a range of ‘priority of access indicators’, including:

- the person's safety, well-being and quality of life

- whether there are multiple causes of disadvantage affecting the person's life

- the strength and supportiveness of family, carers and community networks

- whether disability support is mandated, e.g., as part of a justice plan.

This process may take weeks or months, depending on whether the person has to see medical staff, therapists, or case managers to get evidence for DHS.

2.3.2 The application process

To get an ISP, people first need to apply for ongoing support and have this application registered on the Disability Support Register (the register). DHS expects the applicant and relevant family, carers and support people to help plan the application. The planning should identify the person's goals, current support and additional support needed to meet their goals.

In line with DHS funding principles, the application should only request support that:

- does not replace or duplicate other state, Commonwealth or local supports

- excludes costs other people would reasonably be expected to pay, such as for travel, internet, utility, membership or recreation costs

- demonstrates the most cost-effective and innovative use of resources.

People can complete the application themselves or get help from family, their case manager if they have one, or DHS. ISP users and their carers, advocates and service providers, consistently reported that completing an application for the register is difficult.

First, the planning can take time. The person needs to carefully consider their needs, and explore and exhaust all alternative support options.

Second, DHS offers little information about how to complete the application. Advice about general planning principles is provided, but there is no specific information available, or examples provided, on how to complete the form. The disability service providers and case managers we consulted through three regional forums also reported that they are reluctant to help apply as they feel the task is time consuming and that DHS does not fund them for it adequately.

Third, people asking DHS for help may have to wait. Even when a person gets help, they may not be skilled enough to complete the application correctly. Review of client files showed that DHS frequently has to ask for changes and more information, further drawing out the process.

2.3.3 Assessing applications

For DHS to register someone, the application must demonstrate:

- the person's consent and input, as much as possible

- that alternate support was explored and found lacking or inappropriate

- that requested support relates to the person's disability needs and their goals

- enough detail for DHS to accurately cost the requested support and apply a notional funding band to the application.

If any of these points are missing, DHS should request amendments. However, review of client files showed that staff are inconsistent in doing this. For example, DHS accepts applications that are unclear about whether the person consented to, or directed the application. To comply with DHS's own policy principles, all applications should include either the person's written consent, or an explanation by their representative of how their input to the application was sought.

Applications are approved that show little evidence of exploring alternate support, while other applications had to show extensive evidence. Sometimes there is not enough detail to cost the application accurately but a notional funding amount is still applied. DHS staff, within and between regional offices, interpret DHS funding principles differently. DHS's own 2011 audit of registration practices found that lack of staff training and guidance had contributed to inconsistent decision-making. These inconsistencies have created confusion among disability service users and their supporters about how to apply for an ISP. This can result in applications that do not accurately represent a person's needs, leading to insufficient funding when an allocation is made.

2.4 Who gets an Individual Support Package?

2.4.1 Allocating Individual Support Packages

The number of new ISPs available each year depends on targets and funds provided to DHS by the state and Commonwealth governments. DHS also reallocates ISPs that are returned when someone passes away, moves interstate, or no longer needs one.

Centrally, DHS allocate funds to the eight regional offices, setting each region targets for new packages to allocate in each funding band. There are four main funding bands, broken to 17 levels. Each level has a range of around $5 000. The targets aim to spread ISPs across people ranging from low to high needs.

DHS policy is that people with priority status have first access. Priority status is given to:

- children in facility-based care

- people at risk of harm to themselves or others

- people wishing to move out of, or avoid moving to, facility-based care

- people diagnosed with a rapid degenerative condition

- people in an extreme situation.

Regional offices manage ISP allocations to people on the register. Figure 2A shows how regions allocate or short-list people for ISPs.

Figure

2A

Allocating Individual Support Packages from the Disability Support Register

| Situation | Action |

|---|---|

| ISP target matches the number on the register at that funding band with priority status | Automatic funding |

| ISP target matches the number on the register at that funding band, both priority and non-priority | Automatic funding |

| ISP target is less than the number on the register at that funding band with priority status | People with priority status short-listed for consideration by ‘priority for allocation’ panel |

| ISP target exceeds the number on the register at that funding band with priority status, but there aren't enough packages for non-priority | Priority people automatically funded Non-priority people short-listed for consideration by ‘priority for allocation’ panel |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The ‘priority for allocation’ panel considers risks and potential benefits for each short‑listed applicant and is required to record its recommendations for each. DHS policy is that the ‘priority for allocation’ panel must include:

- a person with a disability

- a family member or carer of a person with a disability

- regional DHS staff at no more than 60 per cent of the panel

- at least two representatives from disability service providers.

Central office also permits regions to negotiate the split of targets across levels. Regions might combine smaller packages to create a larger one, or split a larger package to better match the need in their region.

2.4.2 Allocations in practice

DHS aims to allocate ISPs based on need. In practice this does not happen consistently. While regions are required to meet targets, there is scope to negotiate with central office to better align targets to regional need. However, regions do not routinely look beyond targets to identify people most in need. For example, if a region is set a target of two ISPs at a specific band, the region will only consider people registered at this band, even when it may have a high priority person, in another band, who needs frequent emergency support. This was particularly apparent in one audited region. Their allocations panel had not met since June 2010 as ISPs had only been allocated against targets.

One of three regions audited did not have the required external members on its allocation panel and panel minutes did not record all people considered or the reasons for recommendations. DHS's audit of registration practices also found non-compliance with panel membership, where DHS members exceeded 60 per cent and the required external members were not included.

The accuracy of the register also determines whether DHS allocates ISPs based on need. DHS requires registrations to be updated annually. However, at 31 March 2011, DHS had only reviewed 43 per cent of applications on the register within the one month due date, against a target of 80 per cent. This means DHS cannot be assured that it is allocating ISPs on up-to-date information.

DHS central office monitors the percentage of people given priority status in its regional offices. There is, however, a significant level of unexplained variation between regions that indicates they are interpreting priority criteria differently. The DHS internal audit in 2011 also found this. This means DHS give a different priority status to people in similar circumstances.

2.4.3 Waiting on the Disability Support Register

DHS does not refer to the register as a ‘waiting list’ and does not consider how long a person has been on the register when it allocates ISPs. Instead, it focuses on a person's need. However, people on the register do wait.

At March 2011, 1 439 people were waiting for an ISP with the value of their requests totalling $38.6 million, $15.6 million more than new funds for ISPs allocated in 2011–12. People waited an average of 1.45 years for an ISP, with 60 per cent waiting less than a year. While this has improved from December 2008 when wait times were around two years, at March 2011, almost 200 people on the register had been waiting five or more years.

People waiting rely on support from family and carers, community service organisations, and services like Home and Community Care. They may also get short‑term services from DHS. Individuals and advocacy bodies gave examples of cases where these supports were insufficient and the person and their family fell into crisis, causing family breakdown and placement of a person in facility-based care.

DHS has no consistent, coordinated system for identifying people at risk of crisis, or funding and managing those in crisis. People told us that emergency funding from DHS, while appreciated, adds stress due to its uncertainty and the repeated administration each time funding runs out.

2.5 Improving resource allocation

DHS, through its program of work to reorient disability services, internal audits and evaluations, has recognised the problems with the register application form and information for users, and the variation in how staff assess applications. It has started two projects to improve the registration process and allocate ISPs more fairly.

2.5.1 The Disability Support Register review

The register review began in January 2010 with two aims—to make registration across regions consistent, and to improve people's understanding and experience of the process. The review has included consultation with service users, community service organisations, peak bodies and DHS regions. Main actions include updating staff guidelines, staff training, improving communication with people applying to, or on the register, and developing new community information resources to explain the register. This work was due for completion in August 2011, with implementation to follow.

2.5.2 The Resource Allocation Framework

The Resource Allocation Framework is the DHS response to the problem of consistently and accurately capturing disability-related need and then assigning appropriate funding. In May 2009, DHS commissioned a research institute to design a tool to consistently and fairly identify:

- a person's goals

- their disability-related needs

- their ‘unmet’ needs

- the funding amount required for the unmet need.

The new tool will facilitate more consistent allocation of resources based on relative need and help to remove the variation caused by applications of different quality and inconsistent interpretation by DHS staff. The tool is being developed and tested using data from current ISP users. DHS plans to trial it in early 2012, introducing it in 2012–13.

Recommendations

That the Department of Human Services:

- develop a communication and engagement strategy to help people understand, navigate and use the disability service system and their Individual Support Package successfully

- improve, through training and guidance, staff consistency and fairness in assessing Individual Support Package applications and allocating them and monitoring performance

- investigate the causes of crises and better identify and support people at risk of, or experiencing, crisis.

3. Using an Individual Support Package

At a glance

Background

For a person to get the most benefit from their Individual Support Package (ISP) they need support to make informed decisions about what works best for them, and to plan and manage their ISP.

Conclusion

ISPs are making a positive impact on people's lives, including helping more than 200 people to move from shared supported accommodation to live independently. Nonetheless, the Department of Human Services (DHS) has opportunities to improve the quality of assistance provided in ISP planning and acquitting ISP funds.

Findings

- DHS's written information on planning and using ISPs is not helping people sufficiently to understand how their ISP works.

- People's experiences of facilitation are inconsistent and can affect ISP outcomes.

- There is insufficient guidance on identifying, and planning with, vulnerable people.

- There is inconsistency in what DHS approves in funding plans.

- DHS needs better processes to check that ISP funds are spent appropriately.

Recommendations

That the Department of Human Services:

- separate ISP facilitation from service provision, and support it with consistent training, skill requirements and quality monitoring

- develop guidance on identifying, and planning with, vulnerable people, and clarify roles and responsibilities

- define what is appropriately funded through ISPs, train staff accordingly and monitor regularly

- develop a risk-based audit system for ISP users for all funding administration options.

3.1 Introduction

A person can only get the most out of their Individual Support Package (ISP) if they are able, with assistance as required, to know all their options and make choices that work for them. Access to information and support is essential for achieving effective outcomes.

The transfer of funds to individuals creates new risks and responsibilities, requiring the Department of Human Services (DHS) to educate ISP users and monitor outcomes.

3.2 Conclusion

ISPs allow people with disabilities to experience greater choice and control in deciding how they wish to live their lives, and what supports will best help them achieve their goals. That ISPs are supporting more people to live with independence in the community is a significant achievement.

The extent to which those with an ISP experience positive outcomes, however, depends on their capacity to make informed decisions. Where they need support to make choices, the quality of support available when planning an ISP varies considerably and is not always of a sufficiently high standard. This, together with differences among DHS staff in what they give funding approval for, is leading to inequitable outcomes for ISP users. DHS has identified the variance in facilitation and staff funding approvals, and has started work to improve quality and consistency in these areas.

DHS has adequate controls for ISP users who directly manage their funds to assure they spend funds appropriately. However, assurance mechanisms for those using other funding administration options are insufficient.

3.3 Outcomes from Individual Support Packages

ISPs give people with disabilities greater choice and control in their lives, allowing them to achieve daily tasks more easily, improve basic life skills and live independently. The 34 ISP users and carers we consulted consistently reported positive outcomes from their ISP. This is consistent with findings from DHS's evaluation of ‘Support and Choice’ packages, the precursor to ISPs. DHS is currently planning a full evaluation of ISPs due for completion in March 2013.

One of the successes of individualised funding is that more than 200 people since 2002, through their choice, have been able to move out of facility-based care into living options with more independence. Figure 3A quotes people with disabilities and carers describing the impact an ISP has made in their lives.

Figure

3A

Individual Support Package outcomes

‘The ISP has made a difference ... It has relieved the feeling of being a burden. It has created a sense of calm within the whole family, even the kids.’

‘He (client) is so happy, the happiest he has been in years. It is a weight off our mind that we have this ongoing funding. I am absolutely stoked about the ISP, still in disbelief!’

‘She (the client) has increased opportunities ... the flexibility suits us when her health needs change ... there's less stress ... we have increased choice and control over things.’

‘I do like my ISP. It really makes a difference ... I can be more independent and I can live on my own. I'm a better cook now.’

‘12 months ago, I went on holiday to Queensland with some friends. I could use funding to purchase attendant care so I could do my share and help out with cooking. This was good.’

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Not everyone however, is equally able to gather, understand and explore all the information necessary to make the best choices when using an ISP. People with disabilities and their family members and carers feel that DHS can do more to make it easier for people to know their options. Figure 3B describes some of their experiences.

Figure

3B

Peoples' experiences understanding their Individual Support Package

‘I don't think I've received enough information about how the ISP works. I don't know how I would manage (in the system) if I couldn't communicate as well as I can. How hard must it be for others? I feel real empathy for them.’

‘The type and way DHS provides information isn't meeting needs and varies across the regions. There is a website but you have to be savvy to use it.’

‘It is even more difficult for culturally and linguistically diverse communities to understand what an ISP is ... they have no support whatsoever ... they can't self-direct if they don't have the language; they can't navigate the system.’

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Since 2008, DHS has funded initiatives to strengthen the participation of people with disabilities and their supporters in choosing how they use their ISP. Activities have included training programs on self-advocacy and developing communication and decision-making skills to manage their ISP. However, DHS has primarily targeted day service users in its initiatives to date, and have not invested evenly across the state. DHS has recognised this and is focussing a current grants initiative specifically on building peoples' skills and confidence to use an ISP. DHS plans to evaluate activities to date by 2013.

3.4 Planning how to use an Individual Support Package

3.4.1 Facilitation

The Disability Act 2006 (the Act) requires disability service providers, including DHS, to provide those who request it with assistance in planning the use of an ISP. DHS uses facilitators for this and their role is to support people to make informed decisions about how they use their ISP, manage their funds and implement their plan.

People can choose:

- a DHS facilitator

- an external facilitator contracted by DHS from a disability service provider or a community-based organisation, such as a local council

- to plan themselves or with the help of family, carers or another supporter.

A facilitator should have good interpersonal and communication skills to work with people with disabilities, knowledge of, and networks with, both disability and other community-based services, and creativity to help identify the best way to meet a person's needs and goals.

Quality of facilitation

ISP users, carers, advocates and services providers all gave examples of poor experiences with external facilitation services. This is largely because of variation in the quality of experience, training and monitoring between DHS and external facilitators. This situation is compounded by potential conflicts of interest where external facilitators are also service providers, and by people's lack of clear expectations of facilitators. DHS's 2005 review of ‘Support and Choice’ packages, the precursor to ISPs, also found inconsistent quality of facilitation and that independence of facilitation was important for a successful outcome.

External facilitators do not always get the same training, supervision and monitoring as DHS facilitators. External facilitators receive varied training from their employers and written guides from DHS. Discussion with external facilitators during the audit revealed knowledge gaps that DHS could address through training. DHS recognised this issue prior to the audit and is currently developing a statewide training program, for external facilitators and their managers, for implementation in 2011–12.

The ISP handbook provided to users explains that electing to use a facilitator also provides consent for DHS to share ‘relevant information’ with that facilitator. However, in practice DHS do not always convey to external facilitators information that would be useful to assist the planning process: for example, a person's communication needs and the support person(s) who should be included in planning. The lack of this information can lead to a poor experience of facilitation for the person with a disability.

DHS closely monitors the quality of internal facilitation. However, there is a lack of consistent, regular monitoring of the quality of external facilitators. Some agencies contracted to provide facilitation services are also disability service providers. This creates the potential for bias in advice, limiting a person's choice. DHS reviews ISP funding plans by external facilitators before approving them, but could not demonstrate that it consistently obtains evidence of the person's consent to the plan.

DHS invested an estimated $6.6 million in facilitation services in 2010–11. This is a worthwhile investment when good planning adds value to people's lives. However, the variation in external facilitators shows that DHS needs better assurance of the quality of ISP funding plans developed by them. One of the audited regions was addressing this by developing surveys for people both before and after using external facilitators.

ISP users interviewed for the audit said that they were unsure what to expect from their facilitator. DHS could drive quality in facilitation by better informing people about the standards they can expect from facilitators, and what a good facilitation service looks like.

3.5 Assessment and approval of funding plans

Regional DHS staff approve a funding plan based on whether it is in line with funding principles, demonstrates the person's involvement in planning and that they explored a variety of options for providing support. DHS staff should complete an assessment of the plan within 14 days of its receipt.

Similar to the problems identified with assessing applications for the Disability Support Register (the register), there is inconsistency in what DHS approves at this stage. DHS has also identified this issue through an internal audit of ISP processes. This creates confusion about what to request, lengthens approval time frames, and produces inequitable outcomes.

One of the regions audited did not consistently meet the time lines for approval. A review of ten client files in the region found three examples where funding plans were still not finalised eight to nine months after submission of the first draft. Regional staff reported that the backlog of funding plans related to staffing issues. DHS also does not monitor the time it takes from draft plan to approval and, so, does not identify lengthy cases. Though people may receive interim funds while awaiting approval, they are restricted during this time from receiving and managing their funds directly and some services require funding confirmation before commencement.

3.6 Funding administration options

People appreciate being able to use their funds flexibly and choose the level of control and responsibility over their funds. They can choose from three funding administration options that they can use solely or in combination. Figure 3C outlines these options.

Figure

3C

Funding administration options

| Disability service provider | Financial intermediary | Direct payments |

|---|---|---|

| Arrangement | ||

| DHS allocates funding to a registered disability service provider through a service agreement to deliver or purchase services on behalf of a person in line with the funding plan. | The financial intermediary (MOIRA) holds the ISP funds on behalf of the recipient, and pays invoices approved by the person for services in line with their funding plan. | Funds are paid directly to the recipient who then purchases the supports from service providers to meet the goals of their funding plan. |

| Reporting requirement | ||

Service providers are required to:

|

MOIRA is required to:

|

|

| Benefits | ||

|

|

|

| Weaknesses/limitations | ||

|

|

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Comprehensive audits of all direct payment users during its trial found no instances of funds misuse. DHS has only found one such instance since direct payment started as a pilot in 2006. The ongoing annual audit program of 10 per cent of direct payment users appropriately balances the need for assurance with the level of risk and administrative burden on DHS and ISP users. DHS does not apply a 10 per cent audit to the other two funding models despite equivalent risk of inappropriate funding use. Expenditure through service providers and MOIRA accounts for 97 per cent of ISP funds. A broader risk-based audit approach would provide greater assurance about the appropriate expenditure of funds. DHS is currently reviewing whether existing controls are adequate and that ISP users and service providers comply with them.

3.7 Supporting vulnerable people

DHS recognise that some people are vulnerable and may need more support to plan, implement and manage their ISP. DHS guidelines state that a person may be vulnerable if they:

- have difficulty communicating their needs

- do not have supporters to assist in decision making and monitoring supports

- or their supporter(s) cannot demonstrate that they understand the implications of their decisions.

A risk for a vulnerable person is that their ISP plan may reflect the preferences or beliefs of others and not truly reflect their own needs. In the worst-case scenario, a vulnerable person's funds could be misused if the right supports are not put in place. Figure 3D provides two case studies that demonstrate this.

Figure

3D

Vulnerable people

Case study 1

X has an intellectual disability and has an ISP to live independently. They mostly use their ISP for attendant care. Examination by an advocacy agency revealed that the carers were not adequately supporting X and making fraudulent claims for shifts or travel with X without X's knowledge. X's supportive family were unable to help as they were not included in planning X's ISP and so did not know how it worked or what they could do.

Case study 2

Y uses the financial intermediary administration option, and uses some of their funding for travel. MOIRA noticed an unusual increase in Y's taxi expenditure and referred this to DHS. An investigation revealed that Y's housemate had been using the vouchers for personal use without Y's knowledge.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

These case studies highlight the need to identify and support vulnerable people, and for a broader audit program of ISP funds. DHS has not clarified whether DHS staff or facilitators are responsible for identifying if someone is vulnerable. External facilitators do not have access to DHS client case files to help identify factors that indicate vulnerability. DHS also does not provide guidance to facilitators on ways they can mitigate risks for vulnerable people, such as involving relevant support people in planning and monitoring the ISP, or scheduling more frequent reviews. This would assist in assuring the person's needs are met and funds are used appropriately.

3.8 Managing an Individual Support Package

A person may choose to make changes to their supports for a number of reasons, such as changing needs or dissatisfaction with the support provided. As service users are becoming more aware of what having an ISP means, they are embracing their ‘consumer power’. ISP users we interviewed described feeling increasingly confident about negotiating services with providers, changing providers and making complaints.

The only changes that require DHS approval are those that involve changing a goal or funding administration arrangement, or that request additional funding. DHS consider additional funding requests against the priority criteria and funding availability. For requests over $5 000, DHS require the person to submit a new application to the register. Due to the difficulties in applying to the register as discussed in Part 2, ISP users told us they would be reluctant to submit a new request.

Recommendations

That the Department of Human Services:

- separate Individual Support Package facilitation from service provision, and support it with consistent training, skill requirements and quality monitoring

- develop guidance on identifying, and planning with, vulnerable people, and clarify roles and responsibilities

- define what is appropriately funded through Individual Support Packages, train staff accordingly and monitor regularly

- develop a risk-based audit system for Individual Support Package users for all funding administration options.

4. Individualised funding and the disability sector

At a glance

Background

A strong disability services sector allows people with disabilities to get the most from their Individual Support Package (ISP). Consumer control of funds is shifting the sector to a market model.

Conclusion

The introduction of ISPs has not significantly changed the disability sector, though providers are starting to better tailor services to their clients. The Department of Human Services (DHS) does not yet have a strategy in place to identify, monitor and manage risks and opportunities within this new market.

Findings

- DHS has invested in grants and training to help the sector adapt to individualised funding and services, though it has had limited reach.

- The DHS quality framework monitors service quality successfully.

- There are opportunities to improve relations between disability service providers and DHS through a partnership approach.

- DHS has not researched disability services and unit prices in the context of individualised funding.

- DHS has yet to define its role as a market manager or how it will monitor and mitigate emerging market risks.

Recommendations

That the Department of Human Services:

- more broadly engage disability service providers in sector development and share learnings across the sector

- develop and implement suitable information technology solutions for recording and tracking individualised funding

- investigate any cost impact of individualised funding on service delivery

- examine its role in managing the disability services market and use a risk-based approach to monitor the sector.

4.1 Introduction

Individual Support Packages (ISPs) are only useful to people with disabilities if they can buy support from a range of accessible, relevant and high-quality services. The strength of the disability services sector is vital in achieving good results from individualised funding.

4.2 Conclusion

Individualised funding is driving disability providers to change their services and the way they operate. The Department of Human Services (DHS) has worked to help the sector to change, but its reach has been limited. Both DHS and service providers recognise that future initiatives require a greater partnership approach for success.

DHS lacks the information technology (IT) infrastructure needed to support individualised funding. This is hampering DHS and service providers from accurately and efficiently accounting for ISP funds. Current manual accounting practices are unsustainable.

The advent of a disability services market requires DHS to identify, analyse and address the opportunities and risks. However, it has not yet developed a formal position and strategy for its role in managing the disability services market. While the sector will respond to consumer demand, DHS will need to intervene if the market fails to provide equitable access to high quality disability services. As more people administer their own funds, DHS will have less direct control over disability services and will need to find new ways to influence disability service supply.

4.3 The disability services sector

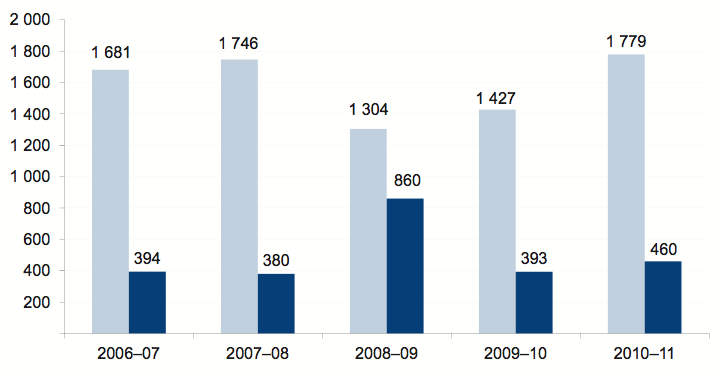

Community service organisations (CSOs) provide most disability services. As at January 2011, 393 CSOs were providing nearly $700 million worth of DHS-funded disability services including attendant care, accommodation and day services. Of these, 241 were providing services to people using an ISP.

Figures 4A and 4B show the spread of disability service providers by DHS funding and region respectively. The majority of providers, 65 per cent, receive less than $1 million from DHS.

Figure

4A

Community service organisations

by Department of Human Services funding level

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure

4B

Community service organisations by region

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

4.4 Making the change to individualised funding

As part of its broader disability sector development, DHS has supported the implementation of ISPs through three initiatives, the:

- Service Reorientation Program

- Victorian Industry Development Plan

- Quality Framework for Disability Services.

4.4.1 Service Reorientation Program

The Service Reorientation Program began in 2008, continuing work started in 2004. The program aims to help providers meet the intent of the Disability Act 2006 and the Victorian State Disability Plan 2002–12 of maximising the choice and independence of people with disabilities. DHS convened an advisory group of industry and service user members to assist the program. Figure 4C lists the program's main initiatives.

Figure 4C

Service reorientation initiatives for disability service providers

| Initiative | Description | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Changing Days | To support innovation in day services, increasing flexibility and responsiveness to individuals | $4.2 million in grants over four years from 2006–07. 52 CSOs funded. |

| Enhanced Capacity | To help CSOs improve business systems to support service reorientation and ISPs | $15 million in grants over five years from 2008–09. 45 CSOs have received grants. |

| Community Facility Redevelopment Initiative | Physical infrastructure grants to improve access, flexibility and links with mainstream services | $6.4 million in grants over four years from 2006–07 to 2009–10. 16 CSOs received grants. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Other activities include guidance for service providers to help client decision-making, and an update of accounting and reporting functions in the Client Relationship Information System for Service Providers, which providers use to report to DHS and maintain client records.

4.4.2 Victorian Industry Development Plan 2006

The Victorian Industry Development Plan 2006, the ‘industry plan’, came from the Victorian State Disability Plan 2002–12. It aims to support sector change by addressing workforce, governance, and strategic planning issues. Advisory groups of service providers and users are informing its implementation.

DHS has made good progress in gathering and analysing workforce information as set out in the industry plan. Initiatives more directly related to helping CSOs have included:

- training and resources to assist risk management

- the Enhancing Good Governance project including around 200 training sessions

- guides for business planning, staff training and finding resources to help organisational performance.

4.4.3 Quality Framework for Disability Services

DHS introduced the Quality Framework for Disability Services in 2007. The framework sets out standards for client outcomes and uses independent certification to monitor compliance. The assessment incorporates feedback from service users. The framework is thorough and gives useful feedback to DHS and providers on continuous improvement.

The framework supports individualised funding in CSOs as the standards promote client direction of services. The sector also supports the framework. Of the more than 100 responses to this audit's provider survey, over 80 per cent reported moderate to high value from the framework.

DHS is changing the framework to implement the One DHS Standards. This will create a consistent, independently monitored quality mechanism for all DHS services. CSOs providing disability, housing and child services will now do only one independent assessment instead of three, reducing their compliance burden. Standards in the disability framework translate to the One DHS Standards. However, the transition will mean administrative changes for CSOs which have already invested in the framework, and DHS will need to revise its training and resources.

4.5 Disability sector impact

How well these initiatives have aided disability service providers in adapting to individualised funding is unclear. An evaluation of Changing Days grants found positive outcomes for most projects and that reforms were accelerated in funded agencies. While the quality framework is effective, DHS will monitor the impact of the revised framework and determine whether to revise its target for certification of all CSOs by 2012. DHS has yet to evaluate the impact of Enhanced Capacity grants or initiatives within the industry plan.

There is little evidence of knowledge dissemination across service providers following grants funding. Analysis shows that DHS awarded 48 per cent of grants to only 13, mostly large, CSOs. The Changing Days evaluation concluded that effectiveness was reduced as lessons were not shared across agencies. Service providers in regional forums also questioned the timing of Enhanced Capacity grants, feeling they followed rather than preceded DHS changes. Figure 4D shows results from this audit's provider survey. The results suggest that DHS methods for engaging with, and supporting the sector to adapt, could have been more effective.

Figure 4D

Service provider survey results

| Survey question | Yes (per cent) | No (per cent) |

|---|---|---|

| Were you consulted by DHS on the implementation of ISPs? | 65.4 | 34.6 |

| Were you satisfied with the level of consultation from DHS? | 41.2 | 58.8 |

| Did DHS adequately consult the broader disability sector in planning and implementing ISP? | 37.6 | 62.4 |

Did your organisation receive sufficient assistance from

DHS, e.g. training, resources, grants to implement:

|

||

|

31.3 | 68.7 |

|

41.7 | 58.3 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

DHS has put effort into developing and funding activities to support the sector's adaptation. However, its limited reach throughout the sector has reduced the effect. Disability service providers suggest that the way forward is a greater partnership between them and DHS. DHS has also articulated this aim, which should guide future initiatives for sector development.

4.6 Managing individualised funding and services

4.6.1 Challenges for the Department of Human Services

Accounting for Individual Support Packages

Allocating funds to individuals rather than CSOs significantly increases DHS's administration. It must now process ISP variations in service agreements with CSOs and funding managed though MOIRA – the financial intermediary, and direct payments to individuals. Variations may occur due to:

- a person changing service type, provider or funding administration option

- a person entering or leaving the system

- a person getting an increase or decrease in their ISP

- annual indexing and unit price or wage changes for services.

One change to a person's ISP can affect five different databases. As DHS designed its IT systems to manage funding transfers with contracted service providers they do not have the functionality to manage funds attached to individuals. In 2008, the Business Relationship Management Branch advised that existing IT systems were inadequate for individualised funding.

As the systems do not interface, data transfer is done manually, diverting staff from services that more directly benefit clients. One large region that was audited needs more than two full time staff to process ISP variations. Manual data entry also generates errors. Service providers consistently report delays, often of several months, and inaccuracies in DHS payments. DHS errors affect the ability of service providers to maintain accurate client accounts. Regional DHS staff acknowledge these problems and predict that with ISP users increasing, current practices are unsustainable.

4.6.2 Challenges for disability service providers

ISPs require new administrative practices by disability service providers. Service providers need to invoice clients who use financial intermediary and direct payment options, and follow up debtors. The principles of individualised services and client expectations are also driving service providers to change the services they deliver and how they are delivered. Participants in regional service provider forums and over 80 per cent of respondents to the audit's provider survey reported increased organisational costs associated with ISPs.

The adequacy of unit prices for disability services is a matter of contention in the sector. The government raised unit prices in 2008 for attendant care services, though subsequent successive bids by DHS to increase day service unit prices were unsuccessful. The attendant care price review supported continuation of flat hourly rates, based on a typical service mix at that time and continuation of the pre-ISP model that then existed. This remains the current funding approach. The review noted that varying the unit price for services supporting community access and on weekends would better respond to client preferences. The price review for day services did not consider the impact of more individualised services on funding and was only based on traditional service delivery. DHS has not reviewed how service mix and type has changed under individualised funding and whether there are any subsequent cost changes.

Some disability service providers can clearly offer services within current unit prices that meet ISP principles, though feedback from service providers suggests others are struggling. Given the tension this issue creates between disability service providers and DHS, further research is warranted on any cost impact of individualised funding and services on providers and how best to manage it. Accurate unit prices are essential for a person to have enough ISP funds for the services they need.

4.7 A disability service market

By providing people with disabilities with funds and choice, DHS has given them consumer power, creating a disability services market. This brings both opportunities and risks.

4.7.1 Opportunities

Historically, contracts between DHS and disability service providers restricted growth and innovation. Individualised funding allows providers to respond to client demand, changing their products and growing where possible. This is driving a shift from traditional group-based programs to services tailored to peoples' individual interests and that engage them in the community.

Individualised funding has also allowed new providers to enter the sector. Organisations can provide disability services without being on the Register of Disability Service Providers and having a service agreement with DHS. One of the audited regions gave an example of a local health service that now offers disability services. Previously, the area had no disability support so the health service has created a new option in the community.

4.7.2 Risks

The market gives service providers the power to select clients, creating risk that some people with disabilities may be considered less desirable and thus experience difficulty finding a provider. Service providers reported in regional forums that those most at risk are people with complex needs and challenging behaviour who require more intensive staff support. Providers said they already are, or are seriously considering, refusing access to clients who might cause a financial loss.

It is inevitable that over time the market influence will alter the sector. Given cost‑related challenges and the need to develop and market more sophisticated services, some smaller providers may struggle. There is potential risk of service diversity loss and geographical gaps in a sector that already has some supply side deficits.

Another potential risk is with non-registered providers. People with disabilities are no longer limited to registered providers. People can buy services with their ISP from gyms, community health services, education institutions and so on. DHS advises people using non-registered providers that the protections of registration, including access to the Disability Services Commissioner, will not apply. While this option expands choice for people with disabilities, there are risks, particularly for vulnerable people, if services are not of sufficient quality. This highlights the importance of support for vulnerable people in planning and managing their ISP, as discussed in Part 3.

4.7.3 Managing the market

While DHS is giving purchasing power and choice to people with disabilities, the department still needs to provide equitable access to high-quality disability services. This task now includes monitoring and managing the market and addressing the risks.

To date, DHS reports little change in the sector. ISP funds make up only 26 per cent of DHS funding to providers. At January 2011, ISP users had spent 84 per cent of ISP funds for 2010–11 through traditional DHS service agreements with registered disability service providers. Of the remaining, 13 per cent were spent through MOIRA, and 3 per cent through direct payments. People still largely seek services from registered providers as people typically buy disability service provider products, with almost 70 per cent of funds spent on attendant care.

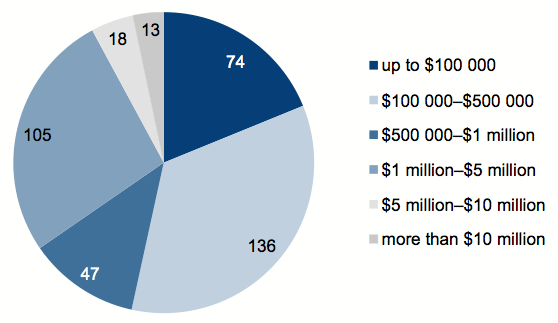

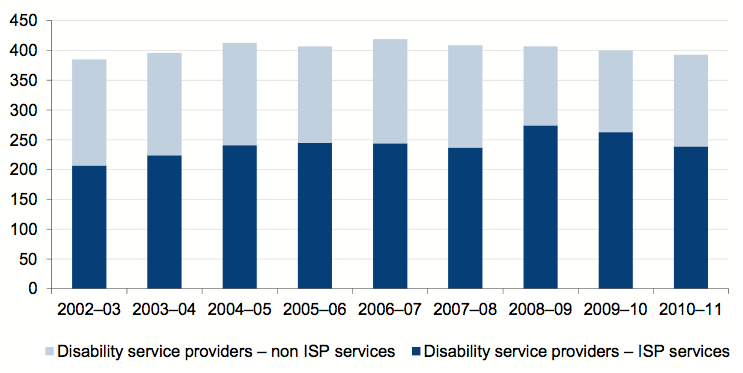

Figure 4E shows the number of DHS-funded providers. Numbers have stayed static over the last decade. Changes since 2008 include one service closure, three mergers of smaller with larger providers, ten providers leaving the sector and six new providers.

Figure 4E

Number of Department of Human Services funded

disability service providers

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

DHS does not have a clear position on the role it will play within the market, or on how it will judge market performance or address potential risks. At present, the central Disability Services Division sees its regional offices having the main role in watching their local area and working with disability and other service providers to address market gaps. DHS needs a more formal and centrally directed approach to avoid potential risks, especially as more people use ISPs and choose MOIRA or direct payments to administer their funds.

Recommendations

That the Department of Human Services:

- more broadly engage disability service providers in sector development and share learnings across the sector

- develop and implement suitable information technology solutions for recording and tracking individualised funding

- investigate any cost impact of individualised funding on service delivery

- examine its role in managing the disability services market and use a risk-based approach to monitor the sector.

Appendix A.Audit Act 1994 section 16—submissions and comments

Introduction

In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Human Services with a request for submissions or comments.

The submissions and comments provided are not subject to audit nor the evidentiary standards required to reach an audit conclusion. Responsibility for the accuracy, fairness and balance of those comments rests solely with the agency head.