Managing the Environmental Impacts of Transport

Overview

The environmental impacts of the Victorian transport system are significant and include the production of greenhouse gas emissions, other air pollution and noise.

Minimising these impacts has been a legislated objective since 2010, but it is clear that the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure (DTPLI) has not adequately addressed this when developing the state's strategic transport and land-use planning framework (the strategic framework)—consisting of Plan Melbourne, Victoria—The Freight State and the state's eight regional growth plans.

During the strategic framework's development, DTPLI did not provide the government with any advice:

- about how proposed strategies would address the environmental impacts of the transport system

- proposing defined statewide objectives or targets for reducing transport‑related greenhouse gases and other emissions and for limiting the effect of traffic noise.

In the absence of DTPLI developing a comprehensive monitoring and reporting framework with clearly defined expected environmental outcomes and performance measures, the framework currently remains aspirational in this regard.

Across the three agencies examined, VicRoads has the most comprehensive strategy for managing environmental impacts, and this is a model for what should exist on a portfolio-wide basis.

Public Transport Victoria (PTV), on the other hand, does not have a dedicated plan and its performance in this regard has declined since our 2012 audit, Public Transport Performance. Specifically, PTV did not progress options identified by the former Department of Transport on how to improve public transport's energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. Further, the quality and availability of publicly-reported information on public transport's environmental performance has declined.

Managing the Environmental Impacts of Transport: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER August 2014

PP No 347, Session 2010–14

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Managing the Environmental Impacts of Transport.

The audit assessed how well the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure (DTPLI) is fulfilling its strategic leadership role and how well VicRoads and Public Transport Victoria (PTV) are managing the environmental impacts of transport.

I found that DTPLI did not adequately fulfil this role when developing the state's strategic transport and land-use planning framework. This is because it did not provide the government with any specific advice on how proposed actions would address the environmental impacts of transport, nor did it propose any statewide objectives or targets for reducing transport-related greenhouse gases, other emissions and noise.

VicRoads has a comprehensive plan for improving the environmental performance of the road system, and this is a model of what should exist on a portfolio-wide basis. PTV, on the other hand, does not have a dedicated plan and its performance in this regard has declined since our previous audit, Public Transport Performance.

I have made a series of recommendations aimed at addressing these issues. I am encouraged by the commitment of VicRoads and PTV to implementing actions against these recommendations, and encourage DTPLI to fully embrace the recommendations of this report.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

20 August 2014

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Steven Vlahos—Sector Director Verena Juebner—Team Leader Hayley Svenson—Analyst Daniel Mahoney—Analyst Dallas Mischkulnig—Engagement Quality Control Reviewer |

Auditor-General's comments

The Victorian transport system produces significant amounts of greenhouse gases, other air pollution and traffic noise that pose a growing threat to our environment and health. Minimising these impacts has been a legislated objective since the Transport Integration Act 2010 (the Act) was introduced in July 2010.

Under the Act, the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure (DTPLI) has the key leadership role to ensure the transport system is delivered consistent with transport system objectives. The Act requires DTPLI to establish the overarching planning framework within which other transport bodies are to operate. It also requires Public Transport Victoria (PTV) and VicRoads to minimise adverse environmental impacts from the road and public transport systems, respectively, within the context of this framework.

DTPLI finalised the statewide strategic framework, consisting of Plan Melbourne, Victoria—The Freight State and the state's eight regional growth plans, in July 2014. The government has subsequently adopted this framework. However, my audit found that during the framework's development, DTPLI did not adequately advise government about how the proposed strategies would address the environmental impacts of transport. The framework also did not propose any statewide objectives or targets for reducing transport-related greenhouse gases, other emissions and noise.

As it does not clarify the environmental objectives it is seeking to achieve, DTPLI's proposed strategic framework is largely aspirational. To increase the likelihood of improved environmental performance, DTPLI needs to set clearly defined expected outcomes and comprehensively report on progress against these.

Across the three agencies examined, I found that VicRoads has the most comprehensive strategy for managing the environmental impacts of the road system. Indeed, its Sustainability and Climate Change Strategy 2010–2015 is a model of what should exist on a portfolio-wide basis. Encouragingly, this strategy includes specific actions and goals for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, improving air quality and minimising traffic noise impacts, and VicRoads regularly publicly reports on its progress.

Conversely, I found that PTV has not sufficiently progressed options identified by the former Department of Transport on how to improve public transport's energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. Additionally, the quality and availability of publicly reported information on public transport's environmental performance has declined since 2012.

I have made 11 recommendations to address the shortcomings identified by this audit. In particular, the recommendations reinforce the need for DTPLI to develop statewide objectives and a related framework to monitor and report on the performance of the transport system in meeting the Act's environmental sustainability objective.

I am disappointed by DTPLI's less than fulsome acceptance of my recommendations for it to develop a statewide strategy to address the environmental impacts of the transport system. The Act makes it clear that DTPLI's role is to lead all of the strategic policy, advice and legislation functions relating to the transport system, and to determine strategic policies that address related current and future challenges.

As noted in my report, the environmental impacts of the transport system are significant and growing. Addressing this major challenge for the state's current and future generations, and proactively advising the government on potential policy responses is clearly within the scope of DTPLI's obligations under the Act.

The recommendations reinforce the need for PTV to develop a similar framework and to address the shortcomings identified by this audit and our 2012 audit. I also recommend that VicRoads develops arrangements to monitor and report on the environmental impacts of initiatives to improve traffic flow and the mode share of public transport. Encouragingly, both PTV and VicRoads have accepted these recommendations and have committed to address them.

I look forward to receiving updates from these agencies on their progress in implementing the recommendations.

Finally, I would like to thank the staff of DTPLI, VicRoads and PTV for their assistance and cooperation during this audit.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

August 2014

Audit Summary

Background

Victoria's transport system is vital for moving people, services and goods, with Melburnians making close to 14.2 million trips across the city each day. Consequently, the environmental impacts are significant and include the production of greenhouse gas emissions, other air pollution and noise.

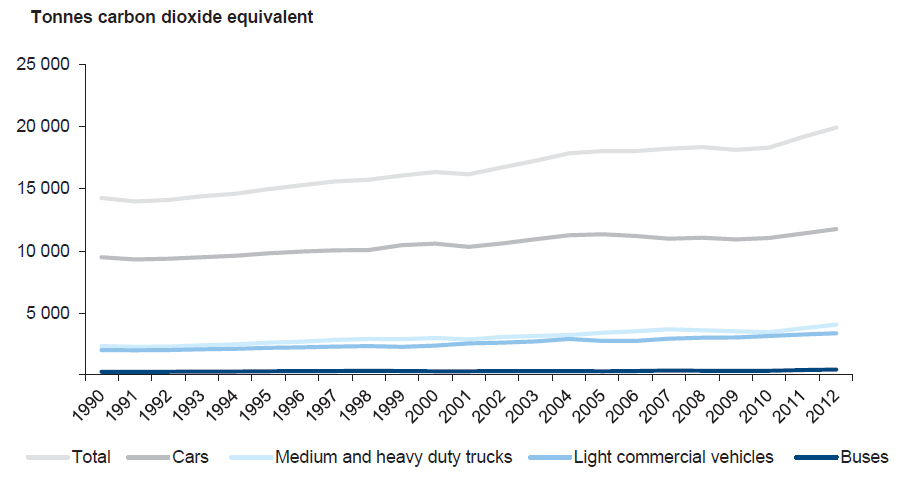

The transport sector is the second largest producer of greenhouse gases in Victoria. Total emissions from this sector grew by 41.2 per cent from 1990 to 2012 and accounted for 18.72 per cent of Victoria's total greenhouse gas emissions in 2011–12.

Passenger cars are responsible for approximately 60 per cent of Victoria's transport‑related greenhouse gas emissions. While total emissions from public transport are significantly lower than from both passenger and freight vehicles, in Victoria trams and trains are particularly greenhouse gas-intensive modes as they rely primarily on electricity produced from brown coal.

Transportation noise is also of community concern, particularly in residential areas, where exposure to high noise levels can have adverse health and social consequences.

Typical approaches for reducing transport emissions include:

- reducing the demand for travel

- increasing the use of non-vehicular modes

- leveraging new technologies

- reducing emissions from transport infrastructure.

The Transport Integration Act 2010 (the Act) requires transport agencies to manage the transport system in a way that actively contributes to environmental sustainability. This includes minimising transport-related emissions, promoting less harmful forms of transport and improving the environmental performance and energy efficiency of all transport modes. This objective must be balanced with the other transport system objectives.

Under the Act, the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure (DTPLI) has the key leadership role in planning for and managing the transport system in a way that addresses these objectives. VicRoads also has a role in minimising the adverse environmental impacts of the road system and Public Transport Victoria (PTV) has a similar goal of seeking to improve the environmental performance of the public transport system.

This audit assessed whether the environmental impacts of transport are being effectively managed. It examined how well key institutional arrangements support statewide and agency-level strategic planning, monitoring and reporting for managing the environmental impacts of transport, and the effectiveness of key strategies and initiatives in reducing the impacts of transport on the environment.

Conclusions

The environmental impacts of the transport system are significant and growing. Minimising these impacts has been a legislated objective since 2010, but it is clear that DTPLI has not adequately addressed this when developing the state's strategic transport and land-use planning framework (the strategic framework)—consisting of Plan Melbourne, Victoria—The Freight State (VTFS) and the state's eight regional growth plans (RGP).

During the strategic framework's development, DTPLI did not provide the government with any advice about how proposed strategies would address the environmental impacts of the transport system. It also did not propose any defined statewide objectives or targets for reducing transport-related greenhouse gases and other emissions or for limiting the effect of traffic noise.

Without these objectives and standards, DTPLI's proposed strategic framework is largely aspirational. Their absence also significantly reduces DTPLI's accountability for performance and impedes its capacity to effectively oversee and transparently report on the outcomes of related initiatives across the portfolio. Consequently, it is unlikely that agency actions will be effective in minimising the environmental impacts of the transport system.

Across the three agencies examined, VicRoads has the most comprehensive strategy for managing the environmental impacts of the road system, and this is a model of what should exist on a portfolio-wide basis. The strategy has specific goals and actions for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, improving air quality and minimising traffic noise impacts. VicRoads also regularly reports on progress and can demonstrate that it is improving the environmental performance of the road network.

However, neither DTPLI nor PTV has a corporate strategy with clear objectives, targets and performance measures for environmental performance. This means they cannot demonstrate that their actions to minimise the environmental impacts of the transport system have been effective.

It is particularly concerning that public reporting by both agencies on relevant indicators has diminished substantially over time and that PTV has failed to act on previous recommendations to improve its management and reporting on the environmental performance of public transport.

Findings

Statewide strategic planning and governance

DTPLI advised that Plan Melbourne, VTFS and the RGPs contain 'the mix of integrated actions considered best able to achieve the state's desired outcomes, including environmental outcomes'. However, its claim cannot be verified, because during the framework's development DTPLI neither clarified nor advised the government on what specific environmental outcomes its proposed strategic framework seeks to achieve.

Specifically, DTPLI's related advice omitted critical details on statewide objectives, targets and performance measures for minimising the environmental impacts of transport, including for reducing greenhouse gases and other emissions.

This means the strategic framework developed and proposed by DTPLI did not provide a clear basis for transport agencies to align their policies and actions. The lack of targets and performance measures also significantly impedes DTPLI's ability to measure the effectiveness of agencies' progress against statewide objectives and to assess whether the aims of the strategic framework and desired environmental outcomes have been achieved.

DTPLI advised that this framework has since been adopted by the government.

Environment-related content in the strategic framework

The strategic framework developed by DTPLI recognises the link between proposed actions and their potential to minimise harm to the environment from the transport system.

Specifically, Plan Melbourne promotes an efficient and more environmentally sustainable city shape based on modelling that shows a smaller number of larger activity centres, with contained fringe growth, will increase carbon efficiency. However, DTPLI did not define the related outcomes and targets for agencies to work towards to achieve the environmental sustainability objective of the Act.

Plan Melbourne encourages an increase in public transport, cycling and walking, and VTFS seeks to promote a shift to rail freight. While these initiatives support the achievement of a more sustainable transport system, DTPLI cannot assess their effectiveness in the absence of clearly defined objectives and targets. In the absence of DTPLI developing a comprehensive monitoring and reporting framework with clearly defined expected environmental outcomes and performance measures, the strategic framework currently remains aspirational in this regard.

Advice to government

DTPLI did not advise the government on options for Plan Melbourne to address the environmental sustainability objective of the transport system.

During the development of Plan Melbourne, the Ministerial Advisory Council (MAC) proposed a number of detailed actions and specific targets to minimise the environmental impacts of transport. However, DTPLI did not advise the government on the merits or otherwise of the MAC's proposed actions and targets, and these were not adopted in the final strategic framework.

During the audit, DTPLI asserted that targets are a matter for government and are not necessary for measuring progress.

However, the establishment of clear targets and benchmarks for assessing the achievement of objectives is a fundamental and widely accepted practice of good governance and public administration. They are also necessary for transparently assessing the adequacy of progress made. While the government has the prerogative to adopt or reject proposed targets, this does not negate DTPLI's obligation to provide frank and fearless advice to the government on the merits of such targets. It also does not preclude DTPLI from establishing such standards internally, including performance monitoring arrangements to assess the impacts of its initiatives and to transparently demonstrate its environmental performance to the government.

Statewide governance and monitoring arrangements

DTPLI's Transport Planning Group, which has responsibility for coordinating with other transport agencies across the portfolio, does not actively monitor progress against the transport system objectives, including the environmental sustainability objective.

Therefore, while DTPLI has a Transport Outcomes Framework (TOF) for measuring the impact of transport system actions in achieving the Act's objectives, this is not being actively monitored. The absence of statewide targets for key indicators also significantly limits the TOF's effectiveness.

DTPLI advised that it is currently developing a new TOF that will better support the monitoring of outcomes against the Act's environmental sustainability objective. However, this work is still at a very early stage. DTPLI should ensure that this initiative is complemented by public reporting against statewide targets for defined environmental outcomes.

Managing the environmental performance of the road and public transport system

The Act requires all transport agencies to develop corporate plans that give effect to their obligations under the Act and support achievement of the transport system's objectives. DTPLI's corporate plan must also specify strategic priorities and performance measures for the transport system, against which VicRoads and PTV must align their plans.

DTPLI corporate planning and reporting

DTPLI's current corporate plan, developed in 2011, does not define specific strategic priorities and performance measures for managing the environmental performance of transport. An updated plan for 2013–14, still in draft form, is yet to include any specific objectives to address improving the environmental performance of the transport system.

Consequently, DTPLI's corporate plan does not adequately support the achievement of the Act's environmental sustainability objective nor provide an adequate basis for guiding VicRoads and PTV to effectively align their corporate plans and related strategies with DTPLI's.

Further, DTPLI does not systematically report on environmental outcomes achieved across the portfolio, and has discontinued many of the outcome measures previously reported by the former Department of Transport (DOT). While it continues to report on public transport patronage, this measure alone is not sufficient for assessing whether the environmental performance of the transport system has improved.

VicRoads corporate planning and reporting

VicRoads has the most advanced strategic planning and reporting framework of the three agencies audited. Its Sustainability and Climate Change Strategy 2010–2015 addresses the key environmental impacts of the road system and establishes clear goals to reduce transport-related greenhouse gas emissions, improve air quality and minimise traffic noise impacts. It is underpinned by key performance indicators (KPI) to measure progress, clearly assigned responsibilities for action, internal monitoring of emissions abatement outcomes achieved and regular public reporting.

These arrangements are encouraging, as they support transparency and accountability for performance. However, most KPIs are output focused, and thus the framework could be further improved by developing measures to assess the impact of related actions on improving the environmental performance of the road system.

VicRoads advised that it is currently updating its strategy with new strategic directions and corporate KPIs. Although this work is at an early stage, it expects these directions will include a focus on further enhancing measurement of greenhouse gas abatement and the improvement in air quality and noise as a result of implemented actions.

PTV corporate planning and reporting

Our 2012 audit, Public Transport Performance, identified a number of shortcomings in the former DOT's approach to managing and reporting on the public transport system's environmental performance. However, PTV has made little progress on implementing related recommendations.

Importantly, PTV has yet to develop a dedicated strategy for managing and reporting on the environmental performance of the public transport system. Publicly reported information by PTV related to the system's environmental performance has also significantly decreased since 2012. In addition, its current corporate plan does not specify any actions for improving the environmental performance of public transport.

PTV's network-level plans aim to boost public transport mode share, as well as mode shift from cars. They also outline some limited strategies for improving energy usage and associated pollution. However, there are no explicit goals or targets for these initiatives, so their effectiveness cannot be transparently assessed.

During the audit PTV developed a new draft corporate plan which has more explicit strategic priorities to improve the mode share of public transport and reduce the environmental footprint of the public transport system. This is encouraging, however, PTV needs to develop detailed actions, targets and performance measures to support the achievement of these goals and address the shortcomings identified by this audit and our previous 2012 audit, Public Transport Performance.

Lessons from other jurisdictions

South Australia and Transport for London represent better practice examples for setting clear, measurable strategic objectives and targets for improving environmental performance. Both jurisdictions have clearly defined environmental strategic priorities and actions, including targets that support transparent reporting on the environmental performance of their transport system.

Impact of recent agency initiatives

DTPLI initiatives to improve the transport system's environmental performance

DTPLI is undertaking a number of initiatives to move towards a more sustainable transport system. Key initiatives include a focus on making it easier for people to use more sustainable forms of transport and improving the environmental performance of the transport fleet.

Two of its related actions, FleetWise and the electric vehicle trial, have potential environmental benefits, and DTPLI should investigate how these can be more actively leveraged across the broader transport system.

Initiatives to manage the environmental impacts of the road system

VicRoads is systematically addressing the key environmental impacts of the road system through the mix of coordinated actions and initiatives under its Sustainability and Climate Change Strategy 2010–2015. Encouragingly, it has also demonstrated positive outcomes to date.

For example, by replacing incandescent traffic signal installations with LED lanterns between 2010 and 2012, VicRoads has delivered an estimated 11 241 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent savings in greenhouse gas emissions a year.

Initiatives to manage the environmental impacts of the public transport system

PTV has not made sufficient progress in improving the energy consumption and related emissions from public transport. Our 2012 audit, Public Transport Performance, noted that the former DOT's draft internal report from November 2011,Victorian Public Transport Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions, recommended steps to better manage and measure public transport's energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. The audit also highlighted the need for the former DOT to develop an implementation plan to do this. While the former DOT committed to address this, PTV has yet to develop such a plan.

PTV has also not investigated the costs and benefits of sourcing energy from renewable energy sources, which represents a key opportunity to improve the environmental performance of the public transport system.

Recommendations

That the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure, in consultation with other transport agencies:

- develops a statewide strategy that sets out clear strategic priorities and actions, with statewide objectives, targets, and performance measures to address the environmental impacts of the transport system

- reviews its governance arrangements and establishes mechanisms to monitor and coordinate related agency actions

- establishes arrangements to measure and report on the performance of the transport system and related agencies in meeting the environmental sustainability objective of the Transport Integration Act 2010, including improvements in greenhouse gas emissions, air quality and noise as a result of portfolio-wide strategic interventions and implemented actions.

That the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure:

- ensures that the priorities and performance measures contained in the proposed statewide strategy are reflected in the department's and relevant portfolio agencies' corporate plans.

That VicRoads:

- ensures that key performance indicators developed under its new five-year strategy and corporate plan are outcomes focused to measure the impact of related actions on the environment.

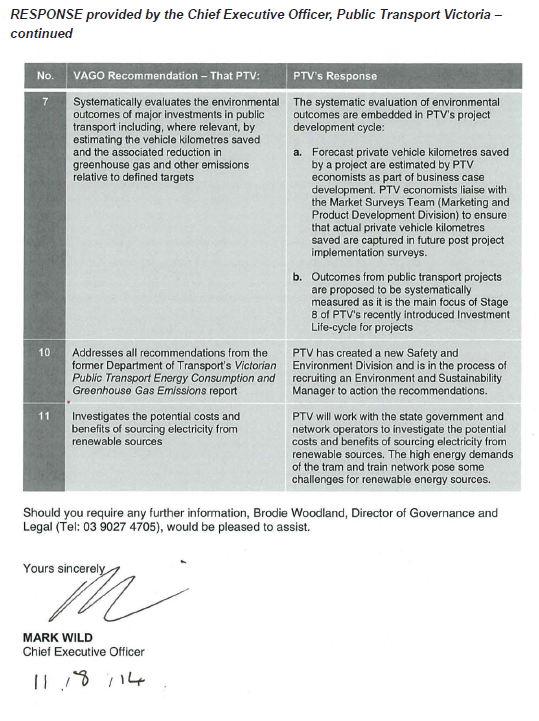

That Public Transport Victoria:

- develops specific actions, targets and related performance measures to support achievement of defined statewide priorities for improving the environmental performance of the public transport system, and publicly reports on its related performance against these measures each year

- systematically evaluates the environmental outcomes of major investments in public transport including, where relevant, by estimating the vehicle kilometres saved and the associated reduction in greenhouse gas and other emissions relative to defined targets.

That the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure:

- publicly reports on the outcomes of the FleetWise and electric vehicle trials, and investigates related opportunities for applying any insights to further improve the environmental performance of the transport system.

That VicRoads:

- develops arrangements to monitor and report on the environmental impacts of its initiatives to improve traffic flow and the mode share of public transport.

That Public Transport Victoria:

- addresses all recommendations from the former Department of Transport's draft Victorian Public Transport Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions report

- investigates the potential costs and benefits of sourcing electricity from renewable sources.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report, or part of this report, was provided to the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure, VicRoads and Public Transport Victoria with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

1.1.1 Environmental impacts of the Victorian transport system

Victoria's transport system is vital for moving people, services and goods, with Melburnians making nearly 14.2 million trips across the city each day. However, the environmental impacts are significant and include the production of greenhouse gas emissions, other air pollution and noise.

Greenhouse gas emissions

Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Commonwealth Government has committed the nation to unconditionally reducing its emissions by 5 per cent compared with 2000 levels by 2020. It has committed a further 15 to 25 per cent reduction by 2020, dependent on the extent of international action.

Victoria's Climate Change Act 2010 requires the state's responses to climate change to complement those of the Commonwealth, including in relation to targets or caps on greenhouse gas emissions.

The transport sector is the second largest producer of greenhouse gases in Victoria. Total emissions from this sector grew by 41.2 per cent from 1990 to 2012 and accounted for 18.72 per cent of Victoria's total greenhouse gas emissions in 2011–12. Typical greenhouse gas emissions from transport are carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide, which contribute to global warming.

Figure 1A

Greenhouse gas emissions in Victoria by mode

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from the Commonwealth Department of the Environment's National Greenhouse Gas Inventory, Kyoto Protocol Accounting Framework.

Passenger cars are responsible for approximately 60 per cent of Victoria's transport‑related greenhouse gas emissions. Emissions from light commercial vehicles and trucks are lower, but freight emissions are expected to double by 2020 from 1990 levels.

Total emissions from public transport are significantly lower than both passenger and freight vehicles—around 871 000 tonnes during 2010–11. However, trams and trains are particularly greenhouse gas-intensive modes as they are major energy consumers that rely primarily on electricity produced from brown coal. Their environmental benefits are therefore greatest when patronage is highest during peak periods, making their per-passenger emissions substantially lower than those from passenger cars.

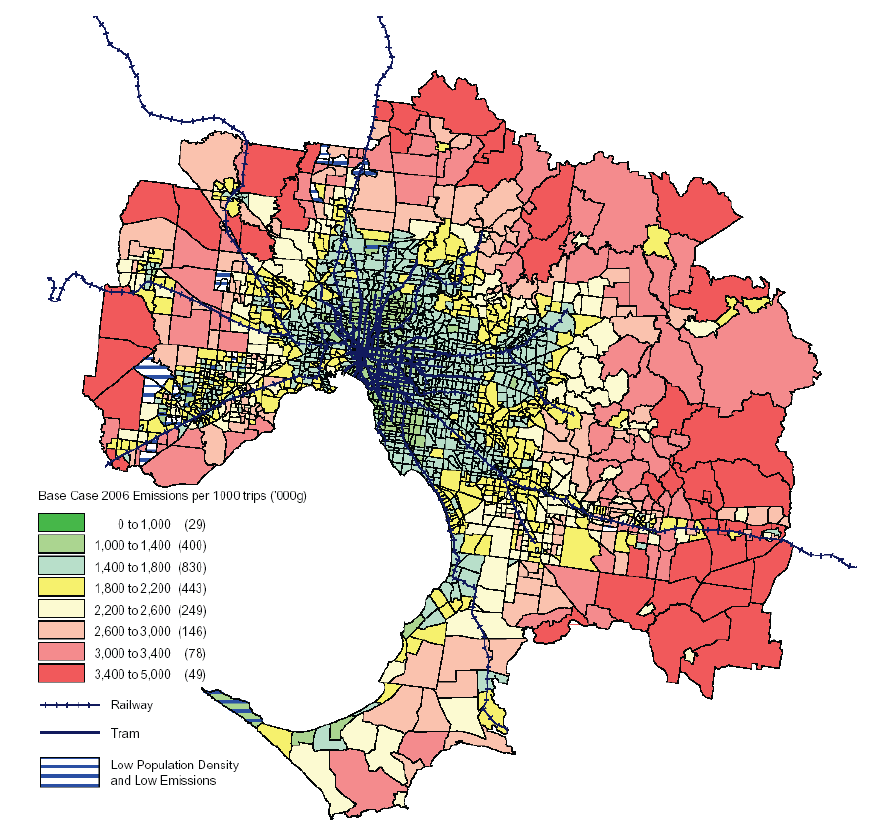

Average transport emissions per passenger vary across Melbourne, as shown by Figure 1B. The outer suburbs and growth areas tend to have a much higher transport emissions footprint than inner Melbourne due to less public transport, greater reliance on cars, and greater distances travelled to reach activities and services in those areas.

Figure 1B

Passenger transport greenhouse gas emissions by home location

Source: Whiteman, J. & Alford, G., 'A Spatial Analysis of Future Macro-Urban Form' 2006, as reproduced in Public Transport Victoria's draft Public Transport Policy Objectives document.

Overall, transport in Australia is projected to remain a high emitter of greenhouse gases in the future. The Commonwealth Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics (BITRE) estimated that under a 'business as usual' scenario, there will be a 48 per cent increase in transport-related emissions from 1990 levels by 2020.

Production of other air pollution

Motor vehicles—including passenger cars, light commercial vehicles and trucks, buses, and motorcycles—contribute up to 70 per cent of total urban air pollution in the Port Phillip Region alone. In particular, they contribute more than 60–70 per cent of nitrogen oxide and up to 40 per cent of hydrocarbons. These chemicals combine to form the main component of photochemical smog.

Motor vehicles are also a major source of particulate matter and various other toxins such as nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, ozone and benzene. Particulate matter that can penetrate the lungs includes particles smaller than 10 micrometres in diameter (PM10) and those smaller than 2.5 micrometres in diameter (PM2.5). The Environment Protection Authority's (EPA) 2013 report, Future Air Quality in Victoria, details that PM2.5 and ozone are the only pollutants expected to breach current air quality standards in 2030. These pollutants have negative effects on the environment, contribute to poor health and reduce the liveability of urban environments.

A 2014 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report found that in 2005 Australia experienced 882 deaths related to air pollution. This increased by 69 per cent to 1 483 deaths in 2010. In comparison, 20 of the 34 OECD countries—including the United Kingdom, United States and Germany—experienced a decline in their pollution-related deaths due to stricter vehicle emissions standards over the same time period.

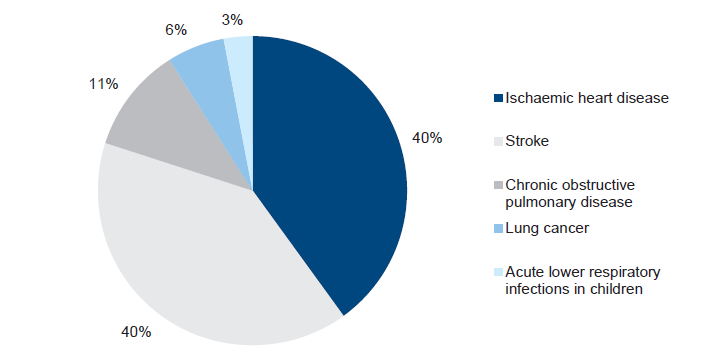

The report estimated the economic cost of these pollution-related deaths in Australia at approximately $5.8 billion in 2010 and that 50 per cent of this cost can be attributed to air pollution caused by road transport. In particular, a contributing factor is an increase in the use of diesel vehicles, which emit fewer greenhouse gases but higher levels of particulate matter. Small particulate matter can negatively affect respiratory and cardiovascular health and lead to death. Figure 1C shows the breakdown of causes of deaths related to air pollution worldwide.

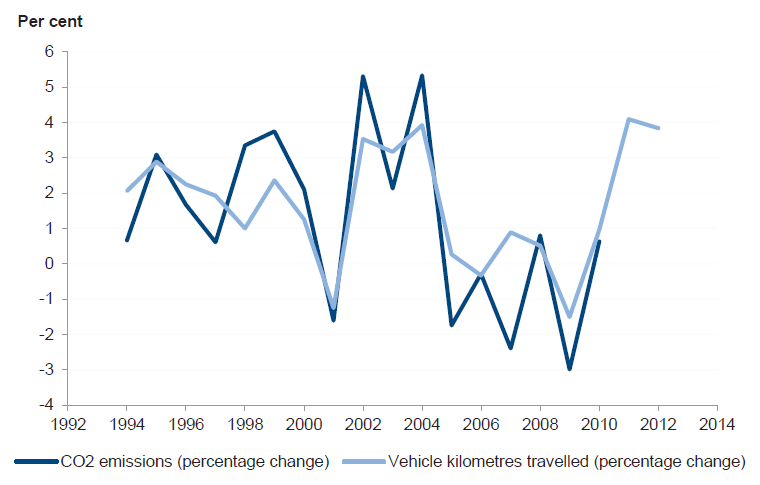

Figure 1C Deaths caused by outdoor air pollution—breakdown by disease

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development,The Cost of Air Pollution: Health Impacts of Road Transport, 2014.

Nevertheless, the EPA's 2013 regulatory impact statement on vehicle emissions regulations reports that exhaust emissions from motor vehicles have decreased substantially over the 10 years from 2001 to 2011, with nitrogen oxide decreasing by 51 per cent, hydrocarbons by 47 per cent and PM10 by 29 per cent. These are expected to further decrease primarily due to improved design standards and the progressive replacement of older vehicles with new ones. However, total emissions from these vehicles will remain significant, particularly as the number of motor vehicles in Victoria is expected to increase from 4 million to over 5 million in the next 10 years. According to BITRE's 2012 Research Report 127—Traffic Growth in Australia, total vehicle kilometres travelled (VKT) is also expected to increase by 2.7 per cent per year until 2020.

Noise

As Melbourne continues to grow, transportation noise will become an increasing source of community concern, particularly in residential areas. The ill effects of high noise levels include physical and psychological health problems, sleep disruption and disturbance to activities such as personal communication and learning.

1.2 Snapshot of the Victorian transport system

A heavy reliance on cars

Victorian passenger traffic is dominated by road transport—particularly passenger cars. In 2011, the former Department of Transport estimated that travel by car accounts for around 77 per cent of all weekday trips, increasing to 81 per cent on the weekends.

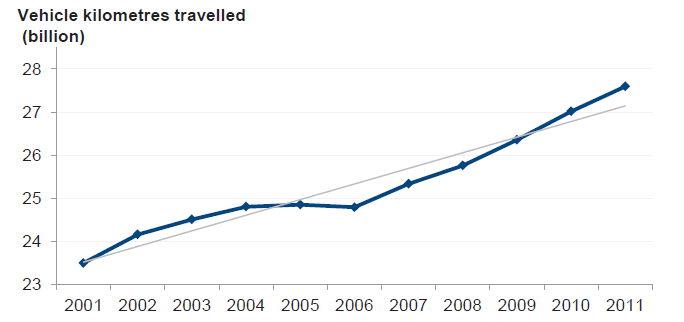

Figure 1D indicates that road use has shown strong growth over the past decade, with the total VKT travelled in Melbourne rising 15.4 per cent from 2001 to 2011. Growth has been particularly strong since 2006.

Figure 1D

Total vehicle kilometres travelled in metropolitan Melbourne—arterial roads and freeways

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from VicRoads Traffic Monitor 2011–2012, July 2013.

VicRoads divides Melbourne into three zones for the purposes of reporting VKT. Its data shows that most of the growth in car use occurred in Melbourne's outer metropolitan zone. This zone includes all the growth area councils apart from Mitchell. This trend reflects the emissions footprint shown in Figure 1B.

It also reflects the findings from our 2013 report on Developing Transport Infrastructure and Services for Population Growth Areas. Specifically, this audit found inadequate transport services and a significant backlog of required public transport in growth areas which have substantially fewer, less frequent and less direct public transport services compared to the rest of Melbourne.

Trends in public transport, walking and cycling

In Melbourne, public transport currently accounts for 8 per cent of total trips, walking 12 per cent, and cycling 2 per cent.

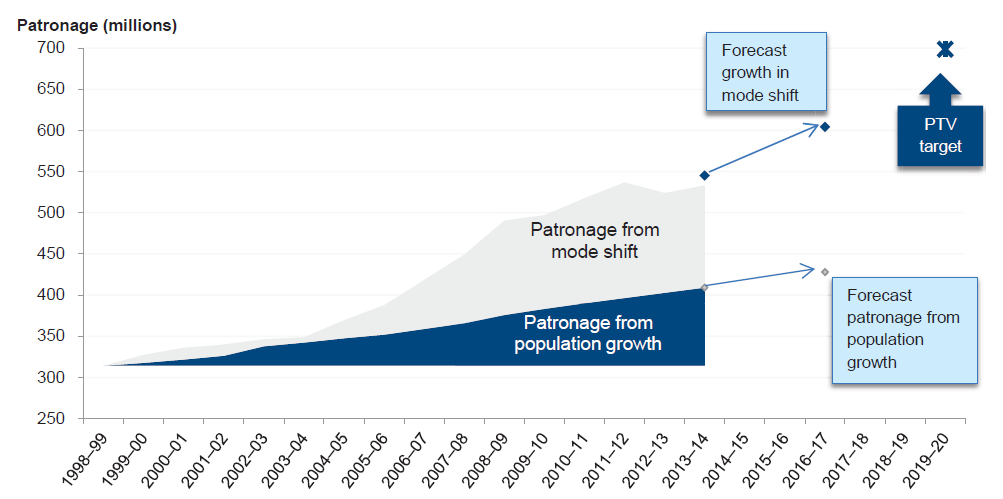

Population growth is a significant driving factor in past and projected increases in public transport patronage. Since 2005, all forms of public transport have had increased usage—with train patronage increasing by 44 per cent, trams by 22 per cent and buses by 34 per cent. Public transport patronage is similarly expected to double over the next 15 years.

The number of people who cycle as a means of transport has grown steadily over the past 10 years, with trips to work by bike growing at 5 per cent each year between 2001 and 2011. The incidence of walking has also increased by 4.7 per between 2001 and 2006. As these modes are the most environmentally friendly, walking and cycling will help to further reduce emissions from the transport sector.

The growing freight task

The growing Victorian economy is increasing demand for freight transport. In 2012, the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure (DTPLI) estimated that the number of shipping containers moving through the ports of Melbourne and Hastings combined is expected to triple by 2035. Most of the metropolitan freight task is carried on road.

VicRoads estimates that truck volumes have been increasing steadily since 2001 at an average of 2.2 per cent per year. Currently, there are over 500 000 commercial vehicles on Melbourne's roads and this is expected to more than double within the next 20 to 30 years.

Of all Australian states, Victoria showed the smallest growth in rail freight between 1961 and 2001—increasing by an average of 1.6 per cent per year. DTPLI estimates that rail freight currently makes up only 1 per cent of Melbourne's freight task and only 3 per cent of Victoria's overall land freight by tonnage.

1.3 Options for reducing transport emissions

The 2008 East-West Link needs assessment study, commissioned by the former Department of Transport, identified various initiatives designed to reduce transport emissions.

These initiatives fall within three general areas of operations—reducing the amount of transport required to meet society's needs, reducing the reliance on cars by promoting more non-vehicular travel, and improving vehicle technology and fuel efficiency. In addition, there are opportunities to improve the environmental impact of infrastructure construction and operations.

1.3.1 Reducing the demand for travel

The principal measures available to reduce travel demand involve encouraging different patterns of land use and persuading people to change their personal travel behaviour.

Land-use patterns

A city's urban form influences the amount of travel required, with residents of low density areas, such as in the outer suburbs of Melbourne, tending to travel more to reach jobs, activities and services.

Therefore, policies that encourage different patterns of land-use development, with a focus on higher density development, can contribute to reducing transport demand.

Changing behaviour

Increasing environmental awareness may help to change travel behaviour. However, to date Australians have shown little inclination to purchase fewer cars, or more environmentally friendly cars.

Australian Bureau of Statistics information demonstrates that, of the 1.7 million households that purchased a motor vehicle in Australia in the 12 months prior to March 2012, only 7 per cent stated that environmental impact was a strong influence when choosing which one to buy. The four main deciding factors were purchase price, fuel economy and running costs, size of vehicle, and type of vehicle.

Other potential strategies involve persuading people to change their personal travel behaviour by reconsidering their need to travel, or to take public or active transport. In 2011, the former Department of Transport identified that there was potential to change the travel habits of Melbournians by targeting:

- short trips—encouraging more people to walk or cycle instead of drive

- trips to school—increasing the share of trips being made by walking, cycling or public transport

- single occupant car trips—increasing car occupancy

- peak period trips—encouraging travel outside of peak periods or the use of public transport for those trips.

However, Victoria does not have a strong track record in effectively influencing travel behaviour. Our recent 2013 audit, Managing Traffic Congestion, found:

'While some limited demand management initiatives have been explored and implemented in recent years, such as the congestion levy, carpooling and travel planning programs, they have been neither comprehensive nor sufficient to materially impact demand for road use and related congestion.'

1.3.2 Increasing the use of non-vehicular modes

Passenger and freight transport continues to rely on motor vehicles, which produce the most greenhouse gas and other emissions. Promoting other, more environmentally friendly transport modes is a key way to reduce these environmental impacts.

Boosting public transport and rail freight

Increasing the availability of public transport by improving related services and expanding the reach of public transport, especially in the outer suburbs, will reduce people's car dependency, help to reduce congestion on roads and lower greenhouse gas and other emissions.

Further, greater public transport patronage will also help to improve its per passenger kilometre emissions, as trains and trams currently rely on brown coal and therefore have a high greenhouse gas intensity. In the future, as improvements in the stationary energy sector occur, the benefits will have a flow-on effect to public transport and improve its carbon dioxide emissions performance.

Shifting freight from trucks to rail can similarly assist in reducing the number of truck movements and resulting emissions. According to the Energy Efficiency Exchange website—a joint states and Commonwealth initiative—when freight is carried by rail rather than road, it produces 75 per cent less emissions per tonne of freight. However, due to its inherent limitation of fixed tracks and stations, shifting freight to rail would be most beneficial for long-distance freight trips.

VAGO has previously found a lack of investment in both of these areas, specifically:

- Our 2013 report on Developing Transport Infrastructure and Services for Population Growth Areas found a significant backlog of required public transport infrastructure in growth areas. It also found that these areas had fewer, less frequent and less direct public transport services compared to the rest of Melbourne.

- Our 2010 audit on the Management of the Freight Network similarly found that rail freight has been stagnant or declining because the lack of investment and past institutional arrangements have hampered growth.

Encouraging walking and cycling

The promotion of walking and cycling, especially for short trips, can further help to reduce reliance on vehicles. In metropolitan Melbourne, over 40 per cent of trips are less than two kilometres in length and almost 65 per cent are less than five kilometres. This suggests that there is room to encourage a shift to active transport which has both environmental and health benefits.

1.3.3 Leveraging new technologies

Despite improvements in public transport mode share, motor vehicle use in Victoria is expected to remain high, making it important to leverage improvements in vehicle and emission technologies.

Over the past two decades, significant advances have been made in fuel efficiencies and cars with new types of engines, such as those that run on electricity, that are designed to produce less greenhouse gas and other emissions.

However, in Victoria, the ability of new technologies that utilise power from the electricity grid to impact on greenhouse gas emissions is limited because electricity is sourced from brown coal. If electric vehicles were powered by renewable energy they could provide a low emission transport alternative.

1.3.4 Reducing emissions from transport infrastructure

Transport infrastructure can be made more environmentally sustainable during both construction and operations. In construction, recycled resources can be used and leftover construction materials can be recycled at the end of the process. In operations, energy efficient technology can be used to reduce energy consumption—for example, in street lighting and traffic lights.

1.4 Managing environmental impacts within the broader transport system

When managing the transport system, agencies are required to implement a range of legislative and policy objectives. These objectives must be balanced with any goal to manage the environmental impacts of transport.

The following sections summarise the legislative objectives for the transport system and provide an overview of agency roles and responsibilities.

1.4.1 Transport Integration Act 2010

The Transport Integration Act 2010 (the Act) came into effect in mid-2010 and requires that all decisions affecting the transport system be made within the same integrated decision-making framework and support the same transport system objectives.

Figure 1E summarises the government's vision, objectives and decision-making principles for the transport system set out in the Act. It provides imperatives for transport agencies to actively contribute to environmental sustainability by considering the environmental impacts of the transport system.

Figure 1E

Transport Integration Act 2010—Vision, objectives, principles

|

Vision The Parliament recognises that Victorians want an integrated and sustainable transport system that contributes to an inclusive, prosperous and environmentally responsible state. Objectives The transport system should:

Decision-making principles Agencies should have regard to the following principles:

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Environmental sustainability objective

The Act's environmental sustainability objective is specifically relevant to this audit. It requires the transport system to actively contribute to:

- avoiding, minimising and offsetting harm to the local and global environment—including through transport-related emissions and pollutants

- promoting forms of transport, forms of energy and transport technologies which reduce the overall contribution of transport-related greenhouse gas emissions

- improving the environmental performance of all forms of transport and the forms of energy used in transport.

1.4.2 Agency roles and responsibilities

DTPLI

Under the Act, DTPLI is responsible for leading strategic policy, planning and improvements relating to the transport system to ensure that it is provided consistent with the vision statement and the transport system objectives. It is also required to:

- collect transport data and undertake research into the transport system to lead strategic policy development and improve the transport system

- collaborate with other agencies to ensure that policies and plans for an integrated and sustainable transport system are developed, aligned and implemented.

- develop strategies, plans, standards, performance indicators, programs and projects relating to the transport system and related matters.

It therefore has the key leadership and coordination role in planning for and managing the transport system in a way that addresses the land use, economic and social needs of Victorians, while protecting the environment.

VicRoads

VicRoads plans, develops and manages 22 000 kilometres of arterial roads across the state. Under the Act, VicRoads has to contribute to a sustainable state by managing the road system in a way that seeks to:

- increase the share of public transport, walking and cycling trips as a proportion of all trips in Victoria.

- minimise the adverse environmental impacts of the road system.

PTV

Public Transport Victoria (PTV) manages the state's train, tram and bus services. It has key goals under the Act to manage the public transport system in a way that supports a sustainable state by seeking to:

- increase the share of public transport trips as a proportion of all trips in Victoria, including as an alternative to car travel

- improve the environmental performance of the public transport system.

1.5 Audit objective and scope

The objective of the audit was to examine whether the:

- institutional arrangements support effective strategic planning and cross‑government coordination for managing the environmental impacts of transport

- key strategies and initiatives for managing the environmental impacts of transport have been effective.

The audit examined how well DTPLI is fulfilling its strategic leadership role and how well VicRoads and PTV are managing the environmental impacts of transport.

1.6 Audit method and cost

The audit was conducted in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The cost of the audit was $310 000.

1.7 Structure of the report

Part 2 examines whether statewide strategic planning and governance arrangements adequately support the achievement of the Act's environmental sustainability objective.

Part 3 assesses the adequacy of agency-level strategic planning, governance and reporting arrangements for managing the environmental impacts of transport.

Part 4 examines the impact of specific agency actions on minimising the environmental impacts of transport.

2 Statewide strategic planning and reporting

At a glance

Background

Sound strategic planning, coordination and oversight of statewide actions to manage the environmental impacts of transport is vital to achieving the environmental sustainability objective of the Transport Integration Act 2010 (the Act).

Conclusion

The Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure (DTPLI) did not adequately address the Act's objective of minimising the environmental impacts of transport when developing the strategic framework for statewide transport and land‑use planning.

Findings

- DTPLI did not provide advice to the government regarding the environmental impacts of the transport system when developing Plan Melbourne, Victoria—The Freight State and regional growth plans.

- The lack of clear statewide environmental goals, including related performance measures and agency targets, means the current strategic framework is largely aspirational, and unlikely to be effective in minimising the environmental impacts of the transport system.

Recommendations

That the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure, in consultation with other transport agencies:

- develops a statewide strategy that sets out clear statewide objectives, targets and performance measures to address the environmental impacts of the transport system

- reviews its governance arrangements and establishes mechanisms to monitor and coordinate related agency actions

- establishes arrangements to measure and report on the performance of the transport system and related agencies in meeting the environmental sustainability objective of the Act.

2.1 Introduction

Sound strategic planning, coordination, and oversight of statewide actions to manage the environmental impacts of transport is vital to achieve the environmental sustainability objective of the transport system. The Transport Integration Act 2010 (the Act) requires the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure (DTPLI) to develop the strategic planning framework within which transport bodies are to operate.

To be effective, strategic planning needs to be clear about what it intends to achieve and provide direction to agencies for focused and coordinated action. It should therefore clarify agency responsibilities and accountabilities through explicit statewide objectives, targets and associated performance measures.

Sound governance arrangements reinforce these accountabilities and assure effective implementation of initiatives across agencies.

This Part of the report examines whether the statewide strategic planning and governance arrangements developed by DTPLI for managing the environmental impacts of transport are effective.

2.2 Conclusion

DTPLI did not sufficiently consider the need to minimise the environmental impacts of transport in developing the state's strategic transport and land-use planning framework (the strategic framework), which consists of:

- Plan Melbourne

- the state's freight strategy, Victoria—The Freight State (VTFS)

- the state's eight regional growth plans (RGP).

DTPLI also did not propose any defined outcomes for transport agencies to minimise the environmental impacts of transport and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, other emissions and traffic noise.

The absence of clear statewide goals in this area, including related agency performance measures and targets, means the strategic framework DTPLI proposed is largely aspirational and unlikely to be effective in minimising the environmental impacts of the transport system. The lack of clear goals also significantly impedes DTPLI's capacity to effectively oversee, assess and transparently report on the outcomes of related initiatives across the portfolio.

DTPLI is developing a new monitoring and reporting framework to measure outcomes against the Act's objectives. While this has potential to assist with evaluating the environmental impacts of initiatives, the framework is at a very early stage and thus its comprehensiveness and effectiveness cannot yet be assessed.

2.3 Statewide strategic planning

2.3.1 Historic focus on the environmental impacts of transport in statewide strategic planning

The need to address the environmental impacts of transport has featured prominently in statewide strategic land-use and transport plans developed since 2002. Related actions and initiatives are summarised in Figure 2A.

Figure 2A

Strategic planning to manage the environmental impacts of transport

Policy document |

Key objectives, actions and strategies for coordinating public transport |

|---|---|

Melbourne 2030—Planning for sustainable growth (2002) |

Aimed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, apply stricter controls on motor vehicle emissions and update standards and procedures for reducing transport noise. Also aimed to increase public transport's share of motorised trips within Melbourne to 20 per cent by 2020 and prioritise walking and cycling and promote sustainable personal transport options. |

Linking Melbourne—Metropolitan Transport Plan (2004) |

Aimed to manage the environmental impacts of freight and light commercial vehicles, including emissions and noise. |

Meeting Our Transport Challenges—Connecting Victorian Communities (2006) |

Aimed to promote sustainable travel to reduce the reliance on cars, including improve metropolitan train and tram and regional train services. |

Freight Futures: Victorian Freight Network Strategy—for a more prosperous and liveable Victoria (2008) |

Aimed to reduce engine noise and reduce greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption by consolidating and co‑locating freight precincts with related activities to reduce distances. |

Investing in Transport—East West Link Needs Assessment (April 2008) |

Highlighted the challenge to the state posed by climate change and the need to manage greenhouse gas and other air pollution from transport in Victoria. Proposed key policy responses, including reducing travel demand through land-use planning and changing people's behaviour, boosting public transport mode share and promoting improved vehicle technologies. |

Melbourne 2030 Audit (May 2008) |

Recommended setting targets and implementing programs for reducing car use to complement the state's mode share target and to establish benchmarks and targets for reducing greenhouse emissions. |

Planning for All of Melbourne (May 2008)—State's response to Melbourne 2030 Audit |

Included activities to help Victoria meet its 20 per cent by 2020 greenhouse gas reductions target, develop a Victorian transport energy strategy, and facilitate investment in renewable energy infrastructure. |

Victorian Transport Plan (2008) |

Continued the focus on 'lowering our carbon footprint from transport' and included actions to reduce the need to travel, use less polluting forms of transport more often and improve environmental performance. |

Source:Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Our 2013 audit, Developing Transport Infrastructure and Services for Population Growth Areas, noted the lack of continuity in Melbourne's succession of previous land‑use and transport plans that have often been superseded before they are implemented. It also noted that this has contributed to the failure of previous statewide actions.

Nevertheless, an important feature and strength of the previous statewide strategies was the capacity they provided to clearly align actions with, and assess related progress against, the following measurable and complementary targets:

- increase public transport's share of motorised trips within Melbourne to 20 per cent by 2020

- reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 20 per cent by 2020 from 2000 levels.

The discontinuation and absence of similar targets since 2012 has significantly reduced accountability for performance.

Without defining clear outcomes and related targets which set the foundation for effective implementation and monitoring, the current strategic framework is likely to repeat the patterns of the past.

2.3.2 The strategic framework developed by DTPLI

The Act requires DTPLI to develop a transport plan that establishes the overarching planning framework within which other transport bodies are to operate and against which to align its own plans. The plan must be prepared having regard to the vision statement, transport system objectives and decision making principles of the Act.

DTPLI advised that Plan Melbourne, VTFS and the RGPs form the statewide strategic transport and land-use planning framework and fulfil the Act's requirement to develop a transport plan. It also advised that this framework contains 'the mix of integrated actions considered best able to achieve the desired outcomes, including environmental outcomes'. However, it is not clear what environmental outcomes DTPLI is seeking to achieve as they have not been clearly defined.

During the framework's development DTPLI did not provide the government with any advice about how proposed strategies would address the environmental impact of the transport system. DTPLI's advice also omitted critical details on statewide objectives, targets and performance measures for minimising the environmental impacts of transport, including for reducing greenhouse gases and other emissions. Therefore, DTPLI's claim that it contains the 'best mix of actions' to achieve environmental outcomes cannot be verified.

This means the framework developed and proposed by DTPLI did not provide a clear basis for transport agencies to align their policies and actions. It also significantly impedes DTPLI's ability to measure the effectiveness of agencies' progress against statewide objectives or to assess whether the aims of the strategic framework and desired environmental outcomes have been achieved.

DTPLI advised that this framework has since been adopted by the government.

The importance of defining expected outcomes and targets

The strategic framework acknowledges the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, other motor vehicle emissions and traffic noise. However, DTPLI's failure to develop clearly defined environmental objectives, targets and goals for the framework means that:

- its intent with regard to the environmental sustainability objective is unclear as it does not define how the transport system will contribute to its achievement

- it does not provide a clear basis for transport agencies to align their policies and actions, and for assuring that they are sufficient for achieving the Act's environmental sustainability objectives

- there is no way to measure the effectiveness of agencies' progress against statewide objectives, or whether the aims of the strategic framework and desired environmental outcomes have been achieved.

During the audit, DTPLI asserted that targets are a matter for government and are not necessary for measuring progress.

However, the establishment of clear targets and benchmarks for assessing the achievement of objectives is a fundamental and widely accepted practice of good governance and public administration. While the government has the prerogative to adopt or reject proposed targets, this does not negate DTPLI's obligation to provide frank and fearless advice to the government on the merits of such targets. Neither does it preclude DTPLI from establishing such standards internally, including performance monitoring arrangements to assess the impacts of its initiatives and to transparently demonstrate its environmental performance to the government.

South Australia's approach to setting statewide targets

South Australia's strategic planning highlights a good practice approach to setting clear and measurable, interrelated targets at the statewide level and agency-level.

The recent 30-Year Plan for Greater Adelaide has adopted various measurable targets around environmental objectives that are expected to substantially contribute to overall statewide targets set under South Australia's Strategic Plan (SASP). Figure 2B provides an overview of these relevant targets.

Figure 2B

Contribution and linkages between Greater Adelaide targets with

South Australian statewide targets

Environmental objective |

Target in plan for Greater Adelaide |

Relevant statewide target in SASP |

|---|---|---|

Greater urban density and transit oriented development |

Seventy per cent of metropolitan Adelaide's new housing will be in-fill development in established areas and 60 per cent of new housing will be within 800 metres of current or extended transit corridors. |

Reduce South Australia's ecological footprint by 30 per cent by 2050. |

Reduce greenhouse gas emissions |

Implementing the plan over 30 years will result in a 20 per cent reduction in South Australia's overall greenhouse gas emissions. |

Reduce South Australia's greenhouse gas emissions by 60 per cent of 1990 levels by 2050. |

Increase use of public transport and reduce reliance on cars |

Public transport use to grow faster than private car use per head of population over five‑yearly intervals. Achieve a per capita reduction in vehicle kilometres travelled over five-yearly intervals. |

Increase the use of public transport to 10 per cent of metropolitan weekday passenger vehicle kilometres travelled by 2018. |

Increase renewable energy |

A net increase in renewable energy as a percentage of total energy generation. |

Twenty per cent of the state's electricity generation to come from renewable energy by 2014 (achieved) and 33 per cent renewable energy by 2020. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from South Australia's Strategic Plan and the 30-Year Plan for Greater Adelaide.

2.3.3 Environment-related content in Plan Melbourne and related advice to government

Plan Melbourne is split up into directions, initiatives, and short-, medium-, and long‑term actions. The actions are the deliverables of the plan, and their implementation is assigned to relevant agencies or the Metropolitan Planning Authority.

Overall assessment of the advice to government during Plan Melbourne's development

Our audit reviewed all briefings to portfolio ministers and the government during Plan Melbourne's development. These documents show that DTPLI did not provide any specific advice regarding the environmental impacts of the transport system during this time.

The Ministerial Advisory Council (MAC), initially tasked by the Minister for Planning to direct the development of the strategy, proposed a greater number of more detailed actions that supported the achievement of the Act's environmental sustainability objective. These included explicit environment-related actions to:

- establish a target to deliver at least 70 per cent of new dwellings in established areas

- accurately measure and significantly reduce Melbourne's emissions to at least 5 per cent below 2000 levels by 2020 and to 50 per cent of 2000 levels by 2050.

The MAC indicated that particular changes in the transport sector will need to occur for Melbourne to achieve these greenhouse gas reduction targets. These included:

- improving the emissions performance of all transport modes

- reducing reliance on cars and ensuring that the average length of motor vehicle trips does not increase

- doubling the proportion of personal trips made on foot, by bike or public transport

- introducing renewable energy sources for public transport.

These targets and proposals were not adopted in the final plan and DTPLI did not advise the government of their merits or otherwise. Consequently, DTPLI did not adequately consider the need to minimise the environmental impacts of transport when developing Plan Melbourne.

The following sections summarise the environment-related content of Plan Melbourne and related departmental advice to government.

Encouraging efficient land use

Plan Melbourne acknowledges that a city's level of greenhouse gas emissions is partly a function of its urban structure.

It seeks to align housing, jobs and public transport, as it recognises this will have environmental and economic benefits by reducing trip lengths, travel times and costs, thereby leading to a more energy efficient city.

Key directions and initiatives within the plan focused on influencing Melbourne's future shape are based on:

- an expanded central city and major population growth in defined urban renewal sites such as Fishermans Bend, E-Gate and Arden-Macaulay

- a polynodal city with six National Employment Clusters that aim to establish a high concentration of jobs and public transport, and 11 metropolitan activity centres designed to enable people to travel shorter distances

- the concept of 20-minute neighbourhoods, whereby people have access to local services and facilities within 20 minutes of home by walking, cycling or public transport, designed to reduce trip times across Melbourne and in growth areas

- fixing the urban growth boundary, in recognition that Melbourne's outward growth has now stretched to the point where it is impeding access to jobs, goods and services.

Related advice to government

DTPLI undertook urban form modelling in its development of directions and initiatives for Plan Melbourne to encourage efficient land use. This modelling compared the performance of different potential city shapes in promoting improved urban outcomes by 2046 and guided DTPLI's integrated land-use and transport planning. It showed that a smaller number of larger activity centres with contained fringe growth was more effective than a larger number of smaller centres in:

- producing fewer car trips to jobs by increasing the use of public transport and walking and cycling

- promoting better job density and access to employment

- reducing congestion across the wider road network for both freight and passenger traffic

- increasing carbon efficiency by providing the best access to activity centres while also producing the least amount of transport-related greenhouse gas emissions.

However, DTPLI did not advise government to set clear targets for achieving environmental outcomes in relation to land-use actions within the plan.

As a result, while some city shaping actions developed by DTPLI will have an indirect effect on the environment, these do not appear to be driven by, or seek to achieve, explicitly defined environmental outcomes. For example:

- the proposed action to accommodate the majority of new dwellings in established areas within walking distance of public transport has no explicit link to defined environmental outcomes, nor does it specify related targets for reduced trip length and time and the number of new dwellings to be located in established areas

- while the 20-minute neighbourhood concept can lead to a reduction in emissions, the absence of related performance measures and targets means this cannot be assessed.

The urban modelling DTPLI conducted during the development of Plan Melbourne quantified expected improvements, including the potential reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from the various urban structures. This could have provided the basis for DTPLI defining expected and measurable outcomes that would allow the evaluation of achievements, however, it did not do this.

Boosting non-vehicular modes

Plan Melbourne estimates that, as Melbourne grows from 4.3 million people to about 7.7 million by 2051, the city will need to accommodate an additional 10.7 million trips per day and increase its reliance on public transport. Although not explicit in the plan, DTPLI advised during the audit that mode shift will comprise a substantial proportion of this future patronage growth.

Encouraging mode-shift from cars to public transport will contribute to more effectively avoiding, minimising or offsetting harm to the environment. However, DTPLI has not established what proportion of future public transport trips by 2051 will be due to natural population growth and therefore how many of those trips it will have to divert from cars. DTPLI needs to establish this figure so that it can properly target and understand the mode-shift task.

Plan Melbourne identifies the following key infrastructure projects, which were funded under the 2014–15 State Budget:

- $8.5 billion to $11 billion for Melbourne Rail Link

- $8 billion to $10 billion for the Western section of the East-West Link

- $2 billion to $2.5 billion for upgrade of the Cranbourne-Pakenham Line

- $850 million for the CityLink-Tulla Widening in partnership with the private sector

- $685 million to remove level crossings.

During the audit, DTPLI advised that the investments announced in Plan Melbourne will be a critical contributor to increasing public transport patronage. However, this cannot be verified in the absence of clearly defined objectives, targets and auditable performance information that demonstrates how these projects will contribute to increasing patronage of the public transport system.

Related advice to government

DTPLI did not provide any specific advice to government on the environmental benefits of boosting non-vehicular modes nor on the merits of setting clearly defined targets for public transport patronage or mode-shift from cars.

Promoting new vehicle technologies

Plan Melbourne contains no directions or actions to promote improved vehicle technologies, such as electric or hybrid vehicles.

Related advice to government

In early planning work on Plan Melbourne, new vehicle technologies were identified as an important factor in managing greenhouse gases and other emissions in the context of Melbourne's growing population. There is no evidence of any departmental advice to government on the merits or otherwise of pursuing initiatives that relate to new vehicle technologies.

Improving noise and air quality

Plan Melbourne recognises the high-level need to reduce the environmental and health impacts of air pollution and noise from motor vehicles and freight.

However, the specified action aimed at improving noise and air quality does not seek to reduce the source of that air pollution or noise. Instead it focuses on ensuring that sensitive land uses are not located or designed in a way that would expose people to unacceptable amenity impacts.

Related advice to government

DTPLI did not provide advice to the government on the merits of addressing noise and air quality through Plan Melbourne.

Promoting energy efficiency and the use of renewable energy

Plan Melbourne does not include information, explicit targets or actions for:

- reducing the energy consumption of public transport and roadside infrastructure

- promoting the use of renewable energy

- improving fuel efficiency.

Related advice to government

There is no evidence of departmental advice to the government explaining these potential policy responses, or justifying their exclusion from Plan Melbourne.

2.3.4 Victoria—The Freight State

The Victorian freight and logistics plan recognises the need to address the environmental impacts of freight transport. However, DTPLI did not advise government of the merits of targets to monitor and evaluate the extent to which implemented initiatives contribute to achieving the Act's environmental sustainability objective.

Targets for managing freight

A key principle of VTFS includes 'minimising the impacts of freight and logistics activity on the environment'. However, DTPLI has not yet developed measures or targets designed to drive the achievement of specific environmental outcomes or that allow meaningful evaluation of related actions.

VTFS recognises that rail freight has less impact on the environment than road freight and seeks to promote a shift to rail freight. However, DTPLI has not defined targets that clarify either the extent of rail freight mode share desired, or the nature of the environmental benefits sought.

Similarly, other actions that have potentially beneficial impacts on the environment which DTPLI has no defined outcomes or targets for are:

- promoting the use of more efficient higher productivity freight vehicles

- encouraging fleet operators to use new technologies to manage noise, emissions and improve road efficiency.

The absence of related performance indicators and targets for these initiatives means that DTPLI's effectiveness in improving the environmental performance of freight transport cannot be meaningfully evaluated.

There is also no evidence that DTPLI has proposed actions and related targets to reduce the energy consumption of freight infrastructure and transport, or which promote the use of renewable energy sources.

2.3.5 Regional growth plans

The state's eight RGPs do not specify how they will contribute to managing the environmental impact of the transport system, including related transport emissions or noise. While all RGPs mention the need for improved public transport services—including walking and cycling—DTPLI has not established an explicit link between these actions and measurable environmental benefits. None of the RGPs currently set targets that would allow meaningful monitoring and evaluation of how planned actions contribute to the Act's environmental sustainability objective.

DTPLI's responsibility for 'leading strategic policy' means it needs to ensure that these plans align with and support the achievement of broader statewide strategic priorities, including those relating to the environment. Currently this is not the case.

Only the Hume RGP mentions improving transport as an option for minimising environmental impacts, but it does not go into further detail. Similarly, while both Hume's and Loddon Mallee's plans recognise the need for more sustainable vehicle technologies, DTPLI has not outlined any actions it will take to encourage these technologies or to measure their environmental impact.

2.4 Statewide governance and monitoring arrangements

DTPLI has established arrangements to support cross-government coordination and implementation of transport system projects and priorities. However, these do not support the coordinated and effective implementation of actions for addressing the environmental sustainability objective of the Act.

DTPLI advised that its primary arrangement for supporting effective cross-government coordination across the portfolio is the Transport Planning Group (TPG) which was formed in June 2012 and brings together executives from DTPLI, VicRoads and Public Transport Victoria. The purpose of this group is to provide ongoing advice on high-level strategic issues that impact the portfolio, integrate transport portfolio strategies and resolve differences between agencies. It is evident that TPG meetings consider progress of major strategic initiatives.

However, DTPLI confirmed that the TPG does not actively monitor progress against the transport system objectives. There is therefore no governance body across the portfolio that oversees and actively monitors progress in achieving the environmental sustainability objective of the Act.

An explicit focus of the TPG on this is warranted given that it is a legislated objective of the transport system.

2.4.1 DTPLI's approach to monitoring and measuring performance

DTPLI has a Transport Outcomes Framework (TOF) to support and monitor the impact of transport system actions in achieving the Act's objectives. DTPLI advised that the TOF has been used to support the development of business cases for transport projects and that it is currently being revised to better support the implementation of Plan Melbourne and VTFS.

Similar performance monitoring systems are expected to be developed for the RGPs. However, until these monitoring frameworks are completed we are unable to assess their effectiveness in monitoring the achievement of the Act's environmental sustainability objective.

Transport Outcomes Framework

The TOF outlines seven broad portfolio initiatives linked with reducing the impact of the transport system on the environment. These include:

- reducing the reliance on private motor cars