Recycling Resources from Waste

Audit snapshot

Is Victoria on track to achieve its recycling targets?

Why we did this audit

Victoria produces over 14 million tonnes of waste each year. Recycling waste is important for Victoria’s environment and saves valuable resources from landfill.

Before 2018, Victoria exported large amounts of paper, plastics, cardboard and other materials to China, Malaysia and other countries for recycling. But when China set strict rules on the waste it accepts, it disrupted global recycling markets and led Australia to phase out waste exports.

In response, in 2020 the Victorian Government introduced Recycling Victoria: A new economy (the circular economy policy). This 10-year policy and action plan aims to reduce waste, increase recycling and transition Victoria to a circular economy.

It outlines 4 targets to measure progress towards this goal. Three of these targets are about recycling. We did this audit to see if the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (the department) and other agencies responsible for implementing the plan are meeting those 3 targets.

Key background information

Source: VAGO.

What we concluded

The department and other audited agencies have made considerable progress to build Victoria’s capacity to recover and reprocess waste. However, they are only on track to deliver one of the government's 3 recycling and waste diversion targets:

- The agencies are on track to deliver the target for every Victorian household to have access to a food organics and garden organics waste service by 2030. This progress has helped to increase household organic waste recovery.

- They are not on track to deliver the target to divert 80 per cent of waste going to landfill by 2030. The proportion of waste going to landfill has not changed in the 4 years since the circular economy policy started.

- It is also not clear if the government is on track to halve the amount of organic material that goes to landfill. Although data shows much organic material is recovered from landfill, the department does not have accurate data to fully understand how much organic waste still goes to landfill.

The department needs to collect better data about waste flows, especially the types of waste in landfill. This will help it accurately measure its progress towards the recycling and waste diversion targets and will make its projections of future waste flows more reliable. These projections signal Victoria's future waste and recycling needs to the waste and recycling industry.

Video presentation

1. Our key findings

What we examined

Our audit followed one line of inquiry:

1. Are relevant agencies implementing the ‘recycle’ policy goal as intended?

To answer these questions, we examined the entities responsible for delivering the 'recycle’ programs from Recycling Victoria: A new economy (the circular economy policy) between 2020 and 2024:

- the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (the department), including Recycling Victoria, which is an area within the department

- the Environment Protection Authority Victoria (EPA)

- Sustainability Victoria

- the Victorian Infrastructure Delivery Authority.

Background information

Victoria produces over 14 million tonnes of waste each year. Recycling waste is important for Victoria’s environment and saves valuable resources from landfill.

From the 1990s, Victoria exported large amounts of material to countries such as China and Malaysia to be recycled. In 2017, Victoria sent approximately 1.27 million tonnes of paper, plastic and cardboard overseas each year, including 30 per cent of all recycling collected from households.

In 2018, China enforced strict contamination thresholds on the recyclable materials it accepts. This disrupted recycling markets worldwide, including in Victoria.

In response, the Australian Government passed the Recycling and Waste Reduction Act 2020 to phase out waste exports, including banning the export of waste-derived glass, paper, cardboard, plastic and tyres. This meant that states and territories, including Victoria, had to handle their own waste recovery and reprocessing, rather than exporting it.

In 2020 the Victorian Government introduced a 10-year policy and action plan for waste and recycling in Victoria – the circular economy policy. It outlined the pathway for Victoria to reduce waste, increase recycling and create more value from recovered resources.

Circular economy

In a circular economy, materials, energy and other resources are used productively for as long as possible to retain value, maximise productivity, minimise greenhouse gas emissions, and reduce waste and pollution.

Circular economy policy

The circular economy policy has 4 goals:

1. Make – design to last, repair and recycle

2. Use – use products to create more value

3. Recycle – recycle more resources

4. Manage – reduce harm from waste and pollution.

This audit focused on goal 3 – recycle.

This goal includes 5 key commitments that sit above 11 actions. The agencies we audited are delivering 14 programs to achieve these actions (see Appendix D, Figure D1).

Circular economy policy targets

To measure its progress towards the circular economy policy’s goals, the department set 4 targets:

| Target ... | is to ... | by ... | with an interim target of ... |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | divert 80 per cent of waste from landfill | 2030 | 72 per cent by 2025. |

| 2 | cut total waste generation per person by 15 per cent | 2030 | - |

| 3 | halve the volume of organic material going to landfill | 2030 | 20 per cent by 2025. |

| 4 | provide every Victorian household with access to food organics and garden organics waste (organic waste) recycling services or local composting | 2030 | - |

We focused on targets 1, 3 and 4, which relate to the circular economy policy’s recycle goal.

Sources of waste we refer to in this report

| Waste source | Formal term | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Household waste | Municipal solid waste | Waste collected by councils, mostly from households. It includes organic materials, recyclables including paper, cardboard, plastic, metal and glass, along with general waste material |

| Building waste | Construction and demolition waste | Waste from the construction, renovation, repair, and demolition of homes, buildings, and other projects. It includes materials such as timber, concrete, bricks, soil, asbestos and asphalt |

| Business waste | Commercial and industrial waste | Waste generated by businesses and institutions, including schools, restaurants, offices, retail and wholesale businesses and the manufacturing production industries |

What we found

This section focuses on our key findings, which fall into 3 areas:

1. Victoria is not on track to meet 2 of its 3 recycling and waste diversion targets.

2. Victoria’s recycling capacity has increased, but program extensions have slowed progress and there are gaps in mandatory reporting by some operators.

3. The data the department uses to track its progress and project future waste flows has gaps and is not all reliable, and it can do more to account for and communicate this.

The full list of our recommendations, including agency responses, is at the end of this section.

Consultation with agencies

When reaching our conclusions, we consulted with the audited agencies and considered their views.

You can read their full responses in Appendix A.

Key finding 1: Victoria is not on track to meet 2 of its 3 recycling and waste diversion targets

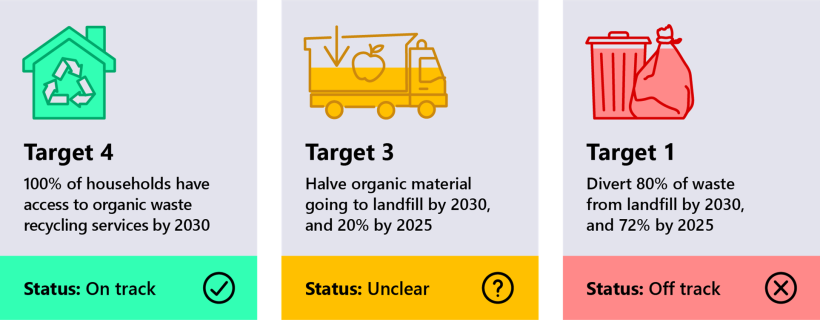

Figure 1 shows the 3 recycling and waste diversion targets in the circular economy policy related to the ‘recycle’ goal.

Figure 1: Circular economy policy recycle goal targets

Source: VAGO.

Household access to food organics and garden organics waste services

| Recycle goal target | Progress as of July 2024 | Status |

|---|---|---|

| To provide every Victorian household with access to food organics and garden organics waste services | 71 per cent of councils told the department that all households in their area have access to this service | On track |

The department is introducing regulations that will require all councils to provide an organic waste service by 1 July 2027. This means this target is likely on track and ahead of schedule.

Working well: Most councils provide a household food organics and garden organics waste service

More councils report that they provide a household organic waste service than before the circular economy policy.

As of July 2024, 56 of 79 councils said that they offer organic waste services, up from 17 councils in 2018–19.

Providing households with separate waste services should increase the volume of organic materials that can be recycled instead of going to landfill.

Reducing the volume of organic waste going to landfill

| Recycle goal target | Progress from 2018–19 to 2022–23 | Status |

|---|---|---|

Halve the volume of organic material going to landfill by 2030 and 20 per cent by 2025

|

| Unclear

|

Note: Data for 2023–24 is not yet available.

The department assumes that any recovered organic waste would have otherwise gone to landfill.

It does not track organic waste recovery directly. The latest information about the types of waste in Victorian landfill is from 2017–18. The department has not completed a landfill composition audit since then. It instead measures the volume of organic waste recovered as a proxy measure.

Proxy measure

A proxy measure is an indirect stand-in for something you want to understand but are not measuring directly.

Proxy measures take advantage of available data, but they can be inexact or unreliable.

This means the department cannot be confident about progress it has made because it has not measured the actual volume of organic waste going to landfill since 2018–19.

Ensuring Victorian households have access to organic waste recycling services will help the department achieve this target. But more organic waste also needs to be recovered from the business sector.

Diverting total waste from landfill

| Recycle goal target | Progress from 2018–19 to 2022–23 | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Divert 80 per cent of waste from landfill by 2030 and 72 per cent by 2025 | Waste diverted from landfill remained constant at around 69 per cent | Off track |

Note: Data for 2023–24 is not yet available.

This target matters because materials that go to landfill are not recycled and lose their value to the economy. This also means more materials need to be made to replace them, using more energy and resources and causing more emissions.

The reliability of the department’s underlying landfill data is uncertain (as discussed above). However, there is no evidence that the total waste diverted from landfill has changed since 2018–19.

This means the department is likely not on track to achieve its interim target to divert 72 per cent of waste from landfill by 2025.

If the department is to reach its 2030 target, it needs to work with the waste and recycling sector, households and other businesses to recover more waste. It especially needs to focus on recovering more from high-volume waste streams and those with low rates of recovery, such as organic waste from the business sector.

Rolling out household organic waste recycling services and building thermal-waste-to-energy facilities should help accelerate progress.

Waste to energy

Waste-to-energy processes recover energy from waste materials that are currently destined to go to landfill and cannot otherwise be recycled to produce heat, fuel or electricity.

Under a circular economy hierarchy legislated in Victoria, using waste that cannot be recycled to recover energy is better than disposing of it in landfill.

Addressing this finding

To address this finding we made one recommendation to the department and Sustainability Victoria about improving the recovery of high-volume waste streams that currently have a low recovery rate or little or no change since 2020.

Key finding 2: Victoria’s recycling capacity has increased, but program extensions have slowed progress and there are gaps in mandatory reporting by some operators

Victoria’s recycling capacity has increased

Agencies responsible for delivering the circular economy policy have successfully implemented 10 of 14 programs under the recycle goal. The remaining programs are in progress. Three are scheduled for completion in 2025 and one in 2027.

Working well: Victoria’s recycling capacity has improved

By fully implementing 10 programs on time and partially implementing 4, the government has made considerable progress to increasing Victoria’s recycling capacity since 2020.

This includes:

- introducing legislation to help regulate the waste and recycling industry – the Circular Economy (Waste Reduction and Recycling) Act 2021 (Circular Economy Act)

- investing in recycling programs and infrastructure

- using more recycled materials in state-funded projects.

Programs that are key to achieving targets have been delayed or extended

When the department planned for the circular economy policy it also planned the programs it would need to achieve the recycling and waste diversion targets.

Of the 14 programs in the circular economy policy, it estimated that 9 programs would make the biggest contributions to reaching the targets.

The department and other audited agencies have delivered most of the circular economy policy programs as intended, including 5 of the 9 key programs. They have completed the:

- landfill (waste) levy changes

- Recycled First Program and Policy

- Container Deposit Scheme

- Victorian waste to energy framework

- Victorian Recycling Infrastructure Plan.

However, the department and other audited agencies have not delivered 4 of the key programs according to their initial schedule (see appendix D, Figure D1). This may have slowed progress towards the targets and the circular economy policy’s goals.

| They have not completed the ... | which ... |

|---|---|

| Industry and Infrastructure Development package | will be completed in 2027. |

| Kerbside Reform | will be completed in 2027. |

| New Circular Economy Act, Regulations and Authority | will be completed in 2025. |

| Recycling Markets Acceleration Package | is partially complete and will be completed in 2025. |

Note: As the circular economy policy spans a 10-year period until 2030, some programs may continue beyond 2025. Expected completion and delays refer to the current program schedule. For example, the Kerbside Reform is a 7–10 year program, but its current schedule completion was initially expected by 2023.

Although the Industry and Infrastructure Development Package was not completed to the original schedule, Sustainability Victoria extended it by 3 years from 2024 to 2027 to leverage $15.6 million of Australian Government funding. This package is important for attracting investment in infrastructure to build Victoria’s recycling capacity, especially as the population grows and the amount of waste increases.

Recycling sector risk, consequence and contingency planning

Under the Circular Economy Act, the department has established a risk and contingency planning framework to help minimise and manage significant risks to the waste, recycling and resource recovery sector.

The department introduced the Circular Economy (Waste Reduction and Recycling) (Risk, Consequence and Contingency Plans and Other Matters) Regulations 2023 to enable the framework.

The regulations identify the waste, recycling and resource recovery services that are essential services and defines which providers of those services that, if disrupted, would seriously impact service continuity. These providers are known as responsible entities.

The Circular Economy Act requires:

- the department to publish an annual Circular Economy Risk, Consequence and Contingency Plan (circular economy risk plan)

- responsible entities to comply with the circular economy risk plan and report on their risk planning in an annual Responsible Entity Risk Consequence and Contingency Plan (responsible entity risk plan).

The Act and regulations outline the requirements relating to the preparation and content of the circular economy risk plan and responsible entity risk plans.

The department published the inaugural circular economy risk plan in May 2024. Responsible entities submitted their inaugural risk plans in September 2024. The department published guidelines to enable responsible entities to meet their mandatory obligations when preparing their risk plans.

Key issue: Responsible entities did not meet all mandatory reporting requirements in their risk plans

In its first year, the risk reporting from responsible entities did not include all mandatory information. For example, some responsible entities did not include:

- correct dates for when they identified risks

- risk monitoring or evaluation plans

- services they rely on (such as transport networks, third party providers or regulators).

When responsible entities omit mandatory information from their risk plans it makes it harder for the department to understand and manage risks to service continuity.

Addressing this finding

To address this finding we made one recommendation to the department about improving guidance to responsible entities to better enable them to provide all mandatory information in future responsible entity risk plans.

Key finding 3: The data the department uses to track its progress and project future waste flows has gaps and is not all reliable, and it can do more to account for and communicate this

Limitations with waste flow data and projections

The department uses data to measure and project waste flows that is not always complete or reliable. The limitations with current waste flow data include:

- using voluntary waste and recycling industry surveys about how much and what type of waste goes to landfill

- low response rates to industry surveys and incomplete responses

- basing landfill composition estimates on outdated landfill audit data from 2017–18

- not verifying council data about how many households have access to kerbside recycling services

- missing information on hidden waste streams, organic waste and certain types of soil.

The department uses this data to assess its progress towards the circular economy policy targets and project different waste streams out to 2053. It publishes these projections in its Victorian Recycling Infrastructure Plan and its waste projection model.

In the Victorian Recycling Infrastructure Plan the department’s projections also estimate potential gaps in Victoria’s capacity to meet future recycling needs. This helps inform the waste, recycling and resource recovery sector of future market opportunities and can inform the government where to invest.

Key issue: The department does not account for or communicate uncertainty in its waste projections due to data limitations

The department uses sound and well-documented methodologies to project waste flows and model future demand and capacity gaps. However, as some of the data the department uses is incomplete and/or unreliable, there may be considerable uncertainty around its projections.

The department did not demonstrate how it accounts for data limitations in its projections, nor does it communicate the potential uncertainty. This means that the waste, recycling and resource recovery sector, and government, could make investment decisions based on inaccurate data or an incomplete understanding of investment risk.

Addressing this finding

To address this finding we made one recommendation to the department about strengthening current methods for collecting and communicating waste flow data and projections.

See the next page for the complete list of our recommendations, including agency responses.

2. Our recommendations

We made 3 recommendations to address our findings. The Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action and Sustainability Victoria have accepted the recommendations.

| Agency response(s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finding: Victoria is not on track to meet its target of diverting 80 per cent of waste from landfill by 2030 | ||||

Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action and Sustainability Victoria

| 1

| Strengthen Victoria’s current waste collection and reprocessing system by identifying opportunities to:

| Accepted

| |

| Finding: There are gaps in reporting of risks to service continuity by responsible entities in the waste, recycling and resource recovery sector | ||||

Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action

| 2

| Where necessary, strengthen guidance and support to enable responsible entities to comply with the mandatory requirements.

| Accepted

| |

| Finding: Waste flow data and projections to inform circular economy policy implementation and the recycling sector are not always reliable | ||||

Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action

| 3

| Improve data quality and communication of waste flow data and projections by:

| Accepted

| |

3. Progress towards the recycling and waste diversion targets

Victoria is on track to ensure every household has access to a food organics and garden organics waste recycling service by 2030.

However, it is unclear if less organic waste is entering landfill and it is unlikely that 80 per cent of total waste will be diverted from landfill by 2030.

Covered in this section:

- Every Victorian household is on track to have access to a kerbside food organics and garden organics waste service by 2030

- The recovery of organic waste has improved but the volume entering landfill is unclear

- It is unlikely that 80 per cent of waste will be diverted from landfill by 2030

- There are opportunities to boost resource recovery from some waste streams and sectors

Victoria is on track to meet one of its 3 recycling and waste diversion targets

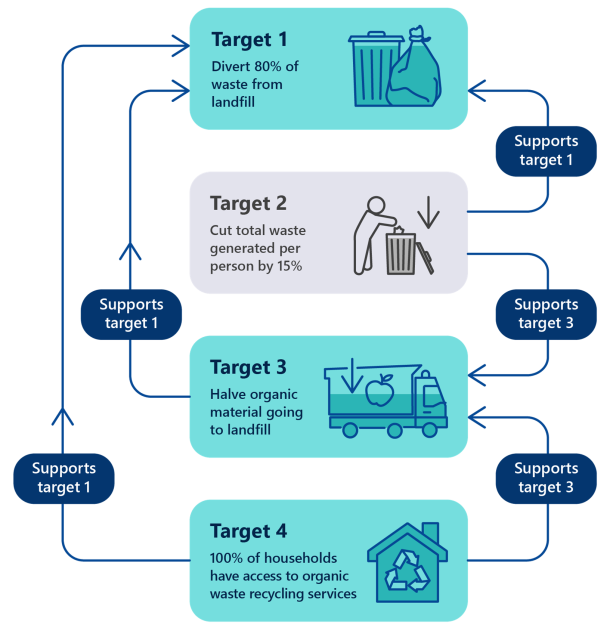

The relationship between recycling and waste diversion targets

Figure 2 shows how the circular economy policy targets are interrelated. This means that progress towards one of the recycling or waste diversion targets impacts progress towards the others.

Figure 2: Relationships between circular economy policy targets

Note: 3 targets related to the ‘recycle’ goal are highlighted.

Source: VAGO.

For example, Victorian households having access to an organic waste service (target 4) should reduce the volume of organic material going to landfill (target 3). In turn, this will increase the total volume of waste diverted from landfill (target 1).

The remaining circular economy policy target is to cut total waste generation by 15 per cent per person by 2030. This should also decrease the total volume of waste going to landfill. But the actions under the recycle goal do not influence target 2.

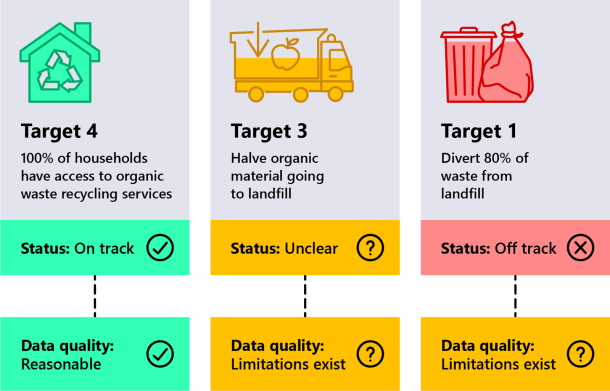

Progress against the targets

Figure 3 shows progress against each of the 3 recycle goal targets.

As of 2024, all Victorian households are likely on track to have access to organic waste recycling services by 2030.

But Victoria is unlikely to meet its interim target to divert 72 per cent of waste from landfill by 2025 (target 1). There has been no progress on this target since the start of the circular economy policy.

The department assessed that there is a risk that it will not reduce the amount of organic material going to landfill by 20 per cent by 2025 (interim target 3).

However, data limitations make it difficult to confidently measure progress towards this target.

Figure 3: Data quality and progress against targets, 2024

Source: VAGO.

The sections below provide further details about progress towards each target.

Every Victorian household is on track to have access to a food organics and garden organics waste service by 2030

Household recycling reforms

A key action under the recycle goal is to reform Victoria’s household recycling system. This includes ensuring every Victorian household has access to core waste and recycling services for:

- combined food organics and garden organics

- glass

- combined paper, plastic and metals

- residual waste.

To implement the household recycling reforms, councils are required by law to provide a 4-stream waste and recycling service. The department is:

- introducing regulations that requires all councils to give households access to a food organics and garden organics recycling service by 2027

- working with local councils to provide more kerbside bin services, such as for organic waste and glass.

For many households, this will mean having access to a 4-bin system. In some areas where kerbside bins are not suitable, such as apartment buildings or remote areas, people can access the 4-stream service through transfer stations or local drop-off points.

Sustainability Victoria is also delivering the education and behaviour change programs to help Victorians adapt to new 4-stream collection system.

Access to these services will make it easier for households to separate waste. This will reduce the volume of waste going to landfill and increase the reuse value of recovered materials.

Progress towards the target for organic waste

The circular economy policy has a target that every Victorian household has access to an organic waste recycling service or local composting by 2030.

If households have access to organic bin services, the department estimates it could divert up to 650,000 tonnes of organic waste from landfill each year.

Organic waste

Organic waste includes food scraps, food-soiled paper, garden trimmings, branches, paper towels and newspapers.

Once collected, organic waste can be composted and used to improve soil quality on farms and in parks and gardens. Organic waste that ends up in landfill rots and produces methane – a greenhouse gas.

Councils report on the number of households in their local government area that receive a food organics and garden organics recycling service. This includes whether the service is mandatory or voluntary.

Based on council reporting, every Victorian household is on track to have access to a food organics and garden organics waste service by 2030.

| In ... | of the 79 Victorian councils ... | or ... | reported that … |

|---|---|---|---|

| June 2019 | 17 | 22 per cent | they provide households in their local government area with access to a food organics and garden organics service. |

| June 2024 | 56 | 71 per cent |

However, some councils offer organic waste collection as an opt-in service. This means that progress against the target may not reflect the actual uptake of organic waste recycling services by households.

The department proposes to remove any opt-in services from 2027 in the service standard for how councils and alpine resorts must provide waste and recycling services to households.

More organic waste is being recovered but the volume entering landfill is unclear

Reducing organic waste going to landfill

According to the department’s waste projection model, in 2018–19:

- 1.65 million tonnes (65 per cent) of organic waste went to landfill

- 0.9 million tonnes (35 per cent) of organic waste was recovered.

The department set its circular economy policy target to reduce the amount of organic material that goes to landfill. From 2020 levels, it aims to reduce it by:

- 20 per cent by 2025

- 50 per cent by 2030.

According to the department’s waste projection model, households generated 58 per cent of Victoria’s total organic waste in 2022–23, while businesses only generated 36 per cent. This means giving households access to an organic waste service supports this target.

Landfill composition data

The department needs recent data on the volume of different types of waste in landfill to accurately track its progress towards this target. Landfill audits provide information, such as:

- types, or categories, of waste (such as plastic or organics)

- the sources of different types of waste (such as households or businesses)

- materials (such as plastic or organics)

- total volume of waste across each category.

However, there has not been a landfill composition audit since 2018. This means the department’s landfill composition data is outdated and it does not know how much organic waste enters landfill.

It therefore uses other methods to estimate how much waste goes to landfill, such as a proxy measure.

The department reports that it is currently exploring methods to obtain updated, reliable and cost effective data on landfill composition.

The volume of organic waste going to landfill

According to the department’s waste projection model, the volume of organic waste going to landfill only fell by 4.9 per cent from 2018–19 to 2022–23 financial.

It is unclear if the department is on track to meet the interim and 2030 organic waste landfill target because there is no up-to-date data to measure the actual volume of different waste streams going to landfill.

Proxy measure for the amount of organic waste diverted from landfill

Due to limitations measuring the amount of organic waste going to landfill, the department instead reports the volume of organic material diverted from landfill.

To calculate this proxy measure, the department draws on data from 2 surveys:

- the Victorian Recycling Industry Annual Survey (the recycling industry survey)

- the Victorian Local Government Annual Survey (the local government survey).

The recycling industry and local government surveys

The department conducts these voluntary surveys to collect waste and recycling data from local governments and industry stakeholders.

The recycling industry survey collects information about the types, volumes and sources of waste Victorians generate, send to landfill and recover from landfill.

The local council survey collects information about kerbside collection services and other council-related waste services, including the volume, cost and composition of waste. The department publishes the results on a publicly available dashboard.

Limitations of the proxy measure

The department compares trends in recycling industry survey responses with changes in the volume of organics collected from households over the same period reported in the local government survey.

However, the proxy measure has limitations because it:

- assumes all recovered organic waste would have gone to landfill

- does not account for hidden sources of organic waste, such as:

- illegal dumping

- composting

- organics that are incorrectly disposed of in general waste bins

- does not account for the possibility that the volumes of organic waste recovered and total organic waste generation have both increased

- relies on surveys, which can be unreliable because they are voluntary, and the quality of the responses can vary.

These limitations affect the department’s understanding of the flow of organic waste, especially how much enters landfill. This means it does not have a reliable measure to understand the actual change in organic waste entering landfill.

The volume of organic waste recovered

According to the department’s waste projection model, 74.4 per cent more organic waste was recovered in Victoria in 2022–23 than in 2018–19. This is an increase from 0.88 million tonnes to 1.53 million tonnes.

The largest increase was from household organic waste (130.8 per cent), which reflects the rollout of the 4-stream waste and recycling system.

Additionally, 58.8 per cent more organic waste was recovered from the business sector.

This means that although the department cannot reliably measure the actual amount of organic waste entering landfill, far more organic waste is being recovered since the circular economy policy began.

It is unlikely that 80 per cent of waste will be diverted from landfill by 2030

Diverting waste from landfill

When waste goes to landfill it loses its value because it cannot be reused, recycled or reprocessed into new materials.

Diverting waste also reduces the need for more landfill space. For example, the department reports that recycling one tonne of paper saves 3 cubic metres of landfill space.

The circular economy policy has a target to divert the total volume of waste going to landfill by:

- 72 per cent by 2025

- 80 per cent by 2030.

In 2018–19, 69.3 per cent of all waste generated in Victoria was diverted from landfill.

The volume of waste going to landfill has not changed

The department is not on track to achieve its interim target of diverting 72 per cent of waste from landfill by 2025. Since the circular economy policy started, the total waste recovery rate has remained constant at around 69 per cent, as Figure 4 shows.

Figure 4: Waste recovered and entering landfill (millions of tonnes), 2018–19 to 2022–23

Source: VAGO, based on data from the department's waste projection model.

It is unlikely that the government will meet its 2030 waste diversion target based on the current trajectory. However, there could be a path towards the 2030 target if the department fully rolls out the 4-stream waste and recycling system and invests in new recycling infrastructure through the Industry and Infrastructure Development Package (as intended).

For example, there are 4 thermal-waste-to-energy facilities currently under development in Victoria. These thermal-waste-to-energy facilities will have a combined capacity of 1.1 million tonnes per year.

Recycling Victoria may also issue licences for additional thermal-waste to energy facilities up to a combined capacity of 2 million tonnes under the government’s waste-to-energy cap.

If these thermal-waste-to-energy facilities come online and reach full operating capacity, up to 87 per cent of waste could be diverted from landfill based on current waste generation according to the waste projection model.

The Victorian Government’s Economic Growth Statement also announced a proposed uplift to the waste-to-energy cap limit to 2.5 million tonnes per annum, subject to a Regulatory Impact Statement process in early 2025.

There are opportunities to boost recycling for some waste streams and sectors

Waste generation in Victoria

In 2022–23, Victoria generated 14.6 million tonnes of waste.

The department tracks Victoria's waste generation for 8 key material types (see figures 5, 6 and 7).

| In 2022–23, the highest volume waste streams in Victoria were ... | which made up ... |

| aggregate, masonry and soils | 6.9 million tonnes. |

| organic waste | 3.1 million tonnes. |

| paper and cardboard | 1.6 million tonnes. |

| metals | 1.4 million tonnes. |

Household waste

In 2022–23, households generated the least amount of waste of the 3 main sectors. They generated 3.6 million tonnes of waste, or 24.9 per cent of Victoria’s total.

Household waste in 2022–23 was mostly made up of organic material, then paper and cardboard, and plastics, as Figure 5 shows.

Figure 5: Household (municipal solid waste) waste generation by material type, 2022–23

Note: Masonry includes building material, such as concrete and bricks. Numbers do not add up to 100 per cent due to rounding.

Source: VAGO, based on the department’s waste projection model.

Business waste

In 2022–23, businesses (the commercial and industrial sector) generated a slightly higher proportion of waste than households in Victoria. They generated 4.3 million tonnes of waste, 29.3 per cent of Victoria’s total.

Business waste was mostly made up of organics, metals and paper and cardboard materials, as Figure 6 shows.

Figure 6: Business (commercial and industrial) waste generation by material type, 2022–23

Note: Masonry includes building material, such as concrete and bricks.

Source: VAGO, based on the department's waste projection model.

Building sector waste

In 2022–23 the building (construction and demolition) sector generated the most waste. It generated 6.7 million tonnes of waste, or 45.8 per cent of the total.

This was predominately (95 per cent) material from aggregate, masonry and soils, as Figure 7 shows.

Figure 7: Building (construction and demolition) waste generation by material type, 2022–23

Note: Masonry includes building material, such as concrete and bricks.

Source: VAGO, based on the department's waste projection model.

The recovery of different waste materials

Figure 8 shows the recovery rate for each material type in 2022–23. Of the 4 highest-volume waste streams, metals had the highest rate of recovery (88.3 per cent), followed by aggregate, masonry, and soils (83.2 per cent).

This means both types of waste are being recovered at a higher rate than the 72 per cent interim circular economy policy target.

However, the recovery of the other 2 highest-volume waste streams – organic waste and paper and cardboard – are well below the interim target at 49.3 per cent and 59.2 per cent respectively. Other waste types with smaller volumes are also below the interim target.

Figure 8: Total waste recovered and entering landfill by material type, 2018–19 and 2022–23

Note: Masonry includes building material, such as concrete and bricks.

Source: VAGO, based on data from the department’s waste projection model.

Changes in resource recovery

The largest increase in resource recovery has been organic waste, which increased by 15 percentage points from 2018–19 to 2022–23, as Figure 8 above shows. This reflects the progress in the government’s household recycling reforms.

However, although paper and cardboard are the third largest waste streams, the proportion recovered fell by 6 percentage points from 2018–19 to 2022–23.

Resource recovery by source sector

The building sector both generates and recovers the most waste, as Figure 9 shows. It generates 45.8 per cent of all waste and recovers 84.5 per cent of this.

Figure 9: Total waste recovered and entering landfill by source sector, 2018–19 and 2022–23

Source: VAGO, based on data from the department’s waste projection model.

However, according to the department’s waste projection model, resource recovery has not improved for all sectors:

| For example, in 2022–23 … | which generated around … | of Victoria’s total waste, recovered … | Since 2018–19, its recovery rate has … |

|---|---|---|---|

| the building sector | 45.8 per cent | 84.5 per cent of its waste. | decreased slightly by 2.1 percentage points. |

| the business sector | 29.3 per cent | 55.2 per cent of its waste. | remained stable. |

| households | 24.9 per cent | 56.7 per cent of its waste. | increased by 11.0 percentage points |

This means that waste recovery has improved the most from households, which is the sector that generates the least amount of waste.

Opportunities to increase resource recovery

Figure 10 shows resource recovery in 2022–23 from different waste streams against the volume generated from households and the business sector.

Figure 10: Total waste recovered and entering landfill from households and businesses, 2022–23

Note: Masonry includes building material, such as concrete and bricks. Numbers do not add up to 100 per cent due to rounding.

Source: VAGO, based on data from the department's waste projection model.

The above figures show that there are opportunities to increase resource recovery for waste in the household and business sectors.

For example, there are opportunities to recover more plastic waste. Plastic waste recovery from households and businesses only marginally increased between 2018–19 and 2022–23.

| In 2018–19, plastic made up ... | of which … | but by 2022–23, the recovery rate had only increased by … |

|---|---|---|

| 12.6 per cent of household waste | 21.0 per cent was recovered | less than 1 percentage point to 21.6 per cent. |

| 8.4 per cent of business waste | 18.2 per cent was recovered | less than 4 percentage points to 21.7 per cent. |

More organic waste can be recovered from businesses. Business organic waste recovery has improved much more slowly than from households.

| In 2018–19, of all organic waste … | came from … | of which … | By 2022–23, the recovery rate increased by … |

|---|---|---|---|

| 49.9 per cent | households | 37.7 per cent was recovered. | 23.8 percentage points to 61.5 per cent. |

| 38.9 per cent | businesses | 25.3 per cent was recovered. | 10.1 percentage points to 35.4 per cent. |

There is also an opportunity to increase the recovery of paper and cardboard waste from businesses, which has gone backwards.

| In 2018–19, of all paper and cardboard waste … | came from … | of which … | but by 2022–23, the recovery rate fell by … |

|---|---|---|---|

| 74.8 per cent | businesses | 74.4 per cent was recovered | 10.5 percentage points to 63.9 per cent. |

These waste streams present opportunities to accelerate towards the 2030 target of diverting 80 per cent of waste from landfill.

4. Building Victoria’s recycling capacity

The department and other circular economy portfolio agencies have delivered key commitments and actions under the circular economy policy that have increased Victoria’s recycling capacity.

However, extensions to targeted completion dates of some key programs have slowed progress towards the government’s recycling targets.

Covered in this section:

- The department and other audited agencies have delivered most of the circular economy policy’s recycling commitments, but some key programs are delayed

- The department is building resilience in the waste and recycling sector, but there are gaps in information to fully understand service continuity risks

The department and other audited agencies have delivered most of the circular economy policy’s recycling commitments, but some key programs are delayed

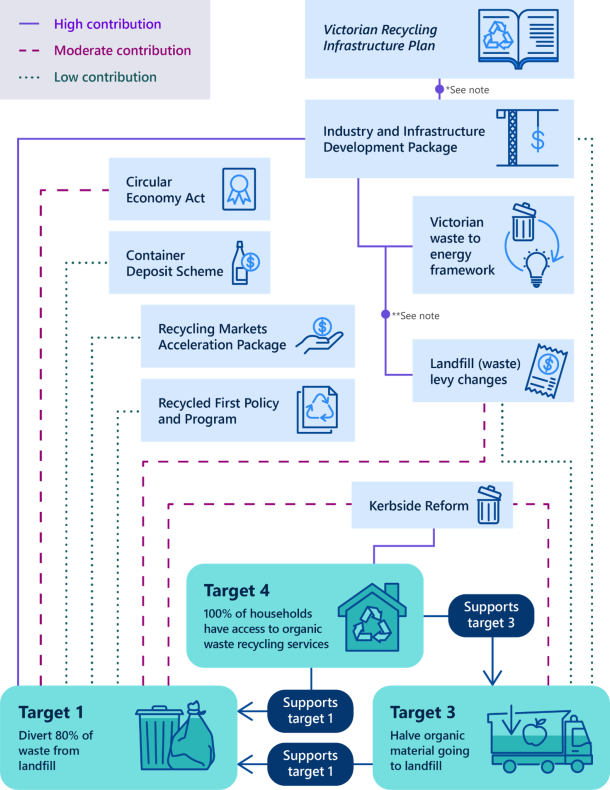

The expected contribution of key programs

In its early planning for the circular economy policy, the department mapped which programs would be key to achieving the policy’s targets and the estimated contribution of each (see Figure 11).

Figure 11: Circular economy planning – estimated program contribution to targets

Note: *The Victorian Recycling Infrastructure Plan enables attracting investment in infrastructure. **Increasing waste levies intends to make thermal-waste-to energy facilities better able to compete with landfill as a destination for waste disposal.

Source: VAGO, based on the department’s analysis.

The department estimated that attracting private investment in the right mix of infrastructure would divert the most waste from landfill. This would be followed by:

- overhauling household waste and recycling collection

- increasing Victoria’s waste levies

- new regulation and governance.

As of 2024, the department, Sustainability Victoria, EPA, and the Victorian Infrastructure Delivery Authority have completed 10 of these 14 programs as scheduled (see Appendix D, Figure D1).

This has considerably increased Victoria’s recycling capacity, as Figure 12 shows.

This progress includes introducing landfill levy reforms, which the department estimated would make one of the biggest contributions towards the circular economy policy’s landfill diversion targets.

Capacity

In this report we refer to recycling ‘capacity’ to describe Victoria's ability to recycle resources. Recycling capacity requires sufficient:

- infrastructure to recycle materials diverted from landfill

- capability, such as enough staff, knowledge, technology, or the right systems in place in government or industry to effectively manage the recycling sector.

Figure 12: Recycle goal program impacts on Victoria’s recycling capacity

| Program | Impact |

|---|---|

| Kerbside Reform | Improving Victoria’s capacity to recycle organic materials By increasing the number of councils providing households with access to a food organics and garden organics recycling service from 22% to 71% (see Section 3), the amount of household organic waste recovered has more than doubled (+131%) |

| Education and behaviour change | Improving the community's ability to understand proper recycling practices and adapt to new kerbside recycling systems |

The Container Deposit Scheme

| Supporting the diversion of material from landfill and boosting recycling. The department reports that:

|

Landfill levy reform, Illegal waste disposal program and landfill levy auditing

| Encouraging businesses and people to reduce waste and divert it from landfill by:

|

Regulations under the Circular Economy Act and a Victorian waste to energy framework

| Introducing:

|

| The Recycling Markets Acceleration Package | Giving grants to businesses to grow the recycling industry. The department reports that since 2020 it has provided more than '$16 million in funding supporting over 90 projects to accelerate markets for recycled materials' |

| Victorian Recycling Infrastructure Plan | Guiding the waste and recycling sector on opportunities to invest in priority infrastructure aligned to Victoria’s future recycling and resource recovery needs |

Reducing Regulatory Barriers

| Supporting industry’s capacity for resource recovery by:

|

| Recycled First Policy (EcologiQ) and local government Recycled First Programs | Increasing the government’s use of recycled and reused materials in major transport projects by 2.8 million tonnes and making local councils more aware of using recycled materials in procurement |

Source: VAGO.

Extensions to key programs

Agencies have revised some programs from their initial schedule. This delayed the completion of 4 recycle goal programs.

This includes 3 of the 4 programs that the department estimated would have the biggest impact on circular economy policy targets. One of these programs is the Industry and Infrastructure Development Package, which the department estimated would make the biggest contribution to recycling and landfill diversion.

| There was an extension to ... | from … | until ... | because … |

|---|---|---|---|

| the Kerbside Reform program (household bin services)* | 2023 | 2027 | councils require state government regulation, support and coordination until the full statewide roll out of the 4 stream waste and recycling system is complete in 2027. |

| finalising the Circular Economy Act* | 2023 | 2025 | the department introduced a third bill to support the container deposit and waste-to-energy schemes. |

| part of the Recycling Markets Acceleration Package | 2024 | 2025 | Sustainability Victoria requested more time to complete its component of the package because grant program announcements were delayed during the state election caretaker period. |

the Recycling Industry and Infrastructure Development Package*

| 2024

| 2027

| some projects were delayed due to government approvals, EPA licensing permissions and international resource constraints. Sustainability Victoria received $15.6 million from the Australian Government to deliver a project to recover hard-to-recycle plastics. |

Note: *Indicates 3 programs that the department estimated would have the biggest impact on circular economy policy targets.

See Appendix D, Figure D1 for the full list of programs and revised dates.

Sustainability Victoria will continue to deliver education and behaviour change programs to support the ongoing implementation of the Kerbside Reform program.

It is important that Sustainability Victoria fully delivers the Industry and Infrastructure Development Package to stimulate investment in new recycling and waste processing infrastructure. This will create markets for waste that would otherwise go to landfill and increase the quality and reuse value of recovered materials.

Sustainability Victoria estimates that the Industry and Infrastructure Development Package will deliver more than one million tonnes of new capacity by 2025, such as:

- recovering and reprocessing organic, plastic, paper, cardboard, glass, textile, chemical and tyre waste

- generating energy from waste that cannot be recycled and would otherwise go to landfill.

Victoria needs enough infrastructure to meet increasing recycling demands, especially as the population grows.

The department is supporting sector resilience but there are gaps in mandatory risk reporting by some operators in the waste, recycling and resource recovery sector

Circular economy risk planning

Under the Circular Economy Act, the department published the inaugural Circular Economy Risk, Consequence and Contingency Plan (circular economy risk plan) in May 2024. The plan outlines:

- global, national and Victorian sector trends impacting waste, recycling and resource recovery

- their potential impacts on service continuity and the transition to a circular economy

- sector risks that may impact service continuity or the transition to a circular economy

- data to enable industry to assess its service criticality and determine if it meets criteria to provide risk reporting for its operations to Recycling Victoria.

The circular economy risk plan also gives the waste, recycling and resource recovery industry risk management guidance to help improve sector resilience.

The Circular Economy Act requires major waste and recycling service providers that, if disrupted, would seriously impact service continuity, to give regard to the circular economy risk plan. These providers are known as responsible entities.

The Act also requires responsible entities to report annually to the head, Recycling Victoria on their risk planning in an annual Responsible Entity Risk Consequence and Contingency Plan (responsible entity risk plan).

Under the Circular Economy Act, the department also introduced the Circular Economy (Waste Reduction and Recycling) (Risk, Consequence and Contingency Plans and Other Matters) Regulations 2023.

The regulations give the definition of a responsible entity and additional requirements relating to the preparation and content of the circular economy risk plan and responsible entity risk plans.

Responsible entities

Responsible entities are waste and recycling service providers that would pose a serious risk to Victoria’s waste and recycling system if they were disrupted. They may include garbage truck companies, landfill operators, recycling facilities and thermal-waste-to-energy facilities.

Waste and recycling service providers self-identify if they are a responsible entity based on whether they:

- provide an essential service

- make up more than 20 per cent of the recycling, waste or resource recovery market in Victoria

- hold one or more government contracts, with a total combined value of over $50 million over the life of the contract/s

- provide an ongoing service (across 5 or more regions).

| The Circular Economy Act and the regulations require that each year ... | must prepare … | so that ... |

|---|---|---|

by 31 December, the head, Recycling Victoria (within the department)

| a circular economy risk plan and submit it to the Minister for approval

| it can (among other things):

|

| by 30 September, responsible entities | responsible entity risk plans, with regard to the circular economy risk plan, in conjunction with a statement of assurance | the department can better monitor and review risks and report how to respond to them in the circular economy risk plan. |

In September 2024 the department received its first tranche of responsible entity risk plans from 24 responsible entities. The department will consider the information responsible entities have provided in their past risk plans when it updates subsequent circular economy risk plans.

Information gaps in responsible entity risk plans

In May 2024, Recycling Victoria published guidelines that outline the mandatory requirements for responsible entities when they publish, prepare and submit their risk plans to it.

We assessed a sample of 10 responsible entity risk plans. Only one met all mandatory requirements. The other 9 did not include enough information to meet the department's mandated requirements and guidelines.

These information gaps may limit the department’s ability to:

- understand and build knowledge of risks to the sector, such as waste material flows and continuity of waste and recycling services

- identify new or existing risks

- understand whether responsible entities are taking appropriate actions and contingency measures to minimise and manage risks.

Because this is the first year implementing the circular economy risk plan process, there are clear opportunities for the department to support responsible entities to improve their reporting in future years.

5. Understanding and communicating waste flows

Not all data the department uses to track different waste streams is reliable. This may compromise the accuracy of the way it tracks its progress towards its recycling targets, and projects Victoria's future recycling needs. The department does not account for this uncertainty, or communicate it, in the projections it publishes.

Covered in this section:

- Limitations in data used to measure progress towards targets and project future waste flows

- Communicating uncertainty in future waste flow projections

Limitations in data used to measure progress towards targets and project future waste flows

Data sources for understanding waste flows

The department uses a range of data sources to determine how much waste goes to landfill and is recovered across Victoria.

| The department uses … | which includes ... | to understand … |

|---|---|---|

| waste levy statement data | the amount of waste received and recovered from landfill sites, based on waste levy fees charged | the total amount of waste sent to landfill. |

recycling industry survey data, which is a voluntary survey that collects information from the waste, recycling and resource sector

|

| the total amount of waste diverted from landfill for reprocessing.

|

| Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) waste export data (based on Australian Border Force Export Declarations) | waste exported from Australia by state and territory | |

Victorian Local Government Annual Survey (local government survey)

|

| changes in the volume of organics collected from households (compared with the recycling industry survey responses).

|

The department uses these datasets to measure its progress against circular economy policy targets. It also uses them to project future waste volumes and recycling needs and opportunities.

The reliability of data sources

The reliability of the department’s waste projections and reporting towards its circular economy policy targets depends on the accuracy of the data it uses. This matters because government agencies and the waste and recycling sector make investment decisions based on these reports and projections.

However, some data sources the department uses to inform waste flow projections and progress against targets have inherent uncertainty.

| Data… | has limitations because … | This means ... |

|---|---|---|

from the recycling industry survey

| it is a voluntary survey, and the completeness of responses varies across survey questions. The department uses other responses to estimate the responses for facilities that do not respond. | the department cannot enforce responses or the quality of the responses it receives. Responses may not include comprehensive information on waste flows. In 2024, the response rate was 49 per cent (representing 59.5 per cent of all waste reprocessed) from expected facilities. |

| from the local government survey | it is a council-reported survey that relies on the reliability of council data. | it can be subject to respondent error, unreliable source data and inconsistencies in how survey respondents interpret and report figures. |

| from ABS waste export data | according to the ABS, it cannot guarantee that exporters or agents reported the correct codes or values for the materials they export. | it may not reflect the volume of waste exported from Victoria, which is a key part of the department’s projections in the Victorian Recycling Infrastructure Plan. |

| about landfill composition | the department has not completed a landfill audit since 2018. | the department cannot verify any change in landfill composition volumes since 2017–18. |

| about hidden waste streams | the department has low visibility of waste streams where there is limited existing infrastructure to manage or reprocess them. | the department has limited or no information on some waste flows, such as e waste and emerging material streams (for example, wind turbines and solar panels). |

Efforts to make data more reliable

The department acknowledges these limitations and has taken steps to improve the reliability of the data it uses. These include:

- tracking the distribution and engagement of industry with the recycling industry survey

- conducting the recycling industry survey at the facility level instead of company level

- using actual data to estimate waste flow volumes from facilities who do not respond to the recycling industry survey

- conducting quality assurance on information collected in the local government survey by comparing current data historical trends and between councils to identify discrepancies

- using data collected by industry to confirm results, including the Australian Tyre Consumption and Recovery and Australian Plastics Flows and Fates datasets

- engaging and educating industry and councils on the importance of the recycling industry survey and local government survey respectively

- introducing a new legislative framework for Recycling Victoria to collect, share and report on data from a range of entities with regulations to enact the framework to follow.

While these actions are positive steps, some uncertainty remains in the accuracy and completeness of these datasets.

The department does not clearly communicate uncertainty in its waste flow and demand projections

The department’s waste projection models

The department uses its waste flow data as inputs in 2 projection models. These are:

- a publicly available waste projection model, which the department releases as an online dashboard

- the Waste and Resource Recovery Projection Model, which informed the Victorian Recycling Infrastructure Plan that the department released in 2024.

Both models project the volume of different waste streams out to 2053 based on actual numbers from previous years.

For the Victorian Recycling Infrastructure Plan, the department also analysed Victoria’s reprocessing capacity based on actual waste and recovery data up to 2021. Together, the projections and capacity analysis signal opportunities to the waste and recycling sector.

By doing this, the department intends to use the Victorian Recycling Infrastructure Plan to support industry growth to meet Victoria’s future waste management and recycling needs.

The reliability of projections

The department uses sound and rigorously implemented projection methodologies in both the Victorian Recycling Infrastructure Plan and waste projection model. The department documents its methodologies in detail.

However, because some input data is unreliable, there are likely to be varying degrees of uncertainty in the department’s 30-year estimates of future waste generation and recovery.

Multiple uncertainties could make these projections less accurate over the medium to long term.

Communicating uncertainty to the waste and recycling sector

The department could more clearly communicate the uncertainties in its future waste projections in its Victorian Recycling Infrastructure Plan. But uncertainties in its dataset mean it is unlikely that that any of these single number estimates will be exactly correct.

The department does not fully explain how it accounts for these uncertainties in its future waste flow projections. For example, by undertaking a sensitivity analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

A modelling tool used to analyse how different levels of an input affect an output or outcome under a certain set of assumptions. This means analysing how various uncertainties (such as change in population) contribute to the forecast's overall uncertainty by posing 'what if' questions.

The department includes a qualitative sensitivity assessment in its Victorian Recycling Infrastructure Plan to flag its uncertainty about each type of waste under different scenarios. It also acknowledges the limitations of its data in the plan's appendices.

But it does not fully explain how it accounts for these uncertainties in its projections. For example, the department pulls in different data sources and combines them into a dataset it uses to create projections. But the reliability of these sources varies, and the department has not demonstrated it has factored this unreliability into its projections.

Rather than a single-point estimate, the department should communicate a range of estimates to account for the uncertainties. This is because the waste and recycling sector need to understand the degree of uncertainty in waste projections to have the confidence to make well-informed investment decisions.

Appendix A: Submissions and comments

Download a PDF copy of Appendix A: Submissions and comments.

Appendix B: Abbreviations, acronyms and glossary

Download a PDF copy of Appendix B: Abbreviations, acronyms and glossary.

Appendix C: Audit scope and method

Download a PDF copy of Appendix C: Audit scope and method.

Appendix D: Circular economy programs

Download a PDF copy of Appendix D: Circular economy programs.