Road Safety Camera Program

Overview

This audit examined whether the road safety camera program is effective. It assessed whether:

- there is a sound rationale for the program

- cameras are sited for road safety outcomes

- the camera system is accurate

- infringements issued from the system are valid

- public communications about the program are effective.

The road safety camera program is effective. It is well-supported by evidence that clearly demonstrates that cameras improve road safety and reduce road trauma. Siting of cameras is based on road safety outcomes, not to raise revenue. To enhance the program, aspects of it could be further evaluated, including the effectiveness of fixed and point-to-point cameras, and whether the current approach for deploying mobile cameras is optimising outcomes.

The processes and controls over the camera system provide a high level of confidence in the reliability and accuracy of the system in measuring speed and detecting red-light running. Greater assurance about the accuracy of mobile cameras could be gained through independent testing under actual conditions. Police discretionary enforcement thresholds and other features of the program provide a high level of confidence that infringements are valid.

Despite the strong rationale for the program and the high level of integrity of its systems, public concern about the program persists. This has placed its ongoing legitimacy at risk. During the audit, the Department of Justice developed a communication strategy to address these concerns. The Department of Justice will evaluate this to determine whether it has been effective in aligning public understanding with the evidence supporting the program and its road safety benefits.

Road Safety Camera Program: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER August 2011

PP No 3, Session 2011–12

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my performance report on the Road Safety Camera Program.

Yours faithfully

![]()

D D R PEARSON

Auditor-General

31 August 2011

Audit summary

Road trauma is a significant concern of the community and government. In 2010, there were 4 503 crashes on public roads that resulted in fatality or serious injury, with 288 people dying on Victoria’s roads. Road trauma costs the Victorian economy an estimated $3.8 billion a year.

While road crashes are caused by a variety of interacting factors, speeding and red‑light running have been identified as significant factors. Speeding is identified as the primary cause of about a third of road casualties each year. Speeding increases the likelihood of a crash, with even small increases above the speed limit resulting in a significantly greater risk of crashing. Furthermore, the faster a vehicle is travelling, the greater the severity of the crash and the likelihood of fatality and serious injury. Red‑light running is similarly linked with crash risk and severity. Crashes at major metropolitan intersections account for around 20 per cent of all fatal and serious injury crashes. Around 20 per cent of injury crashes that occur at intersections involve red‑light running.

The road safety camera program has been operating since 1983 and is a component of Victoria’s current road safety strategy, arrive alive 2008–2017, which aims to reduce road trauma by 30 per cent. Road safety cameras are an enforcement approach that is intended to improve the behaviour of road users. Mobile and fixed speed cameras aim to enforce speed limits and deter drivers from speeding, and fixed red-light cameras aim to deter drivers from running red lights.

In 2009–10, 1 156 673 infringements were issued from road safety cameras for speeding and 147 505 for red‑light running. These numbers will vary if infringements are withdrawn or reissued. Revenue collected from these infringements amounted to $211.3 million, which is 0.47 per cent of the total general government revenue for 2009–10.

Sections of the community and media have shown significant interest in the road safety camera program, voicing concerns about whether using cameras is appropriate, the accuracy of cameras, and the validity of infringements. Some allege that the purpose of the road safety camera program is to raise revenue, while major faults such as those of the Western Ring Road fixed speed cameras in 2003 and the nine incorrect fines issued on the Hume Freeway point-to-point cameras in 2010 have served to erode public confidence in the program.

The audit examined whether there is a sound rationale for the road safety camera program and whether the cameras are sited for road safety outcomes. It also examined the accuracy of the camera system and whether the public can be confident that an infringement is valid.

Conclusions

Road safety cameras improve road safety and reduce road trauma, and their ongoing use as an enforcement tool remains appropriate. The supporting technology used and the way the camera system operates provide a high degree of confidence that infringements are issued only where there is clear evidence of speeding or red-light running.

A strong body of research shows road safety cameras improve the behaviour of road users, and reduce speeding and road crashes. Cameras cannot differentiate between different road-users groups with varying levels of road trauma risk. However, at‑risk groups are appropriately targeted by non-camera approaches within the broader arrive alive 2008–2017 road safety strategy.

Any program that aims to deter dangerous and risky behaviour through the use of fines will generate revenue, but this is demonstrably not the primary purpose of the road safety camera program. In fact, more revenue could be raised through tightening operational policies that provide for some leniency to speeding drivers and therefore reduce the number of infringements issued.

The deployment and siting of fixed and mobile cameras is based on the road safety objectives of the program. Further revisions to operational approaches, such as random deployment of mobile cameras, should however strengthen the program.

While there can be no absolute guarantee over the accuracy of any system, the processes and controls in place provide a particularly high level of confidence in the reliability and integrity of the road safety camera system.

There are aspects of the program that can be further strengthened to allay public perceptions about its integrity and purpose. First, the lack of past evaluations of fixed speed cameras on freeways, and failure to provide for the ongoing, systematic review of their efficacy is a gap in Victoria’s evaluation program. Second, mobile cameras warrant a program of independent testing of their accuracy under actual operating conditions—as is the case for fixed cameras.

The Department of Justice (DOJ) can also more purposefully develop and manage its communication and public education programs to specifically address the widely held misconceptions that the road safety camera program’s primary purpose is to raise revenue and that the cameras are inaccurate. In addition, greater attention to promoting the positive contribution the road safety camera program makes to Victoria’s road safety is needed.

Findings

Rationale for the road safety camera program

The road safety camera program is part of a broader road safety strategy, arrive alive 2008–2017, that is based on the road safety principles of the Safe System approach. The Safe System approach forms the basis of the National Road Safety Strategy 2011–2020 and is acknowledged by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, the World Health Organisation and the United Nations as the optimal approach for improving road safety.

Of arrive alive’s three focus areas, the road safety camera program is a component of safer road users, which aims to improve the behaviour of road users. The rationale for attempting to change driver behaviour to reduce speed and red-light running is sound. Both behaviours increase the risk and severity of crashes, and improvements in these behaviours should result in less road trauma. Enforcement mechanisms, including road safety cameras, are effective in changing dangerous driver behaviour.

Australian and international evaluations strongly support using road safety cameras to improve road safety. These evaluations have consistently found that cameras improve road safety outcomes through reduced speeding, fewer crashes and less road trauma.

Evaluations of Victoria’s mobile cameras and fixed speed/red-light cameras demonstrate their effectiveness in reducing the frequency and severity of road trauma. However, there are gaps in Victoria’s research program. Fixed speed cameras on freeways have not been extensively evaluated in Victoria, and point-to-point cameras have never been evaluated.

Cameras cannot differentiate between road user groups that may have different levels of road trauma risk. At-risk road user groups are appropriately targeted by a range of road safety measures, which can include cameras. Motorcyclists are 30 times more likely to experience road trauma. However, because some cameras can only record front numberplates, camera coverage over motorcyclists is limited by the lack of front numberplates with which to identify risky road users.

Siting cameras for road safety outcomes

Since 2007, fixed camera siting has been informed by sound criteria based on road safety outcomes and not on maximising revenue. These criteria address factors known to increase crash risk and severity, as well as considering the physical suitability of a site.

DOJ systematically prioritises sites for fixed cameras at intersections. However, due to the lack of available research evidence, it does not have a similar systematic approach for prioritising sites for other types of fixed camera sites.

Mobile cameras are deployed across about 2 000 sites that must be physically suitable and satisfy at least one of four deployment criteria. Deployment criteria are based on a site’s crash likelihood and crash severity risk. The use of such criteria is consistent with other jurisdictions. However, using deployment criteria limits the ability of police to site cameras ‘anywhere, any time’. Furthermore, these criteria could create and reveal siting patterns, which local drivers could identify and then adjust their behaviour accordingly. Application of deployment criteria could reduce the effectiveness of the mobile camera program in reducing speeds generally across the road network. There has been no research in Victoria to determine whether the current approach for siting mobile cameras is optimal.

Local police determine the monthly deployment of mobile cameras to approved sites based on local priorities. However, this approach may also reduce the effectiveness of mobile cameras, in comparison to other approaches such as random deployment. Mobile cameras are not deployed often enough at night, are deployed in discernible patterns and are being used in effect as ‘fixed cameras’ by being regularly located at single locations. Consequently, there is an increased likelihood that the general deterrence effect of the mobile camera system would be diminished.

Publishing the weekly roster of mobile camera sites is also inconsistent with the program’s aim to create general deterrence. Given the connection between speeding and road trauma, and the demonstrated effect of cameras in reducing speeding, there is a likelihood of increased adverse road safety outcomes as a result of this practice. This is particularly so in areas of country Victoria where residents can identify local areas where there is no mobile camera enforcement.

Accuracy and reliability of the camera system

DOJ has developed appropriate specifications for fixed and mobile camera equipment so that they measure speed accurately and reliably. All camera equipment is tested extensively against these specifications and must demonstrably comply with the specifications before becoming operational.

Maintenance and testing of fixed cameras is comprehensive and methodologically sound. Testing is conducted by appropriately accredited independent organisations. Testing and maintenance of fixed camera equipment, including annual certification testing, is frequent enough to maintain accuracy and reliability.

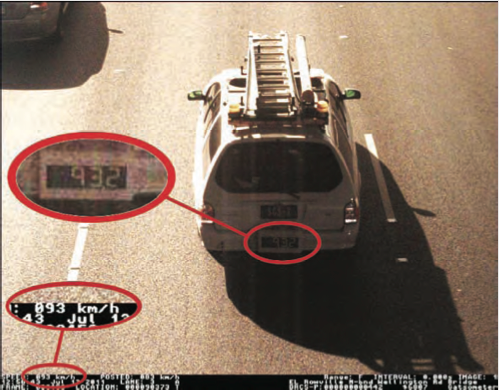

Maintenance and testing of mobile cameras is sound. During the set up for each mobile camera session, the camera’s speed measurement is required to be tested. This session testing, together with yearly maintenance and certification testing, is frequent enough to maintain a high level of assurance over the accuracy of the cameras. Notwithstanding the fundamental strength of the testing and maintenance regime, even greater assurance could be provided by a program of independent testing under roadside operating conditions.

DOJ has a strong, systematic approach to monitoring the fixed camera network for faults and degradation. The rigour of this approach has increased in response to the major faults detected in the Western Ring Road fixed cameras in 2003. DOJ gets information on camera performance from a comprehensive range of sources including test reports and evidence monitoring. This provides assurance that any faults or degradation of fixed cameras will be identified and rectified quickly.

Performance of mobile camera equipment is monitored and managed by the mobile program provider. Regular robust mechanisms for detecting equipment faults and degradation, including session checks, continuous monitoring of evidence, and annual workshop maintenance provide confidence that cameras are only used if they are operating in accordance with technical specification requirements.

Validity of infringements

The road safety camera system has a number of mechanisms to provide additional assurance that infringements issued are valid.

A police discretionary enforcement threshold is applied to all speeding infringements detected by speed cameras. This provides a very high level of confidence that drivers issued with an infringement exceeded the speed limit. This enforcement threshold is above that required by the Road Safety Act 1986.

Since 2004, all fixed speed cameras except point-to-point have two separate, independently-designed speed measurement methods. Regardless of how far over the speed limit the primary device records a driver, if the secondary corroborating measurement is not within 2 km/h, an infringement will not be issued. This significantly reduces the likelihood that infringements from fixed speed cameras are invalid.

At the start of each mobile speed camera session, the camera operator is required to compare the camera’s speed measurement against a radar of independent design. If this comparative test does not read within a defined tolerance the session should not proceed. The operator is required to declare in writing each time that this test was performed successfully, and can be called upon to confirm this in court. Nonetheless, independent assurance, such as photographic evidence of the test being carried out, would provide stronger evidence that the test was conducted.

Point-to-point cameras measure average speed. A driver measured by point‑to‑point cameras as having exceeded the speed limit would have had to maintain a travelling speed significantly above the speed limit for the duration of the camera zone. A secondary corroboration system is currently being installed to provide greater assurance over the validity of infringements issued from this system. Had this been in place since activation, it is unlikely that the nine incorrect Hume Freeway infringements would have been issued in 2010.

For red-light infringements, cameras record two images, one of a vehicle entering the intersection on a red light and a second as the driver continues through the intersection on that red light. Vehicles are only detected and photographed shortly after the change to red. An infringement is issued only if the two photos show that this incident occurred. Furthermore, there can be additional confidence in red-light infringements as drivers can review both photographs.

Before an infringement is issued, the evidence is reviewed to make sure it is valid. There are robust processes in place to verify infringements. These processes are designed to promote verification accuracy, with contractual incentives based on accuracy of verification as opposed to maximising infringements and revenue. After the evidence is verified, Victoria Police further review a sample of lower-level speeding incidents and red-light incidents, and all loss of licence incidents before infringements are issued.

All cameras are subject to independent certification testing, which is used as evidence of camera accuracy in court. Two certification providers are used by DOJ and both meet the requirements of the Road Safety Act 1986. While the record keeping and transparency of documentation of one of the certification providers needs to be improved, VAGO found no shortcomings with certification testing.

Public communications about the program

In contrast to the integrity and strength of the road safety camera program, the road safety partners have not adequately addressed public concerns surrounding the program’s purpose, effectiveness and integrity. Some common misconceptions are shown in Figure 1, including references to the sections of the report that relate to these misconceptions.

One of the most persistent public misconceptions surrounds the purpose of road safety cameras. Government and departmental documents consistently demonstrate that the road safety camera program’s objective is to reduce road trauma and improve road safety outcomes. There is no evidence that the primary purpose of the program is to raise revenue.

On the contrary, reasonable police operational decisions and the discretionary enforcement threshold afford leniency to speeding drivers that reduces potential revenue.

Prior to 2011, the road safety partners had not developed an adequate, coordinated communication strategy to counter negative misconceptions. However, DOJ has progressively increased the amount of information available about the program to the public. During the conduct of this audit, DOJ developed a communication strategy aimed at addressing public concerns regarding road safety cameras. This meets the requirements of a sound communications strategy, and includes a plan to evaluate all future communications initiatives.

Figure 1 Common misconceptions concerning the road safety camera program| Misconception | VAGO’s evidence against misconception |

|---|---|

The purpose of the road safety camera program is to raise revenue |

Government and departmental documents consistently state the purpose of the road safety camera program is improving road safety outcomes and that decisions around camera siting are based on improving road safety outcomes. Operational procedures limit the total potential revenue generated by the program. A police discretionary enforcement threshold above the speed limit is applied. More revenue could be raised if this was not applied. |

Low-level speeding is safe |

Even small increases above speed limits are dangerous. Research shows that driving 5 km/h over the limit in a 60 km/h zone doubles the risk of crashing. For pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists, small increases in speed substantially increase the severity of road trauma experienced. |

Road safety cameras don’t reduce road trauma |

An extensive body of research and evaluations both throughout Australia and overseas have demonstrated that road safety cameras result in improved road safety outcomes including lower speeds and reductions in fatalities and serious injuries from crashes. |

Road safety cameras are sited to maximise revenue |

Fixed and mobile road safety cameras are sited according to criteria based on road safety objectives. There are no incentives for police or other agencies involved in siting decisions to encourage siting based on maximising revenue. |

Speed cameras should not be placed on freeways because freeways are safe |

While freeways are often well designed and constructed roads, the large traffic volumes and high speeds of freeways reduce the inherent safety of these roads and mean that crashes are likely to have serious road trauma consequences. Between 2006 and 2010, 122 people died as a result of crashes on roads in metropolitan Melbourne 100 km/h zones, which are typically freeways. |

The cameras are faulty, as shown by the fines withdrawn from the Road Safety Act 1986. |

There are rigorous equipment management processes including frequent testing and maintenance. Additional policies and procedures around detecting faults and equipment degradation have been put in place since 2004, including the requirement for two separate speed measurements. This reduces the chance of an incorrect fine to close to zero. This requirement was introduced in response to the Western Ring Road faults. |

Note: These misconceptions have been selected based on examination of media articles, public surveys and submissions received for this audit.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Recommendations

- The Department of Justice should continue its focus on evaluation, though priority should be given to evaluating the effectiveness of both fixed freeway cameras and point‑to‑point camera systems.

- VicRoads, in partnership with the Department of Justice, Victoria Police and the Transport Accident Commission should address the gap in speed enforcement for motorcyclists.

-

To determine the optimal deployment approach for mobile

cameras, Victoria Police should conduct and evaluate pilots of the following

alternative approaches:

- site selection based only on physical criteria, not deployment criteria

- random rostering.

-

To increase the effectiveness of the mobile camera

program:

- the Department of Justice should review the impact of publishing the list of weekly rostered sites for mobile cameras on road safety

- Victoria Police should establish a target number of sites required across Victoria and within police divisions to provide sufficient geographic coverage, and establish a procedure for getting assurance that permanently unsuitable sites are replaced with new sites

- Victoria Police should determine a target proportion of monthly hours to be allocated at night.

- To strengthen assurance, the Department of Justice should establish regular independent testing of the accuracy and reliability of speed measurement by mobile speed cameras under actual operating conditions.

- To increase assurance over the accuracy of infringements from mobile cameras, the Department of Justice should get stronger assurance that mobile camera operators comply with critical procedures.

- To increase transparency of certification, the Department of Justice should require that all certification service providers comply with appropriate quality control and documentation standards, and are subject to regular audits against these standards conducted by appropriately qualified measurement experts.

- The Department of Justice should expedite the implementation of its communication strategy with a particular emphasis on addressing misconceptions about the program.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Justice, Victoria Police, VicRoads and the Transport Accident Commission with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments, however, are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Road trauma

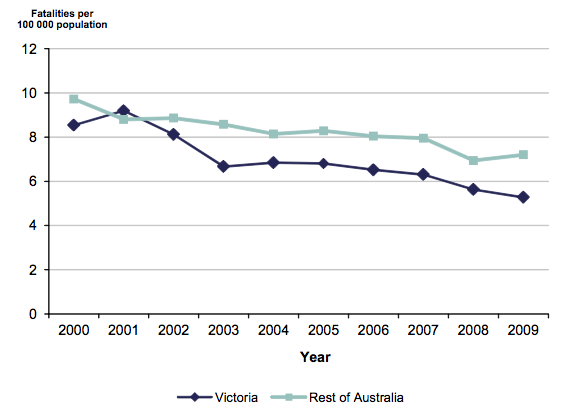

Victoria's road toll has consistently been below the national average and, particularly in recent years, lower than most other jurisdictions. From a peak of 1 061 deaths in 1970, the road toll fell to 288 in 2010. Figure 1A shows the road toll of Victoria compared to the rest of Australia between 2000 and 2009, per 100 000 population. The road toll does not include deaths on private roads and is adjusted down by Victoria Police to exclude deaths it judges either to be intentional or from natural causes.

Figure 1A

Road toll of Australian states and territories (excluding Northern Territory) by 100 000 population between 1999 and 2009

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics and the Federal Department of Infrastructure and Transport.

1.1.1 Causes of road trauma

Road crashes are caused by interacting factors. Road safety research has shown factors that can influence the likelihood and seriousness of a road crash include:

- speed of vehicle

- running red lights

- driver alcohol or drug consumption

- driver fatigue

- driver inexperience

- design of the road

- quality of road surface

- volume of traffic

- design of the vehicle and protection it provides passengers

- type of object hit, e.g., concrete barricade vs a wire fence.

Speed and road trauma

Speed is the main cause of about a third of road casualties, equating to about 100 deaths and 2 000 serious injuries a year.

There are many ways speed increases the likelihood of a crash. According to a 2006 Austroads report, as the speed of a vehicle increases:

- the driver is more likely to lose control

- the driver is more likely to miss important hazard cues

- the vehicle will travel further before the driver brakes in response to a hazard

- the vehicle will travel further after braking before it stops

- other road users are more likely to misjudge the vehicle's speed.

Crash severity describes the seriousness of the trauma to the people in a crash and is determined by how much energy the occupant absorbs on impact. There are direct relationships between the severity, the speed at which the vehicle or vehicles were travelling, and the protection afforded to those in the crash. The more energy absorbed by those involved, the more serious the road trauma. In 2010, there were 4 503 road crashes on public roads in Victoria that resulted in fatality or serious injury.

Recent research in Western Australia estimates that if all vehicles on that state's roads slowed by 1 km/h, it would result in 10 fewer fatalities a year or 5 per cent of the road toll, and in 90 fewer people experiencing serious injuries.

Red-light running and road trauma

Major metropolitan intersections are the site of 20 per cent of all fatal and serious injury crashes. Around 20 per cent of injury crashes that occur at intersections involve red‑light running. This high incidence of road trauma is partly because intersection crashes are often side-impact collisions and involve speed.

Time of day and road trauma

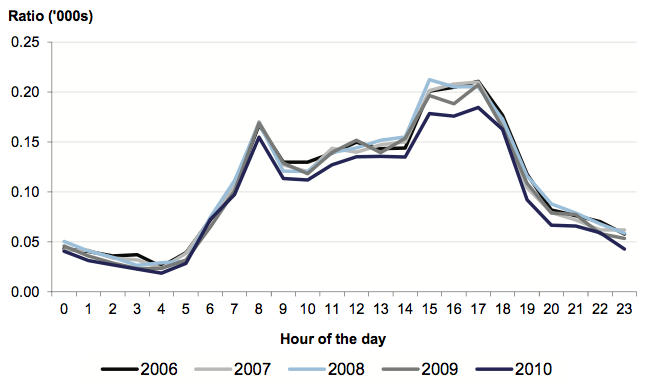

There is a consistent pattern in the time of day when crashes occur. Crashes peak at around 8 am and between 3 pm and 5 pm as shown in Figure 1B.

Figure 1B

Ratio of the number of crashes to the Victorian population

by time of day, 2006–2010

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on VicRoads data.

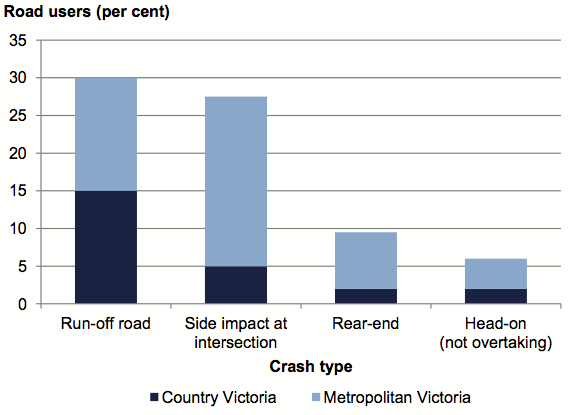

Crash type and road trauma

The most common types of crashes are:

- run-off road

- side-impact at intersection

- rear‑end

- head-on.

These account for around 72 per cent of all fatal and serious injury crashes each year. Of metropolitan fatal and serious injury crashes, side-impact at intersection and run-off road crashes are the most common crash types, while run-off road crashes are the most likely crash type for rural Victoria. This is shown in Figure 1C.

Figure

1C

Most common crash types for fatal and serious injury crashes

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on VicRoads data.

1.1.2 Impact of road trauma

Despite the reductions in the road toll, road trauma is still of concern to the community and government.

Road crash fatalities and serious injuries burden the community socially and economically. The cost is estimated at $3.8 billion a year when opportunity costs, such as lost earnings are considered. Caring for people with spinal cord and brain injuries is also costly. Every year, about 90 people suffer severe brain injury and around 1 000 suffer less severe brain injuries as a result of road crashes. The Transport Accident Commission (TAC) concluded that on average, across a lifetime, it costs $2.1 million to support a person with traumatic brain injury, $1.2 million for a person with paraplegia and $6.4 million for a person with quadriplegia.

Over and above this are the personal costs for the individuals involved in road crashes, their family and friends, and the community.

1.2 Policy response

Successive governments have worked to improve road safety and reduce the road toll. In 1970 Victoria was the first jurisdiction in the world to require the wearing of seatbelts, and in 1976 the first to introduce random breath testing for blood alcohol concentration.

Strategies have focused on addressing the causes of road trauma, including speeding and driver fatigue, as well as measures to reduce the severity of the trauma, such as vehicle safety improvements.

1.2.1 arrive alive

The arrive alive 2002–2007 strategy was Victoria's first integrated road safety strategy. To reduce the road toll, the strategy named 17 challenges, including speeding, drink driving, fatigue and occupant protection. It proposed an integrated suite of measures to address these challenges, including ongoing enforcement using road safety cameras.

The next phase of the road safety strategy, arrive alive 2008–2017, is based on the Safe System approach. This approach recognises that even with the best preventative measures in place, human error will result in crashes; therefore, measures are needed to reduce the impact of these mistakes. The strategy has three focus areas: safer roads and roadsides, safer vehicles, and safer road users. Road safety cameras are a measure under the safer road users focus area.

1.3 Road safety cameras

Red-light cameras were first installed in 1983 and mobile speed cameras were introduced in 1989. Before this, police officers were the sole enforcers of speeding and red-light running, issuing on-the-spot fines for offences.

The camera program has since expanded to:

-

213 sites with fixed digital cameras (with 32 installed but awaiting Ministerial approval to be turned on):

- 37 highway speed sites

- 175 speed/red-light sites at intersections

- 1 speed/red-light site at a railway level crossing site in Bagshot, near Bendigo

- 26 fixed wet film (non-digital) red-light cameras rotated through 40 intersections

- 4 point-to-point zones on the Hume Freeway across 10 of the 37 highway speed sites

- 85 mobile speed camera cars used across 2030 approved sites.

The cameras detect alleged violations of road laws and capture an image of the offending vehicle. The driver of the vehicle can then be fined and receive demerit points. Unregistered vehicles and companies that fail to nominate a driver for a road safety offence can also be fined using evidence obtained from road safety cameras.

1.3.1 Camera types and purposes

There are four types of road safety camera used in Victoria, for the following purposes:

- Fixed highway speed cameras—used to deter drivers from speeding on a discrete length of road. As such, they are targeted to black spots and locations where a crash would have very serious consequences. They are used on major arterial roads, freeways and in tunnels and in circumstances where it is not safe or practical to undertake other types of speed enforcement. While freeways are generally well designed and inherently safer roads, the high traffic volumes and travel speeds increase the risk of crashes and their severity. Camera locations are typically known and published on the Cameras Save Lives' website.

- Fixed intersection speed/red-light cameras or red-light only cameras—used to create a location-specific effect on red-light running, and speeding where relevant, at dangerous intersections. Intersections have a higher crash risk than other parts of roads. Victoria is one of the few jurisdictions to use combined speed/red-light cameras.

- Mobile speed cameras—used to create the perception among drivers that they can be caught anywhere, any time. To do this, mobile cameras are moved around many sites. The threat of detection and punishment across the road network is intended to persuade drivers to reduce their speed consistently, not just at specific locations.

- Point-to-point speed cameras—used to reduce speeding over a stretch of road rather than at one specific location. Speeding is measured by recording how long a vehicle takes to pass through a zone, calculating the average speed and comparing it to the speed limit.

Road safety cameras are used in all other Australian states and territories, to varying degrees. Most jurisdictions have both mobile and fixed cameras. Historically, Victoria has had a more intensive road camera program than other Australian jurisdictions. It was the first Australian jurisdiction to implement a point-to-point camera system applicable to all road users.

1.3.2 Acceptance of the camera program

The community and media have shown significant interest in the use of cameras for road safety enforcement, voicing concerns about the appropriateness of camera use, and the integrity and fairness of the program.

Elements of the community and media question the main purpose of the camera program. Some allege that it is about revenue-raising rather than road safety. A 2009 survey of Victorians by the then Australian Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Local Government found that 59 per cent of respondents believed that fines for speeding are mainly intended to raise revenue'.

Major system faults erode public confidence, and receive significant media coverage. The failure of the fixed camera system on the Western Ring Road in 2003, and the nine incorrect fines issued from the Hume Freeway point-to-point cameras in 2010 are cases in point.

Recent studies of social acceptability show that excessive speeding is considered socially unacceptable and on a par with drink driving. However, the studies also suggest there is greater acceptance of lower-level speeding of up to 10 km/h over the limit and that it is perceived as lower-risk behaviour.

1.3.3 Fines and revenue

During 2009–10, 1 156 673 speeding infringements and 147 505 red-light running infringements were issued from road safety cameras.

The fine structure for 2011–12 is shown in Figure 1D. Legislation determines that the value of a speeding fine depends on the number of kilometres above the speed limit the vehicle was travelling.

Figure

1D

Penalties for road safety infringements

| Traffic offence | Fine ($) | Demerit points | Automatic suspension |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exceeding the speed limit in a car by: | |||

| Less than 10 km/h | 153 | 1 | n/a |

| 10 km/h – 15 km/h | 244 | 3 | n/a |

| 16 km/h – 24 km/h | 244 | 3 | n/a |

| 25 km/h – 29 km/h | 336 | 4 | 1 month |

| 30 km/h – 34 km/h | 397 | 4 | 1 month |

| 35 km/h – 39 km/h | 458 | 6 | 6 months |

| 40 km/h – 44 km/h | 519 | 6 | 6 months |

| 45 km/h or more | 611 | 8 | 12 months |

| Red-light running | 305 | 3 | n/a |

| Unregistered vehicle | 611 | n/a | n/a |

Note: The fines and demerit points are the same for exceeding the speed limit by 10–15 km/h and 16–24 km/h. These are presented separately because they have different review criteria.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information from the Cameras Save Lives' website, Department of Justice.

Revenue from road safety cameras represented about 0.47 per cent of the total general government revenue in 2009–10. This proportion is consistent with the last three financial years where revenue from cameras has represented around 0.50 per cent of total general government revenue.

In 2009–10, revenue from fines for speed and red-light running (excluding police patrols) was $211.3 million. Of this:

- $116.8 million (55percent) was from fixed cameras

- $92.5million (44 per cent) was from mobile cameras

- $2.0 million (1percent) was from point-to-point cameras.

Additionally, $18.3 million of revenue in 2009–10 was derived from fines issued for unregistered vehicles and companies failing to nominate a driver.

Drivers can ask to have their infringements withdrawn and Victoria Police has the discretion to issue an official warning instead. In 2010–11, 50 342 fines were withdrawn and an official warning issued in its place, which represents around $8.4 million.

All revenue raised by road safety cameras is allocated to the Better Roads Victoria Trust Account. The account funds projects to improve roads and thereby:

- improve the efficiency of roads

- improve safety for all road users

- reduce transport costs for business

- improve access for local communities.

1.4 Legislation and administration

Road safety rules and the use of road safety cameras are legislated under the Road Safety Act 1986, and the Road Safety (General) Regulations 2009. They cover:

- the general obligations of road users for responsible road use

- penalties for traffic infringements

- devices, systems and procedures for obtaining evidence of vehicle speed and other traffic offences.

1.4.1 Road safety partners

Four agencies work together on road safety policy, including developing and implementing both phases of arrive alive:

- VicRoads

- the Department of Justice

- Victoria Police

- the Transport Accident Commission.

VicRoads

VicRoads is the statutory authority that administers the Road Safety Act 1986. It manages the public road infrastructure, including building new roads, maintaining the road network, and implementing road safety infrastructure projects. VicRoads sets speed limits, manages the registration and driver licensing databases, and the crash statistics database, which is used to report the road toll.

VicRoads is also responsible for developing road safety policy and is the lead agency in developing the road safety strategies and supporting action plans.

Department of Justice

The Department of Justice's Infringement Management and Enforcement Services unit is responsible for delivering and monitoring the road safety camera program, which includes both fixed and mobile cameras. The unit engages contractors to:

- supply and maintain equipment, including cameras

- evaluate and test sites for fixed road safety cameras

- manage and operate mobile road safety cameras

- certify the accuracy of speed measurement devices

- process and verify the evidence collected from fixed and mobile cameras, including photographs

- manage the issuing of an approved infringement notice.

The unit manages these contracts and assures performance quality. It has other functions, including involvement in site selection for fixed road safety cameras.

Victoria Police

Victoria Police is responsible for enforcing the road safety laws, including incidents recorded by road safety cameras. Before an infringement can be issued, Victoria Police further verifies the accuracy and validity of infringements. It also manages reviews of infringements and is responsible for identifying mobile camera sites and allocating the mobile camera hours.

Transport Accident Commission

TAC funds treatment and benefits for people injured in road crashes. It also promotes road safety through campaigns and road infrastructure projects aimed at reducing road trauma. In coordination with the other road safety agencies, it develops public campaigns targeting road safety issues such as drink driving and speeding.

TAC funds road safety infrastructure projects managed by VicRoads. These projects are part of the arrive alive 2008–17 strategy. In 2009–10, TAC spent $86.5 million on road safety infrastructure improvements.

1.5 Previous reviews

In August 2004 the former Auditor-General, Ches Baragwanath AO, completed an Inquiry into the Western Ring Road Fixed Digital Speed Camera System Contract and its Management. The inquiry was conducted in response to concerns regarding the accuracy of fixed cameras.

While highly critical of the failure to scrutinise the financial viability of the contractor, the choice of detection system, the inadequate contract supervision and unclear corporate governance arrangements, the report was unequivocal in its endorsement of safety cameras as having a positive impact on road safety:

‘The widespread use of safety cameras in Victoria marked the beginning of significant reductions in road trauma in Victoria. It also represented a shift away from traditional labour intensive methods of traffic law enforcement towards the use of semi-automated techniques. Scientific evaluations of these new techniques have demonstrated the positive contribution of automated enforcement technologies in reducing road trauma.’

In July 2006 VAGO tabled Making travel safer: Victoria's speed enforcement program, which found that cameras were directed at reducing road trauma, not raising revenue, and they had contributed to reductions in road trauma. It also found that quality control measures give sufficient assurance that infringements from cameras are not issued to motorists who comply with road rules.

1.6 Audit objective and scope

The audit objective was to determine whether the road safety camera system is effective. The audit assessed:

- whether the road safety program is current and reflects better practice

- whether tactical deployment of cameras optimises road safety outcomes

- whether the integrity of the road safety camera systems is adequately assured

- the extent to which cameras, as part of the overall road safety program, contribute to achieving road safety outcomes.

The audit did not examine road enforcement conducted directly by Victoria Police, as this is not part of the camera program.

1.7 Report structure

The rest of this report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines the rationale for the road safety camera program

- Part 3 examines the siting of cameras for road safety outcomes

- Part 4 examines the accuracy of the camera system

- Part 5 examines the validity of infringements issued

- Part 6 examines the communication strategy for the program.

1.8 Audit method and cost

The audit was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. The total cost of the audit was $570 000.

2 Rationale for the road safety camera program

At a glance

Background

Road safety cameras have been used in Victoria since 1983. Fixed and mobile cameras are used at intersections, on freeways, in tunnels and in metropolitan and residential areas. The road safety camera program is part of the broader arrive alive 2008–2017 road safety strategy. Drivers caught speeding or running red lights can receive an infringement notice to deter them from these behaviours.

Conclusion

There is a sound rationale for using road safety cameras as part of a broader road safety strategy to improve road safety outcomes and reduce road trauma. Cameras have been repeatedly shown to be effective in reducing crashes and speeding. While cameras cannot differentiate between road user groups with different levels of risk of road trauma, they are appropriately complemented by targeted non-camera approaches within the arrive alive 2008–2017 strategy.

Findings

- Road safety cameras are part of a broader road safety strategy that is based on recognised road safety principles of the Safe System approach.

- Evidence from Australian and international jurisdictions strongly supports the use of road safety cameras to reduce road trauma.

- While point-to-point cameras are a sound concept, there is less evidence available about their effectiveness in improving road safety. Similarly, there are also gaps in the research on the effectiveness of fixed cameras on freeways.

- Cameras cannot identify a large proportion of speeding motocyclists.

Recommendations

- The Department of Justice should continue its focus on evaluation, though priority should be given to assessing the effectiveness of both fixed freeway cameras and point-to-point cameras.

- VicRoads, in partnership with the Department of Justice, Victoria Police and the Transport Accident Commission, should address the gap in speed enforcement for motorcyclists.

2.1 Introduction

Road safety cameras have been used in Victoria since 1983 and form a part of the current road safety strategy arrive alive 2008–2017. Drivers receive infringements if they are detected speeding or running a red light. This is intended to deter them from behaving in an unsafe manner and reduce the likelihood of contributing to increased road trauma.

This section examines whether there is a sound rationale, from a road safety perspective, for using cameras.

2.2 Conclusion

There is a sound rationale for using road safety cameras as part of a broader road safety strategy to improve road safety outcomes and reduce road trauma. Cameras have been repeatedly shown to be effective in reducing crashes and speeding. While cameras cannot differentiate between road user groups with different levels of risk of road trauma, they are appropriately complemented by targeted non-camera approaches within the arrive alive 2008–2017 strategy.

2.3 Rationale for a Safe System approach

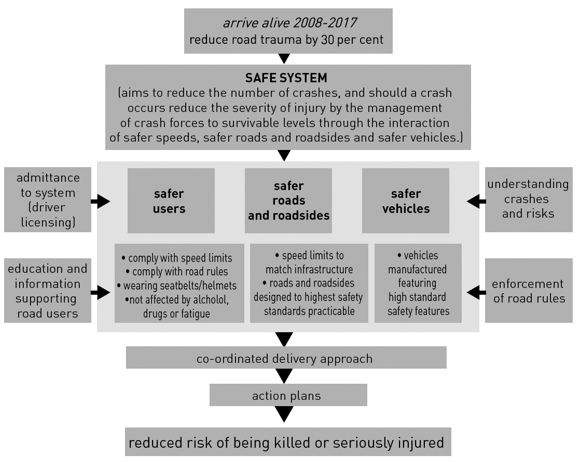

Road safety cameras are part of Victoria's road safety strategy, arrive alive 2008–2017. The strategy has three focus areas: safer roads and roadsides, safer vehicles, and safer road users. To improve each of these focus areas, the strategy describes a range of measures. Figure 2A shows the strategy's focus areas and some of its associated measures, including road safety cameras.

Figure

2A

The arrive alive 2008–2017 strategy

and its components

Source: VicRoads.

The design of the strategy is soundly based on the principles of the Safe System approach. This approach recognises that prevention efforts notwithstanding, road users will still make mistakes and crashes will still occur. The basic method of the Safe System approach is to make sure that in the event of a crash, the physical impact is lessened to reduce the risk of death or serious injury.

This approach has been implemented throughout Australia and is the basis of the National Road Safety Strategy 2011–2020. It has been implemented internationally including in the leading road safety jurisdictions of Sweden and the Netherlands. The approach is recognised by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, the World Health Organisation and the United Nations as the optimal approach for improving road safety and achieving a zero road toll.

Using this approach, the road safety partners developed arrive alive 2008–2017 based on existing research and widespread consultation with road safety experts. The Monash University Accident Research Centre (MUARC) was engaged to develop a model that estimated the road safety outcomes of various policy initiatives. This model heavily informed the development of the strategy and has been used to track its progress. This model has formed the basis for road safety strategies in other Australian jurisdictions.

The previous version of the strategy, arrive alive 2002–2007, focused on and achieved considerable gains in improving road user behaviour through initiatives including enforcement and education. In recognition of the fact that additional significant gains are likely to be achieved through other strategies, the road safety partners placed a stronger focus on other areas of the Safe System approach in developing arrive alive 2008–2017, in particular safer roads and roadsides. The MUARC model forecast that considerable gains in road safety could be made through investment in road and roadside infrastructure, and $650 million was allocated to these initiatives. Nevertheless, the strategy continued to emphasise the importance of maintaining and further improving safe road-user behaviour.

2.4 Rationale for improving road-user behaviour

One of the three areas of focus of the arrive alive 2008–2017 strategy is road-user behaviour. There is a sound basis for focusing on improving road-user behaviour to achieve road safety outcomes, because of the relationships between unsafe behaviours such as speeding and red-light running, and crash likelihood and severity. These relationships have been well established by road safety research and there is a sound basis for pursuing this policy goal.

There is a causal relationship between:

- speeding and the likelihood of a crash occurring

- speed and the severity of a crash when it does occur

- red-light running and the likelihood and severity of crashes.

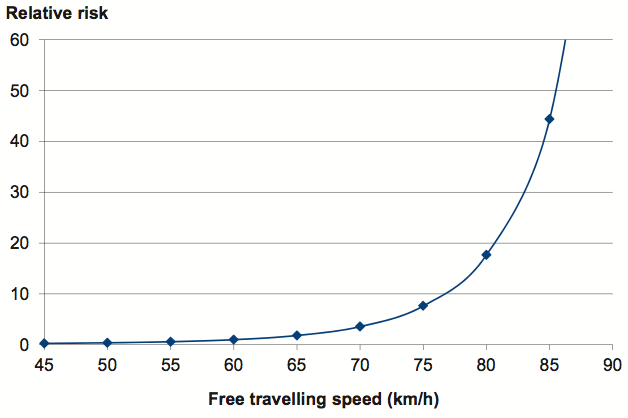

Speed and likelihood of a crash

The link between speed and the likelihood of a crash is strongly supported by research evidence.

A seminal study conducted in 2001 by the University of Adelaide found that in rural areas in South Australia, the risk of crash doubled with a 10 km/h increase in speed in 100 km/h zones. Another study by the same university conducted in 2002 found that in metropolitan areas, when travelling between 60 and 80 km/h, the vehicle occupants' risk of a fatality or serious injury crash doubled for each 5 km/h increase in travelling speed. As such, small increases in speed have significant impacts on crash risk along with more excessive speeding, as shown in Figure 2B.

Figure

2B

Free travelling speed and the risk of involvement in a crash

resulting in fatality or serious injury in a 60 km/h speed zone

relative to travelling at 60 km/h

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data from the Road Accident Research Unit, University of Adelaide, 2002.

This research has been repeatedly validated by other researchers, including a report conducted in Sweden in 2004 which found that a 5 per cent increase in speed led to an increase in all injury crashes of about 10 per cent and an increase in fatal crashes of around 20 per cent.

Speed and severity of a crash

There is a causal link between speed and severity of a crash, because when a crash occurs, the greater the travelling speed, the greater the impact energy which is transferred to the road users involved.

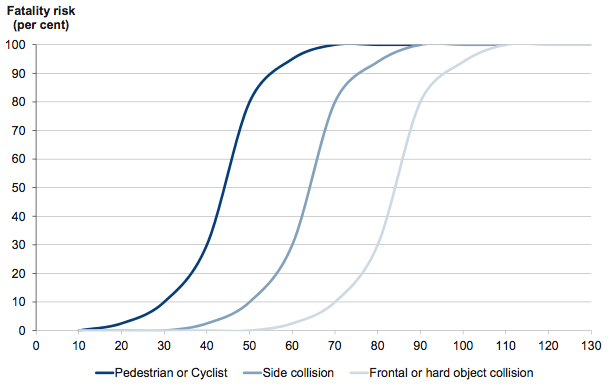

In a head-on crash, the likelihood that occupants will survive decreases rapidly if the vehicle is travelling above 70 km/h. For side-impact collisions, the chance of survival decreases rapidly above 50 km/h. While helmets give some protection to motorcyclists and cyclists, the likelihood that a pedestrian will survive being hit by a vehicle decreases rapidly if the vehicle is travelling over 30 km/h. This further demonstrates the increased risk of death with small increases in speed. Figure 2C shows the relationship between impact speed and likelihood of fatality for different road users and crash types.

Figure

2C

Relationship between impact vehicle speed and chance of fatality for different

road users and crash types

Source: VicRoads.

Red-light running and road trauma

Red-light running is strongly linked with crash risk and severity due in part to the nature of the crashes that tend to occur at intersections.

For intersection crashes, the high incidence of road trauma is partly because side‑impact collisions and speed are often involved. As noted above, side‑impact collisions are particularly dangerous to the vehicle occupants because the body of the car offers less protection than in head-on or rear-end crashes. In a side‑impact collision, the car cannot provide sufficient protection above speeds of 50 km/h.

2.4.1 Rationale for enforcement

Given the strong evidentiary links between speeding and red-light running and road trauma, this has been an area of focus for the strategy. One of the ways it attempts to modify these behaviours is through enforcement. Road safety cameras are one mechanism of enforcement, alongside police patrolling.

There is a sound rationale for attempting to improve driver behaviour through enforcement. Criminological research shows that to deter people from illegal behaviours, the perceived risk of detection and the level of punishment must exceed the potential gains of these behaviours. Increasing the level of enforcement will increase the perceived risk of detection and lead to reductions in illegal behaviour. Therefore, as for other illegal behaviours, enforcement is a critical element for reducing unsafe road-user behaviours. arrive alive 2008–2017 is consistent with this approach and adopts enforcement to change road-user behaviour as part of its road safety management.

The extent to which enforcement is effective depends on the level of perceived risk that it can create. To create a high level of perceived risk, a significant number of road users and a significant amount of the road network must be exposed to enforcement. If enforcement is too small, is reduced, or is removed, the perceived risk will fall and there will be less deterrence. As such, to be effective, enforcement activities must be ongoing and of sufficient scale.

2.4.2 Evidence base for using road safety cameras

There is a strong argument for using road safety cameras to change driver behaviour and reduce road trauma.

Road safety cameras have been evaluated extensively and the body of research has consistently found that cameras improve road safety and reduce road trauma. Key studies including Victorian evaluations are discussed below.

It is inherently difficult to precisely quantify the direct effects of safety cameras on road safety across the road network because there are many different factors that influence road safety, and most evaluations will measure the total impact of the efforts. However, the research shows that, while the precise contribution cannot yet be determined, cameras have resulted in significant improvements in road safety and their use as part of a broader road safety strategy is justified.

Meta-analysis of evaluations

In 2010 a meta-analysis of 35 evaluations from Australian and international jurisdictions was conducted by the Cochrane Collaboration, a group that conducts systematic reviews of evaluations and interventions in health-related fields.

A meta‑analysis combines the research findings of related studies on a particular subject to produce a more statistically powerful conclusion. To be included in the meta‑analysis, each evaluation must satisfy a range of criteria that check whether the evaluation meets methodological standards. For example, to make sure the evidence used was the highest possible quality, the meta-evaluation included only studies with before–after trials with control or comparison areas. Other criteria assessed the studies based on types of participants included, interventions applied, and outcome measures used. Consequently, there can be a high degree of confidence in the conclusions of a meta-analysis.

The Cochrane Collaboration's meta-analysis strongly supported the use of road safety cameras for reducing road fatalities and injuries. It found that road safety cameras reduce:

- the frequency of all crash types, particularly those resulting in fatalities and serious injuries

- the proportion of drivers travelling over the speed limit

- average speeds.

Evaluations in Victoria and other jurisdictions

Road safety cameras have been extensively evaluated in Victoria and other Australian and international jurisdictions. These evaluations have consistently found that the use of road safety cameras is associated with:

- reductions in crash frequency and severity

- reductions in excessive speeding

- increases in compliance with speed limits.

Evaluation of Victoria's road safety camera program has primarily been conducted by MUARC. The most recent Victorian road safety camera initiative to be evaluated was the new fixed intersection cameras, which both measure speed, and detect red‑light running. It is the first major evaluation of combined speed and red-light camera technology—previous evaluations have only assessed either red-light or fixed speed cameras.

The evaluation, completed in 2011, examined the impact of the introduction of 77 speed/red-light cameras installed across Victoria. This relatively large number of sites allowed the evaluation to come to a more robust conclusion. Examining the before and after effects of a single site cannot give as robust a result, because it might be affected by chance. By having a larger sample size, there can be greater confidence that any differences observed are due to the cameras.

The evaluation found that, on average, after cameras were installed at these sites, there was a statistically significant reduction in casualty crashes of 47 per cent on the leg of the intersection where cameras were situated. The evaluation also examined the rate of crashes for all roads leading to the intersection, not just the road where the camera is. It found there was a 26 per cent fall in casualty crashes for these roads. This demonstrates that the cameras are having a positive effect on road safety even on drivers who are not directly exposed to the camera. Additionally, there was a 44 per cent fall in right-turn crashes, where two vehicles hit at a right angle, which is a particularly serious type of crash as the vehicle occupants have less protection.

The evaluation estimated that, across the 77 intersections, the cameras had led to reductions of 17 fatal or serious injury crashes and 36 minor injury crashes per year. Based on these outcomes, the evaluation recommended that the use of speed/red‑light cameras at intersections should be continued and expanded in Victoria.

VAGO examined the MUARC evaluation to determine the level of reliance that could be placed on its results and found that:

- The methodology was sound, with a large number of camera sites appropriately compared to a larger sample of control sites, over extended pre- and post‑camera periods.

- The design assessed all crashes at the intersections, as well as those most likely to be affected by the initiative such as right-angle, right-turn and rear-end crashes. It has been common for evaluations of this type to only assess crashes that occur on the leg of the intersection where the camera is situated and only consider specific crash types.

- Findings are consistent with findings of evaluations of independent red-light cameras and fixed speed camera programs in other jurisdictions.

- Conclusions drawn based on the findings and results were appropriate.

As such, there can be a high level of confidence in the results of the evaluation.

These results, supporting the use of cameras to reduce road trauma, are consistent with the findings of other published evaluations of other aspects of the Victorian camera program. Examples include evaluations of:

- fixed cameras—fixed speed cameras were first used in Victoria in 2000, in the Domain Tunnel on the Monash Freeway. MUARC found that, in the tunnel, the cameras contributed to a fall in average speeds from 75.1 km/h to 72.5 km/h. It also found that the proportion of vehicles travelling over the speed limit fell from 17.5 per cent to 6 per cent.

- mobile cameras—in December 2001, a package of road safety initiatives that focused on the intensification of mobile camera operations was introduced. Initiatives included a 50 per cent increase in the number of mobile camera hours, a lower speed detection threshold, reduction of the default speed limit in residential areas to 50 km/h, and the Wipe Off 5' campaign. MUARC found a clear reduction in the number of casualty crashes attributable to the package, particularly in 40, 50 and 60 km/h zones. The strongest results were in the last sixmonths of the evaluation, when all of the initiatives had been implemented. Between July and December 2004, there was a highly statistically significant fall of 26.7 per cent in fatal crashes and a 10 per cent fall in casualty crashes.

Examples of findings from studies in other jurisdictions are shown in Figure 2D. These findings are consistent with the Victorian evaluations.

Figure 2DEvaluations of road safety cameras in other jurisdictions

New South Wales

In 2005, an evaluation of New South Wales' fixed speed cameras was conducted by ARRB Transport Research. The evaluation examined changes in crashes and speeding at 28 camera sites on metropolitan and rural freeways and highways. Along the stretches of road where the cameras were located, there was an 89.8 per cent fall in fatal crashes. The percentage of vehicles exceeding the speed limit fell by 71.8 per cent and the percentage of vehicles speeding by more than 10 km/h fell by 87.9 per cent. Effects on speed and road trauma lasted up to 4 km from the camera sites.

Queensland

In 2009, MUARC evaluated the performance of Queensland's mobile speed camera program. The evaluation found a 40.4 per cent fall in fatal and serious injury crashes, 50.7 per cent fall in crashes requiring medical treatment and a 31.2 per cent fall in all crashes.

United Kingdom

In 2005, a national evaluation of 502 fixed camera sites and 1 448 mobile camera sites was completed. The evaluation found that fatal and serious injury crashes fell by 42.1 per cent. There was an overall fall in free speeds and a 31 per cent fall in the number of vehicles exceeding the speed limit.

France

In 2003, France introduced road safety cameras to combat a high road toll and by 2007 it had 2 000 cameras. Between 2002 and 2005, fatalities on French roads fell by over 30 per cent. Fatal and serious injury crashes fell by between 40 and 65 per cent within 6 km of camera sites. Average speeds fell by 5 km/h and the number of drivers speeding by more than 30 km/h fell by 80 per cent.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on reports by ARRB Transport Research, Monash University Accident Research Centre, Department for Transport (United Kingdom), and World Health Organisation.

Gaps in the evidence base

Throughout the history of Victoria's road safety camera program, there has been a strong emphasis on evaluation of the impact of cameras on road safety outcomes, in particular intersection cameras. Compared to other aspects of the program, however, the effectiveness of Victoria's fixed speed cameras on freeways has not been extensively evaluated. As noted in Figure 2D, evaluations in other jurisdictions have found that fixed freeway cameras improve road safety outcomes and reduce road trauma.

Cameras are sometimes installed at the time of freeway construction as a preventative measure in anticipation of predicted road trauma. It is inherently difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of such cameras, as it is not possible to make a before and after comparison. However, alternative evaluation approaches are possible, such as assessing freeways against different comparable freeways, or determining whether cameras have had a deterrent effect across the entire freeway or only near the location of the cameras.

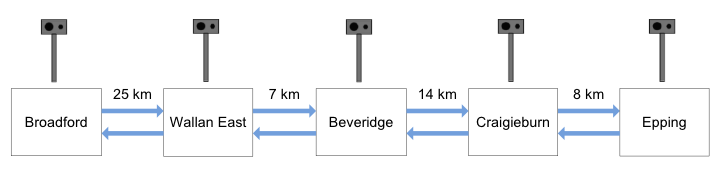

Point-to-point cameras are a recently-developed technology, introduced in Victoria on the Hume Freeway. Cameras are placed at either end of a zone. Using numberplate‑recognition technology, these cameras record how long it takes a vehicle to pass through a zone, calculate the average speed and compare it to the speed limit. The four zones on the Hume Freeway are shown in Figure 2E.

Figure 2EFour point-to-point camera zones on the Hume Freeway

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Department of Justice documentation.

As a concept, point-to-point cameras are soundly-based. The use of point-to-point cameras was endorsed in the National Road Safety Strategy 2011–2020. By measuring average speed across a stretch of road, point-to-point cameras target persistent speeding and, therefore, discourage drivers from reducing their speed only in the area surrounding a fixed camera. This technology was initiated as part of the first arrive alive 2002–2007 strategy with the intention that it would be expanded if found to be successful.

At this stage, as it is a newer technology, research into the use and effectiveness of point‑to-point cameras in improving road safety is not as advanced as for other road safety camera technology. International evaluations have shown positive results, with increased compliance with speed limits, reductions in travelling speeds and reductions in crash rates including fatal and serious injury crashes. However, there are reservations about the rigour and independence of this research.

It is important that Australian evaluations into point-to-point cameras are conducted; however, none have been published yet. MUARC has submitted an evaluation proposal to assess the effectiveness of the point-to-point system on the Hume. However, although they are fully installed, Victoria's point-to-point cameras are not currently operational. They were turned off in 2010 after a software fault was detected and have not yet been reactivated, therefore the evaluation cannot proceed. This is discussed in Part 4.

2.4.3 Targeting at-risk road user groups

While cameras are effective at changing road-user behaviour and reducing road trauma, they cannot differentiate between road users who have different risks of experiencing road trauma.

arrive alive 2008–2017 recognises that some road-user groups are more at risk than others. In particular, the following user groups are identified in the strategy as requiring tailored approaches to improve their safety:

- young drivers

- older drivers

- motorcyclists

- pedestrians

- cyclists

- heavy vehicle drivers

- public transport users

- country road users.

For road users who are not subject to the camera program, such as cyclists, it is appropriate that cameras are part of a broader strategy that has initiatives to differentiate and provide specific approaches for higher-risk groups.

Camera coverage of motorcyclists

Motorcyclists and pillion passengers are approximately 30 times more likely to sustain a fatal or serious injury per kilometre travelled than other vehicle occupants.

There are some road safety cameras that, because of the direction they face, can record only front numberplates. However, motorcycles are not required to have front numberplates. Road safety camera incidents rejected because of the lack of a numberplate on a motorcycle represented 52.4 per cent of all non-plate' rejections in 2009–10, whereas motorcycles make up only 4 per cent of registered vehicles. As a consequence, the potential for the camera program to deter motorcyclists from speeding is substantially reduced.

If motorcycles could be identified by all cameras, it would be possible to evaluate any changes in road safety outcomes for motorcyclists in comparison to an established baseline at the time of the introduction of the initiative.

Recommendations

- The Department of Justice should continue its focus on evaluation, though priority should be given to evaluating the effectiveness of both fixed freeway cameras and point-to-point camera systems.

- VicRoads, in partnership with the Department of Justice, Victoria Police and the Transport Accident Commission should address the gap in speed enforcement for motorcyclists.

3 Siting cameras for road safety outcomes

At a glance

Background

Fixed road safety cameras are used in a variety of locations, and decisions on where to site them are made by the Fixed Camera Site Selection Committee. Every month, 9 300 mobile camera hours are rostered across approximately 2 000 approved sites by local police highway patrols. Camera sessions are conducted by the mobile program provider, contracted by the Department of Justice.

Conclusion

Siting of fixed and mobile cameras is clearly based on road safety outcomes. While siting could be strengthened to optimise these outcomes, the deployment criteria used to identify and approve sites have a clear road safety justification for camera placement. Rostering practices have not maximised the deterrence effect of mobile cameras with, in some instances, discernible patterns in their deployment and gaps in coverage at night.

Findings

- The criteria for siting fixed cameras are soundly based on crash risk, and all decisions since they were developed have adhered to these criteria.

- The Fixed Camera Site Selection Committee prioritises candidate intersection sites systematically, but not freeways and highways.

- Using deployment criteria for siting mobile cameras limits the extent to which they create general rather than location-specific deterrence from speeding. The effectiveness of this approach has not been evaluated.

- Gaps in coverage and discernible patterns in rostering of mobile cameras limit their effectiveness.

Recommendations

- Victoria Police should pilot and evaluate alternative approaches for mobile camera site selection and rostering, such as random rostering.

- The Department of Justice should review the impact of publishing the list of weekly rostered sites for mobile cameras on road safety.

- Victoria Police should identify a minimum number of required mobile sites.

- Victoria Police should identify a minimum number of hours to be rostered at night.

3.1 Introduction

Given limited resources, the number and types of cameras available should be deployed in the way that is most likely to achieve the best road safety outcomes possible.

Currently, there are 171 operational fixed camera sites. A further 32 fixed cameras are installed but not yet operational, and the 10 point-to-point cameras on the Hume system remain deactivated. Decisions on where to site these cameras are based on recommendations made by the Fixed Camera Site Selection Committee, which is chaired by Victoria Police. Additionally, there are 85 specially-designed mobile digital speed camera cars, which are deployed across approximately 2 000 Victoria Police approved sites. Victoria Police roster 9 300 camera hours a month to these sites.

This Part examines the appropriateness of site selection for fixed and mobile cameras and monthly rostering of mobile cameras to determine whether deployment of these cameras is maximising road safety outcomes.

3.2 Conclusion

Siting of fixed and mobile cameras is clearly based on road safety outcomes. While siting could be strengthened to optimise these outcomes, the application of deployment criteria used to identify and approve sites for cameras have a clear road safety justification for camera placement.

Rostering practices have not maximised the deterrence effect of mobile cameras with, in some instances, discernible patterns in their deployment and gaps in coverage at night.

3.3 Siting fixed cameras

The 2006 VAGO performance audit Making travel safer: Victoria's speed enforcement program found that guidelines for selecting fixed cameras sites were not sufficiently detailed, and recommended that more detailed fixed camera site selection criteria be developed.

In 2007, Victoria Police and the Department of Justice (DOJ) established the Fixed Camera Site Selection Committee (the Committee). The Committee's terms of reference included developing and implementing more detailed site selection guidelines for fixed cameras.

VAGO assessed whether criteria:

- were soundly based

- were applied in subsequent site selection

- helped decision-makers prioritise candidate sites.

3.3.1 Basis for the criteria

Fixed cameras create localised changes in driver behaviour, and their effect is therefore likely to be most beneficial in places where problems relating to crashes and speeding are confined to an immediate area. Given this, there is a sound argument for placing fixed cameras at locations that have known crash risks or a demonstrated speeding problem.

To inform the siting of fixed cameras, the Committee developed criteria in 2007. The criteria are soundly based because they relate to the crash risk of the location and have a clear relationship with crash likelihood, crash severity, or both. This is described in Figure 3A.

Figure 3A Fixed camera site selection criteria and analysis of the relationship with crash risk| Criterion | Description | Analysis of relationship with crash risk or severity |

|---|---|---|

| Casualty crash history | The number of crashes at a particular location that resulted in fatalities or serious injuries, over three years. | There are locations that have a higher number of crashes than others, and where crashes have had a more serious outcome. These can be identified by analysis of crash statistics. These trends can be used to predict future crashes. |

| Driver behaviour | Reports from local police, councils, Members of Parliament and the community about driver behaviour, such as speeding at a particular location. | Research shows that speeding is strongly linked with crash likelihood and severity. This criterion allows decision-makers to place a camera at a particular location where driver behaviour has been identified as risky and is increasing the likelihood of a crash occurring, without having to wait for a history to develop. Such reports are substantiated by the Committee and the site is assessed before it is allocated a camera based on this criterion. |

| General location suitability and risk factor | Assessment of whether the site has existing road safety systems, the proximity of schools or other amenities, pedestrian use of the intersection, and whether there is the potential for significantly high speeds or a catastrophic crash. | While some locations may not have a crash history or high crash likelihood, the outcome of a crash at that particular location would likely be catastrophic. For example, if there was a crash in a tunnel it would likely involve multiple vehicles and be very difficult for emergency vehicles to access. Similarly, while freeways are well-designed, high traffic volumes and speeds increase the likely severity of a crash. Additionally, certain road user groups are particularly vulnerable, including pedestrians and children in school zones. Speed management in locations where these user groups are common is critical. |

| Road capacity | Assessment of whether the location links to other road systems that are potentially high speed areas, given the road and lane types. | The design of some road systems and linkages with other roads can enable some road users to speed excessively. This is particularly the case on freeways. Similar to the driver behaviour' criterion, this criterion allows placement of a camera at a location that does not have an established crash history but where there is evidence of a higher likelihood of crashing. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The Committee included a fifth criterion, relating to the technical suitability of a site, which establishes the feasibility of locating a camera at a particular site. There may be a strong justification for installing a camera at a particular site based on crash risk. However, this may not be possible or appropriate, due to other factors such as planned infrastructure projects, where installation of a camera would be a waste of resources if it were removed shortly after to allow for the construction of these projects. This criterion also evaluates the suitability of different technologies to different locations or road types. For example, variable speed limits along certain freeways may preclude the use of point-to-point technology, because this technology requires the measurement of average speed within the same speed zone.

3.3.2 Application of the criteria

Siting decisions for fixed cameras are required to meet at least one of the criteria in Figure 3A. Since the development of the criteria in 2007, there have been three siting decisions involving 38 fixed cameras. VAGO examined documentation surrounding these decisions and found that, for all these decisions, siting has met these criteria. This is shown in Figure 3B.

Figure 3B Fixed camera siting decisions since development of criteria

| Year | Siting decision | Basis for new site | Criterion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | Redeployment of a camera from an unused site to a new site | Reports from police, the local member and the community | Driver behaviour |

| 2008 | Redeployment of cameras from seven deactivated sites to new sites | Ranking based on crash history | Casualty crash history |

| 2009 | Installation of an additional 30 digital speed/red-light cameras at new sites | Ranking based on crash history and reports about driver behaviour | Casualty crash history; Driver behaviour |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In cases where a request for a camera was made, the Committee substantiated the validity of the request before deciding to site a camera in that location. For example, in one case a camera was placed at an intersection that did not then rank high on the crash statistics. However, a request was made for a camera because of a crash at the intersection in which two children were killed. The Committee examined the intersection and determined that there was a valid case for an intersection camera, due in part to the poor line of sight when approaching it.