Universities: 2014 Audit Snapshot

Overview

This report sets out the key outcomes from our financial audits of the eight universities and their 51 controlled entities for the year ending 31 December 2014.

Parliament, and the citizens of Victoria, can have confidence in the 2014 financial reports of the universities and their controlled entities, except for the following audit qualifications. Three entities, including the University of Melbourne and Deakin University, were qualified because their recognition of Commonwealth Government grants is a departure from Australian Accounting Standards. The qualifications on the universities have been in place for a number of years and are long standing issues that remain unresolved.

Including an adjustment for these qualifications, the universities produced a net surplus of $537.1 million for the 2014 financial year ($446.5 million for 2013). This large net surplus, when combined with their strong liquidity position, means most universities are considered to be low financial sustainability risks. However, there are some emerging longer-term sustainability risks that need to be monitored relating to the replacement or renewal of their assets.

Universities will need to respond promptly to any changes by the Commonwealth government to the funding model, so that they remain financially sustainable—as $2.7 billion of the universities' revenue came from the Commonwealth in 2014 ($2.6 billion in 2013), excluding capital grants.

As public bodies, universities are accountable for all public money spent and therefore must have the required documentation and support to demonstrate value for money was achieved. This was not the case when we looked at travel and accommodation spending by universities, which totalled $137 million in 2014. While there are frameworks in place to control this expenditure, these frameworks were not comprehensive, and our testing showed the policies and procedures were not routinely adhered to.

Universities: 2014 Audit Snapshot: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER May 2015

PP No 37, Session 2014–15

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Universities: 2014 Audit Snapshot.

This report details the outcomes of the 2014 financial audits of the eight universities and the 51 entities that they control.

It includes a review of the financial sustainability risks of the sector and the management of travel and accommodation expenses incurred by university staff.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

27 May 2015

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Simone Bohan—Engagement Leader Helen Grube—Team Leader Kevin Chan—Audit Senior Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Tim Loughnan |

This report sets out the key outcomes from our financial audits of the eight universities and their 51 controlled entities for the year ending 31 December 2014.

Parliament, and the citizens of Victoria, can have confidence in the 2014 financial reports of the universities and their controlled entities, except for the following audit qualifications. Three entities, including the University of Melbourne and Deakin University, were qualified because their recognition of Commonwealth Government grants is a departure from Australian Accounting Standards. The qualifications on the universities have been in place for a number of years and are long-standing issues that remain unresolved.

Including an adjustment for these qualifications, the universities produced a net surplus of $537.1 million for the 2014 financial year ($446.5 million for 2013). This large net surplus, when combined with their strong liquidity position, means most universities are considered to be low financial sustainability risks. However, there are some emerging longer-term sustainability risks relating to the replacement or renewal of their assets that need to be monitored.

The strong financial results of the universities stand them in good stead as they may be on the cusp of funding changes. The Commonwealth Government has proposed changes to the university funding model, which the Commonwealth Parliament is debating. As $2.7 billion of the universities' revenue came from the Commonwealth in 2014 ($2.6 billion in 2013), excluding capital grants, Universities will need to respond quickly and effectively to any changes to ensure that their business models continue to be financially sustainable.

As we conduct financial audits we raise and report to university councils, audit committees and management any weaknesses we find regarding their controls. However, there has not been timely action to address these as 40.3 per cent of the issues raised in 2013 remained unresolved in 2014. There should be active monitoring and resolution of issues by audit committees.

As public bodies, universities are accountable for all public money they spend and therefore must have the required documentation and support to demonstrate value for money was achieved. This was not the case when we looked at travel and accommodation spending by universities, which totalled $137.0 million in 2014. While there are frameworks in place to control this expenditure, these were not comprehensive, and our testing showed the policies and procedures were not routinely adhered to. These results are troubling and should concern those who govern universities.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

May 2015

Audit Summary

This report details the outcomes of the 2014 financial audits of the eight universities and the 51 entities that they control. It includes a review of the financial sustainability of the sector and the frameworks in place for managing travel and accommodation expenses incurred by university staff.

Conclusions

Financial reports prepared by the university sector were generally fairly presented with 56 entities receiving clear audit opinions. However, two universities and one controlled entity received qualified audit opinions indicating that their financial reports are not reliable or accurate in some respects.

Generally, the universities have a low financial sustainability risk, due to generating strong year-on-year surpluses and holding significant financial assets. However, there are longer-term financial sustainability risks emerging around asset renewal and replacement that need to be monitored.

Universities have policies and procedures in place for travel and accommodation expenditure but they are not comprehensive, and compliance with these policies and procedures is poor. Consequently, universities cannot demonstrate public money is spent prudently and to the benefit of the university.

Findings

Audit reports

Financial audit opinions were issued for 59 entities within the university sector for the financial year ending 31 December 2014. Parliament and the citizens of Victoria can have confidence in the 56 financial reports which received clear audit opinions.

Deakin University, the University of Melbourne and the Australian National Academy of Music Ltd all received a qualification relating to their recognition of grant revenues. Collectively, the revenue of these entities had been understated by $259 million at 31 December 2014.

In conducting our financial audits, we noted that the financial reporting internal controls at the eight universities, to the extent we tested them during our audit, were adequate for the preparation of each universities' financial report. Where weaknesses were identified these were reported to the university in an interim or final management letter so they can be addressed.

We raised 44 high and medium risk control-related issues in our 2014 management letters, with 63.6 per cent of those issues relating to the IT environment. Disappointingly, 40.3 per cent of the high- and medium-risk issues raised in prior years remain unresolved.

Financial sustainability risks

The eight universities, and their subsidiaries, generated a combined surplus of $537.1 million for the year ending 31 December 2014, after taking into account the audit adjustments arising from the qualifications. This, when combined with the universities' generally good liquidity position, means that the sector is in a healthy financial position and is a low financial sustainability risk in the short term.

Over the long term there are emerging risks the university sector should monitor. Our self-financing indicator shows there is a trend of declining available cash after operations to fund new assets and asset renewal. Coupled with this, spending on new assets and asset renewal has fallen from 2013 to 2014. Consuming more assets than you are renewing or replacing will have a cumulative adverse effect over time.

Our analysis of the financial sustainability risks of universities does not take into account proposed funding changes by the Commonwealth Government. During the 2014 financial year, the eight universities received 45 per cent of their revenue ($2 731 million) from Commonwealth Government grant funding, excluding capital grants. Universities will need to respond to any changes to the funding model promptly and efficiently to ensure they remain financially sustainable.

Travel and accommodation expenses

In 2014, the eight universities spent a combined $137.0 million on domestic and international travel. As public sector entities, universities need to demonstrate that value for money has been attained by any travel undertaken.

Universities should have sound procedures in place that set out what staff need to do before and after travel is undertaken, to ensure that travel is appropriately authorised and controlled.

While we observed policies and procedures to guide travel and accommodation expenditure at universities, not all policies covered areas of public interest, such as who can utilise frequent flyer points or what benefits are derived from travel undertaken. In particular, not all policies comprehensively include:

- a clear definition of personal travel, and a set of rules on cost sharing where personal travel is attached to business travel

- specific employees responsible for approving travel requests

- rules around the ownership and use of frequent flyer points

- guidelines for travel by companions, such as family members—including the allocation of costs

- restrictions on annual leave before and/or after business travel

- rules around the use of mini bars and associated reimbursements.

We tested a sample of transactions at all universities and concluded that compliance with policies and procedures are poor. We found that:

- travel diaries were not being completed

- approvals could not be sighted in three transactions selected

- details of travel taken did not agree with approved travel requests

- travel requests were not always approved by an appropriate authorised delegate.

The absence of supporting documentation acquitting the benefits obtained from travel means the universities cannot always demonstrate that value for money was achieved from this use of public funds.

Within the past four years only four of the eight universities have performed an internal audit review specifically looking at travel and accommodation. The findings of those reviews are consistent with our findings in this report, indicating no action had been taken to resolve the issues identified by internal audit.

Recommendations

That universities:

- address issues raised in audit management letters on a timely basis so that any weaknesses in the control environment identified are rectified promptly

- review asset replacement and renewal plans to assure themselves that spending on physical assets is sufficient to maintain service delivery

- review travel policies and procedures and ensure they are comprehensive and address areas of public interest including ownership and use of frequent flyer points

- strengthen the procedures covering monitoring and oversight of supporting documentation and acquittal of travel benefits

- implement regular reviews of compliance with travel and accommodation policies and procedures and take action where noncompliance is identified.

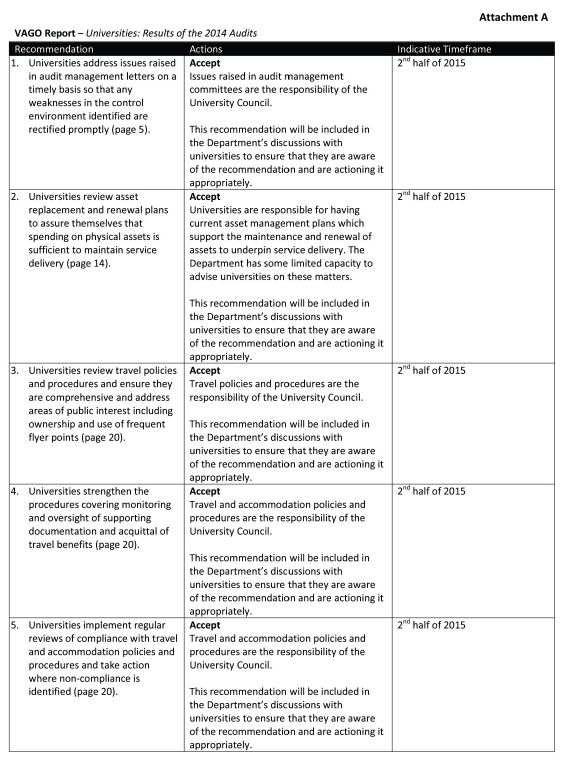

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with the Department of Education & Training, the Department of Treasury and Finance, and the eight universities throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report, or relevant extracts, to the department and other named entities, and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix F.

1 Context

1.1 Introduction

This report details the outcomes of the 2014 financial audits of the eight universities and the 51 entities that they control.

The report includes a review of the financial sustainability of the sector and the frameworks in place for managing the travel and accommodation expenses incurred by university staff.

1.1.1 Structure of this report

Figure 1A outlines the structure of this report.

Figure 1A

Report structure

|

Report part |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Part 1: Context |

Provides details of the audit opinions issued in the university sector for the financial year ending 31 December 2014, and discusses internal control issues identified during the audits. |

|

Part 2: Financial outcomes

|

Comments on the financial outcomes of the eight universities over the five-year period to 31 December 2014, including discussion of key financial issues impacting the sector's 2014 financial statements. Analyses the financial sustainability risk position of the eight universities at 31 December 2014. |

|

Part 3: Travel and accommodation expenditure |

Comments on the frameworks in place for managing travel and accommodation expenditure at the eight universities during the 2014 financial year. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost to prepare this report was $135 000.

1.2 Audits for the year ending 31 December 2014

1.2.1 Opinions issued

Independent audit opinions add credibility to financial reports by providing reasonable assurance that the information reported is reliable and accurate. A clear audit opinion confirms that the financial statements present fairly the transactions and balances for the reporting period, in accordance with the requirements of the relevant accounting standards and legislation.

Fifty-nine audit opinions were issued to the Victorian university sector for the year ending 31 December 2014. The financial audits of these entities were undertaken in accordance with Australian Auditing Standards. Details of each opinion issued are provided in Appendix A.

Of the eight universities, six clear audit opinions and two qualified audit opinions were issued. Of the subsidiary companies, 50 received clear audit opinions and one qualified audit opinion was issued.

Qualified audit opinions

A qualified audit opinion is issued when the auditor cannot be satisfied that the financial report is free from material error, or when the financial report is materially different to the relevant financial reporting framework.

For the year ending 31 December 2014, qualified audit opinions were issued to Deakin University, the University of Melbourne and the Australian National Academy of Music Ltd. All three were qualified because the recognition of Commonwealth Government grants was a departure from Australian Accounting Standards.

Each of these entities elected to treat Commonwealth grants as a 'reciprocal transfer', thereby only recognising revenue in the reporting periods when the associated services are provided. In the interim, unspent grants are recognised as a liability in the balance sheet. This means that if funding is received in December 2014, but it is not spent until May 2015, the revenue would only be recognised in the 2015 year.

However, this funding is 'non-reciprocal' in nature and should be recognised as revenue in the financial year it is received to accord to the requirements of the Australian Accounting Standards. For example, grant funding received in December 2014 should be recognised as revenue in the 2014 financial year because this is when the university gains control of the funds.

The University of Melbourne has received a qualified audit opinion because of this issue since their financial report for the year ending 31 December 2006; and Deakin University since 31 December 2007. The Australian National Academy of Music Ltd received qualified audit opinions for 2013 and 2014.

The qualified audit opinions detail the balances impacted by the differences in revenue recognition, and the impact this would have on the retained earnings of the entity at 31 December 2014. This is summarised in Figure 1B.

Figure 1B

Impact of qualifications in the university sector at 31 December 2014

|

Financial report line item |

Balance as per financial report |

Audit adjustment detailed in qualification |

Balance with audit adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

University of Melbourne |

|||

|

Other liabilities (current and non-current) |

$379.8 million |

$217 million decrease |

$162.8 million |

|

Australian Government Financial Assistance Income |

$1 006.5 million |

$9 million decrease |

$997.5 million |

|

Retained surplus |

$1 394.1 million |

$226 million increase |

$1 620.1 million |

|

Deakin University |

|||

|

Trade and other payables |

$218.4 million |

$28 million decrease |

$190.4 million |

|

Australian Government Financial Assistance Income |

$571.4 million |

$5 million decrease |

$566.4 million |

|

Retained surplus |

$1 178.1 million |

$33 million increase |

$1 211.1 million |

|

Australian National Academy of Music Ltd |

|||

|

Other liabilities |

$0.9 million |

$0.8 million decrease |

$0.1 million |

|

Australian Government grants |

$3.2 million |

$0.01 million increase |

$3.2 million |

|

Retained surplus |

$0.9 million |

$0.8 million increase |

$1.7 million |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In Part 2, our analysis of the financial sustainability risks of the universities at 31 December 2014 assesses these universities based on balances that include the above audit adjustments.

1.2.2 General internal controls

In conducting our financial audits, we noted that the financial reporting internal controls at the eight universities, to the extent we tested those controls during our audit, were adequate for the preparation of each university's financial report. Nevertheless, we identified a number of instances where important internal controls need to be strengthened.

Weaknesses in internal controls that are identified during an audit are reported to the council, audit committee and management through a formal letter, called a management letter. Typically, two management letters will be provided during a financial audit—an interim and a final.

In 2014, 44 high and medium control related issues were reported through interim and final management letters, across the eight universities. Figure 1C shows the reported issues by area and risk rating. The risk ratings are detailed in Appendix B.

Figure 1C

Reported issues by area and risk rating, 31 December 2014

|

Area of issue |

Risk rating |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

High |

Medium |

Total |

|

|

Revenue |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

Expenditure / Accounts payable |

0 |

4 |

4 |

|

Payroll |

0 |

2 |

2 |

|

Assets |

1 |

3 |

4 |

|

Liabilities |

0 |

2 |

2 |

|

IT Controls |

6 |

22 |

28 |

|

Other |

0 |

2 |

2 |

|

Total |

8 |

36 |

44 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Over 60 per cent of the reported issues related to the IT control environment. Eleven of these issues reported weaknesses relating to user access to IT systems—including poor password control and a lack of segregation of duties.

Universities are heavily reliant on the IT operating environment to help mitigate the risk that their financial statements are free from misstatement, and to ensure that appropriate controls exist over financial transactions. The consistency with which we observed IT control environment issues indicates that controls in this area could be strengthened.

Status of prior period issues

The status of internal control issues identified in prior period audits are presented to universities and their audit committees through the current years' interim management letters. These issues are monitored to ensure weaknesses identified in the control environments during previous audits are resolved promptly. Figure 1D shows the internal control issues identified in the prior period with the resolution status by risk rating.

Figure 1D

Prior period internal control issues—resolution status by risk

|

Resolution status |

Risk rating |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

High |

Medium |

Total |

|

|

Unresolved |

5 |

22 |

27 |

|

Resolved |

13 |

27 |

40 |

|

Total |

18 |

49 |

67 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Melbourne and Monash Universities still had unresolved high-rated issues raised in prior period audits.

While it is positive that all eight universities have started to address all the issues raised, the lack of timely resolution means that the control frameworks in place at these entities are not as effective as they should be. Management should seek to address all issues raised on a timely basis, to rectify any weaknesses in their control environment as soon as possible and to mitigate the risk of material errors occurring in their financial reports.

Recommendation

- That universities address issues raised in audit management letters on a timely basis so that any weaknesses in the control environment identified are rectified promptly.

2 Financial outcomes

At a glance

Background

This Part looks at the collective financial position of the eight universities as at 31 December 2014 and analyses the sector against five financial sustainability risk indicators.

Conclusion

The university sector is in a healthy financial position, posting surpluses year on year and continuing to hold large asset portfolios. While overall the university sector has been assessed as having a low financial sustainability risk, there are longer-term risks that need to be monitored.

Findings

- The university sector reported a net surplus of $537.1 million in 2014 ($446.5 million in 2013) which included $232.8 million of additional investment revenue by Monash University and the University of Melbourne as a result of investment portfolio restructures.

- There are emerging concerns in long-term financial sustainability risks as there has been a decline in the self-financing and capital-replacement indicators. This may indicate reduced spending on assets that could cause assets to fail over time.

Recommendation

That universities review asset replacement and renewal plans to assure themselves that spending on physical assets is sufficient to maintain service delivery.

2.1 Introduction

This Part looks at the collective financial position of the eight universities as at 31 December 2014, and details the main drivers behind the net result at this date. It also analyses the universities against five financial sustainability risk indicators.

To enable comparisons between universities, we have made the audit adjustments outlined in Figure 1B of this report to the financial information of Deakin University and the University of Melbourne. This effectively adjusts the accounting treatment for government grants so that it is the same at all universities and meaningful comparisons can therefore be made.

When assessing financial sustainability, our indicator results have been calculated using the consolidated entity information of each university so that the total sum of all university activities is taken into account.

2.2 Conclusion

The university sector is in a healthy financial position, posting surpluses year on year and continuing to hold large asset portfolios. While overall the university sector has been assessed as having a low financial sustainability risk, there are emerging concerns in longer-term financial sustainability risks that need to be monitored.

2.3 Financial results

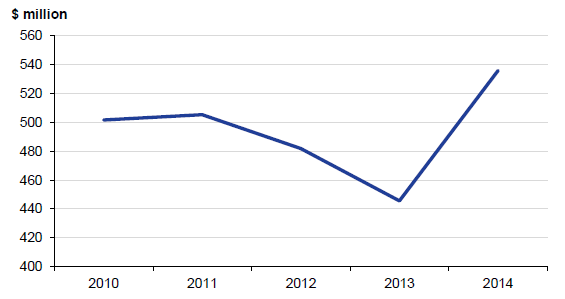

Taking into account adjustments arising from the qualifications outlined in Part 1, the university sector has continued to have significant operating surpluses, reporting a collective net surplus of $537.1 million for the 2014 financial year. This is a significant increase of 20.3 per cent on the prior year ($446.5 million surplus at 31 December 2013), and is the highest result for the past five years, as shown in Figure 2A.

This strong result for 2014 was largely due to Monash University and the University of Melbourne recording additional investment revenue of $232.8 million because they restructured their investment portfolios.

In accordance with Australian Accounting Standards, all previous gains made on available-for-sale investments were recorded by Monash and Melbourne universities in an equity reserve. Upon restructuring of the investment portfolios, these gains were realised and were recognised as revenue.

There was no cash flow effect from this change, meaning the universities did not receive $232.8 million in cash as a result of the restructure. However, the recognition of these gains added significant revenue and net surpluses at these two universities. Without the gains from these investment portfolio restructures, the net surplus for the sector would have been $304.3 million which would have been a decrease of 31.8 per cent on the prior year.

Figure 2A

Net result of university sector financial years ending 31 December 2010 to 2014

Note: Net results for each financial year include adjustments arising from qualifications issued on the recognition of grant revenue, as outlined in Part 1.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

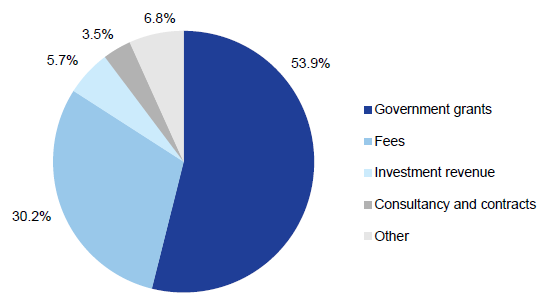

2.3.1 Revenue

The sources of revenue for universities have not changed for the past five years. Universities continue to be primarily funded by both Commonwealth and state grants, and student fees, as shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2B

Composition of university revenue, 2014 financial year

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Government grants, from both the Commonwealth and state governments are the main source of income for universities, with the eight entities collectively receiving $2 991.0 million in government grants in the 2014 financial year ($2 917.2 million in 2013).

Six per cent ($455.9 million) of university revenue came from investments during the 2014 financial year—almost double the $228.5 million of investment revenue received in the prior year. The increase was almost wholly accounted for by the investment restructuring gain recorded at Monash University and the University of Melbourne, as discussed in Section 2.3.

Potential funding changes

In August 2014, the Commonwealth Government introduced a Bill into Parliament to change the funding regime for universities and other higher education entities across Australia, with a potential implementation date of 1 January 2016.

The bill proposed to deregulate the provision of student places at universities. This means that Commonwealth funded places will be opened up to non-university providers and all institutions will be allowed to set the price for student fees. The Commonwealth also plans to reduce the funding it provides for student places, with any loss in revenue expected to be compensated by higher student fees.

At the time of publishing, these proposed changes were still being debated in the Commonwealth Parliament.

The impact of any changes will need to be assessed quickly by universities, who received $2 731.4 million of Commonwealth grant funding, excluding capital grants, in 2014 ($2 567.0 million in 2013), and their business models will need to be adapted so that they remain financially sustainable under any new funding model. This will be a challenge given the significance of government funding to the revenue of universities.

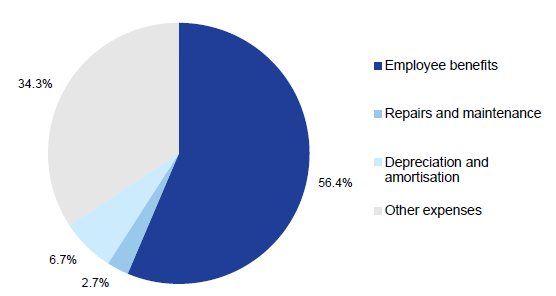

2.3.2 Expenditure

The largest expense of a university is employee benefits as they are large employers of academic and non-academic staff. Figure 2C shows the main types of expenditure incurred across the eight universities during the 2014 financial year.

Figure 2C

Composition of university expenditure, 2014 financial year

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In the 2014 financial year, employee benefits cost $4 242.2 million across the eight universities, which was an 8 per cent increase on 2013 ($3 911.7 million in 2013). Of this $2 246.2 million was for academic staff and $1 995.9 million for non‑academic staff.

The growth was largest in non-academic salaries, which increased by 9.0 per cent from 2013 to 2014. Contributing to the increase in non-academic salaries were redundancy payments made at a number of universities who sought to decrease staff numbers, particularly in support functions. While not all redundancy costs can be identified in university financial statements, significant redundancy programs across both academic and non-academic staff occurred at:

- University of Melbourne—at least $54.7 million

- La Trobe University—at least $37.1 million

- Victoria University—at least $16.9 million.

2.4 Financial sustainability risks

To be sustainable, universities should generate sufficient revenue from operations to meet financial obligations, and to fund asset replacement and new asset acquisitions.

To assess the financial sustainability risks in the university sector we have analysed five core indicators over a five-year period. An overall risk rating is determined for each university taking into account short- and long-term risks. Appendix C describes the financial sustainability indicators, risk assessment criteria and the benchmarks we use in this report, as well as the indicator results for each university for the past five years.

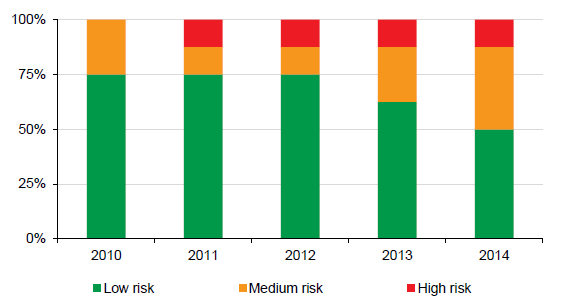

Overall, we assessed the university sector as having a mostly low financial sustainability risk. Across the sector, continual strong surpluses combined with largely good liquidity indicate that the sector has no financial sustainability risks in the short term.

Monash University is the only entity that has received a high financial sustainability risk rating in 2014, as it has for the previous three financial years. This assessment is driven by a low liquidity ratio. Monash's cash management and investment strategies mean they place cash in long-term financial instruments for better returns. This affects their liquidity ratio. The long term instruments could be called upon for liquidity purposes if required. Further analysis of how Monash approaches cash management will be undertaken through our 2015 financial audit of this entity.

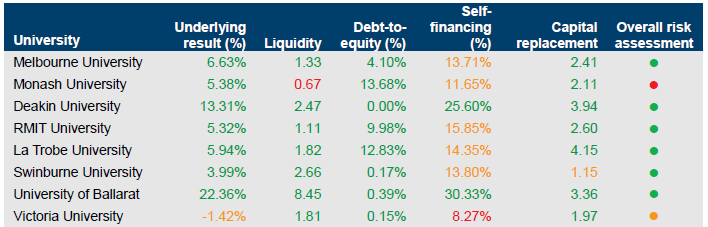

Figure 2D

Universities' financial sustainability risk analysis at 31 December 2010 to 2014

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

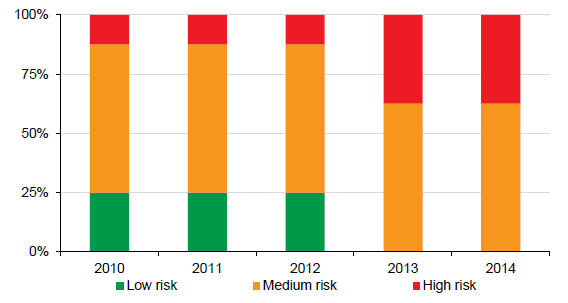

Long-term financial sustainability concerns are emerging for the sector. Three universities have been rated overall as having a medium financial sustainability risks in 2014 principally due to their self-financing indicator. However, all universities had medium- or high-risk assessments from this indicator. This indicates that universities are not able to replace assets from cash generated through their own funds. The self‑funded indicator assessments are shown in Figure 2E.

Figure 2E

Universities' self-financing indicators at 31 December 2010 to 2014

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

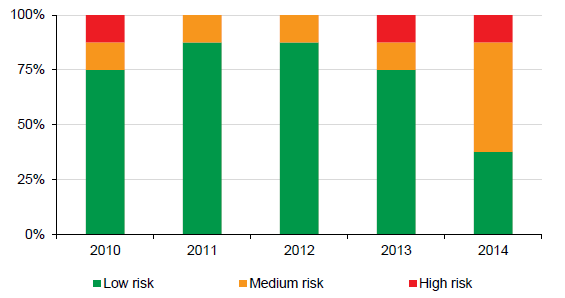

Coupled with this, the capital replacement indicator results for all eight universities have fallen significantly over the past five years; with universities spending less on their assets. Figure 2F summarises the capital replacement indicator results over the past five years.

The capital replacement indicator assesses the rate of spending on the renewal and replacement of fixed assets, compared to the consumption of assets as measured by depreciation. Expenditure on replacing or renewing assets should exceed depreciation so that the university can continue to provide services in fit for purpose assets.

Figure 2F

Universities' capital replacement indicators at 31 December 2010 to 2014

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Over time, the cumulative effect of underspending on asset renewal and new assets could result in some assets not being fit for purpose, or in increased maintenance costs. This trend of reduced self-financing and spending on assets needs to be monitored.

Recommendation

- That universities review asset replacement and renewal plans to assure themselves that spending on physical assets is sufficient to maintain service delivery.

3 Travel and accommodation expenditure

At a glance

Background

Universities in Victoria collectively spent $137.0 million on travel and accommodation in 2014. Travel by university staff, paid for with public funds must be appropriately controlled to mitigate the risk of waste or lack of financial prudence.

Conclusion

Universities have policies and procedures for travel and accommodation but they are not comprehensive and compliance with these policies and procedures is poor. Consequently, universities cannot always demonstrate public money is spent prudently on travel and for the benefit of the university.

Findings

- While universities have travel and accommodation policies and procedures in place, not all policies covered areas of public interest, such as who can utilise frequent flyer points or what benefits are derived from travel undertaken.

- The absence of supporting documentation, including an acquittal of the benefits to be obtained from travel, means the universities cannot show that the use of public funds for travel was to the betterment of the university.

- There are poor levels of compliance with the travel and accommodation policies and procedures.

Recommendations

That universities:

- review travel policies and procedures and ensure they are comprehensive

- strengthen the procedures covering the monitoring and oversight of supporting documentation and acquittal of travel benefits

- implement regular reviews of compliance with travel and accommodation policies and procedures.

3.1 Introduction

Universities in Victoria collectively spent $137.0 million on travel in 2014. This significant amount of spending reflects the high volume of international ($72.5 million) and interstate ($35.4 million) travel that is undertaken to support the work of universities. In particular, travel is undertaken for research, conferences and presentations, to study and to teach.

Travel of any kind performed by university employees, and paid for with public funds, must have a clear benefit that has been documented and demonstrated before approval is given. It is therefore important that all forms of travel and accommodation expenditure are appropriately approved and monitored to mitigate the risk of waste or lack of financial prudence.

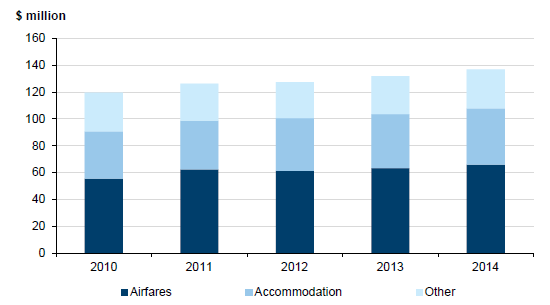

The amount spent by universities on travel and accommodation has increased over the past five financial years. Figure 3A provides the trends for all universities categorised into travel, accommodation, and other travel-related expenses such as hire cars, taxis and conference fees for the years 2010 to 2014.

Figure 3A

Trend for travel and accommodation expenditure for universities

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

3.2 Conclusion

All universities have sound frameworks in place for travel and accommodation including policies and procedures. However, these policies are silent in critical areas where the classification between personal and business expense is not clear. Also there is poor compliance with established travel and accommodation policies and procedures. Consequently, universities are unable to demonstrate that public money spent on travel and accommodation is always prudent, and that it always results in benefits for the university.

3.3 Internal control frameworks

Universities are required to implement and maintain an effective internal control framework for managing, approving and monitoring travel and accommodation expenditure.

The internal control framework should ensure that travel and accommodation expenditure is legitimately incurred for business needs, is appropriately authorised, and is in line with stated policies and procedures.

We assessed the internal control framework for travel and accommodation of all eight universities against the better practice elements outlined in Appendix D.

We found that policies and procedures exist at all universities to cover travel and accommodation expenditure. However, not all policies comprehensively address areas of public interest, including:

- a clear definition of personal travel, and a set of rules on cost sharing where personal travel is attached to business travel

- specific employees responsible for approving travel requests

- rules around the ownership and use of frequent flyer points

- guidelines for travel by companions, such as family members, including the allocation of costs

- restrictions on annual leave before and/or after business travel

- rules regarding the use of mini bars and associated reimbursements.

As a consequence of these policy gaps, the rules on travel and accommodation may be open to individual interpretation and not be applied consistently. There is also an increased risk that personal travel expenditure is paid for with public money.

Frequent flyer programs

Universities are not generally paying for staff membership of frequent flyer programs unless an employment contract specifies the entitlement. Therefore, if a staff member has a frequent flier membership it is often linked to them and not the university. As the sector spent $66.0 million on airfares in the 2014 financial year, the associated reward points accumulated would be significant.

Five of the eight universities' policies do not address how frequent flyer points generated by travel for the university can be used. As a result, a university staff member is not prohibited from using any reward points obtained from university travel for personal travel. This means that university employees are receiving a personal advantage from the use of public funds which may not be in the public interest. There is also a missed opportunity for universities to save public money by using frequent flyer points for future university travel.

Of the three universities that address frequent flyer points in their travel policies:

- Swinburne University's policy expressly allows staff to redeem frequent flyer points at the staff member's discretion

- Deakin University is the only university that encourages the use of frequent flyer points on future university travel

- La Trobe University provides staff with the option to use the points for personal travel or upgrades while undertaking business travel.

The Public Sector Commissioner recommends that frequent flier points earned through publicly-funded travel be used to fund further business travel by the public sector entity. Frequent flyer points should not be retained and used by public sector employees for personal benefit.

3.4 Benefits of travel

The amount of travel taken, and the money spent from the public purse, needs to be balanced against the benefits travel provides. Universities should require a clear demonstration that both value for money and benefits to the university are to be achieved from any expenditure on travel and accommodation. This will mitigate the risk of waste or lack of financial prudence.

However, six of the eight universities do not require staff to document the expected benefits to be gained from travel. As a result, there can be no subsequent checks to show that the expected benefits were actually obtained. At the two universities that did require staff to document the expected benefits to be gained from the travel prior to booking, our testing only identified two instances where there was a subsequent acquittal to demonstrate that the expected benefits had actually been gained.

The absence of this benefits documentation and acquittal means the universities are not in a position to show that the use of public funds for travel was to the betterment of the university. This is a significant flaw for a public sector entity, where public money is used to fund travel and accommodation.

3.5 Compliance with policies and procedures

We reviewed a sample of 10 travel and accommodation transactions entered into during 2014 at each of the eight universities. The sample was checked for compliance with the policies and procedures in place at each university.

All 80 transactions had supporting invoices to verify the amounts spent, and the spending had not exceeded the predetermined limit set at each university.

However, there were significant shortcomings observed that indicate poor levels of compliance with the travel and accommodation policies and procedures in place at each university. We noted that:

- Travel diaries are not being completed. For 16 (20.0 per cent) of the transactions sampled where the length of the trip required the preparation of a travel diary, the diary was either incomplete or unable to be located. There are tax requirements for travel diaries to be kept to demonstrate what travel has been undertaken for business purposes, and what has been personal travel. Universities are at risk of tax penalties where travel diaries are required but have not been kept.

- There was little evidence to show that value for money and benefit to the university had been gained for the transactions tested.

- Approved travel requests could not be sighted for three (3.75 per cent) of the transactions tested. We therefore had no assurance that the travel had been appropriately approved before being booked. Further, in one instance the details of the travel approved in the travel request did not match the actual travel taken.

- Travel requests are not always approved by an appropriate, authorised delegate. This was found to be the case in four (5.0 per cent) of the transactions sampled, with only La Trobe University and RMIT University having all their sampled transactions appropriately approved.

There is inadequate compliance with the travel and accommodation policies and procedures. The level of noncompliance means universities are not well placed to demonstrate they have adequate controls and monitoring over such expenditure.

Only four of the eight universities had performed an internal audit review over travel and accommodation expenditure within the past four years. Internal audit reports identified similar deficiencies regarding travel diaries and noncompliance with policies and procedures as our testing showed. It is disappointing that noncompliance continues to be an issue and that the recommendations of internal audit have not been actioned.

Recommendations

That universities:

- review travel policies and procedures and ensure they are comprehensive and address areas of public interest including ownership and use of frequent flyer points

- strengthen the procedures covering monitoring and oversight of supporting documentation and acquittal of travel benefits

- implement regular reviews of compliance with travel and accommodation policies and procedures and take action where noncompliance is identified.

Appendix A. Audit status

Figure A1

Audit status of university sector for year ending 31 December 2014

Entity |

Financial statements |

||

|---|---|---|---|

Clear opinion |

Opinion date |

Statutory deadline met |

|

Deakin University Reason for qualification: Deakin University has deferred the recognition of $27.9 million ($33.2 million in 2013) of Australian Government Financial Assistance grant income received in 2014 and recognised it as Trade and Other Payables in its statement of financial position as at 31 December 2014. |

✘ |

20-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Callista Software Services Pty Ltd |

✔ |

06-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Deakin Digital Pty Ltd |

✔ |

02-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Deakin Residential Services Pty Ltd |

✔ |

02-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Unilink Limited |

✔ |

02-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Federation University |

✔ |

24-Feb-15 |

✔ |

Datascreen Pty Ltd |

✔ |

24-Feb-15 |

✔ |

Inskill Pty Ltd |

✔ |

24-Mar-15 |

✔ |

The School of Mines and Industries Ballarat Limited |

✔ |

24-Mar-15 |

✔ |

UB Housing Pty Ltd |

✔ |

02-Apr-15 |

✘ |

La Trobe University |

✔ |

18-Mar-15 |

✔ |

La Trobe International Pty Ltd |

✔ |

18-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Medical Centre Development Pty Ltd |

✔ |

6-May-15 |

✘ |

La Trobe Accommodation Services Pty Ltd |

✔ |

18-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Monash University |

✔ |

24-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Monash Accommodation Services Pty Ltd |

✔ |

24-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Monash College Pty Ltd |

✔ |

13-Feb-15 |

✔ |

Monash Commercial Pty Ltd |

✔ |

24-Feb-15 |

✔ |

Monash Educational Enterprises |

✔ |

24-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Monash Investment Holdings Pty Ltd |

✔ |

24-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Monash Investment Trust |

✔ |

24-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Monash Property South Africa Pty Ltd |

✔ |

24-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Monash University Foundation |

✔ |

24-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Monash University Foundation Pty Ltd |

✔ |

24-Mar-15 |

✔ |

RMIT University |

✔ |

16-Mar-15 |

✔ |

The RMIT Foundation |

✔ |

13-Feb-15 |

✔ |

RMIT University Vietnam LLC |

✔ |

02-Mar-15 |

✔ |

RMIT Training Pty Ltd |

✔ |

13-Feb-15 |

✔ |

RMIT Vietnam Holdings Pty Ltd |

✔ |

02-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Spatial Vision Innovations Pty Ltd |

✔ |

26-Feb-15 |

✔ |

RMIT Spain S.L. |

✔ |

23-Feb-15 |

✔ |

Swinburne University of Technology |

✔ |

24-Mar-15 |

✔ |

National Institute of Circus Arts Limited |

✔ |

06-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Swinburne College Pty Ltd |

✔ |

06-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Swinburne Intellectual Property Trust |

✔ |

06-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Swinburne Ltd |

✔ |

06-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Swinburne Student Amenities Association Limited |

✔ |

23-Feb-15 |

✔ |

Swinburne Ventures Limited |

✔ |

06-Mar-15 |

✔ |

The University of Melbourne Reason for qualification: The University of Melbourne has deferred the recognition of $217 million ($226 million in 2013) of Australian Government Financial Assistance grant income received in 2014 and recognised it as Other Liabilities in its statement of financial position as at 31 December 2014. |

✘ |

25-Mar-15 |

✘ |

Australian Music Examinations Board (Vic) Ltd |

✔ |

20-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Australian National Academy of Music Foundation Ltd |

✔ |

22-Apr-15 |

✘ |

Australian National Academy of Music Ltd Reason for qualification: The Australian National Academy of Music Ltd has deferred the recognition of $0.8 million ($0.8 million in 2013) of Australian Government Financial Assistance grant income in 2014 and recognised it as Other Current Liabilities in its statement of financial position as at 31 December 2014. |

✘ |

11-May-15 |

✘ |

Melbourne Business School Foundation Trust |

✔ |

20-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Melbourne Business School Foundation Ltd |

✔ |

20-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Melbourne Business School Limited |

✔ |

24-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Melbourne Dental Clinic Ltd |

✔ |

14-Apr-15 |

✘ |

Melbourne University Publishing Ltd |

✔ |

14-Apr-15 |

✘ |

Mount Eliza Graduate School of Business and Government Limited |

✔ |

20-Mar-15 |

✔ |

MU Student Union Ltd |

✔ |

22-Apr-15 |

✔ |

Nossal Institute Limited |

✔ |

20-Mar-15 |

✔ |

UM Commercialisation Pty Ltd |

✔ |

20-Mar-15 |

✔ |

UM Commercialisation Trust |

✔ |

20-Mar-15 |

✔ |

UoM Commercial Ltd |

✔ |

23-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Victoria University |

✔ |

20-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Victoria University Enterprises Pty Ltd |

✔ |

20-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Victoria University Foundation |

✔ |

20-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Victoria University Foundation Ltd |

✔ |

20-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Victoria University International Pty Ltd |

✔ |

20-Mar-15 |

✔ |

Victoria University of Technology (Singapore) Pte Ltd |

✔ |

20-Mar-15 |

✔ |

2014 Total |

57 |

52 |

|

2013 Total |

61 |

47 |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Appendix B. Management letter risk ratings

Figure B1 shows the risk ratings applied to management letter points raised during an audit review.

Figure B1

Risk definitions applied to issues reported in audit management letters

Rating |

Definition |

Management action required |

|---|---|---|

Extreme |

The issue represents:

|

Requires immediate management intervention with a detailed action plan to be implemented within one month. Requires executive management to correct the material misstatement in the financial report as a matter of urgency to avoid a qualified audit opinion. |

High |

The issue represents:

|

Requires prompt management intervention with a detailed action plan implemented within two months. Requires executive management to correct the material misstatement in the financial report to avoid a qualified audit opinion. |

Medium |

The issue represents:

|

Requires management intervention with a detailed action plan implemented within three to six months. |

Low |

The issue represents:

|

Requires management intervention with a detailed action plan implemented within six to 12 months. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Appendix C. Financial sustainability

Financial sustainability indicators

Figure C1 shows the indicators used in assessing the financial sustainability of the universities in Part 2 of this report. These indicators should be considered collectively, and are more useful when assessed over time as part of a trend analysis.

Figure C1

Financial sustainability risk indicators

|

Indicator |

Formula |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

Underlying result (%) |

Adjusted net surplus / Total underlying revenue |

A positive result indicates a surplus, and the larger the percentage, the stronger the result. A negative result indicates a deficit. Operating deficits cannot be sustained in the long term. Underlying revenue does not take into account one-off or non-recurring transactions. Net result and total underlying revenue is obtained from the comprehensive operating statement and is adjusted to take into account large one-off (non-recurring) transactions. |

|

Liquidity (ratio) |

Current assets / Current liabilities |

This measures the ability to pay existing liabilities in the next 12 months. A ratio of one or more means there are more cash and liquid assets than short-term liabilities. Current liabilities exclude long-term employee provisions and revenue in advance. |

|

Debt-to-equity (%) |

Debt / Equity |

This is a longer-term measure that compares all current and non-current interest bearing liabilities to equity. A low ratio indicates less reliance on debt to finance the capital structure of an organisation. It complements the liquidity ratio which is a short-term measure. |

|

Self-financing (%) |

Net operating cash flows / Underlying revenue |

Measures the ability to replace assets using cash generated by the entity's operations. The higher the percentage the more effectively this can be done. Net operating cash flows are obtained from the cash flow statement. |

|

Capital replacement (ratio) |

Cash outflows for property, plant and equipment / Depreciation |

Comparison of the rate of spending on infrastructure with its depreciation. Ratios higher than 1:1 indicate that spending is faster than the depreciating rate. This is a long-term indicator, as capital expenditure can be deferred in the short term if there are insufficient funds available from operations, and borrowing is not an option. Cash outflows for property, plant and equipment are taken from the cash flow statement. Depreciation is taken from the comprehensive operating statement. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The analysis of financial sustainability in this report reflects on the position of each consolidated university.

Financial sustainability risk assessment criteria

The financial sustainability of each university has been assessed using the risk criteria outlined in Figure C2.

Figure C2

Financial sustainability indicators – risk assessment criteria

|

Risk |

Underlying result |

Liquidity |

Debt-to-equity |

Self-financing |

Capital replacement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

High |

Negative 10% or less |

Less than 0.7 |

More than 60% |

Less than 10% |

Less than 1.0 |

|

Insufficient revenue is being generated to fund operations and asset renewal. |

Immediate sustainability issues with insufficient current assets to cover liabilities. |

Potential long‑term concern over ability to repay debt levels from own source revenue. |

Insufficient cash from operations to fund new assets and asset renewal. |

Spending on capital works has not kept pace with consumption of assets. |

|

|

Medium |

Negative 10%–0% |

0.7–1.0 |

40–60% |

10–20% |

1.0–1.5 |

|

A risk of long‑term run down to cash reserves and inability to fund asset renewals. |

Need for caution with cash flow, as issues could arise with meeting obligations as they fall due. |

Some concern over the ability to repay the debt from own source revenue. |

May not be generating sufficient cash from operations to fund new assets. |

May indicate spending on asset renewal is insufficient. |

|

|

Low |

More than 0% |

More than 1.0 |

Less than 40% |

More than 20% |

More than 1.5 |

|

Generating surpluses consistently. |

No immediate issues with repaying short‑term liabilities as they fall due. |

No concern over the ability to repay debt from own source revenue. |

Generating enough cash from operations to fund new assets. |

Low risk of insufficient spending on asset renewal. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

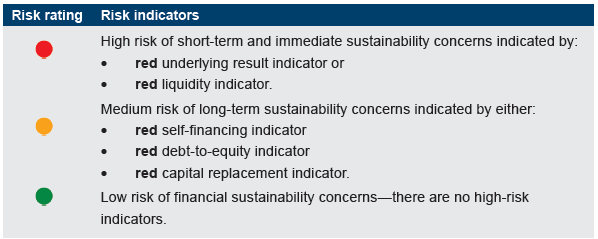

The overall financial sustainability risk assessment has been calculated using the ratings determined for each indicator as outlined in Figure C3.

Figure C3

Overall financial sustainability risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Financial sustainability analysis

The financial sustainability for the eight universities, for each financial year ending 31 December between 2010 and 2014 are shown in Figures C4 to C8.

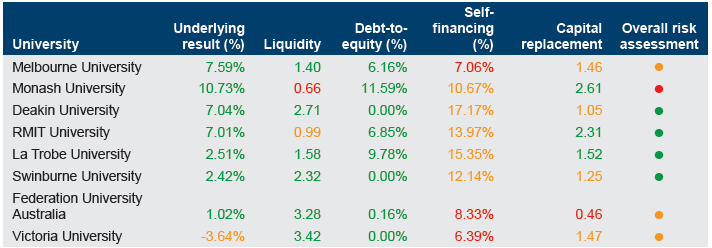

Figure C4

Actual financial sustainability risk ratios for universities at 31 December 2014

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

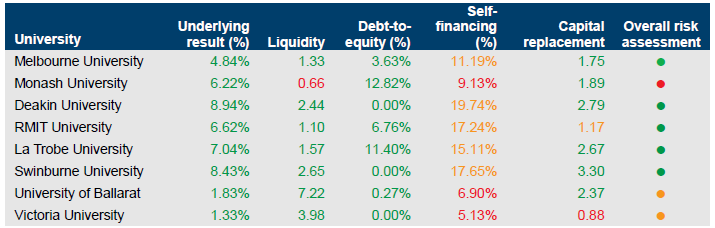

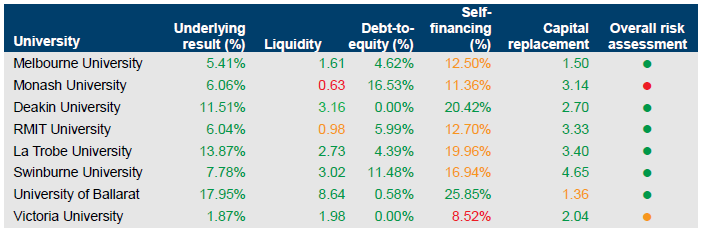

Figure C5

Actual financial sustainability risk ratios for universities at 31 December 2013

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

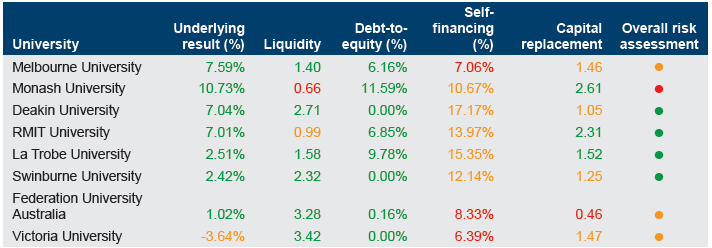

Figure C6

Actual financial sustainability risk ratios for universities at 31 December 2012

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure C7

Actual financial sustainability risk ratios for universities at 31 December 2011

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure C8

Actual financial sustainability risk ratios for universities at 31 December 2010

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Appendix D. Travel and accommodation expenses

Figure D1 outlines the key elements of an effective internal control framework for travel and accommodation expenditure.

The framework draws upon the:

- Standing Directors of the Minister for Finance under the Financial Management Act 1994.

- Good practice guide Controlling Sensitive Expenditure: Guidelines for Public Entities published by the Office of the Auditor-General in New Zealand.

Figure D1

Key elements of an effective internal control framework for

travel and accommodation

Component |

Key elements |

|---|---|

Policy |

|

Management practices |

|

Governance and oversight |

|

Source: Victorian Auditors-General's Office.

Appendix E. Glossary

Accountability

Responsibility on public sector entities to achieve their objectives, with regard to reliability of financial reporting, effectiveness and efficiency of operations, compliance with applicable laws, and reporting to interested parties.

Asset

A resource controlled by an entity as a result of past events, and from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the entity.

Audit Act 1994

The Audit Act 1994 establishes the operating powers and responsibilities of the Auditor-General. This includes the operations of his office—the Victorian Auditor‑General's Office (VAGO)—as well as the nature and scope of audits conducted by VAGO.

Auditor's opinion

Written expression within a specified framework indicating the auditor's overall conclusion on the financial (and performance) reports based on audit evidence obtained.

Capital expenditure

Amount capitalised to the balance sheet for contributions by a public sector entity to major assets owned by the entity, including expenditure on:

- capital renewal of existing assets that returns the service potential or the life of these assets

- expenditure on new assets, including buildings, infrastructure, plant and equipment.

Clear audit opinion

A positive written expression provided when the financial report has been prepared and presents fairly the transactions and balances for the reporting period in accordance with the requirements of the relevant legislation and Australian Accounting Standards—also referred to as an unqualified audit opinion.

Corporations Act 2001

The Corporations Act 2001 is an act of the Commonwealth of Australia that sets out the laws dealing with business entities in Australia at federal and state levels. It focuses primarily on companies, although it also covers some laws relating to other entities such as partnerships and managed investment schemes.

Depreciation

The systematic allocation of the value of an asset over its expected useful life.

Emphasis of matter

An auditor's report can include an emphasis of matter paragraph that draws attention to a disclosure or item in the financial report that is relevant to the users of the auditor's report but is not of such nature that it affects the auditor's opinion—i.e. the auditor's opinion remains unqualified.

Entity

A body, whether corporate or unincorporated, that has a public function to exercise on behalf of the state or is wholly owned by the state—including departments, statutory authorities, statutory corporations and government business enterprises.

Expense

Outflows or other depletions of economic benefits in the form of incurrence of liabilities or depletion of assets of the entity.

Financial reporting direction

Financial reports are prepared in accordance with Australian Accounting Standards and Interpretations as issued by the Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB). When an AASB standard provides accounting treatment options, the Minister for Finance issues financial reporting directions to ensure consistent application of accounting treatment across the Victorian public sector in compliance with that particular standard.

Financial sustainability

An entity's ability to manage financial resources so it can meet spending commitments, both at present and into the future.

Financial year

A period of 12 months for which a financial report is prepared.

Going concern

An entity that is expected to be able to pay its debts as and when they fall due, and continue in operation without any intention or necessity to liquidate or otherwise wind up its operations.

Governance

The control arrangements in place that are used to govern and monitor an entity's activities in order to achieve its strategic and operational goals.

Impairment

The amount by which the value of an asset held by an entity exceeds its recoverable amount.

Internal audit

A function of an entity's governance framework that examines and reports to management on the effectiveness of risk management, control and governance processes.

Internal control

Internal control is a means by which an entity's resources are directed, monitored and measured. It plays an important role in preventing and detecting error and fraud and protecting the entity's resources.

Liability

A present obligation of an entity arising from past events, the settlement of which is expected to result in an outflow from the entity of resources embodying economic benefits.

Management letter

A letter issued by the auditor to the governing body, the audit committee and management of an entity outlining weaknesses in controls and other issues identified during the financial audit.

Materiality

Information is material if its omission or misstatement could influence the economic decisions of users taken on the basis of the financial report. Materiality depends on the size or nature of the item or error judged in the particular circumstances of its omission or misstatement.

Net result

The net result is calculated by subtracting an entity's total expenses from the total revenue, to show what the entity has earned or lost in a given period of time.

Non-reciprocal

Transfers in which an entity receives assets without directly giving equal value in exchange to the other party to the transfer.

Qualified audit opinion

A qualification is issued when the auditor concludes that an unqualified opinion cannot be expressed due to one of the following reasons:

- disagreement with those charged with governance

- conflict between applicable financial reporting frameworks

- limitation of scope.

A qualified opinion shall be expressed as being unqualified except for the effects of the matter to which the qualification relates.

Performance report

A statement containing predetermined performance indicators, targets and actual results achieved for the financial year, with an explanation for any significant variance between the results and targets.

Relevant

Measures or indicators used by an entity are relevant if they have a logical and consistent relationship to its objectives and are linked to the outcomes to be achieved.

Revaluation

Recognising a reassessment of values for non-current assets at a particular point in time.

Revenue

Inflows of funds or other enhancements or savings in outflows of service potential, or future economic benefits in the form of increases in assets or reductions in liabilities of an entity, other than those relating to contributions by owners which result in an increase in equity during the reporting period.

Risk

The chance of a negative impact on the objectives, outputs or outcomes of the entity.

Risk register

A tool to assist an entity in identifying, monitoring and mitigating risks.

Appendix F. Audit Act 1994 section 16—submissions and comments

Introduction

In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, a copy of this report, or relevant extracts from the report, was provided to the Department of Education & Training, the Department of Treasury and Finance and each of the eight universities with a request for submissions or comments.

The submissions and comments provided are not subject to audit nor the evidentiary standards required to reach an audit conclusion. Responsibility for the accuracy, fairness and balance of those comments rests solely with the agency head.

RESPONSE provided by the Acting Secretary, Department of Education & Training