Domestic Building Oversight Part 2: Dispute Resolution

Audit snapshot

What we examined

Whether Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Victoria (DBDRV) resolves disputes between domestic building consumers and practitioners.

Agencies examined: Consumer Affairs Victoria, the Department of Transport and Planning, and the Victorian Building Authority.

Why this is important

Building a home is a significant financial decision for Victorians.

In 2022, the domestic building industry was worth $28.7 billion to the Victorian economy, with 92,158 building permits issued.

A 2016 survey found one in 4 residential builds in Victoria involve a dispute between the homeowner and the builder.

In 2017, the government established DBDRV to resolve domestic building disputes through conciliation.

Ensuring that the domestic building dispute resolution system is fair and efficient has significant consequences for both builders and homeowners.

What we concluded

DBDRV resolves domestic building disputes fairly and at no cost to consumers.

However, in 2022–23 DBDRV took longer than its benchmark to allocate cases to its dispute resolution officers (officers). It also does not allocate high priority cases faster than others.

DBDRV has made domestic building dispute resolution more cost-effective for both the government and consumers.

From April 2017 to October 2023, it resolved 7,484 disputes that would have cost more for both groups had they been dealt with by the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT).

What we recommended

We made 5 recommendations to DBDRV about:

- allocating cases

- giving applicants key information

- further ensuring its services are fair

- integrating targets in its reporting.

Video presentation

Key facts

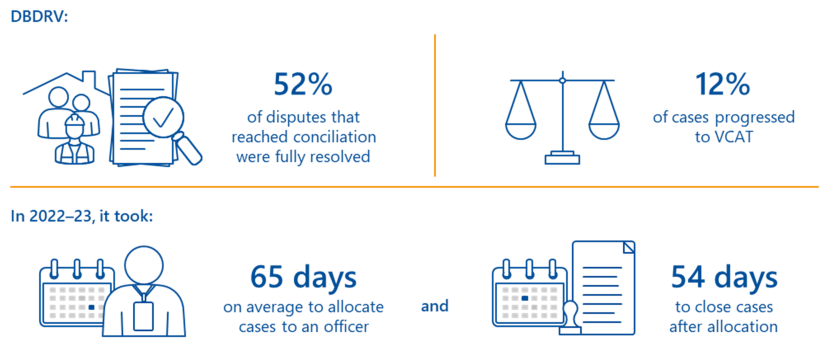

Source: VAGO.

Our recommendations

We made 5 recommendations to address 4 issues. Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Victoria has accepted all in full.

| Key issues and corresponding recommendations | Agency response | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Issue: Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Victoria is not meeting its benchmark for allocating cases to dispute resolution officers | ||||

| Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Victoria | 1 | Enhance the process for triaging applications to reduce the time it takes to allocate cases to a dispute resolution officer, especially cases assessed as high priority (see Section 2). | Accepted | |

| Issue: Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Victoria is not meeting its benchmark for allocating cases to dispute resolution officers | ||||

| Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Victoria | 2 | Improve information available to new applicants on current wait times and case priority levels (see Section 2). | Accepted | |

| Issue: Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Victoria could take further steps to ensure the fairness of its service | ||||

| Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Victoria | 3 | Improve guidance for dispute resolution officers on when to recommend a building assessment for a case, to ensure consistent use of this tool (see Section 2). | Accepted | |

| 4 | To better understand consumer perceptions of fairness, consider sending customer feedback surveys before a consumer's case is closed (see Section 2). | Accepted | ||

| Issue: Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Victoria's reporting did not include benchmarks or targets | ||||

| Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Victoria | 5 | Align organisational benchmarks with internal reporting, to ensure all staff understand whether Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Victoria is meeting its intended outcomes (see Section 3). | Accepted | |

What we found

This section summarises our key findings. Sections 2 and 3 detail our complete findings, including supporting evidence.

When reaching our conclusions, we consulted with Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Victoria (DBDRV), other audited agencies and the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) and considered their views. The agencies’ full responses are in Appendix A.

Why we did this audit

In April 2017, the government established DBDRV to resolve domestic building disputes through conciliation as efficiently and cheaply as possible.

Parties with a domestic building dispute must first apply for conciliation at DBDRV before they can take a case to VCAT. The VCAT process may involve a hearing before a VCAT member, involving evidence, witnesses and questioning.

In this audit, we investigated whether DBDRV is achieving its intended outcomes and resolving domestic disputes.

Our key findings

Our findings fall into 3 key areas:

| 1 | DBDRV's service is free and fair, but it is not meeting its timeliness benchmarks. |

| 2 | DBDRV's service meets accessibility requirements, except for not providing some key information to applicants. |

| 3 | Resolving domestic building disputes through DBDRV is more cost-effective for the state and consumers than through VCAT. |

Key finding 1: DBDRV's service is free and fair, but it is not meeting its timeliness benchmarks

DBDRV's service is free and fair

DBDRV does not charge consumers for its services.

Furthermore, its guidelines, practices and review procedures align with best practice for fair dispute resolution.

DBDRV does not meet all its timeliness benchmarks

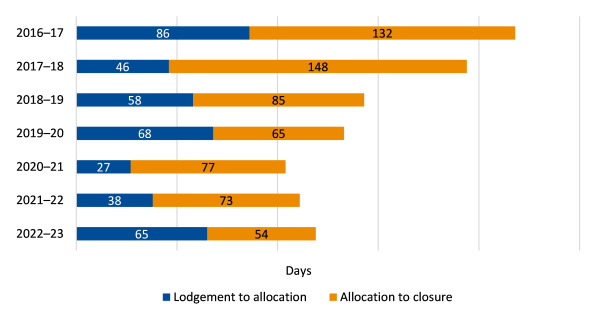

In 2022–23, DBDRV took 65 days on average to allocate an application to a dispute resolution officer (officer), not meeting its benchmark of 44 days.

This includes cases that DBDRV lists as a high priority. On average, these took 71 days to allocate, similar to normal priority cases.

After allocation, DBDRV took an average of 54 days to close all cases over the same period. This beats its benchmark of 65 days.

However, cases that reached conciliation took 91 days to close after allocation.

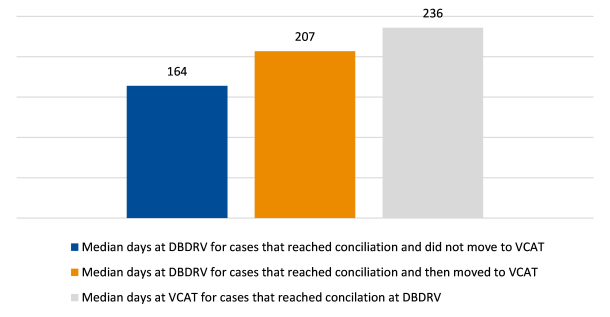

DBDRV's process for applicants is faster than VCAT's. This is expected, as VCAT's procedures are more formal than DBDRV's.

| Up to November 2022, cases that reached conciliation at DBDRV and … | Took a median of ... |

|---|---|

| moved to VCAT | 207 days at DBDRV and 236 days at VCAT. |

| did not move to VCAT | 164 days at DBDRV. |

When DBDRV officers close a case, they give it a complexity rating based on factors including:

- the number of items in dispute

- the length of the dispute

- the tone of contact between the parties.

On average, based on this final rating, cases that later go on to VCAT are 11 per cent more complex than those that do not reach VCAT.

This complexity may partially explain why these cases take longer.

Key finding 2: DBDRV’s service meets accessibility requirements, except for not providing some key information to applicants

New applicants do not know how long they will wait or how their case has been assessed

DBDRV gives the public clear guidance on how to use its service. Its online application form is straightforward to use.

However, DBDRV does not give applicants an indicative timeline for when an officer will contact them after they have lodged their application.

DBDRV does not have a direct phone number for consumers. Instead, DBDRV’s listed phone number connects to the Building Information Line (information line) run by Consumer Affairs Victoria. This information line offers consumers advice on where to go if they have a dispute, and which jurisdiction the matter is likely to fall under.

Once DBDRV allocates an officer to an application, it puts them in direct contact.

However, consumers whose applications have not yet been allocated cannot access information about their case’s status online or over the phone. This information includes:

- when an officer is likely to contact them

- the priority level assigned to their case.

Key finding 3: Resolving domestic building disputes through DBDRV is more cost-effective for the state and consumers than through VCAT

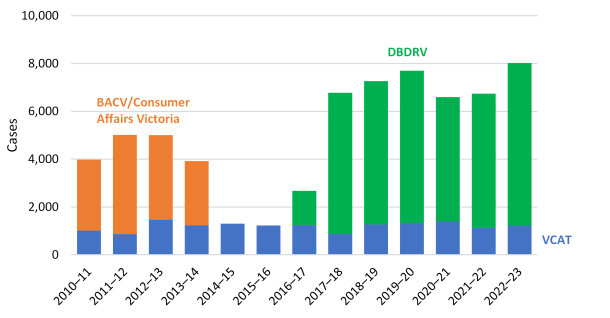

Demand for building dispute resolution has risen

Demand for building dispute resolution services has risen since the government established DBDRV.

Previously, the Building Advice and Conciliation Victoria (BACV) offered voluntary dispute resolution. On average it closed 2,018 disputes per financial year from 2009–10 to 2013–14.

In contrast, DBDRV closed an average of 5,780 cases per financial year from 2017–18 to 2022–23.

The number of VCAT cases related to domestic building disputes remained steady between 2010–11 and 2022–23.

DBDRV is cheaper per case than VCAT

| Across all domestic building dispute cases between 2017–18 and 2022–23 … | Spent an average of … |

|---|---|

| DBDRV | $1,813 per case. |

| VCAT | $3,404 per case. |

VCAT spending more on average than DBDRV is to be expected because VCAT is a more formal process. Nonetheless, this shows that DBDRV is a more cost-effective way to resolve some disputes.

In total, 12 per cent of all DBDRV cases have moved on to VCAT. Based on our estimates, the total costs associated with both DBDRV’s 2021–22 caseload and cases that moved to VCAT was $12.4 million.

However, if DBDRV did not exist and all its cases went to VCAT, the total net cost to the government could potentially be $18.9 million, which is $6.5 million higher.

These estimates account for revenue from the fees applicants pay VCAT.

1. Context

In April 2017, the Victorian Government established DBDRV to resolve disputes between building owners and their builders before they reach a court or tribunal. There were 92,158 domestic building permits in 2022. A 2016 survey found that one in 4 builds involve a dispute between the owner and builder.

Why the government established DBDRV

DBDRV was established in 2017

DBDRV provides a conciliation service to resolve domestic building disputes that:

- pertain to residential building work that is less than 10 years old

- involve a builder, architect, subcontractor, engineer or building practitioner.

In 2015, in their second reading of legislation to establish DBDRV, the Minister for Planning said that the new service should ‘significantly reduce the costs [of dispute resolution] for both consumers and builders, as well as the stresses that come with formal legal proceedings'.

DBDRV started operating in April 2017.

How DBDRV works

DBDRV's process

Once DBDRV receives an application, it assesses whether the case is in its jurisdiction and suitable for conciliation.

There are various reasons an officer may deem a case to be unsuitable. These include if:

- the referring party has not provided all necessary information, nor taken reasonable steps to resolve a dispute themselves

- the assessor believes there is no reasonable likelihood that conciliation will be successful for a reason other than that no other party is willing to engage in conciliation.

If DBDRV accepts a case, it then allocates it to an officer who will contact both parties to find out more about the matters in dispute.

The officer may ask a DBDRV building assessor to examine the disputed work to assess if it is defective or incomplete, and whether this is the builder's fault.

A trained conciliator then attempts to mediate a resolution with both parties either in person, by teleconference or by video link. This will either result in:

- a formal record of agreement containing:

- the actions the parties agreed to

- when they will do these actions

- a certificate of conciliation noting the parties could not resolve their dispute, which allows them to apply to VCAT

- a Dispute Resolution Order, issued by the Chief Dispute Resolution Officer, which binds one or both parties to perform actions to resolve the dispute.

Appendix D shows consumers' journeys through the dispute resolution process.

DBDRV's funding

The Domestic Builders Fund covers DBDRV's expenses

The Domestic Builders Fund covers:

- DBDRV's expenses

- VCAT's hearing and administrative costs for domestic building cases

- legal support for some applicants to VCAT who are in financial stress.

The Domestic Builders Fund comprises:

- part of the levy the Victorian Building Authority collects for building permits and builders’ registration fees

- VCAT filing fees for domestic building disputes.

In 2022–23, the Domestic Builders Fund had revenue of $23.3 million. Consumer Affairs Victoria administers the fund.

Building Reform: Paper Two – Expert Panel on Building Reform

Expert panel recommended reforms to laws on dispute resolution

In December 2019, the Victorian Government appointed an expert panel to review how it regulates the building sector. In November 2023, the expert panel released the second stage of its review, including proposed recommendations on reforms to building dispute resolution.

The report recommended reforms to the Domestic Building Contracts Act 1995 (the Act) to:

- allow relevant agencies to streamline the way they share information

- remove potential process duplication between DBDRV and VCAT.

It also recommended that:

- DBDRV use more building assessments and Dispute Resolution Orders

- the government develop a model to triage building dispute applications.

The government is yet to formally respond to the report.

2. Consumer experience with DBDRV

DBDRV says that it aims to offer a free, fair and fast service. DBDRV's service is free for consumers and procedurally fair. However, DBDRV is not meeting its benchmark for the time it takes to allocate a case to an officer.

DBDRV aims to offer a 'free, fair and fast' service

DBDRV's stated intention

In its public guidance, DBDRV says that it aims to ‘make it easier for builders and building owners to access a tailored dispute resolution service, which is free, fair and fast'.

Similarly, DBDRV's objective under the Act is to resolve disputes 'as efficiently and as cheaply as possible having regard to the needs of fairness'.

DBDRV does not charge consumers for its services

DBDRV has not charged for its service

DBDRV's services are free to consumers, including its building assessments. DBDRV's website notes that it may charge consumers a fee if they request an assessment, but DBDRV has never done so.

In contrast, in 2022–23, consumers who applied to VCAT for a matter related to the Act spent an average of $607 in fees. Applicants to VCAT may also incur legal expenses preparing their case.

Up to October 2023, 7,484 consumers had their dispute fully resolved by DBDRV. Solving their disputes without going to VCAT potentially saved these consumers around $4.5 million.

DBDRV offers a procedurally fair service

DBDRV has promoted procedural fairness

All DBDRV officers are accredited mediators. The Chief Dispute Resolution Officer requires them to complete National Mediator Accreditation System training and maintain their accreditation.

Accredited mediators must comply with the National Mediator Accreditation System’s Practice Standards.

These standards align with the Australian Treasury's 2015 Key Practices for Industry-Based Customer Dispute Resolution, which suggest best practice benchmarks for resolving disputes fairly.

DBDRV's practices align with procedural fairness, except for potentially inconsistent use of assessments

DBDRV maintains a database of guidelines for its officers that covers all parts of the conciliation process. These guidelines emphasise that both parties have opportunities to respond to any information the other party provides.

DBDRV also has templates for key communications with parties, so its officers give consumers consistent information.

In 2021, DBDRV developed the Quality Assurance Review Resource to formalise internal checks of whether officers follow established guidelines. Practices in this resource align with the key practices for fairness contained in the Australian Treasury guidelines.

As part of the dispute resolution process, DBDRV sometimes arranges for a qualified building assessor to assess building work to determine whether it is defective and the builder’s fault.

However, DBDRV does not have clear guidelines for when it should use a building assessor. Its guidelines say that officers should consider whether they feel an assessment is likely to help resolve a dispute.

Clearer guidance for this may help officers know when to request a building assessment and make the process more consistent.

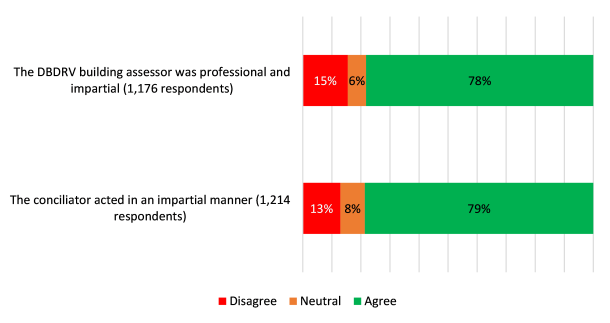

Customer survey data shows satisfaction with DBDRV's impartiality

Since 2021, DBDRV has sent a consumer experience survey to each consumer when their case closed. As of February 2024, it had issued almost 36,000 surveys, with 2,400 (6.7 per cent) customers responding.

Over 70 per cent of respondents agreed that DBDRV staff were impartial in attempting to resolve their case, as Figure 1 shows.

However, we note that this is an optional survey, and there may be bias in who chooses to respond.

Figure 1: Consumer perspectives on DBDRV's service

Note: The questions on the survey offer a response on a 7-point scale, with 1 as strongly disagree, and 7 as strongly agree. To make this clearer, we have grouped responses of 1, 2 and 3 as ‘disagree’, 4 as ‘neutral’ and 5, 6 and 7 as ‘agree’. The response rate allows us to be 95 per cent confident of the results within a margin of 1.97 percentage points. This means that, for example, if 60 per cent of respondents agree to a question, then we can be 95 per cent confident the true result for the population is between 59 per cent and 61 per cent.

Percentages have been rounded.

Source: VAGO analysis of DBDRV Customer Voice survey data from 2021 to 2023.

The outcome of a case may influence a consumer’s sentiment. The below table shows lower agreement for cases DBDRV did not resolve.

| For cases DBDRV resolved … | For cases DBDRV did not resolve … | Believed the … |

|---|---|---|

| 84 per cent of consumers | 73 per cent of consumers | conciliator was impartial. |

| 87 per cent of consumers | 73 per cent of consumers | building assessor was impartial. |

DBDRV does not send its survey to consumers before their case closes. Therefore, DBDRV cannot be sure about consumer opinion on the impartiality of officers and building assessors before a case’s outcome potentially impacts their assessment.

Based on these survey results, both builders and owners are satisfied DBDRV is fair. There is also no material difference in the outcomes for cases initiated by builders or by owners.

DBDRV is not meeting its benchmark on the timely allocation of cases to officers

DBDRV has benchmarks for its timeliness

In 2023–24, DBDRV had an internal benchmark of 44 days to assign a case to an officer after lodgement and 65 days for a case to close after officer assignment.

DBDRV says it arrived at this benchmark by averaging timeliness across the previous 3 financial years.

In 2023–24, DBDRV also developed an aspirational stretch target of 30 days to allocate a case to an officer, designed to drive continuous improvement.

Last year DBDRV took 65 days to allocate cases and 54 days to close them

As Figure 2 shows, in 2022–23 DBDRV took an average of 65 days to allocate an officer after lodgement. This does not meet its benchmark of 44 days.

After allocation, cases took an average of 54 days to close in 2022–23. This is better than DBDRV’s benchmark of 65 days.

However, this includes cases that:

- the applicants resolved before conciliation, or withdrew

- DBDRV found unsuitable for conciliation.

Cases that reached conciliation took an average of 91 days after allocation to close. This does not meet DBDRV's benchmark.

Figure 2: Average timeliness of cases from lodgement to closure

Source: VAGO analysis of DBDRV data.

In January 2024, DBDRV had a backlog of over 1,000 cases

In January 2024, DBDRV listed a backlog of 1,036 active cases waiting to be allocated to officers. As of 22 April 2024, this backlog had reduced to 716 cases.

In December 2023, the Department of Government Services approved a proposal from DBDRV to increase its number of officers by 13 per cent over the next 2 years, funded through the Domestic Builders Fund.

In February 2024, the Department of Government Services approved further measures to recruit and retain officers.

DBDRV claims that these measures will allow it to clear its backlog by mid-2024.

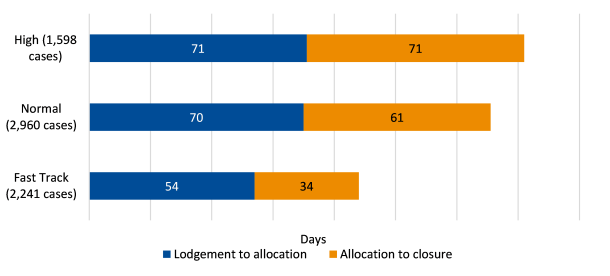

High-priority cases are not allocated faster than others

In its first year, DBDRV set up a Fast Track team to triage applications within 48 hours of consumers lodging them.

This team gives each case a priority level based on the urgency of the issue. It can close cases that are not suitable for conciliation or are out of DBDRV’s jurisdiction.

DBDRV will assign a case as high priority if it involves:

- an application by a builder, or a vulnerable consumer

- water entering the building

- lack of essential facilities, such as a kitchen or bathroom

- delayed building work leading to a financial impact

- a case within 12 months of its 10-year statute of limitations.

However, on average, DBDRV still does not allocate high priority cases to an officer within its 44 day benchmark. High priority cases take a similar amount of time as normal priority cases, as Figure 3 shows.

DBDRV sometimes speeds up cases during triage that could have an expedited resolution, to clear its backlog. It gives these cases to the Fast Track team. But on average these cases still do not meet DBDRV’s benchmark.

Figure 3: Average timeliness by case priority level

Source: VAGO analysis of DBDRV data.

DBDRV conciliations happen more quickly than VCAT hearings

VCAT gives DBDRV data that allows it to link cases that have passed through both agencies. As Figure 4 shows, cases that reach conciliation at DBDRV but then require VCAT to resolve took a median of:

- 207 days at DBDRV

- 236 days at VCAT.

This means that for the same cases, DBDRV was 12 per cent faster than VCAT using its full processes.

Cases that reach conciliation at DBDRV but do not progress to VCAT close faster. They have a median case duration of 164 days.

Figure 4: Median days at DBDRV and VCAT for cases that reached conciliation at DBDRV, 2017 to 2022

Note: We have used a median calculation in Figure 4 as we feel it is the most accurate way to represent data that has significant variation. In Figures 2 and 3 we used a mean calculation to show whether DBDRV meets its benchmark, which is also a mean.

Source: VAGO analysis of VCAT and DBDRV data.

Cases that move to VCAT are more complex

DBDRV officers assign each case a complexity rating at its closure, based on a point rating for several factors.

For example, a case with fewer than 5 items in dispute, a history of under 12 months and with civil communication between parties would receive one point for each factor.

But a case with more than 20 items in dispute, a history of over 3 years and hostile communication would receive 3 points for each factor.

According to these ratings DBDRV officers assign, cases that move to VCAT are 11 per cent more complex than those that do not.

DBDRV gives clear guidance to consumers but there are gaps in the information available for new applicants

DBDRV's public guidance is clear, but does not give all information

The homepage of DBDRV's website clearly links to key information about DBDRV’s service. Its online application form is easy to use and meets the Victorian Government's accessibility guidelines.

However, DBDRV's public guidance does not give an indicative timeline for when an officer will contact an applicant after they lodge their application.

DBDRV’s online application form only notes that there may be a delay before someone contacts the applicant.

DBDRV does not provide phone access to its office

DBDRV does not have a direct phone number for consumers. Instead, the phone number listed on its website is for Consumer Affairs Victoria's information line.

The information line advises consumers on where to go if they have a dispute and whose jurisdiction the matter is likely to fall under.

DBDRV told us that using the line avoids duplication in the dispute resolution system, which may confuse consumers.

Once DBDRV allocates an applicant to an officer, they have direct phone contact with that officer. But there is no direct phone contact before DBDRV allocates the case.

The information line staff also have no link with DBDRV's database. This means its staff cannot give specific information about an application to an unallocated consumer, as they are not DBDRV staff. This is despite DBDRV’s website listing the information line as the phone line for DBDRV.

This means that a consumer who has lodged an application cannot easily access information about its status, including when an officer is likely to contact them.

Consumers also cannot access this information from the DBDRV website. Instead, they need to email DBDRV’s general information address. In some cases, a caller to the information line may have their call escalated to a DBDRV manager if an information line manager considers it necessary.

In September 2023, DBDRV gave information line staff direct access to a dashboard that allows them to:

- search by case number

- see a case's priority level and how many days since it was lodged

- see the number of unassigned cases.

However, information line staff cannot see how this information affects when a DBDRV officer will contact the applicant.

3. DBDRV's impact on domestic building disputes

DBDRV has resolved 7,484 domestic building disputes from April 2017 to October 2023. It resolved them more cost-effectively than if they had gone to VCAT.

Until recently, DBDRV could not demonstrate from its reporting that it is meeting all its intended outcomes.

Demand for building dispute resolution has risen since DBDRV began

Rising dispute resolution applications

Before the government established DBDRV in 2017, BACV offered voluntary dispute resolution.

| Between … | Each financial year … | Closed an average of ... |

|---|---|---|

| 2009–10 and 2013–14 | BACV | 2,018 cases. |

| 2017–18 and 2022–23 | DBDRV | 5,780 cases. |

This suggests DBDRV may have stimulated previously unmet demand for a building dispute resolution service that parties otherwise may not have pursued.

The number of VCAT building dispute cases has not significantly dropped since DBDRV began, as Figure 5 shows. But domestic and residential building permits have increased, so the proportion of permits ending up at VCAT has fallen.

| On average … | There was one VCAT case for every ... |

|---|---|

| between 2012 and 2016 | 67 permits (assuming a 6-month lag between a permit being issued and a case). |

| since DBDRV began | 78 permits. |

Figure 5: Building dispute resolution cases

Note: We do not have data for BACV complaints across 2014–15, 2015–16 and 2016–17. DBDRV was established in 2016–17.

Source: VCAT annual reports, DBDRV data and VAGO data for BACV.

Outcomes for consumers who go to DBDRV

52 per cent of consumers who reach conciliation fully resolve their dispute

From its establishment in 2017 until 2022–23, DBDRV closed 34,828 cases, an average of 5,780 for each full year of its operation.

| Of all cases until November 2022 ... | Of these ... |

|---|---|

| 40 per cent reached conciliation | 52 per cent were fully resolved. |

| 7 per cent were partially resolved. | |

| 41 per cent were not resolved. | |

| 60 per cent did not reach conciliation | 55 per cent were not suitable for conciliation. |

| 11 per cent were out of jurisdiction. | |

| 33 per cent were resolved before conciliation or were withdrawn by the lodging party. |

Percentages in this table are rounded.

Appendix D shows a flowchart of the steps a case takes in DBDRV’s process, including when it may progress to VCAT.

12 per cent of cases continue to VCAT

Twenty per cent of people who are eligible to take their case to VCAT do so.

Of all completed DBDRV cases (including fully resolved or withdrawn cases) 12 per cent progress to VCAT.

As a free and informal service, DBDRV may have stimulated demand for a building dispute resolution service for consumers to seek to externally resolve their dispute.

However, some consumers whose DBDRV cases did not progress to VCAT may have applied to VCAT directly if DBDRV was not available.

It is more cost-effective for DBDRV to resolve cases than VCAT

DBDRV spends less per case than VCAT

| Between 2017–18 and 2022–23 ... | Spent an average of ... |

|---|---|

| DBDRV | $1,813 per case. |

| VCAT | $3,404 per case related to domestic building disputes. |

VCAT spending more on average than DBDRV is to be expected, because VCAT is a more formal process. Nonetheless, this shows that DBDRV is a more cost-effective service to resolve some disputes that also cost less for consumers.

Since DBDRV began, VCAT's average cost per case since has increased by 27 per cent compared to the 3 preceding years (2014–15 to 2016–17).

VCAT told us this may be because it now receives more complex cases that DBDRV could not resolve.

DBDRV may have made building dispute resolution more cost-effective

We cannot be sure if all DBDRV applicants would have applied to VCAT if DBDRV did not exist.

However, based on our cost estimates, DBDRV and VCAT's total costs associated with DBDRV’s 2021–22 caseload of 5,141 cases was $12.4 million.

If all these cases went to VCAT, the total net cost to the government could potentially be $18.9 million, which is $6.5 million more.

This calculation subtracts hearing fees received by VCAT, which VCAT pays into the Domestic Builders Fund to help fund the building dispute resolution system.

DBDRV collects and reports timely data on key measures, and has recently included benchmarks in its reporting

DBDRV has performance measures with benchmarks

DBDRV internally tracks 12 performance measures. These cover the most relevant parts of its processes.

DBDRV lists baseline performances for these measures. It calculates these as averages of the results over the last 3 years.

In 2023–24, DBDRV developed aspirational stretch targets for these measures to set an expectation for future performance.

There is one public performance measure for DBDRV in Budget Paper No. 3: Service Delivery. However, it is a simple output measure on services provided and does not provide insight into service quality.

DBDRV reports on key measure, but without benchmarks until recently

DBDRV reports on these key measures, but until recently these reports did not all contain benchmarks.

DBDRV has dashboards it updates daily to internally report these measures. It filters this data into:

- monthly reports for its senior leadership team

- a weekly general report for all officers.

These reports contain key information on the caseload backlog, timeliness and recent case outcomes.

Until 2024, these reports did not track DBDRV’s performance against its organisational benchmarks or stretch targets. So while DBDRV might be achieving its objectives, it could not use this reporting to fully demonstrate this to itself or the public.

In early 2024, DBDRV drafted new performance reporting dashboards that list these targets alongside monthly performance metrics for key information. It has made these reports available to all staff.

As of March 2024, it has also added performance targets to its senior leadership team reports.

Appendix A: Submissions and comments

Download a PDF copy of Appendix A: Submissions and comments.

Appendix B: Abbreviations, acronyms and glossary

Download a PDF copy of Appendix B: Abbreviations, acronyms and glossary.

Appendix C: Audit scope and method

Download a PDF copy of Appendix C: Audit scope and method.

Appendix D: Building dispute flowchart

Download a PDF copy of Appendix D: Building dispute flowchart.