Effectiveness of Catchment Management Authorities

Overview

The Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI) and catchment management authorities (CMA) face significant and escalating challenges if they are to meet the core objectives of the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 (the Act), which are to maintain and enhance long-term land productivity while also conserving the environment. While existing catchment management approaches are delivering some gains, they are inadequate to meet these challenges.

Statewide catchment conditions are poorly understood because of inconsistent assessment methods and a number of deficiencies in the adequacy and quality of data collected.

The limited information currently available suggests that the condition of catchments across the state is continuing to deteriorate.

The Act prescribes an integrated, long-term approach to catchment management. However, the existing statewide approach is fragmented and short-term in focus, with no expectations regarding the quality of land and water resources needed to meet the Act's objectives.

Despite these weaknesses, CMAs have developed six-year regional catchment strategies that promote long-term catchment management approaches at a regional level. However, short-term resourcing and a lack of accountability among partner agencies constrain the CMAs' ability to plan for and deliver long-term outcomes.

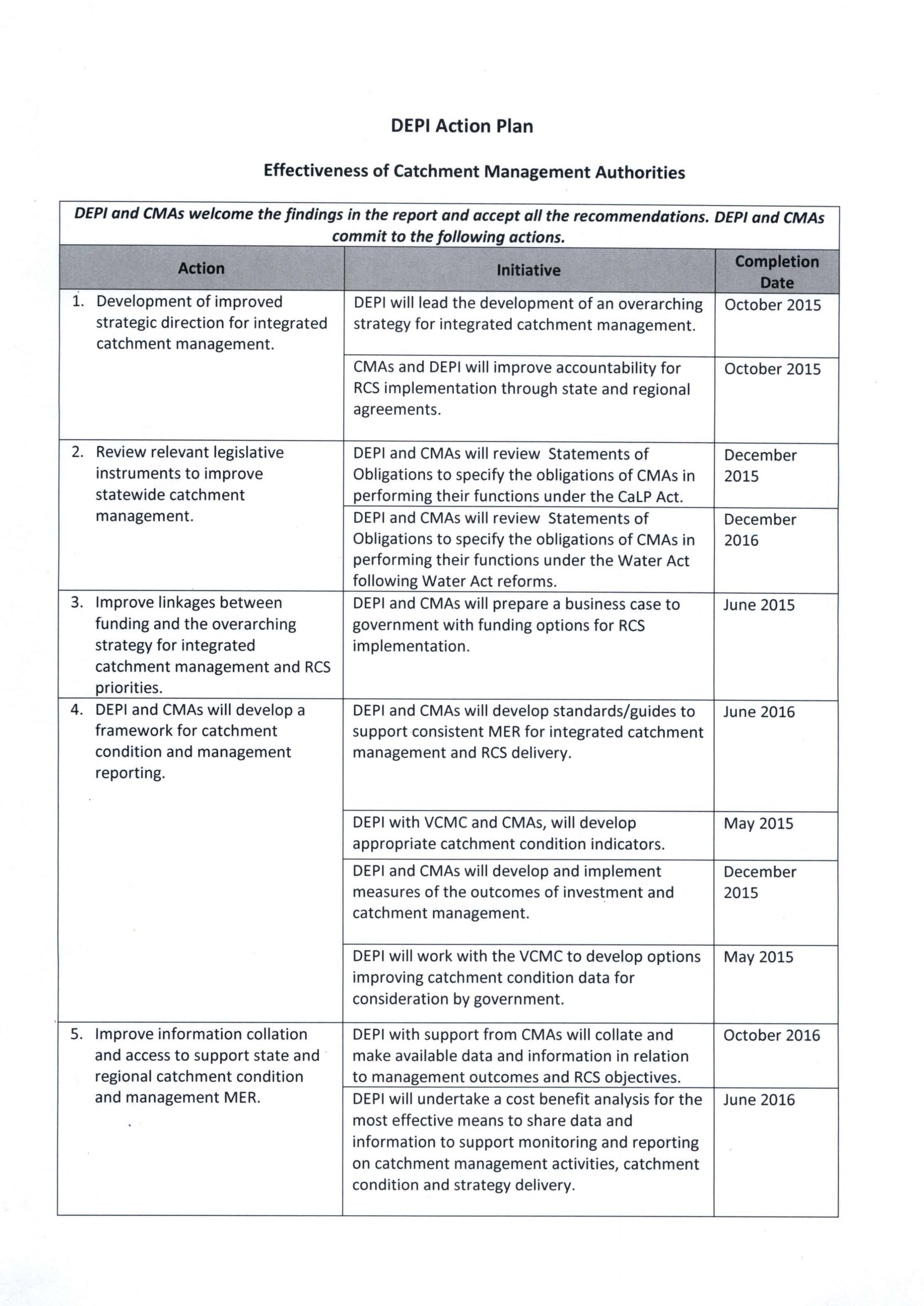

DEPI and CMAs are now working to develop a more coherent statewide approach, with improved monitoring of catchment condition, clearer roles and responsibilities, and a longer-term focus.

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Dallas Mischkulnig—Engagement Leader Christopher Badelow—Team Leader Susan Stevens—Team member Renée Cassidy—Engagement Quality Control Reviewer |

Victoria has a unique and diverse natural landscape that provides various environmental, agricultural, health and recreational benefits to its population. However, maintaining these benefits for future generations is becoming increasingly difficult, due to mounting pressures from climate variability, changes in land use and agricultural productivity demands.

Victoria's 10 catchment management authorities (CMA) have a central role in maintaining and enhancing long-term land productivity while also conserving the environment. A key function of each CMA is to prepare and coordinate the delivery of a regional catchment strategy that outlines a long-term vision for the regional landscape. CMAs also have key functions in relation to the management of regional waterways, floodplains, drainage and environmental water.

In this audit I assessed the effectiveness of four CMAs and the Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI) in supporting and monitoring CMA performance.

My audit found some significant weaknesses in catchment management at the whole‑of-state level. This included a short-term, fragmented approach highlighted by the continued absence of an overarching strategy to drive the integrated catchment management approach prescribed by the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994.

I also found a number of limitations in the data and information used to assess the condition of catchment resources across the state—although the limited information that is available indicates that conditions are deteriorating. Therefore, some 20 years after it came into effect, it remains unclear whether the Act's core catchment management objectives are being achieved.

At the regional level, the four audited CMAs have taken long-term approaches to catchment management planning through the development of their 2013–2019 regional catchment strategies. These strategies were underpinned by extensive consultation with regional communities and stakeholders, reflecting the important role that they play in delivering on-ground actions. While this is positive, deficiencies at the whole-of-state level limit the impact of CMAs' long-term, collaborative approaches.

My recommendations reinforce the need for an overarching strategy for integrated catchment management and clearer roles, responsibilities and accountabilities. I also recommend that improved arrangements for monitoring and reporting on catchment condition, strategy delivery and investment outcomes be established. I am encouraged that DEPI and CMAs have accepted these recommendations and already commenced work to implement them.

The broad nature of catchment management means that this audit will have relevance to a number of future topics that deal with natural resource management and agricultural production. These include the Implementation of the Victorian Coastal Strategy, Enhancing Food and Fibre Productivity, and Biosecurity performance audits.

I would like to thank the staff of DEPI and the four CMAs for their assistance and cooperation throughout this audit.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

September 2014

Audit Summary

The health of Victoria's catchments—comprising all natural land, water and biodiversity resources—is vital to building healthy and resilient ecosystems, supporting primary production and providing for recreational activities that support tourism. Yet protecting these resources and maintaining their productivity is an increasing challenge. Catchment assets face growing pressures from urban development, climate variability and high demand for agricultural production.

Climate variability represents a particular risk to the future health and productivity of the state's natural resources. Specifically, surface run-off into most Victorian waterways is forecast to decrease by up to 45 per cent by 2030, while the extent and frequency of droughts may more than double by 2050. Such scenarios would have significant impacts on agricultural production, farming practices and food supply chains, and would increase competition between consumptive and environmental water uses.

Established under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994, Victoria's 10 catchment management authorities (CMA) play a critical role in managing our natural resources. Each CMA is required to develop a six-year regional catchment strategy in partnership with their communities and regional partners. CMAs deliver these strategies by implementing and coordinating land and water management programs in consultation with the community and regional stakeholders. The Water Act 1989 gives nine out of 10 CMAs management powers over regional waterways, floodplains, drainage and environmental water.

The Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI) supports the CMAs in developing, delivering and evaluating these strategies. It also sets statewide strategic directions for catchment management and coordinates state funding of CMAs, which has totalled $486.8 million since 2009–10.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of CMAs in performing their legislative functions and how DEPI supports and monitors CMAs in fulfilling their roles and responsibilities. The audit examined a sample of four CMAs—the East Gippsland, Goulburn Broken, North Central and Wimmera CMAs.

Conclusions

DEPI and CMAs face significant and escalating challenges if they are to meet the core objectives of the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994—to maintain and enhance long-term land productivity while also conserving the environment. However, this audit and a range of past reviews have confirmed that the existing approaches to catchment management, while delivering some gains, are inadequate to meet these challenges.

Statewide catchment conditions and changes over time are poorly understood because of the use of inconsistent assessment methods and a number of deficiencies in adequacy and quality of data collected. While catchment condition can be influenced by both management activities and a range of natural events beyond the control of land managers, data sets should reliably demonstrate whether the state's natural assets are being effectively managed. Currently this is not possible.

The limited information currently available suggests that the condition of catchments across the state is continuing to deteriorate.

The Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 prescribes an integrated, long-term approach to catchment management in Victoria. However, the existing statewide approach is fragmented and short term in focus, with no expectations regarding the quality of land and water resources needed to meet the Act's objectives.

Despite these weaknesses, CMAs have developed six-year regional catchment strategies that promote long-term catchment management approaches at a regional level. However, short-term resourcing arrangements and a lack of accountability among partner agencies constrain the CMAs' ability to plan for and deliver long-term outcomes in their respective regions.

DEPI and CMAs have acknowledged these shortcomings and are now working to develop a more coherent statewide approach, with improved monitoring of catchment condition, clearer roles and responsibilities, and a longer-term focus. This is a positive development, however, much of the work that needs to be done to establish an adequate approach is yet to happen. Given the nature and likely future course of the risks Victoria is facing, it is critical that DEPI takes a leading role in this area.

Findings

Statewide planning

The roles and responsibilities of CMAs and other bodies that contribute to integrated catchment management in Victoria have historically been unclear, and this is reflected across a complex range of documentation. Recent work to clarify the division of roles between CMAs, DEPI and Parks Victoria via regional operating agreements has been beneficial. However, these agreements need to be expanded to include other relevant bodies that contribute to integrated catchment management.

There is no long-term overarching strategy to support an integrated approach to catchment management in Victoria. With no statewide goals, priorities and measures for integrated catchment management, DEPI cannot tell whether the state's natural resources are being effectively managed.

DEPI and CMAs are now working to address this gap by documenting a statewide approach to integrated catchment management. There is an expectation that this approach will:

- establish a long-term vision, goals and performance measures for integrated catchment management

- clarify how catchment condition and strategy delivery is to be monitored, evaluated and reported

- prioritise catchment assets and issues beyond regional boundaries to inform future investment decisions

- clarify the roles and responsibilities of all relevant bodies, as well as the broader approach to catchment management in Victoria.

Regional planning

CMAs have developed 2013–2019 regional catchment strategies that promote long-term natural resource management and substantially comply with legislation and associated guidelines. These strategies benefited from extensive community and stakeholder consultation during their development, as well as evaluations of past strategies.

However, DEPI's expectations for identifying priorities within these strategies were inconsistently met by CMAs. Consequently, DEPI has found it difficult to derive clear statewide catchment management priorities from the regional catchment strategies.

CMAs' capacity to plan for and deliver long-term catchment management improvements through their six-year regional catchment strategies is limited by:

- the lack of an overarching strategy for statewide catchment management

- insufficient arrangements to make regional partners accountable for relevant strategy actions

- short-term funding agreements with DEPI—the department and CMAs are now developing a proposal to government that, if successful, will provide a four-year state funding horizon to support strategy implementation.

CMAs have drafted regional waterway strategies as required under the Water Act 1989. These strategies provide detail on how the waterway objectives of their 2013–2019 regional catchment strategies will be achieved. These sub-strategies have not yet been finalised, but the development process to date has been sound and involved extensive collaboration between DEPI and CMAs. The detailed goals and targets in the draft waterway strategies sufficiently align with the higher-level objectives and measures contained in the regional catchment strategies.

Monitoring and reporting of catchment condition

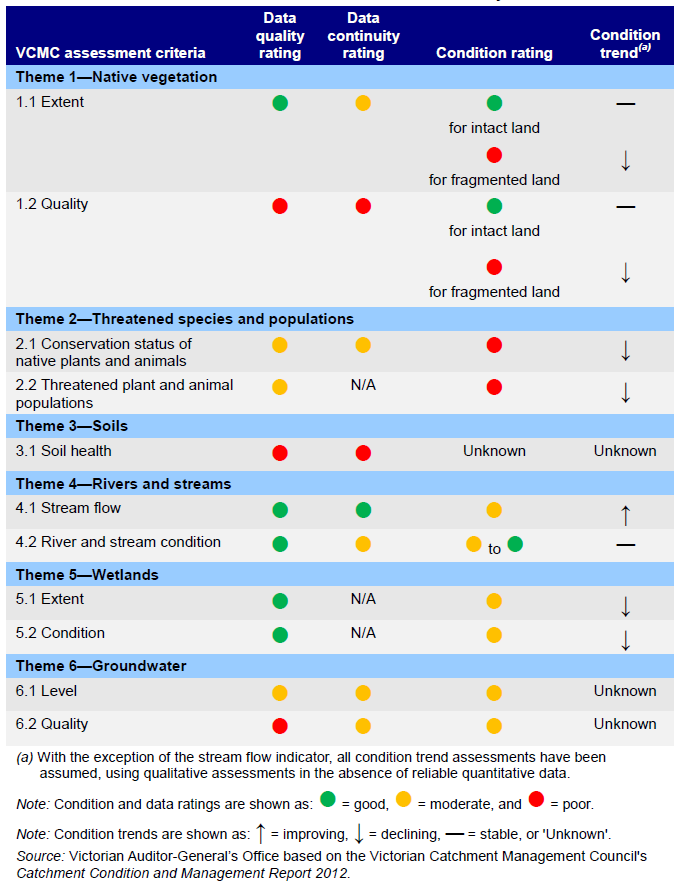

The Victorian Catchment Management Council (VCMC) produces five-yearly statewide catchment condition reports, the last of which was published in 2012. However, there are significant limitations with the data used to inform these assessments. Despite the absence of good quality data, the VCMC's qualitative assessment of condition trends suggests that catchment health is continuing to decline. Regional level catchment condition assessments have varied significantly, reflecting the lack of an agreed approach.

DEPI and CMAs are now acting to address these deficiencies through the development of:

- standard outputs for CMAs to use to report consistently on catchment management activities

- a set of consistent statewide catchment condition indicators that will inform future condition assessments at a regional and state level

- environmental economic accounts that will provide a means to report on the cost-effectiveness of proposed catchment management projects.

Monitoring and reporting on strategy delivery

Each of the regional catchment strategies developed by the four CMAs has committed to establishing frameworks for monitoring, evaluating and reporting (MER) on strategy delivery that adhere to Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994, strategy guidelines and DEPI's statewide MER framework. However, none of the four sampled CMAs are yet to establish approaches that fully achieve this. Goulburn Broken CMA is the most advanced of the four CMAs because it:

- has a pre-existing MER framework developed in 2004

- was the only CMA to have routinely reported to its board on progress in implementing its regional catchment strategy since it was published in mid‑2013.

DEPI has acknowledged the need for greater consistency across CMAs in monitoring and reporting on the delivery of regional catchment strategies. It advised that it could lead development of a consistent approach in this area that builds upon recent work to standardise reporting on natural resource management activities.

Departmental oversight of catchment management authority boards

Departmental management of CMA board appointments, training and operational performance has been satisfactory. Specifically:

- DEPI's 2013 process for appointing board members complied with Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 and relevant guidelines, and had a strong evaluation focus

- its biennial board induction and capacity training program sufficiently addressed the needs of both new and existing board members and has improved steadily over time

- the annual assessments of CMA boards provide DEPI with a useful measure of operational performance and show how past performance gaps have been dealt with.

However, statewide weaknesses in assessing catchment condition and outcomes achieved prevent DEPI from comprehensively measuring the effectiveness of boards beyond their operational duties.

Recommendations

That the Department of Environment and Primary Industries and catchment management authorities improve catchment management planning by:

-

developing an overarching strategy for integrated catchment management in Victoria that sets out a long-term vision, goals, performance measures and monitoring frameworks, investment priorities, and roles and responsibilities

-

developing mechanisms to enhance the accountability of regional partners in delivering regional catchment strategies

-

revising or replacing the statements of obligations under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 and the Water Act 1989 to reflect current approaches and planned improvements to statewide catchment management

-

clearly linking funding bids to priorities and actions in the regional catchment strategies and the overarching strategy for integrated catchment management.

That the Department of Environment and Primary Industries and catchment management authorities improve catchment management monitoring and reporting by:

-

developing and implementing a consistent approach to monitoring and publicly reporting on catchment condition, regional catchment strategy delivery and related investment outcomes. This should include:

- the finalisation of consistent catchment condition indicators for use at both state and regional levels

- addressing deficiencies in catchment condition data to support monitoring and reporting against the consistent indicators

- the development of indicators to measure the outcome of investments associated to regional catchment strategy implementation

-

developing processes to support the Victorian Catchment Management Council in collating the data it needs to develop its five-yearly statewide catchment condition reports

- assessing the costs and benefits of adopting shared information systems to support regional monitoring and reporting on catchment management activities, catchment condition and strategy delivery.

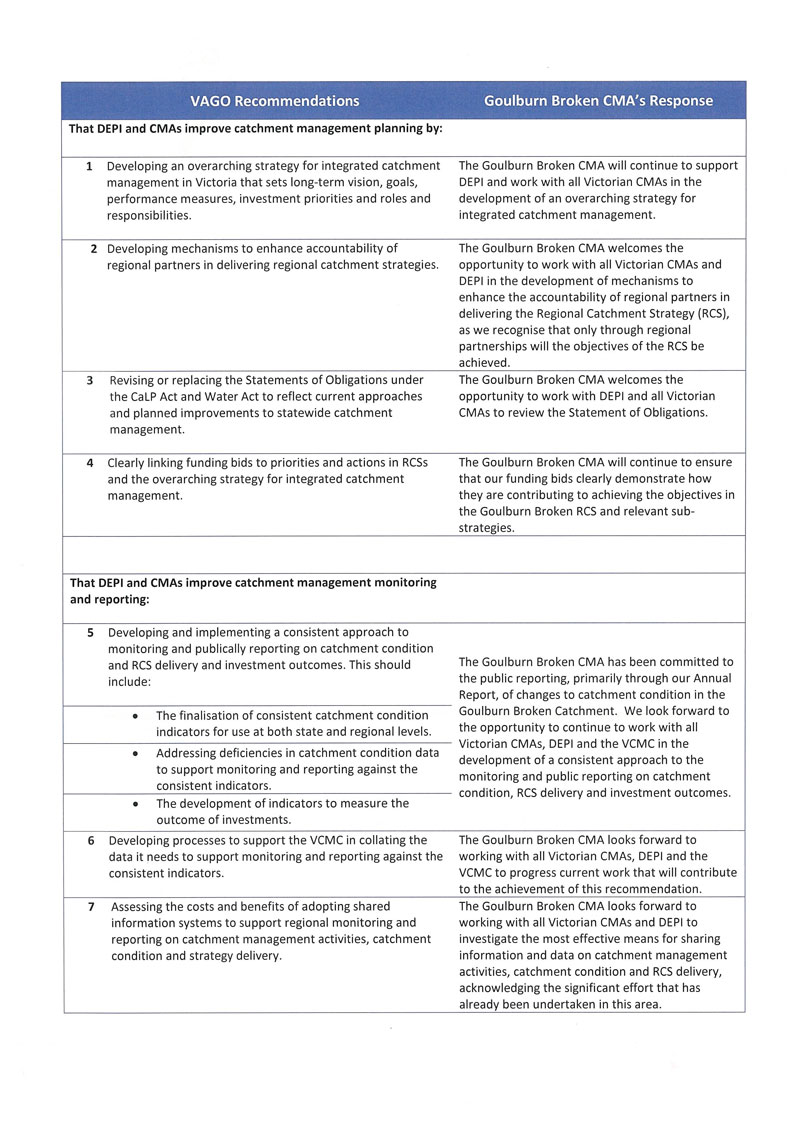

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report, or part of this report, was provided to the Department of Environment and Primary Industries, East Gippsland Catchment Management Authority, Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority, North Central Catchment Management Authority and Wimmera Catchment Management Authority with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix C.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

A catchment is an area of land where water is collected by the natural landscape. Catchments are critical to building healthy and resilient ecosystems and supporting Victoria's primary production industries. They also provide for a range of recreational activities that support tourism.

The health of these catchments depends heavily on the condition of the broader natural environment. Therefore catchment management requires the integrated management of all land, water and biodiversity resources—covering both public and private land. As private landowners hold more than two-thirds of Victoria's land, strong community input to catchment management is essential.

Protecting catchment assets and maintaining their productivity remains a significant challenge. The Victorian Catchment Management Council's (VCMC) Catchment Condition and Management Report 2012 identifies increasing pressures on Victoria's catchments from:

- climate variability, which can affect agricultural production and water availability

- changes in land uses, such as forestry and urban development

- increasing demand for agricultural productivity, leading to larger farms and fewer family farms.

According to the VCMC, climate variability is the most significant threat to the future health of the state's natural resources. Its report estimates that:

- by 2030 run-off in most Victorian waterways is expected to decrease by between 5 and 45 per cent

- by 2070 river and stream flow across the state could be halved

- by 2050 the extent and frequency of droughts may more than double.

The potential impact of these scenarios is substantial. Declining water availability would impair agricultural production, farming practices and food supply chains, and increase competition between environmental and consumptive water uses.

1.2 Catchment management in Victoria

Understanding of environmental risks and management has advanced since Victoria's catchment management authorities were established under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994. This enhanced understanding has led to increased government and community expectations for catchment management across a widened range of themes, such as:

- biodiversity and native vegetation

- soil health and salinity

- threatened plant and animal species

- waterway health

- fire recovery and flood response and recovery.

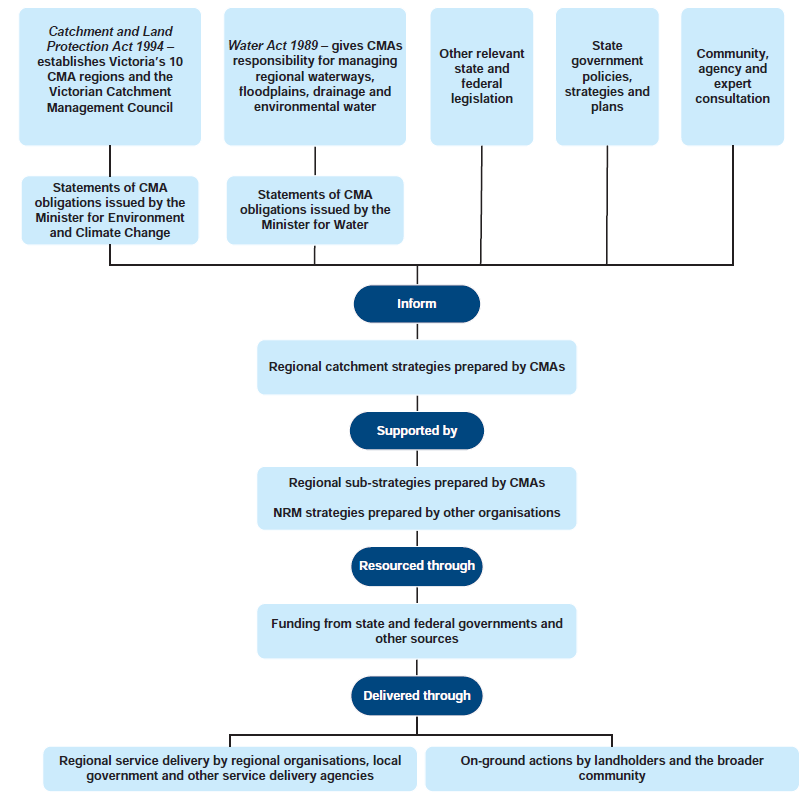

Consequently, the approach to catchment management in Victoria has evolved into a complex system of legislation, organisations, policies, strategies and funding sources.

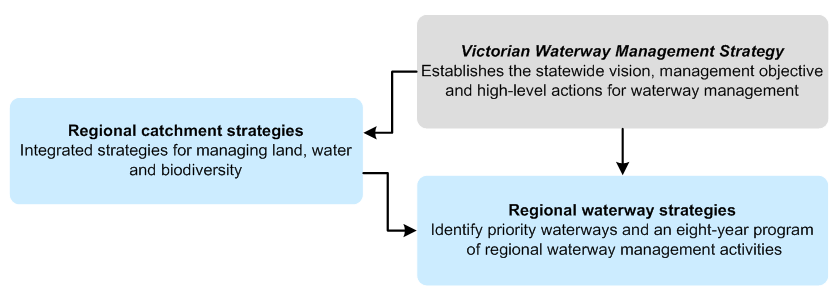

Figure 1A summarises the approach to catchment management in Victoria.

Figure 1A

Summary of catchment management in Victoria

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.2.1 Legislation

The Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 and the Water Act 1989 are the two key acts that guide catchment management in Victoria. However, there are numerous other relevant acts, as listed in Appendix A, along with various relevant government policies and strategies.

Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994

The Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 's primary objective is to establish a framework that will maintain and enhance long-term land productivity while also conserving the environment. The Act also aims to maintain and enhance the quality of land and water resources.

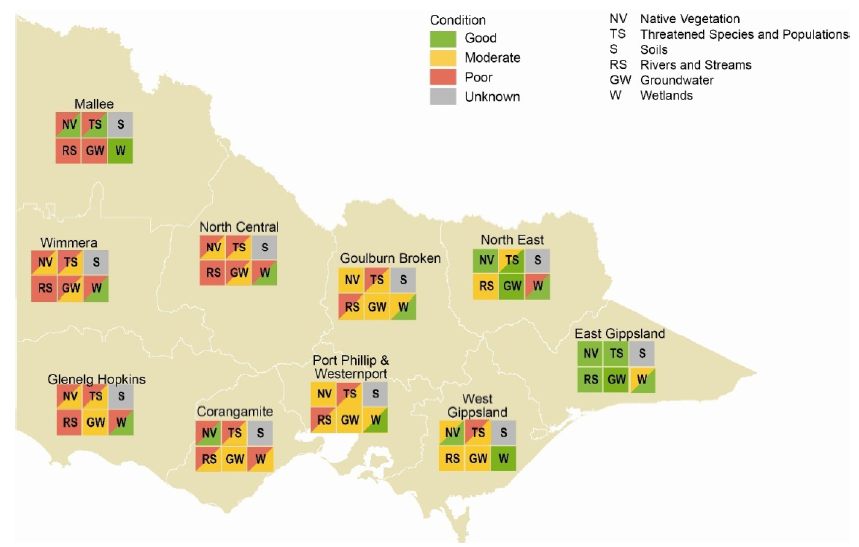

The Act divides Victoria into 10 catchment regions, each with its own catchment management authority (CMA) that reports to the Minister for Environment and Climate Change and the Minister for Water through a board. Figure 1B shows these catchment regions and qualitative assessments of their varied environmental conditions, which are poorest in the state's west.

Figure 1B

Catchment management regions and 2012 qualitative condition assessment

Source: Victorian Catchment Management Council.

CMAs are statutory authorities established under the Act to maximise community involvement in decision-making and program delivery. Under the Act, CMAs are required to develop and coordinate the implementation of a regional catchment strategy in partnership with their communities. These strategies outline a future vision for the landscape and identify regionally significant natural assets and management measures to achieve condition objectives. CMAs released their latest regional catchment strategies in 2013. The regional catchment strategies are supported by various sub-strategies for each region, covering native vegetation, river health, salinity and other areas.

Each CMA has a board that is responsible for setting strategic directions for regional land and water resources management, and monitoring and evaluating its performance. CMAs employ natural resource managers and project managers to support the board in delivering and coordinating the implementation of catchment management programs.

The Act also establishes the VCMC. Its functions include:

- advising the Minister for Environment and Climate Change on catchment management matters

- encouraging cooperation of persons involved in managing land and water resources

- publicly reporting every five years on the condition and management of land and water resources

- establishing guidelines for developing regional catchment strategies.

Water Act 1989

The Water Act 1989 gives nine out of 10 CMAs management powers over regional waterways, floodplains, drainage and environmental water. Melbourne Water has responsibility for this in the Port Phillip and Westernport CMA region.

The Water Act also requires that CMAs and Melbourne Water prepare regional waterway strategies that detail how their waterway management functions will be delivered.

Before and after works on the Cann River.

Photographs courtesy of East Gippsland CMA.

Statements of obligations under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 and the Water Act 1989

Government expectations of CMAs in performing their legislative functions are detailed in statements of obligations authorised by the ministers responsible for the Water Act 1989 and the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 in October 2006 and July 2007 respectively. These obligations cover:

- general administrative requirements, including developing corporate plans, annual reports and monitoring financial, social and environmental performance

- specific requirements that are dependent on funding including:

- developing and implementing regional plans for managing investment, landcare, biodiversity, pest management and salinity—as required under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994

- developing and implementing plans for managing river health, floodplains, drainage and responding to floods, as well as authorising works on waterways—as required under the Water Act 1989.

1.2.2 Roles and responsibilities beyond catchment management authorities

Outside of CMAs, there are a number of other bodies that contribute to catchment management in Victoria at both a statewide and a regional level. Collectively these represent a complex system, where the relationships between these bodies and CMAs are critical to the success of catchment management activities.

Department of Environment and Primary Industries

The Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI) is the lead state government agency for sustainable management of water resources, public land, forest and ecosystems. Its catchment management functions include:

- managing and coordinating state and some Commonwealth funding for catchment management programs

- setting strategic directions for catchment management through statewide policies, strategies and reviews

- supporting CMAs in developing and evaluating their regional catchment strategies

- monitoring and reporting on statewide natural resource management activities

- coordinating monitoring and reporting undertaken by CMAs

- providing service delivery in natural resource management through its regional offices.

DEPI is also one of several key service providers for projects identified in CMAs' regional catchment strategies.

Parks Victoria

Parks Victoria delivers on-ground services to manage national, state and metropolitan parks, marine national parks, Melbourne's bays and waterways, and other significant cultural assets. It acts as a service delivery provider for some CMAs.

Victorian Environmental Water Holder

The Victorian Environmental Water Holder is an independent statutory authority responsible for making decisions on the use of Victoria's environmental water entitlements. It works with CMAs and Melbourne Water to use entitlements in a way that achieves optimal environmental outcomes.

Trust for Nature

The Trust for Nature was established under the Victorian Conservation Trust Act 1972 and has powers to enter legal agreements—known as conservation covenants—with private landowners to protect native plants and wildlife on their land. CMAs work in partnership with the trust to manage conservation on private land.

Water corporations

Water corporations provide a range of regional water services that contribute to the waterway management component of catchment management:

- Melbourne Water provides bulk water and sewerage services and manages waterways and major drainage systems in the Port Phillip and Westernport region.

- Gippsland Water, Southern Rural Water and Goulburn Murray Water provide a combination of irrigation services, domestic and stock services and some bulk water supply services in their respective regions.

- Grampians Wimmera Mallee Water and Lower Murray Urban and Rural Water provide a combination of sewerage, irrigation and domestic and stock services in their respective regions.

Local government

Victoria's 79 local councils contribute to catchment management by:

- regulating land use and development through municipal planning schemes

- developing and implementing urban stormwater plans

- facilitating local industry participation in waterway management

- supporting local action groups in relation to waterway management

- undertaking strategic planning for land management, landholder incentives and rebates, grants for landholders and community groups, community capacity building and education.

Communities

Local communities make a significant contribution to catchment management in Victoria. This includes:

- individual landholders, who are required to manage their land in line with the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994

- landcare groups that work to protect, restore and manage the natural environment

- coastcare groups that work to protect and manage coastal and marine environments

- 'friends of' groups that provide practical assistance to a particular conservation reserve, or a species of native plant or animal

- conservation management networks that assist landholders and land managers in managing remnant vegetation

- traditional owners that use their knowledge of Aboriginal cultural heritage values to provide input into catchment management programs and activities.

Yarra Valley landcare group tree planting event. Photograph courtesy of DEPI.

1.2.3 Funding arrangements

CMAs are responsible for coordinating and administering a significant portion of environmental funding within their region. This includes contributions from the Commonwealth Government, Victorian Government and the private sector to deliver natural resource management programs. Between 2009–10 and 2013–14, CMAs have collectively received $486.8 million from the Victorian Government—see Figure 1C— while contributions from the Commonwealth Government over the same period totalled $233 million. There has also been a combined contribution of $100 million over this period from other sources including the private sector.

Figure 1C

State government contributions to CMAs, 2009–10 to 2013–14

|

CMA region |

09–10 ($mil) |

10–11 ($mil) |

11–12 ($mil) |

12–13 ($mil) |

13–14 ($mil) |

Total ($mil) |

Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Corangamite |

10.1 |

8.9 |

8.3 |

6.9 |

9.5 |

43.7 |

6 |

|

East Gippsland |

12.1 |

9.2 |

7.4 |

10.4 |

10.3 |

49.4 |

3 |

|

Glenelg Hopkins |

7.5 |

7.6 |

7.0 |

5.2 |

4.4 |

31.7 |

8 |

|

Goulburn Broken |

20.0 |

27.8 |

17.0 |

34.8 |

32.2 |

131.8 |

1 |

|

Mallee |

8.1 |

8.2 |

8.2 |

4.6 |

7.5 |

36.6 |

7 |

|

North Central |

12.5 |

15.3 |

10.3 |

12.9 |

11.6 |

62.6 |

2 |

|

North East |

8.0 |

13.9 |

8.6 |

8.2 |

5.3 |

44.0 |

5 |

|

Port Phillip & Westernport |

3.7 |

4.1 |

4.3 |

2.3 |

1.3 |

15.7 |

10 |

|

West Gippsland |

10.5 |

9.2 |

7.6 |

9.7 |

7.3 |

44.3 |

4 |

|

Wimmera |

5.8 |

6.1 |

5.6 |

4.6 |

4.9 |

27.0 |

9 |

|

Total |

98.3 |

110.3 |

84.3 |

99.6 |

94.3 |

486.8 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on annual reports and corporate plans of catchment management authorities.

The variation in funding between CMAs over time reflects the differing catchment assets and conditions from region to region. For example, state government contributions to Goulburn Broken CMA region have been significantly higher than the others because it generates 11 per cent of the Murray Darling Basin's resources and 26 per cent of Victoria's rural export earnings. In addition, 64 per cent of their $131.8 million is funded through an intergovernmental agreement between Victoria and the Commonwealth Government for an irrigation efficiency program.

On-farm irrigation upgrade project completed through the Farm Water program.

Photograph courtesy of Goulburn Broken CMA.

State funding of CMAs typically occurs on an annual cycle, with funds distributed through multiple streams. Figure 1D shows sources of funding in Victoria for the regional catchment strategies of CMAs.

Figure 1D

Victorian Government funding streams that relate to regional catchment strategies

|

Stream |

Purpose |

2013–14 funding |

|---|---|---|

|

CMA corporate funding |

|

$9 055 000(a) |

|

Victorian Water Programs Investment Framework |

|

$26 631 000 |

|

Victorian Landcare Program |

|

$3 643 000 |

|

Victorian Environmental Partnerships Program—Stream 1 |

|

$9 600 000 |

(a) Each CMA received one-tenth of this amount.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.3 Audit objective and scope

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of CMAs in performing their legislative functions and how DEPI supports and monitors CMAs in fulfilling their roles and responsibilities.

To address this objective the audit determined whether:

- catchment management planning, monitoring and reporting at the regional level has been effective

- the statewide catchment management framework, and DEPI's role within this framework, adequately supports regional level planning, monitoring and reporting.

The audit examined a sample of four CMA regions, covering an even geographical spread across the state and a variety of catchment asset types, as well as a mix of state funding levels. This sample included:

- East Gippsland CMA

- Goulburn Broken CMA

- North Central CMA

- Wimmera CMA.

The audit also examined DEPI's catchment management activities, across both its central and regional offices.

1.4 Audit method and cost

The audit examined statewide and regional catchment management through documentary reviews and interviews with DEPI and CMAs.

The audit was conducted under section 15 of the Audit Act 1994, and was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

Total cost of the audit was $330 000.

1.5 Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines statewide and regional catchment management planning

- Part 3 examines statewide and regional catchment management monitoring and reporting.

2 Catchment management planning

At a glance

Background

Planning for catchment management should reflect an integrated approach that recognises the links between land, water and biodiversity resources.

Conclusion

The Department of Environment and Primary Industries' (DEPI) current approach to statewide catchment management planning is ineffective. The continued absence of a long-term overarching strategy means that the state-level catchment management planning is fragmented, preventing DEPI from showing whether it is effectively targeting investment or achieving intended outcomes. Ultimately, the existing statewide planning approach is insufficient to deal with the growing pressures on the health and productivity of Victoria's natural resources.

Findings

- The clarity of catchment management roles and responsibilities has improved, but it is still insufficient.

- There is no statewide strategy for integrated catchment management. DEPI and catchment management authorities (CMA) are working to address this gap.

- CMAs' regional catchment strategies comply with legislation and associated guidelines but have used inconsistent prioritisation methods.

- Stakeholder and community input to regional catchment strategy development was extensive.

- CMAs' capacity to plan for and deliver long-term catchment management improvements is constrained by short-term funding agreements with DEPI.

Recommendation

That the Department of Environment and Primary Industries and catchment management authorities develop an overarching strategy for integrated catchment management.

2.1 Introduction

Planning for catchment management should reflect a long-term, integrated approach that recognises the links between land, water and biodiversity resources. An effective planning approach comprises:

- a coherent statewide framework that recognises the increasing threats to Victoria's natural resources and brings together the various elements of catchment management to establish long-term goals, priorities and performance measures

- regional strategies that support the statewide framework by identifying local priorities, goals and actions to drive improvements in catchment management and condition

- strong input from community members and stakeholders, in recognition of the critical role they play in undertaking on-ground catchment management actions.

This Part examines the state and regional level approaches to catchment management planning.

2.2 Conclusion

The Department of Environment and Primary Industries' (DEPI) current approach to statewide catchment management planning is ineffective. The continued absence of a long-term overarching strategy means that the state-level catchment management planning is fragmented, preventing DEPI from showing whether it is effectively targeting investment or achieving intended outcomes. Ultimately, the existing statewide planning approach is insufficient to deal with the growing pressures on the health and productivity of Victoria's natural resources.

DEPI and catchment management authorities (CMA) recognise the significance of these weaknesses and have acted recently to address them, most notably by commencing work to document a statewide approach to integrated catchment management.

Despite the absence of an integrated planning approach, the four audited CMAs have developed catchment strategies that promote long-term natural resource management in their respective regions. However, short-term state funding agreements with DEPI, and insufficient arrangements to make regional partners accountable for strategy delivery, limit CMAs' capacity to effectively plan for and deliver long-term catchment management improvements.

2.3 Clarifying roles and responsibilities

A range of government agencies perform catchment management functions across Victoria, including, but not limited to, DEPI, CMAs, Parks Victoria, water businesses and local government. It is therefore critical that the catchment management roles and responsibilities of DEPI, CMAs and CMAs' regional partners are clearly defined and understood to avoid duplication and accountability gaps.

The roles and responsibilities of DEPI, CMAs and other bodies involved in catchment management are contained in a complex range of legislation, statements, agreements and strategies. These are summarised in Figure 2A.

Figure 2A

Documents detailing catchment management roles and responsibilities

|

Documents |

Purpose |

|---|---|

|

Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 |

|

|

Water Act 1989 |

|

|

Ministerial statements of obligations under the:

|

|

|

Service-level agreements between DEPI and CMAs |

|

|

CMAs' regional catchment strategies and supporting strategies |

|

|

DEPI guidance material for strategy development |

|

|

Victorian Waterway Management Strategy |

|

|

Regional operating agreements |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The roles and responsibilities of CMAs and other bodies that contribute to catchment management in Victoria have been historically unclear. Recent work to clarify the division of roles between CMAs, DEPI and Parks Victoria has been beneficial. However, this work needs to be expanded to include other relevant bodies.

2.3.1 Clarifying catchment management authorities' roles and responsibilities

The ministerial statements of obligations under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 and the Water Act 1994 are central to clarifying how CMAs are expected to perform their legislative functions. These statements were issued between 2006 and 2007 by the ministers responsible for administering each Act.

In particular, the statements clarify the CMA functions that are mandatory and those that are subject to funding. For example, CMAs must develop an annual report but the extent to which they are required to develop and coordinate delivery of regional strategies is subject to funding agreements with DEPI.

Despite the importance of the statements of obligations in defining CMAs' roles and responsibilities, there are significant doubts about their ongoing value and relevance. Specifically, DEPI and CMAs advised that the statements are rarely used to inform catchment management planning, monitoring and reporting. The statements have also remained unchanged since they were first issued between 2006 and 2007. DEPI advised that it has made previous attempts to review the statements to determine whether they remain fit for purpose. However, none of these attempts were followed through due to changes in departmental priorities.

The 2013 Victorian Waterway Management Strategy has committed to reviewing and updating the statements of obligations under the Water Act 1989. There are currently no plans to review and update the statements of obligations under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994.

There are examples where the statements of obligations are out of date. For instance, the statements refer to state government policies, guidelines and plans that have been replaced or removed, such as:

- Governance Guidelines for DSE Portfolio Statutory Authority Board Members

- Victoria's Native Vegetation Management - A Framework for Action, 2002

- regional catchment investment plans.

Ultimately, the statements of obligations are providing little value to DEPI and CMAs and are overdue for revision, replacement or removal.

2.3.2 Clarifying of roles and responsibilities beyond catchment management authorities

In 2012, DEPI commissioned a review to define the roles and responsibilities of agencies involved in catchment management. The review found that the division of roles and responsibilities between agencies was unclear, increasing the risk of overlapping roles, duplication of effort and confusion.

In response to these issues, DEPI, CMAs and Parks Victoria have developed regional operating agreements that attempt to clarify the division of natural resource management roles in each catchment management region beyond existing legislative frameworks. These agreements do not replace the various pre-existing statements, agreements and strategies outlined on page 14.

While the regional operating agreements improve clarity around the division of catchment management roles and responsibilities between DEPI, CMAs and Parks Victoria, they exclude other relevant bodies—such as water businesses, local governments, the Victorian Environmental Water Holder and the Trust For Nature. Until the regional operating agreements are expanded to include these other bodies, there remains a risk of duplicated effort, accountability gaps and uncertainty around how catchment management roles and responsibilities are to be shared.

2.4 Statewide catchment management planning

There remains no long-term overarching strategy for integrated catchment management in Victoria, despite a range of past reports and reviews highlighting the significance of this gap. Without statewide goals, priorities and performance measures for integrated catchment management, DEPI cannot tell whether the state's natural resources are being effectively managed. This longstanding weakness is made more significant by the growing pressures on the health and productivity of Victoria's land and water resources.

DEPI and CMAs are now working to address this gap by documenting a statewide approach to integrated catchment management. It is critical that this approach establishes the long-term vision, goals, priorities and performance measures to drive long-term catchment management improvements at a whole-of-state level.

2.4.1 The lack of overarching strategy for statewide catchment management

A wide range of statewide policies and strategies across various disciplines form part of the approach to catchment management in Victoria—as shown in Appendix A. CMAs are required to align their regional catchment management strategies and supporting strategies with these statewide policies and strategies. However, CMAs' capacity to do this effectively is limited by the lack of an overarching strategy for catchment management that integrates all the associated elements.

In particular, the absence of an overarching strategy means there is no long-term statewide vision, goals or priorities for integrated catchment management. Without these DEPI cannot clearly demonstrate that state investment in integrated catchment management is being effectively targeted or achieving intended outcomes across all areas of natural resource management. Additionally, DEPI has acknowledged this gap may also limit opportunities to secure future federal investment for natural resource management.

The lack of overarching strategy for integrated catchment management has been raised in previous reports and reviews, as shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2B

Previous reports and reviews highlighting the lack of an overarching strategy for statewide integrated catchment management

|

Report/review |

Issue highlighted/recommendation |

|---|---|

|

Victorian Catchment Management Council (VCMC) Catchment Condition and Management Report 2012 |

The VCMC's 2002, 2007, and 2012 reports highlighted the lack of a statewide integrated catchment management plan with long-term targets for resource condition. |

|

VAGO performance audit Catchment Management in Victoria (2003) |

Recommended that a statewide integrated catchment management strategy be developed to link the various issue-based strategies for managing natural resources. |

|

The former Department of Sustainability and Environment's 2012 internal review of catchment management roles and responsibilities |

Notes the lack of a catchment management and land protection policy or strategy and the associated risk that issue-based policies may not provide a clear catchment management approach. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

These past reports and reviews provide a compelling rationale for developing an overarching strategy for integrated catchment management. In particular:

- The VCMC's Catchment Condition and Management Report 2012 highlights that 'there remains a lack of clarity about the quality of land and water resources needed to maintain and enhance long-term land productivity while also conserving the environment'. The report points out that these deficiencies have led to a lack of clarity about investment priorities and inconsistent monitoring methods. This audit's examination confirmed these issues.

- The 2003 VAGO performance audit Catchment Management in Victoria makes a similar point that there is no overarching mechanism for setting investment priorities and allocating resources across individual programs. This issue remains applicable more than a decade later.

2.4.2 Developing an overarching strategy for statewide catchment management

Previous attempts have been made to develop an integrated statewide strategy that sits above CMAs' regional catchment strategies. Specifically, the previous government's 2009 Securing Our Natural Future—A white paper for land and biodiversity at a time of climate change committed to developing a Victorian Natural Resource Management Plan, however, this was not implemented following the change in government in late 2010.

DEPI and CMAs have acknowledged this gap, and in mid-2014 commenced work to document a statewide approach to integrated catchment management. This formed part of the CMA chairs' proposal to move from an annual funding cycle to a multi-year funding cycle.

The documented statewide approach is intended to be a high-level overview of government policy directions and priorities for catchment management, rather than a more detailed strategy. CMAs advised that they prefer this method because it would require less modification to CMAs' existing regional catchment strategies, which were published in 2013. Irrespective of this preference, an effective statewide approach or strategy should:

- establish a long-term vision, goals and measures against which catchment management outcomes can be assessed at both a statewide and regional level—these should clearly establish the quality of natural resources needed to conserve the environment and improve land productivity while acknowledging the differences that exist across catchment regions

- clarify how catchment condition and strategy delivery is to be monitored, evaluated and reported

- prioritise catchment assets and issues beyond regional boundaries to help inform future investment decisions across all investment streams

- explain the approach to integrated catchment management in Victoria, including the links between the relevant legislation, policies, strategies and plans

- clarify the roles, responsibilities and accountabilities of all bodies that contribute to Victorian catchment management.

2.5 Regional catchment management planning

CMAs have developed 2013–2019 regional catchment strategies that promote long‑term natural resource management in their respective regions and substantially comply with legislation and associated guidelines. These strategies benefited from extensive community and stakeholder consultation during development, as well as evaluations of past strategies. However, DEPI's expectations for identifying priorities within these strategies were inconsistently met by CMAs. Consequently, DEPI has found it difficult to derive clear statewide catchment management priorities from CMAs' regional catchment strategies.

CMAs' capacity to plan for and deliver long-term catchment management improvements through their six-year regional catchment strategies is constrained by:

- the lack of a long-term overarching strategy for integrated catchment management in Victoria

- insufficient arrangements to make regional partners accountable for relevant strategy actions

- short-term funding agreements with DEPI.

DEPI and CMAs are now developing a proposal to government that, if successful, will provide a four-year state funding horizon to support strategy implementation.

2.5.1 Regional catchment strategies

Compliance with legislation and guidelines

Under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994, CMAs' regional catchment strategies must comply with the VCMC's Regional Catchment Strategy Guidelines 2011. The VCMC set these guidelines at a high level to focus on the requirements of the Act. The guidelines require that strategies:

- assess the condition and use of regional land and water resources and identify areas for priority attention

- identify objectives for the quality of regional land and water resources, along with measures for achieving these

- identify priority partners and their roles in strategy implementation

- identify arrangements for reviewing the strategy and monitoring implementation

- link with relevant federal, state and regional legislation, policies, strategies and plans

- summarise the key findings from the review of the previous regional catchment strategy.

Between 2011 and 2012 the former Department of Sustainability and Environment and the VCMC worked closely with CMAs in developing their 2013–2019 regional catchment strategies to ensure compliance with legislation and guidelines. This included the provision of detailed feedback on CMAs' draft and revised strategies.

DEPI's and the VCMC's reviews of draft regional catchment strategies, along with this audit's examination, showed overall compliance with the Act and the VCMC guidelines. Each of the four CMAs' regional catchment strategies establishes a long-term vision for the regional landscape that is underpinned by strategic objectives, actions and priorities for each asset class. For example, the East Gippsland CMA regional catchment strategy contains a 20-year vision, 20-year program objectives and a range of six-year management actions.

Meeting the Department of Environment and Primary Industries' expectations

To supplement the VCMC guidelines, DEPI developed a range of additional guidance material in consultation with CMAs to clarify its expectations regarding:

- consideration of departmental policies and programs in preparing regional catchment strategies

- applying an 'asset-based' approach to identifying high-priority catchment areas within each strategy. DEPI's guidance prescribed this approach to 'tell a clear and integrated story about what needs to be achieved, from the local to state level, to conserve the region's priority land, water and biodiversity resources'.

DEPI also provided advice to all 10 CMAs through the Regional Catchment Strategy Managers Forum, which sought to provide a collaborative environment for strategy development.

However, CMAs' adherence to DEPI's guidance material was mixed, particularly in applying an asset-based approach to priority setting. For example:

- Goulburn Broken CMA explained their utilisation of 'an assets-based approach through a resilience thinking framework' to identify priorities—a method that focused on the ability of the environment and community to cope with major events, such as flood, fire and drought.

- Wimmera CMA did not include spatial mapping in its regional catchment strategies showing asset-based regional priorities but advised that it underpinned its strategy development.

DEPI advised that although it tolerated differences in strategy development acknowledging CMAs as autonomous bodies, it encouraged opportunities to strengthen the combined value of strategies across the state through improved consistency.

CMAs believe the differences between regional catchment strategies are positive and indicative of:

- the unique catchment assets, conditions and challenges faced by each region

- the strong community input to, and ownership of, the strategy.

Nevertheless, the inconsistencies in priority setting across regional catchment strategies impede DEPI from deriving clear state-level catchment management priorities.

Linking statewide and regional planning

In the absence of an overarching strategy for integrated catchment management that integrates regional and statewide planning, DEPI provided CMAs with guidance material to help establish links between their current regional catchment strategies and relevant legislation, policies and strategies. CMAs have used this guidance to list relevant legislation and policies in their regional catchment strategies. However, it is still challenging for the CMAs to clearly demonstrate how the content of their strategies aligns with the wide-ranging legislation, policies and strategies relevant to catchment management in Victoria. A statewide catchment management strategy could help to address this issue by explaining the interrelationships between all the fragmented elements.

Capacity to deliver regional catchment strategies

Regional catchment strategies inform the strategic planning of regional partners who play a key role in performing the on-ground actions that support their implementation. It is therefore important that partners:

- commit to strategy actions during development

- can be held accountable for implementing strategy actions.

CMAs reported that getting regional partners to commit to delivery of the regional catchment strategies was challenging in the absence of any mechanisms to make them accountable for implementing strategy actions. Consequently, CMAs' strategies vary in how they identify partner roles in strategy delivery, as shown in Figure 2C.

Figure 2C

CMAs' methods for identifying partner roles in regional catchment strategy implementation

|

CMA region |

Method |

|---|---|

|

East Gippsland |

|

|

Goulburn Broken |

|

|

North Central |

|

|

Wimmera |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

CMA's ability to effectively develop and deliver well-targeted regional catchment strategies is limited by a lack of arrangements that make regional partners accountable for implementing strategy actions. This gap could potentially be addressed through improvements to regional operating agreements.

Building upon the previous regional catchment strategies

CMAs are now delivering their third generation of regional catchment strategies. Although these have evolved and improved over time in response to CMAs' reviews of expiring strategies and advances in understanding of environmental risks and management, there are further areas where improvements can be made.

The first generation of regional catchment strategies were published in 1997. These strategies focused on identifying and addressing threats to natural resources in each region—which promoted a reactive approach to catchment management. Reviews of these strategies by CMAs showed that this approach made it difficult to set effective strategy targets and foster community acceptance and participation.

The second generation of regional catchment strategies were published between 2003 and 2005. They built upon the previous strategies by moving away from a threat-based approach to focus on identifying natural assets in each region and enhancing their values. This approach enabled improved regional priority setting and provided a clearer rationale for decision-making. Key improvement areas identified in CMAs' reviews of these strategies included:

- developing a robust monitoring, evaluation and reporting (MER) framework—DEPI has since developed a MER framework for land, water and biodiversity that can be applied to regional catchment strategies

- increasing strategy ownership among delivery partners—this remains a relevant issue in the absence of sufficient arrangements to make these partners accountable for relevant strategy actions.

DEPI prescribed an asset-based approach to regional priority setting in the third and current generation of CMAs' regional catchment strategies. This approach included improvements to the way regional priorities were identified through spatial mapping for each catchment asset class. However, this approach was adopted inconsistently by CMAs.

Overall, DEPI and CMAs have shown steady improvement in the quality of regional catchment strategies over time. However, further work is needed to enhance strategy ownership among delivery partners.

Stakeholder and community consultation

Successful delivery of CMAs' regional catchment strategies requires on-the-ground actions by private landholders and regional organisations with natural resource management responsibilities. It is therefore critical that CMAs have sound approaches to community and stakeholder engagement, and use this input in developing their regional catchment strategies.

CMAs' regional catchment strategies were underpinned by extensive community and stakeholder engagement that informed the strategies' goals, priorities and actions. While this is positive, there is room for the North Central and Wimmera CMAs to improve their community and stakeholder engagement frameworks.

Stakeholder and community input to strategy development

The Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 requires that CMAs prepare and implement their regional catchment strategies in a way that promotes the cooperation of people and organisations involved in managing land and water resources in their region.

CMAs' 2013–2019 regional catchment strategies were underpinned by extensive stakeholder and community consultation during development. As shown in Figure 2D, this included numerous meetings and workshops with the community and other stakeholders and opportunities for public comment on draft versions of the strategy.

Figure 2D

CMAs' community and stakeholder engagement to inform regional catchment strategy development

|

CMA region |

Summary of engagement |

|---|---|

|

East Gippsland |

Conducted over 300 interviews with landholders and participated in workshops conducted by key stakeholders. |

|

Goulburn Broken |

Conducted 39 meetings with local government and other key partner agencies, three expert workshops, and numerous meetings with traditional owners and the general community. Also provided an interactive web portal for community input. |

|

North Central |

Conducted 10 community workshops to identify priority catchment assets and a further 10 community meetings to seek feedback on the draft strategy, as well as targeted consultation with key stakeholders. |

|

Wimmera |

Commissioned a survey of 496 landholders and conducted more than 50 meetings with stakeholders and community based organisations. Also held five community workshops and meetings with regional partners to receive comments on the draft strategy. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

This wide-ranging consultation had a direct influence on how CMAs shaped their regional catchment strategies. For example:

- East Gippsland CMA's workshops with key stakeholders informed risk assessments and objectives for each asset class

- Goulburn Broken CMA's community interviews and workshops identified key catchment management issues and threats in the region, which were then refined by stakeholder panels and used to inform strategy objectives

- North Central CMA's consultation with the community and partner agencies informed the identification of priority natural assets in the region

- Wimmera CMA's public consultation informed its assessment of the social, economic and environmental value of natural assets.

Regional frameworks for stakeholder and community engagement

Since drafting their 2013–2019 regional catchment strategies, CMAs have developed a statewide framework for stakeholder and community engagement that details their:

- shared principles for community engagement

- shared expectations, including development of a community engagement strategy

- approach to measuring the effectiveness of community engagement.

The framework provides a consistent, strategic approach for CMAs and commits them to evaluating and improving their engagement performance over time.

In line with requirements under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994, all four sampled CMAs have demonstrated a particular focus on stakeholder and community engagement. Although the new statewide engagement framework was not available during regional catchment strategy development, the extent to which CMAs' current engagement approaches follow the framework varies:

- The East Gippsland and Goulburn Broken CMAs had the most comprehensive approaches, comprising an annual engagement strategy that set engagement goals and supporting actions to achieve these, along with processes for regularly reviewing the strategy and the effectiveness of engagement activities.

- North Central CMA's 2013–15 engagement strategy broadly aligns with the framework, although it lacks clear measures to support achievement of the strategy's objectives and expected outcomes.

- Wimmera CMA has a stakeholder and community engagement policy that details its high-level approach. However, it lacks specific goals and supporting actions to drive improvement. Its last community engagement plan was completed in 2007 and does not align with the new framework.

The gaps in the North Central and Wimmera CMAs' stakeholder and community engagement frameworks limit their capacity to demonstrate the impacts of their extensive engagement activities.

Community event to launch the Communities for Nature project.

Photograph courtesy of Goulburn Broken CMA.

Funding arrangements to support strategy delivery

There is no dedicated funding stream to implement CMAs' regional catchment strategies. Instead, state funding is typically distributed annually through service-level agreements between DEPI and CMAs that outline the regional projects to be delivered for the upcoming year.

Impacts of an annual investment cycle

CMAs' ability to plan for and deliver their six-year strategies is constrained by having to negotiate annual service-level agreements with DEPI to access state funding. The lack of funding certainty that this annual cycle creates is particularly limiting in the catchment management field, where desired outcomes are normally achieved in the longer term.

In March 2014, the CMA chairs submitted a proposal to government to move to a four‑year state funding cycle to better support implementation of CMAs' regional catchment strategies. The proposal sought to:

- demonstrate the above constraints, along with the estimated administrative efficiency gains of moving from an annual to a four-year investment cycle

- highlight cost reductions and efficiency gains already achieved within CMAs, DEPI and community groups

- improve the ability to attract catchment management investment in Victoria.

Figure 2E summarises the CMA chairs' proposal.

Figure 2E

Proposal by CMAs to move from an annual to a four-year state funding cycle

|

High-level problems with the existing annual funding cycle |

|---|

|

|

High-level benefits of moving to a four-year funding cycle |

|

|

Estimated administrative efficiency gains of moving to a four-year cycle(a) |

|

(a) Estimated efficiency gains have a +/-50 per cent variability, due to uncertainty around the extent of changes that will be made by government as a result of the proposal.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

DEPI and the Ministers for Environment and Climate Change and Water have endorsed the proposal, which is expected to be considered by government in the upcoming Budget cycle.

There are some previous examples of catchment management projects receiving multi-year funding from the state government. In these cases CMAs have been able to take an integrated, long-term approach to project planning and delivery, and have been better placed to demonstrate the impacts of their investment. Such projects include the:

- Snowy Rehabilitation Project—which has been active since 2004 and has comprised seven integrated sub-projects to improve the health, resilience and ecological functioning of the Snowy River system.

- Goulburn River Large Scale River Restoration Project—which was delivered between 2008–09 and 2011–12 and comprised a range of sub-projects that made environmental improvements to the Goulburn River and its floodplain.

- Loddon Stressed River Project—which was delivered between 2003 and 2013 and provided a range of integrated river restoration and community engagement activities.

- Wimmera Catchment Large Scale River Restoration Project—which was delivered between 2008–09 and 2011–12 and included a range of activities to manage the threats to and values of the Wimmera River Catchment.

Details on these projects, including their achievements, are contained in Appendix B.

Aligning state investment with regional catchment strategies

In the absence of an overarching strategy for statewide catchment management, investment priorities are set separately across individual investment streams. These are shown in Figure 2F.

Figure 2F

Methods for setting state investment priorities for catchment management

|

Investment stream |

How investment priorities are set |

|---|---|

|

Victorian Water Programs Investment Framework (VWPIF) |

|

|

Victorian Environmental Partnerships Program (VEPP) |

|

|

Victorian Landcare Program |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

To receive funding under both the VWPIF and VEPP, DEPI requires CMAs' annual project bids to articulate links to their regional catchment strategies and sub-strategies. However, the sample of successful project submissions reviewed during this audit contained only high-level links to CMAs' regional catchment strategies. No links were established to specific strategy objectives, priorities or actions. Consequently, there is a lack of clarity around the alignment between investment priorities and regional catchment strategies.

The Victorian Landcare Program uses a devolved model where CMAs receive base allocations to distribute local grants. The four CMAs' regional catchment strategies showed sufficient alignment with the program's investment principles.

2.6 Regional sub-strategies

CMAs have developed numerous sub-strategies over time that support delivery of their regional catchment strategies and focus on specific areas of natural resource management. These sub-strategies typically outline detailed goals and actions to complement the higher-level goals and actions contained in the regional catchment strategies.

Funding to develop these sub-strategies has varied across these areas—reflecting differences in government priorities. Accordingly, CMAs do not maintain a full range of up-to-date regional sub-strategies across all catchment management themes.

Management of waterways—comprising rivers, estuaries and wetlands—represents the most significant state government priority area across all catchment management themes. In 2013 DEPI released the Victorian Waterway Management Strategy that describes CMAs' requirement to develop regional waterway strategies under the Water Act 1989. Draft regional strategies have been prepared and are awaiting ministerial approval.

While CMAs' draft regional waterway strategies support the implementation of the Victorian Waterway Management Strategy, they are also considered to be a sub‑strategy to CMAs' regional catchment strategies. The relationship between these is shown in Figure 2G.

Before and after works on the Lower Tambo River.

Photographs courtesy of East Gippsland CMA.

Figure 2G

Relationship between the Victorian Waterway Management Strategy, regional waterway strategies and regional catchment strategies

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The process for developing CMAs' regional waterway management strategies has been sound. Specifically:

- CMAs had extensive input to developing the Victorian Waterway Management Strategy, including its policies and actions, through the Victorian Waterway Managers' Forum.

- The Victorian Waterway Management Strategy, along with mandatory guidelines issued by DEPI, provided a clear foundation for CMAs to develop their regional waterway strategies. Consequently the four audited CMAs' draft regional waterway strategies contain a long-term vision, 20-year goals and detailed eight‑year work program that support the state-level policies and actions.

- There was sufficient public consultation to inform the development of the Victorian Waterway Management Strategy and the four CMAs' draft regional waterway strategies.

- DEPI and CMAs had built upon the previous 2002–2012 Victorian River Health Strategy and supporting regional river health strategies by taking a more integrated approach that focuses on managing rivers, estuaries and wetlands.

The vision, objectives and detailed actions in CMAs' regional waterway strategies adequately align with and support the higher-level waterway goals and actions contained in their regional catchment strategies.

Stock-proof fencing and revegetation on a property on the mid-Goulburn near Swanpool.

Photograph courtesy of Goulburn Broken CMA.

Recommendations

That the Department of Environment and Primary Industries and catchment management authorities improve catchment management planning by:

- developing an overarching strategy for integrated catchment management in Victoria that sets out a long-term vision, goals, performance measures and monitoring frameworks, investment priorities, and roles and responsibilities

- developing mechanisms to enhance the accountability of regional partners in delivering regional catchment strategies

- revising or replacing the statements of obligations under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 and the Water Act 1989 to reflect current approaches and planned improvements to statewide catchment management

- clearly linking funding bids to priorities and actions in the regional catchment strategies and the overarching strategy for integrated catchment management.

3 Catchment management monitoring and reporting

At a glance

Background

A fully effective catchment management approach includes robust monitoring and reporting on catchment condition, regional catchment strategy implementation and catchment management authorities' (CMA) board performance.

Conclusion

Catchment management monitoring and reporting at a statewide and regional level has historically been ineffective. Significant gaps in the quality, consistency and continuity of data used to inform statewide catchment condition assessments have hindered efforts to show reliable condition trends, effectively target investment and demonstrate outcomes achieved. Inconsistent approaches at the regional level for recording catchment condition and works delivery have contributed to these shortcomings.

Findings

- There are significant limitations with the data used to inform statewide catchment condition assessments.

- CMAs' approaches to assessing regional catchment condition have varied.

- To address these issues the Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI) and CMAs are developing consistent approaches to reporting on outputs, catchment condition and investment outcomes.

- CMAs are yet to finalise frameworks for monitoring and reporting on delivery of their regional catchment strategies.

- CMAs use varying monitoring and reporting information systems.

- DEPI's monitoring of CMA boards has been satisfactory.

Recommendation

That DEPI and CMAs develop and implement a consistent approach to monitoring and publicly reporting on catchment condition, regional catchment strategy delivery and investment outcomes.

3.1 Introduction

The increasing pressures of land use and climate variability on the health of Victoria's natural resources make it more important than ever that catchment condition is clearly understood, along with the impact of catchment management activities.

A fully effective catchment management approach includes robust monitoring and reporting arrangements to show:

- statewide and regional catchment condition and trends over time, using consistent measures and reliable data

- the delivery and achievements of regional catchment strategies, which are critical to driving improvements in catchment condition and land productivity

- the capability and performance of catchment management authorities' (CMA) boards in fulfilling their roles under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 and the Water Act 1989.

This Part examines the effectiveness of monitoring and reporting on these areas. Our assessment of CMAs' monitoring and reporting against their 2013–2019 regional catchment strategies focuses on their monitoring and reporting approach, rather than on the progress made in delivering the strategies. This reflects the limited time that has elapsed since the CMAs finalised their strategies in 2013.

3.2 Conclusion

Catchment management monitoring and reporting at a statewide and regional level has historically been ineffective. Significant gaps in the quality, consistency and continuity of data used to inform statewide catchment condition assessments have hindered efforts to show reliable condition trends, effectively target investment and demonstrate outcomes achieved. Inconsistent approaches at the regional level for recording catchment condition and works delivery have contributed to these shortcomings.

The Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI) and CMAs recognise that these weaknesses need urgent attention if the state's natural assets are to be effectively protected and maintained into the future. Recent and future planned work to develop consistent approaches to monitor and report on outputs, catchment condition and investment outcomes is a positive development, but further work is still required to realise their intended benefits.

3.3 Monitoring and reporting on catchment condition

Determinations of catchment condition are based on assessments of various elements, including:

- native vegetation

- rivers and streams

- threatened species and populations

- groundwater

- soils

- wetlands.

There have been significant limitations with the data used to inform previous statewide catchment condition assessments. Combined with inconsistent catchment condition monitoring approaches at a regional level, this impedes the ability to effectively target investment and measure the impact of catchment management programs. However, DEPI and CMAs are now acting to address these deficiencies through the development of consistent monitoring and reporting approaches.

Before and after works at Frenchmans Gully, Lakes Entrance.

Photograph courtesy of East Gippsland CMA.

3.3.1 Statewide monitoring and reporting on catchment condition